Abstract

Academic Abstract

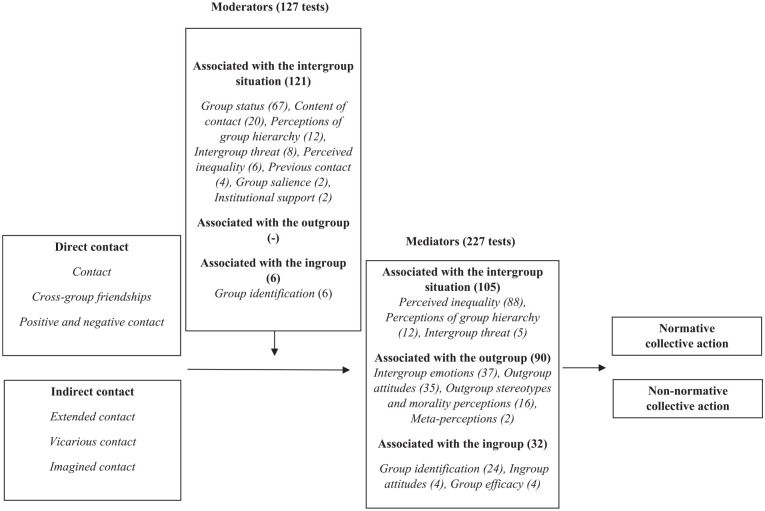

In this narrative review, we examined 134 studies of the relationship between intergroup contact and collective action benefiting disadvantaged groups. We aimed to identify whether, when, and why contact has mobilizing effects (promoting collective action) or sedative effects (inhibiting collective action). For both moderators and mediators, factors associated with the intergroup situation (compared with those associated with the out-group or the in-group) emerged as the most important. Group status had important effects. For members of socially advantaged groups (examined in 98 studies, 100 samples), contact had a general mobilizing effect, which was stronger when contact increased awareness of experiences of injustice among members of disadvantaged groups. For members of disadvantaged groups (examined in 49 studies, 58 samples), contact had mixed effects. Contact that increased awareness of injustice mobilized collection action; contact that made the legitimacy of group hierarchy or threat of retaliation more salient produced sedative effects.

Public Abstract

We present a review of existing studies that have investigated the relationship between intergroup contact and collective action aimed at promoting equity for disadvantaged groups. We further consider the influence of contact that is positive or negative and face-to-face or indirect (e.g., through mass or social media), and we distinguish between collective action that involves socially acceptable behaviors or is destructive and violent. We identified 134 studies, considering both advantaged (100 samples) and disadvantaged groups (58 samples). We found that intergroup contact impacts collective action differently depending on group status. Contact generally leads advantaged groups to mobilize in favor of disadvantaged groups. However, contact has variable effects on members of disadvantaged groups: It sometimes promotes their collective action in support of their own group; in other cases, it leads them to be less likely to engage in such action. We examine when and why contact can have these different effects.

Keywords: collective action, intergroup contact, intergroup relations, social change

Intergroup contact represents one of the most effective strategies for promoting positive intergroup relations (Hodson & Hewstone, 2013; Pettigrew & Tropp, 2006; Vezzali & Stathi, 2021). Although much of the work on intergroup contact has focused on the reduction of prejudice as a measure of movement toward social equity, improving out-group attitudes may in some cases lead (inadvertently) to reinforcing social hierarchies (Kteily & McClanahan, 2020; Saguy et al., 2017) that contribute to inequalities. It is therefore important, both theoretically and practically, to understand whether, how, and under what conditions contact predicts collective action aimed at achieving social equity. In particular, in this review, we define collective action broadly as support for the disadvantaged group, in terms of acts or intentions to benefit disadvantaged group members (e.g., by expanding their rights and opportunities through individual efforts or policies). Collective action thus represents solidarity-based behavior in support of disadvantaged groups aimed at achieving social equity (see also De Lemus & Stroebe, 2015; Vezzali & Stathi, 2021, Chapter 7).

The present work reviews and synthesizes evidence on the relation between contact and collective action to help delineate a state-of-the-art understanding of the research area.

There has been a recent surge of studies investigating the association between contact and collective action, culminating in various theoretical reviews (Dixon & McKeown, 2021; Hassler et al., 2021; MacInnis & Hodson, 2019; McKeown & Dixon, 2017; Saguy et al., 2017; Tropp & Barlow, 2018; Tropp & Dehrone, 2023; Vezzali & Stathi, 2021, Chapter 7). These previous reviews have focused on identifying specific elements of the relationship between contact and collective action (e.g., moderating and/or mediating variables; Vezzali & Stathi, 2021) or on proposing specific conceptual models (Hassler et al., 2021). These works have therefore generally been directed in a top-down way by particular models and hypotheses, producing relatively selective reviews of the relevant literature.

While prior reviews on this topic have been hypothesis-driven and confirmatory in their main objectives, we present a narrative review that adopts a “bottom-up” approach, representing a more comprehensive review of the literature on contact and collective action and identifying themes that emerge from our analysis of that literature. Narrative reviews, which are qualitative in their approach, are particularly appropriate when considering studies

that have used diverse methodologies, or that have examined different theoretical conceptualizations, constructs, and/or relationships. . . . They are a particularly useful means of linking together studies on different topics for reinterpretation or interconnection in order to develop or evaluate new theory (Siddaway et al., 2019, p. 775).

We view the current approach as complementary to other, recent systematic, and focused reviews. As distinguished by Siddaway et al. (2019), in contrast to a narrative review, a systematic review represents an analysis of a clearly articulated question that adheres to previously specified methods to identify, select, and critically appraise relevant research around the question that guided the review. Two recent, related reviews have been performed by Hassler et al. (2021) and by Reimer and Sengupta (2021). Hassler et al. (2023) reviewed the literature on contact and collective action structured as systematic evaluation of a specific model, the integrated contact-collective action model (which we subsequently discuss). Reimer and Sengupta (2023) conducted a preregistered “systematic review and meta-analysis” with the goal “to evaluate the evidence for and against the ‘ironic’ effects of intergroup contact” (p. 362).

We build on the literature they consider, integrate many ideas from those and other previous reviews, and organize our review and analysis not with a formal conceptual model but with a graphical representation intended to map the broader landscape of empirical findings in this area. We pursued a narrative, bottom-up approach instead of a meta-analysis to identify promising but under-researched areas relating to what is not yet known about intergroup contact and collective action.

We structured our narrative review around three goals relating to the general relationship of contact to collective action and the factors that shape and underlie that relationship. Our first goal is to answer the question of whether or not intergroup contact promotes collective action—that is, whether it has mobilizing effects (i.e., it promotes collective action) or sedative effects (i.e., it inhibits collective action). The second goal is to identify moderating factors to understand when contact will have a mobilizing or a sedative effect. Our third goal is to illuminate mediating processes that explain the pathway between contact and collective action. To systematize research conducted thus far and with the aim of facilitating future research, we group moderators and mediators into overarching categories related to the intergroup situation, the out-group, and the in-group. In so doing, we consider forms of intergroup contact that are receiving increasing attention, such as negative contact and indirect contact.

In addition, given their potential social impact, we distinguish between normative and non-normative forms of collective action. Whether collective action is normative or non-normative can be a contentious issue that needs a thorough consideration of multiple sociocultural elements. In this review, following the guidance of Wright et al. (1990) and Becker and Tausch (2015), we refer to normative collective action as socially acceptable behaviors (e.g., distributing leaflets) and to non-normative collective action as behavior that is destructive and violent that deviates from prevailing social norms and is often illegal.

In the next section, we present brief overviews of (a) general models of factors motivating collective action, (b) research on intergroup contact and prejudice reduction, and (c) works currently bridging intergroup contact and collective action. After that, we introduce a graphical representation (Figure 1) that organizes previous work in a way that maps our systematic review and analysis of the literature. We not only address the general question of whether intergroup contact promotes or inhibits collective action but also examine relevant moderators and mediators. In our concluding section, we offer suggestions for promising directions for future research.

Figure 1.

Graphical Representation of the Moderators and Mediators of the Relationship Between Contact and Collective Action.

