Abstract

Objective:

To analyze Clostridioides difficile testing in 3 hospitals in central North Carolina to validate previous racial health-disparity findings.

Methods:

We completed a retrospective analysis of inpatient C. difficile tests from 2015 to 2021 at 3 university-affiliated hospitals in North Carolina. We calculated the number of C. difficile tests per 1,000 patient days stratified by race: White, Black, and non-White, non-Black (NWNB). We defined a unique C. difficile test as one that occurred in an inpatient unit with a matching laboratory accession ID and on differing calendar days. Tests were evaluated overall, by hospital, by year, and by positivity rate.

Results:

In total, 35,160 C. difficile tests and 2,571,850 patient days across all 3 hospitals from 2015 to 2021 were analyzed. The median number of C. difficile tests per 1,000 patient days was 13.85 (interquartile range [IQR], 9.88–16.07). Among all C. difficile tests, 5,225 (15%) were positive. White patients were administered more C. difficile tests (14.46 per 1,000 patient days) than Black patients (12.96; P < .0001) or NWNB race patients (10.27; P < .0001). Black patients were administered more tests than NWNB patients (P < .0001). White patients tested positive at a similar rate to Black patients (15% vs 15%; P = .3655) and higher than NWNB individuals (12%; P = .0061), and Black patients tested positive at a higher rate than NWNB patients (P = .0024).

Conclusion:

White patients received more C. difficile tests than Black and NWNB patient groups when controlling for race patient days. Future studies should control for comorbidities and investigate community onset of C. difficile by race and ethnicity.

Health equity is a priority for the Centers of Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 1 Non-White individuals experience poorer clinical outcomes, including higher rates of death, general illness, and chronic disease compared to their White counterparts. 2 Despite improvements over the past 2 decades, non-White individuals also have lower rates of healthcare access, including health insurance and healthcare utilization. 1 Individuals with lower access to care are at higher risk of adverse health outcomes. 3 Additional investigation is needed to understand healthcare disparities among minority and marginalized groups to improve equitable access to care.

Clostridioides difficile infection (CDI) is a bacterial infection of the colon (colitis) that can cause mild to life-threatening complications. CDI is one of the most common healthcare associated infections, affecting ∼450,000–500,000 people per year in the United States. 4,5 Symptoms vary from frequent diarrhea to sepsis, extreme dehydration, kidney failure, and potential death. 6 Many healthcare-associated factors increase the risk of CDI such as exposure to antibiotics (especially clindamycin, cephalosporins, and fluoroquinolones), proton-pump inhibitors, and hospitalization or nursing home exposure. 7 Because these risks all require healthcare exposure, those with increased access to healthcare are potentially at higher risk for CDI than those with less access to care. 8

Previous studies have included evidence of differing CDI risk between races and by healthcare access and utilization, with White individuals having higher exposure to C. difficile and receiving more tests. 9 However, these studies were based on error-prone hospital discharge surveys, and few studies have controlled for disproportionate time spent in the hospital between races.

We have built upon previous research by (1) validating prior studies’ findings using electronic health-record–level data and (2) control for disproportionate patient days between races using race-specific patient days.

Methods

Study population

We completed a retrospective cohort study of patients evaluated at 3 hospitals in the Duke University Health System. All hospitals were in urban regions in North Carolina. Hospital A, a 1,048-bed facility, is an academic medical center, whereas hospitals B (with 388 beds) and hospital C (with 186 beds) are academically affiliated hospitals. The analysis period was from January 1, 2015, through December 31, 2021.

Cohort participants included all inpatient hospital encounters as designated by National Healthcare Safety Network (NHSN) unit mapping. 10 We utilized electronic health records from all 3 hospitals; race data were self-reported, and patients were excluded if race was not listed or the respondent declined to answer.

Outcomes

We investigated C. difficile tests and proportions of positive tests by race overall, by hospital, and by year. Our primary outcome was the number of C. difficile tests administered by race per 1,000 race-specific patient days. Our secondary outcome was percent positivity by race.

Our analysis was conducted across all 3 hospitals from 2015 to 2021. Analyses were also conducted by hospital for every year and aggregate totals by hospital for the entire 6-year surveillance period.

