Key words: Balaenoptera physalus, Bolbosoma balaenae, fin whale, Mediterranean Sea, mitochondrial DNA cox1, phylogenetic analysis, ribosomal RNA 18S-28S

Abstract

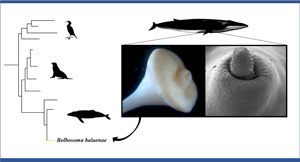

Post-mortem examination of a fin whale Balaenoptera physalus stranded in the Mediterranean Sea led to the finding of Bolbosoma balaenae for the first time in this basin. In this work, we describe new structural characteristics of this parasite using light microscopy and scanning electron microscopy approaches. Moreover, the molecular and phylogenetic data as inferred from both ribosomal RNA 18S-28S and the mitochondrial DNA cytochrome oxidase c subunit 1 (cox1) for adult specimens of B. balaenae are also reported for the first time. Details of the surface topography such as proboscis's hooks, trunked trunk spines of the prebulbar foretrunk, ultrastructure of proboscis's hooks and micropores of the tegument are shown. The 18S + 28S rRNA Bayesian tree (BI) as inferred from the phylogenetic analysis showed poorly resolved relationships among the species of Bolbosoma. In contrast, the combined 18S + 28S + mtDNA cox1 BI tree topology showed that the present sequences clustered with the species of Bolbosoma in a well-supported clade. The comparison of cox1 and 18S sequences revealed that the present specimens are conspecific with the cystacanths of B. balaenae previously collected in the euphausiid Nyctiphanes couchii from the North Eastern Atlantic Ocean. This study provided taxonomic, molecular and phylogenetic data that allow for a better characterization of this poor known parasite.

Introduction

Polymorphid acanthocephalans belonging to the genus Bolbosoma Porta, 1908 comprise 12 valid species (Amin, 2013). Of these, at least 10 (all described at the adult stage) have been reported in the intestinal tract of a range of oceanic whales and dolphins (Amin, 2013; Felix, 2013). The life cycle of Bolbosoma species has been not yet completely elucidated. However, it has been suggested that pelagic crustaceans (euphausiids and copepods) and fishes serve as intermediate and paratenic hosts, respectively (Measures, 1992; Hoberg et al., 1993; Dailey et al., 2000; Gregori et al., 2012). Marine mammals serve as definitive hosts; they become infected by ingestion of infected preys. In marine mammals, the species of Bolbosoma may cause different degrees of enteritis due to their ability to perforate mucosal surface for anchoring to the muscular layer (Parona, 1893; Porta, 1906; Dailey et al., 2000; Arizono et al., 2012; Kaito et al., 2019).

Bolbosoma balaenae (Gmelin, 1790) Porta, 1908 type species, has been described as Sipunculus lendix Phipps, 1774 in a sei whale Balenoptera borealis Lesson, 1828 from the Arctic waters. After its original description, B. balaenae was reported as sporadic finding in four oceanic odontocetes [i.e. the northern bottlenose whale Hyperoodon ampullatus Lacépède, 1804, spinner dolphins Stenella longirostris Gray, 1828, spotted dolphins S. attenuata Gray, 1846, and the pygmy sperm whale Kogia breviceps Golvan, 1961 (Gregori et al., 2012; Felix, 2013)] and, at least, in other five mysticetes species as regular hosts: the common minke whale B. acutorostrata Lacépéde, 1804, the fin whale B. physalus Linneus, 1758, the blue whale B. musculus Linneaus, 1758, the humpback whale Megaptera novaeangliae Borowski, 1781, and the grey whale Eschrichtius robustus Lilljeborg, 1861 (Golvan, 1961; Zdzitowiecki, 1991; Dailey et al., 2000; Felix, 2013). Regarding its geographical distribution, B. balaenae is known from Antarctic and Arctic waters, Southwest Atlantic Ocean, Tasman Sea and northern California coast to date (Zdzitowiecki, 1991; Dailey et al., 2000; Gregori et al., 2012; Felix, 2013).

The identification of Bolbosoma species is hardly based on the morphological characters alone, because of its similarities with congeneric species, and/or the old poor original description and redescriptions (Phipps, 1774; Van Cleave, 1953). Moreover, the presence of a wide variability of morphological characters of the anterior extremity in Bolbosoma spp. has been reported (Porta, 1906; Meyer, 1933; Van Cleave, 1953; Petrochenko, 1956; Zdzitowiecki, 1991). Likely, due to the old, opportunistic and scattered findings around its geographical range, B. balaenae remains a little known parasite: no microscopic images and molecular data exist for adult specimens of B. balaenae. Moreover, interest in Bolbosoma species increased recently by reason of their potential zoonotic role. At least, eight cases of human infection with Bolbosoma sp. and a case for B. capitatum causing clinical signs and intestinal lesions have been reported from Japan and related to the consumption of uncooked fish flesh (Arizono et al., 2012; Kaito et al., 2019).

Aims of the present study were to: (1) report the first occurrence of B. balaenae from a fin whale in the Mediterranean Sea; (2) describe new morphological characters of the species by using traditional microscopy and scanning electron microscopy (SEM); (3) carry out the molecular characterization of the species and to study its phylogenetic relationships with congener species and other polymorphid species maturing in marine hosts.

Materials and methods

Parasitological study

An immature female fin whale measuring 14.4 m in total length was found stranded in a cove of Capri Island (Tyrrhenian Sea) in southern Italy on 8 November 2020. At necropsy, approximately 1 m of duodenum showing the occurrence of acanthocephalans embedded into the intestinal wall or free in the lumen was cut and moved to the laboratory, where parasites were counted, rinsed in saline solution and preserved in ethanol 70% or frozen (−20°C) for morphological and molecular analyses, respectively. Morphological measurements were obtained from 20 relaxed adult specimens (10 females and 10 males) using a compound microscope and a stereomicroscope equipped with ZEN 3.1 imaging system (Zeiss). To study the proboscis and the pattern of hook spination, the bulb of acanthocephalans was dissected using scissors and tweezers under the stereomicroscope, and proboscis and neck were displayed and clarified in Amman's lactophenol. To study the testes and cement glands, the male specimens were dissected and organs were displayed and measured under the stereomicroscope. Acanthocephalans were morphologically classified following the identification keys proposed by Meyer (1933), Van Cleave (1953) and Petrochenko (1956). Copromicroscopic examination was performed on a sample of feces obtained from the rectum and a standard flotation method with Sheather's sucrose solution (specific gravity 1.27) was used to detect and measure parasite eggs.

For SEM, the anterior portion of five acanthocephalan specimens was also fixed overnight in 2.5% glutaraldehyde, then transferred to 40% ethanol (10 min), rinsed in 0.1 M cacodylate buffer, postfixed in 1% OsO4 for 2 h, and dehydrated in ethanol series, critical point dried and sputter-coated with platinum. Observations were made using a JEOL JSM 6700F scanning electron microscope operating at 5.0 kV (JEOL, Basiglio, Italy).

