ABSTRACT

The goal of this study was to examine and address critical knowledge gaps and develop an understanding of both the positive and negative societal outcomes resulting from the public health measures associated with the COVID-19 pandemic in Nunavut and the interventions being undertaken to promote positive well-being. Data collection for this study included narrative, in-person interviews in Iqaluit, Rankin Inlet, Baker Lake, and Cambridge Bay between September 2022 and January 2023. A total of 70 participants were interviewed for this study. Community highlighted challenges, such as crowding and food insecurity, and concern for the collective wellbeing of the community. Strengths included financials supports, food sharing, and maintaining community connections over a distance. Recommendations included a focus on holistic health such as 1) public education and awareness about communicable disease, 2) financial supports, 3) housing, 4) access to healthcare, 5) focus on Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit, 6) mental-health and addiction supports, and 7) community spaces. Community members described both strengths and challenges they believe impacted their experiences and service delivery as well as recommendations for the future.

KEYWORDS: Inuit, Nunavut, COVID-19, Circumpolar, Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit, community-based participatory research, health system

Introduction

Nunavut is a territory in the Canadian Arctic that is often characterised by its vast geography of 2.2 million square kilometres and predominantly Inuit population of approximately 38,000 people [1]. With a distinctive set of circumstances that amplify the complexities of pandemic response and management, and the high prominence of Inuit cultural values and processes in policy and decision-making, the pandemic’s impact on essential services, frontline professionals, and community wellbeing required documentation and in-depth investigation. The purpose of this exploratory study was to capture the perspectives of essential workers and community members on the impacts of COVID-19 in Nunavut communities, focusing on both strengths and challenges, and recommendations for policy-makers.

Context

Pandemics are not new to the region and responses to epidemics of tuberculosis and influenza in the mid-20th century, remain in the living memory of many Nunavummiut1 [2,3]. On-going challenges with managing tuberculosis that persist to this day, as well as other respiratory illnesses, contributed to the development of several processes the equipped Nunavut with the knowledge and tools to respond appropriately [2,4,5]. For example, contract tracing and screening protocols, culturally-sensitive approaches, and community-based and collaborative, involving consultation and collaboration with Inuit organisations, were well-developed strategies that were embraced during the COVID-19 response [6].

COVID-19 entered Nunavut in November of 2020, almost 8 months into the declaration of the global pandemic [7]. This was credited to several public health measures, including an immediate ban on unnecessary travel (by air or sea) and mandatory 14-day isolation protocols for necessary travel into the territory which were instituted in March 2020. The full spectrum of interventions implemented in Nunavut are reported elsewhere [8].

The remoteness of Nunavut’s communities provided both advantages and disadvantages for the management of COVID-19 [9]. For example, remoteness of Nunavut’s 25 communities and the lack of inter-community road infrastructure provided opportunities to limit spread by limiting inter-community air travel. Disadvantages of Nunavut’s remote geography included an already limited healthcare system infrastructure and low staffing rates, as well as additional complex logistics for the disbursement of personal protective equipment and vaccines [10].

Public health response was grounded in Inuit values as well as experience managing on-going challenges with Tuberculosis in the territory [4,5,11] and previous communicable disease outbreaks [12].

Location and population demographics

Nunavut is a Canadian territory, formed in 1999 as a result of Canada’s Nunavut Act [13]. The population of Nunavut in the 2021 Canadian Census was 36,858 of whom 84% report Inuit identity and 53% report Inuktut languages as their primary language [1]. The median age of Nunavummiut is 26 and the average age is 28 years.

Implementation of public health measures for outbreak management

The territory initiated a lockdown period from March to June 2020. Restrictions were gradually eased after the territory remained free of COVID-19 cases. All travellers returning to Nunavut in March 2020 were required to isolate for 14-days [8]. A travel ban and mandatory 14-day quarantine were implemented for Nunavut on 24 March 2020. The first case was confirmed in Sanikiluaq, Nunavut on 6 November 2020, with a second case confirmed on November 8 [14]. By November 18, Nunavut had confirmed 26 cases, which contributed to the decision to implement a 14-day territory-wide lockdown [15]. On 20 December 2020, Nunavut’s first two deaths related to COVID-19 were reported and at 1 November 2022, a total of 10 deaths had been reported for the region [16].

Travellers who wished to enter Nunavut were required to provide a written request along with a traveller declaration form [8], which included essential workers, medical travel patients, and relief rotational staff. When vaccinations were introduced in January 2021, proof of vaccination was required to board aircraft [17]. The travel ban and limitations on travel continued until April 2022, and this intervention is credited by community members as being a significant factor in limiting the spread of COVID-19 in the territory at the time [10].

Method

Study design

This exploratory qualitative study followed a Piliriqatigiinniq study approach to explore a research question raised by community members: What impact is COVID-19 having in our Nunavut communities? The study used the Piliriqatigiinniq research framework [18], which privileges Inuit research and knowledge production constructs: Unikkaaqatigiinniq (storytelling), Inuuqatigiittiarniq (respect for all people), Pittiarniq (to be good or kind), Piliriqatigiiniq (working together for the common good), and Iqqaumaqatigiinniq (thinking deeply in ways that lead to understanding and/or innovation).

This study addressed key community research questions. The narratives and voices of Nunavummiut were essential to the story and words kept intact as much as possible following Unikkaaqatigiinniq. The analyses focused on understanding experiences, thinking deeply, and identifying solution-seeking pathways following Iqqaumaqatigiinniq and Piliriqatigiiniq. The study was implemented with compassion and kindness at the heart of the work following Pittiarniq and Inuuqatigiittiarniq processes.

Data collection and analysis

The approach included an iterative process for recruitment, sampling, data collection, and analysis. Individual face-to-face interviews were conducted to gather perspectives from individuals living in Iqaluit, Baker Lake, Rankin Inlet, Cambridge Bay, and Panniqtuuq, Nunavut between June and December 2022.

