Abstract

Introduction:

Cigarette smoke accounts for over 90,000 deaths each year in Italy. Tobacco dependence treatment guidelines suggest adopting an integrated pharmacological-behavioral model of intervention. Cytisine is a partial agonist of nicotinic receptors. Trials conducted to date have demonstrated its good efficacy in promoting smoking cessation. The cytisine scheme of treatment consists of 25 days of treatment. A 40-day regimen, with an escalating dose and an extended duration of the treatment, has been in use in many anti-smoking centers in Italy for several years, but to date there are no reports on the use of cytisine with this scheme.

Methods:

A retrospective, real-life, observational study was conducted between January 2016 and September 2022. The 300 patients who had received at least one dose of study medication were selected. Continuous variables were compared by the Wilcoxon-Mann–Whitney test. Univariate and multivariate logistic regression models were implemented for self-reported seven-day point prevalence for abstinence at three, six and 12 months.

Results:

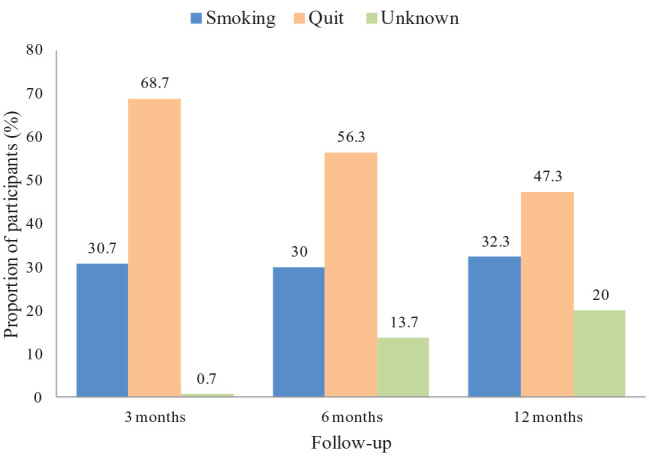

The median age of the patients was 59 years, 57% were women. The median smoking exposure was 33.8 pack-years. Self-reported smoking abstinence at three, six and 12 months was 68.7%, 56.3% and 47.3% respectively. 84% completed the cytisine treatment, 31.3% reported adverse events and in 8.3% these led to dropping out of the treatment.

Conclusion:

Cytisine, administered with a novel therapeutic scheme in the real-life setting of a specialized anti-smoking center, significantly promotes smoking abstinence. However, more studies are needed to assess the tolerability and efficacy of this new regimen.

Keywords: tobacco smoke, nicotine addiction, smoking cessation, anti-smoking center, cytisine, varenicline

Introduction

Cigarette smoke is the most preventable cause of illnesses worldwide and it accounts for over than 90,000 deaths each year in Italy. 1 However, attempts at quitting without any support are affected by high percentage of failures. 2 Guidelines suggest adopting an integrated model of intervention, based on pharmacological help coupled with behavioral support, to address nicotine dependence. 3

The anti-smoking therapies currently approved for clinical use are nicotine replacement therapy (NRT), bupropion and varenicline. 3 For a decade the latter in particular has been considered as the reference treatment in smoking cessation, but has been recently withdrawn from the market for safety reasons. 4

Cytisine appears to increase quitting rates however evidence is limited to few trials (Level of evidence B); 3 it is a natural alkaloid extracted from Cytisus laburnum and it acts as a partial agonist of the α4β2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Cytisine prevents the binding of nicotine to its targets, thereby counteracting the satisfaction from nicotine addiction and compensating the withdrawal symptoms. The mechanism of action of cytisine is therefore similar to that of varenicline, even if the two molecules show differences from a pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic point of view. 5

The drug has been used since 1965 in Eastern Europe as a support for smoking cessation and, starting in 2015, it was introduced in Italy as a galenic (on prescription) pharmaceutical formulation.

