Abstract

Background

International consensus on cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) and emergency cardiovascular care science and treatment recommendations (CoSTR) have reported updates on CPR maneuvers every 5 years since 2000. However, few national population‐based studies have investigated the comprehensive effectiveness of those updates for out‐of‐hospital cardiac arrest due to shockable rhythms. The primary objective of the present study was to determine whether CPR based on CoSTR 2005 or 2010 was associated with improved outcomes in Japan, as compared with CPR based on Guidelines 2000.

Methods and Results

From the All‐Japan Utstein Registry between 2005 and 2015, we included 73 578 adults who had shockable out‐of‐hospital cardiac arrest witnessed by bystanders or emergency medical service responders. The study outcomes over an 11‐year period were compared between 2005 of the Guidelines 2000 era, from 2006 to 2010 of the CoSTR 2005 era, and from 2011 to 2015 of the CoSTR 2010 era. In the bystander‐witnessed group, the adjusted odds ratios for favorable neurological outcomes at 30 days after out‐of‐hospital cardiac arrest by enrollment year increased year by year (1.19 in 2006, and 3.01 in 2015). Similar results were seen in the emergency medical service responder‐witnessed group and several subgroups.

Conclusions

Compared with CPR maneuvers for shockable out‐of‐hospital cardiac arrest recommended in the Guidelines 2000, CPR maneuver updates in CoSTR 2005 and 2010 were associated with improved neurologically intact survival year by year in Japan. Increased public awareness and greater dissemination of basic life support may be responsible for the observed improvement in outcomes.

Registration

URL: https://www.umin.ac.jp/ctr/; Unique identifier: 000009918.

Keywords: cardiopulmonary resuscitation, epidemiology, out‐of‐hospital cardiac arrest, resuscitation, shockable rhythm

Subject Categories: Cardiopulmonary Arrest, Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiac Care

Nonstandard Abbreviations and Acronyms

- BLS

basic life support

- CoSTR

consensus on CPR and emergency cardiovascular care science with treatment recommendations

- FDMA

fire and disaster management agency

- OHCA

out‐of‐hospital cardiac arrest

- ROSC

return of spontaneous circulation

Clinical Perspective.

What Is New?

Compared with cardiopulmonary resuscitation maneuvers for shockable out‐of‐hospital cardiac arrest recommended in the Guidelines 2000, cardiopulmonary resuscitation maneuver updates in CoSTR 2005 and 2010 were associated with improved neurologically intact survival year by year in Japan.

The dissemination of basic life support based on the latest guidelines to the general public might increase the practice of bystander cardiopulmonary resuscitation and improve neurological outcomes.

What Are the Clinical Implications?

The study's findings suggested the importance of high‐quality early chest compression skills and early 1‐shock defibrillation protocols in improving favorable neurological survival at 30 days after witnessed cardiac arrest from a shockable rhythm.

Out‐of‐hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA) necessitating cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) is a major public health problem, affecting ≈383 000 individuals in the United States, 1 275 000 individuals in Europe, 2 and 110 000 individuals in Japan 3 annually. Since 1992, CPR guidelines have emphasized early access to emergency medical service (EMS), early basic life support (BLS), early defibrillation, and early advanced life support as essential components of a series of actions, known as the “chain of survival,” designed to increase the return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC) and reduce the rates of morbidity and mortality associated with OHCA. 4 Despite decades of efforts to promote the chain of survival, survival after OHCA remains low worldwide. 5 In 2000, the International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation announced the International Guidelines 2000 for CPR and emergency cardiovascular care (Guidelines 2000) based on the best available evidence from resuscitation science. 5 Since 2000, the International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation has modified the guidelines to the international consensus on CPR and emergency cardiovascular care Science with Treatment Recommendations (CoSTR). The CoSTR 2005, 6 2010, 7 2015, 8 and 2020 9 were published.

In Japan, the Utstein Registry 10 for OHCA started in Osaka prefecture on 1998 11 and in the Kanto region on 2002. 12 Finally, the All‐Japan Utstein Registry was established by the fire and disaster management agency (FDMA) on January 1, 2005. 13 , 14 All Japanese EMS responders have modified the CPR 3 technique based on the Guidelines 2000 5 and each CoSTR update, 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 which indicate that they must start CPR efforts immediately unless the victim is obviously moribund. Per Japanese protocol, they cannot decide to terminate resuscitation efforts in the prehospital setting and must continue CPR efforts until the achievement of ROSC or hospital arrival. 3 , 11 , 12 , 13 The main updates for shockable OHCA, including ventricular fibrillation and pulseless ventricular tachycardia, included changes in BLS maneuvers, simplified EMS‐dispatcher CPR instruction, and a streamlined defibrillation protocol (Figure S1). 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 For example, the chest compression‐ventilation ratio changed from 15:2 in the Guidelines 2000 to 30:2 in the CoSTR 2005, and the defibrillation protocol changed from a 3‐shock sequence in the Guidelines 2000 to 1‐shock and 2‐minute CPR in the CoSTR 2005. The procedure for the BLS maneuvers changed from Airway–Breathing–Circulation in the CoSTR 2005 to Circulation–Airway–Breathing in the CoSTR 2010 and emphasized the quality of chest compressions in the CoSTR 2010. Furthermore, FDMA, the Japanese Red Cross Society, and other organizations were actively engaged in various BLS promotion efforts for the public in Japan. 15 , 16 , 17

Although the survival rate of patients who had OHCA has been gradually increasing, 18 , 19 , 20 few nationwide population‐based studies have investigated the comprehensive efficacy of these updated CPR maneuver guidelines. Thus, the primary objective of the present study was to determine whether CPR based on CoSTR 2005 or 2010 was associated with improved outcomes, as compared with CPR based on Guidelines 2000 in Japan.

Methods

The data, analytic methods, and study materials will not be made available to other researchers to reproduce the results or replicate the procedure.

Data Collection and Definitions

The All‐Japan Utstein Registry, a prospective, nationwide, population‐based registry of OHCA established in accordance with the ethical guidelines in Japan, 21 has been described in detail previously. 3 , 14 , 22 All fire stations with dispatch centers and all collaborating medical institutions have participated in the registry. All EMS providers and physicians have been performing and teaching CPR according to the Japanese CPR guidelines, which have been updated every 5 years based on international CPR recommendations. 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 There is standardization across all EMS systems in spite of regions in Japan.

