Abstract

Problematic anger is linked with multiple adverse smoking outcomes, including cigarette dependence, heavy smoking, and cessation failure. A smoking cessation intervention that directly targets anger and its maintenance factors may increase rates of smoking cessation. We examined the efficacy of an interpretation bias modification for hostility (IBM-H) to facilitate smoking cessation in smokers with elevated trait anger. Participants were 100 daily smokers (mean age = 38, 62% female, 55% white) with elevated anger were randomly assigned to eight computerized sessions of either IBM-H or a health and relaxation video control condition (HRVC). Participants in both conditions attempted to quit at mid-treatment. Measures of hostility, anger, and smoking were administered at pre-, mid-, post- treatment, as well as at up to three-month follow-up. Compared to HRVC, IBM-H led to greater reductions in hostile interpretation bias, both at posttreatment and follow-up. IBM-H also led to statistically significant reductions in hostility only at posttreatment, and trait anger only at three-month follow-up. Both conditions experienced reductions in smoking, although they did not differ in quit success. We discuss these findings in the context of literature on anger and smoking cessation and provide directions for future research.

Keywords: Interpretation bias modification, hostile interpretation bias, hostility, smoking, anger

Introduction

Cigarette smoking is the leading source of preventable death and disability in the United States (US), causing over 480,000 deaths each year, costing an estimated $240 billion in healthcare spending (Xu et al., 2021) and $372 billion in lost productivity (Shrestha et al., 2022). Although approximately 68.0% of current US adult smokers report wanting to quit smoking (Babb et al., 2017), only 7.5% succeed in quitting for six months or longer each year (Creamer et al., 2019). Moreover, the rate of relapse remains above 50% over the first year of abstinence, and relapsing remains a persistent risk over former smokers’ lifespans (García-Rodríguez et al., 2013).

Overall, smoking rates have been steadily declining due to concerted public health initiatives (Cornelius et al., 2022). Yet, the residual smoking population may be increasingly composed of sub-populations which are more vulnerable to nicotine addiction (Goodwin et al., 2018). Individuals with underlying mental health conditions make up one such sub-population (Ziedonis et al., 2008). Diagnosed psychopathology has also been linked to significantly higher rates of three-year smoking relapse (García-Rodríguez et al., 2013), and among adults who have smoked daily during some time in their lives, those experiencing mental illness were less likely to have quit (38.4%) than those with no mental illness (52.8%; Lipari & Van Horn, 2013).

One promising line of research has been to focus behavioral interventions on negative affect processes underlying smoking, cessation, and relapse (Garey et al., 2020; Morar & Robertson, 2022). An abundance of research has emerged linking negative mood states such as anxiety, sadness, and anger to cigarette dependence (Akbari et al., 2020) and increased risk of lapse following smoking cessation (Robinson et al., 2019). Moreover, smoking cessation leads to negative affect, which can trigger smoking urges (Benson et al., 2022). Integrated treatments focusing on negative affect reduction have been developed to facilitate cessation among smokers who are depressed or anxious, and such interventions have led to improved outcomes compared to traditional smoking cessation interventions (Smits et al., 2021).

Anger is one negative affect state that may play an important role in the maintenance of smoking and smoking relapse (Cougle et al., 2014). Smokers show elevated levels of anger compared to non-smokers (Cougle et al., 2013) and problematic anger is consistently and uniquely associated with cigarette dependence, heavy smoking, and cessation failure (Cougle et al., 2014). Further, in an ecological momentary assessment study of smokers, statistically significant and consistent relations were evident between greater anger symptoms and smoking urges (Whalen et al., 2001). In one study of pregnant women, anger, aggression, and hostility were predictive of smoking during pregnancy after controlling for symptoms of depression and stress (Eiden et al., 2011). A population-based study also found greater anger to predict past-year smoking status, cigarette dependence, and heavy smoking, even when adjusting for demographics and a range of psychiatric disorders (Cougle et al., 2013). Problematic anger also has been found to predict relapse following smoking cessation; one study of treatment-seeking smokers found that increases in anger following cessation predicted relapse (Patterson et al., 2008). Additionally, a prospective investigation of smokers undergoing a cessation attempt found greater trait anger to predict increases in state anger, craving, and withdrawal symptoms, as well as early relapse (al’ Absi et al., 2007), although these researchers did not control for other constructs related to the externalizing spectrum (e.g., impulsivity, self-control) or for general externalizing proneness. Taken together, anger broadly appears to be an important factor in predicting smoking cessation and relapse.

Cognitive models of anger propose that those predisposed to trait-like anger are more prone to interpret uncertain situations as actively hostile (Wilkowski & Robinson, 2008). Without further contextual cues, biased appraisals of situations and events can lead those with high trait anger to infer hostile intent from the actions of others. Such hostile interpretations (e.g., “That driver meant to cut me off!”) in turn result in the further experience of anger. Accordingly, several lines of research have also implicated trait hostility—the tendency to view others with suspicion, cynicism, and general mistrust—and hostile interpretation bias as important factors related to smoking status and cessation difficulties. Smokers have been found to score higher on measures of trait hostility than nonsmokers (Bernstein et al., 2014). Additionally, prospective research has found hostility to predict smoking initiation among adolescents (Weiss et al., 2011). Higher hostility was also predictive of lower odds of smoking cessation in a college sample followed for 20 years (Lipkus et al., 1994). Finally, hostility predicts smoking relapse across different clinical populations of smokers (Kahler et al., 2004).

Cognitive-behavioral approaches to the treatment of pathological anger target hostile interpretive biases via psychoeducation and cognitive restructuring (Gorenstein et al., 2007). More recently, researchers have focused on developing self-guided, computerized interpretation bias modification interventions targeting hostile interpretations to ambiguous situations (IBM-H). These hostility-targeting interventions have been applied to several clinical contexts, including alcohol use disorder (Cougle et al., 2017), veterans with post-traumatic stress disorder (Dillon et al., 2020), depression (Smith et al., 2018), and an outpatient mental healthcare facility (van Teffelen et al., 2021). In one study, IBM-H was applied as a treatment for individuals with pathological alcohol use and high self-reported anger. IBM-H was found to have a significant impact on hostility and anger expression, but only a marginally significant effect on trait anger (Cougle et al., 2017). A more recent randomized controlled trial (RCT) of IBM-H administered to a Dutch outpatient sample similarly found that IBM-H had a beneficial effect on hostile and benign interpretations relative to sham control (van Teffelen et al., 2021). Additionally, IBM-H was associated with greater reduction in behavioral aggression.

No such hostility-targeting interpretation bias protocol has been tested in the context of smoking cessation. In the present study, we tested an eight-session IBM-H intervention for smokers with elevated trait anger. Smokers interested in quitting who have elevated levels of trait anger were randomly assigned to receive IBM-H or health and relaxation videos control (HRVC) condition consisting of relaxing videos and psychoeducation on healthy habit building (matched for time). Smoking cessation dates for participants in both conditions were scheduled for the treatment midpoint, and smoking status was assessed throughout the intervention, and at 2-weeks, 4-weeks, 6-weeks, and 12-weeks post-cessation. We hypothesized that participants receiving IBM-H would have significant reductions in hostile interpretation bias, trait hostility, anger, depression, and smoking rates relative to those receiving HRVC. Further, we explored whether changes in hostile interpretation bias, hostility, or anger would account for condition-specific reductions in smoking behavior.

Methods

Participants

Participants (N =100) were recruited locally via Facebook online advertisements, community fliers, and bus advertisements between April 2015 and July 2019. With alpha set at 0.05, n = 100 was estimated to provide sufficient power (0.80) to detect small to medium effect sizes associated with IBM interventions (Martinelli et al., 2022). The study was advertised as a paid, computerized treatment study for smoking cessation. Eligible participants completed the initial baseline assessment, the mid-treatment/quit date assessment, the post-treatment/2-week post-quit assessment, as well as the 4-week, 6-week post-quit assessment, and 12-week post-quit assessments. Participants earned up to $250 for participating in the study. Participants received $10 for completing their first treatment session, and $5 for treatment sessions 2, 3, 4, 6, and 8. They also received $25 for completing the first five assessments, $35 for completing the last follow-up assessment, and a $30 bonus for completing all components of the study. Participants were sent email and text message reminders to come in for all follow-up assessments, which were completed in-person.

