Abstract

Our previous studies have shown that isolated cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL), B-cell, and T-helper epitopes, for which we coined the term minigenes, can be effective vaccines; when expressed from recombinant vaccinia viruses, these short immunogenic sequences confer protection against a variety of viruses and bacteria. In addition, we have previously demonstrated the utility of DNA immunization using plasmids encoding full-length viral proteins. Here we combine the two approaches and evaluate the effectiveness of minigenes in DNA immunization. We find that DNA immunization with isolated minigenes primes virus-specific memory CTL responses which, 4 days following virus challenge, appear similar in magnitude to those induced by vaccines known to be protective. Surprisingly, this vigorous CTL response fails to confer protection against a normally lethal virus challenge, although the CTL appear fully functional because, along with their high lytic activity, they are similar in affinity and cytokine secretion to CTL induced by virus infection. However this DNA immunization with isolated minigenes results in a low CTL precursor frequency; only 1 in ∼40,000 T cells is epitope specific. In contrast, a plasmid encoding the same minigene sequences covalently attached to the cellular protein ubiquitin induces protective immunity and a sixfold-higher frequency of CTL precursors. Thus, we show that the most commonly employed criterion to evaluate CTL responses—the presence of lytic activity following secondary stimulation—does not invariably correlate with protection; instead, the better correlate of protection is the CTL precursor frequency. Recent observations indicate that certain effector functions are active in memory CTL and do not require prolonged stimulation. We suggest that these early effector functions of CTL, immediately following infection, are critical in controlling virus dissemination and in determining the outcome of the infection. Finally, we show that improved performance of the ubiquitinated minigenes most probably requires polyubiquitination of the fusion protein, suggesting that the enhancement results from more effective delivery of the minigene to the proteasome.

One goal of vaccine development is the production of a multivalent vaccine which could confer immunity against a variety of microbes. Simultaneous administration of conventional vaccines is sometimes used to achieve this goal (for example, measles, mumps, and rubella [MMR] vaccine), but this approach carries with it the risk of microbial competition, where one component replicates more efficiently than another, potentially diminishing the immunogenicity of the latter. Many groups have approached this issue by combining multiple antigens in a single recombinant viral vector; however, such vectors are limited in their capacity for foreign sequences, and we reasoned that their effective capacity could be increased by eliminating the nonimmunogenic foreign protein backbones and cloning only the very short (9- to 11-amino-acid) immunogenic foreign epitopes into the recombinant virus. We introduced the term minigene to describe such isolated epitope sequences, and we demonstrated that they could function both in isolation (1, 36, 63) and when linked to other epitopes in a string-of-beads vaccine (2, 64). These general findings have been confirmed and extended by a number of groups (13, 24, 52, 61).

In this report we evaluate the utility of minigenes in DNA immunization. DNA immunization is a relatively new mode of vaccination in which the inoculated plasmid DNA enters cells and the encoded proteins are expressed therein, thus ensuring access of the antigen to the major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I antigen presentation pathway. Furthermore, protein released from transfected cells can interact with B lymphocytes, inducing antibodies, and can be taken up by specialized antigen-presenting cells (APCs), allowing presentation by MHC class II. Thus, DNA immunization should—and does—induce both arms of the immune response (20, 51, 55). DNA vaccines should be safer than live vaccines for administration to pregnant or immunocompromised individuals and, unlike conventional vaccines, may be effective in neonates (6, 27, 41, 44, 60). These and other potential benefits of DNA immunization are reviewed elsewhere (15, 22, 26). We (67–69) and others (43, 70) have shown that DNA immunization is effective in protecting against lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus (LCMV) infection of its natural host, the mouse. In our vaccine studies we have made extensive use of LCMV, which is the prototype of the arenavirus family and is a bisegmented single-stranded RNA virus. Cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTL) are critical both to the control of LCMV infection and to effective vaccine-induced protective immunity.

We report here the following findings. First, minigene sequences which were protective in recombinant vaccinia viruses do not protect against normally lethal LCMV challenge when administered by DNA vaccine. Second, embedding the minigene cassette in an immunogenic protein fails to overcome this defect, while covalent attachment to ubiquitin greatly enhances the protective efficacy of the minigenes. Third, in vivo restimulation of all minigene-immunized mice results in readily detectable levels of antiviral CTL. Thus, in most of the minigene-immunized mice there is a discordance between the presence of CTL at 4 days postchallenge and antiviral protection. This is true whether the minigenes are administered intramuscularly (i.m.) or by gene gun. Fourth, these CTL are of similar affinity to those induced by virus infection or by DNA immunization with full-length protein, and fifth, the cytokine profiles following LCMV challenge appear grossly similar with all the vaccines used. Sixth, we identify the defect in minigene-immunized mice which presumably is responsible for failure to protect; the CTL precursor frequency is ∼6-fold lower in minigene-immunized mice than in mice immunized with the plasmid encoding a ubiquitinated product. Finally, we demonstrate that the ubiquitinated minigenes are processed via the proteasome, since a mutation preventing polyubiquitination completely aborts antigen presentation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell lines and viruses.

MC57 (H-2b) and BALB C17 (H-2d) cell lines are maintained in RPMI medium (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.), and Vero 76 cells (ATCC CRL-1587) are maintained in medium 199 (Gibco-BRL, Bethesda, Md.) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS), l-glutamine, and penicillin-streptomycin. The virus used was LCMV (Armstrong strain).

Mouse strains.

Mouse strains (BALB/c [H-2d] and C57BL/6 [H-2b]) were obtained from the breeding colony at the Scripps Research Institute, and mice were used at the ages of 6 to 16 weeks.

Virus titration.

LCMV titration was performed on Vero 76 cells plated at a density of 6.6 × 105 per 6-well plate, 24 h prior to titration. At the time of titration, 10-fold dilutions were made in 199 medium (Gibco-BRL)–10% FCS and were applied to the indicator cells. Following adsorption and infection for 1 h at 37°C in 5% CO2, the inoculum was withdrawn and replaced with an overlay of 0.5% sterile ME agarose (FMC Bioproducts, Rockland, Maine)–1× complete 199. Four days later, the monolayer was fixed with 25% formaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline, the agarose plug was removed, and the monolayer was stained with 0.1% crystal violet–20% ethanol in phosphate-buffered saline.

Construction of the recombinant plasmids used in the DNA immunization studies.

