SUMMARY

A target identification platform derived from the bioorthogonal activation of reactive species is described. We explore the reactivity of halogenated enamine N-oxides and report that the previously undisclosed α,γ-halogenated enamine N-oxides can be reduced biooorthogonally by diboron reagents to produce highly electrophilic α,β-unsaturated haloiminium ions suitable for labeling a range of amino acid residues on proteins in a 1,2- or 1,4-fashion. Affinity labeling reagents bearing this motif enable ligand-directed protein modification and afford highly sensitive and selective target identification in unbiased chemoproteomics experiments. Target identification is supported in both cell lysate and live cells.

Graphical Abstract

eTOC blurb

A platform for target identification using bioorthogonally activated reactive species (BARS) has been developed. The rapid, chemically induced reduction of halogenated enamine N-oxides is employed to generate highly electrophilic haloiminium ions capable of labeling proteins in a ligand-dependent manner. Affinity labeling reagents leveraging this chemistry were applied in immunoblot-based target validation and unbiased chemoproteomics experiments to demonstrate the utility of this method in both cell lysate and live cells.

INTRODUCTION

Target identification (ID) refers to the process of identifying the molecular targets of a pharmacologically active small molecule as well as the collection of off-target proteins that contribute to the overall risk profile of a drug candidate.1-4 Essential from the earliest stages of drug discovery, target ID plays an important role through lead development.5 Yet, this process can be challenging and is often the rate limiting step in phenotype-driven drug discovery campaigns.6,7

Direct target ID is canonically performed by affinity purification of ligand-binding proteins on small molecule-modified solid support, a strategy best suited for tight ligand binding interactions with Kd’s in the low nanomolar range.8 For weaker interactions typical of hits from primary phenotypic screens, an alternate strategy of label transfer is frequently employed. This has primarily been the domain of photoaffinity labeling (PAL).9

In general, label transfer strategies feature a trifunctional molecule comprising ligand, affinity handle, and reactive species or precursors thereof (Figure 1A). Notwithstanding developments in ligand-directed acylation chemistry by Hamachi and co-workers,10 reactive species are frequently caged as precursor compounds to minimize the reactivity of unbound ligand and enable selective ligand-dependent labeling of target proteins. Photoreactive functional groups benzophenone,11 aryl azide,12 and diazirine13 are exemplars of this type of inducible reactivity (Figure 1B). Despite the storied use of PAL reagents, ongoing efforts to improve upon the gold standard diazirine reagent note the persistent challenges of high false positive and negative rates associated with these tools.14 Recent complements to PAL include μMap15 and electroaffinity16 labeling strategies.

Figure 1. Label transfer-based target identification strategies.

(A) General affinity labeling strategy for target identification applications. (B) Reactive species used in photoaffinity labeling. (C) Chemically inducible reactive species based on the bioorthogonal reduction of enamine N-oxides with diboron reagents.

A reagent-driven method involving the bioorthogonal induction of a highly reactive species is an alternate approach with potential benefits of complementarity and convenience in target ID applications. While bioorthogonally-inducible reactive species have been reported for chemical crosslinking,17 bioorthogonal platforms with suitable reactivity and selectivity for target identification have yet to be described. In this report, we describe bioorthogonally activated reactive species (BARS) capable of ligand-dependent protein labeling. Employing a mild and rapid reaction between halogenated enamine N-oxides and diboron reagents,18–20 we demonstrate the significance of this platform for target identification (Figure 1C).

RESULTS

Halogenated enamine N-oxides are able precursors to a range of reactive electrophiles (Figure 2A). In prior work describing hypoxia prodrugs and imaging agents, we described the synthesis of γ-halogenated enamine N-oxides, which undergo reductive activation by hemeproteins in the absence of oxygen to produce α,β-unsaturated iminium ions.19 We demonstrated that these electrophiles label hypoxic tumor tissue effectively. Subsequent disclosure of a bioorthogonal hydroamination reaction of terminally halogenated linear alkynes21 made possible access to enamine N-oxides combinatorially halogenated at the α-, γ-, or α,γ-positions. We envisioned that reduction of α-halogenated enamine N-oxides would generate Ghosez-type reagents22 and undergo α-elimination to reactive keteniminium ions while α,γ-halogenated variants would give rise to α,β-unsaturated haloiminium ions. Each is a highly reactive species difficult to access bioorthogonally or otherwise.

Figure 2. Characterization of amino acid and protein labeling by bioorthogonally activated reactive species.

