Abstract

Background:

Coronary artery calcium (CAC) is a strong predictor of cardiovascular events across all racial and ethnic groups. CAC can be quantified on non-ECG-gated CTs performed for other reasons, allowing for opportunistic screening for subclinical atherosclerosis.

Objectives:

We investigated whether incidental CAC quantified on routine non-ECG-gated CTs using a deep-learning (DL) algorithm provided cardiovascular risk stratification beyond traditional risk prediction methods.

Methods:

Incidental CAC was quantified using a DL algorithm (DL-CAC) on non-ECG-gated chest CTs performed for routine care in all settings at a large academic medical center from 2014–2019. We measured the association between DL-CAC (0, 1–99, or ≥100) with all-cause death (primary outcome), and the secondary composite outcomes of death/myocardial infarction (MI)/stroke and death/MI/stroke/revascularization using Cox regression. We adjusted for age, sex, race, ethnicity, comorbidities, systolic blood pressure, lipid levels, smoking status, and anti-hypertensive use. Ten-year atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk was calculated using the pooled cohort equations.

Results:

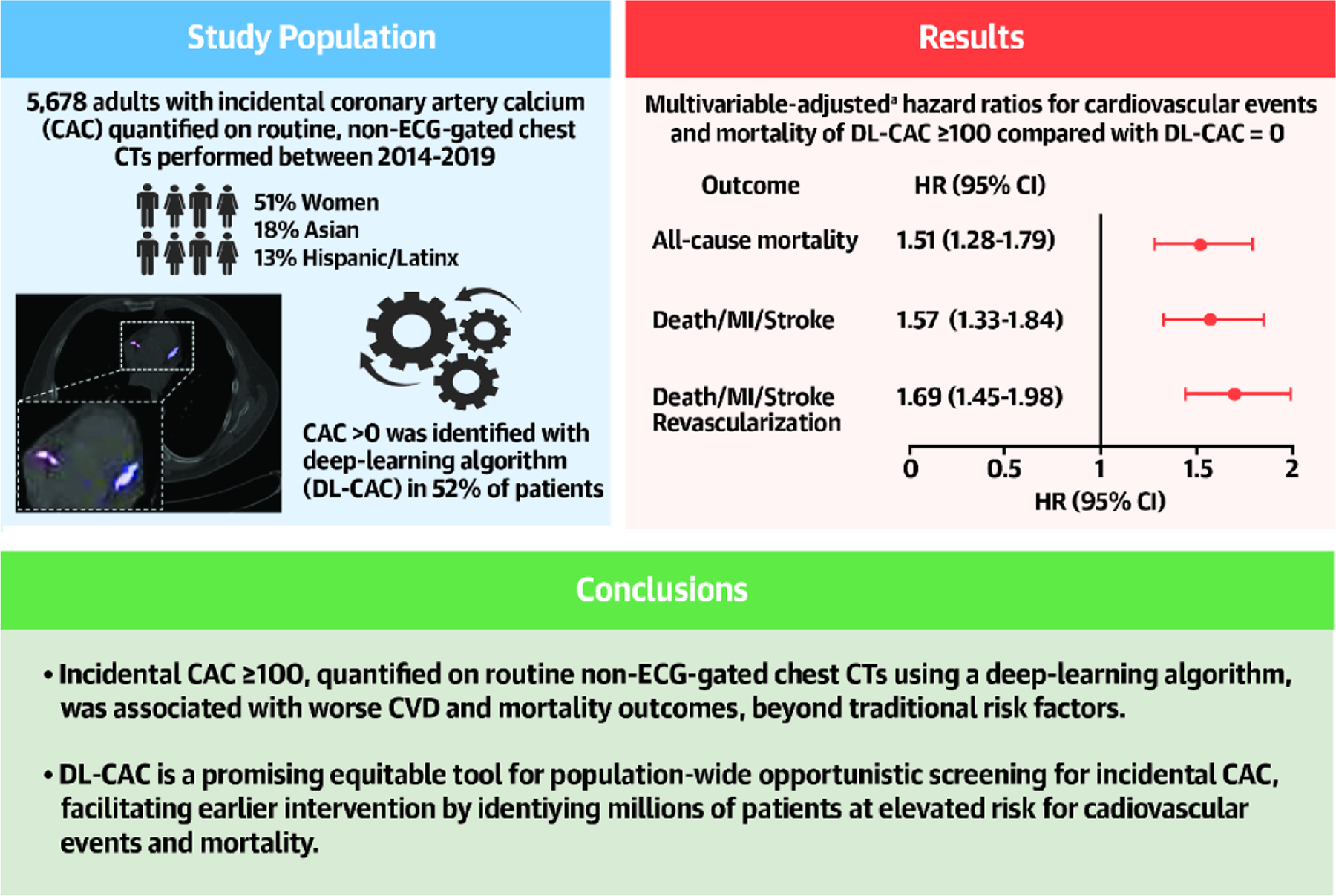

Out of 5,678 adults without ASCVD (51% women, 18% Asian, 13% Hispanic/Latinx), 52% had DL-CAC>0. Those with DL-CAC≥100 had an average PCE risk of 24%, yet only 26% were on statins. After adjustment, patients with DL-CAC≥100 had increased risk of death [HR 1.51 (1.28–1.79)], death/MI/stroke [HR 1.57 (1.33–1.84)] and death/MI/stroke/revascularization [HR 1.69 (1.45–1.98)] compared with DL-CAC=0.

Conclusion:

Incidental CAC≥100 was associated with an increased risk of all-cause death and adverse cardiovascular outcomes, beyond traditional risk factors. DL-CAC from routine non-ECG-gated CTs identifies patients at increased cardiovascular risk and holds promise as a tool for opportunistic screening to facilitate earlier intervention.

Keywords: Coronary artery calcium, screening, primary prevention, risk prediction, cardiovascular outcomes, non-gated computed tomography

CONDENSED ABSTRACT:

Coronary artery calcium (CAC) is a strong predictor of cardiovascular events. We demonstrated that incidental CAC quantified on routine non-ECG-gated CTs by a deep-learning (DL) algorithm provided cardiovascular risk stratification beyond traditional risk prediction methods using multivariable-adjusted Cox regression. After adjustment, DL-CAC≥100 was associated with increased risk of death [HR 1.51 (1.28–1.79)], death/MI/stroke [HR 1.57 (1.33–1.84)] and death/MI/stroke/revascularization [HR 1.69 (1.45–1.98)] compared with DL-CAC=0, beyond traditional cardiovascular risk factors and variables used in the pooled cohort equations. Opportunistic screening of DL-CAC from routine non-ECG-gated chest CTs can identify patients at increased cardiovascular risk and prompt earlier intervention.