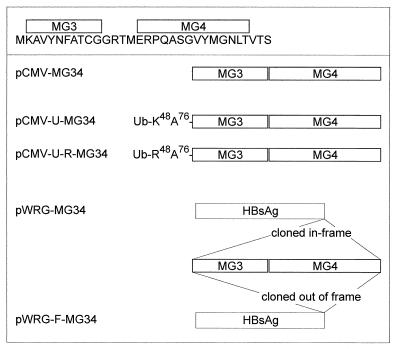

Figure 1 shows the sequences expressed by the minigenes and a schematic representation of the plasmids used in these experiments. The minigenes, designated MG3 and MG4, are derived from the LCMV glycoprotein and nucleoprotein (NP) and are presented by Db and Ld, respectively (62); when expressed from a recombinant vaccinia virus, the tandem epitope cassette MG34 protects 90 to 100% of BALB and C57BL/6 mice against a normally lethal LCMV challenge (64). Constructs used for i.m. immunization were based on pCMV (Clontech, Palo Alto, Calif.), and those used for gene gun immunization were based on the similar vector pCMV/intron A (7); in both cases, gene expression is driven by the immediate-early promoter of human cytomegalovirus (19). The MG34 cassette was either (i) cloned into the basic vector, generating pCMV-MG34, from which the minigenes are expressed as a 32-amino-acid oligopeptide; (ii) fused to ubiquitin-A76, which improves entry into the proteasome degradation pathway and thus enhances presentation via MHC class I (4, 48)—generating pCMV-U-MG34; (iii) fused to ubiquitin in which the lysine 48 (K48) residue, important to ubiquitin function, was changed to arginine (R48), generating pCMV-U-R-MG34; or cloned into a vector, pWRG, which expresses full-length hepatitis B virus surface antigen (HBsAg). In this case, the MG34 cassette was inserted at the C terminus of the HBsAg sequence either (iv) in frame (pWRG-MG34) or (v) out of frame, generating a frameshift as a negative control (pWRG-F-MG34). In addition, in some experiments a plasmid encoding ubiquitin alone (pCMV-U; not shown in Fig. 1) was used as a control. All translational initiation codons lay in favorable Kozak consensus sequences (37, 38). All DNA sequences were confirmed by using the dideoxy chain termination method with double-stranded template DNA and Sequenase version 2.0 (U.S. Biochemical Corporation, Cleveland, Ohio), and expression from these plasmids was confirmed in tissue culture by transient expression assays.

FIG. 1.

Minigenes and plasmid constructs used in this study. The sequences encoded by MG3 and MG4 are shown, along with diagrams of five of the plasmids used. U and Ub, ubiquitin; F, frameshift.

Protocol for i.m. DNA immunization.

BALB/c (H-2d) and C57BL/6 (H-2b) mice were immunized i.m. three times, at 14-day intervals, with 100 μg of plasmid. As a positive control for immunity, mice were immunized intraperitoneally (i.p.) with a sublethal dose of LCMV (2 × 105 PFU). Purification of DNA was carried out by standard techniques with a Nucleobond kit, and all DNA was treated with an endotoxin removal buffer (40% ethanol–5% acetic acid). DNA was dissolved in 1 N saline, at a concentration of 1 mg/ml, and 50 μl (50 μg) was injected into each anterior tibial muscle with a 28-gauge needle.

Protocol for gene gun DNA immunization.

The preparation and immunization techniques for gene gun-mediated immunization have been described previously (17, 21). In brief, 80 μg of plasmid DNA was added to a microcentrifuge tube containing 40 mg of 0.9-μm-diameter gold beads suspended in 200 μl of 50 mM spermidine. While the tube was gently vortexed, 400 μl of 2.5 M CaCl2 was added to precipitate the DNA onto the beads, and the tube was allowed to stand for 10 min to complete the precipitation. The DNA-coated beads (2 μg of DNA per mg of gold) were pelleted by a 10-s spin, and the supernatants were removed. The gold-DNA pellets were washed three times by vortexing in 1 ml of ethanol and microcentrifuged for 10 s, and supernatants were removed. The gold-DNA beads were transferred to a 15-ml culture tube and resuspended in 5.7 ml of ethanol to give 7 mg of gold-DNA per ml of ethanol. Sonication for 10 s in a bath sonicator generated a uniform gold suspension. By using a syringe attached by an adapter, this suspension was drawn into a 30-in. length of Tefzel tubing, with 1 ml of suspension (7 mg of gold-DNA) filling 7 in. of tubing, yielding 1 mg of gold-DNA per in. of tubing. The tubing was then transferred into a tube turner. After the gold beads were allowed to settle, the ethanol was slowly drawn off and the turner was rotated for 30 s, smearing the gold-DNA around the inside of the tubing. The residual ethanol was removed by passing nitrogen through the tubing for 3 min. The tubing was cut into 1/2-in.-long tubes (equal to one immunization dose), and the tubes were loaded into an Accell gene delivery device (gene gun). Six- to eight-week-old female BALB/c mice were anesthetized with ketamine and xylazine by i.p. injection, and their abdomens were clipped. At adjacent sites of each abdomen, two doses of gold-DNA particles were delivered by a helium blast at a pressure of 400 lb/in2. Each site received 1 μg of DNA on 1/2 mg of gold.

Multiprobe RNase protection assay.

The RNase protection assay was performed as previously described (28). For the synthesis of the radiolabeled antisense RNA probe set, the final reaction mixture (10 μl) contained 60 μCi of [α-32P]UTP (3,000 Ci/mmol; Amersham), UTP (73 pmol), GTP, ATP, and CTP (2.5 mmol of each), dithiothreitol (100 nmol), transcription buffer (1×), RNasin (10 U), T7 polymerase (10 U) (all from Promega), and an equimolar pool of EcoRI-linearized templates (70 ng total). After 1 h at 37°C, the mixture was treated with RQ-1 DNase (2 U; Promega) for 30 min at 37°C and the probe was purified by extraction with phenol-chloroform and precipitated with ethanol. Dried probe was then dissolved (2.2 × 105 cpm/μl) in hybridization buffer (HB), consisting of 80% formamide, 0.4 M NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, and 40 mM piperazine-N,N′-bis(2-ethanesulfonic acid) (PIPES) (pH 6.7), and 2 μl was added to target RNA dissolved in 8 μl of HB. The samples were overlaid with mineral oil, heated at 90°C for 1 min, and then incubated at 56°C for 12 to 16 h. Single-stranded RNA was digested by addition of a mixture of RNase A (0.2 mg/ml) and RNase T1 (600 U/ml; Bethesda Research Laboratories, Bethesda, Md.) in 10 mM Tris–300 mM NaCl–5 mM EDTA (pH 7.5). Following incubation for 60 min at 30°C, 18 μl of a mixture containing proteinase K (0.5 mg/ml; Beckman, Fullerton, Calif.), sodium dodecyl sulfate (3.5%), and yeast tRNA (100 μg/ml; Sigma) was added, and the samples were incubated for a further 30 min at 37°C. The RNA duplexes were isolated by extraction and precipitation as described above, dissolved in 80% formamide and dyes, and electrophoresed in a standard 6% acrylamide–7 M urea–0.5% Tris-borate-EDTA sequencing gel. Dried gels were exposed to XAR film (Kodak, Rochester, N.Y.) with intensifying screens at −70°C.

Induction of virus-specific CTL.

CTL activity following LCMV infection of naïve mice peaks at 7 to 9 days postinfection (p.i.) and declines thereafter. CTL activity is difficult to detect at day 4 p.i. in a nonimmune mouse but is readily detectable at this time point in an LCMV-immune animal, in which the presence of memory cells allows an accelerated response to viral challenge. We exploited this phenomenon to determine if CTL have been induced by inoculation of each plasmid. Thus, 6 weeks postimmunization, mice which had received the various DNAs (or appropriate control mice) were infected with LCMV i.p., and they were sacrificed 4 days later. Their spleens were taken, and the presence of anti-LCMV CTL activity was determined by an in vitro cytotoxicity assay.