(A) Reactive species derived from enamine N-oxides. (B) BSA (0.1 mg/mL) was labeled by reductive activation of enamine N-oxides 1–3 with B2(OH)4 over 10 min in PBS, conjugated to biotin, and analyzed by streptavidin blot. (C) Amino acid addition products. 50 mM N-oxide 7a was activated with 60 mM B2(OH)4 in the presence of 500 mM (a) Ac-Lys-OH, (b) Ac-Cys-OH, and (c) Ac-His-OH. The quenched product 13 was observed as a major byproduct in each reaction. (D) Myoglobin (Mb), bovine serum albumin (BSA), carbonic anhydrase (CA), and lysozyme were labeled with probe 7b and diboron in PBS, pH 7.4, digested with trypsin, and analyzed by LC-MS/MS. Number of unique residues labeled by 1,2- or 1,4-addition with at least 2 peptide-spectrum matches (PSMs) and number of PSMs.

To select the reactive species most appropriate for protein labeling, a high concentration of enamine N-oxides 1–3 (100 μM) was combined with bovine serum albumin (BSA, 0.1 mg/mL) in PBS, pH 7.4 then treated with 200 μM B2(OH)4 (Figure 2B). Alkyne-labeled BSA was further functionalized with biotin by copper-catalyzed azide-alkyne cycloaddition (CuAAC) and analyzed by streptavidin blot. Bromoiminium ion 6 labeled protein best, and its precursor N-oxide 3 was advanced.

Bromoiminium ions react with a variety of nucleophiles in either 1,2- or 1,4- fashion (Figure 2C, S2). When enamine N-oxide 7a (50 mM) was reduced with B2(OH)4 (60 mM) in the presence of Ac-Lys-OH (500 mM), 1,2-addition product amidine 8 was obtained and isolated in 8.2% yield. In contrast, when Ac-His-OH was employed, only the 1,4-adduct 12 was isolated in 37% yield. A trace product with the mass of a 1,2-adduct was observed in the reaction mixture by LCMS; however, it was unstable to isolation. A combination of 1,2- and 1,4-adducts 9–11 was observed when Ac-Cys-OH was employed. 1,2-Adduct 9 was obtained in 28% yield, 1,2/1,4-adduct 10 in 10% yield, and 1,4-adduct 11 in 48% yield.

Importantly, a significant byproduct of each amino acid reaction was amide 13. This product was obtained in 75%, 12%, and 47% yields from the reactions involving N-acetyl lysine, cysteine, and histidine, respectively. Haloiminium ions react rapidly with water, providing an innate mechanism for reactive species quenching and ensuring a means of inhibiting the indiscriminate labeling of protein. Addition of N-acetyl amino acids to a solution of probe 7a pre-activated with B2(OH)4 in PBS for 10 min did not result in any adduct formation (Figure S3). Relative rates of quenching, on-target protein reaction, and diffusion dictates the balance between false positive and negative rates in target identification.

To probe how the labeling of amino acid residues on proteins would compare to that of isolated amino acids, we performed site identification studies on a protein cocktail consisting of myoglobin (Mb), BSA, carbonic anhydrase (CA), and lysozyme (Figure 2D, S4). Following reductive activation of N-oxide 7b (100 μM) and labeling, proteins were trypsin digested, and the labeling sites were determined by LC-MS/MS. Residues labeled by 1,2- or 1,4-addition were identified by +237 or +255 Da modifications, respectively. As expected, lysine was the primary amino acid residue labeled by 1,2-addition and histidine by 1,4-addition. Across both modifications, they exhibited the greatest number of unique residues modified, with histidine outpacing lysine when normalized by residue abundance (Figure S5). Other amino acid residues such as glutamic acid, serine, and cysteine, while less prevalent, also exhibited significant labeling. Notably, we observed a negligible incidence of BARS modification at non-nucleophilic residues (Figure 2D).

To evaluate the feasibility of targeted protein labeling employing α-bromoiminium ion electrophiles, a trifunctional compound featuring N-oxide, alkyne, and carbonic anhydrase inhibitor sulfonamide (21) was constructed (Scheme 1). Hydroxylamine 16 was obtained in two steps from 4-pentyn-1-ol (14) by iodination under Appel conditions and nucleophilic displacement with N-methylhydroxylamine. Alkyne 20 could likewise be accessed in short order by Schreiber ozonolysis of cyclopentene (17),23 Grignard addition with ethynylmagnesium bromide, bromination of terminal alkyne 18 with N-bromosuccinimide and silver nitrate, chlorination of propargylic alcohol 19 under Appel conditions, and saponification of the methyl ester. Sulfonamide (21) was sequentially coupled to a PEG3-diamine linker and acid 20 with EDC. Hydroamination of 1-bromoalkyne 23 with hydroxylamine 16 in 20% TFE/CHCL3 at 50 °C yielded N-oxide-modified probe 21a. A companion diazirine probe 21b was also synthesized (Figure 3A).

Scheme 1. Synthesis of sulfonamide N-oxide probe 21a.

