Abstract

Incorporation of Vpx into human immunodeficiency virus type 2 (HIV-2) virus-like particles is mediated by the Gag polyprotein. We have identified residues 15 to 40 of Gag p6 and residues 73 to 89 of Vpx as being necessary for virion incorporation. In addition, we show enhanced in vitro binding of Vpx to a chimeric HIV-1/HIV-2 Gag construct containing residues 2 to 49 of HIV-2 p6 and demonstrate that the presence of residues 73 to 89 of Vpx allows for in vitro binding to HIV-2 Gag.

The genomes of lentiviruses encode several accessory proteins in addition to the essential Gag, Pol, and Env proteins. Vpx is an accessory protein which is found in human immunodeficiency virus type 2 (HIV-2) and in the simian immunodeficiency viruses (SIVs) SIVsmm, SIVmnd, and SIVmac but is absent from HIV-1 (1, 6). It has been speculated that the vpx gene is a result of the duplication of the vpr gene, which encodes another regulatory protein found in all lentiviruses (24), or arose through the acquisition of the vpr gene from SIVAGM (21). The proteins are similar in size (14 to 16 kDa), demonstrate amino acid sequence similarity, and are packaged within the virion. Vpx of HIV-2 and SIV is required for efficient viral replication in primary lymphocyte and monocyte cultures (5, 9, 16). It appears to be the primary determinant in these viruses for transport of the viral preintegration complex into the nuclei of quiescent cells (3).

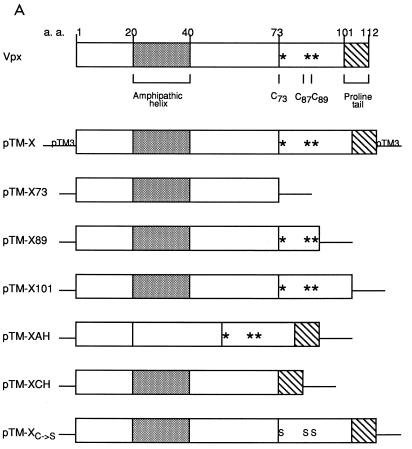

Vpx is packaged within the virion in molar amounts equivalent to those of the Gag proteins (4, 7), although it is dispensable for the assembly process (9). This stoichiometry suggests that specific interactions with Gag could mediate the packaging of Vpx. In addition, HIV-2 Vpx appears to colocalize with HIV-2 Gag at the inner surface of the plasma membrane of infected cells (10). Several conserved regions within Vpx could be involved in such an interaction with Gag, including (i) a predicted amphipathic helix between residues 20 and 40, (ii) three conserved cysteines at residues 73, 87, and 89, and (iii) a stretch of seven prolines at the C-terminal end of the protein (Fig. 1A). Park and Sodroski studied the amino acid requirements for the packaging of SIV Vpx and determined that residues 78 to 80 and 82 to 87 are important (18). Since the conserved cysteines are within or flanking this region, Park and Sodroski suggested that intramolecular disulfide bonds may be important for packaging due to their effects on the conformation of Vpx. In contrast, the domain of Vpr that is critical for virion incorporation has been mapped to the α-helical region (2).

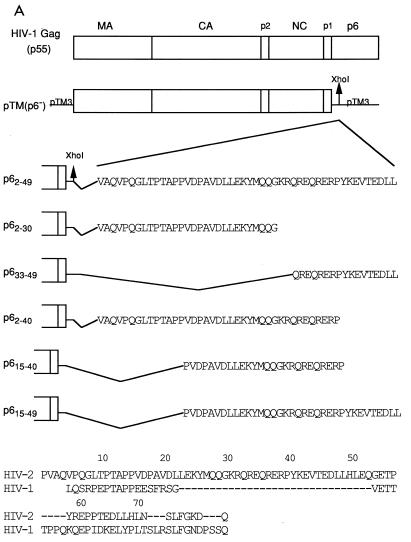

FIG. 1.

