Abstract

This systematic review aims to examine the differences and similarities between the various types of volunteer mentoring (befriending, mentoring and peer support) and to identify the benefits for carers and volunteers. Literature searching was performed using 8 electronic databases, gray literature, and reference list searching of relevant systematic reviews. Searches were carried out in January 2013. Four studies fitted the inclusion criteria, with 3 investigating peer support and 1 befriending for carers. Quantitative findings highlighted a weak but statistically significant (P =.04) reduction in depression after 6 months of befriending. Qualitative findings highlighted the value carers placed on the volunteer mentors’ experiential similarity. Matching was not essential for the development of successful volunteer mentoring relationships. In conclusion, the lack of need for matching and the importance of experiential similarity deserve further investigation. However, this review highlights a lack of demonstrated efficacy of volunteer mentoring for carers of people with dementia.

Keywords: carer, caregiving, dementia, befriending, peer support, volunteer

Background

Carers

It is estimated that worldwide there are currently 35.6 million people living with dementia, rising to potentially 100 million by 2050. 1 The number of informal, unpaid carers is increasing at a similar rate. 2 Carers of people with dementia are reported to be under more mental and physical strain than carers of other older people. 3 This may be largely due to the extra stress the symptoms of dementia can cause, such as memory loss, communication difficulties, incontinence, decreased mobility, agitation, and aggressive behavior. 4 With this, they are more likely to experience loneliness, social exclusion, and physical and mental health issues. 5 –7 This is of concern, as isolation and loneliness are key contributors to carer stress. 8

Volunteering

There are many reasons for choosing to volunteer. For example, volunteering increases social integration, giving volunteers opportunities to interact with others, which in turn may have a positive impact on mental well-being. 9 Also, social integration, reductions in depression, and improvements in physical health have been highlighted as benefits of volunteering. 10,11 This is supported by Piliavin and Siegl 12 who demonstrated that volunteering is associated with psychological well-being, with those who were less well socially integrated benefitting the most. This finding could be explained by Prouteau and Wolff 13 who focused on understanding the relational motives for the reasons why people volunteer. They found that volunteers expressed a strong desire to make friends and meet people by increasing their social circle through volunteering.

Social Support Interventions

There are a variety of interventions aimed at reducing social isolation and increasing social inclusion for carers. 14 –16 These interventions include a number variously known as befriending, mentoring, and peer support. Greenwood and Habibi17(p10) define mentoring as “a mixture of emotional and social support provided by a non-judgemental outsider.” Similarly, Dean and Goodlad18(p5) define befriending as “A relationship between two or more individuals… the relationship is non-judgemental, mutual, purposeful, and there is a commitment over time.” However, a peer supporter has been described as “… someone who has faced the same significant challenges as the support recipient, (and) serves as a mentor to that individual,”19(p140) highlighting a key difference between peer support, befriending, and mentoring. However, for the purposes of this article, all these interventions will be referred to as volunteer mentoring. Although carers often report isolation and social exclusion, there is little evidence to suggest the types of social interventions that are effective at reducing this. 14 However, there is some evidence for improving well-being, for example, a recent meta-analysis by Mead et al 20 found one-to-one befriending had a modest effect on depression in various patient groups, including carers. However, it should be noted that Mead et al 20 also included studies where paid workers delivered the befriending intervention alongside volunteers. Further to this, peer support, another intervention based on social support, has been shown to have a positive impact on carer well-being. 21

The Importance of This Review

Given the lack of demonstrable efficacy in general of interventions for carers of people with dementia 15,22 and the likelihood that the number of volunteer mentoring schemes will increase, 23 research for their use in this population is warranted. It is important to understand how these schemes operate and what impact, if any, they have on carers and volunteers. Improved understanding of their impact overall should help determine which types of volunteer mentoring (peer support, mentoring or befriending) have the greatest benefits and for whom.

Aims and Research Questions

The aims of this systematic review are to investigate and appraise the empirical evidence for the impact of different types of mentoring schemes on both carers of people with dementia and volunteers. It will identify the current level of knowledge and any gaps in the literature.

