Abstract

Background

Recent data indicate that non-Plasmodium falciparum species may be more prevalent than thought in sub-Saharan Africa. Although Plasmodium malariae, Plasmodium ovale spp., and Plasmodium vivax are less severe than P. falciparum, treatment and control are more challenging, and their geographic distributions are not well characterized.

Methods

We randomly selected 3284 of 12 845 samples collected from cross-sectional surveys in 100 health facilities across 10 regions of Mainland Tanzania and performed quantitative real-time PCR to determine presence and parasitemia of each malaria species.

Results

P. falciparum was most prevalent, but P. malariae and P. ovale were found in all but 1 region, with high levels (>5%) of P. ovale in 7 regions. The highest P. malariae positivity rate was 4.5% in Mara and 8 regions had positivity rates ≥1%. We only detected 3 P. vivax infections, all in Kilimanjaro. While most nonfalciparum malaria-positive samples were coinfected with P. falciparum, 23.6% (n = 13 of 55) of P. malariae and 14.7% (n = 24 of 163) of P. ovale spp. were monoinfections.

Conclusions

P. falciparum remains by far the largest threat, but our data indicate that malaria elimination efforts in Tanzania will require increased surveillance and improved understanding of the biology of nonfalciparum species.

Keywords: malaria, Tanzania, Plasmodium falciparum, Plasmodium malariae, Plasmodium ovale, Plasmodium vivax, nonfalciparum species

A molecular analysis of 3284 dried blood spots collected from cross-sectional surveys in 100 health facilities across 10 regions of Mainland Tanzania found that P. ovale spp. and P. malariae are present nationwide and must be considered in surveillance activities.

Sub-Saharan Africa accounted for 95% of malaria cases and 96% of malaria deaths in 2021 [1]. Although Plasmodium falciparum is the most prevalent and deadliest human malaria species in sub-Saharan Africa, 4 other species are present (Plasmodium vivax, Plasmodium malariae, Plasmodium ovale curtisi, and Plasmodium ovale wallikeri). Furthermore, recent research suggests that these 4 species are more prevalent than previously thought and their prevalence may increase in the context of intensive P. falciparum control/elimination [2–8]. This possibility is particularly salient in light of current malaria elimination goals stemming from the World Health Organization (WHO) Global Technical Strategy [9], which aims by 2030 to reduce the global malaria burden by 90% from 2015 levels. Nonfalciparum malaria species have notably different biology than P. falciparum and are not necessarily controlled by the same measures, due to the potential for transmission by different vectors, differing seasonality [10], potentially earlier gametocytogenesis [11–13], presence of hypnozoite stages/persistent infection [12, 14], generally lower levels of parasite carriage/density [15, 16], and greater asymptomatic infection and transmission [10].

P. vivax is the most widely distributed human malaria species globally, occurring in Asia, Africa, Latin America, and Oceania [17]. It survives in more temperate climates than P. falciparum by developing in mosquitoes at lower temperatures and lying dormant as hypnozoites for seasonal reappearance when vectors are available [17]. The strength of Duffy selection with rapid sweep across sub-Saharan Africa is testament to the morbidity and mortality that P. vivax has caused in the past [18]. Although generally less severe than P. falciparum [19], the presence of the relapsing hypnozoite stage in the liver can make treatment and control more difficult [20]. Outside of Africa, for example, in the Western Pacific, P. vivax has increased as P. falciparum control has succeeded [1]. The prevailing dogma for decades was that P. vivax was largely absent from Africa due to high prevalence of the Duffy-negative trait, which is widespread in most sub-Saharan Africa populations [21]. However, recent evidence across Africa indicates increased P. vivax detection in Duffy-negative patients [22–24]. Nonetheless, it is still much less prevalent than P. falciparum and the clinical significance and management strategies of such infections are still unknown.

P. malariae and P. ovale spp. are much less studied than either P. falciparum or P. vivax. They have both been detected throughout Africa, but usually at much lower prevalence than P. falciparum [25]. Both are frequently detected in coinfections with P. falciparum rather than as monoinfections [15, 25–28], although exceptions have been noted [29]. P. ovale spp. infections are generally found at low density, while P. malariae infections can cause higher parasitemia [15]. P. ovale spp. have relapsing stages like P. vivax, which likely means that their control and elimination will be more difficult, as is true of P. vivax [12]. P. malariae is thought to be more prevalent than P. ovale, particularly in West Africa [5, 6, 14, 15]. It does not have a liver stage, but can cause chronic infection [14].

While there are data to suggest that nonfalciparum malaria is widespread in sub-Saharan Africa [4, 26, 28, 29], and that these prevalences may be increasing [3, 5, 30], rapid diagnostic tests (RDTs) currently deployed in Africa are better at detecting falciparum malaria than other species [31, 32]. Given the preponderance of both low-density infections and multiple species coinfections with nonfalciparum malaria species, as well as the lower likelihood of severe disease, these species are less likely to be detected during surveillance activities or at the point of care. While molecular diagnostics such as quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) are readily capable of detecting all Plasmodium spp., these tools are highly technical and resource-prohibitive (approximately 14–28 times more expensive per sample than RDTs) [33], so are rarely used outside of laboratory research activities.

