Abstract

State Perinatal Quality Collaboratives (PQCs) are networks of multidisciplinary teams working to improve maternal and infant health outcomes. To address the shared needs across state PQCs and enable collaboration, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), in partnership with March of Dimes and perinatal quality improvement experts from across the country, supported the development and launch of the National Network of Perinatal Quality Collaboratives (NNPQC). This process included assessing the status of PQCs in this country and identifying the needs and resources that would be most useful to support PQC development. National representatives from 48 states gathered for the first meeting of the NNPQC to share best practices for making measurable improvements in maternal and infant health. The number of state PQCs has grown considerably over the past decade, with an active PQC or a PQC in development in almost every state. However, PQCs have some common challenges that need to be addressed. After its successful launch, the NNPQC is positioned to ensure that every state PQC has access to key tools and resources that build capacity to actively improve maternal and infant health outcomes and healthcare quality.

Keywords: Perinatal Quality Collaboratives, quality improvement, obstetrics

Introduction

Perinatal Quality Collaboratives (PQCs) are state or multistate networks of multidisciplinary teams, working to improve measurable outcomes for maternal and infant health by advancing evidence-informed clinical practices and processes using quality improvement (QI) principles. PQCs address gaps by working with clinical teams, experts, and stakeholders (including patients and families) to disseminate best practices, reduce variation in practice and outcomes, and to optimize resources to improve perinatal care. They include key leaders in private, public, and academic healthcare settings and public health professionals with expertise in evidence-based obstetric and neonatal care and QI science.1,2 Strategies include provision of QI science support and assistance to clinical teams, use of the collaborative learning model, and rapid feedback of data to member facilities to improve care.3 The ultimate goal of PQCs is to achieve improvements in population-level outcomes in maternal and infant health throughout the state. A growing body of evidence demonstrates that PQCs have contributed to improvements in healthcare delivery and perinatal outcomes. Examples include reductions in elective deliveries without a medical indication before 39 weeks gestation,4,5 reductions in healthcare-associated bloodstream infections in newborns,6 reductions in severe maternal morbidity,7 increases in appropriate use and documentation of use of antenatal corticosteroids to improve fetal lung maturity,8-10 and improvements in use of progestogen therapy for prevention of preterm births.11 In addition to improving clinical processes and outcomes, PQCs have also been successful at improving the accuracy and timeliness of administrative data for providing feedback to participating facilities.12,13

In 2011, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) Division of Reproductive Health entered into a cooperative agreement with three established PQCs (California, New York, and Ohio) to improve perinatal care through this QI model.1 This collaboration had three objectives: to increase capacity within these supported states by improving statewide representation, to expand the range of neonatal and maternal health issues addressed by these PQCs, and to then share experiences and knowledge gained from the work of these more established PQCs to help advance PQCs in other states. In 2014, CDC support for PQCs expanded to include three additional PQCs in Illinois, Massachusetts, and North Carolina, to further support shared learning and collaboration among states. An important result of this collaboration has been strengthened partnerships between PQCs and their state health departments, leading to the recognition and institutionalizing of the important role they play in the core functions of public health.

Recognizing the value of PQCs, CDC also worked with PQC experts to develop a comprehensive guide, Developing and Sustaining Perinatal Quality Collaboratives: A Resource Guide for States,11 to help advance the work of state PQCs in various stages of development. Examples of topics covered in this resource guide include starting a statewide collaborative, launching initiatives, data and measurement, and sustainability. This guide is an online document that includes links to other valuable resources for perinatal QI work. Other resources made available to PQCs include a map of state PQC contacts and webinars addressing topics central to PQC development and key QI initiatives (www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/maternalinfanthealth/pqc.htm).

One of the hallmarks of this work is collaboration, and the value of formal and informal sharing within and between state PQCs has contributed to the growth and success of this work. Providing a way for PQCs to communicate with each other and share practices and experiences is central to CDC support. Many states currently have active collaboratives in varying stages of development12; however, although PQCs in some states have experienced considerable success in achieving statewide improvements, others would benefit from additional support and resources to reach that goal. There is a need to expand the successes achieved in improving perinatal outcomes to more states by building PQC capacity and fostering information sharing among PQCs. As of September 2017, CDC now provides support to 13 state (Colorado, Delaware, Florida, Georgia, Illinois, Louisiana, Massachusetts, Minnesota, Mississippi, New Jersey, New York, Oregon, and Wisconsin) PQCs that are in earlier stages of development. Also, in collaboration with March of Dimes, CDC has supported the development of the National Network of Perinatal Quality Collaboratives (NNPQC) to be a consultative and mentoring resource for PQCs.

