Abstract

Purpose:

Childhood apraxia of speech (CAS) is a multivariate motor speech disorder that requires a motor-based intervention approach. There is limited treatment research on young children with CAS, reflecting a critical gap in the literature given that features of CAS are often in full expression early in development. Dynamic Temporal and Tactile Cueing (DTTC) is a treatment approach designed for children with severe CAS, yet the use of DTTC with children younger than 3 years of age has not been examined.

Method:

A multiple single-case design was employed to examine the use of DTTC in seven children with CAS (aged 2.5–5 years) over the course of 6 weeks of intervention. Changes in word accuracy were measured in treated words from baseline to posttreatment and from baseline to maintenance (6 weeks posttreatment). Generalization of word accuracy changes to matched untreated words was also examined. A linear mixed-effects model was used to estimate the change in word accuracy for treated and untreated words across all children from baseline to posttreatment and to maintenance. A quasi-Poisson regression model was used to estimate mean change and calculate effect sizes for treated and untreated words.

Results:

Group-level analyses revealed significant changes in word accuracy for treated and untreated words at posttreatment and maintenance. At the child level, six of seven children displayed medium-to-large effect sizes where word accuracy increased in an average of 3.4/5 words across all children. Each child displayed some degree of generalization to untreated targets, specifically for words with the same syllable shape as the treated words.

Conclusions:

These results demonstrate that DTTC can yield positive change in some young children with CAS. Key differences in each child's performance are highlighted.

Childhood apraxia of speech (CAS) is a complex, multivariate speech disorder that involves deficits in praxis, the ability to plan, organize, and sequence speech movements (American Speech-Language-Hearing Association [ASHA], 2007; Ayres, 1985; Campbell et al., 2003; Davis et al., 1998; Forrest, 2003; Shriberg et al., 1997), in the absence of neuromuscular impairment (ASHA, 2007). The impact of this disorder is significant, as children with CAS have highly unintelligible speech, make slow progress in treatment, and typically display erred speech into the school-age years (Lewis et al., 2004). Persistent errors place children with CAS at risk for reading and writing deficits (Lewis et al., 2004; Teverovsky et al., 2009; Zaretsky et al., 2010), which, in addition to poor verbal communication skills, negatively impact academic, social, and emotional growth. Given the profound impact that CAS can have on a child's ability to communicate, there is a need for more treatment research involving this population, particularly for young children (< 3 years) with severe CAS.

The importance of representing young children with CAS in intervention research is well outlined in a recent tutorial on the identification and treatment of children with suspected CAS (Highman et al., 2023). There is compelling evidence that speech motor deficits that are consistent with CAS can be observed in young children's prelinguistic vocalizations (Davis & Velleman, 2000; Highman et al., 2012, 2023; Overby et al., 2020; Overby & Caspari, 2015) and that the presence of a neurodevelopmental disorder places a child at high risk for CAS (e.g., Shriberg et al., 2011, 2019). While we are improving methods for identifying children with (or at risk for) CAS at an early age (e.g., Highman et al., 2023), we are also advancing our understanding of how to intervene early in development. There are treatment approaches designed to enhance vocalizations in infants at risk for CAS (i.e., Babble Boot Camp: Peter et al., 2021, 2019) and to improve functional communication in toddlers with stronger receptive than expressive language skills (e.g., Let's Start Talking: Hodge & Gaines, 2017; Wee Words: Kiesewalter et al., 2017), which have yielded promising results. One area that continues to lag is the application of structured motor-based intervention to young children with CAS. The focus of the present work is to add to the empirical evidence that guides treatment decision making by exploring how young children with a definitive diagnosis of CAS respond to a highly structured, clinician-directed intervention: Dynamic Temporal and Tactile Cueing (DTTC; Strand, 2020).

DTTC is an integral stimulation approach that addresses speech motor deficits by establishing accurate movement gestures through dynamic, hierarchical cueing. Several Phase I studies that describe using or being modeled after DTTC confirm that children with CAS demonstrate significant treatment gains following DTTC, as evidenced by increased word accuracy, generalization to untreated targets, and maintenance of treatment gains (Baas et al., 2008; Edeal & Gildersleeve-Neumann, 2011; Gildersleeve-Neumann & Goldstein, 2015; Maas et al., 2012, 2019; Maas & Farinella, 2012; Strand, 2020; Strand & Debertine, 2000; Strand et al., 2006). Although the evidence base for CAS treatment remains limited, DTTC is recognized as one of the most strongly supported motor-based treatments in the literature to date (Maas et al., 2014; Murray et al., 2014). Existing DTTC research, however, has mainly studied children aged 5 years or older, with no published data on children under the age of 3 years. Enhancing our understanding of how young children with CAS respond to DTTC is key given that features of CAS are typically in full expression at a young age (Shriberg et al., 2011, 2012). The current study will therefore build upon the existing literature to examine the use of DTTC in seven young children with CAS, including a subset of children under 3 years of age (n = 4), using a multiple single-case design.

Treatment Research in CAS

The critical need for research on treatment efficacy in CAS became strikingly apparent following the Cochrane systematic review in 2008, which did not identify any research that stringently examined the efficacy of CAS interventions (Morgan & Vogel, 2009). While a number of interventions are used in clinical practice to treat CAS, there is only a small subset whose effectiveness has been studied by researchers and in children with CAS since that publication. In their systematic review, Murray et al. (2014) identified two motor-based approaches (DTTC: Strand et al., 2006; Rapid Syllable Transition Treatment [ReST]: Thomas et al., 2014) and one linguistic approach (Integrated Phonological Awareness Intervention: McNeill et al., 2009) with treatment and generalization effects, which demonstrated promise for large-scale studies. The Maas et al. (2014) review article on motor-based intervention noted that approaches that incorporate integral stimulation, such as DTTC, are most strongly supported in the literature based on several studies conducted by different research groups (Maas et al., 2014). A more recent Cochrane review (Morgan et al., 2018) identified only one RCT involving children with CAS, which compared ReST and the Nuffield Dyspraxia Programme (Murray et al., 2015). Both treatments demonstrated improvements in the accuracy and consistency of treated words, as well as in the accuracy of connected speech (Murray et al., 2015).

The current work focuses on DTTC because it is a motor-based approach designed for children with severe CAS (Strand, 2020). Despite strong Phase I evidence documenting its success, there is no published research looking at the feasibility of administering DTTC to very young children (< 3 years of age). This is an important need as DTTC is highly structured, involves a great deal of practice, and requires imitation and joint attention. Thus, DTTC may not be suited for every child with CAS. DTTC is based on principles of integral stimulation where the client watches, listens to, and imitates the clinician's speech movements (Strand, 2020; Strand & Skinder, 1999) and is distinct from other treatment approaches. It employs a temporal hierarchy to structure practice, including the following levels: Simultaneous Production, Direct Imitation, Delayed Imitation, and Spontaneous Production. At each level of the hierarchy, practice begins at a reduced rate and moves to a regular rate while incorporating dynamic multisensory cues to shape movement. Principles of motor learning are applied at all levels of the treatment hierarchy to facilitate speech motor learning. DTTC differs from ReST, which aims to improve speech and prosodic accuracy through the practice of multisyllabic nonwords (Ballard et al., 2010; McCabe et al., 2014, 2020; Murray et al., 2015), by targeting movement gestures associated with functional words that are simple yet varied in syllable shape. An important factor that distinguishes DTTC from therapeutic approaches commonly used to address severe speech sound disorders (e.g., Cycles Approach) is that DTTC aims to improve praxis by establishing accurate movement gestures within the production of words, rather than individual sounds or sound classes (Strand, 2020; Strand & Skinder, 1999; Strand et al., 2006; Yorkston et al., 2010). For instance, focus on the movement gesture in “bye” (/baɪ/) targets accuracy and timing of movement from closure for /b/ into opening and transition through /aɪ/. In contrast, traditional therapy may target isolated productions of the /b/ or /aɪ/, which could result in segmentation ([bә. aɪ]). This is detrimental for children with CAS who have poor motor planning skills because they learn two isolated movement gestures, and the transition between gestures is not addressed (Strand, 2020; Strand & Skinder, 1999; Strand et al., 2006; Yorkston et al., 2010).

While DTTC was designed for young children with severe CAS, previous studies that used or were modeled after DTTC (Baas et al., 2008; Edeal & Gildersleeve-Neumann, 2011; Leonhartsberger et al., 2022; Maas et al., 2012, 2019; Maas & Farinella, 2012; Strand & Debertine, 2000; Strand et al., 2006) largely included children who were 5 years of age or older and not always severely impaired. Two studies conducted by Strand and colleagues included children with severe CAS who were 5–6 years of age (Strand & Debertine, 2000; Strand et al., 2006). Their findings are detailed here given that our administration of DTTC mirrored the approach used by Strand et al. In the first study (Strand & Debertine, 2000), one child received DTTC for 33 sessions (4 × 30-min sessions/week). Word accuracy at baseline was at or near zero and ranged in improvement from .25 to .80 (out of a maximum score of 1.0) by the end of treatment. In a second study (Strand et al., 2006), four children received treatment for up to 6 weeks (two sessions per day, 5 days/week). Three of the four children demonstrated marked improvements in word accuracy as demonstrated by maximum accuracy scores on 5/8, 7/8, and 4/8 targets, respectively, as indicated in the figures. There was a modest effect for untreated items, indicating the potential for generalization.