INTRODUCTION:

Cardiovascular disease remains the leading cause of death in the United States and worldwide, and is largely preventable through early identification and treatment of those at highest risk.1, 2 Identification of individuals during the long asymptomatic phase facilitates opportunities for intervention that could significantly reduce morbidity and mortality. Coronary artery calcium (CAC), a measure of atherosclerotic burden, may be present in asymptomatic individuals and best predicts atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) events and mortality.3–6 CAC is typically quantified by ECG-gating – a process that obtains images synchronized with the cardiac cycle to improve coronary artery visualization. Despite its prognostic value, CAC scanning is vastly underutilized due to lack of insurance coverage and specialized imaging protocols, among other reasons.7

Conversely, over 19 million non-ECG-gated chest computed tomography (CT) scans are performed each year for reasons other than cardiovascular risk assessment.8 Prior studies have found similar prognostic importance of CAC on these non-dedicated scans.9–15 Thus, routine CAC quantification and reporting on all chest CT scans represents an opportunity for large-scale cardiovascular disease prevention in individuals unaware of their ASCVD risk. Despite recommendations to include incidental CAC in reports,16, 17 large variability exists in manual reporting practices.18–20

Artificial intelligence (AI) is a promising tool for opportunistic CAC screening of previously performed non-ECG-gated chest CT images. Already, AI models are used widely to enhance risk prediction in cardiovascular disease as well as aid in the analysis of various imaging modalities.21–23 Our group has developed and externally validated a fully-automated deep-learning (DL) algorithm to identify incidental CAC (DL-CAC) on non-ECG-gated chest CTs.7 This DL algorithm was the first to use paired ECG-gated and non-ECG-gated scans from the same individuals, resulting in a more accurate score because it is calibrated to an ECG-gated Agatston score as the “ground truth.” Thus, the purpose of this study is to assess whether incidental CAC as identified by the DL-CAC algorithm, when added to traditional cardiovascular risk factors and to variables used in the pooled cohort equations (PCE), is predictive of mortality and adverse cardiovascular events.

METHODS:

Data and Study Population

We extracted electronic health record (EHR) data from the Stanford Research Repository Clinical Data Warehouse. These include patient demographics, encounters, diagnoses, procedures, and laboratory values. We extracted CT imaging from the Stanford Picture Archiving and Communication Systems. The data obtained were limited to the Stanford Healthcare System (includes Stanford Hospital and Stanford Health Care Tri-Valley locations) and did not include data from any external healthcare site. This is further discussed in the limitations section.

We identified patients (age ≥18 years) who underwent non-contrast, non-ECG-gated chest CT imaging between January 1, 2014 – December 31, 2019 in the Stanford Healthcare system. To ensure availability of baseline data, we excluded patients without prior clinical encounters and clinical diagnoses in the Stanford EHR before their CT scan. We also excluded individuals without any follow-up encounters within the Stanford Healthcare System following their chest CT. Because the primary objective of this study was to determine if DL-CAC improved ASCVD risk prediction beyond traditional risk factors in the those without ASCVD, we excluded patients with prior diagnoses of coronary disease, peripheral arterial disease, or cerebrovascular disease identified from the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) diagnosis codes, or the following prior procedures based on Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System (HCPCS) or ICD procedure codes: percutaneous coronary intervention, coronary artery bypass grafting, or peripheral arterial revascularization. Finally, individuals with a diagnosis of metastatic cancer based on ICD diagnosis codes were excluded given their high risk of non-cardiovascular death. A list of ICD and HCPCS codes can be found in Supplemental Table 1. The end-of-study date was November 30, 2022, which was the date with the last encounter we used. We censored patients at their date of death, or, if alive, at the date of their last Stanford encounter.

Computed Tomography Data and Deep-Learning Algorithm

CT scans were performed as part of routine clinical care and represent a variety of indications across multiple practice settings and patient populations. All CT scanners utilized were manufactured by GE and Siemens. We utilized a fully-automated, deep-learning (DL) algorithm7 to quantify DL-CAC on non-ECG-gated, non-contrast CT scans. Full details of the algorithm development and test characteristics have been published previously.7, 24 Briefly, the algorithm was trained on CT scans from Stanford Healthcare and the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis, and then externally validated on paired gated and non-ECG-gated CT datasets from six geographically diverse health systems.7, 24 This algorithm was subsequently fine-tuned after the prior published study,7 and across the six external validation sites, the positive predictive value of identifying CAC was 93.5% and the sensitivity was 95.0% with the performance of the improved algorithm.

This study was approved by the Stanford Institutional Review Board with waiver of consent as retrospective, minimal-risk research.

Measurement and Definition of Baseline Characteristics and Risk Factors

Baseline patient characteristics, including sociodemographic characteristics, clinical comorbidities, vital signs, and laboratory data, were derived from EHR data on or preceding the date of their CT scan. Comorbidities were based on ICD-9 or ICD-10 codes. To improve accuracy of comorbidity classification, diagnoses were restricted to inpatient encounter diagnoses, problem list diagnoses, or clinician-entered diagnoses associated with a clinician evaluation and management procedural code. Therefore, diagnoses entered for laboratory values or imaging tests were excluded. Cigarette smoking was defined as current or former smoker. The PCE method was used to calculate the 10-year ASCVD risk, as previously described in the 2013 American College of Cardiology (ACC)/American Heart Association (AHA) guideline on the assessment of cardiovascular risk.25 The risk estimator includes sex, age, race (Black/White/Other), total and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels, systolic blood pressure, blood pressure treatment status, smoking status, and diabetes status.25 Individuals without established disease but with a 10-year predicted risk ≥20% are considered at high risk for cardiovascular disease.26

Outcomes

The primary outcome was death. Death data were ascertained from the EHR and supplemented with data from linkage to the Social Security Administration Death Master file, by making use of social security number, first name, last name, and date of birth. There were two secondary outcomes: (1) the composite of death, non-fatal MI hospitalization, and non-fatal stroke hospitalization (hereafter referred to as death/MI/stroke) and (2) the composite of death, non-fatal MI hospitalization, non-fatal stroke hospitalization, and coronary or peripheral arterial revascularization (hereafter referred to as death/MI/stroke/revascularization). Admissions for MI and stroke were identified based on inpatient admissions with those principal diagnoses. Revascularization was identified based on procedure codes from the HCPCS or ICD (Supplemental Table 1).

Statistical Methods

DL-CAC scores were separated into three clinically relevant groups: DL-CAC=0, 1–99, and ≥100 Agatston units.3, 27, 28 Baseline characteristics were stratified by DL-CAC group, with number (percentage) and mean (SD) reported, as appropriate. The magnitude of differences across groups were evaluated via standardized mean differences (Supplemental Table 2).

