Abstract

Chromothripsis describes the catastrophic fragmentation of individual chromosomes followed by its haphazard reassembly into a derivative chromosome harboring complex rearrangements. This process can be initiated by mitotic cell division errors when one or more chromosomes aberrantly mis-segregate into micronuclei and acquire extensive DNA damage. Approaches to induce the formation of micronuclei encapsulating random chromosomes have been used; however, the eventual reincorporation of the micronucleated chromosome into daughter cell nuclei poses a challenge in tracking the chromosome for multiple cell cycles. Here we outline an approach to genetically engineer stable human cell lines capable of efficient chromosome-specific micronuclei induction. This strategy, which targets the CENP-B-deficient Y chromosome centromere for inactivation, allows the stepwise process of chromothripsis to be experimentally recapitulated, including the mechanisms and timing of chromosome fragmentation. Lastly, we describe the integration of a selection marker onto the micronucleated Y chromosome that enables the diverse genomic rearrangement landscape arising from micronuclei formation to be interrogated.

1. Introduction

Chromothripsis can generate complex structural variants in which tens to hundreds of rearrangements are localized to one or a few chromosome(s) (Stephens et al., 2011). Recent cancer genome sequencing has detected the signatures of chromothripsis across a broad range of tumor types (Cortes-Ciriano et al., 2020; Voronina et al., 2020), indicating that chromothripsis is a common genomic feature of cancers. An initiating step in driving chromothripsis is the mis-segregation of an entire chromosome or chromosome arm into abnormal structures called micronuclei, which resemble small nuclei harboring a fragile yet distinct nuclear envelope (Hatch et al., 2013; Liu et al., 2018). Chromosomes in micronuclei are prone to acquiring DNA damage throughout interphase, which subsequently triggers its catastrophic fragmentation during mitosis (Crasta et al., 2012; Ly et al., 2017). In the next cell cycle, the chromosome fragments are incorrectly repaired in random order, thereby producing a spectrum of genomic rearrangements (Zhang et al., 2015; Ly et al., 2019). Given the prevalence of chromothripsis in cancer, a complete understanding of micronuclei biology and the fate of micronucleated chromosomes will provide insight into the origins of chromothripsis and how mitotic errors fuel rapid cancer genome evolution (Zhang et al., 2013).

Micronuclei are relatively rare in chromosomally stable cell lines. To overcome this, several approaches have been used to experimentally increase the frequency of micronucleation in mammalian cells (Ly and Cleveland, 2017). One strategy is to induce whole-chromosome mis-segregation using chemical mitotic inhibitors, such as nocodazole or colcemid, to cause cell cycle arrest in mitosis by interfering with spindle microtubule dynamics. Following drug washout and microtubule polymerization, the formation of improper kinetochore-microtubule attachments will increase the rate of chromosome mis-segregation. Alternatively, key components of mitosis, such as the motor kinesin CENP-E (Yen et al., 1992) or Mps1 kinase (Weiss and Winey, 1996), can be chemically inhibited (Santaguida et al., 2010; Wood et al., 2010). Combined CENP-E and Mps1 perturbation using low-dose inhibitors have been used to efficiently induce chromosome mis-segregation by causing chromosome alignment failure followed by premature bypass of the spindle assembly checkpoint (Santaguida et al., 2017; Soto et al., 2017). Since these approaches largely affect chromosomes at random, it is challenging to monitor the fate of the micronucleated chromosome for more than one cell cycle following its reincorporation into the nucleus. More recently, CRISPR/Cas9-induced DNA breaks have been used to generate micronuclei harboring a targeted chromosome arm (Leibowitz et al., 2021); however, only ~4-8% of cells exhibit micronucleation since most breaks are likely repaired prior to mitosis.