Positive treatment outcomes have been reported across several works using a variant of DTTC (Leonhartsberger et al., 2022; Maas et al., 2012, 2019; Maas & Farinella, 2012), which also highlighted the degree to which treatment results can vary across children. Maas et al. (2012) examined the impact of feedback frequency on four children aged 5;4–8;4 (years;months) who received intervention 3 times per week for 8 weeks. The results were mixed where two of the four children positively responded to low-frequency feedback and one child demonstrated more gains in the high-frequency feedback condition. Maas and Farinella (2012) compared random versus blocked practice in four children with CAS (aged 5;0–7;9) and demonstrated greater gains for two of the four children in the blocked condition and for one child in the random practice condition. To further study treatment intensity, Maas et al. (2019) compared the amount and distribution of practice in six children with CAS (ages 4;7–11;3). The majority of children (4/6) displayed greater gains in word accuracy for a high amount of practice and for massed over distributed practice. In the work of Leonhartsberger et al. (2022), four German-speaking children (ages 4;7–6;0) received intervention for 10 hr, provided either daily (high frequency) or weekly (low frequency). All children displayed improved accuracy of treatment targets that were maintained posttreatment, with similar effects observed under the high- and low-frequency therapy conditions. Taken together, these important studies have begun to establish an evidence base documenting how children with CAS respond to DTTC intervention, or a variant of DTTC. There is a critical need to continue moving this line of research forward by including younger children with CAS. Thus, this case series explored the administration of DTTC in young children with CAS and provides a first look at changes in speech accuracy following a treatment period.

DTTC and the Directions Into Velocities of Articulators Framework

Speech production difficulties may present at a very early age in children with CAS. Retrospective analysis of communication skills in infants and toddlers who were later diagnosed with CAS revealed limited early vocalizations (Overby et al., 2019). Young children with an older sibling with CAS were also found to be more likely to display reduced expressive language and speech motor skills compared to children without a family history of CAS (Highman et al., 2012). Deficits in speech motor planning/programming may underlie these difficulties (Terband & Maassen, 2010) and negatively impact early vocal play (Maassen, 2002). As a result, children with CAS may not have the same opportunity to practice and refine speech sound production, as compared to their unimpaired peers.

The Directions Into Velocities of Articulators (DIVA) framework describes how initial speech production experiences shape the process of speech acquisition (Guenther, 2016; Meier & Guenther, 2023; Tourville & Guenther, 2011). At the earliest stages of speech development, children move from babbling to imitation by establishing connections between articulatory gestures and sensory consequences (i.e., auditory and somatosensory feedback). This period in development corresponds with an imitation phase in the DIVA model, during which auditory targets for speech sounds are learned through exposure, and feedforward motor commands for those sounds are acquired through attempts to produce them (Meier & Guenther, 2023; Tourville & Guenther, 2011). The accuracy of feedforward commands is refined with continued production attempts (i.e., practice) based on information from the feedback system, which is subsequently relied upon less over time as feedforward control improves (Tourville & Guenther, 2011). Children who do not vocalize early in development may not establish these connections that lay the foundation for speech acquisition processes.

The core components of DTTC align with the mechanisms described in the DIVA framework and are particularly relevant for young children with limited verbal output and/or those at early stages of speech production (i.e., syllable and single-word production). In DIVA, neural representations of sounds, syllables, and words are active not only during speech production but also during perception, which are engaged through levels of the DTTC hierarchy. Practice supporting both perception and production mechanisms would, therefore, strengthen connections to auditory and somatosensory targets in the motor and sensory regions of the brain (Meier & Guenther, 2023; Tourville & Guenther, 2011). Exposure and focused attention to a clinician's model, in addition to calling the child's attention to their own speech movements, which are both encouraged in DTTC, may facilitate these connections. DTTC initially targets movement gestures for syllables/words through Direct Imitation, encouraging the child to watch and listen to the clinician and follow the model (Strand, 2020). Furthermore, Simultaneous Production is used if the client does not achieve accuracy at the imitation level, which maintains the visual and auditory model but introduces additional supports as needed, such as tactile/gestural cueing and slowed rate. Slowed articulation rate may help children with CAS utilize sensory feedback and ultimately improve feedforward control (Terband & Maassen, 2010). In addition, the multisensory cueing incorporated into DTTC provides auditory, visual, and somatosensory information, which also supports mechanisms that enhance neural representations to facilitate skill acquisition. Verbal cueing also includes instructing the child to feel their own speech movements within practice at all levels, which is also believed to enhance proprioception and the child's internal feedforward mechanisms. Finally, in line with other bodies of research (Nittrouer & Miller, 1997; Nittrouer et al., 1989), DIVA posits that phonemes, syllables, and common words have their own stored speech motor programs, with syllables being the most common sound chunk (Guenther, 2016; Meier & Guenther, 2023). Because DTTC focuses on movement gestures for syllables and words rather than individual sounds, it can help establish and/or enhance the motor commands for syllables and words, which are stored separately from those for individual phonemes (Guenther, 2016; Meier & Guenther, 2023). Taken together, studying DTTC through the lens of DIVA can help reveal how extensive practice of speech motor skills that provide both auditory and somatosensory input shapes speech acquisition and the development of motor planning/programming skills in children with CAS.

Clinical Needs

There is limited clinical information related to the assessment and treatment of young children with CAS (Davis & Velleman, 2000; Highman et al., 2013; Overby et al., 2019) and a need to provide evidence-based resources for clinical management within this group (Overby & Highman, 2021). While early intervention can benefit children with communication deficits and often entails play-based therapy (Lifter et al., 2011), it was not designed to refine speech motor planning and programming skills, a key area of deficit in CAS. The current work examined the influence of 6 weeks of DTTC on young children with CAS using a multiple single-case design. We aimed to isolate the influence of a speaker's speech motor skills on intervention outcomes by designing treatment targets tailored to each individual child's strengths/weaknesses. Therefore, we examined: (a) changes in speech production accuracy (auditory-perceptual ratings) in treated words following 6 weeks of DTTC, (b) generalization of word accuracy changes in treated words to matched untreated words, and (c) maintenance of changes following a 6-week posttreatment period. DTTC was hypothesized to increase the accuracy of treated words posttreatment, with changes generalized to untreated words and maintained following treatment. Given the children's young age and severity of impairment, generalization to matched untreated targets was predicted to be a first sign of speech motor skill carryover.

Method

Participants

Seven children with severe CAS (ranging from 2;5 to 5;3; < 3 years of age [n = 4]) participated in this study. All children were recruited from the New York City metropolitan area through local speech-language pathologists (SLPs), developmental centers, and the New York University Speech-Language Clinic. Data from the same participants are also reported in the work of Grigos et al. (2023) where the relationship between word accuracy ratings and measures of speech motor control were examined. The same participant numbering was used between studies. This study was approved by the institutional review board at New York University (IRB #: FY2018–1354). Informed consent from caregivers and oral assent from the children were obtained during the initial session.

To be eligible for this study, children were required to meet the criteria for a CAS diagnosis based on the assessment protocol and criteria outlined in the following sections. Other inclusion criteria were normal hearing, intact oral structure and functional integrity, and English as the child's primary language. The exclusion criteria included a comorbid history of other neurodevelopmental disorders (e.g., autism spectrum disorder, genetic disorder, intellectual disability) and coexisting dysarthria. All participants received prior speech treatment, although none were engaged in DTTC treatment. Participants did not receive other speech treatment over the course of baseline testing and intervention; however, they were allowed to return to their previous intervention over the maintenance period to avoid withholding services for a 6-week period.

Assessment Protocol

All children received a comprehensive speech-language assessment by an ASHA-certified and New York State–licensed SLP administered over three sessions. As part of this assessment, children received a comprehensive evaluation of oromotor structure and function, speech sound production, motor speech skills, and expressive–receptive language (see Table 1 for the assessment results). Nonverbal cognition was assessed in the three oldest children (> 3;0). Children under age 3;0 had this testing completed within 3 months prior to the initial assessment, and testing was not repeated.

Table 1.

Participant characteristics.

| Measure | Value | Participants |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | P2 | P3 | P4 | P5 | P6 | P7 | ||

| Age | Years;months | 2;6 | 3;11 | 2;5 | 3;4 | 2;9 | 2;7 | 5;3 |

| DEMSS | Total score | < Age cutoff | 8 | < Age cutoff | 124 | < Age cutoff | < Age cutoff | 64 |

| GFTA-3 | Standard score | Discontinued | 61 | 76 | 65 | 57 | 68 | 40 |

| Percentile | N/A | 0.5 | 5 | 1 | 0.2 | 2 | 0.1 | |

| Receptive Language | Standard score | 81c | 81b | 101a | 115b | 87a | 101a | 105b |

| Percentile | 10th | 10th | 53rd | 84th | 19th | 53rd | 63rd | |

| Expressive Language | Standard score | N/A | 92 | 80 | 115 | 82 | 95 | 123 |

| Percentile | N/A | 30 | 9 | 84 | 12 | 37 | 94 | |

| Cognition | Standard score | 91d | 114e | 82 f | 133e | 76 f | 96 f | 105e |

| Percentile | 27th | 81st | 12th | 98th | 5th | 39th | 62nd | |

| Speech Sample Analysis | PCC | 35.87 | 43.32 | 37.5 | 68.98 | 29.81 | 38.83 | 56.52 |

| PVC | 29.23 | 36.99 | 32.2 | 79.23 | 30.16 | 45.64 | 73.64 | |

| PWC | 37.93 | 20.83 | 45.45 | 58.82 | 30 | 45.45 | 29.31 | |

Note. DEMSS = Dynamic Evaluation of Motor Speech Skill; GFTA-3 = Goldman-Fristoe Test of Articulation–Third Edition; N/A = score not available; PCC = percent consonant correct; PVC = percent vowel correct; PWC = percent word consistent.

Preschool Language Scales–Fifth Edition.

Clinical Evaluation of Language Fundamentals–Preschool: 2nd Edition.

Vineland Total Communication Score.

Differential Abilities Scale-II.

Columbia Mental Maturity Scale.

