Abstract

The International Society of Nephrology (ISN) region of Oceania and South East Asia (OSEA) is a mix of high- and low-income countries, with diversity in population demographics and densities. Three iterations of the ISN-Global Kidney Health Atlas (GKHA) have been conducted, aiming to deliver in-depth assessments of global kidney care across the spectrum from early detection of CKD to treatment of kidney failure. This paper reports the findings of the latest ISN-GKHA in relation to kidney-care capacity in the OSEA region. Among the 30 countries and territories in OSEA, 19 (63%) participated in the ISN-GKHA, representing over 97% of the region’s population. The overall prevalence of treated kidney failure in the OSEA region was 1203 per million population (pmp), 45% higher than the global median of 823 pmp. In contrast, kidney replacement therapy (KRT) in the OSEA region was less available than the global median (chronic hemodialysis, 89% OSEA region vs. 98% globally; peritoneal dialysis, 72% vs. 79%; kidney transplantation, 61% vs. 70%). Only 56% of countries could provide access to dialysis to at least half of people with incident kidney failure, lower than the global median of 74% of countries with available dialysis services. Inequalities in access to KRT were present across the OSEA region, with widespread availability and low out-of-pocket costs in high-income countries and limited availability, often coupled with large out-of-pocket costs, in middle- and low-income countries. Workforce limitations were observed across the OSEA region, especially in lower-middle–income countries. Extensive collaborative work within the OSEA region and globally will help close the noted gaps in kidney-care provision.

Keywords: epidemiology, Global Kidney Health Atlas, ISN, kidney failure, kidney replacement therapy, Oceania and South East Asia

Rising rates of obesity, noncommunicable diseases, average population age, and new threats, such as climate change, are contributing to changing patterns of chronic kidney disease (CKD) and kidney failure (KF) across the world. Even within similar World Bank income-group countries, wide variability in health system architecture, and funding, as well as differences in the predominant patterns of CKD, lead to disparities in access to kidney care and kidney health outcomes.1,2

The International Society of Nephrology (ISN) Oceania and South East Asia (OSEA) region includes countries from the World Health Organization’s regions of South East Asia and the Western Pacific.3,4 The region includes a mixture of high-income countries (HICs) and middle-income countries (MICs), with diversity in population ethnicity, age distribution, and density, and predominant pattern of kidney disease. Although South East Asia for the most part is densely populated, the population of the Pacific region is sparse. The OSEA region is affected by a high prevalence of diabetes and infectious disease outbreaks and is susceptible to natural disasters. The low-lying islands of the Pacific are especially vulnerable to rising sea waters caused by climate change. Although well-structured and organized quality kidney-care delivery is available in countries such as Australia, New Zealand, Singapore, and Malaysia, it is limited in some Pacific Islands.5

The ISN launched the ISN-Global Health Kidney Atlas (ISN-GKHA) in 2016, to understand the state of kidney care around the world and explore variations in care within regions and countries. From the 2023 ISN-GKHA, findings for the ISN OSEA region are provided in this report, supplemented by data from literature reviews. The methodology for this research is described in detail elsewhere.6

Results

The ISN-GKHA results are broadly categorized as literature review (Tables 17, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20 and 2,7,21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26; Supplementary Table S127) and survey response (Figure 1, Figure 2, Figure 3, Figure 4; Supplementary Tables S2 and S3; Supplementary Figures S1 and S2).

Table 1.

General demographic and economic indicators of the ISN OSEA region7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20

|

Country/territory |

World Bank ranking | Total population (2022) | GDP (PPP) (2021 $ billion) | Total health expenditures (% of GDP 2021) | Annual cost KRT (US$)a and funding model |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HD | PD | Tx, 1st year |

Tx, later years | Funding for KRT | |||||

| Global, median [IQR] | — | 7,802,702,984 | 134 [40–545] | 6.2 [4.3–8.2] | 19,380 [11,818–38,005] | 18,959 [10,891– 31,014] | 26,903 [15,425– 70,749] | 14,537 [6098– 19,924] | |

| OSEA, median [IQR] | — | 720,284,052 | 238 [29–1138] | 4.1 [3.8–6.7] | 10,086 [7,758–29,264] | 8382 [6631– 17,062] | 30,133 [8509–42,877] | 10,287 [6098– 17,996] | |

| Australia | HIC | 26,141,369 | 1446 | 9.9 | 44,432 | 48,026 | 71,270 | 10,287 | Public (free) |

| Brunei Darussalam | HIC | 478,054 | 29 | 2.2 | 22,845 | 8954 | — | — | Public (free) |

| Cambodia | LMIC | 16,713,015 | 79 | 7 | 10,086 | — | — | — | Private/mixed |

| Fiji | UMIC | 943,737 | 11 | 3.8 | — | — | — | — | - |

| Indonesia | LMIC | 277,300,000 | 3566 | 2.9 | 8176 | 7664 | 14,181 | 3216 | Public (some fees) |

| Lao PDR | LMIC | 7,749,595 | 64 | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Malaysia | UMIC | 33,871,431 | 971 | 3.8 | 10,344 | 10,610 | 30,133 | 6466 | Mixed |

| Myanmar | LMIC | 57,526,449 | 238 | — | 3644 | 5011 | 4680 | — | Private/mixed |

| New Caledonia | HIC | 297,160 | 11 | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| New Zealand | HIC | 5,053,004 | 238 | 9.7 | 29,264 | 28,211 | 42,877 | 21,212 | Public (free) |

| Philippines | LMIC | 114,600,000 | 1013 | 4.1 | 5205 | 5205 | 8509 | 6098 | Public (some fees) |

| Samoa | LMIC | 206,179 | 1 | 6.4 | — | — | — | — | — |

| Singapore | HIC | 5,921,231 | 635 | 4.1 | 35,545 | 17,062 | 71,621 | 17,996 | Multiple systems |

| Thailand | UMIC | 69,648,117 | 1343 | 3.8 | 7758 | 6631 | 31,554 | 14,595 | Public (some fees) |

| Vietnam | LMIC | 103,800,000 | 1138 | 5.3 | 7809 | 7809 | 4978 | — | Public (some fees) |

—,data not reported or unavailable; GDP, gross domestic product; HD, hemodialysis; HIC, high-income country; IQR, interquartile range; ISN, International Society of Nephrology; KRT, kidney replacement therapy; LMIC, lower-middle–income country; OSEA, Oceania and South East Asia; PD, peritoneal dialysis; PDR, People’s Democratic Republic; PPP, purchasing power parity; Tx, kidney transplantation; UMIC, upper-middle–income country.

Cost is given in 2021 $.

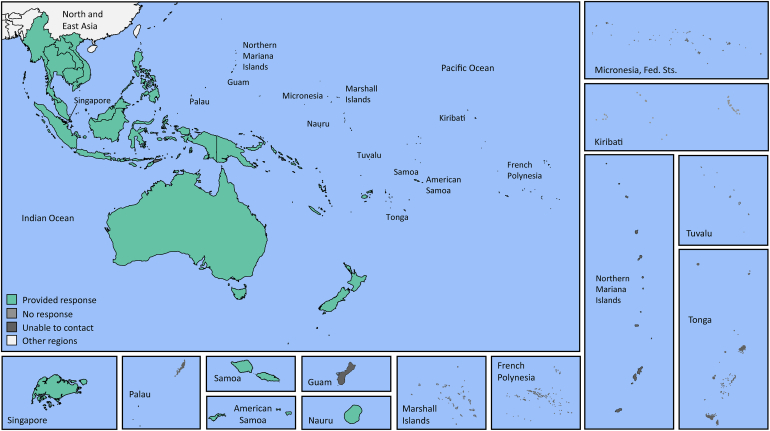

Figure 1.