Kaplan-Meier curves were used to assess the cumulative risk of the outcomes of the primary and secondary outcomes by DL-CAC group. Log-rank tests were used to compare the survival time across groups. Cox regression was used to evaluate the association between DL-CAC and outcomes while adjusting for other patient characteristics. We used three nested models. First, we calculated unadjusted results (Model 1). Second, we adjusted for age and sex alone (Model 2). Finally, we added adjustment for race, ethnicity, the Elixhauser comorbidity index, and other characteristics in the PCE risk model (systolic blood pressure, total cholesterol level, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol level, diabetes status, smoking status, and anti-hypertensive use) (Model 3). Continuous variables were modeled as restricted cubic splines. We assessed the appropriateness of the proportional hazards assumption via visual assessment of the log(−log[survival]) curves for the DL-CAC stratification and the Schoenfeld residuals over time.

We accounted for missing data using multiple imputations with chained equations.29, 30 Other risk prediction variables and DL-CAC severity were included in the imputation model. For each analysis, model parameters were pooled across imputations according to Rubin’s rules to obtain the final set of inferential statistics. A complete case analysis was also performed, which yielded similar results (Supplemental Table 3).

A two-sided p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All analyses were performed using Stata/SE 16.1 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX).

RESULTS:

Baseline Characteristics

Of 8,040 individuals who underwent non-ECG-gated chest CT imaging between 2014–2019, 5,678 individuals met inclusion criteria and were free of ASCVD at baseline (see Figure 1 for participant flow diagram). The study population was 50.7% women, 18.1% Asian, and 13.0% Hispanic/Latinx, with a mean age of 60.5 ± 16.2 years. Over half (52%) had DL-CAC >0 and 1,899 (33.4%) had DL-CAC ≥100. Those with DL-CAC ≥100 were older (mean 70.8 ± 11.2 years), more likely to be male (60.7%), and had a higher estimated 10-year ASCVD risk using the PCE (23.8 ± 15.5%) (Table 1). Individuals DL-CAC ≥100 were more likely to be on anti-hypertensives (48.1%), statins (26.1%), and aspirin (15.6%), than those with lower DL-CAC. The distribution of specific baseline demographics and risk factors can be found in Table 1. Missing data are summarized in Supplemental Table 4. A list of the top 10 major indications for CT scans by 3-digit ICD diagnostic codes is detailed in Supplemental Table 5. The most common indication for CT scans was for “abnormal findings on diagnostic imaging of the lung,” accounting for 85% of CT scan indications.

Figure 1 – Study cohort flow diagram.

This figure details the initial population considered for the study, exclusion criteria used to determine the final study cohort, and details regarding the follow-up period. The arrows in the figure point to exclusion criteria at each step or additional data during the follow-up period. The median time between censoring and end-of-study was 235 days (IQR 20–985), and median follow-up time was 5.9 years (IQR 4.1–7.3) for the 4,622 patients who were alive by the end-of-study date. The median follow-up time for the study cohort overall was 5.6 years (IQR 2.6–7.0). ECG = electrocardiogram; CT = computed tomography; ASCVD = atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease; IQR = interquartile range.

Table 1 –

Baseline Characteristics by DL-CAC Group

| Baseline Characteristics | DL-CAC=0 (n=2,731) | DL-CAC=1–99 (n=1,048) | DL-CAC≥100 (n=1,899) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 51.8 ± 15.9 | 64.3 ± 11.8 | 70.8 ± 11.2 |

| Male | 1,117 (40.9%) | 532 (50.8%) | 1,152 (60.7%) |

| Race: | |||

| White | 1,477 (54.1%) | 598 (57.1%) | 1,197 (63.0%) |

| Black | 111 (4.1%) | 29 (2.8%) | 58 (3.1%) |

| Asian | 523 (19.2%) | 207 (19.8%) | 299 (15.7%) |

| Native American | 6 (0.2%) | 4 (0.4%) | 8 (0.4%) |

| Pacific Islander | 31 (1.1%) | 7 (0.7%) | 25 (1.3%) |

| Other | 523 (19.2%) | 182 (17.4%) | 266 (14.0%) |

| Unknown | 60 (2.2%) | 21 (2.0%) | 46 (2.4%) |

| Ethnicity: | |||

| Hispanic/Latinx | 420 (15.4%) | 135 (12.9%) | 183 (9.6%) |

| Non-Hispanic | 2,264 (82.9%) | 893 (85.2%) | 1,676 (88.3%) |

| Unknown | 47 (1.7%) | 20 (1.9%) | 40 (2.1%) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 270 (9.9%) | 147 (14.0%) | 333 (17.5%) |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 26.2 ± 6.3 | 27.4 ± 6.3 | 27.3 ± 6.1 |

| Systolic blood pressure, mmHg | 123.5 ± 16.6 | 128.3 ± 17.8 | 130.7 ± 19.6 |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mmHg | 74.0 ± 10.8 | 73.9 ± 10.8 | 72.1 ± 11.6 |

| LDL cholesterol, mg/dL | 104.4 ± 36.5 | 106.4 ± 37.3 | 100.0 ± 36.1 |

| HDL cholesterol, mg/dL | 57.6 ± 21.0 | 56.0 ± 19.6 | 55.9 ± 20.0 |

| Triglycerides, mg/dL | 117.4 ± 88.7 | 121.5 ± 78.8 | 114.4 ± 70.5 |

| Total cholesterol, mg/dL | 178.7 ± 47.0 | 183.6 ± 47.6 | 175.2 ± 45.0 |

| Anti-hypertensive medication | 672 (24.6%) | 398 (38.0%) | 913 (48.1%) |

| Statin medication | 275 (10.1%) | 203 (19.4%) | 496 (26.1%) |

| Aspirin medication | 208 (7.6%) | 131 (12.5%) | 296 (15.6%) |

| Cigarette smokinga | 850 (31.1%) | 429 (40.9%) | 1,033 (54.4%) |

| 10-year ASCVD risk (by PCE)b, % | 7.5 ± 10.4 | 15.7 ± 12.9 | 23.8 ± 15.5 |

| Non-metastatic cancer | 725 (26.5%) | 319 (30.4%) | 639 (33.6%) |

| Elixhauser comorbidity index | 8.1 ± 11.6 | 9.1 ± 12.2 | 10.5 ± 12.0 |

| Healthcare visits by setting: | |||

| Outpatient | 5.1 ± 7.3 | 5.2 ± 7.3 | 4.6 ± 7.0 |

| Inpatient | 0.6 ± 1.3 | 0.5 ± 1.0 | 0.6 ± 1.0 |

| Emergency department | 0.4 ± 1.7 | 0.2 ± 0.9 | 0.2 ± 0.9 |

Values are mean ± SD or n (%).

