Abstract

Simple Summary

Incidence and mortality rates for prostate cancer remain high due to advanced disease characterized by the heterogeneous activation of numerous molecular pathways. In the current study, utilizing a genetic mouse model of advanced prostate cancer with hyperactivated metastasis-associated protein 1/mammalian target of rapamycin (MTA1/mTOR) tumor-promoting pathway, we show for the first time that gnetin C, a natural compound from the melinjo plant, blocks the progression of prostate cancer by reducing cell proliferation and angiogenesis and promoting cell death through the efficient targeting of the MTA1/mTOR pathway. These data may provide a foundation from which to explore gnetin C as a monotherapy and/or combination therapy with approved drugs against advanced prostate cancer in patients with a loss of phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN) expression and activated MTA1/mTOR signaling.

Abstract

The metastasis-associated protein 1/protein kinase B (MTA1/AKT) signaling pathway has been shown to cooperate in promoting prostate tumor growth. Targeted interception strategies by plant-based polyphenols, specifically stilbenes, have shown great promise against MTA1-mediated prostate cancer progression. In this study, we employed a prostate-specific transgenic mouse model with MTA1 overexpression on the background of phosphatase and tensin homolog (Pten) null (R26MTA1; Ptenf/f) and PC3M prostate cancer cells which recapitulate altered molecular pathways in advanced prostate cancer. Mechanistically, the MTA1 knockdown or pharmacological inhibition of MTA1 by gnetin C (dimer resveratrol) in cultured PC3M cells resulted in the marked inactivation of mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) signaling. In vivo, mice tolerated a daily intraperitoneal treatment of gnetin C (7 mg/kg bw) for 12 weeks without any sign of toxicity. Treatment with gnetin C markedly reduced cell proliferation and angiogenesis and promoted apoptosis in mice with advanced prostate cancer. Further, in addition to decreasing MTA1 levels in prostate epithelial cells, gnetin C significantly reduced mTOR signaling activity in prostate tissues, including the activity of mTOR-target proteins: p70 ribosomal protein S6 kinase (S6K) and eukaryotic translational initiation factor 4E (elF4E)-binding protein 1 (4EBP1). Collectively, these findings established gnetin C as a new natural compound with anticancer properties against MTA1/AKT/mTOR-activated prostate cancer, with potential as monotherapy and as a possible adjunct to clinically approved mTOR pathway inhibitors in the future.

Keywords: natural products, plant-derived polyphenols, gnetin C, targeted therapeutics, anticancer effects, MTA1/mTOR, advanced prostate cancer

1. Introduction

Prostate cancer patients are a heterogeneous group with a prognosis ranging from full recovery to malignant and lethal disease. Between 2007 and 2014, the number of prostate cancers diagnosed declined due to changes in screening recommendations concerning the detection of prostate-specific antigen. Consequently, the incidence rate for advanced stage prostate cancer has increased by about 5% per year [1]. Therefore, an urgent need exists to better understand the biological basis for the progression to aggressive disease and metastasis. Prostate tumors begin from preinvasive lesions such as prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia (PIN), which eventually progress to adenocarcinoma and, in some cases, metastatic disease. Different phases of prostate cancer are characterized by a distinct molecular makeup, during which various signaling pathways are activated. While androgen receptor (AR) signaling is considered the most critical pathway in hormone-sensitive disease, hormone-refractory tumors, which emerge after failing hormone deprivation therapy, are governed by the activation of other tumor-promoting networks, such as the phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN) loss of function-associated activation of the protein kinase B/mammalian target of rapamycin (AKT/mTOR) cell survival signaling pathway [2,3,4,5,6,7]. Yet another pathway having major implications in advanced prostate cancer is metastasis-associated protein 1 (MTA1) signaling, which is strongly associated with clinically aggressive prostate cancer [8,9]. We have previously reported increased levels of MTA1 in Pten-deficient and Pten-loss mouse models of prostate cancer, which affected downstream inflammation and cell survival pathways [10]. Our initial finding that reduced levels of MTA1 were inversely correlated with PTEN acetylation and activation, which resulted in significantly inhibited disease progression partly through the inhibition of p-AKT, revealed a novel deregulated signaling network in prostate cancer: the MTA1/PTEN/AKT pathway [10,11]. Furthermore, our recent studies in a mouse model of premalignant high-risk prostate cancer (R26MTA; Pten+/f; Pb-Cre+) demonstrated that targeting the MTA1/PTEN/AKT signaling pathway by diets supplemented with natural stilbenes, such as pterostilbene and gnetin C (dimer resveratrol), was effective in preventing prostate cancer progression from high-grade PIN to adenocarcinoma [12,13].

Despite significant advances in developing pharmacological inhibitors of PI3K/AKT/mTOR kinases, the results from clinical trials in prostate cancer demonstrated severe toxicity [14] and a lack of clinical benefit [15]. In the last two decades, there has been much interest in the potential health benefits of plant-based natural polyphenols as anti-inflammatory and anticancer agents [16,17,18]. Different classes of polyphenols have been shown to have anticancer effects through numerous signaling pathways including PI3K/AKT/mTOR [19,20,21]. Our group systematically reported on MTA1-mediated anticancer effects by members of the stilbene family of polyphenols, namely resveratrol, pterostilbene, and gnetin C [10,22]. We recently demonstrated gnetin C as a preclinical tumor growth inhibitor in prostate cancer xenografts and as a dietary interceptive agent in a transgenic mouse model of prostate cancer [13,23]. Based on our previous findings, we hypothesized that gnetin C might be effective as an MTA1-targeted therapeutic agent against advanced prostate cancer. Two major advantages will be gained: (1) new biomarkers such as MTA1 involved in the AKT/mTOR pathway may allow for the selection of a subpopulation of patients more likely to benefit from inhibitors of specific pathways that do not alter kinase activity; (2) safe natural compounds with the ability to inhibit this pathway through MTA1 may provide the rationale for novel combination approaches with low toxicity.

In the current study, we sought to (1) establish a genetically engineered mouse model which recapitulates advanced prostate cancer due to prostate-specific MTA1 overexpression and the loss of PTEN expression (R26MTA1; Ptenf/f; Pb-Cre+, hereafter R26MTA1; Ptenf/f); (2) identify downstream pathways associated with an overexpression of MTA1 in PTEN-loss tumors and examine how these pathways contribute to the cooperative promotion of cancer progression; and (3) investigate the targeted efficacy of gnetin C on MTA1 downstream signaling in vivo.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Reagents and Cell Culture

Gnetin C was a generous gift from Hosoda SHC Co., Ltd. (Fukui, Japan). For in vitro and in vivo experiments, gnetin C was dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO, final concentration 0.1% for in vitro and 10% for in vivo) and stored in the dark at −20 °C until use.

PC3M cells were a gift from Dr. R. Bergman (University of Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha, NE, USA). PC3M cells were cultured in RPMI-1640 media containing 10% fetal bovine serum in an incubator at 37 °C with 5% CO2. MTA1 knockdown PC3M cells were generated as described previously [24] using three different shRNAs and selecting clone #3 for demonstrating the most efficient knockdown for the current study (Supplementary Figure S1). Cells were certified as being mycoplasma-free using the Universal Mycoplasma Detection Kit (ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA).