Stanford Binet Intelligence Scale.

Oral structural and functional examinations included the assessment of facial and intraoral structures for structural integrity, symmetry, and muscle tone. The function of active articulators included the assessment of oral opening/closing, labial retraction/protrusion, lingual elevation/depression/protrusion, and velar elevation. The ability to perform nonspeech oral movements was examined to assess the presence of nonverbal oral apraxia. Motor speech skills were assessed using the Dynamic Evaluation of Motor Speech Skill (DEMSS; Strand & McCauley, 2018). The DEMSS evaluates articulatory accuracy, vowel precision, prosody, and consistency of speech movements across word shapes with increasing complexity. The DEMSS also provides criterion-referenced data for children aged 3;0–7;7, including a range of scores for likely CAS. Three of the seven participants (P2, P4, and P7) were within this age range and completed all eight subtests of the DEMSS. The DEMSS was also administered to the remaining four participants (P1, P3, P5, and P6) under the age of 3 years. Their results were used descriptively to guide stimulus selection. For these younger children, a subtest was discontinued when the child received a score of 0 across three consecutive words and did not imitate or respond to the clinician's cues (Edythe Strand, personal communication, November 16, 2018; Strand & McCauley, 2018).

Speech sound production was assessed using a standardized single-word articulation test, the Goldman-Fristoe Test of Articulation–Third Edition (GFTA-3; Goldman & Fristoe, 2015) and/or a 100-word connected speech sample. All children, except P1, completed the GFTA-3. P1 was one of the youngest participants, whose verbal output was extremely limited. The GFTA-3 was attempted but could not be administered in a standardized format. His 100-word speech sample was collected over several smaller play sessions that occurred over the period of a week. For all participants, speech production skills were closely examined across each speaking context to establish comprehensive phonetic and phonotactic inventories, examine token-to-token consistency, and observe errors in speech production.

Expressive and receptive language skills were assessed using the Preschool Language Scales–Fifth Edition (Zimmerman et al., 2011) in children under age 3;0 (P3, P5, P6). The Expressive and Receptive Language Indices of the Clinical Evaluation of Language Fundamentals: Preschool–Second Edition (Semel et al., 2004) were administered to children ages 3;0 and older (P2, P4, and P7). Language testing was not completed for P1, as this child received a comprehensive assessment through early intervention 1 month prior to enrolling in the study, which included a language assessment. The child's parents provided documentation of the testing performance. The Columbia Mental Maturity Scales (Burgmeister et al., 1972) was administered to evaluate nonverbal reasoning skills as an index of cognition in children older than age 3;0. Children younger than age 3;0 (P1, P3, P5, and P6) completed cognitive testing within 3 months prior to our assessment. Caregivers provided documentation of testing and results, which revealed age-appropriate nonverbal cognition in all four children. To avoid an unnecessary extension of our testing period, we did not repeat these assessments.

A hearing screening at 500, 1000, 2000, and 4000 Hz at 20 dB was conducted in our laboratory for three of the seven children (P2, P4, and P7), all of whom passed. All other participants underwent a complete audiological evaluation conducted by an audiologist within 3 months of the assessment tasks. Caregivers provided documentation of these results, confirming that hearing was within normal limits.

Differential Diagnosis of CAS

Children were required to meet the criteria for CAS according to the independent diagnosis by two SLPs with extensive expertise in the assessment and treatment of CAS (the first and second authors). The diagnostic classification for CAS was based on the presence of at least four of the following characteristics from the Mayo Diagnostic Checklist (Shriberg et al., 2017): vowel distortions, voicing errors, phoneme distortions, articulatory groping, difficulty achieving initial articulatory configurations or transitioning movement gestures, intrusive schwa, increased difficulty with multisyllabic words, syllable segregation, slow speech rate, and stress errors. These characteristics were identified according to performance on two or more of the following: DEMSS (Strand & McCauley, 2018), GFTA-3 (Goldman & Fristoe, 2015), and a connected speech sample. A characteristic was determined to be present when it occurred in more than one speaking context and in at least three different words. As an additional guide for differential diagnosis, characteristics were classified as either discriminative or nondiscriminative for CAS according to Strand (2020) as shown in Table 2. Features discriminative for CAS are: awkward movements from one articulatory configuration to another, articulatory groping, vowel distortions, consonant distortions, prosodic errors, inconsistent voicing errors, intrusive schwa, and inconsistency over repeated trials (Strand, 2020). Performance on all speech and nonspeech tasks was also examined for characteristics of dysarthria that considered range of motion, muscle tone, strength, and movement precision across speech subsystems (Duffy, 2013). None of the participants displayed evidence of dysarthria. These stringent criteria for the differential diagnosis of CAS align with existing approaches across several research groups (Grigos & Case, 2018; Iuzzini-Seigel, 2019; Murray et al., 2015; Shriberg et al., 2017). Table 2 displays the features of CAS observed in each child.

Table 2.

Features of childhood apraxia of speech by participant.

| Participant | No. of Mayo Diagnostic features | No. of discriminative features | Qualitative description within connected speech, dynamic assessment, and single-word production |

|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | 9 | 8 | Severe articulatory groping at the onset of words, effortful productions, vowel distortions, timing errors related to nasality and voicing, syllable segregation and equal stress, and inconsistent errors |

| P2 | 8 | 8 | Lengthened and disrupted transitions between sounds/syllables, pervasive intrusive schwa at word boundary, excessive aspiration at word boundary, severe vowel distortion, slow rate and segmented speech production, and inconsistent errors |

| P3 | 8 | 8 | Effortful speech production and disrupted transitions between sounds/syllables, articulatory groping, vowel distortions and distorted consonant substitutions, intrusive schwa, syllable segregation and equal stress, timing errors related to voicing and nasality, and inconsistent errors |

| P4 | 8 | 8 | Lengthened and disrupted coarticulatory transitions between sounds, vowel distortions and distorted consonant substitutions, excess and inaccurate lexical stress, timing errors related to nasality, articulatory groping, inconsistent errors, and intrusive schwa |

| P5 | 10 | 8 | Effortful speech production with disrupted transitions between sounds/syllables, vowel distortions resulting in shortened vowel and segmented diphthongs, distorted consonant substitutions, excess and equal lexical stress, inconsistent voicing errors, inconsistent errors, and intrusive schwa |

| P6 | 7 | 7 | Lengthened and disrupted coarticulatory transitions between sounds, vowel distortions and distorted consonant substitutions, syllable segregation and inaccurate lexical stress, timing errors related to nasality and voicing, and inconsistent errors |

| P7 | 7 | 8 | Poor coarticulatory transitions between sounds and syllables resulting in glottal insertion at syllable boundaries, vowel distortions and distorted consonant substitutions, inconsistent voicing errors, syllable segregation and inaccurate lexical stress, and inconsistent errors |

Study Design

The current work employed a multiple single-case design, which included baseline data collection, followed by treatment, and then a maintenance phase (see Figure 1). The experiment involved literal replication, which, in the context of a multiple single-case design, is the process of replicating a particular case study, using the same methods, procedures, and measures (Yin, 2018). This approach can help establish the reliability of findings and assess whether the observed effects are stable and consistent across different cases in the study. Thus, children were seen sequentially, and through each replication (i.e., new participant), we duplicated the basic conditions of the prior participant (e.g., study protocol, probing schedule, number of treated items). Guidelines outlined in the What Works Clearinghouse (Kratochwill et al., 2010) were used to determine the number of data collection points across the pre- and posttreatment phases. Several experimental factors related to studying young children with CAS made it challenging to align with Kratochwill et al.'s (2010) standards for single-subject designs. The first concern related to achieving stable baselines prior to the start of treatment. While stable baselines can provide a consistent point of comparison that helps researchers assess treatment effectiveness, they were not feasible to achieve in the current work given the variable nature of CAS and because we used anonymous raters to judge word accuracy, which could only be completed once a child finished all treatment and maintenance phases. The second concern was sequentially introducing multiple baselines for each word, or adding an alternating treatment, both of which would have greatly lengthened the treatment period for these children. This was not deemed appropriate given that this was the first work to explore the feasibility of administering DTTC to young children and that we were requiring children to discontinue their existing SLP treatment while participating in the baseline and treatment phases of the study. Finally, given that this work was focused on young children, a study design was needed that was achievable for this age group with respect to the number of experimental stimuli produced at each probe point and not taking the children out of treatment for extended amounts of time. A multiple single-case design was therefore selected as it offered a pragmatic approach toward studying this population while maintaining experimental control.

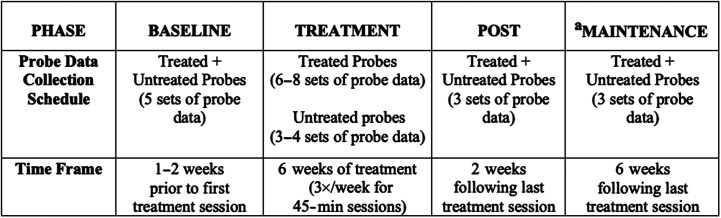

Figure 1.

Schematic of the experimental design that illustrates phases of the study (baseline, treatment, post, and maintenance), probe data collection schedule, and timing for each phase. aChildren resumed previous speech therapy.

Probe data were collected at five time points over the baseline period (i.e., five sets of probe data) for all participants, except P1, who had three sets of probe data owing to time limitations prior to the onset of treatment. Furthermore, probe data were collected at a minimum of six time points across the treatment phase and across three time points each at post and maintenance. The baseline phase took place 1–2 weeks prior to treatment onset. Data collection across multiple baseline points enabled us to capture the natural variability in speech production observed in young children and to control for changes in speech development. At each baseline point, probe data consisted of 50 words presented in a randomized order (10 words [5 treated + 5 untreated] × 5 productions each), which across all baseline points totaled 250 productions. Treated words were used to examine performance pre- to posttreatment. Untreated words were included to evaluate generalization of word accuracy changes to words that were not included in the treatment sessions with similar word shapes as treated words.

