INTRODUCTION

Despite many advances in evidence-based perinatal care, perinatal health outcomes in the United States are suboptimal.1–4 While national maternal mortality rates are decreasing in many countries, they continue to rise in the U.S.1 and infant mortality rates in the U.S. are greater than in many other developed countries.2,3 There are also persistent racial-ethnic disparities in both infant and maternal outcomes.2,4 There are ongoing efforts across the country to address these urgent challenges in perinatal health and improve outcomes. State-based perinatal quality collaboratives (PQCs) have shown that the application of collaborative improvement science methods can optimize perinatal health outcomes.5 PQCs are state or multistate networks that improve measurable outcomes for maternal and infant health by advancing evidence-informed clinical practices and processes using quality improvement (QI) strategies. They address gaps by working with clinical teams, public health leaders, and other stakeholders, including patients and families, to implement statewide initiatives that spread best clinical practices, reduce variation in practice, and promote health equity.5

PQCs represent a community of change, identifying health care processes that need to be improved and using the best available methods to make changes as quickly as possible.6 The PQC model of perinatal QI has shown success in rapid scale-up of evidence-based practices by leveraging state and local stakeholders.6 They engage clinical hospital teams into a network that shares ideas, tools, and strategies for implementation of improvement projects and initiatives. There is growing evidence of how PQCs have contributed to important changes in perinatal health care and how their work has led to significant improvements in perinatal outcomes.

PQCs are now developing across the country and are making progress in improving maternal health outcomes, as will be described later. Sustaining this progress will take improved awareness of the important role of PQCs in this effort and the need for ongoing support and collaboration. This article describes PQC history, infrastructure and function, and the role of obstetric providers in PQC work, as well as providing examples of progress and successes PQCs have achieved to improve maternal care and outcomes.

THE HISTORY OF PERINATAL QUALITY COLLABORATIVES

The number of PQCs in the United States has grown considerably over the last decade, with almost every state currently having an active PQC or one in development.5,7 However, the road to building statewide capacity to improve perinatal care has been a long one. In the 1990s, the Institute of Medicine (IOM) put new emphasis on QI that led to the publication of 2 reports that fixed national attention on the critical need for QI in health care.8,9 In the 2001 report, “Crossing the Quality Chasm,” the IOM charged the health care system with frequently lacking “the environment, the processes, and the capabilities needed to ensure that services are safe, effective, patient-centered, timely, efficient, and equitable,”9 qualities called the “six aims for improvement.”9 In addition to achieving these aims, the IOM recommended improving patient safety and reducing medical error by establishing a national focus on leadership, research, tools, and protocols about safety.9,10 Over the next decade, many organizations, including private and professional organizations, along with federal and state governments responded, and were instrumental in guiding the evolution of the perinatal system of care and early QI efforts. This included work by the Institute of Healthcare Improvement (IHI) that spearheaded the use of collaborative quality improvement; the first formal improvement collaborative in neonatology conducted by the Vermont Oxford Network; and regional collaborative improvement work in neonatology.6,10 This work was followed by a focus on quality of care for mothers and newborns by multiple professional organizations that led to new quality measures and standards for improving maternity care.10,11

The increased growth of PQCs is largely caused by the work and support received from state and national programs to build capacity and infrastructure for PQCs. Since 2011, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has supported state PQCs and currently provides funding for 13 state PQCs and the National Network of Perinatal Quality Collaboratives (NNPQC). The NNPQC was launched in 2016 in coordination with the March of Dimes and is now coordinated by the National Institute for Children’s Health Quality (NICHQ). The NNPQC provides technical support for PQCs, identifying and disseminating best practices for establishing and sustaining all PQCs across the country.5 Another important source of resources and support for PQCs has been the Alliance for Innovation on Maternal Health (AIM). In 2014, AIM was funded by the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) to develop maternal safety bundles of evidence-based practices that are implemented statewide by PQCs.5,12