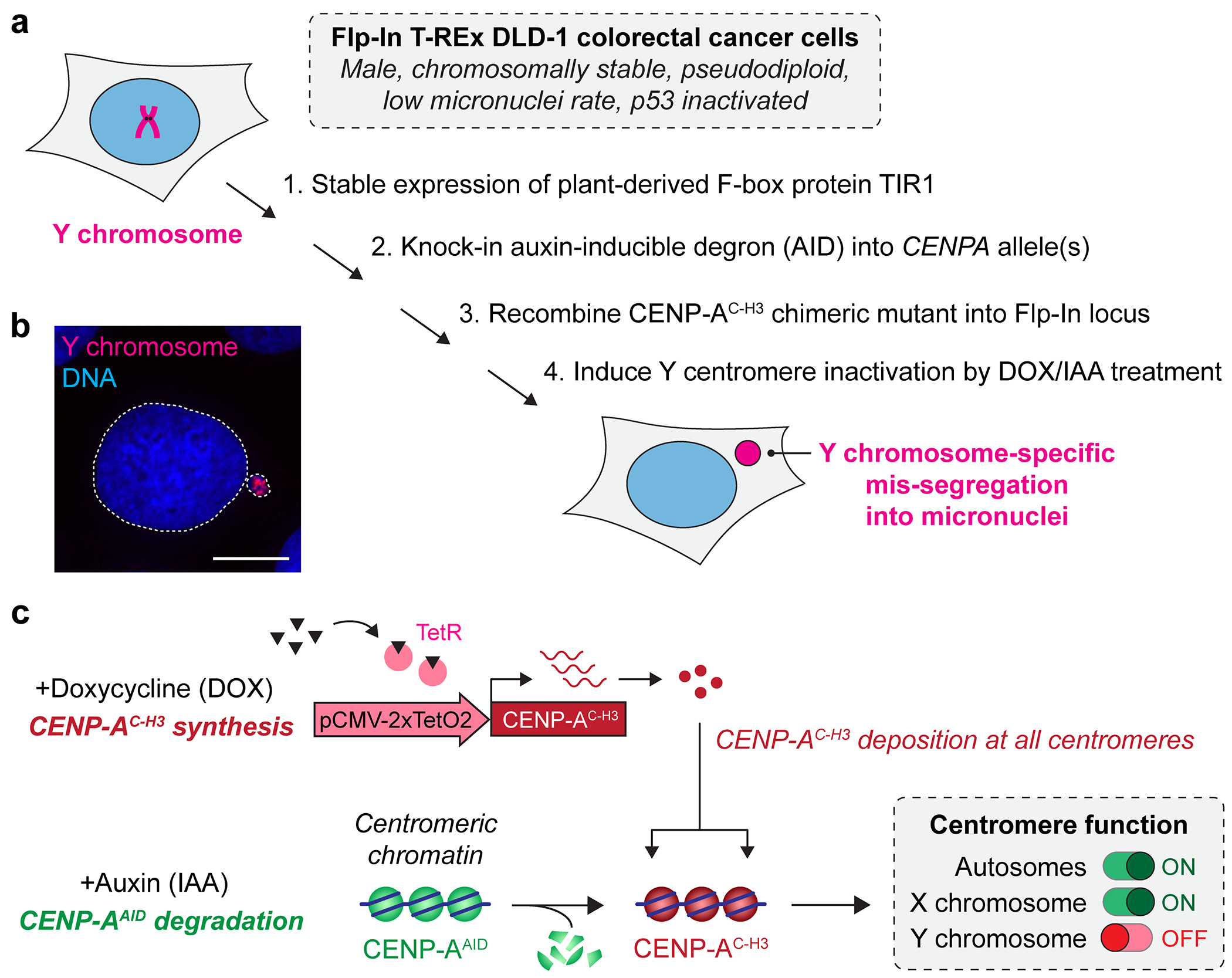

We recently developed a chromosome-specific mis-segregation strategy that enabled the fate of micronucleated chromosomes to be monitored long-term spanning multiple cell cycles (Ly et al., 2017; Ly et al., 2019). This was achieved by selectively inactivating the centromere of the human Y chromosome through transient replacement of the centromere-specific histone H3 variant CENP-A with a mutant that does not support kinetochore assembly on the Y chromosome. This mutant, termed CENP-AC-H3, swaps the carboxy-terminal tail of CENP-A with the corresponding region of histone H3. For each of the human centromeres except for the Y, kinetochores are assembled through redundant mechanisms involving CENP-A and CENP-B (Fachinetti et al., 2013; Fachinetti et al., 2015), the latter of which is recruited to centromeres through a 17-bp motif sequence called CENP-B boxes (Masumoto et al., 1989; Muro et al., 1992). Unlike the autosomes and X chromosome, the Y centromere is incapable of recruiting CENP-B due to the lack of CENP-B boxes (Earnshaw et al., 1987), rendering kinetochore function completely dependent on the CENP-A pathway (Fachinetti et al., 2015; Hoffmann et al., 2016). The CENP-AC-H3 mutant abolishes its ability to recruit CENP-C (Guse et al., 2011; Fachinetti et al., 2013) and re-wires all centromere function towards the CENP-B-dependent pathway. As a result, CENP-AC-H3 causes mis-segregation of the Y chromosome into micronuclei as it is unable to establish a functional kinetochore (Fachinetti et al., 2015; Hoffmann et al., 2016; Ly et al., 2017).

This strategy has previously been used to experimentally reconstruct several key processes driving chromothripsis, including nuclear envelope rupture, DNA damage, and mitotic chromosome fragmentation (Ly et al., 2017), the latter of which can be visualized by DNA fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) on metaphase spreads. By integrating an antibiotic resistance marker into the Y, we subsequently demonstrated that micronucleated chromosomes can acquire diverse genomic rearrangements, including translocations, chromothripsis, and the production of extrachromosomal DNAs (Ly et al., 2019). This approach, termed CEN-SELECT, is a powerful and tractable model system for interrogating the genomic rearrangement landscape of micronuclei with a human chromosome under minimal selective pressure in somatic cells. Here we describe the step-by-step derivation of the CEN-SELECT system in human cells and its applications in studying the mechanisms underlying chromothripsis. In principle, this strategy can be applied to any male mammalian cell line with the Y chromosome and that is amenable to genetic engineering. Additionally, this approach can also be adapted to any autosome harboring a neocentromere, which, like the Y chromosome centromere, are deficient in CENP-B boxes and reliant on the CENP-A C-terminal tail.

2. Y centromere inactivation using a CENP-A gene replacement strategy

The auxin-inducible degron (AID) system enables the rapid and conditional depletion of diverse protein substrates in mammalian cells (Nishimura et al., 2009; Holland et al., 2012). This system exploits the plant-derived F-box protein TIR1 (Ruegger et al., 1998; Gray et al., 1999), which induces proteasome-mediated degradation of protein targets in the presence of auxin (indole-3-acetic acid, IAA) by the SCF E3 ubiquitin ligase complex (Dharmasiri et al., 2005; Kepinski and Leyser, 2005; Tan et al., 2007). We leveraged this system by fusing the AID to the N-terminus of CENP-A (CENP-AAID) in human DLD-1 cells expressing TIR1. Although we previously used TAL effector nucleases to introduce the AID tag, CRISPR/Cas9 approaches can be adapted for more efficient gene editing. In the presence of IAA, CENP-AAID undergoes complete (or nearly complete) degradation within one hour to an undetectable level (Hoffmann et al., 2016). Because CENP-A is essential for chromosome segregation and viability (Howman et al., 2000; Fachinetti et al., 2013), we complemented CENP-AAID loss by introducing a doxycycline (DOX)-inducible CENP-AC-H3 rescue in which the final six amino acids of CENP-A (amino acids LEEGLG) are substituted with the corresponding C-terminal region of histone H3 (amino acids ERA) (Figure 1). Because IAA-induced degradation of CENP-A occurs more rapidly than DOX-induced transcriptional synthesis and centromeric loading of CENP-AC-H3, it is important to note that CENP-AC-H3 is expressed at low levels in the absence of DOX, thereby epigenetically preserving centromere position upon CENP-AAID removal (Ly et al., 2017).

Figure 1. Genetic engineering of human cells to induce centromere inactivation and chromosome-specific mis-segregation into micronuclei.

a) Step-by-step derivation of stable DLD-1 cells to induce Y centromere inactivation using a CENP-A replacement strategy. b) Example of a micronucleus harboring the Y chromosome as detected by DNA fluorescence in situ hybridization. Scale bar, 10 μm. c) Schematic representation of the CENP-A replacement strategy leveraging auxin-inducible degradation of endogenous CENP-A coupled to doxycycline-inducible synthesis of a chimeric CENP-A with a mutated carboxy-terminal tail (CENP-AC-H3) that does not support Y centromere function.

2.1. Expression of TIR1 by retroviral transduction

Materials

T-REx Flp-In DLD-1 cells

293GP retrovirus packaging cell line

DMEM, high glucose (Gibco, 11965118)

Fetal bovine serum, tetracyclin-free (Omega Scientific, FB-16)

100 U/mL penicillin-streptomycin (Sigma-Aldrich, P4333)

0.05% Trypsin-EDTA (Gibco, 25300120)

Phosphate buffered saline, pH 7.4 (Gibco, 10010049)

ZymoPURE II Plasmid Midiprep Kit (Zymo Research, D4200) or equivalent

pBABE-osTIR1-9myc plasmid (Addgene, 64945)

pVSV-G helper plasmid (Addgene, 8454)

X-tremeGENE 9 DNA transfection reagent (Roche, XTG9-RO)

Opti-MEM I reduced serum medium (Gibco, 31985070)

0.45 μm syringe filter

Polybrene (Sigma-Aldrich, TR-1003-G)

Puromycin (Sigma-Aldrich, P8833)

Anti-Myc tag antibody (Sigma-Aldrich, OP10L-200UG)

Materials and reagents for immunoblotting

T-REx Flp-In DLD-1 cells can be generated according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Invitrogen, K6500-01). DLD-1 and 293GP cells are cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 100 U/mL penicillin-streptomycin (hereafter referred to as growth medium).

Purify a retroviral pBABE plasmid containing the Oryza sativa TIR1 gene and puromycin-resistance gene (Addgene, 64945) (Holland et al., 2012) using a standard midi-prep kit.

Seed 2 x 106 293GP cells per 10 cm2 dish in 10 mL growth medium.

The next day, combine 4 μg of pBABE-osTIR1-9myc and 2 μg of pVSV-G plasmids into a 1.5 mL tube. In a separate tube, dilute 15 μL of X-tremeGENE 9 into 500 μL of Opti-MEM. Transfer the mixture into the tube containing the plasmids and incubate at room temperature for 15 minutes. Add the transfection mixture dropwise to 293GP cells.

The next day, remove the transfection medium from the 293GP cells and replace with ~8 mL growth medium. Seed 1-2 x 105 T-REx Flp-In DLD-1 cells per well in a 6-well plate (4 wells total).

After 1 or 2 days (48- or 72-hours post-transfection, respectively), collect the retrovirus-containing supernatant medium from transfected 293GP cells and filter through a 0.45 μm syringe filter. Infect each set of DLD-1 cells with 0, 100, 500, or 1,000 μL of viral supernatant supplemented with 8 μg/mL polybrene to a final volume of 2 mL per well.

