Abstract

Introduction:

Young adults experiencing homelessness are at increased risk for sexual assault. Receiving a post-sexual assault examination has important implications for HIV and unintended pregnancy prevention; yet, utilization is not well understood. In a population at elevated risk for HIV, unintended pregnancy, and sexual violence, identifying barriers and facilitators to post-sexual assault examination is imperative.

Methods:

As part of a large, multisite study to assess youth experiencing homelessness across seven cities in the U.S, a cross-sectional survey was conducted between June 2016 and July 2017. Data were analyzed in 2019 to determine the prevalence and correlates of sexual violence and examine the correlates of post-sexual assault examination utilization.

Results:

Respondents (N=1405), aged 18–26 years, were majority youth of color (38% black, 17% Latinx) and identified as cisgender man (59%) and lesbian, gay, bisexual, or queer (29%). HIV risks were high: 23% of participants had engaged in trade sex, 32% had experienced sexual assault as a minor, and 39% had experienced sexual exploitation. Young adults reported high rates of sexual assault (22%) and forced sex (24%). Yet, only 29% of participants who were forced to have sex received a post-sexual assault examination. Latinx young adults were more likely than other race/ethnicities to receive post-assault care. Participants frequently said they did not get a post-sexual assault exam because they did not want to involve the legal system and did not think it was important.

Conclusions:

Interventions are needed to increase use of preventive care after experiencing sexual assault among young adults experiencing homelessness.

INTRODUCTION

Approximately 19% of cisgender women and 2% of cisgender men reported a lifetime history of rape.1 Although these rates are alarming, young adults experiencing homelessness are at even higher risk than their housed peers, with prevalence rate of lifetime sexual assault as high as 35%.2 Sexual violence contributes to high risk for HIV, sexually transmitted infections (STIs), and unintended pregnancy.

In the general population, demographic factors such as race, sexual orientation, and gender identity are associated with an increased risk for sexual assault. Black cisgender women are more likely to experience assault before age 25 years compared with white cisgender women, and black undergraduate students have higher odds of sexual assault than white, Latinx, and Asian students.3,4 Lesbian, gay, bisexual, queer (LGBQ), and transgender youth report experiencing more sexual violence than heterosexual and cisgender youth.4 And, transgender individuals experience sexual violence twice as often as cisgender LGBQ individuals.5 Among those experiencing homelessness, rates of sexual assault are also higher in women than men and were highest among transgender people.6–8 Other risk factors that have been found to increase the risk of sexual assault include substance use, exposure to violence, child abuse, sexual behaviors, peer relationships, health status, and homelessness experience as well early onset and longer length of homelessness, and trading sex.2,7,9–13

A major public health concern of sexual violence is exposure to HIV and STIs, and unintended pregnancy.14–17 The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention treatment guidelines for post-sexual assault care are aimed at targeting these risks.18 Use of HIV non-occupational postexposure prophylaxis for sexual assault patients is recommended in the guidelines based on exposure timing and characteristics.19 However, little is known about post-sexual assault healthcare utilization among youth experiencing homelessness.

Care for acute sexual assault, including HIV/STIs and unintended pregnancy prevention, often depends on a youth to disclose sexual violence and seek care within the brief post-assault window related to prevention medication efficacy. Tragically, few people seek post-sexual assault care at all let alone in time for HIV and pregnancy prevention-based interventions. In a nationally representative sample, only 21% of sexual assault patients sought medical attention, with those who experienced physical assault being more likely to disclose the sexual assault and seek services.14,20 Other correlates of seeking post-assault medical care are race (identifying as black), experiencing genital injuries, concern about STIs or pregnancy, and reporting the incident to the police.14 Perceived shame, guilt, having a relationship with the perpetrator, and having negative past experiences with the healthcare system have been associated with not seeking care.14,21–23 In addition, healthcare seeking behaviors are often lower among young adults experiencing homelessness and adolescent boys and young men.24,25

Experiencing sexual assault has significant acute and chronic physical and mental health implications, highlighting the important role of prevention, screening, and treatment interventions.26 Yet, the literature has two important limitations addressed in the current study. First, most studies among youth experiencing homelessness are derived from single-city samples, which potentially reduces the generalizability of the findings. Second, little has been published on the knowledge, incidence, and correlates of post-sexual assault examination among this population. Therefore, this study was conducted to assess the prevalence and correlates of sexual assault and utilization of post-sexual assault examination in a large sample of youth experiencing homelessness from seven cities across the U.S. to inform prevention and healthcare service delivery.

METHODS

Interdisciplinary researchers examined youth experiencing homelessness (aged 18–26 years) in Los Angeles, San Jose, Phoenix, St. Louis, Denver, Houston, and New York City between June 2016 and July 2017. Using a cross-sectional study design and a standardized study protocol, data were collected through a self-administered survey completed on a tablet. IRBs at the authors’ academic institutions approved the study procedures.