This review takes the evidence further than other reviews 20 by focusing specifically on 3 forms of volunteer mentoring (befriending, mentoring, and peer support) and highlighting the similarities and differences between them. Further, this review is not only limited to the impact on mental health of carers (eg, Mead et al 20 ) but also incorporates the impact on social aspects of volunteer mentoring. To provide more focused answers, this review is also limited specifically to volunteers as opposed to professionals delivering a volunteer mentoring intervention for carers of people with dementia.

The specific questions are as follows:

What are the differences and similarities between the different types of mentoring schemes in how they operate? For example, frequency of sessions and length of contact.

What outcomes are investigated for carers and volunteers?

What is the evidence of the impact these interventions have on carers and volunteer mentors?

What is important for successful volunteer mentor and carer relationships?

Methods

To ensure transparency and completeness of the review, the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) checklist 24 was used.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Articles were included if the person being cared for had a diagnosis of dementia, the intervention was delivered by volunteers on a one-to-one basis, and the articles were written in English. Quantitative, qualitative, and mixed method studies were included. Studies were excluded if it was not possible to identify whether the main effects were due to volunteer mentoring; the interventions were not clearly identified as befriending, mentoring, or peer support; or less than 50% of the participants were carers of people with dementia. Review articles, conference papers, and dissertations were also excluded.

Study Identification

An online database search was conducted using Ovid Medline (1946 to January week 2, 2013), Embase (1980 to January week 2, 2013), PsychINFO (1967 to January week 2, 2013), Social Policy and Practice (1981 to January week 2, 2013), Cinahl Plus (1937 to January week 2, 2013), Allied and Complimentary Medicine (1985 to January week 2, 2013), The Social Sciences Citation Index (1970 to January week 2, 2013), and Scopus (1960 to January week 2, 2013). Searches were limited to the English language.

Search strategies consisted of both Medical Subject Heading (MeSH) terms and key words. The search strategy used for Medline was as follows: (the MeSH terms used are reported in italics), (exp caregivers OR caregiver* OR care giver* OR carer*) AND (social support OR voluntary workers OR voluntary programs OR mentors OR telephone OR internet OR befriend* OR peer support* OR mentor* OR voluntary OR volunteer* OR social support* OR psychosocial intervention OR online OR internet OR telephone) AND (depression OR anxiety OR mental health OR mental disorders OR social isolation OR social support OR self concept OR loneliness OR stress, psychological OR quality of life OR depression OR anxiety OR mental health OR social isolation OR social support OR social inclusion OR social exclusion OR self worth OR selfworth OR self esteem OR selfesteem OR burden* OR hopeless* OR quality of life OR stress*) AND (dementia OR dementia, vascular OR Alzheimer disease OR dement* OR Alzheimer* OR vascular dementia).

Reference list searching of relevant identified systematic reviews and of all included studies was undertaken. Gray literature searches were performed using the Alzheimer’s Society Web site, the Mentoring and Befriending Foundation Web site, the AgeUK Web site, the Joseph Rowntree Foundation Web site, Open Grey, the UK Institutional Repository Search and Zetoc. Further, contact was made with 6 experts in the field of research to see whether they could provide any further studies not identified as part of the literature searches.

Quality Assessment

Quality assessment of studies possible for inclusion in the review was undertaken using the QualSyst review tool. 25 This tool was selected because it permits scoring for both qualitative and quantitative studies. Quality scoring was conducted independently by 2 authors (R.S. and N.G.). The few differences in ratings were discussed and consensus was achieved. Quality assessment was used to interrogate the studies, but studies were not excluded based on quality scores.

Data Extraction and Management

Articles were separated into qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods studies. Standardized data extraction forms were developed for all 3 types of study. Data extraction for quantitative studies included author details, year of publication and publication type, participant demographic details, sample size, interventions investigated, outcomes measured, results of intervention (on both carers and volunteers), and key findings. Data extracted for qualitative and mixed method studies were similar to quantitative studies, along with themes being identified.