A subcommittee of resuscitation science in the Japanese Circulation Society conducted this study with approval from the ethics committee at Nihon University Hospital on February 10, 2011 (the Institutional Review Board number is 110202). The design of this clinical trial was a prospective, observational study registered on a public website of the trial registry named “UMIN‐CTR” at the URL https://upload.umin.ac.jp/ (the UMIN‐CTR number is UMIN000009918). 3 , 22 The requirement of written informed consent from recruited patients was waived. A subcommittee of resuscitation science in the Japanese Circulation Society was provided with the trial registry data after the prescribed governmental legal procedures were followed. We analyzed deidentified and anonymized data only. 19

The EMS system in Japan has been described in previous papers. 3 , 13 , 21 , 22 Briefly, Japan had a population of 126 million in 2021, and 34.7% of the total Japanese population lived in the Kanto region (Figure S2). 23 Nationally, in 2021, there were 724 municipally governed fire stations with dispatch centers operating around the clock. Regardless of rurality or population density, there is standardization of CPR protocols across all EMS systems in Japan. 3 , 13 , 22 Each ambulance had 3 EMS responders, including at least 1 emergency life‐saving technician certified to insert intravenous lines and adjunct airways, but did not include any physicians. Specially trained emergency life‐saving technicians have been permitted to insert endotracheal tubes since July 2004 and administer epinephrine intravenously since April 2006. EMS responders were not permitted to terminate resuscitation in the emergency field. Thus, most patients with OHCA who were treated by EMS responders were transported to a hospital and registered in this registry except those with decapitation, incineration, decomposition, rigor mortis, or dependent cyanosis. 21

Data elements were collected prospectively based on the Utstein guidelines. 10 All event times were synchronized with the dispatch center clock. EMS responders documented whether the patient who had OHCA was witnessed by bystanders or EMS responders, the presence, or absence of EMS‐dispatcher telephone CPR instruction, the presence, or absence of bystander CPR, and bystander CPR techniques (chest compressions with or without rescue breathing, unidentified technique, and so on). The initial cardiac arrest rhythm was classified as a shockable or a nonshockable rhythm, including pulseless electrical activity, asystole, and uncertain rhythm, based on an automated external defibrillator analysis. Patients receiving citizen‐delivered shocks using public‐access defibrillators were classified as having a shockable rhythm. Prehospital ROSC was defined as any palpable spontaneous pulse achieved before hospital arrival under cardiac rhythm monitoring. The cause of arrest was determined clinically by the physicians in charge after hospital arrival. Resuscitation outcomes were collected by the receiving hospital physicians in collaboration with EMS responders. For patients discharged alive, the 30‐day neurological outcome was determined in a follow‐up interview. The data form was filled out by the EMS personnel in cooperation with the physicians in charge, and data were integrated into the registry system on the FDMA database server, then logically checked by the computer system.

Study Patients

From the All‐Japan Utstein Registry between January 1, 2005 and December 31, 2015, we included adult patients with OHCA witnessed by bystanders or EMS responders and whose initial cardiac arrest was a shockable heart rhythm. Patients were divided into the following 3 eras according to the onset year: Guidelines 2000 era, patients with onset occurring from January 1, 2005 to December 31, 2005; CoSTR 2005 era, patients with onset occurring from January 1, 2006 to December 31, 2010; and CoSTR 2010 era, patients with onset occurring from January 1, 2011 to December 31, 2015. The exclusion criteria included patients aged <18 years or with an unidentified age, had nonshockable OHCA, or unidentified arrest rhythm, had unwitnessed OHCA, or unidentified witnessed status, had unidentified bystander CPR, or had no resuscitation attempted.

The study patients were divided into the following 2 groups according to the witnessed status: bystander‐ and EMS‐responder‐witnessed groups (patients with OHCA after the arrival of an EMS responder). We compared each onset year from 2005 to 2015. As subgroup analyses, in the bystander‐witnessed group, we examined the outcomes of patients who received bystander chest‐compression‐only CPR, dispatcher CPR instruction, advanced airway management, or epinephrine administration. In the EMS‐responder‐witnessed group, we examined the outcomes of patients who received defibrillation <2 minutes or 2 to 4 minutes of intervals from collapse to the first defibrillation, or by biphasic waveform defibrillator. Arrests were further classified as occurring from cardiac causes, including acute coronary syndrome, heart failure, arrhythmia, and myocarditis, and noncardiac causes.

Role of the Funding Source

There was no funding source for this study. The implementation working group for the All‐Japan Utstein Registry of the FDMA designed the study protocol, and the FDMA collected and managed the data. The FDMA had no role in the analysis or interpretation of the data, nor in writing this report. All authors had full access to all data from the All‐Japan Utstein Registry, which is a publicly accessible open database. The corresponding author had the ultimate responsibility for the decision to submit the study for publication. We prepared the manuscript according to the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology guidelines.

End Points

The primary end point was a favorable neurological outcome at 30 days after OHCA, defined as a Cerebral Performance Category 1 (good performance) or 2 (moderate disability) on a 5‐category scale. 10 Unfavorable neurological outcomes were defined as Cerebral Performance Category 3 (severe disability), 4 (vegetative state), or 5 (death). The secondary outcomes included prehospital ROSC and survival (Cerebral Performance Category 1–4) at 30 days after OHCA.

Statistical Analysis

The patients' baseline characteristics and crude study outcomes were compared by using the χ2 test and Kruskal–Wallis rank test for categorical and continuous variables, respectively. We excluded cases with missing data. Multivariable logistic regression analyses were done for independent predictors of resuscitation, including enrollment year as a primary exposure variable. The potential confounding factors were chosen based on biological plausibility and previous studies and were included in the multivariable logistic regression analysis. 3 , 13 , 21 , 22 The other covariates were age, sex, collapse‐to‐first‐defibrillation interval (minutes), dispatcher CPR instruction (presence or absence), bystander CPR status (chest compression‐only CPR, conventional CPR, or no CPR), defibrillation by public‐access defibrillator (presence or absence), waveform of a defibrillator of an EMS responder (biphasic or monophasic waveform), airway management by an EMS responder (basic airway management alone or advanced airway management after basic airway management), intravenous administration of epinephrine by an EMS responder (presence or absence), cause of cardiac arrest (cardiac or noncardiac cause), and 8 districts of Japan where the arrest occurred (Figure S2), as appropriate. Additionally, these multivariate analyses were also performed for the subgroups of patients stratified by the above‐mentioned main CPR maneuvers updates of each witnessed group. Odds ratios, 95% CIs, and P values were calculated in the multivariable analysis. All hypothesis tests were 2‐sided, with a significance level set at <0.05. All analyses were performed using the SPSS software package (version 25.0 J, SPSS, IBM, Chicago, IL).

