Abstract

Recent clinical trials examining 3′-azido-3′-deoxythymidine (AZT, zidovudine, or Retrovir) combined with l-2′,3′-dideoxy-3′-thiacytidine (3TC or lamivudine) have shown that combination therapy with these nucleoside analogs affords significant virological and clinical benefits. The addition of 3TC to AZT delays AZT resistance in therapy-naive patients and can restore viral AZT susceptibility in patients who previously received AZT alone. In some AZT-experienced patients, the virological response to AZT-3TC therapy is not sustained and virus resistant to both drugs can be identified. To gain insight into the possible mechanism of dual resistance, we studied a recently described variant resistant to both AZT and 3TC and obtained by simultaneous passage of an AZT-resistant clinical isolate in cell culture with AZT and 3TC. Genetic mapping and site-directed mutagenesis experiments demonstrated that a polymorphism at codon 333 (Gly to Glu) of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 reverse transcriptase (RT) was critical in facilitating dual resistance in a complex background of AZT and 3TC resistance mutations. To assess the potential clinical relevance of RT codon 333 changes, we studied dually resistant viruses from patients taking AZT and 3TC. Genetic mapping of RT molecular clones derived from patients’ plasma samples demonstrated that in some cases polymorphism at codon 333 was responsible for facilitating dual resistance.

Zidovudine (3′-azido-3′-doexythymidine, AZT, or Retrovir) is commonly used in combination with other antiretroviral agents for the treatment of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) infection. AZT therapy delays the development of AIDS and increases the survival of patients with AIDS (6, 12, 39). Long-term treatment with AZT monotherapy results in the eventual development of resistance to AZT (22, 26, 33), which ultimately leads to treatment failure (4, 32). Site-directed mutagenesis experiments have demonstrated that at least five amino acid changes in reverse transcriptase (RT) of HIV-1 (at codons 41, 67, 70, 215, and 219) are responsible for AZT resistance (16, 20; for reviews, see references 19 and 31). The first mutation to arise after several months of AZT monotherapy is typically at codon 70, which results in an approximate eightfold increase in the 50% inhibitory concentration (IC50). More resistant viruses, usually having combinations of mutations that include changes at codons 41 and 215, subsequently become dominant in the resistant virus population (3, 17). Highly AZT-resistant variants (with IC50s increased more than 100-fold) require the accumulation of four to six mutations in RT, frequently including a recently recognized mutation at codon 210 of RT (10, 11).

In contrast to AZT resistance, high-level resistance to the nucleoside analog l-2′,3′-dideoxy-3′-thiacytidine (3TC or lamivudine) is conferred by a single mutation in HIV-1 RT at codon 184 (Met-184 to Val or occasionally Ile) (2, 7, 34, 38). The appearance of this mutation during 3TC therapy is associated with an increase in plasma HIV-1 levels and treatment failure (35). Of note is that the 184 Val mutation causes a concomitant increase in AZT sensitivity in genotypically AZT-resistant backgrounds (2, 24, 38). Furthermore, AZT-3TC combination therapy in drug-naive patients leads to a delay in the appearance of AZT resistance mutations even though 3TC resistance occurs rapidly (18, 24). These observations have prompted speculation that dual resistance to both drugs may not develop easily, as phenotypic AZT resistance in the presence of the 184 Val mutation may be rare.

The results of several clinical trials examining the safety and efficacy of AZT-3TC combination therapy have recently been published (1, 5, 14, 37). Collectively, these studies showed substantial effects on virological markers and significant clinical benefit in either therapy-naive or AZT-experienced patients. One plausible explanation for the duration of this benefit in therapy-naive patients is the observed delay in the development of AZT resistance, as discussed above. In AZT-experienced patients, more complex patterns of virological response and resistance have been observed, ranging from restoration of AZT susceptibility to the development of AZT-3TC dual resistance (13, 27, 28).

An HIV-1 variant that was selected in cell culture and that became simultaneously highly resistant to AZT and 3TC was recently described (8). This mutant was obtained by cell culture passage in both AZT and 3TC of a preexisting highly AZT-resistant clinical isolate (1373). To increase our understanding of how HIV-1 can become resistant to both AZT and 3TC, we describe a mapping and site-directed mutagenesis study designed to define the genetic basis of dual resistance of this cell culture-selected variant. A novel polymorphism at RT codon 333 was shown to be responsible for facilitating dual resistance in the context of AZT and 3TC resistance mutations. To determine the relevance of this codon 333 polymorphism in AZT- and 3TC-treated patients, we studied HIV-1 clinical isolates by genetic mapping of RT molecular clones. In some cases, polymorphism at codon 333 was responsible for facilitating dual resistance.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cloning and sequencing of the HIV-1 RT gene from virus resistant to AZT and 3TC.

The RT coding region (1.7 kb) of the AZT- and 3TC-resistant virus was amplified by PCR from infected-cell DNA and cloned into the M13 vector mptac18.1 as described previously (20). Single-stranded DNAs from this clone (mpAZTr3TCr) and the 3TC-susceptible, AZT-resistant parental clone (mpAZTr1373) were sequenced with a PRISM Sequenase terminator single-stranded DNA sequencing kit (Applied Biosystems) and resolved on an ABI 373 DNA sequencer (25). Recombinant clones containing a 1.7-kb fragment were assessed for the ability to express active RT by induction of M13-infected Escherichia coli (strain 5KCPolAtsF′) with isopropyl-d-thiogalactopyranoside and measurement of RT activity in E. coli lysates as described previously (20).

Construction of HIV-1 variants with recombinant RT genes.