The treatment phase included up to three treatment sessions per week (45-min sessions each) for 6 weeks. Although we aimed for 18 treatment sessions per child, the number of completed sessions ranged from 13 to 18 (M = 15.4, SD = 2.1), due to cancellations related to child/family illness and inclement weather. During the treatment phase, probe data were collected at the beginning of treatment sessions at different frequencies for treated than untreated words to avoid a practice effect for the latter. For treated words, probes were collected every second session (six to eight time points) for a total of 25 words (5 treated words × 5 productions each). Untreated words were added to the probe list every fourth session (three to four time points), which expanded the probe list to 50 words (10 words [5 treated + 5 untreated] × 5 productions each). These data were used over the course of intervention for clinical decision making regarding treatment progress.

The post phase took place 2 weeks after the last treatment session. These data were used to examine changes in speech accuracy following DTTC treatment and to determine whether changes were generalized to untreated words. The maintenance phase occurred 6 weeks after the last treatment session to examine the maintenance of changes. Probe data were collected across three different time points, each at post and maintenance. At each time point, probe data consisted of 50 words presented in a randomized order (10 words [5 treated + 5 untreated] × 5 productions each), for a total of 150 productions at each phase.

Treated/Untreated Target Selection

Each participant was assigned five real word pairs with strong communicative potency (e.g., “hi,” “bye”), which were individualized based on performance on the DEMSS (Strand & McCauley, 2019; Strand et al., 2013) and with consideration to segments, vowel distortions, sound combinations, word structure, syllable number, and stress pattern. They included single-syllable words (e.g., “bye,” “up”) and bisyllabic words (e.g., “puppy”) with simple syllable structures (i.e., CV [C = consonant, V = vowel], VC, CVC, CVCV, VCVC). Early-developing phonemes were selected based on each child's phonetic repertoire and response to dynamic assessment during the administration of the DEMSS. From each pair, one word was randomly selected as the treated word and the other became the matched untreated word. Thus, the final set of 10 words included five word pairs, and within each pair, the treated and untreated words were matched as closely as possible with respect to phonetic makeup, word structure, and prosody. Performance on the untreated words was used to monitor generalization. Given the children's young age and CAS severity, we selected matched untreated words, rather than a list of entirely different untreated words (e.g., multisyllabic words with different words structures and phonemes) to capture the point at which generalization may begin to occur similar to past DTTC studies (e.g., Baas et al., 2008; Strand & Debertine, 2000; Strand et al., 2006). See Table 3 for the complete inventory of treated and untreated words for each child.

Table 3.

Treatment stimuli (treated and untreated words) for each participant.

| Participant | Treated words | Untreated words |

|---|---|---|

| P1 | hi, bye, up, mom, uh-oh | me, do, out, bike, happy |

| P2 | bye, up, me, pop, uh-oh | hi, eat, peep, mom, happy |

| P3 | bye, me, pop, out, happy | hi, be, mom, eat, happy |

| P4 | do, out, mine, bed, daddy | go, in, home, down, bunny |

| P5 | bye, me, pop, up, puppy | hi, be, peep, eat, baby |

| P6 | bye, mine, pop, up, puppy | hi, home, peep, eat, baby |

| P7 | up, open, bus, show, puppy | ape, apple, house, shoe, happy |

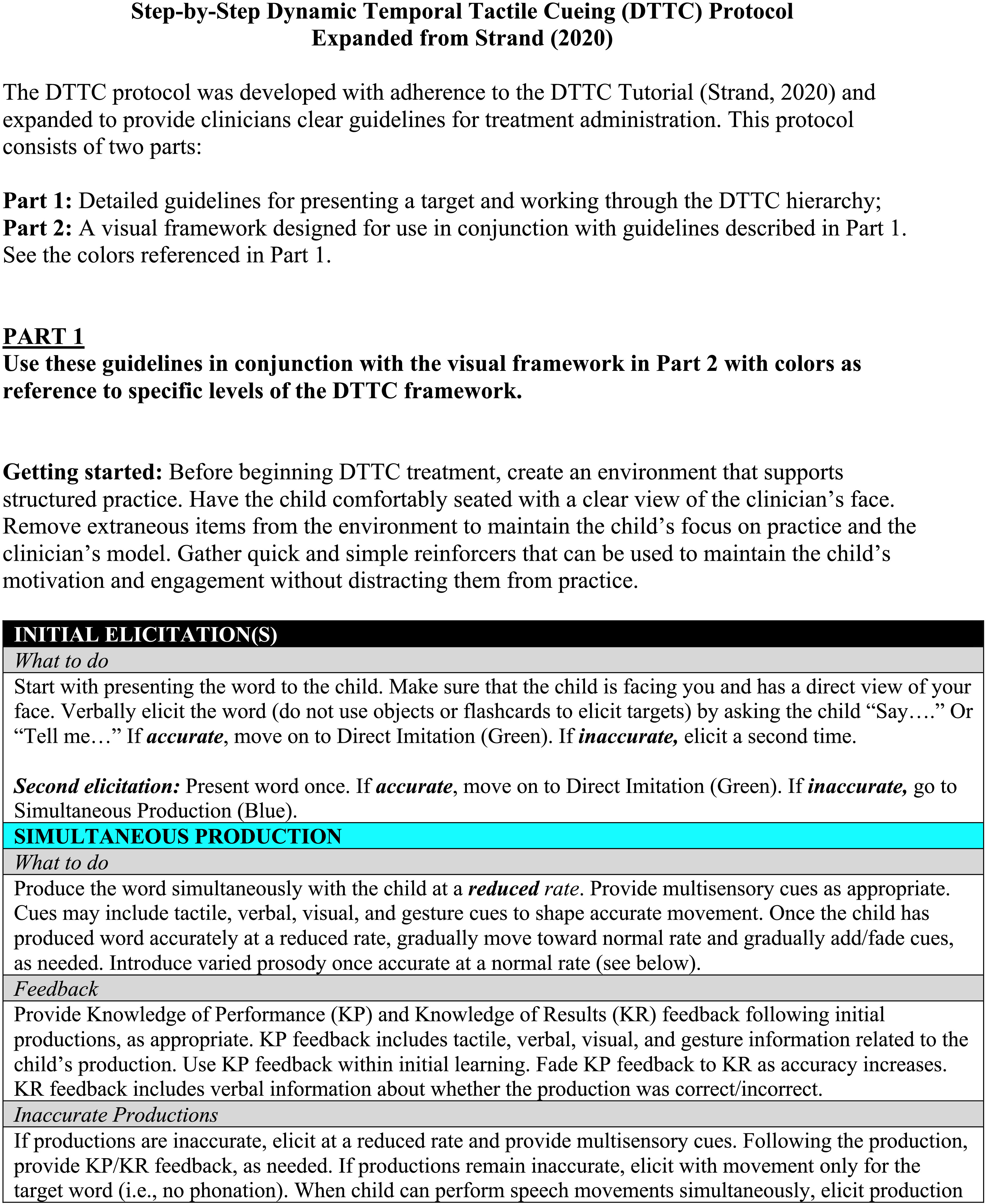

DTTC Procedure

One SLP (J.C.) provided the treatment. The SLP's training was guided by our DTTC treatment protocol (see Appendix A) based on Strand (2020). The clinician utilized DTTC's temporal hierarchy with adherence to Strand (2020; i.e., Simultaneous Production, Direct Imitation, Delayed Imitation, Spontaneous Production) to guide practice and adding/fading of dynamic cues and prosodic variation. The child was first asked to watch the SLP's mouth and then to imitate the SLP's production of the target word. If the child's production was accurate, practice was initiated at the level of Direct Imitation. If the child's imitation was inaccurate, the child was prompted to imitate the SLP's production slowly. If the child's production remained inaccurate, practice proceeded at the level of Simultaneous Production. At every level of the temporal hierarchy, practice began at a reduced rate and gradually moved toward a normal rate as the child's productions became increasingly accurate. When 10–15 accurate productions were achieved at a normal rate of speech without cues, the target was practiced with varied prosody. When the child produced a target accurately and with varied prosody, practice proceeded to the next level of the hierarchy. Conversely, practice reverted to prior levels of the temporal hierarchy when the child did not achieve a target accurately with dynamic cueing at a given level (refer to Appendix A for more detailed guidelines). Such movement through the hierarchy took place each time the clinician and child practiced a given target.

At all levels of the temporal hierarchy, dynamic multisensory cues were added and faded according to the child's performance. Cueing consisted visual cues (“watch me”), verbal cues (“use a big mouth”), gestural cues (open hand to model a big mouth), and tactile cues (placing hands on the child's face to guide movements). Following the child's production, Knowledge of Performance (KP) or Knowledge of Results (KR) feedback was provided. KP feedback consisted of visual, verbal, gestural, or tactile information related to the child's production (e.g., “Bring your lips together more tightly”). As the child gained accuracy with KP feedback, this feedback was faded and KR feedback was introduced to communicate whether the child produced a word accurately (e.g., “correct,” “not quite”).

The treated words were practiced using a modified block schedule that aimed to introduce variability and a level of randomization in order to support motor learning. Individual words were practiced either in larger blocks (15–50 productions) or in smaller blocks (five to 14 productions), which were randomly ordered. There was a mean of 12.25 blocks (SD = 2.75) and 122 productions (SD = 44.59) per session across all treated words (see Table 4). Early in treatment, a smaller number of words were practiced due to severity, and all children practiced five words in a session by the third week of treatment. Parents were not directly involved in the treatment. The children were not assigned home practice to avoid a treatment effect and/or negative practice.

