Abstract

Viral protein U (Vpu) is a protein encoded by human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) that promotes the degradation of the virus receptor, CD4, and enhances the release of virus particles from cells. We isolated a cDNA that encodes a novel cellular protein that interacts with Vpu in vitro, in vivo, and in yeast cells. This Vpu-binding protein (UBP) has a molecular mass of 41 kDa and is expressed ubiquitously in human tissues at the RNA level. UBP is a novel member of the tetratricopeptide repeat (TPR) protein family containing four copies of the 34-amino-acid TPR motif. Other proteins that contain TPR motifs include members of the immunophilin superfamily, organelle-targeting proteins, and a protein phosphatase. UBP also interacts directly with HIV-1 Gag protein, the principal structural component of the viral capsid. However, when Vpu and Gag are coexpressed, stable interaction between UBP and Gag is diminished. Furthermore, overexpression of UBP in virus-producing cells resulted in a significant reduction in HIV-1 virion release. Taken together, these data indicate that UBP plays a role in Vpu-mediated enhancement of particle release.

Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) is a member of the lentivirus subfamily of retroviruses. Like all retroviruses, lentiviruses encode the gag, pol, and env genes. However, lentiviruses also contain several accessory genes. The accessory gene vpu, which is unique to HIV-1, encodes viral protein U (Vpu) (44), a 16-kDa type I integral membrane phosphoprotein that can form oligomeric structures in vitro and in vivo (32, 43). Indirect immunofluorescence indicates that Vpu localizes predominantly to the Golgi complex (29), but some Vpu is also present in association with the plasma membrane (17). The protein contains a hydrophobic N-terminal domain, which serves as the membrane anchor, and a C-terminal hydrophilic cytoplasmic domain (32).

Vpu plays two roles in HIV-1 replication. First, Vpu promotes the specific degradation of the HIV-1 receptor, CD4, in cell-free systems (8) and in vivo (41, 47). Degradation of CD4 enhances the transport and subsequent processing of the HIV-1 envelope glycoprotein by releasing it from complexes with CD4 that trap both proteins in the endoplasmic reticulum (28). Direct interaction of Vpu with the cytoplasmic domain of CD4 is required, but not sufficient, for CD4 degradation (4). Mutational analysis indicates that the hydrophilic cytoplasmic domain of Vpu is required for Vpu-mediated CD4 degradation (40). The second function of Vpu is the enhancement of virus particle release (19, 29, 43, 45, 48). The effect of Vpu on virus particle release appears to be mediated from a post-endoplasmic reticulum compartment (41). Whereas the cytoplasmic domain of Vpu is important for the degradation of CD4, the transmembrane domain of Vpu is sufficient for partial enhancement of virus release (40). Thus, based on both differential intracellular site of action and genetic criteria, the bipartite roles of Vpu are mechanistically distinct. The HIV-1 Gag protein is sufficient for immature virus capsid formation, and those capsids are fully competent for Vpu-mediated enhancement of release, indicating that an eventual target of Vpu during particle release is intrinsic to Gag (30).

The identification of host cell proteins that function in HIV replication has provided crucial insight into the intricacies of the biology of HIV-1. The identification of CD4 as the principal virus receptor on T cells has provided a basic paradigm for virus entry (10). Chemokine receptors are proteins involved in chemotaxis of immune system cells and have been co-opted by HIV-1 to allow entry into host cells in conjunction with CD4 (2, 13). Urokinase-type plasminogen activator, a proteinase involved in tissue invasion by macrophages, binds to and cleaves the HIV-1 envelope glycoprotein gp120 and enhances the infectivity of HIV-1 in macrophages (24). Cyclophilins are proteins that bind to the immunosuppressive drug cyclosporin A (CsA) and are members of the immunophilin superfamily, which includes members that facilitate protein folding (18). Cyclophilins A, B, and C interact with HIV-1 Gag, and cyclophilin A is incorporated into virions (15, 31, 46). The incorporation of cyclophilin A into virus particles is required for an early step in replication between membrane fusion and reverse transcription (5). Furin, a subtilisin-like endoprotease, mediates the cleavage of the HIV-1 envelope glycoprotein precursor gp160 to gp120 and gp41, a process required for virus infectivity (22).

We used a yeast two-hybrid system to screen a CD4-negative B-lymphocyte cDNA expression library for cellular proteins capable of interacting with Vpu. The principal cDNA that resulted from this screen is a novel cDNA which encodes a 41-kDa protein that is widely expressed on the mRNA level in human tissues. The protein contains four copies of a 34-amino-acid repeat motif called the tetratricopeptide repeat (TPR). The TPR family of proteins is composed of proteins of very diverse function including organelle-targeting proteins (11, 25), proteins involved in mitosis (26, 42), immunophilins (6, 36), and a nuclear phosphatase (7). Our results indicate that this novel Vpu-binding protein (UBP) functionally interacts with both Vpu and Gag. UBP appears to be an intermediary between Vpu and Gag and likely plays a role in virus assembly or release.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

DNA constructions.

To construct pKT106, the vpu gene was amplified from pGB107 (16), a derivative of the HIV-1 infectious molecular clone pNL4-3 (1), using the primers vpu1 (5′-AGTAGTACATCATATGCAACCTA-3′) and vpu2 (5′-TCCACACAGGATCCCCATAAT-3′). The 308-bp amplification product was gel purified and digested with NdeI and BamHI and cloned into plasmid pAS1-CYH2 (a derivative of pAS1 [12] containing a cycloheximide sensitivity gene) that had also been cut with NdeI and BamHI. pVpui9-1 is a two-hybrid system library plasmid containing the ubp cDNA with a complete 5′ end. Sequence analysis of five ubp cDNAs indicated that the cDNA from pVpui9-1 is missing 47 bp of the 3′ untranslated region including the polyadenylation signal and the poly(A) tail. The sequence in Fig. 1 is derived from the cDNA insert of pVpui9-1 plus the 47 bp of the 3′ end from the other cDNAs. pKT173 was constructed by cloning a 1,412-bp XhoI-PstI fragment of pVpui9-1 containing the entire ubp coding region into pCITE-2a (Novagen) cut with XhoI and PstI. pKT199, which expresses Vpu in a coupled in vitro transcription-translation system, was created by inserting a 310-bp NdeI-BamHI fragment from pKT106 into pCITE-2a cut with NdeI and BglII. pGEX-UBP was created by inserting a 2,204-bp XhoI fragment from pVpui9-1 into the SalI site of pGEX-4T-1 (Pharmacia). pHIV-UBP, which expresses UBP from the HIV-1 long terminal repeat (LTR), was created by cloning a 1,705-bp XhoI-NruI fragment from pVpui9-1 containing the entire ubp coding region into pBG139 (19) that had been cut by SalI and StuI. pJL90 was constructed by amplifying the gag gene from pNL4-3 with the primers 1 (5′-CGGGATCCGGTGCGAGAGCGTCGGTATTAAG-3′) and 2 (5′-GCTCTAGACCTGTATCTAATAGAGCTTC-3′). The PCR product was gel purified, digested with BamHI and XbaI, and inserted into pQE30 (Qiagen) that had been cut with the same two enzymes. pHIVTF(stop), which contains a mutation that creates a premature stop codon immediately following the second amino acid of the trans-frameshift peptide, was constructed by PCR amplification of pMSMΔEnv2 (33) with the sense primer 23233 (5′-GGCCAGATGAGAGAACCAAGG) and the antisense mismatch primer 8264 AflII (5′-CAAAGAGTGACTTAAGGGAAGCTAAAG). A second fragment was derived from the PCR amplification of pMSMΔEnv2 with the antisense primer 23234 (5′-CCTATAGCTTTATGTCCGCAG) and the sense mismatch primer 8265 AflII (5′-CTTTAGCTTCCCTTAAGTCACTCTTTG). These fragments were digested with AflII, ligated, and reamplified with the primers 23233 and 23234. The amplified fragment was digested with SpeI and BclI, and this 922-bp fragment was ligated into pMSMΔEnv2 that had also been digested with SpeI and BclI. pHJ121 was constructed by introducing the SalI-NheI fragment of pBG135 (19) containing the mutated vpu gene into pHIVTF(stop) that had also been cut with SalI and NheI.