2.2. RNA Sequencing

Prostate tissues of 18-week-old mice from the following four genotypes were used for RNA-Seq: (1) R26MTA1; Pb-Cre− (WT); (2) R26MTA1; Pb-Cre+ (MTA1 OE); (3) Ptenf/f; Pb-Cre+ (Pten-null); and (4) R26MTA1; Ptenf/f; Pb-Cre+ (Pten-null MTA1 OE). Genotypes were confirmed by PCR-based tail genomic DNA genotyping using primers previously described [12]. The total RNA was isolated using the miRNeasy Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) and sent to LC Sciences (Houston, TX, USA) for RNA sequencing. RNA-Seq libraries were generated from two biologically independent replicates per genotype (described above). The obtained sequencing reads were aligned to the GRCm39 mouse reference transcriptome from the Ensembl genome database (https://www.ensembl.org, accessed on 22 March 2023) and transcript abundance was aggregated to gene-level count using biomaRt (Bioconductor R-package, https://www.bioconductor.org/, accessed on 22 March 2023). Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) among the groups were identified using DESeq2 [25] and were defined using a cutoff of FDR < 0.05 and absolute log2 fold change set at 1. To determine the underlying potential signaling pathways enriched among groups, the DEGs were compared with gene sets curated in the Molecular Signatures Database (MSigDB) [26] for the “Hallmark gene sets” collection with FDR < 0.05 for multiple comparisons.

2.3. Western Blot Analysis

Protein lysates from cells and prostate tissues were separated using 6%, 10%, or 15% polyacrylamide gels and transferred onto polyvinylidene difluoride membranes as described previously [13]. Membranes were probed with primary antibodies for MTA1, AKT, p-AKTSer473, mTOR, p-mTORS2448, p-S6KT389, p-4EBP1, and CyclinD1 from Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA, USA. β-actin and HSP70 were used as loading controls (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX, USA) (Supplementary Table S1). Signals were detected on ChemiDoc (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) using enhanced chemiluminescence (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Somerset, NJ, USA). Densitometry was performed using Image J, v 1.54h (NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA). Quantitation was carried out using the ratio of the intensity of the phosphorylated protein to the total protein of interest versus loading control.

2.4. Animals and Study Design

All mice were housed in a pathogen-free facility, and all procedures were performed in accordance with policies and guidelines outlined by the Long Island University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC, approved protocol ID # 2022-011, 10 March 2022). Mice had free access to drinking water and food and were monitored daily for their general health.

Mouse Models: Mice with biallelic overexpression of MTA1 in the prostate (R26MTA1; Pb-Cre+) have been described previously by us [12]. R26MTA1; Pb-Cre+ mice then interbred with C57BL/6J mice homozygous for the “floxed” allele of Pten gene (Ptenf/f) (Jackson Laboratories, Nashville, TN, USA) to obtain R26MTA1; Pten+/f; Pb-Cre+ [12,13] and R26MTA1; Ptenf/f; Pb-Cre+ male mice (hereafter R26MTA1; Ptenf/f) for this study. Tail genotyping was performed using the following primers: MTA1 F: 5′-GCT GCT CTC ATC CTC AGA AAC C-3′; MTA1 R: 5′-CTC GAT GTT GTG GCG GAT CTT GAA GTT-3′ with a band of 715 bp; PTEN F: 5′-CAA GCA CTC TGC GAA CTG AG-3′; PTEN R: 5′-AAG TTT TTG AAG GCA AGA TGC-3′ with a wild-type band of 156 bp and mutant band of 328 bp; and Cre F: 5′-TCG CGA TTA TCT TCT ATA TCT TCA G-3′; Cre R: 5′-GCT CGA CCA GTT TAG TTA CCC-3′ with a band of 392 bp [12]. PCR was performed on an Eppendorf thermocycler. R26MTA1; Pb-Cre– mice with normal prostates (n = 3) served as a reference control group.

Experimental Design: Dose calculations: In our previous studies with transgenic mice and pterostilbene i.p. administration, we found that pterostilbene had anticancer effects at 10 mg/kg bw without any toxicity [10]. Given gnetin C’s improved pharmacokinetic profile [27] and its reported safe dose in animal studies [28], we selected a gnetin C dose of 7 mg/kg bw per day. The dose translation formula used for the determination of equivalent human doses (HEDs) [HED (mg/kg) = Animal dose (mg/kg) × Km ratio, where Km = 0.081 for mice] [29] demonstrated clinical relevance at a 7 mg/kg bw dose. This dose translates to 39.69 mg per day (for an average human male of 70 kg bw), which is within the range of doses shown to be well tolerated and safe in human clinical trials with gnetin C [27,30,31,32].

For gnetin C treatment experiments, two groups of R26MTA1; Ptenf/f mice were weaned at 3–4 weeks of age and treated with daily i.p. injections of either 10% DMSO vehicle (control, n = 7) or gnetin C at a 7 mg/kg bw dose (n = 11). The mice received their respective treatment for 5 consecutive days, with 2 days off for a period of 12 weeks. Mice were weighed daily and observed for signs of distress following treatment. At the conclusion of the study, mice were sacrificed in accordance with the approved IACUC protocol. Due to the small size of the mouse prostate, animals from the same treatment group were used either for UGS (prostate, seminal vesicles, and bladder) isolation and fixed in formalin and paraffin-embedded for histology and IHC, or prostate tissue protein extraction stored at −80 °C for Western blot analysis. Blood was collected by cardiac puncture upon sacrifice, and serum samples were stored at −80 °C.

2.5. Histology and Immunohistochemistry Analyses of Prostate Tissues

Formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded sections (Reveal Biosciences, San Diego, CA, USA) were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) for independent histopathologic examination (GC and CY). The severity of prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia (PIN) and adenocarcinoma was scored by a board-certified veterinary pathologist (CY) using the following system: Score 0: No detectable PIN and prostate carcinoma; Score 1: Only PIN is present; Score 2: Both PIN and adenocarcinoma are present, where adenocarcinoma accounts for less than 50% of the prostate gland; Score 3: Both PIN and adenocarcinoma are present, where adenocarcinoma accounts for more than 50% of the prostate gland. A minimum of five random sections from different locations in the prostate tissues were examined for each mouse. The phenotype was scored based on the analyses of multiple sections per mouse.

Slides were subjected to IHC staining using antibodies for Ki67, MTA1, CD31, cleaved caspase 3 (CC3), p-mTOR, p-SK6, and p-4EBP1 (Supplementary Table S1). Briefly, tissues were deparaffinized, hydrated, and treated to exposed target proteins. Active sites were blocked with serum and endogenous peroxidases were quenched. Tissues were incubated in primary antibody overnight, followed by secondary antibody and avidin–biotin complex (Vectastain ABC Elite Kit, Vector Laboratories, Newark, CA, USA). Stain was developed using the ImmPACT DAB kit (Vector Laboratories). Images were taken using an EVOS XL Core microscope (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Somerset, NJ, USA). The staining intensity of the markers was evaluated and scored by GC. The percentage of positive nuclei was evaluated for Ki67. The total nuclear and cytoplasmic staining intensity was scored according to a four-tier system: 1 (weak staining), 2 (fair staining), 3 (moderate staining), and 4 (strong staining). Analyses of IHC staining were performed using at least five randomly selected areas for each sample in each group using Image J, v 1.54h (NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA) or QuPath v 0.5.0 automated bioimage analysis. Image J was used for cell counting and measuring the CD31 endothelial-stained vessel area in mm2. QuPath was used to quantitate the presence and severity of PIN and adenocarcinoma.

