Abstract

Background

Midwives are primary providers of care for childbearing women globally and there is a need to establish whether there are differences in effectiveness between midwife continuity of care models and other models of care. This is an update of a review published in 2016.

Objectives

To compare the effects of midwife continuity of care models with other models of care for childbearing women and their infants.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Trials Register, ClinicalTrials.gov, and the WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) (17 August 2022), as well as the reference lists of retrieved studies.

Selection criteria

All published and unpublished trials in which pregnant women are randomly allocated to midwife continuity of care models or other models of care during pregnancy and birth.

Data collection and analysis

Two authors independently assessed studies for inclusion criteria, scientific integrity, and risk of bias, and carried out data extraction and entry. Primary outcomes were spontaneous vaginal birth, caesarean section, regional anaesthesia, intact perineum, fetal loss after 24 weeks gestation, preterm birth, and neonatal death. We used GRADE to rate the certainty of evidence.

Main results

We included 17 studies involving 18,533 randomised women. We assessed all studies as being at low risk of scientific integrity/trustworthiness concerns. Studies were conducted in Australia, Canada, China, Ireland, and the United Kingdom. The majority of the included studies did not include women at high risk of complications. There are three ongoing studies targeting disadvantaged women.

Primary outcomes

Based on control group risks observed in the studies, midwife continuity of care models, as compared to other models of care, likely increase spontaneous vaginal birth from 66% to 70% (risk ratio (RR) 1.05, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.03 to 1.07; 15 studies, 17,864 participants; moderate‐certainty evidence), likelyreduce caesarean sections from 16% to 15% (RR 0.91, 95% CI 0.84 to 0.99; 16 studies, 18,037 participants; moderate‐certainty evidence), and likely result in little to no difference in intact perineum (29% in other care models and 31% in midwife continuity of care models, average RR 1.05, 95% CI 0.98 to 1.12; 12 studies, 14,268 participants; moderate‐certainty evidence). There may belittle or no difference in preterm birth (< 37 weeks) (6% under both care models, average RR 0.95, 95% CI 0.78 to 1.16; 10 studies, 13,850 participants; low‐certainty evidence).

We are very uncertain about the effect of midwife continuity of care models on regional analgesia (average RR 0.85, 95% CI 0.79 to 0.92; 15 studies, 17,754 participants, very low‐certainty evidence), fetal loss at or after 24 weeks gestation (average RR 1.24, 95% CI 0.73 to 2.13; 12 studies, 16,122 participants; very low‐certainty evidence), and neonatal death (average RR 0.85, 95% CI 0.43 to 1.71; 10 studies, 14,718 participants; very low‐certainty evidence).

Secondary outcomes

When compared to other models of care, midwife continuity of care models likely reduce instrumental vaginal birth (forceps/vacuum) from 14% to 13% (average RR 0.89, 95% CI 0.83 to 0.96; 14 studies, 17,769 participants; moderate‐certainty evidence), and may reduceepisiotomy 23% to 19% (average RR 0.83, 95% CI 0.77 to 0.91; 15 studies, 17,839 participants; low‐certainty evidence).

When compared to other models of care, midwife continuity of care models likelyresult in little to no difference in postpartum haemorrhage (average RR 0.92, 95% CI 0.82 to 1.03; 11 studies, 14,407 participants; moderate‐certainty evidence) and admission to special care nursery/neonatal intensive care unit (average RR 0.89, 95% CI 0.77 to 1.03; 13 studies, 16,260 participants; moderate‐certainty evidence). There may be little or no difference in induction of labour (average RR 0.92, 95% CI 0.85 to 1.00; 14 studies, 17,666 participants; low‐certainty evidence), breastfeeding initiation (average RR 1.06, 95% CI 1.00 to 1.12; 8 studies, 8575 participants; low‐certainty evidence), and birth weight less than 2500 g (average RR 0.92, 95% CI 0.79 to 1.08; 9 studies, 12,420 participants; low‐certainty evidence).

We are very uncertain about the effect of midwife continuity of care models compared to other models of care on third or fourth‐degree tear (average RR 1.10, 95% CI 0.81 to 1.49; 7 studies, 9437 participants; very low‐certainty evidence), maternal readmission within 28 days (average RR 1.52, 95% CI 0.78 to 2.96; 1 study, 1195 participants; very low‐certainty evidence), attendance at birth by a known midwife (average RR 9.13, 95% CI 5.87 to 14.21; 11 studies, 9273 participants; very low‐certainty evidence), Apgar score less than or equal to seven at five minutes (average RR 0.95, 95% CI 0.72 to 1.24; 13 studies, 12,806 participants; very low‐certainty evidence) and fetal loss before 24 weeks gestation (average RR 0.82, 95% CI 0.67 to 1.01; 12 studies, 15,913 participants; very low‐certainty evidence). No maternal deaths were reported across three studies.

Although the observed risk of adverse events was similar between midwifery continuity of care models and other models, our confidence in the findings was limited. Our confidence in the findings was lowered by possible risks of bias, inconsistency, and imprecision of some estimates.

There were no available data for the outcomes: maternal health status, neonatal readmission within 28 days, infant health status, and birth weight of 4000 g or more.

Maternal experiences and cost implications are described narratively. Women receiving care from midwife continuity of care models, as opposed to other care models, generally reported more positive experiences during pregnancy, labour, and postpartum. Cost savings were noted in the antenatal and intrapartum periods in midwife continuity of care models.

Authors' conclusions

Women receiving midwife continuity of care models were less likely to experience a caesarean section and instrumental birth, and may be less likely to experience episiotomy. They were more likely to experience spontaneous vaginal birth and report a positive experience. The certainty of some findings varies due to possible risks of bias, inconsistencies, and imprecision of some estimates.

Future research should focus on the impact on women with social risk factors, and those at higher risk of complications, and implementation and scaling up of midwife continuity of care models, with emphasis on low‐ and middle‐income countries.

Plain language summary

Are midwife continuity of care models versus other models of care for childbearing women better for women and their babies?

Key messages

Women or their babies who received midwife continuity of care models were less likely to experience a caesarean section or instrumental birth with forceps or a ventouse suction cup, and may be less likely to experience an episiotomy (a cut made by a healthcare professional into the perineum and vaginal wall). They were more likely to experience spontaneous vaginal birth.

Women who experienced midwife continuity of care models reported more positive experiences during pregnancy, labour, and postpartum. Additionally, there were cost savings in the antenatal (care during pregnancy) and intrapartum (care during labour and birth) period.

Further evidence may change our results, and future research should focus on the impact on women with social risk factors, and those with medical complications, and understanding the implementation and scaling up of midwife continuity of care models, with emphasis on low‐ and middle‐income countries.

What are midwife continuity of care models?

Midwife continuity of care models provide care from the same midwife or team of midwives during pregnancy, birth, and the early parenting period in collaboration with obstetric and specialist teams when required.

What did we want to find out?

We wanted to find out how outcomes differed for women or their babies who received a midwife continuity of care model compared to other models of care.

Our main outcomes were: spontaneous vaginal birth, caesarean section, regional anaesthesia (spinal or epidural block to numb the lower part of the body), intact perineum (the area between the anus and the vulva), fetal loss after 24 weeks gestation, preterm birth, and neonatal death.

We also looked at a range of other outcomes, including women’s experience and cost.

What did we do?

We searched for studies that compared midwife continuity of care models with other models of care for pregnant women. We compared and summarised the results of the studies and rated our confidence in the evidence based on factors such as study methods and size.

What did we find?

We found 17 studies involving 18,533 women in Australia, Canada, China, Ireland, and the United Kingdom.

Many of these studies largely focused on women with a lower risk of complications at the start of pregnancy, or those drawn from a specific geographical location. Midwives continued to provide midwifery care in collaboration with specialist and obstetric teams if women developed complications in pregnancy, birth, and postpartum.

Our main results

Women or their babies who received midwife continuity of care models compared to those receiving other models of care were less likely to experience a caesarean section or instrumental vaginal delivery, and may be less likely to experience an episiotomy. They were more likely to experience a spontaneous vaginal birth.

