Abstract

Adeno-associated virus (AAV) is a human parvovirus of the genus Dependovirus. AAV replication is largely restricted to cells which are coinfected with a helper virus. In the absence of a helper virus, the AAV genome can integrate into a specific chromosomal site where it remains latent until reactivated by superinfection of the host cell with an appropriate helper virus. Replication functions of AAV have been mapped to the Rep68 and Rep78 gene products. Rep proteins demonstrate DNA binding, endonuclease, and helicase activities and are involved in regulation of transcription from both AAV and heterologous promoters. AAV has been associated with suppression of oncogenicity in a range of viral and nonviral tumors. In this study we sought to identify and study cellular protein targets of AAV Rep, in order to develop a better understanding of the various activities of Rep. We used the yeast two-hybrid system to identify HeLa cell proteins that interact with AAV type 2 Rep78. We isolated several strongly interacting clones which were subsequently identified as PRKX (previously named PKX1), a recently described homolog of the protein kinase A (PKA) catalytic subunit (PKAc). The interaction was confirmed in vitro by using pMal-Rep pull-down assays. The region of Rep78 which interacts was mapped to a C-terminal zinc finger-like domain; Rep68, which lacks this domain, did not interact with PRKX. PRKX demonstrated autophosphorylation and kinase activity towards histone H1 and a PKA oligopeptide target. Autophosphorylation was inhibited by interaction with Rep78. In transfection assays, a PRKX expression vector was shown to be capable of activating CREB-dependent transcription. This activation was suppressed by Rep78 but not by Rep68. Since PRKX is a close homolog of PKAc, we investigated whether Rep78 could interact directly with PKAc. pMal-Rep78 was found to associate with purified PKAc and inhibited its kinase activity. Cotransfection experiments demonstrated that Rep78 could block the activation of CREB by a PKAc expression vector. These experiments suggest that AAV may perturb normal cyclic AMP response pathways in infected cells.

Adeno-associated virus (AAV) is a human parvovirus that, for its replication, usually requires that its host cell is coinfected with a helper virus, usually an adenovirus or herpesvirus. Infection with AAV in the absence of a helper virus can result in integration of the viral genome into a specific site on chromosome 19. The provirus then enters a latent state until it is reactivated by superinfection of the host cell with a helper virus or by genotoxic stress (for a review, see reference 5). AAV appears to be nonpathogenic in humans; in fact, seropositivity to AAV has been shown epidemiologically to be a protective factor against the development of carcinoma of the uterine cervix (14, 36). Recent data suggest that the cervical neoplasia-associated human papillomaviruses may act as helper viruses for AAV in vivo (53).

The AAV type 2 (AAV2) genome comprises a single-stranded DNA molecule of approximately 4.7 kb which can be divided into early (Rep) and late (Cap) regions (49a). The genome is bounded by inverted terminal repeats (ITRs) which provide the viral origins of replication. The Rep region encodes four related proteins through usage of two promoters and differential splicing. The p5 promoter drives the expression of Rep78 and Rep68, which differ at their C termini due to differential splicing. An internal promoter, p19, directs the synthesis of Rep52 and Rep40, which correspond to the C-terminal regions of Rep78 and Rep68, respectively. The Rep68/78 proteins are essential for the replication of AAV and possess ATP-dependent DNA helicase, site-specific endonuclease, and viral origin of replication binding activities (2, 23, 38, 58). Rep68/78 proteins also bind to the chromosome 19 integration sites and mediate the integration of AAV into the chromosome (27, 35, 57). The Rep40/52 proteins do not bind DNA directly but appear to be required for the accumulation and encapsidation of single-stranded genomes.

Rep proteins also have roles in regulating AAV gene expression. In addition to binding the viral ITRs, a Rep68/78-specific binding site occurs in the p5 promoter (37). In the absence of a helper virus infection, Rep synthesis is tightly repressed; however, in the presence of a helper, both Rep and Cap gene expression is induced. This switch appears to be integrated through the activities of the Rep proteins (32). In the absence of a helper virus, Rep68/78 binding to the p5 promoter site may inhibit transcription by physical occlusion of promoter elements (30). Rep can also inhibit transcription from the p19 promoter in the absence of direct binding to promoter-proximal elements, in a manner that requires an intact Rep nucleotide binding site (22, 29). This suggests that Rep suppression of the p19 promoter is probably mediated through protein-protein interactions. During productive infection, Rep acts as a powerful transactivator of the p19 and p40 promoters, and displacement of Rep68/78 from the p5 promoter binding site may act to derepress this promoter (30, 32, 45). Rep40/52 proteins may act to derepress the p5 promoter by entering into complexes with the larger Rep proteins, reducing their DNA binding activities (45). Rep78, -68, and -52 proteins have the capacity to down regulate gene expression from a variety of heterologous promoters, most of which do not contain sequence homologies with the p5 and ITR Rep binding sites (18, 19, 22, 31, 42, 48). It appears that DNA binding of Rep to specific sites is unlikely to account for transcriptional repression in such cases, and this again suggests that Rep proteins can mediate transcriptional silencer effects via protein-protein interactions.

AAV has also been shown to inhibit oncogenic transformation in vitro, and in many cases this property has been mapped to the Rep proteins. Cotransfection of Rep78-expressing plasmids inhibited transformation by adenovirus E1a+ras, simian virus 40, bovine papillomavirus, and human papillomavirus (17, 19, 25). AAV DNA, when integrated into HeLa cells, resulted in decreased growth, increased anchorage dependence, and enhanced sensitivity to growth factor withdrawal, tumor necrosis factor alpha, or genotoxic agents (51, 52). There is evidence for AAV-induced cell cycle blocks at both the G1 and G2 phases of the cell cycle (3, 62). Cells arrested by AAV contain hypophosphorylated Rb and express elevated levels of p21/waf-1/cip-1 protein, which is induced in a p53-independent manner. It is not yet clear whether the up regulation of p21 is a function of the Rep proteins (16). The molecular mechanisms and cellular targets of oncosuppression by AAV are not well understood.

The helper virus functions which are required for AAV replication have been identified for adenovirus and herpes simplex virus (HSV) type 2. The adenovirus E1a, E1b, E2a, E4, and VA genes are sufficient for helper virus function (60). For HSV type 1 the ICP4 transactivator, DNA polymerase, ICP8, origin binding protein, and helicase-primase complex have been implicated (40, 56). During its replication cycle, AAV can inhibit production of its helper virus (4, 8, 9). The mechanisms underlying interference with helper virus replication have not been determined. One report indicated that posttranscriptional down regulation of adenovirus E1b may be involved (43).