Results

Patient Population and Baseline Characteristics

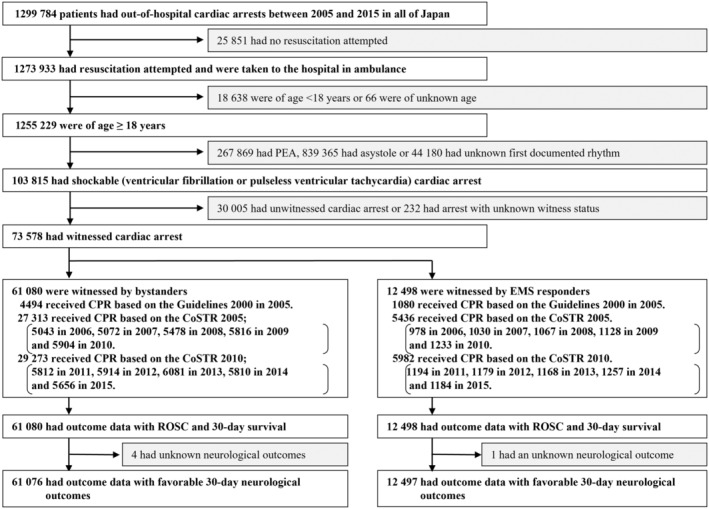

Between January 1, 2005 and December 31, 2015, 1 273 933 patients with OHCA received CPR by EMS responders and were subsequently transported to the hospital (Figure 1). Of these, 1 200 355 (94.2%) met the exclusion criteria, mostly based on an initial nonshockable OHCA. This study included 73 578 adult patients with witnessed shockable OHCA, comprising 61 080 (83.0%) patients witnessed by bystanders and 12 498 (17.0%) by EMS responders. This study had occasional missing data about age, initial heart rhythm, witness status, and 30‐day neurological outcomes, and some subjects who were excluded had >1 missing data point. Only 4 patients in the bystander‐witnessed group and 1 patient in the EMS‐witnessed group were missing 30‐day neurological outcomes. In the bystander‐witnessed group (Table 1), the baseline characteristics differed year by year; the rate of EMS‐dispatcher CPR instruction, dispatcher‐assisted CPR, bystander chest‐compression‐only CPR, public‐access defibrillator, and intravenous epinephrine increased year by year, and the rate of bystander airway management decreased year by year. In the EMS responder‐witnessed group (Table 2), similar results were seen.

Figure 1. Study profile.

CoSTR indicates international consensus on cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency cardiovascular care science with treatment recommendations; CPR, cardiopulmonary resuscitation; EMS, emergency medical service; PEA, pulseless electrical activity; and ROSC, return of spontaneous circulation.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of the Patients With Bystander‐Witnessed Shockable Cardiac Arrest (n=61 080)*

| P value for trend | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | |

| n= | 4494 | 5043 | 5072 | 5478 | 5816 | 5904 | 5812 | 5914 | 6081 | 5810 | 5656 | |

| Age (y) | 66 (55–76) | 67 (55–76) | 66 (55–76) | 67 (57–77) | 67 (56–77) | 67 (59–78) | 67 (57–78) | 68 (57–78) | 69 (57–80) | 68 (57–78) | 68 (56–78) | <0.001 |

| Male sex | 3545 (78.9) | 3933 (78.0) | 3961 (77.8) | 4265 (77.9) | 4537 (78.0) | 4580 (77.6) | 4469 (76.9) | 4558 (77.5) | 4600 (75.6) | 4571 (78.7) | 4374 (77.3) | 0.006 |

| Cardiac cause | 3882 (86.4) | 4411 (87.5) | 4394 (86.8) | 4824 (88.1) | 5132 (88.2) | 5114 (88.0) | 5154 (87.1) | 5154 (87.1) | 5314 (87.4) | 5210 (89.7) | 5084 (89.9) | <0.001 |

| Witness | <0.001 | |||||||||||

| Family | 2717 (60.5) | 2953 (58.6) | 2900 (57.2) | 3110 (56.8) | 3279 (56.4) | 3221 (54.6) | 3188 (54.9) | 3111 (52.6) | 3298 (54.2) | 3087 (53.1) | 3065 (54.2) | |

| Acquaintance | 718 (16.0) | 863 (17.1) | 894 (17.6) | 921 (16.8) | 929 (16.0) | 1041 (17.6) | 953 (16.9) | 973 (16.5) | 1014 (16.5) | 1014 (17.5) | 992 (17.5) | |

| Passerby | 1059 (23.6) | 1227 (24.3) | 1278 (25.2) | 1447 (26.4) | 1608 (16.0) | 1642 (27.8) | 1671 (28.8) | 1830 (30.9) | 1782 (29.3) | 1709 (29.4) | 1599 (28.3) | |

| EMS dispatcher CPR instruction | 1415 (31.5) | 1826 (36.2) | 2048 (40.4) | 2285 (41.7) | 2532 (43.5) | 2550 (43.2) | 2744 (47.2) | 2857 (48.3) | 3062 (50.4) | 3016 (51.9) | 3096 (55.1) | <0.001 |

| Dispatcher‐assisted CPR† , ‡ | 930 (65.7) | 1256 (68.8) | 1480 (72.3) | 1711 (74.9) | 1962 (77.5) | 1936 (76.0) | 2064 (75.2) | 2196 (76.9) | 2392 (78.1) | 2347 (77.8) | 2517 (81.0) | <0.001 |

| Bystander CPR | <0.001 | |||||||||||

| Chest compression only | 878 (19.5) | 1177 (23.3) | 1553 (30.6) | 1877 (34.3) | 2228 (38.3) | 2390 (40.5) | 2389 (41.1) | 2657 (44.9) | 3028 (49.8) | 2906 (50.0) | 2975 (52.6) | |

| Conventional CPR | 1062 (23.6) | 1228 (24.4) | 1114 (20.0) | 1034 (18.9) | 1040 (17.9) | 942 (16.0) | 901 (15.5) | 831 (14.1) | 610 (10.0) | 655 (11.3) | 618 (10.9) | |

| Unidentified CPR | 108 (2.4) | 83 (1.6) | 56 (1.1) | 44 (0.9 | 28 (0.5) | 31 (0.5) | 35 (0.6) | 29 (0.5) | 24 (0.4) | 19 (0.3) | 14 (0.2) | |

| No CPR | 2446 (54.4) | 1227 (24.3) | 2349 (46.3) | 2523 (46.1) | 2520 (44.3) | 2541 (43.0) | 2487 (42.8) | 2397 (40.5) | 2419 (39.8) | 2230 (29.4) | 2049 (36.2) | |

| Public access defibrillator | 59 (1.3) | 149 (3.0) | 255 (5.0) | 389 (7.1) | 547 (9.4) | 659 (11.2) | 712 (12.3) | 845 (14.3) | 758 (12.5) | 858 (14.8) | 866 (15.3) | <0.001 |

| Biphasic waveform defibrillators | 1904 (42.4) | 2896 (57.4) | 3560 (70.2) | 4146 (75.7) | 4693 (80.7) | 5037 (85.3) | 5013 (86.3) | 5140 (86.9) | 5236 (86.1) | 5026 (86.5) | 4855 (85.8) | <0.001 |

| Prehospital advance life support | ||||||||||||

| Advanced airway management | 2346 (52.2) | 2595 (51.5) | 2433 (48.0) | 2452 (44.8) | 2480 (42.6) | 2456 (41.6) | 2412 (41.5) | 2457 (41.5) | 2424 (39.9) | 2267 (39.0) | 2113 (37.4) | <0.001 |

| Intravenous epinephrine | 13 (0.3) | 198 (3.9) | 501 (9.9) | 780 (14.2) | 1072 (18.4) | 1321 (22.2) | 1513 (26.0) | 1614 (27.3) | 1631 (26.8) | 1774 (30.5) | 1722 (30.4) | <0.001 |

| District | <0.001 | |||||||||||

| Hokkaido | 211 (4.7) | 266 (5.3) | 229 (4.5) | 220 (4.0) | 258 (4.4) | 245 (3.1) | 259 (4.5) | 265 (4.5) | 244 (4.0) | 250 (4.3) | 292 (5.2) | |