Residues 73 to 89 of HIV-2 Vpx are required for particle incorporation. (A) Schematic drawing of wild-type and mutant Vpx constructs cloned into the pTM3 vector. At the top is a diagram of HIV-2 Vpx, with the region predicted to form an amphipathic helix (shaded box), the conserved cysteines (asterisks), and the proline-rich tail (striped box) denoted. a.a., amino acids. Metabolically labeled proteins from BSC40 cell lysates (B) were immunoprecipitated with antisera to Vpx, and cell supernatants (C) were immunoprecipitated with antisera to Vpx and Gag before SDS-PAGE. The locations of the Gag and the Vpx proteins are indicated. M.W., molecular mass.

In addition to Vpx, the region within Gag required for Vpx packaging has been examined. It has previously been shown that residues 439 to 497 of HIV-2 Gag are required for the packaging of Vpx (25). This region consists of the seven C-terminal residues of p1 and the 51 N-terminal residues of p6 (Fig. 2). Similarly, the p6 protein is necessary and sufficient for the incorporation of Vpr into virions, and the region required has been mapped to residues 35 to 47 of HIV-1 p6 (12, 14, 19).

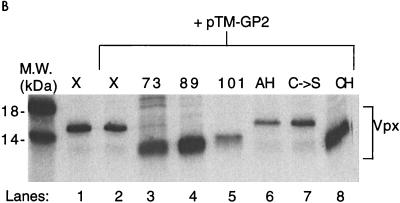

FIG. 2.

Sucrose gradient analysis of virus-like particles. The particles were concentrated by sedimentation through a 20% sucrose cushion at 26,000 rpm for 90 min in an SW28.1 rotor. Particles were resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline, layered onto linear 20 to 60% sucrose gradients, and centrifuged at 20,000 rpm for 16 h. A 20-μl aliquot of each fraction was loaded directly onto an SDS–15% PAGE gel. Fraction 1 is from the top of each gradient, and fraction 11 is from the bottom of each gradient. Protein molecular mass markers are shown in the first lane of each autoradiogram.

In the present study, we have further mapped the domains within HIV-2 Vpx and p6 required for Vpx incorporation. In addition, we have demonstrated an interaction between Vpx and p6 in vitro, supporting the hypothesis that a protein-protein interaction between Vpx and Gag may be responsible for the recruitment of Vpx into virus particles.

Identification of Vpx packaging determinants.

To examine packaging events, we used a vaccinia virus expression system that reproduces characteristics of HIV assembly (15, 23). For this purpose, we used constructs which consist of the vpx (pTM-X) and gag-pol (pTM-GP2) genes of HIV-2 cloned into pTM3 (8). In order to define important domains within Vpx, six mutant constructs were also cloned into pTM3 (Fig. 1A). These were generated by PCR of HIV-2 ROD Vpx with a 5′ primer containing an NcoI site and a 3′ primer containing a SacI site. For the pTM-XAH construct, a 5′ primer containing a StuI site and a 3′ primer containing a SacI site were used to amplify residues 40 to 112. This PCR product was then ligated to pTM-X digested with StuI and SacI, which removes Vpx residues 20 to 112. For pTM-XC→S, site-directed mutagenesis was used to change the cysteine codons at positions 73, 87, and 89 to serine codons (13). These plasmids were designed to express Vpx proteins with deletions of the amphipathic helix (pTM-XAH), the cysteine-rich domain (pTM-XCH and pTM-X73), or the proline-rich carboxyl terminus (pTM-X101, pTM-X89, and pTM-X73). Plasmids pTM-X89, pTM-X73, and pTM-XCH also have a deletion of the intervening region between the cysteine-rich region and the proline-rich terminus. Plasmid pTM-XC→S is a mutant which tests the potential role of disulfide bonds in Vpx particle incorporation. Each of the clones was confirmed by sequence analysis (20).