Study Sample

Using purposive sampling, each site recruited approximately 200 unique young adults from service agencies including drop-in centers, shelters, and transitional housing to capture the variation in experiences and demographics of young people accessing different types of homeless services. Participation was limited to English-speaking youth owing to previous research indicating few non-English speaking young adults are accessing homeless services.27 Youth at the service agencies during the data collection period were approached and screened for eligibility. Participants had to be aged 18–26 years and homeless or unstably housed.

A research assistant reviewed informed consent, and participants indicated whether they agreed to participate by clicking a box on the tablet. After securing consent, a person identification code was generated for each participant. Next, the young person completed the Rapid Estimate of Adult Literacy in Medicine short form screener.28 Youth were asked to complete the self-administered survey independently on the tablet if they scored higher than 3, though study staff were available to assist participants. The survey took about 50 minutes to complete. Participants received a $10 (in Phoenix) or $20 gift card (all other locations) for a local store.

Measures

The survey assessed demographics and homelessness factors using previously validated measures. Age was dichotomized as 18–21 and 22–26 years to align with federal and state legislation and funding guidelines using 21 years as the maximum age for young adults to remain in foster care and receive services funded by the Runaway Homeless Youth Act.29,30 Youth self-identified as cisgender men, cisgender women, transgender, or gender expansive. Race/ethnicity was defined as white, black, Latinx, other, and mixed race. Youth identified as lesbian, gay, bisexual, queer, or heterosexual. For homelessness, youth indicated where they slept the night before (coded as couch surfing if they were staying with a friend, relative, or acquaintance; sheltered if they stayed in a shelter or transitional housing; and outside if they stayed in a place not meant for human habitation). To assess for childhood onset homelessness, age at first homelessness was dichotomized as prior to age 18 years or after age 18 years. Length of current homelessness was dichotomized as >2 years or <2 years.

Adverse childhood experiences were queried using the ten-item Adverse Childhood Experiences scale.31 Youth were asked if they had ever traded sex for money, drugs, a place to stay, food/meals, or anything else. Sex trafficking was assessed by asking if youth were ever forced to exchange sex. Experiences of dating violence were queried by asking if youth had ever been hit, pushed, shoved, punched, or physically hurt by a person that they had been romantically or intimately involved with since being homeless or unstably housed. Involvement in the juvenile justice system was assessed with a single item that asked if they had ever been involved with juvenile court, probation, detention, or diversion.

For sexual assault, participants were asked if anyone had touched their private parts when they should not have or made them touch their private parts since being unstably housed or homeless. For forced sex, the survey inquired if anyone had tried to force them to have sex since experiencing unstable housing or homelessness. For youth who had been forced to have sex, the survey inquired whether they had received a sexual assault examination at a hospital or clinic. Finally, youth who indicated that they did not receive an exam were asked to check all that applied for why they did not get a post-sexual assault examination (e.g., didn’t know where to go, couldn’t safely leave the situation, didn’t know what the exam was, didn’t think it was important, didn’t go because they didn’t have health insurance, and didn’t want to involve the legal system).

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed between January and February 2019. Associations between demographic and risk factors and sexual assault, forced sex, and post-sexual assault examination were examined. Comparisons of categorical measures with the three outcome variables were conducted with the chi-square test, with the exact version used when any expected cell count was <5. Separate logistic regression models were used to test associations between sexual assault and forced sex and ≥2 years of homelessness and homelessness prior to age 18 years, adjusting for race/ethnicity, gender identity, sexual orientation, and childhood sexual abuse. Bivariate analyses of associations with reasons for not getting a post-sexual assault examination were also conducted with the chi-square test using SPSS 25.

RESULTS

The participants (N=1,405) were majority aged 18–21 years (64%), youth of color (38% black, 17% Latinx), and identified as cisgender men 59%, with 7% who identified as transgender or gender expansive (Table 1). More than a quarter of youth (29%) identified as LGBQ. Most participants reported having been homeless for <2 years (78%) and first experiencing homelessness after age 18 years (60%). Approximately one third had slept outside or in a place not meant for human habitation the night before the survey. Youth reported high rates of engaging in trade sex (23%), experiencing childhood sexual abuse (32%), being involved in sex trafficking (39%), and experiencing dating violence (29%).

