Abstract

Background

The renal sympathetic nervous system modulates systemic blood pressure, cardiac performance, and renal function. Pathological increases in renal sympathetic nerve activity contribute to the pathogenesis of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF).

We investigated the effects of renal sympathetic denervation performed at early or late stages of HFpEF progression.

Methods and Results

Male ZSF1 obese rats were subjected to radiofrequency renal denervation (RF‐RDN) or sham procedure at either 8 weeks or 20 weeks of age and assessed for cardiovascular function, exercise capacity, and cardiorenal fibrosis. Renal norepinephrine and renal nerve tyrosine hydroxylase staining were performed to quantify denervation following RF‐RDN. In addition, renal injury, oxidative stress, inflammation, and profibrotic biomarkers were evaluated to determine pathways associated with RDN. RF‐RDN significantly reduced renal norepinephrine and tyrosine hydroxylase content in both study cohorts. RF‐RDN therapy performed at 8 weeks of age attenuated cardiac dysfunction, reduced cardiorenal fibrosis, and improved endothelial‐dependent vascular reactivity. These improvements were associated with reductions in renal injury markers, expression of renal NLR family pyrin domain containing 3/interleukin 1β, and expression of profibrotic mediators. RF‐RDN failed to exert beneficial effects when administered in the 20‐week‐old HFpEF cohort.

Conclusions

Our data demonstrate that early RF‐RDN therapy protects against HFpEF disease progression in part due to the attenuation of renal fibrosis and inflammation. In contrast, the renoprotective and left ventricular functional improvements were lost when RF‐RDN was performed in later HFpEF progression. These results suggest that RDN may be a viable treatment option for HFpEF during the early stages of this systemic inflammatory disease.

Keywords: heart failure, HFpEF, NLRP3 inflammasome, renal denervation, sympathetic nervous system

Subject Categories: Heart Failure, Metabolic Syndrome, Inflammatory Heart Disease

NonstandardAbbreviations and Acronyms

- HFpEF

heart failure with preserved ejection fraction

- HFrEF

heart failure with reserved ejection fraction

- KCCQ

Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire

- KIM‐1

kidney injury marker 1

- NLRP3

NLR family pyrin domain containing 3

- RDN

renal denervation

- RF‐RDN

radiofrequency renal denervation

- SGLT2

sodium/glucose cotransporter 2

- SNS

sympathetic nervous system

- TH

tyrosine hydroxylase

- ZSF1

Zucker Spontaneously Fatty 1

Clinical Perspective.

What Is New?

Radiofrequency renal denervation exerts cardioprotective and renoprotective actions in a rodent model of cardiometabolic heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) when applied at an early stage in HFpEF pathophysiological progression.

Ablation of renal sympathetic nerve activity improved cardiac diastolic function, vascular function, and perivascular cardiac fibrosis without significant reductions in systemic blood pressures in the Zucker Spontaneously Fatty 1 obese rat HFpEF model.

Renal denervation similarly reduced renal injury markers, fibrosis, and renal inflammatory mediators in part by reducing synthesis of renal NLR family pyrin domain containing 3 inflammasome–mediated interleukin 1β.

What Are the Clinical Implications?

Pathologic sympathetic overactivation has been postulated as a fundamental driver of HFpEF disease progression, and our results suggest that downregulation of renal‐mediated sympathetic outflow through renal denervation could be an effective treatment strategy for patients with HFpEF.

Renal denervation was recently approved by Food and Drug Administration for resistant hypertension, and this therapeutic approach to attenuate renal sympathetic nerve pathological activity might be suitable for additional cardiovascular disease states including heart failure.

Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) is a growing health care concern due to its increasing incidence, high morbidity and mortality, and lack of effective treatment options. 1 , 2 , 3 Unlike HF with reduced EF (HFrEF), advances in HFpEF therapy have been challenging given HFpEF's complex pathogenesis. 4 The presence of multiple comorbidities (ie, hypertension, diabetes, central obesity) that pathologically activate the sympathetic nervous system (SNS) combined with previous reports of increased norepinephrine levels in patients with HFpEF suggest that SNS overactivation contributes to HFpEF pathology. 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 Given this, pharmacotherapies targeting the SNS (β‐blockers, angiotensin receptor blockers, angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitors, mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists, angiotensin receptor neprilysin inhibitor) have been investigated in HFpEF and proven to be largely ineffective. 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 While underwhelming, these clinical observations may be a result of transient or incomplete blockade of the SNS and downstream SNS‐derived mediators, which is insufficient to treat the complex pathology associated with HFpEF. The demonstrated evidence for robust SNS upregulation in patients with HFpEF combined with the well‐established deleterious effects of SNS overactivation warrants further investigation of potent SNS‐targeted therapeutic approaches in HFpEF. 15

Renal denervation (RDN) is a sympathomodulatory, catheter‐based therapeutic approach that downregulates the cardiorenal sympathetic axis through ablation of efferent and afferent renal nerves. RDN clinical trials highlight the effects of RDN on blood pressure (BP) reduction in resistant hypertension with the presence or absence of antihypertensive medications. 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 However, SNS overactivation influences a number of cardiac and vascular responses beyond BP regulation including pathologic cardiac hypertrophy and fibrosis, renal impairment, metabolic dysregulation and arrhythmogenicity, all of which are frequently comorbid with HFpEF. 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 To this point, additional benefits of RDN treatment have been elucidated from previous investigations in patients, including attenuation of left ventricular (LV) hypertrophy, diastolic dysfunction, estimated glomerular filtration rate decline, and atrial fibrillation burden. 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 Further supporting the notion that RDN could be beneficial in HFpEF, a retrospective analysis revealed that patients with HFpEF who received RDN exhibited reduced pathological severity compared with patients with untreated HFpEF. 30

We have previously reported that radiofrequency RDN (RF‐RDN) inhibits renal neprilysin activity, increases nitric oxide signaling, and reduces pathologic renin‐angiotensin‐aldosterone signaling in animal models of acute myocardial ischemia–reperfusion injury as well as myocardial ischemia–reperfusion–induced HFrEF. 31 , 32 , 33 These findings suggest that the benefits of RDN in myocardial infarction and HFrEF are partly mediated by the renoprotective actions of RDN. Preservation of renal integrity is critical in HFpEF populations as renal dysfunction is associated with a higher incidence of all‐cause and cardiovascular mortality, as well as HF‐related hospitalizations. 34 Given the evidence of pathologic cardiorenal sympathetic cross‐talk and the importance of adequate renal function in HFpEF, we investigated the effects of RF‐RDN in a rodent model of HFpEF with concomitant renal disease. 35 , 36

METHODS

The data that support the findings of this research article are available upon request to the corresponding author.

Experimental Animals

Male Zucker Spontaneously Fatty 1 (ZSF1) obese rats were purchased from Charles Rivers Breeding Laboratories (Wilmington, MA) at an age of either 6 weeks or 18 weeks. Animals were allowed to acclimate at Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center–New Orleans for a minimum of 1 week prior to randomization to RDN or sham procedure. The sample size for the data presented varies due to procedural complications, postoperative complications, limited sample collection (ie, plasma volume), or lack of participation in involuntary treadmill running. All experimental protocols were approved by the Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center–New Orleans Institute for Animal Care and Use Committee (Protocol #3790) and conformed to the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

RDN Procedure

RF‐RDN was performed as previously described. 32 , 37 Animals were randomly assigned to bilateral RF‐RDN or sham RDN (sham‐RDN) at either 8 weeks or 20 weeks of age. All surgical procedures were performed using aseptic techniques. Anesthesia was induced with 5% isoflurane and maintained at 2% to 3% isoflurane for the remainder of the procedure. A 3‐cm flank incision was made to access the right renal artery with a segment (~4 mm) of the renal artery subsequently dissected and isolated. Prior to RF‐RDN, a small sterile plastic strip was placed under the renal artery to prevent tissue injury to underlying structures and other organs. For the RF‐RDN group, a 6F radiofrequency probe (Celsius Electrophysiology Cather, Biosense Webster) was positioned 4 times circumferentially around the renal artery and at each position and a 20‐second ablation at 10 W of radiofrequency energy (Stockert 70 RF generator, Biosense Webster) was performed. The probe temperature was not allowed to exceed 65 °C to minimize renal artery injury. For the sham‐RDN group, the probe was similarly positioned around the renal artery and held for 20 seconds on each face with 0 W of radiofrequency energy administered at each position. Following RF‐RDN ablation, the plastic strip was removed and the surgical site was closed. The same procedure was then performed on the contralateral renal artery.

Transthoracic Echocardiography

Echocardiography was performed utilizing a Vevo‐2100 ultrasound system (Visual Sonics). LV ejection fraction and ventricular wall dimensions were measured using a series of 3 M‐mode images (apical, middle, base) across the parasternal long‐axis view. Early filling velocity (E), atrial filling velocity (A), and early diastolic tissue velocity (E') were measured in the 4‐chamber apical view. Animals were induced at 5% isoflurane and maintained at 1% to 3% isoflurane for a target heart rate of 270 to 310 beats per minute for diastolic measures and >300 beats per minute for systolic measures.

Exercise Capacity Testing

Rats were introduced to a flat‐plane treadmill (IITC Life Sciences) with a 5‐minute acclimation period. Following acclimation, a warmup protocol was initiated consisting of a starting speed of 6 m/min that increased by 1.5 m/min until a final speed of 12 m/min was achieved and maintained for 60 seconds. Animals were then placed on the treadmill, which was maintained at a rate of 12 m/min until animal exhaustion, determined by refusal to run for >5 consecutive seconds or the inability to reach the front of the treadmill for 20 consecutive seconds. Exercise capacity was plotted as total distance traveled during the experimental run after warmup.