The various activities of AAV Rep are likely mediated in part through contacts between the Rep proteins and host cell proteins. It has been shown previously that Rep can interact with itself to form higher-order structures, probably hexamers (20, 49). Recently it has been shown that Rep can bind to the transcription factor Sp1, and this may in part account for its ability to regulate transcription of AAV and heterologous promoters (21, 45). Rep has also been found to associate with the high-mobility group 1 protein, an interaction which enhances the DNA binding, helicase, and endonuclease activities of Rep (11).

In this paper we describe the use of the yeast two-hybrid system to identify cellular proteins that interact with AAV2 Rep78. We found that Rep78 but not Rep68 interacts with PRKX, a recently described homolog of the cyclic AMP (cAMP)-dependent protein kinase A (PKA) catalytic subunit (PKAc). Subsequently, we found that Rep78 also interacts with PKAc itself. Interaction with Rep78 was found to inhibit the kinase activities of both PRKX and PKAc. Rep78, but not Rep68, was able to block the induction of CREB-dependent transcription in HeLa cells. These observations suggest that AAV may utilize Rep to subvert cAMP-dependent regulatory pathways in infected cells. The inhibition of these pathways may influence the balance between AAV and helper virus replication.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Construction of plasmid vectors.

A maltose binding protein (MBP) fusion construct containing AAV2 Rep68 (pMALcRep68) and a clone containing the entire genome of AAV2 (pAV2) were gifts from Ken Berns. pGBT9-Rep68 was constructed by cloning the Rep68 open reading frame (ORF) from pMALcRep68 into pGBT9 (Clontech) by using the EcoRI and XhoI sites present in both vectors. pGBT9-Rep78 was generated by subcloning an AatII-XhoI fragment comprising nucleotides (nt) 1868 to 2233 of AAV2 (numbering is as for the sequence under GenBank accession no. J01901) from pAV2 into AatII-XhoI-digested pGBT9-Rep68. pGBT9-Rep78-Cterm was generated by eliminating an EcoRI fragment (nt 321 to 1767) from pGBT9-Rep78.

In order to produce an MBP fusion construct expressing Rep78, the AatII-XhoI fragment from pAV2 (see above) was cloned into similarly digested pMALcRep68, resulting in pMALcRep78. The Rep78 C-terminal region was cloned as a glutathione S-transferase (GST) fusion by PCR amplification of AAV2 nt 1768 to 2252 and subcloning as a BamHI fragment into pGEX-4T-1 (Pharmacia) to produce pGST-Cterm.

Vectors which express exclusively Rep68 or Rep78 under the control of the cytomegalovirus (CMV) promoter were gifts of J. Kleinschmidt (pKex68 and pKex78) (22). p78-myc/his was obtained by cloning the XhoI-HindIII insert from pKex78 into pcDNA3.1 (Invitrogen) in such a way that Myc and His peptide tags were added to the C terminus. A similar protocol was used to subclone Rep68 from pKex68 into pcDNA3.1, producing p68-myc/his. In p78-myc/his and p68-myc/his, the Rep genes are under the control of both the CMV and T7 promoters.

pCITE-PRKX was obtained by cloning the EcoRI fragment from pGAD-PRKX (encoding amino acids 29 to 358) into pCITE4b (Novagen). This resulted in the attachment of an S tag to the N terminus of the PRKX protein produced by this vector, under the control of the T7 promoter. The insert from pCITE-PRKX, including the S tag, was also cloned into pCI (Promega) to produce pCIS-PRKX and place the ORF under the control of the CMV promoter. A full-length clone of PRKX (FB166, containing nt 309 to 1640) was a gift from G. A. Rappold (26). The insert from this plasmid was cloned as a SmaI-EcoRI fragment into EcoRV-EcoRI-digested pcDNA3.1 (Invitrogen) to produce pcDNA-PRKX, in which the ORF was under the control of the CMV promoter and contained the endogenous PRKX AUG codon context.

Yeast two-hybrid system control vectors pGBT-p130, pGBT-p107, and pGAD-HPV16-E7 were gifts of Massimo Tommasino. The expression vectors pFR-Luc, pFA-CREB, and pFC-PKA were obtained commercially (Stratagene).

Yeast two-hybrid system library screening.

Two-hybrid screening was done in Saccharomyces cerevisiae by using the Clontech Matchmaker system. Briefly, strain HF7c was transformed with pGBT9-Rep78, and the resulting clone was retransformed with a previously amplified HeLa cell cDNA library in the vector pGAD-GH (Clontech). Transformant yeast cells were selected on Trp-Leu-His dropout medium containing 20 mM 3-aminotriazole (3-AT). Approximately 400 colonies were obtained from a screening of approximately 106 independent clones. All 400 colonies were assayed for β-galactosidase activity by using a filter assay. Plasmid DNA from positive clones was rescued and used to transform Escherichia coli XL-1 Blue (Stratagene). Clones from the pGAD-GH library were selected, and the plasmids were retransformed into yeast strain SFY526 along with pGBT9-Rep78 or pGBT9. Resultant clones were assayed for β-galactosidase activity by using a quantitative solution-based ONPG (o-nitrophenyl-β-d-galactopyranoside) assay as described by the manufacturer (Clontech). Plasmids from clones which were positive in this assay were analyzed further by DNA sequencing.

pMal-Rep pull-down experiments.

MBP (New England Biolabs) and GST (Pharmacia) fusion proteins were expressed in E. coli BLR (Novagen), and proteins were purified according to the manufacturers’ instructions. However, for the production of GST-C-terminal protein, the incubation temperature after IPTG (isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside) induction was 30°C. Fusion proteins were immobilized on amylose- or glutathione-Sepharose beads as appropriate, and the protein concentrations were estimated by the Bradford protein assay (Pierce) and Coomassie blue staining of sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-polyacrylamide gels.

35S-labelled target proteins for pull-down reactions were produced by in vitro transcription-translation in rabbit reticulocyte lysates (RRL) (100-μl reaction mixtures; TnT system [Promega]). Beads containing 0.5 to 1.0 μg of each fusion protein were incubated at 4°C for 15 min with 20 μl of labelled target protein, made up to a total volume of 250 μl with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 1 mg of bovine serum albumin per ml and 0.1% Nonidet P-40. After extensive washing with PBS–bovine serum albumin–Nonidet P-40, bound radiolabelled protein was analyzed by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and visualized by PhosphorImager analysis (Molecular Dynamics). Gels were subsequently rehydrated, and the amounts of protein loaded were checked by Coomassie blue or silver staining. Input levels of radiolabelled target protein were estimated by running 10% of the input on separate polyacrylamide gels.