Cigarette smoking was defined as current or former cigarette smoker.

10-year ASCVD risk (by PCE) was defined as the 10-year ASCVD risk estimate as calculated by the pooled cohort equations.

ASCVD = atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease; HDL = high-density lipoprotein; LDL = low-density lipoprotein; PCE = pooled cohort equations.

Association of DL-CAC with Outcomes

Over an average of 4.8 ± 2.7 years of follow-up, the mortality rate was 3.87 per 100 person-years for the overall population. There was a graded increase in mortality rates by increasing CAC grouping: mortality rates were 2.75, 3.61, and 6.06 per 100 person-years for those with DL-CAC=0, 1–99, and ≥100, respectively.

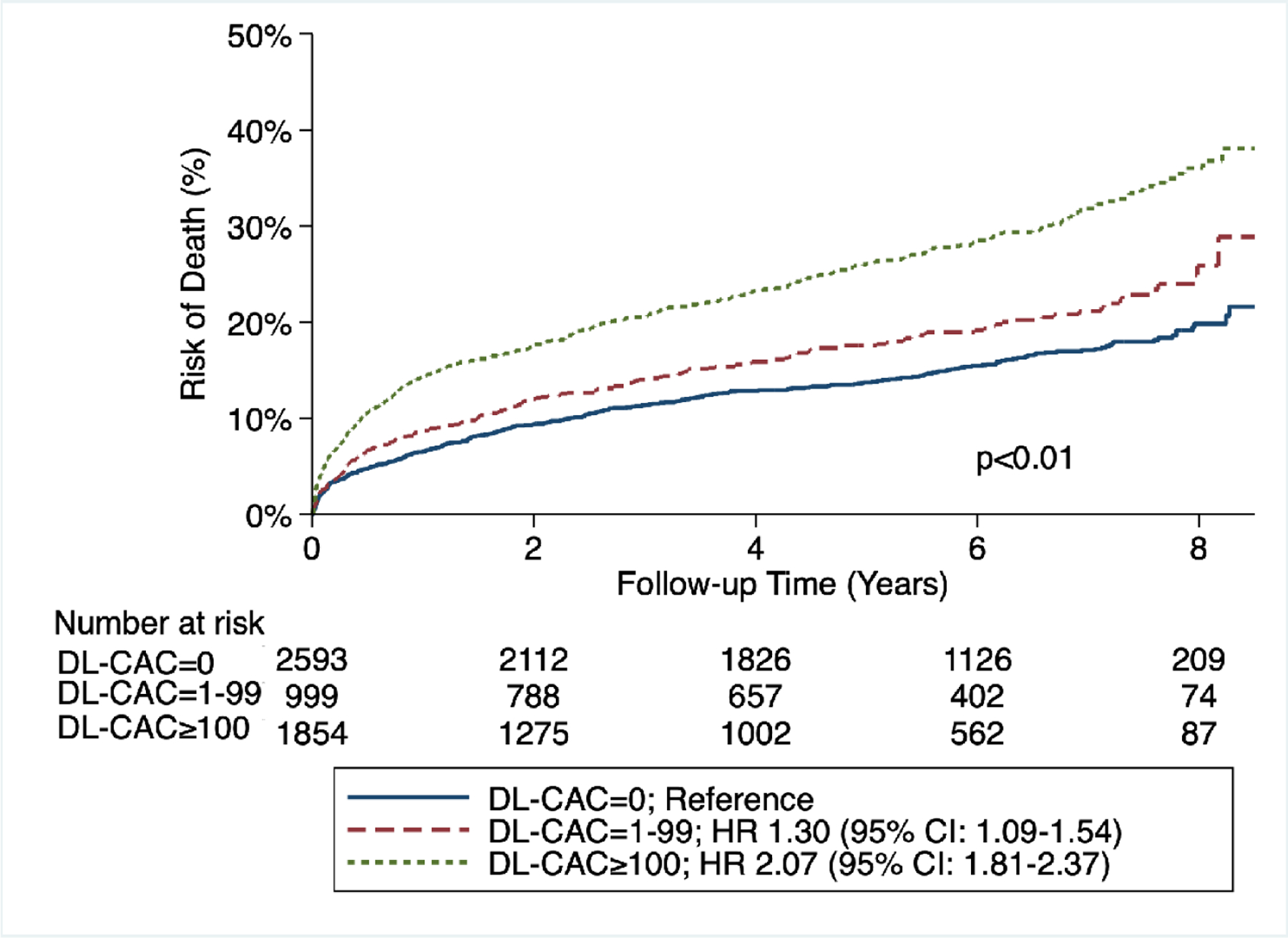

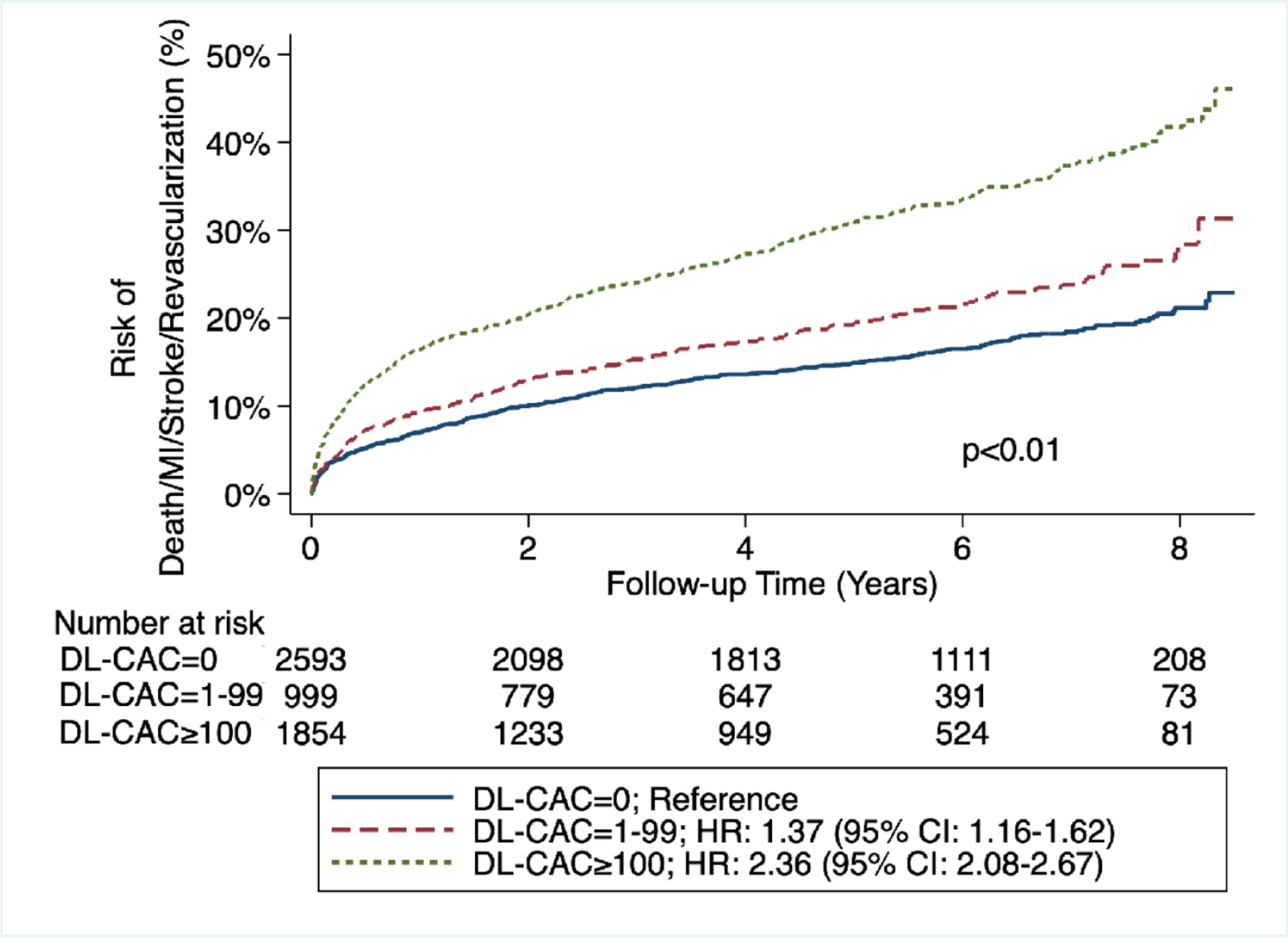

By Kaplan-Meier analysis, patients with DL-CAC=1–99 and DL-CAC ≥100 had increased risk for the primary outcome of death as well as secondary outcomes of death/MI/stroke and death/MI/stroke/revascularization (p < 0.01 for all outcomes) compared with those with DL-CAC=0 (Figure 2A/B/C).

Figure 2A/B/C – Cumulative risk of death, death/MI/stroke, and death/MI/stroke/revascularization by DL-CAC group.

(A) Risk of death by DL-CAC group and according numbers of patients at risk. Log-rank p<0.01. (B) Risk of death/MI/stroke by DL-CAC group and according numbers of patients at risk. Log-rank p<0.01. (C) Risk of death/MI/stroke/revascularization by DL-CAC group and according numbers of patients at risk. Log-rank p<0.01. MI = myocardial infarction.

There was a graded association between DL-CAC and the primary and secondary outcomes. Compared with individuals with DL-CAC=0, individuals with DL-CAC 1–99 had a 1.30-fold increased risk of death, 1.33-fold increased risk of death/MI/stroke, and 1.37-fold increased risk of death/MI/stroke/revascularization (Table 2A). Compared with individuals with DL-CAC=0, individuals with DL-CAC ≥100 had an over 2-fold increased risk of death and adverse cardiovascular outcomes (Table 2A). These differences persisted after adjusting for age, sex, and cardiovascular comorbidities (Tables 2B, 2C). In fully-adjusted analyses, compared with individuals with DL-CAC=0, individuals with DL-CAC ≥100 had a 1.51- (95% CI: 1.28–1.79), 1.57- (95% CI: 1.33–1.84), and 1.69-fold (95% CI: 1.45–1.98) increased risk of death, death/MI/stroke, and death/MI/stroke/revascularization, respectively (Table 2C and Central Illustration). A fully-adjusted complete case analysis was also performed, which showed similar results (Supplemental Table 3).