2.6. ELISA

The levels of IL-2 in mice sera (50 µL samples) were determined by using a commercially available kit (Abcam, Boston, MA, USA) as previously described [12,13]. Briefly, samples and standards in duplicate wells were incubated with the antibody mix and detected by adding 3,3′, 5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine substrate. The reaction was read at 450 nm using a microplate reader (Tecan, Mannedorf, Switzerland). The concentration of IL-2 in samples was calculated from a standard curve.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism v9 software (San Diego, CA, USA). The statistical significance of differences between groups was determined by either Student’s t-test or one-way ANOVA as appropriate. Data are shown as mean value ± SEM; p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Prostate-Specific MTA1 Overexpression Makes Ptenf/f Mice Progress with Invasive Adenocarcinoma

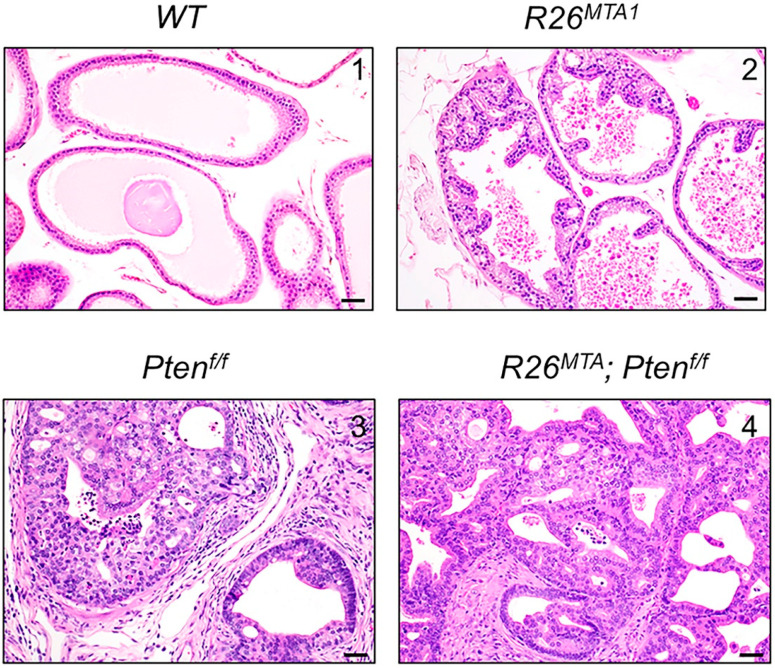

Based on previous studies showing that MTA1 overexpression in the prostate enhances and accelerates PIN development in Pten+/f mice [12,13], we hypothesized that MTA1 overexpression in the context of PTEN loss-of-function (Ptenf/f) would increase the aggressiveness of prostate cancer progression and might even result in metastasis. Therefore, we generated a prostate-specific R26MTA1; Ptenf/f mouse model, in which mice develop PIN that progresses to adenocarcinoma. The number of glands exhibiting adenocarcinoma versus PIN in R26MTA1; Ptenf/f and Ptenf/f mice was comparable. Likewise, the prostate-specific upregulation of MTA1 did not significantly accelerate tumor progression in the context of the loss-of-function of PTEN, and no metastases were found in either renal or iliac lymph nodes of these mice even by 36 weeks of age. Histopathologically, MTA1 overexpression in prostate epithelial cells lacking PTEN expression was characterized by well to moderately differentiated invasive adenocarcinoma composed of neoplastic epithelial cells arranged in glandular structures associated with desmoplasia and variable numbers of inflammatory infiltrates composed of lymphocytes, plasma cells, and neutrophils. There was no evidence of lymphovascular invasion by the neoplastic cells. The neoplastic cells invading the basement membrane did not show a spindle-shaped morphology (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Representative photomicrographs of prostates from four prostate-specific genetic groups: (1) R26MTA1; Pb-Cre-negative (WT), (2) R26MTA1, (3) Ptenf/f, and (4) R26MTA1; Ptenf/f were evaluated using H&E staining (scale bar, 100 µm). The prostate in WT mice is unremarkable (upper left). In R26MTA1 mice, there is an occasional hyperplasia of the prostatic epithelium without nuclear or cellular atypia (upper right). In Ptenf/f and R26MTA1; Ptenf/f mice, both PIN and prostatic adenocarcinoma are observed. The images (lower left and right) show well to moderately differentiated invasive prostatic adenocarcinoma with desmoplasia and inflammatory infiltrates.

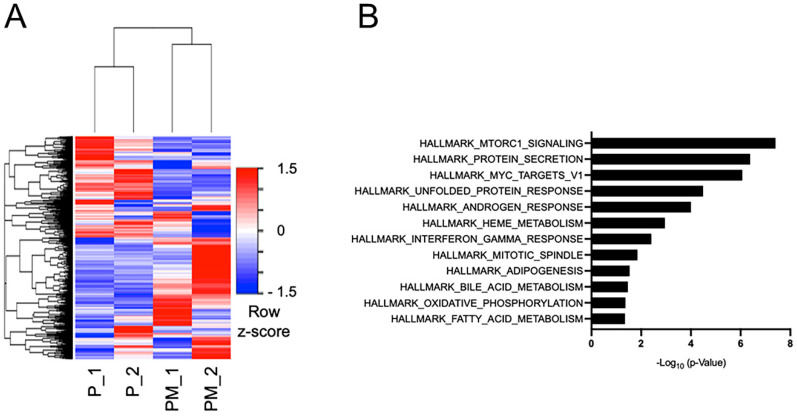

To identify molecular alterations affected by prostate-specific MTA1 overexpression, we performed RNA-Seq using mouse prostate tissues. A total of 867 genes were found to be significantly upregulated and 1088 genes downregulated (FDR < 0.05) in the R26MTA1; Ptenf/f compared to the Ptenf/f group. A heatmap view of the gene clustering of R26MTA1; Ptenf/f compared to Ptenf/f is shown in Figure 2A (Supplementary Table S2). The pathway most affected by MTA1 overexpression in the PTEN-loss prostate was the mTORC1 (hereafter mTOR) pathway (Figure 2B, Supplementary Table S3), which is known to be aberrantly activated in castration-resistant prostate cancer [33] and advanced prostate cancer with a reduced expression of PTEN [14]. The Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and Multidimensional Scaling (MDS) scatter plot are shown in Supplementary Figure S2. Therefore, our R26MTA1; Ptenf/f mice mimic a subtype of advanced prostate cancer that exhibits the involvement of mTOR signaling, suggesting that targeting the MTA1/mTOR pathway by natural stilbene gnetin C could be an effective means for blocking prostate cancer progression.

Figure 2.

(A) Heatmap showing DEGs in the R26MTA1; Ptenf/f (PM_1 and PM_2) compared to the Ptenf/f; (P_1 and P_2) group. (B) Gene set enrichment analysis for the Hallmark gene sets from MSigDB for the DEGs in the R26MTA1; Ptenf/f compared to the Ptenf/f group.

