ABSTRACT

Whole-genome sequencing (WGS) of microbial pathogens recovered from patients with infectious disease facilitates high-resolution strain characterization and molecular epidemiology. However, increasing reliance on culture-independent methods to diagnose infectious diseases has resulted in few isolates available for WGS. Here, we report a novel culture-independent approach to genome characterization of Bordetella pertussis, the causative agent of pertussis and a paradigm for insufficient genomic surveillance due to limited culture of clinical isolates. Sequencing libraries constructed directly from residual pertussis-positive diagnostic nasopharyngeal specimens were hybridized with biotinylated RNA “baits” targeting B. pertussis fragments within complex mixtures that contained high concentrations of host and microbial background DNA. Recovery of B. pertussis genome sequence data was evaluated with mock and pooled negative clinical specimens spiked with reducing concentrations of either purified DNA or inactivated cells. Targeted enrichment increased the yield of B. pertussis sequencing reads up to 90% while simultaneously decreasing host reads to less than 10%. Filtered sequencing reads provided sufficient genome coverage to perform characterization via whole-genome single nucleotide polymorphisms and whole-genome multilocus sequencing typing. Moreover, these data were concordant with sequenced isolates recovered from the same specimens such that phylogenetic reconstructions from either consistently clustered the same putatively linked cases. The optimized protocol is suitable for nasopharyngeal specimens with diagnostic IS481 Ct < 35 and >10 ng DNA. Routine implementation of these methods could strengthen surveillance and study of pertussis resurgence by capturing additional cases with genomic characterization.

KEYWORDS: Bordetella pertussis, whole-genome sequencing, metagenomics, surveillance

INTRODUCTION

Whooping cough (“pertussis”) remains a persistent public health challenge with highest rates of morbidity and mortality reported in infants less than 2 months old (1). Although coverage with pertussis-containing vaccines among children remains high, cases increased steadily in the United States from the late 1980s until the start of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020. Waning protection conferred by acellular vaccines, adopted by many industrialized countries beginning in the 1990s, likely contributes to increased disease among vaccinated individuals, more so than longer-lasting protection offered by whole-cell formulations (2, 3). The causative agent, Bordetella pertussis, exhibits little molecular variation, and recent mutations to genes encoding immunogenic proteins included in current acellular pertussis vaccines have swept the population quickly, evidence of likely vaccine-driven selection (4–6). However, additional questions regarding the role of pathogen ecology and evolution in pertussis resurgence remain unanswered (7, 8).

High-throughput sequencing has transformed public health microbiology (9) and recent whole-genome sequencing (WGS) analyses of B. pertussis have revealed new insights about the pathogen’s population structure and dispersion through high-resolution characterization of clinical isolates (5, 10–13). But effective pertussis genomic surveillance, and subsequent study of pathogen contributions to disease resurgence, is limited by the declining use of diagnostic culture as fewer clinical isolates are available for WGS (14). Multiple influences lead to the decrease in cultured B. pertussis isolates, such as adoption of culture-independent diagnostic tests (CIDTs) and multi-pathogen respiratory panels, reliance on commercial testing providers, and stability of selective transport media, some of which limit culture of microbial pathogens more broadly (15). Additionally, the specificity of different pertussis diagnostic methods varies with patient age, timing of specimen collection (i.e., in relation to cough onset), and vaccination status (16). As a result, Enhanced Pertussis Surveillance (EPS) as part of the Emerging Infections Program, which conducts systematic case ascertainment and augmented data collection across seven states that include ~7.0% of the US population, recovers B. pertussis isolates for, on average, fewer than 3.5% of captured cases annually (17).

Shotgun metagenomics can identify individual microbes within complex mixtures (18), and computational techniques now allow recovery of metagenome-assembled genomes from environmental samples (19, 20). Although metagenomics promises a pathogen-agnostic assay platform for detection as well as characterization, clinical and public health applications routinely face the twofold challenge of low target abundance and high background contamination from the host patient and co-occurring microorganisms (21, 22). In practice, many samples collected for infectious disease diagnosis, including nasopharyngeal (NP) specimens for suspected pertussis, are heavily loaded with human cells or exogenous DNA, limiting recovery of microbial genomic information and thus assay sensitivity. As a result, multiple laboratory approaches have been introduced to improve microbial pathogen recovery, including selective lysis (23, 24), whole-genome amplification (25–27), and target enrichment (28). Successful application of these tools has enabled molecular characterization for improved outbreak investigation and surveillance (29–31). For pertussis specifically, thus far, selective lysis treatment of NP specimens has shown only modest improvement in recovery of B. pertussis genomic data (23). Alternatively, the relatively limited gene content diversity of B. pertussis may benefit from target enrichment or amplification approaches that rely on existing genomic data to synthesize RNA probes or oligo primers, provided the added cost can be minimized (28, 32).

Here, we present the development of novel methodology for culture-independent whole-genome sequencing (CIWGS) of B. pertussis from residual, positive diagnostic nasopharyngeal specimens, reducing reliance on culture for genomic data. Target enrichment via in-solution hybridization with a custom whole-genome RNA bait library yielded sequencing reads that comprised up to 90% B. pertussis genomic data while simultaneously reducing host contamination to below 10%. The resulting data were sufficient for robust genomic characterization concordant with that of cultured B. pertussis isolates using standard bioinformatic tools. These results demonstrate that CIWGS directly from residual specimens can enable molecular characterization of more pertussis cases, improving genomic surveillance and study of B. pertussis contributions to disease resurgence.