Systemic and LV Hemodynamics

Systemic and LV pressures were measured at euthanasia as previously described with slight modifications. 38 At the 28‐week age end point, animals were anesthetized using 3% isoflurane until unresponsive to stimuli. Animals were maintained at 2% to 3% isoflurane while the right common carotid artery was surgically isolated and exposed. Once exposed, the isoflurane was reduced to 1% while a 1.6F transonic high‐fidelity pressure catheter (Transonic) was inserted in the carotid artery and measurements of systemic BPs were recorded. The catheter was then advanced into the LV lumen, and LV end‐diastolic pressure and Tau were recorded.

Vascular Reactivity Studies in Isolated Aortic Rings

Vascular reactivity of isolated aortic rings was performed in all animals at the 28‐week end point as previously described. 39 , 40 Isolated thoracic aorta segments (2–3 mm) were obtained and equilibrated in oxygenated Krebs–Henseleit solution with force tension for 60 to 90 minutes, at which time a stable resting tension ≈1.5 to 2 g was achieved. Rings were then precontracted with phenylephrine (1 μmol/L) and immediately thereafter challenged with either increasing concentrations of acetylcholine (10−9 to 10−5 mol/L) for assessment of endothelial‐dependent vasorelaxation or sodium nitroprusside (10−9 to 10−5 mol/L) for assessment of endothelial‐independent vasorelaxation. Data are reported as percent relaxation from the maximum contraction to phenylephrine.

Conscious BP Recordings

At 16 weeks of age, a subset of rats in the ZSF1 obese rats in the late RDN cohort were implanted with BP radiotelemeter devices (Data Science International, DSI). Animals were anesthetized with 2% to 3% isoflurane while the right femoral artery was isolated, and the telemetry probe was advanced and secured in the abdominal aorta. Animals were allowed to recover for 2 weeks prior to the collection of conscious BP (systolic and diastolic) and heart rate was recorded. BP and heart rate were recorded weekly and reported measurements represent the value across a 12‐hour average from 6 pm to 6 am. Weeks without respective values were the result of an incomplete 12‐hour acquisition window.

Renal Tissue Norepinephrine Content

Renal norepinephrine content was measured as previously described at a core laboratory at Michigan State University. 33 , 41 During euthanasia, renal cortex tissue samples were harvested from the left and right kidneys in each animal. Renal tissue samples were frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C until catecholamine levels could be measured. Tissue homogenates were assayed using high‐performance liquid chromatography and data are presented as nanogram(s) of norepinephrine per milligram of total tissue.

Renal Artery Tyrosine Hydroxylase Staining

Immunohistochemistry to determine tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) levels was performed (StageBio) on renal arteries from sham‐RDN– and RF‐RDN–treated animals as previously described to assess renal sympathetic nerve viability. 33 At 28 weeks of age, renal arteries were excised and preserved in formalin. Two sections, 1 proximal and 1 distal to the descending aorta, were made and further paraffin‐embedded, sectioned (3 μm) and stained with TH. The stained samples were then placed on glass slides and analyzed in a blinded fashion.

Histological Assessment of Renal and Cardiac Tissues

Renal cortex and LV cardiac tissue were harvested at the time of euthanasia and preserved in formalin. Renal and cardiac tissue samples imbedded in paraffin, sectioned into 3‐μm‐thick cross sections and stained with Masson trichrome for subsequent determination of interstitial and perivascular fibrosis in a blinded fashion. To quantify interstitial fibrosis, 7 to 10 images were taken at ×20 magnification using an Olympus (model BX53‐DP80) and analyzed for fibrotic content using ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health). For perivascular fibrosis, 5 to 8 medium‐large arteries were imaged at ×20 magnification and similarly analyzed. Renal cortical tissue was additionally assessed for glomerular hypertrophy and tubular hyalinization. All imaging and analyses were performed in a blinded fashion. Derived values are represented as averages across all respective slide images in each study group.

Renal Biomarker Analysis

Circulating acute kidney injury marker 1 (KIM‐1) was evaluated using a commercially available ELISA kit (ab223858, Abcam) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Plasma samples were sent to IDEXX Bioanalytics for quantification of circulating blood urea nitrogen and albumin.

Real‐Time Polymerase Chain Reaction

For polymerase chain reaction analysis, RNA was precipitated from renal cortex or myocardial tissue in TriReagent (AM9738, Invitrogen). Samples were then added to RNeasy spin columns (74 104, Qiagen) and manufacturer's instructions were followed. RNA integrity (A260/280 >2.0) and quantity was determined using a NanoDrop One MicroVolume UV–Vis Spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher). Reverse transcription was performed using a high‐capacity reverse transcription kit (4 368 813, Thermo Fisher) and RNAsin (N2515, Promega) with manufacturer's instructions followed to yield complementary DNA. We assessed the expression of acute renal injury, oxidative stress, inflammation, and fibrotic genes using SYBR Green premix (RR42LR, Takara Bio USA) as the detector and primers listed in the Table. Real‐time polymerase chain reaction experiments were performed on a QuantStudio 6 Pro Real‐Time PCR system (Applied Biosystems). Genes were run in triplicate and expression data were determined as the quantity mean, yielded from the standard curve linear regression, and further normalized to internal control CycloA. Data are represented as relative expression to sham‐RDN gene expression.

Table .

Primer List for PCR Experiments in Renal and Cardiac Tissue

| Gene target | Forward sequence | Reverse sequence |

|---|---|---|

| CycloA | CCACTGTCGCTTTTCGCCGC | TGCAAACAGCTCGAAGGAGACGC |

| IL‐6 | TCCGGAGAGGAGACTTCACA | ACAGTGCATCATCGCTGTTC |

| TGFβ1 | GTCAACTGTGGAGCAACACG | TTCCGTCTCCTTGGTTCAGC |

| Col1a1 | TGACGCATGGCCAAGAAGA | CGTGCCATTGTGGCAGATAC |

| Col3a1 | TCCCCTGGAATCTGTGAATC | TGAGTCGAATTGGGGAGAAT |

| KIM‐1 | CACCTCAGCAGTTGTCTCAT | TCTCCACCTCTACTCCAACAC |

| NGAL | GCACATCGTAGCTCTGTATCTG | GTCACTTCCATCCTCGTCAG |

| TNFα | CATCTTCTCAAAACTCGAGTGACAA | TGGGAGTAGATAAGGTACAGCCC |

| IL‐18 | ACCACTTTGGCAGACTTCACT | ACACAGGCGGGTTTCTTTTG |

| IL‐1β | CAGCAGCATCTCGACAAGAG | CATCATCCCACGAGTCACAG |

| NLRP3 | TGATGCATGCACGTCTAATCTC | CAAATCGAGATGCGGGAGAG |

| ASC | TGGCTACTGCAACCAGTGTC | GGCTGGAGCAAAGCTAAAGA |

| Casp1 | CCGTGGAGAGAAACAAGGAG | GGACAGGATGTCTCCAGGAC |

| SOD1 | GTCCTTTCCAGCAGTCACAT | GGTTCCACGTCCATCAGTATG |

| GPX1 | AGGTCGGACGTACTTGAGG | GACTACACCGAGATGAACGAT |

| NOX4 | AATGAAGGGCAGAATCTCAGAG | TCCACTGAAACCAAAGCAACA |

The primer abbreviations represent the following: ASC, apoptosis‐associated speck‐like protein containing a caspase recruitment domain; Casp‐1, caspase 1; Col1a1, collagen type 1 alpha 1 chain; Col3a1, collagen type 3 alpha 1 chain; CycloA, cyclophilin A; GPX1, glutathione peroxidase 1; IL‐6, interleukin 6; IL‐18, interleukin 18; IL‐1β, interleukin 1 beta; KIM‐1, kidney injury marker 1; NGAL, neutrophil gelatinase‐associated lipocalin; NLRP3, NLR family pyrin domain containing 3; NOX4, NADPH oxidase 4; SOD1, superoxide dismutase 1; TGFβ1, transforming growth factor beta 1; TNFα, tumor necrosis factor alpha.

ASC indicates apoptosis‐associated speck‐like protein containing a caspase recruitment domain; Casp‐1, caspase 1; Col1a1, collagen type 1 alpha 1 chain; Col3a1, collagen type 3 alpha 1 chain; cycloA, cyclophilin A; GPX1, glutathione peroxidase 1; IL, interleukin; KIM‐1, kidney injury marker 1; NGAL, neutrophil gelatinase–associated lipocalin; NLRP3, NLR family pyrin domain containing 3; NOX4, NADPH oxidase 4; PCR, polymerase chain reaction; SOD1, superoxide dismutase 1; TGFβ1, transforming growth factor β1; and TNFα, tumor necrosis factor α.

Statistical Analysis

All data were analyzed in a blinded manner until all measurements were complete. All data were analyzed using Prism 8 (GraphPad Software). Group sizes of 6 to 8 were determined using a power and sample analysis with a significance level at 5% and power at 80%. Prior to conducting statistical analysis, outlier testing using the ROUT method (Q=1%) through GraphPad were conducted and outliers were subsequently removed. For comparison within groups, we used unpaired 2‐tailed Student t test for groups ≥6 and Mann–Whitney U test for groups <6. For our vascular reactivity assay, body weight, and conscious BP measurements, results were compared used a repeated‐measures 2‐way ANOVA with a Bonferroni‐corrected multiple comparisons test. A P value <0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. All data are represented as mean±SEM.