The cytisine scheme used so far includes a short route of 25 days (see Online Supplementary Material 1), with an administration schedule consisting of 1.5 mg tablets in a down- titration, from six tablets/day to one tablet/day over the end of treatment. During the first three days, when the maximum dosage is taken, the amount of cigarettes must be reduced to avoid side effects from excess nicotine, and smoking cessation must be achieved by the fifth day of treatment. 3

To date, few clinical trials explored the efficacy and the safety of cytisine, as compared to the approved first-line tobacco cessation treatments.

The drug was initially used by Zatonski et al. in an open, uncontrolled trial where 438 attendees of an anti-smoking center received a routine course of cytisine, with a one-year continuous smoking abstinence of 13.8%. 6

In 2014 Walker et al. tested the drug in a 1:1 open label non-inferiority trial against NRT, plus a low-intensity behavioral support over eight weeks; cytisine turned out to be superior to NRT in terms of continuous smoking abstinence at one month (40% in the cytisine allocation group versus 31% for NRT allocation group). 7

In 2021 Courtney et al. recruited 1452 patients for a randomized open-label clinical trial that aimed to acknowledge the non-inferiority of cytisine against varenicline in terms of continuous smoking abstinence. 8 The enrolled patients received the drugs at the routine dosage (25 days for cytisine versus 84 days for varenicline). In this context cytisine failed to achieve the prespecified outcome of non-inferiority, even if the rates of smoking abstinence were encouraging (11.7% for the cytisine versus 13.3% for the varenicline).

In the same year Walker et al. compared the efficacy of cytisine versus varenicline as a treatment to stop smoking. 9 They allocated 679 patients a 1:1 manner to receive an extended dosage of cytisine up to the twelfth week, in order to match the varenicline duration. In this setting the drug turned out to be at least as effective as the comparator in terms of continuous smoking abstinence (12.1% for cytisine versus 7.9% for varenicline) and it was better tolerated.

Recently, Rigotti et al. 10 confirmed the efficacy and tolerability of cytisine with a 3-group, double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized trial: the study compared two durations of cytisinicline treatment (six or 12 weeks) vs placebo, with follow-up to 24 weeks. For the six-week course of cytisinicline vs placebo, continuous abstinence rates were 25.3% vs 4.4% during weeks 3 to 6 (odds ratio [OR], 8.0 [95% CI, 3.9-16.3]; P < .001) and 8.9% vs 2.6% during weeks 3 to 24 (OR, 3.7 [95% CI, 1.5-10.2]; P = .002). For the 12-week course of cytisinicline vs placebo, continuous abstinence rates were 32.6% vs 7.0% for weeks 9 to 12 (OR, 6.3 [95% CI, 3.7-11.6]; P < .001) and 21.1% vs 4.8% during weeks 9 to 24 (OR, 5.3 [95% CI, 2.8-11.1]; P < .001). 10

In Italy, shortly after its introduction as a galenic formulation, a group of clinicians proposed a modified scheme of cytisine which would allow for greater graduality in reaching the quit day. This scheme has been adopted by many anti-smoking centers in Italy because it is more similar to the other therapies used (bupropion and varenicline) which require a week of drug therapy at a reduced dosage before moving on to the full dosage and quitting smoking. The proposed scheme (Table 1) includes a short induction period (e.g. seven days) and then a longer treatment (until day 40) of cytisine, with a slower daily dose reduction as compared to the standard one. 11

Table 1.

Modified cytisine schedule.

| Day 1 | 2 tab /die | (1 tab every 12 hours) |

|---|---|---|

| Day 2 | 3 tab /die | (1 tab every 6 hours) |

| Day 3 | 4 tab /die | (1 tab every 4 hours) |

| Days 4-7 | 5 tab /die | (1 tab every 3 hours) |

| Days 8-14 | 6 tab /die | (1 tab every 2.5 hours) |

| Days 15-21 | 5 tab /die | (1 tab every 3 hours) |

| Days 22-28 | 4 tab /die | (1 tab every 4 hours) |

| Days 29-35 | 3 tab /die | (1 tab every 6 hours) |

| Days 36-40 | 2 tab /die | (1 tab every 12 hours) |

To our knowledge, in clinical research, this therapeutic scheme has been used once within a lung cancer screening trial, with promising results in terms of efficacy and safety. 12 In this peculiar setting the smoking cessation rate at 12 months was 32.1%, versus 7.3% in the control arm (e.g., volunteers allocated to lung cancer screening with any active support to stop smoking).

