Abstract

BACKGROUND

von Hippel-Lindau disease–associated hemangioblastomas (HBs) account for 20%–30% of all HB cases, with the appearance of new lesions often observed in the natural course of the disease. By comparison, the development of new lesions is rare in patients with sporadic HB.

OBSERVATIONS

A 65-year-old man underwent clipping for an unruptured aneurysm of the anterior communicating artery. Fourteen years later, follow-up magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed a strongly enhanced mass in the right cerebellar hemisphere, diagnosed as a sporadic HB. A retrospective review of MRI studies obtained over the follow-up period revealed the gradual development of peritumoral edema and vascularization before mass formation.

LESSONS

Newly appearing high-intensity T2 lesions in the cerebellum may represent a preliminary stage of tumorigenesis. Careful monitoring of these patients would be indicated, which could provide options for early treatment to improve patient outcomes.

Keywords: hemangioblastoma, von Hippel-Lindau disease, sporadic hemangioblastoma

ABBREVIATIONS: BEV = bevacizumab, CNS = central nervous system, DASE = developmentally arrested structural element, HB = hemangioblastoma, HIF = hypoxia-inducible factor, MRI = magnetic resonance imaging, SCA = superior cerebellar artery, SRS = stereotactic radiosurgery, VEGF = vascular endothelial growth factor, vHL = von Hippel-Lindau

Hemangioblastomas (HBs) are rare hypervascularized tumors that most commonly occur in the cerebellum. Sporadic HB accounts for 70%–80% of all HBs, with the remaining cases associated with von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) disease.1 Although both types of HBs are associated with VHL mutations, their histological cellular origins remain unclear. Although newly developed HBs and tumor progression have been reported in patients with a long-term natural history of VHL disease, the identification of new lesions in sporadic HB is extremely rare, especially in elderly patients. Herein, we present a rare case of newly developed sporadic HB. The process of tumorigenesis for this rare HB was visually captured on images obtained over the follow-up period after intracranial aneurysm clipping.

Illustrative Case

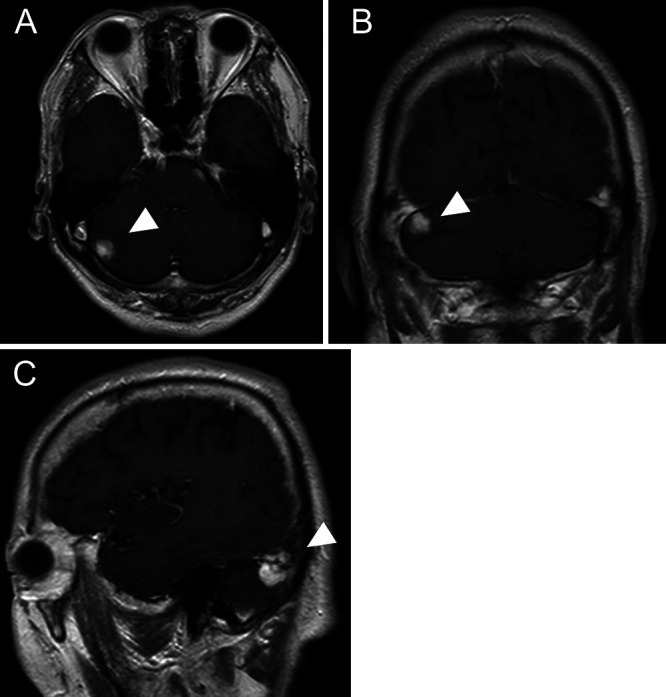

A 65-year-old man with a history of lung adenocarcinoma was diagnosed with an unruptured aneurysm of the anterior communicating artery, which was treated with surgical clipping at our department. The patient was subsequently referred to a nearby hospital for follow-up on an outpatient basis, including annual examination with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Fourteen years postoperatively, the patient presented with mild ataxia. MRI revealed an intraaxial, heterogeneous, and strongly enhanced mass lesion (16 × 12 × 16 mm) in the right cerebellar hemisphere, with peritumoral edema (Fig. 1). The patient was referred to our hospital for diagnosis and management. We retrospectively reviewed the MRI studies obtained during the 14-year follow-up period, which revealed the presence of a peritumoral T2/fluid-attenuated inversion recovery high-intensity lesion, visible 4 years before the mass lesion was identified (Fig. 2). In addition, the right superior cerebellar artery (SCA), which was the main feeder to the tumor, showed gradual delineation on magnetic resonance angiography and three-dimensional computed tomography angiography (Fig. 3). Although the patient was 79 years of age, tumor resection was performed to obtain a precise pathological diagnosis, considering his prior history of lung adenocarcinoma.

