Summary

Hong Kong is a natural laboratory for studying suicides—small geographic footprint, bustling economic activity, rapidly changing socio–demographic transitions, and cultural crossroads. Its qualities also intensify the challenges posed when seeking to prevent them. In this viewpoint, we showed the research and practices of suicide prevention efforts made by the Hong Kong Jockey Club Centre for Suicide Research and Prevention (CSRP), which provide the theoretical underpinning of suicide prevention and empirical evidence. CSRP adopted a multi-level public health approach (universal, selective and indicated), and has collaboratively designed, implemented, and evaluated numerous programs that have demonstrated effectiveness in suicide prevention and mental well-being promotion. The center serves as a hub and a catalyst for creating, identifying, deploying, and evaluating suicide prevention initiatives, which have the potential to reduce regional suicides rates when taken to scale and sustained.

Keywords: Suicide, Suicide prevention, Public health

Overview

WHO has estimated that over 700,000 deaths were attributed to suicide globally in 2019 (1.3% of all deaths), ranking it as the 17th leading cause.1 The United Nations aims in its Sustainable Development Goals to reduce by one-third premature mortality from non-communicable diseases by 2030. Suicide is one of its key indicators (Target 3.4.2).2 Previously, Zalsman and colleagues posited seven types of interventions for preventing suicide: education, media guidelines, screening, restriction of suicidal means, pharmacological and psychological treatments, and internet and/or hotline support.3 Beyond addressing individual and family needs, the design and implementation of prevention strategies must also be locally specific—considering diverse cultural, religious, community, and societal factors, as well as governmental policies.

Hong Kong presents unique opportunities to develop, implement, and assess suicide prevention programs, as well as continue to elucidate factors that contribute to these premature deaths. It was a British colony for more than 150 years, with China resuming sovereignty in 1997. Hong Kong is now a Special Administrative Region (SAR) with a population of about 7.4 million, primarily Cantonese-speaking residents4 densely packed within an area of only 1000 square kilometers.5 Hong Kong has well-developed governmental services, and more than 500 publicly and privately supported social service agencies.6

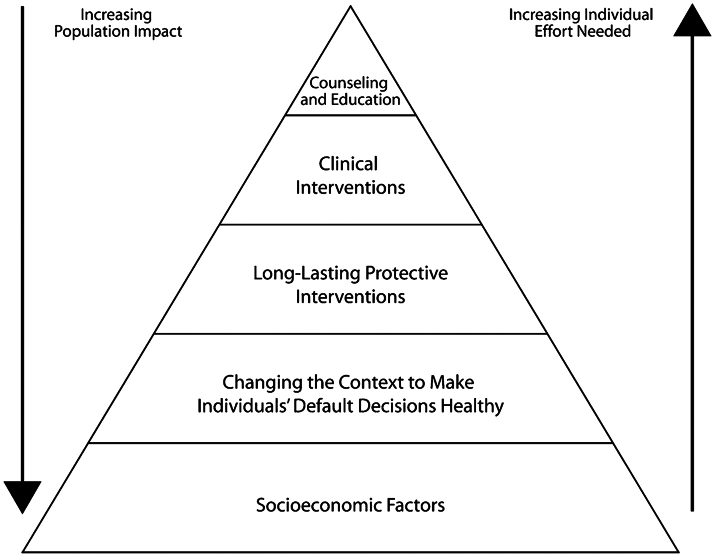

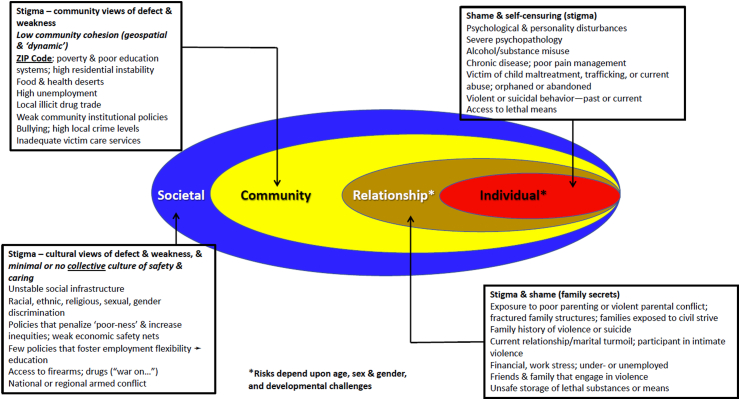

The work of the Centre for Suicide Research and Prevention (CSRP) has been built within an ecological framework (Fig. 1)8 that is nested in an overall public health approach to prevention and intervention that emphasizes both upstream and downstream impacts (Fig. 2).7,9,10 Fundamentally based on forming local coalitions and partnerships, it must accommodate the historically blended nature of Hong Kong society, which brings together individual (independent) and relational (interdependent) cultures.11 Interventions should focus not only on personal issues and developments, but also family dynamics and social relationships.12,13 Special attention is needed to address the roles of traditional culture and gender play in the Chinese society.14 It also has required that we look beyond the suicide-specific interventions, such as those listed by Zalsman et al.,3 to better understand broader economic and social factors that affect suicide rates. Thus, we have investigated broader social and economic forces, and in turn, sought to inform upstream policies and related resource allocation that potentially offer and strengthen downstream protective effects. In essence, our work has aimed to facilitate the care of persons who are distressed and suicidal, while building a foundation that prevents others from “becoming suicidal.” These efforts have followed a three-level population-oriented approach to prevention, involving universal, selective, and indicated initiatives—first described by Gordon,15 then broadly applied to mental disorders,16 and later focused specifically on suicide prevention.7,17, 18, 19

Fig. 1.

The health impact pyramid.7

Fig. 2.

Social-ecological Model: Mental health & social risks for violence to self and others (Modified from Caine, 2020).8

The characteristics that make Hong Kong a natural laboratory for studying suicides—small geographic footprint, a population that is larger than several European countries or many states in the United States, bustling economic activity, rapidly changing socio–demographic transitions, and being a crossroad between Eastern and Western cultures—also serve to intensify the challenges posed when seeking to prevent them. We have encountered sudden, dramatic increases in rates related to new diseases (e.g., severe acute respiratory syndrome [SARS] in 2003) and economic fluctuations (e.g., Asian financial crisis in 1997), rapid adoption of new methods, and sensational media reporting—all the while dealing with fragmented and disconnected mental health services that provide disparate resources for those who can afford private care in contrast to the general public.20

A central pillar of our work has been the abiding support from the Hong Kong Coroner's Court. Every unnatural fatality must be investigated by the Coroner's Court, integrating information gathered from police, family members, other related informants, medical professionals, and pathology reports to establish the cause and manner of death as classified by the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems 10th revision (ICD-10). Together with required confidentiality safeguards, CSRP has persistently built trust with the Coroner's Court, the Hong Kong Census and Statistics Department, the Police Department, and related stakeholders to assemble a comprehensive, valid and reliable database regarding every suicide death in the SAR. With this support, we have managed to provide the most comprehensive and accurate suicide information for Hong Kong and have conducted psychological autopsy studies,21, 22, 23 continually monitored emerging trends, built a library of investigations to explore the complexities of suicide in Hong Kong,24, 25, 26, 27, 28 and set the scientific foundation for evaluating potential preventive interventions.