Molecular and phylogenetic analyses

Caudal portion of 10 specimens of B. balaenae (comprising three specimens studied for SEM) was used for molecular analyses. Total genomic DNA from ~2 mg of each specimen was isolated using the Quick-gDNA Miniprep Kit (ZYMO RESEARCH), following the standard manufacturer-recommended protocol.

Two regions (18S and 28S) of the nuclear ribosomal RNA (rRNA) and a fragment of the mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA cox1) were amplified. The near-complete small subunit (ssrDNA, 18S) (~1800 bp) was amplified using the forward 5′-AGATTAAGCCATGCATGCGT-3′ and reverse 5′-GCAGGTTCACCTACGGAAA-3′ primers (Garey et al., 1996; García-Varela et al., 2002, 2013). The near-complete large subunit (lsrDNA, 28S) (~2900 bp) was amplified using two overlapping PCR fragments of 1400–1500 bp. Primers for the amplicon 1 were forward 5′-CAAGTACCGTGAGGGAAAGTTGC-3′ and reverse 5′-CTTCTCCAAC(T/G)TCAGTCTTCAA-3′; primers for the amplicon 2 were forward 5′-CTAAGGAGTGTGTAACAACTCACC and reverse 5′-CTTCGCAATGATAGGAAGAGCC-3′ (García-Varela and Nadler, 2005). A partial (~700 bp) sequence of the mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase subunit 1 (cox1) was amplified using the primers LCO1490 (5-GGTCAACAAATCATAAAGATATTGG-3) and HCO2198 (5-TAAACTTCAGGGTGACCAAAAAATCA-3) (Folmer et al., 1994). Polymerase chain reactions (PCRs) were performed in a 25 μL volume containing 0.6 μL of each primer 10 mm, 2 μL of MgCl2 25 mm (Promega), 5 μL of 5× buffer (Promega), 0.6 μL of dNTPs 10 mm (Promega), 0.2 μL of Go-Taq Polymerase (5 U μL−1) (Promega) and 2 μL of total DNA. PCR temperature conditions for rRNA amplifications were the following: 95°C for 3 min (initial denaturation), followed by 40 cycles at 94°C for 1 min (denaturation), 52–56°C (optimized for the 18S and 28S amplification, respectively) for 1 min (annealing), 72°C for 1 min (extension) and followed by post-amplification at 72°C for 7 min. PCR cycling parameters for the mtDNA cox1 amplifications were the following: 95°C for 5 min (initial denaturation), followed by 40 cycles at 95°C for 1 min (denaturation), 45°C for 1 min (annealing), 72°C for 1 min (extension) and followed by post-amplification at 72°C for 7 min.

PCR amplicons were purified using the AMPure XP kit (Beckman Coulter) following the standard manufacturer-recommended protocol and Sanger sequenced from both strands, using the same primers, through an Automated Capillary Electrophoresis Sequencer 3730 DNA Analyzer (Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad), using the BigDye® Terminator v3.1 Cycle Sequencing Kit (Life Technologies). Contiguous sequences were assembled and edited using MEGAX v. 11 (Kumar et al., 2018). Sequence identity was checked using the Nucleotide Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLASTn) (Morgulis et al., 2008).

The 18S, 28S and cox1 datasets were aligned with all the sequences of species of genera Andracantha, Bolbosoma and Corynosoma (Polymorphidae) available in GenBank, using ClustalX v. 2.1 (Larkin et al., 2007), as described in García-Varela et al. (2013) (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Species, stage (L: larva; A: adult), host, locality and accession numbers of sequences of cox1, 28S and 18S of genera Andracantha, Corynosoma and Bolbosoma included in the Bayesian inference shown in Figs 3 and 4

| Species | Stage | Host | Locality | cox1 | 28S | 18S | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Andracantha gravida | A | Phalacrocorax auritus | Yucatan, Mexico | EU267822 | EU267814 | EU267802 | García-Varela et al. (2009) |

| Andracantha leucocarboi | A | Leucocarbo chalconotus | New Zealand | MF527025 | MF401623 | – | Presswell et al. (2018) |

| Andracantha sigma | A | Eudyptula minor | New Zealand | MF527034 | MF401624 | – | Presswell et al. (2018) |

| Andracantha phalacrocoracis | A | Phalacrocorax pelagicus | Hokkaido, Japan | LC465396 | LC461973 | – | Sasaki et al. (2019) |

| Corynosoma australe | A | Phocarctos hookeri | New Zealand | JX442191 | JX442180 | JX442168 | García-Varela et al. (2013) |

| Corynosoma hannae | L | Peltorhamphus novaezeelandiae | New Zealand | KX957726 | – | – | Hernandez-Orts et al. (2016) |

| Corynosoma validum | A | Callorhinus ursinus | St. Paul Island, Alaska | JX442193 | JX442182 | JX442170 | García-Varela et al. (2013) |

| Corynosoma villosum | L | Pleurogrammus azonus | Hokkaido, Japan | LC465336 | LC461969 | – | Sasaki et al. (2019) |

| Corynosoma obtuscens | A | Callorhinus ursinus | St. Paul Island, Alaska | JX442192 | JX442181 | JX442169 | García-Varela et al. (2013) |

| Corynosoma enhydri | A | Enhydra lutris | Monterey Bay, California | DQ089719 | AY829107 | AF001837 | García-Varela and Nadler (2006) |

| Corynosoma magdaleni | A | Phoca hispida saimensis | Lake Saimaa, Finland | EF467872 | EU267815 | EU267803 | García-Varela et al. (2009) |

| Corynosoma semerme | L | Osmerus dentex | Hokkaido, Japan | LC465392 | LC461963 | – | Sasaki et al. (2019) |

| Corynosoma strumosum | A | Phoca vitulina | Monterey Bay, California | EF467870 | EU267816 | EU267804 | García-Varela et al. (2009) |

| Bolbosoma balaenae* | L A |

Nyctiphanes couchii Balaenoptera physalus |

Spain Capri Island, Italy |

JQ061132 MZ047272–MZ047281 |

– MZ047231–MZ047240 |

JQ040306 MZ047218–MZ047227 |

Gregori et al. (2012) Present study |

| Bolbosoma caenoforme | A | Salvelinus malma | Tauj Bay, Russia | KF156891 | – | KF156879 | Malyarchuk et al. (2014) |

| Bolbosoma sp. | L | Callorhinus ursinus | St. Paul Island, Alaska | JX442190 | JX442179 | JX442167 | García-Varela et al. (2013) |

| Bolbosoma turbinella | A | Eschrichtius robustus | Monterey Bay, California | JX442189 | JX442178 | JX442166 | García-Varela et al. (2013) |

| Bolbosoma vasculosum | – | Lepturacanthus savala | Indonesia | – | – | JX014225 | Verweyen et al. (2011) |

| Hexaglandula corynosoma | A | Nyctanassa violacea | La Tovara, Mexico | EU189488 | EU267817 | EU267808 | Guillén-Hernández et al. (2008), García-Varela et al. (2009) |

| Polymorphus brevis | A | Nycticorax nycticorax | Michoacan, Mexico | DQ089717 | AY829105 | JX442171 | García-Varela and Nadler (2006), García-Varela et al. (2013) |

The cox1 sequence of Bolbosoma balaenae of Gregori et al. (2012) was erroneously deposited in GenBank under the name Rhadinorhynchus pristis.