RESULTS

Laboratory optimization

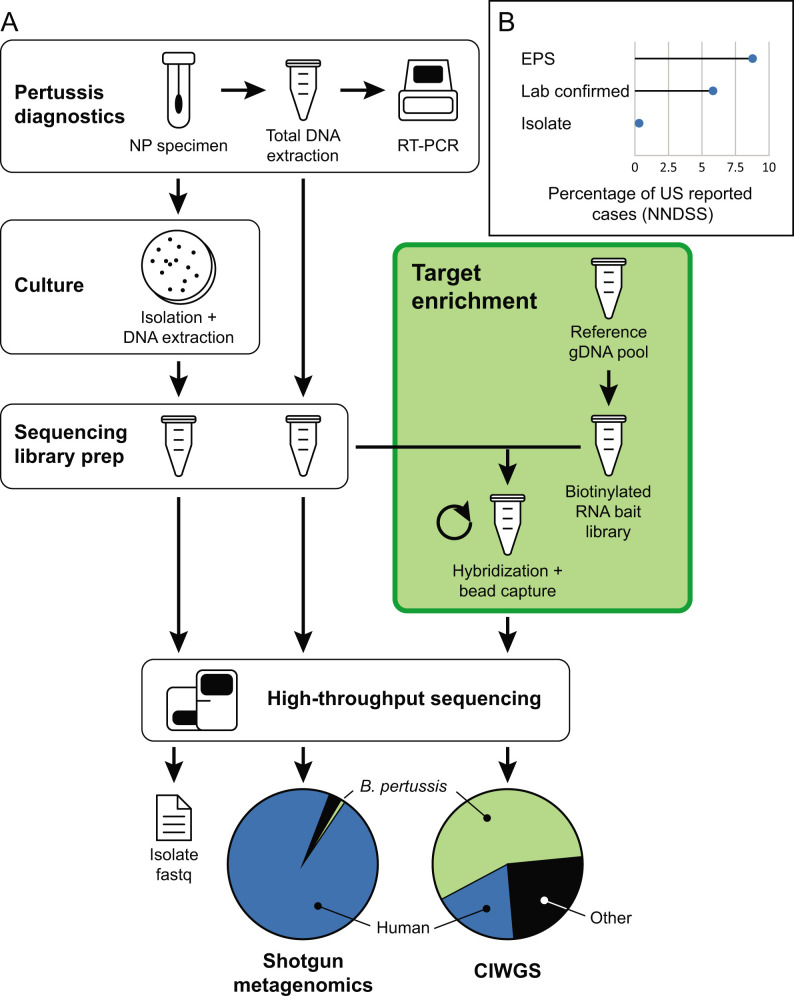

The CIWGS laboratory workflow was designed to complement existing, validated protocols for pertussis diagnosis from NP specimens. A schematic overview of the workflow is presented in Fig. 1 and centers around hybridization of RNA “baits” to sequencing library fragments that contain matching target B. pertussis genomic fragments. RNA bait libraries were prepared from a mixture of 10 B. pertussis isolates selected to cover the breadth of genomic diversity common among the bacterial population (Table S1). Laboratory parameters for target enrichment were optimized using pooled PCR-positive clinical specimens as input material for library preparation. Performance of RNA bait hybridization was tested at various temperatures and DNA sequencing library inputs to maximize B. pertussis enrichment, which was evaluated by real-time (RT) PCR assay (Fig. S1). Enrichment fold changes after RNA bait hybridization were calculated from IS481 Ct values with diagnostic RT-PCR and normalized with the concentrations of the DNA libraries (Fig. S1). The highest enrichment fold (3,079×) was observed at hybridization temperature of 67.5°C, and greater DNA sequencing library input yielded more B. pertussis DNA fragments captured by the RNA bait library (Fig. S1).

Fig 1.

Schematic overview of the CIWGS workflow, which utilizes a RNA bait library for target enrichment of B. pertussis genome fragments within a sequencing library prepared directly from DNA extracts of residual NP species used for diagnostics. (A) RNA baits are prepared from a diverse mixture of B. pertussis isolates (Table S1), and target enrichment yields significantly more sequencing reads containing B. pertussis genomic data than shotgun metagenomics. (B) Less than 4% of annual reported pertussis cases is culture positive. This approach increases case coverage for genomic surveillance.

Recovery from spiked specimens

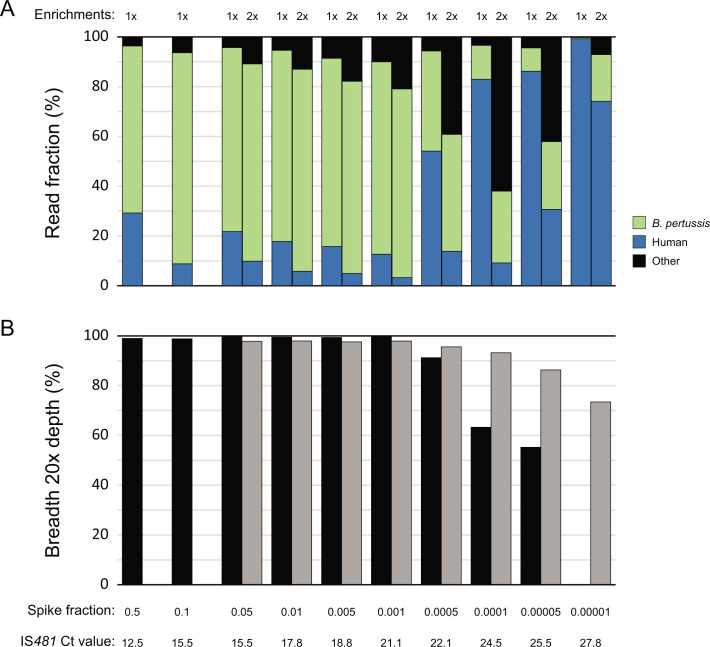

Recovery of B. pertussis genome sequence data was first assessed with a series of mock specimens prepared from a mixture of commercial human DNA and a microbiome standard spiked with reducing concentrations (n = 20) of extracted B. pertussis isolate DNA. Enrichment was evaluated by mapping sequencing reads to an existing reference-quality genome assembly for the same isolate with the minimum acceptance criteria set at 85% of reference positions (breadth) with ≥ 20× coverage. Sequencing the background mock mixture produced only reads that mapped to regions of the rRNA operon highly conserved among bacteria. The proportion of B. pertussis sequencing reads was consistently enriched to an average 76% at spiked fractions down to 0.001 (IS481 Ct = 21.1), and additional reads could be recovered at lower concentrations with a subsequent round of enrichment (Fig. 2A). Mapping filtered B. pertussis sequencing reads and quantifying coverage breadth indicated that over 98% of the expected 4.1 Mbp was recovered with at least 20× depth at spiked fractions down to 0.001 and at least 90% at fraction 0.0001 (IS481 Ct = 24.5) following a second enrichment (Fig. 2B).

Fig 2.

B. pertussis genomic data recovery from mock specimens spiked with reducing concentrations of isolate DNA following either 1× or 2× enrichments. (A) The fraction of sequencing reads containing B. pertussis (green), human (blue), or other (black) genomic data. (B) Coverage breadth at 20× depth across a B. pertussis reference genome assembly at 1× (black) or 2× (gray) enrichments.