Suicide trends in Hong Kong

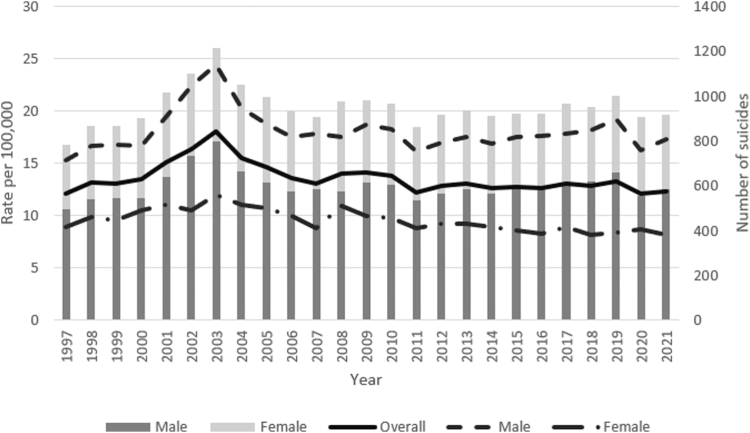

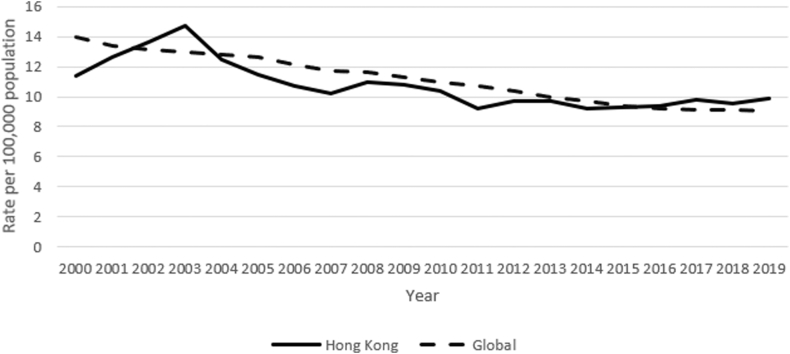

Fig. 3 shows the suicide rate per 100,000 population and the number of suicide cases by sex from 1997 to 2021. The crude rate increased from 11.9 per 100,000 population in 1997 (784 deaths) to a peak of 18.0 per 100,000 (1212 deaths) in 2003, followed by a decline to 13.1 per 100,000 in 2007 (905 deaths). A decomposition analysis revealed that this decrease was largely attributable to reduced jumping from heights among females and fewer hanging fatalities among males.29 At the same time, the analysis suggested that population aging was adding to the local burden. Indeed, the rate rebounded to about 14 during the period 2008–2010 and levelled off at around 13 since then.30 Males have experienced a consistently higher rate than females, with a ratio of about 2:1 during the past 20 years. It was suggested that the sex difference was attributed to the choice of suicide method, which males were more likely to choose highly lethal methods.25 Common suicide methods in Hong Kong include jumping from heights (hereafter as jumping) (55%), hanging (20%), and charcoal burning (15%),31 together accounting for 90% of all deaths.32 The age-standardized rate in Hong Kong was higher than the global average during the SARs epidemic in 2003 and it had been improving since then. However, it was slightly higher than the global rate since 2016 (Fig. 4).33

Fig. 3.

Suicide rate by sex in Hong Kong, 1997–2021.

Fig. 4.

Age-standardized suicide rate, 2000–2019.

Establishing the Hong Kong Jockey Club Centre for Suicide Research and Prevention (CSRP)

It was increasing concern about rising suicide rates beginning in 1997 that prompted the establishment of CSRP in 2002. From the outset, it was built collaboratively by the Faculty of Social Sciences at the University of Hong Kong with support from the Hong Kong SAR Government and the Hong Kong Jockey Club Charities Trust. Within a year, the SARS epidemic hit Hong Kong, and while only lasting three months, it triggered a sharp economic downturn and an unstable employment environment. The unemployment rate soon hit a historical high of 8.3%.34 Further, Leslie Cheung, a famous singer and an actor in Asia, killed himself on April 1, 2003, by jumping from a five-star luxury hotel in Hong Kong's crowded business district. The SARS epidemic35 and the celebrity suicide with its ensuing hyperbolic media coverage36 quickly coalesced with the emergence during the late- 1990s of new method of suicide, carbon monoxide poisoning arising from burning charcoal in a closed room, to accelerate the rate of suicide to the 2003 peak, a perfect storm situation.29

Responding to these crises helped shape the directions taken in CSRP during the past two decades. These have included: regularly taking the pulse of local trends and keeping key stakeholders well informed and involved; establishing a focus on means control for methods that may be constrained; identifying vulnerable populations (e.g., people discharged from public hospitals following a suicide attempt); developing pre-emptive programs with community collaborators; building working relationships with local media; using internet and social media to reach diverse groups; and striving to move upstream from reactive initiatives to those that have broader preventive impacts. One of the earliest endeavors was to form an international advisory committee, chaired by the Secretary of Justice of the Hong Kong SAR Government at the time (Ms. Elsie Leung), with the participation from established suicide prevention researchers with a diverse background including psychiatrists, public health professionals, social workers, sociologists, and pathologists. Their input and support were especially vital during our early years as we clarified the identity of CSRP as a research and training hub.

Suicide prevention efforts by CSRP

For purposes of this overview, we consider prevention efforts thematically. However, such initiatives are rarely discrete; rather, they depend on the alignment and collaboration of diverse partners in order to design, implement, and evaluate collective prevention programs. With CSRP being developed in the Faculty of Social Sciences, in collaboration with the Faculty of Science, and Faculty of Medicine at HKU, we have focused primarily on public health, population, psychosocial and community-based approaches to understanding the heterogeneity and complexity of suicide, and the challenges to prevention that occur at multiple levels.37 At the same time, we have the flexibility to link our data systems with clinical care providers to assist their efforts to enhance continuity of care for high-risk patients recently discharged from hospitals.38,39

We next define key elements related to these prevention initiatives and summarize them in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of community-based and school-based programs.