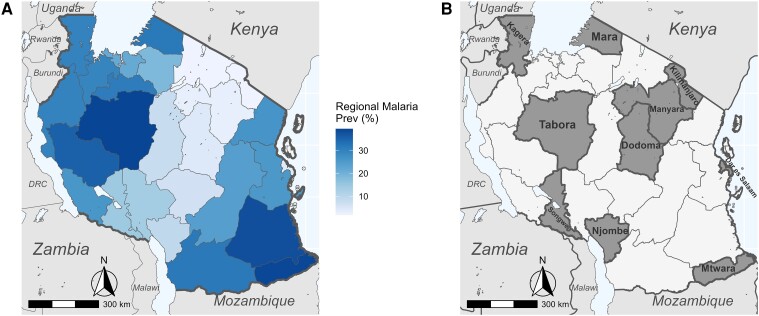

Tanzania had the third highest malaria mortality in the world in 2021, accounting for 4.1% of global malaria deaths [1]. Malaria transmission in Tanzania is predominantly P. falciparum and highly heterogeneous by region and season (Figure 1A) [34]. Transmission is high and endemic along the coast and the Lake Zone, and low, unstable, and seasonal in large urban areas and highland regions, while the rest of the country is subject to moderate seasonal transmission [34]. Malaria control in Tanzania relies on long-lasting insectidial nets and indoor residual spraying for vector control, RDTs for diagnosis, and artemether-lumefantrine for first-line treatment [1]. Intermittent preventive treatment of pregnant women with sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine is the only chemoprevention currently implemented in Tanzania, despite WHO recommending multiple methods [35].

Figure 1.

A, National map of regional malaria prevalence in 2021 as determined by a combination of blood slide positivity rates and Pfhrp2/LDH RDT positivity rates. Data courtesy of National Malaria Control Programme, Dodoma. B, Map of Tanzania highlighting study regions.

Previous work assessed the prevalence of nonfalciparum malaria among asymptomatic schoolchildren, finding a surprisingly high rate (24%) of P. ovale spp. infection [8]. However, data from symptomatic cases for Tanzania are based primarily on sporadic convenience samples and do not provide broad geographic information about the distribution of nonfalciparum malaria. To address the distribution of nonfalciparum malaria in symptomatic individuals from all age groups, we conducted a survey of symptomatic malaria cases across 10 different regions of Mainland Tanzania with varying transmission intensity. We present a molecular analysis of malaria species positivity rates within this national dataset.

METHODS

Ethics

The Molecular Surveillance of Malaria in Tanzania (MSMT) study protocol was approved by the Tanzanian Medical Research Coordinating Committee of the National Institute for Medical Research and involved approved standard procedures for informed consent and sample deidentification. Additional details are described elsewhere [36]. Deidentified samples were considered nonhuman subjects’ research at the University of North Carolina and Brown University. In addition, publicly available aggregate data on malaria prevalence from all regions of Tanzania was provided by the National Malaria Control Programme (NMCP) for 2021 to map regional malaria prevalence.

Sample Collection

A random subset of 3284 samples were drawn from 12 845 symptomatic samples, which included RDT-positive and -negative samples collected during the MSMT project [36] in 2021. Briefly, samples were collected in the MSMT Plasmodium falciparum histidine-rich protein 2 and 3 (Pfhrp2/3) gene deletion survey in 10 regions: Dar es Salaam, Dodoma, Kagera, Kilimanjaro, Manyara, Mara, Mtwara, Njombe, Songwe, and Tabora [36], with additional samples collected for population genetic studies of malaria parasites. Additional details on study site selection are given in Rogier et al [36]. Surveys were conducted according to the WHO protocol [37] and included 10 regions (Figure 1B), which are distributed across Mainland Tanzania with variable malaria transmission levels. Regions were assigned to 4 transmission strata ranging from very low to high based on NMCP data from 2019 [34] (Table 1).

Table 1.

Summary of Study Regions and Number of Samples Analyzed

| Region | Transmission Strata | Samples | Median Age, y (IQR) | Gender Distribution, No. (%)a | RDT Positive, No. (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female | Male | |||||

| Kilimanjaro | Very low | 897 | 24 (8–41) | 515 (57.6) | 379 (42.4) | 161 (17.9) |

| Manyara | Very low | 223 | 19 (7.5–29) | 109 (49.3) | 112 (50.7) | 146 (65.5) |

| Njombe | Very low | 211 | 16 (6–31) | 104 (49.8) | 105 (50.2) | 128 (60.7) |

| Subtotal | Very low | 1331 | 21 (7–36) | 728 (55.0) | 596 (45.0) | 435 (32.7) |

| Dar es Salaam | Low | 213 | 21 (5–31) | 95 (47.3) | 106 (52.7) | 152 (71.4) |

| Dodoma | Low | 274 | 13 (3–28) | 112 (53.3) | 98 (46.7) | 130 (47.4) |

| Songwe | Low | 145 | 7 (3–26) | 90 (62.1) | 55 (37.9) | 96 (66.2) |

| Subtotal | Low | 632 | 14 (3–28) | 297 (53.4) | 259 (46.6 | 378 (59.8) |

| Mara | Moderate | 335 | 10 (4–16.5) | 190 (57.1) | 143 (42.9) | 235 (70.1) |

| Tabora | Moderate | 267 | 4 (2–13) | 140 (52.8) | 125 (47.2) | 212 (79.4) |

| Subtotal | Moderate | 602 | 6.5 (2–14.75) | 330 (55.2) | 268 (44.8) | 447 (74.3) |

| Kagera | High | 417 | 5 (2–16) | 218 (52.4) | 198 (47.6) | 260 (62.4) |

| Mtwara | High | 302 | 4 (2–15.75) | 181 (59.9) | 121 (40.1) | 243 (80.5) |

| Subtotal | High | 719 | 4 (2–16) | 399 (55.6) | 319 (44.4) | 503 (70.0) |

| Overall | All | 3284 | 12 (3–28) | 1754 (54.9) | 1442 (45.1) | 1763 (53.7) |

aGender identification is not available for all participants.

Dried blood spots (DBS) were collected from patients with malaria-like symptoms. Most individuals (n = 3234) were tested with a standard PfHRP2/pan-Plasmodium lactate dehydrogenase (pLDH) RDT. As some individuals (n = 1942) participated in a specific evaluation of Pfhrp2/3 gene deletions, they were also administered an experimental PfLDH-based RDT [36], per WHO protocol [37]. Samples were considered malaria-positive if any RDT was positive.