The EcoRI-EcoRV fragment encoding the equivalent of RT codons 1 to 143 was purified from mpAZTr3TCr and mpRTMQ+184V, a mutant construct that was described previously and that carries 41Leu, 67Asn, 70Arg, 184Met, and 215Tyr in the HIV-1HXB2-D background (24). The fragments were then ligated with EcoRI-EcoRV-digested mpRTMQ+184V and mpAZTr3TCr, respectively, to form recombinant clones. The KpnI fragment encoding the equivalent of RT codons 428 to 535 (i.e., most of the RNase H domain) was purified from M13 clone HIV-1XHB2 and ligated with KpnI-digested mpAZTr3TCr. The entire RT coding region from each of these recombinant clones was linearized by digestion with EcoRI and HindIII and subsequently transferred into the otherwise wild-type HIV-1HXB2-D background by homologous recombination. The T-cell line MT-2 (9) was cotransfected by electroporation with a mixture of the RT-deleted proviral clone pHIVRTBstEII and the EcoRI- and HindIII-digested DNA described above (15). A PCR fragment (codons 7 to 243) derived from mpAZTr3TCr with the oligonucleotide primer pair comb2 and comb3 (24) was also used in recombination experiments with the pHIVBst11071 clone, which contains a 578-bp deletion in RT from codons 40 to 231 (24).

Site-directed mutagenesis of RT and construction of HIV-1 recombinants.

Mutations in the RT gene were created by site-directed mutagenesis of the M13 clones mpAZTr3TCr and mpRTMQ+184V as described previously (23). Variants were constructed to convert mutant RT codon 333 (Glu) to wild-type Gly in mpAZTr3TCr and to convert wild-type RT codon 333 (Gly) in mpRTMQ+184V to mutant Glu. Mutations were verified by DNA sequence analysis as described above. M13 replicative-form DNA was prepared, and the altered RT coding regions were transferred into the HIV-1HXB2-D genetic background by homologous recombination with pHIVRTBstEII as described above.

Construction of infectious clones containing RT derived from plasma HIV-1 RNA.

To produce HIV-1 infectious clones from plasma viral RNA, we used a recently described system based on the novel cloning vector xxLAI-np (36). HIV-1 RNA was extracted from 1.0 ml of patient plasma with RNAzol B (Biotecx Laboratories, Inc., Houston, Tex.). RNA from the equivalent of 100 to 500 μl of plasma and 10 pmol of downstream PCR primer were used for cDNA synthesis with SuperScriptII RNaseH− RT (Gibco-BRL, Long Island, N.Y.). A nested PCR strategy was used to amplify the 1,460-bp RT fragment (codons 15 to 440) from the cDNA as described previously (36). The PCR products were column purified (Promega Corporation, Madison, Wis.), digested with XmaI and XbaI, and repurified by ethanol precipitation (this product is referred to as xxRT). The vector backbone was prepared by digesting xxLAI-np with XmaI and XbaI. Approximately 0.02 μg of xxRT was ligated with 0.02 μg of gel-purified xxLAI-np backbone by use of T4 DNA ligase (Promega), and the entire ligation mixture was used to transform competent E. coli JM109. The proviral libraries were expanded by overnight growth in Luria-Bertani broth containing ampicillin. Individual proviral clones were isolated by spreading the transformed cells onto Luria-Bertani agar plates containing ampicillin. Proviral DNA was purified (Qiagen Inc., Chatsworth, Calif.) and screened for the 1,460-bp xxRT insert by digestion with XmaI and XbaI. Recombinant viruses were produced by electroporating 5 μg of recombinant DNA into MT-2 cells as described above. Supernatants containing virus were harvested at the peak of cytopathic effect, which occurred 5 to 7 days after transfection.

Fragment exchange and site-directed mutagenesis in the xxLAI-np vector.

The 1,460-bp XmaI-XbaI fragment was cut from single coresistant proviral clones, separated by agarose gel electrophoresis, and purified with a GeneClean II kit (Bio 101, Inc., La Jolla, Calif.). The fragment was then digested with BstYI, PflmI, and Bsp1286I to generate XmaI-BstYI, XmaI-PflmI, and XmaI-Bsp1286I fragments corresponding to codons 14 to 190, 14 to 315, and 14 to 359 of RT, respectively. Similarly, BstYI-XbaI, Pflm1-XbaI, and Bsp1286I-XbaI fragments were isolated from wild-type xxLAI. The fragments were gel purified and ligated with the xxLAI-np backbone to generate proviruses with RT amino acid residues 14 to 190, 14 to 315, and 14 to 359 derived from coresistant clones. Site-directed mutagenesis of the XmaI-XbaI RT fragment was carried out with an Altered Sites in vitro mutagenesis system (Promega). XmaI-XbaI fragments from individual viral clones were ligated into the pALTER-1 mutagenesis vector, and single-stranded DNA was prepared and used as a template in mutagenesis reactions. Mutant colonies were screened by direct sequencing of the plasmid DNA. XmaI-XbaI fragments containing the desired mutations were then cloned into xxLAI-np for the production of infectious virus by electroporation of MT-2 cells as described above.

AZT and 3TC susceptibility assays.

The AZT and 3TC susceptibilities of HIV-1 variants with recombinant RT genes and site-directed mutant viruses were determined by a plaque reduction assay with the HeLa-CD4+ cell line HT4LacZ-1 by infection of cell monolayers as described previously (21, 36). The resulting syncytia were counted following staining with either methyl violet (21) or 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactopyranoside (36). The IC50s were determined by linear regression analysis of the log10 inhibitor concentration versus percent inhibition of syncytium formation.

