Abstract

Triterpene esters comprise a class of secondary metabolites that are synthesized by decorating triterpene skeletons with a series of oxidation, glycosylation, and acylation modifications. Many triterpene esters with important bioactivities have been isolated and identified, including those with applications in the pesticide, pharmaceutical, and cosmetic industries. They also play essential roles in plant defense against pests, diseases, physical damage (as part of the cuticle), and regulation of root microorganisms. However, there has been no recent summary of the biosynthetic pathways and biological functions of plant triterpene esters. Here, we classify triterpene esters into five categories based on their skeletons and find that C-3 oxidation may have a significant effect on triterpenoid acylation. Fatty acid and aromatic moieties are common ligands present in triterpene esters. We further analyze triterpene ester synthesis-related acyltransferases (TEsACTs) in the triterpene biosynthetic pathway. Using an evolutionary classification of BAHD acyltransferases (BAHD-ATs) and serine carboxypeptidase-like acyltransferases (SCPL-ATs) in Arabidopsis thaliana and Oryza sativa, we classify 18 TEsACTs with identified functions from 11 species. All the triterpene-skeleton-related TEsACTs belong to BAHD-AT clades IIIa and I, and the only identified TEsACT from the SCPL-AT family belongs to the CP-I subfamily. This comprehensive review of the biosynthetic pathways and bioactivities of triterpene esters provides a foundation for further study of their bioactivities and applications in industry, agricultural production, and human health.

Key words: triterpene esters, acyltransferases, classification, biosynthesis, biological functions

Triterpene esters are secondary metabolites formed by modification of triterpene skeletons through oxidation, glycosylation, and acylation. In this review, Liu et al. classify triterpene esters on the basis of their skeletons and ligands, review their biosynthetic pathways and bioactivities, and analyze triterpene ester synthesis-related acyltransferases. This review provides a foundation for studying the biosynthesis pathway and biological activities of triterpene esters and their potential uses in industry, agricultural production, and human health.

Introduction

Plants produce various low-molecular-weight natural products that play essential roles in their adaptation to various environmental conditions. These natural products are frequently referred to as plant specialized metabolites, secondary metabolites, or natural products (Hamberger and Bak, 2013). Triterpenoids are among the largest groups of plant secondary metabolites, with more than 20 000 different structures reported (Thimmappa et al., 2014). The majority of triterpenoids can be classified into three classes: free triterpenes, acylated forms, and glycosylated forms, which are commonly referred to as saponins (Hamberger and Bak, 2013). Many triterpenoids exhibit significant functions as anti-inflammatory and anticancer agents, establishing their clear commercial value (Xu et al., 2004). Nonetheless, the natural reservoir of triterpenes remains largely unexplored and contains vast untapped potential (Thimmappa et al., 2014).

The current model of triterpenoid biosynthesis involves the joining of six isoprene units to form squalene, a branched long-chain hydrocarbon (Wang et al., 2011). In prokaryotes, squalene undergoes direct cyclization into hopanoid triterpenoids. In eukaryotes, it is initially activated into 2,3-epoxysqualene, which is then cyclized by the oxidosqualene cyclases (OSCs) into many cyclical triterpene scaffolds (Abe, 2007; Wang et al., 2011; Hamberger and Bak, 2013). These triterpene scaffolds serve as substrates for further decorations by skeleton-modifying enzymes such as cytochrome P450s (CYPs), glycosyltransferases, and acyltransferases, leading to the production of a diverse array of structurally unique molecules (Thimmappa et al., 2014; Huang et al., 2019).

Triterpenoids have garnered considerable attention from the scientific community, including researchers in the fields of plant science, pharmacy, and chemistry. Significant progress has been made in characterizing the genes, enzymes, and pathways involved in their biosynthesis. Triterpene esters are triterpenoids that serve as the major components of plant epidermal wax and as signaling molecules in the regulation of plant growth and development (Campbell and Peerbaye, 1992; Dinda et al., 2010; Haralampidis et al., 2002; Lu et al., 2018; Rahimi et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2021a; 2021b). Here, we classify the triterpene esters on the basis of their skeletons and acyl donors, describe their biosynthetic pathways, and summarize their biological functions.

Classification and structural characteristics

In recent years, tremendous progress has been made in the discovery of triterpenoids (Xu et al., 2004; Valitova et al., 2016) and the classification of triterpenoid skeletons (Abe, 2007; Haralampidis et al., 2002; Thimmappa et al., 2014; Wang et al., 2021a; 2021b). Differences in the structures of triterpene esters reflect differences in their triterpenoid skeletons, which are modified by oxidation or glycosylation and acylation (Thimmappa et al., 2014).

Classification of triterpene esters

In accordance with the number of rings in their skeletons, triterpenes can be classified as mono-, bi-, tri-, tetra-, and pentacyclic (Wang et al., 2021a; 2021b). Triterpenoids with 1–3 rings are less common than tetra- and pentacyclic triterpenes. Tetracyclic triterpenes include cycloartane-, lanostane-, cucurbitane-, dammarane-, ephane-, and tirucallane-type skeleton structures, whereas pentacyclic triterpenes have lupane-, hopane-, oleanane-, taraxaterane-, ursane-, friedelane-, and ceanothane-type skeletons (Suksamrarn et al., 2006; Kang et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2021a; 2021b).

Monocyclic-type triterpene esters

Monocyclic-type triterpene esters are commonly found in the roots of plants from the Iridaceae family (e.g., monocyclic triterpene esters in Iris germanica and Belamcanda chinensis). The acylation of monocyclic triterpenes typically occurs at the C-3 and C-16 hydroxyl groups, with long-chain fatty acids and acetic acid as donors, respectively (Ito et al., 1995; Ritzdorf et al., 1999; Bonfils et al., 2001; Orhan et al., 2002; Gu et al., 2016; Amin et al., 2021) (Figure 1). In addition, camelliol C (Table 1), a monocyclic triterpene acylated at C-3, has been detected in the oil of Camellia sasanqua (Akihisa et al., 1999).

Figure 1.

The diverse structures of triterpene esters.

Different triterpene skeletons form triterpene esters with different types of acyl donors. Triterpene skeletons in plants can be divided into monocyclic, bicyclic, tricyclic, tetracyclic, and pentacyclic triterpenes according to the number of rings. The tetracylic and pentacyclic triterpenes have various characteristic types of triterpene skeletons (top). Acyl donors can also be divided into aromatic compounds (blue), sugars (pink), and aliphatic compounds (green) (middle). Triterpenes of different skeleton types form triterpenes with different acyl donors that have different characteristics (bottom).

Table 1.

Classification of triterpenoid skeleton-modified triterpene esters.

| Triterpenoid skeleton | Compounds | Acyl donor | Species | Reaction position | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Monocyclic | 16-O-acetyl-isoiridogermanal; iristectorone K; iristectorene B; 3-O-decanoyl-16-O-acetyl-isoiridogermanal; 3-O-tetradecanoyl-16-O-acetyl-isoiridogermanal | fatty acid | Iris germanica | C-16 C-3 C-3/C-16 |

(Bonfils et al., 2001; Ito et al., 1995; Miyake and Yoshida, 1997; Orhan et al., 2002; Gu et al., 2016; Amin et al., 2021) |

| Monocyclic | camelliol C acetate | fatty acid | Camellia sasanqua | C-3 | (Akihisa et al., 1999) |

| Bicyclic | spirotriene ester; belamcandal | fatty acid |

Belinda chinensis I. germanica |

C-28/C-3 C-28 |

(Abe et al., 1991; Gu et al., 2016; Miyake et al., 1997) |

| Bicyclic | 28-acetoxyspiroiridal; 29-acetoxyspiroiridal | fatty acid | I. germanica | C-28/C-29 | (Bonfils et al., 1998, 2001; Ritzdorf et al., 1999; Fang et al., 2007; Amin et al., 2021) |

| Bicyclic | camelliol B acetate | fatty acid | C. sasanqua | C-3 | (Akihisa et al., 1999) |

| Bicyclic | lamesticumin A; lansic acid 3-ethyl ester | fatty acid | Lancium domesticum | C-3 | (Dong et al., 2011; Matsumoto et al., 2018; Nishizawa et al., 1983) |

| Bicyclic | poaceatapetol palmitic acid ester; oleic acid ester; stearic acid ester | fatty acid | Oryza sativa | C-3 | (Xue et al., 2018) |

| Onoceranoid | lamesticumin B; lamesticumin E; ethyl lansiolate; methy lansiolate | fatty acid | L. domesticum | C-21/C-23 | (Dong et al., 2011; Matsumoto et al., 2018; Nishizawa et al., 1983) |

| Tricyclic | camelliol A acetate | fatty acid | L. domesticum | C-3 | (Akihisa et al., 1999; Xue et al., 2018) |

| Tricyclic | (-)-3β,7β-dihydroxy-16-keto-thalian-15-yl acetate | fatty acid | C. sasanqua | C-15 | (Huang et al., 2019; Liu et al., 2020) |

| Tricyclic | thalian; arabidin; thalianyl pamitate; thalianyl myristate; thalianyl laurate; arabidiyl pamitate; arabidiyl myristate; arabidiyl laurate | fatty acid | Arabidopsis thaliana | C-3/C-15 | (Huang et al., 2019) |

| Euphane | euphol 3 | fatty acid | Arabidopsis lyrata | C-3 | (Liu et al., 2020) |

| Euphane | butyrospermol acetate; butyrospermol cinnamate | fatty acid | A. thaliana | C-3 | (Di Vincenzo et al., 2005; Akihisa et al., 2010, 2011) |

| Lanostane | methyl 25-hydroxy-3-epidehydrotumulosate; methyl dehydroeburiconate | fatty acid | Poria cocos | C-21 | (Kikuchi et al., 2011) |

| Lanostane | lanosta-8,24-dien-3-yl acetate | fatty acid | Dorstenia arifolia | C-3 | (Fingolo et al., 2013) |

| Lanostane | dimethyl poricoate A; dimethyl poricoate C; dimethyl poricoate G; dimethyl poricoate H | fatty acid | P. cocos | C-3/C-21 | (Kikuchi et al., 2011) |

| Lanostane | leplaeric acid B; dimethyl ester | fatty acid | Leplaea mayombensis | C-3 | (Sidjui et al., 2017) |

| Lanostane | lanosta,5ene,24-ethyl-3-O-β-D-glucopyranoside ester | β-D-glucopyranoside | Alstonia scholaris | C-3 | (Sultana et al., 2020) |

| Cucurbitane | CuB; CuE; CuC; 16-O-acetyl CuB; 16-O-acetyl CuE; 16-O-acetyl CuC; 16-O-acetyl CuI; 16-O-acetyl CuD; 16-O-acetyl CuI-Glu; 16-O-acetyl CuE-Glu; CuE-Glu | fatty acid | Citrullus lanatus | C-25 C-25/C-16 |