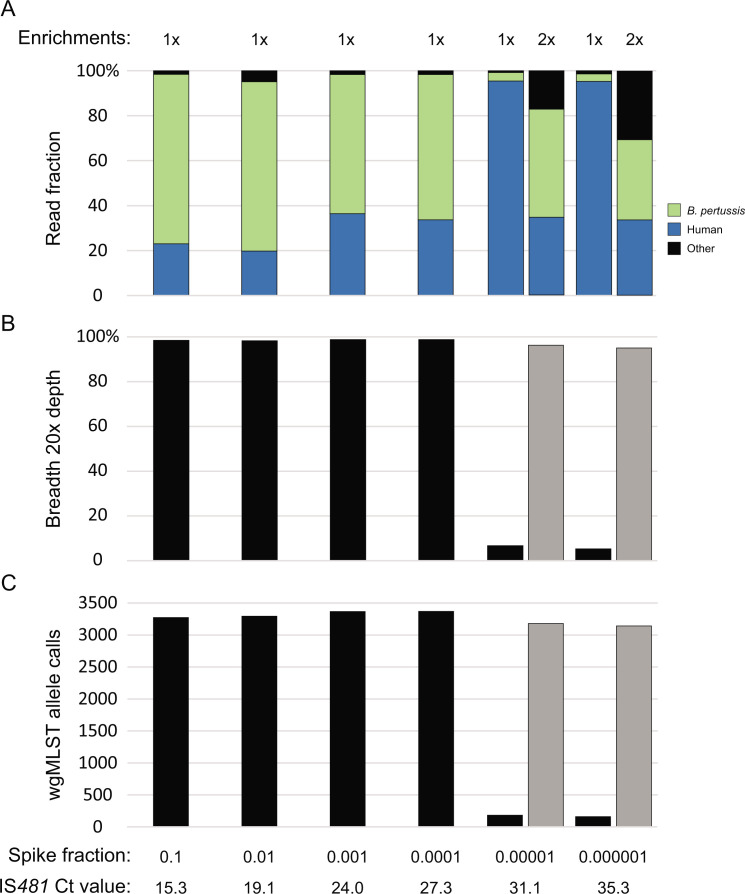

Sequence recovery was further evaluated in a similar manner by spiking B. pertussis cells at reducing concentrations (n = 23) into a pooled mixture of pertussis-negative NP aspirates collected during a previous diagnostic method validation (16), the background microbial composition of which was devoid of any Bordetella species with only spurious detection by metagenomic read classification (Table S2). Target enrichment yielded significant recovery of B. pertussis sequencing reads (Fig. 3A). The average coverage breadth at 20× depth of at least 98% was observed down to a spike fraction of 0.0001 (IS481 Ct = 27.3) with 1× enrichment and above 95% down to 0.000001 (IS481 Ct = 35.3) with 2× enrichments (Fig. 3B). Filtered B. pertussis reads were sufficient for downstream characterization by whole-genome multilocus sequencing typing (wgMLST), exceeding the minimum 3,000 allele call threshold established previously (Fig. 3C) (33). Detailed metrics are provided in Table S3. By comparison, shotgun metagenomic (unenriched) sequencing of residual NP specimens with diagnostic IS481 Ct = 11–28 produces reads almost entirely composed of human genomic data and covered <1% of B. pertussis genome nucleotides with 20× depth (Table S4). Direct comparison of residual clinical specimens sequenced in parallel with and without target enrichment further illustrated the improved B. pertussis genome recovery of the CIWGS workflow (Table S5).

Fig 3.

B. pertussis genomic data recovery from pooled negative clinical specimens spiked with dilutions of isolate cells following either 1× or 2× enrichments. (A) The fraction of sequencing reads containing B. pertussis (green), human (blue), or other (black) genomic data. (B) Coverage breadth at 20× depth across a B. pertussis reference genome assembly following 1× (black) or 2× (gray) enrichments. (C) wgMLST allele calls following 1× (black) or 2× (gray) enrichments.

Accuracy and specificity

The accuracy of CIWGS was assessed by comparing read data from spiked specimens, both mock mixtures (n = 16 positive) and pooled pertussis-negative NP aspirates (n = 16 positive, n = 10 negative) described above, to previous sequence data from the added B. pertussis isolate. Sequencing reads were first filtered by subtractive mapping to a human reference assembly and then mapped to the existing reference-quality genome assembly matching the added B. pertussis isolate with the same minimum 85% breadth at 20× coverage criteria as above. In all cases, no single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) differences were detected when mapping filtered CIWGS reads from spiked specimens to the corresponding genome assembly. The calculated percent agreement was 100% [true positive (TP) = 32/32], and the overall percent agreement was 100% [TP = 32, true negative (TN) = 10, false positive (FP) = 0, and false negative (FN) = 0], according to formulas listed in the Materials and Methods. Additionally, no SNP differences were observed in the direct comparison of CIWGS reads from 1× and 2× enrichment of the same spiked specimen (Table S6).

The specificity of CIWGS for B. pertussis was evaluated by separately spiking pooled pertussis-negative NP aspirates with extracted DNA from two related species, B. holmesii and B. parapertussis. Hybridization with the B. pertussis RNA baits did capture and enrich sequencing library fragments from both B. holmesii C690 and B. parapertussis J859, whose genome-wide average nucleotide identity (ANI) compared with B. pertussis C734 was 82.6% and 98.8%, respectively. Recovered B. holmesii reads were limited to loci of high sequence homology and covered only 27.7% of the B. pertussis reference genome with 20× depth (Fig. S2; Table S3). Significantly more B. parapertussis sequencing reads were recovered and mapped more evenly to cover 87% with 20× coverage (Fig. S2; Table S3), consistent with the closer phylogenetic history of the species (10, 11, 34).

Taken together, the results from sequencing spiked specimens suggest a baseline limit of detection for CIWGS at diagnostic IS481 Ct < 30 for 1× enrichment and IS481 Ct < 35 for 2× enrichment. DNA extracts from residual pertussis-positive NP specimens with at least 10 ng total DNA should yield enough filtered sequencing read data sufficient for B. pertussis genomic characterization by SNPs or cgMLST/wgMLST (breadth 20× > 95%). Although genome fragments from closely related species are cross-reactive with the RNA bait library, filtered reads from B. holmesii or B. parapertussis will fail to meet minimum coverage thresholds or exceed expected SNP density, respectively.

Surveillance specimens with matched isolates

Finally, CIWGS was evaluated with a set of 29 residual pertussis-positive NP specimens collected through the EPS program and from which cultured isolates were also available for independent sequence confirmation compared with a set of 28 unenriched NP specimens (TN). Diagnostic IS481 Ct values exhibited by the selected specimens were consistent with those typically collected for laboratory confirmation during 2011–2019 (Fig. S3). Filtered read recovery from the 29 surveillance specimens was similar to that observed from spiked negative specimens (Fig. 3) and yielded sufficient data for genomic characterization with >80% breadth at 20× depth and >3,000 wgMLST allele calls (Table 1; Table S7; Fig. S4).

TABLE 1.

Comparison of matched specimen CIWGS and isolate sequencing

| Specimen ID | IS481-Ct | DNA (ng/μL) | Num enrichments | Isolate ID | Isolate accession | CIWGS breadth 20×a | SNPs by Ref mappingb | SNPs vs PacBio assemblyc | CIWGS accession |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EPS01 | 19.7 | 1.2 | 1 | J979 | SRR10002514 | 98.32 | 0 | NAd | SRR27109067 |