~24 hours after infection, remove the virus-containing media from DLD-1 cells, and if needed, transfer the cells from a 6-well plate into a 10 or 15 cm2 plate. Add 2 μg/mL puromycin the next day to select for TIR1-expressing cells. Depending on the efficiency of viral transduction, DLD-1 cells may need to be re-plated at a lower density in 10 or 15 cm2 dish or in a one cell per well format in 96-well plates. Puromycin selection is complete once all non-infected DLD-1 cells have died.

After allowing single cell-derived, puromycin-resistant clones to grow for 2-3 weeks, expand several clones and verify the expression levels of Myc-tagged TIR1 by immunoblotting with an anti-Myc antibody. Identify one or a few clones with high TIR1 expression to proceed to the next step.

Note: Viral supernatant can be aliquoted, snap frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80C.

Note: High expression of TIR1 is critical for rapid and complete degradation of CENP-AAID. If needed, established cell lines (Holland et al., 2012) can be used as a reference for appropriate TIR1 levels.

Note: After each step of genetic manipulation, it is critical to confirm that your targeted clone-of-interest exhibits normal growth rate and morphology while maintaining a single copy of the Y chromosome (as determined by metaphase FISH [steps 4.2 and 4.3]) before moving onto the next step.

2.2. Fusing an auxin-inducible degron tag to CENP-A

This step describes CRISPR-mediated knock-in of an AID tag fused to enhanced yellow fluorescent protein (EYFP) into the N-terminus of the endogenous CENPA alleles by co-transfection with Cas9, a single guide RNA (sgRNA) plasmid, and an EYFP-AID donor construct flanked by homology arms. Additional information for designing AID-tagging constructs by homology-directed repair can be found elsewhere (Hoffmann and Fachinetti, 2018; Yesbolatova et al., 2019; Adhikari et al., 2021).

Materials

T-REx Flp-In TIR1 DLD-1 cells (generated in 2.1)

ZymoPURE II Plasmid Midiprep Kit (Zymo Research, D4200) or equivalent

pUC57-LHA-EYFP-AID-RHA donor vector (GenScript or equivalent)

pX330-U6-Chimeric_BB-CBh-hSpCas9 plasmid (Addgene 42230)

Materials and reagents for cloning

Nucleofector kit L (Lonza VCA-1005)

Nucleofector II device (Lonza AAD-1001)

Electroporation cuvettes

Indole-3-acetic acid, stock 500mM in water (Sigma-Aldrich, I5148)

Fluorescence activated cell sorting (FACS) device

Materials and reagents for PCR and agarose gel

Oligonucleotides flanking AID-EYFP at the N-terminus of CENP-A:

5’- GACTTCTGCCAAGCACCG -3’ (forward)

5’- GCCTCGGTTTTCTCCTCTTC -3’ (reverse)

5’-CTCATGAAAGGATCGGATGC-3’ (reverse, binds within AID sequence)

Materials and reagents for immunoblotting

Anti-GFP antibody (Cell Signaling, 2555, 1:1,000)

Anti-CENP-A antibody (Cell Signaling, 2186, 1:1,000)

Synthesize a donor vector containing EYFP-AID flanked by 450 bp homology arms targeting each side of the CENPA start codon.

Search for potential guide RNA sequences near the CENPA start codon using a CRISPR design algorithm (e.g., CRISPick).

Construct the Cas9/sgRNA plasmid according to the protocol described at https://www.addgene.org/crispr/zhang/. Clone the oligonucleotide encoding the guide RNA targeting the 5′ untranslated region of CENPA into the BbsI restriction site of the pX330-U6-Chimeric_BB-CBh-hSpCas9 plasmid.

Co-transfect 1 x 106 T-REx Flp-In TIR1 DLD-1 cells with a 9:1 ratio of EYFP-AID donor construct to Cas9/sgRNA plasmid using a total of 2 μg of high-quality DNA by electroporation using the Nucleofector II device (according to manufacturer’s instructions). To check transfection efficiency, perform a separate transfection with 500 ng of a plasmid encoding soluble GFP.

After electroporation, immediately transfer cells from the cuvette into a 10 cm2 dish in growth medium and allow for cells to recover. Change medium as needed to remove dead cells and/or debris.

Ensure electroporated cells are healthy. 3-4 days after transfection, isolate single EYFP+ cells into individual wells of 96-well plates by fluorescence-activated cell sorting.

Screen for potential AID-tagged CENP-A clones by immunoblotting with anti-CENP-A and/or anti-GFP antibodies, PCR for targeted insertion of EYFP-AID into the translation start codon of CENPA, and/or by Sanger sequencing. The expected molecular weight of EYFP-AID-tagged CENP-A is ~62 kDa compared to wild-type CENP-A at ~17 kDa.

Confirm rapid and efficient IAA-induced degradation of CENP-AEYFP-AID by performing a time-course experiment to monitor CENP-A levels by immunoblotting or microscopy.

Note: Transfection reagents such as X-tremeGENE 9 (Roche) or FuGENE HD (Promega) can be used as an alternative to electroporation for CRISPR editing, as described in step 5.1.

Note: Since AID tagging is targeted to the N-terminus of CENP-A, it is possible to achieve biallelic knock-in of EYFP-AID at both CENPA alleles (CENP-AEYFP-AID/EYFP-AID) or mono-allelic insertion knock-in with an insertion/deletion mutation to disrupt the second allele (CENP-A EYFP-AID/−). Although either genotype is suitable, it is important to properly characterize individual clones by both immunoblotting and Sanger sequencing.

Note: Since CENP-A is essential for cell viability, an alternative method for screening is to score for cell lethality in the presence of IAA. To this end, plate individual clones at a low confluency (~1-5%) in duplicate wells of a multi-well plate (e.g., two wells of a 24- or 96-well plate). For each clone, add IAA to one set and wait 10-14 days for the untreated wells to reach confluency. Examine IAA-treated set for those that exhibit cell lethality, which represents the edited clones of interest. Expand the corresponding clone from the untreated plate for confirmation using the methods described above.

Note: The EYFP tag can be used to detect endogenous CENP-A by immunoblotting or immunofluorescence using an anti-GFP antibody, as well as visualization in live cells by microscopy.

2.3. Expression of a CENP-A C-terminal mutant rescue

In the next step, a DOX-inducible rescue construct expressing CENP-AC-H3 is integrated into a Flp Recombination Target (FRT) site using the Flp recombinase.

Materials

T-REx Flp-In TIR1 + CENP-AEYFP-AID DLD-1 clone (generated in 2.2)

ZymoPURE II Plasmid Midiprep Kit (Zymo Research, D4200) or equivalent

pcDNA5/FRT/TO plasmid (Invitrogen, V652020)

pOG44 plasmid (Invitrogen, V600520)

X-tremeGENE 9 DNA transfection reagent (Roche, XTG9-RO)

Opti-MEM I reduced serum medium (Gibco, 31985070)

Hygromycin B (Sigma-Aldrich, H3274)

Doxycycline hydrochloride (Sigma-Aldrich, D3447)

Materials and reagents for immunoblotting

Anti-CENP-A antibody (Cell Signaling, 2186)

Clone CENP-AC-H3 cDNA into pcDNA5/FRT/TO plasmid and obtain transfection-grade plasmid DNA.

Seed 2 x 105 T-Rex Flp-In TIR1 + CENP-AEYFP-AID cells per well into three wells of a 6-well plate.

