Abstract

SIVsmmPBj14 is a highly pathogenic lentivirus which causes acute diarrhea, rash, massive lymphocyte proliferation predominantly in the gastrointestinal tract, and death within 7 to 14 days. In cell culture, the virus has mitogenic effects on resting macaque T lymphocytes. In contrast, SIVmac239 causes AIDS in rhesus macaques, generally within 2 years after inoculation. In a previous study, replacement of amino acid residues 17 and 18 of the Nef protein of SIVmac239 with the corresponding amino acid residues of the Nef protein of SIVsmmPBj14 yielded a PBj-like virus that caused extensive activation of resting T lymphocytes in cultures and acute PBj-like disease when inoculated into pig-tailed macaques. This study suggested that nef played a major role in both processes. In this study, we replaced the nef/long terminal repeat (LTR) region of a nonpathogenic simian-human immunodeficiency virus (SHIV), SHIVPPc, with the corresponding region from SIVsmmPBj14 and examined the biological properties of the resultant virus. Like SIVsmmPBj14, SHIVPPcPBjnef caused massive stimulation of resting peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC), which then produced virus in the absence of extraneous interleukin 2. However, when inoculated into macaques, the virus failed to replicate productively or cause disease. Thus, while these results confirmed that the nef/LTR region of SIVsmmPBj14 played a major role in the activation of resting PBMC, duplication of the cellular activation process in macaques may require a further interaction between nef and the envelope glycoprotein of simian immunodeficiency virus because SHIV, containing the envelope of human immunodeficiency virus type 1, failed to cause activation in vivo.

The ability of the primate lentiviruses simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV), simian-human immunodeficiency virus (SHIV), and human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) to cause AIDS is contingent on the ability of the viruses to cause a productive infection in CD4+ T cells that eventually leads to their elimination and a resultant loss of immunological competence of the host (1, 13, 23). Infection by each virus is initiated by binding of the viral glycoprotein to specific receptors on target cells; this is followed by internalization of the virus, reverse transcription of the viral genome, and integration of viral DNA into the host cell DNA (18). However, the productive phase of replication is dependent on the ability of the virus or other immunological factors to cause activation of the latently infected cell. The mechanisms of the activation process are not known. In macaques inoculated with SIVmac239 or SHIVKU-1, activation of infected cells develops predictably within 1 week and is reflected by the onset of viremia, extravasation of infected cells from the blood to other tissues such as the brain, and the ability of cultured peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) to produce virus without treatment of the cells with a mitogen (11, 13, 25). In contrast, inoculation of HIV-1 or SIVmac239 into cultured resting PBMC results in infection but not in activation of the cells or virus production (4, 5, 29). Therefore, the mechanisms causing activation of the cells in vivo and in cell cultures seem distinct.

SIVsmmPBj14 and its acutely pathogenic molecular clone, SIVsmmPBj14-mcl-1.9, differ from the other primate lentiviruses in that they cause infection and activation of resting mononuclear cells both in vitro and in vivo (2, 8–10). Under culture conditions, this virus has a mitogenic effect as indicated by incorporation of [3H]thymidine, proliferation of the cells, and production of virus. In the animal, the virus causes massive activation of the infected CD4+ T-cell population; lymphoproliferation results, predominantly in the gastrointestinal tract. Protracted diarrhea develops, and this results in the death of the animals within 2 weeks (7–9).

Studies of the mechanisms of activation of inoculated resting PBMC with SIVsmmPBj14 showed that the nef gene was directly responsible for the process (4). Site-directed mutagenesis of SIVmac239 nef endowed this virus with the novel ability to cause activation of the cells in vitro and also the hyperacute PBj-like disease in the animals (3). In the studies reported in this article, we asked whether the insertion of the PBj nef/long terminal repeat (LTR) region into the genome of an SHIV, a chimeric virus containing the gag, pol, vif, vpr, vpx, and nef genes of SIVmac and the tat, rev, vpu, and env genes of HIV-1 HXB2 (17), would create a mitogenic and virulent virus. We had passaged SHIV-4 sequentially in animals and derived a highly virulent virus stock (12, 13, 26). However, amplification of the env and nef genes from tissues of an animal, designated PPc, that died of SHIV-induced AIDS and insertion of these genes into the original SHIV-4 did not make the new virus, SHIVPPc, virulent or mitogenic. We therefore excised the nef/LTR region of SHIVPPc, inserted the corresponding region from SIVsmmPBj14, and reexamined the biological effects of the resultant virus. This new virus, SHIVPPcPBjnef, behaved similarly to SIVsmmPBj14 in inoculated cell cultures. The virus was highly mitogenic in resting PBMC, and infected cells produced virus in culture. However, surprisingly, the virus showed no evidence of causing activation of CD4+ T cells in vivo, and there was no productive infection in tissues of the infected animals. The new virus was eliminated more rapidly by the two inoculated macaques than was the SHIVPPc, which was inoculated into two other animals. These data show that the mechanisms by which SHIV causes activation and productive infection in resting PBMC are different from those that cause the same end result in vivo. Whether the dichotomy of biological effects of this virus in cell culture versus in vivo is due to its HIV-1 envelope is not known, but the phenomenon posed the question of whether the pathogenic mechanisms of SIV are different from those of HIV-1.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells, viruses, and plasmids.

The C8166 cell line was used as the source of indicator cells with which to measure the infectivity and cytopathicity of the viruses used in this study. C8166 cells were maintained in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10 mM HEPES buffer (pH 7.3), 2 mM glutamine, 50 μg of gentamicin per ml, and 10% fetal bovine serum (R10FBS). SIVmac239 was obtained from Ronald Desrosiers of the New England Regional Primate Center at Harvard University, and the SIVsmmPBj14 virus was obtained from James Mullins at the University of Washington. The derivation of SHIVKU-1 has been previously described (12, 13). The p3′SHIV-4 and p5′SHIV-4 plasmids were obtained from Joseph Sodroski of Harvard University.

SHIVPPc and SHIVPPcPBjnef, the construction of which is described below, were obtained from supernatant fluids of C8166 cultures 7 days after the cells had been transfected with the respective DNAs. Virus suspensions were assayed for infectivity by the use of the fusion cytopathicity technique in C8166 cells, and fresh stocks were prepared by inoculating the same cells at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 0.1 and harvesting of the supernatant fluids 7 days later. The stocks had titers of approximately 104 50% tissue culture infective doses (TCID50)/ml. A fresh stock of pathogenic SHIVKU-1 was also prepared in these cells for comparative purposes. This virus had a titer of 5 × 104 TCID50/ml.

Antibodies.