| Tohoku | 421 (9.6) | 442 (8.8) | 450 (8.9) | 491 (9.0) | 506 (8.7) | 476 (8.1) | 498 (8.6) | 518 (8.8) | 508 (8.4) | 488 (8.4) | 475 (8.4) | |

| Kanto | 1395 (31.0) | 1528 (30.3) | 1649 (32.5) | 1670 (30.5) | 1881 (32.3) | 1956 (33.1) | 1944 (33.4) | 2003 (33.9) | 2451 (40.3) | 2051 (35.3) | 1907 (33.7) | |

| Chubu | 818 (18.2) | 910 (18.0) | 851 (16.8) | 1016 (18.5) | 1068 (18.4) | 1096 (18.6) | 1053 (18.1) | 1061 (17.9) | 1053 (17.0) | 1054 (18.1) | 931 (16.5) | |

| Kinki | 806 (17.9) | 930 (18.4) | 888 (17.5) | 961 (17.5) | 964 (16.6) | 994 (16.8) | 942 (16.2) | 1043 (17.7) | 839 (13.8) | 946 (16.3) | 997 (17.6) | |

| Chugoku | 273 (6.1) | 305 (6.0) | 249 (4.9) | 349 (6.4) | 350 (6.0) | 348 (5.9) | 321 (5.5) | 270 (4.6) | 312 (5.1) | 288 (5.0) | 284 (5.0) | |

| Shikoku | 132 (2.9) | 161 (3.2) | 147 (2.9) | 161 (2.9) | 172 (3.0) | 147 (2.5) | 155 (2.7) | 146 (2.5) | 170 (2.8) | 146 (2.5) | 146 (2.6) | |

| Kyushu | 428 (9.5) | 501 (9.9) | 609 (12.0) | 610 (11.0) | 617 (10.6) | 642 (10.9) | 640 (11.0) | 603 (10.2) | 522 (8.6) | 587 (10.1) | 624 (11.0) | |

| Time interval from (min)§ | ||||||||||||

| Collapse to call receipt | 2 (0–4) | 2 (0–4) | 2 (0–4) | 2 (0–4) | 2 (0–4) | 2 (0–3) | 2 (0–4) | 2 (0–4) | 2 (0–4) | 2 (0–4) | 2 (0–4) | <0.001 |

| Call receipt to scene | 6 (4–8) | 6 (5–8) | 6 (5–8) | 6 (5–8) | 7 (5–8) | 7 (5–9) | 7 (5–9) | 7 (5–9) | 7 (5–9) | 7 (5–9) | 7 (5–9) | <0.001 |

| Collapse to first defibrillation | 11 (8–15) | 11 (8–14) | 12 (9–15) | 12 (9–15) | 12 (9–15) | 12 (9–15) | 12 (9–15) | 12 (9–15) | 12 (9–16) | 12 (9–15) | 12 (9–15) | <0.001 |

| Scene to hospital arrival | 22 (17–28) | 22 (17–29) | 23 (18–29) | 23 (18–29) | 23 (18–30) | 24 (18–30) | 24 (18–31) | 24 (19–31) | 24 (19–31) | 24 (19–31) | 24 (19–31) | <0.001 |

Values are median (interquartile range) or numerator/total number (%). CPR indicates cardiopulmonary resuscitation; and EMS, emergency medical service.

CPR refers to chest compressions with or without rescue breathings.

No./total no. of EMS dispatcher CPR instruction.

Total number of patients calculating time intervals; 60 190 in the collapse‐to‐call‐receipt interval; 61 032 in the call‐receipt‐to‐scene interval, 54 298 in the collapse‐to‐first‐defibrillation interval, and 60 796 in the scene‐to‐hospital‐arrival interval.

Table 2.

Baseline Characteristics of the Patients With EMS‐Responder‐Witnessed Shockable Cardiac Arrest (Shockable Arrest After Arrival of EMS Responders) (n=12 498)*

| P value for trend | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | |

| n= | 1080 | 978 | 1030 | 1067 | 1128 | 1233 | 1194 | 1179 | 1168 | 1257 | 1184 | |

| Age (y) | 69 (58–79) | 69 (57–79) | 69 (56–78) | 68 (58–80) | 69 (58–80) | 69 (58–79) | 69 (59–80) | 70 (60–81) | 70 (58–80) | 70 (59–80) | 70 (59–81) | 0.118 |

| Male sex | 767 (71.0) | 717 (73.3) | 740 (71.8) | 737 (69.1) | 816 (72.3) | 886 (71.9) | 843 (70.6) | 836 (70.9) | 807 (69.1) | 876 (69.7) | 860 (72.6) | 0.360 |

| Cardiac cause | 808 (74.8) | 755 (77.2) | 793 (77.0) | 848 (79.5) | 920 (81.6) | 922 (80.5) | 952 (79.7) | 944 (80.1) | 936 (80.1) | 1031 (82.0) | 989 (83.5) | <0.001 |

| Biphasic waveform defibrillators | 411 (38.1) | 537 (54.9) | 680 (66.0) | 802 (75.2) | 911 (80.8) | 1060 (86.0) | 1064 (89.1) | 1061 (90.0) | 1030 (88.2) | 1117 (88.9) | 1068 (90.2) | <0.001 |

| Prehospital advance life support | ||||||||||||

| Advanced airway management | 243 (22.5) | 228 (23.3) | 238 (23.1) | 199 (18.7) | 223 (19.8) | 228 (18.5) | 228 (19.1) | 214 (18.2) | 238 (20.4) | 205 (16.3) | 180 (15.2) | <0.001 |

| Intravenous epinephrine | 1 (0.1 | 4 (0.4) | 37 (3.6) | 45 (4.2) | 75 (6.6) | 93 (7.5) | 124 (10.4) | 131 (11.1) | 139 (11.9) | 150 (11.9) | 132 (11.1) | <0.001 |

| District | <0.001 | |||||||||||

| Hokkaido | 56 (5.2) | 37 (3.8) | 57 (5.5) | 62 (5.8) | 53 (4.7) | 51 (4.1) | 65 (5.4) | 69 (5.9) | 64 (5.5) | 73 (5.8) | 48 (4.1) | |

| Tohoku | 101 (9.4) | 78 (8.0) | 95 (9.2) | 87 (8.2) | 99 (8.8) | 102 (8.3) | 104 (8.7) | 74 (6.3) | 100 (8.6) | 111 (8.8) | 101 (8.5) | |

| Kanto | 367 (33.4) | 325 (33.2) | 365 (35.4) | 372 (34.9) | 359 (31.8) | 408 (33.1) | 366 (30.7) | 421 (35.7) | 426 (36.5) | 477 (37.9) | 415 (35.1) | |

| Chubu | 173 (16.0) | 146 (14.9) | 138 (13.4) | 140 (13.1) | 155 (13.7) | 215 (17.4) | 197 (16.5) | 220 (18.7) | 204 (17.5) | 200 (15.9) | 211 (17.8) | |