| Site/Program | Year | Target population | Stakeholders involved other than CSRP | Approaches | Outcomes | Publications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Community-based program | ||||||

| Cheung Chau | 2002 | Visitors to Cheung Chau | Authoritative figure of local community; local mental health professionals; police officers; managers and owners of holiday flats; social work professionals | Identify at-risk visitors; refer and provide emergency support and counseling services; refuse renting holiday flats to persons alone; increase police patrol around the pier | Number of suicides by visitors reduced; longer-term evaluation still showed certain effectiveness | P. W. C. Wong et al., 2009 Yip et al., 2022 |

| Locking up barbecue charcoal | 2006–2007 | General public | Major retail chains of grocery stores | Remove all barbecue charcoal packs from open shelves and put them in locked shelves | Suicide by charcoal burning in the intervention district significantly reduced compared to control district | Yip et al., 2010 |

| Eastern District | 2008–2012 | General public | Police force; Hospital Authority; Housing Department; Social Welfare Department; Caritas Hong Kong | Gatekeeper training; Raise awareness through community programs and education; establish a referral system to appropriate services | Suicide rate in the district dropped to a rate lower than that of the rest of Hong Kong | Yeung et al., 2022 |

| Northern District | 2011–2015 | General public, particularly young people | Home Affairs Department; Labor Department; Social Welfare Department; Education Bureau; Housing Authority; Police Force; non-governmental organizations; local hospital | Strengthen local social service networks; early identification of at-risk people; gatekeeper training | Suicide cluster “disappear” after intervention | C. C. S. Lai et al., 2020 |

| Tackling suicide by helium | 2014–2015 | General public | Government of HKSAR, led by the Chief Secretary, Police Force, Fire Service Department, Coroner's Court, Poison Information Centre; local media; Hong Kong Press Council | Surveillance; identify risk and protective factors; engagement of media to promote responsible reporting; restricting the access to helium; public education | Most of the media reports have changed to document the painfulness of using the method and the danger of storing helium gas; the incidence of suicide by helium has reduced back to the level of pre-2012 when the elevation has first noted | Yip et al., 2017 |

| Wong Tai Sin District | 2021- | Older adults in the district | Salvation Army; oral history researcher; youth and young adult volunteers | Oral history; promote intergenerational support and sense of belonging | Project ongoing | – |

| School-based program | ||||||

| The Little Prince is Depressed | 2009–2011 | 3391 secondary 2–4 students from 12 schools | Teachers; school leaders; postgraduate counsellors and social workers | 12-session programs based on cognitive-behavioral approach in two phrases (professional-led and teacher-led) | No significant effect right after the intervention; longer-term reduction of depressive symptoms was noted; more positive attitude towards mental illnesses; improved knowledge of mental health | P. W. C. Wong et al., 2012 E. S. Y. Lai et al., 2016 |

| Professor Gooley and the Flame of Mind | 2012 | 498 secondary 1–2 students from 31 schools | Teachers; school leaders; parents | 12-week digital game-based learning | Effective in promoting mental health | Huen et al., 2016 |

| The Adventures of DoReMiFa | 2014–2015 | 459 primary 4–5 students from four schools | Teachers; school leaders; parents | 8-module digital game-based and school-based learning | Effective in improving mental health knowledge | Shum et al., 2019 |

Response to emerging suicide methods – charcoal burning, helium, and sodium nitrite

Fatal carbon monoxide poisoning from burning charcoal in a small, sealed room was first noted in Hong Kong in 1997, with graphic front page descriptions and pictures soon appearing in local tabloids. By 2001, charcoal burning had surged to become the second most common suicide method.31 The SARS-related economic turmoil together with Leslie Cheung's quickly added impetus. Later investigation revealed that the majority of early adopters were working middle-aged males with financial debts but without pre-existing mental illnesses.40

CSRP began to collaborate with an array of local stakeholders in 2002 to develop community-specific prevention initiatives. Our first targeted a suicide hotspot (see Table 1 for details), Cheung Chau, an outlying island famous for its holiday rental apartments.41 The majority of its suicides involved charcoal combustion and took advantage of the island's relative isolation, which would not have been possible in their homes. CSRP worked with the local authoritative committee, the police, owners of the holiday flats, and social work and mental health professionals to initiate a program aimed at identifying and intervening with visitors having apparent risk. Our evaluation suggested that these efforts were effective. Strategies such as not renting holiday houses to single individuals remain in place.42 However, there is a need to renew regular police patrols around the ferry pier to identify any distressed individuals and to install carbon monoxide detectors in each room of these holiday apartments. We have learnt the lesson of making use of the local community resources to deal with the local problem and they have developed some kind of ownership and leadership in solving the problem.

In 2006, we launched a quasi-experimental trial located in major supermarkets in one Hong Kong district, which moved barbecue charcoal bags from open shelves to those requiring assistance.43 Overall and charcoal-related suicide rates in the intervention district dropped significantly versus a similar comparison district. New Taipei City in Taiwan adopted a similar approach that showed promising immediate effects.44 Nonetheless, many corporate and local markets in Hong Kong have chosen not to continue the restriction measures concerning about the possible negative impact to their business.42 Indeed, it is challenging to sustain these sorts of efforts without the support from the community stakeholders, especially legislation to impose any sale restriction is difficult.

Timely monitoring of suicide provides warnings of emerging methods. A young man killed himself in 2012 by inhaling helium, which was followed by extensive media reporting. Thirty-seven suicides using helium were detected during the ensuing three years among the 2774 cases (1.3%) reported by the Coroner's Court. Learning from the painful lessons of charcoal burning, CSRP alerted collaborating partners—including police and fire services, coroners, pathologists, and media professionals—with emphatic support from top leadership in government. Together we developed recommendations for local reporting: not inadvertently glorifying decedents while seeking to avoid any detailed descriptions, nor indicating that inhaling helium was painless or distress-free. CSRP and the fire service department designed a poster and television announcements promoting safety, while also underscoring the potential legal liability associated with direct or online sales of helium canisters used in suicides.45 Following these efforts, the rate of helium suicides returned to its pre-2012 level. This collective process exemplified the necessary alignment of interests and actions required for an integrated public health intervention with the support of the Government.

Sodium nitrite recently emerged as another method,46 primarily among young people. Based on preliminary investigation finding that it is available for online purchase, we have sought and received cooperation from web-based shopping platform to limit sales (e.g., Taobao in Mainland China). However, resistance also has been encountered (e.g., Amazon). An international working group has been formed to deal with the spread of sodium nitrite.46 We hope to raise awareness of the substance without publicizing it to wider use. Training to treat these cases has been conducted by government forensic doctors for emergency ambulance staff to provide timely and appropriate rescue.

Response to sensational media reporting

Media—print, broadcast, web-based, and digital— are capable of positively promoting health and mental health, but they may spread misinformation or glorify ‘tragic’ deaths.47, 48, 49 Tabloid reporting in 1998 of a person dying “peacefully” from burning charcoal, along with vivid photographs, served to ignite a dramatic increase in its use.40,50 Since then, a revolution has transformed how information is delivered into one's hand, with the explosion of web-based and digital social media, the rise of “influencers” (aka, “Key Opinion Leaders—KOLs”) on forums that draw the attention of youths and young adults, and the growth of chat rooms and informal settings (e.g., text messaging) that can be conducive to bullying and shaming, in addition to building positive relationships. We have by necessity had to transform our efforts.