In the experiment shown in Fig. 3c, unlabelled, S-tagged PRKX was synthesized from pCITE-PRKX in RRL and then immobilized by incubation of 20 μl of lysate with 10 μl of S beads for 15 min at 4°C in a final volume of 250 μl in PBS. This was followed by five rinses in PBS. Successful immobilization of PRKX was confirmed by parallel experiments using radiolabelled protein and by silver staining. The S-bead-immobilized protein was then incubated with 20 μl of 35S-labelled target protein and analyzed as described above.

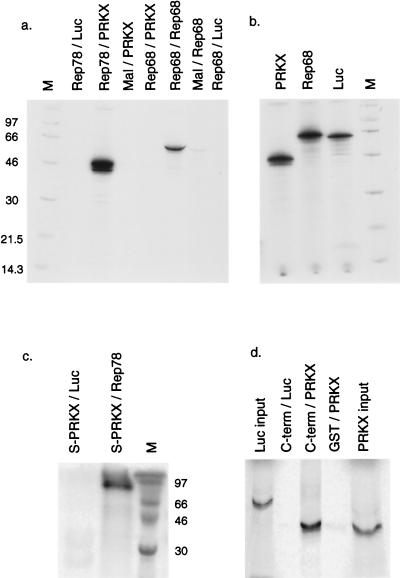

FIG. 3.

Rep78 interaction with PRKX in vitro. (a) MBP fusion proteins containing Rep78, Rep68, or Mal sequences alone were immobilized on amylose beads and then incubated with 35S-labelled PRKX, Rep68, or luciferase (Luc) protein synthesized in RRL. After washing, labeled protein which was associated with the MBP fusion protein was visualized by 12% PAGE and autoradiography. The lane markers indicate the MBP fusion/RRL protein combination. Lane M, molecular mass markers (in kilodaltons). (b) Input RRL proteins corresponding to 10% of the amount added to the pull-down reaction. (c) Unlabelled, S-tagged PRKX was synthesized in RRL and immobilized on S beads, followed by incubation with 35S-labelled, RRL-derived Rep78 or luciferase. Bound Rep78 was visualized by PAGE and autoradiography. (d) A GST fusion protein containing the C-terminal 139 amino acids of Rep78 was used in pull-down experiments with 35S-labelled, RRL-derived PRKX or luciferase. Input lanes contain 10% of the amounts added to the pull-down reactions.

PKA assays.

One hundred units of purified PKAc (Promega) was incubated with 0.5 to 1 μg of MBP or GST fusion proteins, immobilized on beads as described above, in a final volume of 50 μl in PBS at 4°C for 10 min, followed by extensive rinsing with PBS. Immobilized PKA activity was then determined by using a kemptide phosphorylation assay (PepTag; Promega) as follows. The beads were resuspended in 25 μl of kinase assay buffer containing kemptide substrate, followed by incubation for 30 min at room temperature. The reaction was terminated by boiling, and the products were examined by 0.8% agarose gel electrophoresis. For experiments on Rep inhibition of PKA activity, the amount of PKAc required to obtain approximately 50% phosphorylation of substrate peptide in a 10-min reaction was first determined empirically. The assay was then performed with this amount of PKAc held constant, while increasing amounts of amylose- or glutathione-eluted MBP, MBP-Rep, or GST and GST–C-terminal proteins were added to the reaction mixture. Phosphorylation of the kemptide substrate was then determined as described above.

Histone H1 kinase assay.

Unlabelled PRKX was immobilized on S beads as described above. Ten microliters of S beads was incubated at room temperature in kinase assay buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.4], 10 mM MgCl2) containing 20 nCi of [γ-32P]ATP, with or without 0.5 μg of histone H1, in a final volume of 30 μl. For autophosphorylation-inhibition assays, 0.3 or 0.6 μg of MBP or Rep-MBP fusion proteins was added prior to a 45-min incubation.

Cell culture and transfection.

HeLa cells were plated at 5 × 105/well on six-well plates 24 h prior to transfection. Cells were transfected with 30 μl of DOTAP (Boehringer Mannheim) per well with 1 μg of pFR-Luc, 1 μg of pFA-CREB, and 1 μg of pcDNA-PRKX, pCIS-PRKX, pFC-PKA, or pCI. Samples were additionally transfected with 2 μg of pKex68, pKex78, or pCI. Cells were harvested 48 h posttransfection and then lysed and assayed for protein content and luciferase activity. Results were expressed as normalized luciferase activity relative to that of the pFR-Luc/pCI/pCI control. The data presented were taken from a minimum of three independent experiments, each conducted in duplicate.

RESULTS

Identification of PRKX as a Rep78-interacting protein by using the yeast two-hybrid system.

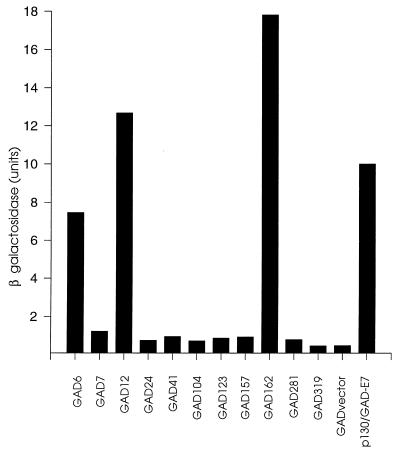

The Rep78 gene from AAV2 was cloned into the yeast shuttle vector pGBT to generate pGBT-Rep78, in which the Rep78 gene was fused to the Gal4 DNA binding domain. Transformation of pGBT-Rep78 into S. cerevisiae HF7c either alone or in combination with the Gal4 activation domain vector (pGAD424) resulted in growth on His dropout medium, indicating that Rep78 has an intrinsic transcriptional transactivation activity in this system. However supplementation of the medium with 20 mM 3-AT, an inhibitor of histidine biosynthesis, effectively suppressed the transactivation by Rep78 (data not shown), and this concentration of 3-AT was used subsequently for library screening. The vector pGBT-Rep78 was used as bait to screen a HeLa cell-derived cDNA library cloned in the vector pGAD-GH. Screening was initially done for growth on His dropout medium; this was followed by a β-galactosidase filter assay. Eleven clones that were positive in both assays were isolated. In order to conduct a quantitative assessment of the putative interactions, yeast strain SFY526, which contains the lacZ gene driven by a Gal4-responsive promoter, was transformed with pGBT-Rep78 or pGBT. Both of these clones were subsequently retransformed individually with the 11 pGAD clones isolated from the library. The resulting clones were assayed for β-galactosidase production by using a solution-based ONPG assay. For a positive control, a clone containing the pocket protein p130 fused to the DNA binding domain (pGBTp130) and the human papillomavirus E7 protein fused to the activation domain (pGAD-HPV16-E7) was used. As shown in Fig. 1, three of the clones (pGAD6, -12, and -162) in combination with pGBT-Rep78 produced β-galactosidase at levels approximately 10-fold higher than that of the negative control (pGBT-Rep78 plus pGAD424) and comparable to that of the positive control (pGBTp130 plus pGAD-HPV16-E7). Activity of these clones was dependent on the presence of Rep78 sequences fused to the DNA binding domain, since negligible β-galactosidase activity was observed when pGAD6, -12, or -162 was assayed in combination with the empty vector pGBT9 (not shown). We concluded that clones pGAD6, -12, and -162 encoded proteins which interacted specifically with Rep78.