(Shang et al., 2014; Zhou et al., 2016; Kim et al., 2020; Zhong et al., 2022) |

| Cycloartane | cycloartenol palmitate | fatty acid | A. thaliana | C-23 | (Chen et al., 2007) |

| Cycloartane | codonopilate A; codonopilate B; codonopilate C | fatty acid | Codonopsis pilosula | C-3 | (Wakana et al., 2011; Xie et al., 2017) |

| Cycloartane | 24-methylenecyclortanyl linolate | fatty acid | C. pilosula | C-3 | (Goro et al., 1991; Wakana et al., 2011) |

| Cycloartane | anopaniester | fatty acid | Anodendron paniculatum | C-3 | (Viet Ho et al., 2018) |

| Cycloartane | β-sitosteryl linoleate; β-sitosteryl linolenate; β-sitosteryl palmitate; campesteryl linoleate; campesteryl linolenate; stigmasteryl linoleate | fatty acid | Malus pumila Mill. | C-3 | (Poirier et al., 2018) |

| Cycloartane | 24-methyelenecycloartanol cis-ferulates; 24-methylenecycloartanol trans-ferulates; cycloartenol cis-ferulates; cycloartenol cis-ferulates; cycloartenol trans-ferulates; 24-methylcholesterol cis-ferulates; 24-methylcholesterol trans-ferulates; 24-methylenecholesterol cis-ferulates; 24-methylenecholesterol trans-ferulates; stigmastanol cis-ferulate; stigmastanol trans-ferulates; sitosterol cis-ferulates; sitosterol trans-ferulates; cycloeucalenol cis-ferulates; citrostadienol cis-ferulates; cycloeucalenol trans-ferulates; gramisterol trans-ferulates; citrostadienol trans-ferulates; | aromatic | rice bran | C-3 | (Akihisa et al., 2000; Fang et al., 2003) |

| Lupane | lupeol acetate | fatty acid |

A. scholaris Brachylaena ramiflora Dorstenia arifolia Vitellaria paradoxa |

C-3 | (Chaturvedula, Chaturvedula et al., 2002; Sultana et al., 2020) |

| Lupane | lupeol-3-linoleate; lupeol-3-palmitate | fatty acid | Alstonia boonei De Wild | C-3 | (Hodges et al., 2003) |

| Lupane | lupeol linoleate | Crataeva nurvala | C-3 | (Sudharsan et al., 2005) | |

| Lupane | globrauneine A; globrauneine B; globrauneine C; globrauneine D; globrauneine E; globrauneine F | fatty acid | Globimetula braunii | C-3 | (Muhammad et al., 2020) |

| Lupane | (3β)-lup-20(29)-en-3-yl stearate | fatty acid | Maytenus salicifolia | C-3 | (De Miranda et al., 2007) |

| Lupane | lup-20(29)-en-3,28-diol 28-O-vinylacetate | fatty acid | / | C-28 | (Krainova et al., 2016) |

| Lupane | lup-20(29)-en-3,28-diol28-O-vinylbenzoate | aromatic | / | C-28 | (Krainova et al., 2016) |

| Lupane | ulmicin A; ulmicin B | aromatic | Ulmus davidiana var. japonica | C-11 | (Lee and Kim, 2001a) |

| Lupane | ulmicin C; ulmicin D; ulmicin E | aromatic | U. davidiana var. japonica | C-11/C-15 | (Lee and Kim, 2001a) |

| Lupane | betulinaldehyde-3β-yl-caffeate; betulin-3β-yl-caffeate | aromatic | Celastrus stephanotifolius | C-3 | (Chen et al., 1999) |

| Lupane | 3-O-(E)-p-coumaroyl-23-hydroxy-3-epi-betulin; 3-O-(Z)-p-coumaroyl-23-hydroxy-3-epi-betulin; 3-O-(E)-p-coumaroyl-23-hydroxybetulin; 23-O-(E)-p-coumaroyl-23-hydroxybetulin; 23-O-(Z)-p-coumaroyl-23-hydroxybetulin | aromatic | Buxus cochinchinensis | C-3 | (Pan et al., 2015) |

| Lupane | 27-O-E-caffeoylcylicodiscic acid | aromatic | Alnus viridis | C-27 | (Novakovic et al., 2017) |

| Lupane | betulinic acid-3β-yl-caffeate | aromatic |

Oenothera biennis C. stephanotifolius |

C-3 | (Chen et al., 1999; Hamburger et al., 2002; Knorr and Hamburger, 2004; Zaugg et al., 2006) |

| Lupane | 7β-(4-hydroxybenzoyloxy)-betulinic acid; 7β-(4-hydroxy-3′-methoxybenzoyloxy)-betulinic acid | aromatic | Zizyphus joazeiro | C-7 | (Schuhly et al., 1999) |

| Lupane | 27-O-p-hydroxybenzoylbetulinic acid; 27-O-protocatechuoylbetulinic acid; 27-O-syringoylbetulinic acid; 27-O-vanilloylbetulinic acid | aromatic | Hovenia dulcis | C-27 | (Kang et al., 2017) |

| Lupane | 3-O-trans-p-coumaroylalphitolic acid; 3-O-cis-p-coumaroylalphitolic acid | aromatic | H. dulcis | C-3 | (Kang et al., 2017; Schuhly et al., 1999; Yagi et al., 1978) |

| Lupane | 2-O-E-caffeoyl-3-O-E-p-coumaroyl-27-hydroxymethylalphitolic acid; 2-O-E-caffeoyl-3-O-Z-p-coumaroyl-27-hydroxymethylalphitolic acid | aromatic | A. viridis | C-2/C-3 | (Novakovic et al., 2017) |

| Lupane | 2-O-E-caffeoyl-27-hydroxymethylalphitolic acid; 27-hydroxybetunolic acid; 2-O-E-caffeoylalphitolic acid | aromatic | A. viridis | C-2 | (Novakovic et al., 2017) |

| Oleanane | avenacin A-1; avenacin A-2; avenacin B-1; avenacin B-2 | fatty acid | Avena strigosa | C-21 | (Mugford et al., 2009) |

| Oleanane | (3β)-olean-18-en-3-yl stearate | fatty acid | M. salicifolia | C-3 | (De Miranda et al., 2007) |

| Oleanane | oleana-9(11),12-dien-3-yl acetate; oleana-9(11),12-dien-3-yl decanoate; 12,13-epoxyolean-3-yl acetate; 12,13-epoxyolean-9(11)en-3-yl acetate | fatty acid | D. arifolia | C-3 | (Fingolo et al., 2013) |

| Oleanane | 22-hydroxy-29-methoxy-3-tetradecanoate-olean-12-ene | fatty acid | Maytenus cuzcoina | C-3/C-29 | (Reyes et al., 2017) |

| Oleanane | alstoprenyol | fatty acid | A. scholaris | C-28 | (Sultana et al., 2020) |

| Oleanane | 11-oxo-β-amyrin acetate; 11-oxo-β-amyrin decanoate; 11-oxo-β-amyrin dodecanoate; 11-oxo-β-amyrin octanoate | fatty acid | D. arifolia | C-3 | (Fingolo et al., 2013) |

| Oleanane | acerotin; acerocin | fatty acid | Acer negundo L. | C-21/C-22 | (Kupchan et al., 1971) |

| Oleanane | 3-O-acetyl-α-BA (AαBA) | fatty acid | Boswellia serrata | C-3 | (Syrovets et al., 2000) |

| Oleanane | β-amyrin acetate; β-amyrin caproate; β-amyrin caprylate; β-amyrin cinnamate; β-amyrin decanoate; β-amyrin dodecanoate; β-amyrin hexadecanoate; β-amyrin octanoate; β-amyrin palmitate; β-amyrin tetradecanoate | fatty acid |

Manilkara subsericea V. paradoxa D. arifolia B. ramiflora |

C-3 | (Chaturvedula et al., 2002; Di Vincenzo et al., 2005; Akihisa et al., 2010, 2011; Fernandes et al., 2013; Fingolo et al., 2013) |

| Oleanane | taraxeryl acetate | fatty acid |

Ficus ovata C. pilosula Echinops taeckholmiana Atractylodes macrocephala Artemisia roxburghiana Alnus hirsuta Koelpinia linearis D. arifolia |

C-3 | (Jin et al., 2007; Koul et al., 2000; Kuete et al., 2009; Fingolo et al., 2013; Rehman et al., 2013; Shah et al., 2016; Li et al., 2017; Xie et al., 2017; Hamdan et al., 2021) |

| Oleanane | 7α-hydroxymultiflor-8-ene-3α,29-diol 3-acetate-29-benzoate; multiflora-7,9(11)-diene-3α,29-diol 3,29-dibenzoate | fatty acid | Cucurbita maxima | C-3/C-29 | (Kikuchi et al., 2014) |

| Oleanane | 7α-methoxymultiflor-8-ene-3α,29- diol 3,29-dibenzoate; 7β-methoxymultiflor-8-ene-3α,29-diol 3,29-dibenzoate | fatty acid | C. maxima | C-3/C-7/C-29 | (Kikuchi et al., 2014) |

| Oleanane | (3α,7β)-3,7,29-trihydroxymultiflor-8-ene-3,29-diyl dibenzoate; (3α)-3,29-dihydroxy-7-oxomultiflor-8-ene-3,29-diyl dibenzoate | fatty acid | Trichosanthes kirilowii | C-3/C-29 | (Tao et al., 2005) |

| Oleanane | olean-28-aL-3β-yl caffeate | aromatic | C. stephanotifolius | C-3 | (Chen et al., 1999) |

| Oleanane | 2-O-E-caffeoyl-3-epimaslinic acid | aromatic | A. viridis | C-2 | (Novakovic et al., 2017) |

| Oleanane | 3-acetoxy-27-trans-caffeoyloxyolean-12-en-28-oic acid methyl ester | aromatic | Peganum nigellastrum | C-3/C-27/C-28 | (Ma et al., 2007) |

| Oleanane | 3β-trans-(3,4-dihydroxycinnamoyloxy)olean-12-en-28-oic acid; 3β-trans-(3,4-dihydroxycinnamoyloxy)olean-18-en-28-oic acid | aromatic | O. biennis | C-3 | (Hamburger et al., 2002; Knorr and Hamburger, 2004; Zaugg et al., 2006) |

| Oleanane | 23-galloylarjunolic acid | aromatic | Terminalia macroptera | C-23 | (Jürgen et al., 1998) |

| Oleanane | 3,24-(S)-hexahydoxydiphenoyl-2α,3β,23,24-tetrahydroxyolean-12-en-28-oic acid | aromatic | Castanopsis fissa | C-3/C-4 | (Huang et al., 2011) |