Table 4.

Range (M) of targets, blocks, and productions per session for each participant.

| Participant | No. of sessions | Targets/session | Blocks/session | Productions/sessions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | 13 | 3–5 (4.1) | 6–11 (8.8) | 55–146 (89.5) |

| P2 | 13 | 3–5 (4.1) | 7–16 (9.0) | 74–189 (144.0) |

| P3 | 18 | 3–5 (4.1) | 6–19 (10.8) | 69–123 (81.3) |

| P4 | 18 | 3–5 (4.1) | 10–19 (14.1) | 68–157 (117.9) |

| P5 | 15 | 3–5 (4.6) | 7–21 (14.0) | 75–126 (91.3) |

| P6 | 15 | 4–5 (4.7) | 9–25 (15.9) | 85–168 (122.9) |

| P7 | 16 | 5 (5.0) | 9–18 (13.1) | 168–283 (210.1) |

Treatment Fidelity

Treatment fidelity was assessed by two ASHA-certified SLPs on two treatment sessions for each of the seven participants using a checklist (Appendix B) with key points related to the design of treatment sessions, number of stimuli, and adherence to the treatment protocol. The fidelity SLPs were not familiar with the participants. Fidelity was measured in two ways. First, session-wide characteristics were assessed, which included the SLP and child seating configuration, presence of background noise, number of targets practiced/session, number of trials/session, and use of a modified block practice. Fidelity for these variables was 100%. Second, fidelity was examined within each block, focusing on adherence to the treatment protocol. Fidelity ratings for appropriate clinician model were 99.92%, following the temporal hierarchy was 100%, and accurate use of feedback was 95.23%. Point-by-point reliability between raters was examined across all ratings. Interrater reliability of 100% was achieved across general session observations: 97.43% for clinician model, 100% for temporal hierarchy, and 91.67% for feedback.

Data Collection

Probe data were collected at the beginning of treatment sessions using a word repetition task in which the child repeated the clinician's production. This approach was preferable to using recorded speech because young children with severe speech impairment can have difficulty repeating probes from a continuous recording for behavioral/attentional reasons. Each word was produced five times and presented in a randomized order using the schedule outlined above in the Study Design section and illustrated in Figure 1. The treating SLP collected all probe data as she had established rapport with the child and could accomplish this task efficiently. Positive verbal reinforcement and small toy items were used to engage and motivate children. Probe data were audio-recorded using a Fostex digital recorder at a sampling rate of 44.1 kHz in a sound-treated room. A Shure 10A headset dynamic cardioid microphone was used for probe data collection in two of the participants (P2 and P4). The mouth-to-microphone distance was 5 cm, which was closely monitored to ensure that it remained the same during the data collection period. A Shure SM48 tabletop microphone was used for the children who did not tolerate the headset microphone (P1, P3, P5, P6, and P7).

Outcome Measure

The primary outcome measure was whole-word accuracy, the Multilevel word Accuracy Composite Scale (MACS; Case et al., 2023), which was measured at the baseline, post, and maintenance phases. This metric examines four elements of speech production that align with the characteristics of CAS: segmental accuracy, word structure accuracy, prosodic accuracy (for bisyllabic words), and smoothness of movement transitions. A binary rating of 0/1 was assigned to each of these components (0 = inaccurate, 1 = accurate), and an average composite score was generated across each of these four areas to reflect changes in speech accuracy and generalization to untreated words. This measure has demonstrated concurrent validity with other measures of speech accuracy (e.g., percent phoneme correct) and has achieved excellent reliability among SLP raters (Case et al., 2023). The ratings were completed by three highly trained SLP raters who were unaware of the treatment phase, group, and word status (treated vs. untreated). Prior to completing data analyses, SLP raters completed a series of training sets where they used the MACS to independently rate stimulus sets that contained tokens produced by children with CAS. Following each set of ratings, SLP raters reviewed all points of disagreement with the first and second authors. Data analysis was initiated followed the third set of ratings when each SLP rater achieved a minimum of 90% agreement with laboratory ratings and 90% interrater agreement. The SLPs narrowly transcribed and rated each production using the MACS using only the acoustic signal. Reliability was calculated on 20% of probe ratings across SLP raters. The intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) was calculated for composite MACS ratings. An ICC of .80 was achieved, indicating good interrater reliability (Koo & Li, 2016).

Analyses. Both group- and child-level analyses were completed. Plots were generated for each treated word based on the anonymous ratings performed by SLP raters to examine data trends across all phases of this study. The average baseline accuracy across all words was calculated and included in each plot to reflect the degree of stability of baseline performance across this phase. In addition, one plot was generated to reflect the average word accuracy for combined treated and untreated words for each participant. A closer examination of the data showed that mean word accuracy was intrinsically highly variable and positively correlated with variance. On average, the session-level mean–variance correlation was .4 among the seven subjects with min = .27 and max = .68 (see Table 5). Most children had low word accuracy at baseline, which implied lower variance at baseline. Hence, this further suggested that the assumption of the stable baselines is likely to be consistent with the nature of the data. For each subject, the Friedman test, a nonparametric repeated-measures analysis of variance, was used to examine stability of production accuracy for all words and across all baseline sessions. Nonparametric analyses were used as assumptions of normality were not met.

Table 5.

Mean (standard deviation), effect size + interpretation, and percent gain in word accuracy.

| P1 | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline |

Post |

Baseline–post |

Maintenance |

Baseline–maintenance |

||||||

| Token (T/UT) | M (SD) | M (SD) | Effect size | % Gain | M (SD) | Effect size | % Gain | |||

| bye | T | 0.46 (0.38) | 0.33 (0.18) | −0.26 | −13 | 0.30 (0.25) | −0.33 | −17 | ||

| hi | T | 0.00 (0.00) | 0.04 (0.11) | 0.33 | Small | 4 | 0.07 (0.15) | 0.47 | Medium | 7 |

| mom | T | 0.07 (0.15) | 0.29 (0.12) | 0.65 | Medium–large | 23 | 0.37 (0.11) | 0.80 | Large | 30 |

| uh-oh | T | 0.30 (0.21) | 0.26 (0.19) | −0.12 | −5 | 0.39 (0.20) | 0.19 | Small | 9 | |

| up | T | 0.17 (0.19) | 0.42 (0.15) | 0.57 | Medium | 25 | 0.37 (0.11) | 0.48 | Medium | 20 |

| bike | UT | 0.00 (0.00) | 0.24 (0.32) | 0.85 | Large | 24 | 0.20 (0.17) | 0.78 | Large | 20 |

| do | UT | 0.40 (0.15) | 0.46 (0.25) | 0.11 | 6 | 0.23 (0.16) | −0.36 | −17 | ||

| happy | UT | 0.06 (0.13) | 0.03 (0.08) | −0.20 | −3 | 0.00 (0.00) | −0.43 | −6 | ||

| me | UT | 0.33 (0.00) | 0.44 (0.17) | 0.22 | Small | 11 | 0.44 (0.17) | 0.22 | Small | 11 |

| out | UT | 0.00 (0.00) | 0.10 (0.16) | 0.54 | Medium | 10 | 0.26 (0.15) | 0.88 | Large | 26 |

|

P2 | ||||||||||

|

|

Baseline

|

Post

|

Baseline–Post

|

Maintenance

|

Baseline–maintenance

|

|||||

| Token (T/UT) | M (SD) | M (SD) | Effect size | % Gain | M (SD) | Effect size | % Gain | |||

|

bye |

T |

0.07 (0.14) |

0.40 (0.30) |

0.94 |

Large |

33 |

0.33 (0.00) |

0.80 |

Large |

26 |

| me | T | 0.10 (0.16) | 0.16 (0.17) | 0.20 | Small | 5 | 0.29 (0.13) | 0.57 | Medium | 18 |

| pop | T | 0.39 (0.17) | 0.22 (0.26) | −0.41 | −16 | 0.33 (0.00) | −0.12 | −5 | ||

| uh-oh | T | 0.12 (0.15) | 0.20 (0.11) | 0.27 | Small | 8 | 0.29 (0.10) | 0.52 | Medium | 17 |

| up | T | 0.28 (0.15) | 0.31 (0.20) | 0.07 | 3 | 0.33 (0.00) | 0.13 | 5 | ||

| eat | UT | 0.33 (0.14) | 0.38 (0.12) | 0.10 | 4 | 0.33 (0.00) | 0.00 | < 0.1 | ||

| happy | UT | 0.05 (0.11) | 0.15 (0.20) | 0.40 | Small–medium | 9 | 0.15 (0.14) | 0.45 | Medium | 10 |

| hi | UT | 0.01 (0.07) | 0.27 (0.014) | 0.93 | Large | 25 | 0.33 (0.00) | 1.05 | Large | 32 |

| mom | UT | 0.13 (0.20) | 0.52 (0.44) | 0.85 | Large | 35 | 0.33 (0.21) | 0.54 | Medium | 19 |

| peep | UT | 0.35 (0.07) | 0.33 (0.08) | −0.03 | −1 | 0.33 (0.00) | −0.03 | −1 | ||

|

P3 | ||||||||||

|

|

Baseline

|

Post

|

Baseline–Post

|

Maintenance

|

Baseline–maintenance

|

|||||

| Token (T/UT) | M (SD) | M (SD) | Effect size | % Gain | M (SD) | Effect size | % Gain | |||

|

bye |

T |

0.63 (0.31) |

0.37 (0.35) |

−0.42 |

|

−25 |

0.50 (0.24) |

−0.21 |

|

−13 |

| happy | T | 0.15 (0.14) | 0.13 (0.16) | −0.09 | −3 | 0.08 (0.13) | −0.07 | −24 | ||