Participants included in the present trial were (1) English speakers, (2) between the ages of 18 and 65 who were (3) currently smoking an average of at least eight cigarettes per day, (4) had been daily smokers for at least one year, and had (5) not decreased their cigarette intake by more than half in the past six months. Participants additionally had to report (6) willingness to make a serious attempt to quit smoking and (7) a motivation to quit in the next 30 days of at least five on a 10-point scale (0 = “no motivation”; 10 = “extreme motivation). Finally, eligible participants (8) had to score 22 or higher (75th percentile) on the trait anger subscale of the State-Trait Anger Expression Inventory-2 (STAXI-2; Spielberger et al., 1999). Participants were excluded from this study if they (9) reported a current substance dependence (excluding cigarette dependence), (10) were presently using other tobacco products, (11) were receiving either cognitive behavioral therapy for any condition or any therapy targeting problematic anger, (12) had evidence of serious suicidal intent requiring hospitalization or immediate treatment, (13) demonstrated limited mental competency and the inability to give informed, written consent, (14) had evidence of psychotic-spectrum disorders, or (15) had made changes in medications taken for emotional difficulties in the past month. Prospective participants who met all eligibility requirements were randomized to either IBM-H (N = 51) or HRVC (N = 49) via a random sequence generator algorithm. Demographic characteristics are reported in Table 1.

Table 1.

Participant demographics across treatment conditions

| IBM-H | HRVC | |

|---|---|---|

| (n = 51) | (n = 49) | |

|

| ||

| Age in years: Mean (SD) | 39.3 (12.8) | 36.5 (11.9) |

| Gender: n (%) | ||

| Male | 23 (45.1%) | 22 (44.9%) |

| Female | 28 (54.9%) | 27 (55.1%) |

| Ethnicity: n (%) | ||

| White | 22 (68.8%) | 19 (55.9%) |

| Black | 7 (21.9%) | 6 (17.6%) |

| Hispanic | 2 (6.3%) | 5 (14.7%) |

| Native American | 1 (3.1%) | 3 (8.8%) |

| Asian | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (2.9%) |

| Educational Attainment: n (%) | ||

| Less than high school | 1 (2.0%) | 16 (32.7%) |

| High school diploma | 5 (9.8%) | 20 (40.8%) |

| Some college | 31 (60.8%) | 10 (20.4%) |

| Bachelor’s degree | 11 (21.6%) | 1 (2.0%) |

| Graduate degree | 3 (5.9%) | 2 (4.1%) |

| Psychological Treatment: n (%) | ||

| Current psychiatric medication | 12 (23.5%) | 10 (20.4%) |

| Current psychotherapy | 4 (8.2%) | 4 (8.2%) |

| Past psychiatric medication | 14 (27.5%) | 14 (28.6%) |

| Past psychotherapy | 23 (45.1%) | 28 (57.1%) |

| Smoking Frequency: Mean (SD) | ||

| Self-reported past week daily cigarettes | 15.7 (6.1) | 14.4 (5.6) |

| Breath carbon monoxide (ppm) | 25.5 (13.6) | 24.6 (13.6) |

Note: IBM-H = Interpretation Bias Modification for Hostility; HRVC = Healthy and Relaxing Video Control; ppm = parts per million; Ethnicity and race was not forced response (n =68).

Measures

Diagnostic interview

Sections of the Structured Clinical Interview for the DSM-IV Axis 1 Disorders, non-patient version (SCID-NP; First & Gibbon, 2004) were administered to assess for diagnostic exclusion criteria, as well as the prevalence of psychiatric diagnoses. Trained doctoral-level research staff administered the instrument and all interviews were audio-recorded.

Smoking behavior variables

Self-reported past-week smoking frequency.

Smoking behavior was assessed via the timeline follow-back method whereby the participants are asked to retrospectively estimate their daily cigarette intake over the seven-day period prior to each assessment. This method has been previously used in a wide array of substance treatment research contexts (Robinson et al., 2014).

Carbon monoxide levels and saliva cotinine analysis.

Smoking status was verified by the measurement of expired carbon monoxide excreted from the lungs administered at each post-cessation assessment. Expired air carbon monoxide levels were assessed with a Vitalograph Breathco carbon monoxide monitor, with a cut-off of 5ppm indicating abstinence (Jarvis et al., 1987). Additionally, saliva cotinine (cutoff value of 10ng/ml) was used at the 3-month post-quit follow-up assessment to verify abstinence (Dhavan et al., 2011).

Psychological variables

The Word Sentence Association Paradigm-Hostility (WSAP-H; Dillon et al., 2016) is a behavioral task measure of hostile interpretation bias. Per the WSAP-H, participants are presented with 38 distinct ambiguous sentences on a computer (e.g., “Your boss critiques your work.”). Each sentence is followed by either a hostile-related word (e.g., “condescending”) or a benign word (e.g., “helpful”). Participants are then asked to rate the word relates to the displayed sentence on a scale of 1 (“not at all related”) to 6 (“very related”). As a measure of hostile interpretation bias, the WSAP-H showed good-to-excellent internal consistency in this study at baseline (α = .89), posttreatment (α = .97), and follow-up (α = .96) and showed excellent internal consistency as a measure of benign interpretation bias at baseline (α = .92), posttreatment (α = .95), and follow-up (α = .96).

The Social Information Processing – Attribution Bias Questionnaire (SIP-ABQ; Coccaro et al., 2009) is a self-report measure that presents the participant with eight interpersonal scenarios with a negative outcome (e.g., “Suddenly, one of your co-workers bumps your arm and spills your coffee over your shirt.”). Each of these scenarios involves an ambiguous actor (e.g., the coworker), and the participant is asked to rate the likelihood of several sentences (e.g., “My co-worker wanted to burn me”; “My co-worker did it by accident”) on a scale ranging from 0 (not at all likely) to 3 (very likely). The SIP-ABQ was used as an auxiliary measure of hostile attribution bias and showed good internal consistency at baseline (α = .88) and excellent internal consistency at posttreatment (α = .92) and follow-up (α = .92).

The State-Trait Anger Expression Inventory-2 – Trait Anger Subscale (STAXI-2-Trait; Spielberger et al., 1999) is a ten item self-report measure of trait anger. Participants rate anger related statements on a scale of 1 (almost never) to 4 (almost always). In the current study, the STAXI-2-Trait showed acceptable internal consistency at baseline (α = .78) and good internal consistency at posttreatment (α = .87) and three-month follow-up (α = .88).

Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II; Beck et al., 1996) is a widely used 21-item measure of depression severity in adolescents and adults. The BDI-II which has shown high reliability and validity across a wide range of clinical and non-clinical contexts (Wang & Gorenstein, 2013). In the current study, the BDI-II showed excellent internal consistency at baseline (α = .92), posttreatment (α = .94), and follow-up (α = .94).

Cooke-Medley Hostility Scale (Barefoot et al., 1989) is a 50-item, true/false, self-report measure of hostility that was initially developed as a subscale of the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory. In the present study, the Cooke-Medley Hostility Scale was used as the primary measure of self-reported hostility and showed good internal consistency at baseline (α = .85), posttreatment (α = .84), and follow-up (α = .86).