Results

Electronic Searches

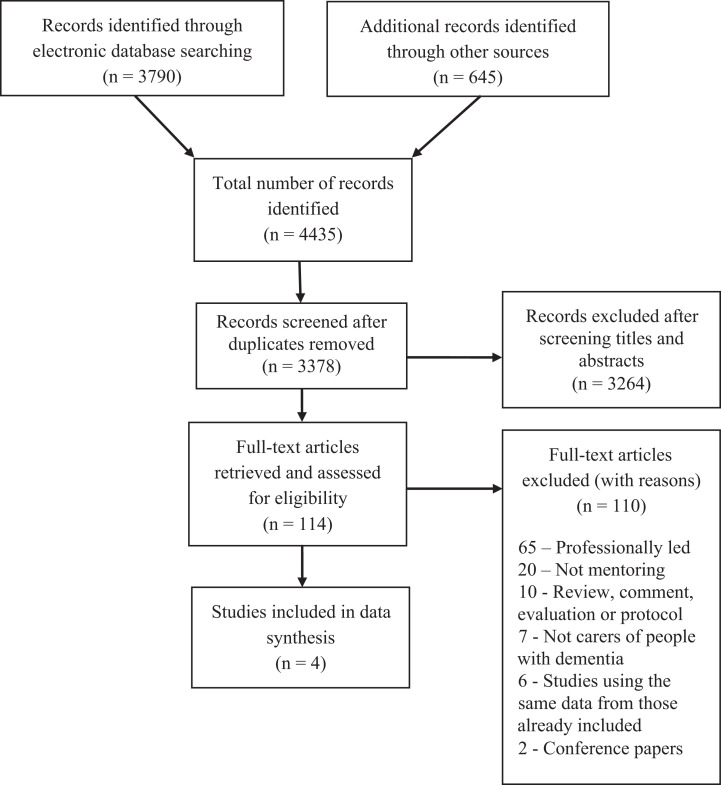

A flow diagram detailing the search results can be seen in Figure 1. Searches were performed in January 2013. A search of Medline revealed 834 results, Embase 1005 results, PsychINFO 657 results, Social Policy and Practice 178 results, Cinahl Plus 380 results, AMED 31 results, Social Sciences Citation Index 652 results, and Scopus 53 results. In total, 3790 titles and abstracts were identified. After 1057 duplicates were removed, the reviewers independently examined the remaining 2733 results and separately compiled a list of references to be examined. From this, 80 full-text articles were then retrieved for closer inspection, and after discussion between reviewers, 4 articles were subsequently included into the review from electronic searching. 26 –29 Reasons for article exclusion are interventions being professionally led, they were not befriending, mentoring, or peer supporting, and they were not for carers of people with dementia. A full breakdown of reasons for article exclusion is available in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram 24 showing the process of including and excluding retrieved articles.

Reference List Searching Retrieved Reviews

A total of 16 literature reviews were retrieved from the electronic database searches and their reference lists hand searched (from this, 51 references were extracted and scrutinized). After the exclusion of repeats, 21 full-text articles were retrieved. None were eligible for inclusion.

Gray Literature Searching

Gray literature searches produced a total of 572 results. Of the 572 results reviewed, 7 full-text documents were sourced and checked for inclusion. Five were scrutinized but excluded for not meeting the inclusion criteria, the final 2 studies were excluded after collaboration between the reviewers.

Contact With Experts in the Field of Research

In all, 6 authors, including the 4 first authors from the included studies, were contacted to ask whether they were aware of any unpublished research relating to mentoring of carers of people with dementia. One author responded and no further studies were identified.

Reference List Searching of Included Studies

From the reference lists of the 4 included studies, 22 references were highlighted for further investigation. 26 –29 Of these, 16 were repeats from either the earlier electronic searches or the reference searching of relevant reviews. Full-text articles of the remaining 6 were retrieved and examined for possible inclusion. All 6 were excluded after comparison with the inclusion criteria.

Included Studies

After discussion between the reviewers, 4 articles were included in the final data synthesis. For ease of reporting, the volunteer mentoring schemes were broken down by type (peer support or befriending).

Characteristics of Included Studies

Of the included studies, 2 studies came from the United States, 27,28 1 from Canada, 29 and 1 from the United Kingdom. 26 Two studies were randomized controlled trials, 26,27 1 observational, 28 and the fourth was qualitative and used content analysis. 29 All but 1 study, 29 which also included carers of stroke survivors, focused exclusively on carers of people with dementia.