Purposive sampling strategy [19] allowed for a sample that included a wide range of characteristics such as age, family status, and women from varying educational backgrounds and shelters, which were representative of the variables of interest to communities with respect to the research question. Community members who informed the study were particularly concerned about the most vulnerable members of the communities, including women and children in shelters. Participants were recruited until the data reached saturation, or until new interviews no longer contributed to the themes identified in the analysis [20,21]. With participant permission, interviews were audio recorded with a digital recorder and transcribed verbatim. Interviews ranged between 30 and 90 minutes in length. Interviews were conducted by the research team (interviewers and interpreter as needed), using a semi-structured, 10- to 12-question guide, depending on whether the interviewee was an essential service provider and/or a community member. Interviews were conducted in English or Inuktitut, whichever was mos

Participants were asked to comment on the their experiences during COVID-19 lockdowns and travel bans, as well as during any periods of mobility since 2020. In particular, participants were asked to comment on how these events contributed to or changed their well-being, their daily lives, and their observations of others in the community.

Data were coded with NVivo (12th edition) software and analysed by the research team using a process of immersion and crystallisation [22]. Issues of rigour were addressed using established qualitative techniques, which included a thorough review of the literature, bracketing (a process of critical self-reflection to acknowledge and “bracket” preconceptions about the research topic) and researcher reflexivity, debriefing with colleagues and co-researchers, and member-checking by verifying data and analyses with others in the field [21,23].

In the presentation of findings, quotes have been anonymised to prevent identification across small and closely-knit communities. Respondents were identified by a unique identifier number to prevent any potential for identification.

Findings

In total, 70 interviews were conducted seeking community member perspectives. Forty-four (44) in Iqaluit, four (4) from Rankin Inlet, fourteen (14) from Cambridge Bay, and eight (8) from Baker Lake, representing a range of ages (from youth to Elders) and genders.

Results are presented under the themes of: 1) Community-identified Challenges and Inequities; 2) Access to Healthcare in Communities; 3) Caregiving Pathways and Protective Factors; and 4) Community Recommendations and Reflections – Through the lens of Inuit holistic thinking.

Community-identified challenges and inequities

Trauma, addictions, substance use

One of the many challenges participants discussed was the presence of substance use and addictions in their community. There’s always a lot of alcoholics up there… they’re always drunk. They don’t know what the hell they’re doing. Even with COVID they still drink. They still went out. It looks like everything with the pandemic just doubled their addiction. Community member 8

Participants shared that either they struggled with substance use in their own life or witnessed a loved one struggling with substance use.

Negativity and anger. I never realized it until things slowed down and talking with my family and friends, it really affected the community. Some people were suicidal, were drinking too much, or always angry. It didn’t hit my family that way but seeing it in the community did have a big impact on the community. Community member 13

Participants noted that substance use and addictions affected the whole community.

And it spread pretty quick for the partiers and the gamblers. They are the ones, the main reason why we had so many people with COVID. It was the people who had addiction and needed help with their mental health. You don’t care about COVID when you are caught in your own addictions. They need help. We need more mental-health workers, especially during COVID. Community member 17

Although these challenges already existed, COVID-19 exacerbated the challenges associated with substance use and decreased safety and well-being for the community.

Mental health

Participants disclosed that individuals struggling with mental-health issues were less likely to follow lockdown protocols. For example, participants discussed how some individuals who were struggling with their mental health would make statements that COVID-19 was a hoax, or they did not care.

We need more mental-health assistance. It would be better if there were more Inuk, mental-health workers, because people would trust them. Getting different mental-health workers, it makes you not want to go there and see them at all and talk to them. Like opening up to a different person every time. I needed mental-health support more than COVID-19 help. -Community member 2

In those instances, those individuals would continue to party and/or to gamble. Participants expressed frustration with the chronic lack of support for those struggling with their mental health, which was exacerbated by the pandemic.

I’m a residential school survivor and I needed the mental-health support, and it was so hard filling out forms and getting access. I needed mental health help. -Community member 4

The disregard for public health restrictions in this group was perceived as threatening to community well-being and safety, but ultimately attributed to the lack of mental health supports for those who were struggling with bigger underlying issues and traumas.

Overcrowding

The chronic shortage of housing and overcrowding in Nunavut was a major themes identified by participants. These were discussed in terms of the practicalities of trying to stay safe. Community members stated this was almost impossible when they live with many other family members and children.

Yeah, we were 11. It was very hard. At that time, we didn’t have much food because there were so many of us. We can get sick so easily. Community member 3

That’s how I saw it, the overcrowded houses are the ones that spread the COVID very fast. If we didn’t have overcrowded houses, I think it would’ve been a little less COVID, because I don’t know. I just saw it as the ones who had overcrowded houses were the ones that got the COVID. We have 13 people in 4 bedrooms. Community member 5

Overcrowding was identified as a significant hindrance to social distancing and, in many cases, was something that got increasingly difficult due to the pandemic.

Food insecurity

Many community members discussed how food insecurity impacted their day to day lives especially when COVID-19 hit the communities. Many were out of work and could not afford to buy groceries or hunt and witnessed their family starving.

Food wise, not working. And I don’t like watching my little siblings go hungry. And I couldn’t do anything about it, but the only thing that helped us was that Nunavut food hamper thing -Community member 4

I very heavily relied on the food bank, but even they could not do much. It was really hard not having a job and not having money to buy food. The pandemic made it so much harder. -Community member 7

At that time, we would, most of us couldn’t buy groceries because of the pandemic. Yeah. Most of us were working in a public place. It was really hard financially. -Community member 19

One of the primary reasons that participants noted the importance and strength of the food hamper programmes were during the pandemic in Nunavut was the high rate of underlying food insecurity. Participants strongly expressed how they needed food-related resources. Food insecurity rose in households due to limited resources without financial means exacerbated by overcrowded homes.

Lack of supports for children and youth

Participants noted how it became increasingly difficult keeping young ones inside the house. They also struggled to describe the pandemic to their kids and their anxieties increased.