PERINATAL QUALITY COLLABORATIVE INFRASTRUCTURE AND FUNCTION

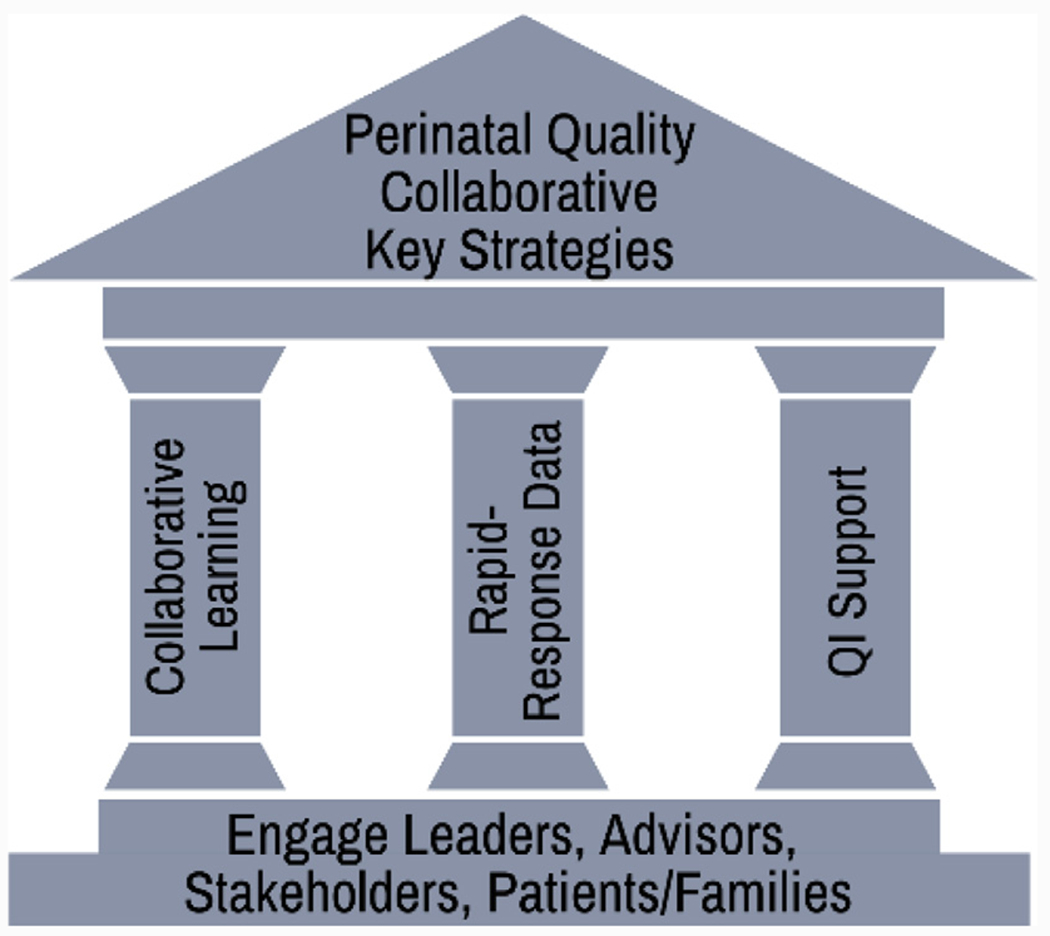

Although there are many state-based organizations that address issues of perinatal care, PQCs serve a specific role in using data and QI methods to make measurable improvements in care and outcomes. Many PQCs use the IHI Breakthrough Series model to implement QI science at the collaborative level (Fig. 1).13 Key strategies used by PQCs include (1) collaborative learning to provide opportunities for clinical teams across the state to share knowledge, strategies, and experiences while working toward unified objectives for improvement; (2) use of rapid-response data with regular data reports for clinical teams to monitor progress across time and compare progress with other teams toward meeting those objectives; and (3) provision of QI science support and assistance to clinical teams (Fig. 2).5 The ultimate goal of PQCs is to achieve sustainable improvements in population-level outcomes in maternal and infant health. Clinical teams are the heart of a PQC, and they drive the processes and change that happens at the local level.

Fig. 1.

The model for improvement. (From Langley GL MR, Nolan TW, Norman CL, Provost LP. The improvement guide: a practical approach to enhancing organizational performance 2nd ed. San Fransico: Jossey-Bass Publishers; 2009; with permission.)

Fig. 2.

Key strategies used by PQCs. (Adapted from Lee King PA, Young D, Borders AEB. A framework to harness the power of quality collaboratives to improve perinatal outcomes. Clinical Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2019;62(3):606; with permission.)

There are various organizational structures and homes for PQCs, with some being stand-alone organizations and other PQCs based in organizations such as academic institutions, state health departments, state Medicaid programs, or state hospital associations.5 Despite the variety in organizational structure, the following key roles are central to all PQCs14: (1) successful PQCs have both maternal and neonatal clinical leadership to provide input for initiatives and to champion efforts among clinical providers; (2) QI experts are critical for providing QI assistance and support to clinical teams and for helping to plan and execute improvement projects; (3) a data lead or data team who is responsible for overseeing data collection systems, data management, analysis, and data reports is also crucial; (4) a program/project manager or coordinator manages the daily PQC activities, such as securing engagement of clinical teams, stakeholders, and partners; managing resource development, collaborative learning webinars, and in-person meetings; and fiscal oversight. Although funding for staffing of a PQC has been reported as a major challenge by many PQCs,5 it is crucial that key roles and responsibilities are clear and that there is a mechanism for stakeholders to provide regular input to the work. It is also important that initiatives are implemented across participating hospitals with key aims and strategies identified. Hospital teams must be engaged, supported, and provided with timely data reporting on key measures to drive the QI work and ultimately achieve sustainable improvements in care and outcomes.14

The work of PQCs involves many partners and complements other programs for synergistic impact on maternal health (Fig. 3). PQCs have partnered with AIM to support implementation of AIM maternal safety bundles at the state level through statewide hospital QI initiatives. The AIM maternal safety bundles are an important source of resources and toolkit material for PQCs.15 As state maternal mortality committees (MMRCs) have expanded across the country, PQCs are more frequently collaborating with MMRCs to use data and prevention recommendations to implement and scale up interventions for statewide, population-level improvements. This process includes using review data to prioritize and tailor initiatives on the leading causes of maternal death in the state, and the recommendations to inform interventions for improvement in maternal and perinatal outcomes.16,17

Fig. 3.

The relationship between PQCs, maternal mortality committees (MMRCs), and AIM. From Goodman DA; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Safe motherhood: anupdate from CDC. Presented at the Title V Technical Assistance Meeting. Arlington, VA. October 15, 2018.

THE ROLE OF MATERNAL-FETAL MEDICINE/OBSTETRIC PROVIDERS IN PERINATAL QUALITY COLLABORATIVE SUCCESS

Obstetric providers, including maternal-fetal medicine physicians, play a critical role in the success of PQCs. At the national level, the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine (SMFM) and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) have recognized the importance of supporting QI leadership, advocacy, and research to improve maternal and pregnancy outcomes. The American Board of Obstetrics and Gynecology (ABOG) has supported PQCs by awarding Maintenance of Certification credit for obstetric providers’ participation in approved PQC QI initiatives. At the state level, PQCs are typically led by maternal-fetal medicine/obstetric champions in partnership with neonatal and nursing colleagues, as well as QI and public health leadership. Engagement of obstetric provider leaders at the state level is critical for PQC success. There are multiple roles for obstetric leaders at the PQC level, including (1) PQC leadership, (2) initiative leadership, (3) advisory workgroup membership, (4) grand rounds speakers bureau, and (5) participation in PQC in-person meetings (Table 1).15

Table 1.

Roles for obstetric leaders in perinatal quality collaboratives15

| Roles for Obstetric Leaders | Description |

|---|---|

| PQC leadership | Provides overall clinical and/or executive leadership to the collaborative |

| Initiative leadership | Provides expert guidance for specific QI initiatives as an expert advisory panel member or clinical lead |

| Advisory workgroup member | Provides input on PQC and QI initiatives progress in regular meetings |

| Grand rounds speakers bureau | Shares QI initiative messages with hospitals across the state in as-needed presentations at hospitals |

| In-person meetings | Participates in collaborative in-person meetings, including breakout discussions |

Data from Lee King PA, Young D, Borders AEB. A framework to harness the power of quality collaboratives to improve perinatal outcomes. Clinical Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2019;62(3):606.

Regardless of PQC leadership, improvement in maternal care and outcomes does not happen unless obstetric providers are engaged in QI leadership at the hospital level. Every clinical team working on an obstetric/maternal QI initiative must have an obstetric champion and a nursing champion to be successful. Challenges with engaging obstetric champions is one of the most common barriers reported by hospital teams that are struggling to achieve QI initiative aims.14 Obstetric leaders at the state and hospital levels are instrumental for achieving provider buy-in and clinical culture change. At the clinical level, all obstetric providers can support QI initiative success by engaging in initiative education and actively supporting system and practice changes. It takes providers at all levels for PQCs to successfully improve maternal care and outcomes for all patients.