Midwife continuity care models probably make little or no difference to the likelihood of having an intact perineum, and may have little or no impact on the likelihood of preterm birth.

We are uncertain about the effect of midwife continuity of care models on regional anaesthesia, fetal loss after 24 weeks' gestation, and neonatal death.

Women who experienced care from midwife continuity of care models reported more positive experiences during pregnancy, labour, and postpartum. Additionally, there were cost savings in the antenatal and intrapartum period.

What are the limitations of the evidence?

Our confidence in these findings varies and further evidence may change our results. For instance, it is not always clear if the people assessing the outcomes knew which type of care the women received. The evidence for fetal loss after 24 weeks' gestation and neonatal death is based on a very small number of cases and there are not enough studies to be certain about some results. We lack data on important aspects like maternal health status after birth, neonatal readmissions, or infant health status.

Few studies included a specific focus on women at high risk of complications, and none focused on women from disadvantaged backgrounds, indicating a need for future research in these areas. This highlights the need for more comprehensive and diverse studies to strengthen our understanding and confidence in these findings, particularly in varied populations and across different healthcare settings.

Future research should focus on the impact on women with social risk factors, and those with medical complications, and understanding the implementation and scaling up of midwife continuity of care models, with emphasis on low‐ and middle‐income countries.

How up‐to‐date is this evidence?

This is an update of our previous review. We included evidence up to 17 August 2022.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings 1. Summary of findings table ‐ Midwife continuity of care models compared to other models of care for childbearing women and their infants (all) (critical outcomes).

| Midwife continuity of care models compared to other models of care for childbearing women and their infants (all) (critical outcomes) | ||||||

| Patient or population: childbearing women and their infants (all) (critical outcomes) Setting: hospital and community‐based environments where midwife continuity of care and other care models are implemented for childbearing women and their infants Intervention: midwife continuity of care models Comparison: other models of care | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with other models of care | Risk with midwife continuity of care models | |||||

| Spontaneous vaginal birth (as defined by trial authors) assessed with: medical records (at the time of birth) | 663 per 1000 | 696 per 1000 (683 to 709) | RR 1.05 (1.03 to 1.07) | 17864 (15 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderatea | |

| Caesarean birth assessed with: medical records (at the time of birth) | 161 per 1000 | 147 per 1000 (136 to 160) | RR 0.91 (0.84 to 0.99) | 18037 (16 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderateb | |

| Regional analgesia (epidural/spinal) assessed with: medical records (during labour and delivery) | 285 per 1000 | 242 per 1000 (225 to 262) | RR 0.85 (0.79 to 0.92) | 17754 (15 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowc,d,e | |

| Intact perineum assessed with: clinical examination (immediately post‐delivery) | 291 per 1000 | 306 per 1000 (285 to 326) | RR 1.05 (0.98 to 1.12) | 14268 (12 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderatef | |

| Fetal loss at or after 24 weeks gestation assessed with: medical records (from 24 weeks gestation to birth) | 3 per 1000 | 4 per 1000 (3 to 7) | RR 1.24 (0.73 to 2.13) | 16122 (12 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowg,h | |

| Preterm birth (< 37 weeks) assessed with: clinical records (gestational age at birth) (at the time of birth) | 59 per 1000 | 56 per 1000 (46 to 68) | RR 0.95 (0.78 to 1.16) | 13850 (10 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowi,j | |

| Neonatal death (baby born alive at any gestation and dies within 28 days) assessed with: medical records (within 28 days post‐birth) | 3 per 1000 | 2 per 1000 (1 to 5) | RR 0.85 (0.43 to 1.71) | 14718 (10 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowk,l | |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; RR: risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

| See interactive version of this table: https://gdt.gradepro.org/presentations/#/isof/isof_question_revman_web_440632394977539792. | ||||||

a For selection bias in random sequence generation, most studies (11 of 15) were low risk, none were high, and 4 were unclear. Similarly, for allocation concealment, most (11) were low risk, 1 was high, and 3 were unclear. Performance bias was judged to be low risk given the objectivity of the outcome. Detection bias was mostly unclear (10 of 15), with 2 low and 3 high. Both attrition and reporting bias showed that most studies (12 of 15) were low risk, with 1 high and 2 unclear. For other bias, the majority (14 of 15) were low risk, with none high and 1 unclear. Downgraded by 1 level. b For selection bias in random sequence generation, most studies (12 of 16) were low risk, none were high, and 4 were unclear. In allocation concealment, most (12) were low risk, 1 was high, and 3 were unclear. Performance bias was judged to be low risk given the objectivity of the outcome. Detection bias was mostly unclear (11 of 16), with 2 low and 3 high. Attrition bias showed that most studies (12 of 16) were low risk, with 2 high and 2 unclear. Reporting bias had the majority (13 of 16) as low risk, 1 high, and 2 unclear. For other bias, nearly all (15 of 16) were low risk, with none high and 1 unclear. Downgraded by 1 level. c Statistical tests of heterogeneity suggest moderate inconsistency (I2 = 51%, Chi2 P = 0.01). However, point estimates across studies appear relatively consistent and there is relatively good overlap of confidence intervals. Downgraded by 1 level. d Egger's test results indicate a statistically significant publication bias with a negative slope of −1.740 and a 2‐tailed P value of 0.026. The negative slope suggests that smaller studies are more likely to show fewer women in the experimental group receiving regional analgesia compared to larger studies. Downgraded by 1 level. e For selection bias in random sequence generation, most studies (11 of 15) were low risk, none were high, and 4 were unclear. In allocation concealment, most (11) were low risk, 1 was high, and 3 were unclear. Performance bias was judged to be low risk given the objectivity of the outcome. Detection bias was mainly unclear (10 of 15), with 2 low and 3 high. In attrition bias, most studies (11 of 15) were low risk, 2 were high, and 2 were unclear. Reporting bias had the majority (13 of 15) as low risk, none high, and 2 unclear. For other bias, nearly all (14 of 15) were low risk, with none high and 1 unclear. Downgraded by 1 level. f For selection bias for both random sequence generation and allocation concealment, most studies (8 of 12) were low risk, with 1 high and 3‐4 unclear. Performance bias was judged to be low risk given the objectivity of the outcome. Detection bias was mainly unclear (9 of 12), with 1 low and 2 high. Attrition bias had most studies (9 of 12) as low risk, 1 high, and 2 unclear. Reporting bias showed a majority (10 of 12) as low risk, with none high and 2 unclear. For other bias, nearly all studies (11 of 12) were low risk, with none high and 1 unclear. Downgraded by 1 level. g Although the sample size is relatively large, the optimal information size criterion is not met because of a relatively small number of events in this population. We estimate a control event rate of 0.35%. Taking alpha as 0.05 and beta as 0.2, a sample size of > 800K is needed for a 10% relative risk reduction (RRR) and > 200K for a 20% RRR. Downgraded by 2 levels. h For both types of selection bias, random sequence generation and allocation concealment, most studies (9 of 12) were low risk, with none high and 3 unclear. Performance bias was judged to be low risk given the objectivity of the outcome. Detection bias was primarily unclear (7 of 12), with 2 low and 3 high. For attrition bias, the majority (10 of 12) were low risk, with none high and 2 unclear. Reporting bias also had most studies (10 of 12) as low risk, none high, and 2 unclear. For other bias, nearly all (11 of 12) were low risk, with none high and 1 unclear. Downgraded by 1 level. i Statistical tests of heterogeneity suggest moderate inconsistency (I2 = 45%, Chi2 P = 0.06). There is some inconsistency in point estimates across studies. Relatively good overlap of confidence intervals. Downgraded by 1 level. j For both types of selection bias, the majority of studies (8 of 10) were low risk, with none high and 2 unclear. Performance bias was judged to be low risk given the objectivity of the outcome. Detection bias was mostly unclear (6 of 10), with 2 each in low and high categories. The majority of studies in attrition bias (8 of 10) were low risk, with none high and 2 unclear. Reporting bias had most studies (8 of 10) as low risk, none high, and 2 unclear. For other bias, the majority (9 of 10) were low risk, with none high and 1 unclear. Downgraded by 1 level. k Although the sample size is relatively large, the optimal information size criterion is not met because of a relatively small number of events in this population. We estimate a control event rate of 0.30%. Taking alpha as 0.05 and beta as 0.2, a sample size of > 900K is needed for a 10% relative risk reduction (RRR) and > 230K for a 20% RRR. Downgraded by 2 levels. l For both types of selection bias, most studies (8 of 10) were low risk, with none high and 2 unclear. Performance bias was judged to be low risk given the objectivity of the outcome. Detection bias was fairly evenly distributed, with 2 low, 3 high, and 5 unclear. In attrition bias and reporting bias, most studies (8 of 10) were low risk, with none high and 2 unclear. For other bias, the majority (9 of 10) were low risk, with none high and 1 unclear. Downgraded by 1 level.