RESULTS

Analysis of an AZT- and 3TC-resistant laboratory strain.

We first confirmed by a plaque reduction assay with HeLa-CD4+ cells the previously reported drug susceptibility of the 1373 virus before and after passage in AZT and 3TC (8). As anticipated, the initial isolate was AZT resistant and 3TC sensitive (respective IC50s, 1.98 and 3.89 μM). In contrast, the passaged virus remained AZT resistant but was also 3TC resistant (respective IC50s, 0.86 and >200 μM). We next sequenced the entire RT coding regions from the AZT- and 3TC-resistant variant AZTr3TCr as well as the parental virus. Both viruses had the following AZT resistance mutations: Met41Leu, Asp67Asn, Lys70Arg, Leu210Trp, and Thr215Tyr. In addition, we found six differences between these viruses in the deduced amino acid sequence of RT (i.e., Arg20Lys, Thr39Lys, Met184Val, Asp192Glu, His480Gln, and Lys558Arg). The only recognizable drug resistance mutation induced during the passage experiment was the 3TC resistance mutation Met184Val.

Mapping AZT and 3TC dual resistance mutations by marker transfer.

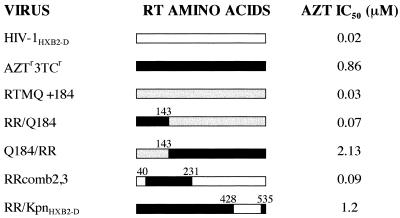

In order to map the mutation(s) responsible for the AZT and 3TC dual resistance phenotype of the AZTr3TCr virus, experiments were performed in which RT DNA fragments were transferred between the dually resistant virus and the laboratory-derived mutant RTMQ+184V (carrying Met184Val and the AZT resistance mutations Met41Leu, Asp67Asn, Lys70Arg, and Thr215Tyr in the HIV-1HXB2-D background). The source of DNA for these marker transfer experiments was M13 clones containing mutant RT coding regions. As shown schematically in Fig. 1, the EcoRI-EcoRV fragment encompassing codons 1 to 143 of the RT polymerase domain was exchanged between the M13 clone mpAZTr3TCr described above and mpRTMQ+184V. The KpnI fragment carrying codons 428 to 535 of RT (virtually all of the RNase H domain) was exchanged between the M13 clone HXB2 mpAZTr3TCr. Infectious viruses with recombinant RT genes were recovered by recombination with the RT deletion proviral clone pHIVRTBstEII. A PCR fragment derived from mpAZTr3TCr with the oligonucleotide primer pair comb2 and comb3 was also used in the recombination experiments, but in this case, with the partial RT deletion clone pHIVBst11071 (24). This procedure resulted in the transfer of a mutant RT fragment containing RT codons 40 to 231.

FIG. 1.

Mapping AZT and 3TC dual resistance in HIV-1 strain AZTr3TCr. In order to map dual resistance in laboratory isolate AZTr3TCr, various RT fragments were exchanged between either mpAZTr3TCr and the wild-type virus (HIV-1HXB2-D) or AZTr3TCr and RTMQ+184Val (RTMQ+184). RTMQ+184Val contains the following RT mutations in the HIV-1HXB2-D background: Met41Leu, Asp67Asn, Lys70Arg, Met184Val, and Thr215Tyr. The open bars represent HIV-1HXB2-D RT, the solid bars represent AZTr3TCr RT, and the hatched bars represent RTMQ+184Val RT. The numbers above the bars are the amino acid positions at which RT fragments were exchanged. In recombinant RRcomb2,3, residues 40 to 231 represent the size of the deletion in the deletion clone used to construct the virus; since this virus was constructed by recombination, the maximum possible size of the mutant fragment in the virus is the size of the deletion. Recombinant viruses were assessed for AZT susceptibility with the HeLa-CD4+ cell assay as described in Materials and Methods.

The sensitivity of these viruses to AZT and 3TC was assessed by a plaque reduction assay with the HeLa-CD4+ cell line HT4LacZ-1 (Fig. 1). The virus RR/Q184, constructed with the RT fragment 5′ of the EcoRV site from the dually resistant virus and the RT fragment 3′ of the EcoRV site from RTMQ+184V, was sensitive to AZT (IC50, 0.07 μM) and resistant to 3TC (IC50, >200 μM). Although this virus contained four of the known AZT resistance mutations (at codons 41, 67, 70, and 215), the codon 184 mutation suppressed AZT resistance in this background (24). The recombinant Q184/RR, constructed conversely to that above, was resistant to both drugs (AZT IC50, 2.13 μM; 3TC IC50, >200 μM). This fact indicated that the mutation(s) responsible for dual resistance mapped to the RT fragment 3′ of the EcoRV site (codons 143 to 560). To address the role of the mutations between codons 143 and 231, a recombinant virus was constructed by cotransfecting the comb2-comb3 PCR fragment (spanning RT codons 7 to 243) with the RT deletion clone pHIVBst11071 (with a deletion of codons 40 to 231). The resulting virus, RRcomb2,3, was AZT sensitive (IC50, 0.09 μM) and 3TC resistant (IC50, >200 μM). Finally, we assessed the drug sensitivity of recombinant RR/KpnHXB2-D, which contained virtually the whole RNase H domain from the wild-type virus (codons 428 to 535) in the background of the dually resistant strain. This virus retained AZT resistance (Fig. 1) and was also resistant to 3TC (IC50, >200 μM). From these results, it was clear that the mutation(s) responsible for dual resistance mapped to the 3′ end of RT between codons 231 and 428 or between codons 536 and 560.

Construction of HIV-1 strains with codon 333 polymorphisms.