STATE PERINATAL QUALITY COLLABORATIVE IMPACT ON OBSTETRIC CARE AND OUTCOMES

Maternal Morbidity and Mortality

With maternal mortality rates not improving in the United States, maternal-fetal medicine leaders are calling for focused maternal improvement efforts to put the “M back into maternal-fetal medicine.”18 PQCs are acting on this call, resulting in most current initiatives focusing on identification and management of the primary causes of severe maternal morbidity (SMM) and mortality. Examples of successful maternal PQC initiatives addressing obstetric hemorrhage, severe maternal hypertension, maternal opioid use disorder (OUD), cardiovascular disease and venous thromboembolism, promotion of vaginal birth/safe reduction of primary cesarean section (CS), access to immediate postpartum long-acting reversible contraception (IPLARC), and access to postpartum care are discussed here.19–57

Promoting vaginal birth initiatives

Cesarean delivery is associated with greater rates of maternal morbidity and mortality than vaginal delivery.19 The cesarean delivery rate is a key quality indicator for obstetric care, and the US Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion’s Healthy People 2020 goal of a nulliparous, transverse, singleton, vertex (NTSV) CS rate is 24.7% or less.20,21 In 2014, ACOG published an obstetric care consensus on safe prevention of the primary cesarean delivery,22 and, in 2015, AIM developed the Safe Reduction of Primary Cesarean Births bundle.23

The California Maternal Quality Care Collaborative (CMQCC) piloted a Supporting Vaginal Birth QI initiative with a toolkit and implementation guide in 2015 involving 3 hospitals, which resulted in an average 18.6% reduction in NTSV CS rates.24,25 CMQCC then launched a statewide initiative and early cohorts included 56 hospitals with NTSV CS rates of more than 23.9%. Over the course of the collaborative, the NTSV CS rate decreased from 29.3% in 2015 to 25.0% in 2017 (adjusted odds ratio, 0.76; 95% confidence interval, 0.73–0.78) among participating hospitals with no adverse impact on maternal or neonatal safety.26

The Florida Perinatal Quality Collaborative (FPQC) Promoting Primary Vaginal Deliveries (PROVIDE) initiative launched in October 2017 and reduced the NTSV CS rate by 7% across 42 participating hospitals by 2019.27 FPQC enhanced and expanded their initiative and launched PROVIDE 2.0 to 76 hospitals to continue work toward their aim of a 20% reduction across participating hospitals.28,29 PQC initiatives to promote vaginal birth will support hospitals in achieving Healthy People 2020 goals.21

Postpartum hemorrhage

Postpartum hemorrhage is a leading cause of maternal mortality in the week after delivery and many of these deaths are preventable.30,31 ACOG expanded guidance on postpartum hemorrhage to include recommendations for hospital-wide standard protocols and treatment algorithms.32 AIM developed the Obstetric Hemorrhage bundle,33 including resources from the ACOG District II Safe Motherhood Initiative bundle34 and PQC-developed toolkits.35,36 The FPQC Obstetric Hemorrhage Initiative ran from December 2013 to April 2015 and included 35 hospitals.37 Participating hospitals improved, from baseline to the initiative end, across all process measures, including increasing clinical staff (100% trained) and provider education (71% trained), completion of risk assessment for obstetric hemorrhage (from 11% to 75%), documentation of active management of the third stage of labor (from 55% to 87%), and quantification of blood loss for vaginal deliveries (from 43% to 76%).37 The FPQC found that obstetric and nursing leadership and staff buy-in, the strength of the evidence for treatment guidelines, adaptability of QI tools across hospital settings, and organization of the resources and collaborative support components contributed to successful hospital implementation.38

The CMQCC Obstetric Hemorrhage Initiative was conducted from January 2015 to March 2016 and reduced SMM among women with hemorrhage in 99 collaborative hospitals by 20.8% from baseline to the last half of the initiative.39 The CMQCC showed that participating in a statewide collaborative postpartum hemorrhage QI initiative achieved a significantly greater reduction in SMM than was achieved in women with hemorrhage at hospitals not participating in the collaborative.39

Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy and the postpartum

Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy are another major cause of maternal mortality and many deaths are preventable.30,31 ACOG provides current guidance on emergent therapy for acute-onset severe hypertension during pregnancy and the postpartum, which recommends urgent treatment (within 30–60 minutes) with antihypertensive therapy.40 These recommendations are supported in the AIM Severe Hypertension in Pregnancy bundle.41 The CMQCC’s initial preeclampsia initiative launched in 2013 and lasted 2 years. There were 24 participating hospitals that achieved a 42% increase in treatment of severe hypertension, a 34% decrease in SMM overall, and 48% decrease in SMM excluding hemorrhage from baseline (6 months preinitiative) to the 6-month period 9 to 15 months after the start of the initiative.42 CMQCC expanded this work through the California Partnership for Maternal Safety collaborative with 126 hospitals working from 2013 to 2016 to help implement CMQCC toolkits for a standard approach to preeclampsia and obstetric hemorrhage.43

The Illinois Perinatal Quality Collaborative (ILPQC) Severe Maternal Hypertension Initiative launched in May 2016 and lasted through December 2017 with 102 hospitals. Preliminary results in the first year of the initiative show an increased percentage of patients with new-onset severe hypertension treated within 60 minutes from 41% at baseline to 79% in the first year of the initiative,44 with final results pending publication (Borders and colleagues, submitted for publication). Preliminary results also showed an increase in the percentage of cases receiving preeclampsia education at discharge, from 37% to 81%; scheduling follow-up appointments within 10 days of discharge, from 53% to 75%; and debrief after event, from 2% to 44%.44 PQC initiatives to address severe maternal hypertension will support hospital work toward The Joint Commission Standards effective July 2020.11,45

Opioid use disorder in pregnancy

Maternal OUD at delivery more than quadrupled from 1999 to 2014.46 Mental health and substance abuse are a leading cause of maternal death.47 PQCs are working to help hospitals address variation in the quality of care for women with OUD in obstetric settings and during the delivery admission, including promotion of QI strategies that support implementation of national ACOG guidelines to improve maternal outcomes for women with OUD.48 The AIM Obstetric Care for Women with OUD Bundle includes resources on screening, brief intervention with assessment of readiness for medication-assisted treatment (MAT) and referral to recovery treatment, obstetric care guidelines including pain management, naloxone counseling, screening for hepatitis C, educating women on engaging in newborn care, and care coordination with warm hand-offs.49 In a pilot by the Northern New England Perinatal Quality Improvement Network (NNEPQIN), 8 hospitals integrated a perinatal clinical care checklist for women with OUD over 13 months in 2017 and 2018. Using collaborative improvement methods, participating hospitals incorporated the checklist in 78% of medical records, and they significantly increased access to naloxone (11% to 36%) and breastfeeding counseling (51% to 72%) for women with OUD. These early improvements highlighted the feasibility of a PQC to improve clinical care for women with OUD.50