The pTM3 vector contains a T7 polymerase promoter. BSC40 cells which were 90% confluent on 100-mm-diameter tissue culture plates were maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum, 1 mM pyruvate, 100 U of penicillin per ml, and 100 μg of streptomycin per ml. Cells were infected for 1 h at 37°C with a recombinant vaccinia virus expressing T7 polymerase (vTF7-3) at a multiplicity of infection of 10. They were then transfected with 10 μg of each pTM3 construct in the presence of 10 μl of Lipofectin (GIBCO). Four hours after transfection, the cells were labeled with cysteine and methionine-free Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium containing 50 μCi of Tran35S-label per ml. After 20 h, the conditioned medium was clarified by centrifugation at 1,000 rpm for 5 min and lysed by the addition of 10× lysis buffer (100 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 1.5 M NaCl, 10% Triton X-100, 10 mM EDTA). The cells were washed with phosphate-buffered saline, scraped off the plates, pelleted by centrifugation, and then lysed by the addition of 1× lysis buffer. Nuclei were removed by centrifugation at 2,000 rpm for 10 min. Cell lysates were analyzed by immunoprecipitation with polyclonal Vpx antibody diluted 1:500 (8) to determine the levels of Vpx expression (Fig. 1B). The antibody was able to detect each of the mutants, and no dimeric or oligomeric forms of Vpx were observed in these immunoprecipitations (data not shown). Vpx and Gag in virus-like particles were then detected by immunoprecipitation of the conditioned medium with pooled polyclonal Vpx and Gag antisera (Fig. 1C). The 35S-labeled proteins were analyzed by electrophoresis on a sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)–15% polyacrylamide gel, followed by autoradiography. The ratio of Vpx to capsid (CA) molecules was determined by scanning densitometric analysis of the two bands, followed by a correction for the relative amounts of cysteine and methionine.

The amount of Vpx observed in the lysates varied among the mutants, similar to what has been observed by others (18). Greater than wild-type protein levels of pTM-X73, pTM-X89, and pTM-XCH are shown in the present study (Fig. 1B, lanes 3, 4, and 8). The increased level of pTM-X89 detected in the lysate was not consistent within this experiment (data not shown). Results obtained with [3H]leucine were similar to those obtained with Tran35S-label (data not shown), suggesting that the deletion of cysteine and methionine residues in some of the mutants is not responsible for the differences in the levels of detection of different Vpx proteins. Comparison of the amount of Vpx in cell lysates to the amount in virus-like particles indicated a reduction in the packaging ability of mutants pTM-X73 and pTM-XCH (Fig. 1C, lanes 3 and 8). The Vpx/Gag ratio in these mutants is 0 compared to 1.5 for wild-type Vpx. In contrast, pTM-X89 is packaged nearly as efficiently as wild-type Vpx (lane 4), with a Vpx/Gag ratio of 1.1, suggesting that Vpx residues 73 to 89 are critical for incorporation into virus-like particles. Even though this region contains the conserved cysteine residues previously mentioned, these residues do not appear to be important for packaging, since the pTM-XC→S protein was also packaged into virus-like particles with wild-type efficiency (lane 7; Vpx/Gag ratio of 1.2). Additionally, neither the C-terminal stretch of prolines nor the amphipathic helix appeared to function in packaging, as both pTM-X101 and pTM-XAH are incorporated into the virus-like particles with Vpx/Gag ratios of 1.2 and 1.3, respectively (lanes 5 and 6). When the conditioned medium from cells transfected with pTM-GP2 and either pTM-X, pTM-X73, or pTM-X89 was centrifuged through a 20 to 60% equilibrium density sucrose gradient and analyzed directly by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) without immunoprecipitation, only wild-type Vpx and X89 were found at the peak of the gradient (fractions 6 to 8; sucrose density, 1.14 to 1.18 g/ml) along with CA (Fig. 2). In contrast, little or no X73 was found with CA in the peak gradient fractions when coexpressed with pTM-GP2. These findings suggest that the results from the immunoprecipitations accurately represent the constituents of virus-like particles.

Identification of p6 packaging determinants.