CSRP published in 2004, Recommendations on Suicide Reporting for Media for Media Professionals,51 and distributed in 2015 an updated version, Recommendations on Suicide Reporting & Online Information Dissemination for Media Professionals. The revised version, developed collaboratively with local media professionals, introduced new elements regarding digital and social media in addition to prior recommendations on suicide prevention. Fundamental to our engagement with editors and frontline journalists—a unique community with its own culture and practices—has been a consistent effort to build trust and serve mutual interests. These media professionals were not impressed with reporting standards and guidelines written by health and public health authorities. They did appreciate efforts to share research findings, and the latest data from Hong Kong and internationally. Together we crafted “recommendations” rather than guidelines. They now depend on our efforts to assure data reliability, validity, and transparency. CSRP gradually became a regular contributor to diverse media to promote mental health and suicide prevention. Additionally, we provide evidence-based perspectives on suicide incidents to support the quality of local and international reporting and commentary.

Open Up-24 hour online emotional support system

Suicide is the leading cause of death among young people aged 15–24 years in Hong Kong.52 Text messaging has become their major means of communication,53 preferred over help-seeking channels such as crisis hotlines. Texting can be fast and anonymous,54 and gives them full autonomy when seeking help from others—who, when, and how fast.

Open Up, an online crisis support service co-created and launched in October 2018 as a collaboration between CSRP and five local non-governmental organizations, provides text-based online counselling support to individuals aged 11 to 35.55 It allows users to anonymously seek help through four commonly used text-messaging applications (Facebook Messenger, SMS, WeChat, and WhatsApp), with its web portal open “24/7.” The apparent risks of users are categorized into four levels (crisis, high, medium, low), and interventions are provided accordingly. Open Up has served over 62,775 unique callers as of September 2023. Most users have connected with counsellors without any waiting time after they accept the Terms of Service.55 Over 60% of users who scored at “high”, or “crisis” risk levels reported reduced stress levels after receiving services.

Open Up experienced a sharp increase in contacts during the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, particularly among youths and young adults. By the fourth wave hitting Hong Kong in 2021, we did not observe a similar surge, potentially consistent with a degree of public resilience or adaptation,56 despite local data indicative of continuing distress.57

Open Up agencies have been working with schools to provide complementary support for students especially in the out-of-school period, and to offer a conduit to available community services. Artificial intelligence (AI) algorithms are now being applied to improve efficiency and impact, while generating copious text data suitable for quality improvement, rapid surveillance, and research.58,59 The Government is committed to providing continual support to the system and it will be incorporated in their future regular service for the young people. It is another example how the CSRP can co-create some good practice models with NGOs in small scale with positive evaluation results and then to be scaled up to the community level in a sustainable way.

Community-integrated programs

CSRP has viewed “community” both as a way of defining persons who live or work in a common area (e.g., Cheung Chau) and as a group who share common values or interests (e.g., journalists). Community programs are based on partnerships that include diverse stakeholders and processes that promote collective actions. The role of CSRP often has been catalytic—less to carry out tasks, rather offering information and expertise, facilitating discussions and planning, and supporting evaluation and related research. Sometimes, we conduct pilot studies to co-create some good practice model with stakeholders in the community.

Several examples are included in Table 1. The Eastern District Police Commander from 2006 to 2010 (Mr. Peter Morgon) invited CSRP to work with partners to develop an intervention program with particular attention to the increasing suicide rate among older adults.60 A second began in 2010 in Northern District when six young adults killed themselves by jumping from the same housing estates within four months. CSRP collaborated at the request of the Hong Kong Government with the Social Welfare Department and local non-governmental organizations to develop and deploy an integrated set of universal, selective, and indicated initiatives, which ultimately were associated with lowered local suicide rates.61

The rate of suicide in Hong Kong is a rapidly aging city, with its highest suicide rate among adults 60 years and older. CSRP and the Wong Tai Sin District, began in 2019 a wellness promotion program targeting older adults—aimed at enhancing mental wellbeing through fostering a sense of belonging and connection by offering intergenerational support. CSRP trains young community volunteers to visit older adults to record their life stories as part of an oral history project. The volunteers then write the stories into audio booklets, which are presented as gifts with small porcelain sculptures of older adults. The program, MIND – Me In a New Day, next aims to develop a service management system for identifying and connecting “hard-to-reach elderlies” who are considered “alienated” or “hidden”. We also need to leverage on the community resources to provide the home visitation team to be involved in the implementation.

Promoting mental health in school settings

A crisis hotline and a psychiatric clinic or hospital are reactive by their very nature. They respond to calls or people coming to their doors. CSRP has a proactive, upstream mission, as exemplified by its work with older adults and by its programs based for school-aged youth These have included one for secondary schools begun in 2005 based on a cognitive-behavioral model, “The Little Prince is Depressed.”62 An internet-based program, “Professor Gooley and the Flame of Mind,” was launched in 2012 to promote mental health using a positive youth development approach. This online role-playing game was found to be effective in promoting mental health knowledge and attitudes of seeking help among secondary school students.63 Another digital game-based learning program, “The Adventures of DoReMiFa,” was developed in 2014 for younger students, aged 9–11 years, using a combination of cognitive-behavioral and positive psychology models. The program showed improvements in mental health knowledge among participants, although limited evidence supported the effect of reducing anxiety.64 CSRP established the “Promoting Wellness in School” thematic network program in 2019, adapting components from positive psychology to develop a curriculum for kindergarten, primary and secondary school students aimed at promoting a positive attitude among students and improving their resilience towards stress.

Beyond top-down approaches, we also employ bottom-up strategies to encourage and empower students to become supporters of one another. CSRP launched the “Suicide Help Intervention through Education and Leadership Development for Students (S.H.I.E.L.D.S.).” Trained peer supporters are encouraged to take a leading role in developing school-based activities and programs for suicide prevention and wellness promotion. Formal evaluation has yet to occur, though feedback from participating teachers has been encouraging. The student-initiated programs have reinforced the importance of “nothing about us without us.” Their co-creation experiences with the advice from teachers and CSRP thus far has enhanced the capacity of participating schools for mental health program development.65

At the same time, such programs will not lead to lasting changes, given student turnover, unless school leaders invest in sustaining a culture that supports participation and mental health promotion. The mental health of teachers often has been overlooked due to excessive workload and the examination-orientated, packed school curriculum. Thus, CSRP has held well-received workshops aimed at teachers—for Mental Health First Aid certification, as well as courses to introduce self-care programs involving music therapy, expressive arts therapy, and mindfulness-based cognitive therapy.

A blueprint for suicide prevention was developed and used in the school system in Hong Kong.66 Despite all efforts to date, suicides among youth in Hong Kong remain a recurring challenge. It requires a change of mindset of stakeholders in the education system to make the curriculum less examination oriented and more space in time and mind to develop their mental wellbeing in schools. For those who are not academically gifted, alternatives and upward mobility are much needed to see the hope in the future. School teachers need to be better supported with mental health training and providing more time and space to build up a strong relationship with students. The parental relationship is one of the important concerns detected in suicide notes left amongst young people.27 A holistic approach involving all the significant others of students is needed and communication between the school and parents has much more room to be improved. Some of these strategies may be applicable to other settings—e.g., Mainland China, Japan, South Korea, and other countries where the educational systems are especially intensive and future opportunities are dependent on examination results.