Conditions: (a) PPh3, I2, imidazole, THF, 79%; (b) MeNHOH·HCl, NEt3, DMSO, 70 °C, 75%; (c) O3, 5:1 CH2Cl2/MeOH, −78 °C; Ac2O, NEt3; (d) ethynylmagnesium bromide, THF, 0 °C, 72%; (e) NBS, AgNO3, acetone, 90%; (f) PPh3, NCS, THF, 50 °C, 55%; (g) 2 M NaOH, MeOH, THF, 92%; (h) PEG3-diamine, EDC·HCl, HOBt, iPr2NEt, DMF, 67%; (i) 20% TFA/CH2Cl2; then 20, EDC·HCl, iPr2NEt, DMF, 58%; (j) 16, 20% TFE/CHCl3, 50 °C, 78%.

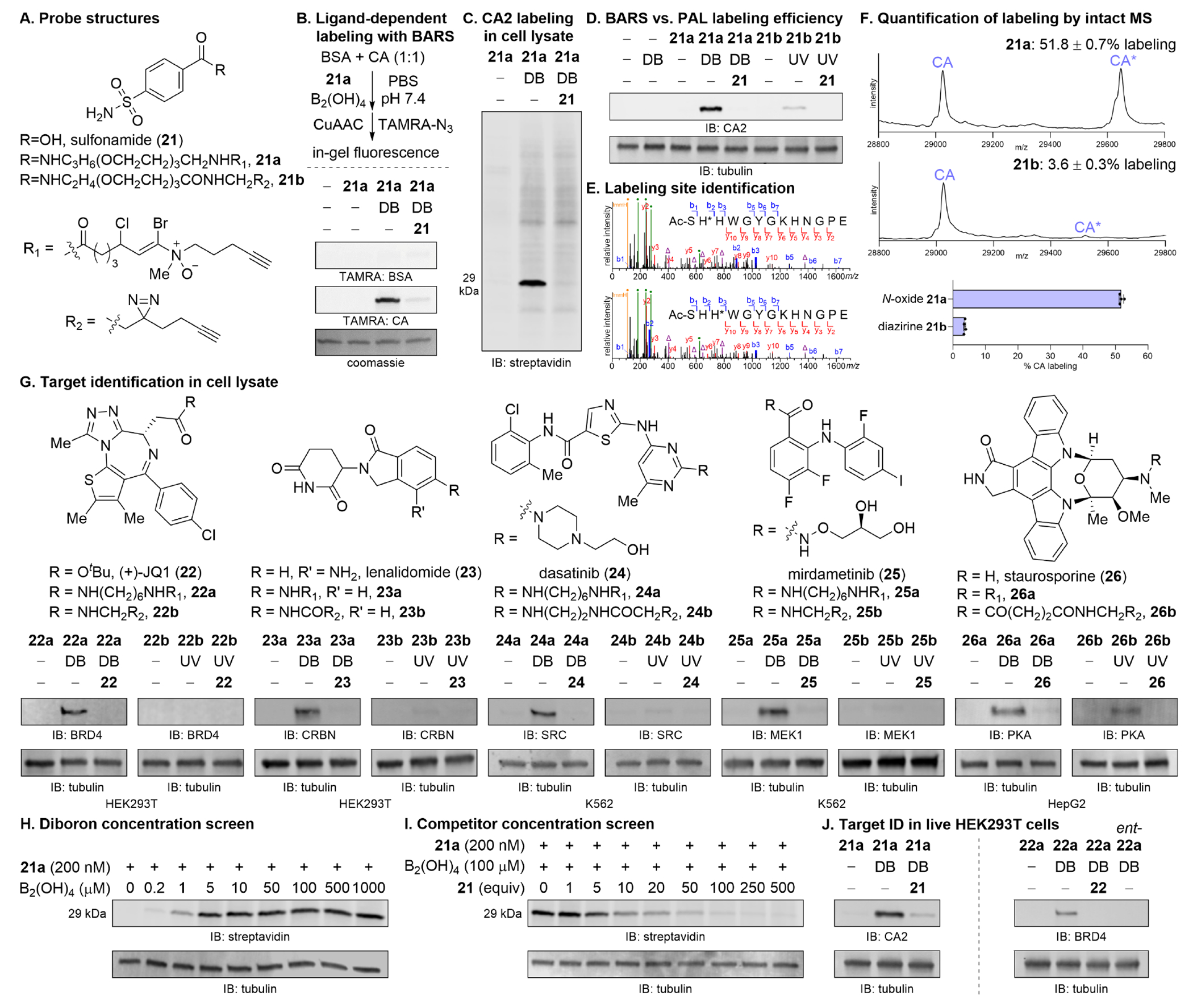

Figure 3. Ligand-dependent labeling of protein targets using bioorthogonally activated reactive species.