The Tobacco Control Unit of our Institution, Fondazione IRCCS Istituto Nazionale dei Tumori, Milan, has been active since 2001 and it is organized to provide patients with internationally-approved interventions for tobacco dependence, such as an integrated pharmacological and cognitive behavioral support. 3

With these premises, we found it useful to select patients who were prescribed cytisine for smoking cessation, follow them up for 12 months, and report the results.

Methods

Study design

This is a retrospective, real-life, observational study conducted at the anti-smoking center of the Fondazione IRCCS Istituto Nazionale dei Tumori between January 2016 and September 2022. Eligible patients for this study were adults willing to quit smoking and with no contraindication to receive cytisine. Patients who, in addition to cytisine, took NRT or electronic cigarette as additional support, were excluded from the study.

Patients voluntarily scheduled a visit to the anti-smoking center and they underwent a complete pneumological examination (Online Supplementary Material 2).

During the first visit the patient’s medical history and a physical examination were recorded. Subsequently, their smoking history, including the years of active smoking, the number of cigarettes smoked per day and any previous quit attempts were noted; furthermore, the Fagerström test for Nicotine Dependence, the Mondor Motivational Questionnaire and the exhaled CO (exCO) were collected. Finally, the pharmacological support was chosen with the patient among the validated therapies for smoking cessation (varenicline, bupropion, cytisine and nicotine replacement therapy).

For this study we selected only patients who were prescribed cytisine, in form of a galenic pharmaceutical formulation, with the new therapeutic scheme.

Patient bought the drug out of pocket at the cost of 75 euros.

Once the pharmacological treatment for smoking cessation was established, a proactive cognitive-behavioral support was scheduled. 3 The high-intensity telephone counseling consisted of eight calls of about 10 to 15 minutes over a period of 12 weeks and then on patients’ demand.

Medical follow up was scheduled at three, six, and 12 months.

During the three-, six- and 12-month follow-up visits, we recorded the self-reported seven-day point prevalence of smoking abstinence and its biochemical verification as measured by exCO (piCO™ Smokerlyzer®, Bedfont Scientific Ltd), the self-reported adverse events and the treatment’s drop-out, if they occurred.

Treatment

The therapeutic schedule of cytisine adopted in our anti-smoking center 11 involves an eight-day period of fast induction (from two capsules up to six capsules daily) and thereafter a gradual reduction, from six capsules daily to two capsules daily, over the fortieth day.

This cytisine scheme consists of a total of 165 capsules of 1.5 mg each and it has already been adopted by other Italian anti-smoking centers.

Study objectives

The primary endpoint was the self-reported seven-day point prevalence of smoking abstinence at three, six, and 12 months in subjects treated with cytisine. Abstinence was defined by the counselor with confirmation of a CO level of ⩽ 6 ppm. 13 If a participant missed the follow-up visit, the smoking abstinence data was collected based on phone-call; if the phone confirmation was not achieved, the participant’s smoking status was considered to be “unknown”.

We took into consideration the reduction in the smoking exposure (e.g. the number of cigarettes smoked daily) from the first visit to the three, six and 12-month follow-ups and the self-reported adverse events (AEs) as secondary endpoints.

During the phone calls, the counselor verified the pati-ent’s treatment compliance, the presence of any side effects and the existence of situations that could favor a smoking relapse.