The next day, aliquot 2-3 ug of plasmid DNA containing three different ratios of pcDNA5/FRT/TO-CENP-AC-H3 to pOG44 (e.g., 2:3 to 1:9) into 1.5 mL tubes.

In a separate 1.5 mL tube, dilute 6 μL of X-tremeGENE 9 into 200 μL of Opti-MEM per condition. For example, create a master mix by diluting 18.75 uL of X-tremeGENE 9 into 625 uL of Opti-MEM. Transfer 200 uL of the transfection master mix into the tubes containing the plasmids and incubate at room temperature for 15 minutes. Add the transfection/plasmid mixture dropwise onto T-Rex Flp-In TIR1 + CENP-AEYFP-AID cells in the 6-well plate.

24-48 hours after transfection, pool the 3 wells together into a 15 cm dish in growth medium containing 200 μg/mL hygromycin B. Allow for single clones to grow for ~2 weeks while refreshing selection medium as needed. Isolate and expand hygromycin-resistant clones for characterization.

Treat single cell-derived, hygromycin-resistant clones with 1 μg/mL doxycycline (DOX) for 1 day to screen for DOX-inducible CENP-AC-H3-expressing clones by immunoblotting with an anti-CENP-A antibody. The expected molecular weight of CENP-AC-H3 is ~17 kDa.

Note: Since the FRT site is integrated into the same genomic locus within all clones, it may also be appropriate to pool together hygromycin-resistant clones to generate a polyclonal population.

Note: This process may be inefficient due to low transfection and/or recombination efficiency.

3. Induction of Y chromosome-specific micronuclei

As described previously, the addition of DOX/IAA leads to rapid degradation of endogenous CENP-A and its replacement with CENP-AC–H3, which will cause selective inactivation of the Y centromere and subsequent Y chromosome mis-segregation into micronuclei (Figure 1). In our experience, ~25% of cells harbor micronuclei within 48 hours of DOX/IAA treatment, and among these, ~85% of micronuclei contain the Y chromosome (Ly et al., 2017; Ly et al., 2019). Additionally, given the haploid and non-essential nature of the Y chromosome, centromere inactivation will also result in the onset of Y chromosome aneuploidy, including the gain and loss of whole Y chromosomes.

Materials

T-REx Flp-In TIR1 + CENP-AEYFP-AID + CENP-AC-H3 DLD-1 cells (generated in 2.3)

Cell culture growth medium

PBS, pH 7.4 (Gibco, 10010049)

0.05% Trypsin-EDTA (Gibco, 25300120)

Doxycycline hydrochloride (Sigma-Aldrich, D3447)

Indole-3-acetic acid (Sigma-Aldrich, I5148)

Glass coverslips (Fisher Scientific, 12-545-81P)

Glass chamber slides (Milipore, PEZGS0816)

Carnoy’s fixative, (3:1 methanol:acetic acid), prepared fresh

Y chromosome FISH paint probe (MetaSystems, D-0324-100)

Fixogum Rubber Cement (MP Biomedicals, MP1FIXO0125)

Coplin jars

0.4x SSC

2x SSC + 0.05% Tween-20

DAPI (Sigma-Aldrich, MBD0015)

ProLong Gold Antifade Mountant (Invitrogen, P36934)

3.1. Cell culture and interphase FISH

On day −1, seed T-Rex Flp-In TIR1 + CENP-AEYFP-AID + CENP-AC-H3 DLD-1 cells onto glass coverslips in a multi-well dish (for DAPI staining) or glass chamber slides (for interphase FISH).

On day 0, dilute DOX/IAA in growth medium to a final concentration of 1 μg/mL and 500 μM, respectively. Remove medium and replace with DOX/IAA-containing medium. As a negative control, replace medium on a separate set of cells with growth medium without DOX/IAA.

On day 2, micronuclei can be visualized by routine DAPI staining or interphase FISH, as described below.

3.2. Interphase FISH

Wash cells with PBS and fix with freshly made Carnoy’s fixative for 15 minutes at room temperature in a Coplin jar.

Rinse slides with 80% ethanol and let air dry for 5 minutes.

Apply 2-3 μL of the FISH probe mixture per sample and cover with coverslip.

Co-denature samples and probes by heating slides on a hot plate at 75°C for 2 minutes.

Seal coverslip with rubber cement and incubate slides at 37°C overnight in a humidified chamber.

The next day, heat 0.4x SCC in a Coplin jar to 72C in a water bath. Carefully remove rubber cement and coverslip from samples using a forcep.

Submerge slides in pre-warmed 0.4x SSC solution for 2 mins.

Transfer slides to 2x SSC/0.05% Tween-20 in a separate Coplin jar and submerge for 30 seconds at room temperature. Rinse slides by submerging in PBS.

Stain slides with DAPI for 10 minutes. Rinse with ddH2O and air dry for ~5 mins.

Add 5 μL antifade solution per sample and seal with a coverslip.

Store slides at 4°C in dark until imaging on a fluorescent microscope.

Note: After fixation, slides can be stored in Carnoy’s fixative at −20°C if needed.

Note: For optimal hybridization of FISH probes, it is important to use chamber slides without glue or to remove all glue residue from the slide prior to FISH.

Note: This protocol has been optimized for use with MetaSystems FISH probes. If using other commercial probes, please see manufacturer’s recommended protocol.

Note: An inexpensive humidified dark chamber can be created using a 15 cm2 tissue culture dish wrapped in foil. To create humidity, place a wet folded paper towel inside the chamber.