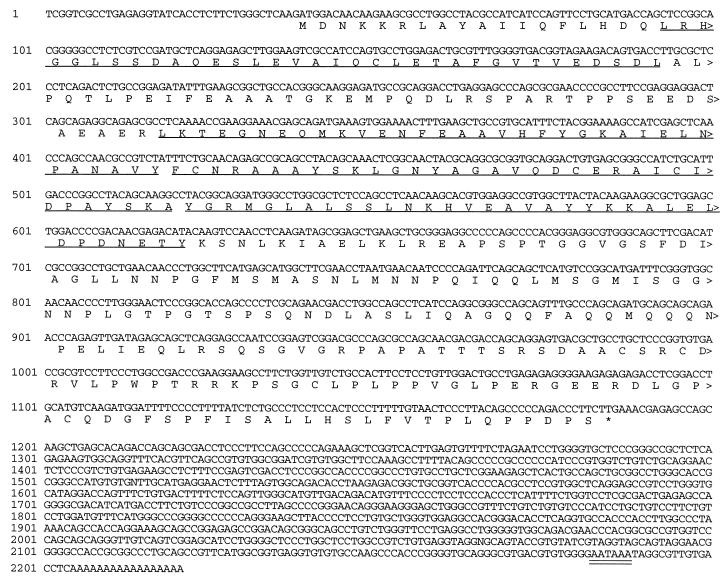

FIG. 1.

Sequence of the ubp coding region and flanking untranslated regions. The complete nucleotide sequence of the longest ubp cDNA obtained from the two-hybrid system Vpu screen is shown with the deduced amino acid sequence of the open reading frame. Numbers to the left of each line designate nucleotide positions. The four TPR motifs are underlined, and the polyadenylation signal is double underlined.

Two-hybrid system library screen.

Saccharomyces cerevisiae Y190 (MATa leu2-3,112 ura3-52 trp1-901 his3-200 ade2-101 lys2-801 gal4Δ gal80Δ URA3::GAL-lacZ LYS2::GAL-HIS3 cyhr) was first transformed to Trp prototrophy with pKT106, which expresses Vpu fused to the GAL4 DNA-binding domain (DBD). Cells containing this plasmid were grown in Trp-minus synthetic complete medium and transformed with a human B-lymphocyte cDNA library cloned into a plasmid called pACT (12), which expresses the various cDNA-encoded proteins as hybrids with the GAL4 transcriptional activation domain. Transformations were performed as previously described (39). Doubly transformed yeast cells were grown on synthetic complete medium lacking His, Leu, and Trp (37) and containing 25 mM 3-amino-1,2,4-triazole (Sigma), and yeast colonies that grew were subjected to a 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactopyranoside (X-Gal) colony filter assay (12). The cDNA-containing plasmids from His+ colonies that stained blue in the X-Gal assay were isolated and tested for the ability to activate transcription alone, and those that did were discarded as false positives. Positive candidate clones were analyzed by restriction digestion and sequencing.

In vitro protein binding assays.

For the glutathione S-transferase (GST)-UBP/Vpu binding assay, GST and a GST-UBP fusion protein were expressed in Escherichia coli, using plasmids pGEX-2T and pGEX-UBP, respectively. The proteins were purified by using glutathione-Sepharose (Pharmacia) according to the manufacturer’s directions. Protein concentration was quantified using the Bradford assay (Bio-Rad). Vpu was expressed from plasmid pKT199, using the TnT rabbit reticulocyte lysate in vitro transcription-translation system (Promega) according to the manufacturer’s directions. Reactions were performed in the presence of 23 μCi of Tran35S-label (ICN) to radioactively label the protein. Multiple 25-μl reactions were performed and pooled after the incubation period. Twenty microliters of pooled Vpu was mixed with 30 pmol of either GST alone or GST-UBP, and the binding reaction mixtures were brought to a total volume of 200 μl with binding buffer (50 to 200 mM NaCl, 20 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.9], 1 mM EDTA, 5% glycerol, 0.02% Nonidet P-40 [NP-40], 2 μg of leupeptin per ml, 100 μg of phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride [PMSF] per ml, 0.05% bovine serum albumin [BSA]). Binding reaction mixtures were incubated on a rocking platform at 4°C for 2 h and then at room temperature for 1 h. A 25-μl bed volume of glutathione-Sepharose beads was added to each reaction mixture, and the reaction mixtures were incubated for an additional 2 h at room temperature on a rocking platform. Beads were washed three times in 1 ml of binding buffer and resuspended in 30 μl of standard sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) protein sample buffer. Samples were heated in a boiling water bath for 4 min, spun at 14,000 rpm in a microcentrifuge for 5 min, and loaded onto a SDS–15% polyacrylamide gel.

For the GST-UBP/Gag interaction assay using Gag expressed in bacteria, His-tagged HIV-1 Gag precursor and a GST-UBP fusion protein were expressed in E. coli, using plasmids pJL90 and pGEX-UBP, respectively. Protein was induced from bacterial expression plasmids with isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside according to standard methods (38). Bacteria were pelleted 2 h after induction, washed with TEK buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, 100 mM KCl, 1 mM EDTA [pH 7.4]) once, and then resuspended in lysis buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, 100 mM KCl, 1 mM EDTA, 5 mM dithiothreitol, 1 mM PMSF, 0.5% NP-40 [pH 7.4]). The bacterial pellets were freeze-thawed and sonicated four times for 15 s each. Insoluble material was pelleted by centrifugation for 10 min in a microcentrifuge at 14,000 rpm. Total protein concentrations in the supernatants were determined by the Bradford dye-binding procedure (Bio-Rad). Supernatants were adjusted to 20% glycerol and stored at −80°C. His-tagged Gag protein (approximately 0.1 μM) was incubated with GST-UBP fusion protein or GST protein (approximately 0.5 μM) in 300 μl of Triton buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, 300 mM NaCl, 0.5% Triton X-100 [pH 7.4]) at 4°C on a rocking platform for 1 h. After incubation, a 50-μl bed volume of glutathione-Sepharose beads (Pharmacia) was added to each reaction mixture, and the incubation was continued for another half hour. Glutathione-Sepharose beads were pelleted by a 10-s centrifugation in a microcentrifuge and then washed three times with 500 μl of Triton buffer. Washed glutathione-Sepharose beads were resuspended with 20 μl of 4× protein sample buffer (8% SDS, 50 mM Tris, 40% glycerol, 24.8 mg of dithiothreitol per ml, 0.4% bromophenol blue, 5% 2-mercaptoethanol [pH 6.8]), adjusted to a final volume of 80 μl, and then heated in a boiling water bath for 5 min. After the beads were pelleted in a microcentrifuge, the supernatants were subjected to SDS-PAGE and Western blot analysis using anti-Gag polyclonal antiserum.