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics and Experiences of Sexual Assault and Forced Sex

| Characteristic | Total sample, n (%) | Sexual assault, n (%) | χ2 (df); p-value | Forced sex, n (%) | χ2 (df); p-value | Received post assault exam, n (%) | χ2 (df); p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total sample | 1,405 | 305 (21.7) | 337 (24.0) | 98 (29.2) | |||

| Age, years | 0.102 (1); 0.75 | 0.60 (1); 0.44 | 0.00 (1); 0.99 | ||||

| 18–21 | 900 (64.1) | 193 (21.4) | 210 (23.4) | 61 (29.2) | |||

| 22–26 | 505 (35.9) | 112 (22.2) | 127 (25.2) | 37 (29.1) | |||

| Race/ethnicity | 17.82 (4); 0.01 | 10.86 (4); 0.028 | 12.80 (4); 0.012 | ||||

| White | 267 (19.0) | 53 (20.0) | 65 (24.4) | 33 (31.1) | |||

| Black | 528 (37.5) | 98 (18.6) | 106 (20.1) | 18 (30.5) | |||

| Latinx | 243 (17.3) | 54 (22.2) | 60 (24.7) | 15 (41.7) | |||

| Other | 144 (10.2) | 28 (19.4) | 36 (25.0) | 24 (34.3) | |||

| Mixed | 228 (16.1) | 72 (32.0) | 70 (31.1) | 8 (12.2) | |||

| Gender identity | 74.64 (2); <0.01 | 98.10 (2); <0.01 | 8.79 (2); 0.12 | ||||

| Cisgender men | 833 (58.5) | 113 (13.7) | 120 (14.6) | 25 (20.8) | |||

| Cisgender women | 483 (33.9) | 158 (33.1) | 175 (36.8) | 63 (36.2) | |||

| Transgender/gender expansive | 107 (7.5) | 34 (32.4) | 42 (40.4) | 10 (23.8) | |||

| Sexual orientation | 63.41 (1); <0.01 | 55.44 (1); <0.01 | 0.012 (1); 0.91 | ||||

| LGBQ | 403 (28.6) | 143 (35.5) | 150 (37.4) | 43 (28.9) | |||

| Heterosexual | 1,004 (71.4) | 162 (16.1) | 187 (19.6) | 55 (29.4) | |||

| Length of homelessness | 11.32 (1); <0.01 | 26.24 (1); <0.01 | 0.21 (1); 0.65 | ||||

| >2 years homeless | 305 (21.7) | 117 (27.3) | 141 (32.8) | 43 (30.5) | |||

| ≤2 years homeless | 1,101 (78.3) | 198 (19.2) | 196 (20.1) | 55 (28.2) | |||

| First age homeless | 4.27 (1); 0.04 | 11.52 (1); <0.01 | 0.03 (1); 0.88 | ||||

| <18 | 564 (40.2) | 137 (24.3) | 161 (28.5) | 45 (28.1) | |||

| ≥18 | 839 (59.8) | 165 (19.7) | 173 (20.7) | 50 (28.9) | |||

| Shelter status | 2.69 (2); 0.26 | 0.09 (2); 0.96 | 1.99 (2); 0.37 | ||||

| Couch surfing | 261 (18.6) | 56 (21.5) | 63 (18.8) | 21 (33.3) | |||

| Shelter | 682 (48.6) | 160 (23.5) | 165 (24.3) | 51 (30.9) | |||

| Outside | 459 (32.7) | 89 (19.4) | 108 (23.5) | 26 (24.3) | |||

| City | 4.00 (6); 0.69 | 10.96 (6); 0.09 | 7.96 (6); 0.24 | ||||

| Los Angeles | 213 (15.1) | 47 (22.1) | 57 (26.6) | 15 (26.3) | |||

| Denver | 207 (14.7) | 38 (18.4) | 34 (16.6) | 8 (23.5) | |||

| Houston | 201 (14.3) | 50 (24.9) | 53 (26.4) | 22 (41.5) | |||

| Phoenix | 205 (14.6) | 48 (23.4) | 55 (26.8) | 13 (23.6) | |||

| St. Louis | 194 (13.8) | 39 (20.1) | 40 (20.6) | 14 (35.0) | |||

| New York City | 195 (13.8) | 45 (23.1) | 53 (27.3) | 17 (32.1) | |||

| San Jose | 193 (13.7) | 38 (12.5) | 45 (23.3) | 9 (20.5) | |||

| Traded sex | 263 (23.3) | 115 (41.7) | 69.00, <0.01 | 137 (50.0) | 103.53; <0.01 | 44 (32.1) | 1.61 (1); 0.21 |

| Ever childhood sexual abuse | — | — | 239.61 (1); <0.01 | — | 206.86 (1); <0.01 | — | 3.30 (1); 0.07 |

| Yes | 445 (31.8) | 207 (46.5) | 213 (48.0) | 69 (32.5) | |||

| No | 954 (68.2) | 95 (10.0) | 121 (12.7) | 28 (23.1) | |||

| Ever sex trafficked | 18.08 (1); <0.01 | 24.54 (1); <0.01 | 0.82 (1); 0.36 | ||||

| Yes | 106 (38.7) | 61 (53.5) | 72 (53.3) | 21 (29.2) | |||

| No | 168 (61.3) | 53 (46.5) | 63 (46.7) | 23 (52.3) | |||

| Ever dating violence | 1.69 (1); 0.19 | 3.07 (1); 0.08 | 2.15 (1); 0.14 | ||||

| Yes | 36 (29.3) | 36 (16.5) | 43 (19.7) | 7 (16.3) | |||

| No | 87 (70.7) | 107 (13.1) | 121 (14.6) | 33 (27.5) |

Note: Boldface indicates statistical significance (p<0.05). df, degrees of freedom. LGBQ, lesbian, gay, bisexual, queer.