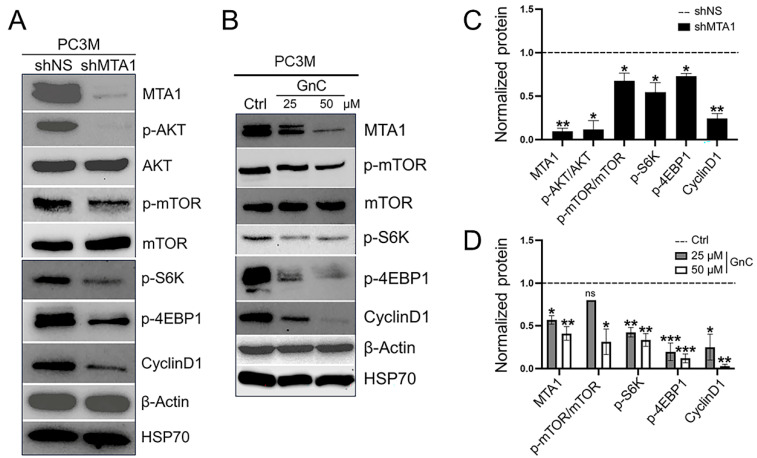

3.2. Inhibition of MTA1/mTOR Pathway by Gnetin C in Cell Culture

To gain initial insights regarding the mechanistic basis for targeting the MTA1/mTOR pathway, we first investigated the link between MTA1 and mTOR signaling in PC3M prostate cancer cells, which are known to have a PTEN-null status [34] and the highest MTA1 expression of all prostate cancer cell lines [8]. Oncogenic signaling via the AKT/mTOR pathway is mediated through both mTORC1 and mTORC2, with mTORC1 regulating cell growth by controlling the activity of p70 ribosomal protein S6 kinase (S6K) and eukaryotic translational initiation factor 4E (elF4E)-binding protein 1 (4EBP1), while mTORC2 phosphorylates AKT to promote cell survival [14,35]. Further, the activated mTOR pathway which results in phosphorylated 4EBP1 and S6K leads to higher levels of CyclinD1 [36,37,38], while the inhibition of PI3K/AKT/mTOR/S6K leads to decreased CyclinD1 expression in cancer cells [38,39].

A Western blot analysis of mTOR signaling revealed the marked downregulation of the p-AKT and p-mTOR pathway and its downstream target substrates p-S6K and p-4EBP1 as well as CyclinD1 in PC3M MTA1 knockdown cells compared to control NS cells, indicating that MTA1 acts as an upstream regulator of the mTOR pathway (Figure 3A,C). These data suggest that the MTA1-dependent activation of the mTOR/S6K/4EBP1/CyclinD1 pathway may represent a mechanism through which prostate cancer progresses under conditions of PTEN loss, which suggests a direct positive crosstalk between the MTA1 and mTOR pathway independent of the MTA1/PTEN link [11]. Gnetin C, which previously showed cytotoxicity in PC3M cells with IC50 = 8.7 µM [26,27], pharmacologically inhibited MTA1 and reduced the expression of p-mTOR, p-S6K, p-4EBP1, and CyclinD1 (Figure 3B,D) indicating the efficacy of gnetin C for suppressing the MTA1/mTOR pathway.

Figure 3.

(A) Representative Western blot analysis and quantitation of molecular markers of MTA1/mTOR signaling pathway in PC3M MTA1-expressing (shNS) and MTA1 knockdown (shMTA1) cells. (B) Gnetin C inhibits MTA1/mTOR pathway markers in a dose-dependent manner. β-actin and HSP70 were used as loading controls. (C) Quantitation analysis of molecular markers in PC3M shNS and shMTA1 cells. (D) Quantitation analysis of molecular markers in PC3M cells treated with 25 and 50 µM of gnetin C (GnC). Quantitation represents mean ± SEM of three independent experiments. * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001; ns, non-significant (Student’s t-test and one-way ANOVA). The uncropped blots are shown in File S1.

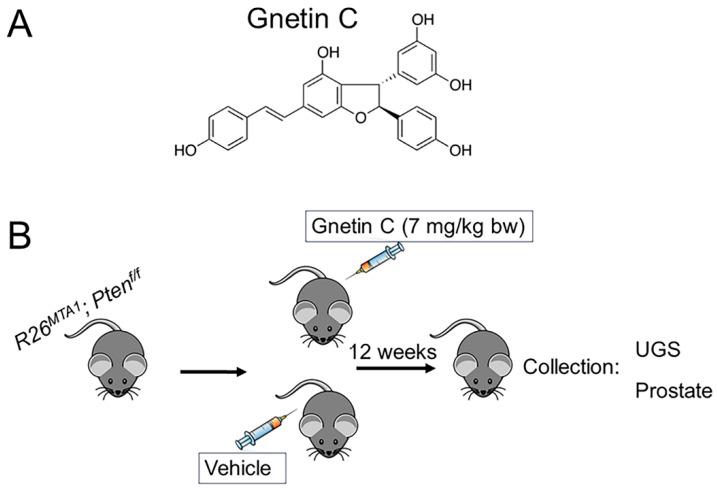

3.3. Gnetin C Treatment Diminishes Adenocarcinoma Progression in R26MTA1; Ptenf/f Mice

Upon the accumulation of 18 R26MTA1; Ptenf/f mice, we randomized 4-week-old mice into two groups: mice treated by intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection with vehicle (n = 7) or 7 mg/kg bw gnetin C (GnC, n = 11) for 12 weeks. Mice were sacrificed in week 13, and prostate tissues and blood were collected for analysis (Figure 4). We also had Cre-negative mice serving as the reference control. Body weight and health condition were monitored. No signs of toxicity were identified.

Figure 4.

(A) Chemical structure of gnetin C. (B) Schematic of experimental design used for studying therapeutic effects of gnetin C in advanced prostate cancer murine model. R26MTA1; Ptenf/f mice were treated with vehicle (n = 7) or single daily dose of gnetin C (7 mg/kg bw), (n = 11) for 12 weeks, after which UGS or prostate tissues were collected for histopathological and molecular analysis, respectively.

