Abstract

Borrelia burgdorferi (Bb), the agent of Lyme disease, is a zoonotic spirochetal bacterium that depends on arthropod (Ixodes ticks) and mammalian (rodent) hosts for its persistence in nature. The quest to identify borrelial genes responsible for Bb's parasitic dependence on these two diverse hosts has been hampered by limitations in the ability to genetically manipulate virulent strains of Bb. Despite this constraint, we report herein the inactivation and genetic complementation of a linear plasmid-25-encoded gene (bbe16) to assess its role in the virulence, pathogenesis, and survival of Bb during its natural life cycle. bbe16 was found to potentiate the virulence of Bb in the murine model of Lyme borreliosis and was essential for the persistence of Bb in Ixodes scapularis ticks. As such, we have renamed bbe16 a gene encoding borrelial persistence in ticks (bpt)A. Although protease accessibility experiments suggested that BptA as a putative lipoprotein is surface-exposed on the outer membrane of Bb, the molecular mechanism(s) by which BptA promotes Bb persistence within its tick vector remains to be elucidated. BptA also was shown to be highly conserved (>88% similarity and >74% identity at the deduced amino acid levels) in all Bb sensu lato strains tested, suggesting that BptA may be widely used by Lyme borreliosis spirochetes for persistence in nature. Given Bb's absolute dependence on and intimate association with its arthropod and mammalian hosts, BptA should be considered a virulence factor critical for Bb's overall parasitic strategy.

Borrelia burgdorferi (Bb), the causative agent of Lyme disease (Lyme borreliosis), is a zoonotic organism that transitions between its arthropod (Ixodes ticks) and mammalian (rodent) hosts (1). Much research has highlighted the adaptive responses of the bacterium as it transitions between these diverse environments. Most notable is the reciprocal expression patterns of the two plasmid-encoded outer surface lipoproteins (Osp)A and OspC as Bb migrates from the tick midgut to a mammalian host (2–5). OspA has been shown to be essential for tick colonization (6), and OspC is crucial for events associated with the migration of Bb from tick midguts to salivary glands and subsequent transmission into the mammalian host (7).

Although it is clear that the survival and virulence of Bb depends on certain of its numerous plasmids [i.e., linear plasmid (lp)54, lp25, and lp28–1 and circular plasmid (cp)26] (6, 8–12), other than OspA and OspC, little is known regarding additional plasmid-encoded proteins that are essential for Bb's transition between, or survival within, its tick or mammalian hosts. Attempts to elucidate plasmid loci that confer virulence or survival within each host have been hampered by the intractability of virulent strains of Bb to genetic manipulation (13, 14). Nonetheless, with recent advancements in genetic tools for borrelial research, we report here the genetic inactivation of two plasmid-encoded loci (bba36 and bbe16) to assess their respective roles in the virulence, pathogenesis, and/or survival of Bb during its natural life cycle. bba36 and bbe16 were targeted for study because (i) they reside on the two virulence-associated plasmids lp54 and lp25, respectively, and (ii) they were differentially regulated when assessed in microarray analyses (15). Herein, we provide experimental evidence that not only does bbe16 potentiate virulence of the spirochete in the mammalian host, but it also subserves an essential function for the maintenance of Bb within the Ixodes tick vector. This study has, thus, identified a gene responsible for borrelial persistence in ticks (bptA) that is critical for survival of the bacterium within the tick host and therefore within the natural life cycle of the Lyme disease spirochete. Whereas our data demonstrate that bptA is essential for the survival of Bb sensu stricto in ticks, we also show that bptA is conserved among sensu lato strains of Bb. This widespread conservation among sensu lato strains suggests that bptA may be widely used by Lyme disease spirochetes for persistence in nature.

Materials and Methods

Bacterial Strains and Growth Conditions. All bacterial strains used in this study are listed in Table 4, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site. A low-passage, nonclonal, infectious isolate of Bb strain 297 (16) (PL133) was used for all experiments. PL133 was isolated from mouse ear punch biopsies after multiple rounds of needle challenges of mice with strain 297. Analysis has shown that PL133 retains all known strain 297-specific plasmids (as determined by PCR, see ref. 17), has virulence traits and elicits histopathology virtually identical to its parental 297 strain, and is moderately transformable (A.T.R., J.S.B., K.E.H., and M.V.N., unpublished data). Unless otherwise indicated, borreliae were cultivated in Barbour–Stoenner–Kelley (BSK)-H complete medium (Sigma) at 37°C. Conditions for adaptation to various culture temperatures, pH, and within dialysis membrane chambers implanted into rat peritoneal cavities were described in refs. 18 and 19 (see Supporting Materials and Methods, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). Medium used for selection was supplemented with 50 μg/ml streptomycin or 170 μg/ml kanamycin. Analysis of virulence was performed by culturing spirochetes in BSK-H medium supplemented with Borrelia antibiotic mixture (Sigma) from an ear-punch biopsy 2 weeks after infection of the mouse (Supporting Materials and Methods) (20). Escherichia coli XL1-Blue (Stratagene) and E. coli RosettaBlue (Novagen) were used for propagation of all recombinant constructs and for recombinant protein expression, respectively. Bb sensu lato and relapsing fever strains are listed in Table 4 (21–27). Borrelia lonestari DNA (28) was provided by Susan Little (University of Georgia, Athens).