I have a nine-year-old daughter who lives with me. It was hard teaching her and explaining things to her about the pandemic. It was hard trying to wear many hats with school. I wish we had more educational supports like teachers or something. -Community member 24

Keeping children at home for school was also very difficult because this came with increased roles to play that were difficult to support. Participants discussed how they would have appreciated supports for teaching their children about COVID-19 and what this meant for families.

Had to isolate for two weeks with my whole family. And that was very, very hard. My kids like to go out, or my kids like to stay out. And that was the very, very hardest for me to keep them in. Especially because my one kid has special needs. I wish I knew what to do or had some sort of support-someone or something to go to. -Community member 16

Parents would also have appreciated more educational supports for their children at home when they struggled with homework.

Financial challenges

The majority of participants discussed financial hardship and job loss during their interviews. It was a major theme. Many community members described living pay cheque to pay cheque and described the pandemic as the catalyst for their financial struggles.\ Moneywise, we had no money. And I got kind of behind on bills. So, I’m slowly getting back to paying my bills now. -Community member 13

Very hard. I’m struggling. I lost my home, and I lived with my daughters. Life is harder now than it was in a past. It was so much easier before. Today, you have to worry about power bills, garbage bills, everything. We never paid for that before. Now, it’s so different. Hard, especially when you don’t have your own place and no job. I couldn’t pay for anything. -Community member 22

And I’m a single father too, so it’s… I have three kids and a grandson, too, so kind of gets hard for me to try not to be sick and go to work and try and find work. - Community member 12

Participants noted they lost their permanent and casual jobs and they struggled to pay bills and buy food for their family.

Access to healthcare in Nunavut - community perspectives

Community members acknowledged the ways in which healthcare professionals were trying very hard to work with the resources available. Most community members noted it was more difficult to access care than pre-pandemic and found it difficult to contact the community health centres.

Community members noted that health centres switched to only having emergency visits. This, coupled with having a hard time contacting the health centres, was a consistent challenge for most community members.

When I got sick with my sore throat, I tried to call the health centre, but they only did emergencies. A week later I finally was seen and it was bad strep throat- so, for a week, I had no pills, no nothing. -Community member 6

You aren’t really able to do walk in anymore, you have to call ahead and it was hard to call them. I would call for days. I know that some of the nurses were working a lot of overtime when the COVID was pretty bad up here. -Community member 7

If someone’s got high fever, or if they hurt themselves somehow by accident - is that an emergency? It’s not clear. I wouldn’t know who to go to. -Community member 24

Community members knew this was due to the limited healthcare staff in their community, however, they still felt that access to care was limited and because COVID-19 took precedence, other wellness programmes and clinical visits took a back seat. Community members still needed these other important services.

We need more healthcare staff. We need more nurses. We need more doctors. We need more access to healthcare, all the nurses. I know we had, just recently, we had a nursing shortage, so the health centre was closed for emergencies only. -Community member 18

Community members discussed challenges with accessing the health system in Inuktut (Inuit languages). Many individuals in Nunavut communities are unilingual in Inuktitut or Inuinnaqtun and reported the ways in which.

It was hard talking to the nurse ‘cause some of them had no translator and some people don’t know how to talk qablunaatitut [English]. - Community member 17

It was difficult to not able to communicate with a healthcare professional due to the lack of interpreter/translator services. Community members indicated they would have benefited from interpretation services while visiting and seeking care.

Caregiving pathways and protective factors

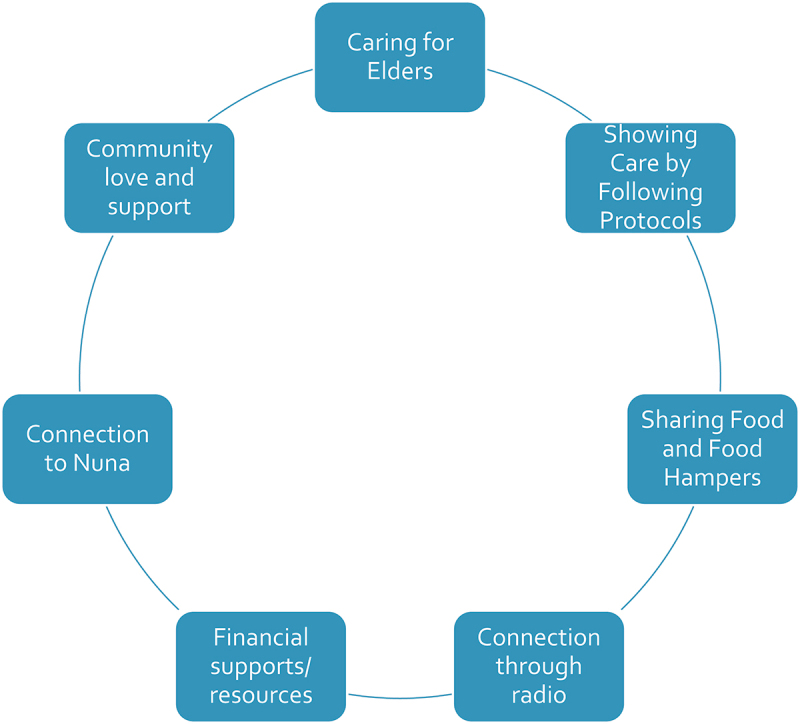

In this exploratory study, numerous caregiving pathways were identified including: community love and support; connection to Nuna (the land); access to financial support; connection through community radio; the delivery of food hampers; Following public health protocols, and care of Elders (Figure 1)

Figure 1.

Caregiving pathways identified by community members.

Community love and support

This topic was identified by the majority of participants. They described an exceptional volume of support, love, and strength shared among community members. Community members supported each other by sharing food and supplies.

At that time, we didn’t have much food, but somehow, we started helping, all of us started helping each other to figure out how we can get food. - Community member 9

Community members discussed the important role of family and friends to help individuals who were struggling, out of work, isolating, and in need of additional supports.