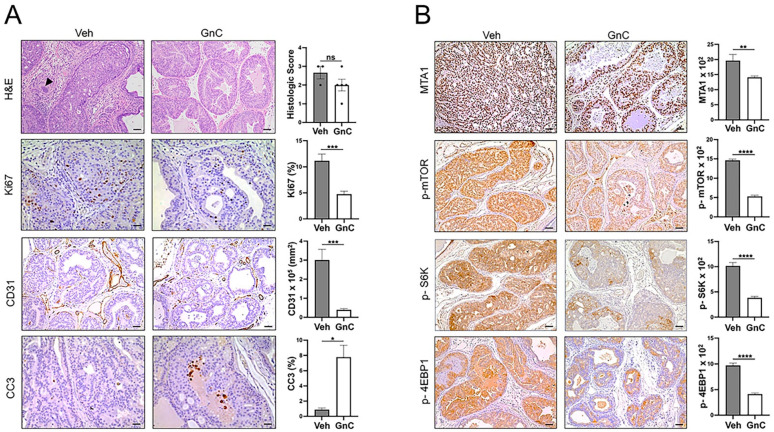

Figure 5A (upper panel) shows that in the vehicle-treated group, mice predominantly exhibited adenocarcinoma characterized by the proliferation of the neoplastic glandular epithelium with the invasion of the basement membrane surrounded by desmoplastic reaction and moderate-to-large numbers of infiltrating inflammatory cells composed of neutrophils, lymphocytes, and plasma cells. There is no evidence of lymphovascular invasion by the neoplastic cells. The neoplastic cells invading the basement membrane did not show a spindle-shaped morphology. In contrast, mice treated with gnetin C demonstrated more areas of PIN characterized by the proliferation of glands without the invasion of the basement membrane into surrounding stroma and rare inflammatory cells. The IHC analysis of prostate tissues of mice treated with gnetin C showed a significantly reduced number of Ki67-positive cells and CD31 staining, indicating a significant decrease in proliferation and angiogenesis compared to vehicle-treated mice. Further, we detected increased apoptosis (CC3 staining) in prostates of mice treated with gnetin C compared to vehicle-treated mice (Figure 5A). We next explored the therapeutic potential of gnetin C in inhibiting the MTA1/mTOR pathway. Our finding revealed a significant decrease in MTA1 and the activated mTOR pathway (p-mTOR, p-S6K, and p-4EBP1) in mice treated with gnetin C compared to the vehicle-treated group (Figure 5B).

Figure 5.

(A) Left: Representative images of H&E (scale bar, 50 µm). An island of neoplastic epithelial cells invading the adjacent fibrous connective tissue is present (arrowhead). The IHC staining of Ki67, CC3 (scale bar, 20 µm), and CD31 (scale bar, 50 µm) in the prostate tissues from vehicle-treated and gnetin C-treated mice. Right: The quantitation of prostate glands involved in PIN vs. adenocarcinoma and the quantitation analysis of Ki67, CD31, and CC3 staining. (B) Left: Representative images of molecular markers of the MTA1/mTOR pathway in the prostate tissues from vehicle (Veh)-treated and gnetin C (GnC)-treated mice. Right: The quantitation of MTA1, p-mTOR, p-S6K, and p-4EBP1 (scale bar, 50 µm) staining. Values are mean ± SEM analyzed from five to seven separate areas per sample (Veh, n = 3 and GnC, n = 5). * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001; **** p < 0.0001; ns, non-significant (Student’s t-test).

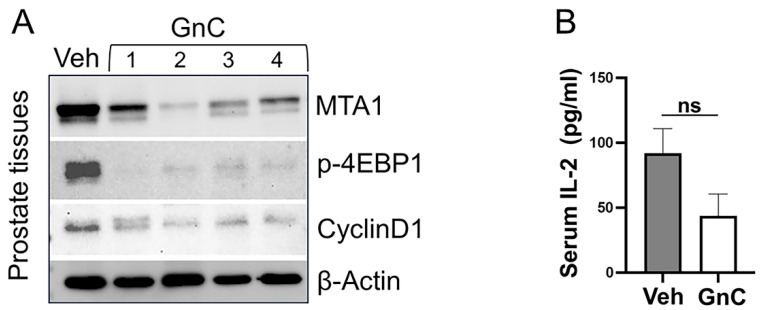

For further analysis, we evaluated the response to treatments by measuring levels of MTA1/mTOR pathway markers in prostate tissue lysates by Western blot (Figure 6A). Although demonstrating noticeable heterogeneity, MTA1 and associated activated mTOR-downstream targets (p-4EBP1 and CyclinD1) levels were significantly downregulated in the prostates of mice treated with gnetin C compared to the vehicle-treated group (Figure 6A). Curiously, the results of p-mTOR and mTOR levels in prostate tissues detected by Western blot were not associated with treatment benefits. This can be explained in part by the very low number of prostate tissues for our Western blot analysis but could also reflect the contradictory role of p-mTOR/mTOR found in prostate cancer patients whose elevated levels positively correlated with a favorable prognosis [40,41]. Existing ambiguity surrounding the biological role of p-mTOR/mTOR in prostate cancer could explain the limited clinical efficacy of PI3K/AKT/mTOR inhibitors [14,40,41]. Nevertheless, the inclusion of MTA1, p-4EBP1, and CyclinD1 in clinical studies may help select patients with high levels of MTA1 that are likely to benefit from gnetin C-targeted therapies.

Figure 6.

(A) Representative immunoblot images of the inhibitory effect of gnetin C (GnC) on molecular markers of the MTA1/mTOR pathway in the prostate tissues from mice in different treatment groups. β-actin was used as a loading control. (B) The effect of GnC on circulating IL-2 cytokine levels measured by ELISA in murine sera (n = 4 per group). Data represent the mean ± SEM of three independent experiments performed in duplicate. ns, non-significant. Veh, vehicle. The uncropped blots are shown in File S1.

Finally, we evaluated the anti-inflammatory response to gnetin C treatment in R26MTA1; Ptenf/f mice by determining the levels of pro-inflammatory IL-2 cytokine in murine sera (Figure 6B). Consistent with our previous observations using low doses of a gnetin C-supplemented diet in a high-risk PIN model of prostate cancer [13], our current study demonstrated that gnetin C was able to reduce the levels of IL-2 compared to the vehicle.

Taken together, our data demonstrated that gnetin C treatment restored favorable histopathology in R26MTA1, Ptenf/f mice with a statistically significant reduction in MTA1, accompanied by a reduced rate of cell proliferation and angiogenesis, increased levels of apoptosis, and the inhibition of MTA1-associated markers of activated mTOR signaling, as evidenced by IHC and Western blot analysis. These results suggest that gnetin C has several potent beneficial features, including anti-inflammatory and anticancer properties, defining its therapeutic efficacy in a preclinical mouse model of advanced prostate cancer.

4. Discussion

Although mTOR inhibitors are effective in many cancers [42,43,44], they have shown limited efficacy in the treatment of prostate cancer [14,45,46]. In addition, mTOR inhibitor-associated toxicity is a critical problem dictating the need for effective and safe targeted therapies [14,44].

In this study, to discover a novel natural mTOR pathway inhibitor in prostate cancer, we have established a clinically relevant mouse model to test the efficacy of gnetin C-targeted therapy. The prostate-specific R26MTA1; Ptenf/f genetically engineered mouse model recapitulates features of PTEN-loss advanced prostate cancer facilitated by the overexpression of MTA1.