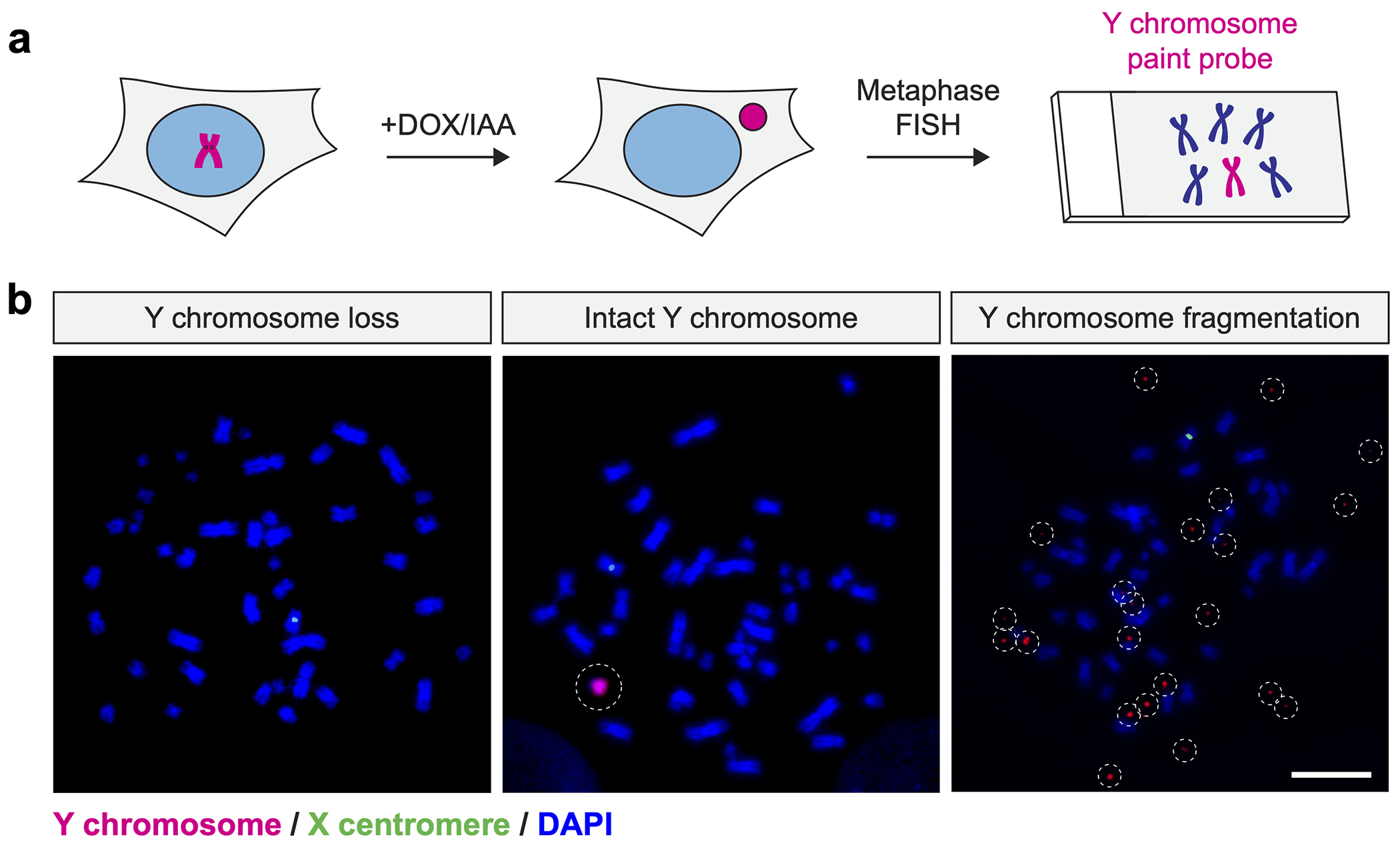

4. Y chromosome fragmentation following micronucleus induction

Micronuclear chromosomes acquire extensive DNA damage following nuclear envelope rupture and/or abnormal DNA synthesis (Crasta et al., 2012; Hatch et al., 2013), which triggers chromosome fragmentation upon progression into mitosis. Using the approach described here, Y chromosome fragmentation can be visualized by DNA FISH on metaphase chromosome spreads (Ly et al., 2017). This occurs at a frequency of ~20% within the fraction of Y chromosome-positive metaphases and typically at low (<1%) frequency under control conditions without the induction of Y chromosome micronuclei.

Materials

T-REx Flp-In TIR1 + CENP-AEYFP-AID + CENP-AC-H3 DLD-1 cells

Cell culture growth medium

PBS, pH 7.4 (Gibco, 10010049)

0.05% Trypsin-EDTA (Gibco, 25300120)

Doxycycline hydrochloride (Sigma-Aldrich, D3447)

Indole-3-acetic acid (Sigma-Aldrich, I5148)

Colcemid (KaryoMAX, Thermo Fisher, 15212012)

75 mM KCl

Ice-cold Carnoy’s fixative, (3:1 methanol:acetic acid), prepared fresh

DAPI (Sigma-Aldrich, MBD0015)

Fisherbrand Superfrost Cytogenetics Slides (Fisher Scientific, 22-035-900)

ProLong Gold Anti-Fade Mountant (Thermo Fisher, P36930)

4.1. Cell culture

On day −1, seed T-Rex Flp-In TIR1 + CENP-AEYFP-AID + CENP-AC-H3 DLD-1 cells into 10 cm2 dishes.

On day 0, dilute DOX/IAA in growth medium to a final concentration of 1 μg/mL and 500 μM, respectively. Remove medium and replace with DOX/IAA-containing. As a negative control, replace medium on a separate set of cells with growth medium without DOX/IAA.

On day 3, remove DOX/IAA-containing medium and add fresh growth medium containing 100 ng/mL colcemid to arrest cells in mitosis. Return cells to incubator for ~4 hours to enrich for mitotic cells.

4.2. Metaphase spread preparation

Gently wash cells with PBS, add 1 mL trypsin, and return to the incubator. Once cells are detached, add 9 mL growth medium and collect cells into a 15 mL tube.

Pellet cells by centrifugation and gently remove supernatant, taking care to leave a small amount of medium in the tube.

Resuspend pellet in remaining medium by gently flicking the tube several times.

Add 5 mL of pre-warmed 75 mM KCl dropwise while slowly vortexing the tube. Incubate in a 37°C water bath for 6 minutes, which will allow the cells to swell under hypotonic conditions.

Add 1 mL of ice-cold Carnoy’s fixative to the tube. Mix Carnoy and KCl by gently inverting the tube 2-3 times. Centrifuge cells at 180 RCF for 5 minutes and discard the supernatant.

Dislodge pellet by gently flicking the tube. Add 5 mL of ice-cold Carnoy and gently invert 2-3 times to mix. Centrifuge cells and discard supernatant.

Resuspend cells with 500 μL cold Carnoy fixative and keep on ice. Fixed cells can be stored in suspension at −20°C.

Drop 10 μL of the cell suspension onto a slide from a height of 3-6 inches, allow to briefly dry, and examine spreads on a light microscope.

Use slides for the following FISH experiments or store at 4°C if needed.

Note: Mitosis-synchronized cultures should be handled carefully as mitotic cells can easily detach from the plate.

Note: It is critical to slowly add KCl dropwise and to not pipette cells resuspended in KCl.

Note: Key parameters of optimal metaphase spreads include a density without overlapping metaphases, an even spreading of chromosomes, adequate number of mitotic cells, and the lack of individual chromosomes that appear scattered throughout the slide due to cell bursting,

Note: To achieve optimal density of cells on slides, adjust volume accordingly by adding Carnoy’s fixative or by centrifugation and resuspending the pellet in a lower volume of Carnoy’s fixative.

Note: To easily identify the sample area of metaphases on slides, use a marker to mark the edges of the metaphase spread on the underside of the sample. This area is easily visible when holding the slide up towards a light source. This will enable you to easily visualize the area to examine under the light microscope and subsequently place the FISH probes and coverslip.

Note: Preparation of metaphase spreads can be performed in 6-well plates by scaling down reagents and using 1.5 mL tubes instead of 15 mL tubes.

4.3. Metaphase FISH

Metaphase spreads can be inspected for chromosome fragmentation by DNA FISH using a Y chromosome paint probe. This protocol is similar to the one described previously for interphase FISH (step 3.2).

Apply 2-3 μL of the FISH probe mixture per sample and cover with coverslip.

Heat slides on a hot plate (75°C) for 2 minutes to denature samples and probe.

Seal coverslip with rubber cement and incubate slides at 37°C overnight in a humidified chamber.

The next day, heat 0.4x SCC in a Coplin jar to 72C in a water bath. Carefully remove rubber cement and coverslip from samples using a forcep.

Submerge slides in pre-warmed 0.4x SSC solution for 2 mins.

Transfer slides to 2x SSC/0.05% Tween-20 in a separate Coplin jar and submerge for 30 seconds at room temperature. Rinse slides by submerging in PBS.

Stain slides with DAPI for 10 minutes. Rinse with ddH2O and air dry for ~5 mins.

Add 5 μL antifade solution per sample and mount with coverslip.

Store slides at 4°C in dark until imaging on a fluorescent microscope.

4.4. Quantification of mitotic chromosome fragmentation

In untreated control samples, most cells will carry a single, intact copy of the Y chromosome. In contrast, DOX/IAA-treated cells will harbor a normal Y chromosome, exhibit complete Y chromosome loss, or appear highly fragmented (Figure 2). We previously defined fragmentation as meeting the following criteria: 1) the Y chromosome FISH signal must overlap with DAPI signals, 2) each fragmentation event must contain a minimum of three independent FISH signals, indicative of three fragments, and 3) if combined with a Y centromere probe, at least one fragment must harbor the centromere. From prior experience, we have observed up to 53 fragments per metaphase spread (Ly et al., 2017).