FIG. 1.

Yeast two-hybrid assay for positively interacting clones. SFY526 yeast cells were transformed with pGBT-Rep78 and then retransformed individually with activation domain vectors pGAD6 to -319, which had previously scored positive in a LacZ filter assay. β-Galactosidase production was then measured by using a quantitative, solution-based ONPG assay. Control transformations were pGBT-Rep78 plus pGAD424 (GAD vector) and pGBTp130 plus pGAD-HPV16-E7 (p130/GAD-E7).

Analysis of these clones revealed that all three had identical inserts, identified as nt 449 to 2487 (amino acids 29 to 358) of PKX1 (now designated PRKX; EMBL accession no. X85545), a previously identified X-linked homolog of the cAMP-dependent protein kinase catalytic subunit PKAc (26). PRKX and PKAc show 75 to 76% homology and 49 to 55% identity between their catalytic domains. Accordingly, pGAD6 was redesignated pGAD-PRKX.

Rep68 does not interact with PRKX.

Rep68 is a spliced variant of Rep78 in which amino acids 530 to 621 are absent and are replaced with the sequence LARGHSL (Fig. 2a). Rep78 thus contains a unique C-terminal domain comprising six CXXH or CXXC motifs, which are typical of zinc finger domains found in a number of transcription factors. In order to investigate whether Rep68 could interact with PRKX, the Rep68 gene was first cloned into pGBT9 to produce pGBT-Rep68. This construct was transformed in combination with pGAD-PRKX, followed by determination of β-galactosidase production (Fig. 2b). The combination of Rep78 and PRKX produced high levels of β-galactosidase activity, as expected, while activity of the negative control Rep78 plus pGAD424 was low but detectable, consistent with the previously observed transactivation activity of Rep78. On the other hand, Rep68 showed no detectable β-galactosidase activity in combination with either pGAD-PRKX or the pGAD424 control vector. We concluded that Rep68 does not interact with PRKX in the yeast two-hybrid system. Moreover, this showed that Rep78, but not Rep68, displays intrinsic transactivation activity in this system. The positive control comprising pGBT-p107 and pGAD-HPV16-E7 showed rather low activity compared to the Rep78/PRKX and to the p130/HPV-16-E7 (Fig. 1) combinations. This may be due to poor expression or low tolerance for p107 in this system.

FIG. 2.

Yeast two-hybrid assay to localize the interaction domain between Rep78 and PRKX. (a) pGBT-Rep78 contains the full-length Rep78 ORF for amino acids 1 to 621. In pGBT-Rep68 the intron from amino acid 529 is spliced out and the sequence LARGHSL occurs at the splice acceptor site (light grey). An EcoRI fragment extending from the pGBT cloning site to AAV nt 1767 was deleted to produce pGBT-Cterm, which encodes Rep amino acids 483 to 621. (b) Strain SFY56 yeast cells were transformed with pGBT and pGAD vectors in the combinations indicated on the x axis. β-Galactosidase activity was then measured by ONPG assay. Error bars indicate standard deviations.

The C-terminal region of Rep78 interacts with PRKX.

Since the interaction between Rep and PRKX was restricted to Rep78, we examined whether the Rep78 C-terminal region alone was sufficient for interaction with PRKX. A pGBT vector encoding only the C-terminal 139 amino acids from Rep78 was produced (Fig. 2a), and the resulting clone, pGBT-Cterm, was assayed for β-galactosidase activity as described above. In combination with pGAD-PRKX, the Rep78 C-terminal clone showed β-galactosidase activity approaching that of the full-length Rep78 clone, indicating that the Rep78 C-terminal region interacted with PRKX (Fig. 2b). pGBT-Cterm in combination with the empty binding domain vector pGAD-424 also showed clearly detectable activity. This confirmed that the C-terminal region possesses intrinsic transcriptional transactivation abilities and suggests an involvement of the zinc binding domain in this phenomenon. The levels of β-galactosidase activity observed with the C-terminal domain constructs were consistently lower than those obtained with the full-length Rep78 clone (Fig. 2b and data not shown). While it is clear from these experiments that the C-terminal region of Rep78 is essential for the interaction with PRKX, regions outside the C-terminal region may contribute to the strength of the interaction.

Interaction between a pMal-Rep78 fusion protein and PRKX in vitro.

In order to determine whether Rep78 and PRKX interact directly in vitro, pull-down experiments were conducted. The Rep78- and Rep68-coding sequences were expressed as MBP fusions in E. coli, and the proteins were purified by immobilization on amylose beads. The PRKX fragment from pGAD-PRKX was cloned into the T7 promoter-driven vector pCITE4a, and the PRKX protein was expressed and metabolically labelled in RRL. The Rep68 and luciferase proteins were also metabolically labelled in RRL for use as controls (Fig. 3b). The labelled proteins were then used in pull-down reactions in combination with equalized amounts of the immobilized MBP fusions described above, and the amounts of labelled protein associated with the beads were determined by SDS-PAGE. As shown in Fig. 3a, MBP-Rep78 did not associate with labelled luciferase; however, a strong interaction was observed upon incubation with labelled PRKX, as evidenced by the appearance of a cluster of bands of approximately 43 to 46 kDa. Labelled PRKX did not interact with MBP alone. MBP-Rep68 was not able to associate with labelled PRKX, consistent with the previous observation with the yeast two-hybrid system. In order to ensure that the MBP-Rep68 was competent for protein-protein interaction, we incubated the MBP-Rep68 with RRL-labelled Rep68 generated from a T7-driven Rep68 expression vector (p68-myc/his). MBP-Rep68 was found to self-associate by using this method, confirming and extending a previous observation made for Rep78 (22, 49).