Countries and territories of the International Society of Nephrology Oceania and South East Asia (ISN OSEA) region. Fed. Sts., federated states.

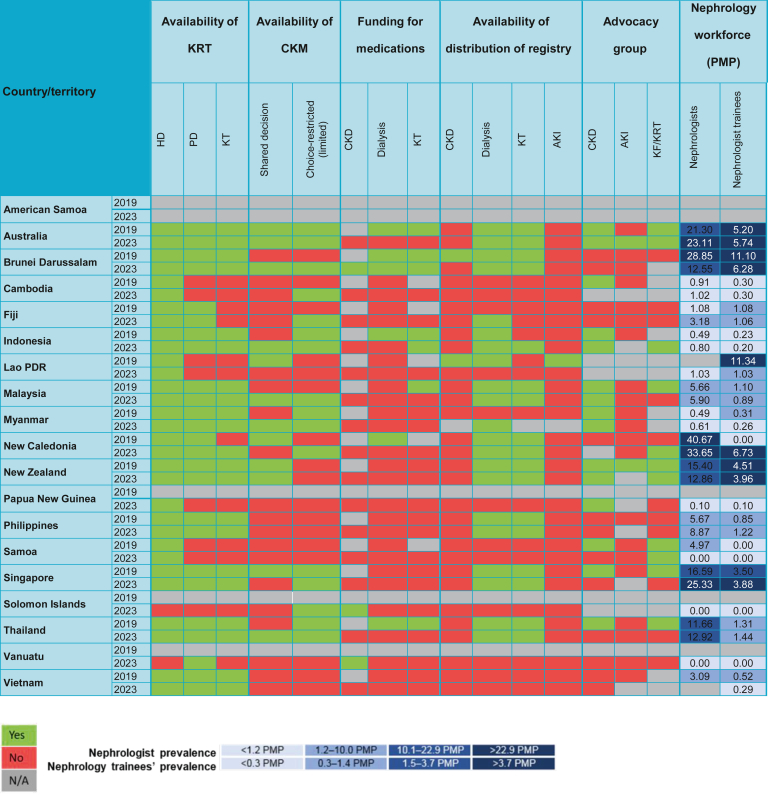

Figure 2.

Country-level scorecard for kidney replacement therapy (KRT), conservative kidney management (CKM), funding for medications, registry, and advocacy group in the International Society of Nephrology Oceania and South East Asia (ISN OSEA) region in 2019 and 2023. Funding for medications means that the medications are 100% publicly funded by the government (free at the point of delivery). AKI, acute kidney injury; CKD, chronic kidney disease; HD, hemodialysis; KF, kidney failure; KT, kidney transplantation; PD, peritoneal dialysis; PMP, per million population; N/A, not available or not provided; PDR, People’s Democratic Republic.

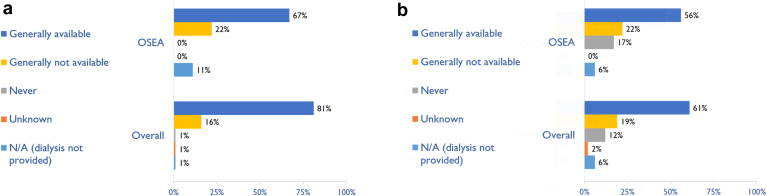

Figure 3.

Availability of (a) hemodialysis and (b) peritoneal dialysis in the International Society of Nephrology Oceania and South East Asia (ISN OSEA) region, compared to their global availability. Values represent the absolute number of countries in each category expressed as a percentage of the total number of countries. N/A, dialysis not provided.

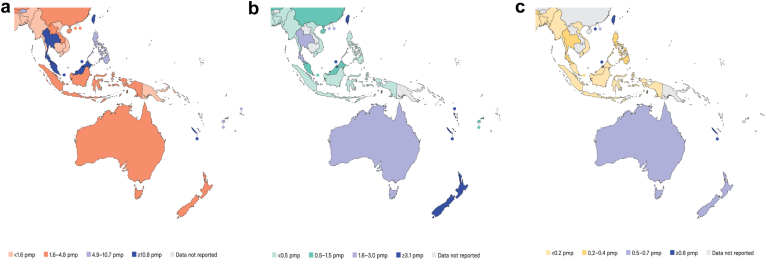

Figure 4.

Availability of kidney replacement therapy centers in the International Society of Nephrology Oceania and South East Asia (ISN OSEA) region: (a) hemodialysis centers; (b) peritoneal dialysis centers; and (c) transplantation centers. pmp, per million population.

Study setting

The ISN OSEA region is home to over 720 million people and includes South East Asian countries (Indonesia, Myanmar, Thailand, Timor-Leste, Brunei Darussalam, Cambodia, Lao People’s Democratic Republic [PDR], Malaysia, Philippines, Singapore, Vietnam), Australia, New Zealand, and a large group of Pacific Island nations (Kiribati, Marshall Islands, Federated States of Micronesia, Fiji, Nauru, Palau, Papua New Guinea, Samoa, Solomon Islands, Tonga, Tuvalu, Vanuatu; the French territories of French Polynesia and New Caledonia; and the US territories of American Samoa, Guam, and Northern Mariana Islands).7,8 The most populous countries are Indonesia (population 277 million), Philippines (114 million), and Vietnam (103 million). The OSEA region covers a land mass of 12.8 million square kilometers, with Australia representing 61% of the area.7,8 Population densities in the area vary widely, ranging from 3 people per square kilometer (Australia) to 308 people per square kilometer (Vietnam). Most countries are MICs, whereas Australia, Brunei Darussalam, New Caledonia, New Zealand, and Singapore are HICs or territories (Table 1).7,8 The ISN-GKHA is a global survey of clinicians, policymakers, advocacy groups, and kidney health society leads. The survey was supplemented with literature review, with data available for Australia, Brunei Darussalam, Cambodia, Fiji, Indonesia, Lao PDR, Malaysia, Myanmar, New Caledonia, New Zealand, Philippines, Samoa, Singapore, Thailand, and Vietnam.

Current status of kidney care

In the ISN OSEA region, vastly different healthcare systems and levels of economic development result in inequalities in access to, and availability and quality of, kidney care.

Literature-review data for countries in the ISN OSEA region

Burden of CKD in the OSEA region

Data from the Global Burden of Disease database reveal the burden of CKD in the region (Supplementary Table S1).27 The median prevalence of CKD was 10.4% (interquartile range [IQR]: 9.1–10.3], higher than the global prevalence of 9.5%.27 The prevalence of CKD ranged from 8.2% (95% confidence interval [CI] 7.6%–8.9%) in Cambodia to 16.7% (95% CI 15.5%–17.9%) in Thailand. The median prevalence of death in the region due to CKD was 3.4% (IQR 2.7%–4.2%) higher than the global median of 2.4% (IQR 1.6%–3.9%), and varied from 2.0% (95% CI 1.8%–2.2%) in Cambodia to 5.5% (95% CI 4.9%–6.0%) in Thailand. The median of disability-adjusted life years attributable to CKD for the OSEA region was 2.4% (IQR 1.97%–2.96%; global median 1.6% [IQR 1.5%–1.8%]) and was higher in low-middle–income countries (LMICs; e.g., 3.5% of total disability-adjusted life years in Samoa).7,27

Burden of KF in the OSEA region

The overall prevalence of treated KF in the ISN OSEA region was 1203 per million population (pmp) among 9 countries with available data; this level is 45% higher than the global median of 823 pmp (Table 2).21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26 Singapore (2030 pmp) and Thailand (2063 pmp) had almost double the prevalence of treated KF, compared to that in Australia (1054 pmp) or New Zealand (1009 pmp), and an even larger difference in the incident number of people with KF. The incidence of KF was highest in Brunei (393 pmp), Thailand (377 pmp), and Singapore (364 pmp). In Australia and New Zealand, the number of people on chronic dialysis was similar to the number of those with a kidney transplant (around 500 pmp). By contrast, in Malaysia, Philippines, Brunei, Singapore, and Thailand, 5–60 fold as many people were on chronic dialysis. In all countries for which data were available, hemodialysis (HD) was more commonly chosen than peritoneal dialysis (PD) for chronic kidney replacement therapy (KRT). Although the prevalence of treated KF in the ISN OSEA region was higher than that in the rest of the world, the median number of people living with a kidney transplant in OSEA (104 pmp) was less than half that in the global estimation (279 pmp; Table 2).21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26

Table 2.