Procedures

Procedural overview

All aspects of this study were approved by the Institutional Review Board of Florida State University and preregistered with clinical trials.gov (NCT02413814). After completing an over-the-phone screen, prospective participants were provided with informed consent and were scheduled to complete a brief clinical interview with a trained research assistant. Participants who met eligibility criteria completed pre-treatment measures then were randomly assigned one of two one-month computerized interventions targeting problematic anger, using the Qualtrics survey flow randomizer. Midway through treatments, participants underwent a smoking cessation attempt. They completed in-person assessments at mid-treatment (quit date), post-treatment, and 4-, 6-, and 12-week post-quit assessments. Sessions 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, and 8 were administered remotely, and sessions 5 and 7 were administered in-person, using lab computers.

Treatments

Psychoeducation.

At the beginning of the first treatment session, participants in both conditions were administered a ~20-minute computerized education module on problematic substance use and its consequences. Participants also received psychoeducation module on the dysfunctional consequences of smoking to reduce negative affect, including anger. This portion of the intervention was interactive, including quizzes throughout to ensure respondents understood the material presented.

Interpretation Bias Modification for Hostility (IBM-H).

The eight-session IBM-H is a computerized intervention targeting hostility. Each treatment session lasted approximately 30 minutes and consisted of two computerized tasks: (1) Sentence Completion and Comprehension, and (2) WSAP Training. These tasks have been used in tandem in several prior computerized treatment studies (Summers & Cougle, 2016; Wilver & Cougle, 2019). In the Sentence Completion and Comprehension Task, participants were asked to read one sentence scenarios and imagine themselves in the situations (e.g., “A driver does not let you over even though you have your blinker on”). Following this sentence, another sentence would appear on the screen to provide a less ambiguous interpretation of the scenario. However, one letter was missing from the key word of this sentence (E.g., “They can’t s_e you.”). The participant then filled in the missing letter of the word (E.g., “see”), thereby assigning a positive interpretation to the situation. Next, this new interpretation was reinforced by requiring the participants to correctly answer “yes” or “no” to a comprehension question (“Is the driver being disrespectful?”) before proceeding. For each of the eight sessions, 67 training scenarios were presented (536 training scenarios total), and participants never saw the same scenario twice over the course of the study.

The WSAP Training Task was adapted from Amir and Taylor (2012), and consists of 38 single sentence scenarios. First, a fixation cross appeared on the screen for 500 ms. Next, a word denoting an interpretation with either an anger-related negative/threat (e.g., the term “rude”) or positive/benign (“unknowing”) connotation appeared for 500 ms. Next, an ambiguous single sentence scenario appeared on screen (e.g., “you are trying to concentrate, and someone is talking loudly”). Participants were then asked whether the word was related to the sentence by responding “yes” or “no.” Participants received positive feedback (i.e., “You are correct!”) only when indicating positive/benign words as related to the sentence and rejecting negative/threat words as related. Conversely, participants received negative feedback (i.e., “Incorrect”) when rejecting positive/benign words as related to the sentence and indicating negative/threat words as related.

Health and Relaxation Video Control (HRVC).

Participants assigned to HRVC completed eight computerized sessions consisting of psychoeducation on healthy behaviors. This control condition has been used in prior IBM treatment studies and were perceived as credible in these studies (Cougle et al., 2017; Smith et al., 2018). These sessions were matched for time with the active condition, and covered topics such as exercise, diet, hygiene, social support, healthy activities, and sleep. Afterwards, relaxing videos were played wherein participants were invited to close their eyes and focus their attention on the present moment while listening to relaxing piano music and songbirds. At the conclusion of the study, participants were provided with the option of obtaining IBM-H treatment free of charge.

Nicotine Replacement Therapy.

All participants received Nicoderm CQ®, 24-hour transdermal nicotine patches and were educated about the use of the patch at the computerized session immediately prior to their designated quit date. Participants were instructed to apply one patch daily, beginning on the quit date. Participants were to use a 21 mg patch for four weeks, a 14 mg patch for the next two weeks, and then a seven mg patch for the last two weeks. Those who continued to smoke or lapse after quit day were not instructed to discontinue the patch until their smoking level reached four cigarettes per day for four days. Smokers who lapsed during treatment were encouraged to set a new quit date and continue their cessation attempt.

Data Analytic Plan

All analyses followed an intent-to-treat strategy that included all randomized participants. To examine the effects of treatment on main outcome variables, a latent difference score (LDS) approach was used (Mara et al., 2012; Mun et al., 2009). This approach allows for the modeling of treatment effects at multiple timepoints in one model. LDS was used over more traditional methods such as analysis of variance (ANOVA) because it reduces the total number of analyses, as a single model can be used to examine between and within group treatment effects for an outcome. Additionally, LDS is an extension of growth curve modeling which has more power to detect treatment effects than traditional ANOVA approached, and it is robust to issues of nonnormality. Further, each analysis is accompanied with individual variability and fit statistics that are not available in traditional methods (Muthén & Curran, 1997).

Models were all specified and fit in Mplus version 8 (Muthén & Muthén, 2012) using full information maximum likelihood to account for missing data. Yuan-Bentler scaled chi-squared index (Y-B χ2) was used to adjust standard errors for nonnormality and nonindependence. Model fit was evaluated using multiple criteria including Y-B χ2 where nonsignificant values indicate that the model provided good fit to the data (Kline, 2011). Additionally, the comparative fit index (CFI), Tucker Lewis index (TLI), and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) with accompanying 90% confidence intervals (CIs) were used to evaluate fit (Bentler, 1990). Effects sizes were calculated by taking the standardized mean differences divided by the observed standard deviation (i.e., Cohen’s d).

To examine the effect of treatment on anger and smoking, direct effects were first examined and then followed by mediation models where condition was the predictor, posttreatment interpretation bias (hostile and benign) or trait anger was the mediator, and trait anger at 3-month follow-up or smoking was the outcome. Mediation models were examined using full maximum-likelihood estimation and bias-corrected bootstrapped CIs with 5000 resamples to provide consistent and replicable results (Preacher & Hayes, 2008).