A variety of different outcomes were measured. Two studies focused on mental health, 26,27 1 on carer and volunteer mentor similarity and continuation of visits, 28 and the final study investigated the types of support offered by peer volunteers and carer satisfaction with the service received. 29 Two studies focused on face-to-face peer support from the same trial, 27,28 1 on one-to-one telephone peer support, 29 and 1 on one-to-one, face-to-face befriending. 26 Full details of the characteristics and methods of the included studies are available in Tables 1 and 2.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Included Studies.

| Authors (Year Published) and Location [Country] | Aims | Sample Size | No. of Participants | No. of Controls | Carers’ Mean Age in Years (Standard Deviation) | Mentors’ Mean Age in Years (Standard Deviation) | Participant Gender Ratios (M:F, %) | Participant Ethnicity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Charlesworth et al (2008) 26 [UK] | To determine whether access to a befriender facilitator is effective compared with usual care | 236 | 116 | 120 | 68 (11.4) | Not reported | 36:64 | 99% of Participants were white |

| Pillemer and Suitor (2002) 27 [US] | To test whether adding peer support to carers’ social network produces positive outcomes | 147 (115 completers) | 54 | 61 | 58 (Not reported) | Not reported | 29:71 | Not reported |

| Sabir et al (2003) 28 [US] | To identify predictors of successful carer and peer relationships | 114 (57 matched carer and peer supporter pairs) | 114 | Not reported | 62 (Not reported) | 62 (Not reported) | 25:75 | Not reported |

| Stewart et al (2006) 29 [Canada] | Understanding the impact of telephone peer support for carers | 66 (47 were carers of people with dementia) | 66 | N/A | 60 (13.88) | 64 (7.46) | 34:66 | Not reported |

Abbreviations: F, female; M, male; N/A, not available.

Table 2.

Methods of Included Studies.

| Authors (Year Published) | Interventions Investigated | Participants Recruited From | Study Design | Study Period, Weeks | Session Length, Hours | Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria | Outcomes Measured (Data Collection Methods and Scales) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Charlesworth et al (2008) 26 | Befriending | Norfolk and Suffolk (UK) through mail outs from GP surgeries, leaflets sent to relevant organizations, press articles, and presentations | Randomized controlled trial with economic evaluation | 104 | 1 | Carers aged >18, caring for a person with dementia. At least 20 hours a week spent on care-related tasks | Carers with cognitive impairment or terminal illness. Carers of people in permanent residential accommodation | Anxiety and depression (HADS), loneliness (2-item measure), positive and negative affectivity (PANAS), relationship quality (MCBS), coping (COPE), social support (PANT), life events (LTE), health-related quality of life (EQ5-D), resource use (semistructured interviews), perceived social support (MSPSS) |

| Pillemer and Suitor (2002) 27 | Peer support | State University of New York Health Science Centre | Mixed methods. Randomized controlled trial with a qualitative aspect | 8 | 1-2 | Person being cared for had to have a diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease | PWD could not reside in a nursing home at the preintervention interview stage | Depression (CES-D), Self-esteem (RSES), satisfaction with the service (participant interviews) |

| Sabir et al (2003) 28 | Peer support | State University of New York Health Science Centre | Observational study | 8 | 1-2 | PWD had to have a diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease | PWD could not reside in a nursing home at the preintervention interview stage | Number of volunteer visits, continuation of visits postintervention, and quality of carer/peer supporter match |

| Stewart et al (2006) 29 | Telephone peer support | Contact with relevant agencies, posters, presentations to groups, newspaper advertisements and mail outs to relevant organizations and services | Qualitative | 20 | 15-60+ minutes | Carers of a people with dementia or people with stroke | People being cared for who were under the age of 50 | Types of support provided by peer supporters, support processes, perceived intervention impacts, and satisfaction with the intervention |

Abbreviations: CES-D, the Centre for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale; COPE, Coping Orientation for Problem Experience; EQ5-D, EuroQol 5 Dimensions; GP, General Practitioner; HADS, Hospital and Anxiety Depression Scale; LTE, List of Threatening Experiences; MCBS, Mutual Communal Behaviours Scale; MSPSS, Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support; PANAS, Positive and Negative Affect Schedule; PANT, Practitioner Assessment of Network Type; PWD, person with dementia; RSES, Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale.