Molecular Speciation Assays

DNA from three 6-mm DBS punches [38], representing approximately 25 μL of blood [8] was extracted using Chelex into a final usable volume of approximately 100 μL. Quantitative real-time PCR assays targeting the 18S ribosomal subunit were performed according to published protocols (Supplementary Table 1) [28]. A separate qPCR assay was run for each species: P. falciparum, P. malariae, P. ovale spp. (detecting both P. ovale curtisi and P. ovale wallikeri), and P. vivax. Detection and parasitemia quantification were based on standard curves generated using dilutions of plasmids from MR4 (MRA-177, MRA-178, MRA-179, MRA-180; BEI Resources). Plasmids were quantified using a Qubit fluorometer, then normalized to a standard concentration of 0.01 ng/µL before serial dilutions. Three 10-fold dilution concentrations (0.001 ng/µL, 0.0001 ng/µL, and 0.00001 ng/µL) were used for qPCR standard curves. Semiquantitative parasitemia was estimated based on the assumption of six 18S rRNA gene copies per parasite genome [28], then multiplied by 4 to account for the dilution of eluted DNA relative to initial blood volume [8]. P. malariae assays used 42 cycles, while all other assays used 45 cycles to detect low-density infections [28]. This approach has been previously validated as highly sensitive and specific [28, 39].

Statistical Analysis

Positivity rates were calculated for each region, as the data are biased toward individuals with both clinical symptoms and RDT positivity and therefore do not represent true prevalence inclusive of asymptomatic infections. Regional-level maps of positivity rate for each species were created using the R package sf (version 1.0–9) based on shape files available from GADM.org and naturalearthdata.com accessed via the R package rnaturalearth (version 0.3.2) [40].

Variation in species-specific positivity rates by region, transmission strata, individuals’ age, and age group (young children <5 years, school-aged children 5–16 years [8, 41], and adults >16 years) was assessed for significance with generalized linear models or ANOVA, as appropriate, in R. Given there is no consensus for an age range for school aged children, a major asymptomatic infectious reservoir [42–44], we used the age range of the 2017 Tanzania National Schoolchildren Survey (5–16 years) [8, 41].

RESULTS

Study Population

Within this subset of 3284 patients, the median age was 12 (interquartile range [IQR], 3–28) years with a range of 6 months to 87 years. Children (≤16 years old) constituted 56.4% of participants (n = 1853), while adults (>16 years old) constituted the remaining 43.6% (n = 1431). Young children (<5 years old) comprised 58.3% (n = 1081) of the child participants, while the remaining 41.7% (n = 772) were school aged (5–16 years old). Gender identifications were available for 3196 participants and female skewed, with 1754 female (54.9%) and 1442 male participants (45.1%). Sample sizes for each region are given in Table 1. Of sampled individuals, 53.7% (n = 1763) tested positive by any RDT.

qPCR Positivity by Species

Across all 3284 individuals tested for all species, P. falciparum was detected in 56.8% (n = 1865; 95% confidence interval [CI], 55.1%–58.5%), P. malariae in 1.7% (n = 55; 95% CI, 1.3%–2.2%), P. ovale spp. in 5.0% (n = 163; 95% CI, 4.3%–5.8%), and P. vivax in 0.09% (n = 3; 95% CI, .02%–.2%).

Mixed-species infections were common (Table 2 and Supplementary Table 2). The majority of P. malariae infections were mixed with P. falciparum (56.4%, n = 31 of 55), although P. malariae monoinfections were also common (23.6%, n = 13 of 55), as were 3-species infections with P. malariae, P. falciparum, and P. ovale spp. (18.2%, n = 10 of 55). The vast majority of P. ovale spp. infections were also mixed with P. falciparum (78.5%, n = 128 of 163; Table 2 and Supplementary Table 2). As with P. malariae, single-species infections occurred and were more common than either 3-species infections or mixed infection with P. ovale and P. malariae only. Of the 3 P. vivax infections detected, all were mixed with P. falciparum (Table 2 and Supplementary Table 2). This small sample size precluded further statistical analyses.

Table 2.

Infection Composition Proportions for Nonfalciparum Infections

| Infection Type | Count | Proportion, % |

|---|---|---|

| P. malariae | 13 | 23.6 |

| P. malariae/P. falciparum | 31 | 56.4 |

| P. malariae/P. ovale | 1 | 1.8 |

| P. malariae/P. falciparum/P. ovale | 10 | 18.2 |

| All P. malariae infections | 55 | … |

| P. ovale | 24 | 14.7 |

| P. ovale/P. falciparum | 128 | 78.5 |

| P. malariae/P. ovale | 1 | 0.6 |

| P. malariae/P. falciparum/P. ovale | 10 | 6.1 |

| All P. ovale infections | 163 | … |

| P. vivax | 0 | 0 |

| P. vivax/P. falciparum | 3 | 100 |

| All P. vivax infections | 3 | … |

Sum of proportions may not equal 100% due to rounding.

Parasite Density

Parasitemia as determined by semiquantitative qPCR based on standard dilutions of plasmid varied significantly (ANOVA P < .001) by species, with P. falciparum parasitemia the highest at median 1 226 000 parasites/µL (IQR, 23 280–13 090 000 p/µL), followed by P. malariae at 389 920 p/µL (IQR, 19 364–2 147 000 p/µL), and P. ovale spp. having the lowest median parasitemia at 3970 p/µL (IQR, 396–54 000 p/µL). A Tukey post hoc test detected a significant difference in parasitemia (P < .001) between P. falciparum and P. ovale spp., but not between the other species pairs. Parasitemia did not differ significantly between single and mixed-species infections (Supplementary Figure 1). The 3 P. vivax infections (parasitemia of 70, 4704, and 61 400 p/µL) were not analyzed.