Definitions

We defined patient days and inpatient unit locations per NHSN methods. 10 An inpatient encounter was defined as a unique encounter with exposure to an inpatient unit for at least 1 calendar day. Race outcomes were categorized into 3 groups: White, Black, and NWNB. Ethnicity was included in this surveillance database in 2021, resulting in a significant number of tests (32,443 or 92% of total tests) for which ethnicity was missing. As such, ethnicity was omitted from our analysis. Following the integration of ethnicity, only 85 (0.24%) of total tests occurred on patients who were Hispanic or Latino, and 2,546 tests (7%) were for non-Hispanic or Latino patients. The remaining patients, 86 (0.24%) of total tests, declined to report ethnicity but still reported race. The NWNB race group comprised individuals who identified as American Indian/Alaskan Native, Asian, Native Hawaiian/Other Pacific Islander, or Other.

Unique C. difficile tests were defined by laboratory accession numbers. PCR tests were used to identify C. difficile. All hospitals switched to a 2-step testing strategy to identify toxigenic C. difficile in March 2020, PCR followed by reflex toxin assay. For the purposes of this study, PCR tests were used for the entirety of the study period. Duplicate tests were defined as those occurring within 14 days of previous test or positive result according to the NHSN LabID Event Protocol. 12 We chose to include repeated tests because they made up a small proportion of our overall tests administered and served as yet another proxy for healthcare access.

Statistical approach

The analysis of study data grouped by race was tested for overall significance using the χ2 test of homogeneity followed by pairwise comparisons between each group using Bonferroni adjustments. Statistical comparisons between hospitals were not completed due to lack of statistical power. Other comparisons included χ2 for categorical variables and t tests for continuous (if normal) variables and Wilcoxon for continuous (nonnormal) variables.

All statistical tests were 2-tailed, and a P < .05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were completed using Stata version 17 software (StataCorp, College Station, TX). The Duke University Institutional Review Board reviewed and approved this study.

Results

Overall characteristics

In total, 35,160 C. difficile tests were obtained across the 3 hospitals from 2015 to 2021. Of these, 21,695 (62%) were administered to those who identified as White, 11,846 (34%) were administered to those who identified as Black, and 1,619 (5%) were administered to those who identified as NWNB (Table 1). Among the 5,225 positive tests, White patients had 3,222 positive tests (62%), Black patients had 1,803 positive tests (35%), and NWNB patients had 200 positive tests (4%). Across the total surveillance period, an aggregate of 2,571,850 patient days were included: 1,499,993 patient days (58%) were attributed to White patients, 914,228 (36%) were attributed to Black patients, and 157,629 (6%) were attributed to NWNB patients. Also, 118 C. difficile tests (0.34%), 60 positive tests (1.15%), and 69,863 patient days (2.6%) were excluded due to patient declining to report or no race reported. Duplicate tests made up for 9.64% of our total tests, and duplicate positive tests made up for <1% of our total positive tests.

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics by Race

| Characteristic | Overall | Black | White | NWNB |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, median y (IQR) | 63 (51–72) | 60 (48–69) | 65 (53–74) | 54 (39–67) |

| Sex, female | 18,374 | 6,385 | 11,267 | 722 |

| Length of stay, median d (IQR) | 10 (5–25) | 11 (5–24) | 10 (5–25) | 12 (5–30) |

| Clostridioides difficile tests | 35,160 | 11,846 | 21,695 | 1,619 |

| Positive C. difficile tests | 5,225 | 1,803 | 3,222 | 200 |

| Patient days | 2,571,850 | 914,228 | 1,499,993 | 157,629 |

Note. IQR, interquartile range.

Of the study hospitals, hospital A administered 25,007 tests (71% of tests in cohort) during 1,805,225 patient days (66% of patient days in cohort). Hospital B administered 6,691 (19%) tests during 416,352 patient days (16%). Hospital C administered 3,462 tests (10%) during 350,273 patient days (14%). Of C. difficile positive tests, hospital A had 3,428 (66%), hospital B had 1,202 (23%), and hospital C had 595 (11%).