Methodological Quality of Included Studies

The result and overall quality scores of included studies can be seen in Table 3. The maximum possible score is 100. The average quality score across all 4 studies was 75. Charlesworth et al 26 received a score of 100, Pillemer and Suitor 27 scored 71, while both Sabir et al 28 and Stewart et al 29 scored 65. The quantitative studies scored more highly than the qualitative study, averaging a score of 79 compared to 65. The main issues with the quantitative studies tended to be the omission of estimates of variance 27,28 and blinding procedures. 27 The main quality issues with Stewart et al’s 29 study were lack of verification procedures and omission of an account of reflexivity. Of the 4 studies, 3 described attrition, 26,27,29 but only Charlesworth et al 26 and Stewart et al 29 documented reasons for participant withdrawal. Attrition ranged 19%, 26 22% 27 and 30%. 29 The lack of attrition data for Sabir et al 28 means it is not known whether participant withdrawals were excluded from the analysis, increasing the chances of bias.

Table 3.

Results of Included Studies.

| Authors (Year Published) | Results of Interventions on Carers | Results of Interventions on Volunteers | Themes Identified (Qualitative and Mixed Methods Studies) | Measure Used to Rate Participant Withdrawals | Number of Participants Who Withdrew, n (%) | Conclusions | Quality Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Charlesworth et al (2008) 26 | No statistically significant effect across the outcomes measured | Not reported | N/A | Reasons for participant withdrawal included the death of the carer and carer ill health | 46 (19%) | Befriending for carers of people with dementia is not an effective intervention | 100 |

| Pillemer and Suitor (2002) 27 | No positive effects were found for either depression or self-esteem | Not reported | Experiential similarity. Sharing experiences with someone who has been through something similar was seen as highly important to carers | Not reported | 32 (22%) | Peer support for carers of people with dementia is not an effective intervention | 71 |

| Sabir et al (2003) 28 | No statistically significant difference found for carer and peer supporter similarity and number of visits made | Not reported | N/A | Not reported | Not reported | Extensive matching criteria are not essential for a successful peer support intervention for carers of people with Alzheimer’s disease | 65 |

| Stewart et al (2006) 29 | Increased satisfaction with support, coping skills, caregiving competence, confidence, and decreased burden and loneliness | Not reported | Carers knowing that they are not alone. Having someone there who understands what they are going through. Experiential similarity is seen as important | Reasons for participant withdrawal included ill health of the person cared for and carer constraints | 20 (30%) | Use of telephone peer support provides an accessible, cost-effective and efficient means of communication to carers | 65 |

Abbreviation: N/A, not available.

Peer Support

Two studies investigated face-to-face peer support, reporting different findings from the same trial (Pillemer and Suitor 27 and Sabir et al 28 ). The volunteers who took part in the trial needed to have prior caring experience. One study was quantitative with a qualitative element. 27 These primarily quantitative face-to-face peer support studies looked at different outcomes, and neither found statistically significant effects. Pillemer and Suitor 27 found no positive improvements in either depression or carer self-esteem. However, after secondary analysis, peer support was found to have a modest buffering effect on depressive symptoms for carers experiencing the most stressful situations. The qualitative data described by Pillemer and Suitor 27 highlighted that carers expressed experiential similarity as one of the most positive features of the intervention. This was also found by Sabir et al 28 who showed that carers were more likely to have successful peer support relationships and to continue meeting after the intervention ended, if they were similar on the shared experience of caring. Extensive matching criteria were not found to influence a successful peer support relationship. Despite both studies showing experiential similarity as potentially having a positive impact on peer support relationships, the overall finding is that peer support for carers of people with dementia is not an effective intervention.

Although the quantitative studies mostly reported no impact of face-to-face peer support, the qualitative study by Stewart et al 29 suggested telephone peer support was beneficial. This study focused on telephone peer support for carers of people with dementia and stroke survivors and showed an increase in coping skills and caregiving competence and a decrease in loneliness and reliance on other forms of social support. Carers also reported receiving emotional support from telephone peer supporters. This was seen as vital as carers reported losing support from family and friends following diagnosis of the person with dementia. Most of the positive impacts were perceived to come from peer supporters’ experiential knowledge of the carers’ situation. Experiential similarity was seen as highly important. Overall, it was concluded that telephone peer support provides accessible, cost-effective, and beneficial support for carers.