Variability by Region and Transmission Strata

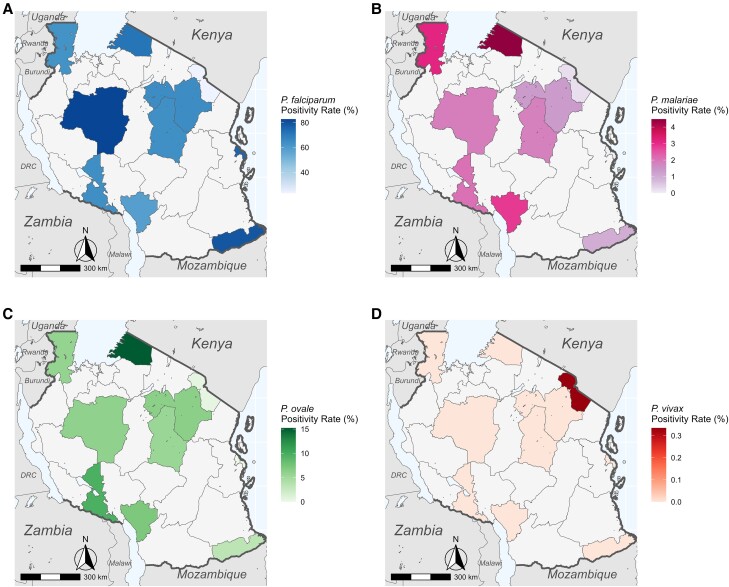

P. falciparum was detected in every region sampled (Figure 2A) with variable positivity rates (Table 3). P. malariae and P. ovale spp. were detected in every region except for Dar es Salaam (Figure 2B and 2C). P. vivax was only detected in Kilimanjaro (Figure 2D).

Figure 2.

Species positivity rate maps across Tanzania for (A) Plasmodium falciparum, (B) Plasmodium malariae, (C) Plasmodium ovale spp., and (D) Plasmodium vivax. Shaded regions represent only positivity rates among health facility samples and should not be assumed to represent true regional prevalences.

Table 3.

Species Positivity Rates by Region

| Region | P. falciparum Positive Samples | P. malariae Positive Samples | P. ovale Positive Samples | P. vivax Positive Samples | Total Samples |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dar es Salaam | 161 (75.6) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 213 |

| Dodoma | 174 (63.5) | 5 (1.8) | 15 (5.5) | 0 (0) | 274 |

| Kagera | 261 (62.6) | 13 (3.1) | 24 (5.8) | 0 (0) | 417 |

| Kilimanjaro | 209 (23.3) | 2 (0.2) | 4 (0.4) | 3 (0.3) | 897 |

| Manyara | 144 (64.6) | 3 (1.4) | 14 (6.3) | 0 (0) | 227 |

| Mara | 240 (71.6) | 15 (4.5) | 51 (15.2) | 0 (0) | 335 |

| Mtwara | 238 (78.8) | 3 (1.0) | 10 (3.3) | 0 (0) | 302 |

| Njombe | 124 (58.8) | 6 (2.8) | 15 (7.1) | 0 (0) | 211 |

| Songwe | 93 (64.1) | 3 (2.1) | 14 (9.7) | 0 (0) | 145 |

| Tabora | 221 (82.8) | 5 (1.9) | 16 (6.0) | 0 (0) | 267 |

Data are No. (%).

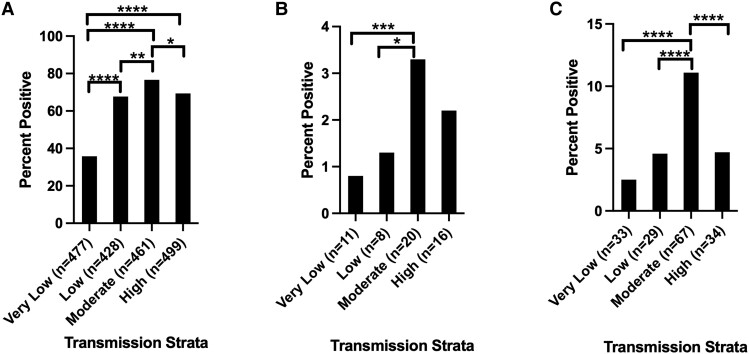

P. falciparum was most abundant in Tabora (moderate, 82.8%, n = 221 of 267; Table 3) and Mtwara (high, 78.8%, n = 238 of 302), while it was least abundant in Kilimanjaro (very low, 23.3%, n = 209 of 897). P. malariae was most abundant in Mara (moderate, 4.5%, n = 15 of 335) and Kagera (high, 3.1%, n = 13 of 417) and least abundant in Kilimanjaro (very low, 0.2%, n = 2 of 897) and Mtwara (high, 1.0%, n = 3 of 302). P. ovale spp. positivity rates surpassed 5% in 7 regions, with the highest abundance in Mara (moderate, 15.2%, n = 51 of 335), Songwe (low, 9.7%, n = 14 of 145), and Njombe (very low, 7.1%, n = 15 of 211). It was rare in Kilimanjaro (very low, 0.4%, n = 4 of 897). In all 10 regions, P. ovale positivity rates were higher than P. malariae. Positivity rates varied significantly by region for all 3 species (ANOVA P < .001). Overall, transmission strata had a highly significant (ANOVA P < .001) effect on the positivity rates of all 3 species. Tukey post hoc analysis between strata is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Tukey analysis of malaria species positivity rate by transmission strata. A total of 1331, 632, 602, and 719 samples were available in the very low, low, medium, and high transmission strata, respectively. The number of positive samples per strata for each species is shown on the x-axis. A, Plasmodium falciparum parasite rates by strata. B, Plasmodium malariae parasite rate by strata. C, Plasmodium ovale spp. parasite rate by strata. Pairwise comparisons of strata with significant differences in parasite rate are shown.* P < .05, ** P < .01, *** P < .001, **** P < .0001.

Transmission strata had a significant effect on the likelihood of P. falciparum coinfection by ANOVA (P = .002) for P. ovale spp. A Tukey post hoc test indicated 24.6% (95% CI, 2.5%–46.7%) fewer coinfections in very low versus high transmission strata (P = .02) as well as 28.9% (95% CI, .97%–48.1%) fewer coinfections in very low versus moderate strata (P < .001). There was also a nearly significant (P = .06) reduction in coinfections between the very low and low transmission strata. By contrast, there was no significant effect on the likelihood of P. malariae coinfection with P. falciparum.