| me | T | 0.35 (0.36) | 0.26 (0.32) | −0.09 | −4 | 0.26 (0.19) | −0.09 | −4 | ||

| out | T | 0.22 (0.29) | 0.46 (0.30) | 0.49 | Medium | 24 | 0.19 (0.18) | −0.07 | −2 | |

| pop | T | 0.31 (0.29) | 0.38 (0.37) | 0.13 | 6 | 0.38 (0.28) | 0.12 | 6 | ||

| be | UT | 0.42 (0.23) | 0.24 (0.21) | −0.25 | −12 | 0.11 (0.27) | −0.69 | −29 | ||

| eat | UT | 0.25 (0.14) | 0.56 (0.10) | 0.68 | Medium–large | 36 | 0.33 (0.00) | 0.29 | Small | 13 |

| hi | UT | 0.34 (0.14) | 0.39 (0.18) | 0.08 | 4 | 0.33 (0.47) | −0.05 | −2 | ||

| mom | UT | 0.61 (0.16) | 0.38 (0.09) | −0.39 | −23 | N/A | N/A | N/A | ||

| puppy | UT | 0.14 (0.15) | 0.20 (0.13) | 0.14 | 5 | 0.06 (0.13) | −0.36 | −10 | ||

|

P4 | ||||||||||

|

|

Baseline

|

Post

|

Baseline–Post

|

Maintenance

|

Baseline–maintenance

|

|||||

|

Token (T/UT)

|

M (SD)

|

M (SD)

|

Effect size

|

% Gain

|

M (SD)

|

Effect size

|

% Gain

|

|||

| bed | T | 0.20 (0.24) | 0.44 (0.33) | 0.52 | Medium | 22 | 0.38 (0.13) | 0.38 | Small–medium | 15 |

| daddy | T | 0.23 (0.18) | 0.23 (0.25) | −0.08 | −3 | 0.06 (0.13) | −0.69 | −20 | ||

| do | T | 0.31 (0.30) | 0.53 (0.33) | 0.39 | Small–medium | 19 | 0.47 (0.18) | 0.26 | Small | 12 |

| mine | T | 0.28 (0.23) | 0.33 (0.27) | 0.11 | 4 | 0.58 (0.30) | 0.62 | Medium–large | 29 | |

| out | T | 0.40 (0.29) | 0.54 (0.32) | 0.18 | 9 | 0.56 (0.17) | 0.21 | Small | 11 | |

| bunny | UT | 0.13 (0.17) | 0.26 (0.14) | 0.24 | Small | 8 | 0.50 (0.20) | 0.79 | Large | 33 |

| down | UT | 0.18 (0.21) | 0.44 (0.30) | 0.56 | Medium | 23 | 0.33 (0.00) | 0.32 | Small–medium | 12 |

| go | UT | 0.53 (0.36) | 0.38 (0.36) | −0.36 | −18 | 0.67 (0.27) | 0.18 | 10 | ||

| home | UT | 0.23 (0.24) | 0.38 (0.27) | 0.31 | Small | 13 | 0.27 (0.28) | 0.02 | 1 | |

| in | UT | 0.33 (0.15) | 0.31 (0.20) | −0.15 | −6 | 0.33 (0.00) | −0.10 | −4 | ||

|

P5 | ||||||||||

|

|

Baseline

|

Post

|

Baseline–Post

|

Maintenance

|

Baseline–maintenance

|

|||||

| Token (T/UT) | M (SD) | M (SD) | Effect size | % Gain | M (SD) | Effect size | % Gain | |||

|

bye |

T |

0.29 (0.12) |

0.64 (0.24) |

0.73 |

Medium–large |

36 |

0.37 (0.15) |

0.20 |

Small |

8 |

| me | T | 0.03 (0.09) | 0.64 (0.32) | 1.46 | Large | 61 | 0.41 (0.22) | 1.11 | Large | 38 |

| pop | T | 0.01 (0.07) | 0.05 (0.12) | 0.26 | Small | 3 | 0.00 (0.00) | −0.23 | −1 | |

| puppy | T | 0.20 (0.10) | 0.00 (0.00) | −0.88 | −20 | 0.44 (0.34) | 0.58 | Medium | 23 | |

| up | T | 0.01 (0.05) | 0.00 (0.00) | −0.16 | −1 | 0.00 (0.00) | −0.16 | −1 | ||

| baby | UT | 0.15 (0.13) | 0.26 (0.19) | 0.31 | Small | 10 | 0.30 (0.19) | 0.44 | Small–medium | 15 |

| be | UT | 0.27 (0.19) | 0.60 (0.30) | 0.73 | Medium–large | 36 | 0.41 (0.31) | 0.20 | Small | 8 |

| eat | UT | 0.03 (0.09) | 0.00 (0.00) | −0.33 | −3 | 0.00 (0.00) | −0.33 | −3 | ||

| hi | UT | 0.24 (0.15) | 0.67 (0.41) | 0.89 | Large | 43 | 0.53 (0.32) | 0.66 | Medium–large | 30 |

| peep | UT | 0.00 (0.00) | 0.00 (0.00) | 0 | 0.00 (0.00) | 0 | ||||

|

P6 | ||||||||||

|

|

Baseline

|

Post

|

Baseline–Post

|

Maintenance

|

Maintenance-Post

|

|||||

|

Token (T/UT)

|

M (SD)

|

M (SD)

|

Effect size

|

% Gain

|

M (SD)

|

Effect size

|

% Gain

|

|||

| bye | T | 0.38 (0.21) | 0.53 (0.22) | 0.32 | Small | 14 | 0.81 (0.31) | 0.83 | Large | 42 |

| mine | T | 0.02 (0.08) | 0.00 (0.00) | −0.29 | −2 | 0.35 (0.17) | 1.20 | Large | 33 | |

| pop | T | 0.48 (0.22) | 0.47 (0.17) | −0.04 | −2 | 0.64 (0.32) | 0.33 | Small | 16 | |

| puppy | T | 0.36 (0.15) | 0.38 (0.13) | 0.06 | 2 | 0.55 (0.25) | 0.44 | Small–medium | 19 | |

| up | T | 0.44 (0.25) | 0.45 (0.21) | 0.03 | 1 | 0.62 (0.32) | 0.42 | Small–medium | 20 | |

| baby | UT | 0.34 (0.19) | 0.34 (0.12) | −0.01 | 0 | 0.50 (0.26) | 0.39 | Small–medium | 16 | |

| eat | UT | 0.17 (0.19) | 0.31 (0.09) | 0.46 | Medium | 14 | 0.39 (0.13) | 0.66 | Medium–large | 23 |

| hi | UT | 0.36 (0.16) | 0.40 (0.30) | 0.15 | 6 | 0.60 (0.28) | 0.57 | Medium | 26 | |

| home | UT | 0.40 (0.23) | 0.33 (0.12) | −0.22 | −9 | 0.36 (0.18) | −0.14 | −6 | ||

| peep | UT | 0.40 (0.36) | 0.47 (0.25) | 0.16 | 7 | 0.53 (0.22) | 0.31 | Small | 14 | |

|

P7 | ||||||||||

|

|

Baseline

|

Post

|

Baseline–Post

|

Maintenance

|

Baseline–maintenance

|

|||||

|

Token (T/UT)

|

M (SD)

|

M (SD)

|

Effect size

|

% Gain

|

M (SD)

|

Effect size

|

% Gain

|

|||

| bus | T | 0.37 (0.15) | 0.21 (0.17) | −0.39 | −16 | 0.35 (0.29) | −0.04 | −2 | ||

| open | T | 0.34 (0.14) | 0.27 (0.27) | −0.19 | −9 | 0.21 (0.30) | −0.37 | −17 | ||

| puppy | T | 0.16 (0.12) | 0.18 (0.12) | 0.07 | 2 | 0.13 (0.13) | −0.11 | −3 | ||

| show | T | 0.25 (0.26) | 0.74 (0.27) | 0.89 | Large | 48 | 0.46 (0.22) | 0.45 | Medium | 21 |

| up | T | 0.27 (0.13) | 0.52 (0.34) | 0.52 | Medium | 25 | 0.61 (0.34) | 0.66 | Medium–large | 34 |

| ape | UT | 0.28 (0.12) | 0.58 (0.39) | 0.58 | Medium | 30 | 0.55 (0.38) | 0.53 | Medium | 27 |

| apple | UT | 0.23 (0.11) | 0.15 (0.13) | −0.26 | −10 | 0.13 (0.24) | −0.36 | −14 | ||

| happy | UT | 0.21 (0.22) | 0.28 (0.23) | 0.20 | Small | 8 | 0.20 (0.23) | −0.02 | −0.5 | |

| house | UT | 0.32 (0.18) | 0.25 (0.21) | −0.16 | −6 | 0.33 (0.28) | 0.04 | 2 | ||

| shoe | UT | 0.25 (0.28) | 0.44 (0.16) | 0.42 | Small–medium | 19 | 0.44 (0.22) | 0.42 | Small–medium | 19 |

Note. Mean (standard deviation), effect size + interpretation, and percent gain in word accuracy for treated and untreated words at baseline, post, and maintenance for each participant. Effect size was used to quantify change in word accuracy from baseline to post and from baseline to maintenance. T = treated word; UT = untreated word; N/A = missing data.

Changes in word accuracy over the treatment phase were examined for treated and untreated words across all children. A linear mixed model was fit in R (http://www.r-project.org) using the lme4 and lme4Test (Baayen et al., 2008; Bates et al., 2015) and emmeans (Lenth et al., 2023) packages. Word accuracy was used as the outcome variable with the interaction of session (baseline, post, maintenance) by word (treated, untreated) as predictors. Random effects of child and word were included to account for individual differences in child performance and accuracy by utterance. In this model, we also took into account the differences in accuracy between one-syllable and two-syllable words.