It made it harder because my dad didn’t get paid as much and it was very hard for us, because we didn’t know where we would get the money from. We didn’t know how we’d eat, and it was some of our family members that kind of helped us a lot with our food, and that made it a lot easier, getting some help from people, the food and things like that. Or people going hunting and then things like that. That was easier for us. - Community member 10

This was a significant protective factor for community well-being and community members indicated that the support provided by loved ones, extended family, and friends was essential.

At least you could call someone if you needed help; if you were feeling sick. A few times I was feeling pretty sick, so I had to ask for help, to get the Hamlet to go to the store for us. That was so helpful. - Community member 18

Care for elders

Participants expressed a love and concern for Elders who were vulnerable to COVID-19 transmission due to age and/or underlying health issues.

For me anyways, because I love my people, I love helping my Elders. I love helping my children and everything. I used to help go cleaning and all that. - Community member 14

Community members described feeling concern and worry for their Elders. They described a personal need to make a concerted effort to look after them because Elders have given so much of their lives and knowledge to the well-being of the community.

Following public health protocols

Participants discussed the collective need to follow public health restriction protocols for the benefit of all in the community. With the exception of a handful of individuals who did not, or would not, follow the restrictions, the majority of community members indicated that they followed protocols, stayed at home, wore their masks, kept social distancing to protect everyone else.

I know I noticed a lot of people were listening, not going out, telling their kids to wash their hands. Everything we were telling our kids, that most of the people stayed home and tried to do what they were told to do. We wanted to keep our communities healthy. - Community member 24

Participants described being motivated to follow the restrictions, which were at times difficult, because of their love and care for others. Community members felt they had to work together to get through COVID-19 and community cohesiveness was a driving force in moving forward for many respondents.

When it first started, people stayed away from each other, they would isolate at home. They made sure they didn’t get together. Even gathering stopped for two years, until recently. We had to do it to keep everyone safe. - Community member 22

Food hampers

Food hampers were one of the most significant methods of support mentioned by participants. The hampers, which were distributed by hamlets and Inuit organisations, were a safety net, protecting individuals and families from food insecurity.

We started getting help from [territorial Inuit organization]. They gave out food hampers. Also, whoever caught COVID, they got an isolation kit. That was very helpful [which included personal protective equipment and food]. - Community member 5

The [Nunavut] government had food hampers, I heard, and that really helped. It was it good food, good supplies that they put in there. Everything that we needed. Cleaning supplies, food, shampoo. All the necessities that we needed. - Community member 16

Many community members shared how they struggled during the lockdowns and isolation and noted the food hampers were not only helpful but, in many cases, the only food some families could access.

Maintaining relationships and connections through community radio

Communities in Nunavut have limited access to internet but are widely connected through territorial and local radio programming. Radio provided access to territory-wide news shows and updates from the Chief Public Health Officer, as well as local call-in shows and music request shows at the community level. Participants in this study were grateful for the ability to connect to people in both their own communities and in other communities through radio.

We usually get that [socializing by] gathering, but it’s different now. It’s a good thing we still do it, because we do it through radio. We do phone calls. It’s still fun. We get to hear other people’s voices. - Community member 3

Other radio-based activities included bingo nights, Inuktitut storytelling, local and regional updates on COVID-19, and group prayer.

They do radio bingos, for each household gets a bingo card and you got chance to win prizes and that’s what was good. - Community member 9

Access to financial supports

Other financial supports that were deemed helpful to participants included income support (administered through Dept. of Family Services) and the Canada Emergency Response Benefit (CERB). Community members noted that these financial support programmes helped to alleviate extraordinary financial stress during COVID-19.

Connection to Nuna

Many community members felt access to the land and participating in land-based activities increased their morale during the lockdowns and isolation.

We grew so much as a family. My kids got along for the first time in a really long time. It was always fight, fight, fight, fight, fight. But during our isolation for a few months, it was so nice to see my kids working together. It was so sweet. - Community member 12

Participants who had access to equipment went hunting, isolated on the land, and went to cabins for an extended period of time during lockdowns.

The land is where we all went to calm ourselves down, it was very important for us to go back to our ways and culture and find peace with that. It was the best thing. -Community member 14

Inuit organisations also provided gas vouchers to help individuals and families get out on the land (or water) and social distance. This was a protective factor that was noted by communities. It’s an integral part of Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit that rose to the surface during the pandemic in Nunavut.

We have always relied on the land and this pandemic just made us more aware. When you go on the land you forget that there is a whole other world in the city. It makes you strong and resilient. - Community member 17

Community members described how their bond with the land was even more strong during COVID-19, when people were isolating, and normal day-to-day life was paused.

It was okay for a few months, and then the next month I had time off and was like, okay, I need to go camping, I need to settle down, we need to go isolate out on the land. We needed to be ourselves. It was good for my family; everyone learned to get along. -Community member 5

Well, a lot of people went out on the land. A lot of people self-isolated out on the land for a while and a lot of people just didn’t go out, period. A lot of people were terrified and they just stayed at home as much as they could. -Community member 11

Community food sharing

Food sharing is an integral part of Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit. Food sharing and access to country food was a major theme discussed by the participants.

Since this COVID thing went down and you know, a lot of people used to share country food and everything, but since this COVID thing started, it really… I’m struggling today, because I usually get a lot of help from people, a group, bringing us traditional food and that, but since this COVID thing, it’s so hard, because I lost a lot of weight since this COVID thing started. And I’m starving for this traditional food and everything. It’s so harsh, because especially people that are low income, like myself, I’m a low-income mother, I didn’t come with my family and you don’t have here… like skidoos and that to go on the land like these other people, and it’s so hard on us people that’s low on income and don’t have, to get all the traditional food when we need it. Like for myself, I’m just finally healing after all that, because you know, I’m supposed to start eating my traditional food, but I can’t. -Community member 5

Most community respondents were happy to share their freshly caught caribou or fish with other loved ones.