Note. The numbers in parentheses indicate how many tests for each variable or category are included in the current review and analysis (see Tables 4 and 5).

Collective Action and Intergroup Contact: Overviews

Our primary focus is on the impact of intergroup contact on collective action. In this section, we therefore review some of the most prominent and generative psychological theories of collective action and the processes underlying it. Although research on collective action has traditionally emphasized the mobilization of members of disadvantaged groups (Wright & Lubensky, 2009), there is also currently a substantial literature on collective action by advantaged-group members that benefits a disadvantaged group (e.g., Cakal et al., 2021; Dixon, Durrheim, et al., 2010; Vázquez et al., 2020).

Theoretical Approaches for Understanding the Pathway to Collective Action

Research on collective action has been grounded to varying degrees in three basic processes relating to (a) social identity, (b) perceptions of the causes of disparities, and (c) a group’s capacity to address these disparities. The social identity model of collective action (SIMCA; Van Zomeren et al., 2008), for example, recognizes these processes in terms of group identification, perceived injustice, and perceived efficacy as key instigators of collective action.

These processes rest on three main socio-psychological perspectives. The first theoretical perspective relates to social identity theory (SIT; Tajfel & Turner, 1979), which places a strong emphasis on collective identity and, specifically, on in-group identification. A form of group identity especially relevant to collective action is that of politicized identity, which is identification with a particular social movement (Stürmer & Simon, 2004; Van Zomeren et al., 2008). According to Van Zomeren et al. (2008), social identification (especially, politicized identities) can predict collective action both directly and indirectly through increased perceptions of group efficacy and injustice. The second perspective is relative deprivation theory (Runciman & Runciman, 1966), which proposes that unfavorable intergroup comparisons lead to experiencing injustice and seeking to reduce it by engaging in collective action. Such an experience of injustice has both cognitive (perception that a group is disadvantaged compared with another group) and affective (intergroup emotions, such as anger, frustration, resentment, and outrage) dimensions. The third theoretical perspective that informs SIMCA highlights the role of perceived group efficacy (Bandura, 1997) as a motivating element to engage in collective action (Van Zomeren et al., 2004).

Extending SIMCA, Van Zomeren et al. (2012) directed their attention to the role of moral convictions, defined as “as strong and absolute stances on moral issues” (p. 52). If violated, moral convictions can lead to action to defend them (Van Zomeren & Lodewijkx, 2005). Moral convictions can therefore act as motivators of collective action (Skitka & Bauman, 2008).

Relatedly, Thomas et al. (2009; see also Thomas et al., 2012) proposed the encapsulation model of social identity in collective action (EMSICA), which accords social identity processes a central role in collective action. Unlike SIMCA (Van Zomeren et al., 2008), however, Thomas et al. (2009) considered social identification as an outcome rather than as an antecedent of perceived injustice and group efficacy. Furthermore, the model acknowledges reciprocal paths between group efficacy and perceived injustice, with the two constructs predicting each other.

Becker and Tausch (2015), inspired by SIMCA (Van Zomeren et al., 2008), described a key differentiation between normative and non-normative collective action in their dynamic model of engagement in normative and non-normative collective action. The authors further focused on the role played by emotions in predicting collective action. Specifically, they posited that normative and non-normative collective action are predicted by different emotions: While anger leads to increased normative collective action, non-normative collective action is primarily predicted by contempt. The model suggested by Becker and Tausch (2015) also considers the other relevant constructs hypothesized by SIMCA and specifies when they would be associated with the two forms of collective action. According to that framework, individuals are more likely to engage in normative collective action when they perceive high efficacy, and in non-normative collective action when perceived efficacy is low. Finally, individuals are more likely to opt for normative collective action when they perceive their social identification as strong, and in non-normative collective action when social identification is perceived as weak.

Turning the focus to collective action by advantaged-group members, the political solidarity model of social change (Subašić et al., 2008) aims to understand the perspective of the advantaged group and the conditions that may lead to an alliance between advantaged and disadvantaged groups. This model incorporates two approaches: SIT (Tajfel & Turner, 1979), and self-categorization theory (SCT; J. C. Turner et al., 1987). SIT places importance on the shift from personal to social identity and on the role of social identity in guiding intergroup relations. SCT conceptualizes the self as hierarchically organized, with more abstract categories reflecting higher levels of inclusiveness.

The political solidarity model (Subašić et al., 2008) illuminates how to create political solidarity between groups for the achievement of social equity. The process of political solidarity is explained in a triangular context, where the protagonists are the advantaged group, the disadvantaged group, and the authority. According to the model, the alliance between advantaged and disadvantaged groups is the result of a shared social identity between advantaged and disadvantaged groups, which excludes authority. In this process, the authority loses its legitimacy, increasing the likelihood of being challenged, suggesting that perceived illegitimacy leads to mobilization against social injustice. Importantly, the shared identity between advantaged and disadvantaged groups is not meant to obscure intergroup differences but to provide a meaningful context within which to understand them.

To summarize, research on collective action has traditionally, but not exclusively, focused on the actions of disadvantaged group members. This work has identified the key roles of (a) social identification with a group, with a particular politicized identity, or in relation to authority; (b) perceptions of unfair disadvantage or injustice, (c) feelings of efficacy for making change, and (d) moral convictions. While the research on collective action reveals several common and influential processes, our focus is specifically on the relationship between intergroup contact and intentions for and engagement in collective action.

Intergroup Contact and Prejudice Reduction

Much of the traditional research on intergroup contact has been centered on prejudice reduction as an outcome. Almost seven decades of research have shown that contact is associated with reduced prejudice, even when the optimal conditions originally proposed by Allport (1954) (e.g., equal status, cooperation for common goals, institutional support) are absent (Paluck et al., 2021; Pettigrew & Tropp, 2006). One limitation of research on intergroup contact is that it has focused to a much greater extent on advantaged group members than on disadvantaged group members in terms of how to improve the attitudes of members of advantaged groups toward disadvantaged groups (see Pettigrew & Tropp, 2006). In general, results have shown that contact is more effective at reducing intergroup bias among members of advantaged than disadvantaged groups, with effects among disadvantaged-group members often weaker and sometimes nonsignificant (Tropp & Pettigrew, 2005; Vezzali & Stathi, 2021).

The scope of research on intergroup contact has been expanded in recent years, for instance in terms of considering different forms of direct contact (e.g., showing the detrimental effects of negative contact; Graf & Paolini, 2017; Schafer et al., 2021) and including indirect forms of contact. Types of indirect contact, which do not involve face-to-face interaction, include extended and vicarious contact (respectively, knowing or observing an intergroup relationship; Dovidio et al., 2011; Vezzali et al., 2014; White et al., 2021; Wright et al., 1997; Zhou et al., 2019), and imagined contact (mentally simulating an intergroup interaction; Crisp & Turner, 2012; Miles & Crisp, 2014; see also White et al., 2021).

While there is considerable consensus in the field that positive intergroup contact generally makes intergroup attitudes more favorable, additional questions remain. Some of these involve the underlying processes that account for the reduction in prejudice. Multiple routes appear to be involved, including lessening intergroup anxiety or increasing empathy (Pettigrew & Tropp, 2008) as well as changing the ways members of another group are perceived, such as creating more individuated (Wilder, 1986) or personalized (Miller, 2002) perceptions or a greater sense of shared identity (Gaertner & Dovidio, 2000; Reimer et al., 2022). Other questions involve the durability of the effect of intergroup contact on prejudice reduction (Paluck et al., 2019).

The issues of primary interest in this review are additional ones: how intergroup contact relates to collective action as an outcome, and how many of the processes revealed in the study of contact effects on prejudice reduction reflect or supplement those currently recognized as factors shaping collective action. Although prejudice reduction and collective action may both appear to represent forces promoting intergroup equity, intergroup contact may, at least in some circumstances, produce divergent effects on these two outcomes because of the different ways it influences the dynamics underlying each.