(A) Structures of sulfonamide (21) and corresponding BARS (21a) and PAL (21b) reagents. (B) Ligand-dependent labeling of purified proteins in vitro. BSA and CA (1:1, 0.1 mg/mL) were treated with N-oxide probe 21a (200 nM) with or without B2(OH)4 (100 μM) and with or without sulfonamide (21, 50 μM) in PBS, pH 7.4 for 10 min. Tetramethylrhodamine (TAMRA)-azide was conjugated by CuAAC then imaged by in-gel fluorescence. See Figure S9 for full gel. (C) HEK293T cell lysate was treated as in (B). Biotin picolyl azide was conjugated and the labeled lysate was imaged by streptavidin blot. CA is 29 kDa. (D) HEK293T cell lysate was treated with BARS (21a) or PAL (21b) reagents as in (B). Diazirine 21b was UV irradiated for 10 min. Biotin conjugation, avidin pulldown, and immunoblotting against CA2 on the enriched proteins demonstrates superior labeling by N-oxide 21a. See Figure S12 for full gel and quantification by densitometry. (E) Modified peptides detected in site identification of samples from (D). b/y-ions, blue/red; probe fragment (green •); probe neutral loss (purple Δ); histidine immonium ion (orange •). Y-axis is cropped; see Figure S13 for full spectrum. (F) Intact mass spectrometry of CA labeled with 21a (10 μM) and B2(OH)4 (100 μM) or 21b (10 μM) and UV irradiation for 10 min. (G) Cell lysate from the indicated cell lines were treated with either BARS or PAL probe (1 μM), activated with B2(OH)4 (100 μM) or UV irradiation for 10 min, biotin conjugated, pulled down with avidin, and immunoblotted against validated targets. Data for each pair of enamine N-oxide and diazirine probe were from the same Western blot and presented with the same image settings. See Figures S15–S17, S19–S20 for full Western blots along with images with alternative brightness/contrast settings for diazirine probes. (H) HEK293T cell lysate was treated with probe 21a (200 nM) and activated with varying concentrations of B2(OH)4. (I) Labeling in HEK293T cell lysate by probe 21a (200 nM) and B2(OH)4 (100 μM) was competed away with varying concentrations of sulfonamide 21. (J) Live HEK293T cells were treated with probe 21a or 22a (5 μM) for 2 h, washed, activated with B2(OH)4 (100 μM) for 10 min, washed, then analyzed by blot against CA2 and BRD4, respectively, to demonstrate target engagement in live cells. DB, diboron; UV, 365 nm.

Probe in hand, we demonstrated that ligand-directed labeling could be performed in vitro with purified protein (Figure 3B). An equimolar mixture of BSA and CA was treated with probe 21a (200 nM) in PBS, pH 7.4 and activated with B2(OH)4 (100 μM) for 10 min. Protein labeling was analyzed by click conjugation of TAMRA-azide and in-gel fluorescence imaging. CA was preferentially labeled over BSA, and critically, labeling of CA but not BSA could be competed away with excess sulfonamide (21, 50 μM). Endogenous levels of CA in HEK293T cell lysate could also be labeled using N-oxide 21a (200 nM) and B2(OH)4 (100 μM). Here, biotin was conjugated to the alkyne-modified protein and the labeled lysate was directly analyzed by streptavidin blot (Figure 3C). Labeling was again dependent on diboron and could be competed away with excess ligand. As a control, the labeling experiment was performed analogously with 50-fold additional probe 7b (10 μM). Labeling of CA could not be detected by streptavidin blot (Figure S10).

Ligand-directed labeling of CA in HEK293T cell lysate was performed analogously with diazirine 21b. Only, the treatment with diboron was substituted with UV irradiation (365 nm) for 10 min (Figure S11). Biotin modification and avidin pulldown followed by immunoblotting against CA on the enriched proteins revealed the superior labeling efficiency of BARS over PAL, the current gold standard, for this substrate (Figure 3D).

Intact mass spectrometry of CA treated with either probe 21a (10 μM) and B2(OH)4 (100 μM) or 21b and UV irradiation revealed 51.8% labeling of CA by the enamine N-oxide and 3.6% by the diazirine, a 14.4-fold improvement (Figure 3F). CA modified in like manner and purified from excess reagent was then subjected to site identification studies. Two peptides labeled at either His2 or His3 of the N-terminal SHHWGYGKHNGPE sequence were identified (Figure 3E).14,15,24,25 Both histidines are located at the lip of the CA ligand binding pocket and in close spatial proximity to the reactive species upon ligand target engagement (Figure S14).