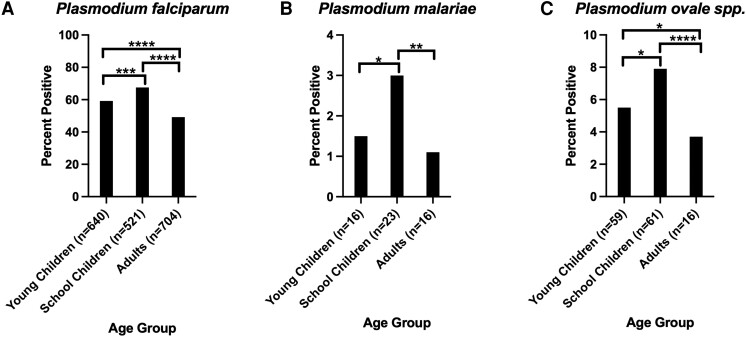

Variability by Age Group

No significant difference in P. malariae prevalence by age in years was detected (generalized linear model [GLM], P = .24). In contrast to P. malariae, age significantly correlated with P. ovale spp. infection (GLM, P = .001). Children had significantly more P. ovale spp. infections (6.5%, n = 120 of 1853) than adults (3.0%, n = 43 of 1431). When splitting participants into 3 age groups (Figure 4), overall significant correlations by ANOVA were observed with qPCR positivity for P. falciparum (P < .001), P. malariae (P = .004), and P. ovale spp. (P < .001) (Figure 4). For P. falciparum, a Tukey post hoc test indicated significant variation (P < .001) between young children (<5 years), schoolchildren (5–16 years), and adults (>16 years), with children more likely to be positive than adults and schoolchildren more likely to be positive than young children. Schoolchildren were also more likely to be positive for P. malariae than either adults (P = .003) or young children (P = .03), but no significant differences were detected between young children and adults. For P. ovale spp., schoolchildren were again more likely to test positive than either adults (P < .001) or young children (P = .04), and young children were more likely to test positive than adults (P = .01).

Figure 4.

Tukey analysis of malaria species positivity rate by age strata. A total of 1081, 772, and 1413 individuals were in the young children (<5 years), schoolchildren (5–16 years), and adult (>16 years) strata, respectively. The number of positive samples per age strata for each species is shown on the x-axis. A, Plasmodium falciparum parasite rate by age strata. B, Plasmodium malariae parasite rate by age strata. C, Plasmodium ovale spp. parasite rate by age strata. Pairwise comparisons of strata with significant differences in parasite rate are shown. All other pairwise comparisons were nonsignificant. * P < .05, ** P < .01, *** P < .001, **** P < .0001.

DISCUSSION

This study presents a comprehensive picture of the geographic distribution of different malaria species among symptomatic patients within Mainland Tanzania across all ages and in different transmission strata. It establishes a snapshot of the epidemiological landscape in 2021 that will enable effective longitudinal tracking of nonfalciparum malaria. P. falciparum remains by far the most prevalent malaria species in Tanzania. Nonetheless, P. malariae and especially P. ovale spp. are much more abundant than previously acknowledged, with multiple regions approaching or surpassing (in the case of P. ovale spp.) 5% positivity rates. P. vivax is rarely detected and was found only in Kilimanjaro.

Our findings support a recent report of high rates of P. ovale infection among asymptomatic schoolchildren in 2017 [8]. Direct comparison between the studies is not possible due to the significant methodological differences (eg, clinic-based symptomatic vs school-based asymptomatic). However, we see predominately low-density P. ovale infections that are overrepresented in the school-aged individuals in this study. Although the 2017 study identified P. ovale spp. primarily as monoinfections [8], we identified mostly mixed infections with P. falciparum (Table 2). This discrepancy is most likely explained by our inclusion of symptomatic patients in the study, as infection with P. falciparum likely led them to seek medical care, while schoolchildren with P. ovale spp. monoinfections are more likely to be asymptomatic [15]. Indeed, they constitute a major asymptomatic infectious reservoir [42–44].

The relatively high (>5%) P. ovale spp. positivity rates in 7 regions point to the necessity of active surveillance for these species, particularly given data from Tanzania and elsewhere showing increased incidence [3, 5, 7, 30]. As was seen by the 2017 study [8], we found P. ovale spp. monoinfections to be more frequent in areas of low P. falciparum transmission, even though our samples came from symptomatic patients reporting to health facilities. The presence of these infections suggests that measures developed for P. falciparum will not completely control malaria in these regions. Because P. ovale spp. develops hypnozoites, which can cause relapse and which are not treated by standard schizonticidal regimens [12], its control is more complicated than that of P. falciparum. While major aspects of its biology, including major vectors, are poorly understood, transmission may be seasonal and asynchronous with P. falciparum [10]. Proactive monitoring will allow the NMCP and other decision makers to regularly monitor incidence and implement P. ovale-specific control measures as appropriate to support malaria control and elimination efforts.

While P. malariae was less abundant than P. ovale spp. in our study, it is nonetheless present throughout Tanzania and also warrants regular surveillance. We identified few significant differences in P. malariae positivity by transmission strata and no effect of transmission strata on likelihood of coinfection with P. falciparum, but these results may stem from small sample sizes (55 total P. malariae infections and 13 monoinfections). The relatively low P. malariae levels detected in our study are also consistent with those found in other surveys of Tanzania as well as Malawi and Western Kenya [8, 28, 45]. Taken together, these results suggest that P. malariae is less of a concern than P. ovale spp. in East Africa, consistent with more frequent reports of P. malariae in West and Central Africa [6, 15]. This geographical difference could stem from less abundant and/or competent vectors in East Africa, but this aspect of P. malariae biology is unknown. However, transmission of P. malariae, like P. ovale spp., has been noted to increase as P. falciparum transmission reduces throughout East Africa [2, 3, 5, 16]. If these trends continue and both species become more abundant, effective malaria control will increasingly hinge upon their surveillance.