Serum was obtained from a macaque that had been inoculated with SHIVKU-1 and had developed neutralizing antibodies to the virus. By using a quantal cytopathic effect (CPE) assay in which doubling dilutions of serum were mixed with approximately 20 TCID50 of virus and incubated for 30 min at 37°C prior to inoculation of each virus-serum mixture into four wells of C8166 cells, we found that the serum had antibody titers of 1:15 against HIV HXB3, 1:100 against SHIV-4, and 1:15 against SHIVPPc. This serum had antibody titers of less than 1:10 against SHIVsmmPBj 14 and SIVmac239. Normal macaque serum did not neutralize any of the viruses.

Antibodies to Nef.

The SIVmac239 nef gene (with a corrected termination codon at amino acid position 92) was amplified from the plasmid p3′SHIV-4 by PCR, using the following oligonucleotides: 5′-GGGCTTTGCTATAACCATGGGAGCTATT-3′ (coding strand, with NcoI site underlined) and 5′-GCGAGTTTCCTTCTT-3′ (noncoding strand). The resulting amplified fragment contained an NcoI site at the beginning of the nef gene in addition to an internal NcoI site. The fragment was partially digested with NcoI and ligated into vector PET-11d which had been digested with NcoI and StuI (which results in a blunt end). The resulting plasmid, PET-SnefPFH, was transformed into Escherichia coli, and the Nef protein was expressed and purified as previously described (30). The purified Nef was used to generate an antiserum in rabbits that immunoprecipitates the SIVmac239 Nef protein.

Construction of SHIVPPc and SHIVPPcPBjnef.

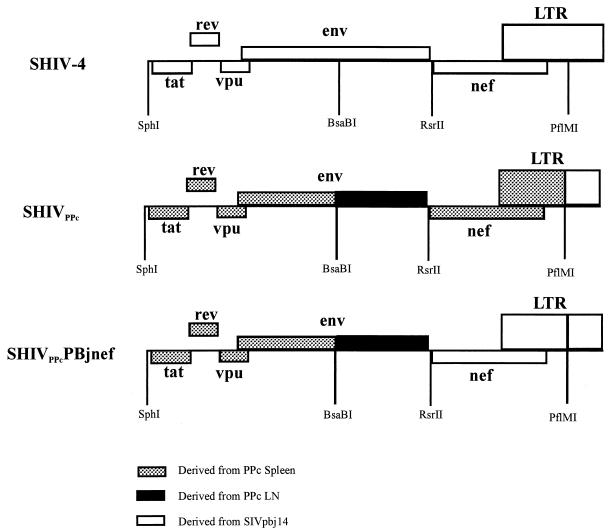

A schematic diagram of the construction of SHIVPPc is shown in Fig. 1.

FIG. 1.

Schematic diagram of the construction of the 3′ halves of the SHIVPPc and SHIVPPcPBjnef genomes. The origin of the DNA from macaque PPc that was used to amplify specific regions of the viral genome and the restriction endonuclease sites used to construct chimeric viruses SHIVPPc and SHIVPPcPBjnef are shown. LN, lymph node.

(i) SHIVPPc.

SHIVPPc was constructed by replacement of several regions of the 3′SHIV-4 genome with PCR-amplified products from spleen and lymph node tissue DNA obtained at necropsy from macaque PPc, which died of AIDS 26 weeks after inoculation with third-passage nonpathogenic SHIV-4 (13). SHIVPPc was constructed with three PCR-amplified regions that comprised the tat-gp120, gp120-gp41, and nef/LTR regions, as described below. For insertion of the tat-gp120 region, a DNA fragment that contained an SphI site at the 5′ end and a BsaBI site at the 3′ end was amplified. Total cellular DNA was extracted from spleen DNA obtained at necropsy, and 1 μg was used in a PCR with oligonucleotide primers 5′-GAGAACTCATTAGAATCCTCCAACGA-3′ (sense) and 5′-TTGCCCGGGTGGGTGCTACTCCTAATG-3′ (antisense). The amplification reaction mixture consisted of 1.4 mM MgSO4, 200 μM each of the four deoxynucleoside triphosphates, 100 pM each oligonucleotide primer, and a mixture of Taq and Pyrococcus species GB-D polymerases (Elongase; Gibco BRL). The template was denatured at 94°C for 2 min, and then PCR amplification was performed with an automated DNA thermal cycler (Perkin-Elmer Cetus) for 35 cycles, using the following profile: denaturation at 94°C for 30 s, annealing at 65°C for 1 min, and primer extension at 68°C for 5 min. Amplification was completed by incubation for 10 min at 68°C. The fragments were separated on an agarose gel, purified on GENECLEAN suspension (Bio101) and then cloned into the pGEM-T vector (Promega). Recombinants containing the SHIVPPc spleen tat-gp120 region were sequenced, and then one clone, designated pPPcSP1, was used for subcloning into the p3′SHIV-4 vector. The pPPcSP1 vector was digested with SphI and BsaBI, and the tat-gp120 region was separated on agarose gels and purified by using GENECLEAN. This fragment was subcloned into vector p3′SHIV-4 which had also been digested with SphI and BsaBI. The resulting plasmid was designated pSHIVPPc1.

For insertion of gp120-gp41 sequences from tissue variants of macaque PPc, spleen DNA was isolated and 1 μg was used in a PCR with oligonucleotide primers 5′-GTAGGAAAAGCAATGTATGCCCCTCCCATC-3′ (sense) and 5′-GAAATAGCTCCACCCATCATTGTAGG-3′ (antisense). The conditions for amplification were the same as described above for the tat-gp120 region. The resulting DNA fragment that was amplified contained a BsaBI site at the 5′ end and an RsrII site at the 3′ end. The fragments were separated on an agarose gel, purified on GENECLEAN, and then cloned into the pGEM-T vector (Promega). Recombinants containing the SHIVPPc spleen gp120-gp41 region were sequenced, and then one clone, designated pPPcLN1, was used for subcloning into the pSHIVPPc1 vector. The pPPcLN1 vector was digested with BsaBI and RsrII, and the gp120-gp41 region was separated on agarose gels and purified by using GENECLEAN. This fragment was subcloned into vector pSHIVPPc1 which had also been digested with BsaBI and RsrII. The resulting plasmid was designated pSHIVPPc2.

For insertion of nef/LTR sequences from macaque PPc, spleen DNA was isolated and 1 μg of it was used in a PCR with oligonucleotide primers 5′-CCACATACCTAGAAGAATAAGACA-3′ (sense) and 5′-TTTAAGCAAGCAAGCGTGGAGTCAC-3′ (antisense). The conditions for amplification were the same as described above for the tat-gp120 region. The DNA fragment that was amplified contained an RsrII site at the 5′ end and a PflMI site at the 3′ end. The fragments were separated on an agarose gel, purified on GENECLEAN, and then cloned into the pGEM-T vector (Promega). Recombinants containing the macaque PPc SHIV spleen nef/LTR region were sequenced, and then one clone, designated pPPcSP2, was used for subcloning into the pSHIVPPc2 vector. The pPPcSP2 vector was digested with RsrII and PflMI, and the nef/LTR region was separated on agarose gels and purified by using GENECLEAN. This fragment was subcloned into vector pSHIVPPc2 which had also been digested with RsrII and PflMI. The resulting plasmid was designated pSHIVPPc3.