The effect size for group mean comparison is usually defined in the form shown in Equation 1 (Shadish et al., 2015):

| (1) |

Shadish et al. (2015) suggested two methods of calculating standard deviation. If the standard deviation is estimated based on a single case, then the effect size is interpreted as within-subject effect. When the standard deviation is calculated based on pooled data from multiple cases, the effect size can be interpreted as between-subjects effect. In this study, we estimate the within-subject effect size for one child at time.

Typically, change and standard deviation are estimated separately under the assumption that the mean and variance parameters are independent (Robey, 1994), which is not the case in our data. For outcomes that are discrete in nature, Kratochwill et al. (2010) also noted that a relevant distribution, such as the Poisson distribution, should be considered. The mean and variance of a Poisson distribution are the same, and they are determined by a single parameter, . In this case, the mean and variance are not only dependent but identical. To relax the stringent assumption that the mean of the data equals the variance of the data, we used a quasi-Poisson model (McCullagh & Nelder, 1989), where the variance is proportional to the mean up to a constant c. Namely, when the mean of the data is the variance is expected to be c If the constant c is 1, the quasi-Poisson distribution is a Poisson distribution. A constant greater than 1 corresponds to an overdispersed Poisson distribution where the variance is larger than the mean, whereas a constant less than 1 corresponds to an underdispersed Poisson distribution where the variance is smaller than the mean.

Based on the maximum likelihood estimation principle, the deviance residuals of a Poisson regression model follow a chi-square distribution with the degrees of freedom n − p, where n is the total sample size and p is the total number of parameters. When there is no over- or underdispersion, the ratio between the residual deviance and n − p is expected to be close to 1 since the mean of the chi-squared distribution equals the corresponding degrees of freedom. The scaling constant c can then be estimated using the residual deviance divided by n − p (Dunn & Smyth, 2018).

Additionally, since multiple words were included in treatment for each child, we pooled the data from all words produced by the child and estimated the average accuracy rate for each word at different phases through phase–word interactions. However, only one constant c was estimated to capture the overdispersion pattern across all words for one child. This modeling strategy allows us to provide an estimate of the standard deviation taking into account the overall variability in word accuracy by the same child.

For any child, the effect size between baseline and post/maintenance for word i was then estimated where was the estimated baseline mean and was the estimated post mean (t = 2 post and t = 3 maintenance) based on the quasi-Poisson model shown in Equation 2.

| (2) |

The standard deviation in the denominator is calculated as the squared root of . The constant is the estimated ratio between the variance and the mean of the word accuracy rate for the child. This effect size estimator is consistent with Cohen's dav for within-group mean comparison (Cohen, 1988; Cumming, 2013). The generated effect sizes were then interpreted using guidelines established for the interpretation of Cohen's d: 0.2 = small, 0.5 = medium, and 0.8 = large (Cohen, 1988; Lakens, 2013). Using the same formula, we calculated the effect size per word per child. In addition to effect size calculations, percent increases in word accuracy were calculated from baseline to post and baseline to maintenance.

Results

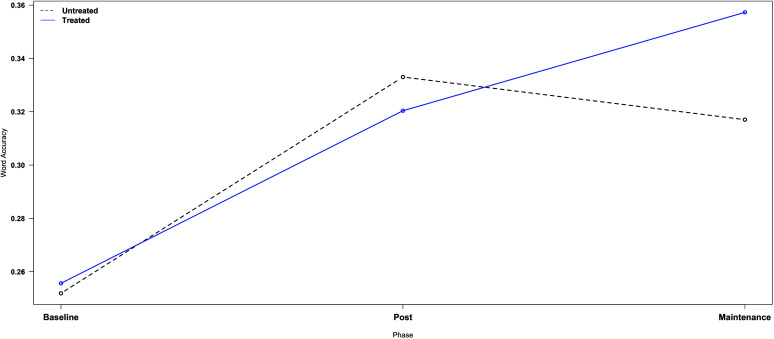

Group analyses. Improved word accuracy (MACS whole-word composite score) was observed across all children for both treated and untreated words from at post, β = .07, SE = 0.02, p = .004, F(1, 434) = 8.97, and maintenance, β = .07, SE = 0.02, p = .0001, F(1, 535) = 14.48 (see Figure 2). When examining treated and untreated words separately, word accuracy was found to improve in treated words from baseline to post (β = .07, SE = 0.02, p = .002) and from baseline to maintenance (β = .10, SE = 0.03, p < .001). No difference in word accuracy was observed from post to maintenance (β = .02, SE = 0.03, p = .4075), indicating that changes from pre- to posttreatment were maintained. In untreated words, word accuracy similarly improved from baseline to post (β = .08, SE = 0.02, p < .001) and from baseline to maintenance (β = .07, SE = 0.03, p = .0148) with no change from post to maintenance (β = .01, SE = 0.03, p = .7894). Taken together, when controlling for syllable number (i.e., one- vs. two-syllable words) and individual differences at the child and word levels, word accuracy improved for both treated and untreated words with a similar degree of change at post (treated: β = .07; untreated: β = .08) and maintenance (treated: β = .10; untreated: β = .07). Similarly, effect size analyses revealed a small effect for treated words (d = 0.26) and a small-to-medium effect for untreated words (d = 0.31) at post. At maintenance, a small-to-medium effect was observed for treated words (d = 0.31) and for untreated words (d = 0.26).

Figure 2.

Average word accuracy (MACS score) across all treated words (solid black line) and untreated words (dashed blue line) is shown for all children. Word accuracy is shown on the y-axis, and treatment phase is shown on the x-axis, which includes baseline, post, and maintenance (dotted vertical line). MACS = Multilevel word Accuracy Composite Scale.

Individual analyses. Given observed differences in word accuracy and performance according to syllable number, additional analyses were performed to examine performance for each individual child. Effect sizes were calculated for treated and untreated words, in addition to each individual word by child, to better understand whether there were more fine-grained changes in word accuracy over this treatment period.

P1. Baseline performance was stable across treated and untreated words (stable baseline assumption: χ2(2) = 0.42, p = .810, with mean word accuracy ranging from 0.00 to 0.33 (see Figure 3a). Effect size analyses revealed a small effect at post for treated words (d = 0.27) and a small-to-medium effect for untreated words (d = 0.31). At maintenance, a small-to-medium effect was observed for both treated (d = 0.42) and untreated (d = 0.38) words.

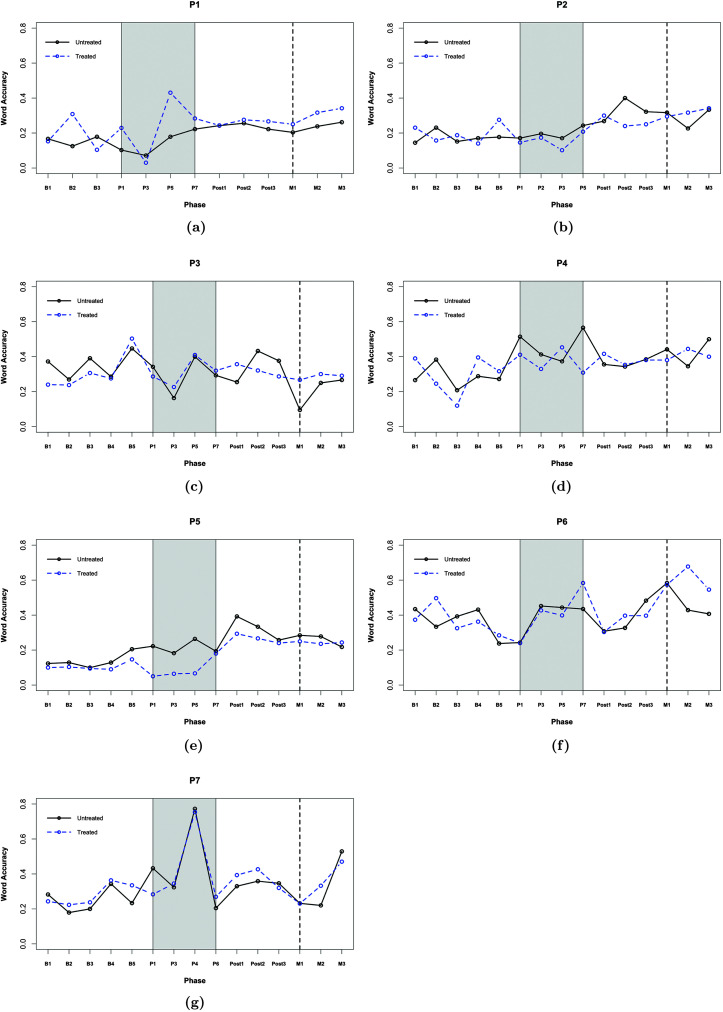

Figure 3.

Average word accuracy (MACS score) across all treated words (solid black line) and untreated words (dashed blue line) is shown for each child (a = P1, b = P2, c = P3, d = P4, e = P5, f = P6, and g = P7). Word accuracy is displayed on the y-axis. Treatment phase is displayed on the x-axis and displays baseline, treatment (gray shading), posttreatment, and maintenance (dotted vertical line). MACS = Multilevel word Accuracy Composite Scale.

Word-level analyses revealed that changes in word accuracy were observed in three of the five treated words (hi, up, and mom) with effect sizes that ranged from small to large at post and maintenance (see Table 5) in these words. At maintenance, word accuracy was maintained and additional improvements in word accuracy were observed in one additional word (uh-oh). Generalization of changes in word accuracy was observed, and improvement in word accuracy was seen in three of the five untreated words (me, out, and bike). These targets matched the word shape of the treated words, which significantly improved in accuracy over the treatment period (hi: CV, up: VC, mom: CVC). P1 did not show progress in other words (including observations of decreased word accuracy for some targets across the treatment period) due to continued difficulty producing nondistorted vowels and accurate prosody in bisyllabic words. Notably, P1 became increasingly conditioned to the structure of therapy over the course of treatment as noted by an increase in the number of productions achieved per session.