Table 2A/B/C -.

Hazard Ratios for Cardiovascular Events and Mortality by DL-CAC group

| (A) Unadjusted Hazard Ratios (Model 1) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcomes | DL-CAC=0 | DL-CAC=1–99 | DL-CAC≥100 | ||

| HR | 95% CI | HR | 95% CI | ||

| Death | Ref. | 1.30 | 1.09–1.54 | 2.07 | 1.81–2.37 |

| Death/MI/Stroke | Ref. | 1.33 | 1.12–1.57 | 2.22 | 1.95–2.53 |

| Death/MI/Stroke/Revascularization | Ref. | 1.37 | 1.16–1.62 | 2.36 | 2.08–2.67 |

| (B) Partially-Adjusteda Hazard Ratios (Model 2) | |||||

| Outcomes | DL-CAC=0 | DL-CAC=1–99 | DL-CAC≥100 | ||

| HR | 95% CI | HR | 95% CI | ||

| Death | Ref. | 1.19 | 0.98–1.43 | 1.73 | 1.47–2.04 |

| Death/MI/Stroke | Ref. | 1.19 | 0.99–1.42 | 1.78 | 1.52–2.09 |

| Death/MI/Stroke/Revascularization | Ref. | 1.24 | 1.04–1.48 | 1.92 | 1.64–2.24 |

| (C) Fully-Adjustedb Hazard Ratios (Model 3) | |||||

| Outcomes | DL-CAC=0 | DL-CAC=1–99 | DL-CAC≥100 | ||

| HR | 95% CI | HR | 95% CI | ||

| Death | Ref. | 1.13 | 0.94–1.36 | 1.51 | 1.28–1.79 |

| Death/MI/Stroke | Ref. | 1.13 | 0.94–1.36 | 1.57 | 1.33–1.84 |

| Death/MI/Stroke/Revascularization | Ref. | 1.18 | 0.99–1.41 | 1.69 | 1.45–1.98 |

Adjusted on age and sex.

Adjusted on age, sex, race, ethnicity, comorbidities (measured by Elixhauser Comorbidity Index), and pooled cohort equations variables (systolic blood pressure, total cholesterol level, HDL cholesterol level, diabetes status, smoking status, and anti-hypertensive use).

CI = confidence interval; HR = hazard ratio; MI = myocardial infarction; PCE = pooled cohort equations; Ref. = reference. n=5,678 total patients in each analysis.

Central Illustration – Incidental CAC on Non-ECG-Gated CTs and Cardiovascular Events and Mortality.

aAdjusted on age, sex, race, ethnicity, comorbidities (measured by Elixhauser Comorbidity Index), and pooled cohort equations variables (systolic blood pressure, total cholesterol level, HDL cholesterol level, diabetes status, smoking status, and anti-hypertensive use). ASCVD = atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease; CI = confidence interval; CVD = cardiovascular disease; HR = hazard ratio; MI = myocardial infarction; PCE = pooled cohort equations.