Finally, illustrating the generality of the BARS platform, we assembled a collection of molecules [BET bromodomain inhibitor (+)-JQ1 (22), cereblon inhibitor lenalidomide (23), promiscuous Src kinase/BCR-ABL1 inhibitor dasatinib (24), MEK1 kinase inhibitor mirdametinib (25), and pro-apoptotic pan-kinase inhibitor staurosporine (26)]. Each was modified with an N-oxide or diazirine14,15,25-27 and evaluated for their capacity to identify targets in an activation- and ligand-dependent manner (Figure 3G). A standard set of amine or carboxylic acid-conjugatable linkers were employed for the N-oxide probes while literature-reported linkers were employed for the diazirines. The linker length difference between N-oxide and diazirine comparands ranged between 2–9 non-hydrogen atoms. For promiscuous probes with additional validated targets, additional blots can be found in the Supporting Information (Figures S18, S21). Each BARS probe positively identified validated targets without fail. The low incidence of false negatives is notable. False negatives incurred by PAL probes under conditions directly parallel to those used for the BARS probes do not indicate an absolute inability of these probes to pull down the indicated targets. In some cases, higher probe concentrations, alternative cell lines, or alternative diazirine variants can yield positive target identifications (Supplementary Note S1).

Standard conditions for BARS labeling involve treatment of cell lysate with 1 μM probe and 100 μM B2(OH)4 for 10 min, and competition is performed using 50-fold excess of the parent ligand; however, B2(OH)4 concentrations as low as 5 μM can be used to identical effect (Figure 3H), and significant competition can be observed with as low as 10-fold excess ligand (Figure 3I). Given the remarkable bioorthogonality of B2(OH)4,18-20,28 we find minimal strategic value in using the reagents at their lower limits and expect that the built-in tolerances afford a more robust method.

We next evaluated the use of this platform in live cells (Figure 3J). Feasibility was anticipated based on the cell permeability of amine-N-oxide-bearing drugs such as AQ4N29 and our prior demonstration of bioorthogonal reduction of enamine N-oxides in live cells.20 Indeed, when HEK293T cells were treated with probe 21a (5 μM) for 2 h, washed, treated with B2(OH)4 (100 μM) for 10 min, washed, pelleted, lysed, and immunoblotted against CA2, the target was positively identified. Labeling could be ablated by withdrawing B2(OH)4 or by competition with 10-fold excess sulfonamide 21 (50 μM), as expected. Target ID was also successfully executed in live HEK293T cells using JQ1-derived enamine N-oxide probe 22a.

Successful target identification in cells with probes 21a and 22a using the BARS platform indicate that the enamine N-oxide motif alone is not prohibitive for cell permeability and that diboron penetrates the cell membrane, activates the enamine N-oxide, and successfully initiates selective protein target labeling inside cells; however, the cell permeability of the ligand-enamine N-oxide composite should be evaluated on a ligand-by-ligand basis. That the physicochemical properties of a ligand are altered by chemical modification is a fact to which neither BARS nor any other label transfer method is immune.25

Positive identification of validated targets through Western blot analysis provides an indication of the low false negative rate of the method described; however, target ID experiments are more commonly performed in a prospective manner without prior knowledge of the true target or targets. In this instance, a method with a low false positive rate is essential. To gain a better understanding of how the method performs in an unbiased target ID study, we carried out pulldown-MS chemoproteomics experiments.

With sulfonamide (21) as the first subject, samples were prepared identically to prior Western blot experiments through the avidin pulldown step. Captured proteins were then eluted from solid support and subjected to trypsin digestion, LC-MS/MS, and label-free quantification. Experiments were performed in quadruplicate, and a hit was defined to be proteins with an abundance ratio >2 and a p-value <0.01. Data are displayed in volcano plots featuring pairwise comparisons of probe 21a against unactivated probe or in competition with excess sulfonamide (21) (Figures 4A, 4B). In each case, CA2 was identified as the sole hit. The data are notable not just for the exclusivity of the true positive but also for the exceptional fold change in protein abundance observed against both negative controls. The isolation of the CA2 hit is remarkable when juxtaposed with the results of diazirine analog 21b (Figures 4C, 4D).

Figure 4. Target identification using mass spectrometry-based chemoproteomics.

Volcano plots of HEK293T cell lysate labeled with probe (A) 21a with or without B2(OH)4, (B) 21a with or without 21, (C) 21b with or without UV irradiation, (D) 21b with or without 21, (E) 22a with or without 22, (F) 22b with or without 22, (G) 22a with or without 22, (H) 22a versus ent-22a. (A)–(F): Protein identifications were filtered to a minimum of 3 quantified peptides in 3 replicates; (G)–(H): Protein identifications were filtered to a minimum of 1 quantified peptide in 3 replicates. Hit threshold: fold change >2, p-value <0.01. Conditions: Probe (1 μM), B2(OH)4 (100 μM), competitor (50 μM).