Incidence and prevalence of kidney replacement therapy in the ISN OSEA region7,21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26

| Country / territory | World Bank ranking | Treated kidney failure |

Chronic dialysis prevalence |

Kidney transplantation |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Incidence | Prevalence | Total | HD | PD | Incidence | Prevalence | ||

| Global | 146 | 823 | 397 | 323 | 21 | 12 | 279 | |

| OSEA region | 283 | 1203 | 980 | 177 | 95 | 4 | 104 | |

| Australia | HIC | 127 | 1054 | 549 | 454 | 95 | 35 | 505 |

| Brunei Darussalam | HIC | 393 | 1673 | 1235 | 1065 | 170 | — | — |

| Cambodia | LMIC | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Fiji | UMIC | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Indonesia | LMIC | 306 | 973 | 973 | - | 3.3 | 2 | — |

| Lao PDR | LMIC | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Malaysia | UMIC | 259 | 1352 | 1295 | 970 | 95 | 2 | 58 |

| Myanmar | LMIC | — | — | — | — | — | 0.04 | — |

| New Caledonia | HIC | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| New Zealand | HIC | 133 | 1009 | 583 | 484 | 182 | 39 | 426 |

| Philippines | LMIC | 172 | 319 | 314 | 69 | 10 | 1 | 5 |

| Samoa | LMIC | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Singapore | HIC | 364 | 2030 | 2030 | 1762 | 269 | 12 | 398 |

| Thailand | UMIC | 377 | 2063 | 1969 | 823 | 369 | 10 | 93 |

| Vietnam | LMIC | — | — | 53 | 412 | 12 | 3 | — |

—,data not reported or unavailable; HD, hemodialysis; HIC, high-income country; ISN, International Society of Nephrology; LMIC, lower-middle-income country; OSEA, Oceania and South East Asia; PD, peritoneal dialysis; People’s Democratic Republic, PDR; UMIC, upper-middle-income country.

Incidence and prevalence are per million population.

Overview of gross domestic product and government health expenditure by individual countries

Health expenditure as a percent of gross domestic product varied between and within country income-level categories, from 2% (Brunei) to 10% (Australia), and from 2.9% (Indonesia) to 7% (Cambodia; Table 1).8

Cost of KRT in the OSEA region

The global median health spending was $216 per person, and $163 for the OSEA region.28 For the 11 countries with available data, the median annual cost for HD was $10,086 for the OSEA region, just over half the global median of $19,380 (Table 1).9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20 The median annual cost for PD was $8382 for the OSEA region, less than half the global median of $18,959. Annual costs for HD and PD were higher in HICs (e.g., Australia $44,432 and $48,026, respectively), but these treatments were largely free to the individual. Costs were lower in MICs, such as Indonesia ($8176 and $7664, respectively), but were often covered by private payors (Cambodia and Myanmar; Table 1).9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20 The cost of PD and HD was nearly equivalent in most countries except Brunei (PD 2.5 times cheaper; Table 1).9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20 Taking a long-term perspective, for all countries in the OSEA region with established transplantation programs, kidney transplantation appeared to be a more sustainable KRT option than dialysis, owing to the costs being lower beyond the first year (Table 1).9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20

Survey response data for countries in the ISN OSEA region that participated in the survey

Characteristics of countries

Of the 30 countries and territories in the ISN OSEA region, 17 countries and 2 territories (New Caledonia and American Samoa) participated (63%), representing over 97% of the region’s population (Figure 1). Four HICs, 4 upper-middle–income countries (UMICs), and 9 LMICs were represented. New Caledonia and American Samoa are territories—high-income and upper-middle–income, respectively.7 The survey had 47 respondents, 29 nephrologists (62%), 5 non-nephrologist physicians (11%), 2 nonphysician health professionals (4%), and 11 others (23%).

Availability and affordability of services for the delivery of CKD care

Nondialysis CKD care was available in all countries and was publicly funded and free at point of delivery in 21% of countries in the region, compared to the global median of 27%, with solely private funding in 5%, compared to 6% globally. Nondialysis CKD medications were fully government funded in 17% of OSEA region countries, compared to 16% globally (Supplementary Figure S1).

Availability and affordability of services for the delivery of KF care

In the region, chronic dialysis was available in 95% of countries (none in Solomon Islands), but only 56% of countries were able to provide access (availability and affordability) to dialysis to at least half the people needing it, lower than the global median of 74%.

Chronic HD services were available in 16 countries in the region (89%; Figure 2), compared to 98% of countries globally. In 12 countries in the ISN OSEA region (67%), HD was generally available, compared to 81% of countries globally (Figure 3). In 4 countries, HD existed (Lao PDR, Myanmar, Papua New Guinea, and Vietnam), but it was generally unavailable. Chronic HD was not available at all in either Solomon Islands or Vanuatu. Home HD was generally available in Australia, New Zealand, and Philippines (17% of countries, compared to 19% globally).

Chronic PD services were available in 14 of 17 countries and 2 territories (74%; Figure 2), compared to 79% of countries globally. In 10 countries of the region (56%), PD was generally available, compared to 61% of countries globally (Figure 3). In 4 countries (Cambodia, Vanuatu, Fiji, and Vietnam), PD existed, but it was generally unavailable. PD was not available in Lao PDR, Papua New Guinea, Samoa, or Solomon Islands.

Kidney transplantation services were available in 11 countries (61%; Figure 2), compared to 70% globally. Despite this, in only 39% of countries could at least half of all people eligible for transplantation actually access transplantation services. In the region, 36% (n = 4; Brunei Darussalam, Myanmar, Indonesia, and Vietnam) of countries were offering transplantation using live donors only, compared to a global average of 29%. For those centers with a transplant waitlist, 82% had a national waitlist, higher than the global average of 64%. Transplantation was not available in Cambodia, Fiji, Lao PDR, Samoa, Vanuatu, or Solomon Islands.

Conservative kidney management (CKM) was generally available in 7 countries (39%; Figure 2), compared to 53% globally. CKM existed but was generally not available in a further 9 countries (50%) and was not available at all in Vanuatu.

Chronic dialysis and transplantation were free at the point of delivery in 17% of OSEA region countries (18 countries provided data), compared to 43% globally (Supplementary Table S2). Publicly funded, chronic HD, free at the point of delivery was available in only 17% of countries, compared to 45% globally. Publicly funded PD, free at the point of delivery, was available in only 11% of countries, compared to 42% globally. Kidney transplantation medications were free in 11% of countries, compared to 36% globally. HICs had acute kidney injury (AKI) and KRT care that was either publicly funded (free at the point of care) or funded through mixed or multiple systems. In contrast, in MICs, care was solely privately funded (Vanuatu, Papua New Guinea), partially publicly funded (Indonesia, Philippines, Thailand, Vietnam), or had mixed funding (Malaysia, New Caledonia; Supplementary Table S2). Dialysis and transplantation medications were fully government-funded for 6% and 11% of countries, respectively, compared to 24% and 30% globally (Figure 2).