RESULTS

Early RF‐RDN Reduces Renal Sympathetic Innervation and Improves HFpEF Pathology

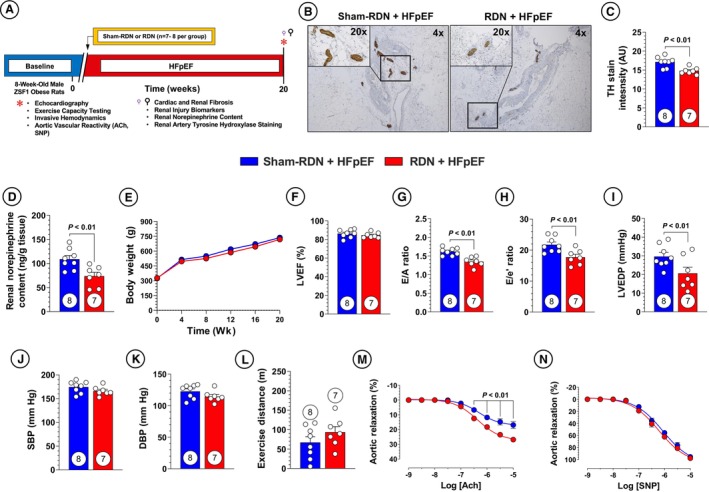

Eight‐week‐old male ZSF1 obese rats were subjected to either bilateral RF‐RDN or sham‐RDN procedures and monitored for 20 weeks as described in the experimental protocol (Figure 1A). To confirm adequate denervation, we evaluated renal nerve TH straining, as well as overall renal tissue norepinephrine content (Figure 1B through 1D). We observed significant reductions in overall TH staining (Figure 1C) as well as significant reductions in renal NE content (Figure 1D). There were no differences in body weight between treatment groups and all animals exhibited an ejection fraction ≥60%, consistent with an HFpEF phenotype (Figure 1E and 1F). Similarly, there were no changes in ventricular wall or chamber dimensions between RDN‐ and sham‐RDN–treated animals as well as no changes in gross heart weights (Figure S1A through S1G). However, animals treated with RDN at 8 weeks of age displayed reductions in both E/A and E/mitral annular early diastolic velocity (e') ratio, suggesting that RDN attenuates LV diastolic dysfunction seen in the ZSF1 obese rat (Figure 1G and 1H). We additionally performed LV catheterization and observed significant reductions in LV end‐diastolic pressure, consistent with our echocardiographic findings (Figure 1I). There were no significant differences in relaxation constant τ associated with RDN treatment (Figure S1H). Interestingly, we did not observe any significant reductions in either systolic or diastolic BP with RDN treatment when measured at the 20‐week study end point during the hemodynamics procedure (Figure 1J and 1K). These data suggest that the effects of RDN on LV diastolic function are unrelated to changes in BP and corroborate previous investigations of BP‐independent effects of RDN in cardiovascular disease. 31 , 33

Figure 1. Early renal denervation (RDN) reduces sympathetic activity and severity of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) in Zucker Spontaneously Fatty 1 (ZSF1) obese rats.

A, Study timeline. B, Representative imaging of tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) staining at ×4 and ×20 magnification. C, Quantification of TH staining in renal nerves. D, Renal cortex norepinephrine content. E, Body weight. F, Left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF). G, Ratio of early mitral diastolic inflow velocity (E) and atrial mitral diastolic inflow velocity (A). H, Ratio of E and mitral annular early diastolic velocity (e'). I, Left ventricular end‐diastolic pressure (LVEDP). J, Systolic blood pressure (SBP). K, Diastolic blood pressure (DBP). L, Treadmill exercise distance. M, Aortic vascular reactivity to acetylcholine (ACh). N, Aortic vascular reactivity to sodium nitroprusside (SNP). Circles inside bars indicate sample size. Data in (C) through (D) and (F) through (L) were analyzed with unpaired 2‐tailed Student t test. Data in (E), (M), and (N) were analyzed with repeated measures 2‐way ANOVA. Data are presented as mean±SEM. sham‐RDN indicates sham renal denervation.

Diminished exercise capacity is a hallmark of HFpEF pathology, and as such we evaluated the effects of RDN on involuntary treadmill exercise capacity and saw no improvements (Figure 1L). 42 However, RDN therapy resulted in meaningful improvements in aortic ring vascular vasorelaxation to acetylcholine (Figure 1M). These data indicate that RDN preserves vascular endothelial function and nitric oxide production in large, conduit vessels in the setting of cardiometabolic HFpEF. These data are significant in that the RDN procedure was applied in the renal artery, and we observed improvements in vascular endothelium at remote anatomical sites. Aortic vascular ring relaxation to sodium nitroprusside (Figure 1N) was not different between the RF‐RDN and sham‐RDN groups, suggesting that the vascular injury observed in this preclinical model of HFpEF is restricted to endothelial dysfunction characterized by reduced nitric oxide bioavailability. These results could be significant in that large artery stiffness has been proposed as a pathophysiological driver of HFpEF, meaning the observed RDN‐mediated benefits in aortic vasorelaxation could provide an additional implication for use of RDN in HFpEF. 43

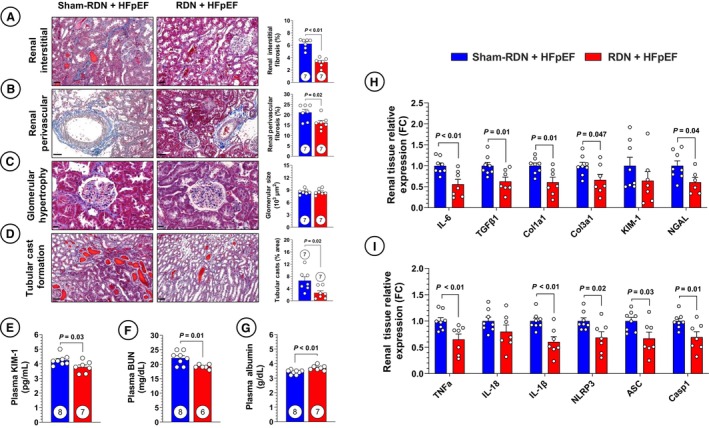

Early RDN Attenuates Renal Fibrosis and Injury in HFpEF

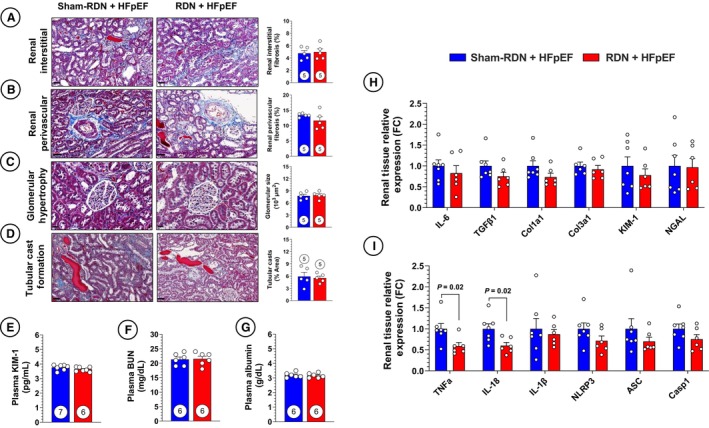

Glomerulosclerosis and overall renal fibrosis are features of renal pathology that have previously been shown to be ameliorated following RDN. 32 , 44 The antifibrotic effects of RDN are of particular interest considering the ZSF1 obese rat model displays significant renal and cardiac fibrosis. 36 , 45 We investigated renal interstitial fibrosis as well as perivascular fibrosis of the renal vasculature and observed significant reductions in both compartments with RDN treatment (Figure 2A and 2B). Other prominent features of renal pathology include glomerular hypertrophy and tubular cast formation. To this end, we evaluated renal glomerular hypertrophy and tubular cast formation at 20 weeks following RF‐RDN and failed to observe any attenuation in glomerular hypertrophy as shown in Figure 2C. However, early RDN therapy resulted in diminished tubular cast abundance (Figure 2D).

Figure 2. Early renal denervation (RDN) remediates renal fibrosis and NLRP3 inflammasome synthesis.

A, Representative images of renal interstitial fibrosis in sham RDN (sham‐RDN; left) and RDN‐treated (right) animals stained with Masson trichrome and quantification of renal interstitial fibrosis. B, Representative images of renal medium‐large arteries and quantification of renal perivascular fibrosis. C, Representative images and quantification of glomerular size. D, Representative images and quantification of cast abundance in renal tubules. E, Circulating kidney injury marker‐1 (KIM‐1). F, Circulating blood urea nitrogen (BUN). G, Circulating albumin. H, Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) quantification of profibrotic gene expression in renal tissue. I, PCR quantification of proinflammatory and NLR family pyrin domain containing 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome‐related gene expression in renal tissue. Circles inside bars indicate sample size. Data in (A) through (I) were analyzed with unpaired 2‐tailed Student t test. Data are presented as mean±SEM. ASC indicates apoptosis‐associated speck‐like protein containing a caspase recruitment domain; Casp‐1, caspase 1; Col1a1, collagen type 1 alpha 1 chain; Col3a1, collagen type 3 alpha 1 chain; FC, fold change; IL, interleukin; NGAL, neutrophil gelatinase–associated lipocalin; TGFβ1, transforming growth factor β1; and TNFα, tumor necrosis factor α.

The observed reductions in renal histopathology following RF‐RDN therapy were accompanied by decreased serum KIM‐1, a clinically relevant marker of acute renal tubular injury, and decreased blood urea nitrogen (Figure 2E and 2F). 46 We also observed a significant increase in serum albumin with RDN treatment (Figure 2G). While many factors contribute to serum albumin levels, the increases in serum albumin exhibited by RDN‐treated animals suggests a benefit in terms of reduced albuminuria or an anti‐inflammatory effect of RDN, given albumin is a negative acute‐phase protein. 47 Supporting the antifibrotic effects of RDN in our study, expression of profibrotic markers interleukin (IL‐6), transforming growth factor β1, collagen type 1 alpha 1 chain, and collagen type 3 alpha 1 chain was decreased in renal cortical tissue (Figure 2H). We similarly investigated the expression of KIM‐1 as well as another pertinent marker of acute tubular injury, neutrophil gelatinase–associated lipocalin 2, and observed no RDN‐mediated effects on KIM‐1 expression but a decrease in neutrophil gelatinase–associated lipocalin expression (Figure 2H). 48 While KIM‐1 expression was not decreased, RDN‐treated animals exhibited reduced circulating KIM‐1, which is likely of greater clinical relevance for this specific biomarker.