Youth reported high rates of sexual assault (22%) and forced sex (24%). In bivariate analyses, significant differences were found for sexual assault and forced sex by race/ethnicity, gender identity, and sexual orientation, with mixed race, cisgender women, and LGBQ youth having the highest rates (Table 1). Transgender/gender expansive youth had the highest rate of forced sex.

In addition, longer durations and earlier onset of homelessness were significantly associated with experiences of sexual assault and forced sex. No differences were found by shelter status or recruitment city. Experiencing childhood sexual abuse, engaging in trade sex, and experiencing sex trafficking were all significantly associated with sexual assault and forced sex.

Multivariable analyses with logistic regression models (Table 2) indicated that cisgender women had odds 1.92 (95% CI=1.40, 2.63) times higher than cisgender young men of experiencing sexual assault and more than twice the odds (OR=2.41, 95% CI=1.78, 3.27) of experiencing forced sex compared with cisgender men. LGBQ respondents had odds 1.82 (95% CI=1.33, 2.47) times higher of experiencing sexual assault and 1.54 (95% CI=1.14, 2.08) times higher of experiencing forced sex compared with their heterosexual counterparts. Respondents with >2 years of homelessness had odds 1.49 (95% CI=1.08, 2.05) times higher of experiencing sexual assault and odds 1.88 (95% CI=1.38, 2.55) times greater of experiencing forced sex than youth who had been homeless for <2 years. Those experiencing childhood sexual abuse had odds almost six times (OR=5.81, 95% CI=4.32, 7.81) higher of experiencing sexual assault and odds more than four times higher (OR=4.59, 95% CI=3.45, 6.09) of experiencing forced sex. Race/ethnicity and homelessness prior to age 18 years were not significantly associated with experiencing sexual assault or forced sex in the multivariable models.

Table 2.

Predictors of Sexual Assault and Forced Sex in Multivariable Logistic Regression

| Group | Sexual assault | Forced sex | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | |

| Cisgender womena | 1.92 | 1.40, 2.63 | 2.41 | 1.78, 3.27 |

| LGBQb | 1.82 | 1.33, 2.47 | 1.54 | 1.14, 2.08 |

| ≥2 years of homelessnessc | 1.49 | 1.08, 2.05 | 1.88 | 1.38, 2.55 |

| Childhood sexual abused | 5.81 | 4.32, 7.81 | 4.59 | 3.45, 6.09 |

ref, cisgender men.

ref, heterosexual.

ref, <2 years of homelessness.

ref, no childhood sexual assault.

LGBQ, lesbian, gay, bisexual, queer.

For youth who had been forced to have sex (24%, n=337), only 29% (n=98) had received a post-sexual assault examination. In bivariate analyses of utilization of post-sexual assault examination among those who were forced to have sex, race/ethnicity was the only demographic characteristic that was significantly associated with receiving an exam. Latinx youth had the highest percentage of exams (41.7%), whereas youth who identified as mixed race had the lowest (12.2%).

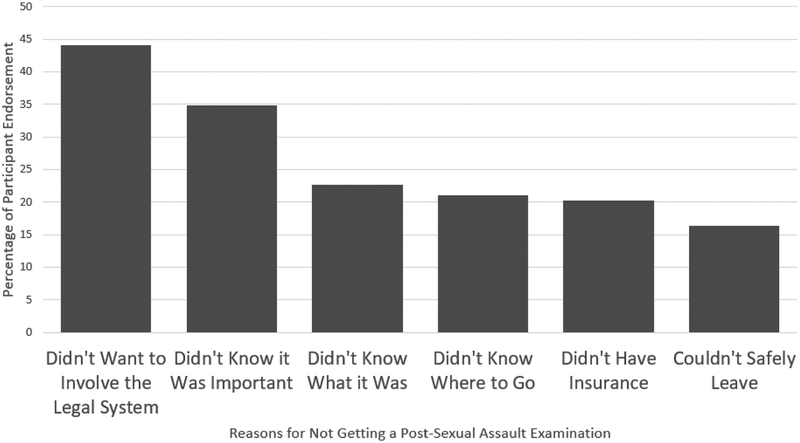

The 71% (n=238) of youth who had experienced forced sex but did not receive an exam were asked to endorse the reasons they did not get an exam (Table 3). Youth most frequently said they did not want to involve the legal system (44%) and that they did not think it was important (35%). In reasons, several significant associations were found. Youth who had experienced dating violence (p=0.02), engaged in trading sex (p=0.02), or who had been involved in the juvenile justice system (p=0.04) were significantly more likely to endorse not wanting to involve the legal system. Youth who had not experienced dating violence were significantly more likely to endorse that they did not know where to go for an exam (p<0.05). Those with a history of sex trafficking were more likely to endorse not seeking care because they could not safely leave the situation (p≤0.01). Those without a history of involvement with the juvenile justice system were more likely to endorse not knowing what a sexual assault exam was (p=0.03).