P2. Baseline performance was stable across treated and untreated words, χ2(4) = 5.56, p = .234, with mean word accuracy across the baseline phase ranging from 0.08 to 0.40 (see Figure 3b). Effect sizes analyses revealed a small-to-medium effect at post for all treated words (d = 0.34) and a medium effect for all untreated words (d = 0.55). At maintenance, a medium-to-large effect was observed for both treated (d = 0.69) and untreated (d = 0.64) words.

Word-level analyses indicated that changes in word accuracy were observed in three of five treated words with effect sizes ranging from small to large at post and maintenance (see Table 5). At maintenance, changes in word accuracy were maintained for all three words. Generalization of word accuracy was seen in three of the five untreated words (happy, hi, and mom), two of which had the same word shape of treated words that improved over time (uh-oh: CVCV, me/bye: CV). P2 did not display improvement in words (i.e., no change or negative change) with a closed word shape that ended in voiceless stop consonants (eat, peep, pop, up). This child either inserted a post-offset schwa or produced these phonemes with excessive aspiration.

P3. The baseline phase was characterized by variable but nontrending performance with mean word accuracy ratings that ranged from 0.00 to 0.80 (see Figure 3c); however, statistical analyses indicated stable baselines, χ2(4) = 7.69, p = .104. Effect sizes analyses revealed no difference in accuracy at post in treated words (d = −0.01) or untreated words (d = 0.04). At maintenance, a negative effect was observed for both treated (d = −0.05) and untreated (d = −0.52) words.

At the word level, improved accuracy was only observed in one treated word (out), which was supported by a medium effect at post but not maintenance (see Table 5). Increased word accuracy was displayed in one untreated word (eat), which had the same word shape as out. P3 displayed decreased word accuracy across other targets, which was attributed to pervasive vowel distortions, post-offset schwa insertion, and prosodic errors.

P4. Baseline performance was initially stable and then increased over the last two baseline sessions (see Figure 3d) with mean word accuracy ranging from 0.00 to 0.73 across the baseline phase. As a result, P4 did not exhibit stable baselines, χ2(4) = 11.15, p = .025. Effect size analyses revealed a small-to-medium effect at post for all treated words (d = 0.42) and a small effect for all untreated words (d = 0.27). At maintenance, a medium effect was observed for both treated (d = 0.54) and untreated (d = 0.52) words.

Word-level analyses indicated that two of the five treated words (bed and do) increased in accuracy with effect sizes that ranged from small to medium–large at post for these words. At maintenance, changes in word accuracy were slightly lower for both words, while two additional treated words displayed improved word accuracy only at maintenance, as evidenced by small to medium–large effect sizes (see Table 5). Generalization of word accuracy changes to untreated words was observed in three out of the five words (down, home, and bunny). Two of these words matched the word shape of the treated words where increases in word accuracy were observed (CVC: bed). P4 did not show improvement in one treated word, daddy, which was attributed to inaccurate stress patterning and difficulty achieving anterior contact for alveolar phonemes. Progress may also have been inhibited by the high-frequency use of this word, which could result in errors requiring additional time to resolve during intervention.

P5. The child did not display stable baseline performance, χ2(4) = 14.94, p = .005, with initial accuracy ranging from 0.00 to 0.33 (see Figure 3e). Effect size analyses revealed a medium-to-large effect at post for both treated (d = 0.62) and untreated (d = 0.73) words. At maintenance, a medium-to-large effect was observed for treated words (d = 0.79) and a medium effect for untreated words (d = 0.55).

At the word level, increases in accuracy at post were observed in three of five treated words (bye, me, and pop) with small-to-large effect sizes in these words at post and maintenance (see Table 5). At maintenance, improved accuracy was maintained for one word (me), minimal for a second word (bye), and not maintained for the third word as accuracy decreased in this target (pop). One additional word (puppy) displayed declined accuracy at post yet improved word accuracy at maintenance, as the intervocalic bilabial closure emerged at the end of the treatment phase. Generalization was observed in three of the five untreated words (hi, be, and baby). These targets matched the word shape of the treated words, which significantly improved in accuracy at post (me/bye: CV) and maintenance (puppy: CVCV; see Table 5).

P6. Accuracy rate at baseline was stable for the first few sessions but then decreased over the last two baseline sessions (see Figure 3f). However, such change was not statistically significant, χ2(4) = 4.89, p = .299. Mean word accuracy ranged from 0.00 to 0.70 across the baseline phase. Effect size analyses revealed no effect at post for either treated (d = 0.02) or untreated (d = 0.00) words. At maintenance, a medium-to-large effect was observed for treated words (d = 0.69) and a small-to-medium effect in untreated words (d = 0.41).

Word-level analyses revealed improved accuracy in one word (bye) from baseline to post supported by a small effect size. The remaining four treated words (mine, up, puppy, and pop) only showed changes in word accuracy at maintenance, which was supported by small–medium to large effect sizes (see Table 5). Generalization of word accuracy to untreated words was observed in one word (eat) at post and three other untreated words (baby, hi, and peep) at maintenance. Untreated targets that showed improvements in word accuracy matched the syllable shapes of treated targets that improved over the intervention period. One target that did not change—and displayed decreased accuracy—was home, as difficulty in timing for the word-final nasal persisted despite improved accuracy in the matched treated word mine (see Table 5).

P7. At baseline, the child's performance was initially stable and then slightly increased over the last two baseline sessions (see Figure 3g). Statistically, the variability at the baseline was significantly different from what would be expected under the stable baseline assumption, χ2(4) = 11.37, p = .023. Across baseline, mean word accuracy ranged from 0.00 to 0.56. From baseline to post, effect sizes analyses revealed a small-to-medium effect for treated words (d = 0.43) and a small effect for untreated (d = 0.33) words. At maintenance, effect sizes were slightly smaller than post with a small effect for treated (d = 0.28) and untreated (d = 0.29) words.

At the word level, improved accuracy was observed in two of the five treated words, up and show, with medium-to-large effect sizes at post and maintenance. At maintenance, increases in word accuracy were slightly larger for one word (up) but decreased to a medium effect in the second word (show). Despite changes in these targets, P7 displayed continued difficulty achieving smooth movement transitions across syllables and accurate prosody in bisyllabic words, in addition to inconsistent voicing errors for word-within stop plosives. This child also struggled to smoothly transition from a vowel into the voiceless continuant /s/ and displayed persistent glottal insertions and voicing errors in this context. Generalization was observed as improvement in word accuracy was seen in two of the five untreated words (ape and shoe) that matched the word shape of the treated words where improved accuracy was observed over treatment (shoe: CV, up: VC; see Table 5).

Discussion

This study quantified changes in word accuracy in seven young children with CAS who received up to 6 weeks of DTTC treatment, three times per week. Treatment was delivered by one SLP with high fidelity (greater than 90%). Changes in word accuracy were based on auditory-perceptual ratings completed by SLPs who were unaware of treatment phase, group, and word status. At the group level, word accuracy improved for both treated and untreated words at post and maintenance. Effect size analyses revealed similar improvement in word accuracy for untreated words at post (treated: d = 0.26; untreated: d = 0.31), and for treated words at maintenance (treated: d = 0.31; untreated: d = 0.26). These results are interesting to consider given that children only produced the untreated words during probe data collection (i.e., 75–100 times within probe sessions during the treatment period). In comparison, they produced treated words much more frequently during probing (i.e., 150–200 times), in addition to practicing the words extensively in the context of treatment (i.e., M = 122.4 [SD = 44.5] productions each session).

Across the treatment and follow-up phases, children demonstrated interesting trajectories of change in word accuracy, which occurred gradually over time and displayed patterns of improvement and declines for all words and is reflective of the variable nature of CAS. Gradual change in both treated and untreated words is challenging to interpret in the context of a case study design. On one hand, steady improvement in some treated and untreated words may be viewed as an anticipated and promising outcome for young children with severe CAS engaged in a short period of intervention. Alternatively, we cannot rule out that such findings reflect maturation or repeated probing effects. The latter feels much less plausible as treated words did not show a greater degree of change compared to untreated words even though they were probed at a much higher frequency. Patterns of both positive and negative changes in speech accuracy are interpreted to reflect the process of exploring production abilities and attempts at establishing more efficient speech production mechanisms, which likely required more time and practice to demonstrate stable patterns of improvements (Green & Nip, 2010). Further study of a larger sample of children with CAS using methods involving greater experimental control is needed to better explore the role of such factors during speech motor treatment.

Child-level analyses provided insight into performance across children and their individualized treatment targets. Improved word accuracy was observed in six of the seven participants for treated and untreated words, in an average of 3.4/5 (68%) words, by either post or maintenance. Overall, children's performance varied widely, where changes at post and maintenance ranged from improvement in one treated word (P3) to all five treated words (P6). As a result, child-level effect size analyses did not reveal significant changes in word accuracy in all children, while word-level analyses revealed that changes in accuracy were beginning to emerge, even if only in one word. Each child displayed some degree of generalization to untreated targets, which were matched in phonetic makeup, word structure, and prosody to treated targets. We are cautious in overinterpreting these results given the lack of experimental control (i.e., multiple baselines, alternating treatment design) and unstable baselines in three of the seven participants. Below, we expand on the factors that may have supported improved word accuracy and highlight the need for future treatment research involving young children with CAS.

Facilitating Skill Acquisition and Learning Through DTTC