| Kinki | 172 (15.9) | 176 (18.0) | 201 (19.5) | 181 (17.0) | 228 (20.2) | 227 (18.4) | 214 (17.9) | 210 (17.8) | 160 (13.7) | 171 (13.6) | 178 (15.0) | |

| Chugoku | 72 (6.2) | 75 (7.7) | 47 (4.6) | 66 (6.2) | 79 (7.0) | 57 (4.6) | 69 (5.8) | 53 (4.5) | 66 (5.7) | 61 (4.9) | 69 (5.8) | |

| Shikoku | 28 (2.6) | 28 (2.9) | 35 (3.4) | 36 (3.4) | 36 (3.5) | 33 (2.7) | 36 (3.0) | 37 (3.1) | 35 (3.0) | 47 (3.7) | 35 (3.0) | |

| Kyushu | 117 (10.8) | 113 (11.6) | 113 (11.6) | 123 (11.5) | 116 (10.3) | 140 (11.4) | 143 (12.0) | 95 (8.1) | 113 (9.7) | 117 (9.3) | 127 (10.7) | |

| Time interval from (min)† | ||||||||||||

| Call receipt to scene | 6 (5–8) | 6 (4–8) | 6 (5–8) | 6 (5–8) | 7 (5–9) | 7 (5–9) | 7 (5–9) | 7 (5–9) | 7 (5–9) | 7 (6–9) | 7 (5–10) | <0.001 |

| Collapse to first defibrillation | 2 (1–4) | 1 (1–3) | 1 (1–3) | 1 (1–3) | 1 (1–3) | 1 (1–3) | 1 (1–3) | 1 (1–2) | 1 (1–3) | 1 (1–2) | 1 (1–2) | <0.001 |

| Scene to hospital arrival | 25 (18–34) | 26 (19–34) | 26 (19–36) | 26 (20–36) | 27 (20–36) | 27 (20–36) | 27 (20–36) | 28 (21–39) | 28 (20–37) | 29 (22–38) | 28 (21–37) | <0.001 |

Values are median (25th–75th percentile) or numerator/total number (%). EMS indicates emergency medical service.

Total number of patients calculating time intervals; 12 483 in the call‐receipt‐to‐scene interval, 11 149 in the collapse‐to‐first‐defibrillation interval, and 12 365 in the scene‐to‐hospital‐arrival interval.