Summary of findings 2. Summary of findings table ‐ Midwife continuity models compared to other models of care for childbearing women and their infants (all) (important/secondary outcomes).

| Midwife continuity models compared to other models of care for childbearing women and their infants (all) (important/secondary outcomes) | ||||||

| Patient or population: childbearing women and their infants (all) (important/secondary outcomes) Setting: hospital and community‐based environments where midwife continuity of care and other care models are implemented for childbearing women and their infants Intervention: midwife continuity models Comparison: other models of care | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with other models of care | Risk with midwife continuity models | |||||

| Healthy mother assessed with: composite of various health metrics (see methods) (timing varies) | Not pooled | Not pooled | Not pooled | (0 studies) | ‐ | |

| Maternal death assessed with: medical records (while pregnant or within 42 days of the end of pregnancy) | Not pooled | Not pooled | Not pooled | 4282 (3 studies) | ‐ | No deaths were reported across the three studies |

| Induction of labour assessed with: medical records (at the time of labour initiation) | 223 per 1000 | 205 per 1000 (189 to 223) | RR 0.92 (0.85 to 1.00) | 17666 (14 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowa,b | |

| Instrumental vaginal birth (forceps/vacuum) assessed with: medical records (at the time of birth) | 144 per 1000 | 128 per 1000 (119 to 138) | RR 0.89 (0.83 to 0.96) | 17769 (14 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderatea | |

| Episiotomy assessed with: medical records (at the time of birth) | 225 per 1000 | 187 per 1000 (174 to 205) | RR 0.83 (0.77 to 0.91) | 17839 (15 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowc,d | |

| Third or fourth degree tear assessed with: medical records (at the time of birth) | 17 per 1000 | 19 per 1000 (14 to 26) | RR 1.10 (0.81 to 1.49) | 9437 (7 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowe,f | |

| Postpartum haemorrhage (as defined by trial authors) assessed with: as defined by trial authors (medical records) (typically within 24 hours of birth) | 85 per 1000 | 78 per 1000 (70 to 88) | RR 0.92 (0.82 to 1.03) | 14407 (11 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderateg | |

| Breastfeeding initiation assessed with: self‐report or medical records (immediately post‐delivery to first few days postpartum) | 692 per 1000 | 733 per 1000 (692 to 775) | RR 1.06 (1.00 to 1.12) | 8575 (8 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowh,i | |

| Maternal readmission within 28 days assessed with: medical records (within 28 days postpartum) | 23 per 1000 | 35 per 1000 (18 to 69) | RR 1.52 (0.78 to 2.96) | 1195 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowj,k | |

| Neonatal readmission within 28 days assessed with: medical records (within 28 days post birth) | Not pooled | Not pooled | Not pooled | (0 studies) | ‐ | |

| Attendance at birth by known midwife assessed with: self‐report or medical records (at the time of birth) | 96 per 1000 | 878 per 1000 (565 to 1000) | RR 9.13 (5.87 to 14.21) | 9273 (11 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowl,m,n | |

| Healthy baby assessed with: composite of various health metrics (see methods) (timing varies) | Not pooled | Not pooled | Not pooled | (0 studies) | ‐ | |

| Birth weight less than 2500 g assessed with: weighing at birth (at the time of birth) | 52 per 1000 | 47 per 1000 (41 to 56) | RR 0.92 (0.79 to 1.08) | 12420 (8 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowo,p | |

| Birth weight equal to or more than 4000 g assessed with: weighing at birth (at the time of birth) | Not pooled | Not pooled | Not pooled | (0 studies) | ‐ | |

| Apgar score less than or equal to 7 at 5 minutes assessed with: medical records (at 5 minutes post‐birth) | 26 per 1000 | 25 per 1000 (19 to 32) | RR 0.95 (0.72 to 1.24) | 12806 (13 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowq,r | |

| Admission to special care nursery/neonatal intensive care unit assessed with: medical records (from birth to discharge from the unit) | 90 per 1000 | 80 per 1000 (69 to 92) | RR 0.89 (0.77 to 1.03) | 16260 (13 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderates | |

| Fetal loss before 24 weeks gestation assessed with: medical records (from conception to 24 weeks gestation) | 27 per 1000 | 22 per 1000 (18 to 27) | RR 0.82 (0.67 to 1.01) | 15913 (12 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowt,u | |

| Maternal experience assessed with: surveys or interviews (typically postpartum period) | Not pooled | Not pooled | Not pooled | (16 RCTs) | ‐ | Women receiving care from midwife continuity of care models, as opposed to other care models, generally reported more positive experiences during pregnancy, labour, and postpartum (16 studies, 17,028 participants). |

| Cost assessed with: cost data (from start of care to a defined postpartum period) | Not pooled | Not pooled | Not pooled | (7 RCTs) | ‐ | Cost savings were noted in antenatal and intrapartum periods in midwife continuity of care models. 7 studies, 8244 participants. |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; RR: risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

| See interactive version of this table: https://gdt.gradepro.org/presentations/#/isof/isof_question_revman_web_444754536843053174. | ||||||