Regarding mechanistic pathways responsible for the effects in our study, we considered the potential anti‐inflammatory effects of RDN, given that HFpEF is a syndrome characterized by low‐grade systemic inflammation. 49 Previous work in hypertensive patients revealed that RDN is able to reduce monocyte activation and trafficking, including reduction of monocyte‐related chemokines monocyte chemoattractant protein 1, IL‐6, tumor necrosis factor α (TNF‐α), IL‐12, and IL‐1β. 50 One proinflammatory pathway recently shown to be under sympathetic control is activation of the NLR family pyrin domain containing 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome. 51 The NLRP3 inflammasome is the principal pathway leading to activation of IL‐1β through a caspase‐1–dependent mechanism. 52 To determine whether this inflammasome plays a role in our findings, we first quantified expression of inflammatory chemokines TNF‐α, IL‐18, and IL‐1β and saw reductions in TNF‐α and IL‐1β, consistent with previous findings in RDN‐treated hypertensive patients (Figure 2I). The highly significant reductions in IL‐1β expression with RDN treatment led us to further investigate the NLRP3 inflammasome, where we saw reductions in all 3 inflammasome components (NLRP3, apoptosis‐associated speck‐like protein containing a caspase recruitment domain, and caspase‐1) in renal cortical tissue (Figure 2I). These data suggest that renal IL‐1β production and pro–IL‐1β signaling is under sympathetic influence, amenable via RDN treatment, and is part of the benefits of RDN in HFpEF.

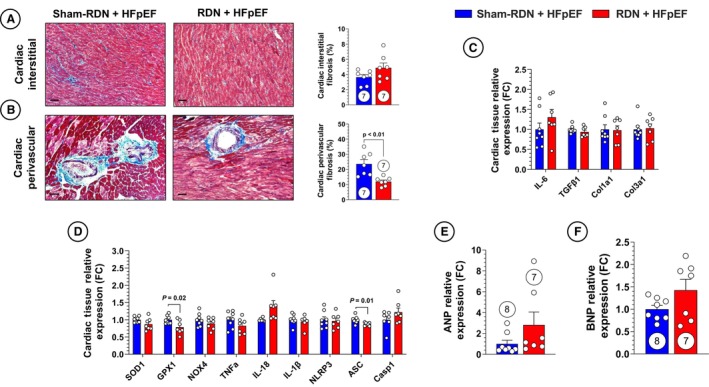

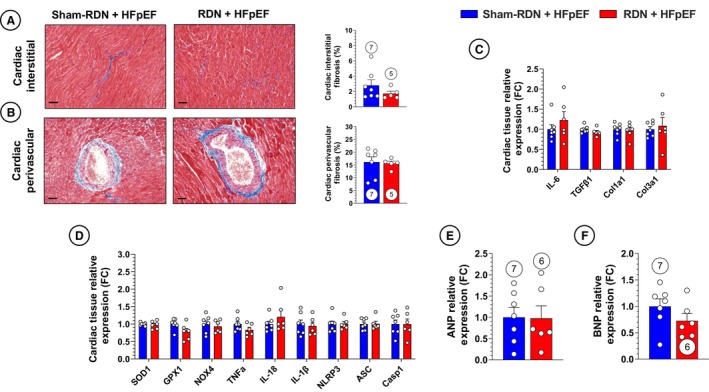

Early RF‐RDN Attenuates Cardiac Perivascular Fibrosis in the Absence of Anti‐Inflammatory Effects

We have previously reported that RDN attenuates renal neprilysin activity in a rodent HFrEF model, which was associated with attenuation of cardiac fibrosis. 31 In the present study, we quantified interstitial and perivascular cardiac fibrosis at 20 weeks following sham‐RDN or RF‐RDN. We observed a significant decrease in cardiac perivascular fibrosis following RDN treatment; however, there were no reductions in interstitial fibrosis (Figure 3A and 3B). Cardiac fibrosis initially occurs in the perivascular space with ensuing inflammatory cell infiltration leading to dispersed interstitial fibrosis. 53 , 54 The differences in perivascular and interstitial fibrosis pathogenesis suggest that the cardiovascular benefits of RDN are related to improved fluid homeostasis or vascular function secondary to improved renal function, rather than a direct antifibrotic or anti‐inflammatory effect at the heart. These results are supported by a lack of reduction in cardiac profibrotic and fibrotic gene expression (Figure 3C). We also investigated whether ablation of renal sympathetic activity impacts oxidative stress, inflammatory, and NLRP3‐related cardiac gene expression. We observed modest reductions in cardiac glutathione peroxidase 1 and apoptosis‐associated speck‐like protein containing a caspase recruitment domain expression without any significant changes in other proteins that modulate oxidative stress, inflammation, or cell death (Figure 3D). Atrial and brain natriuretic peptide expression were also measured, to which there were no significant changes (Figure 3E and 3F). These data suggest that the benefits of RDN on cardiovascular function in HFpEF are likely related to peripherally mediated mechanisms (ie, improved fluid homeostasis and vascular health maintenance) or other cardiocentric mechanisms not evaluated.

Figure 3. Early renal denervation (RDN) improves cardiac fibrosis without affecting cardiac NLR family pyrin domain containing 3 (NLRP3) synthesis.

A, Representative images of cardiac interstitial fibrosis in sham RDN (sham‐RDN; left) and RDN‐treated (right) animals stained with Masson trichrome and quantification of cardiac interstitial fibrosis. B, Representative images of cardiac medium‐large arteries and quantification of cardiac perivascular fibrosis. C, Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) quantification of profibrotic gene expression in cardiac tissue. D, PCR quantification of proinflammatory and NLRP3 inflammasome‐related gene expression in cardiac tissue. E, PCR quantification of atrial natriuretic peptide (ANP) gene expression in cardiac tissue. F, PCR quantification of brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) gene expression in cardiac tissue. Circles inside bars indicate sample size. Data in (A) through (F) were analyzed with unpaired 2‐tailed Student t test. Data are presented as mean±SEM. ASC indicates apoptosis‐associated speck‐like protein containing a caspase recruitment domain; Casp‐1, caspase 1; Col1a1, collagen type 1 alpha 1 chain; Col3a1, collagen type 3 alpha 1 chain; FC, fold change; GPX1, glutathione peroxidase 1; IL, interleukin; NOX4, NADPH oxidase 4; SOD1, superoxide dismutase 1; TGFβ1, transforming growth factor beta 1; and TNFα, tumor necrosis factor α.

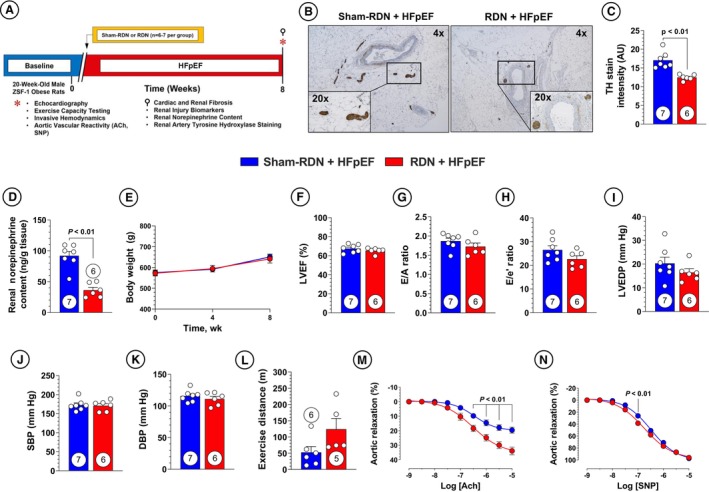

Cardiorenal Benefits of RDN Are Diminished in End‐Stage HFpEF

To further evaluate the effects of RDN in HFpEF, we performed RF‐RDN at a later stage to more closely mimic HFpEF in patients with established and severe disease. We subjected 20‐week‐old male ZSF1 obese rats to bilateral RF‐RDN or sham‐RDN procedures and subsequently monitored the animals for 8 weeks as described in Figure 4A. Renal sympathetic function was similarly downregulated following RDN as shown in Figure 4B through 4D. Animals receiving RF‐RDN at 20 weeks of age did not exhibit changes in body weight compared with sham‐RDN–treated animals, and both groups maintained preserved ejection fractions (Figure 4E and 4F). No changes in ventricular dimensions or heart weights were observed between the late RDN treatment groups (Figure S2A through S2G). However, late‐stage RF‐RDN treatment failed to result in any significant improvement in LV diastolic function (ie, E/A or E/e') or LV end‐diastolic pressure in contrast to RDN therapy at 8 weeks of age (ie, early RDN) (Figure 4G through 4I). Significant reductions in relaxation constant τ were observed in the late RDN treatment group when compared with their sham‐RDN controls (Figure S2H). Consistent with the early RDN study group, we also saw no reduction in BP or improvements in exercise capacity following treatment (Figure 4J through 4L). Given our findings of unchanged BP following RDN treatment when measured at a single timepoint at the termination of the study protocol, we interrogated the effects of RDN on conscious BP using radiotelemetry devices in the ZSF1 obese rat. In these experiments, 12‐hour conscious BP recordings confirmed the lack of an antihypertensive effect of RDN in the ZSF1 obese rat (Figure S3A through S3D). Our previous experiments of RDN therapy in spontaneously hypertensive rats in the setting of HFrEF failed to demonstrate any effects of RDN on systemic BPs despite beneficial effects in terms of improved LV systolic function and reductions in myocardial fibrosis. 31 RDN therapy did result in improved aortic ring vasorelaxation to acetylcholine combined with a modest increase in vasomotor response to sodium nitroprusside in the late RF‐RDN–treated group (Figure 4M and 4N). The lack of an explicit reduction in BP with RDN treatment but improved ex vivo aortic vasorelaxation in both our early and late RDN cohorts are in line with previous RDN investigations and highlight the complex mechanisms that govern systemic BP that likewise expand beyond isolated, large artery vasoreactivity. 31

Figure 4. Late renal denervation (RDN) intervention attenuates RDN benefits in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF).