Results

Treatment Participation, Credibility, and Expectancy

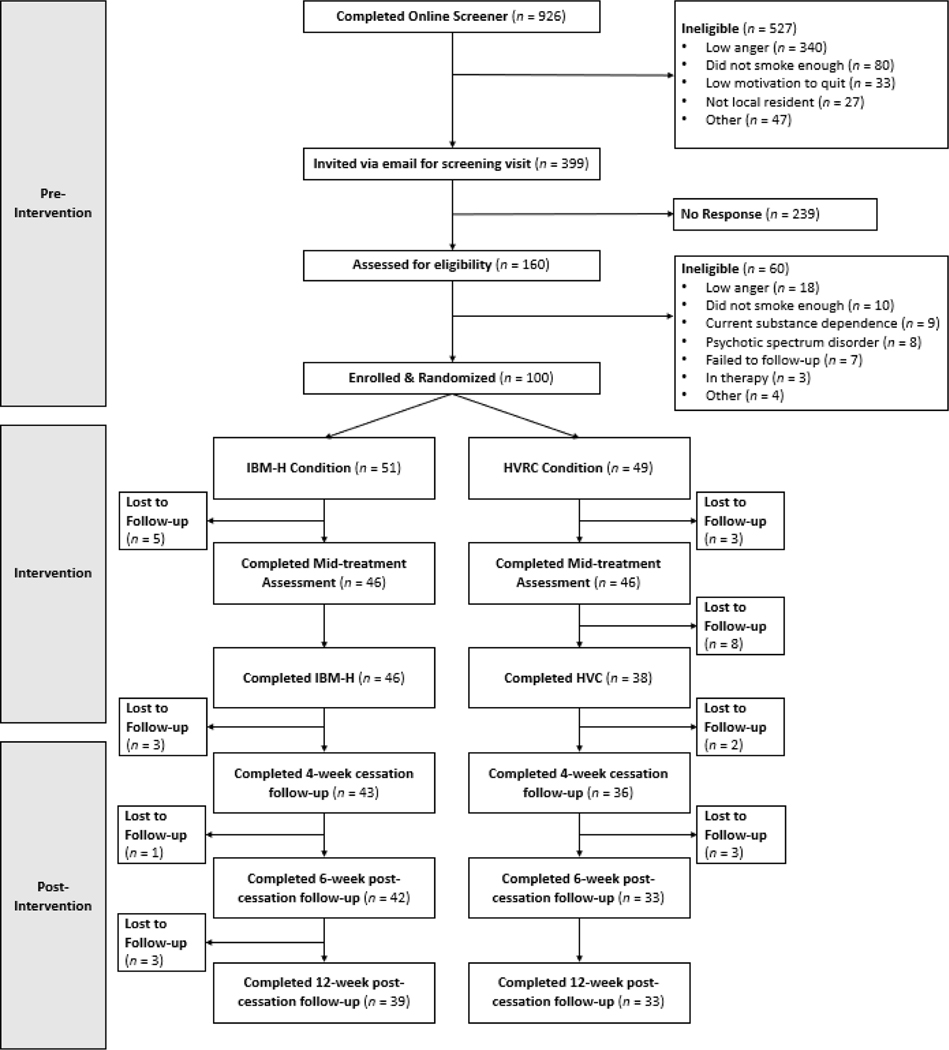

A total of 100 participants were enrolled and randomized to either IBM-H (n = 51) or HVRC (n = 49; see Figure 1). Of those randomized to IBM-H, 90.1% (n = 46) completed the midpoint and posttreatment surveys, 84.3% (n = 43) completed the four-week follow-up, 82.3% (n = 42) completed the six-week follow-up, and 76.4% (n = 39) completed the twelve-week follow-up. For those randomized to receive HVRC, 93.8% (n = 46) completed the midpoint survey, 77.5% (n = 38) completed posttreatment, 73.4% (n = 36) completed the four-week follow-up, and 67.3% (n = 33) completed the six- and twelve-week follow-up surveys. Participants in the IBM-H condition completed an average of 6.8 sessions (SD = 2.4) and the HRVC condition completed an average of 7.1 sessions (SD = 1.7). Following our intent-to-treat analytic plan, we used data from all participants in statistical analyses, regardless of their number of sessions completed.

Figure 1.

CONSORT flow diagram of the progress through the phases of the randomized control trial.

Note. IBM-H = Interpretation Bias Modification for Hostility condition; HRVC = Healthy and Relaxing Video Control condition.

CEQ ratings gathered at the end of the first session were examined. No statistically significant differences in average expectancy (F[1,88] = 0.889, p = 0.349) or perceived treatment credibility (F[1,96] = 0.960, p = 0.330) were found between the IBM-H and HRVC conditions.

Latent Difference Score Models

Parameter estimates by group for all LDS models are presented in Table 3. The LDS multigroup model for WSAP-H hostile interpretation bias demonstrated good fit (Y-B χ2 (1) = 0.96, p = 0.33, CFI = 1.00, TLI = 1.00, RMSEA < 0.01, 90% CI [0.00, 0.26]) after the inclusion of a residual correlation between posttreatment and 3-month hostile interpretation bias suggested by the modification index. Hostile interpretation bias was found to be statistically significantly different between groups at posttreatment (b = −1.07, SE = 0.19, p <.001, d = 1.21). IBM-H led to greater pre-to-posttreatment reductions (Change 1) in hostile interpretation bias than HRVC (b = 1.31, SE = 0.20, p <.001). These treatment effects were maintained, as evidenced by a statistically significant 3-month intercept (b = −.907, SE = 0.19, p <.001, d = 1.12) demonstrating between-group differences at this timepoint. However, there were no statistically significant condition-specific differences in posttreatment-to-3-month follow-up (Change 2) reductions in hostile interpretation bias (b = 0.17, SE = 0.12, p =.166), indicating that IBM-H’s significant effect on hostility took place during the active treatment phase.

Table 3.

Model Parameters for Latent Difference Score Models across Conditions (N = 100)

| Parameters | IBM (n = 51) |

HRVC (n = 49) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WSAP Hostile I nterpretation Bias | ||||

| Mean | SE | Mean | SE | |

|

| ||||

| Post Intercept | 1.54*** | 0.11 | 2.61*** | 0.15 |

| Intercept Variance | 0.19** | 0.07 | 0.28* | 0.11 |

| Change 1 | 1.70*** | 0.15 | 0.40** | 0.14 |

| Change 2 | 0.07 | 0.09 | −0.11 | 0.09 |

| WSAP Benign Interpretation Bias | ||||

| Mean | SE | Mean | SE | |

|

| ||||

| Post Intercept | 5.43*** | 0.10 | 4.61*** | 0.16 |

| Intercept Variance | 0.14* | 0.07 | 0.68*** | 0.17 |

| Change 1 | −1.57*** | 0.15 | −0.38** | 0.18 |

| Change 2 | −0.06 | 0.08 | 0.04 | 0.11 |

| Hostility | ||||

| Mean | SE | Mean | SE | |

|

| ||||

| Post Intercept | 5.99*** | 0.60 | 8.28*** | 0.64 |

| Intercept Variance | 12.62*** | 2.70 | 12.44*** | 2.24 |

| Change 1 | 1.71** | 0.53 | −0.39 | 0.50 |

| Change 2 | −0.03 | 0.42 | −1.07* | 0.53 |

Note. IBM = Interpretation Bias Modification; HRVC = Healthy and Relaxing Video Control; WSAP = Word Sentence Association Paradigm; SE = Standard error. Change 1 = Pre-to-posttreatment; Change 2 = Posttreatment to 3-month follow-up.

p <.05

p <.01

p <.001

In examining WSAP-H benign interpretation bias, the LDS model fit the data well (Y-B χ2 (1) = 0.06, p = 0.82, CFI = 1.00, TLI = 1.00, RMSEA < 0.01) after the inclusion of a residual correlation between posttreatment and 3-month benign interpretation bias. Like hostile interpretation bias, benign interpretation bias was found to be statistically significantly different between groups at posttreatment (b = 0.79, SE = 0.18, p <.001, d = 0.86). Further, treatment condition was found to be a statistically significant predictor of change in benign interpretation bias from pre-to-posttreatment (Change 1) with IBM-H leading to greater increases than HRVC (b = −1.14, SE = 0.19, p <.001). As with hostile interpretation, treatment condition was not found to be a predictor of change in benign interpretation bias from posttreatment-to-follow-up (Change 2; b = −0.10, SE = 0.14, p =.462), indicating that all condition-specific change took place during the treatment window. Treatment effects were maintained, however, as evidenced by a statistically significant between-group difference at follow-up (b = 0.69, SE = 0.18, p <.001, d = 0.76).

To further examine the effect of condition of hostile and benign interpretation bias, LDS models were fit using the SIPQ. The LDS model for SIPQ hostile interpretation bias fit the data well (Y-B χ2 (2) = 3.28, p = 0.19, CFI = 0.98, TLI = 0.94, RMSEA < 0.01). SIPQ hostile interpretation bias was found to be statistically significantly different between groups at posttreatment (b = −3.47, SE = 0.79, p <.001, d = 0.96). Treatment condition was found to be a statistically significant predictor of change in SIPQ hostile interpretation bias from pre-to-posttreatment (Change 1) with the IBM-H condition exhibiting greater improvements than HRVC (b = 4.81, SE = 0.83, p <.001). Treatment effects were maintained, as demonstrated by a statistically significant between group difference at follow-up (b = −3.26, SE = 0.86, p <.001, d = 0.77). The LDS model for SIPQ benign interpretation bias also fit the data well (Y-B χ2 (2) = 4.21, p = 0.122, CFI = 0.96, TLI = 0.89, RMSEA = 0.08). SIPQ benign interpretation bias was found to differ between groups statistically significantly at posttreatment (b = 3.71, SE = 0.92, p <.001, d = 0.83). IBM-H led to greater pre-to-posttreatment increases than HRVC (b = −3.13, SE = 0.92, p =.001). Treatment effects were maintained, as demonstrated by a statistically significant between-group difference at follow-up (b = 3.81, SE = 1.04, p <.001, d = 0.78).