a For selection bias, random sequence generation and allocation concealment, most studies (10 of 14) were low risk, with 1 high and 3‐4 unclear. Performance bias was judged to be low risk given the objectivity of the outcome. Detection bias was mostly unclear (9 of 14), with 2 low and 3 high. For attrition bias, the majority (11 of 14) were low risk, 1 was high, and 2 were unclear. Reporting bias had most studies (12 of 14) as low risk, none high, and 2 unclear. For other bias, nearly all (13 of 14) were low risk, with none high and 1 unclear. Downgraded by 1 level. b Statistical tests of heterogeneity suggest moderate inconsistency (I2 = 41%, Chi2 P = 0.05). There is some inconsistency in point estimates across studies. There is relatively good overlap of confidence intervals. Downgraded by 1 level. c For selection bias, random sequence generation and allocation concealment, most studies (11 of 15) were low risk, with 1 high and 3‐4 unclear. Performance bias was judged to be low risk given the objectivity of the outcome. Detection bias was mainly unclear (10 of 15), with 2 low and 3 high. For attrition bias, most studies (11 of 15) were low risk, 2 were high, and 2 were unclear. Reporting bias had the majority (13 of 15) as low risk, none high, and 2 unclear. For other bias, nearly all (14 of 15) were low risk, with none high and 1 unclear. Downgraded by 1 level. d Statistical tests of heterogeneity suggest moderate inconsistency (I2 = 44%, Chi2 P = 0.04). There is some inconsistency in point estimates across studies. There is relatively good overlap of confidence intervals, but some studies do not overlap fully. Downgraded by 1 level. e For both types of selection bias, the majority of studies were low risk (4‐5 out of 7), with none high and 2‐3 unclear. Performance bias was judged to be low risk given the objectivity of the outcome. Detection bias was mainly unclear (4 of 7), with 2 low and 1 high. In attrition bias, reporting bias, and other bias, most studies (6 of 7) were low risk, with none high and 1 unclear. Downgraded by 1 level. f The optimal information size criterion is not met because of a relatively small number of events in this population. We estimate a control event rate of 1.7%. Taking alpha as 0.05 and beta as 0.2, a sample size of > 53K is needed for a 20% RRR. Downgraded by 2 levels. g For selection bias for random sequence generation and allocation concealment, most studies (8‐9 of 11) were low risk, with none high and 2‐3 unclear. Performance bias was judged to be low risk given the objectivity of the outcome. Detection bias was mostly unclear (7 of 11), with 2 each in low and high categories. For attrition bias and other bias, the majority (10 of 11) were low risk, with none high and 1 unclear. Reporting bias had most studies (9 of 11) as low risk, none high, and 2 unclear. Downgraded by 1 level. h For both types of selection bias, the majority of studies (5‐6 out of 8) were low risk, with none high and 2‐3 unclear. Performance bias was judged to be low risk given objectivity of outcome. Detection bias was fairly evenly distributed, with 2 low, 3 high, and 3 unclear. For attrition bias and other bias, most studies (7 of 8) were low risk, with none high and 1 unclear. Reporting bias had a majority (6 of 8) as low risk, none high, and 2 unclear. In other bias nearly all were low risk (7 of 8) with none high and 1 unclear. Downgraded by 1 level. i Statistical tests of heterogeneity suggest considerable heterogeneity. Heterogeneity: Tau² = 0.00; Chi² = 53.93, df = 7 (P < 0.00001); I² = 87%. There is consistency though in the direction of point estimates. Downgraded by 1 level. j One study at low risk of selection, attrition, performance, reporting, and other bias. High risk for detection bias. Downgraded by 1 level. k The optimal information size criterion is not met. We estimate a control event rate of 2.3%. Taking alpha as 0.05 and beta as 0.2, a sample size of approx. 30K is needed for a 20% RRR. Downgraded by 2 levels. l For selection bias random sequence generation and allocation concealment, most studies (7‐8 of 11) were low risk, with 1 high and 3 unclear. Performance bias was judged to be low risk given the objectivity of the outcome. Detection bias was mainly unclear (6 of 11), with 2 low and 3 high. For attrition bias, most studies (8 of 11) were low risk, 2 were high, and 1 was unclear. Reporting bias and other bias had a majority (10 of 11) as low risk, none high, and 1 unclear. Downgraded by 1 level. m Statistical tests of heterogeneity suggest considerable heterogeneity. Heterogeneity: Tau² = 0.45; Chi² = 190.11, df = 10 (P < 0.00001); I² = 95%. There is consistency though in the direction of point estimates. Downgraded by 1 level n The Egger's regression‐based test indicates significant publication bias in the meta‐analysis on attendance at birth by a known midwife, with a significant intercept (P = 0.048) and a strong correlation between effect size and its standard error (P = 0.002), suggesting that smaller studies with less favourable outcomes are likely missing from the analysis. Downgraded by 1 level. o For both types of selection bias, the majority of studies (6‐7 out of 8) were low risk, with none high and 1‐2 unclear. Performance bias was judged to be low risk given the objectivity of the outcome. Detection bias was fairly evenly distributed, with 2 low, 2 high, and 4 unclear. For attrition bias and reporting bias, most studies (6 of 8) were low risk, with none high and 2 unclear. For other bias, the majority (7 of 8) were low risk, with none high and 1 unclear. Downgraded by 1 level. p The optimal information size criterion is not met. We estimate a control event rate of 5.2%. Taking alpha as 0.05 and beta as 0.2, a sample size of approx. 14K is needed for a 20% RRR. Downgraded by 1 level. q For both types of selection bias, most studies (10 of 13) were low risk, with none high and 3 unclear. Performance bias was judged to be low risk given the objectivity of the outcome. Detection bias was mainly unclear (8 of 13), with 2 low and 3 high. For attrition bias and other bias, the vast majority (12 of 13) were low risk, with none high and 1 unclear. Reporting bias had most studies (10 of 13) as low risk, 1 high, and 2 unclear. Downgraded by 1 level. r The optimal information size criterion is not met. We estimate a control event rate of 2.6%. Taking alpha as 0.05 and beta as 0.2, a sample size of approx. 29K is needed for a 20% RRR. Downgraded by 2 levels s For both types of selection bias, most studies (10 of 13) were low risk, with none high and 3 unclear. Performance bias was judged to be low risk given the objectivity of the outcome. Detection bias was mainly unclear (8 of 13), with 2 low and 3 high. For attrition bias, reporting bias, and other bias, the majority (11‐12 of 13) were low risk, with none high and 1‐2 unclear. Downgraded by 1 level. t For both types of selection bias, most studies (10 of 12) were low risk, with none high and 2 unclear. Performance bias was judged to be low risk given the objectivity of the outcome. Detection bias was mainly unclear (7 of 12), with 2 low and 3 high. For attrition bias, reporting bias, and other bias, the majority (10‐11 of 12) were low risk, with none high and 1‐2 unclear. Downgraded by 1 level. u The optimal information size criterion is not met. We estimate a control event rate of 2.6%. Taking alpha as 0.05 and beta as 0.2, a sample size of approx. 26K to 27K is needed for a 20% RRR. Downgraded by 2 levels.

Background

The maternity care received by pregnant women, including how it is organised, who it is delivered by, and its quality and content, varies widely globally (De Vries 2001). Whether in high‐, middle‐, or low‐income countries, appropriate access to quality maternity care during pregnancy improves maternal and infant mortality and morbidity rates, promotes healthy behaviours, and addresses emotional and social issues (Koblinsky 2016; Victora 2016; World Health Organization 2016; World Health Organization 2018b; World Health Organization 2022). Evidence has shown that high‐quality care from a midwifery workforce is crucial to achieving international goals and targets in reproductive, maternal, newborn, and child health improvements (Nove 2021; Renfrew 2014; Renfrew 2021). In many parts of the world, midwives are the primary care providers for childbearing women (ten Hoope‐Bender 2014), however access to midwifery care in many low‐ and middle‐income countries, and in some high‐income countries, such as the USA, is markedly lower than in other high‐income countries, with midwives representing a small percentage of healthcare professionals (Bradford 2022; Lowe 2020; McFadden 2020; UNFPA 2021).

The World Health Organization recommends midwife continuity of care models, in which a known midwife licensed and educated to international standards (such as International Confederation of Midwives (ICM) global standards) (ICM 2017), or a small group of known midwives, supports a woman throughout the antenatal, intrapartum, and postnatal continuum, in settings with well‐functioning midwifery programmes (World Health Organization 2016; World Health Organization 2018b). In addition, there is increasing evidence that such models can mitigate inequity, social disadvantage, and structural determinants of poor maternal and newborn health outcomes in a range of populations and settings (Hadebe 2021; Homer 2017; Khan 2023; Kildea 2021; Rayment‐Jones 2023). However, there is debate about the clinical and cost‐effectiveness of these models (Ryan 2013), and how models are organised, implemented sustainably (Homer 2019), and evaluated (Bradford 2022).

Description of the condition

The concept of continuity of care more widely is rooted in primary care (Saultz 2003; Saultz 2004). It involves care over time by the same care provider/s to encompass informational, management, and relational continuity to improve personalised integrated care (Freeman 2007; World Health Organization 2018a). As defined by Haggerty 2003, informational continuity concerns the timely availability of relevant information; management continuity involves communicating facts and judgements across the team, institutional and professional boundaries, and between professionals and patients; and relationship continuity means an ongoing therapeutic relationship between the service user and one or more health professionals.

There is evidence that continuity of care between primary care physicians and their patients is associated with better patient outcomes, including diagnostic accuracy (Starfield 2009), improved patient satisfaction (Paddison 2015; Saultz 2005), fewer emergency department visits (Nyweide 2017), fewer hospital admissions (Barker 2017; Pourat 2015; Sandvik 2021), better care co‐ordination (O’Malley 2009), reduced mortality (Baker 2020; Pereira Gray 2018), lower healthcare costs, and lower or more appropriate use of services (Bazemore 2023; Sandvik 2021). Greater continuity of care is also independently associated with lower hospital utilisation for seniors with multiple chronic medical conditions in an integrated delivery system with high informational continuity (Bayliss 2015).