Closer inspection of the 3′ end of RT (from codons 231 to 428 and 536 to 560) revealed nine amino acid changes between HIV-1HXB2-D and AZTr3TCr (i.e., Gly333Glu, Gly359Ser, Ala371Val, Ile375Val, Thr376Ala, Lys390Arg, Glu404Asp, Phe416Tyr, and Lys558Arg). All of these changes were seen in the parental 1373 virus, except for codon 558, which was Lys, as in HIV-1HXB2-D. Of these residues that could have been responsible for the dual resistance phenotype, codon 333 was highly conserved among wild-type HIV-1 variants, whereas the other residues were less conserved. It should be noted, however, that the Gly333Glu polymorphism was not selected during in vitro passage but was already present in the parental virus (AZT-resistant isolate 1373). Nevertheless, because amino acid conservation implies an important role in the function of the enzyme, we decided to construct variants by site-directed mutagenesis to assess the potential role of the Gly333Glu polymorphism in AZT and 3TC coresistance.

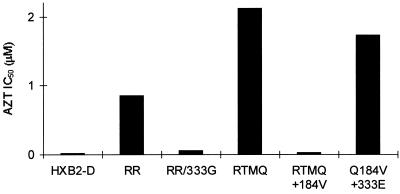

First, we converted codon 333Glu in the dually resistant variant to the wild-type residue, Gly. The resulting variant was 3TC resistant but showed a marked increase in sensitivity to AZT (3TC IC50, 200 μM; AZT IC50, 0.06 μM) (Fig. 2). Next, we introduced the Gly333Glu polymorphism into the AZT-sensitive, 3TC-resistant (IC50, >200 μM) laboratory variant RTMQ+184V. This process rendered the resulting virus resistant to both AZT (IC50, 1.73 μM) and 3TC (IC50, >200 μM) (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

AZT susceptibility of recombinant HIV-1 variants with altered RT codon 333. Recombinant viruses were constructed by site-directed mutagenesis in order to alter RT codon 333. This codon was changed from Glu to Gly in the dually resistant strain AZTr3TCr (designated RR) to produce RR/333G. In addition, codon 333 was changed from Gly to Glu in the laboratory isolate RTMQ+184Val (designated RTMQ+184V) to produce Q184V+333E. RTMQ is an AZT-resistant strain based on HIV-1HXB2-D and containing the following changes in RT; Met41Leu, Asp67Asn, Lys70Arg, and Thr215Tyr. Recombinant viruses were assessed for AZT susceptibility with the HeLa-CD4+ cell assay as described in Materials and Methods.

Genetic analysis of dually resistant HIV-1 from AZT- and 3TC-treated patients.

Recombinant viruses containing RT sequences derived from plasma HIV-1 RNA were constructed with samples from five patients receiving AZT and 3TC and in whom treatment failure was suspected from declining CD4+ T-cell counts (50% decrease from baseline) and/or a new onset of HIV-1-related symptoms (27). Baseline (pretherapy) samples were not available for analysis. HIV-1 RT fragments (1,460 bp) were derived by RT-PCR of plasma viral RNA and were subsequently ligated into the RT cassette cloning vector xxLAI-np in order to obtain infectious HIV-1 molecular clones. Clonal mixtures and individual subclones were used to generate infectious virus for AZT and 3TC susceptibility determinations. Recombinant viruses derived from the clonal mixtures (not shown) as well as the individual subclones (Table 1) showed dual resistance to AZT and 3TC for all five patients. Recombinant viruses derived from four control patients who had stable CD4+ T-cell counts and no HIV-1-related symptoms on AZT and 3TC therapy showed resistance to 3TC (IC50, >30 μM) but not AZT (IC50, <0.01 μM) (data not shown).

TABLE 1.

AZT and 3TC susceptibilities of recombinant virus clones derived from plasma HIV-1 RNA from five patients

| Virus | IC50, μM, of (fold resistance):

|

|

|---|---|---|

| AZT | 3TC | |

| xxLAI-np (control) | 0.006 | 0.3 |

| G2-1b | 0.32 (54) | >30 (>100) |

| G2-3g | 1.0 (160) | >30 (>100) |

| V178a | 0.8 (134) | >30 (>100) |

| G2-2a | 0.2 (33) | >30 (>100) |

| V213b | 3.7 (617) | >30 (>100) |

We next performed a series of fragment exchange experiments with dually resistant proviral clones in which mutant sequences were exchanged for wild-type sequences to derive a series of chimeric recombinant strains (containing fragments from dually resistant clones corresponding to RT amino acids 14 to 190, 14 to 315, and 14 to 359). Dual resistance mapped to RT regions encoding amino acids 190 to 315 in three of these clones and to amino acids 315 to 359 in the remaining two clones (Table 2). The genotypes of these clones, shown in Table 3, revealed the presence of the codon 333 polymorphism in the two clones (G2-2a and V213b) in which dual resistance mapped to regions encoding amino acids 315 to 359. Sequencing of the original clonal mixtures from which the subclones were derived also demonstrated the polymorphism at codon 333, indicating that it was the predominant species in the plasma samples (data not shown).

TABLE 2.

Mapping AZT and 3TC dual resistance in clones from clinical isolates

| Sample | Fold AZT resistance (relative to that of LAI) of mutant virus comprising RT amino acids:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| 14 to 190 | 14 to 315 | 14 to 359 | |

| G2-1b | 2.0 | 172 | Not done |

| G2-3g | 1.0 | 40 | Not done |

| V178a | 2.0 | 220 | 150 |

| G2-2a | 1.4 | 1.1 | 35 |

| V213b | Not done | 2.0 | 114 |

TABLE 3.