The LDS model for Cook-Medley hostility demonstrated good fit to the data (Y-B χ2 (1) = 0.41, p = 0.522, CFI = 1.00, TLI = 1.00, RMSEA < 0.01). Hostility was found to differ between groups statistically significantly at posttreatment (b = −2.30, SE = 0.88, p =.009, d = 0.53). Condition was a statistically significant predictor of change from pre-to-posttreatment, with IBM-H leading to greater reductions than HRVC (b = 2.11, SE = 0.74, p =.004). However, groups did not statistically significantly differ in hostility at 3-month follow-up (b = −1.29, SE = 0.96, p =.181).

Direct effects of treatment on trait anger and depression

Analysis of the direct effect of condition on anger at posttreatment and 3-month follow-up were conducted. Condition was not found to be a statistically significant predictor of anger at posttreatment (b = −1.17, SE = 1.00, p = .245) when covarying for baseline anger (b = 0.411, SE = 0.11, p < .001), but IBM-H led to greater reductions in anger at follow-up (b = −2.18, SE = 1.09, p = .034, d = 0.38) while covarying for anger at baseline (b = 0.19, SE = 0.12, p = .118). Condition was not a statistically significant predictor of depression at posttreatment (b = −1.55, SE = 2.00, p = .439), or at follow-up (b = −3.31, SE = 2.08, p = .111).

Effect of treatment on trait anger through change in hostile and benign interpretation bias

As expected, a statistically significant mediation effect was found such that condition significantly predicted anger at 3-month follow-up through hostile interpretation bias (b = −2.78, SE = .74, 95% CI [−4.24, −1.34]). With the inclusion of the mediator (see Supplemental Figure 1), the direct effect was no longer statistically significant (b = 0.16, SE = 0.10 95% CI [−0.04, −0.36]). Similarly, benign interpretation bias at post-treatment was found to mediate the effect of condition on 3-month follow-up anger (b = −1.58, SE = .55, 95% CI −2.66, −.51]), and the direct effect was no longer statistically significant with the inclusion of this mediating path (b = 0.13, SE = 0.12 95% CI [–0.10, 0.35]; see Supplemental Figure 2).

Effects of treatment on smoking outcomes

Smoking abstinence was confirmed via self-reported abstinence and CO levels < 5ppg at 3-month follow-up; all those lost to attrition were considered non-abstinent. Condition was not predictive of smoking abstinence at 3-month follow-up (χ2[df = 1, N = 100] = 0.502, p = .479), with 19.6% (n =10) of those receiving IBM-H and 14.3% (n =7) of those receiving HRVC achieving abstinence. When abstinence was further confirmed by salivary cotinine levels at less than 10ng/ml, condition remained nonsignificant at 3-month follow-up ( χ2 [df = 1, N = 100] = 0.04, p = .947), with 9.8% (n =5) and 10.2% (n =5) of those in the IBM-H and HRCV conditions achieving abstinence, respectively. To examine the effects of treatment and other targeted variables on smoking, the direct effects of condition on abstinence, smoking frequency, and CO levels were conducted. Condition was not predictive of smoking frequency (b = −0.17, SE = .78, p = .827) or CO levels (b = −0.83, SE = 3.40, p = .807) at posttreatment when covarying for baseline levels. Condition was also not predictive of smoking frequency (b = −1.04, SE = 1.25, p = .408) at 3-month follow-up when covarying for baseline levels. Condition was predictive of CO levels at 3-month follow-up (b = 4.53, SE = 2.33, p = .044) such that HRVC led to greater reduction in CO levels than IBM-H when covarying for baseline CO levels. Given the unexpected null findings on smoking, we conducted exploratory analyses to examine if pre-treatment hostility moderated the effects on smoking. We found that baseline hostility did not moderate the effect of condition on either posttreatment or follow-up smoking frequency (ps > .34).

Changes in smoking frequency and CO levels over treatment are presented in Supplemental Figures 3 and 4. Baseline past-week daily cigarette consumption was an average of 15.03 cigarettes (IBM-H: M = 15.69, SD = 6.11; HRCV: M = 14.36, SD = 5.64). Both treatment groups significantly reduced their mean cigarette consumption by the end of treatment (IBM-H: M = 2.21, SD = 3.45; HRCV: M = 2.23, SD = 3.60). These reductions remained largely stable, rising slightly by 3-month follow-up (IBM-H: M = 3.75, SD = 5.11; HRCV: M = 4.16, SD = 5.78). Carbon monoxide (CO) levels followed a similar trajectory, falling from an average of 25.1 ppm (IBM-H: M = 25.53, SD = 13.66; HRVC: M = 24.56, SD = 10.58) to just 9.12 ppm at immediate posttreatment (IBM-H: M = 8.20, SD = 13.12; HRVC: M = 9.91, SD = 17.76) and 10.89 ppm at 3-month follow-up (IBM-H: M = 13.34, SD = 13.06; HRVC: M = 8.60, SD = 10.09). Relative to baseline, participants across both conditions reduced their self-reported consumption by an estimated 85.38% (IBM-H: 86.15%; HRVC: 84.49%) at posttreatment and 73.49% at three-month follow-up (IBM-H: 75.87%; HRVC: 70.76).

Effects of treatment on smoking outcomes through change in anger, hostility, or hostile interpretation bias

There were no statistically significant mediation effects of treatment on smoking frequency at follow-up through post-treatment anger, hostility, or hostile interpretation bias. Further, there were no significant mediation effects of treatment on CO levels at follow-up through post-treatment anger, hostility, or hostile interpretation bias. Summary of mediation analyses are presented in Supplemental Table 1.

Discussion

Consistent with our hypotheses, we found that IBM-H led to more adaptive interpretation biases. Participants in the IBM-H had fewer hostile interpretations (Cohen’s d = 1.61) and more benign interpretations (d = 1.43) at posttreatment (assessed via the WSAP-H), and these large effect sizes were maintained at three-month follow-up (hostile: d = 1.44; benign: d = 1.41). The reductions in hostile interpretation bias found in this trial are comparable to those found in prior IBM-H clinical trials, such as one study which found medium-to-large effect sizes on benign (d = 1.17) and hostile interpretations (d = 0.65) in a sample of treatment-seeking individuals with elevated anger and alcohol use disorder (Cougle et al., 2017). These condition-specific effects on hostility were further supported by our finding that participants in the IBM-H condition also had significantly lower hostile interpretation bias as assessed by the Social Information Processing Attribution Bias Questionnaire, compared to participants in the HVRC condition, both at posttreatment and three-month follow-up. Indeed, our present findings regarding IBM-H’s impact on hostile and benign interpretations are somewhat larger than those found in several prior trials with depressed individuals (Smith et al., 2018) and psychotherapy treatment-seekers (van Teffelen et al., 2021). Notably, the present study included two different tasks to reduce hostile interpretation bias, though two of these previous studies used only one task (Cougle et al., 2017; Smith et al., 2018). As IBM-H also had significantly larger effects on trait level hostility, our findings support the efficacy of IBM-H in promoting enduring reductions in hostility and demonstrated hostile interpretations, as well as to increases in more adaptive, benign interpretations.

Both the IBM-H and HRVC conditions led to significantly lower smoking frequency over the course of treatment, which persisted at three-month follow-up. These reductions in smoking (85% at posttreatment; 75% at three-month follow-up) constitute clinically significant change. Even in the absence of full abstinence, large smoking reductions have been found to be associated with positive health outcomes. In one recent meta-analysis, researchers found that moving from heavy smoking (≥15–20 cigarettes per day) to light smoking (<10) had lower risk of cardiovascular disease and lung cancer risk (Chang et al., 2021). The salutary impact of cigarette reduction should not, however, be overstated. Even light and intermittent cigarette smoking is associated with adverse health outcomes (Schane et al., 2010), and so full cessation is the most effective means of reducing smoking’s negative health outcomes.