Outcomes

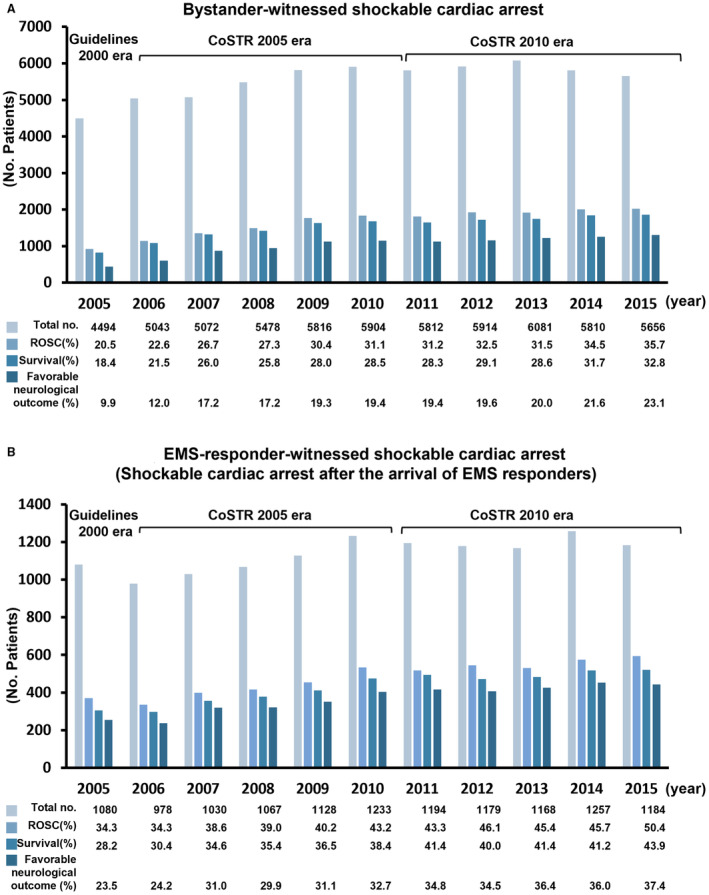

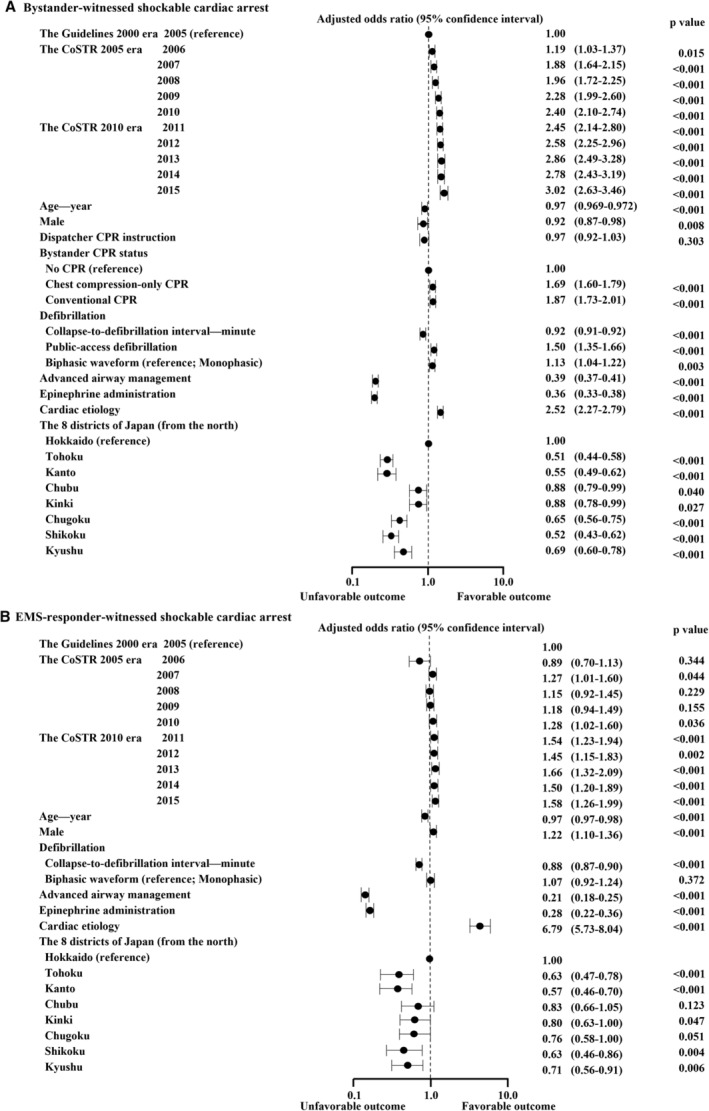

In both of the witnessed groups, each crude study outcome (prehospital ROSC, 30‐day survival, and favorable 30‐day neurological outcome) increased year by year (Figure 2). Figure 3 shows the results of the multivariable logistic regression analyses for independent predictors of resuscitation stratified by witnessed status. In the bystander‐witnessed group (Figures 3A), the adjusted odds ratios for favorable neurological outcomes in the patients by enrollment year increased year by year (1.19 in 2006 [95% CI, 1.03–1.37; P=0.015], and 3.01 in 2015 [95% CI, 2.63–3.46; P <0.001]), compared with the patients in 2005 of the Guidelines 2000 era. The other independent predictors were age, sex, bystander CPR status, public‐access defibrillator, collapse‐to‐first‐defibrillation interval, biphasic waveform defibrillator, advanced airway management, epinephrine administration, cardiac cause, and districts of Japan. In the EMS‐responder‐witnessed group (Figure 3B), the adjusted odds ratios for favorable 30‐day neurological outcomes in the patients by enrollment year increased year by year (0.89 in 2006 [95% CI, 0.70–1.13; P=0.344], and 1.58 in 2015 [95% CI, 1.26–1.99; P <0.001]), compared with the patients in 2005 of the Guidelines 2000 era. The other independent predictors were age, sex, collapse‐to‐first‐defibrillation interval, advanced airway management, epinephrine administration, cardiac cause, and districts of Japan.

Figure 2. Crude study outcomes in patients with out‐of‐hospital shockable cardiac arrest stratified by witnessed status.

A, Bystander, (B) EMS‐responder. In both witnessed groups, each crude study outcome (prehospital ROSC, 30‐day survival, and favorable 30‐day neurological outcome) increased year by year (P <0.001, respectively). CoSTR indicates international consensus on cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency cardiovascular care science with treatment recommendations; EMS, emergency medical service; and ROSC, return of spontaneous circulation.

Figure 3. Adjusted odds ratios for favorable 30‐day neurological outcome after out‐of‐hospital shockable cardiac arrest stratified by witnessed status.

A, Bystander, (B) EMS‐responder. Data for multivariable logistic regression analysis were available for 88.8% (54 244/61 080) of the bystander‐witnessed cardiac arrest cases and 89.2% (11 142/12 498) of the EMS‐responder‐witnessed cardiac arrest cases. CoSTR indicates international consensus on cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency cardiovascular care science with treatment recommendations; CPR, cardiopulmonary resuscitation; and EMS, emergency medical service.

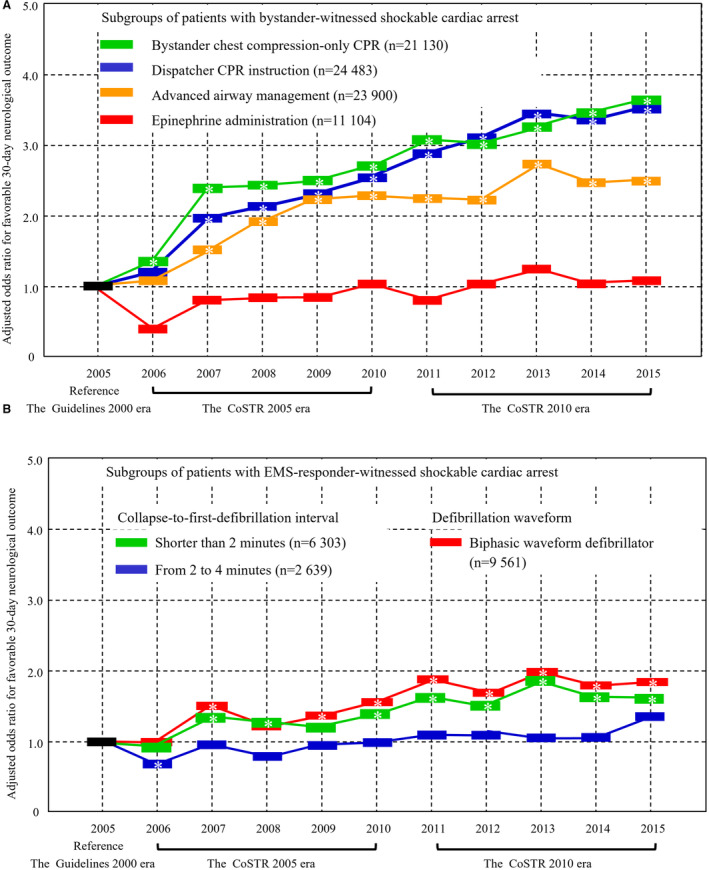

Outcomes in the Subgroups

Figure 4 shows the adjusted odds ratios for favorable 30‐day neurological outcomes in the subgroups of patients stratified by changes in CPR maneuvers. In the bystander‐witnessed subgroups of cases receiving chest‐compression‐only CPR, EMS‐dispatcher CPR instruction, or advanced airway management (Figure 4A), the adjusted odds ratios for favorable 30‐day neurological outcomes increased year by year (reference, 2005 of the Guidelines 2000 era), but cases receiving epinephrine had no neurological improvement. In the EMS‐responder‐witnessed subgroups of cases where defibrillation was delivered in <2 minutes of collapse or using biphasic waveform defibrillators (Figure 4B), the adjusted odds ratios for favorable 30‐day neurological outcomes increased year by year (reference, 2005 of the Guidelines 2000 era), but cases receiving the first defibrillation from 2 to 4 minutes after collapse showed no neurological improvement over time.

Figure 4. Adjusted odds ratios for favorable 30‐day neurological outcome in the subgroups of patients stratified by witnessed status.

A, Bystander, (B) EMS‐responder. Adjusted odds ratio (95% CI) was significantly different (reference, 2005). CoSTR indicates international consensus on cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency cardiovascular care science with treatment recommendations; CPR, cardiopulmonary resuscitation; and EMS, emergency medical service.

Discussion

This is the first nationwide study to compare the comprehensive effects of CPR maneuvers based on the Guidelines 2000, CoSTR 2005, and 2010 for patients with witnessed shockable OHCA over 11 years. Our data showed that systematic implementation of the international CPR maneuver guideline updates was associated with improved neurologically intact survival year by year (Figures 2 and 3). Data from cases in the final year (2010 or 2015) of each specified CoSTR era (when rescuers were considered to have acquired mastery of the era's CPR algorithm) demonstrated higher neurologically intact survival among each year cases in each CoSTR era (Figures 2 and 3). These findings suggested that optimal performance of the era's CPR skills contributed to the high neurologically intact survival rate, and time was required to disseminate and learn best practices.

Citizen CPR

In the multivariate analysis (Figure 3), degrees of improvements in neurologically intact survival were greater in the bystander‐witnessed group than in the EMS‐responder‐witnessed group. In the bystander‐witnessed group (Figure 3A), CPR maneuvers based on CoSTR 2005 and 2010 were associated with improvement of the neurologically intact survival year by year when compared with those maneuvers based on the Guidelines 2000. The implementation of bystander CPR also increased year by year (Table 1). Moreover, the subgroup receiving bystander chest‐compression‐only CPR had improved neurologically intact survival year by year (Figure 4A). This result might be associated with an increase in the number of students attending BLS training year by year for the study period. 15 Although in 2005, the number of students attending BLS training held by FDMA was 1 215 985 per year, in 2015, the number of these students was 1 849 445. 15 Therefore, the dissemination of BLS based on the latest guidelines to the general public might increase the practice of bystander CPR and improve neurologic outcomes. These findings suggested that compliance with each recommendation for the quality of early chest compressions improved cerebral perfusion during CPR.