Plasmid pSHIVPPc3 was sequenced to ensure that all of the PCR fragments were oriented correctly and that no premature stop codons or deletions were introduced during any of the three subcloning procedures. This plasmid was then used to generate infectious virus. Both p5′SHIV-4 and pSHIVPPc3 were digested with SphI to completion, ligated with T4 DNA ligase, and used to transfect C8166 cells by standard transfection protocols that had been previously established (19). Extensive CPE were observed within 4 days following transfection. Virus stocks were prepared and titrated in C8166 cells as previously described (13).

(ii) SHIVPPcPBjnef.

For construction of SHIVPPcPBjnef, oligonucleotide primers were designed to amplify the entire nef gene and part of the LTR region of SIVsmmPBj14, resulting in a DNA fragment that had an RsrII site at the 5′ end and a PflMI site at the 3′ end as shown in Fig. 1. SIVsmmPBj14 was inoculated into phytohemagglutinin (PHA)-stimulated rhesus macaque PBMC at an MOI of approximately 0.01, and the inoculated cells were incubated for 48 h at 37°C. Total cellular DNA was extracted, and 1 μg of genomic DNA was used in a PCR mixture containing 1.4 mM MgSO4, 200 μM each of the four deoxynucleotide triphosphates, 100 pM each oligonucleotide primer (5′-CAGCGGACCGACCTACAGTATGGGTGGCGTTACCTCCAAG-3′ [sense]; and 5′-GGAGAGATGGGAACACACACTGGCTTA-3′ [antisense]); the RsrII site is underlined and a mixture of Taq and Pyrococcus species GB-D polymerases (Elongase). The template was denatured at 94°C for 2 min, and then PCR amplification was performed with an automated DNA thermal cycler (Perkin-Elmer Cetus) for 35 cycles, using the following profile: denaturation at 94°C for 30 s, annealing at 65°C for 1 min, and primer extension at 68°C for 5 min. Amplification was completed by incubation for 10 min at 68°C. The end result of this PCR amplification was a DNA fragment containing a 1,131-bp portion of the nef/LTR region of SIVsmmPBj14 (the entire nef gene and part of the LTR of SIVsmmPBj14) with unique RsrII and PflMI sites at the 5′ and 3′ ends, respectively. The fragments were separated on an agarose gel, purified on GENECLEAN, and then cloned into the pGEM-T vector (Promega). Recombinants containing the SIVsmmPBj14 nef/LTR region were sequenced, and then one clone, designated pPBJnef, was selected for subcloning. The pPBJnef plasmid was digested with RsrII and PflMI to completion, and the 800-bp fragment corresponding to the nef/LTR region was purified by using GENECLEAN. This fragment was subcloned into 3′SHIVPPc that had also been digested to completion with RsrII and PflMI. The resulting 3′SHIVPPc recombinants containing the SIVsmmPBj14 nef/LTR region were identified and sequenced to ensure that the PCR fragments were oriented correctly and that no premature stop codons or deletions were introduced during the subcloning procedure. The resulting plasmid, p3′SHIVsmmPBjnef, was used to generate infectious virus. Both p5′-SHIV-4 and p3′SHIVsmmPBjnef were digested with SphI to completion, ligated with T4 DNA ligase, and used to transfect C8166 cells by standard transfection protocols that had been previously established (19). CPE were observed within 4 days following transfection. Virus stocks were prepared and titrated in C8166 cells as previously described (13).

Immunoprecipitation assays.

Immunoprecipitation assays were performed to assess the expression of Nef in SIVsmmPBj14-, SHIVPPc-, or SHIVPPcPBjnef-infected cells. A dose of 104 TCID50 of each virus was used to inoculate cultures of C8166 cells. Cultures were incubated at 37°C for 5 days, at which time the cells were centrifuged and then incubated in medium lacking methionine and cysteine for 2 h. The cells were then radiolabeled with 200 μCi of [35S]methionine-[35S]cysteine for 18 h, cell lysates were prepared, and Nef proteins were immunoprecipitated with an anti-Nef serum (prepared against recombinant SIVmac239 Nef) and protein A-Sepharose as previously described (27, 28). Immunoprecipitates were washed three times in radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer, and samples were denatured by boiling in sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) sample-reducing buffer. Proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE (8.5% gel) (16) and visualized by standard autoradiographic techniques.

Assessment of the mitogenic activity and replication of virus in resting PBMC.

Heparinized blood from normal pig-tailed macaques was used, and PBMC suspensions were prepared by centrifugation on Ficoll-Hypaque gradients as described previously (11). The PBMC were suspended in R10FBS without interleukin-2 (IL-2) supplementation at a concentration of 106 cells/ml and inoculated with virus at an MOI of approximately 0.1 or less. The cells were maintained in a 37°C incubator as bulk suspension cultures in Teflon bottles. At specific intervals, 1-ml aliquots (106 cells) of uninoculated and virus-inoculated cultures were removed, and the cells were rinsed in fresh medium and pulsed with 1.25 μCi of [3H]thymidine for 16 h. The cells were then harvested, and the amount of incorporated [3H]thymidine was determined by scintillation spectroscopy.

To confirm the HIV-1 envelope glycoprotein specificity of the test virus, pre- and postinoculation sera (heated at 56°C for 30 min) containing neutralizing antibodies to SHIV were separately added to portions of the virus suspension, and the mixtures were incubated for 30 min at 37°C prior to inoculation into PBMC cultures. The PBMC were then processed for [3H]thymidine incorporation as described above. To assess virus replication in inoculated PBMC, 5-ml aliquots of virus-inoculated bulk cultures were removed 24 h after inoculation, and the cells were washed three times in 10 ml of R10FBS and then reincubated in R10FBS. Aliquots of culture medium were removed at daily intervals and assayed for SIVmac p27 levels by a commercial antigen capture assay (Coulter Corp., Hialeah, Fla.).

Macaques and inoculation procedures.

Four 2-year-old pig-tailed macaques were each inoculated intravenously with 1 ml of undiluted virus stock containing 104 TCID50; macaques 19B and 19C were inoculated with SHIVPPc, and macaques 25A and 25B were inoculated with SHIVPPcPBjnef. The animals were housed in our American Association for the Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care-approved animal facility and evaluated weekly for the development of infection. Heparinized blood specimens were collected weekly for the first 4 weeks, at 2-week intervals for the next 4 weeks, and then monthly thereafter.