The median age was 63 years (interquartile range [IQR], 51–72) of those receiving a C. difficile test and 64 years (IQR, 52–74) for those who tested positive for C. difficile. The median length of stay was 10 days (IQR, 5–25) for those who received a C. difficile test and 8 days (IQR, 5–18) for those who tested positive (Table 1).

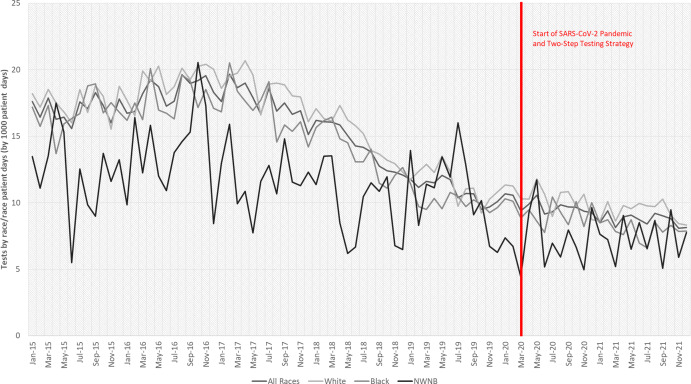

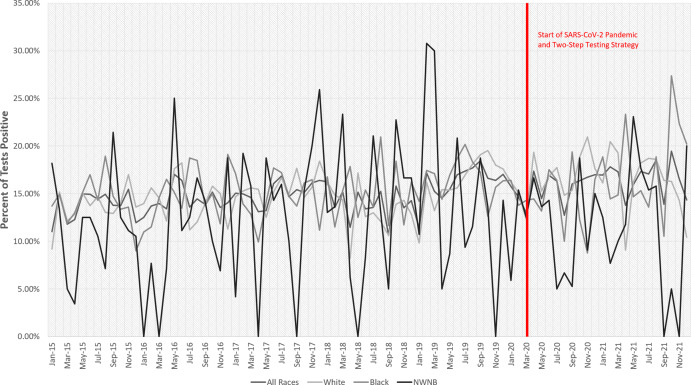

The total number of C. difficile tests administered per 1,000 race-specific patient days decreased between 2015 and 2021 (Fig. 1), which we also previously reported at our medical center with data over a shorter time frame that, contrary to this study, included C. difficile tests taken in the emergency department from patients who were not subsequently admitted. 11 Additionally, the positivity rate for C. difficile slightly increased between 2015 and 2021 (Fig. 2).

Figure 1.

C. difficile tests by race per 1,000 race patient days.

Figure 2.

Proportion of positive C. difficile test by patient race.

Primary analysis

When controlling for patient days by race, overall White patients were administered more C. difficile tests (14.46 per 1,000 patient days) than Black patients (12.96 per 1,000 patient days) and NWNB patients (10.27 per 1,000 patient days), and Black patients were administered more tests than NWNB patients (Table 2).

Table 2.

Clostridioides difficile Tests and Positivity by Race

| Variable | Overall | White | Black | NWNB |

P Value (WvB, WvNWNB, Bv NWNB) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C. difficile tests per 1,000 patient days | 13.67 | 14.46 | 12.96 | 10.27 | <.001, <.001, <.001 |

| Hospital A | 13.85 | 14.90 | 12.82 | 9.96 | <.001, <.001, <.001 |

| Hospital B | 16.07 | 16.73 | 15.44 | 14.77 | .001, .063, .512 |

| Hospital C | 9.88 | 10.16 | 9.57 | 8.45 | .102, .028, .153 |

| Positive C. difficile tests administered, No. (% positive) | 35,160 (15) | 21,695 (15) | 11,846 (15) | 1,619 (12) | .366, .006, .002 |

| Hospital A | 25,007 (14) | 15,936 (14) | 7,835 (14) | 1,236 (10) | .155, .001, <.001 |

| Hospital B | 6,691 (18) | 3,533 (19) | 2,925 (17) | 233 (19) | .133, .777, .396 |

| Hospital C | 3,462 (17) | 2,226 (17) | 1,086 (16) | 150 (19) | .455, .553, .366 |

Note. WvB, White versus Black patients; WvNWNB; White versus non-White non-Black patients, BvNWNB, Black versus non-White non-Black patients.