In order to confirm further the interaction between Rep78 and PRKX, an inverse pull-down experiment was conducted. The cloning of PRKX into the T7 expression vector pCITE4a resulted in the addition of an N-terminal peptide S tag to the molecule. Unlabelled, S-tagged PRKX was synthesized in RRL and then immobilized on S beads. In order to provide a source of Rep78, we cloned the gene into pcDNA3.1, which places Rep78 under the control of both the CMV and T7 promoters. The T7 promoter was used to produce labelled Rep78 in RRL. S-bead-immobilized PRKX was then incubated with labelled Rep78 or luciferase prepared in RRL. As shown in Fig. 3c, the immobilized PRKX interacted with Rep78 but not with luciferase. The high apparent molecular weight in SDS-PAGE associated with the pcDNA3.1-derived Rep78 is due to the addition of C-terminal Myc and His tags to the protein (see Materials and Methods).

The experiments shown in Fig. 2 showed that PRKX interacted with the C-terminal fragment of Rep78 comprising amino acids 483 to 621. Attempts to express this fragment as an MBP fusion protein were unsuccessful because the resulting protein was unstable in E. coli (not shown). However, a GST fusion protein containing the Rep78 C-terminal domain was found to be stable and could be purified on glutathione-Sepharose beads (not shown). Immobilized GST–C-terminal protein was used in pull-down experiments with labelled PRKX or luciferase produced in RRL. As shown in Fig. 3d, the GST–C-terminal fragment interacted with PRKX but not with luciferase. An equivalent amount of GST alone was unable to associate with labelled PRKX. Taken together, these data show that PRKX and Rep78 can physically interact in vitro and that this interaction relies upon the C-terminal region of Rep78.

PRKX demonstrates autophosphorylation and histone H1 kinase activity.

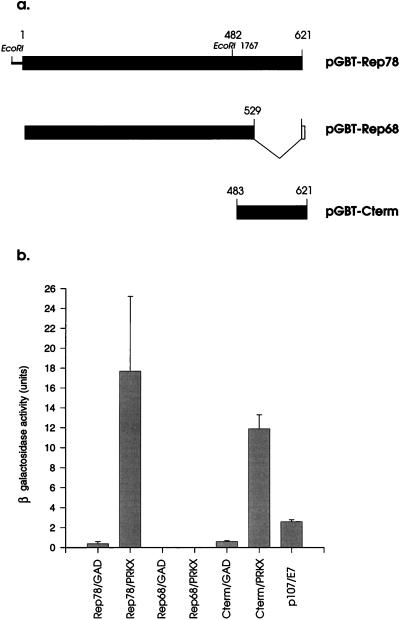

Although PRKX shows high degrees of homology to the kinase domain of mammalian PKAc subunits, kinase activity of PRKX has not been demonstrated previously. We sought to demonstrate a kinase activity for PRKX, initially with histone H1 as a substrate. Unlabelled, S-tagged PRKX was synthesized in RRL and immobilized on S beads. After washing, the protein was incubated in kinase buffer containing [γ-32P]ATP with or without histone H1. Surprisingly, when PRKX alone was incubated with kinase buffer without histone H1, a 32P-labelled band was visualized at approximately 46 kDa, corresponding to the size of PRKX itself (Fig. 4a, lane 2). Silver staining showed that the only detectable protein present was PRKX (not shown). These data suggested that PRKX was capable of autophosphorylation. In order to ensure that this activity was associated with PRKX and not a contaminant carried over from the RRL, S beads were incubated with RRL containing luciferase and then were washed and used in the kinase assay. No phosphorylated proteins were detected in this control (Fig. 4a, lane 1). Additional control experiments using a full-length, untagged PRKX clone confirmed that the N-terminal S tag carried on PRKX was not the substrate for autophosphorylation (not shown).

FIG. 4.

Kinase activity of PRKX protein in vitro. (a) S-tagged PRKX was synthesized in RRL and purified on S beads (S-bds) prior to addition to a 30-min kinase assay conducted in the presence (lane 3) or absence (lane 2) of histone H1 as a substrate. As a positive control, purified PKAc was used in the kinase assay with (lane 5) or without (lane 4) histone H1. As a negative control, S beads were incubated with luciferase (LUC)-programmed RRL and then added to the kinase assay (lane 1). 32P-labelled phosphorylated proteins were visualized by PAGE and autoradiography. Positions of phosphorylated PRKX and histone H1 are indicated. Lane M, molecular mass markers (in kilodaltons). (b) Same as in panel a except that incubation of the kinase reaction mixture was extended to 60 min. In this experiment histone H1 was added to the negative control reaction (lane 1). (c) S-bead-purified PRKX was incubated with the fluorescence-labelled PKA substrate kemptide (LRRASLG). Phosphorylated kemptide was separated from unphosphorylated substrate by agarose gel electrophoresis and visualized on a UV transilluminator. As a control, S beads preincubated with luciferase-programmed RRL were used in the kinase reaction. (d) S-bead-purified PRKX was autophosphorylated in a [γ-32P]kinase reaction in the presence of 300 ng (lanes 3, 5, and 7) or 600 ng (lanes 4, 6, and 8) of added MBP or MBP-Rep fusion protein as indicated. Lane 1, PRKX but no MBP; lane 2, S beads from luciferase-programmed RRL and no MBP.

Addition of histone H1 to the PRKX reaction had, initially, no apparent effect (Fig. 4a, lane 3). However, on long exposures a weak histone H1 kinase activity was observed for PRKX (not shown). We reasoned that while autophosphorylation might be the preferred reaction, H1 kinase activity might be evident upon longer incubation of the PRKX kinase assay mixture. Indeed, upon prolonged incubation of PRKX with histone H1, phosphorylation of the latter was clearly evident in addition to autophosphorylation activity (Fig. 4b, lane 3). Controls (Fig. 4b, lane 1) showed that no H1 kinase activity was carried over from the RRL by nonspecific association with the S beads. The observation of a delayed H1 kinase activity in relation to autophosphorylation suggested that the autophosphorylation event might be involved in activation of PRKX activity towards heterologous substrates (see Discussion).

We also investigated whether PRKX was capable of phosphorylating the PKA target peptide LRRASLG. We used an assay in which this kemptide is fluorochrome labelled and, in its unphosphorylated form, carries a net charge of +1. Phosphorylation of the peptide results in a net charge of −1; thus, the unphosphorylated and phosphorylated forms run in opposite directions in agarose gel electrophoresis. The relative amounts of peptide in each form are then observed by UV fluorescence. As shown in Fig. 4c, samples of S-tag-purified PRKX from RRL were able to phosphorylate the kemptide substrate, whereas S beads which had been incubated with luciferase-containing RRL did not have associated kemptide kinase activity.