Processing of tissues and virus assays.

Blood was centrifuged to separate the plasma and buffy coat. Plasma samples were assayed directly for infectivity in C8166 cells as well as for p27 levels; some plasma was also stored for later determination of antibody content. PBMC, obtained by centrifugation of buffy coats on Ficoll-Hypaque columns, were assayed for virus content as described previously. The numbers of cells in PBMC suspensions producing infectious virus were determined by infectious center assays (ICA) (11), and other aliquots of the cells were examined specifically for productive infection (the presence of virus in culture medium of PBMC incubated for 7 days in R10FBS without IL-2). Latent infection (the presence of virus in supernatant fluid of CD8-depleted PBMC stimulated with PHA for 3 days followed by culture in R10FBS plus IL-2 for 7 days) was also assessed. Following euthanasia of the animals, tissue specimens were collected and assayed for infectivity in homogenates as well as suspensions of cells from lymphoid tissues in C8166 cell cultures. Other portions of tissues were fixed in 10% buffered formalin and processed for routine histopathological examination.

PCR analysis for the presence of viral sequences in tissues.

Tissues from inoculated animals were screened for the presence of SHIV sequences by PCR with oligonucleotide primers specific for both SIV and SHIV (21, 22). Total cellular genomic DNA was extracted from six visceral organs (liver, spleen, mesenteric lymph node, lung, thymus, and kidney) and from 12 regions of the central nervous system (frontal, parietal, occipital, and temporal cortices; hippocampus; internal capsule; basal ganglia; midbrain; brain stem; cerebellum; and cervical, thoracic, and lumbar regions of the spinal cord). The DNA was used as a template in nested PCRs (21, 22) to amplify SIV gag sequences which were common to both viruses. The gag-specific oligonucleotides and the conditions for amplification were exactly as described previously (14, 20).

We also used PCR to show that the nef/LTR region in the tissues isolated from macaques 25A and 25B were derived from SIVsmmPBj14. Cellular DNA derived from lymph node tissue was subjected to PCR with oligonucleotide primers that would specifically amplify either the nef/LTR region of SIVmac239 or the corresponding region of SHIVPPcPBjnef (i.e., derived from SIVsmmPBj14). For amplification of the nef/LTR region from SIVsmmPBj14, 1 μg of DNA was amplified by PCR with oligonucleotides 5′-CCTACCTACAGTATGGGTGGCGTTACCTCCAAG-3′ (coding strand) and 5′-ATGCAGTTGTATTTATACAGAAAGTAC-3′ (noncoding strand), using the conditions described above for amplification of the SIVsmmPBj14 nef/LTR region. The oligonucleotides and conditions for amplification of the SIVmac239 nef were the same as those described previously (31).

RESULTS

Construction of SHIVPPc and SHIVPPcPBjnef.

A summary of the predicted amino acid substitutions that were found in the predicted Tat, Rev, Vpu, Env, and Nef protein sequences of SHIVPPc is shown in Table 1. Amplification and subcloning of viral genomic regions from the spleen and lymph nodes of macaque PPc showed that the PPc virus genome had 33 amino acid substitutions compared to the parental SHIV-4 virus. The predicted Tat protein had one change, a serine-to-proline substitution at position 77. The vpu gene, which in SHIV-4 originally had an ACG codon at the beginning of the gene and did not code for a functional Vpu protein (17), reverted to a form containing a functional ATG initiation codon. In addition to the methionine change at position 1, there was a proline-to-threonine change at position 76. The predicted amino acid sequence of the envelope glycoprotein, gp160, had a total of 20 amino acid substitutions (14 in gp120 and 6 in gp41) compared to SHIV-4, and the predicted Nef protein had a total of 9 amino acid substitutions.

TABLE 1.

Amino acid substitutions in the genome of SHIVPPc

| Genea | Amino acid no. | Amino acid change |

|---|---|---|

| tat | 77 | S→P |

| vpu | 1 | T→M |

| 76 | P→T | |

| env | 65 | V→A |

| 94 | D→N | |

| 130 | K→N | |

| 175 | F→L | |

| 192 | S→T | |

| 202 | T→S | |

| 278 | T→M | |

| 320 | I→M | |

| 325 | N→D | |

| 345 | I→L | |

| 460 | N→I | |

| 461 | S→G | |

| 470 | L→G | |

| 476 | R→K | |

| 518 | L→V | |

| 533 | A→R | |

| 626 | T→M | |

| 723 | I→T | |

| 781 | I→T | |

| 825 | G→R | |

| nef | 24 | R→C |

| 63 | G→E | |

| 71 | R→K | |

| 77 | R→K | |

| 130 | E→G | |

| 136 | A→P | |

| 144 | I→M | |

| 150 | E→K | |

| 188 | E→K |

There were no changes in the rev gene.