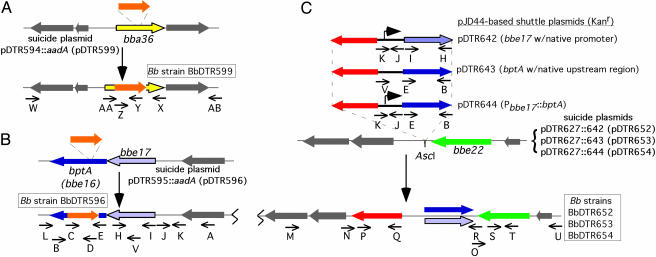

Construction of Suicide Plasmids Containing Disrupted Genes. Plasmid pGEM-Teasy (Promega) was used as the basis for all suicide vector constructions. To generate the bba36 knockout construct (Fig. 1A), a 3,342-bp fragment containing bba36 was obtained by PCR amplification from strain 297 genomic DNA (Expand High-Fidelity PCR system, Roche). All plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 5, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site. All primers (Table 6, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site) were based on available Bb B31 DNA sequence information at the Institute of Genomic Research (29, 30). The bba36 gene was disrupted by insertion of the streptomycin (aadA) antibiotic resistance marker (from pKFSS1) (31) into the unique HpaI restriction site to yield pDTR599. To generate the bptA (bbe16) knockout construct (Fig. 1B), a 2,442-bp fragment containing bptA was generated (as described above) and bptA then was interrupted with the aadA marker at the unique SwaI restriction site to yield pDTR596. Constructs were transformed into PL133 cells that were made electrocompetent essentially as described (32, 33) with slight modifications (Supporting Materials and Methods).

Fig. 1.

Plasmid and strain construction. Color coding for the arrows denoting plasmids and strains is as follows: orange, aadA marker; yellow, bba36; purple, bptA (bbe16); blue, bbe17; red, aph[3′]-IIIa; and green, bbe22. Regular type, shuttle plasmids; bold letters, suicide plasmids; boxed, Bb strains. (A) Inactivation of bba36 in Bb (PL133). The region surrounding bba36 was amplified by using primers W and AB, cloned, and subsequently disrupted by insertion of an aadA cassette [streptomycin resistance (Strepr)] into the unique HpaI site (yielding the suicide plasmid pDTR599). (B) Inactivation of bptA on lp25 in PL133. The region surrounding bptA was amplified by using primers A and L, cloned, and disrupted by insertion of the aadA cassette into the unique SwaI site (yielding the suicide plasmid pDTR596). (C) Cis-complementation in BbDTR596. A wild-type copy of bptA or bbe17 was integrated into lp25 downstream of bbe22 (a site ≈4 kb removed from the native positions of bptA or bbe17). Selection for each construct was predicated on the cointegration of aph[3′]-IIIa [kanamycin resistance (Kanr)]. Three different cis-complementation constructs were used; pDTR652 and pDTR653 had bbe17 and bptA, respectively, driven by promoters contained within the native DNA region upstream of each locus (≈300 bp), whereas bptA was driven by the bbe17 promoter in construct pDTR654. Only the relevant regions of each construct are shown.

Construction of Shuttle and Suicide Plasmids for Genetic Complementation. Three shuttle plasmid versions were generated in pJD44 [a kanamycin-resistant (aph[3′]-IIIa) derivative of pBSV2 (34, 35)] to complement the bptA mutant (BbDTR596) in trans: (i) bptA under its native promoter (pDTR643), (ii) bbe17 under its native promoter (negative control, pDTR642), and (iii) Pbbe17::bptA (pDTR644) (control for promoter used in pDTR652). Construction was performed by insertion of a PCR-generated amplicon into the unique BglII and HindIII sites of the multiple cloning site. Transformation of the bptA mutant (BbDTR596) using each of these three shuttle vectors was unsuccessful. Consequently, a cis-complementation approach then was conceived and implemented as follows. First, each of the relevant regions (insert along with the antibiotic resistance marker) of the shuttle constructs (pDTR643, pDTR642, and pDTR644) was subcloned into pDTR627 to generate the suicide plasmids pDTR653, pDTR652, and pDTR654, respectively (Fig. 1C). Subcloning was accomplished by excision of the multiple cloning site and antibiotic resistance marker by digestion with AscI, and insertion into the unique AscI site downstream of the plasmid-encoded nicotinamidase pncA in pDTR627. When these suicide constructs were transformed into BbDTR596 (as above), homologous recombination with lp25 generated cis-complemented strains of BbDTR596. Individual clones were isolated and evaluated for (i) retention of the original bptA mutation present in BbDTR596 and (ii) the lp25 insertion from the complementation construct. Clones then were pooled (≤5 clones per pool) and injected intradermally via needle challenge into naïve C3H mice at a dose of >2.5 × 105 per clone (36). Bacteria were recovered from ear-punch biopsies cultured in BSK-H medium (37). Recovered bacteria were then frozen and designated as passage-zero (P0) for each strain.

PCR and Immunofluorescence Analysis (IFA) of Infected Ticks. To obtain Ixodes scapularis ticks infected with various strains of Bb, ≈200 pathogen-free larvae were allowed to feed on infected (needle-inoculated) mice, as described in ref. 38 (Supporting Materials and Methods). The isolation and detection of Bb DNA by PCR within engorged or flat ticks were similar to that reported in ref. 39 (Supporting Materials and Methods). For evaluation of intact borreliae in ticks by means of IFA, infected larvae or nymphs were dissected by expressing the hemolymph, midgut, and salivary glands from the tick exoskeleton onto CSS-100 silylated slides (CEL Associates, Pearland, TX) containing 50 μl of PBS with 10 mM MgCl2. Samples were then fixed for IFA (Supporting Materials and Methods). Samples were observed for Bb by using a fluorescence microscope with a 200× objective and filter sets for FITC and rhodamine.