The ILPQC Mothers and Newborns Affected by Opioids (MNO) initiative launched in May 2018 and is currently in progress, with 101 participating hospitals implementing ACOG guidelines with QI tools developed by ILPQC, including protocols, clinical care algorithms, and checklists for patients with OUD; provider and patient education materials; and case review and debrief with the clinical team for every patient with OUD.51 MNO folders are being used as a QI strategy and have algorithms, checklists, provider counseling scripts, and patient education materials available in prenatal sites and delivery locations whenever a patient with OUD is identified. In May 2019, 1 year after implementation, hospitals reported that women screened with validated screening tools for substance use disorder on labor and delivery increased from 2% at baseline to 52%.52 The percentage of hospitals with greater than or equal to 70% of women with OUD on MAT at delivery increased from 41% to 55% and the percentage of hospitals with greater than or equal to 70% of women with OUD linked to recovery services at delivery increased from 15% to 41%.52 These early improvements show that a statewide collaborative can support hospital efforts to improve care and outcomes for women with OUD.

Immediate postpartum long-acting reversible contraception

Improved access to immediate postpartum long-acting reversible contraception (IPLARC) in the immediate postpartum period reduces short-interval pregnancies.53 In 2016, ACOG supported hospital implementation of IPLARC as an effective contraception option for women and an opportunity to reduce barriers to postpartum contraception access.54 PQCs launched initiatives to help hospitals to offer IPLARC, and many state public insurers have now unbundled billing of IPLARC placement from delivery. The South Carolina Birth Outcomes Initiative (SCBOI) launched an initiative to support hospital implementation of IPLARC and found, through review of Medicaid data charges, that 17% of Medicaid patients chose IPLARC during their delivery admission.55 The Tennessee Initiative for Perinatal Quality (TIPQC) IPLARC initiative launched in 2018. Five of the 6 hospitals participating in the initiative were offering IPLARC after 1 year and provided 2012 LARC devices to women who chose IPLARC.56 The ILPQC IPLARC initiative launched a first wave in May 2018 with 13 hospitals; only 3 were offering IPLARC at baseline and all 13 were providing IPLARC with all key components implemented by August 2019. ILPQC launched a second wave in May 2019, with 14 hospitals working to provide access to IPLARC by May 2020. To date, hospitals providing access to IPLARC cover nearly 40% of Illinois deliveries, with 5% of patients choosing IPLARC and 1907 women benefiting from improved access by receiving IPLARC.57 PQCs have worked closely with state Medicaid and private insurers to address reimbursement issues and increase access to IPLARC as an available contraception option.

Emerging initiatives to address maternal morbidity and mortality

PQCs are developing other initiatives to address maternal morbidity and mortality. More than half of maternal deaths occur in the postpartum period and the recent ACOG guidelines on the fourth trimester have renewed focus on optimizing postpartum care.30,58 ILPQC has recently launched an Improving Postpartum Access to Care (IPAC) initiative with 17 hospitals to implement universal early postpartum visits and standardize postpartum safety education, including signs and symptoms for when to seek care, benefits of an early maternal health safety check, and healthy pregnancy spacing.57 Cardiovascular conditions are a leading cause of maternal death, with up to 68% deemed preventable.30,59 CMQCC recently developed an Improving Health Care Response to Cardiovascular Disease in Pregnancy and Postpartum toolkit with some early validation tests of the cardiovascular disease algorithm in a birthing hospital.60,61 Obstetric venous thromboembolism is another leading cause of SMM and mortality amenable to prevention, with a CMQCC toolkit available.30,62

Maternity Care Impact on Birth and Preterm Birth

The infant mortality was 5.79 per 1000 births in 2017.63 Preterm birth is a leading cause of infant mortality.64 Many PQCs initially formed as a strategy to reduce prematurity, and much of their early and current work focused on initiatives to reduce preterm birth and improve preterm birth outcomes. Initiatives focused on birth and preterm birth include reducing early elective deliveries before 39 weeks, increasing corticosteroid administration for eligible women, increasing progesterone administration to reduce preterm births, and optimizing breastfeeding.

Reducing elective delivery before 39 weeks

Elective, or non–medically indicated, deliveries before 39 weeks (also referred to as EED [early elective deliveries]) are associated with unnecessary neonatal morbidity and adverse long-term outcomes.65,66 The March of Dimes (MOD) California Chapter worked with CMQCC to develop a toolkit to support hospital implementation of ACOG guidelines to reduce EED.67,68 The MOD formed the Big 5 State Perinatal Collaborative with PQC and other state leaders in California, Florida, Illinois, New York, and Texas to implement the toolkit in 25 hospitals from September 2010 to February 2012. Participating hospitals reduced EED from 27.8% to 4.8% in 1 year.69

Other PQCs also launched initiatives to help hospitals reduce EED. The Ohio Perinatal Quality Collaborative (OPQC) 39-Weeks Delivery Charter Project launched in September 2008 with 20 hospitals and decreased EED from 25% in July 2008 to less than 5% by August 2009.70,71 The Perinatal Quality Collaborative of North Carolina (PQCNC) 39 Weeks Project launched in 2009 with 33 hospitals. By the end of the project in 2010, EED before 39 weeks decreased from 2% to 1.1%, and the proportion of EED among all scheduled early-term deliveries decreased from 23.63% to 16.19%.72 The New York State Perinatal Quality Collaborative (NYSPQC) Obstetrical Improvement Project to reduce non–medically indicated deliveries launched in 2012 with 96 hospitals.73 Non–medically indicated delivery rates decreased among 17 regional perinatal centers in phase 1 from 24.8% in September 2010 to 6.7% by the start of phase 2 (June 2012) and 0.6% by the project end (November 2014).74 This early PQC work on EED showed the value of the collaborative infrastructure.