For the GST-UBP/Gag binding assays using Gag expressed in HeLa cells, cells were maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium containing 7% calf serum. One day before transfection, 0.8 million cells were seeded onto 100-mm-diameter dishes. HeLa cells were transfected by calcium phosphate coprecipitation followed by glycerol shock with either a vpu+ protease− proviral construct [pHIVTF(stop)] or a vpu− protease− proviral construct (pHJ121). At 48 to 60 h posttransfection, cells were washed once with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and lysed with 150 μl of Triton lysis buffer (0.5% Triton X-100, 50 mM Tris, 300 mM NaCl [pH 7.5]). After incubation on ice for 30 min, lysates were spun at 7,000 rpm for 6 min to pellet cell debris, and supernatants were transferred to new tubes and stored at −20°C. Gag concentrations were determined by using a p24 antigen-capture enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit (Coulter Corporation). Conditions for the binding assay were the same as those described above for the binding assay with bacterially expressed Gag protein.

Immunoaffinity column chromatography.

An immunoaffinity column was constructed by using Affi-Gel 10 (Bio-Rad) and purified immunoglobulin G (IgG) from rabbit serum raised against His-UBP. IgG was coupled to the matrix in coupling buffer (0.1 M HEPES [pH 8.0]) at 4°C for 4 h, placed in a glass column, and washed extensively with column wash buffer (10 mM sodium phosphate [pH 6.8]). HeLa cells were washed twice with PBS then lysed with cell lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.4], 300 mM NaCl, 10 mM iodoacetamide, 0.5% Triton X-100, 0.2 mM PMSF, 0.5 mM leupeptin). Cell lysates were placed on the column by gravity flow, and the column was washed with 10 bed volumes of wash buffer. Bound protein was eluted with 100 mM glycine (pH 2.5), and 1-ml fractions were collected. Fractions containing protein, determined by optical density at 280 nm, were pooled and concentrated to a 100-μl volume in Centricon concentrators (Amicon). These fractions were then analyzed by Western blotting for UBP and Vpu.

Northern blotting.

Twenty-five nanograms of either a 2-kb human β-actin cDNA or the 2,204-bp XhoI fragment of pVpui9-1 was labeled with [α-32P]dCTP (Amersham), using a random-primed labeling kit (Boehringer Mannheim) according to the manufacturer’s directions. Unincorporated nucleotides were removed from the reactions by using Sephadex G-50 columns (Boehringer Mannheim). All of the labeled probe from each labeling reaction was used in separate hybridization reactions to probe a multiple human tissue Northern blot (MTN Blot II; Clontech) according to the manufacturer’s directions.

Antibody production and purification.

His-tagged UBP, His-tagged HIV-1 Vpu cytoplasmic domain, and His-tagged HIV-1 Gag proteins were expressed in E. coli and purified under denaturing conditions with Ni-nitrilotriacetic acid agarose (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer’s directions. The protein samples were dialyzed overnight against 1× PBS. Dialyzed His-tagged proteins were used to raise polyclonal antiserum in rabbits. Crude anti-Gag serum was used for Gag Western blots. IgG was purified from anti-UBP or anti-Vpu rabbit serum, using DEAE Affi-Gel blue (Bio-Rad) or protein A-agarose (Bio-Rad) according to the manufacturer’s directions. For UBP Western blots, anti-UBP antibodies were further purified with His-UBP immobilized on Ni-nitrilotriacetic acid agarose.

Western blotting.

For detection of UBP or Vpu in mammalian cells, cells were lysed in NP-40 lysis buffer (100 mM NaCl, 20 mM [Tris pH 7.9], 1 mM EDTA, 0.5% NP-40) and subjected to low-speed centrifugation in a microcentrifuge to remove cellular debris. Cleared cell lysates were mixed with standard SDS-PAGE protein sample buffer and were subjected to electrophoresis on a SDS–15% polyacrylamide gel. Immunoaffinity column samples were electrophoresed on a SDS–10 to 20% polyacrylamide gradient gel. Proteins were transferred to an Immobilon-P membrane (Millipore) by using a Mini Trans-Blot electroblotting apparatus (Bio-Rad) in transfer buffer (27.2 mM Tris, 192 mM glycine, 20% methanol) for 2 h at 150-mA constant current at 4°C. Membranes were blocked overnight in blocking buffer (5% dry milk, 20 mM Tris, 0.01% NaN3). Membranes were then incubated in blocking buffer containing a 1:2,000 dilution of an IgG-purified or an antigen affinity-purified rabbit polyclonal UBP antibody or an IgG-purified rabbit polyclonal Vpu antibody for 4 h at room temperature. Membranes were washed three times in wash buffer (20 mM Tris, 100 mM NaCl, 0.3% Tween 20, 0.005% NaN3) and were subsequently incubated in blocking buffer containing a 1:10,000 dilution of an alkaline phosphatase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (γ-chain specific) antibody (Sigma) for 2 h at room temperature. Membranes were washed as before and then incubated in 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolylphosphate–nitroblue tetrazolium (Sigma) for 15 min at room temperature.

Western blot analyses for luciferase were performed as described above except that a 1:5,000 dilution of an antigen affinity-purified antiluciferase rabbit polyclonal antibody (Promega) was used for the primary incubation.

For the GST-UBP/Gag binding assay, proteins from a polyacrylamide gel were transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane by using a Trans-Blot Cell electroblotting apparatus (Bio-Rad). The membrane was blocked in blocking buffer (5% dry milk–3% BSA in PBS) for 40 min and then incubated in PBS containing 5% dry milk and 1% BSA and a 1:200 dilution of a rabbit polyclonal anti-Gag antibody for 1 h. The membrane was washed in 1× wash buffer (0.05% Tween 20 in PBS) for 20 min and incubated in PBS containing 5% dry milk and 1% BSA and a 1:2,500 dilution of a 35S-labeled goat anti-rabbit IgG antibody. Phosphorimage analysis was used for quantitative measurement of Western blots.

DNA sequencing and sequence analysis.

Partial sequencing of cDNAs was performed with a Sequenase dideoxynucleotide sequencing kit (United States Biochemical). The longest ubp cDNA from pVpui9-1 was sequenced in an automatic sequencing apparatus (Applied Biosystems). Sequence similarity searches of the databases were conducted by using the National Center for Biotechnology Information BLAST e-mail server (3). Exact positions of sequence motifs were determined by using the MacVector sequence analysis program (International Biotechnologies) and manual analysis. Sequence identity and similarity was calculated manually or with the Bestfit program from the Wisconsin Genetics Computer Group.

p24 antigen capture ELISA particle release assay.

Triplicate cultures of 5 × 105 HeLa cells were transfected 1 day after plating by calcium phosphate coprecipitation with 1 μg of either pGB108 (an env− derivative of the HIV-1 molecular clone NL4-3 [16]) or pBG135 (a vpu− derivative of GB108 [19]) and 14 μg of either pHIV-UBP or pTAR-luc, a plasmid that expresses firefly luciferase from the HIV-1 LTR. Thirty-six hours after transfection, aliquots of medium were collected and subjected to low-speed centrifugation to remove cell debris, and supernatants were transferred to new tubes. Cells were washed in PBS, scraped into 1 ml of PBS, and transferred to a centrifuge tube. Cells were pelleted in a microcentrifuge at 6,000 rpm for 5 min, and the cell pellets were lysed in 50 μl of NETN buffer (0.5% NP-40, 1 mM EDTA, 20 mM Tris [pH 8.0], 100 mM NaCl). Lysates were subjected to low-speed centrifugation, and supernatants were transferred to new tubes. The amounts of p24 antigen in medium samples and cell lysates were measured by using a p24 antigen capture ELISA (Coulter).

RESULTS

Interaction between Vpu and a novel cellular protein.