Further substantiating the described method for unbiased chemoproteomics, we performed target identification with (+)-JQ1 (22). Here, we employed enamine N-oxide 22a in competition with parent drug (+)-JQ1 and in conjunction with the inactive (−)-JQ1 analog ent-22a. When the proteomics data were processed identically to the CA2 samples with a protein identification threshold of 3 quantified peptides in 3 replicates, we identified BRD4 as expected (Figures 4E, S30). The stringency of the filter could be reduced to a minimum of 1 quantified peptide in 3 replicates without introduction of appreciable background, enabling us to identify proteins more than 200-fold less abundant than CA2.30 Against competitor or enantiomer controls, BRD2/3/4 were correctly identified as hits with just three false positives in the former and one in the latter (Figures 4G,H). Significantly, the availability of at least two controls for any compound facilitates the curation of protein hits for validation; each of the false positives for (+)-JQ1-derived probe 22a could be eliminated in this fashion. The results for diazirine probe 22b are presented in Figures 4F, S31.

DISCUSSION

We have described a bioorthogonally activated reactive species platform for protein target identification. Employing a rapid, reagent-driven method for accessing highly reactive haloiminium ions from α,γ-halogenated enamine N-oxides, we demonstrated that proteins can be labeled effectively in a ligand-dependent manner. Nucleophilic residues react with the potent electrophiles in either 1,2- or 1,4-fashion, and histidine and lysine are the primary targets of the reactive species. Hydrolysis of the reactive species provides a convenient and essential quenching mechanism for reactive species formed on probes that are not engaged with their protein target.

The BARS method for ligand-directed target identification has been shown to be effective on purified protein, in cell lysate, and in live cells. Labeling conditions involve the simple application of a commercially available diboron reagent (100 μM) for 10 min with cells or cell lysates treated with an enamine N-oxide-derived probe. The method is compatible with target validation in Western blot format or in unbiased target identification using chemoproteomics experiments. The data indicate that this method employing these bioorthogonally-inducible highly reactive electrophiles provides an effective platform for target identification with great sensitivity and low background labeling. The method compares favorably to the current gold standard methods in target identification and offers a convenient complement to existing methods.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Resource availability

Lead contact

Further information and requests for resources should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the lead contact, Justin Kim (Justin_Kim@dfci.harvard.edu).

Materials availability

All materials generated in this study are available from the lead contact.

Data and code availability

All data relevant to this paper has been provided in the supplemental information; any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this paper is available from the lead contact upon request.

Supplementary Material

Dataset S14. 1D NMR Spectra

Dataset S1. LFQ enamine N-oxide 21a ± B2(OH)4 (3 counts in 3 replicates)

Dataset S2. LFQ enamine N-oxide 21a ± 21 (3 counts in 3 replicates)

Dataset S3. LFQ diazirine 21b ± UV irradiation (3 counts in 3 replicates)

Dataset S4. LFQ diazirine 21b ± 21 (3 counts in 3 replicates)

Dataset S5. LFQ enamine N-oxide 22a ± 22 (3 counts in 3 replicates)

Dataset S6. LFQ diazirine 22b ± 22 (3 counts in 3 replicates)

Dataset S7. LFQ enamine N-oxide 22a ± 22 (1 count in 3 replicates)

Dataset S8. LFQ enamine N-oxide 22a vs. ent-22a (1 count in 3 replicates)

Dataset S9. LFQ enamine N-oxide 21a ± B2(OH)4 (3 counts in 3 replicates), all 4 replicates

Dataset S10. LFQ enamine N-oxide 21a ± B2(OH)4 (1 count in 3 replicates)

Dataset S11. LFQ enamine N-oxide 21a ± 21 (1 count in 3 replicates)

Dataset S12. LFQ enamine N-oxide 22a ± ent-22a (3 counts in 3 replicates)

Dataset S13. LFQ diazirine 22b ± 22 (1 count in 3 replicates)

Supplemental Experimental Procedures

Highlights.

Reagent-driven platform for target identification using bioorthogonal activation

Access to highly reactive haloiminium ions that label proteins effectively

Ligand-directed protein modification is operable in cells and cell lysate

High sensitivity and low background labeling complements existing photochemical tools

Bigger picture.

Target identification is an important step in the drug discovery process that involves identifying the target of a pharmacologically active small molecule or the collection of off-target proteins that contribute to the overall risk profile of a drug candidate. In phenotype-driven drug discovery, target identification is often a rate-limiting yet essential step that precedes structure-guided drug development. Affinity-based label transfer strategies have been widely adopted for target identification and involve the induced covalent capture of a protein target directed by the ligand. Although photoaffinity labeling (PAL) is frequently used, more effective tools are desired. Here, we introduce a chemically activated reactive species platform that leverages bioorthogonal chemistry together with the unique chemistry of enamine N-oxides to enable target identification of bioactive small molecules with a level of sensitivity and specificity that compares favorably to existing methods.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was supported by grants to J.K. from NIH NIEHS (DP2 ES030448), the Claudia Adams Barr Program for Innovative Cancer Research, and the Harvard University William F. Milton Fund. S.S. was supported by a Chleck Foundation Graduate Student Fellowship. J.A.M. acknowledges generous support from the NIH (R01 CA233800, R21 CA247671), the Mark Foundation for Cancer Research, and the Massachusetts Life Science Center.