Developing the NNPQC

The NNPQC was developed to build a national platform for state PQCs through collective leadership and support of evidence-based clinical practices and processes to improve pregnancy outcomes for women and newborns. First, an executive committee was established to conceptualize a framework, vision, mission, and membership plan for the NNPQC. Members of the executive committee are key leaders in perinatal QI work and include individuals associated with established and newly developing PQCs. Care was taken to ensure representation by both maternal and infant care providers, various disciplines (physicians, nurses, and public health), geographic regions (West, Midwest, Northeast, and South), patient and family partners, and representatives from other key maternal and neonatal quality organizations and initiatives, including the Alliance for Innovation on Maternal Health, the National Institute for Children’s Health Quality (NICHQ), and the Vermont Oxford Network’s (VON) STATES TOGETHER project (Table 1). Two nationally recognized perinatal QI leaders, an obstetrician and a neonatologist, were selected to lead this committee. Additional work of the committee included developing an online platform for information sharing and collaboration, planning the official launch meeting of the NNPQC, and developing and administering a needs assessment to PQCs across the country.

Table 1.

Composition of the National Network of Perinatal Quality Collaboratives Executive Committee

| Professional representation | No. of members |

|---|---|

| Obstetrics | 7 |

| Pediatrics | 7 |

| Family medicine | 1 |

| Nursing | 2 |

| Public health | 4 |

| Patient/family | 4 |

| Geographic representation | |

| West | 3 |

| Midwest | 4 |

| Northeast | 6 |

| South | 12 |

The mission of the NNPQC, as identified by the executive committee, is to support the development and enhance the ability of PQCs to make measurable improvements in state-wide maternal and infant healthcare and health outcomes. The goals of the NNPQC are to strengthen existing PQC leadership, identify and disseminate best practices for establishing and sustaining PQCs, and identify and develop tools, training, and other resources necessary to foster the sharing of best practices to support a sustainable PQC infrastructure. The mission and goals guided the planning for the launch of the NNPQC, held on November 29–30, 2016. The November 2016 meeting launching the NNPQC provided an important opportunity to bring together representatives from across the United States to share their experiences and lessons learned in developing their respective PQCs and to create a valuable national QI network to support individual state collaboratives going forward.

Needs Assessment

For purposes of planning the initial NNPQC meeting and subsequent activities, the executive committee wished to better understand the structure, goals, and specific challenges of existing state-based PQCs. In addition, they wanted to identify which tools, training, and resources would be most useful to aid and support the development of sustainable PQCs. The needs assessment focused on identifying where PQCs exist, the organizational structure of PQCs (e.g., location, staffing, and funding), what QI projects PQCs were undertaking, what challenges they faced, and how the NNPQC could best support further growth and expansion of PQCs.