While there was significant regional variation in P. malariae and P. ovale spp. abundance in our study, it did not consistently correspond with transmission strata defined by P. falciparum data. In both P. malariae and P. ovale spp., the moderate transmission strata had the highest positivity rate, largely stemming from the high rates of both in Mara region. This finding may be due to these strata being based on 2019 data—malaria transmission in many regions may have changed due to interventions by 2021. While P. malariae was equally likely to be coinfected with P. falciparum in all transmission strata, P. ovale spp. was more likely to occur as a single-species monoinfection in the very low transmission strata, which could reflect low P. falciparum abundance and/or stem from relapse infections.

Based on our data, P. vivax remains a minimal concern in Tanzania. However, like the other species, its incidence could increase as P. falciparum's decreases and like P. ovale spp., it would require specific treatment and control measures. Other studies have also detected P. vivax at low levels in Kagera, Mara, and Mwanza [8, 46], the coastal regions of Mtwara and Tanga [8], and the Zanzibar archipelago [16, 47]. The fact that we did not detect P. vivax in multiple regions is consistent with its characteristically low prevalence of ≤1%. Because of its low prevalence, more intensive and targeted surveillance will be necessary to understand the biology of P. vivax in Tanzania, but its relative clinical impact is likely minor.

Case-based surveillance pilots targeting malaria elimination have been implemented within the very low transmission regions of Kilimanjaro and Manyara, with the goal of expanding to other very low transmission regions [48]. While our results suggest that nonfalciparum species are present at low prevalence within Kilimanjaro, and therefore unlikely to present major barriers to elimination there, Manyara has P. ovale spp. positivity rates > 5%, meaning that elimination efforts there will need to account for the specific surveillance, treatment, and control challenges presented by this species. Standardized treatment protocols currently employed in Tanzania do not incorporate “radical cure” with primaquine or tafenoquine to treat the liver-stage hypnozoites that cause relapses in P. ovale spp. [49]. As such, while artemisinin combination therapy treatment may clear blood-stage parasites, relapses will continue to occur.

This study has several limitations. Given the sampling scheme, we are unable to determine true prevalence rates for each species and report parasite rate. This limitation is due to the fact that RDT-positive individuals were likely overenrolled, meaning that RDT-negative individuals are underrepresented for an unbiased prevalence estimate, and the asymptomatic reservoir was not sampled. An additional limitation is that some malaria-like symptoms may reflect other infections, even in patients who were positive for nonfalciparum malaria infections. Parasitemia estimates are also relative given the use of plasmids as the control and a multicopy gene for detection. Better controls are needed for accurate quantification of nonfalciparum malaria using molecular methods. Lastly, while encompassing large regions of the country, the survey was not designed to be fully nationally representative and misses one crucial preelimination area, Zanzibar, where data on nonfalciparum malaria may be very beneficial for elimination plans.

Nonfalciparum malaria, particularly P. ovale spp. and P. malariae, is present throughout Mainland Tanzania. To achieve effective control and elimination of malaria, it will be necessary to conduct further surveillance and research on these species. Ongoing research as part of MSMT will enable both longitudinal epidemiological study and genomic characterization of the nonfalciparum malaria landscape in Tanzania, as nationwide samples from 2022 and 2023 will be available, allowing a fuller picture of the abundance of P. malariae, P. ovale spp., and P. vivax within Tanzania, as well as an indication of temporal trends that are not detectable in the work presented here. In addition, efforts to sequence high parasitemia P. malariae and P. ovale spp. samples collected in 2021 are ongoing and will grant us a deeper and more comprehensive picture of the Tanzanian populations of these species.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at The Journal of Infectious Diseases online (http://jid.oxfordjournals.org/). Supplementary materials consist of data provided by the author that are published to benefit the reader. The posted materials are not copyedited. The contents of all supplementary data are the sole responsibility of the authors. Questions or messages regarding errors should be addressed to the author.

Supplementary Material

Contributor Information

Zachary R Popkin-Hall, Institute for Global Health and Infectious Diseases, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, North Carolina, USA.

Misago D Seth, National Institute for Medical Research, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania.

Rashid A Madebe, National Institute for Medical Research, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania.

Rule Budodo, National Institute for Medical Research, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania.

Catherine Bakari, National Institute for Medical Research, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania.

Filbert Francis, National Institute for Medical Research, Tanga Center, Tanga, Tanzania.

Dativa Pereus, National Institute for Medical Research, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania.

David J Giesbrecht, Department of Entomology, The Connecticut Agricultural Experiment Station, New Haven, Connecticut, USA.

Celine I Mandara, National Institute for Medical Research, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania.

Daniel Mbwambo, National Malaria Control Programme, Dodoma, Tanzania.

Sijenunu Aaron, National Malaria Control Programme, Dodoma, Tanzania.

Abdallah Lusasi, National Malaria Control Programme, Dodoma, Tanzania.

Samwel Lazaro, National Malaria Control Programme, Dodoma, Tanzania.

Jeffrey A Bailey, Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, Warren Alpert Medical School, Brown University, Providence, Rhode Island, USA; Center for Computational Molecular Biology, Brown University, Providence, Rhode Island, USA.

Jonathan J Juliano, Institute for Global Health and Infectious Diseases, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, North Carolina, USA.

Deus S Ishengoma, National Institute for Medical Research, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania; Department of Immunology and Infectious Diseases, Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston, Massachusetts, USA; Faculty of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Monash University, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia.