Perspectives, lessons, limitations, and challenges

Public health research must reach far beyond disease processes to better understand policies, practices, and driving external forces that profoundly influence community, family, and individual wellbeing and suicide rates. Hong Kong's unique economic position in east-west trade and financial services leaves it potentially vulnerable to powerful fluctuations. The economic crises associated with the first SARS epidemic in 2003 and the COVID-19 pandemic set the stage for examining such influences on suicide rates.67, 68, 69 CSRP has investigated the relationships between community level social factors, mental health, and suicide. Using the Geographic Information System (GIS) and spatial analysis, we have examined the small-area suicide risks in Hong Kong, and whether spatial clusters with elevated suicide risks existed.32,70, 71, 72 We concluded that social deprivation (i.e., the disadvantage in accessing material and/or social resources) was associated with suicide at the community-level.

There have been important lessons from our work. It is within the purview of public health research to better define the impacts of external events and current policies, and to inform leaders regarding the implications for current and future practices. At the same time, it has been beyond the scope of CSRP or other academic institutions to determine or implement broad social policies. Even as we have sought to initiate public health and population approaches to suicide prevention, we have not focused on the care of individuals who are severely suicidal or who have made suicide attempts. These individuals require expertise in applying clinically effective therapeutics and the timely availability of these needed treatments. Hong Kong, like many nations and regions, faces serious challenges in offering such services due to a shortage of mental health professionals and without coordinated efforts, prevention of premature deaths remains a daunting challenge. The emphasis of suicide prevention should shift from illness treatment to wellness promotion especially for those societies which are constrained by the insufficient provision of mental health care services.

Having a sustained and effective relationship with the Coroner's Court has been fundamental to our work, which underscores the necessity of accurately defining the nature of the problem we face. However, an essential ingredient for the high reliability and validity of the derived data involves thorough investigation, which often involves lengthy periods of time and as much as six months to an occasional three years or longer.73

In response, we have developed a Suicide Early Warning System to perform daily “nowcasting” as one way of mitigating this limitation – and an approach being developed internationally. We collect suicide-related news reporting through diverse media channels; as not every suicide is reported publicly, we then estimate the number of total cases daily using machine learning algorithms. We further compare this number to that of the same period during the prior year and issue a series of warning signals (low, medium, high, crisis) to estimate the current situation in Hong Kong.

Through research and practice, we have shown the promise of many prevention initiatives. Yet, they ultimately fail to save lives if they are not implemented widely, vigorously sustained, and reinforced through consistent evaluation and quality improvement with resources. Making the purchase of charcoal bags slightly more cumbersome proved effective in our quasi-experimental design.43 Nonetheless, we never have been able to establish region-wide adoption of this measure. Retail chains and local grocery stores assert that this would require too much extra work and increase their costs. However much as there is stated agreement on the value of saving lives, it remains challenging to build consensus for collective actions, or assemble all of the pieces necessary to construct a coherent picture, a mosaic of suicide prevention and mental health promotion.7 Nevertheless, the recent movement of the social corporate responsibility on environmental, social and governance (ESG) could lead to some changes.

With the collaborative effort with many important stakeholders in the community, CSRP has been able to demonstrate effects of these initiatives with scientific evidence that offer promises for youths and young adults, and for older people. The ultimate measure of success for CSRP or any similar academic enterprise remains the reduction of suicides. So far, the rate in Hong Kong has seen to return to the levels recorded before the use of charcoal burning and the onset of SARS in 2003 after taking into consideration of ageing problem in Hong Kong. The age-standardized suicide rate in 2022 (1997 Hong Kong population as reference) has been estimated to be 10.9 per 100,000 population, which was still lower than the crude rate of 11.9 in 1997.

Conclusion

The information and digital revolutions require that we work apace with this constant state of innovation. CSRP continues to explore the use of different advanced and emerging methods and technologies. Artificial intelligence (AI), natural language processing (NLP), and machine learning (ML) are tools being adapted to evaluate risk and potentially prevent suicide.74, 75, 76 The recent emergence of Generative Pre-Trained Transformer (GPT) offers more, as yet unseen opportunities for prevention and mental health promotion in social media.77 Apart from advanced technologies, other behavioral strategies and culturally relevant interventions, such as the use of expressive arts (music, play and drama, etc.) therapy and physical activities,78,79 should be evaluated for their effectiveness and relevancy for older persons, as well as distressed and suicidal individuals, many of whom may be less open to traditional “talk therapies.”

We must never stop pushing boundaries while building bridges, embracing hope, seeking to prevent suicide, and promoting mental health locally and globally. We have forged new alliances and initiated multiple research projects: CSRP has always taken steps to put prevention and intervention initiatives into trials and actions. Not every step has been successful, but they shed light on further directions to pursue. It is likely that the 30% reduction in the rate of suicide from the peak in 2003 reflected the combined efforts of community stakeholders, together with the improved economy, reduced unemployment, and a major drop in the suicide rate among employed persons rather than the unemployed likely contributed to its reduction.80 Multidisciplinary and community-involved approaches and strategies should be encouraged. Recently, we have seen more during the COVID-19 pandemic which implementation of policies that buffer economic shocks can mitigate hardships. Long-term evaluation of different strategies, and their effectiveness in diverse cultural and geopolitical settings should be performed.

Suicide takes nearly 1000 lives annually in Hong Kong. Despite Hong Kong being one of the most developed regions globally (ranked 4th on Human Development Index), the ratio of psychiatrists to the population in Hong Kong is well below that in other developed communities.81,82 Nor has Hong Kong yet developed a regional plan for suicide prevention. In the meantime, we have been testing upstream interventions, seeking to provide a better environment, improve the quality of living, encourage future optimism among young people by enhancing education and training opportunities, and piloting the use of intergenerational connections for older adults. But promising programs have negligible public health impact if not widely disseminated, implemented with fidelity, sustained, and rigorously evaluated to assure that they are fulfilling their goals.

While suicide likely has been present in society for millennia, it is not a static social or population level process. Global environment, diverse and changing cultural norms, mass migrations, societal policies and community practices, as well as personal relationships and individual vulnerabilities, all can influence the incidence of self-inflicted deaths. The landscape around suicide has transformed especially rapidly during these past two decades, both in economically advanced nations and in those undergoing economic transformations and dislocations. These first two decades of the 21st century have witnessed increasing international tensions, and the world also has begun to experience dramatically increasing effects of global warming and climate change. Suicides are both a statement of personal tragedy and a painful indicator of broader social distress. These times put us on notice to work collaboratively, imaginatively, and with urgency. We always need to be inclusive, responsive to the ever-changing environment. For suicide prevention, one is too many and everyone can make a difference. Zero suicides might be impossible but at least we can move towards its direction.

Contributors

Conceptualization: Paul Siu Fai Yip; Eric D. Caine.

Supervision: Paul Siu Fai Yip.

Writing–original draft: Cheuk Yui Yeung; Paul Siu Fai Yip; Eric D. Caine.

Writing–review & editing: Yik Wa Law; Rainbow Tin Hung Ho.