A, Study timeline. B, Representative imaging of tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) staining at ×4 and ×20 magnification. C, Quantification of TH staining in renal nerves. D, Renal cortex norepinephrine content. E, Body weight. F, Left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF). G, Ratio of early mitral diastolic inflow velocity (E) and atrial mitral diastolic inflow velocity (A). H, Ratio of E and mitral annular early diastolic velocity (e'). I, Left ventricular end‐diastolic pressure (LVEDP). J, Systolic blood pressure (SBP). K, Diastolic blood pressure (DBP). L, Treadmill exercise distance. M, Aortic vascular reactivity to acetylcholine (ACh). N, Aortic vascular reactivity to sodium nitroprusside (SNP). Circles inside bars indicate sample size. Data in (C) through (D) and (F) through (L) were analyzed with unpaired 2‐tailed Student t test. Data in (E), (M), and (N) were analyzed with repeated‐measures 2‐way ANOVA. Data are presented as mean±SEM.

Late RDN Therapy Fails to Attenuate Renal and Cardiac Fibrosis and Inflammation

Histological characterization of renal fibrosis and injury in sham‐RDN and RF‐RDN animals at 28 weeks revealed no differences as shown in Figure 5A through 5D. Similarly, we did not observe any appreciable changes in circulating markers of renal injury and function as well as profibrotic and renal injury gene expression described in Figure 5E through 5H. Interestingly, TNF‐α and IL‐18 expression were downregulated following RDN treatment in the absence of any alterations in the NLRP3/IL‐1β pathway (Figure 5I). This suggests that the reductions in renal TNF‐α expression by real‐time polymerase chain reaction in the early RDN treatment did not significantly contribute to the benefits in renal function and HFpEF pathology observed.

Figure 5. Late renal denervation (RDN) intervention does not influence renal NLR family pyrin domain containing 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome synthesis.

A, Representative images of renal interstitial fibrosis in sham RDN (sham‐RDN) (left) and RDN‐treated (right) animals stained with Masson trichrome and quantification of renal interstitial fibrosis. B, Representative images of renal medium‐large arteries and quantification of renal perivascular fibrosis. C, Representative images and quantification of glomerular size. D, Representative images and quantification of cast abundance in renal tubules. E, Circulating kidney injury marker‐1 (KIM‐1). F, Circulating blood urea nitrogen (BUN). G, Circulating albumin. H, Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) quantification of profibrotic gene expression in renal tissue. I, PCR quantification of proinflammatory and NLRP3 inflammasome‐related gene expression in renal tissue. Circles inside bars indicate sample size. Data in (A) through (D) were analyzed with 2‐tailed Mann–Whitney U test. Data in panels (E) through (I) were analyzed with unpaired 2‐tailed Student t test. Data are presented as mean±SEM. ASC indicates apoptosis‐associated speck‐like protein containing a caspase recruitment domain; Casp‐1, caspase 1; Col1a1, collagen type 1 alpha 1 chain; Col3a1, collagen type 3 alpha 1 chain; FC, fold change; IL, interleukin; NGAL, neutrophil gelatinase–associated lipocalin; TGFβ1, transforming growth factor beta 1; and TNFα, tumor necrosis factor alpha.

Histological evaluation of cardiac tissue from late‐stage RDN– and sham‐RDN–treated animals (Figure 6A and 6B) similarly showed no differences in interstitial fibrosis or perivascular fibrosis. Cardiac tissue expression of profibrotic gene expression was also not impacted by RDN treatment, supporting the hypothesis that late‐stage RDN in our study did not exhibit antifibrotic effects (Figure 6C). Last, no differences were witnessed in cardiac oxidative stress, inflammatory, NLRP3/IL‐1β, or natriuretic peptide gene expression (Figure 6D through 6F). Taken together, these results show that RDN performed at a later, more severe stage of HFpEF was not effective in remediating HFpEF pathological burden and emphasizes the need for examination of therapeutic interventions not only in early disease but also in established, severe disease.

Figure 6. Cardiac histopathology unaffected by late renal denervation (RDN) intervention.

A, Representative images of cardiac interstitial fibrosis in sham‐RDN (left) and RDN‐treated (right) animals stained with Masson trichrome and quantification of cardiac interstitial fibrosis. B, Representative images of cardiac medium‐large arteries and quantification of cardiac perivascular fibrosis. C, Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) quantification of profibrotic gene expression in cardiac tissue. D, PCR quantification of proinflammatory and NLR family pyrin domain containing 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome‐related gene expression in cardiac tissue. E, PCR quantification of atrial natriuretic peptide (ANP) gene expression in cardiac tissue. F, PCR quantification of brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) gene expression in cardiac tissue. Circles inside bars indicate sample size. Data in panels (A) through (F) were analyzed with unpaired 2‐tailed Student t test. Data are presented as mean±SEM. ASC indicates apoptosis‐associated speck‐like protein containing a caspase recruitment domain; Casp‐1, caspase 1; Col1a1, collagen type 1 alpha 1 chain; Col3a1, collagen type 3 alpha 1 chain; FC, fold change; GPX1, glutathione peroxidase 1; IL, interleukin; NOX4, NADPH oxidase 4; SOD1, superoxide dismutase 1; TGFβ1, transforming growth factor beta 1; and TNFα, tumor necrosis factor alpha.

DISCUSSION

Pathological activation of the SNS is considered to be a major driver in the pathogenesis of cardiovascular diseases including HF. 55 However, given the highly complex nature of HFpEF, the current therapeutic approaches to downregulate deleterious SNS overactivation should be reconsidered. RDN therapy using radiofrequency energy, ultrasound energy, or chemical ablation has emerged as a viable treatment option for resistant hypertension that targets sympathetic signaling at a proximal point in this highly pathological signaling cascade. 16 , 56 , 57 We postulated that implementing this device‐mediated intervention would provide more sustained and powerful sympathoinhibitory effects on cardiorenal signaling in HFpEF. Through our investigation, we were able to elucidate that: (1) early treatment of HFpEF with RDN significantly improves cardiovascular function in the ZSF1 obese rat model of cardiometabolic HFpEF; (2) the beneficial effects of RF‐RDN in HFpEF are likely mediated by a renal‐centric mechanism; (3) one mechanism for the observed benefit is through downregulation of renal NLRP3‐mediated IL‐1β synthesis; and (4) RDN failed to provide the same benefit when performed in later‐stage HFpEF disease in the ZSF1 obese rat.

The ZSF1 obese rat has emerged as a clinically relevant genetic model of cardiometabolic HFpEF given their well‐characterized pathophysiological complexity involving hypertension, obesity, and diabetes that closely mimics human HFpEF. 35 The ZSF1 obese rat has also been extensively studied as a model of diabetic nephropathy and severe renal disease, making it appropriate for investigation of the cardiac as well as the renal consequences of HFpEF. 36 , 58 While the primary benefit of RDN is BP reduction, in our study, RF‐RDN did not significantly reduce systemic BP despite reductions in renal norepinephrine and improvements in vascular endothelial function. Our results are similar to previous investigations of RF‐RDN in preclinical models of cardiovascular disease. 31 , 33 Clinical RDN trials offer conflicting results regarding RDN‐mediated effects on BP, where the SPYRAL‐HTN‐ON MED (Global Clinical Study of Renal Denervation With the Symplicity Spyral Multi‐electrode Renal Denervation System in Patients With Uncontrolled Hypertension on Standard Medical Therapy) trial displayed reductions in BP irrespective of concomitant antihypertensive treatment; however, the SYMPLICITY HTN‐3 (Renal Denervation in Patients With Uncontrolled Hypertension) trial failed to show significant BP reductions on RDN treatment. 18 , 19 In the present study, RDN therapy resulted in significant benefits including improved LV diastolic function, reduced LV filling pressures, and renoprotection including attenuated renal fibrosis in the absence of reductions in systolic or diastolic BP when applied at an early stage in HFpEF progression.

The LV diastolic functional benefits of RDN have previously been reported by Brandt et al, 27 where patients with resistant hypertension who subsequently received RDN exhibited improvements in mitral valve E/e' and isovolumetric relaxation time. In a similar study performed by Kresoja et al, 30 patients with HFpEF who previously received RDN for hypertension exhibited a less severe cardiovascular phenotype with improved diastolic function in comparison to patients with untreated HFpEF. In the Kresoja et al study, 30 patients with arterial hypertension who are at risk for development of HFpEF may represent a pre‐HFpEF state that is most amenable to therapies such as RDN, whereas patients with severe HFpEF may not achieve the same benefits, corresponding to our experimental findings. While we failed to observe antihypertensive effects from RDN, the detrimental effects of hypertension on diastolic function have been extensively reported, supporting the idea that any further BP‐lowering effects of RDN would likely further improve diastolic function in future studies. 59

Renoprotection is a well‐documented benefit of RDN that might provide insight into the mechanisms by which RDN improves cardiac function in HFpEF. 60 Chronic kidney disease (CKD) has been shown to be an independent predictor of HF diagnosis, hospitalization, and HF‐related morbidity and mortality. 34 , 61 , 62 The mounting evidence of cardiorenal involvement on HFpEF diagnosis and progression has led investigators to develop HFpEF phenotypes specific for CKD alone or as a key contributor to the phenotypic pathology, where CKD‐associated HFpEF involves notably depleted cardiac function compared with other phenotypes. 63 , 64 Given that impaired renal function and kidney tissue injury leads to increased cardiovascular severity in patients with HFpEF, it is reasonable to hypothesize that improving or preserving kidney function and tissue integrity could further improve cardiac function in HFpEF.