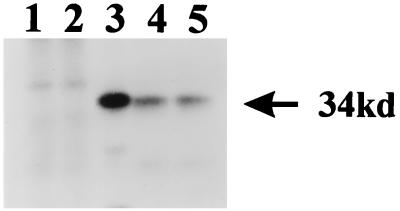

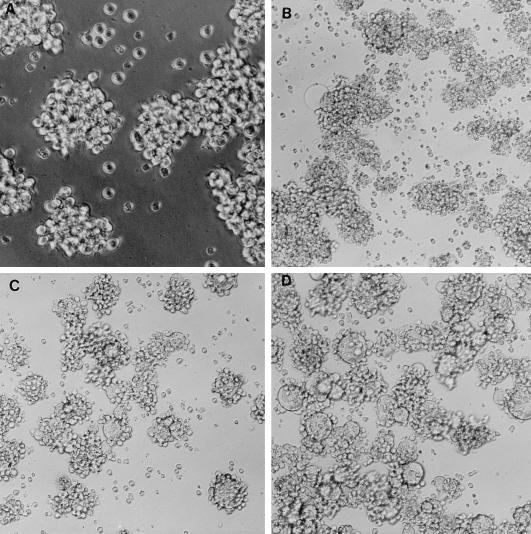

The predicted amino acid sequence of the Nef protein in SHIVPPcPBjnef was compared to the reported sequence for SIVsmmPBj14-mcl-1.9 Nef. A total of three amino acid differences (a glutamic acid to cysteine substitution at position 26, a methionine to threonine substitution at position 66, and an alanine to threonine substitution at position 255) between the SHIVPPc PBjnef Nef and that of the pathogenic molecular clone SIVsmmPBj14-mcl-1.9 were found (2). None of the three amino acid substitutions was within the YXXL motifs reported to be important for the mitogenic activity of Nef and for acute pathogenicity of SIVsmmPBj14-mcl-1.9 (3, 4). The expression of Nef in cultures of C8166 cells inoculated with the viruses was assessed by immunoprecipitation studies. Cultures were inoculated with SHIVPPc, SHIVPPcPBjnef, or SIVsmmPBj14 for 5 days and then radiolabeled, and the Nef was immunoprecipitated with an anti-Nef antiserum. The Nef protein of SIVmac239 is 263 amino acids in length, whereas SIVsmmPBj14 Nef is 261 amino acids in length. As shown in Fig. 2, a protein with an apparent relative molecular weight of 34,000 was immunoprecipitated from SIVPPc-, SIVPPcPBjnef-, or SIVsmmPBj14-infected cells but not from cultures inoculated with SHIVPPcΔnef or from uninfected cultures. These results indicate that SIVsmmPBj14 Nef was stably expressed in cultures of C8166 cells inoculated with SIVPPcPBjnef. We also examined the cytopathology in C8166 cells following their inoculation with these viruses. Inoculation of C8166 cultures with either SIVPPc or SIVPPcPBjnef resulted in much more extensive cytopathology than that observed in C8166 cells inoculated at an equivalent MOI with SHIV-4, suggesting that the amino acid changes in SHIVPPc resulted in a virus that was more cytopathic for C8166 cells (Fig. 3). Similar results were obtained for macaque PBMC cultures inoculated with these viruses (data not shown). However, although SIVPPc and SIVPPc PBjnef were more cytopathic for lymphocyte cultures, the levels of p27 produced in these cultures were similar to those of cultures inoculated with SHIV-4 (data not shown).

FIG. 2.

Immunoprecipitation analyses demonstrate that Nef is synthesized in SHIVPPc-infected cells. SHIVPPcΔnef, SHIVPPc, SHIVPPcPBjnef, or SIVSmmPBj14 (103 TCID50 each) was used to inoculate C8166 cells. At 4 days postinoculation, cells were starved for methionine and cysteine and radiolabeled with 200 μCi of [35S]methionine-[35S]cysteine for 18 h. Cell lysates were prepared as previously described (27, 28), and SHIV proteins were immunoprecipitated with a rabbit anti-Nef serum and protein A-Sepharose as described in the text. Immunoprecipitates were washed three times in radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer, and samples were denatured by boiling in SDS-PAGE sample-reducing buffer. Proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE (8.5% gel) and visualized by standard autoradiographic techniques. Lanes: 1, proteins immunoprecipitated from uninfected C8166 cells; 2, proteins immunoprecipitated from C8166 cells inoculated with SHIVPPc with the nef gene deleted; 3, proteins immunoprecipitated from C8166 cells inoculated with SHIVPPc; 4, proteins immunoprecipitated from C8166 cells inoculated with SHIVPPcPBjnef; 5, proteins immunoprecipitated from C8166 cells inoculated with SIVsmmPBj14.

FIG. 3.

Photomicrographs of C8166 cultures following inoculation with various SHIVs. C8166 cultures were inoculated with 103 TCID50 of SHIV-4, SHIVPPc, or SHIVPPcPBjnef. At the peak period of cytopathology (4 days), the cultures were photographed. (A) Uninfected C8166 culture; (B) SHIV-4-inoculated culture; (C) SHIVPPc-inoculated culture; (D) SHIVPPcPBjnef-inoculated culture. Magnifications, ×200 (A) and ×100 (B to D).

SHIVPPcPBjnef, but not SHIVPPc, has mitogenic activity in resting PBMC.

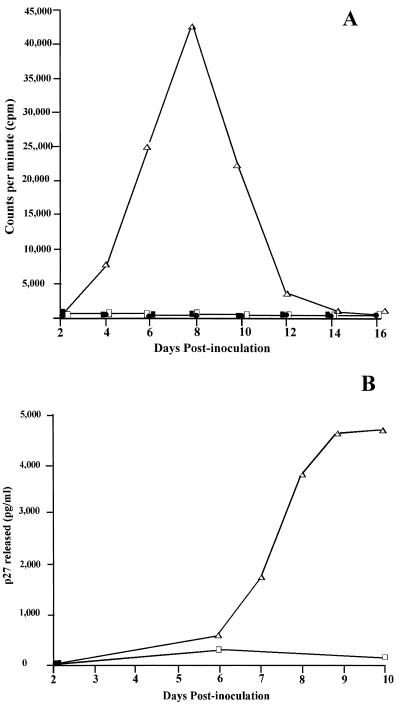

We examined whether SHIVPPcPBjnef had mitogenic activity following its inoculation into resting PBMC. Cultures of resting PBMC in R10FBS were inoculated with SHIVPPc, SHIVPPcPBjnef, or SHIVKU-1. As shown in Fig. 4A, uninoculated cultures and those inoculated with SHIVKU-1 or SHIVPPc showed no incorporation of [3H]thymidine. In contrast, PBMC inoculated with SHIVPPcPBjnef showed incorporation of [3H]thymidine, beginning at day 5 and peaking at day 9. The mitogenic activity associated with SHIVPPcPBjnef was also reflected in the ability of this virus to replicate in PBMC. As shown in Fig. 4B, the level of p27 released from SHIVPPcPBjnef-inoculated cultures rapidly increased from day 6 to day 10 postinoculation. The mitogenic activity of SHIVPPcPBjnef and its ability to replicate in resting PBMC were similar to those observed in resting PBMC inoculated with SIVsmmPBj14 (data not shown).

FIG. 4.

Mitogenic activity (A) and replication (B) of SHIVPPcPBjnef in resting PBMC. (A) Resting PBMCs (107) were inoculated with 103 TCID50 of SHIVPPc (▪), SHIVPPcPBjnef (▵), or SHIVKU-1 (•), and mitogenic activity was monitored by determination of [3H]thymidine incorporation until day 16. □, control (uninoculated resting PBMC) cultures. (B) Replication of SHIVPPc PBjnef and SHIVPPc in cultures of resting PBMC. Resting PBMC (107) were inoculated with SHIVPPc (□) or SHIVPPcPBjnef (▵), and virus replication was assessed by standard p27 antigen capture assay.

We also determined whether preincubation of SHIVPPc PBjnef with neutralizing antibodies to SHIV would prevent the mitogenic activity observed in cultures inoculated with SHIVPPcPBjnef. Incubation of this virus with preimmune plasma resulted in no decrease in mitogenic activity. However, preincubation of the virus with SHIV-neutralizing antibodies derived from macaque 14A totally abolished p27 production (data not shown). The lack of p27 release into the culture medium in the presence of neutralizing antibodies to SHIV suggested that the observed mitogenic activity was SHIV specific.

SHIVPPc and SHIVPPcPBjnef are nonpathogenic for pig-tailed macaques.