Statistical analysis

This study was non-comparative, and analyses were descriptive and exploratory. Based on previous studies on smoking cessation, it was found that cytisine had a cessation rate of 46.7% while varenicline had a cessation rate of 37.0%. To detect a treatment effect with an alpha error of 0.05 and a power of 90%, a minimum of 267 subjects needed to be enrolled. The analysis included all participants who had received at least one dose of study medication. Baseline demographics characteristics were reported as number and percentage for categorical variables, meanwhile median and IQR were reported for continuous variables. Proportions were compared by the chi-squared test or Fisher’s exact test as appropriate. Continuous variables were compared by the Wilcoxon-Mann–Whitney test. Univariate and multivariate logistic regression models were implemented for self-reported seven-day point prevalence for abstinence at three, six and 12 months.

Results

Characteristics of the participants

A total of 300 participants received cytisine during the study. Table 2 reports the baseline characteristics of participants. The median age of the patients taken into account was 59 years; among them 57% were women and 43% were men. The median smoking exposure was 33.8 pack-years and the median number of cigarette smoked was 19.7 per day, with a median basal exCO of 19 ppm. The nicotine dependence, as measured by FTND, was 5 points (medium-high addiction) and the mean motivational score, as measured by the Mondor test, was 13 points (good level of motivation). The most frequently reported comorbidities were cardiovascular (38%), respiratory (35%), oncologic diseases (22.3%) and psychiatric diseases (20.3%).

Table 2.

Baseline demographics.

| Total | Women | Men | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N=300 | N=171 | N=129 | ||

| Age – Median (IQR) | 59 (15.00) | 60 (14.00) | 59 (16.00) | 0.3513 |

| Smoking history - Median (IQR) | ||||

| Carbon monoxide in exhaled breath, ppm* | 19 (13.00) | 19 (12.00) | 20 (15.00) | 0.3849 |

| FTND total score | 5 (3.00) | 5 (3.00) | 5 (2.00) | 0.5304 |

| Mondor total score | 13 (4.00) | 13 (4.00) | 13 (4.00) | 0.1174 |

| Pack-years | 33.75 (27.50) | 33 (26.50) | 37 (28.00) | 0.0826 |

| Number of cigarettes smoked, mean (STD) | 19.7 (9.0) | 18.0 (7.6) | 22 (10.0) | 0.0003 |

| Chronic diseases reported at baseline - n (%) | ||||

| Respiratory diseases | 105 (35.0) | 53 (31.0) | 52 (40.3) | 0.112 |

| Cardiovascular diseases | 114 (38.0) | 53 (31.0) | 61 (47.3) | 0.0056 |

| Cancer | 67 (22.3) | 37 (21.6) | 30 (23.3) | 0.7802 |

| Psychiatric | 61 (20.3) | 39 (22.8) | 22 (17.1) | 0.248 |

| Gastrointestinal | 49 (16.3) | 34 (20.0) | 15 (11.6) | 0.0598 |

| Endocrinological | 48 (16.0) | 29 (17.0) | 19 (14.7) | 0.6348 |

| Autoimmune | 8 (2.7) | 6 (3.5) | 2 (1.6) | 0.4733 |

There were six missing data for CO values.

Three-month outcome

At three months, the self-reported smoking abstinence was 68.7% (206/300), whereas 30.7% (92/300) of patients were still smokers (Figure 1), with a 0.7% of patients with missing data. Subjects with a high smoking exposure (e.g. ⩾ 30 pack-years) and subjects with a high nicotine dependence (e.g. FTND ⩾ 5 points) at baseline had a lower probability of quitting (Table 3), with an OR of 0.55 for pack-years (95% CI = 0.32-0.91) and 0.47 for FTND test (95% CI = 0.29 - 0.77), respectively. The mean (std) number of cigarettes per day in patients who failed to cease smoking decreased from 19.7 (8.95) at baseline to 10.1 (8.22) at three months (p value <.0001) (Online Supplementary Material 3).

Figure 1.

Smoking cessation status (N=300).

Table 3.