Table 3.

Number and Percentage Endorsing Reasons for Not Seeking a Post-Sexual Assault Examination, n=238

| Characteristic | Did not know where to go, n (%) | Could not safely leave the situation, n (%) | Did not know what a sexual assault exam was, n (%) | Did not think it was important, n (%) | Did not have health insurance, n (%) | Did not want to involve the legal system, n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Experienced dating violence | 4 (11.1)* | 5 (13.9) | 10 (27.8) | 16 (44.4) | 8 (22.2) | 21 (58.3)* |

| Experienced sex trafficking | 13 (68.4) | 15 (83.3)** | 10 (52.6) | 18 (52.9) | 7 (43.8) | 28 (57.1) |

| Traded sex | 20 (21.5) | 18 (19.4) | 19 (20.4) | 35 (37.6) | 16 (17.2) | 49 (52.7)* |

| Legal system involvement | ||||||

| Juvenile justice | 23 (27.1) | 16 (18.8) | 26 (30.6)* | 34 (40.0) | 16 (18.8) | 30 (35.3)* |

| Ever arrested | 2 (10.0) | 2 (10.0) | 4 (20.0) | 7 (35.0) | 8 (40.0)* | 13 (65) |

| Ever jailed | 14 (16.7) | 13 (15.5) | 19 (22.5) | 37 (44.0) | 20 (23.8) | 40 (47.6) |

| City | ||||||

| Los Angeles | 12 (28.6) | 3 (7.1) | 12 (28.6) | 14 (33.3) | 7 (16.7) | 19 (45.2) |

| Denver | 4 (15.4) | 2 (7.7) | 5 (19.2) | 13 (50.0) | 8 (30.8) | 16 (61.5) |

| Houston | 7 (22.6) | 6 (19.4) | 8 (25.8) | 8 (25.8) | 10 (32.3) | 10 (32.3) |

| Phoenix | 7 (16.7) | 10 (23.8) | 11 (26.2) | 15 (35.7) | 11 (26.2) | 20 (47.6) |

| St. Louis | 5 (19.2) | 6 (23.1) | 7 (26.9) | 8 (30.8) | 4 (15.4) | 9 (34.6) |

| New York City | 7 (19.4) | 6 (16.7) | 8 (22.2) | 11 (30.6) | 5 (13.9) | 19 (52.8) |

| San Jose | 8 (22.9) | 6 (16.4) | 3 (8.6) | 14 (34.9) | 3 (8.6) | 12 (34.3) |

Note: Boldface indicates statistical significance (*p≤0.05, **p≤0.01).

DISCUSSION

This study provides novel data from a regionally diverse sample of youth experiencing homelessness to increase the understanding of the prevalence of sexual violence and barriers and facilitators to receiving post-assault care. Findings align with evidence that young adults experiencing homelessness are at high risk for sexual assault with even higher-risk subgroups, including cisgender women, LGBQ youth, and transgender/gender expansive youth.1,4,5 In addition, data suggest higher risks among those with a longer duration of homelessness, earlier onset of homelessness, those who experienced sex trafficking, and youth who had engaged in trade sex. Considering transgender individuals may experience longer durations of homelessness than their cisgender counterparts and are more likely to engage in trade sex, they are especially vulnerable to sexual assault.32,33

Despite the high prevalence of sexual violence, nearly two thirds of youth who were forced to have sex did not get needed care, representing a critical gap in healthcare delivery. There are several reasons youth may not seek care after experiencing sexual assault. Similar to other findings, many youth are not getting an exam owing to reluctance to involve the legal system, mistrust, and stigma.34–38 Transgender/gender expansive youth may fear denial of treatment, an experience that is not uncommon among transgender individuals given structural barriers and stigma found in systems of care.39,40 Additionally, these findings suggest that many youth experiencing homelessness were not aware of the importance and availability of post-sexual assault care.41 Further, youth experiencing homelessness often lack access to healthcare services.24 Complicating access to care, the majority of the sexual assault nurse examiner programs in the U.S. are located in an emergency department, which may further limit the availability of services for those not seeking emergency services.42

Young people face significant barriers to seeking care following a sexual assault. These findings highlight the need for targeted programs that address these barriers (e.g., knowledge about services, concerns about safety, and fear related to disclosure to law enforcement also found in the literature43). Supports are needed to ensure access to services (e.g., victims assistance programs, transportation, community-located Sexual Assault Nurse Examiner [SANE] services). Youth experiencing dating violence, those who have traded sex, and youth who have had prior involvement with the juvenile justice system are less likely to seek post-sexual assault care and would benefit from targeted prevention programs that address the importance of health seeking. Post-assault care should be incorporated into sexual health programs serving youth experiencing homelessness and healthcare delivery systems need to adopt point-of-contact, comprehensive, post-sexual assault care delivery models.