Increasing antenatal corticosteroid administration for eligible women

Corticosteroid administration before anticipated preterm birth is associated with decreased neonatal morbidity and mortality, including lower severity and frequency of respiratory distress syndrome, necrotizing enterocolitis, and death.75 The MOD Big 5 State Perinatal Collaborative Antenatal Corticosteroid Initiative in California, Florida, Illinois, New York, and Texas launched in January 2016 to develop resources to help 39 participating hospitals improve standardized identification of eligible patients and timely administration of antenatal corticosteroids (ACT).76 By the end of the initiative in February 2017, participating hospitals reported a significant increase in use of a standard process for identification of eligible patients (59% to 88% of hospitals) and reduction in barriers to ACT administration, including standardized protocol (24% to 60%), uniform use (38% to 59%), and systems to track administration (38% to 59%).76

The California Perinatal Quality Care Collaborative (CPQCC) project on ACT administration, launched in 1999 with 25 hospitals, found an increased rate in ACT administration from 76% in 1998 to 86% in 2001.77 Higher rates of ACT administration were sustained among participating hospitals compared with nonparticipating hospitals (85% vs 69%).78 The OPQC Antenatal Corticosteroids Initiative launched in October 2011 with 18 hospitals and found high ACT administration rates over the course of the initiative (91.8%), achieving and maintaining the 90% goal by the second month of the initiative.79 Hospital teams reported that a high-reliability culture and process, interdisciplinary engagement, and awareness of the evidence of the benefits of ACT contributed to their successful implementation of ACT.80

Progesterone to reduce premature births

The use of progesterone among women at risk for preterm birth can reduce the incidence of preterm birth.81 The OPQC Progesterone Project launched in 2014 with 23 hospitals to support implementation of ACOG guidelines and decreased births before 32 weeks’ gestation by 8.0% in participating hospitals compared with by 6.6% in all hospitals in the state. There was a 13% decrease in births before 32 weeks’ gestation to women with prior preterm birth.82,83

Optimizing breastfeeding

ACOG provides guidelines for clinical management of breastfeeding to provide education, including information on improved maternal and infant health outcomes associated with breastfeeding, as well as support for breastfeeding.84,85 The PQCNC Human Milk and Breastfeeding Initiative launched in late 2010 to support (1) newborn critical care center efforts to supply mother’s milk to newborns less than 1500 g, and (2) maternity care center efforts to increase exclusive breastfeeding for term infants. Participating hospitals reported increased breastfeeding support by 425%, increased skin-to-skin contact days by 450%, and a 34% increase in exclusive breastfeeding rates through 28 days by January 2013.86 The TIPQC Breastfeeding Promotion: Delivery and Postpartum initiative launched in 2012 with 11 hospitals. By 2013, they increased the aggregate Joint Commission Perinatal Care Performance Measure (PC)-05 measure of exclusive breast milk feeding from 37% to 42%. Wave 2 launched in 2014 with additional hospitals for a total of 18 hospital teams achieving improvement in aggregate Joint Commission PC-05 rates from 40.9% to 44.8% by the end of 2015.87

Birth Equity

The burden of maternal and infant morbidity and mortality in the United States is disproportionately borne by African Americans. African American women are 3 times as likely as white women to die in pregnancy through 1 year postpartum from a pregnancy-related cause,4 and are more likely to deliver an infant preterm: 14% compared with 9% for non-Hispanic white women.88 There is also a 12% difference in the rate of breastfeeding initiation between non-Hispanic black and white women in the United States.27 PQCs are working to address these disparities across initiatives and are exploring ways to develop targeted initiatives on birth equity, including resources from the recent AIM Reduction of Peripartum Racial/Ethnic Disparities bundle.89 In 2018, the CMQCC launched the California Birth Equity Collaborative, starting with a pilot initiative working with 5 hospitals and community stakeholders to develop and test key resources to support hospital system and culture change to promote birth equity, including a patient-reported experience metric, online educational resources, and best-practice interventions.90 Other PQCs are working to develop key strategies for promoting birth equity, including providing respectful care; addressing social determinants of health; engaging patients, communities, and birth partners; and engaging and educating providers with incorporation of implicit bias training.

SUMMARY

The goal of PQCs is to partner with hospitals, providers, nurses, patients, public health, and other stakeholders, using QI strategies to implement evidence-based practices to improve outcomes for mothers and newborns.5 As states across the country develop and expand PQCs, it is important to consider strategies to increase the capacity of PQCs to succeed.15

It must be recognized that PQCs are at varying levels of development. Although most states have an identified PQC organization, many PQCs currently lack the personnel and infrastructure to function optimally. Thus, many have yet to reach their maximum potential to make measurable improvements in statewide maternal and infant care and outcomes. Although many PQCs are clearly making a difference to address the current challenges in maternal and newborn health, significant work remains to get every PQC to the level where they can make sustainable and significant population-level improvements in maternal health outcomes.

Progress in PQC development, sustainability, and impact on maternal outcomes depends on several key factors. PQC development and sustainability are built on adequate staffing and infrastructure. Progress also depends on the involvement of critical stakeholders and champions to provide leadership for effective QI initiatives, and the optimal engagement of clinical teams to achieve sustainable improvements in care. In addition, key partnerships at the state and federal levels can help to address maternal morbidity and mortality, including (1) ongoing collaborations with AIM on implementation of maternal safety bundles, which are a key resources for QI initiatives; (2) expanding ties at the state level with maternal mortality review committees and departments of public health to promote implementation of maternal mortality prevention strategies and efforts to address birth equity; and (3) ongoing support at the national and state levels from key stakeholders (eg, national obstetric and nursing organizations, hospital associations, maternal health partners, and payers). The NNPQC, supported by the CDC and coordinated by NICHQ, is another important resource for ongoing technical support for PQCs, creating opportunities for collaborative learning between early and more developed PQCs.

PQCs can make a difference and improve a range of outcomes. Given the urgent challenges facing maternal and newborn health across the country, there is a clear need for additional efforts to develop and sustain PQCs nationwide. PQCs can be well positioned to achieve the goal of sustainable improvements in maternal and newborn care and outcomes.

KEY POINTS.

Perinatal quality collaboratives (PQCs) are an effective intervention to improve maternal health outcomes.

Physician, nursing, and public health champions provide leadership for effective quality improvement initiatives, optimally engage hospital teams, and achieve sustainable improvements in care.

Given the urgent challenges facing maternal and newborn health across the country, an emphasis on developing and sustaining PQCs nationwide is needed.

Promotion of partnerships at the federal, state, and local levels is important to ensure effective collaboration to address the urgent need to improve maternal health.

Best Practices.

What is the current practice? State-based perinatal quality collaboratives

State-based PQCs have shown that the application of collaborative improvement science methods can lead to better perinatal health outcomes by:

Advancing evidence-informed clinical practices and processes using QI strategies.

Addressing gaps by implementing statewide initiatives working with clinical teams, obstetric provider and nursing leaders, patients and families, public health officials, and other stakeholders to spread best practices, reduce variation in practice, reduce health care inequities, and optimize efforts to improve perinatal care and outcomes.

What changes in current practice are likely to improve outcomes?

Use of the collaborative learning model to share knowledge and experiences among clinical teams working toward unified objectives for improvement.