Figure 2. Cytogenetic detection of fragmented Y chromosomes following micronucleus induction.

a) Schematic of micronucleus induction followed by the analysis of fragmented chromosomes by metaphase FISH. b) Examples of metaphase spreads hybridized to Y chromosome-specific paint probes. Induction of centromere inactivation by 3d DOX/IAA treatment causes efficient Y chromosome loss or fragmentation. Scale bar, 10 μm.

Note: The inclusion of a Y centromere probe along with the Y chromosome paint probe is recommended; however, probes (e.g., autosome paints, X centromere) can be used as an internal control for FISH and as a negative control.

5. Y chromosome rearrangements following micronucleus induction

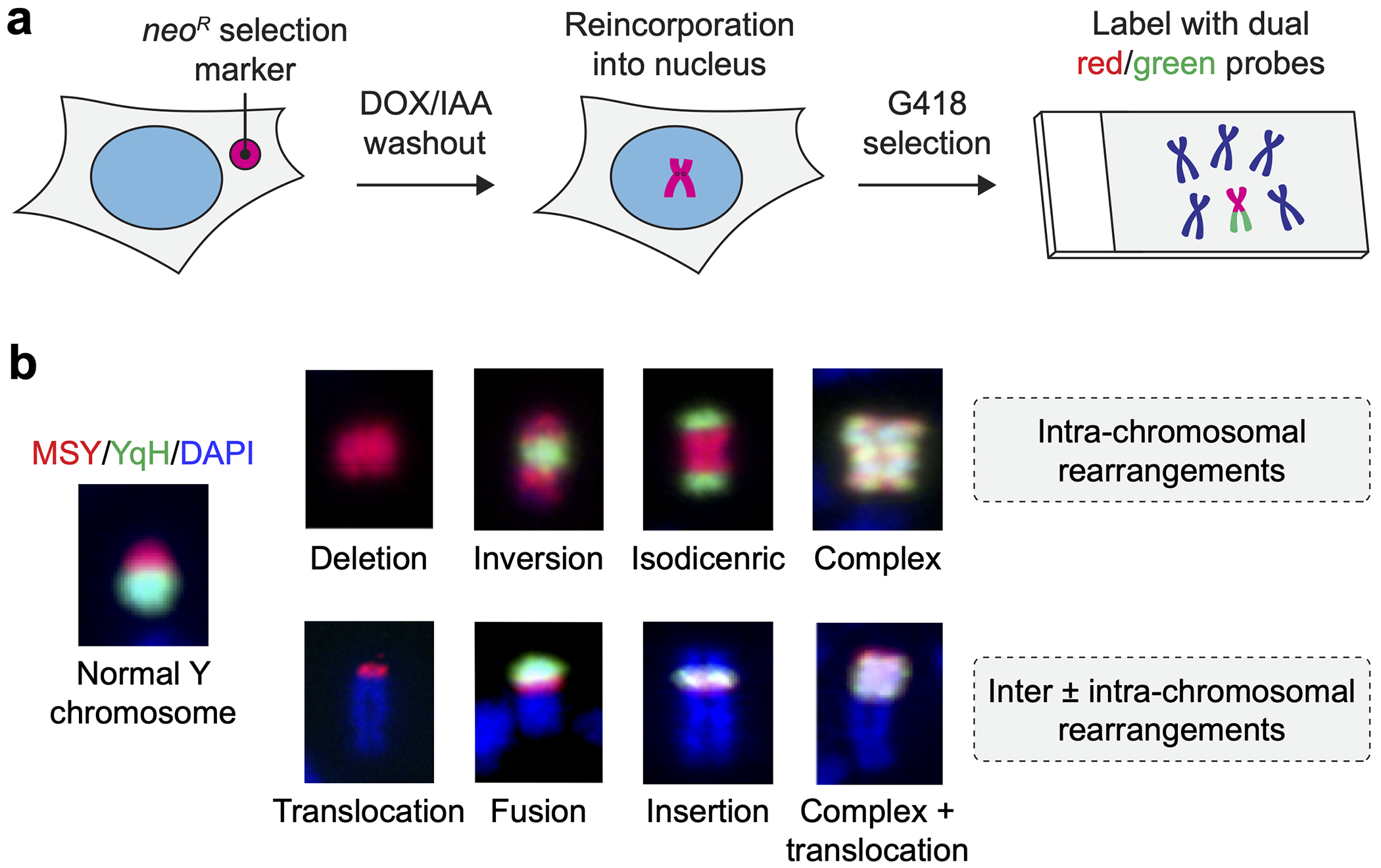

To enrich for cells that maintain the Y chromosome following centromere inactivation, we previously integrated a neomycin resistance gene (neoR) into the AZFa locus of the Y chromosome, which is located ~2.5 Mb away from the centromere on the Yq arm. Most cells will lose the neoR-encoding Y chromosome after the induction of Y-specific mis-segregation, rendering them sensitive to G418. After DOX/IAA washout and G418 treatment, the majority (>90%) of selected cells should retain the Y chromosome in the nucleus (Ly et al., 2019). Within this population of cells, different types of Y-specific rearrangements can be visualized by metaphase DNA FISH (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Cytogenetic detection of diverse Y chromosome rearrangements following selection for the Y-encoded neoR marker.

a) Schematic of micronucleus induction followed by washout and selection for retention of the Y chromosome AZFa locus. b) Examples of diverse Y chromosome rearrangement types visualized by metaphase FISH using dual colored paint probes.

5.1. Insertion of a neoR selection marker into the Y chromosome

Materials

T-REx Flp-In DLD-1 TIR1 + CENP-AEYFP-AID + CENP-AC-H3 cells

pUC57-LHA-EF1α-NeoR-RHA donor vector (GenScript or equivalent)

pSpCas9(BB)-2A-GFP vector (pX458, Addgene 48138)

sgRNA targeting AZFa locus

X-tremeGENE 9 DNA transfection reagent (Roche, XTG9-RO)

Opti-MEM I reduced serum medium (Gibco, 31985070)

Geneticin, G418 Sulfate (Gibco, 10131035)

Materials and reagents for PCR and agarose gel

Primers to screen for positive neoR integration at the AZFa locus:

5’- TTAGCCAATTTGCCACTCAG -3’ (forward)

5’- TAGTCTTGTAAATGCGGGCC -3’ (reverse)

Synthesize pUC57-based donor vector containing an EF1α promoter driving neoR flanked by 450-bp left and right homology arms of AZFa.

Synthesize a sgRNA (5′- AACACTTCTCTAGCACGATT-3′) targeting the Y chromosome AZFa locus at GRCh38 coordinate 12,997,776.

Clone the AZFa-targeting sgRNA into the BbsI restriction site of the pSpCas9(BB)-2A-GFP vector.

Seed 1 x 105 T-REx Flp-In DLD-1 TIR1 + CENP-AEYFP-AID + CENP-AC-H3 cells per well in a 6-well plate (3 wells in total). Use of growth medium without penicillin-streptomycin is recommended.

Co-transfect neoR donor vector and Cas9/sgRNA plasmid (ratio 9:1; use 1-2 μg of transfection-grade plasmid into cells using protocols described in 2.1 and 2.3).

1 day after transfection, wash cells and pool them into a 10 cm2 dish.