| Oleanane | 3β-hydroxy-27-p-(Z)-coumaroyloxyolean-12-en-28-oic acid; 3β-hydroxy-27-(E)-feruloyloxyolean-12-en-28-oic acid; 3β-hydroxy-27-(Z)-feruloyloxyolean-12-en-28-oic acid; uncarinic acid E | aromatic | Keetia leucantha | C-27 | (Lee et al., 2000; Bero et al., 2013; Beaufay et al., 2017, 2019) |

| Oleanane | germanicol caffeoyl ester; germanicol trans-coumaroyl ester; germanicol cis-coumaroyl ester | aromatic | Barringtonia asiatica | C-3 | (Ragasa et al., 2011) |

| Oleanane | 3,24-di-O-galloyl-2,3-23,24-tetrahydroxyolean-12-en-28-oic acid | aromatic | Castanopsis cuspidata | C-3/C-24 | (Ogata et al., 2016) |

| Oleanane | castanopsinin E | aromatic/β-D-glucopyranoside | C. fissa | C-3/C-4/C-28 | (Huang et al., 2011) |

| Oleanane | 2α,3α,19α,24-tetrahydroxyolea-12-en-28-oic acid β-D-glucopyranosyl ester; sericoside | β-D-glucopyranosyl | Callicarpa japonica | C-28 | (Ono et al., 2009) |

| Oleanane | 28-O-p-D-glucopyranosyl ester | β-D-glucopyranoside | T. macroptera | C-23/C-28 | (Jürgen et al., 1998) |

| Ursane | ursolic acid-3-arachidate; ursolic acid-3-behenate; ursolic acid-3-heneicosylate; ursolic acid-3-linoleate; ursolic acid-3-linolenate; ursolic acid-3-oleate; ursolic acid-3-stearate; uvaol linoleate; uvaol linolenate; uvaol oleate; uvaol stearate | fatty acid | M. pumila Mill. | C-3 | (Poirier et al., 2018) |

| Ursane | ursa-9(11),12-dien-3-yl acetate; ursa-9(11),12-dien-3-yl decanoate | fatty acid | D. arifolia | C-3 | (Fingolo et al., 2013) |

| Ursane | acetyl-11-keto-amyrin; 3-O-acetyl-β-BA (AβBA); acetyl-11-keto-β-boswellic acid (AKBA) | fatty acid | B. serrata | C-3 | (Sailer et al., 1996; Syrovets et al., 2000; Lu et al., 2008) |

| Ursane | 3β,6β,19α-trihydroxy-urs-12-en-24, 28-dioic acid 24-methyl ester | fatty acid | Mitragyna diversifolia | C-24 | (Kang and Hao, 2006; Cao et al., 2014) |

| Ursane | (3β)-urs-12-en-3-yl stearate | fatty acid | M. salicifolia | C-3 | (De Miranda et al., 2007) |

| Ursane | α-amyrin acetate; α-amyrin caproate; α-amyrin linolenate; α-amyrin myristate; α-amyrin stearate; α-amyrin palmitate; α-amyrin decanoate; α-amyrin dodecanoate; α-amyrin hexadecanoate; α-amyrin octanoate; α-amyrin tetradecanoate; 11-oxo-α-amyrin acetate; 11-oxo-α-amyrin decanoate; 11-oxo-α-amyrin dodecanoate; 11-oxo-α-amyrin octanoate | fatty acid |

A. scholaris A. boonei D. arifolia B. ramiflora M. subsericea V. paradoxa |

C-3 | (Chaturvedula et al., 2002; Fingolo et al., 2013; Okoye et al., 2014; Sultana et al., 2020; Fernandes et al., 2013; Akihisa et al., 2010, 2011; Di Vincenzo et al., 2005; Fingolo et al., 2013, 2013; Poirier et al., 2018) |

| Ursane | 2α,3β,23-trihydroxy-urs-12,18-dien-28-oic acid methyl ester; 2α,3β,23-trihydroxy-urs-12,19-dien-28-oic acid methyl ester | fatty acid | Rubus allegheniensis | C-28 | (Ono et al., 2003) |

| Ursane | α-amyrin cinnamate | aromatic | V. paradoxa | C-3 | (Di Vincenzo et al., 2005; Akihisa et al., 2010, 2011) |

| Ursane | 3β-hydroxy-27-p-(E)-coumaroyloxyurs-12-en-28-oic acid; 3β-hydroxy-27-p-(Z)-coumaroyloxyurs-12-en-28-oic acid | aromatic | Uncaria rhynchophylla | C-27 | (Lee et al., 2000) |

| Ursane | 3β-hydroxy-27-(E)-feruloyloxyurs-12-en-28-oic acid; 3β-hydroxy-27-(Z)-feruloyloxyurs-12-en-28-oic acid | aromatic | K. leucantha | C-27 | (Bero et al., 2013; Beaufay et al., 2017, 2019) |

| Ursane | uncarinic acid C; uncarinic acid D | aromatic | U. rhynchophylla | C-27 | (Lee et al., 1999, 2000; Umeyama et al., 2010) |

| Ursane | kaji-ichigoside F1 | β-D-glucopyranoside | C. japonica | C-28 | (Ono et al., 2009) |

| Ursane | 2α,3α,19α,24-tetrahydroxyurs-12-en-28-oic acid β-D-glucopyran ester | β-D-glucopyranoside | C. japonica | C-28 | (Ono et al., 2009) |

| Ursane | niga-ichigoside F1 | β-D-glucopyranoside | R. allegheniensis | C-28 | (Ono et al., 2003; Tonin et al., 2016; Xia et al., 2018) |

| Ursane | 3,24-di-O-galloyl-2α,3β-23,24-tetrahydroxyurs-12-en-28-oic acid; 4-epi-niga-ichigoside F1 | β-D-glucopyranoside | C. cuspidata | C-3 C-24 |

(Ogata et al., 2016) |

| Ursane | rubusside A | β-D-glucopyranoside | R. allegheniensis | C-28 | (Ono et al., 2003) |

| Ursane | nighascholarene | β-D-glucopyranoside | A. scholaris | C-28 | (Sultana et al., 2020) |

| Hopane type | hopenyl palmitate | fatty acid | B. ramiflora | C-3 | (Chaturvedula et al., 2002) |

| Friedelane type | 3β,24β-epoxy-29-methoxy-2α,3α,6α-trihydroxy-D:A-friedelane | fatty acid | M. cuzcoina | C-29 | (Reyes et al., 2017) |

| Friedelane type | 3,24-epoxy-2,3,6-triacetoxy-29-methoxy-D:A-friedelane | fatty acid | M. cuzcoina | C-2/C-3/C-6/C-29 | (Reyes et al., 2017) |

| Ceanothane type | 27-O-protocatechuoyl-3-dehydroxyisoceanothanolic acid; 27-O-protocatechuoyl-3-dehydroxycolubrinic acid; 27-O-protocatechuoyl-3-dehydroxyepicolubrinic acid | aromatic | H. dulcis | C-27 | (Kang et al., 2017) |

| Ceanothane type | 3-O-(4-hydroxy-3-methoxybenzoyl)ceanothic acid | aromatic | Ziziphus cambodiana | C-3 | (Suksamrarn et al., 2006) |

Bicyclic-type triterpene esters

Lansium domesticum, a fruit-bearing tree commonly found in southeastern Asia, is rich in onoceranoid-type bicyclic triterpene esters (Matsumoto et al., 2018; Nishizawa et al., 1983). In the fruits, seeds, and bark of L. domesticum, the C-3 carboxyls of onoceranoid-type triterpenes react with hydroxyl donors, which are mostly alcohols with one or two carbon atoms, to form triterpene esters (Table 1) (Dong et al., 2011; Matsumoto et al., 2018, 2019). The incompletely cyclized bicyclic triterpene, camelliol B, found in C. sasanqua oil, can be acylated at C-3 to form Camelliol B acetate (compounds 1 in Figure 1) (Akihisa et al., 1999) (Table 1). In addition, certain bicyclic triterpenoids present in Oryza sativa can also be acylated at C-3 by various long-chain fatty acids (Table 1) (Xue et al., 2018). In Iridaceae, bicyclic triterpenoid acylation frequently occurs at C-3 or C-28 (Abe et al., 1991; Gu et al., 2016; Ritzdorf et al., 1999). However, in some spiro-bicyclic triterpenes of Iridaceae, acylation also occurs at C-29, as seen in Compound 1 (Figure 1) (Bonfils et al., 1998, 2001; Ritzdorf et al., 1999; Fang et al., 2007; Amin et al., 2021).

Tricyclic-type triterpene esters

Huang et al. (2019) reported that tricyclic triterpene esters found in A. thaliana play a regulatory role in the colonization and development of rhizosphere microorganisms. These triterpenes are typically acylated on the C-3 hydroxyl, C-15, or both (Table 1) (Huang et al., 2019; Liu et al., 2020). There are also some tricyclic triterpenes with long-chain fatty acids (Sohrabi et al., 2017; Huang et al., 2019). In addition to tricyclic triterpene esters in Brassicaceae, incompletely cyclized tricyclic triterpene esters with monocyclic and bicyclic-type skeletons have been found in extracts of C. sasanqua oil (Akihisa et al., 1999).

Tetracyclic-type triterpene esters

Compared with monocyclic, bicyclic, and tricyclic triterpenes, tetracyclic and pentacyclic triterpenes exhibit greater complexity of skeleton types and esterification positions. Lanostane (Kikuchi et al., 2011; Sidjui et al., 2017; Sultana et al., 2020), euphane (Di Vincenzo et al., 2005; Akihisa et al., 2010, 2011; Liu et al., 2020), and cycloartane (Di Vincenzo et al., 2005; Akihisa et al., 2010, 2011; Kikuchi et al., 2011; Sidjui et al., 2017; Liu et al., 2020; Sultana et al., 2020) are the major types of tetracyclic-type triterpene esters. These skeletons typically feature hydroxylation at C-3 and C-21, and they can react with various acyl donors to produce different types of triterpene esters (Di Vincenzo et al., 2005; Akihisa et al., 2010, 2011; Kikuchi et al., 2011; Sidjui et al., 2017; Liu et al., 2020; Sultana et al., 2020). However, a distinct group of tetracyclic triterpenes referred to as nortriterpenoids is found primarily in Schisandra chinensis (Shi et al., 2015; Yang, 2019) and Melia azedarach L. (Fan et al., 2022). Nortriterpenoids have been reviewed extensively elsewhere (Shi et al., 2015; Li et al., 2016; Yang, 2019; Fan et al., 2022; Huo et al., 2022) and are not discussed further here. In addition, another category of tetracyclic triterpenes with novel structures, the nor-cucurbitacin triterpenes (Huo et al., 2022), exhibit numerous biological functions and medicinal activities.