Two months ago, I took out young teenagers. I was hunting… how to skin caribou, how to cook your caribou, how to prepare the meat and all. So that way, all that meat won’t go to waste. And teach them how to skin at the same time, too. And what meat needs to be brought home and what meat needs to be left back. But we tried to bring all of it back. -Community member 2

There some people that still share their catch. That’s what we actually do over here. When we catch our caribou or fish, we give out to the community. -Community member 13

We helped out each other, we had to, I couldn’t get through without my community helping us out. People would drop food for us at our door. We pulled together. -Community member 9

Even with strong food-sharing practices, some respondents highlighted that they still had difficulty accessing country foods due to a lack of social support, social networks, or connections to harvesters.

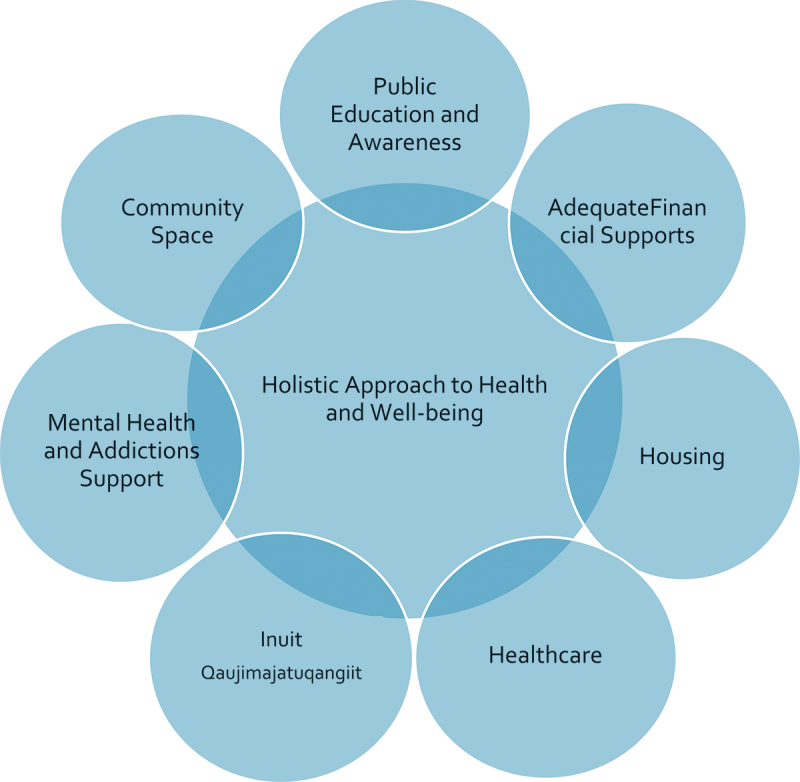

Community recommendations and reflections – through the lens of Inuit holistic thinking

A holistic approach to supporting well-being and health was a strong recommendation from participants. Many pre-existing challenges in Nunavut were exacerbated during COVID-19, and community members recommended an approach focused on overall health and wellness as a fundamental framework for future decision-making and emergency response. Participants noted the importance of: Community Spaces; Public Education and Awareness; Adequate financial supports; Housing; Healthcare; Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit (Inuit knowledge and practices); and Support for Mental Health and Addictions (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Community recommendations and reflections on a holistic approach to decision-making and emergency Response.

Public health and education

Education and awareness about communicable illness, such as COVID-19 was discussed by participants as being essential to emergency response. Community members felt that knowledge was the best defence against hesitancy and misinformation. They noted how teachings can be grounded in an Inuit pedagogical perspective, for example, by including Elders and Inuit-centred ways of knowing. Other examples included radio programmes with Elders sharing stories of how Inuit in the past had dealt with diseases brought to them by settlers, but also incorporating Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit in protocol measures and programmes.

Community space

Community members discussed the need for more recreational facilities, larger building complexes, and more community centres. Participants discussed that they needed more spaces in their communities to be together post-pandemic and to make up for lost time – togetherness would be very healing. Community members also mentioned that social distancing can become increasingly difficult when trying to stay six feet apart in smaller spaces such as groceries stores, libraries, and community centres.

Mental health and addictions support

Another recommendation, which was supported by an overwhelming majority of participants, was the ultimate need for mental-health and addictions support in communities in Nunavut. This was a significant concern before the pandemic however this issue became exacerbated throughout the pandemic.

Mental health! We need help with addictions and mental health—especially now after COVID. People are stuck in their homes, scared, and facing hard situations. It is not safe for many to be in their homes. There was not enough of this support during COVID, we need more. - Community member 15

Community members either struggled themselves or shared experiences of others close to them with their addiction and mental health.

Inuit qaujimajatuqangiit

As participants reflected on their journey during the pandemic and lessons learned, the theme of adhering to Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit teachings (Inuit knowledge and practices) was prominent. Community members found strength and resilience in the maligait principles, the foundational Inuit laws that govern society [24]. And adhering to these principles allowed them to get through the challenges during the pandemic. Community members spoke of taking care of one another, respecting the land, maintaining harmony and balance, and preparing for their futures while learning and growing from the present. These concepts of maligait were recommended by participants for future emergency situations, i.e. to always stick to what they were taught and carry that forward to future generations.

My recommendation is: be grateful, listen to your Elders, go on the land, connect with the land and your ancestors who have survived worse. We were strong people before the white man came and we have to go back to our ways and take care of each other and live in harmony with the world around us to prevent these viruses. -Community member 23

Healthcare

Access to healthcare was exacerbated by the pandemic. Participants discussed the need for more healthcare professionals in communities during COVID-19 to access services that were not only emergencies, but that the shortage was also a result of longstanding understaffing of community health centres with primary health care, public health, and mental health professionals. They noted the need and use for more remote consultations and phone appointments for prescriptions.

Healthcare was very hard to access—what is considered an emergency? It is hard not having enough nurses and doctors. I know they are tired too and as everyday people, we need prescriptions and have other parts of our body that also need attention, not just the virus and COVID. We have babies and Elders and other ailments too. It would be nice to have a phone call or video call if we can’t go in person for those things. Even if they are somewhere else in Nunavut to help. We need to pull from what we have. - Community member 17

Housing

Housing and overcrowding were significant concerns for community members. This issue is not new to Nunavut, but community members notably mentioned that this made their experience and stresses with the pandemic more difficult. The lack of housing and overcrowding increased food insecurity, financial troubles, and sickness. It also impacted participants’ mental health in a negative way because it increased concerns about their family getting sick and about their finances. Community members stressed that in an emergency response, housing is a fundamental need, and this issue must be resolved to promote wellness in communities. This is therefore a major recommendation.