Results

Cloning and Disruption of bba36 and bptA. An infectious, nonclonal isolate of strain 297 (PL133) that was isolated from ear-punch biopsies after repeated rounds of needle inoculation of mice was used as the parental strain for all mutant constructions. This strain was selected because it (i) was more readily transformable than other strain 297-derived clones, (ii) contained all known strain 297-specific plasmids, (iii) was virulent at wild-type levels (ID50 < 100), and (iv) elicited histopathological sequelae typical of disease progression in mice. To assess the role of BBA36 or BptA in the life cycle of Bb, each cognate gene and its appropriate flanking regions were PCR-amplified (based on B31 sequence information), inserted into pGEM-Teasy, and disrupted by insertion of the streptomycin resistance marker (aadA) into unique restriction enzyme sites within each gene. The constructs [Fig. 1 A, bba36 (pDTR599), and B, bptA (pDTR596)] were electroporated into PL133. Clones for each mutation were obtained and confirmed for insertional inactivation of the respective gene and retention of endogenous plasmids (Figs. 4A and 5A, which are published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). Two bba36-deficient mutants (with different plasmid profiles: clone P1C5 lacked cp32-6 and clone P2D6 lacked lp5, cp18-2, and cp32-4) and one bptA mutant (lacking cp18-2 and cp32-4) were selected and further evaluated (Figs. 4B and 5B). All Bb mutants displayed normal growth kinetics in BSK-H medium when grown in vitro at two different conditions (pH 7.5 or 6.8, both at 37°C) (Fig. 6, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site) and exhibited spirochetal morphology identical to PL133 (data not shown).

Evaluation of the bba36 and bptA Mutants for Virulence and Pathogenesis After Needle Inoculation of Mice. To evaluate whether the loss of bba36 or bptA adversely affected the virulence or pathogenicity of Bb, all mutants were subjected to ID50 analysis (Table 1). Mice were needle-challenged intradermally with 101 to 104 mutant or wild-type bacteria. After 2 weeks, ear-punch biopsies were taken and tissues were placed into BSK-H medium without selection; the outgrowth of bacteria was assessed 2 weeks later. Whereas the bba36 mutant did not show an increase in the ID50 in comparison with its parental PL133, the ID50 for the bptA mutant was reproducibly one to two logarithms higher than that of PL133 (P < 0.05), suggesting a significant attenuation of virulence. However, upon histopathological analysis of the mice inoculated with 103 bacteria that were positive for spirochetes, there were no discernable differences in the levels of carditis or arthritis for any of the mutants (bba36 or bptA) compared wth PL133-infected mice (Fig. 7, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). Of note, spirochetes from ear-punch biopsies of mice used for histopathological assessments (and that were cultivated in the absence of antibiotic selection) maintained their mutant genotypes, indicating that the histopathology elicited was not due to genotypic reversion to wild-type character (Figs. 4C and 5C).

Table 1. Determination of ID50 values for PL133 and various mutants and complemented strains of Bb in C3H mice.

| Strain | 104 | 103 | 102 | 101 | ID50 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PL133 (WT) | 10/10 | 10/10 | 7/10 | 3/10 | 44.9 ± 1.41 |

| BbDTR599-P1C5 (bba36-) | 5/5 | 2/2* | 4/5 | 0/5 | 51.3 ± 1.75 |

| BbDTR599-P2D6 (bba36-) | 5/5 | 5/5 | 4/5 | 0/5 | 53.3 ± 1.72 |

| BbDTR596 (bptA-) | 10/10 | 7/10 | 0/10 | 0/10 | 659 ± 1.48† |

| BbDTR652 (bptA-/-, bbe17+/+) | 10/10 | 9/10 | 4/10 | 0/10 | 238 ± 1.41† |

| BbDTR653 (bptA-/+) | 10/10 | 10/10 | 8/10 | 4/10 | 31.3 ± 1.39 |

Three mice died before completion of experiment.

Statistically significant difference from PL133 and BbDTR653 (P values reported in text).

To establish that the reduction in virulence by the bptA mutant was the result of bptA gene disruption and not due to spurious mutations, the deficiency was restored by means of complementation with a wild-type copy of bptA. Initial trans-complementation attempts with a shuttle plasmid failed to yield transformants (data not shown). Therefore, we developed and used a new method of cis-complementation that employed a suicide vector for the integration of exogenous DNA into an innocuous site (see below) in lp25 distant (≈4 kb) from the native bptA (bbe16) gene (Fig. 1C). Advantages to this approach are twofold: (i) integration minimized undesirable gene dosage (i.e., copy number) effects and (ii) integration simultaneously assured retention of lp25. Transformants arising from the recombination of the bptA complementation constructs into lp25 (Fig. 1C) were assessed for appropriate insertions and plasmid profiles (Fig. 5 A and B). As a result of complementation, BptA synthesis was restored (Fig. 5D). In addition, the virulence of the complemented clone BbDTR653 (bptA mutant complemented with bptA under its native promoter) was restored to wild-type levels (Table 1). To confirm that the wild-type level of virulence displayed by BbDTR653 was due to reestablishing bptA expression and not due to the insertion of extraneous DNA into lp25, a construct of bbe17 driven by its native promoter (BbDTR652) was transformed into BbDTR596 in lieu of bptA. The ID50 of BbDTR652 was similar to the bptA mutant and statistically lower than that for either PL133 or BbDTR653 (P < 0.05), indicating that virulence was restored only by the integration of a wild-type copy of bptA. To show that the bbe17 native promoter was active, the bbe17 promoter was fused to bptA in another construct (BbDTR654). As for BbDTR653, the virulence of clone BbDTR654 was restored to a level similar to PL133 (data not shown).