In vitro cytotoxicity assays.

These assays were carried out as previously described (65). Effector cells were splenocytes taken (i) 7 days after LCMV infection of naïve mice (as a positive control) or (ii) 4 days p.i. from mice immunized 6 weeks previously with LCMV (positive control) or with a plasmid DNA. Target cells were transfected with the different plasmids as previously described (48) or were infected with LCMV; all were labeled with 51Cr, washed, and incubated in triplicate for 5 h with effector cells at the indicated effector-to-target ratios. Supernatant was harvested, and specific chromium release was calculated by the following formula: [(sample release − spontaneous release) × 100]/(total release − spontaneous release).

Limiting-dilution assays.

BALB/c mice were immunized i.m. with plasmid DNA as described above. Six weeks after the third immunization, two mouse spleens were taken from each group. Single-cell suspensions were obtained by homogenization, and erythrocytes were lysed with 0.83% ammonium acetate. The cells were passed through nylon wool columns, and the crude T cells thus obtained were serially diluted and plated (100 μl per well) in U-bottom 96-well plates in 18 to 24 duplicates. Stimulator peritoneal-exudate cells were obtained from BALB/c mice 3 days after thioglycolate injection, were coated with peptide (ERPQASGVYMGNLT; 50 μg/ml) for 1 h at 37°C, and were washed, irradiated (2,000 rads), and plated in 50 μl at 104 cells/well. Feeder cells were naïve BALB/c splenic cells irradiated (2,000 rads) and plated in 50 μl of 105 cells/well. The medium used was AIMV (Gibco) with 17% FCS, 5 × 10−5 M β-mercaptoethanol, and 30% MLA.144 supernatant (source of interleukin 2); in addition, interleukin 7 was added at 15 U/ml. The T cells were incubated for 7 days with coated stimulators in the presence of feeder cells at 37°C in 5% CO2. Thereafter, the cytolytic capacity of each well was determined; half of each well was incubated with a peptide-coated target, and the other half was incubated with a noncoated target. Any value greater than the background mean plus 3 standard deviations was considered positive. At each dilution the fraction of negative wells was calculated and plotted on a log scale.

In vivo protection studies.

Protection is measured by resistance to a normally lethal LCMV challenge. Mice were inoculated with DNA or with LCMV as previously described, and 6 weeks later, the animals were challenged with a normally lethal intracranial dose of LCMV (20 50% lethal doses). Mice were observed daily, and all recorded deaths occurred between days 7 and 8 following LCMV challenge.

RESULTS

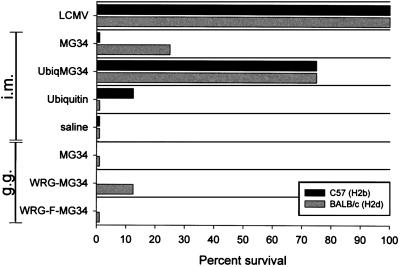

Minigenes delivered by i.m. or gene gun DNA immunization confer minimal protection; i.m. efficacy is restored by ubiquitination.

The ability of the minigene plasmids to protect against LCMV challenge was evaluated, and the results are shown in Fig. 2. Plasmids containing the isolated minigenes (MG34) failed to consistently protect mice, as did a plasmid in which the minigene cassette had been embedded in a full-length polypeptide (pWRG-MG34). The latter finding was particularly surprising because several studies have shown that embedded epitopes can be presented by MHC class I (12, 13, 29) and can induce protective CTL responses (13). The protective efficacy of the MG34 sequence was, however, restored by ubiquitination; 75% of mice survived, on both MHC backgrounds. We therefore set out to determine why the MG34 cassette failed to protect, and to identify the mechanism by which ubiquitin restored protective efficacy.

FIG. 2.

Poor protection conferred by minigenes and marked improvement following ubiquitination. BALB/c or C57BL/6 mice were immunized as indicated on the y axis (and as described in detail in the text). DNA-immunized mice received vaccine by i.m. injection or by gene gun (g.g.). Six weeks postimmunization, mice were challenged with 20 50% lethal doses of LCMV intracranially; they were then observed for 14 days. All recorded deaths occurred between days 7 and 8. The percentage of survivors in each vaccine group is shown on the x axis.

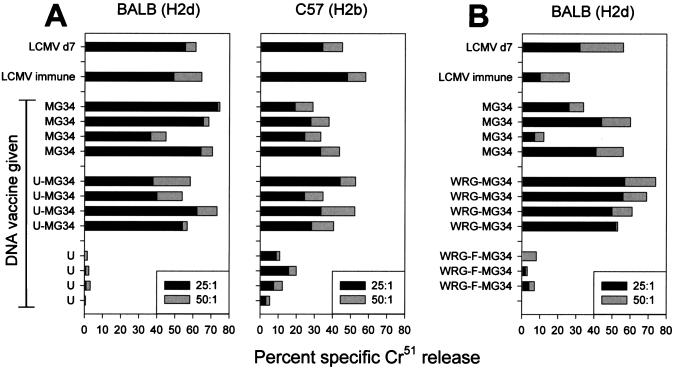

Plasmid DNA immunization induces virus-specific CTL.

Protection against LCMV challenge depends critically on the induction of antiviral CTL; we therefore asked if the minigene-containing plasmids failed to prime these important responses. Mice were immunized with each of the plasmids, either by the i.m route (Fig. 3A), or with the gene gun (Fig. 3B). Six weeks later, mice were infected with LCMV (2 × 105 PFU i.p.), and 4 days later, they were sacrificed and splenic CTL activity was evaluated. Results are shown for individual mice. As expected, mice immunized with control plasmids (pCMV-U or pWRG-F-MG34 [in which the MG34 cassette is out of frame]) failed to display high levels of CTL activity. In contrast, 23 of the 24 mice immunized with the plasmids carrying the minigenes showed convincing evidence of anti-LCMV CTL on day 4 p.i.; a single mouse immunized by gene gun with pCMV-MG34 showed no significant activity. Thus, the failure of most of these plasmids to protect cannot be explained by a complete lack of CTL induction. In this in vivo secondary stimulation, there was no significant difference between the levels of activity in mice immunized with pCMV-U-MG34 (which were protected) and those immunized with pCMV-MG34 or WRG-MG34 (which were not protected).

FIG. 3.

Minigenes induce antiviral CTL. Mice receiving DNA were immunized by i.m. injection (A) or by gene gun (B). Positive-control mice were immunized with LCMV i.p. (LCMV immune). Six weeks later, mice were challenged with LCMV i.p., and 4 days later, they were sacrificed; LCMV-specific cytotoxicity was measured in splenocytes of individual mice. LCMV day 7 (d7) splenocytes were included as a positive control for lytic activity. Solid and shaded bars represent different effector-to-target ratios, as indicated.