It has previously been shown with the vaccinia virus system (8) that HIV-1 Gag is not capable of incorporating Vpx into virus-like particles. Therefore, to study functional domains within HIV-2 p6, we utilized a truncated HIV-1 Gag missing the entire p6 sequence and attached to this polyprotein various portions of HIV-2 p6 in order to generate chimeras and determine if they were able to restore the packaging ability of Vpx (Fig. 3A). These chimeras included almost the entire HIV-2 Gag sequence shown to be sufficient for Vpx incorporation into particles (p62–49) (25) or portions of this sequence (p62–30 and p633–49). Subscripts indicate HIV-2 p6 residues present in each chimeric Gag protein. Additional plasmids were constructed to examine the possibility that a determinant common to p62–30 and p633–49 could be involved in Vpx incorporation into virus-like particles. These included p62–40, p615–40, and p615–49. The HIV-1 pTM(p6−) construct has been described previously (14). This construct has a unique XhoI site four residues downstream from the p1 spacer peptide. This site was used for the insertion of the six different HIV-2 p6 PCR products. In addition, as a positive control, we used a construct, pTM-p6(2), which we had previously shown was able to package Vpx. This construct consists of a BglII/EcoRI fragment from HIV-2 Gag ligated into BglII/EcoRI-digested HIV-1 Gag in the pTM1 backbone. This construct has eight residues of the HIV-2 p1 spacer plus all of p6 connected in frame to a p6− HIV-1 Gag. All of the constructs were sequenced to verify that they were correct.

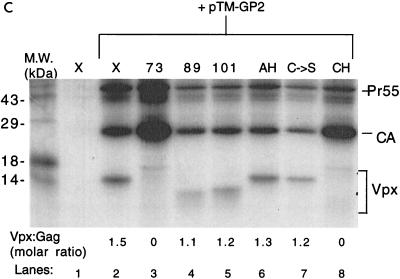

FIG. 3.

Residues 15 to 40 of HIV-2 p6 are necessary for Vpx virion incorporation. (A) Schematic drawing of the chimeric Gag constructs. Sequences of HIV-2 p6 (indicated numerically) were cloned in frame into the XhoI site of pTM(p6−). At the bottom is an alignment of HIV-2 and HIV-1 p6 sequences. (B) Cell lysates of BSC40 cells cotransfected with pTM-X and the Gag chimeric constructs were immunoprecipitated with αVpx and αGag antisera. (C) Cell supernatants from the same experiment. The locations of the Gag proteins and Vpx are indicated. M.W., molecular mass.

Cotransfection of these constructs and pTM-X into BSC40 cells, as described for Fig. 1, resulted in similar levels of both Vpx and Gag in the cell lysates (Fig. 3B). When Vpx was coexpressed with pTM(p6−), no export of Vpx into the conditioned medium could be detected (Fig. 3C, lane 1). Coexpression of pTM-p6(2) with Vpx allowed for the packaging of Vpx into virus-like particles (lane 2; Vpx/Gag ratio of 1.7), as did p62–49 (lane 5; Vpx/Gag ratio of 1.7). This latter result rules out possible involvement of the p1 peptide in Vpx packaging.

Coexpression of Vpx and p633–49 did not result in virion incorporation (lane 4; Vpx/Gag ratio, <0.1), and p62–30 packaged only a small amount of Vpx (lane 3; Vpx/Gag ratio, 0.4), suggesting that a critical domain had been disrupted in these constructs. In support of this finding, p62–40, p615–40, and p615–49 were all able to package Vpx in amounts comparable to both p6(2) and p62–49 (lanes 6, 7, and 8; Vpx/Gag ratios of 1.5, 1.5, and 1.7, respectively). This result suggests that the region within HIV-2 p6 required for Vpx packaging is contained between residues 15 and 40. There is a conserved region stretching from amino acids 23 to 52 in p6 of HIV-2 and SIVs but not in HIV-1 p6 (Fig. 3A, bottom) (17). Since these are the viruses which contain Vpx, this region is an attractive candidate for the Vpx packaging signal. Our data implicate the N-terminal 17 residues of this unique region, amino acids 23 to 40 of p6, although they cannot rule out an additional contribution provided by surrounding sequences.

In vitro binding of Vpx to p6 sequences.