In our study, RDN‐treated animals exhibited reduced renal fibrosis, acute kidney injury biomarkers, blood urea nitrogen, and tubular cast formation. These changes in renal histopathology and function were accompanied by improvements in key HFpEF cardiac parameters E/e' and LV end‐diastolic pressure. Renoprotection has been shown to be a BP‐independent effect of sympathoinhibition. Preclinical studies on the effects of subhypotensive doses of moxonidine or phenoxybenzamine/metoprolol resulted in reductions of microalbuminuria and glomerulosclerosis. 22 , 65 , 66 These results were validated by Strojek et al, who showed that subhypotensive doses of moxonidine were similarly able to reduce microalbuminuria in patients with type 1 diabetes. 67 Sympathoinhibition through RDN has also been shown to attenuate estimated glomerular filtration rate decline in patients with mild to moderate CKD while also being a valid treatment option in severe CKD, whereas most current HFpEF pharmacotherapies are not recommended for patients with severe CKD. 29 , 68 , 69 Our data do not provide direct insights into the potential cross‐talk between the kidney and heart in HFpEF and how RDN‐mediated renal protection resulted in reductions in cardiac perivascular fibrosis and improved LV function. It is likely that attenuated renal tissue injury and inflammation resulted in improved renal function and fluid homeostasis, thereby reducing LV filling pressures and improving LV function. However, additional studies are required to more fully address this hypothesis.

To explain the renoprotective effects of early RDN in our study, we hypothesized that inflammation, specifically through increased renal IL‐1β synthesis, is a contributor to the observed phenotype. IL‐1β is a potent proinflammatory chemokine largely associated with triggering of the innate immune response. 70 Previous RDN studies have reported that RDN treatment reduces IL‐1β in patient and preclinical models of hypertension and myocardial ischemia–reperfusion. 50 , 71 However, the rate‐limiting step in IL‐1β secretion involves formation of the NLRP3 inflammasome and the aforementioned investigations have not explored the effects of RDN on NLRP3 expression. 72 In our study, RDN reduced expression of renal IL‐1β expression as well as the 3 constituents of the NLRP3 inflammasome (NLRP3, apoptosis‐associated speck‐like protein containing a CARD, caspase‐1), suggesting the reduction in IL‐1β following RDN is likely due to decreased cleavage and secretion of mature IL‐1β. Reduced IL‐1β proinflammatory signaling corroborates many of our experimental findings. IL‐1β secretion through NLRP3 inflammasome activation follows necrotic cell injury as part of a sterile and innate immune response. 73 Inhibition of this pathway through NLRP3−/− KO or IL‐1 receptor antagonism lead to preserved renal function, decreased immune cell trafficking, and decreased tubular cell apoptosis in renal ischemia‐reperfusion models. 73 , 74 In addition, IL‐1β has been shown to independently increase neutrophil gelatinase–associated lipocalin synthesis, whereas other inflammatory mediators (TNF‐α, LPS, IL‐6) did not exhibit the same effects. 75 IL‐1β signaling could also underpin the decreases in KIM‐1 in our studies, as the hypothesized mechanism of KIM‐1 secretion involves ERK1/2 activation, which is under the influence of IL‐1β. 76 , 77

Given the powerful and widespread effects of the SNS, it is plausible to speculate that other mechanisms could be involved with the RDN‐mediated benefits in the early intervention cohort. RDN has been previously shown to downregulate renin‐angiotensin‐aldosterone system signaling and inhibit renal neprilysin, mimicking the effects of angiotensin receptor neprilysin inhibitor therapy. 31 , 33 While PARAGON‐HF (Prospective Comparison of Angiotensin Receptor Neprilysin Inhibitor With Angiotensin Receptor Blocker Global Outcomes in Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction) did not show improvements in the primary composite outcome of HF‐related hospitalization and cardiovascular‐related death, angiotensin receptor neprilysin inhibitor therapy has been shown to improve renal function and had a primary outcome benefit in the subgroup of patients with estimated glomerular filtration rate <60 mL/min per 1.73 m.2 14 Another benefit of RDN not investigated in the current study is its effects on glucose handling and insulin responsivity. 78 Hyperinsulinemia, obesity, and metabolic syndrome have all been shown to increase sympathetic activity independent of changes in BP. 79 , 80 , 81 A potential mechanism contributing to this effect is that sympathetic overactivation increases expression of SGLT2 (sodium/glucose cotransporter 2) in the renal proximal tubule, with the renal nerves believed to be the main contributor. 81 , 82 SGLT2 has become a primary target for HFpEF, where SGLT2 inhibitors are the only treatment shown to reduce HF hospitalizations, increase exercise capacity, and improve Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire (KCCQ) scores. 83 , 84 , 85 , 86 Upregulation of SGLT2 expression has been remediated with RDN in HFrEF and diabetic cardiomyopathy models, where treatment with an SGLT2 inhibitor provided no additional benefit compared with the RDN treatment groups. 82 , 87 The ZSF1 obese rat model is plagued by severe metabolic dysregulation and it is possible that SGLT2 inhibition following RF‐RDN could contribute to the beneficial effects observed in the present study.

While our study targeted renal nerve sympathetic influence on HFpEF pathology, splanchnic denervation is a similar strategy being investigated in HFpEF. 88 Splanchnic sympathetic nerves aid in shifting of blood volume between the splanchnic vascular bed and central vascular compartment, insinuating array of this system contributes to whole body and, most notably, pulmonary congestion. 89 , 90 Preliminary HFpEF clinical trials of greater splanchnic nerve denervation resulted in reduced resting and exercise pulmonary capillary wedge pressure as well as improved KCCQ score, New York Heart Association functional class, and diastolic function. 91 , 92 Given the similar yet different aspects of HFpEF pathology addressed by renal and splanchnic denervation, both interventions highlight the widespread influence of pathological SNS activation in HFpEF. Both splanchnic denervation and RDN significantly reduce pathological SNS signaling and could result in meaningful beneficial actions and outcomes in our preclinical model of HFpEF and in the HFpEF patient population. The recent US Food and Drug Administration approval of RDN for the treatment of resistant hypertension and a current trial of RDN in HFpEF (NCT05030987) suggest that RDN may soon become an important tool for remediating HFpEF pathology. This is especially true in patients with a hypertensive‐ or cardiorenal‐driven phenotype as well as patients intolerant or nonadherent to antihypertensive medication regimens. 93 Our data in the ZSF1 obese rat suggest that early treatment with RDN in the setting of hypertension prevents the development of severe HFpEF, and it is possible that early RDN in patients could reduce their progression to HFpEF.

STUDY LIMITATIONS

Our study has a few notable limitations. We investigated only male ZSF1 rats and did not explore sex‐based differences in terms of HFpEF disease pathology and the effects of RF‐RDN in cardiometabolic HFpEF. Female ZSF1 rats have been shown to exhibit a similar cardiac HFpEF phenotype as male ZSF1 rats; however, these studies were conducted in premenopausal rats, and little is known about female ZSF1 renal function. 94 In addition, Shah et al 64 reported that 45% of the CKD‐associated HFpEF phenotype is male, warranting investigation into disease manifestation in both sexes. Based on the results of our current study, additional studies of RF‐RDN therapy in female ZSF1 rats are warranted. In the current study, renal norepinephrine and renal nerve TH were significantly reduced in both RDN therapy cohorts, albeit to a lesser extent than previously reported results using surgical denervation. 95 We contest that despite our lower degree of denervation, significant improvements were observed in our investigation. More complete renal nerve denervation may be required to achieve clinically significant benefit in HFpEF, and a greater degree of denervation in our context would likely augment the beneficial effect of RDN therapy in severe HFpEF.

CONCLUSIONS

We report that ablation of renal sympathetic nerve activity is an effective strategy for sympathetic overactivation in HFpEF. When applied at an early stage, RDN provided cardioprotection and renoprotection in a clinically relevant HFpEF animal model through protection against renal inflammation and renal tissue injury, which were mediated by attenuation of NLRP3/IL‐1β synthesis. RDN failed to exert significant beneficial effects when administered at a later time in the setting of severe cardiometabolic HFpEF in the ZSF1 obese rat. Of importance, our findings, along with most HFpEF clinical trial findings, emphasize that testing of novel treatment strategies after chronic manifestation of this comorbid‐laden disease has led to an inability to observe any meaningful efficacy. Future prospective studies should seek to enroll patients at earlier stages in HFpEF progression, thereby potentially affording greater likelihood of reaching primary outcomes. In addition, further studies in both animals and humans are required to explore the potential of RF‐RDN and other device‐based approaches to mitigate the overactivation of the SNS in the kidney, heart, lungs, and splanchnic circulation.

Sources of Funding

These studies were supported by grants from the NIH (HL146098, HL146514, and HL151398 to D.J.L.; HL159428 to T.T.G.; AA029984 to T.E.S; and U54GM104940 and P20GM135002 to T.D.A.) and from the American Heart Association (award 20POST35200075 to Z.L.). J.E.D. was supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institute of Health under award number TL1TR003016.

Disclosures

S.J.S. has received research grants from AstraZeneca, Corvia, and Pfizer and consulting fees from Abbott, Alleviant, AstraZeneca, Amgen, Aria CV, Axon Therapies, Bayer, Boehringer‐Ingelheim, Boston Scientific, Bristol Myers Squibb, Cyclerion, Cytokinetics, Edwards Lifesciences, Eidos, Imara, Impulse Dynamics, Intellia, Ionis, Lilly, Merck, MyoKardia, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, Pfizer, Prothena, ReCor, Regeneron, Rivus, Sardocor, Shifamed, Tenax, Tenaya, and Ultromics. The remaining authors have no disclosures to report.

Supporting information

Figures S1–S3

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the Fink Laboratory at Michigan State University for their assistance in performing high‐performance liquid chromatography analysis of renal tissue catecholamine levels acknowledge the Cell Biology and Bioimaging Core at Pennington Biomedical Research Center (National Institutes of Health [NIH] 8 P20‐GM103538 and NIH 2P30‐DK072476) for assistance with the histological studies in this investigation.

This article was sent to Yen‐Hung Lin, MD, PhD, Associate Editor, for review by expert referees, editorial decision, and final disposition.

Supplemental Material is available at https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/suppl/10.1161/JAHA.123.032646

For Sources of Funding and Disclosures, see page 15.