In our previous studies of MTA1-associated prostate cancer progression, we found an inverse relationship between MTA1 overexpression and PTEN activation, which resulted in an aberrant activation of the AKT signaling pathway [10,11]. In the current study, we have investigated a direct link between the MTA1 and AKT kinase downstream effector, e.g., the mTOR signaling pathway, and found that MTA1 is an upstream regulator of mTOR that is independent of PTEN. Reassuringly, the same association between MTA1 and AKT/mTOR/4EBP1 was recently reported in endometrial cancer, in which miR-30c/MTA1 axes regulated cell proliferation, migration, and invasion via AKT/mTOR signaling defining MTA1 as a therapeutic target in endometrial cancer [47]. Importantly, for the first time, we have pharmacologically targeted the MTA1/mTOR pathway using the natural compound gnetin C both in vitro and in vivo. We report here that gnetin C effectively suppressed the MTA1/mTOR pathway indicated by the downregulated MTA1 and the associated reduced phosphorylation of AKT, mTOR, S6K, 4EBP1, and CyclinD1 in PC3M prostate cancer cells. In prostate tissues, despite the limitations due to a small number of samples, gnetin C showed a significant inhibition of MTA1 and associated p-4EBP1 and CyclinD1. Considering the intricacy of the mTOR signaling network in prostate cancer, it is understandable that preclinical studies would also reflect this complexity. Hence, it becomes important then that there are other biomarkers associated with mTOR that can be indicators of therapy response. Notably, targeting MTA1 by gnetin C consistently resulted in the downregulation of the activated mTOR pathway response markers p-S6K, p-4EBP1, and CyclinD1 detected either by IHC or Western blot analysis. Our data agree with previously reported gnetin C activity on AKT/mTOR signaling in leukemia cells, in which gnetin C’s antitumor effects are demonstrated in cancer cell lines, patient samples, and in vivo through AKT/mTOR and ERK1/2 pathways. This study demonstrated that a combination of gnetin C with low doses of chemotherapeutic drugs leads to a synergistic antitumor effect against acute myeloid leukemia [28].

In the future, modifications of the chemical structure of gnetin C with improved pharmacokinetics could expand therapeutic outcomes when used as monotherapy. Moreover, gnetin C or its derivatives, with their chemosensitizing ability, could be used in combination with clinically approved drugs for synergistic efficacy. We recently demonstrated that gnetin C acts synergistically with enzalutamide to inhibit cell proliferation and angiogenesis and to promote apoptosis in a castrate-resistant xenograft model by the dual-targeting of AR-V7 and MTA1 [48]. While specific MTA1 inhibitors are not available, mTOR inhibitors such as rapamycin and its derivatives are commercially available and suitable for combination therapy in a reduced dose. Therefore, in the future, combinatorial targeted therapies can be beneficial to a biomarker-selected subpopulation of patients with MTA1/mTOR activation-mediated advanced prostate cancer. Further investigations are warranted to determine how MTA1-tumor heterogeneity impacts the effectiveness of treatment and whether target phospho-protein levels can be used as reliable biomarkers for combinatorial treatment response.

5. Conclusions

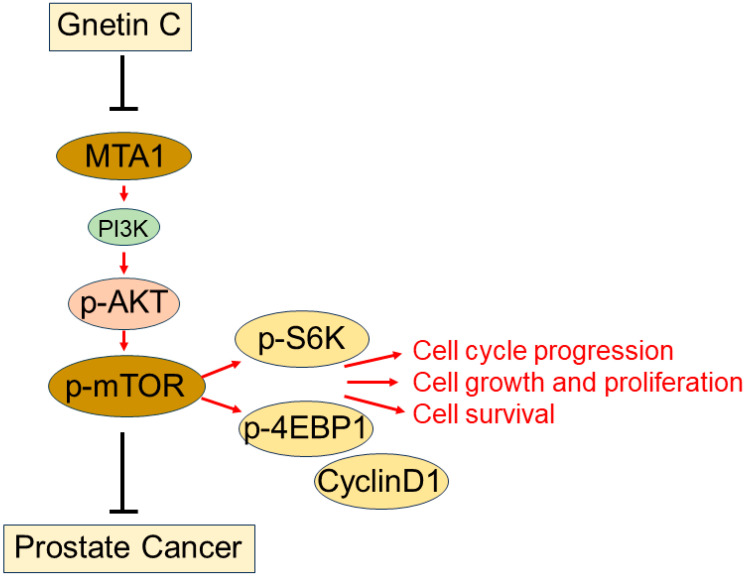

We conclude that R26MTA1; Ptenf/f mice recapitulate key features of MTA1/mTOR signaling pathway activation-associated advanced prostate cancer and represent a useful model for exploring novel therapeutic approaches to manage advanced disease. The discovery of a new mTOR inhibitor with decent efficacy and low toxicity increases the translational potential of the MTA1/mTOR pathway as a therapeutic target. Collectively, our data show that targeting the MTA1/mTOR pathway by the natural stilbene, gnetin C, is highly effective in a preclinical model of prostate cancer and suggests that it could be beneficial for blocking prostate cancer progression in a cohort of patients with a deregulated MTA1/PTEN/AKT/mTOR pathway (Figure 7). Novel natural compounds, such as gnetin C, that target specific biological pathways represent the future for the clinical management of advanced prostate cancer.

Figure 7.

Schematic representation of MTA1/mTOR pathway in prostate cancer. MTA1 overexpression in R26MTA1; Ptenf/f preclinical model of prostate cancer leads to hyperactivation of mTOR resulting in phosphorylation of downstream target proteins such as S6K and 4EBP1 and CyclinD1. These changes promote cell growth, proliferation, and survival. Gnetin C, plant-derived stilbene, inhibits MTA1-associated mTOR pathway activation resulting in antitumor activity.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to S. Yoo and J. Zhu (Icahn School of Medicine, Mount Sinai, NY, USA) for their assistance with the RNA-Seq data analysis. The authors also thank Dicky Gunawan, Hosoda SHC Co., Ltd., Fukui, Japan for providing gnetin C for this study and students in the lab for their contribution.

Abbreviations

| AKT | v-akt murine thymoma viral oncogene (protein kinase B) |

| ANOVA | Analysis of variance |

| AR | Androgen receptor |

| bw | Body weight |

| CC3 | Cleaved caspase 3 |

| CD31 | Cluster of differentiation 31 |

| CRPC | Castration-resistant prostate cancer |

| DEGs | Differentially expressed genes |

| DMSO | Dimethyl sulfoxide |

| Ctrl | Control |

| ELISA | Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay |

| ERK1/2 | Extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 |

| FDR | False discovery rate |

| GAPDH | Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase |

| f/f | Pten gene flanked by two loxP sites in each allele |

| GnC | gnetin C |

| GRCm39 | Genome reference consortium mouse build 39 |

| H&E | Hematoxylin and eosin |

| HED | Human equivalent dose |

| HSP70 | Heat shock protein 70 |

| IACUC | Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee |

| IHC | Immunohistochemistry |

| IL-2 | Interleukin 2 |

| i.p. | Intraperitoneal |

| Ki67 | Cellular protein marker of proliferation |

| LIU | Long Island University |

| mTOR | mammalian target of rapamycin |

| ns | Non-significant |

| NS | Non-silenced |

| OE | Overexpression |

| p-AKTS473 | Phosphorylation of serine 473 in C-terminus of AKT |

| p-4EBP1 | Phosphorylated eukaryotic translational initiation factor 4E (elF4E)-binding protein 1 |

| p-S6K | Phosphorylated p70 ribosomal protein S6 kinase |

| p-mTOR | Phosphorylated mammalian target of rapamycin |

| Pb-Cre+ | Probasin promoter directing expression of epithelial Cre recombinase |

| PC3M | Human prostate cancer cell line |

| PCR | Polymerase chain reaction |

| PI3K | Phosphoinositide 3-kinase |

| PIN | Prostate intraepithelial neoplasia |

| PTEN | Phosphatase and tensin homolog |

| Pten+/f | Pten heterozygous mice |

| Ptenf/f | Pten homozygous, Pten-null |

| qRT-PCR | Quantitative reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction |

| RNA | Ribonucleic acid |

| RPMI-1640 | Roswell Park Memorial Institute 1640 cell culture media |

| R26 | Rosa26 loci in the mouse genome |

| SEM | Standard error of mean |

| shMTA1 | short hairpin MTA1 |

| shNS | short hairpin non-silence |

| UGS | Urogenital system |

| WT | Wild-type |

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/cancers16071344/s1, Figure S1: Validation of MTA1 knockdown in PC3M cells; Figure S2: PCA and MDS scatter plot of gene expression; Table S1: Antibodies used for western blot and IHC; Table S2: Hallmark gene sets; Table S3: Heatmap-PMvP; File S1: Western blot information.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.S.L.; methodology, A.K., G.C., E.F., P.P., L.S.D., C.Y., and A.S.L.; formal analysis, G.C., C.Y., A.K., E.F., and A.S.L.; investigation, G.C., P.P., E.F., and L.S.D.; resources, A.K. and A.S.L.; writing—original draft preparation, A.S.L.; writing—review and editing, G.C., C.Y., A.K., and A.S.L.; visualization, G.C., A.K., C.Y., and A.S.L.; supervision, A.K. and A.S.L.; data curation, A.S.L., project administration, A.S.L., funding acquisition, A.S.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The animal study protocol was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Long Island University Brooklyn (ID # 2022-011, 10 March 2022.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data generated in this study are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Funding Statement

This study was partly supported by the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R15CA216070 to A.S. Levenson. The content is solely the responsibility of the author and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