The mitogenic properties of SHIVPPcPBjnef so closely resembled those of SIVsmmPBj14 and SIVmac239/PBj nef that we inoculated two macaques with the virus to determine whether similar effects would occur in vivo and thereby reveal heightened virulence. Two macaques, 19B and 19C, were inoculated with SHIVPPc, and two others, macaques 25A and 25B, were inoculated with SHIVPPcPBjnef. No viral p27 was detected in three of the four macaques, and virus was detected in the plasma from macaques 19B and 19C at only one time point (week 1). None of the four animals became viremic with infectious virus or had viral p27 in its plasma (Tables 2 and 3). Productively infected cells were undetectable because cultured PBMC failed to produce virus in R10FBS medium. PBMC treated with PHA and then cultured in medium containing IL-2 produced virus only during the first 2 weeks following inoculation. SHIVPPc was routinely rescued from PBMC of the two inoculated animals during the first 3.5 months, whereas, paradoxically, no virus could be obtained from PBMC of the two SHIVPPcPBjnef-inoculated animals beyond 4 weeks. CD4+ T-cell counts remained normal throughout, and the animals remained healthy. At necropsy, none of the tissues exhibited histopathological abnormalities and no virus could be rescued from lymphoid tissues or the central nervous system (CNS). Histopathological examination did not reveal the severe diffuse hyperplasia of gut-associated lymphoid tissue (GALT) characteristic of SIVsmmPBj14 infection. Thus, both viruses lacked virulence, their replication being brought under control promptly by defense mechanisms of the animals. None of the mitogenic effects of SHIVPPcPBjnef that had been seen in cell culture systems were observed in vivo. In fact, replication of this virus was brought under control faster than that of SHIVPPc, which was inoculated into two other animals.

TABLE 2.

Virus burdens in macaques inoculated with SHIVPPc

| Macaque | Wk postinoculation | ICA resulta | Plasma viremiab | Plasma p27 level (pg/ml) | No. of CD4+ cells/ml |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 19B | 0 | 0 | NDc | ND | 1,740 |

| 1 | 100 | + | 0 | 1,237 | |

| 2 | 10 | − | 0 | 1,047 | |

| 4 | 100 | − | 0 | 882 | |

| 6 | 10 | − | 0 | 854 | |

| 9 | 1 | − | 0 | 1,236 | |

| 14 | 10 | − | 0 | 874 | |

| 23 | 0 | − | 0 | 1,607 | |

| 32 | 0 | − | ND | 1,673 | |

| 40 | 0 | − | 0 | 719 | |

| 43 | 0 | − | ND | 952 | |

| 19C | 0 | 0 | ND | ND | 2,557 |

| 1 | 100 | + | 297 | 1,334 | |

| 2 | 1,000 | − | 0 | 618 | |

| 4 | 10,000 | − | 0 | 599 | |

| 6 | 10 | − | 0 | 672 | |

| 9 | 2 | − | 0 | 639 | |

| 14 | 100 | − | 0 | 879 | |

| 23 | 0 | − | 0 | 1,373 | |

| 32 | 0 | − | ND | 1,056 | |

| 40 | 0 | − | 0 | 832 | |

| 42 | 1 | − | ND | 827 |

ICA results are expressed as the number of positive cells per 106 PBMC.

+, viremia exhibited; −, no viremia exhibited.

ND, not done.

TABLE 3.

Virus burdens in macaques inoculated with SHIVPPcPBjnefa

| Macaque | Wk postinoculation | ICA resultb | No. of CD4+ cells/ml |

|---|---|---|---|

| 25A | 0 | 0 | 3,114 |

| 1 | 100 | 2,590 | |

| 3 | 100 | 2,456 | |

| 4 | 100 | 2,049 | |

| 6 | 10 | 190 | |

| 9 | 0 | 1,247 | |

| 11 | 0 | 1,267 | |

| 13 | 0 | 2,462 | |

| 14 | 0 | 1,240 | |

| 25B | 0 | 0 | 1,688 |

| 1 | 100 | 1,431 | |

| 3 | 100 | 1,071 | |

| 4 | 1,000 | 1,181 | |

| 6 | 0 | 693 | |

| 9 | 0 | 2,710 | |

| 11 | 0 | 1,732 | |

| 13 | 0 | 1,334 | |

| 17 | 0 | 1,385 |

For both macaques, no plasma viremia was found at any time point, and the p27 antigen was not detected at any time point at which a determination was made.

ICA results are expressed as the number of positive cells per 106 PBMC.

Because previous studies had shown that SHIV could invade and establish a persistent infection in the brain, we examined multiple regions of the CNS and six visceral organs by nested PCR to determine the distribution of SHIVPPc and SHIVPPcPBjnef viral sequences. The results, shown in Table 4, indicated that among the four macaques inoculated with SHIVPPc or SHIVPPcPBjnef, none of the regions of the CNS examined by nested PCR was positive for virus sequences, indicating the failure of both viruses to invade the CNS. Examination of six visceral organs revealed that only the lymph node and spleen were positive for SHIV sequences in all four animals. We also compared the distribution of viral sequences in these four macaques with that in macaque PPc, from which were derived the viral sequences used to construct SHIVPPc and SHIVPPcPBjnef. All of the visceral organs (lymph nodes, spleen, lungs, liver, and kidneys) and 3 of 14 regions of the CNS were positive for viral sequences. Thus, there was no widespread virus dissemination, a phenomenon that usually accompanies activation of infected T cells. PCR analysis using oligonucleotides that amplified the nef/LTR region of SIVsmmPBj14 also revealed that regions from macaques 25A and 25B which were positive for gag sequences were also positive for SIVsmmPBj14 sequences (data not shown).

TABLE 4.

Presence of viral sequences in tissues from macaque PPc and from macaques inoculated with SHIVPPc or SHIVPPcPBjnefa

| Tissue | Presence of viral sequence in macaqueb:

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 19Bc | 19Cc | 25Ad | 25Bd | PPc | |

| Visceral | |||||

| Mesenteric lymph node | + | + | + | + | + |

| Spleen | + | + | + | + | + |

| Liver | − | − | − | + | + |

| Lung | − | − | − | − | + |

| Kidney | − | − | − | − | + |

| Central nervous system | |||||

| Brain | |||||

| Cortex | |||||

| Frontal | − | − | − | − | − |

| Parietal | − | − | − | − | + |

| Occipital | − | − | − | − | − |

| Temporal | − | − | − | − | − |

| Motor | − | − | − | − | − |

| Hippocampus | − | − | − | − | − |

| Internal capsule | − | − | − | − | + |

| Basal ganglia | − | − | − | − | + |

| Thalamus | − | − | − | − | − |

| Midbrain | − | − | − | − | − |

| Pons | − | − | − | − | − |

| Medulla | − | − | − | − | − |

| Cerebellum | − | − | − | − | − |

| Spinal cord regions | |||||

| Cervical | − | − | − | − | − |

| Thoracic | − | − | − | − | − |

| Lumbar | − | − | − | − | − |

Tissue DNAs were used in a nested PCR with oligonucleotide primers that amplified the gag gene of SHIV.