Two lines of evidence are consistent with the interaction between Vpu and one or more cellular factors. Vpu can enhance significantly the release of retrovirus particles as divergent as HIV-2, visna virus, and Moloney murine leukemia virus (21), albeit to a lesser extent than HIV-1 particles. In addition, Vpu-mediated enhancement of virus release is cell-type dependent. Vpu is required for efficient release of virus particles from some cells, such as HeLa cells and CD4+ T-lymphocyte cell lines, but not from other cells, such as COS-1 or CV-1 monkey kidney cells (20) or BALB/c murine lymphoblastoma cells (23).

To identify cellular proteins that might play a role in the activities of Vpu, a yeast two-hybrid system (14) was initially used to screen a human, CD4-negative B-lymphocyte cDNA expression library for proteins that interact with Vpu. The two-hybrid system is based on the juxtaposition of the DNA-binding and transcriptional activation domains of the yeast transcription factor GAL4. Vpu was expressed as a fusion protein with the GAL4 DBD, and proteins encoded by the cDNA library were expressed as fusions with the GAL4 activation domain. If a particular cDNA-encoded protein interacts with Vpu, then the two domains of GAL4 are brought into close association, and GAL4 function is restored. This causes the activation of two GAL4-responsive reporter genes integrated into the yeast chromosomes: the his3 gene, which confers on the yeast the ability to grow on media lacking histidine, and the E. coli lacZ gene, which causes the colonies to stain blue in an X-Gal colony filter assay.

We screened 1.5 million yeast transformants in the two-hybrid system for interaction with Vpu and obtained 13 His+ β-galactosidase+ clones. Ruling out false positives on the basis of activation of transcription in the absence of GAL4-DBD-Vpu and other criteria narrowed these down to five candidate cDNA-expressing plasmids. Partial sequence analysis and restriction enzyme analysis indicated that the five cDNAs contain various lengths of the same sequence. The plasmid containing the longest cDNA, designated pVpui9-1, was also tested in the two-hybrid system with plasmids encoding fusion proteins between the GAL4 DBD and two proteins unrelated to Vpu: murine tumor necrosis factor receptor associated factor 2 and human ADP ribosylation factor 1. The protein encoded by the cDNA did not bind to either of these proteins, indicating that the interaction between Vpu and the protein expressed from pVpui9-1 is specific in yeast (data not shown). Figure 1 shows the complete sequence of the longest cDNA. A search of sequence databases found matches only to partial cDNA sequences of unknown function (accession no. Z13137 and D58427), indicating that this is a novel cDNA sequence. We have termed this sequence and the protein that it encodes UBP, for Vpu-binding protein. The ubp coding region is 1,146 bp long, corresponding to a 382-residue protein with a predicted molecular mass of 41.25 kDa. The ubp mRNA contains an exceptionally long 3′ untranslated region of 987 bp. As discussed in more detail below, UBP is a member of the TPR protein family and contains four TPR motifs.

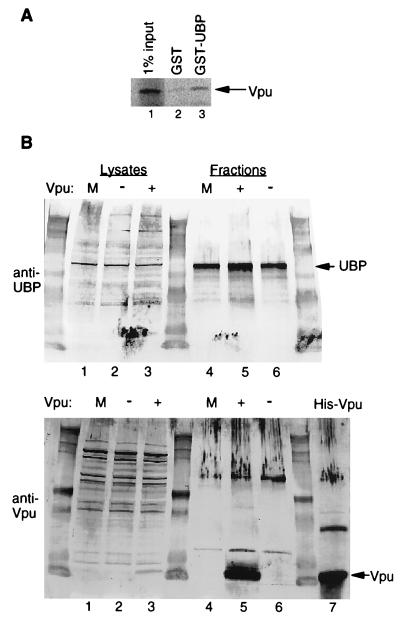

To verify the Vpu-UBP interaction demonstrated with the two-hybrid system, an in vitro binding assay was performed. UBP was expressed as a fusion protein with a portion of the enzyme GST. The GST-UBP fusion protein was then tested for its ability to bind to in vitro-translated 35S-labeled Vpu (Fig. 2A). At 75 mM NaCl, Vpu bound to GST-UBP (lane 3) at a level significantly over the background of GST alone (lane 2) as measured by phosphorimage analysis. The sensitivity of this Vpu-UBP interaction to salt concentration varied slightly from experiment to experiment, but the highest fold binding over background was always in the range of 50 to 100 mM NaCl (data not shown).

FIG. 2.

Interaction between Vpu and UBP in vitro and in vivo. (A) A GST-UBP fusion protein and GST alone were expressed and purified as described in Materials and Methods. Protein concentrations were measured using the Bradford assay (Bio-Rad). Equimolar amounts of GST-UBP (lane 3) or GST alone (lane 2) were incubated in solution with 35S-labeled in vitro-translated Vpu. GST or GST-UBP was recovered on glutathione-Sepharose beads, and Vpu was detected by SDS-PAGE and phosphorimage analysis. Lane 1 shows 1% of the input Vpu used in the binding reactions. (B) Lysates of mock-transfected (m) HeLa cells (lane 1) or cells transfected with either a vpu− (pBG135; lane 2) or a vpu+ (pGB108; lane 3) proviral DNA construct were subjected to anti-UBP immunoaffinity column chromatography analysis as described in Materials and Methods. Eluates from immunoaffinity columns are shown in lanes 4–6 (lane 4, mock; lane 5, pGB108; lane 6, pBG135). Cell lysates and column fractions were subjected to Western blot analysis with either anti-UBP (top) or anti-Vpu (bottom) antiserum. His-tagged E. coli-expressed Vpu is shown in lane 7.

The binding of Vpu and UBP was verified in vivo by using an immunoaffinity column constructed with the anti-UBP antibody. pGB108 (16) is an env− derivative of the HIV-1 infectious molecular clone NL4-3. pBG135 (19) is a vpu− derivative of GB108. HeLa cell lysates, representative of mock (lane 1), pBG135 (lane 2, Vpu−), or pGB108 (lane 3, Vpu+) transfectants, were placed on the column. Proteins eluted from the column are shown in lanes 4 to 6 in both panels. As expected, eluates from all three conditions showed an enrichment for UBP when analyzed by Western blotting (Fig. 2B, top, lanes 4 to 6). When the immunoaffinity column fractions were probed for Vpu, a distinct band appeared in only one lane corresponding to those cells transfected with pGB108 (Fig. 2B, bottom, lane 5). Neither UBP nor Vpu bound to an immunoaffinity column made with preimmune rabbit serum, showing that the purification of Vpu by the anti-UBP column was due to specific interaction with UBP (data not shown). These results indicate that UBP and Vpu stably interact in vivo.

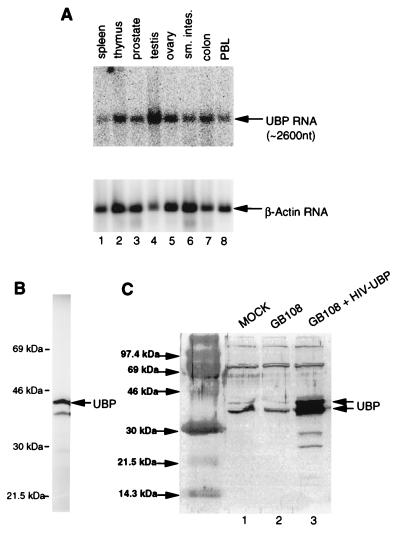

To identify human cell types that express ubp RNA, we performed Northern blot analysis of RNA from eight human tissues (spleen, thymus, prostate, testis, ovary, colon, small intestine, and peripheral blood leukocytes), using a ubp cDNA probe. The results of this experiment indicated that ubp RNA is expressed in each of these tissues (Fig. 3A). Moreover, the length of the detected RNA (2,600 nucleotides) was consistent with the length of the ubp cDNA (2,221 bp), taking into consideration the addition of an average-size poly(A) tail to the ubp mRNA.