Pediatric kidney care in the ISN OSEA region

In the region, differences were present in access to dialysis care for children and adults. Of all the countries with HD services, 88% provided HD to adults and children, but 12% provided it to adults only. In countries where PD was offered, 75% reported more access for adults than children. This region had a median of 0.13 (IQR 0.0–0.79) pediatric nephrologists pmp, compared to a global median of 0.69 (IQR 0.03–1.78; Supplementary Table S3).

Health workforce and infrastructure

Within the ISN OSEA region, 6% of countries reported having extremely poor health infrastructure, and 27% reported having poor or below-average infrastructure. In countries providing HD, the median of HD treatment centers was 9.36 pmp, compared to 5.1 pmp globally. However, the prevalence increased with country wealth, from 0.96 chronic HD centers pmp in Vietnam to 40 pmp in New Caledonia (Figure 4; Supplementary Table S3). Themedian of PD treatment centers was 1.75 pmp in countries with PD services, similar to the global median of 1.6 pmp (Figure 4; Supplementary Table S3). The OSEA region median of kidney transplantation centers in countries with access to transplantation was 0.74 pmp, higher than the global median of 0.46 pmp (Figure 4; Supplementary Table S3).

In the region, 72% of specialist physicians primarily responsible for the medical care of people with KF were nephrologists, and 28% were primary care physicians, compared to 87% and 7%, respectively, for the world. In most LMICs, primary care physicians are the main providers of medical care for KF. However, in all income settings, nurses, technicians, and other allied healthcare providers play a vital role in the healthcare team.

The region had 3.2 nephrologists pmp, compared to a global median of 11.8 pmp. The prevalence of nephrologists varied by country income, with Australia (23 pmp) and Singapore (25 pmp) having the highest workforce capacity (Figure 2; Supplementary Table S3.) However, even among HICs, marked variation in capacity was present, with New Zealand and Brunei (both 13 pmp) having half the nephrologist density of Australia and Singapore (Supplementary Table S3). Most middle-income countries had 1–6 nephrologists pmp. whereas Vanuatu and Solomon Islands had no nephrologists. The median prevalence of nephrology trainees in the region was 0.96 pmp (global median 1.15 pmp), with Australia, Brunei, and New Caledonia being better staffed, with 5–7 trainees pmp. Nephrologist prevalence remained similar from 2019 to 2023, except in Brunei (where it halved) and Fiji (where it tripled). The majority of respondents (60%) reported shortages in non-nephrologist KF care providers, a category that includes surgeons, allied health professionals (e.g., dialysis and nursing staff, technicians, dieticians, and social workers), and supporting service providers, such as radiologists and counsellors and psychologists (Supplementary Figure S3).

Registries, advocacy, and policy for kidney disease

Dialysis registries existed in 11 countries, and transplant registries existed in 9 countries (Figure 2). All HICs had dialysis and transplant registries. No countries had AKI or CKD registries. CKD advocacy groups existed in Australia, Indonesia, Malaysia, Myanmar, New Zealand, and Papua New Guinea. KF advocacy groups existed in Australia, Indonesia, New Caledonia, New Zealand, and Samoa. The only AKI advocacy group was in Australia.

Discussion

The 2023 ISN-GKHA highlighted that outcomes for people with CKD were worse in the ISN OSEA region, compared to global data, and that notable variations exist in access to care, usually related to national income levels. The prevalence of CKD and CKD-related deaths was higher in the region, compared to the global median. The burden of disability related to CKD was nearly double the global median, and it was higher in LICs in the region. Treated KF was 43% more prevalent in the ISN OSEA region, compared with the global median, yet access to kidney transplantation was far lower than the global median and was directly related to country wealth. Although the annual costs of HD and PD were around half the global median, lower availability of dialysis and the need for copayments in MICs made it difficult for many people to access KRT.

The noted limitations in the availability of KRT services in a large proportion of the countries is especially concerning given that the prevalence of CKD in the ISN OSEA region (10.4%) was higher than the global median (9.5%) and has increased in many countries even since the previous iteration of the 2019 ISN-GKHA.5.In Thailand, the CKD prevalence has increased from 13.9% to 16.7%.5 Similar to findings in the last ISN-GKHA, a lack of CKD prevalence data remained in most of the Pacific Island nations. A failure to understand the scope of the burden of CKD in these countries hampers efforts to screen for CKD and translates into missed opportunities to change the disease course with antiproteinuric and blood pressure– lowering medications.29 Although data from Malaysia showed that a majority of people with known CKD were prescribed appropriate cardiovascular disease prevention medications, low rates of screening for CKD indicate that opportunities to prescribe protective treatments are being missed.30 Accurate and current data on the prevalence of CKD are indispensable for planning efficient healthcare resource allocation and developing screening and early intervention programs.31

The causes of CKD likely vary around the OSEA region, with chronic glomerulonephritis and infectious disease–related CKD occurring in some countries, and obesity and diabetes playing major roles in Pacific countries.32, 33, 34, 35 Understanding the burden of CKD is the first step to discovering regional variations in risk factors and developing targeted risk-reduction programs. To this end, some countries have started evaluating local noncommunicable disease risk factors: for example, Guam has instituted a longitudinal health assessment of university students and integrated the research on noncommunicable diseases into the core curriculum.36 Addressing the main precipitants of kidney disease will help reduce its burden, and potential exists for increasing leverage by linking with other disciplines to consolidate spending and extract necessary information to inform treatment strategy.

The prevalence of treated KF was higher in the ISN OSEA region (1203 pmp), compared to the global median (823 pmp). The prevalence was driven by data from a few countries with universal access to healthcare. In many LICs, marked disparities were present between the prevalence of CKD and the prevalence of treated KF. For example, in Philippines, the rate of CKD was 9.5%, similar to the 10.8% seen in Australia. However, the prevalence of treated KF was 319 pmp in Philippines, compared to 1054 pmp in Australia. The missing numbers likely represent those who died prematurely from reaching the KF stage and not having access to KRT. Even for those with treated KF, with the exception of Australia, New Zealand, and a select few countries, the proportion receiving dialysis far outweighs the proportion receiving transplantation. This situation will create an even greater financial burden, with cost implications limiting access to dialysis for others.

Most forms of kidney care in the ISN OSEA region were less available and less affordable than the global average. Although nondialysis CKD care was available in all countries, it was wholly publicly funded in less than a quarter (21%), was lower than the global median of 27%, and was unchanged since 2019. Among countries with fully publicly funded nondialysis CKD care, all except Solomon Islands were HICs or UMICs. Many MICs have put considerable effort into establishing and expanding KF programs, despite their limited resources. For example, in Fiji, where the consumer pays for dialysis at the point of care, nephrologists have worked through an ISN Sister Renal Center program with an Australian hospital to establish HD clinics, and it now has 6 dialysis centers.37 Likewise, the National Kidney Foundation of Samoa has established a sister renal center program with Counties Manukau Hospital in New Zealand to support dialysis initiatives in Samoa. This example demonstrates how international cooperation and partnerships can play a vital role in improving access to KRT services. Despite these efforts, fewer countries in the region, particularly the Pacific Islands, have publicly funded chronic dialysis and transplantation, compared to the rest of the world. The level of access to transplantation remained lower than the global median, and in Solomon Islands, no access was available to any form of KRT. The transplantation rate remained low in countries where only living-donor transplantation is available (Brunei, Indonesia, Myanmar, Vietnam). This limitation can be attributed to factors such as medical infrastructure, awareness, and perhaps cultural norms affecting the willingness of individuals to donate organs. Transplantation remained unavailable in several MICs. The majority of people with CKD in the ISN OSEA region reside in LICs or LMICs where the prevalence is rising rapidly, and t the level of affordability of kidney care is low.38,39

The level of access to CKM in the ISN OSEA region is noted to be the lowest in the world, and minimal improvement in access occurred between the 2019 and 2023 ISN-GKHA iterations.40 Although CKM provides high value to people living with kidney disease, delivery of CKM requires infrastructure, resources, and training, which may not be readily available in LICs and LMICs.41 Within the region, economic, social, or cultural influences, as well as knowledge and clinical practice culture, may also impact CKM access. For instance, a study from Indonesia found that physicians were more likely to recommend dialysis, compared to CKM, for wealthier people.42 A study from Philippines found widespread support for CKM, but many institutions were unable to offer it.43 This finding suggests that a gap exists between the demand for CKM and the capacity of healthcare facilities to provide it.