+, SHIVPPc or SHIVPPcPBjnef sequence present; −, viral sequence not detected.

SHIVPPc-inoculated macaque.

SHIVPPcPBjnef-inoculated macaque.

DISCUSSION

Previous studies by Du et al. (4) had shown that the ability of SIVsmmPBj14 to cause disease and to activate and replicate in resting PBMC could be mapped to the nef gene. Earlier studies had shown that the Nef protein of SIVsmmPBj14 has a consensus SH2 binding domain consisting of three YXX(L/S) repeats interspaced by 7 amino acids. Use of site-directed mutagenesis to create this SH2 domain in the Nef protein of SIVmac239, a virus that generally causes AIDS in macaques with a median time of 22 months following inoculation (1, 15, 20), yielded a virus that had mitogenic activity and caused a hyperacute SIVsmmPBj14-like disease following inoculation into pig-tailed macaques. An additional study showed that the arginine-to-tyrosine change at position 17 of Nef was the only requirement for conversion of SIVmac239 to a virus with the lymphocyte-activating properties of SIVsmmPBj14 (3). We exploited these findings to determine if expression of the SIVsmmPBj14 nef gene in a nonpathogenic primate lentivirus, SHIVPPc, would result in a virus that causes an acute SIVsmmPBj14-like disease in macaques. Immunoprecipitation and nucleotide sequence analysis confirmed that the recombinant viruses contained the SIVsmmPBj14 nef/LTR region with the consensus SH2 domain described earlier by Du et al. (4), and cell culture studies showed that the virus was mitogenic in PBMC. Furthermore, the inoculated cells produced virus. These events were similar to those described for the SIVsmmPBj14 and SIVmac239 nef genes. However, despite its enhanced in vitro mitogenic potential, SHIVPPcPBjnef did not exert this potential in vivo. This showed that factors regulating mitogenesis in vitro are distinct from those regulating these processes in vivo. The mitogenic properties of the virus were dependent on infection in the cells, since preincubation of the virus with neutralizing antibodies to SHIV prevented infection and subsequent mitogenesis. Thus, while this confirmed the requirement of the HIV-1 envelope glycoprotein for the initiation of the process, it is clear that the SIVsmmPBj14 Nef protein was responsible for the mitogenic effects. Because of its lack of in vivo mitogenic effects, the SHIVPPcPBjnef virus failed to cause an SIVsmmPBj14-like disease in pig-tailed macaques, which usually occurs within 14 days after inoculation of these animals with SIVsmmPBj14 (6–9). Although the virus had a low replicative capacity in vivo, virus-producing PBMC could be detected by ICA for up to 6 weeks after inoculation, thus proving the occurrence of a systemic infection. In addition, viral DNA was detected in the mesenteric lymph node tissue. Based on these findings, we believe that virus-infected cells had adequate time to infect and productively replicate in the GALT. However, histopathological examination did not reveal the occurrence of hyperplasia in any lymphoid tissue, including the GALT, or the generalized maculopapular rash associated with SIVsmmPBj14 infection. In fact, our data suggest that SHIVPPcPBjnef was more effectively controlled than SHIVPPc, which expressed the SIVmac239 Nef protein. Thus, expression of the SIVsmmPBj14 Nef protein in SHIV actually resulted in a virus that was less replication competent in vivo.

The biological effects of SHIVPPcPBjnef contrasted dramatically with those of SHIVKU-1. Whereas the former virus was highly mitogenic in vitro, SHIVKU-1 lacked this ability. On the other hand, unlike SHIVPPcPBjnef, SHIVKU-1 is highly pathogenic. Further, the pathogenic effects of SHIVKU-1 are distinct from those of SIVsmm PBj14, since SHIVKU-1 causes a highly productive and lytic infection in CD4+ T cells that results in their elimination whereas SIVsmmPBj14 and SIVmac239PBj nef caused a proliferative response of the T cells with a resultant toxic production of cytokines (24). The mechanisms by which one virus caused a lytic infection in CD4+ T cells whereas the other caused a productive proliferative response of the cells in vivo are poorly understood. However, given the incongruence of the mitogenic potential of SHIVPPcPBjnef in vitro versus its failure to cause these effects in vivo, it may be risky to ascribe pathogenic potential to any lentivirus that has the ability to activate resting T cells, since this effect may not be reproducible in vivo. Alternatively, the dual mitogenic effect may be peculiar to the SIVs.

One possible explanation for the lack of pathogenicity of the SHIVPPcPBjnef is that the substituted nef/LTR region alone is not responsible for causing the disease and that an interaction between the SIVsmmPBj14 Nef and another SIV protein may be required for expression of its full pathogenic potential. One such interaction could involve the envelope and the Nef protein, and in this SHIV construct, the HIV-1 envelope glycoprotein from SHIVPPc (derived from HIV-1 strain HXB2 and highly divergent from SIVmac239 at the amino acid level) could not interact optimally with the PBj Nef protein. Whatever the reason, it is clear that there was no linkage between the cell culture phenomenon and the pathogenesis of SIVsmmPBj14 in pig-tailed macaques.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The work reported here was supported by grants AI-29382, NS-32203, RR-06753, and DK-49516 from the National Institutes of Health and by the Max Planck Institute of Germany.