A possible consequence of PRKX interaction with Rep78 might be an inhibition of kinase activity. The ability of MBP-Rep fusion proteins to inhibit PRKX autophosphorylation activity was therefore investigated (Fig. 4d). Incubation of S-tag-purified, RRL-derived PRKX with [γ-32P]ATP resulted in autophosphorylation, an observed previously (lane 1). Addition of increasing amounts of purified, maltose-eluted MBP had no effect on the kinase activity (lanes 3 and 4). However addition of increasing amounts of MBP-Rep78 fusion protein substantially inhibited the PRKX kinase activity (lanes 7 and 8). MBP-Rep68 also inhibited kinase activity, but to a lesser extent. The reasons for this last observation are not yet clear.

PRKX can activate CREB-dependent transcription.

The close homology between PRKX and PKAc, combined with the observation that PRKX could phosphorylate the PKA kemptide substrate, suggested that PRKX might be capable of modulating PKA-responsive transcriptional regulatory pathways through activation of CREB. We investigated whether PRKX could active CREB-dependent transcription by utilizing a transient-cotransfection model. In this system, a CREB activation domain/Gal4 DNA binding domain fusion protein is used to activate a luciferase reporter controlled by the Gal1 upstream activating sequence. Thus, when CREB is phosphorylated by activation of the PKA pathway, luciferase expression is strongly induced.

HeLa cells were cotransfected with the CREB/Gal4 fusion construct pFA-CREB and reporter plasmid pFR-Luc. In order to investigate the ability of PRKX to activate CREB, a full-length cDNA of PRKX was cloned under the control of the CMV promoter to produce pcDNA-PRKX. Cotransfection of pcDNA-PRKX with pFA-CREB and pFR-Luc resulted in induction of luciferase activity, indicating that PRKX could activate CREB-dependent transcription (Fig. 5, first two bars). The degree of induction (approximately 8-fold) was much less than the approximately 80-fold induction observed when a PKAc expression vector was used (see below). This suggested that PRKX might be less efficient than PKA in activating this pathway. However, the natural context of the PRKX start codon (26) is a poor match with the Kozak consensus for optimal translational initiation. We also cloned the S-tagged fragment encompassing amino acids 29 to 358 of PRKX from pCITE-PRKX into pCI, producing a construct (pCIS-PRKX) in which the AUG is in a strong Kozak context. Cotransfection experiments using pCIS-PRKX demonstrated a mean 23.5-fold activation of CREB (not shown).

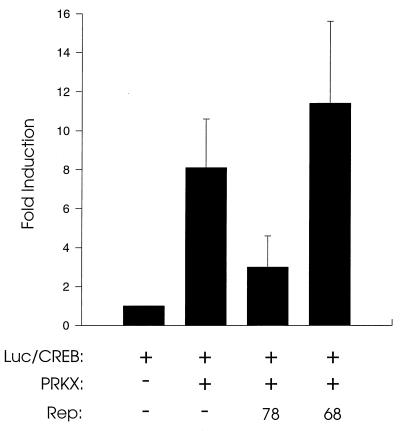

FIG. 5.

Transfection assay for CREB-dependent transcriptional activation. HeLa cells were cotransfected with Gal4 DNA binding domain/CREB fusion protein vector pFA-CREB and pFR-Luc, a luciferase reporter construct containing a minimal promoter and Gal1 upstream activating sequence. Samples were further cotransfected with the PRKX expression vector pcDNA-PRKX and with the pKex78 or pKex68 vector which express exclusively Rep78 and Rep68, respectively. Forty-eight hours later, cells were lysed and luciferase activity was determined. Results are presented relative to the levels found in cells transfected with pFR-Luc/pFA-CREB only. Means of at least three independent experiments, each conducted in duplicate, are shown, with standard deviations represented as error bars.

Rep78, but not Rep68, inhibits activation of CREB-dependent transcription by PRKX.

The effects of Rep proteins on CREB-dependent transcriptional activation were studied by using the cotransfection system described above. When a clone expressing exclusively Rep78 (pKex78) (22) was cotransfected into HeLa cells along with pFA-CREB, pFR-Luc, and pcDNA-PRKX, reduced activation of luciferase activity was observed (Fig. 5, third bar). This suppression was not observed when pKex68, which expresses exclusively Rep68, was used (fourth bar). This suggests that Rep78 interacts with and inhibits PRKX in cells; however, we cannot exclude the possibility that effects of Rep78 on transcription may contribute to the observed inhibition of CREB-dependent activation (see Discussion).

Rep78 interacts directly with PKAc and inhibits its catalytic activity.

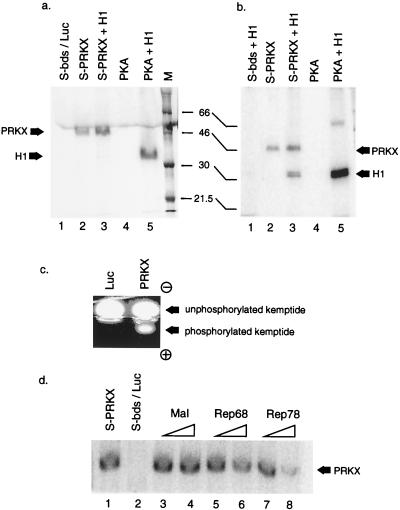

Since PRKX is a close homolog of PKAc, we investigated whether PKAc might also interact with Rep78, notwithstanding the fact that PKAc was not isolated from the yeast two-hybrid library screen. Purified PKAc (100 U) was mixed with purified MBP-Rep78, MBP-Rep68, or MBP immobilized on amylose beads. After extensive washing, protein associated with the beads was assayed for kinase activity by using the PKA-specific kemptide target. As shown in Fig. 6a, immobilized kinase activity was associated with MBP-Rep78 but not with MBP-Rep68 or MBP alone. In the absence of preincubation with PKAc, MBP-Rep78 did not demonstrate any kinase activity (not shown). We concluded that Rep78 interacts with PKAc in vitro and that, since both the Rep78 and the PKAc were present as purified proteins, the interaction most probably involves a direct physical contact between the two proteins.