FIG. 3.

(A) Northern blot analysis of ubp RNA from human cells. Top, mRNA from human spleen (lane 1), thymus (lane 2), prostate (lane 3), testis (lane 4), ovary (lane 5), small intestine (lane 6), colon (lane 7), and peripheral blood leukocytes (lane 8), probed with a ubp cDNA probe; bottom, the same blot when stripped and reprobed with a β-actin control probe. nt, nucleotides. (B) In vitro translation of UBP. The plasmid KT173 was used to express UBP in a coupled transcription-translation system (TnT; Promega) in the presence of [35S]methionine and [35S]cysteine, and protein was analyzed by SDS-PAGE and detected by phosphorimage analysis. (C) Endogenous expression and overexpression of UBP in HeLa cells. Because high level expression of UBP from pHIV-UBP is Tat dependent, plasmid pHIV-UBP was cotransfected with a plasmid that expresses HIV-1 Tat (pGB108 [16]). Lysates of mock-transfected HeLa cells (lane 1), HeLa cells transfected with pGB108 alone (lane 2), and HeLa cells transfected with pHIV-UBP and pGB108 (lane 3) were subjected to Western blot analysis using an IgG-purified rabbit polyclonal anti-UBP antibody.

To determine whether the ubp open reading frame could be translated to produce a protein of the expected size, we constructed pKT173, a plasmid which expresses the ubp coding region from a phage T7 promoter. pKT173 was used to program in vitro-coupled transcription-translation reactions. As shown in Fig. 3B, a protein of about 42 kDa was produced. To ensure that the ubp cDNA contained the entire coding region, we constructed pHIV-UBP, a plasmid that expresses the ubp cDNA from the HIV-1 LTR. This plasmid was used to overexpress UBP in HeLa cells. Cells were lysed at 48 h posttransfection, and the lysates were subjected to Western blot analysis with a rabbit polyclonal UBP antiserum. As shown in Fig. 3C, two UBP species of slightly different mobility on the gel were produced in cells transfected with pGB108 and pHIV-UBP (lane 3), and those two species comigrated with two endogenous UBP species in mock-transfected (lane 1) and GB108-transfected (lane 2) cells. Thus, the ubp cDNA appears to contain a full-length open reading frame. Western blot analysis on lysates from COS-1 and CEM (a CD4+ T-cell line) cells indicated that UBP was also expressed in both of these cell types (data not shown). The genesis of the two species of UBP in HeLa cells is not clear. The larger of the two species may be the result of posttranslational modification. Alternatively, the smaller of the two UBP species may be a stable degradation or proteolytically processed product of UBP. In addition, two minor bands of 25 to 28 kDa are detectable in lysates of HIV-UBP-transfected cells. While the origin of these species is not known, the bands most likely represent degradation products of UBP. They are more easily detected in HIV-UBP-transfected cells because of the high level of expression of UBP.

UBP is a novel member of the TPR family of proteins.

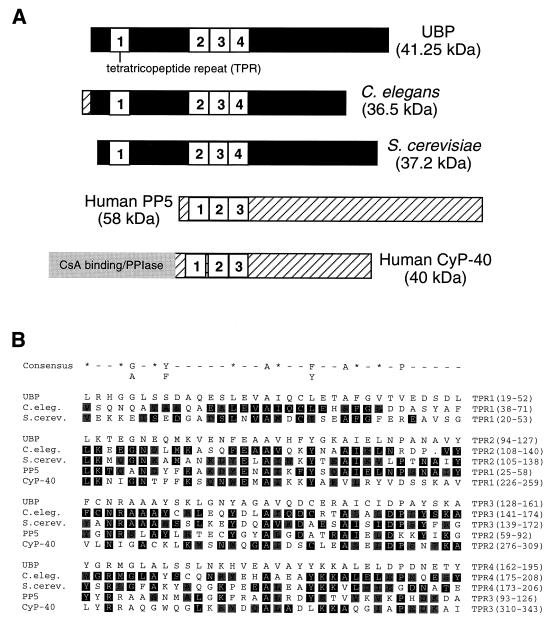

The deduced amino acid sequence of UBP was used to search sequence databases for polypeptides that are similar to UBP. The results of this search identified a group of very diverse proteins including a protein of unknown function from Caenorhabditis elegans, a protein of unknown function from S. cerevisiae, two immunophilins (CyP-40 [36] and FK506-binding protein 59 [FKBP59] [6]), two organelle-targeting proteins (Pxr1p [11] and MAS70 [25]), a nuclear serine/threonine phosphatase (PP5 [7]), and proteins involved in mitosis (nuc2+ [26] and CDC23 [42]). A comparison of UBP to four of these proteins is shown in Fig. 4A. Most of the proteins resulting from the search contain multiple copies of a 34-amino-acid long repeat motif, the TPR (26, 42). UBP contains four TPR motifs, three of them in tandem (Fig. 1 and 4A). Similarity between UBP and most of the proteins identified from the search is almost exclusively limited to the TPR motifs. However, the proteins of unknown function from C. elegans and S. cerevisiae contain extended regions of similarity to UBP including sequences outside the TPR motifs, indicating that these proteins are likely homologs of human UBP. The C. elegans protein is 45% identical and 63% similar to UBP with six gaps in the alignment. The S. cerevisiae protein is 37% identical and 56% similar to UBP with eight gaps in the alignment (data not shown). An alignment of the TPR motifs of UBP with the TPR motifs of other proteins and the TPR consensus sequence (26) is shown in Fig. 4B. The TPR motifs of UBP match the consensus sequence as well or better than the TPR motifs of previously published TPR proteins.

FIG. 4.

Comparison of UBP with other members of the TPR family. (A) UBP is shown aligned with four proteins resulting from the BLAST sequence similarity search (3). TPR motifs are shown as numbered white boxes. Regions outside the TPR motifs that show sequence similarity to UBP are shown in black. Regions that do not contain sequence similarity to UBP are cross-hatched or shaded. (B) Alignment of TPR motifs in UBP and related proteins. The amino acid sequences of the TPR motifs of UBP, C. elegans (C.eleg.) R05F9.10 (accession no. U41533), S. cerevisiae (S.cerev.) UNF346 (accession no. U43491), human PP5, and human CyP-40 are shown aligned with each other and with the TPR consensus sequence. In the consensus sequence, an asterisk indicates any large hydrophobic residue, and a dash indicates any residue. Sequence identity to UBP is indicated by black reverse print. Sequence similarity to UBP is indicated by gray shading. PPIase, peptidyl-proyl cis-trans isomerase.

The TPR family of proteins contains members with very diverse activities, and the motif has been well characterized physically. The TPR motif probably adopts a secondary structure consisting of a 25- to 30-amino acid amphipathic α-helix followed by a short proline-induced turn. Formation of this structure has been demonstrated by circular dichroism and limited proteolysis for the protein nuc2+ of Schizosaccharomyces pombe (26). These α-helices are believed to interact intra- or intermolecularly with each other through their hydrophobic faces. The TPRs are likely involved in mediating interactions between proteins. Indeed, the TPR motifs of the immunophilin FKBP59 (34), the peroxisome-targeting protein Pxr1p (11), and a mouse homolog of the nuclear phosphatase PP5 (9) have been shown to be involved in protein-protein interaction.