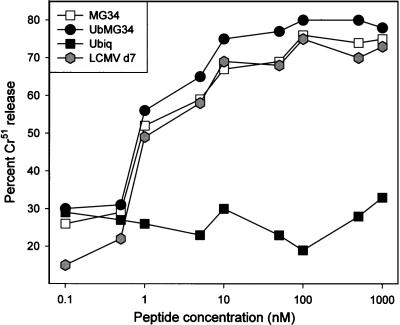

Minigene-induced CTL and virus-induced CTL are of similar affinities.

In the remaining studies we focused on i.m immunization and compared MG34 with its ubiquitinated counterpart. Since CTL were induced by both constructs, we considered it possible that a difference in affinity might explain the different levels of protection. Therefore, for CTL induced by the various plasmids, a modified in vitro cytotoxicity assay was carried out to determine the abilities of the effectors to recognize peptide-coated target cells. Effector cells were prepared as described in the above section and were incubated with target cells coated with epitope peptide over a 10,000-fold concentration range. As shown in Fig. 4, by this criterion CTL induced by MG34, ubiquitin-MG34, and whole virus are indistinguishable in their affinities and lose their ability to lyse target cells only when the peptide concentration is reduced to 1 nM or less; this is similar to results previously described for CTL specific for this epitope (56, 57).

FIG. 4.

CTL induced by minigenes and CTL induced by virus have similar affinities. BALB mice were immunized with pCMV-MG34, pCMV-U-MG34, or pCMV-U. Six weeks later, in vivo restimulation was carried out with LCMV, and 4 days later, splenocytes were harvested and used in an in vitro cytotoxicity assay. Target cells were BALB C17 alone (negative control) or coated with the Ld-presented epitope peptide RPQASGVYM at a 0.1 to 1,000 nM concentration. Percent specific chromium release, indicative of target cell lysis, is shown on the y axis.

Cytokine induction.

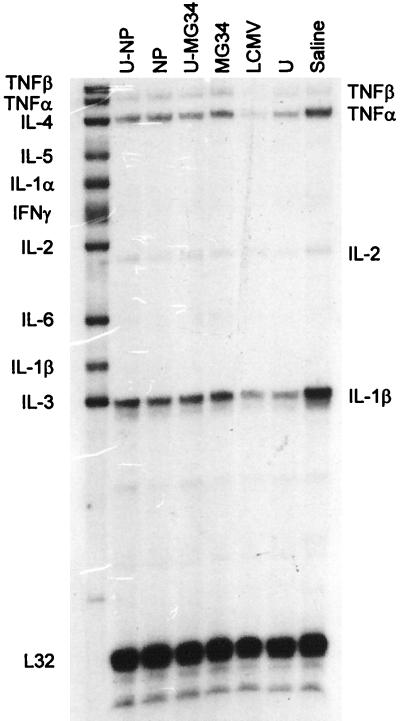

The capacity of CTL to control virus infection is not always related to their lytic activity and may instead depend on local release of cytokines, such as gamma interferon (25, 45, 49). Therefore, we considered whether CTL induced by minigenes might evince different patterns of cytokine production. We evaluated this using an RNase protection assay (Fig. 5), as well as ELIspot analyses (data not shown). By these yardsticks there were no significant differences among the various groups of vaccines, and the cytokines detected probably reflect the responses to ongoing LCMV infection.

FIG. 5.

RNase protection analysis. Mice were immunized as shown above each lane and were subjected to in vivo secondary restimulation with LCMV 6 weeks later. Four days later, spleens were harvested, and RNA was prepared. Equal amounts of RNA were hybridized with a mixture of radiolabeled probes specific for the indicated cytokines, and remaining single-stranded material was degraded with RNases. The protected species were separated on a denaturing gel and identified by autoradiography. The intact probes are shown in the left lane, and the protected species, which are shorter and hence faster migrating, are identified on the right of the gel. U, ubiquitin; TNF, tumor necrosis factor; IL, interleukin; IFN, interferon.

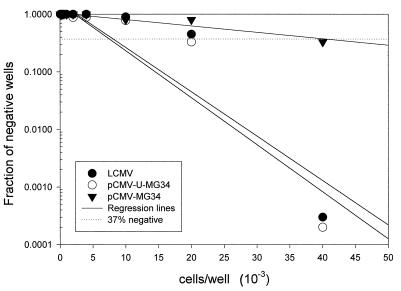

Low precursor frequency in mice immunized with pCMV-MG34 is increased by ubiquitination.

Although the initial analysis of CTL activity showed no significant difference in lytic activity on day 4 p.i. (Fig. 3), we determined the precursor frequency by limiting-dilution analysis. A striking difference was found. The frequency of anti-LCMV CTL in mice immunized with pCMV-U-MG34 is approximately 1 in 7,500 and is similar to that found in virus-immune mice, while DNA immunization with pCMV-MG34 results in only 1 in 40,000 cells being LCMV specific (Fig. 6).

FIG. 6.

Lower precursor frequency when CTL are induced by minigenes alone. Mice were immunized with LCMV or with DNA encoding MG34 or ubiquitin-MG34. Six weeks later, spleens were harvested and analyzed by limiting-dilution assay (see Materials and Methods). The fractions of negative wells at each plated cell number were plotted, and regression lines were drawn.

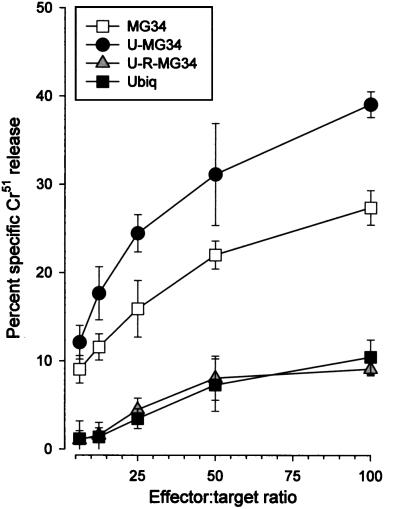

Ubiquitinated minigenes are introduced more effectively into the MHC class I pathway and appear to require polyubiquitination.