Notes

Acknowledgments. The authors thank participants and parents/guardians of all children who took part in the surveillance. We acknowledge the contribution of the following project staff and other colleagues who participated in data collection and/or laboratory processing of samples: Raymond Kitengeso, Ezekiel Malecela, Muhidin Kassim, Athanas Mhina, August Nyaki, Juma Tupa, Anangisye Malabeja, Emmanuel Kessy, George Gesase, Tumaini Kamna, Grace Kanyankole, Oswald Osca, Richard Makono, Ildephonce Mathias, Godbless Msaki, Rashid Mtumba, Gasper Lugela, Gineson Nkya, Daniel Chale, Richard Malisa, Sawaya Msangi, Ally Idrisa, Francis Chambo, Kusa Mchaina, Neema Barua, Christian Msokame, Rogers Msangi, Salome Simba, Hatibu Athumani, Mwanaidi Mtui, Rehema Mtibusa, Jumaa Akida, Ambele Yatinga, and Tilaus Gustav. We also acknowledge the finance, administrative, and logistic support team at National Institute for Medical Research (NIMR): Christopher Masaka, Millen Meena, Beatrice Mwampeta, Gracia Sanga, Neema Manumbu, Halfan Mwanga, Arison Ekoni, Twalipo Mponzi, Pendael Nasary, Denis Byakuzana, Alfred Sezary, Emmanuel Mnzava, John Samwel, Daud Mjema, Seth Nguhu, Thomas Semdoe, Sadiki Yusuph, Alex Mwakibinga, Rodrick Ulomi and Andrea Kimboi. We are also grateful to the management of the NIMR, National Malaria Control Program, and President's Office-Regional Administration and Local Government (regional administrative secretaries of the 10 regions, and district officials and staff from all 100 health facilities). Technical and logistics support from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation team is highly appreciated. The following reagents were obtained through BEI Resources, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health: diagnostic plasmid containing the small subunit ribosomal RNA gene (18S) from Plasmodium falciparum, MRA-177; Plasmodium vivax, MRA-178; Plasmodium malariae, MRA-179; and Plasmodium ovale, MRA-180, contributed by Peter A. Zimmerman.

Disclaimer. Permission to publish the manuscript was sought and obtained from the Director General of NIMR.

Data availability . National malaria transmission data was provided by the National Malaria Control Programme in Dodoma and is available by contacting National Malaria Control Programme. All other data are available upon reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Financial support. This work was supported by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation (grant number 002202); and the National Institutes of Health (grant number K24AI134990 to J. J. J.)