DECLARATION OF INTERESTS

J.K. has received sponsored research funding from Taiho previously. J.A.M. is a founder, equity holder, and advisor to Entact Bio, serves on the SAB of 908 Devices, and receives or has received sponsored research funding from Vertex, AstraZeneca, Taiho, Springworks, and TUO Therapeutics. J.K. and S.S. are inventors on a provisional U.S. patent application based in part on this work.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Schenone M, Dancik V, Wagner BK, and Clemons PA (2013). Target identification and mechanism of action in chemical biology and drug discovery. Nat. Chem. Biol 9, 232–240. 10.1038/nchembio.1199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Williams M. (2003). Target validation. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol 3, 571–577. 10.1016/j.coph.2003.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chan JN, Nislow C, and Emili A (2010). Recent advances and method development for drug target identification. Trends Pharmacol. Sci 31, 82–88. 10.1016/j.tips.2009.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Morgan P Brown DG, Lennard S, Anderton MJ, Barrett JC, Eriksson U, Fidock M, Hamren B, Johnson A, March RE, et al. (2018). Impact of a five-dimensional framework on R&D productivity at AstraZeneca. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov 17, 167–181. 10.1038/nrd.2017.244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bantscheff M, and Drewes G (2012). Chemoproteomic approaches to drug target identification and drug profiling. Bioorg. Med. Chem 20, 1973–1978. 10.1016/j.bmc.2011.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ha J, Park H, Park J, and Park SB (2021). Recent advances in identifying protein targets in drug discovery. Cell Chem. Biol 28, 394–423. 10.1016/j.chembiol.2020.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hart C (2005). Finding the target after screening the phenotype. Drug Discovery Today 10, 513–519. 10.1016/s1359-6446(05)03415-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Park J, Koh M, and Park SB (2013). From noncovalent to covalent bonds: a paradigm shift in target protein identification. Mol. BioSyst 9, 544–550. 10.1039/c2mb25502b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Murale DP, Hong SC, Haque MM, and Lee JS (2016). Photo-affinity labeling (PAL) in chemical proteomics: a handy tool to investigate protein-protein interactions (PPIs). Proteome Sci. 15, 14. 10.1186/s12953-017-0123-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tamura T, Ueda T, Goto T, Tsukidate T, Shapira Y, Nishikawa Y, Fujisawa A, and Hamachi I (2018). Rapid labelling and covalent inhibition of intracellular native proteins using ligand-directed N-acyl-N-alkyl sulfonamide. Nat. Commun 9, 1–12. 10.1038/s41467-018-04343-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Galardy RE, Craig LC, Jamieson JD, and Printz MP (1974). Photoaffinity Labeling of Peptide Hormone Binding Sites. J. Biol. Chem 249, 3510–3518. 10.1016/S0021-9258(19)42601-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fleet GWJ, Porter RR, and Knowles JR (1969). Affinity Labelling of Antibodies with Aryl Nitrene as Reactive Group. Nature 224, 511–512. 10.1038/224511a0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Smith RAG, and Knowles JR (1973). Aryldiazirines. Potential reagents for photolabeling of biological receptor sites. J. Am. Chem. Soc 95, 5072–5073. 10.1021/ja00796a062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.West AV, Amako Y, and Woo CM (2022). Design and Evaluation of a Cyclobutane Diazirine Alkyne Tag for Photoaffinity Labeling in Cells. J. Am. Chem. Soc 144, 21174–21183. 10.1021/jacs.2c08257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Trowbridge AD, Seath CP, Rodriguez-Rivera FP, Li BX, Dul BE, Schwaid AG, Buksh BF, Geri JB, Oakley JV, Fadeyi OO, et al. (2022). Small molecule photocatalysis enables drug target identification via energy transfer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 119, e2208077119. 10.1073/pnas.2208077119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kawamata Y, Ryu KA, Hermann GN, Sandahl A, Vantourout JC, Olow AK, Adams L-TA, Rivera-Chao E, Roberts LR, Gnaim S, et al. (2023). An electroaffinity labelling platform for chemoproteomic-based target identification. Nat. Chem. 15, 1267–1275. 10.1038/s41557-023-01240-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Row RD, Nguyen SS, Ferreira AJ, and Prescher JA (2020). Chemically triggered crosslinking with bioorthogonal cyclopropenones. Chem. Commun. (Cambridge, U. K.) 56, 10883–10886. 10.1039/D0CC04600K. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim J, and Bertozzi CR (2015). A Bioorthogonal Reaction of N-Oxide and Boron Reagents. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 54, 15777–15781. 10.1002/anie.201508861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kang D, Cheung ST, Wong-Rolle A, and Kim J (2021). Enamine N-Oxides: Synthesis and Application to Hypoxia-Responsive Prodrugs and Imaging Agents. ACS Cent. Sci 7, 631–640. 10.1021/acscentsci.0c01586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kang D, Lee S, and Kim J (2022). Bioorthogonal Click and Release: A General, Rapid, Chemically Revertible Bioconjugation Strategy Employing Enamine N-oxides. Chem 8, 2260–2277. 10.1016/j.chempr.2022.05.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kang D, Cheung ST, and Kim J (2021). Bioorthogonal Hydroamination of Push-Pull-Activated Linear Alkynes. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 60, 16947–16952. 10.1002/anie.202104863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marchand-Brynaert J, and Ghosez L (1972). Electrophilic aminoalkenylation of aromatics with α-chloroenamines. J. Am. Chem. Soc 94, 2869–2870. 10.1021/ja00763a061. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schreiber SL, Claus RE, and Reagan J (1982). Ozonolytic cleavage of cycloalkenes to terminally differentiated products. Tetrahedron Lett. 23, 3867–3870. 10.1016/S0040-4039(00)87729-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ficarro SB, Browne CM, Card JD, Alexander WM, Zhang T, Park E, McNally R, Dhe-Paganon S, Seo H-S, Lamberto I, et al. (2016). Leveraging Gas-Phase Fragmentation Pathways for Improved Identification and Selective Detection of Targets Modified by Covalent Probes. Anal. Chem 88, 12248–12254. 10.1021/acs.analchem.6b03394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Conway LP, Jadhav AM, Homan RA, Li W, Rubiano JS, Hawkins R, Lawrence RM, and Parker CG (2021). Evaluation of fully-functionalized diazirine tags for chemical proteomic applications. Chem. Sci. 12, 7839–7847. 10.1039/D1SC01360B. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li Z, Hao P, Li L, Tan CYJ, Cheng X, Chen GYJ, Sze SK, Shen H-M, and Yao SQ (2013). Design and Synthesis of Minimalist Terminal Alkyne-Containing Diazirine Photo-Crosslinkers and Their Incorporation into Kinase Inhibitors for Cell- and Tissue-Based Proteome Profiling. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 52, 8551–8556. 10.1002/anie.201300683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lin Z, Amako Y, Kabir F, Flaxman HA, Budnik B, and Woo CM (2022). Development of Photolenalidomide for Cellular Target Identification. J. Am. Chem. Soc 144, 606–614. 10.1021/jacs.1c11920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kang D, and Kim J (2021). Bioorthogonal Retro-Cope Elimination Reaction of N,N-Dialkylhydroxylamines and Strained Alkynes. J. Am. Chem. Soc 143, 5616–5621. 10.1021/jacs.1c00885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wilson WR, Denny WA, Pullen SM, Thompson KM, Li AE, Patterson LH, and Lee HH (1996). Tertiary amine N-oxides as bioreductive drugs: DACA N-oxide, nitracrine N-oxide and AQ4N. Br J Cancer Suppl 27, S43–S47. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang M, Herrmann CJ, Simonovic M, Szklarczyk D, and von Mering C (2015). Version 4.0 of PaxDb: Protein abundance data, integrated across model organisms, tissues, and cell-lines. Proteomics 15, 3163–3168. 10.1002/pmic.201400441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Dataset S14. 1D NMR Spectra