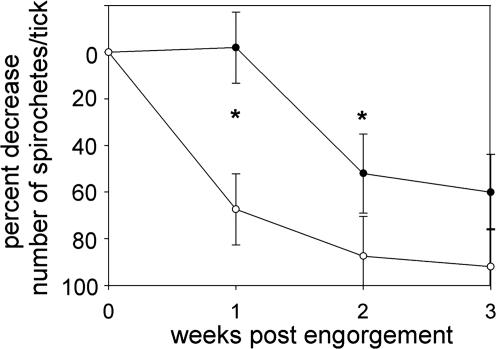

Evaluation of the Roles for bba36 or bptA in Ticks. Because infection of and survival within the mammalian host represents only one facet of the spirochete's enzootic life cycle, a more comprehensive evaluation of the behavior of these Bb mutants in the tick vector was warranted. To perform such an evaluation, sterile larval ticks were allowed to feed on mice that were infected at high spirochete levels (0.5 × 106 to 1 × 106) with either the wild-type, mutant, or complemented strains. Upon larval repletion, the majority of the ticks were allowed to proceed naturally through the month-long molting process, and a subset was dissected for IFA. For each bacterial strain, a large proportion (≥70%) of all repleted larvae was positive for spirochetes (Table 2). There was no statistical difference in the average number of bacteria per fed larva for all strains (data not shown). Upon subsequent evaluation of newly molted nymphs, bba36 deficiency did not affect survival of the spirochetes at any point within the tick host, including when nymphs were allowed to take a blood meal (Table 2). In contrast, the bptA mutant displayed a dramatic defect for survival within newly molted flat nymphal ticks; IFA showed a sharp reduction in both the number of infected ticks (P < 0.016) as well as the number of spirochetes per tick (P < 0.0001) in comparison with PL133 (Table 2). When the bptA mutant (BbDTR596) was complemented with wild-type bptA (BbDTR653), the percentage of ticks remaining infected after molting was restored to levels typically observed for ticks harboring wild-type PL133 (Table 2). The complemented strain (BbDTR653) also regained the ability to sustain spirochetal numbers through the molting process (P < 0.044), albeit not quite to wild-type levels (Table 2). Of note, levels of wild-type PL133 dropped normally (40) in fed larvae during the 4- to 5-week time frame between larval tick engorgement and metamorphosis to the nymphal form (Fig. 2), whereas the bptA deficiency resulted in an accelerated loss of spirochetes within the first 2 weeks post-repletion (Fig. 2).

Table 2. IFA and PCR detection of various Bb clones harbored within larval and nymphal forms of I. scapularis ticks over time.

| Larvae (engorged)

|

Newly molted nymphs (flat)

|

Two-month-old nymphs (flat)

|

Two-month-old nymphs (engorged)

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strain | Genotype | Pos. by IFA,*† % | Pos. by IFA,† % | Bacteria/tick,†n | Pos. by IFA,† % | Pos. by IFA,† % | Pos. by PCR,‡n |

| PL133 | Wild-type | 92 | 90 | 2,146 ± 1,049 | 100 | 73 | 70 |

| BbDTR599-P1C5 | bba36- | 70 | 60 | 1,683 ± 1,202 | 62 | 50 | 48 |

| BbDTR599-P2D6 | bba36- | 100 | 90 | 2,057 ± 1,108 | 88 | 92 | 90 |

| BbDTR596 | bptA- | 90 | 20§ | 1.4 ± 3.8¶ | 16§ | 0§ | 0§ |

| BbDTR652 | bptA-/-, bbe17+/+ | 93 | 6.6§ | 2 ± 7.75¶ | 10§ | 0§ | ND |

| BbDTR653 | Native promoter bptA-/- | 100 | 93 | 415 ± 609 | 80 | 70 | ND |

| BbDTR654 | bbe17 promoter::bptA-/+ | 100 | 80 | 486 ± 582 | 90 | 70 | ND |

ND, Not determined; pos., positive.

No statistically significant differences between strains for bacterial loading within ticks.

n = 6-15.

n = 20-25.

Statistically different from PL133, BbDTR653, and BbDTR654 or just PL133 (PCR data) as calculated by χ2 goodness-of-fit test (P values listed in text).

Statistically different from PL133, BbDTR653, and BbDTR654 or PL133 as calculated by unpaired Student's t test (P values listed in text).

Fig. 2.

Spirochete loads of I. scapularis larvae infected with PL133 (•) or BbDTR596 (bptA mutant) (○). Repleted ticks were assessed for spirochetes by IFAs performed at weekly intervals. The percentage of decrease in spirochete loads for the bptA mutant were most marked within the first 2 weeks after repletion (P < 0.05, Mann–Whitney U test, denoted by asterisks).

At 2 months (Table 2) and up to 5 months (data not shown) after molting to the nymphal form (about 3 and 6 months after larval repletion), the number of flat (unfed) nymphal ticks infected with each Bb strain remained similar to that observed upon molting. Only 16% of ticks harboring the bptA mutant (BbDTR596) retained spirochetes (P < 0.02) (Table 2). Similar results were found for a bptA mutant cis-complemented with an irrelevant gene (bbe17) (BbDTR652) (Table 2), thereby establishing that the insertion of irrelevant DNA at this site downstream of pncA does not influence the phenotype of Bb; additional work supports this conclusion (A.T.R., J.S.B., K.E.H., and M.V.N., unpublished data). Taken together, we hypothesized that any bptA-deficient Bb that had survived the larval engorgement process would not survive a second repletion during the nymphal stage. Indeed, whereas >70% of the engorged nymphal ticks harboring either PL133 (wild-type), complemented strain BbDTR653 (bptA under its own promoter), or complemented strain BbDTR654 (bptA fused to the bbe17 promoter) were positive for spirochetes according to IFA (Table 2), not a single spirochete was detected within engorged nymphal ticks initially harboring the bptA mutants (P < 0.0016, P < 0.01, and P < 0.01, respectively). Moreover, PCR amplification of the borrelial gene, ospA, also was negative from all ticks initially harboring the bptA mutant, BbDTR596 (P < 4.7 × 10–7). In contrast, PCR analysis showed that 70% of fed nymphs contained PL133 (Table 2).