Similar outcomes were observed at the hospital level. At Hospital A, White patients had more C. difficile tests (14.90 per 1,000 patient days) than Black patients (12.82 per 1,000 patient days) and NWNB patients (9.96 per 1,000 patient days), and Black patients were administered more tests than NWNB patients. At hospital B, White patients (16.73 per 1,000 patient days) had more C. difficile tests administered than Black patients (15.44 per 1,000 patient days). Compared to both White and Black patients, those in the NWNB race category were administered fewer tests (14.77 per 1,000 patient days); however, this was not statistically significant. At hospital C, White patients (10.16 per 1,000 patient days) had more C. difficile tests administered than Black (9.57 per 1,000 patient days) and NWNB patients (8.45 per 1,000 patient days), and Black patients were administered more tests than NWNB patients, none of these rates were statistically significant (Table 2).

Percent positive

White patients (15%) tested positive at a similar rate to Black patients (15%) and higher than NWNB patients (12%), and Black patients tested positive at a higher rate than NWNB patients.

At hospital A, White patients (14%) tested positive at a similar rate to Black patients (14%) and higher than NWNB patients (10%), and Black patients tested positive at a higher rate than NWNB patients; however, the rate relationship between White and Black metrics lacked statistical significance. At hospital B, White patients (19%) tested positive at a higher rate than Black patients (17%) and a lower rate than NWNB patients (19%), and Black patients tested positive at a lower rate than NWNB patients; however, these results lacked significance. At hospital C, White patients (17%) tested positive at a higher rate than Black patients (16%) and a lower rate than NWNB patients (19%), and Black patients tested positive at a lower rate than NWNB patients; however, these results were not statistically significant.

Discussion

We analyzed potential racial health disparities of C. difficile testing in 3 southeastern US hospitals to validate previous studies and investigate possible disparities in healthcare access among different races. We observed higher rates of C. difficile testing among White patients relative to Black or NWNB patients across all 3 hospitals. Positivity rates were similar for Black and White patients and were slightly higher than for NWNB patients overall. Lower rates of C. difficile testing among Black inpatients despite similar overall prevalence rates for positives could be the result of inequity in testing or of a lower incidence of C. difficile disease among Black inpatients, which has been described in other studies. 8,9,11

Our primary analysis generated new insights in the field; previous studies have only investigated CDI discharge diagnosis and not CDI testing. In our study, testing differed by race, even when controlling for race-specific patient days. In our secondary analysis of C. difficile positivity rate by race, we detected no statistical significance between White and Black racial groups. Both White and Black groups had higher positivity rates than the NWNB racial group, but this finding was likely due to the small sample size in the NWNB racial group. Our primary analysis significantly differed from results from Argamany et al. 9 These investigators utilized the US National Hospital Discharge Survey and found CDI discharge diagnosis rate was higher in White patients than Black patients (7.7 vs 4.9 per 1,000 discharges; P < .0001). 9 Because Argamany et al verified cases by discharge summary (whereas we used clinical testing results) and did not use race specific discharges (whereas we used race specific patient days), direct comparisons were limited.

We observed an overall trend toward decreased C. difficile tests administered per 1,000 patient days across all 3 hospitals and all races. The decrease in testing likely reflects diagnostic stewardship efforts undertaken at each site aimed at improving CDI test utilization. In a previous analysis of our study hospitals, Karlovich et al 11 studied the impact of electronic health record (EHR)–based interventions and test restriction on C. difficile tests. They determined that (1) there was a significant decrease in C. difficile tests from 2017 to 2019 and (2) test restrictions were more effective than EHR-based interventions at reducing C. difficile tests. 11

Consistent with more targeted test utilization, we observed a slight increase in C. difficile positivity rate over the study period. However, we consider these findings to represent trends for hypothesis generation because we did not evaluate these data through statistical testing or modeling, only graphically (Figs. 1 and 2).