–, data not reported.

Sequences were combined (18S + 28S and 18S + 28S + cox1), using SequenceMatrix (Vaidya et al., 2011), while the best partition schemes and best-fit models of substitution were identified using Partition Finder (Lanfear et al., 2012) with the Akaike information criterion (AIC; Akaike, 1973). Sequences obtained in the present study were deposited in GenBank under the accession numbers MZ047218-MZ047227 (18S), MZ047231-MZ047240 (28S) and MZ047272-MZ047281 (cox1).

Phylogenetic trees of the 18S + 28S and 18S + 28S + cox1 gene loci were constructed using the Bayesian inference (BI) with MrBayes, v. 3.2.7 (Ronquist and Huelsenbeck, 2003). The Bayesian posterior probability analysis was performed using the MCMC algorithm, with four chains, 0.2 as the temperature of heated chains, 5 000 000 generations, with a subsampling frequency of 500 and a burn-in fraction of 0.25. Posterior probabilities were estimated and used to assess support for each branch. Values with a 0.90 posterior probability were considered well-supported. Trees were drawn using FigTree v. 1.3.1 (Rambaut, 2009). The phylogenetic trees were rooted using Hexaglandula corynosoma (Travassos, 1915) Petrochenko, 1958 and Polymorphus brevis (Van Cleave, 1916) Travassos, 1926 as outgroups, according to García-Varela et al. (2021). Genetic distances were computed using the Kimura 2-Parameters (K2P) model (Kimura, 1980) with 1000 bootstrap re-samplings, using MEGA Software, version 7.0 (Kumar et al., 2018).

Results

Parasitological study

A total of 142 specimens of acanthocephalans yellowish in colour were collected from the examined tract of the duodenum. Most specimens were firmly embedded with their proboscis and cephalic bulb within the muscular layer of the intestinal wall, having perforated the mucosal and submucosal surfaces, and few specimens were found free in the intestinal lumen. Gross changes consisted of oedematous thickening of the duodenal wall with the occurrence of 5–10 mm large, green-dark multifocal nodular lesions scattered throughout the muscular layer.