Pentacyclic-type triterpene esters

Pentacyclic triterpenes are widely distributed in nature and exhibit various skeleton types. The lupane (Chen et al., 1999; Lee and Kim, 2001; Chaturvedula et al., 2002; Hodges et al., 2003; Knorr and Hamburger, 2004; Sudharsan et al., 2005; Zaugg et al., 2006; de Miranda et al., 2007; Akihisa et al., 2010; Kang et al., 2017; Novakovic et al., 2017; Sultana et al., 2020), oleanane (Kupchan et al., 1971; Chen et al., 1999; Lee et al., 1999, 2000; Syrovets et al., 2000; Hamburger et al., 2002; Knorr and Hamburger, 2004; Zaugg et al., 2006; de Miranda et al., 2007; Csuk et al., 2012; Bero et al., 2013; Fernandes et al., 2013; Fingolo et al., 2013; Langer et al., 2016; Ogata et al., 2016; Beaufay et al., 2017, 2019; Novakovic et al., 2017; Reyes et al., 2017; Xiang et al., 2019), and ursane types (Sailer et al., 1996; Ono et al., 2003, 2009; Lu et al., 2008; Fingolo et al., 2013; Cao et al., 2014; Tonin et al., 2016) account for over 95% of the known configurations of pentacyclic triterpene esters (Table 1). A few hopane-, friedelane-, and ceanothane-type triterpene esters also exist. Most of these pentacyclic triterpenes are hydroxylated at the C-3 position and then esterified with various donors to produce different types of triterpene esters. Apart from the C-3 position, they can also form esters with different donors at C-2 (Novakovic et al., 2017), C-4 (Huang et al., 2011; Marzouk and MS, 2013), C-6 (Reyes et al., 2017), C-7 (Schuhly et al., 1999), C-11 (Lee and Kim, 2001a), C-15 (Lee and Kim, 2001a), C-21 (Kupchan et al., 1971; Kupchan et al. 1970), C-22 (Kupchan et al., 1971; Kupchan et al. 1970), C-23 (Pan et al., 2015), C-24 (Ogata et al., 2016), C-27 (Kang et al., 2017), C-28 (Kang et al., 2017), and C-29 (Tao et al., 2005).

Characteristics of triterpene esters

Acylation of the skeleton

Triterpene esters are classified according to both their skeleton types and the esterified ligands on their backbones. On the basis of their acyl ligands, triterpene esters are grouped into fatty acid, glycosyl, and aromatic triterpene esters (Xu et al., 2004). Our analysis revealed that most acyl ligands on triterpene esters are fatty acids, comprising 141 positions in 236 compounds. Notably, more than half (56%) of these fatty acids are non-short-chain fatty acids (C ≥ 6), which are always hydrophobic and found on plant surfaces (Di Vincenzo et al., 2005; Poirier et al., 2018; Xue et al., 2018). Approximately 40% of fatty acid triterpene esters are short-chain fatty acids (C < 6), and the remainder are both short-chain fatty acids and non-short-chain fatty acids or both short-chain fatty acids and aromatic groups (Figure 2). Multiple acylation sites frequently occur on the triterpene skeleton. We found that fatty acid donors can coexist on triterpenes (Kupchan et al., 1971; Shang et al., 2014; Gu et al., 2016; Zhou et al., 2016; Huang et al., 2019; Kim et al., 2020). Although both glucosyl and non-short-chain fatty acid esters can coexist on the same triterpene skeleton, the occurrence of both is rare. The predominant site of acylation in triterpene esters is C-3, with 67% of triterpene esters acylated at this position. Approximately 85% of these triterpene esters had only one acylation, highlighting the significance of oxidation at C-3 in triterpene ester biosynthesis.

Figure 2.

Different acyl donors and acylation sites of triterpene esters.

(A) Numbers of different types of acyl donors.

(B) Fatty acid acyl donors.

(C) Different acylation positions of triterpene esters.

(D) Acyl donors at the C-3 position.

Acylation on triterpenoid saponins

In addition to acylation directly on the triterpenoid skeleton, acylation can also occur on the sugar donor of triterpenoid saponins. This group of triterpene esters is widely distributed in nature, and their diversity is attributed to the wide range of triterpenoid scaffolds and complex glycosylation structures (Yao et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2021a, 2021b). The structural characteristics of this group of triterpenoid saponins are mainly due to the acylation that occurs on the glycosyl donor of sapogenins and the glycosylation that occurs on the triterpenoid backbone.

In nature, triterpenoid saponins are primarily used by plants to defend against various biotic and abiotic stresses (Szakiel et al., 2011). They also play an important role in human health, with reported anti-inflammatory, anticancer, and other activities (Vincken et al., 2007; Augustin et al., 2011). Acylation at different sites plays a crucial role in determining the biological activities of triterpenoid saponins. Some acylation of triterpene saponins occurs on the glycoside donors after triterpene glycosylation (Jozwiak et al., 2020; Reed et al., 2023; Wang et al., 2023; Yuan et al., 2023). For example Quillaja saponaria saponin 7 (QS-7), an acetylated saponin (on fucose C-4) from Q. saponaria, can be one of the saponin adjuvants in the Novovax NVX-CoV2373 COVID-19 vaccine. It is also a favored anticancer candidate that has shown negligible toxicity in mice (Reed et al., 2023). Another aspect involves acylation modifications of the triterpene skeleton of triterpenoid saponins (Osbourn et al., 2011; Cárdenas et al., 2019; Zhang et al., 2019; Matsuda et al., 2023). This portion likely represents advanced acylation followed by glycosylation or the simultaneous occurrence of both processes.

Biosynthetic pathways

Plants contain a variety of triterpene esters with complex biosynthetic pathways. The immediate precursor of triterpenes, 2,3-oxidosqualene, is cyclized by OSCs to form a variety of triterpene skeletons (Xu et al., 2004; Abe, 2007; Racolta et al., 2012; Thimmappa et al., 2014; Ladhari and Chappell, 2019). Subsequently, different modifying enzymes such as CYPs, UDP-glycosyltransferases (UGTs), and acyltransferases (ACTs) decorate these triterpene skeletons, converting them into triterpene esters. Most studies have focused on the early steps of the triterpene metabolic pathway catalyzed by OSCs and CYPs (Hamberger and Bak, 2013; Kim et al., 2020; Ladhari and Chappell, 2019; Mizutani, 2012; Ohnishi et al., 2009; Racolta et al., 2012). Here, we will not review details of triterpene skeleton biosynthesis, as they have been reported extensively (e.g., Xu et al., 2004; Sawai and Saito, 2011; Racolta et al., 2012; Hamberger and Bak, 2013; Thimmappa et al., 2014; Valitova et al., 2016; Ladhari and Chappell, 2019; Rahimi et al., 2019). Some UGTs involved in triterpenoid glycosylation have also been described (Lu et al., 2018; Rahimi et al., 2019). However, the role of ACTs, which catalyze an important step in triterpene ester formation, has been largely overlooked in previous studies. Currently, triterpene ester synthesis-related acyltransferases (TEsACTs) are known to belong to two acyltransferase families. The first is the BAHD acyltransferase (BAHD-AT) family, which includes benzylalcohol O-acetyltransferase (BEAT), anthocyanin O-hydroxycinnamoyltransferase (AHCT), anthranilate N-hydroxycinnamoyl-/benzoyltransferase (HCBT), and deacetylvindoline 4-O-acetyltransferase (DAT). The second is the serine carboxypeptidase-like acyltransferase (SCPL-AT) family (Bontpart et al., 2015; D'Auria, 2006). The BAHD-ATs are the most common acyltransferase superfamily in plants, and their primary substrate is Coenzyme A (CoA) (D'Auria, 2006; Moghe et al., 2023; Wang et al., 2022) (Figure 3). The acyl donor of SCPL-ATs generally originates from glucose esters (Figure 3), which are the products of UGTs. Because of the sequence homology of SCPL-ATs to serine carboxypeptidase (SCP), these enzymes are called SCP-like (SCPL); they belong to the α/β superfamily of macromolecules but lack the peptide hydrolysis activity of genuine SCPs (Shirley and Chapple, 2003; Milkowski and Strack, 2004; Mugford et al., 2009; Mugford and Milkowski, 2012).

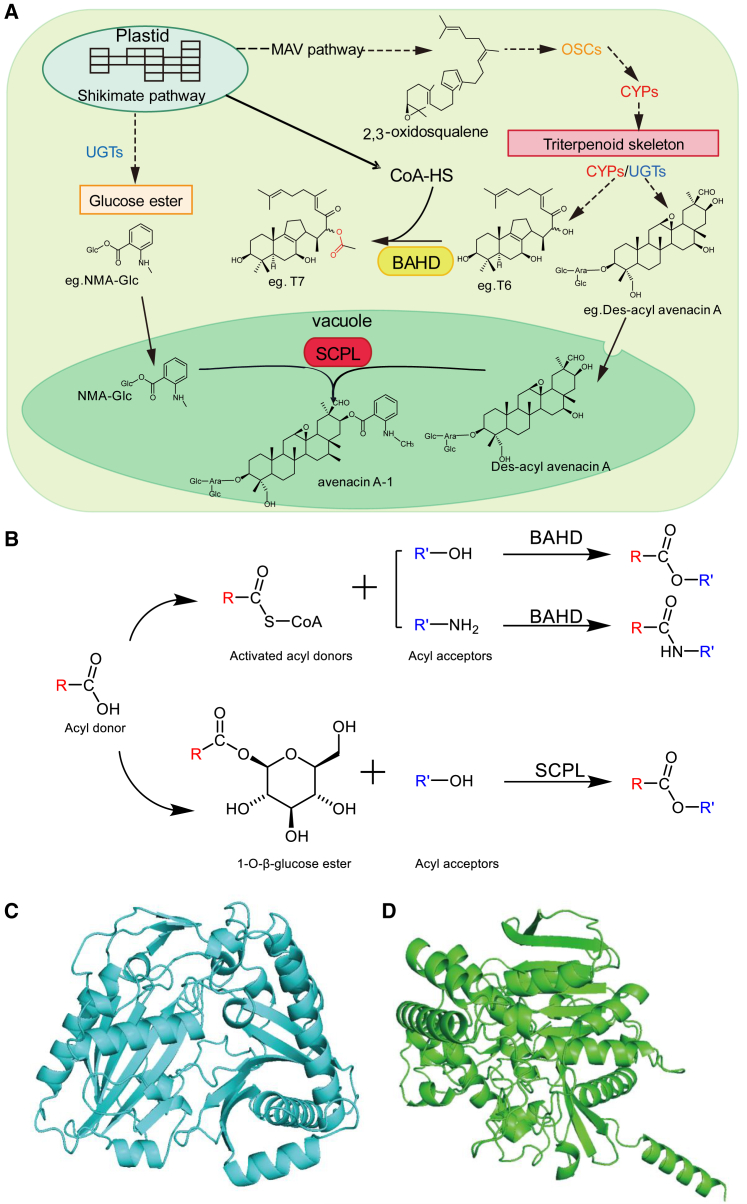

Figure 3.