References

- 1.Siegel R.L., Miller K.D., Wagle N.S., Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2023. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2023;73:17–48. doi: 10.3322/caac.21763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Malik S.N., Brattain M., Ghosh P.M., Troyer D.A., Prihoda T., Bedolla R., Kreisberg J.I. Immunohistochemical demonstration of phospho-Akt in high Gleason grade prostate cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2002;8:1168–1171. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Paweletz C.P., Charboneau L., Bichsel V.E., Simone N.L., Chen T., Gillespie J.W., Emmert-Buck M.R., Roth M.J., Petricoin I.E., Liotta L.A. Reverse phase protein microarrays which capture disease progression show activation of pro-survival pathways at the cancer invasion front. Oncogene. 2001;20:1981–1989. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kim M.J., Cardiff R.D., Desai N., Banach-Petrosky W.A., Parsons R., Shen M.M., Abate-Shen C. Cooperativity of Nkx3.1 and Pten loss of function in a mouse model of prostate carcinogenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:2884–2889. doi: 10.1073/pnas.042688999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grant S. Cotargeting survival signaling pathways in cancer. J. Clin. Investig. 2008;118:3003–3006. doi: 10.1172/JCI36898E1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shorning B.Y., Dass M.S., Smalley M.J., Pearson H.B. The PI3K-AKT-mTOR Pathway and Prostate Cancer: At the Crossroads of AR, MAPK, and WNT Signaling. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020;21:4507. doi: 10.3390/ijms21124507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kinkade C.W., Castillo-Martin M., Puzio-Kuter A., Yan J., Foster T.H., Gao H., Sun Y., Ouyang X., Gerald W.L., Cordon-Cardo C., et al. Targeting AKT/mTOR and ERK MAPK signaling inhibits hormone-refractory prostate cancer in a preclinical mouse model. J. Clin. Investig. 2008;118:3051–3064. doi: 10.1172/JCI34764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dias S.J., Zhou X., Ivanovic M., Gailey M.P., Dhar S., Zhang L., He Z., Penman A.D., Vijayakumar S., Levenson A.S. Nuclear MTA1 overexpression is associated with aggressive prostate cancer, recurrence and metastasis in African Americans. Sci. Rep. 2013;3:2331–2341. doi: 10.1038/srep02331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hofer M.D., Kuefer R., Varambally S., Li H., Ma J., Shapiro G.I., Gschwend J.E., Hautmann R.E., Sanda M.G., Giehl K., et al. The role of metastasis-associated protein 1 in prostate cancer progression. Cancer Res. 2004;64:825–829. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-03-2755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dhar S., Kumar A., Zhang L., Rimando A.M., Lage J.M., Lewin J.R., Atfi A., Zhang X., Levenson A.S. Dietary pterostilbene is a novel MTA1-targeted chemopreventive and therapeutic agent in prostate cancer. Oncotarget. 2016;7:18469–18484. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.7841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dhar S., Kumar A., Li K., Tzivion G., Levenson A.S. Resveratrol regulates PTEN/Akt pathway through inhibition of MTA1/HDAC unit of the NuRD complex in prostate cancer. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2015;1853:265–275. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2014.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hemani R., Patel I., Inamdar N., Campanelli G., Donovan V., Kumar A., Levenson A.S. Dietary Pterostilbene for MTA1-Targeted Interception in High-Risk Premalignant Prostate Cancer. Cancer Prev. Res. 2022;15:87–100. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-21-0242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Parupathi P., Campanelli G., Deabel R.A., Puaar A., Devarakonda L.S., Kumar A., Levenson A.S. Gnetin C Intercepts MTA1-Associated Neoplastic Progression in Prostate Cancer. Cancers. 2022;14:6038. doi: 10.3390/cancers14246038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Choudhury A.D. PTEN-PI3K pathway alterations in advanced prostate cancer and clinical implications. Prostate. 2022;82((Suppl. S1)):S60–S72. doi: 10.1002/pros.24372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Braglia L., Zavatti M., Vinceti M., Martelli A.M., Marmiroli S. Deregulated PTEN/PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling in prostate cancer: Still a potential druggable target? Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Cell Res. 2020;1867:118731. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2020.118731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Asensi M., Ortega A., Mena S., Feddi F., Estrela J.M. Natural polyphenols in cancer therapy. Crit. Rev. Clin. Lab. Sci. 2011;48:197–216. doi: 10.3109/10408363.2011.631268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rudzinska A., Juchaniuk P., Oberda J., Wisniewska J., Wojdan W., Szklener K., Mandziuk S. Phytochemicals in Cancer Treatment and Cancer Prevention-Review on Epidemiological Data and Clinical Trials. Nutrients. 2023;15:1896. doi: 10.3390/nu15081896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Swetha M., Keerthana C.K., Rayginia T.P., Anto R.J. Cancer Chemoprevention: A Strategic Approach Using Phytochemicals. Front. Pharmacol. 2021;12:809308. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2021.809308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tewari D., Patni P., Bishayee A., Sah A.N., Bishayee A. Natural products targeting the PI3K-Akt-mTOR signaling pathway in cancer: A novel therapeutic strategy. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2022;80:1–17. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2019.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Narayanankutty A. Inhibitory Potential of Dietary Nutraceuticals on Cellular PI3K/Akt Signaling: Implications in Cancer Prevention and Therapy. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2021;21:1816–1831. doi: 10.2174/1568026621666210716152224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Narayanankutty A. Phytochemicals as PI3K/Akt/mTOR Inhibitors and Their Role in Breast Cancer Treatment. Recent Pat. Anticancer Drug Discov. 2020;15:188–199. doi: 10.2174/1574892815666200910164641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Levenson A.S. Metastasis-associated protein 1-mediated antitumor and anticancer activity of dietary stilbenes for prostate cancer chemoprevention and therapy. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2020;80:107–117. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2020.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gadkari K., Kolhatkar U., Hemani R., Campanelli G., Cai Q., Kumar A., Levenson A.S. Therapeutic Potential of Gnetin C in Prostate Cancer: A Pre-Clinical Study. Nutrients. 2020;12:3631. doi: 10.3390/nu12123631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kumar A., Dholakia K., Sikorska G., Martinez L.A., Levenson A.S. MTA1-Dependent Anticancer Activity of Gnetin C in Prostate Cancer. Nutrients. 2019;11:2096. doi: 10.3390/nu11092096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Love M.I., Huber W., Anders S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 2014;15:550. doi: 10.1186/s13059-014-0550-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liberzon A., Birger C., Thorvaldsdottir H., Ghandi M., Mesirov J.P., Tamayo P. The Molecular Signatures Database (MSigDB) hallmark gene set collection. Cell Syst. 2015;1:417–425. doi: 10.1016/j.cels.2015.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tani H., Hikami S., Iizuna S., Yoshimatsu M., Asama T., Ota H., Kimura Y., Tatefuji T., Hashimoto K., Higaki K. Pharmacokinetics and safety of resveratrol derivatives in humans after oral administration of melinjo (Gnetum gnemon L.) seed extract powder. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2014;62:1999–2007. doi: 10.1021/jf4048435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Espinoza J.L., Elbadry M.I., Taniwaki M., Harada K., Trung L.Q., Nakagawa N., Takami A., Ishiyama K., Yamauchi T., Takenaka K., et al. The simultaneous inhibition of the mTOR and MAPK pathways with Gnetin-C induces apoptosis in acute myeloid leukemia. Cancer Lett. 2017;400:127–136. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2017.04.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nair A.B., Jacob S. A simple practice guide for dose conversion between animals and human. J. Basic Clin. Pharm. 2016;7:27–31. doi: 10.4103/0976-0105.177703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nakagami Y., Suzuki S., Espinoza J.L., Vu Quang L., Enomoto M., Takasugi S., Nakamura A., Nakayama T., Tani H., Hanamura I., et al. Immunomodulatory and Metabolic Changes after Gnetin-C Supplementation in Humans. Nutrients. 2019;11:1403. doi: 10.3390/nu11061403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Konno H., Kanai Y., Katagiri M., Watanabe T., Mori A., Ikuta T., Tani H., Fukushima S., Tatefuji T., Shirasawa T. Melinjo (Gnetum gnemon L.) Seed Extract Decreases Serum Uric Acid Levels in Nonobese Japanese Males: A Randomized Controlled Study. Evid. Based Complement Altern. Med. 2013;2013:589169. doi: 10.1155/2013/589169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Espinoza J.L., An D.T., Trung L.Q., Yamada K., Nakao S., Takami A. Stilbene derivatives from melinjo extract have antioxidant and immune modulatory effects in healthy individuals. Integr. Mol. Med. 2015;2:405–413. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bitting R.L., Armstrong A.J. Targeting the PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway in castration-resistant prostate cancer. Endocr. Relat. Cancer. 2013;20:R83–R99. doi: 10.1530/ERC-12-0394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sharrard R.M., Maitland N.J. Regulation of protein kinase B activity by PTEN and SHIP2 in human prostate-derived cell lines. Cell. Signal. 2007;19:129–138. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2006.05.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hay N., Sonenberg N. Upstream and downstream of mTOR. Genes Dev. 2004;18:1926–1945. doi: 10.1101/gad.1212704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cai Z., Wang J., Li Y., Shi Q., Jin L., Li S., Zhu M., Wang Q., Wong L.L., Yang W., et al. Overexpressed Cyclin D1 and CDK4 proteins are responsible for the resistance to CDK4/6 inhibitor in breast cancer that can be reversed by PI3K/mTOR inhibitors. Sci. China Life Sci. 2023;66:94–109. doi: 10.1007/s11427-021-2140-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Xu Y., Chen S.Y., Ross K.N., Balk S.P. Androgens induce prostate cancer cell proliferation through mammalian target of rapamycin activation and post-transcriptional increases in cyclin D proteins. Cancer Res. 2006;66:7783–7792. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-4472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Recchia A.G., Musti A.M., Lanzino M., Panno M.L., Turano E., Zumpano R., Belfiore A., Ando S., Maggiolini M. A cross-talk between the androgen receptor and the epidermal growth factor receptor leads to p38MAPK-dependent activation of mTOR and cyclinD1 expression in prostate and lung cancer cells. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2009;41:603–614. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2008.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gao N., Flynn D.C., Zhang Z., Zhong X.S., Walker V., Liu K.J., Shi X., Jiang B.H. G1 cell cycle progression and the expression of G1 cyclins are regulated by PI3K/AKT/mTOR/p70S6K1 signaling in human ovarian cancer cells. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2004;287:C281–C291. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00422.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stelloo S., Sanders J., Nevedomskaya E., de Jong J., Peters D., van Leenders G.J., Jenster G., Bergman A.M., Zwart W. mTOR pathway activation is a favorable prognostic factor in human prostate adenocarcinoma. Oncotarget. 2016;7:32916–32924. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.8767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Barata P.C., Magi-Galluzzi C., Gupta R., Dreicer R., Klein E.A., Garcia J.A. Association of mTOR Pathway Markers and Clinical Outcomes in Patients with Intermediate-/High-risk Prostate Cancer: Long-Term Analysis. Clin. Genitourin. Cancer. 2019;17:366–372. doi: 10.1016/j.clgc.2019.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jerusalem G., Rorive A., Collignon J. Use of mTOR inhibitors in the treatment of breast cancer: An evaluation of factors that influence patient outcomes. Breast Cancer. 2014;6:43–57. doi: 10.2147/BCTT.S38679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Battelli C., Cho D.C. mTOR inhibitors in renal cell carcinoma. Therapy. 2011;8:359–367. doi: 10.2217/thy.11.32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hua H., Kong Q., Zhang H., Wang J., Luo T., Jiang Y. Targeting mTOR for cancer therapy. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2019;12:71. doi: 10.1186/s13045-019-0754-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Edlind M.P., Hsieh A.C. PI3K-AKT-mTOR signaling in prostate cancer progression and androgen deprivation therapy resistance. Asian J. Androl. 2014;16:378–386. doi: 10.4103/1008-682X.122876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Armstrong A.J., Netto G.J., Rudek M.A., Halabi S., Wood D.P., Creel P.A., Mundy K., Davis S.L., Wang T., Albadine R., et al. A pharmacodynamic study of rapamycin in men with intermediate- to high-risk localized prostate cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2010;16:3057–3066. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-0124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Xu X., Kong X., Liu T., Zhou L., Wu J., Fu J., Wang Y., Zhu M., Yao S., Ding Y., et al. Metastasis-associated protein 1, modulated by miR-30c, promotes endometrial cancer progression through AKT/mTOR/4E-BP1 pathway. Gynecol. Oncol. 2019;154:207–217. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2019.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Campanelli G., Deabel R.A., Puaar A., Devarakonda L.S., Parupathi P., Zhang J., Waxner N., Yang C., Kumar A., Levenson A.S. Molecular Efficacy of Gnetin C as Dual-Targeted Therapy for Castrate-Resistant Prostate Cancer. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2023;67:e2300479. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.202300479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data generated in this study are available upon request from the corresponding author.