Editor note

The Lancet Group takes a neutral position with respect to territorial claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Declaration of interests

None.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the useful comments and advice provided by the reviewers and the editor. The Hong Kong Jockey Club Centre for Suicide Research and Prevention has been supported by Hong Kong Jockey Club Charities Trust, the Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, many non-governmental organizations, donors and supporters since its establishment. This research is supported by the research grant (C7151-20G) and the Strategic Topic Grants Scheme (STG4/M-701/23-N) of the Research Grants Council of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, China. Funding sources were not involved in the study design; collection, analysis or interpretation of the data; in writing of the manuscript or in the decision to submit the manuscript for publication. The Centre expresses gratitude for the support provided by the Centre's International Advisory Committee, World Health Organization, many research collaborators and community stakeholders in advancing its efforts toward promoting suicide prevention initiatives locally and globally.

References

- 1.World Health Organization . 2021. Suicide.https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/suicide Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 2.United Nations Transforming our world: the 2030 agenda for sustainable development. 2015. https://sdgs.un.org/2030agenda Available from:

- 3.Zalsman G., Hawton K., Wasserman D., et al. Suicide prevention strategies revisited: 10-year systematic review. Lancet Psychiatr. 2016;3(7):646–659. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(16)30030-X. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S221503661630030X Available from: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Census and Statistics Department . 2022. 2021 population Census main results.https://www.census2021.gov.hk/doc/pub/21c-main-results.pdf Hong Kong. Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 5.The Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region . 2022. Hong Kong – the facts.https://www.gov.hk/en/about/abouthk/facts.htm Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hong Kong Council of Social Service . 2022. An overview of HKCSS's Agency members in 2021.https://ngo.hkcss.org.hk/overview_en Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 7.Caine E.D. Forging an agenda for suicide prevention in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(5):822–829. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.301078. https://ajph.aphapublications.org/doi/full/10.2105/AJPH.2012.301078 Available from: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Caine E.D. Building the foundation for comprehensive suicide prevention – based on intention and planning in a social–ecological context. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. 2020;29:e69. doi: 10.1017/S2045796019000659. https://www.cambridge.org/core/product/identifier/S2045796019000659/type/journal_article Available from: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Frieden T.R. A framework for public health action: the health impact pyramid. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(4):590–595. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.185652. https://ajph.aphapublications.org/doi/full/10.2105/AJPH.2009.185652 Available from: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yip P.S.F., Huen J.M., Lai E.S. Mental health promotion: challenges, opportunities, and future directions. Hong Kong J Ment Heal. 2012;38(2):5–14. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ho R.T.H. Growing to be independent in an interdependent culture: a reflection on the cultural adaptation of creative and expressive arts therapy in an Asian global city. Creat Arts Educ Ther. 2021;6(2):171–178. https://caet.inspirees.com/caetojsjournals/index.php/caet/article/view/251 Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chang Q., Chan C.H., Yip P.S.F. A meta-analytic review on social relationships and suicidal ideation among older adults. Soc Sci Med. 2017;191:65–76. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.09.003. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0277953617305282 Available from: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ji J., Kleinman A., Becker A.E. Suicide in contemporary China: a review of China's distinctive suicide demographics in their sociocultural context. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2001;9(1):1–12. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11159928 Available from: [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yip P.S.F., Yousuf S., Chan C.H., Yung T., Wu K.C.-C. The roles of culture and gender in the relationship between divorce and suicide risk: a meta-analysis. Soc Sci Med. 2015 Mar;128:87–94. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.12.034. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0277953614008429 Available from: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gordon R.S. An operational classification of disease prevention. Public Health Rep. 1983;98(2):107–109. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mrazek P.J., Robert J.H. National Academies Press; Washington, D.C.: 1994. Reducing risks for mental disorders: frontiers for preventive intervention research.http://www.nap.edu/catalog/2139 Available from: [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goldsmith S.K., Pellmar T.C., Kleinman A.M., Bunney W.E. National Academies Press; Washington, D.C.: 2002. Reducing suicide: a national imperative.http://www.nap.edu/catalog/10398 Available from: [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Knox K.L., Conwell Y., Caine E.D. If suicide is a public health problem, what are we doing to prevent it? Am J Public Health. 2004;94(1):37–45. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.1.37. https://ajph.aphapublications.org/doi/full/10.2105/AJPH.94.1.37 Available from: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yip P.S.F. Towards evidence-based suicide prevention programs. Crisis. 2011;32(3):117–120. doi: 10.1027/0227-5910/a000100. https://econtent.hogrefe.com/doi/10.1027/0227-5910/a000100 Available from: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hui C.L.-M., Suen Y., Lam B.Y.-H., et al. LevelMind@JC: development and evaluation of a community early intervention program for young people in Hong Kong. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2022;16(8):920–925. doi: 10.1111/eip.13261. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/eip.13261 Available from: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen E.Y.H., Chan W.S.C., Wong P.W.C., et al. Suicide in Hong Kong: a case-control psychological autopsy study. Psychol Med. 2006;36(6):815–825. doi: 10.1017/S0033291706007240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chiu H.F.K., Yip P.S.F., Chi I., et al. Elderly suicide in Hong Kong – a case-controlled psychological autopsy study. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2004;109(4):299–305. doi: 10.1046/j.1600-0447.2003.00263.x. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1046/j.1600-0447.2003.00263.x Available from: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wong P.W.C., Chan W.S., Chen E.Y., Chan S.S., Law Y., Yip P.S. Suicide among adults aged 30–49: a psychological autopsy study in Hong Kong. BMC Public Health. 2008;8(1):147. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-8-147. https://bmcpublichealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1471-2458-8-147 Available from: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yip P.S.F., Lee D.T.S. Charcoal-burning suicides and strategies for prevention. Crisis. 2007;28(SUPPL. 1):21–27. doi: 10.1027/0227-5910.28.S1.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cai Z., Chang Q., Yip P.S.F., Conner A., Azrael D., Miller M. The contribution of method choice to gender disparity in suicide mortality: a population-based study in Hong Kong and the United States of America. J Affect Disord. 2021;294:17–23. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2021.06.063. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0165032721006492 Available from: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chai Y., Luo H., Zhang Q., Cheng Q., Lui C.S.M., Yip P.S.F. Developing an early warning system of suicide using Google Trends and media reporting. J Affect Disord. 2019;255(May):41–49. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2019.05.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hsu Y.C., Junus A., Zhang Q., et al. A network approach to understand co-occurrence and relative importance of different reasons for suicide: a territory-wide study using 2002–2019 Hong Kong Coroner's Court reports. Lancet Reg Health West Pac. 2023;36 doi: 10.1016/j.lanwpc.2023.100752. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S2666606523000706 Available from: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Men V.Y., Emery C.R., Yip P.S.F. Characteristics of cancer patients who died by suicide: a quantitative study of 15-year coronial records. Psycho Oncol. 2021;30(7):1051–1058. doi: 10.1002/pon.5634. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/pon.5634 Available from: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yang C.-T., Yip P.S.F. Changes in the epidemiological profile of suicide in Hong Kong: a 40-year retrospective decomposition analysis. China Popul Dev Stud. 2021;5(2):153–173. doi: 10.1007/s42379-021-00087-5. https://link.springer.com/10.1007/s42379-021-00087-5 Available from: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Centre for Suicide Research and Prevention . 2022. Statistics.https://csrp.hku.hk/statistics/ Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 31.Men V.Y., Yeung C.Y., Yip P.S.F. In: Suicide risk assessment and prevention [internet] Pompili M., editor. Springer International Publishing; Cham: 2021. The evolution of charcoal burning suicides in Hong Kong, 1997–2018; pp. 1–19.https://link.springer.com/10.1007/978-3-030-41319-4_74-1 Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yeung C.Y., Men Y.V., Caine E.D., Yip P.S.F. The differential impacts of social deprivation and social fragmentation on suicides: a lesson from Hong Kong. Soc Sci Med. 2022 Dec;315 doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2022.115524. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0277953622008309 Available from: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.World Health Organization Age-standardized suicide rates (per 100 000 population) 2022. https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/indicators/indicator-details/GHO/age-standardized-suicide-rates-(per-100-000-population) Available from:

- 34.Chan W.S.C., Yip P.S.F., Wong P.W.C., Chen E.Y.H. Suicide and unemployment: what are the missing links? Arch Suicide Res. 2007;11(4):327–335. doi: 10.1080/13811110701541905. http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/13811110701541905 Available from: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cheung Y.T., Chau P.H., Yip P.S.F. A revisit on older adults suicides and Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) epidemic in Hong Kong. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2008;23(12):1231–1238. doi: 10.1002/gps.2056. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/gps.2056 Available from: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yip P.S.F., Fu K.W., Yang K.C.T., et al. The effects of a celebrity suicide on suicide rates in Hong Kong. J Affect Disord. 2006;93(1–3):245–252. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2006.03.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Law Y.W., Yeung T.L., Ip F.W.L., Yip P.S.F. Evidence-based suicide prevention: collective impact of engagement with community stakeholders. J Evid Based Soc Work. 2019;16(2):211–227. doi: 10.1080/23761407.2019.1578318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Law Y.W., Lok R.H.T., Chiang B., et al. Effects of community-based caring contact in reducing thwarted belongingness among postdischarge young adults with self-harm: randomized controlled trial. JMIR Form Res. 2023;7 doi: 10.2196/43526. https://formative.jmir.org/2023/1/e43526 Available from: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Law Y.W., Yip P.S.F., Lai C.C.S., et al. A pilot study on the efficacy of volunteer mentorship for young adults with self-harm behaviors using a quasi-experimental design. Crisis. 2016;37(6):415–426. doi: 10.1027/0227-5910/a000393. https://econtent.hogrefe.com/doi/10.1027/0227-5910/a000393 Available from: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chan K.P.M., Yip P.S.F., Au J., Lee D.T.S. Charcoal-burning suicide in post-transition Hong Kong. Br J Psychiatry. 2005;186(1):67–73. doi: 10.1192/bjp.186.1.67. https://www.cambridge.org/core/product/identifier/S0007125000230377/type/journal_article Available from: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wong P.W.C., Liu P.M.Y., Chan W.S.C., et al. An integrative suicide prevention program for visitor charcoal burning suicide and suicide pact. Suicide Life-Threatening Behav. 2009;39(1):82–90. doi: 10.1521/suli.2009.39.1.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yip P.S.F., Yeung C.Y., Chen Y., Lai C.C.S., Wong C.L.H. An evaluation of the long-term sustainability of suicide prevention programs in an offshore Island. Suicide Life-Threatening Behav. 2022;52(1):4–13. doi: 10.1111/sltb.12764. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/sltb.12764 Available from: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yip P.S.F., Law C.K., Fu K.-W., Law Y.W., Wong P.W.C., Xu Y. Restricting the means of suicide by charcoal burning. Br J Psychiatry. 2010;196(3):241–242. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.109.065185. https://www.cambridge.org/core/product/identifier/S0007125000251921/type/journal_article Available from: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chen Y.Y., Chen F., Chang S.-S., Wong J., Yip P.S.F. Assessing the efficacy of restricting access to barbecue charcoal for suicide prevention in Taiwan: a community-based intervention trial. PLoS One. 2015;10(8) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0133809. Niederkrotenthaler T. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yip P.S.F., Cheng Q., Chang S.-S., et al. A public health approach in responding to the spread of helium suicide in Hong Kong. Crisis. 2017;38(4):269–277. doi: 10.1027/0227-5910/a000449. https://econtent.hogrefe.com/doi/10.1027/0227-5910/a000449 Available from: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sinyor M., Fraser L., Reidenberg D., Yip P.S.F., Niederkrotenthaler T. The kenneth Law media event – a dangerous natural experiment. Crisis. 2024;45(1):1–7. doi: 10.1027/0227-5910/a000942. https://econtent.hogrefe.com/doi/10.1027/0227-5910/a000942 Available from: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hawton K., Williams K. Influences of the media on suicide. BMJ. 2002;325(7377):1374–1375. doi: 10.1136/bmj.325.7377.1374. https://www.bmj.com/lookup/doi/10.1136/bmj.325.7377.1374 Available from: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pirkis J., Blood R.W. Suicide and the media Part I: reportage in nonfictional media. Cris J Cris Interv Suicide Prev. 2001;22(4):146–154. doi: 10.1027//0227-5910.22.4.146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Niederkrotenthaler T., Braun M., Pirkis J., et al. Association between suicide reporting in the media and suicide: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2020;368(March):1–17. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yeung C.Y., Men V.Y., Yip P.S.F. The evolution of charcoal-burning suicide: a systematic scoping review. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2023;57(3):344–361. doi: 10.1177/00048674221114605. http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/00048674221114605 Available from: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fu K.W., Yip P.S.F. Changes in reporting of suicide news after the promotion of the WHO media recommendations. Suicide Life-Threatening Behav. 2008;38(5):631–636. doi: 10.1521/suli.2008.38.5.631. http://www.atypon-link.com/GPI/doi/abs/10.1521/suli.2008.38.5.631 Available from: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yip P.S.F., Chan W.-L., Chan C.S., et al. The opportunities and challenges of the first three years of open up, an online text-based counselling service for youth and young adults. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(24) doi: 10.3390/ijerph182413194. https://www.mdpi.com/1660-4601/18/24/13194 Available from: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ehrenreich S.E., Beron K.J., Burnell K., Meter D.J., Underwood M.K. How adolescents use text messaging through their high school years. J Res Adolesc. 2020;30(2):521–540. doi: 10.1111/jora.12541. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/jora.12541 Available from: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Evans W.P., Davidson L., Sicafuse L. Someone to listen: increasing youth help-seeking behavior through a text-based crisis line for youth. J Community Psychol. 2013;41(4):471–487. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/jcop.21551 Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yip P.S.F., Chan W.L., Cheng Q., et al. A 24-hour online youth emotional support: opportunities and challenges. Lancet Reg Health West Pac. 2020;4 doi: 10.1016/j.lanwpc.2020.100047. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S266660652030047X Available from: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chan C.S., Yang C.-T., Xu Y., He L., Yip P.S.F. Variability in the psychological impact of four waves of COVID-19: a time-series study of 60 000 text-based counseling sessions. Psychol Med. 2023;53(9):3920–3931. doi: 10.1017/S0033291722000587. https://www.cambridge.org/core/product/identifier/S0033291722000587/type/journal_article Available from: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Fong T.C.T., Chang K., Ho R.T.H. Association between quarantine and sleep disturbance in Hong Kong adults: the mediating role of COVID-19 mental impact and distress. Front Psychiatry. 2023;14 doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2023.1127070. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyt.2023.1127070/full Available from: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Xu Z., Xu Y., Cheung F., et al. Detecting suicide risk using knowledge-aware natural language processing and counseling service data. Soc Sci Med. 2021;283 doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.114176. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0277953621005086 Available from: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Xu Z., Chan C.S., Zhang Q., et al. Network-based prediction of the disclosure of ideation about self-harm and suicide in online counseling sessions. Commun Med. 2022;2(1):156. doi: 10.1038/s43856-022-00222-4. https://www.nature.com/articles/s43856-022-00222-4 Available from: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yeung C.Y., Morgan P.R., Lai C.C.S., Wong P.W.C., Yip P.S.F. Short- and long-term effects of a community-based suicide prevention program: a Hong Kong experience. Suicide Life-Threatening Behav. 2022;52(3):515–524. doi: 10.1111/sltb.12842. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/sltb.12842 Available from: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lai C.C.S., Law Y.W., Shum A.K.Y., Ip F.W.L., Yip P.S.F. A community-based response to a suicide cluster: a Hong Kong experience. Crisis. 2020;41(3):163–171. doi: 10.1027/0227-5910/a000616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wong P.W.C., Fu K.-W., Chan K.Y.K., et al. Effectiveness of a universal school-based programme for preventing depression in Chinese adolescents: a quasi-experimental pilot study. J Affect Disord. 2012;142(1–3):106–114. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2012.03.050. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0165032712002534 Available from: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Huen J.M., Lai E.S., Shum A.K., et al. Evaluation of a digital game-based learning program for enhancing youth mental health: a structural equation modeling of the program effectiveness. JMIR Ment Health. 2016;3(4):e46. doi: 10.2196/mental.5656. http://mental.jmir.org/2016/4/e46/ Available from: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Shum A.K., Lai E.S., Leung W.G., et al. A digital game and school-based intervention for students in Hong Kong: quasi-experimental design. J Med Internet Res. 2019;21(4) doi: 10.2196/12003. https://www.jmir.org/2019/4/e12003/ Available from: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wong A., Szeto S., Lung D.W.M., Yip P.S.F. Diffusing innovation and motivating change: adopting a student-Led and whole-school approach to mental health promotion. J Sch Health. 2021;91(12):1037–1045. doi: 10.1111/josh.13094. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/josh.13094 Available from: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Committee on Prevention of Student Suicides Final report by the committee on prevention of student suicides. 2016. https://mentalhealth.edb.gov.hk/uploads/mh/content/document/The_Committee_on_Prevention_of_Student_Suicide_Final_Report_Nov_2016.pdf Available from:

- 67.Pirkis J., Gunnell D., Shin S., et al. Suicide numbers during the first 9-15 months of the COVID-19 pandemic compared with pre-existing trends: an interrupted time series analysis in 33 countries. eClinicalMedicine. 2022;51 doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2022.101573. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S2589537022003030 Available from: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Sinyor M., Hawton K., Appleby L., et al. The coming global economic downturn and suicide: a call to action. Nat Ment Health. 2023;1(4):233–235. https://www.nature.com/articles/s44220-023-00042-y Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 69.Chen Y.-Y., Yang C.-T., Yip P.S.F. The increase in suicide risk in older adults in Taiwan during the COVID-19 outbreak. J Affect Disord. 2023;327:391–396. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2023.02.006. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S016503272300160X Available from: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Guo Y., Chau P.P.H., Chang Q., Woo J., Wong M., Yip P.S.F. The geography of suicide in older adults in Hong Kong: an ecological study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2020;35(1):99–112. doi: 10.1002/gps.5225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hsu C.Y., Chang S.S., Lee E.S.T., Yip P.S.F. Geography of suicide in Hong Kong: spatial patterning, and socioeconomic correlates and inequalities. Soc Sci Med. 2015;130:190–203. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Yeung C.Y., Men V.Y., Guo Y., Yip P.S.F. Spatial–temporal analysis of suicide clusters for suicide prevention in Hong Kong: a territory-wide study using 2014–2018 Hong Kong Coroner's Court reports. Lancet Reg Health West Pac. 2023 doi: 10.1016/j.lanwpc.2023.100820. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S2666606523001384 Available from: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Cui J.S., Yip P.S.F., Chau P.H. Estimation of reporting delay and suicide incidence in Hong Kong. Stat Med. 2004;23(3):467–476. doi: 10.1002/sim.1604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Coppersmith G., Leary R., Crutchley P., Fine A. Natural Language processing of social media as screening for suicide risk. Biomed Inform Insights. 2018;10 doi: 10.1177/1178222618792860. http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/1178222618792860 Available from: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.D'Hotman D., Loh E. AI enabled suicide prediction tools: a qualitative narrative review. BMJ Health Care Inform. 2020;27(3) doi: 10.1136/bmjhci-2020-100175. https://informatics.bmj.com/lookup/doi/10.1136/bmjhci-2020-100175 Available from: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Lejeune A., Le Glaz A., Perron P.-A., et al. Artificial intelligence and suicide prevention: a systematic review. Eur Psychiatry. 2022;65(1):e19. doi: 10.1192/j.eurpsy.2022.8. https://www.cambridge.org/core/product/identifier/S0924933822000086/type/journal_article Available from: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Cheng S., Chang C., Chang W., et al. The now and future of ChatGPT and GPT in psychiatry. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2023;11 doi: 10.1111/pcn.13588. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/pcn.13588 Available from: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Davico C., Rossi Ghiglione A., Lonardelli E., et al. Performing arts in suicide prevention strategies: a scoping review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(22) doi: 10.3390/ijerph192214948. https://www.mdpi.com/1660-4601/19/22/14948 Available from: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Vancampfort D., Hallgren M., Firth J., et al. Physical activity and suicidal ideation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2018;225:438–448. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2017.08.070. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0165032717313745 Available from: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Yip P.S.F., Caine E.D. Employment status and suicide: the complex relationships between changing unemployment rates and death rates. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2011;65(8):733–736. doi: 10.1136/jech.2010.110726. https://jech.bmj.com/lookup/doi/10.1136/jech.2010.110726 Available from: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.mindhk . 2023. Mental health in Hong Kong.https://www.mind.org.hk/mental-health-in-hong-kong/ Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 82.United Nations Development Programme . 2022. Human development report 2021-2022.https://hdr.undp.org/content/human-development-report-2021-22 Available from: [Google Scholar]