Acylation mechanisms and the structure of BAHD and SCPL acyltransferases.

(A) In the cytoplasm, 2,3-oxidosqualene is catalyzed by OSCs and CYPs to synthesize triterpenoid skeletons, which are then modified by different enzymes. BAHD-ATs are located in the cytoplasm. SCPL-ATs are located in the vacuole, to which both the acyl donor and receptor are transported by tonoplastic transporters.

(B) Acylation mechanisms of BAHD-ATs and SCPL-ATs. The structure of a BAHD-AT (THAA1, C) and an SCPL-AT (AsSCPL1, D) were predicted using AlphaFold2.

BAHD-AT family

The BAHD superfamily contains a large number of enzymes. Previous reports have indicated that members of this family are mostly monomeric proteins with a cytoplasmic localization whose molecular weights range from 48 kD to 55 kD (Bontpart et al., 2015; D'Auria, 2006). Sequence comparisons among enzymes within the BAHD superfamily have revealed a low similarity of 10%–30% and a high similarity of up to 90%. This family is primarily characterized by two conserved motifs, HXXXD and DFGWG (Bontpart et al., 2015; D'Auria, 2006; Molina and Kosma, 2015) (Figure 3C). The HXXXD domain is present in the active center of the enzymes and represents a shared structural feature between the BAHD superfamily and several other CoA-dependent acyl-coenzyme superfamilies; the DFGWG motif is located near the C terminus (D'Auria, 2006; Molina and Kosma, 2015).

D'Auria (2006) constructed a phylogenetic tree of 46 functionally characterized BAHD-ATs, which were classified into five clades (Wang and Luca, 2005). In a subsequent study, Tuominen et al. (2011) further refined their classification by constructing a phylogenetic tree that divided the BAHD-ATs into eight main clades, providing a more comprehensive classification. In this study, we followed a similar approach and classified the BAHD acyltransferase superfamily members of A. thaliana and O. sativa on the basis of their phylogenetic relationships. We then performed a phylogenetic analysis that included acyltransferases associated with triterpene ester biosynthesis that have been identified and characterized to date in multiple species. Using the classification of BAHD-ATs from A. thaliana and O. sativa, we found that most BAHD-ATs associated with triterpene ester synthesis fell into clade IIIa, although three fell into clade I (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Biosynthetic pathways of triterpene esters involving BAHD acyltransferases.

(A) Full-length amino acid sequences were aligned using ClustalX and used to build a neighbor-joining phylogenetic tree with MEGA 7.0.

(B) Acyltransferases in clade I and the reactions they catalyze.

(C) Acyltransferases in clade IIIa and the reactions they catalyze. βC, 3-O-3′,4′-diacetyl-β-D-xylopyranosyl-6-O-β-D-glucopyranosyl-cycloastragenol; CuC, Cucurbitacin C; CuB, Cucurbitacin B; T7,3β,7β-dihydroxy-16-keto-thalian-15-yl acetate; T17, 7β-hydroxy-16-keto-thalian-3β-15-yl diacetate.

Fourteen TEsACTs in the BAHD family fell into clade IIIa, and most were acylated on their triterpene skeletons. Cucurbitacins (tetracyclic) are a highly studied class of triterpene esters, and BAHD-ATs have been identified from four Cucurbitaceae species. For instance, Cucumis melo acyltransferase (CmACT) and Cucumis sativus acetyltransferase (CsACT) catalyze acetylation at C-16. CmACT can catalyze the synthesis of cucurbitacin B (CuB) from cucurbitacin D (CuD) (Zhou et al., 2016), and Shang et al. found that conversion of deacetyl-CuC to CuC in cucumber was governed by CsACT, an enzyme associated with bitterness in this species (Shang et al., 2014; Zhou et al., 2016) (Figure 4B). However, Citrullus lanatus acyltransferase 1 (ClACT1) not only catalyzes the CuD to CuB conversion but also catalyzes the deacylation of CuD, as well as conversions between 16-O-acetyl CuD and 16-O-acetyl CuB; cucurbitacin I (CuI), cucurbitacin I-2-O-glucoside (CuI-Glu) and cucurbitacin E (CuE), cucurbitacin E-2-O-glucoside (CuE-Glu); 16-O-acetyl CuI, 16-O-acetyl CuI-Glu and 16-O-acetyl CuE and 16-O-acetyl CuI-Glu (Kim et al., 2020). Another acyltransferase in C. lanatus, C. lanatus acyltransferase 3 (ClACT3), can acylate CuB, CuD, CuI, CuE, CuI-Glu, and CuE-Glu on C-25 (Kim et al., 2020). TEsACTs in A. thaliana serve as a reference for identifying homologous genes in other plant species. Thalianol acyltransferase 1 (THAA1) is responsible for acylating hydroxylated thalianol, and THAA2 acylates the product of THAA1 to produce thalianin. THAA1 can also catalyze the acylation of arabidiol to generate arabidin (Figure 4A and 4C) (Sohrabi et al., 2017; Huang et al., 2019). Production of some triterpene esters is associated with plant injury responses. Upon injury, the bark of Boswellia trees can secrete a unique resin that contains triterpene esters (Ammon, 2016; Yamamoto et al., 2020; Kumar et al., 2021). Kumar et al. (2021) performed a tissue-specific transcriptome analysis of Boswellia and identified a wound-responsive BAHD acetyltransferase that could catalyze the C-3 acylation of α- and β-bowellic acid (Figure 4). Limonoids are a class of triterpenoids with complex structures and extensive activities, and analysis of their biosynthetic pathways has attracted extensive attention. Recently, De La Pena et al. (2023) clarified some of the biosynthetic pathways of limonoids, in which BAHD-ATs play a key role. Meliaceae azedarach 21 acyltransferase (MaL21AT)/Citrus sinensis 21 acyltransferase (CsL21AT), C. sinensis 1 acyltransferase (CsL1AT), C. sinensis 7 acyltransferase (CsL7AT), and M. azedarach 7 acyltransferase (MsL7AT) can catalyze the acylation of C-21, C-1, and C-7 triterpenes (De La Pena et al., 2023) (Figure 4). Other TEsACTs in clade IIIa include SOAP10 (an acyltransferase in spinach) and Q. saponaria acyltransferase 1 (QsACT1), which can catalyze the acylation of triterpene saponin glycoside donors (Jozwiak et al., 2020; Reed et al., 2023) (Figure 4B and 4C). SOAP10 can acylate Yossoside IV to Yossoside V in spinach (Jozwiak et al., 2020). QS-7 (QS saponin 7, a soap-like compound in Q. saponaria) is a saponin with excellent therapeutic properties and low toxicity that is an important vaccine adjuvant. In the biosynthetic pathway of QS7, acylation (via QsACT1) occurs simultaneously with a two-step glycosylation (via QsUGT73B44 and QsUGT91AP1), and transient expression of QsACT1, QsUGT73B44, or QsUGT91AP1 individually in Nicotiana benthamiana did not result in production of any new products (Reed et al., 2023). This result provides guidance for future studies on TEsACTs, suggesting that acylation reactions may need to be combined with other types of reactions to obtain the target product.

Besides those in clade IIIa, three other BAHD-ATs were placed into clade I. Interestingly, all of them acylate the glycoside donors of saponins (Wang et al., 2023; Yuan et al., 2023). Type-A soyasaponins, which accumulate in soybean (Glycine max) seeds, are fully acetylated at the terminal sugar of their C22 sugar chain and are responsible for the bitter taste of soybean-derived foods (Yuan et al., 2023). Wang et al. identified soyasaponin acyltransferase 1 (GmSSAcT1), a BAHD-type acetyltransferase, that can catalyze three or four consecutive acetylations on type-A soyasaponins in vitro and in planta (Yuan et al., 2023) (Figure 4B). Closely related to GmSSAcT1, Astragalus membranaceus acyltransferase 8-17 (AmAT8-17) also fell into clade Ia and can catalyze astragaloside IV at the C4ʹ-OH position (Wang et al., 2023). Another TEsACT in A. membranaceus, AmAT7-3, can modify astragaloside IV to isoastragaloside II, cyclocephaloside II, and 3-O-3ʹ,4ʹ-diacetyl-β-D-xylopyranosyl-6-O-β-D-glucopyranosyl-cycloastragenol, providing a new method for future modification of drug structure (Wang et al., 2023). Wang et al. also analyzed the crystal structure of AmAT7-3 (Wang et al., 2023), performed theoretical chemical calculations, and used site-specific mutation to modify AmAT7-3 function.

On the basis of their phylogenetic positions, we found that all the acyltransferases that modify the triterpenoid skeleton were clustered into clade IIIa, and saponin-related acyltransferases were also found in clade I. These two clades will be the focus of future TEsACT research (Figure 4A).

SCPL acyltransferase family

SCPL-ATs are a class of acyltransferases primarily located in the vacuole (Hause et al., 2002; Bontpart et al., 2015) (Figure 2). Structurally and functionally, SCPL-ATs closely resemble members of the SCP family, with both belonging to the S10 subfamily of the SC family (Milkowski and Strack, 2004). SCPL-ATs possess a highly conserved tertiary α/β hydrolase domain (Milkowski and Strack, 2004). SCPLs and SCPs share a common motif known as the Ser-His-Asp catalytic triplet, consisting of three non-contiguous amino acids. Although these amino acids are arranged differently in the primary structure, they are spatially close to each other in the tertiary structure, relying on folding of the polypeptide chain to form conserved triplets (Liao and Remington, 1990). This catalytic triplet establishes a hydrogen bond network between the SCPL protein and its substrate (Milkowski and Strack, 2004). Consequently, SCPL proteins have the ability to cleave carboxy-terminal peptide bonds within their protein or peptide substrates (Milkowski and Strack, 2004). The significant feature that distinguishes SCPLs from SCPs is that the former have the conserved pentapeptide motif “GDSYS,” whereas SCPs contain “GESYA” instead (Mugford and Milkowski, 2012) (Figure 3C).