Midwife continuity of care models

Midwife continuity of care models aim to provide care in either community or hospital settings, usually to women with uncomplicated or low‐risk pregnancies for whom the midwife will be the lead professional. In some models, midwives provide continuity of midwife care to all women with social risk factors/living in deprivation, or from a defined geographical location, and continue to provide continuity of midwife care to women who experience complications, in partnership with obstetricians and other professionals. In other models, midwives may provide continuity of midwife care to women with medical or obstetric risk factors as part of a wider team. Midwife continuity of care models must include the provision of maternity care by one or a small team of midwives during the antepartum and intrapartum periods, and some models may extend to the postnatal period in the community in some settings.

Within midwife continuity of care models, women receive dedicated support from the same midwife or team of midwives as appropriate (NHSE 2021). Care may be provided in consultation and collaboration with other health and social care providers during pregnancy, birth, and the postpartum period. Around the world, midwife continuity of care has been implemented in different contexts with variation in the lead professional and degree of autonomous midwifery practice, the composition of the multidisciplinary team, and the target population. However, in all models, the aim is for women to develop relationships with their midwives throughout their pregnancy, birth, and the postnatal period, where offered in the health system. The midwife continuity of care model is based on the holistic premise that pregnancy, birth, and becoming a parent are transformative life events and includes: continuity of care; monitoring the physical, psychological, spiritual and social wellbeing of the woman and family throughout the childbearing cycle; providing the woman with individualised education, counselling and antenatal care; attendance during labour, birth and the immediate postpartum period by a known midwife; ongoing support during the postnatal period; minimising unnecessary technological interventions; and identifying, referring, and co‐ordinating care for women who require obstetric or other specialist attention.

Some midwife continuity of care models provide continuity of care to a defined group of women through a team of midwives sharing a caseload, often called 'team' midwifery. Thus, a woman will receive her care from a number of midwives in the team, the size of which can vary. Other models, often termed 'caseload midwifery', aim to offer greater relationship continuity by ensuring that childbearing women receive their ante‐, intra‐, and postnatal care from one midwife or their practice partner (Homer 2019; McCourt 2006).

Other models of care

Other models of care include:

Obstetrician‐provided care. Where obstetricians are the primary care provider for many childbearing women, an obstetrician (not necessarily the one who provides antenatal care) is present for the birth, and nurses (usually) provide intrapartum and postnatal care.

Family doctor‐provided care, with referral to specialist obstetric care as needed. Obstetric nurses or midwives provide intrapartum and immediate postnatal care, but not at a decision‐making level or throughout the entire care episode, and a medical doctor is present for the birth.

Shared models of care, where responsibility for the organisation and delivery of care is shared between different health professionals throughout the initial booking to the postnatal period. These models are similar in that they do not aim to provide midwife continuity of care. Other models of care must include the provision of maternity care during the antepartum and intrapartum periods, and some models may extend to the postnatal period in some settings.

How the intervention might work

The holistic concept of relational continuity refers to a continuous process of pregnancy, birth, and postnatal care and includes a "coordinated and smooth progression of care from the patient’s point of view" (Dahlberg 2013; Haggerty 2003), rather than isolated events. Continuity contributes to patient perceptions of having a trusted care provider who knows their social and medical history and harnesses an expectation that a known provider will care for them in the future, lessening stress and anxiety (Haggerty 2003; Kildea 2018; Parchman 2004; Rayment‐Jones 2022). This longitudinal aspect develops a trusting relationship between women and their midwives. It enables midwives to work to their full scope of practice across women’s care journeys, improving their ability to identify women’s individual needs and providing a safety net (Cook 2000; McInnes 2020; Rayment‐Jones 2020).

Relational continuity over time has been found to have a more significant effect on user experience and outcome in high‐income countries (Dahlberg 2013; Fernandez Turienzo 2016; Homer 2017; Kelly 2014; Rayment‐Jones 2015; Rayment‐Jones 2021; Saultz 2005). It has been argued that neither management nor informational continuity can compensate for the lack of an ongoing relationship over time (Guthrie 2008; Parchman 2004; World Health Organization 2018a).

Suggested mechanisms of effect in maternity and primary care literature include care providers taking greater responsibility, improved trust, confidence in the care provider, feeling safe to disclose concerns or risk factors, reduced stigma and discrimination, and improved engagement, access, and referral (Fernandez Turienzo 2021; McInnes 2020; Parchman 2004; Rayment‐Jones 2022; Rayment‐Jones 2023; Sidaway‐Lee 2021). Lower rates of interventions could be linked to the greater agency experienced by women and midwives within midwife continuity of care models, and these effects are mediated, in part, by the context of the settings (Walsh 2012). Continuity of care may also lead to enhanced co‐ordination or navigation of care, greater advocacy, timely follow‐up of test results, and greater adherence to treatments and multidisciplinary guidelines (Barker 2018; Fernandez Turienzo 2021; Rayment‐Jones 2020; Sidaway‐Lee 2021). It may also provide more opportunities for social support from multidisciplinary services, families, and the local community, timely care, earlier help‐seeking, opportunities for early prevention, escalation of concerns, and diagnosis of complications to facilitate management and intervention (Fernandez Turienzo 2021; Rayment‐Jones 2015; Sidaway‐Lee 2021). This literature has resulted in more recent interest in continuity of care models for those with multi‐morbidities and disproportionate risk of health inequalities and multiple morbidities (Chau 2021; Engamba 2019). The general literature on continuity notes that a lack of clarity in the definition and measurement of different types of continuity has been one of the limitations of research in this field and that there is a need for better specification between models of care and outcomes (Haggerty 2003; McInnes 2020).

Why it is important to do this review

This is an update of a Cochrane review first published in 2008 and last updated in 2016. The 2016 review is more than five years old, and new studies need to be incorporated. Midwife continuity of care is at the heart of maternal policy in some high‐income countries and is considered important globally by the World Health Organization (WHO). The applicability to low‐ and middle‐income settings is a key issue for local and national stakeholders. It is therefore important to explore whether the effects of midwife continuity of care models are influenced by variation in the model of care, maternal medical and obstetric risk status, social risk factors, and in low‐ to high‐income country settings.

This updated review aims to complement other systematic review work on models of maternity care (Bradford 2022; Homer 2016; Perriman 2018) and contribute to the knowledge base on the effects of midwife continuity of care models. This update includes a focus on how outcomes are influenced by variations in models of care, maternal medical and obstetric risk status, social risk factors, and low‐ to high‐income country settings. The definition of the intervention has changed from ‘midwife‐led continuity models’ to ‘midwife continuity of care models’ to include interventions for women with medical and obstetric risk who may receive collaborative specialist and obstetric‐led care and midwife continuity of care. This change aligns with current policy and recommendations for relational continuity and effective collaborative multidisciplinary networks of care (Carmone 2020; NHSE 2021; World Health Organization 2018a).

Objectives

The primary objective of this review is to compare the effects of midwife continuity of care models with other models of care for childbearing women and their infants. We also explore whether the effects of midwife continuity of care are influenced by: 1) variation in midwifery models of care; 2) obstetric and medical risk factors; 3) social risk factors; 4) country income level.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included randomised trials using individual‐ or cluster‐randomisation methods and quasi‐randomised trials. The latter group refers to trials where allocation may not have been genuinely random, for example when the allocation was alternate or unclear.

Types of participants

Pregnant women from all demographics, regardless of age, ethnicity, socio‐economic status, education, place of residence, or level of deprivation. We also included pregnant women with various risk factors, including medical, obstetric, and social risks, and those receiving care in home, hospital, or community settings. The review also encompasses participants receiving care through either private or public healthcare systems and those residing in low‐ or high‐income countries. All women allocated to a midwife continuity of care model or another model of care were eligible for inclusion.

Types of interventions

Midwife continuity of care models ‐ intervention

For a model to be classified as a midwife continuity of care model, midwifery care is provided by a midwife and/or a small team of midwives throughout the antepartum and intrapartum periods, which may extend to the postpartum period in some settings.

In all models, care is provided in consultation with medical staff in pregnancy, birth, and the postpartum period as appropriate.