Housing is my biggest recommendation. I tell others to put their kids on the waitlist as soon as they are 19! We need more space for families to be healthy, how can we get through COVID when we don’t have basic shelter? Housing is very important. We need them to build more apartments and homes so our young ones can have privacy and have their own homes and lives. It is what makes everything else worse for us. - Community member 9

Financial supports and resources

Financial supports were also recommended by community members. The financial funding they received during COVID made all the difference when they could not work, and in emergency situations, this would be important to continue. Participants disclosed that there are many families who are low income, and financial supports such as CERB, EI, food hampers, and isolation kits were suggested for future emergency responses because they were of great benefit during the pandemic.

All the financial help was really good, so that would be my suggestion. Just continue the COVID funding, the hampers, and kits. There are a lot of people who are low income that really struggle. It helped pay my rent, groceries, and bills when I really needed it—so I was very grateful. - Community member 10

Discussion

The findings of this cross-sectional exploratory study shed light on both challenges and strengths experienced by community members in Nunavut during the COVID-19 pandemic. Community perspectives highlighted a holistic determinants of health approach reflective of the Inuit worldview which focuses on harmony and balance in the community and collective wellbeing [24].

Participants highlighted challenges related to mental health, addictions, trauma, and treatment.

Existing research on trauma and addictions treatment in Nunavut emphasise the high prevalence of trauma [25–27], often stemming from historical and intergenerational traumas [28,29], which significantly impact mental health and substance use patterns. Limited access to culturally appropriate and evidence-based treatment options exacerbates these issues [30]. Research underscores the importance of community-based and culturally sensitive interventions, incorporating traditional healing practices and involving local communities in programme development [31–33]. Additionally, studies emphasise the need for trauma-informed care that addresses the underlying causes of addiction [34–36]. Overall, the literature calls for comprehensive, holistic approaches that address trauma in tandem with addiction treatment in Nunavut – a perspective echoed by community members in this study.

Participants in the study highlighted the acute challenges of overcrowding and food insecurity in Nunavut. Previous research has also pointed to alarmingly high rates of household overcrowding, with severe implications for mental and physical health [37–41]. Inadequate housing exacerbates the already precarious issue of food insecurity, driven by factors such as high living costs, the logistics of transporting food to remote communities, and monopolies in the market food sector [42–44]. Research highlights the critical role of country (traditional) foods in Inuit diets and the importance of culturally relevant approaches to address food insecurity [45–47]. Additionally, studies emphasise the need for multifaceted interventions, including housing improvements, economic support, and community-based food initiatives, to alleviate these pressing issues in Nunavut [48].

Participants highlighted the lack of supports for children and youth because Nunavut has many young people and children. To support Nunavut, especially in an emergency response, it is imperative that the wellbeing of the youngest members of the community be kept in mind during planning. Programmes based on cultural teachings are recognised as crucial for fostering resilience and identity [49–51]. Community members also underscore the need for increased funding and community engagement to effectively address the unique challenges faced by children and youth in Nunavut and the community-driven practices that can support them.

Participants in the study highlighted longstanding and system-wide challenges with Nunavut’s healthcare system. Limited healthcare infrastructure, shortage of healthcare professionals are ongoing issues that have also been highlighted by the Office of Auditor General of Canada [51]. Cultural competency gaps and language barriers further impede service delivery and have been well-documented [52,53]. Results of this study underscore the need for increased funding, workforce development, and culturally sensitive approaches to address the pressing healthcare disparities in Nunavut [54–60].

Most importantly, during the COVID-19 pandemic, Nunavut communities demonstrated remarkable resilience through various caregiving pathways for collective well-being. Community love and support formed the cornerstone, as families found ways to protect one another. Special emphasis was placed on the care of elders, recognising their vulnerability. Strict adherence to health protocols was a shared responsibility, reinforcing community-wide safety measures. Initiatives like food hampers provided essential sustenance, alleviating some food insecurity concerns. Radio was, and continues to be, a vital tool for maintaining relationships and connections, offering a lifeline of information and comfort. Financial supports were instrumental in stabilising households, ensuring basic needs were met. The connection to Nuna, the land, and its resources, was revitalised, offering comfort and sustenance. These findings align with other research on Inuit protective public health factors which privileges family and community relationships (Ilagiinniq), the spirit of the collective (Piliriqatigiinniq), connection with the land/environment (Sila/Nuna), and the showing of respect through compassion and kindness (Inuuqatigiittiarniq) [10,54]. Together, these pathways formed a net of support grounded in the Inuit holistic systems approach, amplifying the Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit health perspectives, and highlightings the strength and solidarity of Nunavut communities during the pandemic.

In addition to examining challenges, this study also places a significant emphasis on identifying and understanding the strengths and resiliencies demonstrated by essential workers, community members, and frontline workers in the Arctic territory of Nunavut during the COVID-19 pandemic. Recognising and harnessing these strengths is vital for developing effective interventions and building sustainable strategies for future crises.

By shedding light on the perspectives of those at the forefront of the COVID-19 response in Nunavut, this study aspires to contribute to a deeper comprehension of the unique challenges faced by remote, communities during global health crises. Additionally, the findings aim to inform targeted interventions, policy recommendations, and resilience-building efforts in Nunavut and similar regions facing comparable challenges.

Conclusion

Nunavut communities have experience pandemics in the past, and the embedded cultural practices and teachings within communities were protective factors during the pandemic. Community members know and understand the challenges they face and which are exacerbated by chronic funding and infrastructure deficits. Future research should focus on community-led interventions and adaptations to address these deficits and the holistic Inuit systems thinking approach that is applied moving forward in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Acknowledgments

The researchers wish to acknowledge all the Nunavummiut who contributed their time and stories to helping us learn more about the impacts of the COVID-19 global pandemic on our communities. We also wish to acknowledge the funding from the Government of Canada and Nunavut Tunngavik Inc. that was provided for this study.