Interaction between UBP and HIV-1 Gag.

The HIV-1 Gag protein is the principal component of the virus particle. Since Gag expression is sufficient for particle formation and responsiveness to Vpu, Gag contains a direct or indirect target of the particle release enhancement activity of Vpu (30). We used multiple approaches to determine whether Vpu and Gag interact directly and have obtained no evidence for such an interaction (data not shown). However, an alternative possibility is that the ability of Vpu to enhance particle release is manifested through cellular protein intermediates such as UBP. To determine whether UBP interacts with Gag, we performed an in vitro binding assay using these two proteins. His-tagged HIV-1 Gag precursor, a GST-UBP fusion protein, and GST alone were expressed in parallel cultures of E. coli, and bacterial lysates were used for the in vitro binding assay. His-tagged Gag was tested for interaction with either GST-UBP or GST alone. As shown in Fig. 5A, HIV-1 Gag protein specifically bound to GST-UBP (lane 2) at a level significantly over the background of GST alone (lane 1) as measured by phosphorimage analysis. The association between Gag and UBP could be observed at salt concentrations ranging from 1 to 500 mM NaCl or KCl (data not shown). A concentration of 300 mM NaCl was found to be optimal for specific binding. In addition, preliminary results with anti-UBP immunoaffinity column chromatography indicate that UBP interacts with Gag in HeLa cells (data not shown).

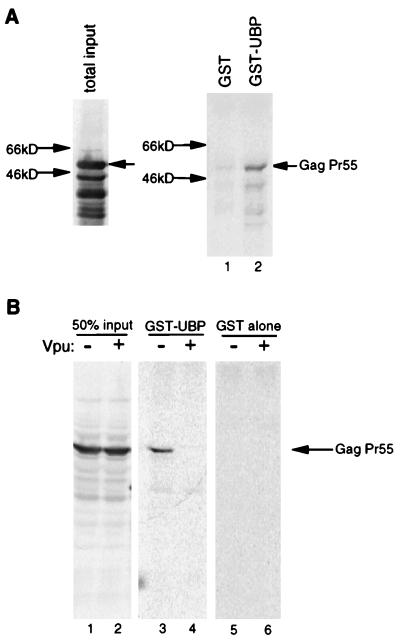

FIG. 5.

Interaction between GST-UBP and Gag expressed in bacteria and in HeLa cells. (A) Left, lysate of E. coli expressing His-Gag protein analyzed by Western blot using anti-Gag antiserum; right, result of an in vitro binding assay performed as described in Materials and Methods, using His-Gag (the total input is shown in the left-hand panel) and either GST-UBP (lane 2) or GST alone (lane 1). Gag protein from the binding assay was also detected by Western blot analysis with anti-Gag antiserum. Total protein concentrations of bacterial lysates used in the binding assay were measured by the Bradford assay. (B) Left, anti-Gag Western blot analysis of lysates of HeLa cells transfected with either a vpu− (lane 1) or a vpu+ (lane 2) HIV-1 proviral construct. These lysates were used for in vitro binding assays as described in Materials and Methods, and the results are shown in the middle panel (lane 3, vpu− construct; lane 4, vpu+ construct). Gag from HeLa cell lysates did not bind to GST alone (lanes 5 and 6). The presence or absence of Vpu expression in HeLa cells is indicated above the gels.

Gag protein expressed in transfected HeLa cells was also tested for its ability to interact with GST-UBP. HeLa cells were transfected with either pMS156, a vpu+ protease− HIV-1 proviral construct, or pHJ121, a vpu− protease− proviral construct (30). We examined the efficiency of particle release from cells transfected with these constructs and observed the expected effect: particle release was more efficient in the presence of Vpu (data not shown). Transfected cell lysates were then used as a source of Gag protein for the in vitro binding assay. When Gag was expressed in the absence of Vpu, Gag stably interacted with GST-UBP (Fig. 5B, lane 3). However, when Gag was expressed in the presence of Vpu, Gag was unable to interact with excess GST-UBP, indicating that the coexpression of Vpu abrogated stable UBP-Gag interaction (Fig. 5B, lane 4). To see whether Vpu from transfected cells was interacting with GST-UBP in vitro, thereby preventing interaction between Gag from transfected cells and GST-UBP, Gag and Vpu were expressed in separate cell cultures, and lysates were mixed and then added to GST-UBP. The result of this experiment was that Gag was able to bind to GST-UBP (data not shown). This result demonstrates that Vpu is not simply binding GST-UBP in vitro and competitively inhibiting interaction between GST-UBP and Gag. Therefore, the negative effect of Vpu on the ability of Gag to bind UBP occurs within HeLa cells. Taken together, these results indicate that Gag may be modified in some way in cells expressing Vpu and that this modification renders Gag unable to interact subsequently with UBP. It is also worth noting that preliminary results with anti-UBP immunoaffinity column chromatography indicate that UBP interacted with Gag in HeLa cells only in the absence of Vpu (data not shown).

Effect of UBP overexpression on HIV-1 particle release.

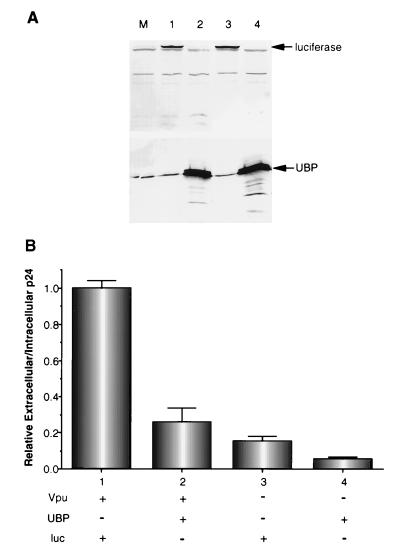

To determine whether UBP affects Vpu-mediated enhancement of virus release, UBP was overexpressed in virus-producing cells in the presence and absence of Vpu expression. As a control for nonspecific effects of protein overexpression on particle release, luciferase was expressed in cultures that were not overexpressing UBP. Overexpression of luciferase and UBP were confirmed by Western blot analysis using the appropriate antisera (Fig. 6A). As expected, the lack of wild-type Vpu expression resulted in a fivefold reduction in particle release (Fig. 6B; compare bars 1 and 3). In the presence of Vpu, UBP overexpression caused a fourfold decrease in virus release (Fig. 6B; compare bars 1 and 2). In the absence of Vpu, particle release was further reduced two- to threefold by UBP overexpression (Fig. 6B; compare bars 3 and 4). The intracellular p24 levels in cells overexpressing UBP were not lower than in cells expressing luciferase (data not shown), indicating that the inhibition of particle release by UBP overexpression was not due to a cytotoxic effect of high levels of UBP. These results demonstrate that overexpression of UBP in virus-producing cells has a negative effect on HIV-1 particle release.

FIG. 6.

Effect of UBP overexpression on HIV-1 particle release. HeLa cells were mock transfected (lane M) or transfected with either pGB108 (lanes 1 and 2, Vpu+) or pBG135 (lanes 3 and 4, Vpu−) and either pHIV-UBP (lanes 2 and 4, UBP+) or pTAR-luc (lanes 1 and 3, Luc+) (27). (A) Thirty-six hours posttransfection, Western blot analysis was performed on cell lysates with antigen affinity-purified antiluciferase (top) and antigen affinity-purified anti-UBP (bottom) antibodies. Lane numbers above blots correspond to numbers under the bar graph in panel B. (B) Particle release was assayed using a p24 antigen capture ELISA as described in Materials and Methods. The data are represented as the ratio of extracellular to intracellular p24 and are normalized to the GB108+TAR-luc cotransfection (bar 1). The data represent one of two independent experiments performed in triplicate. Similar results were obtained from both experiments.