How do the epitopes in the ubiquitinated minigene gain access to MHC class I molecules? Most peptides entering the endoplasmic reticulum via the transporters for antigen processing (TAP) are generated by proteolysis of larger proteins which are synthesized within the cell and are targeted to the proteasome by addition of a polyubiquitin chain. We have previously shown that proteasome targeting can be greatly enhanced by cotranslational ubiquitination, in which the protein of interest is fused to ubiquitin, and the most obvious explanation for the enhanced presentation of the ubiquitinated minigene is that the ubiquitin-minigene fusion protein becomes polyubiquitinated and is taken to the proteasome for degradation. However, there is a second possible explanation for the improved presentation. Ubiquitin fusion proteins may be made in greater abundance than their nonubiquitinated counterparts (16), and protease complexes distinct from the proteasome can cleave the bond between ubiquitin and the “foreign” sequence; it is therefore possible that the ubiquitin-minigene fusion protein is more abundant than the minigene product alone and that the minigene sequence is released from the ubiquitin-minigene fusion protein as a free peptide before entering the antigen presentation pathway. We therefore attempted to determine whether the ubiquitinated minigene was being processed via polyubiquitination or whether it was being released from its ubiquitin fusion partner and subsequently entering the antigen processing pathway. As described elsewhere (32), proteins are targeted to the proteasome by addition of a polyubiquitin chain, each ubiquitin being covalently attached by an isopeptide bond between its C-terminal glycine and the lysine 48 residue of the preceding ubiquitin molecule. Thus, mutation of the K48 residue in ubiquitin-MG34 should prevent the attachment of a polyubiquitin chain. We therefore generated a construct (pCMV-U-R-MG34) which was identical to pCMV-U-MG34 except for a K-to-R mutation at residue 48. As shown in Fig. 7, pCMV-MG34 sensitizes cells to CTL lysis; target cell sensitization is enhanced for pCMV-U-MG34, but the K-to-R mutation renders pCMV-U-R-MG34 completely ineffective in sensitizing cells. We conclude that the enhanced immunogenicity and protective effect of the ubiquitinated minigene results from polyubiquitination and targeting to the proteasome; this leads to increased turnover by the proteasome, elevated class I MHC presentation, and improved in vivo immunogenicity reflected in the higher frequency of precursor CTL (Fig. 6).

FIG. 7.

Minigenes sensitize target cells to CTL lysis, and ubiquitination enhances this sensitization. BALB C17 cells were transfected with plasmids carrying minigenes alone (MG34), minigenes fused to ubiquitin-A76 (U-MG34), minigenes fused to a modified ubiquitin-A76 in which residue 48 had been changed from lysine to arginine (U-R-MG34), or ubiquitin alone (Ubiq). Forty-eight hours later, the cells were labeled with Cr51 and used as targets in an in vitro cytotoxicity assay with LCMV-specific effector cells, at five effector/target ratios, as shown. The experiments were repeated on at least three occasions, and very similar data were obtained each time, as reflected by the error bars.

DISCUSSION

MHC class I most often presents peptides derived from endogenously synthesized proteins, which have been degraded by the proteasome. Several years ago we showed that an endogenous peptide, encoded by a short open reading frame which we designated a minigene, could be presented by class I MHC (63), and we subsequently demonstrated that minigenes could be used to build effective multivalent vaccines against viral and bacterial diseases (1, 2, 64). These findings have been confirmed by other labs. Interestingly, recent studies suggest that epitopes encoded by minigenes may be more immunogenic than identical sequences encoded in full-length proteins; minigenes can bypass the requirement for proteasomal degradation (47), and the intracellular concentration of the epitope peptide may be considerably (∼30- to 1,800-fold) greater than when delivered as part of the native, full-length protein (3). However, some epitopes are maximally effective when embedded in a long protein, and it is difficult to predict, for any given epitope, whether maximum immunogenicity will be achieved by encoding it as a minigene or as part of a longer protein (47).

In the studies presented herein, we used minigene sequences identical to those previously expressed from recombinant vaccinia viruses, which induced protective anti-LCMV immunity (64). In contrast, when delivered by i.m. or gene gun DNA immunization, these sequences conferred little, if any, protection. This apparently superior immunogenicity of vaccinia virus-based immunization is consistent with our previous findings in a study using full-length NP as the immunogen, in which recombinant vaccinia virus delivery was more effective (90 to 100% of mice protected) than i.m. DNA immunization (∼50% protected) (68). There are many possible explanations for the improved outcome with a replication-competent viral vector: for example, more cells expressing the encoded antigen, greater antigen load, local induction of cytokines in response to vaccinia virus, different tissues and cell types infected, etc.

While greater immunogenicity of recombinant vaccinia virus vectors might have been predicted from our previous results, we were surprised by the complete failure of minigene DNA immunization to protect, and we pursued the underlying reasons. Several possible explanations, not all of which were mutually exclusive, existed. First, DNA-delivered minigenes might not be presented on the cell surface and thus might not induce CTL. However, we show that the plasmid-encoded (pCMV-MG34) minigene products are presented on the cell surface by class I MHC, at least in tissue culture, since transfected target cells are recognized and lysed by anti-LCMV CTL (Fig. 7). Second, even if presented on the cell surface in tissue culture, the peptide-MHC complexes might not be expressed in sufficient density (or on appropriate cell types) to induce CTL in vivo; indeed, others have found that plasmid-borne minigenes fail to induce CTL unless coadministered with immunostimulatory molecules (11). However, our findings contradict this, as pCMV-MG34 primes both H-2b and H-2d mice for strong secondary anti-LCMV CTL responses, measured at 4 days p.i. (Fig. 3). Third, the plasmid-induced CTL might be of lower affinity than those induced by LCMV or by recombinant vaccinia viruses. Most CTL epitopes are 9 to 10 amino acids, but slightly longer and shorter peptides (as short as 5 amino acids) can often be presented by the MHC (46, 66); these peptide-MHC complexes thus offer an array of different sites for CTL recognition. It has been clearly demonstrated that epitope-specific CTL responses in fact comprise CTL of very similar, but subtly different, specificities (33, 42), and we have shown that two viral strains which contain identical minimal CTL epitopes can induce nonreciprocal CTL recognition (that is, CTL induced by virus A recognize both viruses A and B, while CTL induced by virus B recognize only virus B) (66). Thus, it is conceivable that, for example, antigen processing may differ between infected and DNA-transfected cells, resulting in subtly different peptide-MHC complexes reaching the cell surface, leading to the induction of CTL which, although scoring positive by in vivo secondary stimulation, are of different affinities. This is addressed in Fig. 4; the affinities of CTL induced by pCMV-MG34 are indistinguishable from those of CTL induced by LCMV or by the ubiquitinated minigene product.

CTL can clear virus infection in at least two ways; by cell lysis (using perforin or fas pathways) or by local release of cytokines (25, 45). The relative importance of these two modes of action may differ depending on the virus being countered (35, 49, 53). Although clearance of primary LCMV infection appears to require perforin (34, 59), we considered it possible that vaccine-induced CTL might confer protection in part by cytokine release and that pCMV-MG34 might have induced CTL which, although lytic (Fig. 3 and 4), were deficient in cytokine release. However, a bulk analysis of splenocytes from LCMV-infected mice which had been immunized in a variety of ways showed no marked difference in cytokine mRNA levels between mice immunized with full-length NP DNA and those immunized with minigene DNA (Fig. 5), and an ELIspot enumeration of cells secreting gamma interferon showed that the two groups had similar responses (data not shown).