Genotypes of five AZT- and 3TC-resistant clones from patient samples

| LAI | Mutation in amino acidsa

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 190 to 315

|

315 to 359

|

||||

| G2-1b | G2-3g | V178a | G2-2a | V213b | |

| M41 | L | L | L | L | — |

| D67 | — | N | N | — | N |

| K70 | — | — | R | — | — |

| M184 | V | V | V | V | V |

| L210 | W | W | W | W | W |

| T215 | Y | Y | — | Y | Y |

| K219 | E | — | E | — | — |

| G196 | — | — | — | — | E |

| T200 | I | — | I | — | — |

| E203 | — | — | K | D | — |

| Q207 | E | — | — | A | D |

| H208 | — | Y | — | — | — |

| R211 | K | K | K | K | K |

| L214 | F | F | F | F | F |

| L228 | — | — | H | — | — |

| V245 | — | — | E | M | — |

| P272 | — | — | A | — | — |

| R277 | K | — | K | N | — |

| L283 | — | — | I | I | — |

| R284 | K | — | — | K | — |

| T286 | — | — | P | — | — |

| I293 | — | V | — | — | — |

| E297 | — | A | — | — | — |

| E300 | — | — | — | D | Q |

| K311 | — | — | R | R | — |

| I326 | V | — | — | — | — |

| I329 | V | — | — | V | — |

| G333 | — | — | — | D | E |

| Q334 | — | — | — | N | — |

| T338 | — | — | — | — | S |

| F346 | — | — | — | Y | — |

| K347 | — | — | — | R | |

| R356 | K | K | — | — | K |

| T357 | — | M | M | M | M |

| G359 | — | S | S | S | — |

| A360 | T | — | — | — | — |

| A371 | — | V | — | V | — |

| T376 | — | A | — | — | — |

| K388 | — | R | — | — | — |

Boldfacing indicates the amino acid substitutions in the fragment conferring dual resistance. —, wild-type sequence (relative to LAI).

The relevance of the Gly333Glu-Asp polymorphisms for the dual resistance of these clones was determined by reversion of the Glu or Asp residues by site-directed mutagenesis to the wild-type residue, Gly. Drug susceptibility analysis showed that the AZT susceptibility of the revertants had increased by six- to sevenfold (Table 4). Conversely, conversion of the natural Gly333 residue to Asp in the LAI background containing only 41Leu, 184Val, 210Trp, and 215Tyr resulted in a 7.7-fold decrease in AZT susceptibility (Table 4).

TABLE 4.

AZT susceptibility of HIV-1 clones from clinical samples with a reversion at RT codon 333

| Viral recombinant | AZT IC50, μM (fold resistance) |

|---|---|

| xxLAI | 0.006 |

| G2-2a | 0.2 (33) |

| G2-2a/D333G (revertant) | 0.03 (5) |

| V213b | 3.7 (617) |

| V213b/E333G (revertant) | 0.54 (90) |

| xxLAI-np/41L/184V/210W/215Y | 0.007 (1.2) |

| xxLAI-np/41L/184V/210W/215Y/333D | 0.046 (7.7) |

DISCUSSION

The initial aim of this study was to elucidate the genetic basis of AZT and 3TC dual resistance in a laboratory-derived HIV-1 isolate. This topic was of interest for a number of reasons. First, early attempts to select such variants by cell culture passage experiments were unsuccessful, presumably because of the effect of the 184Val mutation on AZT resistance (24). Second, it has recently become evident that in addition to the occurrence of restored phenotypic AZT susceptibility, AZT- and 3TC-resistant variants may emerge during combination AZT-3TC therapy (13, 27, 28). This finding appears more common in the context of extensively AZT-experienced patients receiving AZT-3TC combination therapy and who already have AZT-resistant virus. Thus, we anticipated that a clearer understanding of the genetic nature of dual resistance in a laboratory variant would provide a broader understanding of this mechanism, particularly in clinical strains.

It was quite unexpected that our mapping and site-directed mutagenesis studies would reveal a polymorphism at codon 333 in RT as the change responsible for facilitating dual resistance. This finding was particularly intriguing because the Gly333Glu change was not selected during passage of the virus in AZT and 3TC but already existed in the initial AZT-resistant strain. This variant was already highly AZT resistant and contained five of the six recognized AZT resistance mutations (at codons 41, 67, 70, 210, and 215). Selection of the 184Val mutation by passage in AZT and 3TC subsequently conferred high-level 3TC resistance. However, in the context of the preexisting 333Glu polymorphism, it appeared that 184Val no longer exerted the expected AZT resistance reversal effect. This result was proven in two ways. First, conversion of 333Glu to Gly in the dually resistant variant caused a concomitant switch to an AZT-susceptible phenotype. Second, mutation of the wild-type Gly333 residue to Glu in the AZT-susceptible laboratory isolate RTMQ+184V resulted in an AZT resistance phenotype despite the presence of 184Val. It should be noted that the 333Glu change alone is not responsible for conferring dual resistance but somehow influences AZT susceptibility in the context of AZT and 3TC resistance mutations.