Dataset S1. LFQ enamine N-oxide 21a ± B2(OH)4 (3 counts in 3 replicates)

Dataset S2. LFQ enamine N-oxide 21a ± 21 (3 counts in 3 replicates)

Dataset S3. LFQ diazirine 21b ± UV irradiation (3 counts in 3 replicates)

Dataset S4. LFQ diazirine 21b ± 21 (3 counts in 3 replicates)

Dataset S5. LFQ enamine N-oxide 22a ± 22 (3 counts in 3 replicates)

Dataset S6. LFQ diazirine 22b ± 22 (3 counts in 3 replicates)

Dataset S7. LFQ enamine N-oxide 22a ± 22 (1 count in 3 replicates)

Dataset S8. LFQ enamine N-oxide 22a vs. ent-22a (1 count in 3 replicates)

Dataset S9. LFQ enamine N-oxide 21a ± B2(OH)4 (3 counts in 3 replicates), all 4 replicates

Dataset S10. LFQ enamine N-oxide 21a ± B2(OH)4 (1 count in 3 replicates)

Dataset S11. LFQ enamine N-oxide 21a ± 21 (1 count in 3 replicates)

Dataset S12. LFQ enamine N-oxide 22a ± ent-22a (3 counts in 3 replicates)

Dataset S13. LFQ diazirine 22b ± 22 (1 count in 3 replicates)

Supplemental Experimental Procedures

Data Availability Statement

All data relevant to this paper has been provided in the supplemental information; any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this paper is available from the lead contact upon request.