There was no condition-specific effect of IBM-H on rates of smoking cessation, either at posttreatment or follow-up. Although to our knowledge this is the first test of interpretation bias modification on smoking cessation, our findings should be considered in the context of prior literature on CBM clinical trials for substance use. In the case of alcohol use disorder (AUD), the effects of CBM have been predominantly positive (Wiers et al., 2023). Yet CBM’s performance in the context of smoking cessation has been more mixed and modest (Boffo et al., 2019). In one recent CBM trial, Elfeddali et al. (2016) found that a web-based attentional retraining self-help exercise evinced a large effect on abstinence in heavy smokers. However, Wen et al. (2022) found that approach bias modification—whereby individuals are trained to approach smoking alternatives when faced with nicotine cravings—had no condition-specific effects on smoking cessation above those produced by active placebo. These variable findings in the context of smoking cessation could indicate different types of CBM interventions (i.e., attentional, interpretational) are differentially efficacious. Future work on CBM for smoking cessation should build on both positive trials in this area (Elfeddali et al., 2016), as well as promising outcomes in the CBM for AUD literature (e.g., Wiers et al., 2015).

We found that neither levels of trait anger nor hostility predicted better smoking outcomes. This finding is inconsistent with prior research indicating that anger can function as a psychological mechanism maintaining smoking behaviors and prompting smoking relapse. Prior work had found that problematic anger was correlated with past-year daily smoking, heavy smoking, and higher likelihood of developing cigarette dependence (Cougle et al., 2013). Further, higher trait anger and difficulties with the outward expression of anger were both uniquely associated with more severe withdrawal symptoms during smoking cessation attempts (Cougle et al., 2014). More recently, researchers found that heavy smokers reported greater levels of trait-anger compared to both non-smokers and moderate smokers (Muscatello et al., 2017). It is possible that an intervention that specifically targeted anger (e.g., anger-management training; Yalcin et al., 2014) would have evinced a condition-specific effect on not just anger but also successful smoking cessation. Likewise, it is possible that our current approach is of particular benefit not so much to smokers who indicate high anger, but to smokers with high hostility or hostile interpretation bias. It is noteworthy that we found pre-treatment hostility did not moderate the effects of treatment in the current study.

The present study is subject to several limitations. First, this study had only a three-month follow-up period, which may have obscured treatment-specific effects that occurred at later periods. Second, we had strict exclusion criteria that limit our ability to generalize these findings to those with either comorbid substance use, or use of non-cigarette tobacco products. Second, our placebo condition may have included active treatment components (i.e., relaxation training; mindfulness training) that may obscure the true extent of IBM-H’s effects on smoking cessation. Rather than pointing to a deficiency in IBM-H, this study could indicate that healthy lifestyle changes may engender subsequent reductions in other unhealthy behaviors. However, without data on changes in healthy habits or mindfulness across both treatment conditions, this point remains speculative. Lastly, our sample was predominantly white, and future research might examine the efficacy of IBM-H and HRVC in more diverse samples.

Overall, the present study suggests that web-based IBM-H, was efficacious in reducing hostile interpretation bias, hostility, and trait anger among smokers with high trait anger. Moreover, the combined IBM-H and nicotine replacement therapy was effective in reducing smoking frequency. However, this treatment did not outperform on smoking outcomes over the combined HRVC and nicotine replacement condition. Our study highlights the importance of considering the role of mental health in smoking cessation interventions, and future work could examine the impact of more sustained doses of IBM-H on smoking cessation. Further, the computerized nature of both considered interventions highlights the potential of digital interventions to increase treatment access. For smokers with elevated anger who lack access to in-person treatment options or who may prefer the convenience and privacy of a digital intervention, either IBM-H or HRVC, when paired with nicotine replacement therapy, may be an efficacious treatment option. Additionally, a digital therapeutic could be tailored to individual smokers based on their unique characteristics, including their level of hostility and trait anger.

Supplementary Material

Table 2.

Outcomes at condition at Baseline, Post-Treatment, and 3-Month Follow-Up.

| Measure | Baseline (N = 100) |

Post-Treatment (N = 84) |

3Mos Follow-up (N = 72) |

Cohen’s d |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | Pre-to-post | Pre-to-follow-up | |

|

| ||||||||

| IBM-H | (n = 51) | (n = 46) | (n = 39) | |||||

| Daily Cigs | 15.69 | 6.17 | 2.17 | 3.41 | 3.79 | 5.20 | 2.00*** | 1.77*** |

| CO (ppm) | 25.53 | 13.71 | 8.20 | 13.37 | 13.37 | 13.24 | 1.34*** | 0.94*** |

| STAXI | 25.57 | 4.80 | 19.26 | 4.78 | 17.00 | 4.71 | 1.24*** | 1.04*** |

| BDI | 12.67 | 10.00 | 10.35 | 11.73 | 7.31 | 9.95 | 0.20 | 0.46** |

| SIPQ-H | 9.96 | 4.34 | 4.20 | 3.71 | 3.62 | 4.02 | 1.28*** | 1.36*** |

| SIPQ-B | 12.43 | 4.15 | 17.24 | 4.45 | 17.46 | 5.04 | −0.92*** | −1.14*** |

| CMHS | 7.71 | 4.67 | 6.07 | 4.31 | 6.03 | 4.68 | 0.47** | 0.48** |

| WSAP-H | 3.24 | 0.93 | 1.54 | 0.79 | 1.58 | 0.87 | 1.61*** | 1.44*** |

| WSAP-B | 3.87 | 0.98 | 5.43 | 0.71 | 5.41 | 0.70 | −1.43*** | −1.41*** |

| HRVC | (n = 49) | (n = 38) | (n = 33) | |||||

| Daily Cigs | 14.40 | 5.71 | 2.23 | 3.65 | 4.21 | 5.93 | 2.20*** | 1.71*** |

| CO (ppm) | 24.65 | 10.61 | 9.92 | 18.01 | 8.60 | 10.24 | 0.89*** | 1.47*** |

| STAXI | 24.29 | 3.79 | 19.53 | 4.95 | 18.77 | 4.62 | 0.87*** | 1.01*** |

| BDI | 10.31 | 8.71 | 10.87 | 8.99 | 9.66 | 9.96 | 0.00 | 0.07 |

| SIPQ-H | 8.49 | 4.06 | 7.76 | 3.73 | 6.66 | 3.81 | 0.34* | 0.54** |

| SIPQ-B | 11.85 | 4.25 | 13.63 | 4.21 | 13.74 | 4.37 | −0.55** | −0.50** |

| CMHS | 7.94 | 4.26 | 8.29 | 4.17 | 7.17 | 4.25 | −0.11 | −0.20 |

| WSAP-H | 2.97 | 0.70 | 2.61 | 0.97 | 2.51 | 0.81 | 0.54** | 0.71*** |

| WSAP-B | 4.22 | 0.91 | 4.71 | 0.97 | 4.78 | 0.97 | −0.57** | 0.60** |

Note: Daily Cigs = self-reported number of cigarettes smoked per day, over the prior seven days; CO (ppm) = carbon monoxide breath parts per million; STAXI = State-Trait Anger Expression Inventory 2 – Trait Anger Scale; BDI = Beck Depression Inventory-II; SIP-ABQ = Social Information Processing Attribution Bias Questionnaire; CMHS = Cooke-Medley Hostility Scale; WSAP – H & -B = The Word Sentence Association Paradigm – Hostility & Benign, respectively; IBM-H = Interpretation Bias Modification for Hostility; HRVC = Healthy and Relaxing Video Control

p <.05

p <.01

p <.001

Highlights.