Intergroup Contact and Collective Action

Various scholars have questioned the effectiveness of contact for producing social change and, ultimately, social equity (Dixon et al., 2005). Wright and Lubensky (2009) argued that the mechanisms by which contact improves out-group attitudes (e.g., reducing in-group identification, lowering perceptions of injustice) are the very same ones that may inhibit collective action (a sedative effect). Much of the theorizing of the sedative effects of contact has focused on collective action by members of disadvantaged groups (Dixon, Tropp, et al., 2010; Dovidio et al., 2016), for whom positive contact tends to reduce their focus on inequity and to have greater expectations of being treated fairly in the future (Saguy et al., 2009). However, the sedative effects of contact may also apply to members of advantaged groups in terms of taking actions to benefit disadvantaged groups. The “principle-implementation gap” refers to the finding that positive experiences of contact do not automatically translate into supporting or engaging in collective action (Dixon, Durrheim, et al., 2017; Dixon, Durrheim, et al., 2010). Dixon (2017) explained that increasing positive feelings toward the out-group (a distinctive feature of contact; Pettigrew & Tropp, 2008) reduces the salience of group boundaries and, consequently, the need to redress inequality toward one specific group, leading to sedative effects of contact (see also Cakal et al., 2011, Study 1). We review relevant theoretical and empirical work with the aim of providing a clearer understanding of the relation between contact and collective action, considering the effects separately for members of disadvantaged and advantaged groups.

Understanding how intergroup contact affects collective action is particularly valuable for integrating work within the area of intergroup relations. Although both collective action and prejudice reduction have attracted significant scholarly attention and produced vibrant literature in psychology across many years, as noted by Wright and Lubensky (2009), these lines of research traditionally proceeded largely independently. Also, despite the robustness and empirical evidence in support of the models of collective action we previously discussed, it is important to acknowledge that these models have not systematically considered the role of intergroup contact in the pathway to collective action—the issue that is the specific focus of the current work.

We are not alone in our interest in this issue. Several theoretical perspectives have been recently proposed to better understand the relationship between contact and collective action. Hassler et al. (2021) proposed the integrated contact-collective action model (ICCAM), which focuses on understanding when contact will have mobilizing or sedative effects among advantaged or disadvantaged group members. Among the relevant factors, the authors consider the type of contact (including its valence), perception of (il)legitimacy of group differences, extent to which group-specific needs are satisfied, social categorization, and intergroup ideologies.

Hassler, Ulug, et al.’s model considers important variables identified in contact as well as collective action research, with the aim of proposing relevant factors emerging from the two literatures rather than providing a broad and extensive review of variables specifically identified by research testing the association between contact and collective action. As an example, when discussing social categorization, the authors refer to the general literature on the common in-group identity model (Gaertner & Dovidio, 2000; Gaertner et al., 2016) together with research investigating categorization in the context of collective action but unrelated to contact research (Ufkes et al., 2016). While we view the work by Hassler, Ulug, et al. as complementary to our interests, our goals are both broader empirically—providing a more extensive review of the literature—and more focused conceptually—emphasizing the dynamics of contact more specifically.

MacInnis and Hodson (2019) have theorized about when a disadvantaged group will engage in social change. They focus on the importance of contact that can lead to cross-group friendships (which is an especially effective form of contact; Davies et al., 2011). They also highlight the relevance of the content of contact, in particular the importance of discussing group differences and social inequalities (which represents an important variable in the review and analysis that we present).

Vezzali and Stathi (2021, Chapter 7) proposed a sequential mediation to explain the relation of direct and indirect contact with normative and non-normative collective action. In this model, contact predicts socio-structural variables as posited by SIT (Tajfel & Turner, 1979), which in turn predict morality convictions. Further mediators include social categorization, and a series of variables, such as intergroup emotions, which have been shown to be associated with collective action (Becker & Tausch, 2015). Vezzali and Stathi (2021) also identified several moderators, such as content and valence of contact, social dominance orientation (SDO), and prejudice.

Overall, while the current models involving intergroup contact and collective action address many similar dynamics, they do so in different ways, from various perspectives, and with different primary objectives. These models generally highlight particular constructs, for instance, group identification (Hassler et al., 2021), content of contact (MacInnis & Hodson, 2019), and moral convictions (Vezzali & Stathi, 2021). In addition, the models of Hassler et al. (2021) and of MacInnis and Hodson (2019) represent theoretical elaborations that take literature on contact and collective action into consideration, but they do not focus specifically on findings that have emerged from the contact and collective action literature more broadly (including mediators and moderators). Those models have a broader aim: to understand based on available relevant literature when advantaged and disadvantaged groups will engage in collective action. The model introduced by Vezzali and Stathi (2021, Chapter 7), though more strongly rooted in studies on contact and collective action, is mainly aimed at understanding the complex and sequential mediational chains that can underlie contact effects. The present work presents a more comprehensive review of contact research that has investigated collective action, building on, extending, and synthesizing the literatures considered in previous reviews. Because the objective of a narrative review is to identify emergent themes and important gaps in the existing literature, the approach to identifying studies is broader and with a less prescribed methodology for narrative reviews than that for systematic meta-analytic efforts that test specific hypotheses (see Siddaway et al., 2019). For the present review, we searched for terms broadly related to collective action and social change (e.g., contact, affirmative action, collective action, polic+, social change, activism, critical action, sedative, mobilize, in different combinations) on the Psychinfo database, with October 18, 2021, as the cut-off date.

Building bottom-up from the empirical literature, we identify and classify both moderators and mediators into broad categories. These categories include and help systematize work guided by existing models, which generally focus selectively on moderators and mediators relevant to a specific conceptual position (e.g., Hassler et al., 2021; MacInnis & Hodson, 2019; Vezzali & Stathi, 2021). We integrate specific constructs, including those representing the focus of previous reviews, into broader categories that may favor an understanding of the whole literature on contact and collective action. Next, we introduce a graphical representation of our review and analysis of the literature to help summarize what is known and what is not to identify productive directions for future research in this area.

The Current Work: A Narrative Review

In our review of the literature, we pursue questions about whether, when, and why intergroup contact is associated with collective action distinguishing fundamentally between processes for advantaged and disadvantaged groups. The present review also considers the moderators of contact effects as they may relate to collective action and the mediating processes identified by empirical evidence. When relevant, we further distinguish between contact that is direct versus indirect and positive versus negative, as well as collective action that is normative versus non-normative. This approach offers a more thorough and state-of-the-art understanding of collective action as a function of intergroup contact.

Guided by previous research on intergroup relations (Sidanius & Pratto, 1999; Tajfel & Turner, 1979), one of the main goals of the present review is to understand the factors associated with the alliance between advantaged and disadvantaged groups. In line with previous work (e.g., Tausch et al., 2015), we conceptually define advantaged groups as those relatively high in power and/or status in a given social context and that, as a consequence, enjoy a disproportionate number of privileges and social benefits (e.g., greater wealth). We use the term disadvantaged groups to refer to groups that are relatively low in power and/or status in a particular context and, as a result, suffer a disproportionate amount of resource challenges (e.g., lower wages). Most commonly (in 63% of the studies reviewed), this distinction reflected racial or ethnic group membership. However, it also reflected other types of differences, for example, based on religion or citizenship status (see section “Review Overview”). We note that advantaged and disadvantaged group positions can vary substantially by social context: Relative group position can depend on a variety of factors, such as citizenship status, current socioeconomic position or sociopolitical influence, or the history of intergroup domination or discrimination based, for instance, on ethnicity or political affiliation.

Operationally, to differentiate advantaged from disadvantaged groups, we primarily relied on how the different groups were conceptualized by the authors of each article, that is, whether the groups were described as advantaged or disadvantaged (or as high or low in status and/or power) in each study. In all cases, the way the authors of the study classified groups as advantaged or disadvantaged aligned with how we distinguished the groups as well. To the extent that our focal dependent variable was support for disadvantaged groups, advantaged or disadvantaged group position can also be indirectly inferred from the target benefiting from collective action in each study. For example, in research exploring White participants’ support for Black people’s rights Black people are the disadvantaged group. In the very few cases where study authors did not directly refer to the relative advantage, status, or power of the groups explored, the authors of the present work coded the groups as advantaged or disadvantaged blindly and were in full agreement with the coding.