Moreover, the level of access to publicly funded AKI care (including AKI-related dialysis) was also lower in the ISN OSEA region, compared to that in other world regions. This finding is largely unchanged since the 2019 GKHA.44 Given that public funding for KRT increases with income level, this finding is not surprising, but it may be an important contributor to increased mortality in LICs and LMICs where people living with kidney disease have less capacity to cover out-of-pocket costs. AKI is common in LICS and MICs, with a diverse range of causes, including infections, heat, envenomation, and medications.45,46 Lack of access to publicly funded AKI care may be explained by low rates of government prioritization of AKI in the region and lack of AKI advocacy support. Government recognition is key to supporting the development and implementation of policies and strategies that ensure adequate AKI care, even as advocacy groups play an important role in creating awareness among communities and political leaders and organizing regional and national resources to support disease prevention and treatment.47

This situation is further complicated by the geography and remote nature of the communities. Access to kidney care in rural areas is complicated by challenging terrains, transportation, and lack of local facilities, resulting in people having to travel hours to obtain kidney treatment.1 The impact on families can also be catastrophic, as the absence of public funding for kidney care in most LICs and LMICs often results in high out-of-pocket costs for kidney-care treatment. Families either cannot afford to pay for care or are financially crippled by the costs. Kidney disease is the most common cause of catastrophic family health expenditure for people in LICs and MICs.48 Mitigation strategies for climate change are a barrier to establishing solid health infrastructure, impacting kidney-care delivery, particularly in small island states that are especially vulnerable to rising sea levels.

The high burden of kidney disease in the ISN OSEA region calls for urgent action from governments and health systems. High-quality registries such as those in Australia and New Zealand may serve as a model for registries in other countries in the region.49 Reliable data on kidney disease incidence, treatment patterns, and outcomes will inform resource allocation by policymakers and underpin effective advocacy for improved access to KF treatment and for primary and secondary prevention of CKD.50 The large burden of CKD in the region also underscores the need and opportunity for clinical trials to recruit people in the region. In 2017, the ISN outlined a “stretch” goal of “30 by 30”—that is, 30% of people with CKD should be enrolled in clinical trials by 2030.51 Given the large burden of CKD in the region and the unique epidemiologic factors (e.g., IgA nephropathy), developing trial infrastructure and the workforce in the region should be a priority, and includes leveraging registries to enable collection of trial endpoints.52,53 Finally, greater collaboration between advocacy and professional organizations across countries is critical to facilitating the exchange of skills between workforces to improve equity and access to kidney care.

The 2023 ISN-GKHA had some limitations; these have been discussed.6 However, this work is important for guiding kidney-care policy in the OSEA region.

Conclusion

CKD is more common in the ISN OSEA region, with poorer access to kidney care, than it is in the rest of the world. Barriers to optimal kidney care are multifactorial, and they include the limited health system infrastructure, workforce, and governmental health spending. Although progress has been made on extending the reach of kidney care and developing registries, further collaborative work in the region is needed to achieve ISN's vision of a future in which all people have equitable access to sustainable kidney health. The 2023 ISN-GKHA had some limitations; these have been discussed.6 However, this work is important for guiding kidney-care policy in the ISN OSEA region.

Regional Board and ISN-GKHA Team Author disclosures

MRD reports personal fees (consultancy) from National Renal Care, outside the submitted work; and being the Chair of the African Renal Registry and Co-chair of the South African Renal Registry. SND reports research funding from Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Alberta Innovates, and Alberta Health Services, outside the submitted work. IE reports grants from Fonds de Recherche du Québec - Santé, outside the submitted work. MJJ reports other from Akebia, AstraZeneca, Baxter, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Janssen, CSL, Vifor, Merck, OccuRx, Chinook Therapeutics, Cesas Linx, Medcon International PACE CME, Medscape, Amgen, Roche, Vifor, AstraZeneca, OccuRx, Merck; grants from Medical Research Future Fund Next Generation, Clinical Researchers Program, Gambro, Baxter, Eli Lilly, MSD, Amgen, CSL, and Dimerix, outside the submitted work. RK reports grants from Baxter HealthCare, other from AstraZeneca, outside the submitted work. JLK reports personal fees from AstraZeneca Singapore Pte Ltd, Boehringer Ingelheim Singapore Pte Ltd, and Otsuka Pharmaceuticals (Singapore) Pte Ltd, outside the submitted work. ET reports personal fees from Baxter, outside the submitted work. IDTA reports consulting fees from Lifebridge Dialysis Center and Mondial Kidney Care Center, honoraria from DeGa International Pharma Corp and the Philippine Society of Nephrology, and a leadership role with Kidney International Reports and Kidney360 as Visual Abstract Editor, outside the submitted work. All the other authors declared no competing interests.

Funding Source

This article is published as part of a supplement sponsored by the International Society of Nephrology with grant funding to the University of Alberta (RES0033080).

Role of the Funder/Sponsor

The International Society of Nephrology provided administrative support for the design and implementation of the survey and data collection activities. The authors were responsible for data management, analysis, and interpretation, as well as manuscript preparation, review, and approval, and the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Disclosures

YC reports grants and other from Baxter Healthcare, outside the submitted work. HH reports personal fees from AWAK Technology and Baxter Healthcare, and nonfinancial support from Mologic Company, outside the submitted work. TK reports personal fees from Otsuka Pharmaceutical, grants from National Research Council of Thailand, personal fees from AstraZeneca, and personal fees from Baxter Healthcare, outside the submitted work. BBLN reports personal fees (advisory boards, speaker honoraria) from AstraZeneca and Boehringer and Ingelheim, personal fees (advisory boards) from Alexion, Bayer, and Cambridge Healthcare Research; and personal fees (speaker honoraria) from Cornerstone Medical Education, Medscape, and The Limbic, outside the submitted work, with all fees paid to The George Institute for Global Health. BS is supported by a Research Establishment Fellowship from the Royal Australasian College of Physicians; and reports personal fees from CSL Vifor and Research Review, and nonfinancial support from IxBiopharmaceuticals, all outside the submitted work; and unpaid committee memberships on ANZSN Research Advisory Committee, INCH study steering committee and the RESOLVE study (Australia) steering committee. ST reports fellowship grants from the International Society of Nephrology (ISN)–Salmasi Family and the Kidney Foundation of Thailand, outside the submitted work. SA reports personal fees from the International Society of Nephrology (ISN), outside the submitted work. AKB reports other (consultancy and honoraria) from AMGEN Incorporated and Otsuka; other (consultancy) from Bayer and GSK; grants from Canadian Institute of Health Research and Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada, outside the submitted work; and being the Associate Editor of the Canadian Journal of Kidney Health and Disease and Co-chair of the ISN-Global Kidney Health Atlas. SD reports personal fees from the ISN, outside the submitted work. JD reports personal fees from the ISN, outside the submitted work. VJ reports personal fees from GSK, AstraZeneca, Baxter Healthcare, Visterra, Biocryst, Chinook, Vera, and Bayer, paid to his institution, outside the submitted work. DWJ reports consultancy fees, research grants, speaker’s honoraria and travel sponsorships from Baxter Healthcare and Fresenius Medical Care; consultancy fees from AstraZeneca, Bayer, and AWAK; speaker’s honoraria from ONO and Boehringer Ingelheim & Lilly; travel sponsorships from ONO and Amgen, outside the submitted work; and being a current recipient of an Australian National Health and Medical Research Council Leadership Investigator Grant, outside the submitted work. CM reports personal fees from the ISN, outside the submitted work. MN reports grants and personal fees from KyowaKirin, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chugai, Daiichi Sankyo, Torii, JT, Mitsubishi Tanabe; grants from Takeda and Bayer; and personal fees from Astellas, Akebia, AstraZeneca, and GSK, outside the submitted work. MGW reports other from Travere, Otsuka, Eledon, Alpine, Kira Pharma, CSL-Behring, George Clinical, Chinook, AstraZeneca, Amgen, Boehringer-Ingelheim and Baxter, outside the submitted work. All the other authors declared no competing interests.