According to the present study, at least 51 SCPL family members are found in A. thaliana (Fraser et al., 2005; Chen et al., 2020) and 71 in O. sativa (Feng and Xue, 2006); Camellia sinensis has 47 members (Ahmad et al., 2020), and Triticum aestivum has 210 (Xu et al., 2021). A phylogenetic analysis of SCPL-AT family members in rice and A. thaliana revealed division of the 121 proteins into three clades. AtSCPLs were predominantly clustered in clades I and II, whereas OsSCPLs were distributed across all three clades (Feng and Yu, 2009). A subsequent phylogenetic analysis of SCPL family members from poplar, tea, grape, and wheat showed that they also fell within three clades (Zhu et al., 2018; Ahmad et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2021a; 2021b; Xu et al., 2021). We specifically examined the SCPL proteins of A. thaliana and rice, focusing on the genes associated with triterpene ester biosynthesis identified to date. However, although acyltransferases of the SCPL family have been reported in multiple species, only one functional TEsACT of the SCPL family, AsSCPL1, has been identified. We observed that AsSCPL1 was classified within the CP-I subfamily (Figure 5A); it can serve as a reference for the discovery of other acyltransferases in the SCPL family that potentially participate in formation of triterpene esters.

Figure 5.

Biosynthetic pathways of triterpene esters involving SCPL acyltransferases.

(A) Full-length amino acid sequences were aligned using ClustalX and used to build a neighbor-joining phylogenetic tree with MEGA 7.0.

(B) Acyltransferases in clade I and the reactions they catalyze. DAA, Des-acyl avenacin A; DMA, Des-methyl avenacin A; Anth-Glc, anthraniloyl-O-glucose; NMA-Glc, N-methyl anthraniloyl-O-glucose; DAB, Des-acyl avenacin B; Benz-Glc, benzoyl-O-glucose.

Avenacins, the acylated antibacterial triterpene saponins produced in oat roots, prevent the invasion of pathogenic fungi from the soil (Mugford et al., 2009). AsSCPL1, an SCPL-AT encoded by Sad7 in oat, is a crucial enzyme in avenacin biosynthesis (Mugford et al., 2009) (Figure 5B). In addition, Sad9 encodes AsMT1, which catalyzes the production of N-methyl anthranilate (NMA) from anthranilate (Anth) (Mugford et al., 2013), and Sad10 encodes AsUGT74H5, which facilitates the formation of N-methyl anthraniloyl-O-glucose (NMA-Glc) and anthranilate-O-glucose (Anth-Glc) derived from NMA and Anth substrates, respectively (Owatworakit et al., 2013). These processes occur within the cytoplasm. Furthermore, Des-acyl avenacin A (DAA) and Des-acyl avenacin B (DAB) are synthesized within the cytoplasm by SAD1, SAD2, and other enzymes (Mylona et al., 2008; Mugford et al., 2013; Owatworakit et al., 2013). These molecules are then transported to the vacuole, where AsSCPL1 catalyzes the transfer of an acyl donor and acceptor to produce avenacins (Mugford et al., 2013; Owatworakit et al., 2013) (Figures 2 and 5B).

Biological functions

Defense

Synthesis of plant secondary metabolites is the result of a lengthy evolutionary process of adaptation to changing environmental conditions. These metabolites afford plants several advantages in responding to adverse environments, competition, co-evolution with other plants, defense against insect pests and herbivorous animal foraging, and protection against pathogenic microorganisms. Triterpene esters also play a defensive role in plant growth and development. For example, the bark of Boswellia releases a specialized oleo-gum resin enriched in boswellic acid (BA) in response to wounds. This resin contains acylated derivatives of BAs that contribute to its defensive properties (Celedon and Bohlmann, 2019; Kumar et al., 2021). Upon attack or injury, the damage-specific acyltransferase BsAT1 interacts with BAs to produce C3 α-O-acetyl-BAs as a response to external damage (Ammon, 2016; Kumar et al., 2021). Avenacins are a class of triterpene glycosylated esters that exhibit antifungal effects and provide defense against fungal invasion (Mugford et al., 2013; Owatworakit et al., 2013; Qi et al., 2004).

Cucurbitacins, a class of tetracyclic triterpenoids, possess a bitter taste and exhibit toxicity, enabling plants to resist pest and disease invasion. They serve as defense agents as well as attractants for certain polyphagous and predatory insects. The cucurbitin B (CuB) content in the leaves of various Cucurbitaceae species influences the host selectivity of the insect Liriomyza sativae. A higher concentration of CuB results in a decrease in the number of L. sativae individuals and reduces the extent of leaf damage (Zhang et al., 2004). Zou et al. found that CuB and CuE act as antagonists of 20-hydroxyecdysone, causing significant molting defects and mortality in Bombyx mori and Drosophila melanogaster larvae (Zou et al., 2018). CuB also impeded growth of Helicoverpa armigera larvae (Zou et al., 2018). Although cucurbitacins are toxic to most animals, they act as feeding attractants for Aulacophora spp. and Diabrotica spp. beetles (Lance, 1992; Brust and Foster, 1995). Luffa acufangula is rich in CuB and CuE, which stimulate beetles to feed directly (Da Costa and Jones, 1971).

Cucurbitacins possess strong cytotoxicity, which raises the question of how plants avoid damaging their own cells while synthesizing these compounds for insect resistance. In the case of cucumber leaves, cucurbitacins are synthesized in the cytoplasm and then transported and stored in the vacuole, an organelle responsible for storing various harmful substances within cells. This process may serve as a mechanism by which plants protect themselves (Zhong et al., 2022). By compartmentalizing cucurbitacins in the vacuole, the plant can effectively isolate and sequester these toxic compounds, preventing them from harming essential cellular components. This detoxification mechanism likely enables plants to balance the role of cucurbitacins as defense agents against pests and diseases without compromising their own cellular integrity.

In addition to serving as defensive compounds when plants are injured, triterpene esters also play an important role as a barrier during plant growth and development. Almost all terrestrial plants have a cuticle, which consists of the cuticle layer, the cuticle proper and the epicuticular wax; the inner cuticle layer contains cutin, a polyester layer of hydroxyl fatty acids crosslinked by ester bonds, and the outer layer of wax consisting of long-chain aliphatic compounds and a diverse array of cyclic compounds (Müller and Riederer, 2005). The cuticle serves as a protective layer and prevents non-stomatal water loss from plant organs, as well as loss of organic and inorganic substances (Szakiel et al., 2012). Triterpene esters with non-polar donors may be present in abundance in the exfoliating wax layer and stem skin of some plants (Müller and Riederer, 2005). Recently, the leaf wax of sorghum was found to be enriched in triterpenes, including pentacyclic triterpene esters, which accumulate spatially under high-temperature conditions to reinforce the cuticle and prevent water loss (Heupel, 1985; Busta et al., 2021). In addition to the waxy cuticle that covers leaves, fruit surfaces are also protected by a waxy coating. For example, the apple peel contains abundant sterol esters and trichomes that contribute to proper development of the fruit (Belding et al., 2000; Buschhaus and Jetter, 2011; Jetter and Schäffer, 2001; Poirier et al., 2018; Szakiel et al., 2012). Fatty acid triterpene esters are found in the cuticle, suggesting their potential functions as insect repellents or constituents of the cuticle layer, which helps prevent excessive water loss and loss of organic and inorganic substances. The pollen coat serves a crucial role in protecting the released pollen grain from desiccation, damage, and pathogen attack, ensuring successful pollination. Triterpene esters are present in the pollen coat as well (Breygina et al., 2021; Chichiriccò et al., 2019), where they play a vital role in preventing dehydration of the pollen grain (Xue et al., 2018). Consequently, triterpene esters could potentially serve as a novel form of biopesticide for plant protection, reducing reliance on synthetic pesticides and mitigating chemical pollution.

Regulation of rhizosphere microorganisms

In recent years, researchers have made significant findings regarding the crucial role of secondary metabolites produced by plant roots in selectively shaping the rhizosphere microbiome (Ling et al., 2022). Among these secondary metabolites, triterpene esters have emerged as a noteworthy class of compounds known for regulating the assembly of the rhizosphere microbiome.

A. thaliana is known to accumulate two tricyclic triterpene esters that are released into rhizosphere soil. Disruption of the arabidin and thalian biosynthetic pathways leads to a change in the composition and diversity of root microorganisms, suggesting that these compounds help to govern root microbiome assembly. In vitro experiments have also demonstrated that triterpene esters selectively regulate the growth of root microorganisms (Huang et al., 2019).

CuB and CuE secreted by melon roots recruit specific rhizosphere flora and enhance plant disease resistance. Specifically, CuB has been shown to selectively enrich two bacterial genera, Enterobacter and Bacillus, thus modulating the rhizosphere microbiome. This modulation, in turn, leads to robust resistance against the soil-borne fungal wilt pathogen Fusarium oxysporum (Zhong et al., 2022). Together, these studies suggest the role of triterpene esters in shaping the rhizosphere microbiome (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Potential functions of triterpene esters in plant growth, development, and environmental interactions.

Triterpene esters in Bowellia bark, oat roots, and Cucurbitaceae plants have roles in defense against pests and diseases. Triterpene esters in pollen coats, leaves, and apple peels prevent water loss. Triterpene esters in roots can be secreted and regulate rhizosphere microorganisms, thus affecting plant growth and development. Triterpene esters in roots of Codonopsis pilosula exhibit autotoxicity. CuC, Cucurbitacin C; CuB, Cucurbitacin B; T7, 3β,7β-dihydroxy-16-keto-thalian-15-yl acetate; T17, 7β-hydroxy-16-keto-thalian-3β-15-yl diacetate.

Autotoxicity in plants

Although secondary metabolites offer various benefits to plants, it is important to note that they can also have toxic effects on plants. For example, production of codonopilate A, a triterpene ester secreted in the roots of Codonopsis pilosula, leads to accumulation of reactive oxygen species in the root tips and results in autotoxicity (Wakana et al., 2011). Another compound, taraxeryl acetate, also exhibits autotoxicity in the roots of C. pilosula through a similar mechanism, although its autotoxicity is weaker than that of codonopilate A (Xie et al., 2017) (Figure 6).

Triterpene esters have important biological functions in plant defense against pests and diseases, regulation of plant growth and development, and autotoxicity. These roles establish the basis for the future use of triterpene esters as significant biopesticides. Furthermore, heterologous reconstruction of the triterpene ester biosynthetic pathway in appropriate plants offers the potential to enhance crop disease resistance, paving the way for future agricultural productivity and commercial applications.

Regulation of seed germination

Saponins have well-known functions in protecting plants against biotic and abiotic stresses (Szakiel et al., 2011). In soybean, most saponins accumulate to high levels in seeds and hypocotyls. Type-A soyasaponins are triterpene esters in which the sugar donors are acylated. However, this acylation causes a bitter taste in soy-derived foods, and deacetylated soybean saponins do not result in such bitterness (Chitisankul et al., 2021). Recently, Yuan et al. identified the acyltransferase GmSSAcT1 in soybean, which is responsible for acetylating the sugar donors of type-A soyasaponins. Interestingly, soybean seeds fail to germinate when this acyltransferase gene is knocked out, suggesting a critical role for type-A soyasaponins in the germination process of soybean seeds (Yuan et al., 2023). This finding further highlights the significance of terpenoid acylation in plant growth and development.