Early Defibrillation

In contrast, in the EMS‐responder‐witnessed group (Figure 3B), CPR maneuvers based on the CoSTR 2005 were not associated with improvement in neurological outcomes. However, CPR maneuvers based on CoSTR 2010 were associated with improved neurologically intact survival (Figure 3B). That is, CPR maneuvers recommended in CoSTR 2010 may have provided superior cerebral perfusion when compared with those in CoSTR 2005. In addition, our results showed that the median interval from collapse to defibrillation was shorter in the EMS‐responder‐witnessed group than in the bystander‐witnessed group (1–2 minutes versus 11–12 minutes, Tables 1 and 2). In the EMS‐responder‐witnessed group, cases receiving first defibrillation shorter than 2 minutes after collapse had neurological improvement, while cases receiving first defibrillation from 2 to 4 minutes after collapse had no neurological improvement over the CoSTR 2005 and 2010 eras (Figure 4B). In other words, early defibrillation was paramount to improvements in neurologically intact survival.

Advanced Life Support

In the bystander‐witnessed subgroups of cases receiving advanced airway management (Figure 4A), the adjusted odds ratios for favorable 30‐day neurological outcomes increased year by year. During the study period, the number of emergency life‐saving technicians increased from 17 091 to 32 813, 24 and this increase might be associated with improved outcomes. In addition, this suggested that more advanced procedures might have contributed to the improvements. However, epinephrine administration after bystander‐witnessed arrest was not associated with improvements in neurologically intact survival over the 11‐year‐long study period (Figures 3A and 4A). A possible explanation for this finding is that shockable OHCA cases receiving prehospital epinephrine administration had more severe pathophysiology, which remained refractory to treatment despite CPR maneuver improvements. After the publication of CoSTR 2015, 8 which gave routine epinephrine administration a weak recommendation supported by very low‐quality evidence, Perkins et al reported that epinephrine, when compared with placebo, increased the 30‐day survival in patients with nonshockable OHCA but had unclear benefits in those with shockable OHCA. 25 These findings suggest that further epinephrine studies for patients with shockable OHCA are needed. In the future, a detailed investigation of epinephrine administration would be a relevant research topic for shockable and nonshockable patients with OHCA enrolled in the All‐Japan Utstein Registry.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, we did not perform a randomized controlled trial, so all conclusions are limited to associations and causality cannot be determined. Second, although we planned to add an analysis of the CoSTR 2015 era (2016 to 2020), due to constraints related to the COVID‐19 pandemic, the period of this nationwide study was ultimately set to 11 years (2005 to 2015). During an epidemic of infectious diseases, such as COVID‐19, resuscitation algorithms are significantly modified to protect CPR providers, and comparisons between 2020 data and previous years were not possible. Third, the quality of CPR affects the ROSC rates and neurological outcomes, but data on CPR quality were lacking. However, the changes in BLS maneuvers improved the neurological outcome, which suggests that those changes were associated with improvements in CPR quality. Although we excluded patients with nonshockable OHCA and/or who did not receive bystander CPR in this study, the results of such patients were similar to shockable patients with OHCA. Fourth, detailed information regarding ongoing CPR efforts after hospital arrival and detailed information on comorbidities were lacking. Although there was a vast array of cardiac causes, and they had dramatic differences in prognosis, 26 we could not access detailed information on specific cardiac causes in this registry. Fifth, the details on postcardiac arrest care, 9 , 27 , 28 including targeted temperature management and extracorporeal CPR, were lacking. Regardless, any improvements resulting from advanced life support therapies are less substantial than the increases in the neurologically intact survival rates reported from successful deployment of citizen CPR and automated external defibrillator programs in the community. Finally, neurological outcomes were measured at 30 days after OHCA, but some patients might recover more gradually. 29

Conclusions

In conclusion, compared with CPR maneuvers for shockable OHCA recommended in the Guidelines 2000, CPR maneuver updates in CoSTR 2005 and 2010 were associated with improved neurologically intact survival year by year in Japan, which might have been due to increased public awareness and greater dissemination of BLS being responsible for improved outcomes. Even if the CPR guidelines were updated, however, there was no evidence of any benefit from the addition of epinephrine administration or delayed defibrillation. These findings suggested the importance of high‐quality early chest compression skills and early 1‐shock defibrillation protocols. We consider that future studies on epinephrine are warranted.

Sources of Funding

None.

Disclosures

None.

Supporting information

Data S1

Figures S1–S2

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all the emergency medical services personnel and concerned physicians in Japan, the staff of the Fire and Disaster Management Agency, and the Institute for Fire Safety and Disaster Preparedness of Japan for their generous cooperation in establishing and following the Utstein database. We would like to thank the staff of the Japanese Circulation Society for the administrative work done for the subcommittee on resuscitation science in the Japanese Circulation Society. We would like to thank Enago (www.enago.jp) for the English review. KN, NY, DFG, and TY were involved in the study design, data analysis, and interpretation of the study results, and contributed to the writing of the final report. ET, NI, and SS were the principal investigators involved in study design, study completion, data collection, and data management, and these authors contributed to the formulation of the concept of the All‐Japan Utstein Registry. YT, HN, and TI were involved in formulating the concept of the study and were involved in the study design, study completion, data collection, data management, and interpretation of the study results. All authors approved the final version of the article.

This manuscript was sent to Kori S. Zachrison, MD, MSc, Associate Editor, for review by expert referees, editorial decision, and final disposition.

Supplemental Material is available at https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/suppl/10.1161/JAHA.123.031394

For Sources of Funding and Disclosures, see page 13.

Contributor Information

Tsukasa Yagi, Email: yagi.tsukasa@nihon-u.ac.jp.

Ken Nagao, Email: nagao.ken99@gmail.com.