We wanted to determine if residues 2 to 49 of HIV-2 p6 are necessary and sufficient for binding to Vpx in vitro. To do this, we utilized a glutathione S-transferase (GST) fusion protein binding assay. We had previously demonstrated that a GST fusion protein containing the complete HIV-2 Pr55gag precursor is able to bind Vpx, whereas a GST fusion protein with only HIV-2 p6 is unable to bind Vpx (data not shown). Since we were unable to determine whether the p6 portion of the latter fusion protein was stable or whether it had adopted its wild-type conformation, we used HIV-1 Gag and HIV-1/HIV-2 chimeric fusion proteins in the following assays. pTM-p62–49 and pTM(p6−) were digested with NcoI and StuI, and the NcoI site was filled in with Klenow. The constructs were then cloned into the SmaI site of pGEX-2T and expressed as fusion proteins with GST to allow easy purification of the fusion proteins on glutathione-Sepharose beads (22).

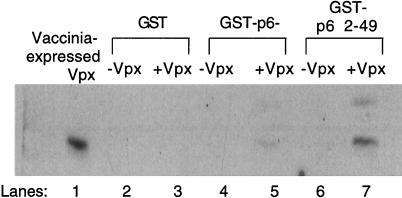

As a source of binding material, cell lysate from a 100-mm-diameter dish of BSC40 cells transfected with pTM-X was harvested as previously described. This lysate was precleared with 40 μl of glutathione beads and then added to either GST alone, GST-p6−, or GST-p62–49. The samples were rotated overnight at 4°C in the presence of 40 μl of glutathione beads and then washed three times with 1× lysis buffer. Proteins were eluted off the beads by the addition of 2× sample buffer and heated to 95°C for 5 min. They were then electrophoresed on an SDS–12% polyacrylamide gel, and the binding of Vpx was assayed by Western blotting with αVpx antiserum followed by a peroxidase-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit antibody. Bound secondary antibody was detected by treating the filter with Amersham enhanced chemiluminescent reagents. Using this approach, we were able to detect binding of Vpx to chimeric HIV-1/HIV-2 Gag sequences (Fig. 4). Vpx interacts with GST-p62–49 (lane 7), whereas it does not bind to GST alone (lane 3). There is a low level of Vpx binding to the GST-p6− construct (lane 5), but it is significantly less than that binding to GST-p62–49, even though equivalent levels of fusion proteins were used in these assays as determined by Coomassie staining (data not shown).

FIG. 4.

Residues 2 to 49 of HIV-2 p6 are able to enhance Vpx binding in vitro. GST and the GST-p6− and GST-p62–49 fusion proteins were incubated with vaccinia virus-expressed Vpx and glutathione beads. Proteins eluted off the beads were detected by Western blotting with Vpx antisera.

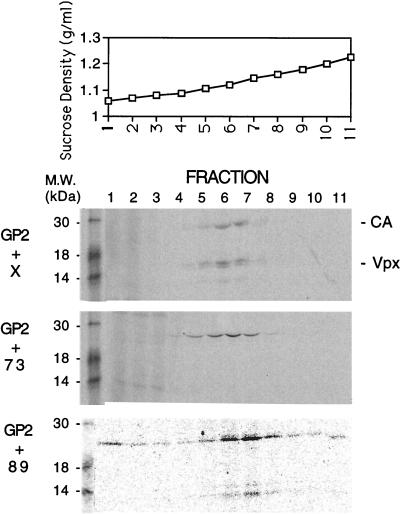

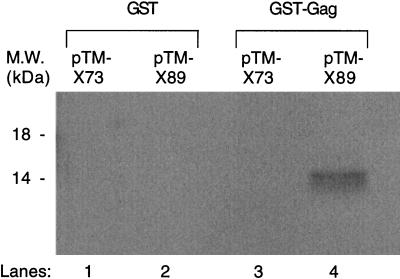

Residues 73 to 89 of Vpx are required for in vitro binding to Gag.