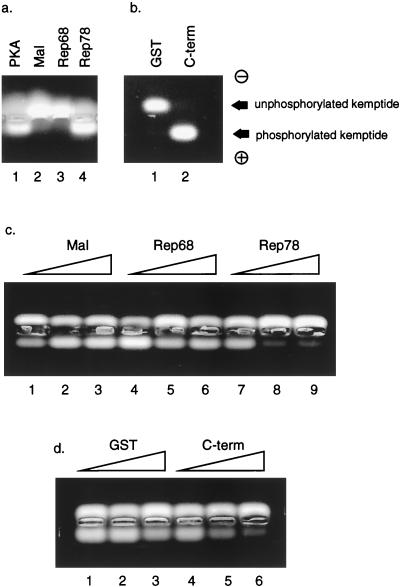

FIG. 6.

In vitro interaction between PKAc and Rep78. (a) Purified PKAc (100 U) was incubated with 0.5 to 1.0 μg of MBP (lane 2), MBP-Rep68 (lane 3), or MBP-Rep78 (lane 4) fusion protein immobilized on amylose beads. After washing, the beads were added to a kemptide phosphorylation assay. Phosphorylated kemptide was visualized by agarose gel electrophoresis and UV transillumination. In lane 1, PKAc was added directly to the kemptide assay. (b) Same as in panel a except that GST (lane 1) or GST–C-terminal protein (lane 2) was used to capture the PKAc. (c) One unit of purified PKAc was added to a 20-min kemptide assay, along with 0.3, 0.6, or 0.9 μg of MBP (lanes 1 to 3), MBP-Rep68 (lanes 4 to 6), or MBP-Rep78 (lanes 7 to 9) fusion protein. (d) One unit of PKAc was added to an 8-min kemptide assay with 30, 60, or 90 ng of GST (lanes 1 to 3) or GST–C-terminal protein (lanes 4 to 6).

Since the C-terminal region of Rep78 had been implicated in PRKX interaction, it seemed likely that the same domain was involved in interaction with PKAc. Incubation of immobilized GST–C-terminal protein with purified PKAc followed by extensive washing resulted in association of kemptide kinase activity with the solid phase (Fig. 6b, lane 2). Incubation of PKAc with immobilized GST alone did not result in the capture of kinase activity (lane 1). The interaction between Rep78 and PKA relies, therefore, on sequences between amino acids 482 and 621 of Rep78.

A possible consequence of the interaction between Rep78 and PKAc might be to inhibit kinase activity. To investigate this, we first determined a concentration of purified PKAc that produced approximately 50% conversion of the substrate to the phosphorylated form in the standard kemptide assay. Reactions were then performed in which this concentration of PKAc was incubated with increasing concentrations of maltose-eluted MBP, MBP-Rep68, or MBP-Rep78 during the kemptide assay (Fig. 6c). Addition of the higher concentrations of MBP-Rep78 to the assay resulted in an inhibition of PKAc, as evidenced by a reduced accumulation of phosphorylated kemptide (lanes 7 to 9). Addition of MBP alone or of MBP-Rep68 did not reveal an inhibitory effect (lanes 1 to 6). We noted, however, that prolonged incubation with high concentrations of MBP-Rep68 had a slight inhibitory effect (not shown). We concluded that the interaction between Rep78 and PKAc can inhibit the kinase activity of PKAc.

We investigated whether the C-terminal region of Rep78 was sufficient for inhibition of kinase activity (Fig. 6d).The kemptide phosphorylation inhibition assay described above was repeated, this time with eluted GST–C-terminal protein or GST protein for preincubation with PKAc. Increasing concentrations of GST-C-terminal protein inhibited kinase activity (Fig. 6d, lanes 4 to 6), whereas GST alone did not (lanes 1 to 3). It would appear, therefore, that the C-terminal 139 amino acids of Rep78 are sufficient to bind and inhibit PKAc kinase activity.

Rep78, but not Rep68, inhibits activation of CREB-dependent transcription by PKAc.

We used the CREB-dependent transcription system to investigate whether Rep78 proteins could block downstream functions in the PKA pathway. HeLa cells were cotransfected with pFA-CREB, pFR-LUC, and pFC-PKA, in addition to either pKex78, pKex68, or an equal amount of pCI vector. As shown in Fig. 7, reporter gene activity was greatly induced by the cotransfection of pFC-PKA. Addition of pKex78 to the assay resulted in severe repression of the CREB-dependent promoter activation. Little or no repression was observed when pKex68 was used. These data indicated that Rep78 can block PKA induction of CREB-dependent transcription in cells. While direct effects of Rep78 on transcription may contribute, these observations strongly suggest that Rep78 can block CREB activation by binding to and inhibiting the kinase activity of PKAc.

FIG. 7.

Transfection assay for Rep-mediated suppression of CREB-dependent transcriptional activation. HeLa cells were transfected with pFR-Luc and pFA-CREB. Some samples were cotransfected with the PKAc expression vector pFC-PKA and pKex68 or pKex78. Results are presented relative to the levels found in cells transfected with pFR-Luc/pFA-CREB only. Means of at least three independent experiments, each conducted in duplicate, are shown, with standard deviations represented as error bars.

DISCUSSION

In this study we have identified the catalytic subunit of the cAMP-dependent PKA and its X-linked homolog PRKX as cellular targets for AAV Rep78. The interaction was demonstrated in the yeast two-hybrid system, in vitro, and in mammalian cells with a CREB-dependent transcription system. In the case of PKAc, a direct interaction between the purified proteins was demonstrated. We consider it likely, therefore, that this represents a physiological interaction which occurs during AAV infection or replication.

PRKX was identified originally by positional cloning as a candidate for the chondrodysplasia punctata gene (26). It was shown that the mRNA was expressed in a wide range of adult and fetal tissues and that the gene is associated with a site of chromosomal instability. Little characterization of the protein encoded by PRKX has been conducted. Although PRKX is a close homolog of PKAc, it is not a PKA isoform. The homology between isoforms is typically greater than 90% identity in the catalytic domain, whereas the identity with PRKX in this region is only 49 to 55%. The closest known homolog of PRKX is Drosophila DC2 (24). The major Drosophila homolog of PKAc is DC0, and DC2 is unable to complement DC0 mutants, suggesting that their functions differ (39). By analogy, these observations suggest that PRKX and PKA might have related but separable functions.