References

- 1. Virani SS, Alonso A, Benjamin EJ, Bittencourt MS, Callaway CW, Carson AP, Chamberlain AM, Chang AR, Cheng S, Delling FN, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics‐2020 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2020;141:e139–e596. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000757 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Atwood C, Eisenberg MS, Herlitz J, Rea TD. Incidence of EMS‐treated out‐of‐hospital cardiac arrest in Europe. Resuscitation. 2005;67:75–80. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2005.03.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Nagao K, Nonogi H, Yonemoto N, Gaieski DF, Ito N, Takayama M, Shirai S, Furuya S, Tani S, Kimura T, et al. Duration of prehospital resuscitation efforts after out‐of‐hospital cardiac arrest. Circulation. 2016;133:1386–1396. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.018788 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Guidelines for cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency cardiac care . Emergency cardiac care committee and subcommittees, American Heart Association. Part I. Introduction. JAMA. 1992;268:2171–2183. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Part 1: introduction to the international guidelines 2000 for CPR and ECC: a consensus on science. Circulation. 2000;102:I1–I11. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.102.suppl_1.I-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. ECC Committee, Subcommittees and Task Forces of the American Heart Association . 2005 American Heart Association guidelines for cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency cardiovascular care. Circulation. 2005;112:3958–3968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Field JM, Hazinski MF, Sayre MR, Chameides L, Schexnayder SM, Hemphill R, Samson RA, Kattwinkel J, Berg RA, Bhanji F, et al. Part 1: executive summary: 2010 American Heart Association guidelines for cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency cardiovascular care. Circulation. 2010;122:S640–S656. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.970889 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Neumar RW, Shuster M, Callaway CW, Gent LM, Atkins DL, Bhanji F, Brooks SC, de Caen AR, Donnino MW, Ferrer JM, et al. Part 1: executive summary: 2015 American Heart Association guidelines update for cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency cardiovascular care. Circulation. 2015;132:S315–S367. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Merchant RM, Topjian AA, Panchal AR, Cheng A, Aziz K, Berg KM, Lavonas EJ, Magid DJ. Part 1: executive summary: 2020 American Heart Association guidelines for cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency cardiovascular care. Circulation. 2020;142:S337–S357. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000918 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cummins RO, Chamberlain DA, Abramson NS, Allen M, Baskett PJ, Becker L, Bossaert L, Delooz HH, Dick WF, Eisenberg MS, et al. Recommended guidelines for uniform reporting of data from out‐of‐hospital cardiac arrest: the Utstein style. A statement for health professionals from a task force of the American Heart Association, the European Resuscitation Council, the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada, and the Australian Resuscitation Council. Circulation. 1991;84:960–975. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.84.2.960 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Iwami T, Kawamura T, Hiraide A, Berg RA, Hayashi Y, Nishiuchi T, Kajino K, Yonemoto N, Yukioka H, Sugimoto H, et al. Effectiveness of bystander‐initiated cardiac‐only resuscitation for patients with out‐of‐hospital cardiac arrest. Circulation. 2007;116:2900–2907. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.723411 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. SOS‐Kanto Study Group . Cardiopulmonary resuscitation by bystanders with chest compression only (SOS‐KANTO): an observational study. Lancet (London, England). 2007;369:920–926. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60451-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kitamura T, Iwami T, Kawamura T, Nagao K, Tanaka H, Hiraide A. Nationwide public‐access defibrillation in Japan. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:994–1004. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0906644 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kitamura T, Iwami T, Kawamura T, Nagao K, Tanaka H, Nadkarni VM, Berg RA, Hiraide A. Conventional and chest‐compression‐only cardiopulmonary resuscitation by bystanders for children who have out‐of‐hospital cardiac arrests: a prospective, nationwide, population‐based cohort study. Lancet. 2010;375:1347–1354. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60064-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Fire and Disaster Management Agency of the Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications . Fire white paper. (In Japanese). Accessed June 5, 2023. https://www.fdma.go.jp/publication/hakusho/h29/topics8/46137.html.

- 16. Mitamura H, Iwami T, Mitani Y, Takeda S, Takatsuki S. Aiming for zero deaths: prevention of sudden cardiac death in schools–statement from the AED Committee of the Japanese Circulation Society. Circ J. 2015;79:1398–1401. doi: 10.1253/circj.CJ-15-0453 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Nishiyama C, Kiyohara K, Matsuyama T, Kitamura T, Kiguchi T, Kobayashi D, Okabayashi S, Shimamoto T, Kawamura T, Iwami T. Characteristics and outcomes of out‐of‐hospital cardiac arrest in educational institutions in Japan‐ all‐Japan Utstein registry. Circ J. 2020;84:577–583. doi: 10.1253/circj.CJ-19-0920 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kitamura T, Iwami T, Kawamura T, Nitta M, Nagao K, Nonogi H, Yonemoto N, Kimura T. Nationwide improvements in survival from out‐of‐hospital cardiac arrest in Japan. Circulation. 2012;126:2834–2843. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.109496 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Wissenberg M, Lippert FK, Folke F, Weeke P, Hansen CM, Christensen EF, Jans H, Hansen PA, Lang‐Jensen T, Olesen JB, et al. Association of national initiatives to improve cardiac arrest management with rates of bystander intervention and patient survival after out‐of‐hospital cardiac arrest. JAMA. 2013;310:1377–1384. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.278483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Chan PS, McNally B, Tang F, Kellermann A. Recent trends in survival from out‐of‐hospital cardiac arrest in the United States. Circulation. 2014;130:1876–1882. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.009711 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Iwami T, Kitamura T, Kawamura T, Mitamura H, Nagao K, Takayama M, Seino Y, Tanaka H, Nonogi H, Yonemoto N, et al. Chest compression‐only cardiopulmonary resuscitation for out‐of‐hospital cardiac arrest with public‐access defibrillation: a nationwide cohort study. Circulation. 2012;126:2844–2851. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.109504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Nakashima T, Noguchi T, Tahara Y, Nishimura K, Yasuda S, Onozuka D, Iwami T, Yonemoto N, Nagao K, Nonogi H, et al. Public‐access defibrillation and neurological outcomes in patients with out‐of‐hospital cardiac arrest in Japan: a population‐based cohort study. Lancet. 2019;394:2255–2262. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32488-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Statistics Bureau . Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications. Current Population Estimates as of October 1. 2021. Accessed September 25, 2023. https://www.stat.go.jp/english/data/jinsui/2021np/index.html.

- 24. Fire and Disaster Management Agency of the Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications . Fire white paper. (In Japanese). Accessed Norvember 8, 2023, https://www.fdma.go.jp/publication/hakusho/r1/chapter2/section5/47780.html.

- 25. Perkins GD, Ji C, Deakin CD, Quinn T, Nolan JP, Scomparin C, Regan S, Long J, Slowther A, Pocock H, et al. A randomized trial of epinephrine in out‐of‐hospital cardiac arrest. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:711–721. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1806842 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hayashi M, Shimizu W, Albert CM. The spectrum of epidemiology underlying sudden cardiac death. Circ Res. 2015;116:1887–1906. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.304521 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Gaieski DF, Band RA, Abella BS, Neumar RW, Fuchs BD, Kolansky DM, Merchant RM, Carr BG, Becker LB, Maguire C, et al. Early goal‐directed hemodynamic optimization combined with therapeutic hypothermia in comatose survivors of out‐of‐hospital cardiac arrest. Resuscitation. 2009;80:418–424. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2008.12.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hassager C, Nagao K, Hildick‐Smith D. Out‐of‐hospital cardiac arrest: in‐hospital intervention strategies. Lancet. 2018;391:989–998. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30315-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Becker LB, Aufderheide TP, Geocadin RG, Callaway CW, Lazar RM, Donnino MW, Nadkarni VM, Abella BS, Adrie C, Berg RA, et al. Primary outcomes for resuscitation science studies: a consensus statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2011;124:2158–2177. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e3182340239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data S1

Figures S1–S2