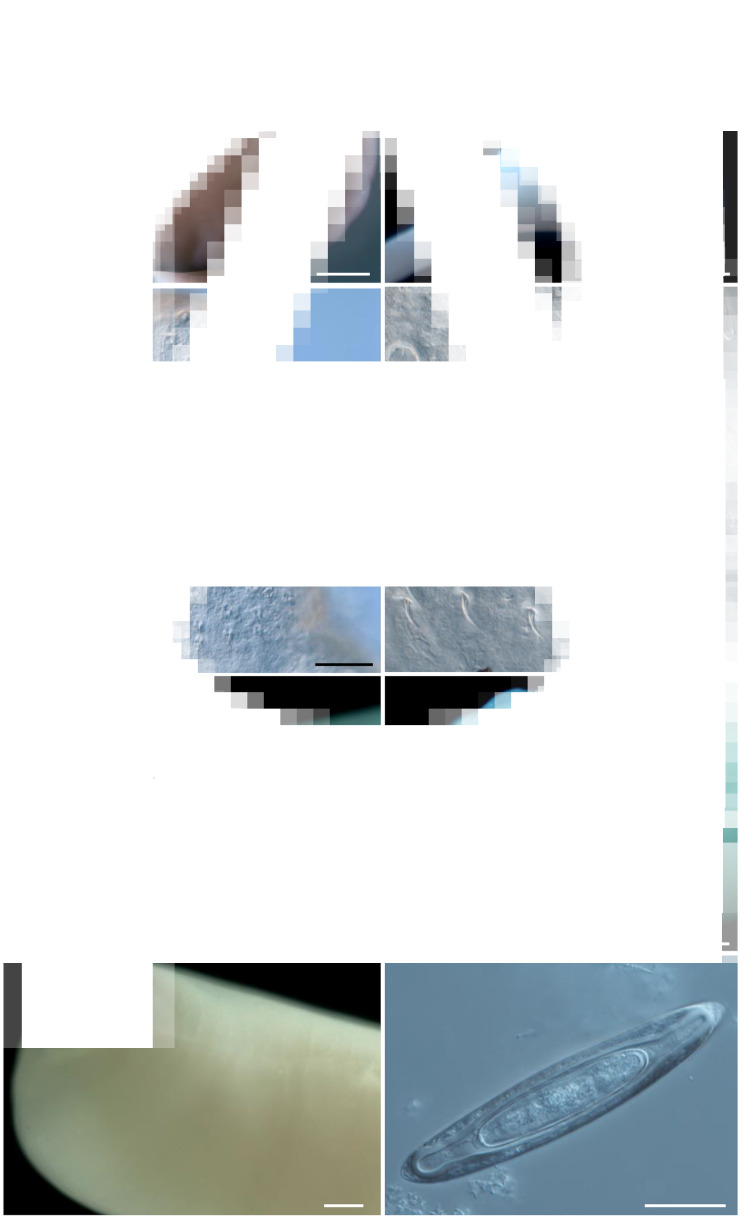

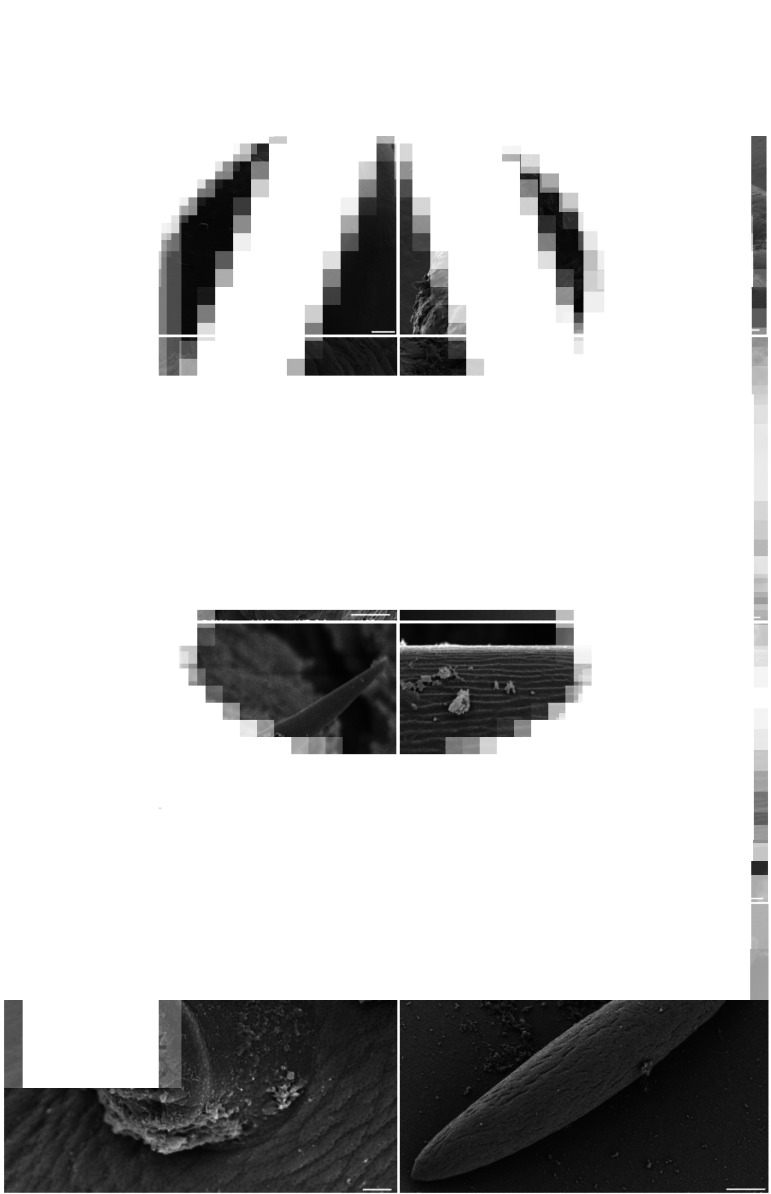

Based on the morphological characters, all the acanthocephalans were identified as B. balaenae (Figs 1 and 2). Specimens of B. balaenae differ from all other species of Bolbosoma having unarmed bulb and proboscis armed with 24 rows of hooks with 7–8 hooks per row. Proboscis was cylindrical showing hooks of different sizes and morphology, first 5 with roots and last 2–3 with rootless (Fig. 1C and D; Table 2). A field of trunked trunk spines restricted to the prebulbar foretrunk variable in number (from 5 to 9 irregular circles) was distinguished by SEM study alone (Fig. 2). Observation of the detailed surface morphology allowed also to highlight the features and unique ultrastructure of proboscis's hooks showing shallow longitudinal grooves, as well as the micropores on the tegument of the foretrunk (Fig. 2). Most important diagnostic morphological measurements of B. balaenae and their mature eggs observed at the copromicroscopic analysis (Fig. 1H) are listed in Table 2. Voucher specimens have been deposited at the Zoological Collection of the Stazione Zoologica Anton Dohrn in Naples (Italy) with the following accession number: SZN-ACA0001.

Fig. 1.

Microscopic features of Bolbosoma balaenae from the intestine of the fin whale from the southern Italy. Anterior extremity frontal (A, female) and lateral (B, male) views (scale bar: 1000 μm). Proboscis (C, scale bar: 50 μm) and particular of proboscis basal hooks (D, scale bar: 100 μm). Bursa lateral (E, scale bar: 1000 μm) and ventral (F, scale bar: 500 μm) views. Genital pore of female in lateral view (G, scale bar: 500 μm). Mature egg (H, scale bar: 20 μm).

Fig. 2.

Scanning electron micrographs of Bolbosoma balaenae from the intestine of the fin whale from the southern Italy. General view of prebulb and proboscis of a female (A, scale bar: 100 μm). Note the circles of trunked trunk spines on the prebulb. Lateral (B) and apical (C) views of proboscis and neck (scale bar: 100 μm) of a male. High magnification of an apical (D, scale bar: 10 μm) and a basal (E, scale bar: 1 μm) proboscis hook. High magnification of an apical proboscis hook surface (F, scale bar: 1 μm) showing longitudinal grooves. A high magnification of a truncated trunk spine (G, scale bar: 1 μm). Note the body wall micropores on the tegument of the prebulb. Mature egg (H, scale bar: 10 μm).

Table 2.

Measurements (mean value ± standard deviation with range in parenthesis) of main diagnostic characters in Bolbosoma balaenae found in a fin whale from southern Italy

| Characters | Male (n = 10) | Females (n = 10) |

|---|---|---|

| Total length (cm) | 11.3 ± 0.91 (10.1–12.8) | 13.6 ± 0.75 (12.8–14.5) |

| Width at middle of body (mm) | 2.4 ± 0.06 (2.4–2.5) | 4 ± 0.94 (3–5.1) |

| Bulb length (mm) | 5.2 ± 0.30 (5.1–5.6) | 6.1 ± 0.82 (5–7.1) |

| Bulb width (mm) | 5.1 ± 0.23 (4.9–5.4) | 5.9 ± 0.61 (4.9–6.6) |

| Prebulb length (mm) | 1 ± 0.18 (0.8–1.2) | 1 ± 0.21 (0.8–1.3) |

| Prebulb width at base (mm) | 1.4 ± 0.26 (1.1–1.5) | 1.8 ± 0.25 (1.6–2.1) |

| Proboscis length | 564.6 ± 10.44 (598.4–613.1) | 611 ± 38.05 (561–648.7) |

| Proboscis width at basal hook | 499.9 ± 3.51 (496.1–503.1) | 483.9 ± 67.65 (425.5–572.9) |

| Neck length | 573 ± 48.44 (518.4–610.8) | 517.8 ± 61.04 (454–595.4) |

| Lemnisci length | 4005.4 ± 219.02 (3828.4–4250.7) | 3157.2 ± 873.27 (2211.7–4369.8) |

| Proboscis hook 1 length | 66.8 ± 15.58 (54.5–88.6) | 51.8 ± 3.36 (46.2–55.1) |

| Proboscis hook 1 width | 10.5 ± 1.72 (8.2–12.1) | 11.7 ± 3.48 (5.7–16.6) |

| Proboscis hook 2 length | 61.8 ± 7.33 (56.4–74.4) | 61.6 ± 9.46 (79.2–53.6) |

| Proboscis hook 2 width | 13.3 ± 2.40 (10.2–16.8) | 14.4 ± 1.95 (11.4–18.2) |

| Proboscis hook 3 length | 63.2 ± 4.40 (59.4–69.1) | 57.72 ± 10.68 (40.01–87.99) |

| Proboscis hook 3 width | 14.55 ± 0.96 (13.19–15.49) | 13.7 ± 3.13 (11.5–20.9) |

| Proboscis hook 4 length | 60.6 ± 3.53 (56.8–65.7) | 51.1 ± 7.65 (39.2–67.1) |

| Proboscis hook 4 width | 16.1 ± 2.05 (14.2–18.7) | 14.5 ± 3.39 (11.3–20.9) |

| Proboscis hook 5 length | 67 ± 4.35 (61.8–73.9) | 51.3 ± 8.97 (40.2–70.8) |

| Proboscis hook 5 width | 19.2 ± 1.42 (16.7–20.9) | 14.9 ± 3.35 (9.5–20.7) |

| Proboscis hook 6 length | 58.3 ± 11.71 (44.4–70.1) | 57.7 ± 12.41 (40.3–81.7) |

| Proboscis hook 6 width | 15.5 ± 4.22 (11.2–19.8) | 16.7 ± 3.78 (13.9–24.7) |

| Proboscis hook 7 length | 37.6 ± 1.12 (36.8–39.5) | 35.3 ± 7.65 (21.4–55.5) |

| Proboscis hook 7 width | 8.2 ± 0.97 (7.1–9) | 9.4 ± 2.56 (5.7–11.5) |

| Proboscis hook 8 length | 28.5 ± 3.96 (24.7–35.3) | 34.1 ± 7.41 (22.8–46.8) |

| Proboscis hook 8 width | 4.8 ± 1.37 (3.8–7.5) | 7.1 ± 1.48 (4.9–11.2) |

| Anterior testis length | 3621.5 ± 350.1 (3044.5–3949.4) | – |

| Anterior testis width | 1308.5 ± 143.13 (1065.3–1406.6) | – |

| Posterior testis length | 3479.5 ± 348.46 (2866.5–3712.6) | – |

| Posterior testis width | 1431.6 ± 105.53 (1275–1441) | – |

| Cement glands length (cm) | 5 ± 0.97 (4–6.5) | – |

| Bursa diameter | 2260.2 ± 0.18 (2020.1–2480.3) | – |

| Egg length | – | 140.6 ± 6.74 (132.1–149.5) |

| Egg width | – | 31.2 ± 1.78 (27.8–33.9) |

Measurements are in micrometres except when stated. Ten elements for each character were measured except for the bursa for which the measurements were obtained from four specimens with everted bursa.