Univariate and multivariate logistic model for self-reported seven-day point prevalence of abstinence at three, six and 12 months.

| 3 mo. N=298 | 6 mo. N=259 | 12 mo. N=239 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Smoking cessation (%) a | OR (95%CI) univariate | OR (95%CI) multivariate | Smoking cessation (%) b | OR (95%CI) univariate | OR (95%CI) multivariate | Smoking cessation (%) c | OR (95%CI) univariate | OR (95%CI) multivariate | ||

| Sex | Female | 69.2 | reference | reference | 68.2 | reference | reference | 60.9 | reference | reference |

| Male | 69 | 0.99 (0.60 - 1.62) | 0.96 (0.57 - 1.64) | 61.3 | 0.74 (0.44 - 1.23) | 0.68 (0.39 - 1.18) | 57.4 | 0.87 (0.52 - 1.46) | 0.88 (0.50 - 1.53) | |

| Age | <45 | 70.5 | reference | reference | 72.2 | reference | reference | 65.6 | reference | reference |

| 45-64 | 67.7 | 0.88 (0.43 - 1.81) | 1.26 (0.55 - 2.93) | 61.8 | 0.62 (0.28 - 1.39) | 0.54 (0.22 - 1.33) | 56.1 | 0.67 (0.30 - 1.50) | 0.75 (0.31 - 1.84) | |

| ⩾ 65 | 71.3 | 1.00 (0.47 - 2-.31) | 1.45 (0.52 - 4.04) | 68.4 | 0.83 (0.35 - 1.98) | 0.56 (0.19 - 1.68) | 62.7 | 0.88 (0.37 -2.09) | 0.88 (0.30 -2.58) | |

| Pack-years | <30 | 76.7 | reference | reference | 65.1 | reference | reference | 62.1 | reference | reference |

| ⩾ 30 | 64.3 | 0.55 (0.32 - 0.91) | 0.67 (0.34 - 1.34) | 65.4 | 1.01 (0.60 - 1.70) | 1.95 (0.97 - 3.92) | 57.6 | 0.83 (0.49 - 1.41) | 1.19 (0.61 - 2.34) | |

| FTND score * | low dependence | 76.4 | reference | reference | 71 | reference | reference | 63.8 | reference | reference |

| high dependence | 60.2 | 0.47 (0.29 - 0.77) | 0.58 (0.32 - 1.02) | 57.7 | 0.56 (0.33 - 0.94) | 0.62 (0.34 - 1.14) | 53.1 | 0.64 (0.38 - 1.08) | 0.81 (0.44 - 1.48) | |

| Mondor score ¶ | high motivation | 72.2 | reference | reference | 65.9 | reference | reference | 59.8 | reference | reference |

| low motivation | 63 | 0.66 (0.39 - 1.09) | 0.74 (0.43 - 1.26) | 64 | 0.92 (0.54 - 1.58) | 1.09 (0.61 - 1.94) | 58.8 | 0.96 (0.56 - 1.66) | 1.10 (0.62 - 1.97) | |

| Chronic diseases | none | 77.1 | reference | reference | 75.5 | reference | reference | 67.3 | reference | reference |

| yes | 67.1 | 0.61 (0.32 - 1.17) | 0.62 (0.30 - 1.27) | 62.6 | 0.54 (0.27 - 1.08) | 0.45 (0.21 - 0.96) | 57.2 | 0.63 (0.31 - 1.28) | 0.60 (0.28 - 1.27) | |

| Carbon monoxide at baseline^ | 19.9 (10.0) | 0.97 (0.95 - 0.99) | 0.98 (0.96 - 1.00) | 19.4 (9.8) | 0.97 (0.95 - 0.99) | 0.97 (0.94 - 0.99) | 18.6 (8.5) | 0.97 (0.94 - 0.99) | 0.97 (0.94 - 0.99) | |

On the total number of 298 participants who returned at three months; b on the total number of 259 participants who returned at six months; c on the total number of 238 participants who returned at 12 months.

Fagerström test, classified as low-dependence subjects those with a score less than 6, subjects with high dependence those with a score greater than 5.

Mondor test, classified as high motivation to quit smoking subjects with a score greater than 11, subjects with low motivation those with a score less than 12.

The mean value of CO among quitters was reported.