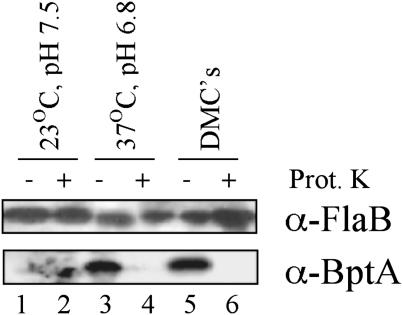

BptA is Protease-Accessible and Highly Conserved in Bb sensu lato Strains. From the deduced amino acid sequence (using SignalP and PSort), BptA appears to contain a putative cleavable amino-terminal leader sequence [signal peptidase II (lipoprotein-specific) consensus]. Proteinase K accessibility assays were used as an initial assessment of whether BptA might be surface-exposed on the outer membrane of wild-type Bb like other borrelial lipoproteins. Proteinase K treatment of Bb under conditions that did not digest periplasmic FlaB (control for outer membrane integrity) removed all BptA detectable by immunoblotting (Fig. 3, lanes 4 and 6). These findings held true regardless of whether the spirochetes were cultivated under conditions analogous to those present in feeding ticks (i.e., 37°C, pH 6.8) or within dialysis membrane chambers to mimic mammalian host adaptation (Fig. 3). Of note, BptA was not detected among spirochetes cultivated under conditions that mimic the flat (unfed) tick (i.e., 23°C, pH 7.5).

Fig. 3.

Protease accessibility of BptA in Bb grown under various culture conditions. Each lane was loaded with 5 × 107 bacteria that had been subjected to proteinase K (Prot. K) (+) or mock treatment (–). Detection (immunoblotting) of the endoflagellar (periplasmic) protein FlaB was used as an indicator of Bb outer membrane integrity and as a loading control. The smear in lane 2 is spurious background.

With the discovery of the essential nature of bptA for the survival of Bb within I. scapularis, we hypothesized that BptA may be conserved in Bb sensu lato isolates in general. By PCR analysis, bptA was identified in all seven sensu lato strains tested. Moreover, there was a high degree of conservation (>74% identity and >88% similarity) between strains at the amino acid level (Table 3). Further evaluation of the deduced amino acid sequence indicated that the putative signal peptidase II consensus motif (LXXC) at amino acid 13 in BptA was conserved in all sensu lato isolates tested (data not shown).

Table 3. Percent amino acid similarities and identities (in parentheses) of BptA homologs present among Bb sensu lato strains tested (with strain designations in bold).

|

B. burgdorferi

|

B. garinii

|

B. afzelii

|

B. valaisiana

|

B. bissettii

|

B. andersonii

|

B. japonica

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B31 | 297 | N40 | IP90 | PBi | BO23 | VS116 | DN127 | 21038 | IKA2 | |

| B31 | — | 99 (97) | 99 (97) | 96 (91) | 89 (76) | 98 (95) | 91 (80) | 97 (92) | 97 (91) | 98 (96) |

| 297 | — | 99 (95) | 97 (93) | 89 (75) | 98 (94) | 91 (78) | 97 (92) | 98 (90) | 98 (95) | |

| N40 | — | 96 (92) | 89 (76) | 100 (98) | 90 (77) | 98 (92) | 97 (88) | 100 (99) | ||

| IP90 | — | 89 (75) | 96 (91) | 89 (77) | 97 (95) | 97 (89) | 96 (91) | |||

| PBi | — | 89 (74) | 89 (77) | 89 (76) | 89 (78) | 89 (75) | ||||

| BO23 | — | 90 (80) | 98 (92) | 96 (88) | 100 (99) | |||||

| VS116 | — | 88 (78) | 90 (78) | 90 (79) | ||||||

| DN127 | — | 97 (89) | 98 (93) | |||||||

| 21038 | — | 96 (89) | ||||||||

| IKA2 | — | |||||||||

Discussion

Previous microarray analyses performed on Bb have revealed a large number of differentially regulated genes whose functional annotations remain largely unknown (15, 41, 42). Whereas many of these differentially regulated genes likely represent physiological “housekeeping” genes typically not thought of as virulence-associated, others have been noted in separate studies to encode virulence factors essential for Bb's infection of or survival within its arthropod or mammalian hosts (6, 7, 33, 43–45). Nevertheless, the testing of Koch's molecular postulates to ascertain whether a gene encodes a virulence trait (46) has been hindered greatly by a paucity of systems for genetically manipulating virulent Bb (13, 14). Despite the intractable nature of Bb to genetic manipulation, we applied recent advancements in borrelial insertional mutagenesis and genetic complementation to study two genes of interest (bba36 and bptA). ID50 analysis indicated that bba36-deficient mutants were virulent at wild-type levels (Table 1) and elicited histopathological sequelae typical of the murine model of Lyme borrelosis (Fig. 7). Moreover, tick studies indicated that spirochetes deficient in bba36 had no discernable defect on the presence of Bb within the larval or nymphal stages of I. scapularis infection (Table 2). Consequently, we have not yet ascribed a function to BBA36.