Molecular and phylogenetic analyses

The BLASTn analysis of the 18S sequences retrieved a similarity between 99.70 and 100% with sequences from GenBank belonging to B. balaenae (JQ040306), Bolbosoma sp. (JX442167) and B. turbinella (JX442166). The BLASTn analysis of 28S sequences produced a percentage of similarity of 99.60% with Bolbosoma sp. (JX442179) from the northern fur seal Callorhinus ursinus Linnaeus, 1758 available in GenBank. The mtDNA cox1 sequences shared a similarity of ~99% with B. balaenae (JQ061132) from the euphausiid Nyctiphanes couchii (Bell, 1853), erroneously deposited in GenBank under the name Rhadinorhynchus pristis by Gregori et al. (2012).

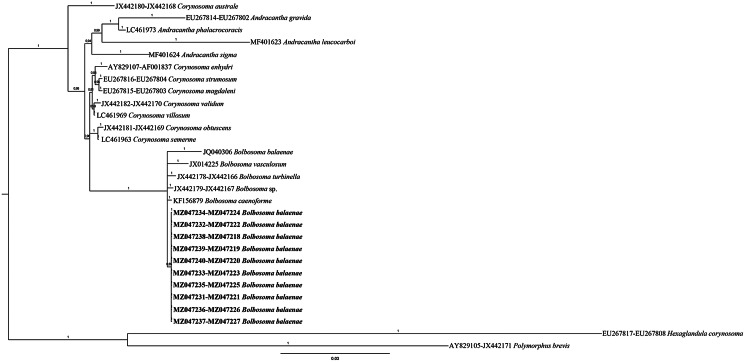

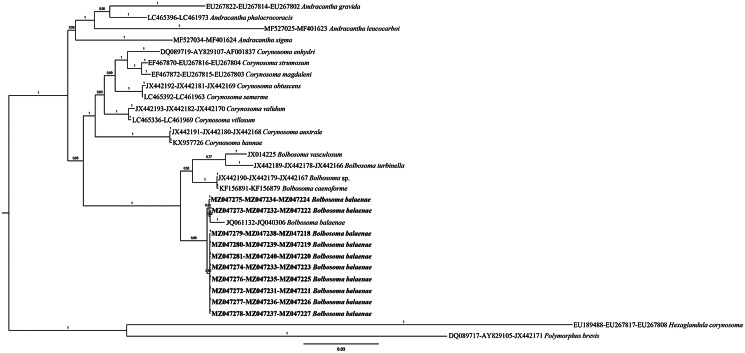

The combined 18S + 28S phylogenetic Bayesian tree, including sequences of species within the three genera (Andracantha, Bolbosoma and Corynosoma) of the family Polymorphidae, showed poorly resolved relationships, especially within the genus Bolbosoma (Fig. 3). In contrast, the concatenated BI tree topology of the three gene loci 18S + 28S + cox1 showed that the obtained sequences from Bolbosoma here analysed clustered in a highly supported clade (100% of probability value) (Fig. 4). This clade, including also the sequences available in GenBank of the polymorphid cystacanths obtained from N. couchii (JQ061132, JQ040306), resulted to be clearly distinct from the other species of the genus Bolbosoma, whose sequences at those analysed gene loci were available in GenBank (Fig. 4). The distance values between the present sequences of B. balaenae and the sequences of cystacanths from N. couchii were: K2P = 0.017 ± 0.005 at the mtDNA cox1 and K2P = 0.004 ± 0.002 at the 18S rRNA (present sequences vs JQ040304-JQ040306). While, at the interspecific level, the mtDNA cox1 sequences of B. balaenae showed a higher value of differentiation (K2P = 0.165 ± 0.020) with respect to the closest sequence of B. caenoforme (KF156891). No sequences of B. caenoforme were available in GenBank for the 28S gene locus.

Fig. 3.

Phylogenetic concatenated tree from Bayesian inference based on 18S and 28S sequences of B. balaenae obtained in the present study, with respect to the sequences of species of genera Andracantha, Bolbosoma and Corynosoma, at the same gene loci available in GenBank. The analysis was performed by MrBayes, v. 3.2.7, using the GTR + G substitution model. Hexaglandula corynosoma and Polymorphus brevis were used as outgroup. The sequences obtained in this study are in bold.

Fig. 4.

Phylogenetic concatenated tree from Bayesian inference based on 18S + 28S + cox1 sequences of B. balaenae obtained in the present study, with respect to the sequences of species of genera Andracantha, Bolbosoma and Corynosoma, at the same gene loci available in GenBank. The analysis was performed by MrBayes, v. 3.2.7, using the GTR + G substitution model. Hexaglandula corynosoma and Polymorphus brevis were used as outgroup. The sequences obtained in this study are in bold.

Discussion

Previous reports of Bolbosoma species from the marine mammals in the Mediterranean Sea are limited to B. capitatum (Parona, 1893; Porta, 1906) in a long-finned pilot whale Globicephala melas Traill, 1809, and B. vasculosum (only immature specimens in a common dolphin Delphinus delphis; Van Cleave, 1953). Recently, a single specimen of Bolbosoma sp. later identified as B. capitatum was collected from 1 of 7 fin whales (Marcer et al., 2019).

These uncommon records suggest that Bolbosoma spp. are only occasional in the Mediterranean basin, likely transported from migrating individuals from the Atlantic Ocean. Helminth parasites have been extensively used as biological tags of marine vertebrates in host population structure studies. Recently, we used anisakid nematodes of the dwarf sperm whale Kogia sima Owen, 1866 and trypanorhynch cestodes of the sunfish Mola mola Linnaeus, 1758 to suggest the possible existence of a resident population or migration routes of their hosts, respectively (Santoro et al., 2018, 2020). The fin whale is the most abundant mysticete in the Mediterranean Sea (Panigada and Notarbartolo di Sciara, 2012) with the occurrence of both resident and migrating populations confirmed by genetic studies (Bérubé et al., 1998). For the migrating fin whale populations, a general movement trend towards the northeast North Atlantic in spring-summer and towards the Mediterranean during fall-winter has been suggested (Geijer et al., 2016). The present finding of a parasite known from geographical areas far from the Mediterranean basin seems to suggest that the present fin whale would be a migrating and not a resident individual.