DISCUSSION

The fact that high-level expression of UBP reduces the efficiency of particle release suggests a simple negative role for UBP. Moreover, the observation that Vpu forms stable complexes with UBP and abrogates stable UBP-Gag interaction is consistent with the idea that association of UBP with Gag is detrimental to virus release and that a role of Vpu is to dissociate UBP-Gag complexes. However, scrutiny of the data from Fig. 5 provides an intriguing alternative possibility. Stable association between Gag and UBP is detected only in the absence of Vpu; when Vpu is present, only stable Vpu-UBP complexes are observed. The fact that no detectable Gag is found associated with GST-UBP when Gag is expressed in the presence of Vpu suggests that the interaction between UBP and Gag, along with subsequent dissociation by Vpu, leads to an irreversible change in Gag, resulting in the inability of Gag to interact with UBP. In this scenario, UBP would be a factor required for correct particle formation and release. Overexpression of UBP would negatively affect particle release simply by competitively inhibiting Vpu: association between excess free UBP and Vpu would interfere with the ability of Vpu to dissociate UBP-Gag complexes.

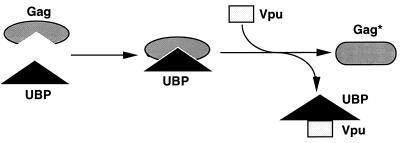

A possible model for Vpu-mediated enhancement of HIV-1 virion release is presented in Fig. 7. UBP interacts with Gag resulting in the transient formation of Gag-UBP complexes (in the absence of Vpu, these complexes are stable). Vpu then interacts with UBP, resulting in dissociation of Gag-UBP complexes. Since the resulting Gag is no longer competent for binding to GST-UBP, it appears that interaction of Gag with UBP and subsequent Vpu-mediated dissociation results in an irreversible modification of Gag (in the figure, this modification is indicated by Gag* for heuristic purposes). This uncharacterized modification of Gag may influence Vpu-mediated particle release in one of two ways. First, the conversion of Gag to Gag* may be directly responsible for enhancing particle release in that only particles composed of Gag* can be released efficiently. Alternatively, the modification of Gag may enhance virus release indirectly by rendering Gag* unable to bind to UBP, thereby preventing the formation of inhibitory Gag-UBP complexes.

FIG. 7.

Model of the roles of Vpu and UBP in particle release. UBP interacts with Gag forming a complex. In the absence of Vpu, this complex is stable and may be inhibitory to viral particle release. When Vpu is present, UBP is disassociated from Gag, allowing for modification(s) of Gag to form Gag*. This modification changes the protein in such a way that it can no longer interact with UBP. Either the inability of Gag* to interact with UBP or the modification of Gag itself results in enhancement of virus release.

Recent experiments indicate that the matrix domain of HIV-1 Gag is required for Vpu-mediated enhancement of particle release (30). Based on these results, we speculate that UBP interacts with the matrix domain of Gag. Preliminary experiments indicate that the interaction of UBP with Gag may be mediated by the matrix-capsid junction and the p6 domain of Gag (data not shown). The fact that the matrix-capsid junction may be involved in Gag-UBP interaction raises the possibility that the negative effect of UBP overexpression on particle release observed in our experiments was due to improper processing of Gag. However, this is unlikely because previous studies have shown that Gag processing does not affect virus release. Moreover, the effect of Vpu on virus particle release can occur in the absence of processing (21, 30). The roles of the matrix domain and UBP-Gag interaction in Vpu-mediated enhancement of virus release are under investigation.

UBP contains four TPR motifs. TPRs are known to form a secondary structure that has been proposed to mediate interaction between two TPRs (26). Therefore, the TPR motifs of UBP may mediate the interaction of UBP with Vpu or Gag. Vpu and Gag do not contain TPR motifs. However, the TPRs of FKBP59 (34), Pxr1p (11), and a mouse homolog of PP5 (9) are directly involved in interactions with proteins that do not contain TPRs. Alternatively, the TPR motifs of UBP could mediate interaction of UBP with other cellular proteins involved in the enhancement of virus release. We are currently conducting experiments to identify the domains of Vpu, Gag, and UBP that account for interactions between UBP and Vpu or Gag.

The HIV-1 Gag protein interacts with cyclophilins A, B, and C, and cyclophilin A is incorporated into virus particles (15, 31, 46). Cyclophilins and FKBPs comprise the immunophilin superfamily. Immunophilins are involved in protein folding, and some act as intracellular receptors for the immunosuppressive drugs CsA and FK506. UBP is probably not an immunophilin because it lacks an obvious binding site for CsA or FK506. Moreover, UBP is not detectably incorporated into virus particles (data not shown). However, one possible scenario for UBP function is that UBP modifies Gag by mediating the proper folding of the protein. The TPR proteins FKBP59 and CyP-40 are known to interact with heat shock protein 90, and these interactions are likely involved in the proper folding of steroid hormone receptors (34, 35).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Diccon Fiore for preparation of cells and Katherine Gerten and Joshua Fischer for plasmid DNA preparations.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adachi A, Gendelman H E, Koenig S, Folks T, Willey R, Rabson A, Martin M A. Production of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome-associated retrovirus in human and nonhuman cells transfected with an infectious molecular clone. J Virol. 1986;59:284–291. doi: 10.1128/jvi.59.2.284-291.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alkhatib G, Combadiere C, Broder C C, Feng Y, Kennedy P E, Murphy P M, Berger E A. CC CKR5: a RANTES, MIP-1alpha, MIP-1beta receptor as a fusion cofactor for macrophage-tropic HIV-1. Science. 1996;272:1955–1958. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5270.1955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Altschul S F, Gish W, Miller W, Myers E W, Lipman D J. Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol. 1990;215:403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bour S, Schubert U, Strebel K. The human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Vpu protein specifically binds to the cytoplasmic domain of CD4: implications for the mechanism of degradation. J Virol. 1995;69:1510–1520. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.3.1510-1520.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Braaten D, Franke E K, Luban J. Cyclophilin A is required for an early step in the life cycle of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 before the initiation of reverse transcription. J Virol. 1996;70:3551–3560. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.6.3551-3560.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Callebaut I, Renoir J M, Lebeau M C, Massol N, Burny A, Baulieu E E, Mornon J P. An immunophilin that binds Mr 90,000 heat shock protein: main structural features of a mammalian p59 protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:6270–6274. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.14.6270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen M X, McPartlin A E, Brown L, Chen Y H, Barker H M, Cohen P T. A novel human protein serine/threonine phosphatase, which possesses four tetratricopeptide repeat motifs and localizes to the nucleus. EMBO J. 1994;13:4278–4290. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06748.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen M Y, Maldarelli F, Karczewski M K, Willey R L, Strebel K. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Vpu protein induces degradation of CD4 in vitro: the cytoplasmic domain of CD4 contributes to Vpu sensitivity. J Virol. 1993;67:3877–3884. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.7.3877-3884.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chinkers M. Targeting of a distinctive protein-serine phosphatase to the protein kinase-like domain of the atrial natriuretic peptide receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:11075–11079. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.23.11075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dalgleish A G, Beverley P C, Clapham P R, Crawford D H, Greaves M F, Weiss R A. The CD4 (T4) antigen is an essential component of the receptor for the AIDS retrovirus. Nature. 1984;312:763–767. doi: 10.1038/312763a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dodt G, Braverman N, Wong C, Moser A, Moser H W, Watkins P, Valle D, Gould S J. Mutations in the PTS1 receptor gene, PXR1, define complementation group 2 of the peroxisome biogenesis disorders. Nat Genet. 1995;9:115–125. doi: 10.1038/ng0295-115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Durfee T, Becherer K, Chen P-L, Yeh S-H, Yang Y, Kilburn A E, Lee W-H, Elledge S J. The retinoblastoma protein associates with the protein phosphatase type 1 catalytic subunit. Genes Dev. 1993;7:555–569. doi: 10.1101/gad.7.4.555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Feng Y, Broder C, Kennedy P E, Berger E A. HIV-1 entry cofactor: functional cDNA cloning of a seven-transmembrane, G protein-coupled receptor. Science. 1996;272:872–877. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5263.872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fields S. The two-hybrid system to detect protein-protein interactions. Methods Companion Methods Enzymol. 1993;5:116–124. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Franke E K, Yuan H E-H, Luban J. Specific incorporation of cyclophilin A into HIV-1 virions. Nature. 1994;372:359–362. doi: 10.1038/372359a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Freed E O, Delwart E L, Buchschacher G L, Jr, Panganiban A T. A mutation in the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 transmembrane glycoprotein gp41 dominantly interferes with fusion and infectivity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:70–74. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.1.70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Friborg J, Ladha A, Gottlinger H, Garzon S, Haseltine W A, Cohen E A. Functional analysis of the phosphorylation sites on the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Vpu protein. J Acquired Immune Defic Syndr. 1995;8:10–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Galat A. Peptidylproline cis-trans-isomerases: immunophilins. Eur J Biochem. 1993;216:689–707. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1993.tb18189.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Geraghty R J, Panganiban A T. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Vpu has a CD4- and an envelope glycoprotein-independent function. J Virol. 1993;67:4190–4194. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.7.4190-4194.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Geraghty R J, Talbot K J, Callahan M, Harper W, Panganiban A T. Cell type-dependence for Vpu function. J Med Primatol. 1994;23:146–150. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0684.1994.tb00115.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gottlinger H G, Dorfman T, Cohen E A, Haseltine W A. Vpu protein of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 enhances the release of capsids produced by gag gene constructs of widely divergent retroviruses. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:7381–7385. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.15.7381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hallenberger S, Bosch V, Angliker H, Shaw E, Klenk H D, Garten W. Inhibition of furin-mediated cleavage activation of HIV-1 glycoprotein gp160. Nature. 1992;360:358–361. doi: 10.1038/360358a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Handley, M. A. Unpublished data.