We selected articles that included at least one measure or manipulation of contact, and at least one measure of collective action. With respect to contact, we included articles that measured or manipulated at the individual-level face-to-face contact, considering different operationalizations of contact, including both quantity and quality as measures of contact, and we distinguish between these two when critical to the interpretation of the findings with respect to collective action. We also included indirect contact measures or manipulations classically used in literature in the form of extended, vicarious, or imagined contact.

For collective action measures, we adopted a broad definition, as specified at the beginning of the review, focusing on collective action aimed at promoting social equity. Therefore, when addressing the stance of the advantaged group, we refer to solidarity-based collective action benefitting the disadvantaged group. We considered a substantial range of measures, including support of (or opposition to) egalitarian policies and the rights for the disadvantaged group, intentions to engage in collective action on behalf of the disadvantaged group, or, when available, behavioral collective action measures. Resting on the distinction between normative and non-normative collective action presented earlier (see also Becker & Tausch, 2015), we considered as normative collective action nonviolent behaviors generally defined as socially acceptable, such as signing petitions, taking part in strikes, supporting egalitarian policies. In contrast, violent and illegal behaviors (like destruction of properties) were included in the category of non-normative collective action. Given that the present review primarily aims to investigate the relationship between contact and collective action, studies that did not include both contact (measured or manipulated) and collective action measures were not considered.

Considering the evaluation of the existing literature on contact and collective action, in line with our bottom-up approach, in Figure 1 we present a graphical representation of our analysis of the literature that strives to produce a state-of-the-art portrait of the field.

We broadly considered mediators and moderators that emerged from the literature. Because of the number and variety of such variables represented in our review of the literature, we then attempted to identify broader categories that could include them to present a more coherent organization for the research. We considered ways to categorize them that were parsimonious but, at the same time, reflect conceptual distinctiveness among constructs. We reasoned that grouping potential moderating and mediating variables into categories would be an instrumental step toward more systematization of the literature. Our proposed classification of moderating and mediating variables in the literature generally aligned with three categories that researchers in the areas of group processes and intergroup relations have distinguished, relating to the relation between the in-group and an out-group in a particular context, perceptions of the out-group, and the dynamics within one’s group (see Dovidio, 2013). Thus, in Figure 1, with the aim of better representing and interpreting the literature, moderators are differentiated into three categories: Moderators associated with the intergroup situation, the out-group, or the in-group. With respect to mediators, paralleling the moderator distinction, we denote factors related to the intergroup situation, the out-group or the in-group. The inclusion of a construct into one of these three categories was based on the agreement of all authors of the present work; discrepancies in interpretation were resolved by discussions among the authors until consensus. Such categorization currently has primarily a descriptive purpose, with the goal of facilitating a broader understanding of the literature and eventually identifying strengths or gaps.

Moderators or mediators concerning perceptions of the intergroup situation refer to constructs rooted in the simultaneous consideration of both the out-group and the in-group. As an example, perceived intergroup inequality implies that some group is advantaged over another group. The relative nature in this example makes perceived inequality an element of the intergroup situation rather than a quality primarily of the out-group or in-group in isolation.

Moderators or mediators in the out-group category involve constructs that primarily can be understood in reference to characteristics of the out-group, while moderators or mediators in the in-group category involve constructs primarily pertaining to the in-group and relatively independent from out-group perceptions. For example, because out-group attitudes are conceptually independent from in-group perceptions (Brewer, 2017), out-group attitudes as a moderator or mediator were considered as part of the out-group category. Similarly, because in-group identification can occur in ways independent of specific out-groups (R. Brown & Zagefka, 2005), it was included in the category of moderators or mediators referring to the in-group.

The research we included is presented in Tables 1 to 3, showing experimental, longitudinal, and correlational studies. In organizing the Tables, we present information relevant to the understanding of the empirical evidence in the research. We provide information about where (i.e., in which country) the studies were conducted. For each study, we also specify the sample, whether this represents advantaged or disadvantaged groups (or, in rare cases, equal status/intermediate status groups), and the relevant out-group (also in this case specifying whether the out-group is an advantaged or a disadvantaged group). In the case of longitudinal studies, we further specify the number of data collection waves and the approximate time between them.

Table 1.

Experimental Studies Evaluating the Relation Between Contact and Collective Action.

| Study | Participants and groups | Out-groups | Country | Type of contact | Mediator(s) | Moderator(s) | Dependent variable(s) | Contact effect |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bagci et al. (2019, Study 1) | Disadvantaged: 80 Kurd adults | Advantaged: Turks | Turkey | Imagined contact | Perceived discrimination (personal and group discrimination)A*

In-group identificationC* Relative deprivation (no effect)A* Out-group attitudes (no effect) B* |

/ | Collective action intentions (normative collective action) | Mobilization (direct and indirect effect) |

| Becker and Wright (2022, Study 1) | Advantaged: 89 students from a German university | Disadvantaged: members of another German university | Germany | Direct contact | / | Out-group member’s legitimization/illegimitization of intergroup inequality1*

Interpersonal closeness1* |

Collective action intentions (normative collective action) Behavioral collective action (normative collective action) |

Mobilization (effect for delegitimization of intergroup inequality coupled with high interpersonal closeness, for collective action intentions only) |

| Becker and Wright (2022, Study 2) | Advantaged: 192 students from a German university | Disadvantaged: members of another German university | Germany | Direct contact | / | Out-group member’s legitimization/illegimitization of intergroup inequality1*

Interpersonal closeness1* |

Collective action intentions (normative collective action) Behavioral collective action (normative collective action) |

Mobilization (effect for delegitimization of intergroup inequality coupled with high interpersonal closeness, for collective action intentions only) |

| Becker et al. (2013, Study 1) | Disadvantaged: 267 sexual minority adults | Advantaged: heterosexual people | United States | Direct contact (recalling a personal acquaintance) | / | Out-group friend’s legitimization/illegimitization of intergroup inequality1* | Public protest (normative collective action) Private protest (normative collective action) Violent protest (non-normative collective action) |

Sedative (direct effect of legitimization of intergroup inequality, for public protest only) |

| Becker et al. (2013, Study 2) | Disadvantaged: 81 university students | Advantaged: university students of a higher-status university | Canada | Direct contact | / | Out-group member’s ambiguity about/legitimization/illegimitization of intergroup inequality1* | Collective action intentions (normative collective action) Behavioral collective action (normative collective action) |

Sedative (direct effect of ambiguity about and legitimization of intergroup inequality) |

| Broockman and Kalla (2016) | Advantaged: 501 adults | Disadvantaged: transgender people | United States | Direct contact promoting perspective-taking | / | Political affiliation1* (no effect) | Support for laws benefiting transgender people (normative collective action) | Mobilization |

| De Carvalho-Freitas and Stathi (2017, Study 2) | Advantaged: 138 Brazilian workers | Disadvantaged: individuals with disability | Brazil | Imagined contact | Out-group attitudes (beliefs in people’s with disability’ work performance level)B* | Type of disability4* (no effect) | Support for rights of people with disability within the workplace (normative collective action) | Mobilization (direct and indirect effect) |

| Droogendyk et al. (2016, Study 1) | Disadvantaged: 138 international university students | Advantaged: domestic university students | Australia | Direct contact (recalling a personal acquaintance) | In-group identification (no effect) C*

Perceived injustice A* |

Support or ambiguity of support for international students1* | Collective action intentions (normative collective action) | Mobilization (direct and indirect effect for supportive contact) |

| Droogendyk et al. (2016, Study 2) | Disadvantaged: 203 immigrants | Advantaged: Canadians | Canada | Direct contact | Perceived injustice A* | Support-anger, support-guilt, or ambiguity of support for immigrants1* | Collective action intentions (normative collective action) | Mobilization (direct and indirect effect for supportive contact) |

| Fung et al. (2021) | Advantaged: 535 Asian adults | Disadvantaged: Individuals with mental illness | United States | Direct contact | / | / | Collective action intentions (normative collective action) | No effect |

| Kotzur et al. (2019, Study 2) | Advantaged: 74 German university students | Disadvantaged: asylum seekers | Germany | Direct contact | Out-group warmth (no effect) B*

Out-group competence (no effect) B* Intergroup emotions (pity, envy, contempt, admiration) (effect only for contempt)B* |