The precise molecular mechanism by which 333Glu modulates AZT resistance in the presence of 184Val and AZT resistance mutations is not obvious. The crystal structure of HIV-1 RT shows that residue Gly333 in the p66 subunit is located far from the polymerase active site (approximately 42 Å from the carbon of residue 333 to that of residue 184), in the so-called connection domain of the enzyme (29, 36a). This domain lies between the palm region in the polymerase domain and the RT carboxy terminus, which comprises the RNase H domain (29). Gly333 in the RT p66 subunit is also positioned close to the base of the thumb region, which is involved in template-primer interactions. Thus, it is possible that changes at this position alter the positioning of the thumb region and subsequently reposition the template-primer in the active site of the polymerase domain. Recently, the crystal structure of HIV-1 RT containing four AZT resistance mutations was solved. The structure showed that AZT resistance mutations at codons 215 and 219 give rise to a conformational change in the RT polypeptide that extends to the active-site Asp residues (30). Clearly, long-range effects of these mutations can modulate the recognition of AZT triphosphate in the polymerase active site. Similarly, crystal structures of mutant RT enzymes harboring the 333Glu change together with AZT and 3TC resistance mutations may reveal specific movements in the enzyme active site and shed light on this molecular mechanism of dual resistance.

We conducted an investigation of the genetic basis of dual resistance in recombinant viruses containing RT sequences from five patients with clinical evidence of AZT and 3TC treatment failure. We used a novel RT cassette cloning system which enables the generation of infectious HIV-1 clones that can be used to produce virus for a susceptibility analysis. We found that viruses from two of these individuals were dually resistant due to amino acid polymorphisms in the RT region from residues 315 to 359. Sequence analysis revealed the previously recognized change at codon 333 of Gly to Glu, in addition to a novel change of Gly to Asp. Reversion of Glu or Asp to Gly unequivocally demonstrated that these polymorphisms were responsible for facilitating dual resistance in the context of the AZT and 3TC resistance mutations. Thus, it appears that this mechanism of dual resistance can occur in patients in a manner similar to that in the laboratory variant that we analyzed. Final confirmation that the 333Asp residue influences dual resistance came from the conversion of Gly to Asp in a clonal laboratory LAI strain that contained 184Val plus AZT resistance mutations. Therefore, it appears that the Asp substitution at codon 333 causes a phenotypic effect similar to that of the Glu substitution. We assume that, as in the situation with the 1373 virus, the observed polymorphisms at codon 333 in isolates G2-2a and V213b were preexisting. Since we did not have pretherapy samples, we cannot rule out the possibility that these changes at codon 333 appeared during therapy. However, sequence analysis of baseline samples from about 100 AZT-experienced individuals who participated in the AZT-3TC combination therapy trial NUCB3002 showed that the codon 333 polymorphisms preexisted in the viral population at a frequency of 10% (unpublished observations).

A recent report suggested that AZT and 3TC dual resistance in clinical isolates from four individuals was a function of the overall number of amino acid changes in RT (28). In that study, changes in the C-terminal region of RT (between residues 261 and 561) were not found to play a major role in dual resistance. However, only one of these isolates had a high level of AZT resistance similar to that of the laboratory and clinical isolates examined in our study. Only this isolate is analogous to the clonal samples G2-1b, G2-3g, and V178a analyzed here. The other three isolates reported by Nijhuis et al. (28) displayed various degrees of partial resistance to AZT. Although sequence data were not shown, we anticipate that in these isolates the 333Glu-Asp polymorphism was not present. Thus, the fact that these isolates were not highly AZT resistant is consistent with the 184Val mutation still having a suppressive effect.

Our findings regarding the influence of residue 333 on AZT resistance obviously have implications for the interpretation of HIV-1 RT genotypic profiles from clinical samples. By focusing only on the six recognized AZT resistance mutations plus codon 184, it is clearly not possible to derive an accurate picture of the viral phenotype. Under certain circumstances, a virus may be phenotypically AZT susceptible because of the influence of 184Val, even though significant numbers of AZT resistance mutations are present. Conversely, a virus may be phenotypically AZT resistant when all of these mutations are present along with polymorphism at codon 333. Therefore, sequence information from the 3′ region of RT in addition to the 5′ region is required to make more reliable predictions about the likely phenotype. However, the situation regarding AZT and 3TC dual resistance is obviously quite complex. Additional polymorphisms in the 3′ region of RT may also turn out to influence dual resistance, as may polymorphisms in the 5′ region (implied by the study of Nijhuis et al. [28] and also by three of the clonal clinical isolates in the present study). We are now focusing on understanding the genetic basis of AZT and 3TC dual resistance in a larger collection of clinical isolates. It is anticipated that this work will further help to define polymorphisms in RT that facilitate dual resistance. Such information is of clear importance in situations in which only the viral genotype is determined as a means of assessing drug resistance of virus from treated individuals.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank M. Goulden for supplying the HIV-1 1373 viral isolates. We thank V. Miller and S. Staszewski for patient plasma samples G2-1b, G2-3g, V178a, G2-2a, and V213b.

This work was supported in part by research grants from the Medical Research Service of the Department of Veterans Affairs, from the Department of Defence, and from the National Institutes of Health (RO1A134301-01).