Since the CTL induced by pCMV-MG34 showed affinities and cytokine patterns similar to those of CTL induced by “protective” vaccines, we wondered if the frequencies of CTL precursors might be different, despite the similar in vivo secondary responses found on day 4 after LCMV infection in the various vaccine groups (Fig. 3). Therefore, we carried out a precursor frequency analysis and found that epitope-specific CTL precursors were approximately 6-fold less frequent in mice immunized with pCMV-MG34 than in mice immunized with LCMV or pCMV-U-MG34. This striking difference is most probably responsible for the difference in protective efficacy between the nonubiquitinated and ubiquitinated minigene DNA vaccines. Thus, we show that the most commonly employed criterion for evaluation of CTL responses—the presence of lytic activity following secondary stimulation—does not invariably correlate with protection; instead, the better correlate of protection is the CTL precursor frequency. Recent observations indicate that certain effector functions are active in memory CTL and do not have to be activated by prolonged stimulation or cell proliferation (39, 50). Perhaps the early effector functions of CTL, immediately following infection, are critical in controlling virus dissemination and in determining the ultimate fate of the host. By day 4 p.i., CTL activity as measured by an in vitro assay was indistinguishable in minigene- and ubiquitinated-minigene-immunized mice (Fig. 3), but by this time the fates of the vaccine groups were already sealed.

Why do the minigene DNA-immunized mice have a reduced precursor frequency, and how might their immunogenicity be improved? The results shown in Fig. 7 suggest that cotranslational ubiquitination of the MG34 oligopeptide leads to polyubiquitination beginning at the K48 residue of the fused ubiquitin, and hence to proteolysis by the proteasome and increased antigen presentation by MHC class I. Thus, the main deficiency in pCMV-MG34 appears to be in placing sufficient copies of the correct peptide-MHC complex on the cell surface. We show here that this can be rectified by ubiquitination, but other remedies can be envisioned. Although some minigenes can gain entry to the endoplasmic reticulum via TAP without having to undergo proteolytic processing, the sequences used here are fused to each other and have N- and C-terminal flanking sequences. Although we show here (Fig. 7) and have shown elsewhere (2) that processing and presentation of fused minigenes take place, it is possible that their immunogenicity might be increased by abolishing the need for processing; this might be effected either by encoding the precise epitopes in individual minigenes (without fusion or flanking sequences) or by circumventing the TAP transporter by attaching the minigene sequences to an endoplasmic reticulum-targeting sequence (9). However, our data show that any inadequacies in minigene presentation can be simply rectified, by cotranslational ubiquitination. Other means of enhancing DNA vaccine immunogenicity include coadministration of immunostimulatory molecules (8, 11, 23, 30), direct inoculation of DNA into dendritic cells (40), and so forth. We have previously shown that immunization of CD4-deficient mice results in reduced anti-LCMV precursor frequencies, and we have suggested that memory CTL responses may be maintained by CD4+ T-cell help (58). It is therefore possible that minigene-induced memory CTL may be improved if the CTL epitope is coexpressed with a helper epitope; for this reason we embedded the minigene cassette in HBsAg, which should provide class II MHC epitopes. The resulting construct, pWRG-MG34, induced CTL (Fig. 3); however, like MG34 alone, the construct did not confer protection (Fig. 2). The epitope was most likely synthesized as intended, since moving it out of the HBsAg frame (pWRG-F-MG34) abolished CTL induction (Fig. 3). Others have shown that the location of an epitope (5) and/or its flanking residues (12) can alter epitope processing and presentation, and it is possible that the flanking sequences in this plasmid were not optimal for proteasomal processing.

Our results also may shed some light on the mechanism of CTL induction by DNA immunization. It is generally agreed that professional APCs play a central role in the process (10, 14, 18, 31), but there are two conflicting mechanistic hypotheses: the first, that APCs take up soluble protein (perhaps shed by transfected myocytes) (18), and the second, that they take up and express the plasmid DNA. Surgical removal of the injected muscle has little effect on DNA immunization, suggesting that any “antigen depot” function of myocytes is dispensable (54). We have previously shown that ubiquitination of LCMV NP leads to extremely rapid destruction of the fusion protein, which fails to induce antibody responses; these data suggest that soluble ubiquitinated protein is not released (48) and thus cannot be responsible for CTL induction. In the present study, it is clear that ubiquitination of MG34 enhances CTL induction; it is difficult to imagine that this takes place through release and uptake of the ubiquitin-MG34 fusion product and correct entry into the polyubiquitination pathway. These data favor the hypothesis that the mechanism underlying DNA immunization is uptake of DNA, rather than of soluble protein, by APCs.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to Annette Lord for excellent secretarial support and to Kevin Putzer for technical support.

This work was supported by NIH grants AI-37186 (to J.L.W.) and MH-50426 (to I.L.C.) and by a postdoctoral fellowship from the Ministerio de Education y Ciencia (Spain) (to F.R.).

Footnotes

Manuscript 11246-NP from The Scripps Research Institute.