Acknowledgments

The authors appreciate the support from the International Society of Nephrology (ISN’s) Executive Committee, regional leadership, and Affiliated Society leaders at the regional and country levels for their help with the ISN–Global Kidney Health Atlas.

Footnotes

Supplementary Table S1. Burden of chronic kidney disease (CKD) in the International Society of Nephrology–Oceania and South East Asia (ISN OSEA) region.

Supplementary Table S2. Funding for kidney replacement therapy (KRT) in the International Society of Nephrology–Oceania and South East Asia (ISN OSEA) region.

Supplementary Table S3. Workforce and kidney replacement therapy (KRT) centers per million population (pmp) for medical kidney care in the International Society of Nephrology–Oceania and South East Asia (ISN OSEA) region.

Supplementary Figure S1. Funding for nondialysis chronic kidney disease (CKD; left) care and (right) medications in the International Society of Nephrology–Oceania and South East Asia (ISN OSEA) region.

Supplementary Figure S2. Funding for (left) dialysis and (right) transplant medications in the International Society of Nephrology–Oceania and South East Asia (ISN OSEA) region.

Supplementary Figure S3. Workforce shortages for medical kidney care in the International Society of Nephrology–Oceania and South East Asia (ISN OSEA) region.

Contributor Information

Muh Geot Wong, Email: muhgeot.wong@sydney.edu.au.

Sunita Bavanandan, Email: sbavanandan@gmail.com.

the Regional Board and ISN-GKHA Team Authors:

Abdul Halim Abdul Gafor, Atefeh Amouzegar, Paul Bennett, Sonia L. Chicano, M. Razeen Davids, Sara N. Davison, Hassane M. Diongole, Smita Divyaveer, Udeme E. Ekrikpo, Isabelle Ethier, Voon Ken Fong, Winston Wing-Shing Fung, Anukul Ghimire, Basu Gopal, Hai An Ha Phan, David C.H. Harris, Ghenette Houston, Kwaifa Salihu Ibrahim, Meg J. Jardine, Kailash Jindal, Surasak Kantachuvesiri, Dearbhla M. Kelly, Peter Kerr, Siah Kim, Rathika Krishnasamy, Jia Liang Kwek, Vincent Lee, Adrian Liew, Chiao Yuen Lim, Aida Lydia, Aisha M. Nalado, Timothy O. Olanrewaju, Mohamed A. Osman, Anna Petrova, Khin Phyu Pyar, Parnian Riaz, Syed Saad, Aminu Muhammad Sakajiki, Noot Sengthavisouk, Stephen M. Sozio, Nattachai Srisawat, Eddie Tan, Sophanny Tiv, Isabelle Dominique Tomacruz Amante, Anthony Russell Villanueva, Rachael Walker, Robert Walker, and Deenaz Zaidi

APPENDIX

Regional Board and GKHA Team Authors

Abdul Halim Abdul Gafor: Department of Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia, Cheras, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia

Atefeh Amouzegar: Division of Nephrology, Department of Medicine, Firoozgar Clinical Research Development Center, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

Paul Bennett: School of Nursing and Midwifery, Griffith University, Brisbane, Queensland, Australia

Sonia L. Chicano: Anatomic Pathology Division, Pathology and Laboratory Medicine Department: National Kidney and Transplant Institute, Quezon City, Philippines

M. Razeen Davids: Division of Nephrology, Department of Medicine, Stellenbosch University and Tygerberg Hospital, Cape Town, South Africa

Sara N. Davison: Division of Nephrology and Immunology, University of Alberta Faculty of Medicine and Dentistry, Edmonton, Alberta, Canada

Hassane M. Diongole: Division of Nephrology, Department of Medicine, National Hospital Zinder, Zinder, Niger; Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Zinder, Zinder, Niger

Smita Divyaveer: Department of Nephrology, Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education and Research, Chandigarh, India

Udeme E. Ekrikpo: Department of Internal Medicine, University of Uyo/University of Uyo Teaching Hospital, Uyo, Nigeria

Isabelle Ethier: Division of Nephrology, Centre Hospitalier de l’Université de Montréal, Montréal, Québec, Canada; Health Innovation and Evaluation hub, Centre de Recherche du Centre Hospitalier de l’Université de Montréal, Montréal, Québec, Canada

Voon Ken Fong: Department of Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia, Cheras, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia

Winston Wing-Shing Fung: Department of Medicine & Therapeutics, Prince of Wales Hospital, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China

Anukul Ghimire: Division of Nephrology, Department of Medicine, University of Calgary, Calgary, Alberta, Canada

Basu Gopal: Department of Renal Medicine, Alfred Health, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia; Central Clinical School, Monash University, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia

Hai An Ha Phan: Division of Nephrology, Department of Internal Medicine, Hanoi Medical University, Hanoi, Vietnam

David C.H. Harris: Centre for Transplantation and Renal Research, Westmead Institute for Medical Research, University of Sydney, Westmead, New South Wales, Australia

Ghenette Houston: Division of Nephrology and Immunology, Faculty of Medicine and Dentistry, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Alberta, Canada

Kwaifa Salihu Ibrahim: Nephrology Unit, Department of Medicine, Wuse District Hospital, Abuja, Nigeria; Department of Internal Medicine, College of Health Sciences, Nile University, Federal Capital Territory, Abuja, Nigeria

Meg J. Jardine: NHMRC Clinical Trials Centre, University of Sydney, Sydney, New South Wales, Australia; Concord Repatriation General Hospital, Sydney, New South Wales, Australia

Kailash Jindal: Division of Nephrology and Immunology, Faculty of Medicine and Dentistry, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Alberta, Canada

Surasak Kantachuvesiri: Department of Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, Mahidol University, Bangkok, Thailand

Dearbhla M. Kelly: Wolfson Centre for the Prevention of Stroke and Dementia, University of Oxford, John Radcliffe Hospital, Oxford, UK; Department of Intensive Care Medicine, John Radcliffe Hospital, Oxford, UK

Peter Kerr: Division of Nephrology, Monash Medical Centre, Clayton, Victoria, Australia; Monash University, Clayton, Victoria, Australia

Siah Kim: School of Public Health, University of Sydney, Camperdown New South Wales, Australia; Centre for Kidney Research, The Children’s Hospital at Westmead, Westmead, New South Wales, Australia

Rathika Krishnasamy: Department of Nephrology, Sunshine Coast University Hospital, Queensland, Australia; Faculty of Medicine, The University of Queensland, Queensland, Australia