Regarding the source of infection, Bolbosoma cystacanths have been found in fish [Scombridae, Scorpaenidae, Carangidae, Trichiuridae, Gempylidae, Salmonidae, Berycidae, Lophotidae, Gadidae and Belonidae (www.nhm.ac.uk/research-curation/research/projects/host-parasites/index.Html)] and crustaceans (euphausiids and copepods) (Measures, 1992; Hoberg et al., 1993; Dailey et al., 2000; Gregori et al., 2012). Recently, Gregori et al. (2012) found cystacanths identified as B. balaenae in 0.04% of the euphausiid N. couchii specimens examined from the Atlantic Galician waters (Spain). The source of the infection of the present fin whale with B. balaenae remains unknown; it could be plausible that the fin whale acquired the infection by ingestion of infected crustaceans and/or fish during the migration from the Atlantic to the Mediterranean Sea waters.

Most of the morphological characters of adult specimens of B. balaenae were not detailed by earlier authors so that comparisons with the present material are limited. For instance, males/females combined total length were 80–160 mm in the original description (reported in Porta, 1906) and 190–205 mm in Van Cleave (1953), while data on the measurements of the hook proboscis are missed as well as the measurements of most characters listed in Table 2. Regarding the number of rows of hooks and the number of hooks per longitudinal row of the proboscis, the present data correspond to previous data (Meyer, 1933; Van Cleave, 1953; Zdzitowiecki, 1991). In contrast, previous descriptions of prebulbar foretrunk of B. balaenae using optical microscopy alone reported apparently contrasting data on the presence/absence and numbers of circles of spines: 6 circles in Meyer (1933), 0 in Van Cleave (1953) and up to 10 circles of spines in Zdzitowiecki (1991). Moreover, in cystacanths morphologically identified as B. balaenae found encapsulated in the cephalothorax of N. couchii, Gregori et al. (2012) described a single field of trunk spines restricted to the foretrunk and composed of 4–6 irregular circles of small spines adjacent to the neck. Finally, Bennett et al. (2021) found seven circles of spines in an immature individual identified as B. balaenae in a blue penguin Eudyptula novaehollandiae Stephens, 1826 from New Zealand. The present observation regarding the occurrence of trunked trunk spines on the prebulbar foretrunk of adult individuals of B. balaenae differentiated by SEM alone supports the hypothesis of Van Cleave (1953), according to which the trunk spines show wide variability in number, and these may be lost along the parasite life span.

The species of the genus Corynosoma (a polymorphid genus very close to Bolbosoma) use the flattened, spiny foretrunk as a very efficient device that assists the proboscis to adhere to the gut wall but is also able to put the ventral hindtrunk into contact with the substratum, reinforcing attachment (Aznar et al., 2006, 2018). Aznar et al. (2016) reported that cystacanths and adults of Corynosoma cetaceum (a parasite of the stomach of dolphins) exhibited a wide range of fold spine reduction and variability, suggesting that they are generated before the adult stage, when spines are functional for attachment to the stomach wall of its definitive host. This assumes that the foretrunk spines should not be regarded as a diagnostic taxonomic character within the genus Corynosoma (Aznar et al., 2016) as well as in the genus Bolbosoma.

Observation of the detailed surface morphology of the present material using SEM allowed also to highlight the features and unique ultrastructure of proboscis's hooks, showing shallow longitudinal grooves, as well as the micropores of the tegument of foretrunk supposed to be a specialized system implicated in absorptive function (Heckmann et al., 2013). According to Heckmann et al. (2013) micropores on the tegument showing different sizes and shapes have been described in at least 16 acanthocephalan species. The different ultrastructural pattern of proboscis's hooks has been studied as a potential diagnostic feature to differentiate among species of Centrorhynchus and species of related genera, but no conclusive results were obtained (Amin et al., 2015, 2018). No mention is done on both ultrastructure of proboscis's hooks and epidermal micropores from previously published papers reporting SEM observation of B. capitatum, B. vasculosum and B. turbinella (Amin and Margolis, 1998; Costa et al., 2000; da Fonseca et al., 2019). Future studies comparing the ultrastructure features among Bolbosoma species could reveal if the present findings might yield important information to help identify this species.

The combination of morphological and molecular studies is considered a very useful approach to resolve taxonomic ambiguities within the genera of Polymorphidae (García-Varela et al., 2013). Unfortunately, out of the 12 species of Bolbosoma considered as valid, DNA sequences for only six of those are available in GenBank. Moreover, from the current 23 Bolbosoma sequences available, only four are from adult parasites obtained from their definitive hosts: three of them are belonging to B. turbinella (18S, 28S and cox1) from the grey whale, and one to B. nipponicum (ITS1/ITS2 region) from the common minke whale. Before the present study, four sequences of B. balaenae (including three of 18S and one of cox1) were available in GenBank, all from the same cystacanths (Gregori et al., 2012). However, the sequence of cox1 (JQ040303) deposited in GenBank as B. balaenae belongs to R. pristis (an acanthocephalan of Rhadinorhynchidae family), while the sequence deposited as R. pristis (JQ061132.1) belongs to B. balaenae. Likely an error occurred by Gregori et al. (2012) at the moment of sequence submission and the names of sequences used in the mentioned study were inverted.

In the present study, the BI phylogenetic analysis based on the combined (18S + 28S) rRNA data produced poorly resolved clades among species of Andracantha, Corynosoma and Bolbosoma. Moreover, from the obtained results, it is clear that the gene locus 18S is not diagnostic for the genetic identification of Bolbosoma species. While the phylogenetic tree herein inferred from combining the sequences obtained at the three gene loci (18S + 28S + cox1) from adult individuals of B. balaenae and those sequences at the same gene loci available in GenBank has shown that the species of Andracantha, Bolbosoma and Corynosoma are comprising, respectively, in three distinct and well-supported major clades (Fig. 4). These findings are in agreement with previous phylogenetic elaborations provided by García-Varela et al. (2013) and Presswell et al. (2018). In addition, the combined BI inferred from 18S + 28S + cox1 gene sequences supports, with high probability values, that the so far genetically characterized species of Bolbosoma, including B. balenae, represent distinct phylogenetic lineages.

The phylogenetic pattern obtained is congruent with the life cycles of members of these three genera (i.e. Andracantha, Bolbosoma and Corynosoma), which involve teleost marine fish as paratenic hosts. It has been suggested that the shared ecological feeding behaviour among different definitive hosts could have provided many opportunities for co-speciation and host-switching events and could have accompanied the evolutionary pathways of these polymorphid species (Dailey et al., 2000; Aznar et al., 2006; García-Varela et al., 2013, 2021; Presswell et al., 2018).

Finally, the only report of pathological changes associated with Acanthocephala of the genus Bolbosoma in a Mediterranean cetacean was reported by Parona (1893) who described a severe intestinal parasitosis caused by B. capitatum in a long-finned pilot whale. Parona (1893) reported the occurrence of at least 25 305 individual parasites strictly embedded in the muscular layer along the first 12 m of the intestine. Dailey et al. (2000) described gross multifocal transmural abscesses encapsulating proboscis of B. balaenae along the first 7.5 m of the ileum in a juvenile grey whale. The present results agree with the gross pathological changes described by Parona (1893) and Dailey et al. (2000) and confirm that B. balaenae may cause enteritis also in the fin whale.