Our study had several limitations. First, hospital A administered 71% of study C. difficile tests and had 66% of the patient days, which had a large influence on the overall results and prevented us from assessing nested trends between hospitals. Second, we did not assess nor control for potential confounding comorbidities that may influence who receives a test that may also differ by race, such as underlying disease severity or where patients were admitted. Certain tests within our analysis may reflect the impact of comorbidities and chronic illness rather than racial differences. Third, all hospitals studied are academic affiliated institutions that are situated in urban regions, which reduces the generalizability of our results. Fourth, the database also shifted race and ethnicity definitions in 2021, at which time Hispanic was moved from a race to an ethnicity in our EHR. Hispanic fell under the race category of White prior to and after this change. We were not able to assess effects for Hispanic ethnicity despite this change in 2021, and it remained included in the White totals. However, Hispanics represented <1% of tests and positive results once introduced in 2021. This change may have led to a slight inflation of our C. difficile tests on White patients and positive results that otherwise would be attributed to Hispanics. Furthermore, race was self-reported, which may leave room for measurement error and a greater number of unknown and undefined race. Measurement error is a well-known limitation of data derived from electronic health records. However, our data still provide an important starting point in our efforts to better understand and improve equity in healthcare-associated infection prevention.

In conclusion, we observed lower rates of CDI testing among Black patients after adjustment for race-specific patient days and despite similar rates of test positivity across groups, which could be the result of inequity in testing or of a lower incidence of C. difficile disease among Black inpatients. Further research is needed to understand why this difference occurred, if this is geographically dependent, and if it results from differences in either access to care or in selection for testing. Further research should focus on controlling for comorbidities among those tested for C. difficile, on analyzing community onset versus healthcare-associated CDI by race group, and on assessing variables associated with access to care, which may also differ between inpatient and outpatient settings.

Acknowledgments

Financial support

No financial support was provided relevant to this article.

Competing interests

All authors report no conflicts of interest relevant to this article.

References

- 1. Mahajan S, Caraballo C, Lu Y, et al. Trends in differences in health status and healthcare access and affordability by race and ethnicity in the United States, 1999–2018. JAMA 2021;326:637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Racism and health. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. ∼https://www.cdc.gov/healthequity/racism-disparities/index.html#:∼:text=The%20data%20show%20that%20racial,compared%20to%20their%20White%20counterparts. Published November 24, 2021. Accessed October 30, 2023.

- 3. Hoffman C, Paradise J. Health insurance and access to health care in the United States. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2008;1136:149–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clostridioides difficile infection (CDI) tracking. Centers of Disease Control and Prevention website. https://www.cdc.gov/hai/eip/cdiff-tracking.html. Published February 24, 2022. Accessed October 30, 2023.

- 5. Guh AY, Mu Y, Winston LG, et al. Trends in US burden of Clostridioides difficile infection and outcomes. N Engl J Med 2020;382:1320–1330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Czepiel J, Dróżdż M, Pituch H, et al. Clostridium difficile infection: review. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 2019;38:1211–1221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Eze P, Balsells E, Kyaw MH, Nair H. Risk factors for Clostridium difficile infections—an overview of the evidence base and challenges in data synthesis. J Global Health 2017;7:010417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Davies K, Lawrence J, Berry C, et al. Risk factors for primary Clostridium difficile infection: results from the Observational Study of Risk Factors for Clostridium difficile Infection in Hospitalized Patients With Infective Diarrhea (ORCHID). Front Public Health 2020;8:293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Argamany JR, Delgado A, Reveles KR. Clostridium difficile infection health disparities by race among hospitalized adults in the United States, 2001 to 2010. BMC Infect Dis 2016;16:454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.CDC locations and descriptions and instructions for mapping patient care locations table of contents instructions for mapping patient care locations. Step 1: Define the acuity level for the location. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. https://www.cdc.gov/nhsn/pdfs/pscmanual/15locationsdescriptions_current.pdf. Published 2021. Accessed October 30, 2023.

- 11. Karlovich NS, Sata SS, Griffith B, et al. In pursuit of the holy grail: improving C. difficile testing appropriateness with iterative electronic health record clinical decision support and targeted test restriction. Infect Control Hospital Epidemiol 2022;43:840–847. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.National Healthcare Safety Network. Multidrug-resistant organism & Clostridioides difficile infection (MDRO/CDI) module. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. https://www.cdc.gov/nhsn/psc/cdiff/index.html. Published 2022. Accessed October 30, 2023.