3-4 days after transfection, add 300 μg/mL G418 to culture medium for ~20 days while refreshing selection medium as needed.

Plate cells by limiting dilution (0.3 cells/well) into 96-well plates.

Select G418-resistant, single-cell-derived clones by PCR for targeted insertion of neoR into the AZFa locus using a forward primer located outside of the left AZFa homology arm and a reverse primer located within the EF1 promoter. See ref. (Ly et al., 2019) for additional details on primers and control primers.

5.2. Cell culture

The protocol described below enables transient inactivation of the Y chromosome centromere through the addition of DOX/IAA for 3 days followed by a washout and recovery period for an additional 3 days prior to G418 selection. This recovery period is important for reactivating the Y centromere by allowing endogenous CENP-AAID to recover and properly assemble into centromeric chromatin (Ly et al., 2019).

On day −1, seed T-Rex Flp-In TIR1 + CENP-AEYFP-AID + CENP-AC-H3 DLD-1 cells generated from step 5.1 into multi-well plates or 10 cm2 dishes.

On day 0, dilute doxycycline and auxin in growth medium to a final concentration of 1 μg/mL and 500 μM, respectively. Remove medium and replace with DOX/IAA-containing medium to cells. As a negative control, replace medium on a separate set of cells with growth medium without DOX/IAA.

On day 3, washout DOX/IAA by removing medium from the plate and wash 3x times with PBS. Add back fresh growth medium and return to incubator.

On day 6, re-plate cells (if needed) and add 300 μg/mL G418 to growth medium. Culture cells for ~10 days until selection is complete while refreshing medium and G418 as needed.

Collect metaphase spreads and perform FISH, as previously described in sections 4.2 and 4.3, respectively.

Note: During G418 selection, there will be a turnover between proliferating Y-positive cells and dying Y-negative cells, followed by a takeover of the culture by Y-positive cells.

5.3. Chromosome rearrangement analysis by metaphase FISH

Two-color FISH probes targeting opposite halves of the Y chromosome can be used to visualize different classes of structural rearrangements by cytogenetics (Figure 3b). We previously labeled the euchromatic portion of the male-specific region of the Y (MSY) spanning Yp and proximal Yq56 with commercially available paint probes in red and the repetitive heterochromatic region on distal Yq (YqH) with probes derived from a bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) clone (RP11-41H10) in green. Using this approach, normal Y chromosomes appear half red and half green, which enable deviations from this pattern to be easily discernable on metaphase spreads. Following metaphase FISH and image acquisition, high-quality metaphases are manually inspected for classification using the following criteria:

Normal Y: The normal Y chromosome is painted half red and half green with relatively equal size and clear separation at the red-green boundary. Note that the Y chromosome q-arm has a slightly wider and brighter DAPI appearance than the p-arm.

- Intra-chromosomal rearrangement

- Deletion: one or both arms appear truncated, producing a visible loss of red and/or green signal

- Inversion: banded appearance along the chromosome that can alternate between red and green signals

- Isodicentric: two intact copies of the Y are fused at either the Yp or Yq arm to form a mirror-imaged duplication

- Complex: the red and green signals overlap and co-localize with each other

- Inter-chromosomal rearrangement

- Translocation: a fragment of Y chromosome is joined with a non-homologous chromosome

- Fusion: a complete copy of Y chromosome fused with what appears to be a complete copy of a non-homologous chromosome

- Insertion: a fragment of the Y is inserted into an internal region of a non-homologous chromosome

Note: BACs can be obtained from BACPAC Resources Center (https://bacpacresources.org) and prepared as described (Ly et al., 2019; Shoshani et al., 2021).

Note: Combinations of different rearrangement types can be frequently observed; for example, a complex intra-chromosomal rearrangement combined with a translocation (Figure 3b).

Note: For quantification, depending on the experiment, a range between 30-300 metaphases per condition is generally recommended.

Note: Although chromothripsis cannot be formally called using cytogenetics, clones harboring complex rearrangements, as defined above, typically exhibited the predicted features of chromothripsis when analyzed by whole-genome sequencing (Ly et al., 2019).

6. Summary

Several approaches have been used to generate and study micronuclei with each offering a distinct set of advantages and disadvantages. Here we outline a general strategy to engineer stable human cell lines to induce micronuclei formation containing a specific chromosome-of-interest by inactivating its centromere and triggering chromosome mis-segregation. Using this approach, we have successfully recapitulated the series of events that result in chromothripsis, including chromosome fragmentation and the formation of a diverse spectrum of genomic rearrangements. We anticipate that this strategy will also be useful in studying mechanisms involved in chromosome segregation fidelity and the unique biological properties of micronuclei.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Cancer Prevention and Research Institute of Texas (RR180050 to P.L.), U.S. National Institutes of Health (R00CA218871 to P.L.), and The Welch Foundation (I-2071-20210327 to P.L.). We thank Marie Dumont and Catalina Salinas-Luypaert (Institut Curie) for suggestions and critical reading of the manuscript.