Because many lines of evidence now point to the importance of lp25 to virulence expression by Bb (8–10, 45, 47), we hypothesized that bptA might play a pivotal role in the infectious life cycle of the spirochete. We garnered experimental evidence to support this hypothesis by creating an insertional mutant of bptA and cis-complemented strains. The loss of bptA resulted in a one- to two-logarithm attenuation of Bb infectivity for mice (Table 1). Whereas it was possible that this reduction in virulence of the bptA mutant was due to spurious mutations or the spontaneous loss of a plasmid(s) (6, 7, 33, 48), virulence was restored to wild-type levels upon complementation of the bptA mutant with an intact bptA gene (Table 1), suggesting that the attenuation of infectivity was a direct result of the inactivation of bptA. Of note, when Purser et al. (45) complemented a lp25-deficient (i.e., lacking bptA), avirulent strain of Bb with a wild-type copy of pncA on a shuttle plasmid, virulence was restored, albeit not completely. In our case, the bptA mutant contained lp25 (i.e., it contained pncA), and hence the restoration of virulence to wild-type levels in the bptA-complemented strain likely was due to the contributions of both bptA and pncA. Also, as in the case of the lp25-deficient strain complemented with pncA (45), we found no differences in mouse histopathology elicited by the bptA mutant or the wild-type Bb (Fig. 7), suggesting that dissemination and tissue tropism (i.e., pathogenesis) were not impaired by the loss of bptA. The combined data presented herein suggest that although BptA likely is an accessory molecule for borrelial infectivity, it, too, along with PncA, is required for achieving natural levels of Bb infectivity. On the other hand, our data do not rule out the possibility that another as yet unidentified lp25-encoded gene(s) works in concert with BptA and PncA for maximal infectivity of Bb in its mammalian host.

Assessing borrelial gene function in both ticks and mice is paramount given the absolute dependence on and intimate association of Bb with its arthropod and mammalian hosts. Prior studies to assess borrelial gene function have led to circumstances in which desired mutants lost infectivity for mice (7, 44, 45), thereby revealing important aspects of virulence expression by Bb in the mammalian host. When such studies identify Bb genes that are unequivocally essential for mammalian infectivity/pathogenesis, it is more challenging and perhaps of lesser importance to investigate a role for the respective gene(s) in the arthropod phase of Bb's life cycle. In contrast, when loss of a gene leads to no discernable phenotype relative to mammalian infectivity/pathogenesis, or when loss of a gene results in attenuation, it should be considered that the gene in question may impact Bb's survival within its arthropod vector. Such logic prompted us to investigate the bptA mutant, which was only attenuated for infectivity in mice, for its ability to survive within various phases of tick morphogenesis.

When sterile tick larvae were allowed to feed on mice infected with the bptA mutant, there was a severe defect in the ability of the bptA mutant to maintain normal bacterial loads within ticks. In fact, there was a 92% decrease in spirochetal numbers in newly molted nymphs as compared with those found in larvae fed to repletion (Fig. 2). Most of this decline occurred within the first 2 weeks after larval repletion (Fig. 2), a time in which large amounts of blood meal remnants were observed within the midguts of the dissected ticks (data not shown). There also were significantly fewer newly molted nymphs that harbored any bptA mutant spirochetes (Table 2). Spirochete loads within these flat (unfed) nymphs did not change significantly during the subsequent (2 months after molting) resting period (Table 2). An interesting in vitro corollary to this observation may be found in the fact that BptA was not expressed by Bb under in vitro culture conditions analogous to those of flat ticks (Fig. 3), suggesting that BptA is not required when ticks are resting (i.e., not feeding). In contrast, the same in vitro experiments showed that BptA was expressed when Bb was cultivated under conditions that mimic tick feeding, implying that BptA functions to sustain the spirochete during tick feeding. Consistent with this notion, when mature nymphs were allowed to feed on naive mice (i.e., second feeding of tick life cycle), bptA mutant spirochetes were completely cleared. Taken together, bptA appears to be essential for the persistence of Bb throughout the tick phase(s) of its life cycle; thus, BptA can be considered a virulence factor strategic to the overall parasitic strategy of Bb (49).

Lyme borreliosis can be caused by three different sensu lato strains (Bb, Borrelia garinii, and Borrelia afzelii) in humans, whereas seven additional strains are thought to cause disease in animals (Borrelia andersonii, Borrelia bissettii, Borrelia valaisiana, Borrelia japonica, Borrelia turdae, Borrelia tunukii, and Borrelia lusitaniae) (50). PCR amplification by using oligonucleotide primers designed from Bb strain B31 sequence information (29, 30) revealed that BptA homologs were present in all borrelial strains tested. Moreover, there was a high degree of similarity (>88%) and identity (>74%) at the deduced amino acid level among all Bb sensu lato isolates (Table 3). Although the relapsing fever borreliae are closely related to Bb, they cause disease clinically distinct from that of Lyme borreliosis, suggesting that certain molecular determinants are specific to the different etiological agents. In this regard, bptA homologs were not detected by PCR among the two relapsing fever isolates tested (Borrelia hermsii and Borrelia turicatae) (data not shown), suggesting that bptA may be generally conserved for the survival of Lyme borreliosis strains in arthropod hosts. Furthermore, that the relapsing fever borreliae are transmitted by Ornithodoros rather than Ixodes ticks raises the provocative possibility that bptA subserves a specific function needed for Lyme borreliosis infection of a specific tick genus. Although sequence divergence between isolates could account for our inability to detect bptA homologs in relapsing fever borreliae, that bptA may be specific to Lyme borreliosis organisms is supported by microarray analysis of the B. hermsii genome; namely, no hybridization signal for any lp25-encoded gene, including bptA, was detected on Bb B31-based microarrays (51). Moreover, bptA was not detected in B. lonestari, the putative agent of Southern tick-associated rash illness (28) (data not shown), further supporting the contention that B. lonestari is more closely related to relapsing fever strains than to Lyme borreliosis agents (52). Taken together, these data imply that strong selective pressure(s) is operative for maintaining bptA among Lyme borreliosis strains in nature.