References

- 1. Oktay AA, Rich JD, Shah SJ. The emerging epidemic of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Curr Heart Fail Rep. 2013;10:401–410. doi: 10.1007/s11897-013-0155-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Shah KS, Xu H, Matsouaka RA, Bhatt DL, Heidenreich PA, Hernandez AF, Devore AD, Yancy CW, Fonarow GC. Heart failure with preserved, borderline, and reduced ejection fraction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;70:2476–2486. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.08.074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Borlaug BA, Paulus WJ. Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: pathophysiology, diagnosis, and treatment. Eur Heart J. 2011;32:670–679. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehq426 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Borlaug BA. The pathophysiology of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2014;11:507–515. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2014.83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kaye DM, Nanayakkara S, Wang B, Shihata W, Marques FZ, Esler M, Lambert G, Mariani J. Characterization of cardiac sympathetic nervous system and inflammatory activation in HFpEF patients. JACC Basic Transl Sci. 2022;7:116–127. doi: 10.1016/j.jacbts.2021.11.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Straznicky NE, Grima MT, Sari CI, Eikelis N, Lambert EA, Nestel PJ, Esler MD, Dixon JB, Chopra R, Tilbrook AJ, et al. Neuroadrenergic dysfunction along the diabetes continuum. Diabetes. 2012;61:2506–2516. doi: 10.2337/db12-0138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Vaz M, Jennings G, Turner A, Cox H, Lambert G, Esler M. Regional sympathetic nervous activity and oxygen consumption in obese normotensive human subjects. Circulation. 1997;96:3423–3429. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.96.10.3423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Mancia G, Grassi G, Giannattasio C, Seravalle G. Sympathetic activation in the pathogenesis of hypertension and progression of organ damage. Hypertension. 1999;34:724–728. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.34.4.724 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Verloop WL, Beeftink MMA, Santema BT, Bots ML, Blankestijn PJ, Cramer MJ, Doevendans PA, Voskuil M. A systematic review concerning the relation between the sympathetic nervous system and heart failure with preserved left ventricular ejection fraction. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0117332. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0117332 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Conraads VM, Metra M, Kamp O, De Keulenaer GW, Pieske B, Zamorano J, Vardas PE, Böhm M, Dei CL. Effects of the long‐term administration of nebivolol on the clinical symptoms, exercise capacity, and left ventricular function of patients with diastolic dysfunction: results of the ELANDD study. Eur J Heart Fail. 2012;14:219–225. doi: 10.1093/eurjhf/hfr161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Massie BM, Carson PE, McMurray JJ, Komajda M, McKelvie R, Zile MR, Anderson S, Donovan M, Iverson E, Staiger C, et al. Irbesartan in patients with heart failure and preserved ejection fraction. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:2456–2467. doi: 10.1056/nejmoa0805450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Cleland JGF. The perindopril in elderly people with chronic heart failure (PEP‐CHF) study. Eur Heart J. 2006;27:2338–2345. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehl250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Pitt B, Pfeffer MA, Assmann SF, Boineau R, Anand IS, Claggett B, Clausell N, Desai AS, Diaz R, Fleg JL, et al. Spironolactone for heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:1383–1392. doi: 10.1056/nejmoa1313731 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Solomon SD, McMurray JJV, Anand IS, Ge J, Lam CSP, Maggioni AP, Martinez F, Packer M, Pfeffer MA, Pieske B, et al. Angiotensin–neprilysin inhibition in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:1609–1620. doi: 10.1056/nejmoa1908655 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kaye DM, Lefkovits J, Jennings GL, Bergin P, Broughton A, Esler MD. Adverse consequences of high sympathetic nervous activity in the failing human heart. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1995;26:1257–1263. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(95)00332-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Azizi M, Sanghvi K, Saxena M, Gosse P, Reilly JP, Levy T, Rump LC, Persu A, Basile J, Bloch MJ, et al. Ultrasound renal denervation for hypertension resistant to a triple medication pill (RADIANCE‐HTN TRIO): a randomised, multicentre, single‐blind, sham‐controlled trial. Lancet. 2021;397:2476–2486. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(21)00788-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Mahfoud F, Lüscher TF, Andersson B, Baumgartner I, Cifkova R, Dimario C, Doevendans P, Fagard R, Fajadet J, Komajda M, et al. Expert consensus document from the European Society of Cardiology on catheter‐based renal denervation. Eur Heart J. 2013;34:2149–2157. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/eht154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bhatt DL, Kandzari DE, O'Neill WW, D'Agostino R, Flack JM, Katzen BT, Leon MB, Liu M, Mauri L, Negoita M, et al. A controlled trial of renal denervation for resistant hypertension. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:1393–1401. doi: 10.1056/nejmoa1402670 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Mahfoud F, Kandzari DE, Kario K, Townsend RR, Weber MA, Schmieder RE, Tsioufis K, Pocock S, Dimitriadis K, Choi JW, et al. Long‐term efficacy and safety of renal denervation in the presence of antihypertensive drugs (SPYRAL HTN‐ON MED): a randomised, sham‐controlled trial. Lancet. 2022;399:1401–1410. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)00455-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Schlaich MP, Kaye DM, Lambert E, Sommerville M, Socratous F, Esler MD. Relation between cardiac sympathetic activity and hypertensive left ventricular hypertrophy. Circulation. 2003;108:560–565. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000081775.72651.b6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kaur J, Young BE, Fadel PJ. Sympathetic overactivity in chronic kidney disease: consequences and mechanisms. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18:1682. doi: 10.3390/ijms18081682 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Adamczak M, Zeier M, Dikow R, Ritz E. Kidney and hypertension. Kidney Int. 2002;61:S62–S67. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.61.s80.28.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lambert GW, Straznicky NE, Lambert EA, Dixon JB, Schlaich MP. Sympathetic nervous activation in obesity and the metabolic syndrome—causes, consequences and therapeutic implications. Pharmacol Ther. 2010;126:159–172. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2010.02.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Chen P‐S, Chen LS, Fishbein MC, Lin S‐F, Nattel S. Role of the autonomic nervous system in atrial fibrillation. Circ Res. 2014;114:1500–1515. doi: 10.1161/circresaha.114.303772 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Dunlay SM, Roger VL, Redfield MM. Epidemiology of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2017;14:591–602. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2017.65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Mahfoud F, Urban D, Teller D, Linz D, Stawowy P, Hassel JH, Fries P, Dreysse S, Wellnhofer E, Schneider G, et al. Effect of renal denervation on left ventricular mass and function in patients with resistant hypertension: data from a multi‐centre cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging trial. Eur Heart J. 2014;35:2224–2231b. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehu093 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Brandt MC, Mahfoud F, Reda S, Schirmer SH, Erdmann E, Bohm M, Hoppe UC. Renal sympathetic denervation reduces left ventricular hypertrophy and improves cardiac function in patients with resistant hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;59:901–909. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.11.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Feyz L, Theuns DA, Bhagwandien R, Strachinaru M, Kardys I, Van Mieghem NM, Daemen J. Atrial fibrillation reduction by renal sympathetic denervation: 12 months' results of the AFFORD study. Clin Res Cardiol. 2019;108:634–642. doi: 10.1007/s00392-018-1391-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ott C, Mahfoud F, Schmid A, Toennes SW, Ewen S, Ditting T, Veelken R, Ukena C, Uder M, Bohm M, et al. Renal denervation preserves renal function in patients with chronic kidney disease and resistant hypertension. J Hypertens. 2015;33:1261–1266. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0000000000000556 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kresoja K‐P, Rommel K‐P, Fengler K, Von Roeder M, Besler C, Lücke C, Gutberlet M, Desch S, Thiele H, Böhm M, et al. Renal sympathetic denervation in patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Circ Heart Fail. 2021;14:e007421. doi: 10.1161/circheartfailure.120.007421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Polhemus DJ, Trivedi RK, Gao J, Li Z, Scarborough AL, Goodchild TT, Varner KJ, Xia H, Smart FW, Kapusta DR, et al. Renal sympathetic denervation protects the failing heart via inhibition of neprilysin activity in the kidney. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;70:2139–2153. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.08.056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Polhemus DJ, Gao J, Scarborough AL, Trivedi R, McDonough KH, Goodchild TT, Smart F, Kapusta DR, Lefer DJ. Radiofrequency renal denervation protects the ischemic heart via inhibition of GRK2 and increased nitric oxide signaling. Circ Res. 2016;119:470–480. doi: 10.1161/circresaha.115.308278 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Sharp TE, Polhemus DJ, Li Z, Spaletra P, Jenkins JS, Reilly JP, White CJ, Kapusta DR, Lefer DJ, Goodchild TT. Renal denervation prevents heart failure progression via inhibition of the renin‐angiotensin system. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;72:2609–2621. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.08.2186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Hillege HL, Nitsch D, Pfeffer MA, Swedberg K, McMurray JJV, Yusuf S, Granger CB, Michelson EL, ÖStergren J, Cornel JH, et al. Renal function as a predictor of outcome in a broad Spectrum of patients with heart failure. Circulation. 2006;113:671–678. doi: 10.1161/circulationaha.105.580506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Hamdani N, Franssen C, Lourenco A, Falcao‐Pires I, Fontoura D, Leite S, Plettig L, Lopez B, Ottenheijm CA, Becher PM, et al. Myocardial titin hypophosphorylation importantly contributes to heart failure with preserved ejection fraction in a rat metabolic risk model. Circ Heart Fail. 2013;6:1239–1249. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.113.000539 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Bilan VP, Salah EM, Bastacky S, Jones HB, Mayers RM, Zinker B, Poucher SM, Tofovic SP. Diabetic nephropathy and long‐term treatment effects of rosiglitazone and enalapril in obese ZSF1 rats. J Endocrinol. 