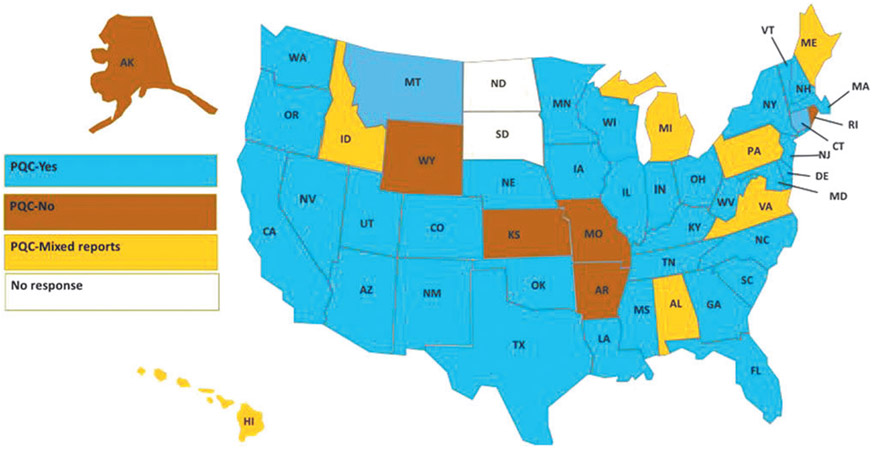

A comprehensive list of national PQC representatives was developed, including PQC directors and staff, patient and family partners, and state maternal and child health directors. A total of 173 individuals from all 50 states were contacted by e-mail and invited to complete a 10- to 15-minute online needs assessment. Responses were received (N = 119) from various PQC leaders and state agency representatives (Table 2) from 48 states. Respondents from 35 states reported having an active PQC, whereas respondents from 6 states reported not having a PQC. There were also seven states that had mixed reports of whether there was an active PQC in the state (Fig. 1). Although respondents from 35 states reported that there was a state PQC, we only received information for the other items from 32 PQCs. Of the 32 PQCs for which information was available, 27 PQCs were established within the past 10 years (Table 3). PQCs had a variety of organizational structures and homes; some functioned independently and others were located within various organizations, such as health departments or academic medical institutions. Although most PQCs represented one state, there was one regional PQC identified, representing several states. Twenty-nine PQCs indicated that they focused on both neonatal and maternal issues, whereas two reported focusing on maternal-only issues, and one on neonatal-only issues. Twenty-two reported having active QI projects that involve ongoing collection and feedback of data to their member facilities (Table 3).

Table 2.

Perinatal Quality Collaborative Role of Needs Assessment Respondents

| Designation | N = 119, n (%) |

|---|---|

| Project Director/Lead | 36 (30.8) |

| Clinical Lead | 13 (11.1) |

| Administrative Lead | 8 (6.8) |

| Hospital/Hospital System | 5 (4.3) |

| State Health Department | 4 (3.4) |

| Title V Director | 3 (2.6) |

| Content Lead | 3 (2.6) |

| Data Lead | 2 (1.7) |

| Other | 26 (21.8) |

| Role not specified | 19 (16.2) |

FIG. 1.

States reported to have a PQC on needs assessment, 2016. PQC, Perinatal Quality Collaborative.

Table 3.

State Perinatal Quality Collaborative Characteristics from Needs Assessment, 2016

| n (%) | |

|---|---|

| No. of years established | |

| ≤2 | 6 (18.8) |

| 3–6 | 10 (31.2) |

| 7–10 | 11 (34.4) |

| 11–20 | 3 (9.4) |

| >20 | 2 (6.2) |

| Where PQC is housed | |

| Academic institution | 9 (28.1) |

| State health department | 6 (18.8) |

| Independent (PQC stands alone) | 6 (18.8) |

| State hospital association | 2 (6.2) |

| Hospital/hospital system | 2 (6.2) |

| Nonprofit organization | 4 (12.5) |

| Otherb | 3 (9.4) |

| Focus of PQC | |

| Maternal only | 2 (6.2) |

| Neonatal only | 1 (3.1) |

| Maternal and neonatal | 29 (90.6) |

| PQCs with active projects (including ongoing data collection and feedback to member facilities | 22 (68.8) |

Includes 32 PQCs for which information was available.

Includes a PQC housed with the state Medicaid agency and two PQCs housed concurrently with two different entities.

PQC, Perinatal Quality Collaborative.

PQCs face a wide array of challenges. The most commonly reported challenge was the need for funding. About two-thirds (67%) of states had respondents who reported that funding was a top challenge for their state PQC. Other challenges included lack of time or competing priorities for the time of staff, difficulty engaging physician providers, data systems and/or data collection, personnel and staffing, and collaboration of stakeholders and partners. Most respondents (>70%) reported that the following resources would be helpful or very helpful to support their PQC: a knowledge bank with contact information of PQC experts (82%), 1:1 consultation (78%), national calls where states share projects (75%), and annual meetings (73%). The findings of this needs assessment guided the executive committee in planning for the national launch of the NNPQC.

Launch of the NNPQC

National experts and representatives from 48 states (including Alaska and Hawaii) and >20 private and federal partner organizations gathered in Fort Worth, Texas, on November 29–30, 2016, for the first meeting of the NNPQC. The goal was to create a “collaborative of collaboratives,” in which leaders of state-wide PQCs could share best practices with other states who could learn from their accomplishments as well as their challenges. More than 175 participants networked and shared best practices for making measurable improvements in maternal and infant health in their states. Participants included representatives of PQCs in 40 states, 8 additional states aspiring to develop a PQC, and multiple federal, state, and local public health, and clinical and private partners. The meeting was designed to maximize group interactions and allow members of PQCs that were in early stages of development and representatives from states that had not yet formed a PQC to gather information and ideas to further develop their perinatal QI work. The intent was to promote sharing of ideas and practices among attendees. Leaders from well-established PQCs were available to share their experiences, lessons learned, and encouragement. Attendees and speakers engaged and shared experiences in numerous ways, including formal general presentations, panel discussions, topic-specific break-out sessions, and two poster presentation receptions. Liberal use of question and answer opportunities generated very active discussion and audience participation.