| EPS02 | 22.7 | 2.5 | 1 | J984 | SRR10002466 | 95.30 | 0 | NA | SRR27109066 |

| EPS03 | 23.6 | 0.9 | 2 | J996 | SRR10002457 | 93.54 | 0 | NA | SRR27109065 |

| EPS04 | 22.3 | 6.0 | 1 | J968 | SRR9988730 | 95.42 | 0 | NA | SRR27109064 |

| EPS05 | 16.8 | 2.9 | 1 | J808 | SRR9131699 | 99.48 | 0 | NA | SRR27109063 |

| EPS06 | 25.3 | 2.5 | 2 | J836 | CP033293 | 87.44 | 0 | 0 | SRR27109061 |

| EPS07 | 14.5 | 0.1 | 1 | J841 | SRR9997167 | 99.83 | 0 | NA | SRR27109060 |

| EPS09 | 18.3 | 7.1 | 1 | J733 | CP046988 | 86.89 | 0 | 0 | SRR27109059 |

| EPS12 | 14.9 | 4.6 | 1 | J722 | SRR9131707 | 99.84 | 0 | NA | SRR27109058 |

| EPS14 | 16.3 | 0.1 | 1 | J726 | SRR9131600 | 97.70 | 0 | NA | SRR27109105 |

| EPS15 | 19.2 | 3.5 | 1 | J727 | SRR9131601 | 96.27 | 0 | NA | SRR27109104 |

| EPS17 | 21.7 | 3.2 | 1 | J788 | SRR9131623 | 94.93 | 0 | NA | SRR27109103 |

| EPS18 | 13.6 | 0.1 | 1 | J789 | SRR9131622 | 99.02 | 0 | NA | SRR27109102 |

| EPS20 | 12.0 | <0.1 | 1 | K056 | CP114533 | 99.70 | 0 | 0 | SRR27109101 |

| EPS22 | 21.6 | 7.6 | 1 | K712 | CP094044 | 94.21 | 0 | 0 | SRR27109100 |

| EPS24 | 27.8 | 11.8 | 1 | L021 | CP093981 | 99.81 | 0 | 0 | SRR27109098 |

| EPS28 | 18.0 | <0.1 | 1 | K921 | CP094014 | 99.39 | 0 | 0 | SRR27109097 |

| EPS29 | 14.3 | 12.0 | 1 | J866 | CP033281 | 99.92 | 0 | 0 | SRR27109096 |

| EPS31 | 18.2 | 10.8 | 1 | J816 | CP033295 | 99.81 | 0 | 0 | SRR27109095 |

| EPS32 | 17.2 | 2.1 | 1 | K439 | SRR10247384 | 99.77 | 0 | NA | SRR27109094 |

| EPS33 | 25.5 | 1.1 | 1 | K926 | CP094013 | 97.80 | 0 | 0 | SRR27109093 |

| EPS34 | 14.7 | <0.1 | 1 | K911 | CP094016 | 99.64 | 0 | 0 | SRR27109092 |

| EPS35 | 20.2 | 2.1 | 1 | K447 | SRR9718349 | 99.55 | 0 | NA | SRR27109091 |

| EPS36 | 23.0 | 24.2 | 1 | K124 | SRR10002473 | 94.70 | 0 | NA | SRR27109090 |

| EPS37 | 17.5 | 4.4 | 1 | K129 | CP114532 | 99.20 | 0 | 0 | SRR27109089 |

| EPS38 | 18.4 | <0.1 | 1 | K135 | CP114531 | 97.78 | 0 | 0 | SRR27109087 |

| EPS39 | 14.3 | 5.6 | 1 | K140 | CP114530 | 99.63 | 0 | 0 | SRR27109086 |

| EPS40 | 19.1 | 6.6 | 1 | K232 | CP114535 | 98.43 | 0 | 0 | SRR27109085 |

| EPS41 | 27.6 | 4.1 | 1 | K237 | CP114534 | 89.81 | 0 | 0 | SRR27109084 |

Percentage of nucleotides in the reference genome covered by at least 20× depth.

Number of detected SNPs between matched CIWGS and isolate sequences as determined relative to the reference genome (see Materials and Methods).

Number of detected SNPs in CIWGS sequences as determined relative to the existing PacBio assembly of the matched isolate genome, if available.

NA, not applicable.

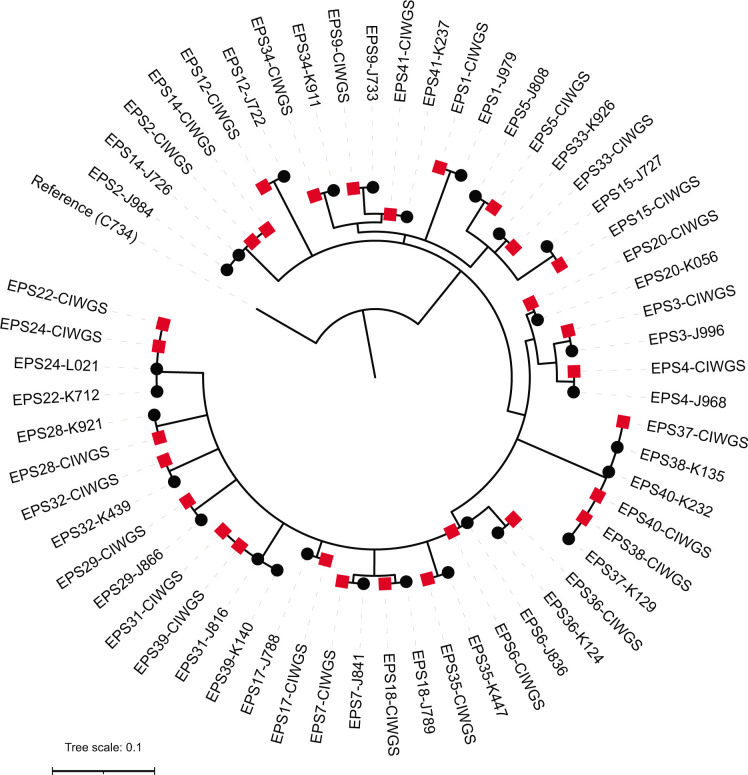

Sequence accuracy was assessed by comparing SNP calls between matched CIWGS and isolate sequencing reads relative to the reference assembly for C734. Detected SNPs were concordant, with all 29 pairs exhibiting no SNP differences (Table 1). Similarly, reference-quality assemblies were available for 15 isolates and additional SNP detection by directly mapping corresponding CIWGS reads also revealed no SNP differences (Table 1). The calculated percent agreement was 100% (TP = 29/29), and the overall percent agreement was 100% (TP = 29, TN = 28, FP = 0, and FN = 0), according to calculations listed in the Materials and Methods. To assess the consistency of CIWGS for genomic epidemiology, detected SNPs were used to reconstruct phylogenies from either the CIWGS or matched isolate data alone, as well as mixed together. Phylogenetic trees calculated from either CIWGS or isolate sequence data alone demonstrated concordant topologies, consistently clustering groups of putatively linked cases (Fig. S5). Combined phylogenetic reconstruction of CIWGS and isolate sequence data accurately placed all matching pairs jointly in the resulting tree, also capturing potential linkages among the sampled cases predicted by either data type alone (Fig. 4). However, core SNP alignments including CIWGS read data exhibited shorter sequence lengths and thus effectively lower resolution, compared with those of isolate sequences alone due to an average one position per CIWGS sequence that were randomly distributed (CIWGS: 134 bp, isolates: 173 bp, and combined: 124 bp).

Fig 4.

Phylogenetic reconstruction of matched CIWGS (red squares) and isolate (black circles) sequences from 29 surveillance specimens, reconstructed with 124 core, variable sites using maximum likelihood.

The matched data from these 29 surveillance cases were similarly compared by allele-based cluster detection using wgMLST. Allele profiles were concordant between CIWGS and isolate sequence data, with all pairs exhibiting no allele differences in a minimum spanning tree (Fig. S6A; Table 1). However, clustering isolate sequences alone revealed additional segregation among the cases, concordant with the SNP phylogeny, whereas a tree of only CIWGS data closely resembled the combined tree (Fig. S6B and C). As with the SNP alignments, wgMLST allele profile comparisons with CIWGS read data featured fewer available polymorphic loci for analyses (CIWGS: 49 loci, isolates: 99 loci, and combined: 37 loci). Quality metrics indicated that CIWGS yielded poor de novo assemblies that were more fragmented and contained more ambiguous bases than those from matched isolate sequences (Fig. S7A through D; Table S7), which negatively impact allele calling in BioNumerics. Consensus allele calling rates from CIWGS data were often lower those than from their matched isolate sequences (Fig. S7E and F) and were not limited to specific scheme loci, suggesting that CIWGS data may yield lower resolution for wgMLST due to poor assembly performance.

Detecting resistance mutations

Detection of antimicrobial resistance determinants by CIWGS was tested using two residual pertussis-positive NP specimens (PPHF 1999 and 3123) which putatively contained macrolide-resistant B. pertussis (MRBP) as determined by PCR targeting mutant 23S rRNA alleles (35). Indeed, alignment of filtered CIWGS reads to 23S allele references confirmed a homozygous A2047G mutation of 23S in PPHF1999 and heterozygous A2047G mutation in PPHF3123 (Table S8), concordant with RT-PCR (data not shown). Furthermore, filtered CIWGS reads from PPHF1999 also detected fhaB3, an allele primarily associated with MRBP isolated in East Asia (13).