Midwife continuity of care models aim to provide care in either community or hospital settings. Normally, midwives are the lead professionals for healthy women with uncomplicated pregnancies. In some models, midwives provide continuity of midwifery care to all women with specialised needs, such as social risk factors, or from a defined geographical location, acting as lead professionals for women whose pregnancy and birth is uncomplicated and continuing to provide continuity of midwife care to women who experience medical and obstetric complications in partnership with other professionals. In some models, midwives may provide continuity of midwife care to women with obstetric risk factors as part of a wider team.

Some midwife continuity models provide continuity to a defined group of women through a team of midwives, often called 'team' midwifery. Thus, a woman will receive her midwifery care from a few midwives in the team, the size of which can vary (often between four and eight midwives). Other models, often termed 'caseload midwifery', aim to offer greater relationship continuity by ensuring that childbearing women receive their ante‐, intra‐, and postnatal care from one midwife or their practice partner backed up by a wider team or group practice.

Other models of care ‐ comparison

These models of care include:

Obstetrician‐provided care, where obstetricians are the primary antenatal care providers for childbearing women. An obstetrician (not necessarily the one who provides antenatal care) is present for the birth, and nurses offer intrapartum and postnatal care.

Family doctor‐provided care, with referral to specialist obstetric care as needed. Obstetric nurses or midwives provide intrapartum and immediate postnatal care but not at a decision‐making level or throughout the entire care episode, and a medical doctor is present for the birth.

Shared models of care, where health professionals share responsibility for the organisation and delivery of care throughout the initial booking to the postnatal period. Other models of care must include the provision of maternity care during the antepartum and intrapartum periods, and some models may extend to the postnatal period in some settings.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Spontaneous vaginal birth (defined by trial authors)

Caesarean birth

Regional analgesia (epidural/spinal)

Intact perineum

Fetal loss at or after 24 weeks gestation

Preterm birth (< 37 weeks)

Neonatal death (baby born alive at any gestation and dies within 28 days)

Secondary outcomes

Healthy mother (defined as one who is alive at 28 days postpartum, without a Caesarean birth, postpartum haemorrhage (as defined by trial authors), third or fourth‐degree tear, or readmission within 28 days)

Maternal death

Induction of labour

Instrumental vaginal birth (forceps/vacuum)

Episiotomy

Third‐ or fourth‐degree tear

Postpartum haemorrhage (defined by trial authors)

Breastfeeding initiation (defined by trial authors)

Maternal readmission within 28 days

Maternal experience (defined by trial authors)

Attendance at birth by a known midwife who provided antenatal care

Cost (as defined by trial authors)

Healthy baby (defined as one born after 37 + 0 weeks gestation and alive at 28 days and without readmission within 28 days)

Birth weight less than 2500 g

Birth weight equal to or more than 4000 g

Apgar score less than or equal to seven at five minutes

Admission to special care nursery/neonatal intensive care unit

Fetal loss before 24 weeks gestation

Search methods for identification of studies

The following methods sections of this review are based on a standard template used by Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth.

Electronic searches

For this update, in collaboration with the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Information Specialist, a search was conducted on 17 August 2022 of the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Trials Register, which contains over 34,000 reports of controlled trials related to pregnancy and childbirth and represents over 30 years of searching.

Full details of the current search methods used to populate the Register, including search strategies for CENTRAL, MEDLINE, Embase, and CINAHL, the list of handsearched journals and conference proceedings, and the list of journals reviewed via the current awareness service, can be found in Appendix 1.

The Information Specialist maintains the Trials Register, which contains trials identified through monthly searches of CENTRAL, weekly searches of MEDLINE and Embase, monthly searches of CINAHL, handsearches of 30 journals and conference proceedings, and weekly current awareness alerts for an additional 44 journals plus monthly BioMed Central email alerts.

Two people screen the search results and review the full text of all relevant trial reports identified through the search activities described above. Based on the intervention described, each trial report is assigned a number corresponding to a specific Pregnancy and Childbirth review topic and added to the Register.

The Information Specialist searches the Register for each review using this topic number for a more specific search set, fully accounted for in the relevant review sections (Included, Excluded, Awaiting Classification, or Ongoing).

Additionally, unpublished, planned, and ongoing trial reports were searched for on ClinicalTrials.gov and the WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) using the search methods detailed in Appendix 2. This search was also conducted on 17 August 2022.

Searching other resources

We searched for further studies in the reference lists of the studies identified.

We did not apply any language or date restrictions.

Data collection and analysis

For methods used in the previous version of this review, see Sandall 2016.

This update was conducted using a standard template from Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth, as outlined in the following methods sections of this review.

Selection of studies

Three review authors (JS, CFT, HRJ) independently assessed for inclusion all potential studies identified as a result of the search strategy. We resolved any disagreement through discussion or, if required, we consulted other review authors (DD, HS, LJ).

We created a study flow diagram to map out the number of records identified, included, excluded, or awaiting classification.

All studies meeting our inclusion criteria were evaluated by three review authors (LJ, CFT, HRJ) against the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Trustworthiness Screening tool (CPC‐TST). This screening tool is a set of predefined criteria to select studies that, based on available information, are deemed sufficiently trustworthy to be included in the analysis. The criteria are:

Research governance

Are any retraction notices or expressions of concern listed on the Retraction Watch Database relating to this study?

Was the study prospectively registered (for those studies published after 2010)? If not, was there a plausible reason?

Did the trial authors provide/share the protocol and/or ethics approval letter when requested?

Did the trial authors communicate with the Cochrane review authors within the agreed timelines?

Did the trial authors provide individual participant data (IPD) upon request? If not, was there a plausible reason?

Baseline characteristics

Is the study free from characteristics of the participants that appear too similar (e.g. distribution of the mean (SD) is excessively narrow or excessively wide, as noted by Carlise 2017).

Feasibility

Is the study free from characteristics that could be implausible? (e.g. large numbers of women with a rare condition (such as severe cholestasis in pregnancy) recruited within 12 months).

Is there a plausible explanation in cases with (close to) zero losses to follow‐up?

Results

Is the study free from results that could be implausible? (e.g. massive risk reduction for primary outcomes with a small sample size)?

Do the numbers randomised to each group suggest that adequate randomisation methods were used (e.g. is the study free from issues such as unexpectedly even numbers of women ‘randomised’ including a mismatch between the numbers and the methods, if the authors say ‘no blocking was used’ but still end up with equal numbers, or if the authors say they used ‘blocks of 4’ but the final numbers differ by 6)?

The review did not include studies assessed as potentially ‘high‐risk’. Where a study was classified as ‘high‐risk’ for one or more of the above criteria, we attempted to contact the study authors to address any possible lack of information/concerns. Where adequate information was not obtained, the study remains ‘awaiting classification’, and the reasons and communications with the author (or lack of) are described in detail.

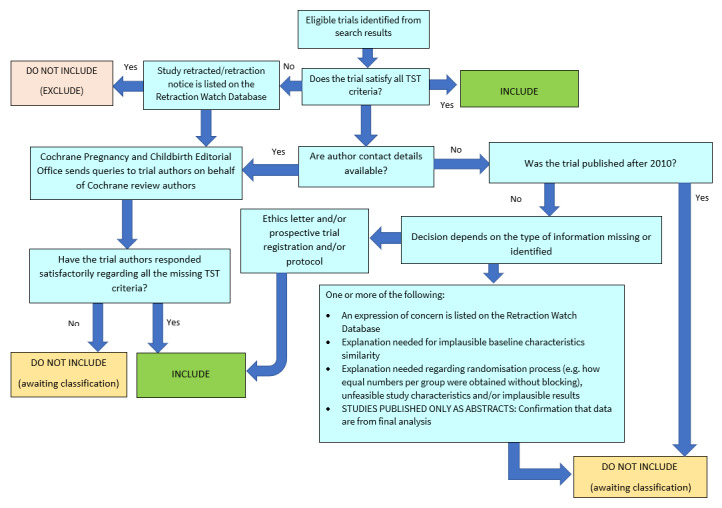

The process is described in its entirety in Figure 1.

1.

Applying the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Trustworthiness Screening Tool

Abstracts

Data from abstracts have only been included if, in addition to the trustworthiness assessment, the study authors have confirmed in writing that the data to be included in the review have come from the final analysis and will not change. Where such information is unavailable/not provided, the study remains ‘awaiting classification’ (as above).