Since residues 73 to 89 of HIV-2 Vpx appear to be important for incorporation into virus-like particles, we wanted to determine if they were necessary for in vitro interaction between Vpx and Gag. Coupled in vitro transcription and translation of Vpx73 and Vpx89 truncation proteins were performed with pTM-X73 and pTM-X89 as templates in the Promega T7 TnT system. Translations were done in the presence of Tran35S-label at a final concentration of 0.4 mCi/ml. These labeled proteins were then used in a binding assay with a GST-Gag fusion protein. This protein was generated from a clone made by digesting pTM-GP2 with NcoI and EcoRI, followed by Klenow-mediated fill-in of both sites and ligation of the cDNA into the SmaI site of pGEX-2T. Bound proteins were detected by electrophoresis on an SDS–15% PAGE gel, followed by autoradiography. With similar levels of Vpx73 and Vpx89, significant levels of binding to GST-Gag are observed only with Vpx89 (Fig. 5). In combination with the previous data obtained by the vaccinia virus expression system, the results from this binding assay suggest that residues 73 to 89 of HIV-2 Vpx are involved in a protein-protein interaction with HIV-2 Gag, which then allows for incorporation into virus-like particles.

FIG. 5.

The presence of Vpx residues 73 to 89 allows for in vitro binding of Vpx to GST-Gag. GST and GST-Gag proteins were incubated with 35S-labeled Vpx73 or Vpx89 proteins. M.W., molecular mass.

Our results define specific Vpx packaging components in both HIV-2 Vpx and p6. This region defined within Vpx is similar to what has been defined in SIV Vpx; however, involvement of the cysteine residues in packaging events has been excluded. The p6 region required for Vpx packaging has been more narrowly defined to residues 15 to 40, which contains a unique region not found in HIV-1. The p6 region identified here as being important for Vpx virion incorporation differs from that found for HIV-1 Vpr incorporation (14). The latter has been demonstrated to require residues 35 to 47 of HIV-1 p6, and specifically, a (leucine-X-X)4 motif (where X is any amino acid) appears to be important for packaging. No such motif exists within residues 15 to 40 of HIV-2 p6, suggesting that these two accessory proteins utilize different components within p6 for their incorporation into the virion. This possibility is supported by the finding of KewalRamani and Emerman that HIV-2 Vpx does not compete with Vpr for particle incorporation in vivo (11).

Residues within both HIV-2 p6 and Vpx demonstrated to be important for Vpx packaging by the vaccinia virus system were also shown to enhance Vpx binding in a GST capture assay. This result suggests that after translation, Vpx binds to Pr55gag in a manner that requires residues 15 to 40 of p6 and 73 to 89 of Vpx. Additional studies will be required to address more specifically the characteristics of these sequences which are required for protein-protein interactions and virion incorporation.

Acknowledgments

We thank Robert Horton for technical help, Rebekah Villoria for generating a number of the Vpx deletion constructs, and Yuh-Ling Lu for the use of the pTM-(p6−) construct.

This work was supported by PHS grants A136071 and A134736 and by training grant A107172-16.