DISCUSSION

We developed a target enrichment approach to CIWGS of B. pertussis directly from residual specimens used for positive clinical diagnosis. Advances in genomics and bioinformatics have modernized the study of microbial pathogens through reproducible, high-resolution strain characterization for molecular typing and epidemiology (9). However, concurrent widespread application of CIDTs like multiplex PCR or multi-pathogen panels have led to declines in available cultured isolates, often necessary inputs for WGS, from positive cases of bacterial pathogens like B. pertussis. The results presented here, while not a formal validation sufficient under CLIA (Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments) or similar certification, demonstrate the feasibility of CIWGS for accurate recovery of B. pertussis genomes from residual positive specimens that can be collected through an existing enhanced surveillance program. Application of these methods has the potential to strengthen surveillance, study the role of B. pertussis in disease resurgence, and monitor possible clinical impacts on vaccine-driven evolution by capturing additional cases with genomic characterization.

Although increased use of CIDTs has improved pertussis diagnosis and surveillance (14, 17), these gains have come at the cost of reduced availability of cultured B. pertussis isolates for laboratory characterization, including WGS. Increasing applications of clinical metagenomics may seem like an attractive alternative, capable of performing both detection and characterization in a single assay, but high levels of host patient contamination in NP specimens make pathogen genome recovery from shotgun sequencing challenging. The wide application of CIDTs, as well as variability among approved assay protocols (36, 37), currently used for pertussis diagnostics among US health laboratories makes replacement with metagenomic detection unrealistic.

The design approach implemented here intentionally focused on residual specimen material, which would often otherwise be discarded following diagnostic testing, to avoid impacting existing, validated protocols. To maximize the utility of available positive specimens during method development, additional surrogate specimens, prepared by spiking mock and negative specimens, were needed to optimize and evaluate the CIWGS workflow. Furthermore, focus on positive specimens both separates genomic characterization from variable case definitions and minimizes errors near the limit of detection. The present study featured both NP aspirates and NP swabs, both suitable for detection of B. pertussis by RT-PCR (38), based on availability though only the former are typical of current diagnostic practice. A larger collection of NP specimens will be required to assess potential influences of NP specimen types, transport media, or other technical characteristics on CIWGS performance.

Previous evaluation of selective lysis demonstrated modest improvement in B. pertussis genome recovery from positive specimens (23), and similar results were obtained in preliminary testing prior to the development described here (data not shown). Instead, target enrichment takes advantage of the limited genetic diversity observed in B. pertussis, which often confounds conventional molecular assays (39), to capture conserved genome content. The required hybridization between RNA and single-stranded DNA depends on a minimal degree of sequence homology, and the prepared RNA bait library must cover the expected level of divergence and content within the species; otherwise, informative tracts of the pathogen genome may fail to be amplified for sequencing. Fortunately, the gene content of B. pertussis remains highly conserved (10, 33, 40) and exhibits only slow genome reduction without any apparent gain of accessory genes (34, 41). The evaluation results presented here demonstrated that most of the B. pertussis genome, measured as coverage breadth at 20× depth, can be recovered by target enrichment with a bait library composed of DNA from only 10 diverse reference isolates. Further improvements may be possible by selectively removing repetitive IS elements, of which B. pertussis genomes typically encode >275 copies, from the RNA bait library. Other microbial pathogens with varied, open pangenomes may require careful reference selection or downstream analyses deliberately limited to conserved, core gene content.

CIWGS using target enrichment can produce data suitable for standard SNP or cgMLST/wgMLST analyses, as well as macrolide susceptibility prediction, combined with existing B. pertussis isolate sequence data for both surveillance and research. However, evidence of intra-patient sequence diversity (33) may require subtle modification of downstream bioinformatics applications optimized for pure, cultured isolates. Adjusting minimum frequency thresholds to only capture predominant SNPs, or simply masking heterogenous sites altogether, may help but would simultaneously reduce overall resolution. While the results presented here illustrate concordant phylogenetic clustering with sequence data from matched isolates, analyses including CIWGS data did feature fewer variable sites or alleles when comparing multiple CIWGS sequences. Due to lower DNA inputs from clinical specimens relative to cultured isolates, CIWGS library prep does not include size selection and necessitates additional PCR amplification steps, yielding smaller insert fragments that ultimately produce uneven sequencing coverage. The resolution of wgMLST appeared to suffer most, which could be attributed to poorer de novo assembly of CIWGS data. Whether that makes CIWGS data better suited for genomic surveillance rather than genomic epidemiology remains to be seen, but the threshold for accurate cluster delineation may be as low as ~2 alleles given the paucity of sequence diversity observed in B. pertussis (33, 40).

As expected, the RNA bait libraries also hybridized to and enriched highly conserved bacterial sequences (e.g., rRNA genes) as well as genes from closely related species of the genus Bordetella, consistent with current taxonomy (10, 34). Neither source of cross-reactive sequences diminishes the utility of the CIWGS or downstream characterization when using pertussis-positive specimens as inputs, particularly when using diagnostic assays capable of accurately distinguishing B. pertussis from B. holmesii or B. parapertussis (37, 42). Regardless, misidentification or even coinfection will be readily evident as clear aberrations from the expected low sequence diversity of true B. pertussis or detected using available metagenomic read classifiers (e.g., kraken2 and mash).

While this novel approach may facilitate better understanding of the epidemiology of pertussis and informing effecting prevention strategies, it is not without challenges despite the continued proliferation of pathogen genomics capacity among public health laboratories. The optimized target enrichment laboratory workflow described here results in higher costs per sample compared with typical sequencing protocols for cultured isolates due to additional reagents, staff time, and equipment requirements. Minimal staff training is expected for laboratorians engaged in routine WGS on Illumina instruments, which are increasingly common among US state public health laboratories. Rather, the most significant contributor to increased cost per sample is due to reduced multiplexing as CIWGS libraries require additional data output to achieve sufficient pathogen genome recovery, even after target enrichment. This cost discrepancy is expected to diminish as both sequencing costs and instrument output continue to improve. Additionally, quality control over RNA bait library synthesis will be key to routine application and may benefit from standardized, commercial preparation. Implementation faces other practical barriers such as timely access to residual diagnostic specimens, particularly from large commercial testing laboratories, and the variety of transport media or buffer solutions, nucleic acid extraction methods, and real-time PCR diagnostic assays currently used throughout the US public health testing network. It is also important to underscore the critical need for maintaining culture capacity at public health testing laboratories for B. pertussis antimicrobial resistance testing, monitoring acellular vaccine immunogen production, evaluating chromosome structural rearrangement (12, 43), and conducting animal challenge studies. However, the prospect of genomic and phylogenetic analyses with larger data sets benefiting from the additional cases captured by CIWGS opens the door to addressing new questions about pertussis resurgence and the ecology and evolution of its etiologic agent B. pertussis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Specimen and isolate sources

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) collection includes US B. pertussis isolates collected through surveillance and during outbreaks. Participating sites in the EPS program routinely submit both cultured isolates and residual NP specimens, typically swabs, from pertussis-positive cases to CDC for confirmation and characterization, including whole-genome sequencing (17). Twenty-nine surveillance specimens for CIWGS evaluation were selected that met diagnostic input criteria and had matched isolates for comparison. Description of selected specimens are included in Table S7.

Spiked specimen preparation

Mock clinical samples were prepared by mixing commercial, purified Homo sapiens DNA (Promega, Madison, WI) with a microbial community standard (Zymo Research, Irvine, CA) and then spiking purified B. pertussis isolate DNA from either E476 (CP010964) or K222 (CP114536) at varied ratios by mass (range = 0.000001–0.01) in duplicate. Separately, residual nasopharyngeal specimens from a previous study (16), which were first confirmed negative for pertussis by diagnostic PCR (42), were pooled and 200-μL aliquots were spiked with a serial dilution of B. pertussis J865 (CP033408) cells (range = 0.1–10,000) in triplicate.