Data extraction and management

We adapted the data extraction template from Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth to extract data. Six review authors (JS, CFT, DD, HS, LJ, HRJ) extracted the data for eligible studies using the agreed form. We resolved discrepancies through discussion or, if required, we consulted the other review authors (AHS, SG, PG). Data were entered into Review Manager Web software (Review Manager Web 2023) and checked for accuracy.

When information regarding any of the above was unclear, we contacted the authors of the original reports to provide further details.

Review author D Devane is a co‐author of Begley 2011, and J Sandall, A Shennan, and C Fernandez Turienzo are co‐authors of Fernandez Turienzo 2020, so they were not involved in the data extraction or risk of bias assessment for the studies on which they were co‐authors.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Six authors in groups of two (JS, CFT, DD, HS, LJ, HRJ) independently assessed the risk of bias for each study using the criteria outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). Any disagreement was resolved by discussion or by involving another assessor.

Random sequence generation (checking for possible selection bias)

For each included study, we described the method used to generate the allocation sequence in sufficient detail to allow an assessment of whether it should produce comparable groups.

We assessed the method as:

low risk of bias (any genuinely random process, e.g. random number table; computer random number generator);

high risk of bias (any non‐random process, e.g. odd or even date of birth; hospital or clinic record number);

unclear risk of bias.

Allocation concealment (checking for possible selection bias)

For each included study, we described the method used to conceal allocation to interventions before assignment. We assessed whether intervention allocation could have been foreseen before, during recruitment, or changed after the assignment.

We assessed the methods as:

low risk of bias (e.g. telephone or central randomisation; consecutively numbered, sealed, opaque envelopes);

high risk of bias (open random allocation; unsealed or non‐opaque envelopes, alternation; date of birth);

unclear risk of bias.

Blinding of participants and personnel (checking for possible performance bias)

For each included study, we described the methods used, if any, to blind study participants and personnel from knowledge of which intervention a participant received. We considered that studies are at low risk of bias if they were blinded or if we judged that the lack of blinding would unlikely affect results. We assessed blinding separately for different outcomes or classes of outcomes.

We assessed the methods as:

low, high, or unclear risk of bias for participants;

low, high, or unclear risk of bias for personnel.

Blinding of outcome assessment (checking for possible detection bias)

For each included study, we described the methods used, if any, to blind outcome assessors from knowledge of which intervention a participant received. We assessed blinding separately for different outcomes or classes of outcomes.

We assessed the methods used to blind outcome assessment as:

low, high, or unclear risk of bias.

Incomplete outcome data (checking for possible attrition bias due to the amount, nature, and handling of incomplete outcome data)

We described the completeness of data for each included study, and for each outcome or class of outcomes, including attrition and exclusions from the analysis. We stated whether attrition and exclusions were reported and the numbers included in the analysis at each stage (compared with the total randomised participants), reasons for attrition or exclusion where reported, and whether missing data were balanced across groups or were related to outcomes. Where sufficient information was reported or could be supplied by the trial authors, we planned to re‐include missing data in the analyses which we undertook.

We assessed the methods as:

low risk of bias (e.g. no missing outcome data; missing outcome data balanced across groups);

high risk of bias (e.g. numbers or reasons for missing data imbalanced across groups; ‘as treated’ analysis done with the substantial departure of intervention received from that assigned at randomisation);

unclear risk of bias.

Selective reporting (checking for reporting bias)

We described how we investigated the possibility of selective outcome reporting bias for each included study and what we found.

We assessed the methods as:

low risk of bias (where it is clear that all of the study’s pre‐specified outcomes and all expected outcomes of interest to the review have been reported);

high risk of bias (where not all the study’s pre‐specified outcomes have been reported; one or more reported primary outcomes were not pre‐specified; outcomes of interest are reported incompletely and so cannot be used; the study fails to include results of a key outcome that would have been expected to have been reported);

unclear risk of bias.

Other bias (checking for bias due to problems not covered above)

For each included study, we described any important concerns we had about other possible sources of bias.

Dichotomous data

For dichotomous data, we presented results as a summary risk ratio with 95% confidence intervals.

Continuous data

We planned to use the mean difference if outcomes were measured similarly between trials. In future updates, as appropriate, we will use the standardised mean difference to combine trials that measure the same outcome but use different methods.

Time‐to‐event data

No outcomes were expected using time‐to‐event data.

Cluster‐randomised trials

In addition to individually randomised trials, we included a cluster‐randomised trial in the analyses (North Stafford 2000). This trial found a negative ICC, so no adjustment was made for clustering. We considered it reasonable to combine the results from cluster‐randomised and individually randomised trials if there was little heterogeneity between the study designs and an interaction between the effect of the intervention and the choice of randomisation unit was considered to be unlikely. We also conducted a sensitivity analysis by excluding North Stafford 2000 from the meta‐analyses to which it contributed data (see Sensitivity analysis).

Other unit of analysis issues

Multiple pregnancies were included, and both infants were included in the denominator.

For any study with more than two intervention groups in a meta‐analysis, we planned to (i) omit groups that were not relevant to the comparison being made or (ii) combine multiple groups that were eligible as the experimental or comparator intervention to create a single pair‐wise comparison.

Dealing with missing data

For included studies, we noted levels of attrition. For all outcomes, we carried out analyses, as far as possible, on an intention‐to‐treat basis, i.e. we attempted to include all participants randomised to each group in the analyses. The denominator for each outcome in each trial was the number randomised minus any participants whose outcomes were known to be missing.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed statistical heterogeneity in each meta‐analysis using the Tau², I², and Chi² statistics. We regarded heterogeneity as substantial if an I² value was greater than 30% and either a Tau² was greater than zero or there was a low P value (less than 0.10) in the Chi² test for heterogeneity. We planned to explore several pre‐specified subgroup analyses (see Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity).

Assessment of reporting biases

Where there were 10 or more studies in the meta‐analysis, we investigated reporting biases using funnel plots. We assessed funnel plot asymmetry visually and using Egger's test with the software Comprehensive Meta‐Analysis.

Data synthesis

We carried out statistical analysis using the Review Manager software (Review Manager Web 2023).

Where clinical heterogeneity was sufficient to expect that the underlying treatment effects differed between trials, or where substantial statistical heterogeneity was detected, we used random‐effects meta‐analysis to produce an overall summary of whether an average treatment effect across trials was considered clinically meaningful. The random‐effects summary was treated as the average of the range of possible treatment effects and we discussed the clinical implications of treatment effects differing between trials. We would not have combined trials if the average treatment effect had been clinically meaningful. The results were presented as the average treatment effect with 95% confidence intervals and the estimates of Tau² and I².

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

Where we identified substantial heterogeneity, we investigated it using subgroup analyses and sensitivity analyses. We considered whether an overall summary was meaningful and, if it was, we used random‐effects analysis to produce it.

We carried out the following subgroup analyses.

Caseload versus team models of midwifery care

Low‐risk versus mixed‐risk status

Women with social risk factors versus all women

Countries with a very high Human Development Index (HDI) > 0.8 versus high, medium, and low HDI

Subgroup analyses were restricted to the primary outcomes, which were:

Spontaneous vaginal birth (as defined by trial authors)

Caesarean birth

Regional analgesia (epidural/spinal)

Intact perineum

Fetal loss at or after 24 weeks gestation

Preterm birth (< 37 weeks)

Neonatal death (baby born alive at any gestation and dies within 28 days)

We assessed subgroup differences by interaction tests available within RevMan (Review Manager Web 2023). We reported the results of subgroup analyses quoting the Chi² statistic and P value, and the interaction test I² value.

Sensitivity analysis

We conducted sensitivity analyses to investigate the impact of the risk of bias on our findings. We repeated the analysis, retaining only the studies at low risk of bias for random sequence generation, allocation concealment, and incomplete outcome data, to evaluate whether this altered the overall results. We also conducted a sensitivity analysis by excluding North Stafford 2000 from the meta‐analyses to which it contributed data (see Sensitivity analysis).