Tested interpretation bias modification for hostility (IBM-H) in smokers with high anger

IBM-H led to lower hostile interpretation bias at post and follow-up

IBM-H led to lower hostility at post and lower trait anger at follow-up

IBM-H and control conditions had reductions in smoking but did not differ in quit rates

Funding:

This research was supported by grant R34DA035944 awarded from the National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA. Research in this publication was also supported by the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (NIMHD) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) to the University of Houston under Award Number U54MD015946. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Declarations of Interest: None.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Akbari M, Hasani J, & Seydavi M. (2020). Negative affect among daily smokers: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders, 274, 553–567. 10.1016/j.jad.2020.05.063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- al’ Absi M, Carr SB, & Bongard S. (2007). Anger and psychobiological changes during smoking abstinence and in response to acute stress: Prediction of smoking relapse. International Journal of Psychophysiology, 66(2), 109–115. 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2007.03.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babb S, Malarcher A, & Schaur G. (2017). Quitting Smoking Among Adults—United States, 2000–2015. MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 65. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6552a1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barefoot JC, Dodge KA, Peterson BL, Dahlstrom WG, & Williams RB (1989). The Cook-Medley hostility scale: Item content and ability to predict survival. Psychosomatic Medicine, 51(1), 46–57. 10.1097/00006842-198901000-00005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer RA, Ball R, & Ranieri WF (1996). Comparison of Beck Depression Inventories-IA and-II in Psychiatric Outpatients. Journal of Personality Assessment, 67(3), 588–597. 10.1207/s15327752jpa6703_13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benson L, Ra CK, Hébert ET, Kendzor DE, Oliver JA, Frank-Pearce SG, Neil JM, & Businelle MS (2022). Quit Stage and Intervention Type Differences in the Momentary Within-Person Association Between Negative Affect and Smoking Urges. Frontiers in Digital Health, 4, 864003. 10.3389/fdgth.2022.864003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentler PM (1990). Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychological Bulletin, 107, 238–246. 10.1037/0033-2909.107.2.238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein MH, Colby SM, Bidwell LC, Kahler CW, & Leventha AM. (2014). Hostility and Cigarette Use: A Comparison Between Smokers and Nonsmokers in a Matched Sample of Adolescents. Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 16(8), 1085–1093. 10.1093/ntr/ntu033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boffo M, Zerhouni O, Gronau QF, van Beek RJJ, Nikolaou K, Marsman M, & Wiers RW (2019). Cognitive Bias Modification for Behavior Change in Alcohol and Smoking Addiction: Bayesian Meta-Analysis of Individual Participant Data. Neuropsychology Review, 29(1), 52–78. 10.1007/s11065-018-9386-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browne MW, & Cudeck R. (1992). Alternative Ways of Assessing Model Fit. Sociological Methods & Research, 21(2), 230–258. [Google Scholar]

- Carmody TP, Vieten C, & Astin JA (2007). Negative Affect, Emotional Acceptance, and Smoking Cessation. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs, 39(4), 499–508. 10.1080/02791072.2007.10399889 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang JT, Anic GM, Rostron BL, Tanwar M, & Chang CM (2021). Cigarette Smoking Reduction and Health Risks: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 23(4), 635–642. 10.1093/ntr/ntaa156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coccaro EF., Noblett KL., & McCloskey MS. (2009). Attributional and emotional responses to socially ambiguous cues: Validation of a new assessment of social/emotional information processing in healthy adults and impulsive aggressive patients. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 43(10), 915–925. 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2009.01.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornelius ME, Loretan C, & Wang T. (2022). Tobacco Product Use Among Adults—United States, 2020. MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 71. 10.15585/mmwr.mm7111a1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cougle JR, Hawkins KA, Macatee RJ, Zvolensky MJ, & Sarawgi S. (2014). Multiple Facets of Problematic Anger Among Regular Smokers: Exploring Associations With Smoking Motives and Cessation Difficulties. Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 16(6), 881–885. 10.1093/ntr/ntu011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cougle JR, Summers BJ, Allan NP, Dillon KH, Smith HL, Okey SA, & Harvey AM (2017). Hostile interpretation training for individuals with alcohol use disorder and elevated trait anger: A controlled trial of a web-based intervention. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 99, 57–66. 10.1016/j.brat.2017.09.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cougle JR, Zvolensky MJ, & Hawkins KA (2013). Delineating a Relationship Between Problematic Anger and Cigarette Smoking: A Population-Based Study. Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 15(1), 297–301. 10.1093/ntr/nts122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creamer MR, Wang T, & Babb S. (2019). Tobacco Product Use and Cessation Indicators Among Adults—United States, 2018. MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 68. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6845a2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curran PJ, West SG, & Finch JF (1996). The robustness of test statistics to nonnormality and specification error in confirmatory factor analysis. Psychological Methods, 1, 16–29. 10.1037/1082-989X.1.1.16 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dhavan P, Bassi S, Stigler Melissa. H., Arora M, Gupta VK, Perry Cheryl. L., Ramakrishnan L, & Reddy KS (2011). Using Salivary Cotinine to Validate Self-Reports of Tobacco Use by Indian Youth Living in Low-Income Neighborhoods. Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention, 12(10), 2551–2554. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dillon KH, Allan NP, Cougle JR, & Fincham FD (2016). Measuring Hostile Interpretation Bias: The WSAP-Hostility Scale. Assessment, 23(6), 707–719. 10.1177/1073191115599052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dillon KH, Medenblik AM, Mosher TM, Elbogen EB, Morland LA, & Beckham JC (2020). Using Interpretation Bias Modification to Reduce Anger among Veterans with Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: A Pilot Study. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 33(5), 857–863. 10.1002/jts.22525 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eiden RD, Leonard KE, Colder CR, Homish GG, Schuetze P, Gray TR, & Huestis MA (2011). Anger, Hostility, and Aggression as Predictors of Persistent Smoking During Pregnancy. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 72(6), 926–932. 10.15288/jsad.2011.72.926 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elfeddali I, de Vries H, Bolman C, Pronk T, & Wiers RW (2016). A randomized controlled trial of Web-based Attentional Bias Modification to help smokers quit. Health Psychology: Official Journal of the Division of Health Psychology, American Psychological Association, 35(8), 870–880. 10.1037/hea0000346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, & Gibbon M. (2004). The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (SCID-I) and the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis II Disorders (SCID-II). In Comprehensive handbook of psychological assessment, Vol. 2: Personality assessment (pp. 134–143). John Wiley & Sons, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- García-Rodríguez O, Secades-Villa R, Flórez-Salamanca L, Okuda M, Liu S-M, & Blanco C. (2013). Probability and predictors of relapse to smoking: Results of the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC). Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 132(3), 479–485. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.03.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garey L, Olofsson H, Garza T, Shepherd JM, Smit T, & Zvolensky MJ (2020). The Role of Anxiety in Smoking Onset, Severity, and Cessation-Related Outcomes: A Review of Recent Literature. Current Psychiatry Reports, 22(8), 38. 10.1007/s11920-020-01160-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin RD, Wall MM, Gbedemah M, Hu M-C, Weinberger AH, Galea S, Zvolensky MJ, Hangley E, & Hasin DS (2018). Trends in cigarette consumption and time to first cigarette on awakening from 2002 to 2015 in the USA: New insights into the ongoing tobacco epidemic. Tobacco Control, 27(4), 379–384. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2016-053601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorenstein EE, Tager FA, Shapiro PA, Monk C, & Sloan RP (2007). Cognitive-Behavior Therapy for Reduction of Persistent Anger. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 14(2), 168–184. 10.1016/j.cbpra.2006.07.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jarvis MJ, Tunstall-Pedoe H, Feyerabend C, Vesey C, & Saloojee Y. (1987). Comparison of tests used to distinguish smokers from nonsmokers. American Journal of Public Health, 77(11), 1435–1438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahler CW, Strong DR, Niaura R, & Brown RA (2004). Hostility in smokers with past major depressive disorder: Relation to smoking patterns, reasons for quitting, and cessation outcomes. Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 6(5), 809–818. 10.1080/1462220042000282546 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kline RB (2011). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling, 3rd ed (pp. xvi, 427). Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lipari R, & Van Horn S. (2013). Smoking and Mental Illness Among Adults in the United States. PubMed. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28459516/ [PubMed]