A comprehensive strategy is needed that builds on health seeking facilitators while reducing barriers. For example, programs must reach healthcare providers, law enforcement, and homeless youth services providers to increase knowledge of the importance of seeking post-sexual assault care and facilitate access to care without requiring involvement of the legal system. Programs to educate youth delivered at drop-in centers and shelters can help walk youth through the process of seeking post-sexual assault care. Peer navigators and small group discussion may be ideal for increasing post-assault healthcare seeking given the mistrust and stigma many youth experience and the protective nature of social support.9,34,35,44

Missing or delaying post-sexual assault care can lead to negative physical (e.g., HIV, untreated STIs, unintended pregnancy), emotional (e.g. distress, depression, suicide), and social outcomes (e.g. substance dependence and treatment).26 Yet, post-assault care is most often available through an emergency department, which can reduce access to services.42 Though post-assault treatment is complex and involves medical, psychological, and legal services, the majority (86%) of providers of post-assault care are not SANEs.45 Therefore, there is a need for: (1) increased post-sexual assault care training among the healthcare workforce, (2) expansion of SANE programs, and (3) novel community-based delivery models to provide education and increase access to post-sexual assault examination as a prevention strategy for HIV, STIs, and unintended pregnancy. By increasing the SANE workforce and service delivery modalities, cities may decrease the barrier found in this data that youth did not know where to go for an exam. Additionally, increasing the availability of SANEs may decrease mistrust, stigma, and the fear of involving the legal system.46,47 One way to do this may be to partner mobile sexual assault response teams with healthcare and social service providers for youth experiencing homelessness.

Limitations

There are limitations to consider when interpreting the findings. This cross-sectional study did not examine differences between subgroups within different sexual orientations and gender identities and there may be differences between these groups. Future studies will examine these differences specifically focused on these subgroups. The survey did not ask whether those who wanted post-sexual assault care were able to access it and therefore the authors are unable to distinguish those who wanted care but could not get it from those who did not desire care. Also, the survey did not assess if those who received a post-sexual assault examination were offered HIV prevention medication or emergency contraception, nor if they adhered to that treatment regimen. Future studies would benefit from exploring these questions.

CONCLUSIONS

Youth experiencing homelessness are at elevated risk for sexual assault, yet underutilize post-sexual assault healthcare services that greatly reduce the risk for HIV and unintended pregnancy. SANEs and Forensic Nurses are uniquely positioned to respond to youth after a sexual assault and can dramatically and positively influence their immediate and long-term outcomes.48 Yet, homeless youth are largely unaware of the need for and process of accessing post-sexual assault services. Further efforts are needed to address this gap in HIV and pregnancy prevention; promote awareness of, access to, and training in post-sexual assault services; and recognize the need to treat sexual assault using non-stigmatizing, youth-friendly healthcare delivery models.14 Interventions to address barriers identified in this study such as lack of knowledge, fear, and stigma are critically needed. Finally, further examination into the lived experience of post-sexual assault health seeking and service utilization are needed to improve upon existing services.

Figure 1.

Percentage endorsed: reasons for not getting a post-sexual assault examination (n=238).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the multiple REALYST.org community partners and young people who collaborated and participated in this study. This research received partial financial support from the Greater Houston Community Foundation Funders Together to End Homelessness (DSM and SN), NIH: F31MH108446 (RP), and Arizona State University Institute for Social Science Research (KF).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

No financial disclosures were reported by the authors of this paper.

REFERENCES

- 1.Smith SG, Chen J, Basile KC, et al. National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey (NISVS): 2010–2012 state report. www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pdf/NISVS-StateReportBook.pdf. Published 2017. Accessed September 25, 2019.

- 2.Tyler KA, Whitbeck LB, Hoyt DR, et al. Risk factors for sexual victimization among male and female homeless and runaway youth. J Interpers Violence. 2004;19(5):503–520. 10.1177/0886260504262961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Avegno J, Mills TJ, Mills LD. Sexual assault victims in the emergency department: analysis by demographic and event characteristics. J Emerg Med. 2009;37(3):328–334. 10.1016/j.jemermed.2007.10.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Walters M, Chen J, Breiding M. National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey 2010: Findings on Victimization by Sexual Orientation. . www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pdf/nisvs_sofindings.pdf. Published January 2013. Accessed September 25, 2019.