Use of rapid-response data by clinical teams to track and compare progress toward meeting those objectives.

Provision of QI science support and assistance to clinical teams.

Engage obstetric provider champions at the state, hospital, and clinical levels to promote buy-in and achieve clinical culture change.

Major recommendations

Given the urgent challenges facing maternal and newborn health across the country, an emphasis on developing and sustaining PQCs nationwide is needed.

Physician, nursing, and public health champions provide leadership for effective QI initiatives, optimally engage hospital teams, and achieve sustainable improvements in care.

Key partnerships can be promoted with state and federal efforts to address maternal morbidity and mortality to ensure effective collaboration.

Summary sentence

PQCs in many states are an effective intervention to improve maternal health outcomes. With appropriate staffing, infrastructure, and partnerships, PQCs can be well positioned to achieve the goal of sustainable improvements in maternal and newborn care and outcomes nationwide.

Disclaimer:

The findings and conclusions in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Footnotes

DISCLOSURE

The authors disclose no commercial or financial conflicts of interest. ILPQC, Dr A.E.B. Borders, principal investigator, is funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Illinois Department of Public Health, Illinois Department of Human Services, University of Illinois at Chicago, Pritzker Family Foundation, and the Alliance for Innovation on Maternal Health.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hoyert DL, Minino AM. Maternal mortality in the United States: changes in coding, publication, and data release, 2018. Natl Vital Stat Rep 2020;69:1–18. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr69/nvsr69_02-508.pdf. Accessed January 30, 2020. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ely DM, Driscoll AK. Infant mortality in the United States, 2017: data from the period linked birth/infant death file. Natl Vital Stat Rep 2019;68(10):1–20. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr68/nvsr68_10-508.pdf. Accessed August 1, 2019. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development. Infant mortality rates. 2020. Available at: https://data.oecd.org/healthstat/infant-mortality-rates.htm.

- 4.Petersen EE, Davis NL, Goodman D, et al. Racial/ethnic disparities in pregnancy-related deaths - United States, 2007–2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2019;68(35):762–5. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/68/wr/mm6835a3.htm. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Henderson ZT, Ernst K, Simpson KR, et al. The National Network of State Perinatal Quality Collaboratives: a growing movement to improve maternal and infant health. J Womens Health 2018;27(2):123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gould JB. The role of regional collaboratives: the California Perinatal Quality Care Collaborative model. Clin Perinatol 2010;37(1):71–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. State perinatal quality collaboratives. 2020. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/maternalinfanthealth/pqc-states.html. Accessed March 5, 2020.

- 8.Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Quality of Health Care in America. To err is human: building a safer health system. 2001. Available at: https://www.nap.edu/catalog/9728/to-err-is-human-building-a-safer-health-system.

- 9.Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Quality of Health Care in America. Crossing the quality chasm: a new health system for the 21st century. 2001. Available at: https://www.nap.edu/catalog/25152/crossing-the-global-quality-chasm-improving-health-care-worldwide.

- 10.Abraham MR, Ashton DM, Badura MB, et al. Toward improving the outcome of pregnancy III: enhancing perinatal health through quality, safety and performance initiatives. 2010. Available at: http://www.marchofdimes.org/materials/toward-improving-the-outcome-of-pregnancy-iii.pdf.

- 11.The Joint Commission. Provision of care, treatment, and services standards for maternal safety. R3 Report: Requirement, Rationale, Reference. 2019(R3). Available at: https://www.jointcommission.org/-/media/tjc/documents/standards/r3-reports/r3_24_maternal_safety_hap_9_6_19_final1.pdf. Accessed August 21, 2019.

- 12.Mahoney J. The Alliance for Innovation in Maternal Health Care: a way forward. Clin Obstet Gynecol 2018;61(2):400–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Institute for Healthcare Improvement. The breakthrough series: IHI’s collaborative model for achieving breakthrough improvement. Innovation Series White Paper. 2003. Available at: http://www.ihi.org/resources/Pages/IHIWhitePapers/TheBreakthroughSeriesIHIsCollaborativeModelforAchievingBreakthroughImprovement.aspx.

- 14.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Developing and sustaining perinatal quality collaboratives - a resource guide for states. 2016. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/maternalinfanthealth/pdf/Best-Practices-for-Developing-and-Sustaining-Perinatal-Quality-Collaboratives_tagged508.pdf.

- 15.Lee King PA, Young D, Borders AEB. A framework to harness the power of quality collaboratives to improve perinatal outcomes. Clin Obstet Gynecol 2019;62(3):606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mehta PK, Kieltyka L, Bachhuber MA, et al. Racial inequities in preventable pregnancy-related deaths in Louisiana, 2011-2016. Obstet Gynecol 2020;135(2):276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goodman DA; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Safe motherhood: an update from CDC. Presented at the Title V Technical Assistance Meeting. Arlington, VA. October 15, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 18.D’Alton ME, Bonanno CA, Berkowitz RL, et al. Putting the “M” back in maternal-fetal medicine. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2013;208(6):442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Clark SL, Belfort MA, Dildy GA, et al. Maternal death in the 21st century: causes, prevention, and relationship to cesarean delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2008;199(1):36.e1–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.The Joint Commission. Specifications manual for Joint Commission national quality core measures (2019A); perinatal care. 2019. Available at: https://manual.jointcommission.org/releases/TJC2019A/PerinatalCare.html. Accessed February 7, 2020.

- 21.Healthy People. MICH-7.1 Reduce cesarean births among low-risk women with no prior births. 2019. Available at: https://www.healthypeople.gov/node/4900/data_details#revision_history_header. Accessed February 9, 2020.

- 22.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine. Obstetric care consensus no. 1: safe prevention of the primary cesarean delivery. Obstet Gynecol 2014;123:693–711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.. Lagrew DC, Low LK, Brennan R, et al. National partnership for maternal safety: consensus bundle on safe reduction of primary cesarean births-supporting intended vaginal births. Obstet Gynecol 2018;131(3):503–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Smith H, Peterson N, Lagrew D, et al. Toolkit to support vaginal birth and reduce primary cesareans. 2017. Available at: https://www.cmqcc.org/VBirthToolkitResource. Accessed February 9, 2020.

- 25.Lagrew DC, Mills M, Mikes K, et al. 822: rapid reduction of the NTSV CS rate in multiple community hospitals using a multi-dimensional QI approach. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2017;216(1):S471–2. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Main EK, Chang S-C, Cape V, et al. Safety assessment of a large-scale improvement collaborative to reduce nulliparous cesarean delivery rates. Obstet Gynecol 2019;133(4):613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Division of Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Obesity. Data, Trend and Maps [online]. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/nccdphp/dnpao/data-trends-maps/index.html. Accessed May 18, 2020.