Jia Liang Kwek: Department of Renal Medicine, Division of Medicine, Singapore General Hospital, SingHealth Pte Ltd, Singapore, Singapore

Vincent Lee: Westmead Applied Research Centre, Faculty of Medicine and Health, The University of Sydney, Australia; Centre for Kidney Research, School of Public Health, The University of Sydney, Australia

Adrian Liew: The Kidney & Transplant Practice, Mount Elizabeth Novena Hospital, Singapore, Singapore

Chiao Yuen Lim: Department of Renal Services, Raja Isteri Pengiran Anak Saleha (RIPAS) Hospital, Ministry of Health, Bandar Seri Begawan, Brunei Darussalam

Aida Lydia: Division of Nephrology and Hypertension, Department of Internal Medicine, Faculty of Medicine Universitas Indonesia—Dr Cipto Mangunkusumo Hospital, Jakarta, Indonesia

Aisha M. Nalado: Department of Medicine, Bayero University Kano, Kano, Nigeria

Timothy O. Olanrewaju: Division of Nephrology, Department of Medicine, College of Health Sciences, University of Ilorin, Ilorin, Nigeria; Julius Global Health, Julius Center for Health Sciences and Primary Care, University Medical Center Utrecht, Utrecht University, Utrecht, The Netherlands

Mohamed A. Osman: Department of Family Medicine, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada

Anna Petrova: Department of Propaedeutics of Internal Medicine, Bogomolets National Medical University, Kyiv, Ukraine; Department of Nephrology,"Diavita Institute," Kyiv, Ukraine

Khin Phyu Pyar: Department of General Medicine/Nephrology, Defence Services Medical Academy, No(1) Defence Services General Hospital, Yangon, Myanmar

Parnian Riaz: Division of Nephrology, Department of Medicine, McMaster University, Hamilton, Ontario, Canada

Syed Saad: Division of Nephrology and Immunology, Faculty of Medicine and Dentistry, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Alberta, Canada

Aminu Muhammad Sakajiki: Department of Medicine, Usmanu Danfodiyo University and Usmanu Danfodiyo University Teaching Hospital, Sokoto, Nigeria

Noot Sengthavisouk: Nephrology Department, Mittaphab Hospital, Vientiane Capital, Laos

Stephen M. Sozio: Department of Medicine, Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, Baltimore, Maryland, USA; Department of Epidemiology, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, Maryland, USA

Nattachai Srisawat: Division of Nephrology, Department of Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, Chulalongkorn University and King Chulalongkorn Memorial Hospital, Bangkok, Thailand; Center of Excellence for Critical Care Nephrology, Faculty of Medicine, and Tropical Medicine Cluster, Chulalongkorn University, Bangkok, Thailand

Eddie Tan: Regional Renal Unit, Waikato Hospital, Hamilton, New Zealand

Sophanny Tiv: Division of Nephrology and Immunology, Faculty of Medicine and Dentistry, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Alberta, Canada

Isabelle Dominique Tomacruz Amante: Section of Nephrology, Asian Hospital and Medical Center, Manila, Philippines

Anthony Russell Villanueva: Division of Adult Nephrology National Kidney & Transplant Institute, Quezon City, Philippines

Rachael Walker: School of Nursing, Faculty of Medicine and Health Science, University of Auckland, Auckland, New Zealand; Renal Department, Te Matau a Maui Hawke’s Bay, Hawke’s Bay, New Zealand

Robert Walker: Department of Medicine, Otago Medical School, University of Otago, Dunedin, Otago, New Zealand

Deenaz Zaidi: Division of Nephrology and Immunology, Faculty of Medicine and Dentistry, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Alberta, Canada

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Table S1. Burden of chronic kidney disease (CKD) in the International Society of Nephrology–Oceania and South East Asia (ISN OSEA) region.

Supplementary Table S2. Funding for kidney replacement therapy (KRT) in the International Society of Nephrology–Oceania and South East Asia (ISN OSEA) region.

Supplementary Table S3. Workforce and kidney replacement therapy (KRT) centers per million population (pmp) for medical kidney care in the International Society of Nephrology–Oceania and South East Asia (ISN OSEA) region.

Supplementary Figure S1. Funding for nondialysis chronic kidney disease (CKD; left) care and (right) medications in the International Society of Nephrology–Oceania and South East Asia (ISN OSEA) region.

Supplementary Figure S2. Funding for (left) dialysis and (right) transplant medications in the International Society of Nephrology–Oceania and South East Asia (ISN OSEA) region.

Supplementary Figure S3. Workforce shortages for medical kidney care in the International Society of Nephrology–Oceania and South East Asia (ISN OSEA) region.

References

- 1.Francis A., Abdul Hafidz M.I., Ekrikpo U.E., et al. Barriers to accessing essential medicines for kidney disease in low- and lower middle-income countries. Kidney Int. 2022;102:969–973. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2022.07.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Riaz P., Caskey F., McIsaac M., et al. Workforce capacity for the care of patients with kidney failure across world countries and regions. BMJ Glob Health. 2021;6 doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2020-004014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization South-East Asia. https://www.who.int/southeastasia

- 4.World Health Organization Western Pacific 2023. https://www.who.int/Westernpacific

- 5.Ethier I., Johnson D.W., Bello A.K., et al. International Society of Nephrology Global Kidney Health Atlas: structures, organization, and services for the management of kidney failure in Oceania and South East Asia. Kidney Int Suppl. 2021;11:e86–e96. doi: 10.1016/j.kisu.2021.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Okpechi I.G., Bello A.K., Levin A., Johnson D.W. Update on variability in organization and structures of kidney care across world regions. Kidney Int Suppl. 2024;13:6–11. [Google Scholar]

- 7.The World Bank World development indicators. The world by income and region. https://datatopics.worldbank.org/world-development-indicators/the-world-by-income-and-region.html

- 8.Central Intelligence Agency The world factbook. https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/

- 9.Ashton T., Marshall M.R. The organization and financing of dialysis and kidney transplantation services in New Zealand. Int J Health Care Finance Econ. 2007;7:233–252. doi: 10.1007/s10754-007-9023-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bhargava V., Jasuja S., Tang S.C., et al. Peritoneal dialysis: status report in South and South East Asia. Nephrology (Carlton) 2021;26:898–906. doi: 10.1111/nep.13949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hyodo T., Fukagawa M., Hirawa N., et al. Present status of renal replacement therapy in Asian countries as of 2017: Vietnam, Myanmar, and Cambodia. Ren Replace Ther. 2020;6:65. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Khan B.A., Singh T., Ng A.L.C., et al. Health economics of kidney replacement therapy in Singapore: taking stock and looking ahead. Ann Acad Med Singap. 2022;51:236–240. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lim C.Y., Tan J. Global dialysis perspective: Brunei Darussalam. Kidney360. 2021;2:1027–1030. doi: 10.34067/KID.0002342021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sitprija V. Nephrology in South East Asia: fact and concept. Kidney Int Suppl. 2003;(83):S128–S130. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.63.s83.27.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yang F., Lau T., Luo N. Cost-effectiveness of haemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis for patients with end-stage renal disease in Singapore. Nephrology. 2016;21:669–677. doi: 10.1111/nep.12668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.van der Tol A., Lameire N., Morton R.L., et al. An international analysis of dialysis services reimbursement. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2019;14:84–93. doi: 10.2215/CJN.08150718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bavanandan S., Yap Y.C., Ahmad G., et al. The cost and utility of renal transplantation in Malaysia. Transplant Direct. 2015;1:e45. doi: 10.1097/TXD.0000000000000553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kristina S., Endarti D., Andayani T., et al. Cost of illness of hemodialysis in Indonesia: a survey from eight hospitals in Indonesia. Int J Pharm Res. 2020;13:2815–2820. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vareesangthip K., Deerochanawong C., Thongsuk D., et al. Cost-utility analysis of dapagliflozin as an add-on to standard of care for patients with chronic kidney disease in Thailand. Adv Ther. 2022;39:1279–1292. doi: 10.1007/s12325-021-02037-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ying T., Tran A., Webster A.C., et al. Screening for asymptomatic coronary artery disease in waitlisted kidney transplant candidates: a cost-utility analysis. Am J Kidney Dis. 2020;75:693–704. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2019.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nephrology Society of Thailand Thailand renal replacement therapy: year 2016–2019. https://www.nephrothai.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/1.TRT-Annual-report-2016-2019.pdf [in Thai]