FIG. 1.

Preoperative axial (A), coronal (B), and sagittal (C) contrast-enhanced T1-weighted MRI showing a strongly enhanced mass lesion (arrowheads) in the right cerebellar hemisphere.

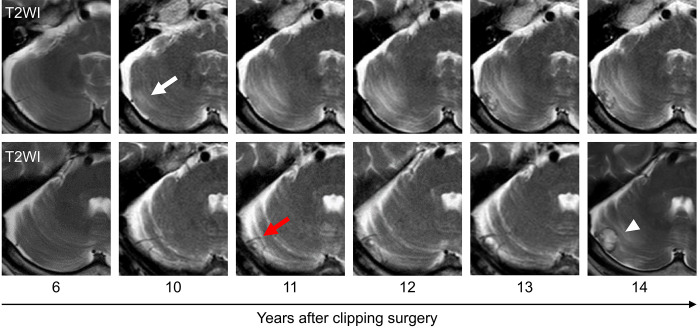

FIG. 2.

Time series of axial T2-weighted MRI (T2WI) showing the appearance of peritumoral edema (white arrow) and vascularization (red arrow) before mass formation (white arrowhead).

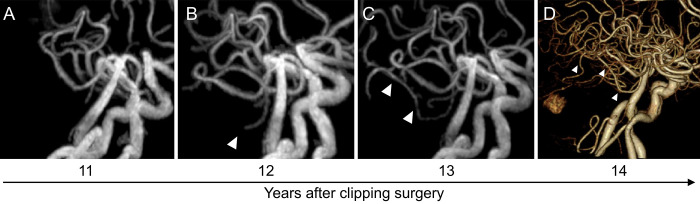

FIG. 3.

Time series of magnetic resonance angiography (A–C) and three-dimensional computed tomography angiography (D) showing the development of the right SCA (arrowheads) as a main feeder of the tumor.

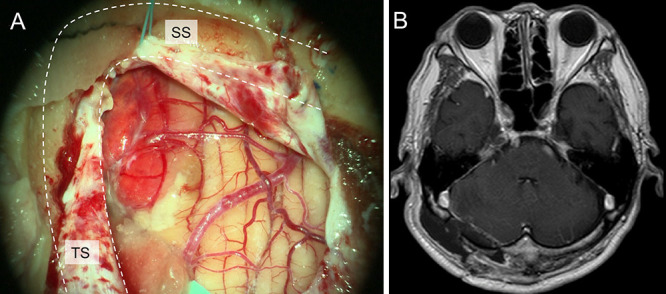

The surgery was performed with the patient in the park bench position and under general anesthesia. A lateral suboccipital craniotomy was performed. After dural incision, a reddish tumor was identified on the surface of the cerebellar hemisphere (Fig. 4A). The boundary between normal brain tissue and the tumor was clear, and the small feeders from the SCA branches were cauterized and dissected (Fig. 4B). The tumor was completely resected.

FIG. 4.

A: Intraoperative photograph showing a reddish tumor on the surface of the cerebellar hemisphere after dural incision. B: Postoperative gadolinium-enhanced T1-weighted MRI confirming complete removal of the tumor. SS = sigmoid sinus; TS = transverse sinus.