Summary of findings and assessment of the certainty of the evidence

We employed the GRADE (Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation) approach, as delineated in the GRADE Handbook, to assess the certainty of the evidence for all available outcomes in the primary comparisons between midwife continuity of care and all other models of care for childbearing women and their infants. This was undertaken to enable the use of GRADE‐recommended informative statements for communicating the results of systematic reviews, which necessitate a rating of the certainty of evidence. Critical outcomes (spontaneous vaginal birth, caesarean section, regional anaesthesia, intact perineum, fetal loss after 24 weeks gestation, preterm birth, and neonatal death) are presented in Table 1. Outcomes that we deemed to be less important are presented in Table 2.

We utilised the GRADEpro Guideline Development Tool to import data from Review Manager Web (Review Manager Web 2023) to create the summary of findings tables. Using the GRADE approach, we produced a summary of the intervention effect and a measure of certainty for each outcome, using five considerations to assess the certainty of the body of evidence (study limitations, consistency of effect, imprecision, indirectness, and publication bias). The evidence can be downgraded from 'high certainty' by one level for serious (or by two levels for very serious) limitations, depending on assessments for risk of bias, indirectness of evidence, serious inconsistency, imprecision of effect estimates, or potential publication bias. We explain any downgrading decisions in the footnotes in the summary of findings tables.

In this update, we present the results of the review and certainty ratings, focusing on both relative and absolute effects. For estimating the certainty of evidence, we used baseline risks observed in control groups across the included studies and multiplied them by the relative effects. We have applied the GRADE partially contextualised approach for interpreting findings, as suggested in the latest GRADE guidance on imprecision (Zeng 2022). This approach informed our interpretation of the size of the effects for the different outcomes. This was particularly since there are no known minimum clinically important differences (MCIDs) established for our critical outcomes. Our analysis and interpretation are aligned with GRADE's emphasis on absolute effects, particularly in the absence of MCIDs, thereby providing a clearer understanding of the practical significance of the results (Santesso 2020).

Results

Description of studies

This review update includes a total of 17 studies (77 study reports), 42 excluded studies (69 study reports), one study awaiting classification (one study report), and three ongoing studies (three study reports).

Results of the search

For this update, we identified a total of 221 records from electronic databases, and we found 17 potentially relevant studies from other sources. After the removal of duplicates, 218 records remained and we screened out 163 of these for either not being a trial or having a different scope. We assessed a total of 55 full trial reports for eligibility. Ten of these trial reports were found to be additional reports relating to three already included studies (Homer 2001; McLachlan 2012; Tracy 2013). One new trial (seven reports) has been included (Fernandez Turienzo 2020), two trials previously excluded in the last version of the review have now been included (Gu 2013; Marks 2003), and one trial previously included has now been excluded (Allen 2013), making the final number of included studies 17. Twenty‐one new studies (34 study reports) were excluded, with reasons. One study is awaiting further classification (Zhang 2016) (see Characteristics of studies awaiting classification). Three studies are ongoing (Cullinane 2021; Dickerson 2022; Xiaojiao 2020) (see Characteristics of ongoing studies). See Figure 2 for details of the most recent search results.

2.

Screening eligible studies for trustworthiness

We used the trustworthiness screening tool developed by Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth to assess the 17 studies meeting the review's inclusion criteria. These were screened by two review authors, and all assessments were discussed and agreed upon with the review team.

We had no concerns about trustworthiness for four studies and these were included (Begley 2011; Fernandez Turienzo 2020; McLachlan 2012; Tracy 2013). For the remaining studies, there were minor concerns relating to research governance and the results of two studies. In 13 studies, we sought clarification from trial authors on ethics approval and whether a protocol had been developed. None of these studies were prospectively registered, but we were not concerned about this because all but one of these studies were published before 2010, when trial registration was not a requirement.

Research governance

We sought clarification from the trial authors regarding ethics approval and the development of a protocol. In eight studies, although ethics approval was reported in the trial report, we also contacted the trial authors for further clarification and to obtain copies of any relevant paperwork. In two studies, the authors responded that all pertinent paperwork relating to ethics approval was no longer available due to the time‐lapse since the conduct of the study (MacVicar 1993; Turnbull 1996). In another study, the authors responded to confirm that there was no protocol or trial registration but that they had received ethics approval (North Stafford 2000). For Rowley 1995, the authors responded and provided copies of the protocol and ethics approval. For Waldenstrom 2001, the authors responded to confirm that they were almost sure that there had been no protocol before the commencement of the trial due to this not being a requirement of the time, but that ethics approval had been obtained. For Marks 2003, the author said there was no longer any paperwork available, but it went through the local ethics committee. In one study (Biro 2000), we could not get a response and received an email delivery failure. In one study (Gu 2013), we sought clarification from the author regarding the reason for retrospective trial registration and requested copies of both ethics approval and the protocol, which the authors provided. The authors responded that their trial was registered retrospectively because, at that time in China, it was not a requirement to pre‐register the trial. Hence, it was registered retrospectively after notification of this requirement from an international journal. In two studies, the authors responded to our enquiries and confirmed that a protocol was developed for each study and that ethics approval was also obtained (Flint 1989; Harvey 1996). In another study, the authors responded by saying local ethics approval was obtained (Hicks 2003). For Homer 2001, the authors confirmed there was no protocol, but a research proposal was developed prior to the study, and ethics approval was obtained. In the final study, the authors provided a copy of the ethics approval (Kenny 1994).

Results

In two studies, we had minor concerns relating to the domain of the results. In one study, the study flow of participants was not clear (North Stafford 2000). We contacted the trial authors, who clarified the study flow and confirmed no follow‐up loss in their cluster trial (North Stafford 2000). In the second study, the randomisation methods were unclear (Gu 2013). The trial authors responded to our email request to report that a simple randomisation scheme was conducted, using a computer‐generated computer random sequence from 1 to 110. The list of random numbers and group allocation were kept concealed in sealed, opaque envelopes. They also reported that, following informed consent, women were randomly allocated to one of the two groups. The allocation was not revealed until the clerical assistant recorded the woman’s details (Gu 2013).

All 17 eligible studies were assessed at low risk after screening for scientific integrity/trustworthiness.

Included studies

We included 17 studies involving 18,532 randomised women in total (Begley 2011; Biro 2000; Fernandez Turienzo 2020: Flint 1989; Gu 2013; Harvey 1996; Hicks 2003; Homer 2001; Kenny 1994; Marks 2003; MacVicar 1993; McLachlan 2012; North Stafford 2000; Rowley 1995; Tracy 2013; Turnbull 1996; Waldenstrom 2001). See Characteristics of included studies.

Included studies were conducted in Australia, Canada, China, Ireland, and the United Kingdom, with variations in model of care, risk status of participating women, and practice settings. The Zelen method was used in three trials (Flint 1989; Homer 2001; MacVicar 1993), and one trial used cluster‐randomisation (North Stafford 2000).

Five studies offered a caseload model of care (Fernandez Turienzo 2020; McLachlan 2012; North Stafford 2000; Tracy 2013; Turnbull 1996) and 12 studies provided a team model of care (Begley 2011; Biro 2000; Flint 1989; Gu 2013: Harvey 1996; Hicks 2003; Homer 2001; Kenny 1994; Marks 2003; MacVicar 1993; Rowley 1995; Waldenstrom 2001). The composition and modus operandi of the teams varied amongst trials. Levels of continuity (measured by the percentage of women who were attended during birth by a known carer) ranged between 63% and 98% for midwife continuity models of care to between 0.3% and 21% in other models of care.

Ten studies compared a midwife continuity of care model with a shared model of care (Begley 2011; Biro 2000; Fernandez Turienzo 2020: Flint 1989; Hicks 2003; Homer 2001; Kenny 1994; Marks 2003; North Stafford 2000; Rowley 1995), four studies compared a midwife continuity of care model with medical‐led models of care (Gu 2013; Harvey 1996; MacVicar 1993; Turnbull 1996), and three studies compared a midwife continuity of care model with various options of standard care including shared, medical‐led, and shared care (McLachlan 2012; Tracy 2013; Waldenstrom 2001).