Concluding remarks and perspectives

In recent years, significant attention has been paid to plant secondary metabolites and their biosynthesis. With the rapid development of life science and sequencing technologies, gene-editing techniques, DNA synthesis technology, etc., more natural products have been discovered and their physiological activities and biosynthetic mechanisms characterized. Compared with other triterpenoids, triterpene esters are less well studied, despite their great potential value for human health and agriculture.

Triterpene esters have multiple roles in biotic and abiotic stress tolerance. They have functions in disease and pest resistance (Da Costa and Jones, 1971; Dinan et al., 1997; Ma, 2017; Metcalf et al., 1980; Zou et al., 2018) and also play important roles in formation of the waxy cuticle (Szakiel et al., 2012; Busta et al., 2021; Poirier et al., 2018). Thus, synthetic biology could be used to breed new plant varieties that can produce disease-resistant and pest-resistant triterpenes in specific tissues, while removing adverse-flavored compounds from fruits or seeds. Attention has also been paid to the important effects of plant secondary metabolites on rhizosphere microorganisms in recent years (Hu et al., 2018; Sasse et al., 2018; Stringlis et al., 2018; Huang et al., 2019; Koprivova et al., 2019), and studies have shown that triterpenes can regulate rhizosphere microorganisms (Huang et al., 2019; Zhong et al., 2022). Because triterpene esters play a crucial role in regulating root microbiota, they may provide a new method for regulating rhizosphere microorganisms in the future (Bai et al., 2021; Jacoby et al., 2021; Koprivova and Kopriva, 2022; Ling et al., 2022; Zhong et al., 2022). In another aspect, mutation of OsOSC12 in rice leads to water loss from pollen grains, revealing the important role of triterpene esters in male hygro-sensitive sterility of rice and laying a foundation for related studies in other species (Xue et al., 2018). Although sorghum and maize are closely related and have similar leaf wax components during the early stage of leaf development, triterpene esters are found only in the leaf wax of sorghum after the transition to adulthood. Triterpene biosynthesis in sorghum leaves is mediated primarily by a single gene, which has lost function in maize. This finding suggests the possibility of reactivating triterpenoid synthesis genes in the corn epidermis and also supports efforts to transfer surface carbon to intracellular storage for bioenergy and bioproduct innovation (Busta et al., 2021). In addition, vacuoles are known to store large amounts of plant defense compounds, and the synthesis of avenacins in vacuoles provides new insights for exploring biologically functional secondary metabolites in the future. The transporters responsible for movement of avenacin precursors are also of great interest and worthy of further investigation. Currently, triterpenoid saponins are thought to enter the vacuoles via vesicular transport from the endoplasmic reticulum or through transporters on the tonoplast. However, the mechanism for transport of NMA-Glc into the vacuole remains unknown (Mugford et al., 2013).

Nonetheless, natural triterpene esters also have a number of drawbacks, such as low contents and a lack of plant resources. The biological functions of most triterpene esters have not been clarified, and their biosynthetic pathways have not been deciphered. Further analysis of the biosynthetic pathways of triterpene esters and exploration of their biological functions will promote further utilization of these compounds. Moreover, the rational use of triterpene ester biosynthetic pathways to achieve heterologous synthesis has potential commercial value, and synthesis of triterpene esters as protein inhibitors also provides a new idea for their further study (Chen et al., 2017). In the future, triterpene esters will play significant roles in pharmaceuticals, biopesticides, and other commercial applications.

At present, there has been relatively little research on TEsACTs, and the development of related research will promote further analysis of triterpene ester biosynthetic pathways. Future analysis of triterpene ester biosynthesis and further exploration of their biological and pharmacological activities will make important contributions to biopesticide development, breeding, energy conservation, and medical resources.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2023YFA0915800), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32241040 and 31970314), and Key project at central government level: The ability establishment of sustainable use for valuable Chinese medicine resources (2060302).

Author contributions

J.L., Writing - Original Draft, investigation; X.Y. and C.K., Investigation; R.T., Review; X.H., Review; Z.X., Conceptualization, Writing - Review & Editing, Supervision, Project administration.

Acknowledgments

The authors declare no competing interests.

Published: February 13, 2024

Footnotes

Published by the Plant Communications Shanghai Editorial Office in association with Cell Press, an imprint of Elsevier Inc., on behalf of CSPB and CEMPS, CAS.

References

- Abe F., Chen R., Yamauchi T. Iridals from Belamcanda chinensis and Iris japonica. Phytochemistry. 1991;30:3379–3382. doi: 10.1016/0031-9422(91)83213-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Abe I. Enzymatic synthesis of cyclic triterpenes. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2007;24:1311–1331. doi: 10.1039/b616857b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad M.Z., Li P., She G., Xia E., Benedito V.A., Wan X.C., Zhao J. Genome-wide analysis of serine carboxypeptidase-like acyltransferase gene family for evolution and characterization of enzymes involved in the biosynthesis of galloylated catechins in the tea plant (Camellia sinensis) Front. Plant Sci. 2020;11:848. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2020.00848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akihisa T., Arai K., Kimura Y., Koike K., Kokke W., Shibata T., Nikaido T. Camelliols A-C, three novel incompletely cyclized triterpene alcohols from sasanqua oil (Camellia sasanqua) J. Nat. Prod. 1999;62:265–268. doi: 10.1021/np980336a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akihisa T., Kojima N., Katoh N., Kikuchi T., Fukatsu M., Shimizu N., Masters E.T. Triacylglycerol and triterpene ester composition of shea nuts from seven African countries. J. Oleo Sci. 2011;60:385–391. doi: 10.5650/jos.60.385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akihisa T., Kojima N., Kikuchi T., Yasukawa K., Tokuda H., T Masters E., Manosroi A., Manosroi J. Anti-inflammatory and chemopreventive effects of triterpene cinnamates and acetates from shea fat. J. Oleo Sci. 2010;59:273–280. doi: 10.5650/jos.59.273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akihisa T., Yasukawa K., Yamaura M., Ukiya M., Kimura Y., Shimizu N., Arai K. Triterpene alcohol and sterol ferulates from rice bran and their anti-inflammatory effects. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2000;48:2313–2319. doi: 10.1021/jf000135o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amin H.I.M., Hussain F.H.S., Najmaldin S.K., Thu Z.M., Ibrahim M.F., Gilardoni G., Vidari G. Phytochemistry and biological activities of Iris species growing in Iraqi Kurdistan and phenolic constituents of the traditional plant Iris postii. Molecules. 2021;26:264. doi: 10.3390/molecules26020264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ammon H.P.T. Boswellic acids and their role in chronic inflammatory diseases. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2016;928:291–327. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-41334-1_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Augustin J.M., Kuzina V., Andersen S.B., Bak S. Molecular activities, biosynthesis and evolution of triterpenoid saponins. Phytochemistry. 2011;72:435–457. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2011.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai Y., Fernández-Calvo P., Ritter A., Huang A.C., Morales-Herrera S., Bicalho K.U., Karady M., Pauwels L., Buyst D., Njo M., et al. Modulation of Arabidopsis root growth by specialized triterpenes. New Phytol. 2021;230:228–243. doi: 10.1111/nph.17144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaufay C., Henry G., Streel C., Bony E., Hérent M.F., Bero J., Quetin-Leclercq J. Optimization and validation of extraction and quantification methods of antimalarial triterpenic esters in Keetia leucantha plant and plasma. J. Chromatogr., B: Anal. Technol. Biomed. Life Sci. 2019;1104:109–118. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2018.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaufay C., Hérent M.F., Quetin-Leclercq J., Bero J. In vivo anti-malarial activity and toxicity studies of triterpenic esters isolated form Keetia leucantha and crude extracts. Malar. J. 2017;16:406. doi: 10.1186/s12936-017-2054-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bero J., Hérent M.F., Schmeda-Hirschmann G., Frédérich M., Quetin-Leclercq J. In vivo antimalarial activity of Keetia leucantha twigs extracts and in vitro antiplasmodial effect of their constituents. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2013;149:176–183. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2013.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonfils J.P., Marner F.J., Sauvaire Y. An epoxidized iridal from Iris germanica var "Rococo". Phytochemistry. 1998;48:751–753. doi: 10.1016/S0031-9422(97)01005-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bonfils J.P., Pinguet F., Culine S., Sauvaire Y. Cytotoxicity of iridals, triterpenoids from Iris, on human tumor cell lines A2780 and K562. Planta Med. 2001;67:79–81. doi: 10.1055/s-2001-10625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bontpart T., Cheynier V., Ageorges A., Terrier N. BAHD or SCPL acyltransferase? What a dilemma for acylation in the world of plant phenolic compounds. New Phytol. 2015;208:695–707. doi: 10.1111/nph.13498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breygina M., Klimenko E., Schekaleva O. Pollen germination and pollen tube growth in gymnosperms. Plants. 2021;10:1301. doi: 10.3390/plants10071301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brust G.E., Foster R.E. Semiochemical-based toxic baits for control of striped cucumber beetle (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae) in Cantaloupe. J. Econ. Entomol. 1995;88:112–116. doi: 10.1093/jee/88.1.112. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Buschhaus C., Jetter R. Composition differences between epicuticular and intracuticular wax substructures: How do plants seal their epidermal surfaces? J. Exp. Bot. 2011;62:841–853. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erq366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busta L., Schmitz E., Kosma D.K., Schnable J.C., Cahoon E.B. A co-opted steroid synthesis gene, maintained in sorghum but not maize, is associated with a divergence in leaf wax chemistry. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2021;118 doi: 10.1073/pnas.2022982118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell J.B., Peerbaye Y.A. Saponin. Res. Immunol. 1992;143:577–578. doi: 10.1016/0923-2494(92)80064-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao X.F., Wang J.S., Wang P.R., Kong L.Y. Triterpenes from the stem bark of Mitragyna diversifolia and their cytotoxic activity. Chin. J. Nat. Med. 2014;12:628–631. doi: 10.1016/S1875-5364(14)60096-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cárdenas P.D., Almeida A., Bak S. Evolution of Structural Diversity of Triterpenoids. Front. Plant Sci. 2019;10 doi: 10.3389/fpls.2019.01523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Celedon J.M., Bohlmann J. Oleoresin defenses in conifers: chemical diversity, terpene synthases and limitations of oleoresin defense under climate change. New Phytol. 2019;224:1444–1463. doi: 10.1111/nph.15984V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaturvedula V.S.P., Schilling J.K., Miller J.S., Andriantsiferana R., Rasamison V.E., Kingston D.G.I. Two new triterpene esters from the twigs of Brachylaena ramiflora from the Madagascar rainforest. J. Nat. Prod. 2002;65:1222–1224. doi: 10.1021/np0201220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen B., Duan H., Takaishi Y. Triterpene caffeoyl esters and diterpenes from Celastrus stephanotifolius. Phytochemistry. 1999;51:683–687. doi: 10.1016/S0031-9422(99)00079-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen D., Huang X., Zhou H., Luo H., Wang P., Chang Y., He X., Ni S., Shen Q., Cao G., et al. Discovery of pentacyclic triterpene 3β-ester derivatives as a new class of cholesterol ester transfer protein inhibitors. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2017;139:201–213. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2017.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J., Li W.Q., Jia Y.X. The serine carboxypeptidase-like gene SCPL41 negatively regulates membrane lipid metabolism in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plants. 2020;9:696. doi: 10.3390/plants9060696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Q., Steinhauer L., Hammerlindl J., Keller W., Zou J. Biosynthesis of phytosterol esters: Identification of a sterol O-acyltransferase in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2007;145:974–984. doi: 10.1104/pp.107.106278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chichiriccò G., Pacini E., Lanza B., Scopece G., Scopece G. Pollenkitt of some monocotyledons: lipid composition and implications for pollen germination. Plant Biol. 2019;21:920–926. doi: 10.1111/plb.12998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chitisankul W.T., Itabashi M., Son H., Takahashi Y., Ito A., Varanyanond W., Tsukamoto C. Soyasaponin composition complexities in soyfoods relating nutraceutical properties and undesirable taste characteristics. Food Science & Technology. 2021;146 doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2021.111337. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Csuk R., Schwarz S., Kluge R., Ströhl D. Does one keto group matter? Structure-activity relationships of glycyrrhetinic acid derivatives modified at position C-11. Arch. Pharm. 2012;345:28–32. doi: 10.1002/ardp.201000327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Da Costa C.P., Jones C.M. Cucumber beetle resistance and mite susceptibility controlled by the bitter gene in Cucumis sativus L. Science. 1971;172:1145–1146. doi: 10.1126/science.172.3988.1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Auria J.C. Acyltransferases in plants: a good time to be BAHD. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2006;9:331–340. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2006.03.016V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De La Peña R., Hodgson H., Liu J.C.T., Stephenson M.J., Martin A.C., Owen C., Harkess A., Leebens-Mack J., Jimenez L.E., Osbourn A., et al. Complex scaffold remodeling in plant triterpene biosynthesis. Science. 2023;379:361–368. doi: 10.1126/science.adf1017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Miranda R., de Fátima Silva G., Duarte L., Filho S. Triterpene esters isolated from leaves of Maytenus salicifolia Reissek. Helv. Chim. Acta. 2007;90:652–658. doi: 10.1002/hlca.200790068. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Di Vincenzo D., Maranz S., Serraiocco A., Vito R., Wiesman Z., Bianchi G. Regional variation in shea butter lipid and triterpene composition in four African countries. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2005;53:7473–7479. doi: 10.1021/jf0509759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinan L., Whiting P., Girault J.P., Lafont R., Dhadialla T.S., Cress D.E., Mugat B., Antoniewski C., Lepesant J.A. Cucurbitacins are insect steroid hormone antagonists acting at the ecdysteroid receptor. Biochem. J. 1997;327:643–650. doi: 10.1042/bj3270643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinda B., Debnath S., Mohanta B.C., Harigaya Y. Naturally occurring triterpenoid saponins. Chem. Biodivers. 2010;7:2327–2580. doi: 10.1002/cbdv.200800070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong S.H., Zhang C.R., Dong L., Wu Y., Yue J.M. Onoceranoid-type triterpenoids from Lansium domesticum. J. Nat. Prod. 2011;74:1042–1048. doi: 10.1021/np100943x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan W., Fan L., Wang Z., Yang L. Limonoids from the genus Melia (Meliaceae): Phytochemistry, synthesis, bioactivities, pharmacokinetics, and toxicology. Front. Pharmacol. 2022;12 doi: 10.3389/fphar.2021.795565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang N., Yu S., Badger T.M. Characterization of triterpene alcohol and sterol ferulates in rice bran using LC-MS/MS. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2003;51:3260–3267. doi: 10.1021/jf021162c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang R., Houghton P.J., Luo C., Hylands P.J. Isolation and structure determination of triterpenes from Iris tectorum. Phytochemistry. 2007;68:1242–1247. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2007.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng Y., Xue Q. The serine carboxypeptidase like gene family of rice (Oryza sativa L. ssp. japonica) Funct. Integr. Genomics. 2006;6:14–24. doi: 10.1007/s10142-005-0131-8V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng Y., Yu C. Genome-wide comparative study of rice and Arabidopsis serine carboxypeptidase-like protein families. J. Zhejiang Univ. 2009;35:1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes C.P., Corrêa A.L., Lobo J.F.R., Caramel O.P., de Almeida F.B., Castro E.S., Souza K.F.C.S., Burth P., Amorim L.M.F., Santos M.G., et al. Triterpene esters and biological activities from edible fruits of Manilkara subsericea (Mart.) Dubard. BioMed Res. Int. 2013;2013 doi: 10.1155/2013/280810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fingolo C.E., Santos T.d.S., Filho M.D.M.V., Kaplan M.A.C. Triterpene esters: Natural products from Dorstenia arifolia (Moraceae) Molecules. 2013;18:4247–4256. doi: 10.3390/molecules18044247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraser C.M., Rider L.W., Chapple C. An expression and bioinformatics analysis of the Arabidopsis serine carboxypeptidase-like gene family. Plant Physiol. 2005;138:1136–1148. doi: 10.1104/pp.104.057950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goro K., Yoshihiko H., Kuni Y., Funio K., Katsunari F. 1991. Triterpenyl Esters of Organic Acids and Hypolipidemic Agents Composed of Them. ES19850544466. [Google Scholar]