- 24.Handley M A, Steigbigel R T, Morrison S A. A role for urokinase-type plasminogen activator in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection of macrophages. J Virol. 1996;70:4451–4456. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.7.4451-4456.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hase T, Riezman H, Suda K, Schatz G. Import of proteins into mitochondria: nucleotide sequence of the gene for a 70-kd protein of the yeast mitochondrial outer membrane. EMBO J. 1983;2:2169–2172. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1983.tb01718.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hirano T, Kinoshita N, Morikawa K, Yanagida M. Snap helix with knob and hole: essential repeats in S. pombe nuclear protein nuc2+ Cell. 1990;60:319–328. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90746-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kim Y-S, Panganiban A T. The full-length Tat protein is required for TAR-independent, post-transcriptional trans activation of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 env gene expression. J Virol. 1993;67:3739–3747. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.7.3739-3747.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kimura T, Nishikawa M, Ohyama A. Intracellular membrane traffic of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 envelope glycoproteins: vpu liberates Golgi-targeted gp160 from CD4-dependent retention in the endoplasmic reticulum. J Biochem. 1994;115:1010–1020. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a124414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Klimkait T, Strebel K, Hoggan M D, Martin M A, Orenstein J M. The human immunodeficiency virus type 1-specific protein vpu is required for efficient virus maturation and release. J Virol. 1990;64:621–629. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.2.621-629.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee Y-H, Schwartz M D, Panganiban A T. The HIV-1 matrix domain of Gag is required for Vpu responsiveness during particle release. Virology. 1997;237:46–55. doi: 10.1006/viro.1997.8711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Luban J, Bossolt K L, Franke E K, Kalpana G V, Goff S P. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Gag protein binds to cyclophilins A and B. Cell. 1993;73:1067–1078. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90637-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Maldarelli F, Chen M Y, Willey R L, Strebel K. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Vpu protein is an oligomeric type I integral membrane protein. J Virol. 1993;67:5056–5061. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.8.5056-5061.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McBride M S, Panganiban A T. The human immunodeficiency virus type 1 encapsidation site is a multipartite element composed of functional hairpin structures. J Virol. 1996;70:2963–2973. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.5.2963-2973.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Radanyi C, Chambraud B, Baulieu E E. The ability of the immunophilin FKBP59-HBI to interact with the 90-kDa heat shock protein is encoded by its tetratricopeptide repeat domain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:11197–11201. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.23.11197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ratajczak T, Carrello A. Cyclophilin 40 (CyP-40), mapping of its hsp90 binding domain and evidence that FKBP52 competes with CyP-40 for hsp90 binding. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:2961–2965. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.6.2961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ratajczak T, Carrello A, Mark P J, Warner B J, Simpson R J, Moritz R L, House A K. The cyclophilin component of the unactivated estrogen receptor contains a tetratricopeptide repeat domain and shares identity with p59 (FKBP59) J Biol Chem. 1993;268:13187–13192. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rose M D, Winston F, Hieter P. Methods in yeast genetics. A laboratory course manual. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schiestl R H, Gietz R D. High efficiency transformation of intact yeast cells using single stranded nucleic acids as carrier. Curr Genet. 1989;16:339–346. doi: 10.1007/BF00340712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schubert U, Bour S, Ferrer-Montiel A V, Montal M, Maldarelli F, Strebel K. The two biological activities of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Vpu protein involve two separable structural domains. J Virol. 1996;70:809–819. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.2.809-819.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schubert U, Strebel K. Differential activities of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1-encoded Vpu protein are regulated by phosphorylation and occur in different cellular compartments. J Virol. 1994;68:2260–2271. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.4.2260-2271.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sikorski R S, Boguski M S, Goebl M, Hieter P. A repeating amino acid motif in CDC23 defines a family of proteins and a new relationship among genes required for mitosis and RNA synthesis. Cell. 1990;60:307–317. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90745-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Strebel K, Klimkait T, Maldarelli F, Martin M A. Molecular and biochemical analyses of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Vpu protein. J Virol. 1989;63:3784–3791. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.9.3784-3791.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Strebel K, Klimkait T, Martin M A. A novel gene of HIV-1, vpu, and its 16-kilodalton product. Science. 1988;241:1221–1223. doi: 10.1126/science.3261888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Terwilliger E F, Cohen E A, Lu Y C, Sodroski J G, Haseltine W A. Functional role of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 vpu. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:5163–5167. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.13.5163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Thali M, Bukovsky A, Kondo E, Rosenwirth B, Walsh C T, Sodroski J, Gottlinger H G. Functional association of cyclophilin A with HIV-1 virions. Nature. 1994;372:363–365. doi: 10.1038/372363a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Willey R L, Maldarelli F, Martin M A, Strebel K. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Vpu protein induces rapid degradation of CD4. J Virol. 1992;66:7193–7200. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.12.7193-7200.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yao X J, Gottlinger H, Haseltine W A, Cohen E A. Envelope glycoprotein and CD4 independence of Vpu-facilitated human immunodeficiency virus type 1 capsid export. J Virol. 1992;66:5119–5126. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.8.5119-5126.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]