We thank the Cetus Corp. for the recombinant human IL-2 and the Genetics Institute for the macrophage colony-stimulating factor and the granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor. We also thank Erin McDonough for help in preparing the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Desrosiers R C. Non-human primate models for AIDS vaccines. AIDS. 1995;9:S137–S141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dewhurst S, Embretson J E, Anderson D C, Mullins J I, Fultz P N. Sequence analysis and acute pathogenicity of molecularly cloned SIVsmm-PBj14. Nature. 1990;345:636–640. doi: 10.1038/345636a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Du Z, Ilyinskii P O, Sasseville V G, Newstein M, Lackner A A, Desrosiers R C. Requirements for lymphocyte activation by unusual strains of simian immunodeficiency virus. J Virol. 1996;70:4157–4161. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.6.4157-4161.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Du Z, Lang S M, Sasseville V G, Lackner A A, Ilyinskii P O, Daniel M D, Jung J U, Desrosiers R C. Identification of a nef allele that causes lymphocyte activation and acute disease in macaque monkeys. Cell. 1995;82:665–674. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90038-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Folks T, Kelly J, Benn S, Kinter A, Justement J, Gold J, Redfield R, Sell K W, Fauci A S. Susceptibility of normal human lymphocytes to infection with HTLV-III/LAV. J Immunol. 1986;136:4049–4053. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fultz P N. Replication of an acutely lethal simian immunodeficiency virus activates and induces proliferation of lymphocytes. J Virol. 1991;65:4902–4909. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.9.4902-4909.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fultz P N. SIVsmmPBj14: an atypical lentivirus. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1994;188:65–76. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-78536-8_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fultz P N, McClure H M, Anderson D C, Switzer W M. Identification and biologic characterization of an acutely lethal variant of simian immunodeficiency virus from sooty mangabeys (SIV/SMM) AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 1989;5:397–409. doi: 10.1089/aid.1989.5.397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fultz P N, Zack P M. Unique lentivirus-host interactions: SIVsmmPBj14 infection of macaques. Virus Res. 1994;32:202–225. doi: 10.1016/0168-1702(94)90042-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Israel Z R, Dean G A, Maul D H, O’Neil S P, Dreitz M J, Mullins J I, Fultz P N, Hoover E A. Early pathogenesis of disease caused by SIVsmmPBj14 molecular clone 1.9 in macaques. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 1993;9:277–286. doi: 10.1089/aid.1993.9.277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Joag S V, Adams R J, Foresman L, Galbreath D, Zink M C, Pinson D M, McClure H, Narayan O. Early activation of PBMC and appearance of antiviral CD8+ cells influence the prognosis of SIV-induced disease in rhesus macaques. J Med Primatol. 1994;23:108–116. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0684.1994.tb00110.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Joag S V, Li Z, Foresman L, Pinson D M, Raghavan R, Zhuge W, Adany I, Wang C, Jia F, Sheffer D, Ranchalis J, Watson A, Narayan O. Characterization of the pathogenic KU-SHIV model of AIDS in macaques. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 1997;13:635–645. doi: 10.1089/aid.1997.13.635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Joag S V, Li Z, Foresman L, Stephens E B, Zhao L-J, Adany I, Pinson D M, McClure H M, Narayan O. Chimeric simian/human immunodeficiency virus that causes progressive loss of CD4+ T cells and AIDS in pig-tailed macaques. J Virol. 1996;70:3189–3197. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.5.3189-3197.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Joag S V, Stephens E B, Adams R J, Foresman L, Narayan O. Pathogenesis of SIVmac infection in Chinese and Indian rhesus macaques: effects of splenectomy on virus burden. Virology. 1994;200:436–446. doi: 10.1006/viro.1994.1207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kestler H, Kodama T, Ringler D, Marthas M, Pedersen N, Lackner A, Regier D, Sehgal P, Daniel M, King N, Desrosiers R C. Induction of AIDS in rhesus monkeys by molecularly cloned simian immunodeficiency virus. Science. 1990;248:1109–1112. doi: 10.1126/science.2160735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Laemmli U K. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li J, Lord C I, Haseltine W, Letvin N L, Sodroski J. Infection of cynomolgus monkeys with a chimeric HIV-1/SIVmac virus that expresses the HIV-1 envelope glycoproteins. J Acquired Immune Defic Syndr. 1992;5:639–646. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Luciw P A. Human immunodeficiency viruses and their replication. In: Fields B N, Knipe D M, Howley P M, editors. Fields virology. Philadelphia, Pa: Lippincott-Raven Publishers; 1996. pp. 1881–1952. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Milman G, Herzberg M. Efficient DNA transfection and rapid thymidine kinase activity and viral antigenic determinants. Somatic Cell Genet. 1981;7:161–170. doi: 10.1007/BF01567655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Regier D A, Desrosiers R C. The complete sequence of a pathogenic molecular clone of simian immunodeficiency virus. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 1990;6:1221–1231. doi: 10.1089/aid.1990.6.1221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Saiki R K, Gelfand D H, Stoffel S, Scharf S J, Higuchi R, Horn G T, Mullis K B, Erlich H A. Primer-directed enzymatic amplification of DNA with a thermostable DNA polymerase. Science. 1988;239:487–491. doi: 10.1126/science.2448875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Saiki R K, Scharf S, Faloona F, Mullis K B, Horn G T, Erlich H A, Arnheim N. Enzymatic amplification of β-globin genomic sequences and restriction site analysis for diagnosis of sickle cell anemia. Science. 1985;230:1350–1354. doi: 10.1126/science.2999980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schnittman S M, Fauci A S. Human immunodeficiency virus and acquired immunodeficiency syndrome: an update. Adv Intern Med. 1994;39:305–355. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schwiebert R, Fultz P N. Immune activation and viral burden in acute disease induced by simian immunodeficiency virus SIVsmmPBj14: correlation between in vitro and in vivo events. J Virol. 1994;68:5538–5547. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.9.5538-5547.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sharma D P, Anderson M, Zink M C, Adams R J, Donnenberg A D, Clements J E, Narayan O. Pathogenesis of acute infection in rhesus macaques with a lymphocyte-tropic strain of simian immunodeficiency virus. J Infect Dis. 1992;166:738–746. doi: 10.1093/infdis/166.4.738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stephens E B, Joag S V, Sheffer D, Liu Z Q, Zhao L J, Mukherjee S, Foresman L, Adany I, Li Z, Pinson D, Narayan O. Initial characterization of viral sequences from a SHIV-inoculated pig-tailed macaque that developed AIDS. J Med Primatol. 1996;25:175–185. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0684.1996.tb00014.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stephens E B, McClure H M, Narayan O. The proteins of lymphocyte- and macrophage-tropic strains of simian immunodeficiency virus are processed differently in macrophages. Virology. 1995;206:535–544. doi: 10.1016/s0042-6822(95)80070-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stephens E B, Mukherjee S, Sahni M, Zhuge W, Raghavan R, Singh D K, Leung K, Atkinson B, Li Z, Joag S V, Liu Z Q, Narayan O. A cell-free stock of simian-human immunodeficiency virus that causes AIDS in pig-tailed macaques has a limited number of amino acid substitutions in both SIVmac and HIV-1 regions of the genome and has altered cytotropism. Virology. 1997;231:313–321. doi: 10.1006/viro.1997.8534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zack J A, Arrigo S J, Weitsman S R, Go A S, Haislip A, Chen I S Y. HIV-1 entry into quiescent primary lymphocytes: molecular analysis reveals a labile, latent viral structure. Cell. 1990;61:213–222. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90802-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhao L-J, Narayan O. A gene expression vector useful for purification and studies of protein-protein interaction. Gene. 1993;137:345–346. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(93)90032-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhu G W, Mukherjee S, Sahni M, Narayan O, Stephens E B. Prolonged infection in rhesus macaques with simian immunodeficiency virus (SIVmac239) results in animal-specific and rarely tissue-specific selection of nef variants. Virology. 1996;220:522–529. doi: 10.1006/viro.1996.0342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]