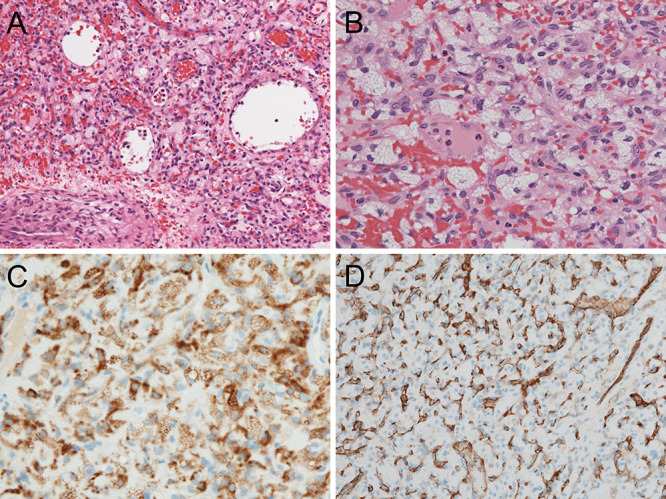

Histopathological examination of the resected tumor revealed abundant capillaries and stromal tumor cells. The cytoplasm of the tumor cells was filled with lipid-laden vacuoles. Immunohistological staining was positive for inhibin-α and CD31 (Fig. 5A–D). The diagnosis of sporadic HB was based on the absence of a family history of VHL disease, no evidence of VHL-associated lesions other than the central nervous system (CNS) lesions, and pathological findings. The postoperative course was uneventful with no neurological deficits; the patient was discharged on postoperative day 10.

FIG. 5.

Histopathological examination of the resected tumor. A: Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining, original magnification ×100. B: H&E staining, original magnification ×400. C: Inhibin-α stain, original magnification ×200. D: CD31 stain, original magnification ×200.

Patient Informed Consent

The necessary patient informed consent was obtained in this study.

Discussion

Observations

HBs are benign, highly vascular neoplasms of the CNS, accounting for 1.5%–2.5% of all intracranial tumors and 7%–12% of posterior fossa tumors.2 They most often involve the cerebellum (45%–50%), followed by the spinal cord (40%–45%) and brainstem (5%–10%).2

Approximately 20%–30% of HBs are associated with VHL disease. Patients with VHL disease commonly seek treatment in their 20s or 30s, with 70%–84% of patients exhibiting new CNS HBs, with the highest rate of progression in the 30s (0.4 new tumors/yr/patient).3,4 By comparison, patients with sporadic HBs typically seek treatment in their 40s–50s, when tumors have reached a size that causes symptoms due to the mass effect related to enlarging cysts or peritumoral edema and obstructive hydrocephalus. The appearance of newly developed CNS lesions during the natural course of sporadic HB is rare, except for a local recurrence, especially in older adults, as in our case.2

HBs are histologically characterized by a combination of stromal cells and highly vascularized networks. However, the pathogenesis of HB remains unclear. Embryologically, arrested hemangioblasts have been reported as the likely source of HBs for decades, as evidenced by hematopoietic and endothelial differentiation, although the mechanisms mediating angiogenesis have not been fully explained.5,6 Ma et al.7 reported that tumor cells expressing stage-specific embryonic antigen-1, a carbohydrate adhesion molecule distributed in the CNS, retain multipotent properties to differentiate into not only stromal cells but also vascular cells in the presence of the HB niche. Shively et al.8 examined the normal cerebellum of patients with VHL disease and identified developmentally arrested structural elements (DASEs) in the molecular layers of the cerebellar cortex, where 75% of cerebellar HBs occur. On the basis of the structural similarities between DASEs and HBs, Shively et al. suggested that VHL deficiency leads to the developmental arrest of basket/stellate cells in DASEs, which have the potential to differentiate into HBs.

Although the histological origin of HBs is still debated, the genetic and molecular backgrounds of HBs have been elucidated. VHL-related HBs are typically induced by biallelic inactivation of the VHL gene on chromosome 3, germline mutations in the first allele, and subsequent somatic mutation or loss of the second allele.9 More recently, it has been revealed that 62%–78% of sporadic HBs also harbor these VHL alterations, with epigenetic suppression as another mechanism of VHL inactivation in sporadic HBs.10,11

The VHL protein mediates the ubiquitylation and degradation of hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF)-1α, a transcription factor that plays a crucial role in the cellular adaptive response under hypoxic conditions. Inactivation of the VHL gene results in oxygen-independent accumulation of HIF-1α; activating genes associated with angiogenesis, cell survival, invasion and metastasis of the tumor; and contributing to the adaptation of the tumor to hypoxic conditions.12,13 Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) is a representative mediator of tumor angiogenesis by upregulating HIF-1α expression. VEGF binds to endothelial cells via the tyrosine kinase receptors Fily-1 (VEGFR-1) and KDR/Flk-1 (VEGFR-2) and enhances endothelial mitogenesis and chemotaxis. The VEGF-induced vasculature in HB exhibits both structural and functional abnormalities.14 VEGF also acts on the vascular endothelial junction by inducing phosphorylation-dependent ubiquitination of occludin, a key transmembrane protein of the blood–brain barrier. Fenestration of cell–cell junctions increases vascular permeability and causes vasogenic edema.15,16 Importantly, in our case, a T2 high-intensity lesion was identified on MRI before the development of the feeding artery and tumor formation (Figs. 2 and 3). The lesion also showed high apparent diffusion coefficient values, suggesting that these images most likely captured vasogenic edema as an initial change in HB formation.17