Funding Statement

The work was supported by the Government of Canada Nunavut Tunngavik Inc.

Footnotes

Inuktitut word for “the people of Nunavut”.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Researcher Positioning Statement in Relation to Community

ZR has lived and worked in Iqaluit, Nunavut since she was in middle school. ML lived and worked in Nunavut for 10 years. GKHA was born and raised in Iqaluit, NU and continues to live in and raise her family in her home community.

References

- [1].Statistics Canada.Canadian Census: Nunavut Population tables. Ottawa: Government of Canada; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- [2].Orr P. Tuberculosis in Nunavut: looking back, moving forward. Can Med Assoc J. 2013;185(4):287–13. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.121536 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Sandiford Grygier P. A long way from home: the tuberculosis epidemic among the inuit. Montreal (PQ): McGill Queen’s University Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- [4].Kilabuk E, Momoli F, Mallick R, et al. Social determinants of health among residential areas with a high tuberculosis incidence in a remote Inuit community. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2019;73(5):401–406. doi: 10.1136/jech-2018-211261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].ITK ITK . Inuit tuberculosis elimination framework. Ottawa: Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- [6].GN GoN . Nunavut’s path: cOVID-19. Do Health, editor. Iqaluit (Nunavut): Government of Nunavut; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- [7].Frizzel, S. Nunavut’s Confirms 1st case of COVID-19. Canadian Broadcasting Corporation; 2020.

- [8].Larsen CVL, Olesen I, Stoor JP, et al. A review of COVID-19 public Health Restrictions, directives, and measures in Arctic Countries. Norway: Sustainable Development Working Group of the Arctic Council; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- [9].Peterson M,Healey Akearok GK, Cueva K, et al. Public health restrictions, directives, and measures in Arctic countries in the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Healey Akearok G, Rana Z. Community perspectives on COVID-19 outbreak and public health management: Inuit positive protective pathways and lessons for indigenous public health theory Can J Public Health. 2024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Alvarez G, Zwerling A, Duncan C, et al. Molecular epidemiology of mycobacterium tuberculosis to describe the transmission dynamics among Inuit residing in Iqaluit Nunavut using whole-genome sequencing. Clin Infect Dis. 2021;72(12):2187–2195. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa420 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Nunavut Go . Reportable communicable diseases in Nunavut, 2007 to 2014. Iqaluit: Dept. of Health, Government of Nunavut; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- [13].Nunavut Act . 1993. Ottawa: Parliament of Canada. [Google Scholar]

- [14].Government of Nunavut . GN confirms second positive COVID-19 case in Sanikiluaq. 2020. Available from: https://www.gov.nu.ca/health/news/gn-confirms-second-positive-covid-19-case-sanikiluaq.

- [15].Government of Nunavut . COVID-19 GN update – November 16, 2020. Available from. 2020. https://www.gov.nu.ca/executive-and-intergovernmental-affairs/news/covid-19-gn-update-november-16-2020

- [16].Government of Nunavut . Nunavut records tenth COVID-19 death Iqaluit: Government of Nunavut. Iqaluit: Government of Nunavut; 2023. [Google Scholar]

- [17].NACI . Guidance on the prioritization of key populations for COVID-19 immunization. NACo Immunization, editor. Ottawa: Government of Canada; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- [18].Healey G, Tagak SA. Piliriqatigiinniq ‘working in a collaborative way for the common good’: a perspective on the space where health research methodology and Inuit epistemology come together. Int J Crit Indigenous Stud. 2014;7(1):1–8. doi: 10.5204/ijcis.v7i1.117 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Creswell JW. Qualitative inquiry and research design. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks (CA): SAGE Publications; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- [20].Meadows LM, Verdi AJ, Crabtree B. Keeping up appearances: using qualitative research to enhance knowledge of dental practice. J Dent Educ. 2003;67(9):981–990. doi: 10.1002/j.0022-0337.2003.67.9.tb03696.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Morse JM, Barrett M, Mayan M, et al. Verification strategies for establishing reliability and validity in qualitative research. Int J Qual Methods. 2002;1(2):13–22. doi: 10.1177/160940690200100202 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Borkan J. Immersion/Crystallization. In: Crabtree B, Miller W, editors Doing qualitative research. 2nd Edition). 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks (CA): Sage Publications. Pp.; 1999. pp. 179–194. [Google Scholar]

- [23].Morse JM, Swanson J, Kuzel AJ. The nature of qualitative evidence. Thousand Oaks (CA): SAGE Publications; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- [24].Tagalik S. Inuit Knowledge Systems, Elders, and Determinants of Health: Harmony, balance, and the role of holistic thinking. Determinants of Indigenous Peoples’ Health, Beyond the Social. Toronto: Canadian Scholar’s Press. [Google Scholar]

- [25].Rogers D. Discussion about the training needs of emergency shelter staff. Iqaluit: Unpublished; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- [26].Diakite N, Healey Akearok G. Family violence in Nunavut: a scoping review. 2019. [Google Scholar]

- [27].Healey GK. (Re)settlement, displacement, and family separation: understanding the historical events which contribute to health inequality in Nunavut. The Northern Review. 2016;42:47–68. doi: 10.22584/nr42.2016.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [28].ITK ITK . National Inuit Suicide Prevention Strategy. Ottawa: Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- [29].Galloway T, Saudny H. Nunavut community and personal wellness, Inuit health survey (2007-2008). Montreal, OQ: Centre for Indigenous Nutrition and the Environment McGill University; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- [30].Frizzel S. Nunavut addictions treatment centre planned for Iqaluit. CBC North. 2019. Aug 19.