RNA bait library construction

A selection of 10 B. pertussis isolates, including two vaccine references and eight US predominant strains (Table S1), was used to generate a shotgun DNA template library for subsequent transcription to whole-genome RNA baits. Equal mass (1 μg) of genomic DNA from each of these 10 isolates was pooled to a total volume of 55 μL and then sheared with a Covaris M220 ultrasonicator (Covaris Woburn, MA) using a microTUBE-50 tube and settings: peak power = 75.0 W, duty factor = 10.0%, cycles per burst = 200, and treatment time = 40 s. The DNA pool was then prepared into a whole-genome shotgun library using the NEB Ultra Library Prep kit (New England Biolabs; Ipswich, MA). Instead of the standard Illumina library prep adaptor, custom designed Y-type adaptors were ligated to both ends of the DNA fragments (adaptor sequences: 5′—CGCTCAGCGGCCGCAGCACTTGAGAGAGAGAGATxT—3′, 5′-pATCTCTCTCTCTCAACCTCCTCCTCCGTTGTTG---3′). After cleanup and size selection (300–500 bp) using AMPure XP beads (Beckman Coulter, Indianapolis, IN), the ligation products were amplified by eight cycles of PCR on an S1000 thermocycler (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) using Q5 High-Fidelity PCR master mix with HF buffer (NEB Ipswich, MA) and PCR primers containing the T7 promoter sequence (forward: 5′-GGATTCTAATACGACTCACTATACGCTCAGCGGCCGCAGCAC-3′, reverse: 5′-GGATTCTAATACGACTCACTATACAACAACGGAGGAGGAGG-3′) (adaptor and primers were synthesized in the CDC biotech core facility, Atlanta, GA). Initial denaturation was performed for 30 s at 98°C, followed by cycles for 10 s at 98°C, 30 s at 55°C, and 60 s at 68°C. The MEGAscript T7 Transcription Kit plus Bio-11-UTP (Invitrogen, Waltham MA) were used to produce the biotinylated RNA baits according to the manufacturer. The resulting RNA library was purified by using RNAClean XP beads (Beckman Coulter, Indianapolis, IN). The final quality and quantity were checked using a 2200 TapeStation with RNA Screen tapes (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA).

DNA extraction, library preparation, bait hybridization, and sequencing

Isolates were cultured on Regan-Lowe agar without cephalexin for 72 h at 37°C. Genomic DNA extraction from isolates was performed using the Gentra Puregene Yeast/Bacteria Kit (Qiagen; Valencia, CA) with slight modification (44). Briefly, 2 aliquots of approximately 1 × 109 bacterial cells were harvested and resuspended in 500 μL of 0.85% sterile saline and then pelleted by centrifugation for 1 min at 16,000 × g. Recovered genomic DNA was resuspended in 100 μL of DNA Hydration Solution. Aliquots were quantified using a NanoDrop 2000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc.; Wilmington, DE). Genomic DNA extraction from clinical or mock specimens using the MagNA Pure platform (Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN) following the method descripted in references (36). Indexed Illumina sequencing libraries were constructed using the NEB Ultra Library Prep kit (New England Biolabs; Ipswich, MA).

Hybridization selection for CIWGS was conducted at 67.5°C for 24 h by incubating 0.5–1 μg of barcoded DNA libraries, 1 μg human DNA (Promega, Madison, WI), 5 μg sheared salmon sperm DNA (Promega, Madison, WI), 500 ng of RNA bait, and 25 μL Amersham Rapid-hyb Buffer (GE Healthcare) in a final volume of 50 µL using thermocycler (28, 32). After hybridization, captured DNA libraries were pulled down using Streptavidin Magnetic Beads (NEB). Beads were washed once at room temperature for 15 minutes with 0.5 mL 1 × SSC/0.1% SDS, followed by three 10-minute washes at 67.5°C with 0.5 mL pre-warmed 0.1 × SSC/.1% SDS, resuspending the beads once at each washing step. Hybridized DNA library fragments were eluted with 50 µL 0.1 M NaOH. After 10 minutes at room temperature, the beads were pulled down, the supernatant was transferred to a tube containing 70 µL of 1 M Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, and the neutralized DNA was desalted and concentrated by using a AMPure XP beads cleanup step. An additional PCR amplification was conducted using the corresponding barcode primer and universal primer with no more than 14 cycles. The final enrichened DNA libraries were sequenced using a MiSeq with the reagent v3, 500 cycle kit (Illumina; San Diego, CA).

Bioinformatic read filtering

CIWGS reads were filtered to remove human sequence contamination by subtractive mapping to reference assembly GRCh38 using bowtie2 (v2.2.9) with parameter preset “--local,” samtools (v1.3.1), and BEDTools (v2.26.0). In a similar manner, reads containing B. pertussis sequences were subsequently captured by mapping to reference C734 (CP013078). Summary statistics of target enrichment were calculated from the mapping output files.

Sequence characterization and phylogenetics

The sequencing accuracy of filtered CIWGS reads relative to matched isolates was determined by mapping and SNP calling with snippy (v4.3.8) (https://github.com/tseemann/snippy) using the reference C734 (CP013078) and PacBio reference-quality assembly of isolate genomes if available, while masking all known IS elements. Maximum likelihood phylogenetic reconstructions were estimated from separate core SNP alignments of CIWGS and isolate data each, as well as combined, using RAxML (v8.1.16) (45). Tree visualization and annotation were performed with iToL (v6) (46). Tree structures calculated from CIWGS and isolate data individually were compared using phylo.io (47). Allele typing by whole-genome MLST was performed with both CIWGS and isolate sequence data using BioNumerics (v7.6.3) as described previously (33).

ANI between B. pertussis C734 and B. parapertussis J859 (CP043061) or B. holmesii C690 (CP020653) was calculated using the enveomics collection (47). Sequence similarly of all annotated protein coding genes in B. parapertussis J859 and B. holmesii C690 was evaluated by BLASTNn alignment (-qcov_hsp_perc 50) to the B. pertussis C734 reference.

Performance characteristics

Method accuracy was evaluated by comparing read data from spiked specimens, both mock mixtures and pooled pertussis-negative NP aspirates, to previous reference-quality genome assemblies from the added B. pertussis isolate. TP was defined as CIWGS data yielding ≥ 85% coverage breadth at 20× depth and ≤2 SNPs relative to the reference genome, based on reported diversity among replicate B. pertussis isolates recovered during diagnostic culture (33). TN was defined as either pooled, unspiked pertussis-negative NP aspirates or unenriched pertussis-positive surveillance specimens. Results were used in performance calculations:

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Pam Cassiday, Tami Skoff, and Matthew Cole (CDC) and The Enhanced Pertussis Surveillance/Emerging Infections Program.

This work was made possible through support from CDC’s Advanced Molecular Detection (AMD) program.

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Use of trade names and commercial sources is for identification only and does not imply endorsement by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the Public Health Service, or the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Contributor Information

Michael R. Weigand, Email: mweigand@cdc.gov.

John P. Dekker, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, Bethesda, Maryland, USA

DATA AVAILABILITY

CIWGS shotgun sequencing reads without human sequence contamination are available from the NCBI Sequence Read Archive under BioProject accession number PRJNA922069 and isolate sequences are available under PRNJA279196. Source code for scripts to further filter CIWGS sequencing read data is available at https://github.com/CDCgov/bpertussis-ciwgs/.https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/PRJNA279196

ETHICS APPROVAL

This activity was reviewed by CDC, deemed not research, and was conducted consistent with applicable federal law and CDC policy. See 45 C.F.R. part 46, 21 C.F.R. part 56; 42 U.S.C. §241(d); 5 U.S.C. §552a; 44 U.S.C. §3501 et seq.