Although complete resection is deemed the most effective treatment for symptomatic HBs located in the cerebellum, safe resection is not always possible because of either the location of the tumor or its high vascularity.1 As a second option, stereotactic radiosurgery (SRS) has demonstrated safety and efficacy for intracranial HBs, especially for small tumors and VHL disease–associated HBs.18 However, SRS is not indicated for asymptomatic tumors, because SRS is associated with a lower local control rate over the long term than that with resection.19 Although the tumor in our patient was small and suitable for SRS, we proceeded with resection because symptoms were very mild and there was a possibility of brain metastasis from lung cancer. Furthermore, preoperative imaging indicated that safe tumor removal was possible because the tumor was located on the cerebellar surface. The patient showed favorable postoperative progress.

Other promising future treatment options for HBs include bevacizumab (BEV) and belzutifan, which are humanized monoclonal anti-VEGF antibodies and small-molecule inhibitors of HIF-2α, respectively. On the basis of the molecular background of HB tumorigenesis, blockade of the VEGF-VEGFR pathway using BEV may be a good option for preventing tumor growth. Several case reports have illustrated the efficacy of BEV in patients with HBs after the failure of surgery and SRS; however, these outcomes remain to be validated in randomized controlled trials. Belzutifan was recently approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of patients with VHL disease–associated CNS HBs, renal cell carcinoma, and pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors.20,21 Although Neth et al.22 demonstrated the safety and tolerance of belzutifan for CNS HBs, with favorable responses in patients with VHL disease, fatal intracranial hemorrhage has also been reported as an adverse effect of belzutifan.23 Therefore, further accumulation of cases is essential to accurately assess the benefits of BEV and belzutifan treatment.

Lessons

Herein, we report a case of newly developed sporadic HB in the cerebellum for which a retrospective review of MRI studies obtained over the 14-year follow-up revealed early tissue and vascular signs of the process of tumorigenesis. Although an accumulation of similar cases is needed to determine whether the characteristics of the images captured in our case can be applied to other cases, our case underlines the possibility of the preneoplastic formation of sporadic HBs as one of the differential diagnoses of a newly appearing high-intensity T2-weighted imaging lesion in the cerebellum.

Acknowledgments

We thank Kanamaru Clinic for Cerebrospinal Surgery for providing detailed patient information.

Author Contributions

Conception and design: Kuramitsu, Sugiyama, Matsuno, Maesawa. Acquisition of data: Sugiyama, Ito, Ando, Suzaki. Analysis and interpretation of data: Sugiyama. Drafting the article: Kuramitsu, Sugiyama. Critically revising the article: Kuramitsu, Sugiyama, Ito, Maesawa. Reviewed submitted version of manuscript: Kuramitsu, Sugiyama, Eguchi, Ito, Suzaki. Approved the final version of the manuscript on behalf of all authors: Kuramitsu. Administrative/technical/material support: Matsuno, Suzaki. Study supervision: Kuramitsu, Ando, Maesawa.