DISCUSSION:

In this diverse, real-world cohort in a large academic healthcare system, we established the association between incidental CAC, quantified using a DL algorithm on non-ECG-gated chest CTs, and adverse cardiovascular outcomes and death. We found that patients with any incidental CAC as measured by the DL algorithm had worse all-cause mortality and adverse cardiovascular outcomes than those without CAC. Furthermore, patients with DL-CAC ≥100 had over two times increased risk of mortality compared to those with DL-CAC=0. Their risk was even greater when including non-fatal cardiovascular events such as MI, stroke, and revascularization. The predictive significance of DL-CAC persisted after controlling for traditional risk factors, emphasizing that DL-CAC provides additive prognostic information for cardiovascular events and mortality over data collected as part of routine care. Our study uniquely utilizes a fully-automated end-to-end DL algorithm validated on paired gated and non-ECG-gated scans7 to quantify incidental CAC on non-ECG-gated, non-contrast chest CT scans performed for any indication across diverse practice settings.

Prior studies have demonstrated that incidentally identified CAC on non-ECG-gated chest CT imaging is associated with cardiovascular events and mortality.9–14 However, these studies were limited in generalizability because their study cohorts consisted of specific populations of higher-risk individuals: those in lung cancer screening trials, those with primary severe hypercholesterolemia (low-density lipoprotein-C≥190 mg/dL), or cohorts of hospital inpatients only.9–14 Our study was comprised of a diverse group of patients (51% women, 18% Asian, and 13% Hispanic/Latinx) and with CT scans performed for various indications across all practice settings (Central Illustration).

Given the accuracy of non-ECG-gated CTs in detecting CAC and evidence of the utility of incidental CAC in risk prediction, the American College of Radiology Incidental Findings Committee and guidelines from the Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography recommend reporting CAC scores on all non-ECG-gated chest CTs.16, 17 However, this has not been implemented consistently in clinical practice.18–20 Routine CAC scoring on non-ECG-gated chest CTs is further limited by manual quantification, requiring additional time that is not always feasible for radiologists. AI algorithms, such as DL models, represent a solution to the manual identification and quantification of incidental CAC and thus are an untapped resource for opportunistic CAC screening to identify individuals who may be at higher risk for ASCVD and mortality.

While ECG-gated CT scans have traditionally been the gold-standard for quantifying CAC, there are also barriers to routine use, such as the amount of resources required to perform them.31, 32 Additionally, there is wide disparity in the availability and pricing of these ECG-gated scans, which have been shown to directly correlate with socioeconomic and healthcare disparities in the U.S.33 In contrast, non-ECG-gated, non-contrast chest CTs, which require far fewer resources to perform and are more widely accessible, have been shown to detect CAC with similar accuracy as ECG-gated CT scans, allowing for greater equity in access to CAC measurement tools.34–40 For example, almost 9 million U.S. adults are recommended for lung cancer screening with non-ECG-gated chest CTs each year.41 This is just one avenue in which individuals undergoing CT scans for non-cardiovascular purposes can find additional benefit from simultaneous opportunistic CAC screening. Our study demonstrates the feasibility of a fully-automated method to provide additional prognostic information on CT scans performed for various clinical reasons in an equitable way, increasing the diversity of individuals able to undergo opportunistic screening and earlier preventive intervention. Compared with prior published algorithms, we used a more robust, clinically accepted gold standard to validate our algorithm. Specifically, our algorithm was externally validated on paired ECG-gated coronary CT imaging as a reference standard, while others were validated on manual quantitation performed on non-ECG-gated imaging, which is not the gold-standard for CAC measurement.15, 42, 43

By leveraging AI to opportunistically screen for CAC, high-risk individuals can be identified earlier and be offered appropriate preventive therapies. In fact, in a study of 173 primary prevention patients, our group has demonstrated that notifying patients and clinicians of the presence of incidental CAC to patients and clinicians dramatically increases statin prescription rates.44 This is in line with other studies that have shown that visualization and recognition of one’s CAC improves medication adherence and can be utilized as a tool to guide shared decision-making.45, 46 In addition to the equity chasm, there is a known quality gap related to undertreatment of high-risk individuals with statin therapy.47–52 Consistent with the literature, we also found marked underutilization of statins in primary prevention patients at high risk for ASCVD. In our study, individuals with DL-CAC ≥100 had an average 10-year ASCVD risk estimate of 24%, meaning they were known to be high-risk and met ACC/AHA guideline recommendations for statin initiation.26 Despite this, only one quarter were prescribed statins. Taken together, this highlights the opportunity to identify high-risk individuals, implement preventive therapies, and substantially reduce mortality and cardiovascular morbidity with opportunistic incidental CAC screening.

Limitations

Our results should be interpreted in the context of several limitations. First, our study analyzed incidental CAC only on chest CT imaging performed at a single institution. However, our chest CTs were performed in diverse locations including the emergency department, outpatient, and inpatient settings on different models of scanners. Second, there was a sizeable number of missing values for variables used for the PCE calculation, which may lead to bias. We accounted for this missingness with multiple imputation and found similar results with a complete case analysis (Supplemental Table 3).29, 30 Third, those undergoing chest CT scans may not be representative of the general US asymptomatic primary prevention population, as they may be a sicker cohort at higher risk of mortality from non-cardiovascular causes, such as cancer. Nonetheless, the leading cause of death in the National Lung Screening Trial was not lung cancer but rather cardiovascular disease, so it is reasonable to hypothesize that individuals identified to have incidental CAC may benefit from pre-clinical detection and early intervention.53 Fourth, there is potential bias from excluding persons without prior or post encounters from date of CT imaging and that some of these individuals may be healthier than those included in our study. Importantly, the results of this study only apply to those who met inclusion criteria, as we excluded those without pre-CT encounters to ensure availability of baseline data, and we excluded those without post-CT encounters to ensure availability of adequate follow-up data and minimize incomplete event ascertainment. Fifth, because our data were limited to a single institution without access to data from external healthcare sites, there may be missed events that we could not account for in our analyses. Finally, non-cardiovascular death may comprise a sizeable portion of the observed mortality, which would lessen the association between DL-CAC and ASCVD-related mortality. Although we adjusted for variables used in the PCE, our outcomes are not directly comparable to 10-year ASCVD risk as our outcomes included all-cause mortality. Thus, our absolute event rates are not estimates of ASCVD risk. Further research is needed to determine whether DL-CAC is predictive of both fatal and nonfatal ASCVD events.