The two interactive poster sessions were a highlight of the meeting, generating significant positive feedback. Each state was invited to submit a poster that included information about the state PQC structure, focus, current projects, and key successes and challenges. Forty-seven posters were presented representing 41 states and 6 partner organizations. Many of the posters presented work on multiple topics, addressing both maternal and neonatal care issues (Table 4), and also detailed many of the same challenges identified during the needs assessment.

Table 4.

Projects Presented During the National Network of Perinatal Quality Collaboratives Poster Sessions

| Initiative | No. of states reporting current or completed projects |

|---|---|

| Early elective delivery | 23 |

| Breastfeeding/human milk | 18 |

| Neonatal abstinence syndrome/maternal substance abuse | 16 |

| Obstetric hemorrhage | 10 |

| Support for vaginal birth/reduce unnecessary cesarean sections | 8 |

| Neonatal nosocomial infection | 8 |

| Safe sleep | 7 |

| Progesterone for preterm birth prevention | 7 |

| Antenatal steroids | 7 |

| Hypertension in pregnancy | 6 |

| Antibiotic stewardship | 5 |

| IM CoIIN | 5 |

| Severe maternal morbidity | 4 |

| Maternal mortality review | 4 |

| Long-acting reversible contraceptives | 4 |

| CCHD screening/registry | 4 |

| Birth certificate accuracy and improvement | 4 |

| Golden hour | 3 |

| Perinatal regionalization | 2 |

| Preterm birth education | 2 |

| Preeclampsia | 2 |

| Unexpected newborn complications | 2 |

| Discharge checklist/NICU graduates | 2 |

| Patient and family engagement | 2 |

| Centering pregnancy | 2 |

CCHD, critical congenital heart defect; IM CoIIN, Infant Mortality Collaborative Improvement & Innovation Network.

In the spirit of a “collaborative of collaboratives,” the meeting was designed to mirror a typical state collaborative conference, including active participation of patient and family representatives and other supporting organizations. The meeting included a powerful presentation from a patient family partner from one of the existing PQCs, a mother who had given birth to premature triplets, who was also a preeclampsia and obstetric hemorrhage survivor. She shared her perspective of the care experience and discussed ways she has contributed to quality and safety initiatives as a partner on hospital and statewide improvement teams. Participants were reminded of the value of the patient and family perspective and why patient and family partnership is an essential aspect of developing, implementing, and evaluating their QI work. Patients and their families are at the center of this work and beneficial to include as partners in PQC development and QI initiatives. Specific examples of patient family partnerships, resources, and guidance were provided.

Future Directions

The number of state-based PQCs has grown considerably over the past decade, with an active PQC or a PQC in development in almost every state now. However, PQCs have some common challenges that need to be addressed. Most of these challenges are related to the need for resources such as funding, personnel, staff time, and support for data systems and collection. Better understanding these needs presents an opportunity for the NNPQC to provide targeted information and support to PQCs across the country. CDC’s support for this work will continue through further development of a coordinating center for the NNPQC, which will be led by the NICHQ as of September 2017. The coordinating center will be responsible for working with the NNPQC to increase capacity in states by continuing to foster information sharing, assist in state-level PQC leadership development through an active mentoring program, and facilitating communication and relationship building between key stakeholders and partners, including patients and families.

Next steps in growing the NNPQC and increasing its national utility will include having the coordinating center develop and support a consultants’ bureau that can provide technical assistance to requesting PQCs and assisting in the development of suggested core sets of standardized metrics for different QI projects based on the shared experiences of participating PQCs. In addition, the online platform will be enhanced to more consistently reflect information that can be accessed and used by PQCs. This would include information about PQCs’ past and current QI projects as well as contacts for further information that would provide a readily available resource and mechanism for PQCs to benefit from the experience of others and improve efficiency.