2011;210:293–308. doi: 10.1530/joe-11-0122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Gao J, Kerut EK, Smart F, Katsurada A, Seth D, Navar LG, Kapusta DR. Sympathoinhibitory effect of radiofrequency renal denervation in spontaneously hypertensive rats with established hypertension. Am J Hypertens. 2016;29:hpw089–hp1401. doi: 10.1093/ajh/hpw089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Li Z, Organ CL, Kang J, Polhemus DJ, Trivedi RK, Sharp TE 3rd, Jenkins JS, Tao YX, Xian M, Lefer DJ. Hydrogen sulfide attenuates renin angiotensin and aldosterone pathological signaling to preserve kidney function and improve exercise tolerance in heart failure. JACC Basic Transl Sci. 2018;3:796–809. doi: 10.1016/j.jacbts.2018.08.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Trivedi RK, Polhemus DJ, Li Z, Yoo D, Koiwaya H, Scarborough A, Goodchild TT, Lefer DJ. Combined angiotensin receptor–neprilysin inhibitors improve cardiac and vascular function via increased no bioavailability in heart failure. J Am Heart Assoc. 2018;7:e008268. doi: 10.1161/jaha.117.008268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Lapenna KB, Li Z, Doiron JE, Sharp TE, Xia H, Moles K, Koul K, Wang JS, Polhemus DJ, Goodchild TT, et al. Combination sodium nitrite and hydralazine therapy attenuates heart failure with preserved ejection fraction severity in a “2‐hit” murine model. J Am Heart Assoc. 2023;12:e028480. doi: 10.1161/jaha.122.028480 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Li M, Galligan J, Wang D, Fink G. The effects of celiac ganglionectomy on sympathetic innervation to the splanchnic organs in the rat. Auton Neurosci. 2010;154:66–73. doi: 10.1016/j.autneu.2009.11.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Nayor M, Houstis NE, Namasivayam M, Rouvina J, Hardin C, Shah RV, Ho JE, Malhotra R, Lewis GD. Impaired exercise tolerance in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: quantification of multiorgan system reserve capacity. JACC Heart Fail. 2020;8:605–617. doi: 10.1016/j.jchf.2020.03.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Chirinos JA, Segers P, Hughes T, Townsend R. Large‐artery stiffness in health and disease: JACC state‐of‐the‐art review. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;74:1237–1263. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2019.07.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Wang M, Wenzheng H, Zhang M, Fang W, Zhai X, Guan S, Qu X. Long‐term renal sympathetic denervation ameliorates renal fibrosis and delays the onset of hypertension in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Am J Transl Res. 2018;10:4042–4053. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. van Dijk CG, Oosterhuis NR, Xu YJ, Brandt M, Paulus WJ, van Heerebeek L, Duncker DJ, Verhaar MC, Fontoura D, Lourenco AP, et al. Distinct endothelial cell responses in the heart and kidney microvasculature characterize the progression of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction in the obese ZSF1 rat with cardiorenal metabolic syndrome. Circ Heart Fail. 2016;9:e002760. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.115.002760 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Ichimura T, Bonventre JV, Bailly V, Wei H, Hession CA, Cate RL, Sanicola M. Kidney injury molecule‐1 (KIM‐1), a putative epithelial cell adhesion molecule containing a novel immunoglobulin domain, is up‐regulated in renal cells after injury. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:4135–4142. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.7.4135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Don BR, Kaysen G. Poor nutritional status and inflammation: serum albumin: relationship to inflammation and nutrition. Semin Dial. 2004;17:432–437. doi: 10.1111/j.0894-0959.2004.17603.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Mishra J, Ma Q, Prada A, Mitsnefes M, Zahedi K, Yang J, Barasch J, Devarajan P. Identification of neutrophil gelatinase‐associated lipocalin as a novel early urinary biomarker for ischemic renal injury. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2003;14:2534–2543. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000088027.54400.c6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Mesquita T, Lin YN, Ibrahim A. Chronic low‐grade inflammation in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Aging Cell. 2021;20:20. doi: 10.1111/acel.13453 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Zaldivia MTK, Rivera J, Hering D, Marusic P, Sata Y, Lim B, Eikelis N, Lee R, Lambert GW, Esler MD, et al. Renal denervation reduces monocyte activation and monocyte–platelet aggregate formation. Hypertension. 2017;69:323–331. doi: 10.1161/hypertensionaha.116.08373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Higashikuni Y, Liu W, Numata G, Tanaka K, Fukuda D, Tanaka Y, Hirata Y, Imamura T, Takimoto E, Komuro I, et al. NLRP3 Inflammasome activation through heart‐brain interaction initiates cardiac inflammation and hypertrophy during pressure overload. Circulation. 2023;147:338–355. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.122.060860 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Swanson KV, Deng M, Ting JP. The NLRP3 inflammasome: molecular activation and regulation to therapeutics. Nat Rev Immunol. 2019;19:477–489. doi: 10.1038/s41577-019-0165-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Shah SJ, Kitzman DW, Borlaug BA, Van Heerebeek L, Zile MR, Kass DA, Paulus WJ. Phenotype‐specific treatment of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Circulation. 2016;134:73–90. doi: 10.1161/circulationaha.116.021884 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. De Boer RA, De Keulenaer G, Bauersachs J, Brutsaert D, Cleland JG, Diez J, Du XJ, Ford P, Heinzel FR, Lipson KE, et al. Towards better definition, quantification and treatment of fibrosis in heart failure. A scientific roadmap by the Committee of Translational Research of the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur J Heart Fail. 2019;21:272–285. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.1406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Triposkiadis F, Karayannis G, Giamouzis G, Skoularigis J, Louridas G, Butler J. The sympathetic nervous system in heart failure physiology, pathophysiology, and clinical implications. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54:1747–1762. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.05.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Symplicity HTNI, Esler MD, Krum H, Sobotka PA, Schlaich MP, Schmieder RE, Bohm M. Renal sympathetic denervation in patients with treatment‐resistant hypertension (the Symplicity HTN‐2 trial): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2010;376:1903–1909. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)62039-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Kandzari DE, Bhatt DL, Sobotka PA, O'Neill WW, Esler M, Flack JM, Katzen BT, Leon MB, Massaro JM, Negoita M, et al. Catheter‐based renal denervation for resistant hypertension: rationale and design of the SYMPLICITY HTN‐3 trial. Clin Cardiol. 2012;35:528–535. doi: 10.1002/clc.22008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Griffin KA, Abu‐Naser M, Abu‐Amarah I, Picken M, Williamson GA, Bidani AK. Dynamic blood pressure load and nephropathy in the ZSF1 (fa/fa cp) model of type 2 diabetes. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2007;293:F1605–F1613. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00511.2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Nadruz W, Shah AM, Solomon SD. Diastolic dysfunction and hypertension. Med Clin North Am. 2017;101:7–17. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2016.08.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Veelken R, Schmieder RE. Renal denervation—implications for chronic kidney disease. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2014;10:305–313. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2014.59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Brouwers FP, de Boer RA, van der Harst P, Voors AA, Gansevoort RT, Bakker SJ, Hillege HL, van Veldhuisen DJ, van Gilst WH. Incidence and epidemiology of new onset heart failure with preserved vs. reduced ejection fraction in a community‐based cohort: 11‐year follow‐up of PREVEND. Eur Heart J. 2013;34:1424–1431. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/eht066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Murad K, Goff DC Jr, Morgan TM, Burke GL, Bartz TM, Kizer JR, Chaudhry SI, Gottdiener JS, Kitzman DW. Burden of comorbidities and functional and cognitive impairments in elderly patients at the initial diagnosis of heart failure and their impact on total mortality: the Cardiovascular Health Study. JACC Heart Fail. 2015;3:542–550. doi: 10.1016/j.jchf.2015.03.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Kirkman DL, Carbone S, Canada JM, Trankle C, Kadariya D, Buckley L, Billingsley H, Kidd JM, Van Tassell BW, Abbate A. The chronic kidney disease phenotype of HFpEF: unique cardiac characteristics. Am J Cardiol. 2021;142:143–145. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2020.12.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Shah SJ, Katz DH, Selvaraj S, Burke MA, Yancy CW, Gheorghiade M, Bonow RO, Huang C‐C, Deo RC. Phenomapping for novel classification of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Circulation. 2015;131:269–279. doi: 10.1161/circulationaha.114.010637 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Amann K, Rump LC, Simonaviciene A, Oberhauser V, Wessels S, Orth SR, Gross M‐L, Koch A, Bielenberg GW, Van Kats JP, et al. Effects of low dose sympathetic inhibition on glomerulosclerosis and albuminuria in subtotally nephrectomized rats. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2000;11:1469–1478. doi: 10.1681/asn.v1181469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Amann K, Koch A, Hofstetter J, Gross M‐L, Haas C, Orth SR, Ehmke H, Rump LC, Ritz E. Glomerulosclerosis and progression: effect of subantihypertensive doses of α and β blockers. Kidney Int. 2001;60:1309–1323. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2001.00936.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Strojek K, Grzeszczak W, Górska J, Leschinger MI, Ritz E. Lowering of microalbuminuria in diabetic patients by a sympathicoplegic agent: novel approach to prevent progression of diabetic nephropathy? J Am Soc Nephrol. 2001;12:602–605. doi: 10.1681/asn.v123602 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Hering D, Mahfoud F, Walton AS, Krum H, Lambert GW, Lambert EA, Sobotka PA, Böhm M, Cremers B, Esler MD, et al. Renal denervation in moderate to severe CKD. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012;23:1250–1257. doi: 10.1681/asn.2011111062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Hering D, Marusic P, Duval J, Sata Y, Head GA, Denton KM, Burrows S, Walton AS, Esler MD, Schlaich MP. Effect of renal denervation on kidney function in patients with chronic kidney disease. Int J Cardiol. 2017;232:93–97. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2017.01.047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Kaneko N, Kurata M, Yamamoto T, Morikawa S, Masumoto J. The role of interleukin‐1 in general pathology. Inflamm Regen. 2019;39:12. doi: 10.1186/s41232-019-0101-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Wang K, Qi Y, Gu R, Dai Q, Shan A, Li Z, Gong C, Chang L, Hao H, Duan J, et al. Renal denervation attenuates adverse remodeling and Intramyocardial inflammation in acute myocardial infarction with ischemia‐reperfusion injury. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2022;9:832014. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2022.832014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]