Acknowledgements

Necropsy of the fin whale was performed by the Cetacean Stranding Emergency Response Team (Padua University, Italy), in collaboration with veterinarians of the Istituto Zooprofilattico Sperimentale del Mezzogiorno (Portici, Naples, Italy).

Financial support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethical standards

Not applicable.

Conflict of interest

None.

References

- Akaike H (1973) Information theory and an extension of the maximum likelihood principle. In Petrov T and Caski F (eds), Proceeding of the Second International Symposium on Information Theory. Budapest: Akademiai Kiado, pp. 267–281. [Google Scholar]

- Amin OM (2013) Classification of the Acanthocephala. Folia Parasitologica 4, 273–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amin OM and Margolis L (1998) Redescription of Bolbosoma capitatum (Acanthocephala: Polymorphidae) from false killer whale off Vancouver Island, with taxonomic reconsideration of the species and synonymy of B. physeteris. Journal of Helminthological Society of Washington 65, 179–188. [Google Scholar]

- Amin OM, Heckmann RA, Wilson E, Keele B and Khan A (2015) The description of Centrorhynchus globirostris n. sp. (Acanthocephala: Centrorhynchidae) from the pheasant crow, Centropus sinensis (Stephens) in Pakistan, with gene sequence analysis and emendation of the family diagnosis. Parasitology Research 114, 2291–2299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amin OM, Heckmann RA and Bannai MA (2018) Cavisoma magnum (Cavisomidae), a unique Pacific acanthocephalan redescribed from an unusual host, Mugil cephalus (Mugilidae), in the Arabian Gulf, with notes on histopathology and metal analysis. Parasite 25, 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arizono N, Kuramochi T and Kagei N (2012) Molecular and histological identification of the acanthocephalan Bolbosoma cf. capitatum from the human small intestine. Parasitology International 61, 715–718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aznar FJ, Pérez-Ponce de León G and Raga JA (2006) Status of Corynosoma (Acanthocephala: Polymorphidae) based on anatomical, ecological, and phylogenetic evidence, with the erection of Pseudocorynosoma n. gen. Journal of Parasitology 92, 548–564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aznar FJ, Crespo EA, Raga JA and Hernández-Orts JS (2016) Trunk spines in cystacanths and adults of Corynosoma spp. (Acanthocephala): Corynosoma cetaceum as an exceptional case of phenotypic variability. Zoomorphology 135, 19. [Google Scholar]

- Aznar FJ, Hernández-Orts JS and Raga JA (2018) Morphology, performance and attachment function in Corynosoma spp. (Acanthocephala). Parasites and Vectors 11, 633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett J, McPherson O and Presswell B (2021) Gastrointestinal helminths of little blue penguins, Eudyptula novaehollandiae (Stephens), from Otago, New Zealand. Parasitology International 80, 102185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bérubé M, Aguilar A, Dendanto D, Larsen F, Notarbartolo di Sciara G, Sears R, Sigurjonsson J, Urban RJ and Palsboll PJ (1998) Population genetic structure of North Atlantic, Mediterranean Sea and Sea of Cortez fin whales, Balaenoptera physalus (Linnaeus 1758): analysis of mitochondrial and nuclear loci. Molecular Ecology 7, 585–599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa G, Chubb J and Veltkamp C (2000) Cystacanths of Bolbosoma vasculosum in the black scabbard fish Aphanopus carbo, oceanic horse mackerel Trachurus picturatus and common dolphin Delphinus delphis from Madeira, Portugal. Journal of Helminthology 74, 113–120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- da Fonseca MCG, Knoff M, Lopes Torres EJ, Di Azvedo MIN, Correa Gomes D, de Sao Clemente S and Iniguez AM (2019) Acanthocephalan parasites of the flounder species Paralichthys isosceles, Paralichthys patagonicus and Xystreurys rasile from Brazil. Revista Brasileira de Parasitologia Veterinaria 28, 346–359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dailey MD, Gullant FMD, Lowenstine LJ, Silvagni P and Howard D (2000) Prey, parasites and pathology associated with the mortality of a juvenile gray whale (Eschrichtius robustus) stranded along the northern California coast. Diseases of Aquatic Organisms 42, 111–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felix JR (2013) Reported Incidences of Parasitic Infections in Marine Mammals from 1892 to 1978. Lincoln: Zea E-Books. [Google Scholar]

- Folmer O, Black M, Hoeh W, Lutz R and Vrijenhoek R (1994) DNA primers for amplification of mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase subunit I from diverse metazoan invertebrates. Molecular Marine Biology and Biotechnology 3, 294–299. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García-Varela M and Nadler SA (2005) Phylogenetic relationships of Palaeacanthocephala (Acanthocephala) inferred from SSU and LSU rDNA gene sequences. Journal of Parasitology 91, 1401–1409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García-Varela M and Nadler SA (2006) Phylogenetic relationships among Syndermata inferred from nuclear and mitochondrial gene sequences. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 40, 61–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García-Varela M, Cummings MP, Pérez-Ponce de León G, Gardner SL and Laclette JP (2002) Phylogenetic analysis based on 18S ribosomal RNA gene sequences supports the existence of class Polyacanthocephala (Acanthocephala). Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 23, 288–292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García-Varela M, Perez-Ponce de Leon G, Aznar FJ and Nadler SA (2009) Systematic position of Pseudocorynosoma and Andracantha (Acanthocephala, Polymorphidae) based on nuclear and mitochondrial gene sequences. Journal of Parasitology 95, 178–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García-Varela M, Pérez-Ponce de León G, Aznar FJ and Nadler SA (2013) Phylogenetic relationship among genera of Polymorphidae (Acanthocephala), inferred from nuclear and mitochondrial gene sequences. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 68, 176–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García-Varela M, Masper A, Crespo EA and Hernández-Orts JS (2021) Genetic diversity and phylogeography of Corynosoma australe Johnston, 1937 (Acanthocephala: Polymorphidae), an endoparasite of otariids from the Americas in the northern and southern hemispheres. Parasitology International 80, 102205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garey JR, Near TJ, Nonnemacher MR and Nadler SA (1996) Molecular evidence for Acanthocephala as a subtaxon of Rotifera. Journal of Molecular Evolution 43, 287–292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geijer CKA, Notarbartolo di Sciara G and Panigada S (2016) Mysticete migration revisited: are Mediterranean fin whales an anomaly? Mammal Review 46, 284–296. [Google Scholar]