Partnerships, collaboration, and sharing are what make the PQC model so successful, and the NNPQC provides practical and structured opportunities to share successful practices and avoid duplication of efforts. PQCs that have the necessary support and resources are able to address the perinatal QI needs within the state, resulting in measurable improved maternal and infant outcomes. In addition, PQCs are well positioned to facilitate the critical communication between clinicians of various disciplines and public health professionals necessary to fully achieve these improvements. This expanding national network provides a forum wherein successful strategies, tools, and metrics can easily be shared, collaboration across states becomes the norm, and significant improvements in population-level outcomes and health can be realized. The NNPQC’s role is to ensure that every state PQC has the tools to be successful. In creating a network that accelerates the spread of best practices among states, we are building QI capacity that has and will continue to dramatically improve the quality of care in the United States.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by the U.S. Federal CDC. We thank the leadership of the NNPQC executive committee for their input and lessons learned during the planning and launch of this network, and for this article. Committee members include Scott Berns, MD, MPH, FAAP; Peter Bernstein, MD; Ann E.B. Borders, MD, MPH, MSc; Tara Bristol Rouse, MA; William Callaghan, MD, MPH; Charlene Collier, MD, MPH, MHS; Evelyn Delgado; Ed Donovan, MD; Kelly Ernst, MPH; Marybeth Fry, MEd; Jeffrey B. Gould, MD, MPH; Munish Gupta, MD, MMSc; Zsakeba Henderson, MD; Paul Jarris, MD, MBA; Marilyn Kacica, MD, MPH; Carole Lannon, MD, MPH; Karyn Lee; Elliott Main, MD; Martin McCaffrey, MD, CAPT USN (Ret); Barbara Murphy, RN, MSN; Christine Olson, MD, MPH, CAPT USPHS; Kathleen Rice Simpson, PhD, RNC, FAAN; LaToshia Rouse; Danielle Suchdev, MPH; William Sappenfield, MD; and Lelis Vernon.

Footnotes

Author Disclosure Statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report. The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the CDC.

References

- 1.Henderson ZT, Suchdev DB, Abe K, Johnston EO, Callaghan WM. Perinatal Quality Collaboratives: Improving care for mothers and infants. J Womens Health 2014;23:368–372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gupta M, Donovan EF, Henderson Z. State-based Perinatal Quality Collaboratives: Pursuing improvements in perinatal health outcomes for all mothers and newborns. Semin Perinatol 2017;41:195–203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Institute for Healthcare Improvement. The break-through series: IHI’s collaborative model for achieving break-through improvement. IHI Innovation Series white paper. 2003; Available at: www.ihi.org/knowledge/Pages/IHIWhitePapers/TheBreakthroughSeriesIHIsCollaborativeModelforAchievingBreakthroughImprovement.aspx Accessed September 29, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Donovan EF, Lannon C, Bailit J, et al. A statewide initiative to reduce inappropriate scheduled births at 36(0/7)-38(6/7) weeks’ gestation. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2010;202: 243.e1–243.e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kacica MA, Glantz JC, Xiong K, Shields EP, Cherouny PH. A statewide quality improvement initiative to reduce non-medically indicated scheduled deliveries. Matern Child Health J 2017;21:932–941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fisher D, Cochran KM, Provost LP, et al. Reducing central line-associated bloodstream infections in North Carolina NICUs. Pediatrics 2013;132:e1664–e1671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Main EK, Cape V, Abreo A, et al. Reduction of severe maternal morbidity from hemorrhage using a state Perinatal Quality Collaborative. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2017;216:298.e1–298.e11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee HC, Lyndon A, Blumenfeld YJ, Dudley RA, Gould JB. Antenatal steroid administration for premature neonates in California. Obstet Gynecol 2011;117:603–609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wirtschafter DD, Danielsen BH, Main EK, et al. Promoting antenatal steroid use for fetal maturation: Results from the California Perinatal Quality Care Collaborative. J Pediatr 2006;148:606–612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kaplan HC, Sherman SN, Cleveland C, Goldenhar LM, Lannon CM, Bailit JL. Reliable implementation of evidence: A qualitative study of antenatal corticosteroid administration in Ohio hospitals. BMJ Qual Saf 2016;25:173–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Iams JD, Applegate MS, Marcotte MP, et al. A statewide progestogen promotion program in Ohio. Obstet Gynecol 2017;129:337–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lannon C, Kaplan HC, Friar K, et al. Using a state birth registry as a quality improvement tool. Am J Perinatol 2017;34:958–965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Perinatal Quality Collaborative Success Story. Illinois Perinatal Quality Collaborative improves the accuracy of birth certificate data. Available at: www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/maternalinfanthealth/pdf/Illinois-success-story_508tagged.pdf Accessed October 4, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Developing and Sustaining Perinatal Quality Collaboratives. A resource guide for states. CDC Perinatal Quality Collaborative Guide Working Group. Available at: www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/maternalinfanthealth/pdf/Best-Practices-for-Developing-and-Sustaining-Perinatal-Quality-Collaboratives_tagged508.pdf Accessed October 4, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 15.State Perinatal Quality Collaboratives. Available at: www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/maternalinfanthealth/pqc-states.html Accessed October 4, 2017.