Six-month outcome

At six months, smokers who successfully quit numbered 169/300, equal to 56.3% (Table 3). In the multivariate analysis, subjects with chronic diseases had a poor probability of stopping smoking, when compared with subjects without any disease (OR: 0.45, 95% CI = 0.21 - 0.96). Patients with a higher smoking intensity (e.g. higher eCO) at baseline were more likely to continuing smoking (OR: 0.97, 95% CI = 0.94 - 0.99, see Table 3). The mean (std) number of cigarettes smoked decreased to 11.2 (8.94) at six months. There was a slight increase in the number of cigarettes smoked between three and six months (Online Supplementary Material 3).

Twelve-month outcome

At the end of the study, 79.6% (239/300) of patients completed the 12-month follow-up; among these, smokers who successfully quit were 142/300 (47.3%) (Table 3). At baseline, their median level of exCO was 19 ppm while at 12 months the exCO for the 142 subjects who stopped smoking was 1.2 ppm; exCO values however, were available for 294/300 participants at the baseline while they were missing for 50% (71/142) of subjects at the end of the study, due to COVID-19 pandemic restrictions. On the other hand, the smoking exposure in patients who failed to quit, significantly decreased between the baseline and the twelfth month (19.7 versus 12.2 cigarettes smoked per day, p<0.001). In this population (97 subjects), the median exCO level available for the analysis was 15.8 ppm. In the multivariate analysis, only higher values of eCO at baseline resulted in a worse probability of stopping smoking (OR: 0.97, 95% CI = 0.94 - 0.99) (Table 3).

Compliance of treatment

A total of 48 (16%) subjects dropped out of the treatment. Twenty-five subjects discontinued cytisine due to adverse events, 14 for poor compliance and nine for inefficacy.

Adverse events

Among 300 participants who received the treatment, 31.3% developed an adverse event

(AE) (Table 4). The most frequently reported AEs were gastrointestinal disorders (10.3%), nausea (7.0%) and insomnia (4.0%); 29/300 patients, equal to 8.3% of the population discontinued the drug, due to AEs.

Table 4.

Adverse Events.

| Total (N = 300) | Chronic diseases (N = 239) | No-chronic diseases (N = 61) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Subjects with AEs, n (%) | 94 (31.3) | 76 (31.8) | 18 (29.5)* |

| Discontinuation caused by AE, n (%) | 25 (8.3) | 20 (8.4) | 5 (8.2) |

| Incidence of AEs, n (%) | |||

| Gastrointestinal disorder | 31 (10.3) | 29 (12.1) | 2 (3.3) |

| Nausea | 21 (7.0) | 17 (7.1) | 4 (6.6) |

| Insomnia | 12 (4.0) | 8 (3.3) | 4 (6.6) |

| Constipation | 12 (4.0) | 9 (3.8) | 3 (4.9) |

| Nervousness | 11 (3.7) | 8 (3.3) | 3 (4.9) |

| Exhaustion | 8 (2.7) | 7 (2.9) | 1 (1.6) |

| Migraine | 8 (2.7) | 7 (2.9) | 1 (1.6) |

| Increased appetite | 8 (2.7) | 6 (2.5) | 2 (3.3) |

| Dry mouth | 6 (2.0) | 4 (1.7) | 2 (3.3) |

| Dizziness | 4 (1.3) | 2 (0.8) | 2 (3.3) |

| Abnormal dreams | 4 (1.3) | 3 (1.3) | 1 (1.6) |

| Taste alteration | 2 (0.7) | 2 (0.8) | 0 |

| Other¶ | 12 (4.3) | 10 (4.2) | 2 (3.3) |

| Death | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.4) | 0 |

Participants who reported more than one event in the same category were counted only once.

P value = 0.73.

Others include: muscle aches, increased blood sugar; tachycardia / heartbeat; increase in blood pressure; retching; hot flashes at night and under exertion; kidney pain; poor diuresis; tremor; decrease in blood pressure; tachycardia; polyuria; chest tightness.

Within the study population, one death occurred; this was non-related to the treatment, as the subject died due to lung cancer.