/ | Collective action intentions (normative collective action) | Mobilization (indirect effect) No effect (nonsignificant direct effect) |

| Lau et al. (2014) | Advantaged: 850 Chinese adults | Disadvantaged: sexual minorities | China | Imagined contact (manipulated) Direct contact (measured) |

/ | Direct contact1* | Support for anti-discrimination laws for sexual minorities (normative collective action) | Mobilization (direct effect for direct and imagined contact; effect for imagined contact among those with no direct contact) |

| Prati and Loughnan (2018, Study 2) | Advantaged: 53 British university students | Disadvantaged: Gypsies | UK | Imagined contact | Dehumanization (uniquely human traits/human uniqueness)B* | / | Support for Gypsy human rights (normative collective action) | Mobilization (direct and indirect effect) |

| Prati and Loughnan (2018, Study 3) | Equal status: 70 adults living in Italy | Equal status: Japanese people | Italy | Imagined contact | Dehumanization (human nature traits)B* | / | Support for Japanese human rights (normative collective action) | Mobilization (direct and indirect effect) |

| Shani and Boehnke (2017) | Advantaged: 217 Jew adolescents Disadvantaged: 281 Palestinian adolescents |

Disadvantaged: Palestinians Advantaged: Jews |

Israel | Direct contact (focused on discussions over power inequality) | Intergroup empathyB*

Intergroup hatred (no effect) B* Hope for future relationsA* Intergroup threat (realistic and symbolic) (no effect)A* Perceived equality A* |

Group1* | Support for equal rights (administered to Jews) or for social inclusion policies (administered to Palestinians) (normative collective action) | Mobilization (direct effect for both groups, indirect effect except indirect effect via perceived equality for Palestinians and via intergroup empathy for Jews) Sedative (indirect effect via perceived equality for Palestinians) |

| Techakesari et al. (2017) | Disadvantaged: 96 gay men Disadvantaged: 100 lesbians |

Advantaged: heterosexual people | Australia | Direct contact (recalling a personal acquaintance) |

LGBTIQQ identification C* |

Degree of contact supportive of LGBTIQQ rights1*

Group1* |

Collective action intentions (normative collective action) | Mobilization (direct effect for gay men stronger with strongly supportive contact, indirect effect for gay men) Sedative (direct effect for lesbians stronger with moderately supportive contact, indirect effect for lesbians) |

| Ulug and Tropp (2021, Study 3) | Advantaged: 258 White adults | Disadvantaged: Blacks | United States | Negative vicarious contact (videos on racial discrimination) | Perceived injustice A* | / | Collective action intentions for the Black Lives Matter movement (normative collective action) | Mobilization (indirect effect) No effect (nonsignificant direct effect) |

| Vázquez et al. (2020, Study 2a) | Disadvantaged: 305 Spanish female adults | Advantaged: men | Spain | Direct contact | Perceived personal discrimination A*

Fusion with the feminist movement (politicized identity) C* Out-group attitudes (no effect) B* In-group attitudes (no effect)C* |

Salience of personal discrimination as a woman1* | Collective action intentions (normative collective action) | Sedative (negative correlation with contact for quality but not quantity of contact, indirect effect for quality with low salience of personal discrimination) |

| Vázquez et al. (2020, Study 2b) | Advantaged: 225 Spanish male adults | Disadvantaged: women | Spain | Direct contact | Perceived out-group discrimination A*

Fusion with the feminist movement (politicized identity) C* Out-group attitudes (no effect)B* In-group attitudes (no effect)C* |

Salience of group discrimination as women1* | Collective action intentions (normative collective action) | Mobilization (positive correlation with contact, indirect effect for quality of contact with low salience of out-group discrimination) |

| Vezzali, McKeown, et al. (2021, Study 2) | Advantaged: 89 Italian adolescents | Disadvantaged: immigrants | Italy | Negative vicarious contact | Anger against injusticeA* | Social dominance orientation1* | Collective action intentions (normative collective action) | Mobilization (indirect effect among individuals high in social dominance orientation) No effect (nonsignificant correlation with negative vicarious contact) |

Note. The study by Shani and Boehnke (2017) is a pre-post quasi experiment. In the column “Moderator(s)” we also included variables that were not formally tested with statistical moderation analyses (e.g., we included “Group” as a moderator also when studies simply ran separate analyses for groups, finding different results). The superscript for moderators indicates inclusion in the categories of: (1*) moderators associated with the intergroup situation, (2*) moderators associated with the out-group, (3*) moderators associated with the in-group, (4*) moderators concerning socio-demographics. In the column “Mediator(s)” the superscripts indicate inclusion in the categories of: (A*) mediators referred to the intergroup situation, (B*) mediators referred to the out-group, (C*) mediators referred to the in-group. In the column “Contact effect,” where we refer to effects for the outcome variable, we specify whether contact leads to mobilization (contact associated with higher collective action) or sedative effects (contact associated with lower collective action) and indicate which types of effects emerged, in case there are more effects available; if only mobilization or sedative effects are mentioned without further specifications, only a direct effect emerged (when a direct effect was not presented, we reported the correlation whenever available). LGBT = lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender; LGBTQQ = lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and queer.

Table 3.

Correlational Studies Evaluating the Relation Between Contact and Collective Action.

| Study | Participants and groups | Out-groups | Country | Type of contact | Mediator(s) | Moderator(s) | Dependent variable(s) | Contact effect |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Albzour et al. (2019) | Disadvantaged: 159 Palestinian adults | Advantaged: Israelis | West Bank | Direct contact | Support for normalization of the relation with the advantaged group (normative collective action and out-group attitudes)B* | / | Motivation and willingness to engage in revolutionary resistance (non-normative collective action) | Sedative (correlation with contact and indirect effect) |

| Bagci and Turnuklu (2019) | Disadvantaged: 151 Kurd university students | Advantaged: Turks | Turkey | Positive and negative direct contact | Perceived discrimination (personal and group discrimination) (no effect)A*

In-group identificationC* Relative deprivationA* |

/ | Collective action intentions (normative collective action) | Sedative (positive direct contact: indirect effect) No effect (nonsignificant correlation for both positive and negative direct contact, nonsignificant indirect effect for negative contact) |

| Bagci et al. (2018) | Disadvantaged: 269 physically adults with disability | Advantaged: individuals without disability | Turkey | Direct contact (cross-group friendships) | Collective self-esteemC*

Perceived advantaged group’s attitudes (meta-perceptions) (no effect) B* |

/ | Collective action intentions (normative collective action) | Mobilization (correlation with contact and indirect effect) |

| Barth and Parry (2009) | Advantaged (possibly including some members of the disadvantaged group): 760 adults | Disadvantaged: gay people | United States | Direct contact | / | / | Support for a range of policies benefitting the rights of gay people (normative collective action) | Mobilization |

| Barth et al. (2009) | Advantaged (possibly including some members of the disadvantaged group): 760 adults | Disadvantaged: gay people | United States | Direct contact | / | / | Support for a referendum against the rights of gay people (normative collective action) | Mobilization |

| Berg (2009) | Advantaged: 708 White adults | Disadvantaged: immigrants | United States | Direct contact | / | / | Support for social policies favoring immigrants (normative collective action) | Mobilization |

| Brambilla et al. (2013) | Advantaged: 146 Italian adults | Disadvantaged: immigrants | Italy | Direct contact | Out-group morality B*

Sociability (no effect) B* Competence (no effect)B* |

/ | Collective action intentions (normative collective action) | Mobilization (correlation with contact and indirect effect) |

| Brannon (2018, Study 1) | Advantaged: 998 White university students Disadvantaged: 959 Asian university students |

Disadvantaged: ethnic minority groups | United States | Direct contact (including a measure of cross-group friendships) | / | / | Support for university commitment to racial and ethnic diversity (normative collective action) | Mobilization (only cross-group friendships) |

| Brannon (2018, Study 2) | Advantaged: 1075 White university students Disadvantaged: 249 Asian university students |

Disadvantaged: ethnic minority groups | United States | Direct contact (including a measure of cross-group friendships) | / | / | Support for affirmative action (normative collective action) Support for university commitment to racial and ethnic diversity (multicultural vs. colorblind approach) (normative collective action) |