Befriending

Of the 4 included studies, 1 study 26 investigated face-to-face befriending. Carers were offered access to a befriending facilitator, with approximately half the carers taking up the service. Volunteer befrienders did not need prior caring experience. Befriending lasted between 6 and 24 months. Overall, there were no statistically significant benefits of the intervention over the control group for either psychological well-being or cost-effectiveness. No improvement was found for carers in the intention-to-treat population, as measured by the Hospital and Anxiety Depression Scale (P =.71). However, carers receiving the befriending intervention for at least 6 months reported a statistically significant improvement in depression scores at 15 months (P =.04). In addition, across the secondary outcomes, there were no statistically significant positive effects for the intervention over the control and there was no evidence for the cost-effectiveness for befriending. It was concluded that access to a befriender facilitator was not an effective intervention. However, it was suggested that future research into befriending schemes is warranted due to the trend for a statistically significant reduction in depression after 6 months.

Discussion

This review highlights both the paucity of studies and the inconsistent findings in the available research for the effectiveness of volunteer mentoring schemes for both carers of people with dementia and volunteers. This is a concern, as it is likely these schemes will increase in number. 23 It also highlighted the differences in qualitative and quantitative findings. Although the quantitative results largely showed no impact of volunteer mentoring, qualitative findings suggested carers value the support the schemes can give and the experiential similarity of the volunteers. Overall, the findings of this review are in line with previous research, which highlights a lack of demonstrated efficacy for interventions for carers of people with dementia. 22 However, the results suggesting the importance of experiential similarity for carers have also been reported elsewhere, 30,31 making this an important area for further exploration.

Differences in How the Schemes Operate

There appears to be similarities between befriending 26 and peer support 27 –29 in terms of how the schemes operate. Typically, interventions last for 1 hour and take place once a week, although telephone peer support may allow carers and volunteers more flexibility over when and how long mentoring sessions last. 29 The most notable difference between the schemes is that peer support requires volunteers to have prior caring experience, whereas befriending does not. However, as few studies were identified, caution is needed when comparing these types of mentoring schemes.

Impact on Carers and Volunteers

The studies investigated numerous outcomes including depression, anxiety, perceived social support, self-esteem, number of volunteer visits, and satisfaction. Quantitative studies of befriending and peer support were shown to be ineffective in reducing mental health issues and loneliness in carers. 26,27 However, the qualitative study 29 showed that carers reported reduced burden and loneliness, both of which have been correlated with levels of stress and mental health issues. 5,8 Further research could help clarify the reasons for this finding. It is possible that the study by Stewart et al, 29 which focused on telephone peer support, offered a more flexible and effective means of communication and support with carers, leading to better outcomes. However, the differences in research design could be an issue, as research has highlighted participants reporting more positively or negatively depending on how the data are collected. 32

The small but significant difference shown in depression scores at 15 months for carers who received befriending for at least 6 months 26 could indicate that the benefits of befriending might not be immediate, and therefore more longitudinal studies are needed. Also, it is possible that the use of validated outcome scales 26,27 may not be focusing on the aspects of volunteer mentoring which are most important to carers. This could, in part, explain the differences found between the quantitative and the qualitative investigations.

Although there have been a number of benefits attributed to volunteering, 12 none of the studies included here investigated the impact of volunteering on befrienders, mentors, or peer supporters, making it an important area for future exploratory investigations.

Developing Successful Carer and Volunteer Mentor Relationships

The development of successful mentoring relationships was also thought to be associated with the experiential similarity of volunteer mentors. The importance of this was reported by 3 of the included studies. 27 –29 In particular, Sabir et al 28 reported that it was not essential to implement extensive matching criteria prior to pairing carers and mentors, but it was important that mentors had previous experience of caring. In fact, it was shown that dissimilar pairs had more contact than pairs matched across a wide range of demographics. In this review, the finding of the importance of experiential similarity is consistent with the findings from previous research 30,31 and highlights that extensive matching criteria are not needed. However, more research is needed to explore what it is about experiential similarity that makes it important in mentoring relationships.