REFERENCES

- 1.Bartlett J A, Benoit S L, Johnson V A, Quinn J B, Sepulveda G E, Ehmann W C, Soukas C T, Fallon M A, Self P L, Rubin M. Lamivudine plus zidovudine compared with zalcitabine plus zidovudine in patients with HIV infection. Ann Intern Med. 1996;125:161–172. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-125-3-199608010-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boucher C A, Cammack N, Schipper P, Schuurman R, Rouse P, Wainberg M A, Cameron J M. High-level resistance to (−) enantiomeric 2′-deoxy-3′-thiacytidine in vitro is due to one amino acid substitution in the catalytic site of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 reverse transcriptase. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1993;37:2231–2234. doi: 10.1128/aac.37.10.2231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boucher C A, O’Sullivan E, Mulder J W, Ramautarsing C, Kellam P, Darby G, Lange J M, Goudsmit J, Larder B A. Ordered appearance of zidovudine resistance mutations during treatment of 18 human immunodeficiency virus-positive subjects. J Infect Dis. 1992;165:105–110. doi: 10.1093/infdis/165.1.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.D’Aquila R T, Johnson V A, Welles S L, Japour A J, Kuritzkes D R, DeGruttola V, Reichelderfer P S, Coombs R W, Crumpacker C S, Kahn J O, Richman D D. Zidovudine resistance and HIV-1 disease progression during antiretroviral therapy. AIDS Clinical Trials Group Protocol 116B/117 Team and the Virology Committee Resistance Working Group. Ann Intern Med. 1995;122:401–408. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-122-6-199503150-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eron J J, Benoit S L, Jemsek J, MacArthur R D, Santana J, Quinn J B, Kuritzkes D R, Fallon M A, Rubin M the North American HIV Working Party. Treatment with lamivudine, zidovudine, or both in HIV-positive patients with 200 to 500 CD4+ cells per cubic millimeter. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:1662–1669. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199512213332502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fischl M, Richman D D, Grieco M, Gottlieb M S, Volberding P A, Laskin O L, Leedom J M, Groopman J E, Mildvan D, Schooley R T, Jackson G G, Durack D T, King D the AZT Collaborative Working Group. The efficacy of azidothymidine (AZT) in the treatment of patients with AIDS and AIDS related complex: a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. N Engl J Med. 1987;317:185–191. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198707233170401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gao Q, Gu Z, Parniak M A, Cameron L, Cammack N, Boucher C, Wainberg M A. The same mutation that encodes low-level human immunodeficiency virus resistance to 2′,3′-dideoxyinosine and 2′,3′-dideoxycytidine confers high-level resistance to the (−) enantiomer of 2′,3′-dideoxy-3′-thiacytidine. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1993;37:1390–1392. doi: 10.1128/aac.37.6.1390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goulden M G, Cammack N, Hopewell P L, Penn C R, Cameron J M. Selection in vitro of an HIV-1 variant resistant to both lamivudine (3TC) and zidovudine. AIDS. 1996;10:101–102. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199601000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harada S, Koyanagi Y, Yamamoto N. Infection of HTLV-III/LAV in HTLV-I carrying cells MT-2 and MT-4 and application in a plaque assay. Science. 1985;229:563–566. doi: 10.1126/science.2992081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Harrigan P R, Kinghorn I, Bloor S, Kemp S D, Najera I, Kohli A, Larder B A. Significance of amino acid variation at human immunodeficiency virus type 1 reverse transcriptase residue 210 for zidovudine susceptibility. J Virol. 1996;70:593–594. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.9.5930-5934.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hooker D, Tachedjian G, Soloman A E, Gurusinghe A D, Land S, Birch C, Anderson J L, Roy B M, Arnold E, Deacon N J. An in vivo mutation from leucine to tryptophan at position 210 in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 reverse transcriptase contributes to high-level resistance to 3′-azido-3′-deoxythymidine. J Virol. 1996;70:8010–8018. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.11.8010-8018.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ioannidis J P, Cappelleri J C, Lau J, Skolnik P R, Melville B, Chalmers T C, Sacks H S. Early or deferred zidovudine therapy in HIV-infected patients without an AIDS-defining illness. Ann Intern Med. 1995;122:856–866. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-122-11-199506010-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Johnson, V. A., C. B. Overbay, J. L. Koel, C. D. Nail, J. A. Bartlett, N. Cammack, J. B. Quinn, J. Johnson, A. L. Keller, M. Rubin, and J. D. Hazelwood. 1996. Drug resistance, viral load and SI phenotype in NUCA3002: combined 3TC/ZDV therapy over a maximum of 52 weeks in ZDV-experienced (>24 weeks) patients (CD4+ 100-300 cells/mm3). Antiviral Ther. 1(Suppl. 1):36–37.