Earlier work called attention to another lp25-encoded gene product, PncA (BBE22), as essential for the survival of Bb in a mammalian host (45). However, PncA as a virulence factor may be unique to sensu stricto stains of Bb. For example, Glockner et al. (12) found that B. garinii does not appear to contain a homolog of pncA, although it does contain all other B31-specific lp25-encoded genes, including bptA. In fact, we detected pncA homologs by means of PCR in only four of the seven strains tested (Bb, B. valaisiana, B. andersonii, and B. bissettii; data not shown), even though all seven strains yielded a homolog of bptA. Although observations made to date (45, 47) may lead one to assume that selective pressure(s) to sustain pncA in Bb in nature is the driving force that maintains lp25 in wild-type strains, our data raise the provocative possibility that bptA may be what maintains virulence-associated lp25 in nature, at least in Bb and B. garinii, and possibly in other sensu lato strains.

GenBank searches did not identify proteins with homologies to BptA and thus did not yield theoretical predictions of BptA function. However, sequence analysis predicts that BptA is a membrane lipoprotein, and protease-accessibility experiments suggested that it is surface-exposed in Bb. Only two other outer membrane lipoproteins of Bb, OspA and OspC, thus far have been shown by genetic studies to play major roles in the tick phase of the Lyme disease spirochete. OspA is essential for tick midgut colonization by Bb (6), and OspC facilitates Bb invasion of tick salivary glands (7). Although the precise mechanism by which bptA serves to maintain Bb in ticks remains unclear, data presented herein support the contention that bptA should be included among those genes that impact tick-associated events crucial to Bb's persistence in nature.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Patrick Conley for technical assistance and Richard Marconi (Medical College of Virginia, Richmond) and Susan Little for providing borrelial strains and DNA, respectively. This work was supported by Public Health Service Grant AI-59062. J.S.B. was supported by National Institutes of Health Training Grant T32-AI07520.

Author contributions: A.T.R., J.S.B., and M.V.N. designed research; A.T.R., J.S.B., C.A., L.N., and K.E.H. performed research; A.T.R., K.M.K., and J.d.l.F. contributed new reagents/analytic tools; A.T.R., J.S.B., K.E.H., and M.V.N. analyzed data; and A.T.R. and M.V.N. wrote the paper.

Abbreviations: Bb, Borrelia burgdorferi; BSK, Barbour–Stoenner–Kelley; IFA, immunofluorescence analysis; lp, linear plasmid; Osp, outer surface lipoprotein.

Data deposition: The sequences reported in this paper have been deposited in the GenBank database (accession nos. AY894344–AY894351).

References

- 1.Steere, A. C. (1993) Hosp. Pract. 28, 37–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schwan, T., Piesman, J., Golde, W., Dolan, M. & Rosa, P. (1995) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92, 2909–2913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ohnishi, J., Piesman, J. & de Silva, A. M. (2001) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98, 670–675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schwan, T. G. & Piesman, J. (2000) J. Clin. Microbiol. 38, 382–388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.de Silva, A. M., Telford, S. R., III, Brunet, L. R., Barthold, S. W. & Fikrig, E. (1996) J. Exp. Med. 183, 271–275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yang, X. F., Pal, U., Alani, S. M., Fikrig, E. & Norgard, M. V. (2004) J. Exp. Med. 199, 641–648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pal, U., Yang, X., Chen, M., Bockenstedt, L. K., Anderson, J. F., Flavell, R. A., Norgard, M. V. & Fikrig, E. (2004) J. Clin. Invest. 113, 220–230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Purser, J. E. & Norris, S. J. (2000) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97, 13865–13870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Xu, Y., Kodner, C., Coleman, L. & Johnson, R. (1996) Infect. Immun. 64, 3870–3876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Labandeira-Rey, M. & Skare, J. T. (2001) Infect. Immun. 69, 446–455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kobryn, K. & Chaconas, G. (2002) Mol. Cell 9, 195–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Glockner, G., Lehmann, R., Romualdi, A., Pradella, S., Schulte-Spechtel, U., Schilhabel, M., Wilske, B., Suhnel, J. & Platzer, M. (2004) Nucleic Acids Res. 32, 6038–6046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tilly, K., Elias, A. F., Bono, J. L., Stewart, P. & Rosa, P. (2000) J. Mol. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2, 433–442. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cabello, F. C., Sartakova, M. & Dobrikova, E. (2001) Trends Microbiol. 9, 245–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Revel, A. T., Talaat, A. M. & Norgard, M. V. (2002) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99, 1562–1567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hughes, C. A., Kodner, C. B. & Johnson, R. C. (1992) J. Clin. Microbiol. 30, 698–703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eggers, C. H., Caimano, M. J., Clawson, M. L., Miller, W. G., Samuels, D. S. & Radolf, J. D. (2002) Mol. Microbiol. 43, 281–295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yang, X., Goldberg, M. S., Popova, T. G., Schoeler, G. B., Wikel, S. K., Hagman, K. E. & Norgard, M. V. (2000) Mol. Microbiol. 37, 1470–1479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Akins, D. R., Bourell, K. W., Caimano, M. J., Norgard, M. V. & Radolf, J. D. (1998) J. Clin. Invest. 101, 2240–2250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Barthold, S. W., Beck, D. S., Hansen, G. M., Terwilliger, G. A. & Moody, K. D. (1990) J. Infect. Dis. 162, 133–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kriuchechnikov, V. N., Korenberg, E. I., Shcherbakov, S. V., Kovalevskii Iu, V. & Levin, M. L. (1988) Zh. Mikrobiol. Epidemiol. Immunobiol. 12, 41–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wilske, B., Preac-Mursic, V., Gobel, U. B., Graf, B., Jauris, S., Soutschek, E., Schwab, E. & Zumstein, G. (1993) J. Clin. Microbiol. 31, 340–350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Postic, D., Assous, M. V., Grimont, P. A. & Baranton, G. (1994) Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 44, 743–752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Anderson, J. F., Magnarelli, L. A. & McAninch, J. B. (1988) J. Clin. Microbiol. 26, 2209–2212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kawabata, H., Masuzawa, T. & Yanagihara, Y. (1993) Microbiol. Immunol. 37, 843–848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thompson, R. S., Burgdorfer, W., Russell, R. & Francis, B. J. (1969) J. Am. Med. Assoc. 210, 1045–1050. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cadavid, D., Thomas, D. D., Crawley, R. & Barbour, A. G. (1994) J. Exp. Med. 179, 631–642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Varela, A. S., Luttrell, M. P., Howerth, E. W., Moore, V. A., Davidson, W. R., Stallknecht, D. E. & Little, S. E. (2004) J. Clin. Microbiol. 42, 1163–1169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Casjens, S., Palmer, N., van Vugt, R., Huang, W. M., Stevenson, B., Rosa, P., Lathigra, R., Sutton, G., Peterson, J., Dodson, R. J., et al. (2000) Mol. Microbiol. 35, 490–516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fraser, C. M., Casjens, S., Huang, W. M., Sutton, G. G., Clayton, R., Lathigra, R., White, O., Ketchum, K. A., Dodson, R., Hickey, E. K., et al. (1997) Nature 390, 580–586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Frank, K. L., Bundle, S. F., Kresge, M. E., Eggers, C. H. & Samuels, D. S. (2003) J. Bacteriol. 185, 6723–6727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Samuels, D. S. (1995) in Methods in Molecular Biology, ed. Nickoloff, J. A. (Humana, Totowa, NJ), 253–259.