References

- 1. Neumann HP, Eggert HR, Weigel K, Friedburg H, Wiestler OD, Schollmeyer P. Hemangioblastomas of the central nervous system. A 10-year study with special reference to von Hippel-Lindau syndrome. J Neurosurg. 1989;70(1):24–30. doi: 10.3171/jns.1989.70.1.0024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Yin X, Duan H, Yi Z, Li C, Lu R, Li L. Incidence, prognostic factors and survival for hemangioblastoma of the central nervous system: analysis based on the surveillance, epidemiology, and end results database. Front Oncol. 2020;10:570103. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2020.570103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lonser RR, Butman JA, Huntoon K, et al. Prospective natural history study of central nervous system hemangioblastomas in von Hippel-Lindau disease. J Neurosurg. 2014;120(5):1055–1062. doi: 10.3171/2014.1.JNS131431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Binderup ML, Budtz-Jørgensen E, Bisgaard ML. Risk of new tumors in von Hippel-Lindau patients depends on age and genotype. Genet Med. 2016;18(1):89–97. doi: 10.1038/gim.2015.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Gläsker S, Li J, Xia JB, et al. Hemangioblastomas share protein expression with embryonal hemangioblast progenitor cell. Cancer Res. 2006;66(8):4167–4172. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-3505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Park DM, Zhuang Z, Chen L, et al. von Hippel-Lindau disease- associated hemangioblastomas are derived from embryologic multipotent cells. PLoS Med. 2007;4(2):e60. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ma D, Zhang M, Chen L, et al. Hemangioblastomas might derive from neoplastic transformation of neural stem cells/progenitors in the specific niche. Carcinogenesis. 2011;32(1):102–109. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgq214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Shively SB, Edwards NA, MacDonald TJ, et al. Developmentally arrested basket/stellate cells in postnatal human brain as potential tumor cells of origin for cerebellar hemangioblastoma in von Hippel-Lindau patients. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2022;81(11):885–899. doi: 10.1093/jnen/nlac073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Gläsker S, Bender BU, Apel TW, et al. Reconsideration of biallelic inactivation of the VHL tumour suppressor gene in hemangioblastomas of the central nervous system. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2001;70(5):644–648. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.70.5.644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Takayanagi S, Mukasa A, Tanaka S, et al. Differences in genetic and epigenetic alterations between von Hippel-Lindau disease- related and sporadic hemangioblastomas of the central nervous system. Neuro Oncol. 2017;19(9):1228–1236. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nox034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Shankar GM, Taylor-Weiner A, Lelic N, et al. Sporadic hemangioblastomas are characterized by cryptic VHL inactivation. Acta Neuropathol Commun. 2014;2:167. doi: 10.1186/s40478-014-0167-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Semenza GL. HIF-1 and tumor progression: pathophysiology and therapeutics. Trends Mol Med. 2002;8(4) suppl:S62–S67. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4914(02)02317-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. McGettrick AF, O’Neill LAJ. The role of HIF in immunity and inflammation. Cell Metab. 2020;32(4):524–536. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2020.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Davies DC. Blood-brain barrier breakdown in septic encephalopathy and brain tumours. J Anat. 2002;200(6):639–646. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-7580.2002.00065.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Antonetti DA, Barber AJ, Hollinger LA, Wolpert EB, Gardner TW. Vascular endothelial growth factor induces rapid phosphorylation of tight junction proteins occludin and zonula occluden 1. A potential mechanism for vascular permeability in diabetic retinopathy and tumors. J Biol Chem. 1999;274(33):23463–23467. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.33.23463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Murakami T, Felinski EA, Antonetti DA. Occludin phosphorylation and ubiquitination regulate tight junction trafficking and vascular endothelial growth factor-induced permeability. J Biol Chem. 2009;284(31):21036–21046. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.016766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Solar P, Hendrych M, Barak M, Valekova H, Hermanova M, Jancalek R. Blood-brain barrier alterations and edema formation in different brain mass lesions. Front Cell Neurosci. 2022;16:922181. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2022.922181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kano H, Shuto T, Iwai Y, et al. Stereotactic radiosurgery for intracranial hemangioblastomas: a retrospective international outcome study. J Neurosurg. 2015;122(6):1469–1478. doi: 10.3171/2014.10.JNS131602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Asthagiri AR, Mehta GU, Zach L, et al. Prospective evaluation of radiosurgery for hemangioblastomas in von Hippel-Lindau disease. Neuro Oncol. 2010;12(1):80–86. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nop018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Jonasch E, Donskov F, Iliopoulos O, et al. Belzutifan for renal cell carcinoma in von Hippel-Lindau disease. N Engl J Med. 2021;385(22):2036–2046. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2103425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Fallah J, Brave MH, Weinstock C, et al. FDA approval summary: belzutifan for von Hippel-Lindau disease-associated tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2022;28(22):4843–4848. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-22-1054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Neth BJ, Webb MJ, White J, Uhm JH, Pichurin PN, Sener U. Belzutifan in adults with VHL-associated central nervous system hemangioblastoma: a single-center experience. J Neurooncol. 2023;164(1):239–247. doi: 10.1007/s11060-023-04395-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Saeed Z, Tasleem A, Asthagiri A, Schiff D, Jo J. Fatal intracranial hemorrhage with belzutifan in von Hippel-Lindau disease-associated hemangioblastoma: A case report. JCO Precis Oncol. 2023;7:e2300066. doi: 10.1200/PO.23.00066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]