Discussion

Cigarette smoking is a leading cause of preventable disease and premature death, as well as a form of addiction that is hard to fight. Addiction can be so deep-rooted that even after an oncological diagnosis, the majority of patients are unable to stop smoking. 14

In the present work we report data about an integrated pharmacological-behavioral intervention with a novel scheme of cytisine, a partial agonist of the α4β2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors, with an escalating dose regimen and an extended duration of the treatment. 11

The results of our preliminary experience in a real-life setting are satisfactory, with a smoking cessation rate of 47.3% at 12 months. These observations are encouraging but they may be due to different factors.

First of all, these results were obtained with a different drug schedule, 11 as compared to the historical one where the drug is administered over 25 days in a down- titration. This scheme is meant to resemble the schedule of varenicline and bupropion, two drugs already approved for smoking cessation, where an induction period is conceived; this fact allowed the clinicians to assess the tolerability of the drug and in the meantime the smoker, appreciating its effectiveness, is thus encouraged in his quitting attempt.

Moreover, even though a new therapeutic schedule was devised, we did not record any safety issue; the therapeutic drop out was 8.3%, lower than previously reported by Zatonskiet et al. 6 Gastrointestinal AEs such as nausea, abdominal pain and constipation are relatively common side effects of cytisine and other smoking cessation aids; insomnia is a known side effect of cytisine, as it can cause agitation and restlessness in some individuals; nicotine withdrawal symptoms can both affect the digestive and the nervous system, too. While these side effects can be uncomfortable, in our population they were generally mild and temporary.

Our data of effectiveness and tolerability confirms and reinforces the preliminary experience of Pastorino et al., 12 where this regimen was adopted. The comparison between a real-life experience and a lung cancer screening trial must be considered in the light of the context differences, but taken as a whole the results are promising (47.3% versus 32.1% at 12 months). We may speculate that a patient who scheduled voluntarily a visit to the anti-smoking center is more motivated to stop smoking than a smoker recruited in a clinical study. In fact, subjects allocated to an active screening may perceive low-dose CT as a relief for their dangerous behavior; 15 our real-life population showed a high degree of motivation to quit smoking (Mean Mondor Motivational Questionnaire of 13 points) and this may be an explanation for the high quitting rates.

On the other hand we believe that providing a motivated patient with an integrated smoking cessation support 3 is a major contributing factor to their success. Our patients received proactive cognitive-behavioral support that may have encouraged the cessation attempt.

Beyond this observation, it should be noted that all the anti-tobacco treatments are currently paid by patients and not by the Italian Health System, as far as varenicline was reimbursed under specific medical conditions (COPD and cardiovascular disease) 16 but is unavailable for prescription since July 2021. 4 With these premises, cytisine makes it conceivable to effectively treat patients at a significantly lower costs and this may in turn impact on the drug retention.

From a data collection perspective, the pandemic affected the exCO evaluation from March 2020 to December 2021. The SARS-CoV-2 virus may contaminate the Smokerlyzer® and this had repercussions on the biological verification of smoking abstinence; to overcome this problem, starting from June 2021, we were able to perform the test by applying an antimicrobial filter to the instruments, but we still registered 50% of missing exCO data at the end of the study. Indeed, our data, albeit partial, are very solid, with an average CO of 1.28 ppm in those who declared themselves abstinent. 17

The non-randomized design of the study impacts on the reliability of the intervention and this is a major limitation of the study. It is necessary to test this modified dosage through randomized trials to verify the validity of these results.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-tmj-10.1177_03008916231216906 for Cytisine as a smoking cessation aid: Preliminary observations with a modified therapeutic scheme in real life by Paolo Pozzi, Roberto Boffi, Chiara Veronese, Sara Trussardo, Camilla Valsecchi, Federica Sabia, Ugo Pastorino, Giovanni Apolone, Elisa Cardani, Francesco Tarantini and Elena Munarini in Tumori Journal

Footnotes

Contributions: CVe, EM made substantial contributions to the study conception and design, ST, EC, FT performed the acquisition of data. CVa, FS performed analysis and interpretation of data. PP, EM drafted the work and revised it critically for important intellectual content, UP, GA, RB gave the final approval for the version to be published.