No effect |

| K. T. Brown et al. (2003) | Advantaged: 375 White university students | Disadvantaged: Black people, ethnic minority groups | United States | Direct contact | / | / | Support for social policies benefiting Black people (normative collective action) Support for university policies benefitting ethnic minority groups (normative collective action) |

No effect (for support for social policies benefitting Black people) Mobilization (for support for university policies benefiting ethnic minority groups) |

| Cakal et al. (2021, Study 1) | Advantaged: 336 Turkish Cypriot adults | Disadvantaged: immigrants | Cyprus | Direct contact (cross-group friendships) | Intergroup anxiety (no effect)B*

Intergroup trust B* Perspective-taking B* |

/ | Support for immigrants’ engagement in collective action (normative collective action) | Mobilization (correlation with contact, indirect effect) |

| Cakal et al. (2021, Study 2) | Advantaged: 197 Romanian university students | Disadvantaged: Hungarian immigrants | Romania | Direct contact (cross-group friendships) | Intergroup anxiety B*

Intergroup trust B* Perspective-taking B* |

/ | Support for Hungarians’ engagement in collective action (normative collective action) | Mobilization (correlation with contact, indirect effect) |

| Cakal et al. (2021, Study 3) | Advantaged: 240 Israeli Jew university students | Disadvantaged: Israeli Palestinians | Israel | Direct contact (cross-group friendships) | Intergroup anxiety B*

Intergroup trust B* Perspective-taking B* |

/ | Support for Israeli Palestinians’ engagement in collective action (normative collective action) | Mobilization (correlation with contact, indirect effect) |

| Cakal et al. (2016, Study 2) | Disadvantaged: 209 Kurdish adults | Advantaged: Turks | Turkey | Direct contact (cross-group friendships) | Intergroup threat (realistic and symbolic)A* |

/ | Collective action intentions (normative collective action) | Sedative (correlation with contact, indirect effect) |

| Cakal et al. (2011, Study 1) | Disadvantaged: 488 Black South African university students | Advantaged: White South Africans | South Africa | Direct contact | In-group relative deprivationA*

In-group efficacy (no effect)C* |

/ | Collective action intentions (normative collective action) Support for social policies benefiting South Africans (normative collective action) |

Sedative (for both outcome variables: correlation with contact, indirect effect) |

| Cakal et al. (2011, Study 2) | Advantaged: 244 White South African university students | Disadvantaged: Black South Africans | South Africa | Direct contact | In-group relative deprivation (no effect) A*

In-group efficacy (no effect)C* |

/ | Collective action intentions (normative collective action) Support for social policies benefiting South Africans (normative collective action) |

Mobilization (correlation with contact) |

| Calcagno (2016) | Advantaged: 85 heterosexual adults | Disadvantaged: gay people | United States | Direct contact (cross-group friendships) | / | Gender4* (no effect) | Collective action intentions (normative collective action) Collective action intentions to fight bullying toward gay people (normative collective action) |

Mobilization (for both outcome variables) |

| Carter et al. (2019) | Advantaged: 1,021 White university students Disadvantaged: 110 ethnic minority university students |

Disadvantaged: ethnic minorities Advantaged: Whites |

United States | Direct contact (cross-group friendships) | Perceived injusticeA* | Group1* | Engagement in activism to foster university inclusiveness (normative collective action) | Mobilization (for Whites: direct and indirect effect) Sedative (for ethnic minority: direct and indirect effect) |

| Celebi et al. (2016) | Advantaged: 337 Turkish university students Disadvantaged: 288 Kurdish university students |

Disadvantaged: Kurds Advantaged: Turks |

Turkey | Direct contact (cross-group friendships) | / | Group1* | Support for Kurdish language rights (normative collective action) | Mobilization (for Turks: direct effect) No effect (for Kurds: nonsignificant direct effect) |

| Cernat (2019) | Disadvantaged: 604 Hungarian adults Disadvantaged: 602 Roma adults |

Advantaged: Romanians Disadvantaged: Roma (for Hungarians), Hungarians (for Roma) |

Romania | Direct contact (with the advantaged group, and with the other disadvantaged group (interminority contact) | / | Group1* | Support for non-specific social policies for Hungarians (normative collective action) Support for specific social policies for Hungarians (normative collective action) Support for non-specific social policies for Roma (normative collective action) Support for specific social policies for Roma (normative collective action) |

Sedative (contact with majority was associated with lower support for pro-disadvantaged policies, especially specific policies) No effect, Sedative (interminority contact was not associated with support for pro-in-group policies, except Roma’s contact with Hungarians which was associated with lower specific pro-in-group policies) Mobilization, Sedative (interminority contact was associated with greater support for non-specific out-group policies, but lower support for specific out-group policies among Hungarians; it was associated with greater support for both types of out-group policies among Roma) |

| Cocco et al. (2022) | Advantaged: 391 Italian adults | Disadvantaged: immigrants | Italy | Positive and negative direct contact | One-group perceptions A*

Out-group morality B* |

/ | Collective action intentions (measures of normative and non-normative collective action) Collective action support (measures of normative and non-normative collective action) |

Mobilization (positive contact: direct effect on normative collective action intentions and support, and on non-normative collective action support; indirect effect on normative collective action intentions and support) Mobilization (negative contact: direct effect on non-normative collective action intentions and support) Sedative (negative contact: direct and indirect effect on normative collective action intentions and support) No effect (positive contact: nonsignificant direct effect on non-normative collective action intentions; nonsignificant indirect effect on non-normative collective action intentions and support) |

| No effect (negative contact: nonsignificant indirect effect on non-normative collective action intentions and support) | ||||||||

| Debrosse et al. (2016) | Advantaged: 458 White South African adults Disadvantaged: 2,496 Black South African adults |

Disadvantaged: newcomers | South Africa | Direct contact | / | Group1*

Realistic threat1* (effect for Blacks) Numeric threat1* (effect for Whites) Newcomer category (race)4* |

Support for the rights of different categories of newcomers (temporary workers, refugees, illegal immigrants) (normative collective action) | Mobilization (Blacks: direct effect, mobilization for some newcomer groups with low realistic threat) No effect, Mobilization (Whites: nonsignificant direct effect, mobilization for some newcomer groups with low numeric threat) |

| Di Bernardo et al. (2022) | Advantaged: 163 Italian adults Disadvantaged: 129 immigrant adults |

Disadvantaged: immigrants Advantaged: Italians |

Italy | Direct contact | Out-group stereotypes B* | Group1* | Support for social policies benefiting the immigrant group (normative collective action) | Mobilization (advantaged: positive correlation with contact, indirect effect; disadvantaged: indirect effect) No effect (disadvantaged: nonsignificant correlation with contact) |

| Di Bernardo et al. (2021) | Advantaged: 392 Italian adolescents Disadvantaged: 165 immigrant adolescents |

Disadvantaged: immigrants Advantaged: Italians |

Italy | Direct contact | Status illegitimacy A*

Status stability (no effect) A* Permeability of group boundaries (no effect) A* |

Group1*

Group salience1* (for Italians) Focus on differences vs. similarities1* (no effect) |

Collective action intentions (normative collective action) | Mobilization (Italians: positive correlation with contact, indirect effect, effects of contact quality significant for high group salience) Mobilization (immigrants: positive correlation with contact, indirect effect for contact quantity) |

| Dixon, Cakal, et al. (2017) | Disadvantaged: 149 Muslim university students | Disadvantaged: disadvantaged people in general | India | Direct contact with disadvantaged groups (interminority contact) Direct with the advantaged Hindus group |

Group efficacy C*

Shared grievances A* |

Direct contact with the advantaged Hindus group1* | Collective action intentions (normative collective action) | Mobilization (contact with disadvantaged groups: positive correlation with contact, indirect effect, indirect effect for low direct contact with the advantaged Hindus group) No effect (contact with the advantaged group: nonsignificant correlation with collective action, nonsignificant indirect effect) |

| Dixon et al. (2015) | Disadvantaged: 185 Indian South African adults | Disadvantaged: individuals from informal settlements | South Africa | Direct contact (interminority contact) | Perceived group discriminationA*