- Gu W., Xie G., Jing Y. Research progress on distribution and biological activities of iridal-type triterpenoids. Drugs Clinic. 2016;31:122–130. doi: 10.7501/j.issn.1674-5515.2016.01.028. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hamberger B., Bak S. Plant P450s as versatile drivers for evolution of species-specific chemical diversity. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2013;368 doi: 10.1098/rstb.2012.0426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamburger M., Riese U., Graf H., Melzig M.F., Ciesielski S., Baumann D., Dittmann K., Wegner C. Constituents in evening primrose oil with radical scavenging, cyclooxygenase, and neutrophil elastase inhibitory activities. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2002;50:5533–5538. doi: 10.1021/jf025581l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamdan D.I., Fayed M.A.A., Adel R. Echinops taeckholmiana Amin: Optimization of a tissue culture protocol, biological evaluation, and chemical profiling using GC and LC-MS. ACS Omega. 2021;6:13105–13115. doi: 10.1021/acsomega.1c00837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haralampidis K., Trojanowska M., Osbourn A.E. Biosynthesis of triterpenoid saponins in plants. Adv. Biochem. Eng. Biotechnol. 2002;75:31–49. doi: 10.1007/3-540-44604-4_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hause B., Meyer K., Viitanen P.V., Chapple C., Strack D. Immunolocalization of 1-O-sinapoylglucose:malate sinapoyltransferase in Arabidopsis thaliana. Planta. 2002;215:26–32. doi: 10.1007/s00425-001-0716-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heupel R.C. Varietal similarities and differences in the polycyclic isopentenoid composition of sorghum. Phytochemistry. 1985;24:2929–2937. doi: 10.1016/0031-9422(85)80030-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hodges L.D., Kweifio-Okai G., Macrides T.A. Antiprotease effect of anti-inflammatory lupeol esters. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2003;252:97–101. doi: 10.1023/A:1025569805468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu L., Robert C.A.M., Cadot S., Zhang X., Ye M., Li B., Manzo D., Chervet N., Steinger T., van der Heijden M.G.A., et al. Root exudate metabolites drive plant-soil feedbacks on growth and defense by shaping the rhizosphere microbiota. Nat. Commun. 2018;9:2738. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-05122-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang A.C., Jiang T., Liu Y.X., Bai Y., Bai Y.C., Qu B., Goossens A., Nützmann H.W., Bai Y., Osbourn A. A specialized metabolic network selectively modulates Arabidopsis root microbiota. Science. 2019;364:u6389. doi: 10.1126/science.aau6389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y.L., Tsujita T., Tanaka T., Matsuo Y., Kouno I., Li D.P., Nonaka G.i. Triterpene hexahydroxydiphenoyl esters and a quinic acid purpurogallin carbonyl ester from the leaves of Castanopsis fissa. Phytochemistry. 2011;72:2006–2014. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2011.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huo X., Wang J., Si J. Research progress on nor-cucurbitacin triterpenes. Chin. Tradit. Herb. Drugs. 2022;53:1558–1569. [Google Scholar]

- Ito H., Miyake Y., Yoshida T. New piscicidal triterpenes from Iris germanica. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1995;43:1260–1262. doi: 10.1248/cpb.43.1260. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jacoby R.P., Koprivova A., Kopriva S. Pinpointing secondary metabolites that shape the composition and function of the plant microbiome. J. Exp. Bot. 2021;72:57–69. doi: 10.1093/jxb/eraa424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jetter R., Schäffer S. Chemical composition of the Prunus laurocerasus leaf surface. Dynamic changes of the epicuticular wax film during leaf development. Plant Physiol. 2001;126:1725–1737. doi: 10.1104/pp.126.4.1725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin W., Cai X.F., Na M., Lee J.J., Bae K. Triterpenoids and diarylheptanoids from Alnus hirsuta inhibit HIF-1 in AGS cells. Arch Pharm. Res. (Seoul) 2007;30:412–418. doi: 10.1007/BF02980213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jozwiak A., Sonawane P.D., Panda S., Garagounis C., Papadopoulou K.K., Abebie B., Massalha H., Almekias-Siegl E., Scherf T., Aharoni A. Plant terpenoid metabolism co-opts a component of the cell wall biosynthesis machinery. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2020;16:740–748. doi: 10.1038/s41589-020-0541-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jürgen C., Vogler B., Klaiber I., Roos G., Walter U., Kraus W. Two triterpene esters from Terminalia macroptera bark. Phytochemistry. 1998;48:647–650. doi: 10.1016/S0031-9422(98)00154-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kang K.B., Jun J.B., Kim J.W., Kim H.W., Sung S.H. Ceanothane- and lupane-type triterpene esters from the roots of Hovenia dulcis and their antiproliferative activity on HSC-T6 cells. Phytochemistry. 2017;142:60–67. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2017.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]