References

- Adhikari B, Narain A, and Wolf E. 2021. Generation of auxin inducible degron (AID) knock-in cell lines for targeted protein degradation in mammalian cells. STAR Protoc. 2:100949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cortes-Ciriano I, Lee JJ, Xi R, Jain D, Jung YL, Yang L, Gordenin D, Klimczak LJ, Zhang CZ, Pellman DS, Group PSVW, Park PJ, and Consortium P. 2020. Comprehensive analysis of chromothripsis in 2,658 human cancers using whole-genome sequencing. Nat Genet. 52:331–341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crasta K, Ganem NJ, Dagher R, Lantermann AB, Ivanova EV, Pan Y, Nezi L, Protopopov A, Chowdhury D, and Pellman D. 2012. DNA breaks and chromosome pulverization from errors in mitosis. Nature. 482:53–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dharmasiri N, Dharmasiri S, and Estelle M. 2005. The F-box protein TIR1 is an auxin receptor. Nature. 435:441–445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Earnshaw WC, Sullivan KF, Machlin PS, Cooke CA, Kaiser DA, Pollard TD, Rothfield NF, and Cleveland DW. 1987. Molecular cloning of cDNA for CENP-B, the major human centromere autoantigen. J Cell Biol. 104:817–829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fachinetti D, Folco HD, Nechemia-Arbely Y, Valente LP, Nguyen K, Wong AJ, Zhu Q, Holland AJ, Desai A, Jansen LE, and Cleveland DW. 2013. A two-step mechanism for epigenetic specification of centromere identity and function. Nat Cell Biol. 15:1056–1066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fachinetti D, Han JS, McMahon MA, Ly P, Abdullah A, Wong AJ, and Cleveland DW. 2015. DNA Sequence-Specific Binding of CENP-B Enhances the Fidelity of Human Centromere Function. Dev Cell. 33:314–327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray WM, del Pozo JC, Walker L, Hobbie L, Risseeuw E, Banks T, Crosby WL, Yang M, Ma H, and Estelle M. 1999. Identification of an SCF ubiquitin-ligase complex required for auxin response in Arabidopsis thaliana. Genes Dev. 13:1678–1691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guse A, Carroll CW, Moree B, Fuller CJ, and Straight AF. 2011. In vitro centromere and kinetochore assembly on defined chromatin templates. Nature. 477:354–358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatch EM, Fischer AH, Deerinck TJ, and Hetzer MW. 2013. Catastrophic nuclear envelope collapse in cancer cell micronuclei. Cell. 154:47–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann S, Dumont M, Barra V, Ly P, Nechemia-Arbely Y, McMahon MA, Herve S, Cleveland DW, and Fachinetti D. 2016. CENP-A Is Dispensable for Mitotic Centromere Function after Initial Centromere/Kinetochore Assembly. Cell Rep. 17:2394–2404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann S, and Fachinetti D. 2018. Real-Time De Novo Deposition of Centromeric Histone-Associated Proteins Using the Auxin-Inducible Degradation System. Methods Mol Biol. 1832:223–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holland AJ, Fachinetti D, Han JS, and Cleveland DW. 2012. Inducible, reversible system for the rapid and complete degradation of proteins in mammalian cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 109:E3350–3357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howman EV, Fowler KJ, Newson AJ, Redward S, MacDonald AC, Kalitsis P, and Choo KH. 2000. Early disruption of centromeric chromatin organization in centromere protein A (Cenpa) null mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 97:1148–1153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kepinski S, and Leyser O. 2005. The Arabidopsis F-box protein TIR1 is an auxin receptor. Nature. 435:446–451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leibowitz ML, Papathanasiou S, Doerfler PA, Blaine LJ, Sun L, Yao Y, Zhang CZ, Weiss MJ, and Pellman D. 2021. Chromothripsis as an on-target consequence of CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing. Nat Genet. 53:895–905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu S, Kwon M, Mannino M, Yang N, Renda F, Khodjakov A, and Pellman D. 2018. Nuclear envelope assembly defects link mitotic errors to chromothripsis. Nature. 561:551–555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ly P, Brunner SF, Shoshani O, Kim DH, Lan W, Pyntikova T, Flanagan AM, Behjati S, Page DC, Campbell PJ, and Cleveland DW. 2019. Chromosome segregation errors generate a diverse spectrum of simple and complex genomic rearrangements. Nat Genet. 51:705–715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ly P, and Cleveland DW. 2017. Interrogating cell division errors using random and chromosome-specific missegregation approaches. Cell Cycle. 16:1252–1258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ly P, Teitz LS, Kim DH, Shoshani O, Skaletsky H, Fachinetti D, Page DC, and Cleveland DW. 2017. Selective Y centromere inactivation triggers chromosome shattering in micronuclei and repair by non-homologous end joining. Nat Cell Biol. 19:68–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masumoto H, Masukata H, Muro Y, Nozaki N, and Okazaki T. 1989. A human centromere antigen (CENP-B) interacts with a short specific sequence in alphoid DNA, a human centromeric satellite. J Cell Biol. 109:1963–1973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muro Y, Masumoto H, Yoda K, Nozaki N, Ohashi M, and Okazaki T. 1992. Centromere protein B assembles human centromeric alpha-satellite DNA at the 17-bp sequence, CENP-B box. J Cell Biol. 116:585–596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishimura K, Fukagawa T, Takisawa H, Kakimoto T, and Kanemaki M. 2009. An auxin-based degron system for the rapid depletion of proteins in nonplant cells. Nat Methods. 6:917–922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruegger M, Dewey E, Gray WM, Hobbie L, Turner J, and Estelle M. 1998. The TIR1 protein of Arabidopsis functions in auxin response and is related to human SKP2 and yeast grr1p. Genes Dev. 12:198–207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santaguida S, Richardson A, Iyer DR, M’Saad O, Zasadil L, Knouse KA, Wong YL, Rhind N, Desai A, and Amon A. 2017. Chromosome Mis-segregation Generates Cell-Cycle-Arrested Cells with Complex Karyotypes that Are Eliminated by the Immune System. Dev Cell. 41:638–651 e635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santaguida S, Tighe A, D’Alise AM, Taylor SS, and Musacchio A. 2010. Dissecting the role of MPS1 in chromosome biorientation and the spindle checkpoint through the small molecule inhibitor reversine. J Cell Biol. 190:73–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shoshani O, Brunner SF, Yaeger R, Ly P, Nechemia-Arbely Y, Kim DH, Fang R, Castillon GA, Yu M, Li JSZ, Sun Y, Ellisman MH, Ren B, Campbell PJ, and Cleveland DW. 2021. Chromothripsis drives the evolution of gene amplification in cancer. Nature. 591:137–141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soto M, Raaijmakers JA, Bakker B, Spierings DCJ, Lansdorp PM, Foijer F, and Medema RH. 2017. p53 Prohibits Propagation of Chromosome Segregation Errors that Produce Structural Aneuploidies. Cell Rep. 19:2423–2431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephens PJ, Greenman CD, Fu B, Yang F, Bignell GR, Mudie LJ, Pleasance ED, Lau KW, Beare D, Stebbings LA, McLaren S, Lin ML, McBride DJ, Varela I, Nik-Zainal S, Leroy C, Jia M, Menzies A, Butler AP, Teague JW, Quail MA, Burton J, Swerdlow H, Carter NP, Morsberger LA, Iacobuzio-Donahue C, Follows GA, Green AR, Flanagan AM, Stratton MR, Futreal PA, and Campbell PJ. 2011. Massive genomic rearrangement acquired in a single catastrophic event during cancer development. Cell. 144:27–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan X, Calderon-Villalobos LI, Sharon M, Zheng C, Robinson CV, Estelle M, and Zheng N. 2007. Mechanism of auxin perception by the TIR1 ubiquitin ligase. Nature. 446:640–645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voronina N, Wong JKL, Hubschmann D, Hlevnjak M, Uhrig S, Heilig CE, Horak P, Kreutzfeldt S, Mock A, Stenzinger A, Hutter B, Frohlich M, Brors B, Jahn A, Klink B, Gieldon L, Sieverling L, Feuerbach L, Chudasama P, Beck K, Kroiss M, Heining C, Mohrmann L, Fischer A, Schrock E, Glimm H, Zapatka M, Lichter P, Frohling S, and Ernst A. 2020. The landscape of chromothripsis across adult cancer types. Nat Commun. 11:2320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss E, and Winey M. 1996. The Saccharomyces cerevisiae spindle pole body duplication gene MPS1 is part of a mitotic checkpoint. J Cell Biol. 132:111–123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood KW, Lad L, Luo L, Qian X, Knight SD, Nevins N, Brejc K, Sutton D, Gilmartin AG, Chua PR, Desai R, Schauer SP, McNulty DE, Annan RS, Belmont LD, Garcia C, Lee Y, Diamond MA, Faucette LF, Giardiniere M, Zhang S, Sun CM, Vidal JD, Lichtsteiner S, Cornwell WD, Greshock JD, Wooster RF, Finer JT, Copeland RA, Huang PS, Morgans DJ Jr., Dhanak D, Bergnes G, Sakowicz R, and Jackson JR. 2010. Antitumor activity of an allosteric inhibitor of centromere-associated protein-E. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 107:5839–5844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yen TJ, Li G, Schaar BT, Szilak I, and Cleveland DW. 1992. CENP-E is a putative kinetochore motor that accumulates just before mitosis. Nature. 359:536–539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yesbolatova A, Natsume T, Hayashi KI, and Kanemaki MT. 2019. Generation of conditional auxin-inducible degron (AID) cells and tight control of degron-fused proteins using the degradation inhibitor auxinole. Methods. 164-165:73–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang CZ, Leibowitz ML, and Pellman D. 2013. Chromothripsis and beyond: rapid genome evolution from complex chromosomal rearrangements. Genes Dev. 27:2513–2530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang CZ, Spektor A, Cornils H, Francis JM, Jackson EK, Liu S, Meyerson M, and Pellman D. 2015. Chromothripsis from DNA damage in micronuclei. Nature. 522:179–184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]