- Golvan YJ (1961) The phylum of the Acanthocephala. III. The classification of Palaeacanthocephala (Meyer 1931). Annales de Parasitologie humaine et Comparee 36, 76–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregori M, Aznar FJ, Abollo E, Roura A, Gonzalez AF and Pascual S (2012) Nyctiphanes couchii as intermediate host for the acanthocephalan Bolbosoma balaenae in temperate waters of the NE Atlantic. Diseases of Aquatic Organisms 99, 37–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guillén-Hernández S, García-Varela M and Pérez-Ponce de León G (2008) First record of Hexaglandula corynosoma (Travassos, 1915) Petrochenko, 1958 (Acanthocephala: Polymorphidae) in intermediate and definitive hosts in Mexico. Zootaxa 1873, 61–68. [Google Scholar]

- Heckmann RA, Amin OM and El-Naggar AM (2013) Micropores of Acanthocephala, a scanning electron microscopy study. Scientia Parasitology 14, 105–113. [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez-Orts JS, Smales LR, Pinacho-Pinacho C, Garcia-Varela M and Presswell B (2016) Novel morphological and molecular data for Corynosoma hannae Zdzitowiecki, 1984 (Acanthocephala: Polymorphidae) from teleosts, fish-eating birds and pinnipeds from New Zealand. Parasitology International 66, 905–916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoberg EP, Daoust PY and McBurney S (1993) Bolbosoma capitatum and Bolbosoma sp. (Acanthocephala) from sperm whales (Physeter macrocephalus) stranded on Prince Edward Island, Canada. Journal of Helminthological Society of Washington 60, 205–210. [Google Scholar]

- Kaito S, Sasaki M, Goto K, Matsusue R, Koyama H, Nakao M and Hasegawa H (2019) A case of small bowel obstruction due to infection with Bolbosoma sp. (Acanthocephala: Polymorphidae). Parasitology International 68, 14–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura M (1980) A simple method for estimating evolutionary rate of base substitutions through comparative studies of nucleotide sequences. Journal of Molecular Evolution 16, 111–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S, Stecher G, Li M, Knyaz C and Tamura K (2018) MEGA X: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis across computing platforms. Molecular Biology and Evolution 35, 1547–1549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanfear R, Brett C, Simon YWH and Guindon S (2012) PartitionFinder: combined selection of partitioning schemes and substitution models for phylogenetic analyses. Molecular Biology and Evolution 29, 1695–1701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larkin MA, Blackshields G, Brown NP, Chenna R, McGettigan PA, McWilliam H, Valentin F, Wallace IM, Wilm A, Lopez R, Thompson JD, Gibson TJ and Higgins DG (2007) Clustal W and Clustal X version 2.0. Bioinformatics (Oxford, England) 23, 2947–2948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malyarchuk B, Derenko M, Mikhailova E and Denisova G (2014) Phylogenetic relationships among Neoechinorhynchus species (Acanthocephala: Neoechinorhynchidae) from North-East Asia based on molecular data. Parasitology International 66, 100–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcer F, Marchiori E, Centelleghe C, Ajzenberg D, Gustinelli A, Meroni V and Mazzariol S (2019) Parasitological and pathological findings in fin whales Balaenoptera physalus stranded along Italian coastlines. Diseases of Aquatic Organisms 133, 25–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Measures LN (1992) Bolbosoma turbinella (Acanthocephala) in a blue whale, Balaenoptera musculus, stranded in the St. Lawrence Estuary, Quebec. Journal of Helminthological Society of Washington 59, 206–211. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer A (1933) Acanthocephala. In Bronns HG (eds), Klassen und Ordnungen des Tier-Reichs Leipzig. Leipzig: Akademische Verlagsgesellschaft MBH, pp. 1–332. [Google Scholar]

- Morgulis A, Coulouris G, Raytselis Y, Madden TL, Agarwala R and Schaffer AA (2008) Database indexing for production MegaBLAST searches. Bioinformatics (Oxford, England) 24, 1757–1764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panigada S and Notarbartolo di Sciara G (2012) Balaenoptera physalus (Mediterranean subpopulation). The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species doi: 10.2305/IUCN.UK.2012.RLTS.T16208224A17549588.en (accessed 1 April 2021). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Parona C (1893) Sopra una straordinaria polielmintiasi da echinorinco nel Globicephalus svinerai Flow., pescato nel mare di Genova. Atti della Società Ligustica di Scienze Naturali e Geografiche 4, 314–324. [Google Scholar]

- Petrochenko VI (1956) Acanthocephala of Domestic and Wild Animals. Isdatelstvo: Akademii Nauk SSSR; (English Translation by the Israel Program for Scientific Translations, 1971). [Google Scholar]

- Phipps CJ (1774) A Voyage Towards the North Pole Undertaken by His Majesty's Command 1773. London: W. Bowyer and J. Nichols for J. Nourse. [Google Scholar]

- Porta A (1906) Ricerche anatomiche sull’Echinorhynchus capitatus v. Linst., e note sulla sistematica degli echinorinchi dei cetacei. Zoologischer Anzeiger Leipzig 30, 235–271. [Google Scholar]

- Presswell B, Garcia-Varela M and Smales LR (2018) Morphological and molecular characterization of two new species of Andracantha (Acantocephala: Polymorphidae) from New Zealand shags (Phalacrocoracidae) and penguins (Spheniscidae) with a key to the species. Journal of Helminthology 92, 740–751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rambaut A (2009) FigTree v1. 3.1: Tree figure drawing tool. Available at http://tree.bio.ed.ac.uk/software/figtree/ (Accessed 1 February 2021).

- Ronquist F and Huelsenbeck J (2003) MrBayes 3: Bayesian phylogenetic inference under mixed models. Bioinformatics (Oxford, England) 19, 1572–1574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santoro M, Di Nocera F, Iaccarino D, Cipriani P, Guadano Procesi I, Maffucci F, Hochscheid S, Cerrone A, Galiero G, Nascetti G and Mattiucci S (2018) Helminth parasites of the dwarf sperm whale Kogia sima (Cetacea: Kogiidae) from the Mediterranean Sea, with implications on host ecology. Diseases of Aquatic Organisms 129, 175–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santoro M, Palomba M, Mattiucci S, Osca D and Crocetta F (2020) New parasite records for the sunfish Mola mola in the Mediterranean Sea and their potential use as biological tags for long-distance host migration. Frontiers in Veterinary Science 7, 579728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki M, Katahira H, Kobayashi M, Kuramochi T, Matsubara H and Nakao M (2019) Infection status of commercial fish with cystacanth larvae of the genus Corynosoma (Acanthocephala: Polymorphidae) in Hokkaido, Japan. International Journal of Food Microbiology 305, 108256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaidya G, Lohman DJ and Meier R (2011) SequenceMatrix: concatenation software for the fast assembly of multi-gene datasets with character set and codon information. Cladistics 27, 171–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Cleave HJ (1953) Acanthocephala of North American mammals. Illinois Biological Monographs 23, 179. [Google Scholar]

- Verweyen L, Klimpel S and Palm HW (2011) Molecular phylogeny of the Acanthocephala (class Palaeacanthocephala) with a paraphyletic assemblage of the orders Polymorphida and Echinorhynchida. PLoS ONE 6, e28285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zdzitowiecki K (1991) Antarctic Acanthocephala. In Wägele JW and Sieg J (eds), Synopses of the Antarctic Benthos. Koenigstein: Koeltz Scientific Books, pp. 1–116. [Google Scholar]