- 33.Hubner, A., Yang, X., Nolen, D. M., Popova, T. G., Cabello, F. C. & Norgard, M. V. (2001) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98, 12724–12729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stewart, P. E., Thalken, R., Bono, J. L. & Rosa, P. (2001) Mol. Microbiol. 39, 714–721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sartakova, M. L., Dobrikova, E. Y., Terekhova, D. A., Devis, R., Bugrysheva, J. V., Morozova, O. V., Godfrey, H. P. & Cabello, F. C. (2003) Gene 303, 131–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hagman, K. E., Lahdenne, P., Popova, T. G., Porcella, S. F., Akins, D. R., Radolf, J. D. & Norgard, M. V. (1998) Infect. Immun. 66, 2674–2683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Barthold, S. W., de Souza, M. S., Janotka, J. L., Smith, A. L. & Persing, D. H. (1993) Am. J. Pathol. 143, 959–971. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Piesman, J. (1993) J. Med. Entomol. 30, 199–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Blevins, J. S., Revel, A. T., Caimano, M. J., Yang, X. F., Richardson, J. A., Hagman, K. E. & Norgard, M. V. (2004) Infect. Immun. 72, 4864–4867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Piesman, J., Schneider, B. S. & Zeidner, N. S. (2001) J. Clin. Microbiol. 39, 4145–4148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Brooks, C. S., Hefty, P. S., Jolliff, S. E. & Akins, D. R. (2003) Infect. Immun. 71, 3371–3383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ojaimi, C., Brooks, C., Casjens, S., Rosa, P., Elias, A., Barbour, A., Jasinskas, A., Benach, J., Katona, L., Radolf, J., et al. (2003) Infect. Immun. 71, 1689–1705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Caimano, M. J., Eggers, C. H., Hazlett, K. R. & Radolf, J. D. (2004) Infect. Immun. 72, 6433–6445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Grimm, D., Tilly, K., Byram, R., Stewart, P. E., Krum, J. G., Bueschel, D. M., Schwan, T. G., Policastro, P. F., Elias, A. F. & Rosa, P. A. (2004) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101, 3142–3147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Purser, J. E., Lawrenz, M. B., Caimano, M. J., Howell, J. K., Radolf, J. D. & Norris, S. J. (2003) Mol. Microbiol. 48, 753–764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Falkow, S. (1988) Rev. Infect. Dis. 10, Suppl. 2, S274–S276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Grimm, D., Eggers, C. H., Caimano, M. J., Tilly, K., Stewart, P. E., Elias, A. F., Radolf, J. D. & Rosa, P. A. (2004) Infect. Immun. 72, 5938–5946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yang, X. F., Alani, S. M. & Norgard, M. V. (2003) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100, 11001–11006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Casadevall, A. & Pirofski, L.-a. (2001) J. Infect. Dis. 184, 337–344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wang, G., van Dam, A. P., Schwartz, I. & Dankert, J. (1999) Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 12, 633–653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhong, J. & Barbour, A. G. (2004) Mol. Microbiol. 51, 729–748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bacon, R. M., Pilgard, M. A., Johnson, B. J., Raffel, S. J. & Schwan, T. G. (2004) J. Clin. Microbiol. 42, 2326–2328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.