- Lipkus IM, Barefoot JC, Williams RB, & Siegler IC (1994). Personality measures as predictors of smoking initiation and cessation in the UNC Alumni Heart Study. Health Psychology: Official Journal of the Division of Health Psychology, American Psychological Association, 13(2), 149–155. 10.1037//0278-6133.13.2.149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mara CA, Cribbie RA, Flora DB, LaBrish C, Mills L, & Fiksenbaum L. (2012). An improved model for evaluating change in randomized pretest, posttest, follow-up designs. Methodology: European Journal of Research Methods for the Behavioral and Social Sciences, 8, 97–103. 10.1027/1614-2241/a000041 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Morar T, & Robertson L. (2022). Smoking cessation among people with mental illness: A South African perspective. South African Family Practice: Official Journal of the South African Academy of Family Practice/Primary Care, 64(1), e1–e9. 10.4102/safp.v64i1.5489 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mun EY, von Eye A, & White HR (2009). An SEM Approach for the Evaluation of Intervention Effects Using Pre-Post-Post Designs. Structural Equation Modeling : A Multidisciplinary Journal, 16(2), 315–337. 10.1080/10705510902751358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muscatello MRA, Scimeca G, Lorusso S, Battaglia F, Pandolfo G, Zoccali RA, & Bruno A. (2017). Anger, Smoking Behavior, and the Mediator Effects of Gender: An Investigation of Heavy and Moderate Smokers. Substance Use & Misuse, 52(5), 587–593. 10.1080/10826084.2016.1245343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén BO, & Curran PJ (1997). General longitudinal modeling of individual differences in experimental designs: A latent variable framework for analysis and power estimation. Psychological Methods, 2, 371–402. 10.1037/1082-989X.2.4.371 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, & Muthén BO (2012). Mplus: Statistical analysis with latent variables; user’s guide;[version 7]. Muthén et Muthén. [Google Scholar]

- Patterson F, Kerrin K, Wileyto EP, & Lerman C. (2008). Increase in anger symptoms after smoking cessation predicts relapse. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 95(1–2), 173–176. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.01.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, & Hayes AF (2008). Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods, 40(3), 879–891. 10.3758/BRM.40.3.879 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson JD, Li L, Chen M, Lerman C, Tyndale RF, Schnoll RA, Hawk LW Jr., George TP, Benowitz NL, & Cinciripini PM (2019). Evaluating the temporal relationships between withdrawal symptoms and smoking relapse. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 33(2), 105. 10.1037/adb0000434 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson SM, Sobell LC, Sobell MB, & Leo GI (2014). Reliability of the Timeline Followback for cocaine, cannabis, and cigarette use. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors: Journal of the Society of Psychologists in Addictive Behaviors, 28(1), 154–162. 10.1037/a0030992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schane RE, Ling PM, & Glantz SA (2010). Health Effects of Light and Intermittent Smoking: A Review. Circulation, 121(13), 1518. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.904235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shrestha SS, Ghimire R, Wang X, Trivers KF, Homa DM, & Armour BS (2022). Cost of Cigarette Smoking‒Attributable Productivity Losses, U.S., 2018. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 10.1016/j.amepre.2022.04.032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith HL, Dillon KH, & Cougle JR (2018). Modification of Hostile Interpretation Bias in Depression: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Behavior Therapy, 49(2), 198–211. 10.1016/j.beth.2017.08.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smits JAJ, Zvolensky MJ, Rosenfield D, Brown RA, Otto MW, Dutcher CD, Papini S, Freeman SZ, DiVita A, Perrone A, & Garey L. (2021). Community-based smoking cessation treatment for adults with high anxiety sensitivity: A randomized clinical trial. Addiction, 116(11), 3188–3197. 10.1111/add.15586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spielberger CD, Sydeman SJ, Owen AE, & Marsh BJ (1999). Measuring anxiety and anger with the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) and the State-Trait Anger Expression Inventory (STAXI). In The use of psychological testing for treatment planning and outcomes assessment, 2nd ed (pp. 993–1021). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Summers BJ, & Cougle JR (2016). Modifying interpretation biases in body dysmorphic disorder: Evaluation of a brief computerized treatment. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 87, 117–127. 10.1016/j.brat.2016.09.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker LR, & Lewis C. (1973). A reliability coefficient for maximum likelihood factor analysis. Psychometrika, 38(1), 1–10. 10.1007/BF02291170 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- van Teffelen MW, Lobbestael J, Voncken MJ, Cougle JR, & Peeters F. (2021). Interpretation bias modification for hostility: A randomized clinical trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 89(5), 421–434. 10.1037/ccp0000651 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y-P, & Gorenstein C. (2013). Psychometric properties of the Beck Depression Inventory-II: A comprehensive review. Brazilian Journal of Psychiatry, 35, 416–431. 10.1590/1516-4446-2012-1048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss JW, Mouttapa M, Cen S, Johnson CA, & Unger J. (2011). Longitudinal effects of hostility, depression, and bullying on adolescent smoking initiation. Journal of Adolescent Health, 48(6), 591–596. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.09.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen S, Larsen H, & Wiers RW (2022). A Pilot Study on Approach Bias Modification in Smoking Cessation: Activating Personalized Alternative Activities for Smoking in the Context of Increased Craving. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 29(4), 480–493. 10.1007/s12529-021-10033-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whalen CK, Jamner LD, Henker B, & Delfino RJ (2001). Smoking and moods in adolescents with depressive and aggressive dispositions: Evidence from surveys and electronic diaries. Health Psychology, 20(2), 99–111. 10.1037/0278-6133.20.2.99 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whiteman MC, Fowkes FGR, Deary IJ, & Lee AJ (1997). Hostility, cigarette smoking and alcohol consumption in the general population. Social Science & Medicine, 44(8), 1089–1096. 10.1016/S0277-9536(96)00236-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiers CE, Stelzel C, Gladwin TE, Park SQ, Pawelczack S, Gawron CK, Stuke H, Heinz A, Wiers RW, Rinck M, Lindenmeyer J, Walter H, & Bermpohl F. (2015). Effects of Cognitive Bias Modification Training on Neural Alcohol Cue Reactivity in Alcohol Dependence. American Journal of Psychiatry, 172(4), 335–343. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2014.13111495 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiers RW, Pan T, van Dessel P, Rinck M, & Lindenmeyer J. (2023). Approach-Bias Retraining and Other Training Interventions as Add-On in the Treatment of AUD Patients (pp. 1–47). Springer. 10.1007/7854_2023_421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkowski BM, & Robinson MD (2008). The Cognitive Basis of Trait Anger and Reactive Aggression: An Integrative Analysis. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 12(1), 3–21. 10.1177/1088868307309874 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilver NL, & Cougle JR (2019). An Internet-based controlled trial of interpretation bias modification versus progressive muscle relaxation for body dysmorphic disorder. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 87(3), 257–269. 10.1037/ccp0000372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu X, Shrestha SS, Trivers KF, Neff L, Armour BS, & King BA (2021). U.S. healthcare spending attributable to cigarette smoking in 2014. Preventive Medicine, 150, 106529. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2021.106529 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yalcin BM, Unal M, Pirdal H, & Karahan TF (2014). Effects of an Anger Management and Stress Control Program on Smoking Cessation: A Randomized Controlled Trial. The Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine, 27(5), 645–660. 10.3122/jabfm.2014.05.140083 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziedonis D, Hitsman B, Beckham JC, Zvolensky M, Adler LE, Audrain-McGovern J, Breslau N, Brown RA, George TP, Williams J, Calhoun PS, & Riley WT (2008). Tobacco use and cessation in psychiatric disorders: National Institute of Mental Health report. Nicotine & Tobacco Research: Official Journal of the Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco, 10(12), 1691–1715. 10.1080/14622200802443569 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.