REFERENCES

- 1.Chakrabarti L, Guyader M, Alizon M, Daniel D, Desrosiers R C, Tiollais P, Sonigo P. Sequence of simian immunodeficiency virus from macaque and its relationship to other human and simian retroviruses. Nature. 1987;328:543–547. doi: 10.1038/328543a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.DiMarzio P, Choe S, Ebright M, Knoblauch R, Landau N R. Mutational analysis of cell cycle arrest, nuclear localization and virion packaging of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 vpr. J Virol. 1995;69:7909–7916. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.12.7909-7916.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fletcher T M, Brichacek B, Sharova N, Newman M A, Stivahtis G, Sharp P M, Emerman M, Hahn B H, Stevenson M. Nuclear import and cell cycle arrest functions of the HIV-1 Vpr protein are encoded by two separate genes in HIV-2/SIV(SM) EMBO J. 1996;15:6155–6165. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Franchini G, Rusche J R, O’Keeffe T J, Wong-Staal F. The human immunodeficiency virus type 2 (HIV-2) contains a novel gene encoding a 16 kD protein associated with mature virions. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 1988;4:243–250. doi: 10.1089/aid.1988.4.243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guyader M, Emerman M, Montagnier L, Peden K. Vpx mutants of HIV-2 are infectious in established cell lines but display a severe defect in peripheral blood lymphocytes. EMBO J. 1989;8:1169–1175. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1989.tb03488.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guyader M, Emerman M, Sonigo P, Clavel F, Montagnier L, Alizon M. Genome organization and transactivation of the human immunodeficiency virus type 2. Nature. 1987;326:662–669. doi: 10.1038/326662a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Henderson L E, Sowder R C, Copeland T D, Benveniste R E, Oroszlan S. Isolation and characterization of a novel protein (X-ORF product) from SIV and HIV-2. Science. 1988;241:199–201. doi: 10.1126/science.3388031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Horton R, Spearman P, Ratner L. HIV-2 viral protein X association with the Gag p27 capsid protein. Virology. 1994;199:453–457. doi: 10.1006/viro.1994.1144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kappes J C, Conway J A, Lee S W, Shaw G M, Hahn B H. Human immunodeficiency virus type 2 vpx protein augments viral infectivity. Virology. 1991;184:197–209. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(91)90836-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kappes J C, Parkin J S, Conway J A, Kim J, Brouillette C G, Shaw G M, Hahn B H. Intracellular transport and virion incorporation of vpx requires interaction with other virus type-specific components. Virology. 1993;193:222–233. doi: 10.1006/viro.1993.1118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.KewalRamani V N, Emerman M. Vpx association with mature core structures of HIV-2. Virology. 1996;218:159–168. doi: 10.1006/viro.1996.0176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kondo E, Mammano F, Cohen E A, Gottlinger H G. The p6gag domain of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 is sufficient for the incorporation of Vpr into heterologous viral particles. J Virol. 1995;69:2759–2764. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.5.2759-2764.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kunkel T A. Rapid and efficient site-specific mutagenesis without phenotypic selection. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1985;82:488–492. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.2.488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lu Y-L, Bennett R P, Wills J W, Gorelick R, Ratner L. A leucine triplet repeat sequence (LXX)4 in p6gag is important for Vpr incorporation into human immunodeficiency virus type 1 particles. J Virol. 1995;69:6873–6789. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.11.6873-6879.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lu Y L, Spearman P, Ratner L. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 viral protein R localization in infected cells and virions. J Virol. 1993;67:6542–6550. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.11.6542-6550.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marcon L, Michaels F, Hattori N, Fargnoli K, Gallo R C, Franchini G. Dispensable role of the human immunodeficiency virus type 2 Vpx protein in viral replication. J Virol. 1991;65:3938–3942. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.7.3938-3942.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Myers G, Korber B, Wain-Hobson S, Jeang K T, Henderson L E, Pavlakis G N. Human retroviruses and AIDS. Theoretical Biology and Biophysics Group T-10. Los Alamos, N.Mex: Los Alamos National Laboratory; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Park I, Sodroski J. Amino acid sequence requirements for the incorporation of the vpx protein of simian immunodeficiency virus into virion particles. J Acquired Immune Defic Syndr Hum Retrovirol. 1995;10:506–510. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Paxton W, Connor R I, Landau N R. Incorporation of Vpr into human immunodeficiency virus type 1 virions: requirement for the p6 region of gag and mutational analysis. J Virol. 1993;67:7229–7237. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.12.7229-7237.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sanger F, Nicklen S, Coulson A R. DNA sequencing with chain-terminating inhibitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1977;74:5463–5467. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.12.5463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sharp P M, Bailes E, Stevenson M, Emerman M, Hahn B H. Gene acquisition in HIV and SIV. Nature. 1996;383:586–587. doi: 10.1038/383586a0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Smith D B, Johnson K S. Single-step purification of polypeptides expressed in Escherichia coli as fusions with glutathione-S-transferase. Gene. 1988;67:31–40. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(88)90005-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Spearman P, Wang J-J, Vander Heyden N, Ratner L. Identification of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Gag protein domains essential to membrane binding and particle assembly. J Virol. 1994;68:3232–3242. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.5.3232-3242.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tristem M, Marshall C, Karpas A, Hill F. Evolution of the primate lentiviruses: evidence from vpx and vpr. EMBO J. 1992;11:3405–3412. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05419.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wu X, Conway J A, Kim J, Kappes J C. Localization of the vpx packaging signal within the C terminus of the human immunodeficiency virus type 2 gag precursor protein. J Virol. 1994;68:6161–6169. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.10.6161-6169.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]