Intergroup empathy (no effect) B* |

/ | Support for social policies benefiting residents of informal settlements (normative collective action) Collective action intentions (normative collective action) |

Mobilization (correlation with contact for both outcome variables, indirect effect only for collective action intentions) |

| Dixon et al. (2007) | Advantaged: 361 White South African adults Disadvantaged: 1,556 Black South African adults |

Disadvantaged: Black South Africans Advantaged: White South Africans |

South Africa | Direct contact | / | Group1*

Blacks’ socio-economic status4* (no effect) |

Support for social policies benefiting Black South Africans (normative collective action) | Mobilization (White South Africans) Sedative (Black South Africans) |

| Dixon, et al. (2020) | Advantaged: 794 White South African adults | Disadvantaged: disadvantaged racial groups | South Africa | Direct contact | Intergroup threat (realistic and symbolic)A*

Out-group attitudes (only for support for preferential policies)B* Perceived injusticeA* |

/ | Opposition to compensatory social policies benefitting disadvantaged racial groups (normative collective action) Opposition to preferential social policies benefiting disadvantaged racial groups (normative collective action) |

Mobilization (correlation with contact, indirect effect, effects for contact quality) |

| Dixon, et al. (2020) | Equal status: 242 Catholic adults Equal status: 246 Protestant adults |

Equal status: Protestants, for Catholics; Catholics, for Protestants | Northern Ireland | Positive and negative direct contact | Realistic threat A*

Symbolic threat (no effect)A* |

Group1* (no effect) | Support for Government’s decision to remove peace walls (normative collective action) | Mobilization (positive contact: correlation with contact, indirect effect) Sedative (negative contact: correlation with contact, indirect effect) |

| Du Toit and Quayle (2011) | Advantaged: 64 South African adults mostly White with good socio-economic status | Disadvantaged: disadvantaged racial groups | South Africa | Direct and extended contact with multiracial families | / | / | Resistance to social policies benefiting disadvantaged racial groups (normative collective action) | Mobilization (direct contact) No effect (extended contact) |

| Earle et al. (2021) | Advantaged: 71,991 adults (for analyses on lesbian/gay rights support); 70,056 adults (for analyses on transgender rights support) | Disadvantaged: LGBT people | 77 Countries including all Continents | Direct contact | / | Institutional support (Gay/lesbian rights at the Country level)1* (no effect) Transgender rights at the Country level (institutional support)1* |

Support for lesbian/gay people rights (normative collective action) Support for transgender people rights (normative collective action) |

Mobilization (effect of contact stronger when institutional support is low) |

| Ellison et al. (2011) | Advantaged and disadvantaged: approximately 1,100 White and Black adults | Disadvantaged: Latinos | United States | Direct contact | / | / | Support for social policies benefiting immigrants from Latin America (normative collective action) | Mobilization |

| Fasoli et al. (2016) | Advantaged: 125 heterosexual people | Disadvantaged: LGBT people | Italy | Direct contact | / | / | Support for social policies benefiting gay people (normative collective action) | Mobilization |

| Fingerhut (2011) | Advantaged: 202 heterosexual people | Disadvantaged: LGBT people | United States | Direct contact (cross-group friendships) | / | / | Collective action intentions (normative collective action) | Mobilization |

| Firat and Ataca (2022) | Advantaged: 210 Turkish Muslim adults | Disadvantaged: Syrians | Turkey | Direct contact | Perceived cultural distanceA* | Political orientation1* | Support for refugee rights (normative collective action) | Mobilization (correlation with contact, indirect effect, indirect effect for left-wing participants) |

| Flores (2015) | Advantaged: 1,006 adults | Disadvantaged: LGB individuals, transgenders | United States | Direct contact | Support for LGB rights (normative collective action) A* | / | Support for LGB rights (normative collective action) Support for transgender rights (normative collective action) |

Mobilization (direct effect of LGB contact; nonsignificant direct effect of transgender contact; direct effect LGB contact on support for transgender rights-secondary transfer effect; indirect effect of LGB contact) |

| Gerbert et al. (1991) | Advantaged: approximately 2,000 adults | Disadvantaged: people with AIDS | United States | Direct contact | / | / | Support for social policies denying people with AIDS their rights to work (normative collective action) | Mobilization |

| Gorska et al. (2017) | Advantaged: 27,409 heterosexual people | Disadvantaged: LGB people | 28 European countries | Direct contact | / | / | Support for LGB rights (normative collective action) | Mobilization (direct effect both at the individual and at the societal level) |

| Graf and Sczesny (2019) | Advantaged: 471 Swiss university students | Disadvantaged: immigrants | Switzerland | Positive and negative direct contact | Out-group attitudes B* | Political orientation1* | Intended financial support to a Swiss NGO helping migrants (normative collective action) | Mobilization (positive direct contact: correlation with contact, stronger indirect effect for right-wing individuals) Sedative (negative direct contact: correlation with contact, stronger indirect effect for right-wing than center individuals, no effect for left-wingers) |

| Hassler et al. (2020) | Advantaged: 3,216 ethnic majority group adults Advantaged: 4,898 cis-heterosexual adults Disadvantaged: 1,000 ethnic minority adults Disadvantaged: 3,883 LGBTIQ+ |

Disadvantaged: ethnic minorities Disadvantaged: LGBTIQ+ people Advantaged: ethnic majorities Advantaged: cis-heterosexual people |

69 Countries including all Continents | Positive and negative direct and extended contact | / | Group1* | High-cost and low-cost collective action intentions for the two disadvantaged groups (normative collective action) Support for social policies empowering the two disadvantaged groups (normative collective action) Intentions to work in solidarity with the two disadvantaged groups (normative collective action) |

Mobilization (advantaged group: positive contact) Sedative (advantaged group: negative contact) Mobilization (disadvantaged group: negative contact; positive contact for the measure of intentions to work in solidarity) Sedative (disadvantaged group: positive contact) |

| Hassler et al. (2022, Study 1) | Disadvantaged: 689 ethnic minority adults | Advantaged: ethnic majorities | Chile, Germany, Kosovo, UK, United States | Direct contact (five different operationalizations including measures of positive contact, cross-group friendships) | / | Supportive contact1*

Perceived illegitimacy1* |

Support for social change (five different operationalizations) (normative collective action) |

Sedative (direct effect, stronger effect for high perceived illegitimacy) Mobilization (direct effect, stronger effect for high supportive contact) |

| Hassler et al. (2022, Study 2) | Disadvantaged: 3,883 LGBTIQ+ | Advantaged: cis-heterosexual people | 18 Countries | Direct contact (five different operationalizations including measures of positive contact, cross-group friendships) | / | Supportive contact1*

Perceived illegitimacy1* |

Support for social change (five different operationalizations) (normative collective action) |

Sedative (direct effect, stronger effect for high perceived illegitimacy) Mobilization (direct effect, stronger effect for high supportive contact, stronger effect for high perceived illegitimacy) |

| Hassler et al. (2022, Study 3) | Advantaged: 2,937 ethnic majority group adults | Disadvantaged: ethnic or religious minorities | Belgium, Brazil, Chile, Germany, Israel, Kosovo, Poland, Serbia | Direct contact (five different operationalizations including measures of positive contact, cross-group friendships) | / | Supportive contact1*

Perceived illegitimacy1* |

Support for social change (five different operationalizations) (normative collective action) |

Mobilization (direct effect, stronger effect with high perceived illegitimacy) Sedative (stronger effect with high supportive contact) |

| Hassler et al. (2022, Study 4) | Advantaged: 4,203 cis-heterosexual adults | Disadvantaged: LGBTIQ+ people | 19 Countries | Direct contact (five different operationalizations including measures of positive contact, cross-group friendships) | / | Supportive contact1*

Perceived illegitimacy1* |

Support for social change (five different operationalizations) (normative collective action) |

Mobilization (direct effect, stronger effect with high supportive contact, stronger effect with high perceived illegitimacy) Sedative (stronger effect with high supportive contact, stronger effect with high perceived illegitimacy) |

| Hayes and Dowds (2006) | Advantaged: 781 majority citizens | Disadvantaged: immigrants | Northern Ireland | Direct contact | / | / | Support for social policies benefiting immigrants (normative collective action) | Mobilization |

| Hayward et al. (2018) | Disadvantaged: 195 Black adults Disadvantaged: 170 Latino adults |