Limitations of Included Studies and Their Possible Impact on Findings

The level of participant withdrawal from both the research and the interventions is of concern. Stewart et al 29 reported 30% withdrew over the course of the 20-week study period, considerably more than the studies by Charlesworth et al 26 (19%) or Pillemer and Suitor 27 (22%). The 2 studies that did report reasons for participant withdrawal from the research highlighted ill health of the carers as an overriding factor. The high level of withdrawal from the Stewart et al’s 29 study needs to be taken into consideration when examining the results. Attrition bias could have led to only the healthiest carers or those coping best completing the study. Also, although the authors noted that dissatisfaction with the peer support was not cited as a reason, it is possible that claiming ill health rather than dissatisfaction might have been seen as a more acceptable explanation for carers to give. Improved understanding of the processes of mentoring from the carers’ and volunteers’ perspectives may help identify difficulties they may experience during mentoring, which may at least be partially responsible for some of the withdrawals.

Second, the low uptake of the schemes limits the generalizability of the results. Charlesworth et al 26 reported low uptake of befriending by carers despite having access to a befriender facilitator. Those who did take part for 6 months or more showed some improvements in depression scores over the control group. This low uptake needs further investigation to understand why it occurs and whether it is a reflection of the general reluctance carers have in accepting support. 33

Strengths and Limitations of the Review

The main strength of this review is the inclusive study design, the large body of literature that was examined from a number of different sources, and its specific focus. Earlier reviews have been more generally focusing on the impact of support schemes for carers of people with dementia. 6,20

A main limitation is the dearth of published and unpublished research, which resulted in only 4 studies being included. Although this highlights a lack of research in this field, it influences the power of the conclusions that can be drawn from the results. A second limitation is that only articles published in English were included, which could have led to potentially important studies being missed.

Future Directions

Given the lack of clarity in terms of differences and similarities between the different types of volunteer mentoring schemes, further research is required. This is potentially an important area of future research to help understand the models of mentoring that work best, possibly leading to more effective schemes being offered. This could include comparisons of volunteer mentoring with similar interventions that are professionally led. No studies investigated the impact of volunteering on the volunteer mentors. Given the evidence that there could be a positive impact on volunteers’ well-being, 9,11,12 future research is needed to identify the impact, if any, on volunteers providing volunteer mentoring. Furthermore, the potential impact on the person with dementia is worthy of investigation.

Conclusions

There is little quantitative evidence that volunteer mentoring improves outcomes for carers of people with dementia. However, qualitative evidence shows carers value volunteer mentoring and opportunities to talk about their experiences. The lack of need for matching and the importance of experiential similarity are significant issues deserving further investigation. However, overall the findings of this review are in line with previous research that highlights a lack of demonstrated efficacy for interventions for carers of people with dementia.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Professor Vari Drennan and Professor Ann Mackenzie for their guidance in the development of this article.