- 14.Katlama C, Ingrand D, Loveday C, Hill A M, Pearce G, McDade H the Lamivudine European HIV Working Group. Safety and efficacy of lamivudine-zidovudine combination in antiretroviral-naive patients. JAMA. 1996;276:118–125. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kellam P, Larder B A. Recombinant virus assay: a rapid, phenotypic assay for assessment of drug susceptibility of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 isolates. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1994;38:23–30. doi: 10.1128/aac.38.1.23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kellam P, Boucher C A B, Larder B A. Fifth mutation in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 reverse transcriptase contributes to the development of high level resistance to zidovudine. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:1934–1938. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.5.1934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kellam P, Boucher C A B, Tijnagel J M G H, Larder B A. Zidovudine treatment results in the selection of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 variants whose genotypes confer increasing levels of drug resistance. J Gen Virol. 1994;75:341–351. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-75-2-341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kuritzkes D R, Quinn J B, Benoit S L, Shugarts D L, Griffin A, Bakhtiari M, Poticha D, Eron J J, Fallon M A, Rubin M. Drug resistance and virologic response in NUCA3001, a randomized trial of lamivudine (3TC) versus zidovudine (AZT) versus AZT plus 3TC in previously untreated patients. AIDS. 1996;10:975–981. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199610090-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Larder B A. Interactions between drug resistance mutations in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 reverse transcriptase. J Gen Virol. 1995;75:951–957. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-75-5-951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Larder B A, Kemp S D. Multiple mutations in HIV-1 reverse transcriptase confer high level resistance to zidovudine. Science. 1989;246:1155–1158. doi: 10.1126/science.2479983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Larder B A, Cheesbro B, Richman D D. Susceptibility of zidovudine-sensitive and -resistant human immunodeficiency virus isolates to antiviral agents determined using a quantitative plaque reduction assay. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1990;34:436–441. doi: 10.1128/aac.34.3.436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Larder B A, Darby G, Richman D D. HIV with reduced sensitivity to zidovudine (AZT) isolated during prolonged therapy. Science. 1989;243:1731–1734. doi: 10.1126/science.2467383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Larder B A, Kellam P, Kemp S D. Convergent combination therapy can select viable multidrug resistant HIV-1 in vitro. Nature (London) 1993;365:451–453. doi: 10.1038/365451a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Larder B A, Kemp S D, Harrigan P R. Potential mechanism for sustained antiretroviral efficacy of AZT-3TC combination therapy. Science. 1995;269:696–699. doi: 10.1126/science.7542804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Larder B A, Kohli A, Kellam P, Kemp S D, Kronick M, Henfrey R D. Quantitative detection of HIV-1 drug resistance mutations by automated DNA sequencing. Nature. 1993;365:671–673. doi: 10.1038/365671a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mayers D L, McCutchan F E, Sanders-Buell E E, Merritt L I, Dilworth S, Fowler A K, Marks C A, Ruiz N M, Richman D D, Roberts C R, Burke D S. Characterization of HIV isolates arising after prolonged zidovudine therapy. J Acquired Immune Defic Syndr. 1992;5:749–759. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Miller, V., A. Phillips, C. Rottmann, S. Staszewski, R. Pauwels, K. Hertogs, M.-P. de Bethune, S. D. Kemp, S. Bloor, P. R. Harrigan, and B. A. Larder. Dual resistance to zidovudine (ZDV) and lamivudine (3TC) in patients treated with ZDV/3TC combination therapy: association with therapy failure. Submitted for publication. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.Nijhuis M, Schuurman R, de Jong D, van Leeuwen R, Lange J, Danner S, Keulen W, de Groot T, Boucher C A B. Lamivudine-resistant human immunodeficiency virus type 1 variants (184V) require multiple amino acid changes to become co-resistant to zidovudine in vivo. J Infect Dis. 1997;176:398–405. doi: 10.1086/514056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ren J, Esnouf R, Garman E, Somers D, Ross C, Kirby I, Keeling J, Darby G, Jones Y, Stuart D, Stammers D. High resolution structures of HIV-1 RT from four RT-inhibitor complexes. Nat Struct Biol. 1995;2:293–302. doi: 10.1038/nsb0495-293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ren, J., R. M. Esnouf, A. L. Hopkins, E. Y. Jones, I. Kirby, J. Keeling, C. K. Ross, B. A. Larder, D. I. Stuart, and D. K. Stammers. AZT drug resistance mutations in HIV-1 RT can induce long range conformational changes. Submitted for publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Richman D D. Resistance of clinical isolates of human immunodeficiency virus to antiretroviral agents. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1993;37:1207–1213. doi: 10.1128/aac.37.6.1207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Richman D D. Resistance, drug failure, and disease progression. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 1994;10:901–905. doi: 10.1089/aid.1994.10.901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rooke R, Tremblay M, Soudeynes H, De Stephano L, Yao X-J, Fanning M, Montaner J S G, O’Shaughnessy M, Gelman K, Tsoukas C, Gill J, Reudy J, Wainberg M A. Isolation of drug resistant variants of HIV-1 from patients on long term zidovudine therapy. AIDS. 1989;3:411–415. doi: 10.1097/00002030-198907000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schinazi R F, Lloyd R M, Jr, Nguyen M H, Cannon D L, McMillan A, Ilksoy N, Chu C K, Liotta D C, Bazmi H Z, Mellors J W. Characterization of human immunodeficiency viruses resistant to oxathiolane-cytosine nucleosides. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1993;37:875–881. doi: 10.1128/aac.37.4.875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schuurman R, Nijhuis M, van Leeuwen R, Schipper P, de Jong D, Collis P, Danner S A, Mulder J, Loveday C, Christopherson C, Kwok S, Sninsky J, Boucher C A B. Rapid changes in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 RNA load and appearance of drug-resistant virus populations in persons treated with lamivudine (3TC) J Infect Dis. 1995;171:1411–1419. doi: 10.1093/infdis/171.6.1411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shi C, Mellors J W. A recombinant retroviral system for rapid in vitro analysis of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 susceptibility to reverse transcriptase inhibitors. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:2781–2785. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.12.2781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36a.Stammers, D. Personal communication.

- 37.Staszewski S, Loveday C, Harrigan P R, Hill A M, Verity L, McDade H the Lamivudine European HIV Working Group. Safety and efficacy of lamivudine-zidovudine combination therapy in zidovudine-experienced patients. JAMA. 1996;276:111–117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tisdale M, Kemp S D, Parry N R, Larder B A. Rapid in vitro selection of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 resistant to 3′-thiacytidine inhibitors due to a mutation in the YMDD region of reverse transcriptase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:5653–5656. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.12.5653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Volberding P A, Lagakos S W, Koch M A, Pettinelli C, Myers M W, Booth D K, Balfour H H, Jr, Reichman R C, Bartlett J A, Hirsch M S, Murphy R L, Hardy W D, Soeiro R, Fischl M A, Bartlett J G, Merigan T C, Hyslop N E, Richman D D, Valentine F T, Corey L the AIDS Clinical Trials Group of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. Zidovudine in asymptomatic human immunodeficiency virus infection. A controlled trial in persons with fewer than 500 CD4-positive cells per cubic millimeter. N Engl J Med. 1990;322:941–949. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199004053221401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]