- 28.Florida Perinatal Quality Collaborative. Promoting primary vaginal deliveries initiative, Provide 2.0: the next generation. 2019. Available at: https://health.usf.edu/-/media/Files/Public-Health/Chiles-Center/FPQC/PROVIDEWebinar-PROVIDE2-May2019.ashx?la=en&hash=60D6DEC3C9205DB38333C58516424A8C627A06AA. Accessed February 9, 2020.

- 29.Bronson EA. “Always PROVIDE”: 76 Florida hospitals commit to promote primary vaginal deliveries. 2019. Available at: https://hscweb3.hsc.usf.edu/health/publichealth/news/always-provide-76-florida-hospitals-commit-to-promote-primary-vaginal-deliveries/.

- 30.Petersen EE, Davis NL, Goodman D, et al. Vital signs: pregnancy-related deaths, United States, 2011-2015, and strategies for prevention, 13 states, 2013-2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2019;68:423–9. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/vitalsigns/maternal-deaths/. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Main EK, McCain CL, Morton CH, et al. Pregnancy-related mortality in California: causes, characteristics, and improvement opportunities. Obstet Gynecol 2015;125(4):938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shields LE. Practice bulletin No. 183 summary: postpartum hemorrhage. Obstet Gynecol 2017;130(4):923–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Main EK, Goffman D, Scavone BM, et al. National partnership for maternal safety: consensus bundle on obstetric hemorrhage. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs 2015;44(4):462–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Burgansky A, Montalto D, Siddiqui NA. The safe motherhood initiative: the development and implementation of standardized obstetric care bundles in New York. Semin Perinatol 2016;40(2):124–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Florida Perinatal Quality Collaborative. Obstetric hemorrhage initiative toolkit. 2014. Available at: https://health.usf.edu/publichealth/chiles/fpqc/OHI. Accessed February 9, 2020.

- 36.Lyndon A, Lagrew D, Shields L, et al. Improving health care response to obstetric hemorrhage version 2.0: a California quality improvement toolkit. 2015. Available at: https://www.cmqcc.org/resources-tool-kits/toolkits/ob-hemorrhage-toolkit. Accessed February 9, 2020.

- 37.Florida Perinatal Quality Collaborative. Obstetric hemorrhage initiative final data report. 2015. Available at: https://health.usf.edu/-/media/Files/Public-Health/Chiles-Center/FPQC/FinalOHIDataReport.ashx?la=en&hash=F2E3E479F5FA7AFFFD4EE3D3C3CBCDDE737CFE00.

- 38.Vamos CA, Cantor A, Thompson EL, et al. The obstetric hemorrhage initiative (OHI) in Florida: the role of intervention characteristics in influencing implementation experiences among multidisciplinary hospital staff. Matern Child Health J 2016;20(10):2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Main EK, Cape V, Abreo A, et al. Reduction of severe maternal morbidity from hemorrhage using a state perinatal quality collaborative. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2017;216(3):298.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Emergent therapy for acute-onset, severe hypertension during pregnancy and the postpartum period. ACOG committee opinion no. 767. Obstet Gynecol 2019;133:e174–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bernstein PS, Martin JN, Barton JR, et al. Consensus bundle on severe hypertension during pregnancy and the postpartum period. J Midwifery Womens Health 2017;62(4):493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shields L, Kilpatrick S, Melsop K, et al. 103: timely assessment and treatment of preeclampsia reduces maternal morbidity. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2015;212(1):S69. [Google Scholar]

- 43.California Maternal Quality Care Collaborative. Preeclampsia collaboratives. 2020. Available at: https://www.cmqcc.org/qi-initiatives/preeclampsia/preeclampsia-collaboratives. Accessed February 9, 2020.

- 44.Lee King P, Keenan-Devlin L, Gordon C, et al. 4: reducing time to treatment for severe maternal hypertension through statewide quality improvement. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2018;218(1):S4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gavigan S, Rosenbergy N, Hurlbert J. Proactively preventing maternal hemorrhage-related deaths. Leading Hospital Improvement. 2019. Available at: https://www.jointcommission.org/en/resources/news-and-multimedia/blogs/leading-hospital-improvement/2019/11/proactively-preventing-maternal-hemorrhagerelated-deaths/. Accessed February 20, 2020.

- 46.Haight S, Ko J, Tong VT, et al. Opioid use disorder documented at delivery hospitalization — United States, 1999–2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2018;67(31):845–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.deaths. BUSctrapm. Report from nine maternal mortality review committees. 2018. Available at: https://www.cdcfoundation.org/sites/default/files/files/ReportfromNineMMRCs.pdf.

- 48.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Opioid use and opioid use disorder in pregnancy. committee opinion no. 711. Obstet Gynecol 2017;130:e81–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Krans EE, Campopiano M, Cleveland LM, et al. National partnership for maternal safety: consensus bundle on obstetric care for women with opioid use disorder. Obstet Gynecol 2019;134(2):365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.. Goodman D, Zagaria A, Flanagan V, et al. Feasibility and acceptability of a checklist and learning collaborative to promote quality and safety in the perinatal care of women with opioid use disorders. J Midwifery Womens Health 2019;64(1):104–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Illinois Perinatal Quality Collaborative. Mothers and newborns affected by opioids - OB. 2018. Available at: https://ilpqc.org/mothers-and-newborns-affected-by-opioids-ob-initiative/. Accessed February 9, 2020.

- 52.Borders A, Lee King P, Weiss D, et al. 160: improving outcomes for mothers affected by opioids through statewide quality improvement. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2020;222(1):S116. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kroelinger CDMI, DeSisto CL, Estrich C, et al. State-identified implementation strategies to increase uptake of immediate postpartum long-acting reversible contraception policies. J Womens Health 2018;28(3):346–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Immediate postpartum long-acting reversible contraception. Obstet Gynecol 2016;128:e32–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Association of State and Territorial Health Officials. South Carolina increases access to LARCs immediately postpartum to reduce unintended pregnancy. 2017. Available at: https://www.astho.org/Maternal-and-Child-Health/South-Carolina-Increases-Access-to-LARCs-Immediately-Postpartum-to-Reduce-Unintended-Pregnancy/.