Footnotes

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1. World Health Organisation. Dementia: A Public Health Priority. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Knapp M, Prince M, Albanese E, et al. Dementia UK: The Full Report. London. 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Moise P, Schwarzinger M, Um M. Dementia Care in 9 OECD Countries: A Comparative Analysis, OECD Health Working Paper No. 13. Paris: OECD; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Alzheimer’s Society. The later stages of dementia, Factsheet 417. London: Alzheimer's Society; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Beeson RA. Loneliness and depression in spousal caregivers of those with Alzheimer’s disease versus non-caregiving spouses. Arch Psychiat Nurs. 2003;17(3):135–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Etters L, Goodall D, Harrison BE. Caregiver burden among dementia patient caregivers: a review of the literature. J Am Acad Nurse Pract. 2008;20(8):423–428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Pinquart M, Sorensen S. Associations of stressors and uplifts of caregiving with caregiver burden and depressive mood: a meta-analysis RID B-1070-2008. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2003;58(2):P112–P128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Leggett AN, Zarit S, Taylor A, Galvin JE. Stress and burden among caregivers of patients with Lewy body dementia. Gerontologist. 2010;51(1):76–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Choi NG, Bohman TM. Predicting the changes in depressive symptomatology in later life—How much do changes in health status, marital and caregiving status, work and volunteering, and health-related behaviors contribute? J Aging Health. 2007;19(1):152–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Casiday R, Kinsman E, Fisher C, Bambra C. Volunteering and Health: What Impact Does it Really Have? Lampeter, England: University of Wales; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Musick MA, Wilson J. Volunteering and depression: the role of psychological and social resources in different age groups. Soc Sci Med. 2003;56(2):259–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Piliavin JA, Siegl E. Health benefits of volunteering in the Wisconsin longitudinal study. J Health Soc Behav. 2007;48(4):450–464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Prouteau L, Wolff FC. On the relational motive for volunteer work. J Econ Psychol. 2008;29(3):314–335. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Stoltz P, Uden G, Willman A. Support for family carers who care for an elderly person at home—a systematic literature review. Scand J Caring Sci. 2004;18(2):111–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Thompson CA, Spilsbury A, Hall J, Birks Y, Barnes C, Adamson J. Systematic review of information and support interventions for caregivers of people with dementia. BMC Geriatr. 2007;7(18):1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Cattan M, Kime N, Bagnall AM. The use of telephone befriending in low level support for socially isolated older people—an evaluation. Health Soc Care Comm. 2011;19(2):198–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Greenwood N, Habibi R. Carer mentoring: a mixed methods investigation of a carer mentoring service. Int J Nurs Stud. 2013. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu. Accessed June 11, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Dean J, Goodlad R. The Role and Impact of Befriending. York, England: Joseph Rowntree Foundation; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Sherman JE, DeVinney DJ, Sperling KB. Social support and adjustment after spinal cord injury: influence of past peer-mentoring experiences and current live-in partner. Rehabil Psychol. 2004;49(2):140–149. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Mead N, Lester H, Chew-Graham C, Gask L, Bower P. Effects of befriending on depressive symptoms and distress: systematic review and meta-analysis. Brit J Psychiatry. 2010;196(2):96–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Veith EM, Sherman JE, Pellino TA, Yasui NY. Qualitative analysis of the peer—mentoring relationship among individuals with spinal cord injury. Rehabil Psychol. 2006;51(4):289–298. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Arksey H. Scoping the field: services for carers of people with mental health problems. Health Soc Care Comm. 2003;11(4):335–344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Department of Health. Living Well with Dementia: A National Dementia Strategy. London, England: Crown; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kmet LM, Lee RC, Cook LS. Standard Quality Assessment Criteria for Evaluating Primary Research Papers From a Variety of Fields. Alberta, Canada: HTA; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Charlesworth G, Shepstone L, Wilson E, Thalanany M, Mugford M, Poland F. Does befriending by trained lay workers improve psychological well-being and quality of life for carers of people with dementia, and at what cost? A randomised controlled trial. Health Technol Asses. 2008;12(4):iii, v–ix, 1–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Pillemer K, Suitor JJ. Peer support for Alzheimer's caregivers: is it enough to make a difference? Res Aging. 2002;24(2):171–192. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Sabir M, Pillemer K, Suitor J, Patterson M. Predictors of successful relationships in a peer support program for Alzheimer's caregivers. Am J Alzheimers Dis. 2003;18(2):115–122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Stewart M, Barnfather A, Neufeld A, Warren S, Letourneau N, Liu L. Accessible support for family caregivers of seniors with chronic conditions: from isolation to inclusion. Can J Aging. 2006;25(2):179–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Pillemer K, Suitor JJ. 'It takes one to help one': effects of similar others on the well-being of caregivers. J Gerontol B-Psychol. 1996;51(5):S250–S257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Suitor JJ, Pillemer K, Keeton S. When experience counts: the effects of experiential and structural similarity on patterns of support and interpersonal stress. Soc Forces. 1995;73(4):1573–1588. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Greenwood N, Key A, Burns T, Bristow M, Sedgwick P. Satisfaction with in-patient psychiatric services. Relationship to patient and treatment factors. Brit J Psychiat. 1999;174:159–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. McCabe B, Sand B, Yeaworth R, Nieveen J. Availability and utilisation of services by Alzheimer’s disease caregivers. J Gerontol Nurs. 1995;21(1):14–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]