Conclusions

In this study, a fully-automated deep-learning algorithm7 was used to quantify incidental CAC on non-ECG-gated CT scans performed for various indications across diverse populations. The presence of any DL-CAC was associated with worse outcomes, and DL-CAC ≥100 Agatston units was consistently associated with worse all-cause mortality and adverse cardiovascular outcomes with improved risk stratification beyond traditional cardiovascular risk factors and variables used in the PCE. Population-wide opportunistic screening for CAC may have the potential to significantly advance preventive care by identifying patients who may be at increased cardiovascular and mortality risk and facilitating earlier preventive intervention.

Supplementary Material

PERSPECTIVES.

Competency in Patient Care and Procedural Skills:

Coronary artery calcium (CAC) detected by non-ECG-gated chest CT imaging performed for other reasons can be quantified using artificial intelligence and is associated with an increased risk of adverse cardiovascular events and all-cause mortality.

Translational Outlook:

Population-wide opportunistic screening for incidental CAC on non-ECG-gated chest CT scans could identify patients at increased cardiovascular risk and facilitate preventive intervention.

Funding:

This work was supported by the Stanford University Human-Centered Artificial Intelligence Seed Grant. AC receives research support from the Stanford University Precision Health and Integrated Diagnostics Seed Grant and the Stanford University Human-Centered Artificial Intelligence – Artificial Intelligence in Medicine and Imaging Seed Grant. FR was funded by grants from the NIH National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (1K01HL144607), the American Heart Association/Harold Amos Faculty Development program, and the Doris Duke Foundation (Grant #2022051). AS receives research support from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (1K23HL151672-01).

Abbreviations:

- ACC

American College of Cardiology

- AHA

American Heart Association

- CAC

coronary artery calcium

- DL

deep-learning

- ASCVD

atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease

- AI

artificial intelligence

- EHR

electronic health record

- ICD

International Classification of Diseases

- HCPCS

healthcare common procedure coding system

- MI

myocardial infarction

- PCE

pooled cohort equations

Footnotes

Tweet: Incidental CAC≥100 quantified on non-gated CT using an AI algorithm was associated with worse CVD and mortality outcomes, beyond traditional risk factors and the PCE. Suggests value in population-wide opportunistic screening for ASCVD with incidental CAC. #ACCPrev #CAC #CVD (Character count including spaces: 274/280)

Disclosures: FR reports consulting relationships with Healthpals, Novartis, NovoNordisk, and AstraZeneca outside the submitted work. DE and NK are employees and shareholders of Bunkerhill Health. AC has provided consulting services to Subtle Medical, Chondrometrics GmbH, Image Analysis Group, Edge Analytics, ICM, and Culvert Engineering; is a shareholder of Subtle Medical, LVIS Corporation, and Brain Key; and receives research support from GE Healthcare and Philips; all outside the submitted work. The remaining authors have no disclosures to report.

REFERENCES:

- 1.Virani SS, Alonso A, Aparicio HJ, et al. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics—2021 Update. Circulation. 2021;143:e254–e743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yusuf S, Hawken S, Ounpuu S, et al. Effect of potentially modifiable risk factors associated with myocardial infarction in 52 countries (the INTERHEART study): case-control study. Lancet. 2004;364:937–952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Budoff MJ, Young R, Burke G, et al. Ten-year association of coronary artery calcium with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) events: the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis (MESA). Eur Heart J. 2018;39:2401–2408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Peng AW, Dardari ZA, Blumenthal RS, et al. Very high coronary artery calcium (CAC ≥ 1000) and association with CVD events, non-CVD outcomes, and mortality: Results from the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA). Circulation. 2021: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.050545. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Peng AW, Mirbolouk M, Orimoloye OA, et al. Long-term all-cause and cause-specific mortality in asymptomatic patients with CAC ≥ 1000: Results from the Coronary Artery Calcium Consortium. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2020;13:83–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miedema MD, Dardari ZA, Nasir K, et al. Association of Coronary Artery Calcium With Long-term, Cause-Specific Mortality Among Young Adults. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2:e197440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eng D, Chute C, Khandwala N, et al. Automated coronary calcium scoring using deep learning with multicenter external validation. npj Digit Med. 2021;4:1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Budoff MJ, Lutz SM, Kinney GL, et al. Coronary Artery Calcium on Noncontrast Thoracic Computerized Tomography Scans and All-Cause Mortality. Circulation. 2018;138:2437–2438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Takx RAP, Išgum I, Willemink MJ, et al. Quantification of coronary artery calcium in nongated CT to predict cardiovascular events in male lung cancer screening participants: results of the NELSON study. J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr. 2015;9:50–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chiles C, Duan F, Gladish GW, et al. Association of Coronary Artery Calcification and Mortality in the National Lung Screening Trial. Radiology. 2015;276:82–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jacobs PC, Gondrie MJA, van der Graaf Y, et al. Coronary artery calcium can predict all-cause mortality and cardiovascular events on low-dose CT screening for lung cancer. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2012;198:505–511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mets OM, Vliegenthart R, Gondrie MJ, et al. Lung cancer screening CT-based prediction of cardiovascular events. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2013;6:899–907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yu C, Ng ACC, Ridley L, et al. Incidentally identified coronary artery calcium on non-contrast CT scan of the chest predicts major adverse cardiac events among hospital inpatients. Open Heart. 2021;8:e001695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Castagna F, Miles J, Arce J, et al. Visual Coronary and Aortic Calcium Scoring on Chest Computed Tomography Predict Mortality in Patients With Low-Density Lipoprotein-Cholesterol ≥190 mg/dL. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2022;15:e014135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wetscherek MTA, McNaughton E, Majcher V, et al. Incidental coronary artery calcification on non-gated CT thorax correlates with risk of cardiovascular events and death. Eur Radiol. 2023:1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hecht HS, Cronin P, Blaha MJ, et al. 2016 SCCT/STR guidelines for coronary artery calcium scoring of noncontrast noncardiac chest CT scans: A report of the Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography and Society of Thoracic Radiology. J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr. 2017;11:74–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Munden RF, Carter BW, Chiles C, et al. Managing Incidental Findings on Thoracic CT: Mediastinal and Cardiovascular Findings. A White Paper of the ACR Incidental Findings Committee. J Am Coll Radiol. 2018;15:1087–1096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kirsch J, Martinez F, Lopez D, Novaro GM, Asher CR. National trends among radiologists in reporting coronary artery calcium in non-gated chest computed tomography. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2017;33:251–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Balakrishnan R, Nguyen B, Raad R, et al. Coronary artery calcification is common on nongated chest computed tomography imaging. Clin Cardiol. 2017;40:498–502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Secchi F, Di Leo G, Zanardo M, Alì M, Cannaò PM, Sardanelli F. Detection of incidental cardiac findings in noncardiac chest computed tomography. Medicine (Baltimore). 2017;96:e7531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ward A, Sarraju A, Chung S, et al. Machine learning and atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk prediction in a multi-ethnic population. npj Digit Med. 2020;3:1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lassau N, Ammari S, Chouzenoux E, et al. Integrating deep learning CT-scan model, biological and clinical variables to predict severity of COVID-19 patients. Nat Commun. 2021;12:634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Goldstein BA, Navar AM, Carter RE. Moving beyond regression techniques in cardiovascular risk prediction: applying machine learning to address analytic challenges. Eur Heart J. 2017;38:1805–1814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bild DE, Bluemke DA, Burke GL, et al. Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis: objectives and design. Am J Epidemiol. 2002;156:871–881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Goff DC, Lloyd-Jones DM, Bennett G, et al. 2013 ACC/AHA Guideline on the Assessment of Cardiovascular Risk. Circulation. 2014;129:S49–S73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Grundy SM, Stone NJ, Bailey AL, et al. 2018 AHA/ACC/AACVPR/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/ADA/AGS/APhA/ASPC/NLA/PCNA Guideline on the Management of Blood Cholesterol: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;73:e285–e350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Grundy SM, Stone NJ, Bailey AL, et al. 2018 AHA/ACC/AACVPR/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/ADA/AGS/APhA/ASPC/NLA/PCNA Guideline on the Management of Blood Cholesterol: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2019;139:e1082–e1143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Orringer CE, Blaha MJ, Blankstein R, et al. The National Lipid Association scientific statement on coronary artery calcium scoring to guide preventive strategies for ASCVD risk reduction. J Clin Lipidol. 2021;15:33–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li P, Stuart EA, Allison DB. Multiple Imputation: A Flexible Tool for Handling Missing Data. JAMA. 2015;314:1966–1967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sterne JAC, White IR, Carlin JB, et al. Multiple imputation for missing data in epidemiological and clinical research: potential and pitfalls. BMJ. 2009;338:b2393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Machida H, Tanaka I, Fukui R, et al. Current and Novel Imaging Techniques in Coronary CT. Radiographics. 2015;35:991–1010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mahabadi AA, Achenbach S, Burgstahler C, et al. Safety, efficacy, and indications of beta-adrenergic receptor blockade to reduce heart rate prior to coronary CT angiography. Radiology. 2010;257:614–623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ikram M, Williams KA. Socioeconomics of coronary artery calcium: Is it scored or ignored? J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr. 2022;16:182–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Polonsky TS, Greenland P. Coronary Artery Calcium Scores Using Nongated Computed Tomography. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2013;6:494–495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shin JM, Kim TH, Kim JY, Park CH. Coronary artery calcium scoring on non-gated, non-contrast chest computed tomography (CT) using wide-detector, high-pitch and fast gantry rotation: comparison with dedicated calcium scoring CT. J Thorac Dis. 2020;12:5783–5793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Xie X, Zhao Y, de Bock GH, et al. Validation and prognosis of coronary artery calcium scoring in nontriggered thoracic computed tomography: systematic review and meta-analysis. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2013;6:514–521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Budoff MJ, Nasir K, Kinney GL, et al. Coronary Artery and Thoracic Calcium on Non-contrast Thoracic CT Scans: Comparison of Ungated and Gated Examinations in Patients from the COPD Gene Cohort. J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr. 2011;5:113–118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kirsch J, Buitrago I, Mohammed T-LH, Gao T, Asher CR, Novaro GM. Detection of coronary calcium during standard chest computed tomography correlates with multi-detector computed tomography coronary artery calcium score. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2012;28:1249–1256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Obisesan OH, Osei AD, Uddin SMI, Dzaye O, Blaha MJ. An Update on Coronary Artery Calcium Interpretation at Chest and Cardiac CT. Radiol Cardiothorac Imaging. 2021;3:e200484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hughes-Austin JM, Dominguez A, Allison MA, et al. Relationship of Coronary Artery Calcium on Standard Chest Computed Tomography Scans with Mortality. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2016;9:152–159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ma J, Ward EM, Smith R, Jemal A. Annual number of lung cancer deaths potentially avertable by screening in the United States. Cancer. 2013;119:1381–1385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Isgum I, Prokop M, Niemeijer M, Viergever MA, van Ginneken B. Automatic Coronary Calcium Scoring in Low-Dose Chest Computed Tomography. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2012;31:2322–2334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shadmi R, Mazo V, Bregman-Amitai O, Elnekave E. Fully-convolutional deep-learning based system for coronary calcium score prediction from non-contrast chest CT. In: 2018 IEEE 15th International Symposium on Biomedical Imaging (ISBI 2018)., 2018:24–28. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sandhu AT, Rodriguez F, Ngo S, et al. Incidental Coronary Artery Calcium: Opportunistic Screening of Prior Non-gated Chest CTs to Improve Statin Rates (NOTIFY-1 Project). Circulation. 2023;147:703–714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Näslund U, Ng N, Lundgren A, et al. Visualization of asymptomatic atherosclerotic disease for optimum cardiovascular prevention (VIPVIZA): a pragmatic, open-label, randomised controlled trial. The Lancet. 2019;393:133–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mamudu HM, Paul TK, Veeranki SP, Budoff M. The effects of coronary artery calcium screening on behavioral modification, risk perception, and medication adherence among asymptomatic adults: a systematic review. Atherosclerosis. 2014;236:338–350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chobufo MD, Regner SR, Zeb I, Lacoste JL, Virani SS, Balla S. Burden and predictors of statin use in primary and secondary prevention of atherosclerotic vascular disease in the US: from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2017–2020. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2022;29:1830–1838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Metser G, Bradley C, Moise N, Liyanage-Don N, Kronish I, Ye S. Gaps and Disparities in Primary Prevention Statin Prescription During Outpatient Care. Am J Cardiol. 2021;161:36–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Saeed A, Zhu J, Thoma F, et al. Cardiovascular Disease Risk–Based Statin Utilization and Associated Outcomes in a Primary Prevention Cohort: Insights From a Large Health Care Network. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2021;14:e007485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rodriguez F, Olufade TO, Ramey DR, et al. Gender Disparities in Lipid-Lowering Therapy in Cardiovascular Disease: Insights from a Managed Care Population. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2016;25:697–706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rodriguez F, Lin S, Maron DJ, Knowles JW, Virani SS, Heidenreich PA. Use of high-intensity statins for patients with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease in the Veterans Affairs Health System: Practice impact of the new cholesterol guidelines. Am Heart J. 2016;182:97–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Spencer-Bonilla G, Chung S, Sarraju A, Heidenreich P, Palaniappan L, Rodriguez F. Statin Use in Older Adults with Stable Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2021;69:979–985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.de Koning HJ, van der Aalst CM, de Jong PA, et al. Reduced Lung-Cancer Mortality with Volume CT Screening in a Randomized Trial. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:503–513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.