- 22.Australia and New Zealand Dialysis and Transplant Registry (ANZDATA) ANZDATA 43rd annual report 2020 (data to 2019) https://www.anzdata.org.au/report/anzdata-43rd-annual-report-2020-data-to-2019/

- 23.United States Renal Data System . National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, Bethesda, MD; 2019. 2019 USRDS Annual Data Report. Accessed April 8, 2022. https://www.niddk.nih.gov/about-niddk/strategic-plans-reports/usrds/prior-datareports/2019. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jain A.K., Blake P., Cordy P., et al. Global trends in rates of peritoneal dialysis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012;23:533–544. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2011060607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Health Promotion Board National Registry of Diseases Office Singapore Renal Registry: annual report 2021. https://www.nrdo.gov.sg/docs/librariesprovider3/default-document-library/srr-annual-report-2021.pdf?sfvrsn=7bbef4a_0

- 26.WHO-ONT Global Observatory on Donation and Transplantation. http://www.transplant-observatory.org/data-charts-and-tables/

- 27.Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME) and Global Health Data Exchange Global Burden of Disease (GBD) study 2019 results. https://vizhub.healthdata.org/gbd-results/

- 28.Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation and Global Health Data Exchange Global expected health spending 2019–2050. https://ghdx.healthdata.org/record/ihme-data/global-expected-health-spending-2019-2050

- 29.Krishnan A., Chandra Y., Malani J., et al. End-stage kidney disease in Fiji. Intern Med J. 2019;49:461–466. doi: 10.1111/imj.14108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jamaluddin J., Mohamed-Yassin M.S., Jamil S.N., et al. Frequency and predictors of inappropriate medication dosages for cardiovascular disease prevention in chronic kidney disease patients: a retrospective cross-sectional study in a Malaysian primary care clinic. Heliyon. 2023;9 doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e14998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bharati J., Jha V. Global Kidney Health Atlas: a spotlight on the Asia-Pacific sector. Kidney Res Clin Pract. 2022;41:22–30. doi: 10.23876/j.krcp.21.236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ichiho H.M., Anson R., Keller E., et al. An assessment of non-communicable diseases, diabetes, and related risk factors in the Federated States of Micronesia, State of Pohnpei: a systems perspective. Hawaii J Med Public Health. 2013;72(5 suppl 1):49–56. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ichiho H.M., Roby F.T., Ponausuia E.S., et al. An assessment of non-communicable diseases, diabetes, and related risk factors in the territory of American Samoa: a systems perspective. Hawaii J Med Public Health. 2013;72(5 suppl 1):10–18. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.LaMonica L.C., McGarvey S.T., Rivara A.C., et al. Cascades of diabetes and hypertension care in Samoa: identifying gaps in the diagnosis, treatment, and control continuum—a cross-sectional study. Lancet Reg Health West Pac. 2022;18 doi: 10.1016/j.lanwpc.2021.100313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tafuna'i M., Matalavea B., Voss D., et al. Kidney failure in Samoa. Lancet Reg Health West Pac. 2020;5 doi: 10.1016/j.lanwpc.2020.100058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Paulino Y.C., Ada A., Dizon J., et al. Development and evaluation of an undergraduate curriculum on non-communicable disease research in Guam: The Pacific Islands Cohort of College Students (PICCS) BMC Public Health. 2021;21:1994. doi: 10.1186/s12889-021-12078-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Talbot B. Global dialysis perspective: Fiji. Kidney360. 2022;3:164–167. doi: 10.34067/KID.0005652021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.George C., Mogueo A., Okpechi I., et al. Chronic kidney disease in low-income to middle-income countries: the case for increased screening. BMJ Glob Health. 2017;2 doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2016-000256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mills K.T., Xu Y., Zhang W., et al. A systematic analysis of worldwide population-based data on the global burden of chronic kidney disease in 2010. Kidney Int. 2015;88:950–957. doi: 10.1038/ki.2015.230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lunney M., Bello A.K., Levin A., et al. Availability, accessibility, and quality of conservative kidney management worldwide. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2020;16:79–87. doi: 10.2215/CJN.09070620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Brown E.A., Johansson L. Epidemiology and management of end-stage renal disease in the elderly. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2011;7:591–598. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2011.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Finkelstein E.A., Ozdemir S., Malhotra C., et al. Identifying factors that influence physicians' recommendations for dialysis and conservative management in Indonesia. Kidney Int Rep. 2016;2:212–218. doi: 10.1016/j.ekir.2016.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tanchanco R., Gueco I., dela Rosa J.A., et al. WCN23-0283 willingness and preparedness of nephrology training institutions in The Philippines to practice conservative kidney management. Kidney Int Rep. 2023;8:S371. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bello A.K., Levin A., Lunney M., et al. Status of care for end-stage kidney disease in countries and regions worldwide: international cross-sectional survey. BMJ. 2019;367:l5873. doi: 10.1136/bmj.l5873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Basu B., Erdmann S., Sander A., et al. Long-term efficacy and safety of rituximab versus tacrolimus in children with steroid dependent nephrotic syndrome. Kidney Int Rep. 2023;8:1575–1584. doi: 10.1016/j.ekir.2023.05.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kashani K., Macedo E., Burdmann E.A., et al. Acute kidney injury risk assessment: differences and similarities between resource-limited and resource-rich countries. Kidney Int Rep. 2017;2:519–529. doi: 10.1016/j.ekir.2017.03.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cerdá J., Mohan S., Garcia-Garcia G., et al. Acute kidney injury recognition in low- and middle-income countries. Kidney Int Rep. 2017;2:530–543. doi: 10.1016/j.ekir.2017.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Essue B.M., Laba T-L, Knaul F., et al. In: Disease Control Priorities: Improving Health and Reducing Poverty. 3rd ed. Jamison D.T., Gelband H., Horton S., et al., editors. International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank; 2017. Chapter 6. Economic burden of chronic ill health and injuries for households in low- and middle-income countries. . Accessed March 1, 2024. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK525297/#top. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ng M.S.Y., Charu V., Johnson D.W., et al. National and international kidney failure registries: characteristics, commonalities, and contrasts. Kidney Int. 2022;101:23–35. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2021.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Talbot B., Athavale A., Jha V., et al. Data challenges in addressing chronic kidney disease in low- and lower-middle-income countries. Kidney Int Rep. 2021;6:1503–1512. doi: 10.1016/j.ekir.2021.03.901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Perkovic V., Craig J.C., Chailimpamontree W., et al. Action plan for optimizing the design of clinical trials in chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int Suppl. 2017;7:138–144. doi: 10.1016/j.kisu.2017.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dorota A.D., Steven Y.C.T., Jennifer R., et al. Registry randomised trials: a methodological perspective. BMJ Open. 2023;13 doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2022-068057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Greenham L., Bennett P.N., Dansie K., et al. The Symptom Monitoring with Feedback Trial (SWIFT): protocol for a registry-based cluster randomised controlled trial in haemodialysis. Trials. 2022;23:419. doi: 10.1186/s13063-022-06355-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.