SUPPLEMENTAL MATERIAL

The following material is available online at https://doi.org/10.1128/jcm.01653-23.

Fig. S1 to S7.

Tables S1 to S8.

ASM does not own the copyrights to Supplemental Material that may be linked to, or accessed through, an article. The authors have granted ASM a non-exclusive, world-wide license to publish the Supplemental Material files. Please contact the corresponding author directly for reuse.

REFERENCES

- 1. Clark TA. 2014. Changing pertussis epidemiology: everything old is new again. J Infect Dis 209:978–981. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiu001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Burdin N, Handy LK, Plotkin SA. 2017. What is wrong with pertussis vaccine immunity? Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 9:a029454. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a029454 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Warfel JM, Edwards KM. 2015. Pertussis vaccines and the challenge of inducing durable immunity. Curr Opin Immunol 35:48–54. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2015.05.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bart MJ, Harris SR, Advani A, Arakawa Y, Bottero D, Bouchez V, Cassiday PK, Chiang C-S, Dalby T, Fry NK, et al. 2014. Global population structure and evolution of Bordetella pertussis and their relationship with vaccination. mBio 5:e01074. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01074-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lefrancq N, Bouchez V, Fernandes N, Barkoff A-M, Bosch T, Dalby T, Åkerlund T, Darenberg J, Fabianova K, Vestrheim DF, et al. 2022. Global spatial dynamics and vaccine-induced fitness changes of Bordetella pertussis. Sci Transl Med 14:eabn3253. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.abn3253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ma L, Caulfield A, Dewan KK, Harvill ET. 2021. Pertactin-deficient Bordetella pertussis, vaccine-driven evolution, and reemergence of pertussis. Emerg Infect Dis 27:1561–1566. doi: 10.3201/eid2706.203850 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Belcher T, Dubois V, Rivera-Millot A, Locht C, Jacob-Dubuisson F. 2021. Pathogenicity and virulence of Bordetella pertussis and its adaptation to its strictly human host. Virulence 12:2608–2632. doi: 10.1080/21505594.2021.1980987 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Guiso N, Soubeyrand B, Macina D. 2022. Can vaccines control bacterial virulence and pathogenicity? Bordetella pertussis: the advantage of fitness over virulence. Evol Med Public Health 10:363–370. doi: 10.1093/emph/eoac028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Armstrong GL, MacCannell DR, Taylor J, Carleton HA, Neuhaus EB, Bradbury RS, Posey JE, Gwinn M. 2019. Pathogen genomics in public health. N Engl J Med 381:2569–2580. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsr1813907 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bridel S, Bouchez V, Brancotte B, Hauck S, Armatys N, Landier A, Mühle E, Guillot S, Toubiana J, Maiden MCJ, Jolley KA, Brisse S. 2022. A comprehensive resource for Bordetella genomic epidemiology and biodiversity studies. Nat Commun 13:3807. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-31517-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Weigand MR, Peng Y, Batra D, Burroughs M, Davis JK, Knipe K, Loparev VN, Johnson T, Juieng P, Rowe LA, Sheth M, Tang K, Unoarumhi Y, Williams MM, Tondella ML. 2019. Conserved patterns of symmetric inversion in the genome evolution of Bordetella respiratory pathogens. mSystems 4:e00702-19. doi: 10.1128/mSystems.00702-19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Weigand MR, Peng Y, Loparev V, Batra D, Bowden KE, Burroughs M, Cassiday PK, Davis JK, Johnson T, Juieng P, Knipe K, Mathis MH, Pruitt AM, Rowe L, Sheth M, Tondella ML, Williams MM. 2017. The history of Bordetella pertussis genome evolution includes structural rearrangement. J Bacteriol 199:e00806-16. doi: 10.1128/JB.00806-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Xu Z, Wang Z, Luan Y, Li Y, Liu X, Peng X, Octavia S, Payne M, Lan R. 2019. Genomic epidemiology of erythromycin-resistant Bordetella pertussis in China. Emerg Microbes Infect 8:461–470. doi: 10.1080/22221751.2019.1587315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Faulkner AE, Skoff TH, Tondella ML, Cohn A, Clark TA, Martin SW. 2016. Trends in pertussis diagnostic testing in the United States, 1990 to 2012. Pediatr Infect Dis J 35:39–44. doi: 10.1097/INF.0000000000000921 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Marder EP, Cieslak PR, Cronquist AB, Dunn J, Lathrop S, Rabatsky-Ehr T, Ryan P, Smith K, Tobin-D’Angelo M, Vugia DJ, Zansky S, Holt KG, Wolpert BJ, Lynch M, Tauxe R, Geissler AL. 2017. Incidence and trends of infections with pathogens transmitted commonly through food and the effect of increasing use of culture-independent diagnostic tests on surveillance—foodborne diseases active surveillance network, 10 U.S. Sites, 2013–2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 66:397–403. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6615a1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lee AD, Cassiday PK, Pawloski LC, Tatti KM, Martin MD, Briere EC, Tondella ML, Martin SW, Clinical Validation Study Group . 2018. Clinical evaluation and validation of laboratory methods for the diagnosis of Bordetella pertussis infection: culture, polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and anti-pertussis toxin IgG serology (IgG-PT). PLoS One 13:e0195979. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0195979 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Skoff TH, Baumbach J, Cieslak PR. 2015. Tracking pertussis and evaluating control measures through enhanced pertussis surveillance, emerging infections program, United States. Emerg Infect Dis 21:1568–1573. doi: 10.3201/eid2109.150023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Huang AD, Luo C, Pena-Gonzalez A, Weigand MR, Tarr CL, Konstantinidis KT. 2017. Metagenomics of two severe foodborne outbreaks provides diagnostic signatures and signs of coinfection not attainable by traditional methods. Appl Environ Microbiol 83:e02577-16. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02577-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Chen LX, Anantharaman K, Shaiber A, Eren AM, Banfield JF. 2020. Accurate and complete genomes from metagenomes. Genome Res 30:315–333. doi: 10.1101/gr.258640.119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Meziti A, Rodriguez-R LM, Hatt JK, Peña-Gonzalez A, Levy K, Konstantinidis KT. 2021. The reliability of metagenome-assembled genomes (MAGs) in representing natural populations: insights from comparing MAGs against isolate genomes derived from the same fecal sample. Appl Environ Microbiol 87:e02593-20. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02593-20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Govender KN, Street TL, Sanderson ND, Eyre DW. 2021. Metagenomic sequencing as a pathogen-agnostic clinical diagnostic tool for infectious diseases: a systematic review and meta-analysis of diagnostic test accuracy studies. J Clin Microbiol 59:e0291620. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02916-20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Simner PJ, Miller S, Carroll KC. 2018. Understanding the promises and hurdles of metagenomic next-generation sequencing as a diagnostic tool for infectious diseases. Clin Infect Dis 66:778–788. doi: 10.1093/cid/cix881 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Fong W, Rockett R, Timms V, Sintchenko V. 2020. Optimization of sample preparation for culture-independent sequencing of Bordetella pertussis. Microb Genom 6:e000332. doi: 10.1099/mgen.0.000332 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Taylor-Brown A, Madden D, Polkinghorne A. 2018. Culture-independent approaches to chlamydial genomics. Microb Genom 4:e000145. doi: 10.1099/mgen.0.000145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Cowell AN, Loy DE, Sundararaman SA, Valdivia H, Fisch K, Lescano AG, Baldeviano GC, Durand S, Gerbasi V, Sutherland CJ, Nolder D, Vinetz JM, Hahn BH, Winzeler EA. 2017. Selective whole-genome amplification is a robust method that enables scalable whole-genome sequencing of Plasmodium vivax from unprocessed clinical samples. mBio 8:e02257-16. doi: 10.1128/mBio.02257-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Leichty AR, Brisson D. 2014. Selective whole genome amplification for resequencing target microbial species from complex natural samples. Genetics 198:473–481. doi: 10.1534/genetics.114.165498 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Thurlow CM, Joseph SJ, Ganova-Raeva L, Katz SS, Pereira L, Chen C, Debra A, Vilfort K, Workowski K, Cohen SE, Reno H, Sun Y, Burroughs M, Sheth M, Chi KH, Danavall D, Philip SS, Cao W, Kersh EN, Pillay A. 2022. Selective whole-genome amplification as a tool to enrich specimens with low Treponema pallidum Genomic DNA copies for whole-genome sequencing. mSphere 7:e0000922. doi: 10.1128/msphere.00009-22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Gnirke A, Melnikov A, Maguire J, Rogov P, LeProust EM, Brockman W, Fennell T, Giannoukos G, Fisher S, Russ C, Gabriel S, Jaffe DB, Lander ES, Nusbaum C. 2009. Solution hybrid selection with ultra-long oligonucleotides for massively parallel targeted sequencing. Nat Biotechnol 27:182–189. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1523 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Bowden KE, Joseph SJ, Cartee JC, Ziklo N, Danavall D, Raphael BH, Read TD, Dean D. 2021. Whole-genome enrichment and sequencing of Chlamydia trachomatis directly from patient clinical vaginal and rectal swabs. mSphere 6:e01302-20. doi: 10.1128/mSphere.01302-20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Itsko M, Retchless AC, Joseph SJ, Norris Turner A, Bazan JA, Sadji AY, Ouédraogo-Traoré R, Wang X. 2020. Full molecular typing of Neisseria meningitidis directly from clinical specimens for outbreak investigation. J Clin Microbiol 58:e01780-20. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01780-20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Itsko M, Topaz N, Ousmane-Traoré S, Popoola M, Ouedraogo R, Gamougam K, Sadji AY, Abdul-Karim A, Lascols C, Wang X. 2022. Enhancing meningococcal genomic surveillance in the meningitis belt using high-resolution culture-free whole-genome sequencing. J Infect Dis 226:729–737. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiac104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Melnikov A, Galinsky K, Rogov P, Fennell T, Van Tyne D, Russ C, Daniels R, Barnes KG, Bochicchio J, Ndiaye D, Sene PD, Wirth DF, Nusbaum C, Volkman SK, Birren BW, Gnirke A, Neafsey DE. 2011. Hybrid selection for sequencing pathogen genomes from clinical samples. Genome Biol 12:R73. doi: 10.1186/gb-2011-12-8-r73 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Weigand MR, Peng Y, Pouseele H, Kania D, Bowden KE, Williams MM, Tondella ML. 2021. Genomic surveillance and improved molecular typing of Bordetella pertussis using wgMLST. J Clin Microbiol 59:e02726-20. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02726-20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Linz B, Ivanov YV, Preston A, Brinkac L, Parkhill J, Kim M, Harris SR, Goodfield LL, Fry NK, Gorringe AR, Nicholson TL, Register KB, Losada L, Harvill ET. 2016. Acquisition and loss of virulence-associated factors during genome evolution and speciation in three clades of Bordetella species. BMC Genomics 17:767. doi: 10.1186/s12864-016-3112-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Wang Z, Han R, Liu Y, Du Q, Liu J, Ma C, Li H, He Q, Yan Y. 2015. Direct detection of erythromycin-resistant Bordetella pertussis in clinical specimens by PCR. J Clin Microbiol 53:3418–3422. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01499-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Burgos-Rivera B, Lee AD, Bowden KE, Faulkner AE, Seaton BL, Lembke BD, Cartwright CP, Martin SW, Tondella ML. 2015. Evaluation of level of agreement in Bordetella species identification in three U.S. laboratories during a period of increased pertussis. J Clin Microbiol 53:1842–1847. doi: 10.1128/JCM.03567-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Williams MM, Taylor TH, Warshauer DM, Martin MD, Valley AM, Tondella ML. 2015. Harmonization of Bordetella pertussis real-time PCR diagnostics in the United States in 2012. J Clin Microbiol 53:118–123. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02368-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Nunes MC, Soofie N, Downs S, Tebeila N, Mudau A, de Gouveia L, Madhi SA. 2016. Comparing the yield of nasopharyngeal swabs, nasal aspirates, and induced sputum for detection of Bordetella pertussis in hospitalized infants. Clin Infect Dis 63:S181–S186. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciw521 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Bowden KE, Williams MM, Cassiday PK, Milton A, Pawloski L, Harrison M, Martin SW, Meyer S, Qin X, DeBolt C, Tasslimi A, Syed N, Sorrell R, Tran M, Hiatt B, Tondella ML. 2014. Molecular epidemiology of the pertussis epidemic in Washington State in 2012. J Clin Microbiol 52:3549–3557. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01189-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Bouchez V, Guglielmini J, Dazas M, Landier A, Toubiana J, Guillot S, Criscuolo A, Brisse S. 2018. Genomic sequencing of Bordetella pertussis for epidemiology and global surveillance of whooping cough. Emerg Infect Dis 24:988–994. doi: 10.3201/eid2406.171464 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Lam C, Octavia S, Sintchenko V, Gilbert GL, Lan R. 2014. Investigating genome reduction of Bordetella pertussis using a multiplex PCR-based reverse line blot assay (mPCR/RLB). BMC Res Notes 7:727. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-7-727 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Tatti KM, Sparks KN, Boney KO, Tondella ML. 2011. Novel multitarget real-time PCR assay for rapid detection of Bordetella species in clinical specimens. J Clin Microbiol 49:4059–4066. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00601-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Stibitz S, Yang MS. 1999. Genomic plasticity in natural populations of Bordetella pertussis. J Bacteriol 181:5512–5515. doi: 10.1128/JB.181.17.5512-5515.1999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Bowden KE, Weigand MR, Peng Y, Cassiday PK, Sammons S, Knipe K, Rowe LA, Loparev V, Sheth M, Weening K, Tondella ML, Williams MM. 2016. Genome structural diversity among 31 Bordetella pertussis isolates from two recent U.S. mSphere 1:e00036-16. doi: 10.1128/mSphere.00036-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Stamatakis A. 2014. RAxML version 8: a tool for phylogenetic analysis and post-analysis of large phylogenies. Bioinformatics 30:1312–1313. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Letunic I, Bork P. 2021. Interactive tree of life (iTOL) v5: an online tool for phylogenetic tree display and annotation. Nucleic Acids Res 49:W293–W296. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkab301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Rodriguez-R LM, Konstantinidis KT. 2016. The enveomics collection: a toolbox for specialized analyses of microbial genomes and metagenomes. Peerj Preprints. doi: 10.7287/peerj.preprints.1900v1 [DOI]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Fig. S1 to S7.

Tables S1 to S8.

Data Availability Statement

CIWGS shotgun sequencing reads without human sequence contamination are available from the NCBI Sequence Read Archive under BioProject accession number PRJNA922069 and isolate sequences are available under PRNJA279196. Source code for scripts to further filter CIWGS sequencing read data is available at https://github.com/CDCgov/bpertussis-ciwgs/.https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/PRJNA279196