Advantaged: Whites | United States | Positive and negative direct contact | Perceived group discriminationA*

Intergroup angerB* |

Group1* | Self-reported collective action behavior (normative collective action) Collective action intentions (normative collective action) |

Mobilization (direct effect of negative contact on both outcome variables for both groups; direct effect of positive contact on collective action intentions for Blacks; indirect effect of negative contact via perceived discrimination [not for collective action behavior for Latinos] and anger (not for collective action intentions for Latinos) for both groups) Sedative (indirect effect of positive contact via anger (except for Latinos for collective action intentions) and via perceived discrimination (for collective action intentions for Latinos) |

| Hong and Peoples (2020), student sample | Advantaged: 214 White university students | Disadvantaged: Blacks | United States | Direct contact | / | / | Behavioral collective action—Participation in the Black Lives Matter movement (normative collective action) | Mobilization |

| Hong and Peoples (2020), general sample | Advantaged: 108 White adults | Disadvantaged: Blacks | United States | Direct contact | / | / | Behavioral collective action—Participation in the Black Lives Matter movement (normative collective action) | Mobilization |

| Horne et al. (2017) | Advantaged: 139 heterosexual university students | Disadvantaged: LGB people | Russia | Direct contact | / | / | Support for LGB civil rights (normative collective action) | No effect |

| Huić et al. (2016) | Advantaged: 997 heterosexual people | Disadvantaged: gay people | Croatia | Direct and extended contact | / | / | Collective action intentions (normative collective action) | Mobilization |

| Jackman and Crane (1986) | Advantaged: 1,648 White adults | Disadvantaged: Blacks | United States | Direct contact | / | / | Support for social policies benefiting Blacks (normative collective action) | Mobilization |

| Kamberi et al. (2017) | Advantaged: 211 Macedonian adolescents Disadvantaged: 214 Albanian adolescents Disadvantaged: 202 Turkish adolescents Disadvantaged: 187 Roma adolescents |

Disadvantaged: Roma people | Republic of North Macedonia | Direct contact (with Roma, for non-Roma participants; with Macedonians, for Roma participants) | Perceived injustice (only for Turkish and Albanian people)A*

Negative out-group stereotypes (except for Roma)B* Positive intergroup emotions (except for Roma)B* |

Group1* | Support for social policies benefiting Roma people (normative collective action) | Mobilization (direct and indirect effect for all non-Roma groups) No effect (Roma people, nonsignificant direct and indirect effect) |

| Kauff et al. (2016, Study 1a) | Advantaged: 39,907 ethnic majority individuals Disadvantaged: 1,660 ethnic minority individuals |

Disadvantaged: ethnic minorities | 21 Countries and Israel | Majority’s positive direct contact | / | / | Support for anti-discrimination laws (normative collective action) | Mobilization (ethnic majority: direct effect both at the individual and at the societal level; ethnic minority: direct effect at societal level of majority’s positive contact) |

| Kauff et al. (2016, Study 1b) | Advantaged: 731 ethnic majority individuals Disadvantaged: 269 ethnic minority individuals |

Disadvantaged: ethnic minorities | Switzerland | Majority’s positive direct contact | / | / | Support for immigrant rights (normative collective action) | Mobilization (ethnic majority: direct effect both at the individual and at the societal level; ethnic minority: direct effect at societal level of majority’s positive contact) |

| King et al. (2009) | Advantaged: 856 Chinese people | Disadvantaged: transgender people | China | Direct contact | / | / | Support for equal opportunities for transgenders (normative collective action) Support for transgender civil rights (normative collective action) Support for anti-discrimination laws for transgenders (normative collective action) |

Mobilization |

| Kokkonen and Karlsson (2017) | Advantaged: initial sample of 9,725 elected political representatives | Disadvantaged: immigrants, women, blue-collar workers, youths, pensioners | Sweden | Direct contact (cross-group friendships) | / | / | Self-reported support for or advancement of political proposals to support the disadvantaged groups (normative collective action) | Mobilization (in favor of all groups except for women, for whom no effect emerged) |

| Lewis (2011) | Advantaged: 38,910 adults | Disadvantaged: LGB people | United States | Direct contact | / | Political orientation1*

Education4* Gender4* (no effect) Race4* (no effect) Religion type4* |

Support for LGB rights (normative collective action) | Mobilization (direct effect; effect stronger for liberals, low educated, evangelical vs. Protestants) |

| Lowinger et al. (2018) | Advantaged: 291 non-Asian university students | Disadvantaged: Asians | United States | Direct contact | Social normsA*

Attitudes toward affirmative action (no effect)A* Out-group attitudes (no effect)B* Intergroup competition (no effect)A* |

/ | Support for affirmative action policies at university benefitting Asians (normative collective action) | Mobilization (correlation with contact, indirect effect) |

| McKeown and Taylor (2017) | Equal status: 85 Catholic university students Equal status: 67 Protestant university students |

Equal status: Protestants, Catholics | Northern Ireland | Direct contact | Realistic threat (no effect)A*

Symbolic threatA* |

Group1* | Engagement in initiatives to support own group (normative collective action) Support for own group’s violent collective action (non-normative collective action) |

No effect (engagement in initiatives to support own group: nonsignificant direct effect) Sedative (support for violent action: direct effect, effect weaker for Protestants, indirect effect only for Protestants) Mobilization (engagement in initiatives to support own group: indirect effect via symbolic threat only for Protestants) |

| McLaren (2003) | Advantaged: 8,124 adults | Disadvantaged: immigrants | 17 European Countries | Direct contact (cross-group friendships) | / | / | Support for social policies benefiting immigrants (normative collective action) | Mobilization |

| Meleady et al. (2017) | Advantaged: 417 British adults | Disadvantaged: immigrants | UK | Positive and negative direct contact | Out-group attitudes B* | / | Voting intentions for the Brexit referendum (normative collective action) | Mobilization (positive contact: direct and indirect effect) Sedative (negative contact: direct and indirect effect) |

| Meleady and Vermue (2019, Study 1) | Advantaged: 202 White British university students and from the general population | Disadvantaged: Black people | UK | Positive and negative direct contact | Social dominance orientationA* | / | Support for the Black Lives Matter movement and collective action intentions (normative collective action) | Mobilization (positive contact: direct and indirect effect) Sedative (negative contact: indirect effect) No effect (negative contact: nonsignificant direct effect) |

| Meleady and Vermue (2019, Study 2) | Advantaged: 275 British university students and from the general population | Disadvantaged: immigrants | UK | Positive and negative direct contact | Social dominance orientation A* | / | Support for protests aimed to sustain immigrants’ rights as a consequence of Brexit and collective action intentions (normative collective action) | Mobilization (positive contact: direct and indirect effect) Sedative (negative contact: direct and indirect effect) |

| Mirete et al. (2022) | Advantaged: 245 university students | Disadvantaged: Individuals with intellectual disability | Spain | Direct contact | / | / | Support for the rights of individuals with intellectual disability (normative collective action) | No effect |

| Neumann and Moy (2018) | Advantaged: 37,623 European respondents | Disadvantaged: immigrants | 20 European Countries | Direct contact (including a measure of cross-group friendships) | / | Intergroup context homogeneity (of neighbourhood)1* | Support for social policies benefiting immigrants (normative collective action) | Mobilization (especially for contact quality and cross-group friendships) Sedative (direct effect of contact quantity, and for contact quantity in homogeneous neighborhood) |

| Pearson-Merkowitz et al. (2016) | Advantaged: 923 non-Latino adults | Disadvantaged: Latinos | United States | Direct contact | / | Political orientation1* | Support for allowing citizenship to illegal immigrants (normative collective action) | Mobilization (direct effect, effect stronger for Democrats) |

| Pereira et al. (2017) | Disadvantaged: 320 Roma people | Advantaged: Bulgarians | Bulgaria | Contact (single scale including direct and extended contact) | Ethnic identification C* | National identification3* | Collective action intentions (normative collective action) | Mobilization (direct effect) Sedative (indirect effect among low national identifiers) |