- 5.Langenderfer-Magruder L, Walls NE, Kattari SK, Whitfield DL, Ramos D. Sexual victimization and subsequent police reporting by gender identity among lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer adults. Violence Vict. 2016;31(2):320. 10.1891/0886-6708.vv-d-14-00082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Heerde JA, Hemphill SA. Sexual risk behaviors, sexual offenses, and sexual victimization among homeless youth a systematic review of associations with substance use. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2016;17(5):468–489. 10.1177/1524838015584371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Heerde JA, Scholes-Balog KE, Hemphill SA. Associations between youth homelessness, sexual offenses, sexual victimization, and sexual risk behaviors: a systematic literature review. Arch Sex Behav. 2015;44(1):181–212. 10.1007/s10508-014-0375-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kushel MB, Evans JL, Perry S, Robertson MJ, Moss AR. No door to lock: victimization among homeless and marginally housed persons. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163(20):2492–2499. 10.1001/archinte.163.20.2492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Heerde JA, Hemphill SA. The role of risk and protective factors in the modification of risk for sexual victimization, sexual risk behaviors, and survival sex among homeless youth: a meta- analysis. Journal of Investigative Psychology and Offender Profiling. 2017;14(2):150–174. 10.1002/jip.1473. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boyer CB, Greenberg L, Chutuape K, et al. Exchange of sex for drugs or money in adolescents and young adults: an examination of sociodemographic factors, HIV-related risk, and community context. J Community Health. 2017;42(1):90–100. 10.1007/s10900-016-0234-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hudson AL, et al. Correlates of adult assault among homeless women. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2010;21(4):1250–1262. 10.1353/hpu.2010.0931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.De Vries I, Goggin KE. The impact of childhood abuse on the commercial sexual exploitation of youth: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Trauma Violence Abuse. In press. Online October 10, 2018. 10.1177/1524838018801332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Meinbresse M, Brinkley-Rubinstein L, Grassette A, et al. Exploring the experiences of violence among individuals who are homeless using a consumer-led approach. Violence Vict. 2014;29(1):122–136. 10.1891/0886-6708.vv-d-12-00069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zinzow HM, Resnick HS, Barr SC, Danielson CK, Kilpatrick DG. Receipt of post-rape medical care in a national sample of female victims. Am J Prev Med. 2012;43(2):183–187. 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.02.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Resnick H, Monnier J, Seals B, et al. Rape-related HIV risk concerns among recent rape victims. J Interpers Violence. 2002;17(7):746–759. 10.1177/0886260502017007003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McFarlane J, Malecha A, Watson K, et al. Intimate partner sexual assault against women: frequency, health consequences, and treatment outcomes. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105(1):99–108. 10.1097/01.aog.0000146641.98665.b6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Black M, Basile KC, Breiding MJ, et al. National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey: 2010 Summary Report. www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pdf/nisvs_executive_summary-a.pdf. Published 2011. Accessed September 25, 2019.

- 18.CDC. Updated guidelines for antiretroviral postexposure prophylaxis after sexual, injection drug use, or other nonoccupational exposure to HIV—United States, 2016. Ann Emerg Med. 2016;68(3):335–338. 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2016.06.028. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Seña AC, Hsu KK, Kellogg N, et al. Sexual assault and sexually transmitted infections in adults, adolescents, and children. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;61(Suppl 8):S856–S864. 10.1093/cid/civ786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Walsh K, Zinzow HM, Badour CL, Ruggiero KJ, Kilpatrick DG, Resnick HSet al. Understanding disparities in service seeking following forcible versus drug-or alcohol-facilitated/incapacitated rape. J Interpers Violence. 2016;31(14):2475–2491. 10.1177/0886260515576968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chu AT, DePrince AP, Mauss IB. Exploring revictimization risk in a community sample of sexual assault survivors. J Trauma Dissociation. 2014; 15(3):319–331. 10.1080/15299732.2013.853723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Patterson D, Greeson M, Campbell R. Understanding rape survivors’ decisions not to seek help from formal social systems. Health Soc Work. 2009;34(2):127–136. 10.1093/hsw/34.2.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Du Mont J, Macdonald S, White M, Turner L. Male victims of adult sexual assault: a descriptive study of survivors’ use of sexual assault treatment services. J Interpers Violence. 2013;28(13):2676–2694. 10.1177/0886260513487993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Society for Adolescent Health and Medicine. The healthcare needs and rights of youth experiencing homelessness. J Adolesc Health. 2018;63(3):372–375. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2018.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Society for Adolescent Health and Medicine. Advocating for adolescent and young adult male sexual and reproductive health: a position statement from the Society for Adolescent Health and Medicine. J Adolesc Health. 2018;63(5):657–661. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2018.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wenzel SL, Leake BD, Gelberg L. Health of homeless women with recent experience of rape. J Gen Intern Med. 2000;15(4):265–268. 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2000.015004265.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Narendorf SC, Santa Maria DM, Ha Y, Cooper J, Schieszler C. Counting and surveying homeless youth: recommendations from YouthCount 2.0!, a community–academic partnership. J Community Health. 2016;41(6):1234–1241. 10.1007/s10900-016-0210-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Murphy PW, Davis TC, Long SW, Jackson RH, Decker BC. Rapid estimate of adult literacy in medicine (REALM): a quick reading test for patients. Journal of Reading. 1993:124–130. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Protection Patient and Affordable Care Act, 42 U.S.C. § 18001 et seq. (2010).Runaway and homeless youth program authorizing legislation. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Peters CM, et al. Extending foster care to age 21: weighing the costs to government against the benefits to youth. Chapin Hill Issue Brief, www.kvc.org/wp-content/themes/KVC/sugargrove/files/Chapin_Hall_Report.pdf.Published June 2009. Accessed September 25, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Felitti VJ, et al. Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults: the Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. Am J Prev Med. 1998;14(4):245–258. 10.1016/S0749-3797(98)00017-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kattari SK, Walls NE, Speer SR. Differences in experiences of discrimination in accessing social services among transgender/gender nonconforming individuals by (dis) ability. J Soc Work Disabil Rehabil. 2017;16(2):116–140. 10.1080/1536710x.2017.1299661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Choi SK, Wilson BDM, Shelton J, Gates G. Serving our youth 2015: the needs and experiences of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and questioning youth experiencing homelessness. https://williamsinstitute.law.ucla.edu/wp-content/uploads/Serving-Our-Youth-June-2015.pdf. Published June 2015. Accessed September 25, 2019.