References

- 1. World Health Organization (WHO) . World malaria report 2022. Geneva; WHO, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Akala HM, Watson OJ, Mitei KK, et al. Plasmodium interspecies interactions during a period of increasing prevalence of Plasmodium ovale in symptomatic individuals seeking treatment: an observational study. Lancet Microbe 2021; 2:e141–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Betson M, Clifford S, Stanton M, Kabatereine NB, Stothard JR. Emergence of nonfalciparum Plasmodium infection despite regular artemisinin combination therapy in an 18-month longitudinal study of Ugandan children and their mothers. J Infect Dis 2018; 217:1099–109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Mitchell CL, Topazian HM, Brazeau NF, et al. Household prevalence of Plasmodium falciparum, Plasmodium vivax, and Plasmodium ovale in the democratic republic of the Congo, 2013–2014. Clin Infect Dis 2021; 73: e3966–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Yman V, Wandell G, Mutemi DD, et al. Persistent transmission of Plasmodium malariae and Plasmodium ovale species in an area of declining plasmodium falciparum transmission in eastern Tanzania. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2019; 13:e0007414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Nguiffo-Nguete D, Nongley Nkemngo F, Ndo C, et al. Plasmodium malariae contributes to high levels of malaria transmission in a forest–savannah transition area in Cameroon. Parasites Vectors 2023; 16:31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Sendor R, Banek K, Kashamuka MM, et al. Epidemiology of Plasmodium malariae and Plasmodium ovale spp. in Kinshasa Province, Democratic Republic of Congo. Nat Commun 2023; 14:6618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sendor R, Mitchell CL, Chacky F, et al. Similar prevalence of Plasmodium falciparum and non-P. falciparum malaria infections among schoolchildren, Tanzania. Emerg Infect Dis 2023; 29:1143–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. World Health Organization (WHO) . Global technical strategy for malaria 2016–2030. Geneva: WHO, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Tarimo BB, Nyasembe VO, Ngasala B, et al. Seasonality and transmissibility of Plasmodium ovale in Bagamoyo district, Tanzania. Parasit Vectors 2022; 15:56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bousema T, Drakeley C. Epidemiology and infectivity of Plasmodium falciparum and Plasmodium vivax gametocytes in relation to malaria control and elimination. Clin Microbiol Rev 2011; 24:377–410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Collins WE, Jeffery GM. Plasmodium ovale: parasite and disease. Clin Microbiol Rev 2005; 18:570–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Holzschuh A, Gruenberg M, Hofmann NE, et al. Co-infection of the four major Plasmodium species: effects on densities and gametocyte carriage. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2022; 16:e0010760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Oriero EC, Amenga-Etego L, Ishengoma DS, Amambua-Ngwa A. Plasmodium malariae, current knowledge and future research opportunities on a neglected malaria parasite species. Crit Rev Microbiol 2021; 47:44–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Roucher C, Rogier C, Sokhna C, Tall A, Trape JF. A 20-year longitudinal study of Plasmodium ovale and Plasmodium malariae prevalence and morbidity in a West African population. PLoS One 2014; 9:e87169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Cook J, Xu W, Msellem M, et al. Mass screening and treatment on the basis of results of a Plasmodium falciparum-specific rapid diagnostic test did not reduce malaria incidence in zanzibar. J Infect Dis 2015; 211:1476–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Battle KE, Baird JK. The global burden of Plasmodium vivax malaria is obscure and insidious. PLoS Med 2021; 18:e1003799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. McManus KF, Taravella AM, Henn BM, Bustamante CD, Sikora M, Cornejo OE. Population genetic analysis of the DARC locus (Duffy) reveals adaptation from standing variation associated with malaria resistance in humans. PLOS Genet 2017; 13:e1006560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Rahimi BA, Thakkinstian A, White NJ, Sirivichayakul C, Dondorp AM, Chokejindachai W. Severe vivax malaria: a systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical studies since 1900. Malar J 2014; 13:481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Schäfer C, Zanghi G, Vaughan AM, Kappe SHI. Plasmodium vivax latent liver stage infection and relapse: biological insights and new experimental tools. Annu Rev Microbiol 2021; 75:87–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Howes RE, Patil AP, Piel FB, et al. The global distribution of the Duffy blood group. Nat Commun 2011; 2:266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Leang R, Taylor WRJ, Bouth DM, et al. Evidence of Plasmodium falciparum malaria multidrug resistance to artemisinin and piperaquine in western Cambodia: dihydroartemisinin-piperaquine open-label multicenter clinical assessment. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2015; 59:4719–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Auburn S, Getachew S, Pearson RD, et al. Genomic analysis of Plasmodium vivax in southern Ethiopia reveals selective pressures in multiple parasite mechanisms. J Infect Dis 2019; 220:1738–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Twohig KA, Pfeffer DA, Baird JK, et al. Growing evidence of Plasmodium vivax across malaria-endemic Africa. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2019; 13:e0007140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Sutherland CJ. Persistent parasitism: the adaptive biology of malariae and ovale malaria. Trends Parasitol 2016; 32:808–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Mitchell CL, Brazeau NF, Keeler C, et al. Under the radar: epidemiology of Plasmodium ovale in the democratic republic of the Congo. J Infect Dis 2021; 223:1005–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Mueller I, Zimmerman PA, Reeder JC. Plasmodium malariae and Plasmodium ovale—the ‘bashful’ malaria parasites. Trends Parasitol 2007; 23:278–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Gumbo A, Topazian HM, Mwanza A, et al. Occurrence and distribution of nonfalciparum malaria parasite species among adolescents and adults in Malawi. J Infect Dis 2022; 225:257–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Mbama Ntabi JD, Lissom A, Djontu JC, et al. Prevalence of non-Plasmodium falciparum species in southern districts of Brazzaville in the republic of the Congo. Parasit Vectors 2022; 15:209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hawadak J, Dongang Nana RR, Singh V. Global trend of Plasmodium malariae and Plasmodium ovale spp. malaria infections in the last two decades (2000–2020): a systematic review and meta-analysis. Parasit Vectors 2021; 14:297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. World Health Organization (WHO) . Malaria rapid diagnostic test performance. Geneva: WHO, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Yerlikaya S, Campillo A, Gonzalez IJ. A systematic review: performance of rapid diagnostic tests for the detection of Plasmodium knowlesi, Plasmodium malariae, and Plasmodium ovale monoinfections in human blood. J Infect Dis 2018; 218:265–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Wittenauer R, Nowak S, Luter N. Price, quality, and market dynamics of malaria rapid diagnostic tests: analysis of global fund 2009–2018 data. Malar J 2022; 21:12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. National Malaria Control Programme . Malaria surveillance bulletin, 2022. Dodoma, Tanzania: National Malaria Control Programme, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 35. World Health Organization (WHO) . WHO guidelines for malaria. Geneva: WHO, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Rogier E, Battle N, Bakari C, et al. Plasmodium falciparum pfhrp2 and pfhrp3 gene deletions among patients enrolled at 100 health facilities throughout Tanzania: February to July 2021. medRxiv, doi: 2023.07.29.23293322, 5 August 2023, preprint: not peer reviewed. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. World Health Organization (WHO) . Master protocol for surveillance of pfhrp2. Geneva: WHO, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Plowe C V, Djimdé A, Bouaré M, Doumbo O, Wellems TE. Pyrimethamine and proguanil resistance-conferring mutations in Plasmodium falciparum dihydrofolate reductase: polymerase chain reaction methods for surveillance in Africa. Am J Trop Med Hyg 1995; 52:565–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Brazeau NF, Mitchell CL, Morgan AP, et al. The epidemiology of Plasmodium vivax among adults in the democratic republic of the Congo. Nat Commun 2021; 12:4169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Massicotte P, South A. rnaturalearth: world map data from natural earth https://cran.r-project.org/package=rnaturalearth. 8 July 2023.

- 41. Mitchell CL, Ngasala B, Janko MM, et al. Evaluating malaria prevalence and land cover across varying transmission intensity in Tanzania using a cross-sectional survey of school-aged children. Malar J 2022; 21:80. . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Abdulraheem MA, Ernest M, Ugwuanyi I, et al. High prevalence of Plasmodium malariae and Plasmodium ovale in co-infections with Plasmodium falciparum in asymptomatic malaria parasite carriers in southwestern Nigeria. Int J Parasitol 2022; 52:23–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Andolina C, Rek JC, Briggs J, et al. Sources of persistent malaria transmission in a setting with effective malaria control in eastern Uganda: a longitudinal, observational cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis 2021; 21:1568–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Walldorf JA, Cohee LM, Coalson JE, et al. School-age children are a reservoir of malaria infection in Malawi. PLoS One 2015; 10:e0134061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Lo E, Nguyen K, Nguyen J, et al. Plasmodium malariae prevalence and csp gene diversity, Kenya, 2014 and 2015. Emerg Infect Dis 2017; 23:601–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Kim MJ, Jung BK, Chai JY, et al. High malaria prevalence among schoolchildren on Kome Island, Tanzania. Korean J Parasitol 2015; 53:571–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Msellem M, Kemere J, Mårtensson A, et al. Prevalence of PCR detectable malaria infection among febrile patients with a negative Plasmodium falciparum specific rapid diagnostic test in Zanzibar. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2013; 88:289–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. US President's malaria initiative. Tanzania (mainland) malaria operational plan FY 2023. 5 October 2023.

- 49. Groger M, Veletzky L, Lalremruata A, et al. Prospective clinical and molecular evaluation of potential Plasmodium ovale curtisi and wallikeri relapses in a high-transmission setting. Clin Infect Dis 2019; 69:2119–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.