- 56.Lacy MM, McMurtry Baird S, Scott TA, et al. Statewide quality improvement initiative to implement immediate postpartum long-acting reversible contraception. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2020;222(4, Supplement):S910.e1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Illinois Perinatal Quality Collaborative. ILPQC stronger together: 2019 review and onward to 2020. 2019. Available at: https://ilpqc.org/ILPQC%202020%2B/Annual%20Conferences/2019%20Annual%20Conference/1_Borders%20et%20al_ILPQC%20A%20Year%20in%20Review_%28Grand%20Ballroom%20A-F%29_ALL%20FINAL_11.1.2019.pdf. Accessed March 10, 2020.

- 58.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Optimizing postpartum care. ACOG committee opinion no. 736. Obstet Gynecol 2018;131:e140–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hameed AB, Lawton ES, McCain CL, et al. Pregnancy-related cardiovascular deaths in California: beyond peripartum cardiomyopathy. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2015;213(3):379.e1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hameed AB, Morton CH, Moore A. Improving health care response to cardiovascular disease in pregnancy and postpartum. 2017. Available at: https://www.cmqcc.org/resources-toolkits/toolkits/improving-health-care-response-cardiovascular-disease-pregnancy-and.

- 61.Crosland BA, Blumenthal EA, Senderoff DS, et al. 833: heart of the matter: preliminary-analysis of the California maternal quality care collaborative cardiovascular disease toolkit. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2019;220(1):S544. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hameed AB, Friedman A, Peterson N, et al. Improving health care response to maternal venous thromboembolism. 2018. Available at: https://www.cmqcc.org/resources-toolkits/toolkits/improving-health-care-response-maternal-venous-thromboembolism.

- 63.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Infant mortality. 2019. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/maternalinfanthealth/infantmortality.htm#causes. Accessed January 30, 2020.

- 64.Kochanek KDM SL, Xu J, Arias E. Deaths: final data for 2017. Natl Vital Stat Rep 2019;68(9):1–77. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr68/nvsr68_09-508.pdf. Accessed June 24, 2019. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Clark SL, Miller DD, Belfort MA, et al. Neonatal and maternal outcomes associated with elective term delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2009;200(2):156.e1–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Noble KG, Fifer WP, Rauh VA, et al. Academic achievement varies with gestational age among children born at term. Pediatrics 2012;130(2):E257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Main E, Oshiro B, Chagolla B, et al. Elimination of non-medically indicated (elective) deliveries before 39 weeks gestational age. 2010. Available at: https://www.marchofdimes.org/professionals/less-than-39-weeks-toolkit.aspx.

- 68.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Avoidance of nonmedically indicated early-term deliveries and associated neonatal morbidities. ACOG committee opinion no. 765. Obstet Gynecol 2019;133:e156–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Oshiro BT, Kowalewski L, Sappenfield W, et al. A multistate quality improvement program to decrease elective deliveries before 39 weeks of gestation. Obstet Gynecol 2013;121(5):1025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Donovan EF, Lannon C, Bailit J, et al. A statewide initiative to reduce inappropriate scheduled births at 36 0/7–38 6/7 weeks’ gestation. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2010;202(3):243.e1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Bailit JL, Iams J, Silber A, et al. Changes in the indications for scheduled births to reduce nonmedically indicated deliveries occurring before 39 weeks of gestation. Obstet Gynecol 2012;120(2 Pt 1):241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Berrien K, Devente J, French A, et al. The perinatal quality collaborative of North Carolina’s 39 weeks project: a quality improvement program to decrease elective deliveries before 39 weeks of gestation. N C Med J 2014;75(3):169–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Perinatal quality collaborative success story: New York State Perinatal Quality Collaborative increases the proportion of babies born full-term. 2014. Available at: https://www.albany.edu/cphce/nyspqcpublic/success_stories_8-2014.pdf.

- 74.Kacica M, Glantz J, Xiong K, et al. A statewide quality improvement initiative to reduce non-medically indicated scheduled deliveries. Matern Child Health J 2017;21(4):932–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Crowley P. Prophylactic corticosteroids for preterm birth. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2000;(2):CD000065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.March of Dimes. Optimize the administration of antenatal corticosteroids (ACS) for impending preterm births – update. 2019. Available at: https://patientsafetymovement.org/commitments/optimize-the-administration-of-antenatal-corticosteroids-acs-for-impending-preterm-births-update-06-24-19/.

- 77.Wirtschafter DD, Danielsen BH, Main EK, et al. Promoting antenatal steroid use for fetal maturation: results from the California Perinatal Quality Care Collaborative. J Pediatr 2006;148(5):606–12.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Lee HC, Lyndon A, Blumenfeld YJ, et al. Antenatal steroid administration for premature neonates in California. Obstet Gynecol 2011;117(3):603–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ohio Perinatal Quality Collaborative Writing Committee. A statewide project to promote optimal use of antenatal corticosteroids (ANCS). Am J Obstet Gynecol 2013;208(1):S224. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kaplan HC, Sherman SN, Cleveland C, et al. Reliable implementation of evidence: a qualitative study of antenatal corticosteroid administration in Ohio hospitals. BMJ Qual Saf 2016;25(3):173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Hassan SS, Romero R, Vidyadhari D, et al. Vaginal progesterone reduces the rate of preterm birth in women with a sonographic short cervix: a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2011;38(1):18–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Iams JD, Applegate MS, Marcotte MP, et al. A state wide progestogen promotion program in Ohio. Obstet Gynecol 2017;129(2):337–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Prediction and prevention of preterm birth. practice bulletin no. 130. Obstet Gynecol 2012;120:964–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Optimizing support for breastfeeding as part of obstetric practice. ACOG committee opinion no. 756. Obstet Gynecol 2018;132:e187–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Section on Breastfeeding. Breastfeeding and the use of human milk. Pediatrics 2012;129(3):e827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Perinatal Quality Collaborative North Carolina. Human milk and breastfeeding: increasing exclusivity in the hospital. 2013. Available at: https://www.pqcnc.org/initiatives/milk-nccc. Accessed February 9, 2020.

- 87.Tennessee Initiative for Perinatal Quality Care. Breastfeeding promotion: delivery and postpartum. 2016. Available at: https://tipqc.org/breastfeeding-promotion/. Accessed February 9, 2020.

- 88.Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Osterman MJK. Births in the United States, 2018. NCHS Data Brief 2019;(346):1–8. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db346-h.pdf. [PubMed]

- 89.Howell EA, Brown H, Brumley J, et al. Reduction of peripartum racial and ethnic disparities: a conceptual framework and maternal safety consensus bundle. Obstet Gynecol 2018;131(5):770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.California Maternal Quality Care Collaborative. Birth equity: California birth equity collaborative: improving care, experiences and outcomes for black mothers. 2019. Available at: https://www.cmqcc.org/qi-initiatives/birth-equity. Accessed March 3, 2020.