- 34.Collins P, Barker C. Psychological help-seeking in homeless adolescents. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2009;55(4):372–384. 10.1177/0020764008094430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bender K, Thompson SJ, McManus H, Lantry J, Flynn PM. Capacity for survival: exploring strengths of homeless street youth. Child Youth Care Forum. 2007;36(1):25–42. 10.1007/s10566-006-9029-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jones JS, Alexander C, Wynn BN, Rossman L, Dunnuck C. Why women don’t report sexual assault to the police: the influence of psychosocial variables and traumatic injury. J Emerg Med. 2009;36(4):417–424. 10.1016/j.jemermed.2007.10.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Thompson M, Sitterle D, Clay G, Kingree J. Reasons for not reporting victimizations to the police: Do they vary for physical and sexual incidents? J Am Coll Health. 2007;55(5):277–282. 10.3200/jach.55.5.277-282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Campbell R, Wasco SM, Ahrens CE, Sefl T, Barnes HE. Preventing the “second rape”: rape survivors’ experiences with community service providers. J Interpers Violence. 2001;16(12):1239–1259. 10.1177/088626001016012002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shelton J. Transgender youth homelessness: understanding programmatic barriers through the lens of cisgenderism. Children Youth Serv Rev. 2015;59:10–18. 10.1016/j.childyouth.2015.10.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.James S, Herman JL, Rankin S, Keisling M, Mottet L, Anafi M. The report of the 2015 U.S. transgender survey. www.transequality.org/sites/default/files/docs/USTS-Full-Report-FINAL.PDF. Published 2016. Accessed September 25, 2019.

- 41.Logan T, Evans L, Stevenson E, Jordan CE. Barriers to services for rural and urban survivors of rape. J Interpers Violence. 2005;20(5):591–616. 10.1177/0886260504272899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Draughon JE, Anderson JC, Hansen BR, Sheridan DJ. Nonoccupational postexposure HIV prophylaxis in sexual assault programs: a survey of SANE and FNE program coordinators. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2014;25(1):S90–S100. 10.1016/j.jana.2013.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hudson AL, Nyamathi A, Greengold B, et al. Health-seeking challenges among homeless youth. Nursing Res. 2010;59(3):212–218. 10.1097/NNR.0b013e3181d1a8a9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Barman-Adhikari A, Bowen E, Bender K, Brown S, Rice E. A social capital approach to identifying correlates of perceived social support among homeless youth. Child Youth Care Forum. 2016;45(5):691–708. 10.1007/s10566-016-9352-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nielson MH, Strong L, Stewart JG. Does sexual assault nurse examiner (SANE) training affect attitudes of emergency department nurses toward sexual assault survivors? J Forensic Nurs. 2015; 11(3):137–143. 10.1097/jfn.0000000000000081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Campbell R, Patterson D, Adams AE, Diegel R, Coats S. A participatory evaluation project to measure SANE nursing practice and adult sexual assault patients’ psychological well- being. J Forensic Nurs. 2008;4(1):19–28. 10.1111/j.1939-3938.2008.00003.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ericksen J, Dudley C, McIntosh G, Ritch L, Shumay S, Simpson M. Clients’ experiences with a specialized sexual assault service. J Emerg Nurs. 2002;28(1):86–90. 10.1067/men.2002.121740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Campbell R, Patterson D, Lichty LF. The effectiveness of sexual assault nurse examiner (SANE) programs: a review of psychological, medical, legal, and community outcomes. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2005;6(4):313–329. 10.1177/1524838005280328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]