- [31].Lauzière J, Fletcher C, Gaboury I. Cultural safety as an outcome of a dynamic relational process: the experience of Inuit in a mainstream residential addiction rehabilitation Centre in Southern Canada. Qual Health Res. 2022;32(6):970–984. doi: 10.1177/10497323221087540 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Lavalee L, Poole J. Beyond recovery: colonization, health and healing for indigenous people in Canada. Int J Ment Health Addict. 2010;8:271. doi: 10.1007/s11469-009-9239-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Maté G. In the realm of hungry ghosts: close encounters with addiction. Canada: Vintage; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- [34].Marsh TN, Coholic D, Cote-Meek S, et al. Blending aboriginal and Western healing methods to treat intergenerational trauma with substance use disorder in aboriginal peoples who live in northeastern Ontario, Canada. Harm Reduct J. 2015;12(1):14. doi: 10.1186/s12954-015-0046-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Poonwassie A. Grief and trauma in aboriginal communities in Canada. Int J Health Promotion Educ. 2006;44(1):29–33. doi: 10.1080/14635240.2006.10708062 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Wesley-Esquimaux CC, Smolewski M. Historic trauma and aboriginal healing. Ottawa (ON): Aboriginal Healing Foundation; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- [37].Christensen J. Housing is health: coronavirus highlights the dangers of the housing crisis in Canada’s north. Arctic Today. 2020. April 23.

- [38].Sharma R. Construction of PublicHousing units reduced by 24 amid covid-19 - Nunavut News. Nunavut News. 2020. July 23.

- [39].Christensen J. Indigenous housing and health in the Canadian North: revisiting cultural safety. Health Place. 2016;40:83–90. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2016.05.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Schmidt R, Hrenchuk C, Bopp J, et al. Trajectories of women’s homelessness in Canada’s 3 northern territories. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2015;74(1):29778–29779. doi: 10.3402/ijch.v74.29778 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Minich K, Saudny H, Lennie C, et al. Inuit housing and homelessness: results from the international polar year Inuit health survey 2007–2008. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2011;70(5):520–531. doi: 10.3402/ijch.v70i5.17858 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Beaumier M, Ford J. Food insecurity among Inuit women exacerbated by Socio-economic stresses and climate change. Can J Public Health. 2010;101(3):196–201. doi: 10.1007/BF03404373 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Egeland G, Pacey A, Cao Z, et al. Food security among Inuit preschoolers: Nunavut Inuit Child Health Survey, 2007-2008. CanMed Assoc J. 2010;182(3):243–248. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.091297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Galloway T. Is the Nutrition North Canada retail subsidy program meeting the goal of making nutritious and perishable food more accessible and affordable in the North? Can J Public Health. 2014;105(5):395–397. doi: 10.17269/cjph.105.4624 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Kuhnlein HV, Soueida R. Use and nutrient composition of traditional Baffin Inuit foods. J Food Compos Anal. 1992;5:112–126. doi: 10.1016/0889-1575(92)90026-G [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Kinloch D, Kuhnlein H, Muir DCG. Inuit foods and diet: a preliminary assessment of benefits and risks. Sci Total Environ. 1992;122(1–2):247–278. doi: 10.1016/0048-9697(92)90249-R [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].NFSC NFSC . Six Priorities for Food Security in Nunavut Iqaluit: Government of Nunavut and Nunavut Tunngavik Inc; 2016. Available from: https://www.nunavutfoodsecurity.ca/Country_Food.

- [48].GN GoN . Makimaniq: A shared approach to poverty reduction. Iqaluit: Dept. of Family Services, Government of Nunavut; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- [49].Mearns C, Healey Akearok G, Cherba M, et al. Early childhood education training in Nunavut: insights from the inunnguiniq (“making of a human being”) Pilot project. First Peoples Child Family Rev. 2020;15(2):106–122. doi: 10.7202/1080812ar [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Healey GK. Nunavut Inunnguiniq Parenting Program. In: Robinson Vollman A, editor. Canadian Community as Partner. 4th ed. Baltimore (MD): Wolters Kluwer Health; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- [51].Lys C. Exploring coping strategies and mental health support systems among female youth in the Northwest Territories using body mapping. International Journal Of Circumpolar Health. 2018;77(1):1466604–1466611. doi: 10.1080/22423982.2018.1466604 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Healey Akearok G, Tabish T, Cherba M. Cultural orientation and safety app for new and short-term health care providers in Nunavut. Can J Public Health. 2020;111(5):694–700. doi: 10.17269/s41997-020-00311-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Cherba M, Healey Akearok GK, WAS M. Addressing provider turnover to improve health outcomes in Nunavut. CanMed Assoc J. 2019;191(13):E361–E364. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.180908 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Healey Akearok G, Mearns C, Mike N. Inuit Qaujimajatuqnagit Health and Wellbeing System: A Holistic Strengths-based, and health-promoting model from Inuit communities. Inuit Studies Journal. 2024. [Google Scholar]

- [55].Healey Akearok G. Nunavut Health System Governance Scoping Review. 2019.

- [56].Leyland A, Smylie J, Cole M, et al. Health and health care implications of systematic racism on indigenous people in Canada: indigenous health working group, fact sheet. Indigenous Health Working Group Of The College Of Family Physicians Of Canada And Indigenous Physicians Association Of Canada; 2016.

- [57].Carrie H, Mackey TK, Laird SN. Integrating traditional indigenous medicine and western biomedicine into health systems: a review of Nicaraguan health policies and miskitu health services. Int J Equity Health. 2015;14(1):129. doi: 10.1186/s12939-015-0260-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Young T, Chatwood S, Ford J, et al. editor. Transforming health care in remote communities: report on an international conference. Edmonton, Alberta, Canada: BMC Proceedings. 2016;10(Suppl 6):6. doi: 10.1186/s12919-016-0006-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Young K, Marchildon G. A comparative review of Circumpolar Health Systems. 2012; 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Young TK, Chatwood S. Health care in the north: what Canada can learn from its circumpolar neighbours. CMAJ: Can Med Assoc J = Journal de l’Association Medicale Canadienne. 2011;183(2):209–214. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.100948 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]