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethics approval: The Ethical Committee approved the study protocol (INT 39/23 approved on 2023/02/27)

ORCID iDs: Chiara Veronese  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1414-342X

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1414-342X

Ugo Pastorino  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9974-7902

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9974-7902

Supplemental material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1. Tabagismo. Ministero della Salute. 2022. https://www.salute.gov.it/portale/fumo

- 2. Hughes JR, Keely J, Naud S. Shape of the relapse curve and long-term abstinence among untreated smokers. Addiction 2004; 99: 29-38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. European Network for Smoking and Tobacco Prevention aisbl (ENSP), Guidelines for treating tobacco dependence. 2020. https://ensp.network/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/guidelines_2020_english_forprint.pdf

- 4. Direct Healthcare Professional Communication July 2021. CHAMPIX (varenicline) - lots to be recalled due to presence of impurity N-nitroso-varenicline above the Pfizer acceptable daily intake limit. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/dhpc/champix-varenicline-lots-be-recalled-due-presence-impurity-n-nitroso-varenicline-above-pfizer. European Medicines Agency [Google Scholar]

- 5. Gotti C, Clementi F. Cytisine and cytisine derivatives. More than smoking cessation aids. Pharmacol Res. 2021; 170: 105700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Zatonski W, Cedzynska M, Tutka P, et al. An uncontrolled trial of cytisine (Tabex) for smoking cessation. Tob Control. 2006; 15: 481-484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Walker N, Howe C, Glover M, et al. Cytisine versus nicotine for smoking cessation. N Engl J Med. 2014; 371: 2353-2362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Courtney RJ, McRobbie H, Tutka P, et al. Effect of cytisine vs varenicline on smoking cessation: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2021; 326: 56-64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Walker N, Smith B, Barnes J, et al. Cytisine versus varenicline for smoking cessation in New Zealand indigenous Māori: a randomized controlled trial. Addiction 2021; 116: 2847-2858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Rigotti NA, Benowitz NL, Prochaska J, et al. Cytisinicline for smoking cessation: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2023; 330: 152-160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Tinghino B, Baraldo M, Mangiaracina G, et al. Cytisine as a treatment for smoking cessation. Tabaccologia 2015; 2: 1-8. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Pastorino U, Ladisa V, Trussardo S, et al. Cytisine therapy improved smoking cessation in the randomized screening and multiple intervention on lung epidemics lung cancer screening trial. J Thorac Oncol. 2022: S1556-0864(22)00346-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Middleton ET, Morice AH. Breath carbon monoxide as an indication of smoking habit. Chest. 2000; 117: 758-763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Taborelli M, Dal Maso L, Zucchetto A, et al. Prevalence and determinants of quitting smoking after cancer diagnosis: a prospective cohort study. Tumori. 2022; 108: 213-222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Pozzi P, Munarini E, Bravi F, et al. A combined smoking cessation intervention within a lung cancer screening trial: a pilot observational study. Tumori. 2015; 101: 306-311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Gazzetta Ufficiale della Repubblica italiana. Riclassificazione del medicinale per uso umano Champix. 2019. https://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/eli/gu/2019/09/13/215/sg/pdf

- 17. Munarini E, Veronese C, Ogliari AC, et al. Covid-19 does not stop good practice in smoking cessation: safe use of CO analyzer for smokers in the Covid era. Pulmonology. 2020; 27: 173-174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-tmj-10.1177_03008916231216906 for Cytisine as a smoking cessation aid: Preliminary observations with a modified therapeutic scheme in real life by Paolo Pozzi, Roberto Boffi, Chiara Veronese, Sara Trussardo, Camilla Valsecchi, Federica Sabia, Ugo Pastorino, Giovanni Apolone, Elisa Cardani, Francesco Tarantini and Elena Munarini in Tumori Journal