REFERENCES

- 1.An L L, Pamer E, Whitton J L. A recombinant minigene vaccine containing a nonameric cytotoxic-T-lymphocyte epitope confers limited protection against Listeria monocytogenes infection. Infect Immun. 1996;64:1685–1693. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.5.1685-1693.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.An L L, Whitton J L. A multivalent minigene vaccine, containing B-cell, cytotoxic T-lymphocyte, and Th epitopes from several microbes, induces appropriate responses in vivo and confers protection against more than one pathogen. J Virol. 1997;71:2292–2302. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.3.2292-2302.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anton L C, Yewdell J W, Bennink J R. MHC class I-associated peptides produced from endogenous gene products with vastly different efficiencies. J Immunol. 1997;158:2535–2542. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barry M A, Lai W C, Johnston S A. Protection against mycoplasma infection using expression-library immunization. Nature. 1995;377:632–635. doi: 10.1038/377632a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bergmann C C, Tong L, Cua R, Sensintaffar J, Stohlman S. Differential effects of flanking residues on presentation of epitopes from chimeric peptides. J Virol. 1994;68:5306–5310. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.8.5306-5310.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bot A, Bot S, Garcia-Sastre A, Bona C. DNA immunization of newborn mice with a plasmid-expressing nucleoprotein of influenza virus. Viral Immunol. 1996;9:207–210. doi: 10.1089/vim.1996.9.207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chapman B S, Thayer R M, Vincent K A, Haigwood N L. Effect of intron A from human cytomegalovirus (Towne) immediate-early gene on heterologous expression in mammalian cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 1991;19:3979–3986. doi: 10.1093/nar/19.14.3979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chow Y H, Huang W L, Chi W K, Chu Y D, Tao M H. Improvement of hepatitis B virus DNA vaccines by plasmids coexpressing hepatitis B surface antigen and interleukin-2. J Virol. 1997;71:169–178. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.1.169-178.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ciernik I F, Berzofsky J A, Carbone D P. Induction of cytotoxic T lymphocytes and antitumor immunity with DNA vaccines expressing single T cell epitopes. J Immunol. 1996;156:2369–2375. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Corr M, Lee D J, Carson D A, Tighe H. Gene vaccination with naked plasmid DNA: mechanism of CTL priming. J Exp Med. 1996;184:1555–1560. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.4.1555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Corr M, Tighe H, Lee D, Dudler J, Trieu M, Brinson D C, Carson D A. Costimulation provided by DNA immunization enhances antitumor immunity. J Immunol. 1997;159:4999–5004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.del Val M, Schlicht H J, Ruppert T, Reddehase M J, Koszinowski U H. Efficient processing of an antigenic sequence for presentation by MHC class I molecules depends on its neighboring residues in the protein. Cell. 1991;66:1145–1153. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90037-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.del Val M, Schlicht H J, Volkmer H, Messerle M, Reddehase M J, Koszinowski U H. Protection against lethal cytomegalovirus infection by a recombinant vaccine containing a single nonameric T-cell epitope. J Virol. 1991;65:3641–3646. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.7.3641-3646.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Doe B, Selby M, Barnett S, Baenziger J, Walker C M. Induction of cytotoxic T lymphocytes by intramuscular immunization with plasmid DNA is facilitated by bone marrow-derived cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:8578–8583. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.16.8578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Donnelly J J, Ulmer J B, Liu M A. DNA vaccines. Life Sci. 1997;60:163–172. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(96)00502-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ecker D J, Stadel J M, Butt T R, Marsh J A, Monia B P, Powers D A, Gorman J A, Clark P E, Warren F, Shatzman A, Crooke S T. Increasing gene expression in yeast by fusion to ubiquitin. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:7715–7719. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eisenbraun M D, Fuller D H, Haynes J R. Examination of parameters affecting the elicitation of humoral immune responses by particle bombardment-mediated genetic immunization. DNA Cell Biol. 1993;12:791–797. doi: 10.1089/dna.1993.12.791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fu T M, Ulmer J B, Caulfield M J, Deck R R, Friedman A, Wang S, Liu X, Donnelly J J, Liu M A. Priming of cytotoxic T lymphocytes by DNA vaccines: requirement for professional antigen presenting cells and evidence for antigen transfer from myocytes. Mol Med. 1997;3:362–371. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Furth P A, Hennighausen L, Baker C, Beatty B, Woychick R. The variability in activity of the universally expressed human cytomegalovirus immediate early gene 1 enhancer/promoter in transgenic mice. Nucleic Acids Res. 1991;19:6205–6208. doi: 10.1093/nar/19.22.6205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fynan E F, Robinson H L, Webster R G. Use of DNA encoding influenza hemagglutinin as an avian influenza vaccine. DNA Cell Biol. 1993;12:785–789. doi: 10.1089/dna.1993.12.785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fynan E F, Webster R G, Fuller D H, Haynes J R, Santoro J C, Robinson H L. DNA vaccines: protective immunizations by parenteral, mucosal, and gene-gun inoculations. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:11478–11482. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.24.11478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fynan E F, Webster R G, Fuller D H, Haynes J R, Santoro J C, Robinson H L. DNA vaccines: a novel approach to immunization. Int J Immunopharmacol. 1995;17:79–83. doi: 10.1016/0192-0561(94)00090-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Geissler M, Gesien A, Tokushige K, Wands J R. Enhancement of cellular and humoral immune responses to hepatitis C virus core protein using DNA-based vaccines augmented with cytokine-expressing plasmids. J Immunol. 1997;158:1231–1237. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gilbert S C, Plebanski M, Harris S J, Allsopp C E, Thomas R, Layton G T, Hill A V. A protein particle vaccine containing multiple malaria epitopes. Nat Biotechnol. 1997;15:1280–1284. doi: 10.1038/nbt1197-1280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Guidotti L G, Chisari F V. To kill or to cure: options in host defense against viral infection. Curr Opin Immunol. 1996;8:478–483. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(96)80034-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hassett D E, Whitton J L. DNA immunization. Trends Microbiol. 1996;4:307–312. doi: 10.1016/0966-842x(96)10048-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hassett D E, Zhang J, Whitton J L. Neonatal DNA immunization with an internal viral protein is effective in the presence of maternal antibodies and protects against subsequent viral challenge. J Virol. 1997;71:7881–7888. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.10.7881-7888.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hobbs M V, Weigle W O, Noonan D J, Torbett B E, McEvilly R J, Koch R J, Cardenas G J, Ernst D N. Patterns of cytokine gene expression by CD4+ T cells from young and old mice. J Immunol. 1993;150:3602–3614. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Isobe H, Moran T, Li S, Young A, Nathenson S G, Palese P, Bona C. Presentation by a major histocompatibility complex class I molecule of nucleoprotein peptide expressed in two different genes of an influenza virus transfectant. J Exp Med. 1995;181:203–213. doi: 10.1084/jem.181.1.203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Iwasaki A, Stiernholm B J, Chan A K, Berinstein N L, Barber B H. Enhanced CTL responses mediated by plasmid DNA immunogens encoding costimulatory molecules and cytokines. J Immunol. 1997;158:4591–4601. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Iwasaki A, Torres C A T, Ohashi P S, Robinson H L, Barber B H. The dominant role of bone marrow-derived cells in CTL induction following plasmid DNA immunization at different sites. J Immunol. 1997;159:11–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Johnson E S, Bartel B, Seufert W, Varshavsky A. Ubiquitin as a degradation signal. EMBO J. 1992;11:497–505. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05080.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Joly E, Salvato M S, Whitton J L, Oldstone M B A, Salvato M. Polymorphism of cytotoxic T-lymphocyte clones that recognize a defined 9-amino-acid immunodominant domain of lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus glycoprotein. J Virol. 1989;63:1845–1851. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.5.1845-1851.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kagi D, Ledermann B, Burki K, Seiler P, Odermatt B, Olsen K J, Podack E R, Zinkernagel R M, Hengartner H. Cytotoxicity mediated by T cells and natural killer cells is greatly impaired in perforin-deficient mice. Nature. 1994;369:31–37. doi: 10.1038/369031a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kagi D, Seiler P, Pavlovic J, Ledermann B, Burki K, Zinkernagel R M, Hengartner H. The roles of perforin- and Fas-dependent cytotoxicity in protection against cytopathic and noncytopathic viruses. Eur J Immunol. 1995;25:3256–3262. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830251209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Klavinskis L S, Whitton J L, Joly E, Oldstone M B A. Vaccination and protection from a lethal viral infection: identification, incorporation, and use of a cytotoxic T lymphocyte glycoprotein epitope. Virology. 1990;178:393–400. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(90)90336-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kozak M. Possible role of flanking nucleotides in recognition of the AUG initiator codon by eukaryotic ribosomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 1981;9:5233–5262. doi: 10.1093/nar/9.20.5233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kozak M. Recognition of AUG and alternative initiator codons is augmented by G in position +4 but is not generally affected by the nucleotides in positions +5 and +6. EMBO J. 1997;16:2482–2492. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.9.2482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lalvani A, Brookes R, Hambleton S, Britton W J, Hill A V, McMichael A J. Rapid effector function in CD8+ memory T cells. J Exp Med. 1997;186:859–865. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.6.859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Manickan E, Kanangat S, Rouse R J, Yu Z, Rouse B T. Enhancement of immune response to naked DNA vaccine by immunization with transfected dendritic cells. J Leukocyte Biol. 1997;61:125–132. doi: 10.1002/jlb.61.2.125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Manickan E, Yu Z, Rouse B T. DNA immunization of neonates induces immunity despite the presence of maternal antibody. J Clin Invest. 1997;100:2371–2375. doi: 10.1172/JCI119777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Oldstone M B A, Whitton J L, Lewicki H, Tishon A. Fine dissection of a nine amino acid glycoprotein epitope, a major determinant recognized by lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus-specific class I-restricted H-2Db cytotoxic T lymphocytes. J Exp Med. 1988;168:559–570. doi: 10.1084/jem.168.2.559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pedroza Martins L, Lau L L, Asano M S, Ahmed R. DNA vaccination against persistent viral infection. J Virol. 1995;69:2574–2582. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.4.2574-2582.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Prince A M, Whalen R, Brotman B. Successful nucleic acid based immunization of newborn chimpanzees against hepatitis B virus. Vaccine. 1997;15:916–919. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(96)00248-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ramsay A J, Ruby J, Ramshaw I A. A case for cytokines as effector molecules in the resolution of virus infection. Immunol Today. 1993;14:155–157. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(93)90277-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Reddehase M J, Rothbard J B, Koszinowski U H. A pentapeptide as minimal antigenic determinant for MHC class I-restricted T lymphocytes. Nature. 1989;337:651–653. doi: 10.1038/337651a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Restifo N P, Bacik I, Irvine K R, Yewdell J W, McCabe B J, Anderson R W, Eisenlohr L C, Rosenberg S A, Bennink J R. Antigen processing in vivo and the elicitation of primary CTL responses. J Immunol. 1995;154:4414–4422. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rodriguez F, Zhang J, Whitton J L. DNA immunization: ubiquitination of a viral protein enhances CTL induction and antiviral protection but abrogates antibody induction. J Virol. 1997;71:8497–8503. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.11.8497-8503.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ruby J, Ramshaw I A. The antiviral activity of immune CD8+ T cells is dependent on interferon-gamma. Lymphokine Cytokine Res. 1991;10:353–358. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Selin L K, Welsh R M. Cytolytically active memory CTL present in lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus-immune mice after clearance of virus infection. J Immunol. 1997;158:5366–5373. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tang D C, DeVit M, Johnston S A. Genetic immunization is a simple method for eliciting an immune response. Nature. 1992;356:152–154. doi: 10.1038/356152a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Thomson S A, Khanna R, Gardner J, Burrows S R, Coupar B, Moss D J, Suhrbier A. Minimal epitopes expressed in a recombinant polyepitope protein are processed and presented to CD8+ cytotoxic T cells: implications for vaccine design. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:5845–5849. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.13.5845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Topham D J, Tripp R A, Doherty P C. CD8+ T cells clear influenza virus by perforin or Fas-dependent processes. J Immunol. 1997;159:5197–5200. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Torres C A, Iwasaki A, Barber B H, Robinson H L. Differential dependence on target site tissue for gene gun and intramuscular DNA immunizations. J Immunol. 1997;158:4529–4532. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ulmer J B, Donnelly J J, Parker S E, Rhodes G H, Felgner P L, Dwarki V J, Gromkowski S H, Deck R R, DeWitt C M, Friedman A, Hawe L A, Leander K R, Martinez D, Perry H C, Shiver J W, Montgomery D L, Liu M A. Heterologous protection against influenza by injection of DNA encoding a viral protein. Science. 1993;259:1745–1749. doi: 10.1126/science.8456302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.van der Most R G, Concepcion R J, Oseroff C, Alexander J, Southwood S, Sidney J, Chesnut R W, Ahmed R, Sette A. Uncovering subdominant cytotoxic T-lymphocyte responses in lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus-infected BALB/c mice. J Virol. 1997;71:5110–5114. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.7.5110-5114.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.von Herrath M G, Coon B, Oldstone M B A. Low-affinity cytotoxic T-lymphocytes require IFN-gamma to clear an acute viral infection. Virology. 1997;229:349–359. doi: 10.1006/viro.1997.8442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.von Herrath M G, Yokoyama M, Dockter J, Oldstone M B A, Whitton J L. CD4-deficient mice have reduced levels of memory cytotoxic T lymphocytes after immunization and show diminished resistance to subsequent virus challenge. J Virol. 1996;70:1072–1079. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.2.1072-1079.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Walsh C M, Matloubian M, Liu C C, Ueda R, Kurahara C G, Christensen J L, Huang M T, Young J D, Ahmed R, Clark W R. Immune function in mice lacking the perforin gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:10854–10858. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.23.10854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wang Y, Xiang Z, Pasquini S, Ertl H C. Immune response to neonatal genetic immunization. Virology. 1997;228:278–284. doi: 10.1006/viro.1996.8384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Weidt G, Deppert W, Buchhop S, Dralle H, Lehmann-Grube F. Antiviral protective immunity induced by major histocompatibility complex complex class I molecule-restricted viral T-lymphocyte epitopes inserted in various positions in immunologically self and nonself proteins. J Virol. 1995;69:2654–2658. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.4.2654-2658.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Whitton J L. Lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus CTL. Semin Virol. 1990;1:257–262. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Whitton J L, Oldstone M B A. Class I MHC can present an endogenous peptide to cytotoxic T lymphocytes. J Exp Med. 1989;170:1033–1038. doi: 10.1084/jem.170.3.1033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Whitton J L, Sheng N, Oldstone M B A, McKee T A. A “string-of-beads” vaccine, comprising linked minigenes, confers protection from lethal-dose virus challenge. J Virol. 1993;67:348–352. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.1.348-352.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Whitton J L, Tishon A. Use of CTL clones in vitro to map CTL epitopes. In: Oldstone M B A, editor. Animal virus pathogenesis: a practical approach. Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press; 1990. pp. 104–115. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Whitton J L, Tishon A, Lewicki H, Gebhard J R, Cook T, Salvato M S, Joly E, Oldstone M B A. Molecular analyses of a 5-amino-acid cytotoxic T-lymphocyte (CTL) epitope: an immunodominant region which induces nonreciprocal CTL cross-reactivity. J Virol. 1989;63:4303–4310. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.10.4303-4310.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Whitton J L, Yokoyama M, Zhang J. DNA immunization in an arenavirus model. In: Eibl M, Huber C, Peter H H, Wahn U, editors. Antiviral immunity. New York, N.Y: Springer-Verlag; 1996. pp. 151–164. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Yokoyama M, Zhang J, Whitton J L. DNA immunization confers protection against lethal lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus infection. J Virol. 1995;69:2684–2688. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.4.2684-2688.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Yokoyama M, Zhang J, Whitton J L. DNA immunization: effects of vehicle and route of administration on the induction of protective antiviral immunity. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 1996;14:221–230. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.1996.tb00290.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Zarozinski C C, Fynan E F, Selin L K, Robinson H L, Welsh R M. Protective CTL-dependent immunity and enhanced immunopathology in mice immunized by particle bombardment with DNA encoding an internal virion protein. J Immunol. 1995;154:4010–4017. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]