We show here that PRKX exhibits kinase activity towards histone H1 and a peptide containing the PKA consensus recognition sequence. We further showed that a PRKX expression vector can induce CREB-dependent transcriptional activation, presumably by in vivo phosphorylation of CREB. In these respects, PRKX appears to function similarly to PKAc. However, some of the evidence suggests that PKA and PRKX may not be functionally analogous. First, PRKX was found to undergo autophosphorylation in vitro, whereas autophosphorylation of PKAc does not occur. Histone H1 kinase activity of PRKX was detected only after prolonged incubation of the kinase assay mixture. The observation that autophosphorylation occurred preferentially in the presence of excess histone H1 suggests that the autophosphorylation event might be involved in the activation of PRKX activity towards heterologous substrates. Moreover, although PRKX could activate CREB-dependent transcription, the degree of activation was far less than that achieved with a PKAc expression vector. This effect may be partly due to differences in PKA and PRKX expression levels, because the natural start codon of PRKX is in a weak Kozak consensus context (26). Replacement of the start codon with one close to the consensus increased the activation of CREB-dependent transcription to approximately 20-fold (data not shown), which is more than the 8-fold induction observed with the natural start codon (Fig. 5) but still less than the 80-fold induction typically observed with the PKAc expression vector (Fig. 7). Taken together, these observations suggest that the substrate preferences and regulatory mechanisms of PRKX and PKA may differ and that a rigorous comparison of PRKX and PKA activities is warranted.

PKA is a relatively ubiquitous enzyme, so the question arises as to why PKA did not emerge from the yeast two-hybrid system screen. Similarly, we did not detect interactions involving the HMG-1 and Sp1 proteins, which have been shown, by other methods, to interact with AAV Rep (11, 21, 45). Screening of the yeast two-hybrid library was difficult because of an endogenous transactivation activity of Rep78 and because yeast clones containing Rep78 grew very poorly. Therefore, the number of potential interactions screened was suboptimal, and there may be other Rep-interacting proteins which have not yet been identified in the screen, which is continuing.

In yeast, both the transactivation activity and growth inhibition phenotypes were localized to the C-terminal region of Rep78 (Fig. 2 and data not shown). The interaction with PRKX and PKA was clearly mapped to this C-terminal domain, which distinguishes Rep78 from Rep68. This domain contains motifs which may be involved in the formation of three zinc fingers and contains other sequence elements which have been implicated in the transactivation functions of adenovirus E1a (22, 55). Few studies have been able to address differences between Rep78 and Rep68 functions, partly because vectors expressing exclusively individual Rep proteins have only recently become available. For Rep68, a slightly reduced capacity to down regulate heterologous promoters has been noted, although the major sequences required for promoter down regulation are located in the N-terminal region (22). Rep68-MBP fusion protein produced in E. coli has been shown to be sufficient to sponsor AAV replication in vitro (54). Recently it has been shown that Rep78 proteins can self-associate (20, 49). As shown in the present paper, self-association can also be observed for Rep68 (Fig. 3). Therefore, a biological function which is specific only to Rep78 remains to be clarified. The Rep78 C-terminal domain which interacts with PRKX and PKAc is shared by the p19-derived Rep52 protein. This suggests that Rep52 also may interact with these cellular targets; however, this interaction has yet to be demonstrated experimentally.

PKA activity could be detected by a pull-down assay with MBP-Rep78 (Fig. 6a); however, Rep78 was also found to inhibit kinase activity (Fig. 6c and d). In the pull-down assays, PKAc was present in excess, and the duration of the kinase assay was longer than that in the inhibition assays. The kinase activity detected in the pull-down assays probably results from free PKAc which dissociated from the complexes during the kinase assay, suggesting that inhibition may be reversible. In the in vitro assays, we sometimes observed that Rep68 could inhibit phosphorylation, although to a much lesser extent. This suggests that, although Rep68 clearly cannot bind PRKX and PKA, domains outside the amino acid 529 to 621 intro region might contribute to inhibition of kinase activity. These domains might have a weak effect in in vitro assays where high concentrations of purified Rep68 proteins are present and the requirement for tight binding is reduced. A detailed analysis of the structural requirements of both PKA and Rep proteins for binding and kinase inhibition is in progress.

In cotransfection assays, Rep78 clearly inhibited CREB-dependent transcriptional activation; however, the mechanism by which this is achieved is not certain. The in vitro data suggest that inhibition of PRKX and PKA kinase activities makes the major contribution, since the system is highly dependent on CREB phosphorylation. However one must also consider that Rep has suppressive activities on heterologous promoters (18, 19, 31, 42). The CREB, PRKX, PKA, and Rep expression constructs used in this system all utilized the CMV immediate-early promoter-enhancer, which is relatively insensitive to Rep suppression (1). The suppression of heterologous promoters by Rep has been shown to be mediated, at lest in some cases, through Sp1 sites (21). The Gal4-CREB-responsive promoter in the reporter construct pFR-Luc is very simple, comprising the Gal upstream activating sequence and the TATA box from adenovirus E1b. The E1b promoter Sp1 site is not present in the pFR-Luc construct; therefore, direct effects of Rep on transcription from this promoter should be minimal. This view is supported by the observations that Rep68 was unable to suppress CREB-dependent transcriptional activation from this promoter (Fig. 5 and 7). Accordingly, we favor the interpretation that Rep78 inhibits the kinase activity of PRKX and PKA in cells, thereby reducing CREB phosphorylation and consequently suppressing reporter gene activation.

What might be the functional consequences of the interaction between Rep78 and PKA or PRKX? One possibility is that the Rep78 is a substrate for PRKX and/or PKA. AAV Rep proteins are known to be phosphorylated, and their phosphorylation state changes during the replication cycle (10). However, we have not been able to demonstrate phosphorylation of MBP-Rep fusion proteins by either PRKX or PKA (data not shown).

A number of viruses have subsumed PKA/CREB pathways to regulate their gene expression; examples include human T-cell leukemia virus type 1, human immunodeficiency virus type 1, adenovirus, HSV, and Epstein-Barr virus (12, 15, 28, 33, 41, 47, 50, 59, 63). The cAMP response pathway components are frequently used to control switches from early to late or latent to lytic replication modes. For example, adenovirus E1a protein can transactivate genes containing CREs via an interaction with CBP/p300 (44). In addition, the E1a, E3, and E4 promoters of adenovirus contain CREs (34). The HSV latency-associated transcript and UL9 gene promoters are cAMP responsive, and this response has been associated with induction of lytic replication (33). The HSV ICP4 protein has been demonstrated to provide a crucial helper function for both HSV and AAV replication (40, 56). ICP4 is a substrate for PKA, and its phosphorylation promotes HSV lytic replication (59). These observations suggest that one function of AAV Rep78 might be to inhibit the utilization of cAMP pathways by helper viruses and thereby inhibit productive replication of the helper.

Few viruses are known to inhibit cAMP pathways. The hepatitis C virus NS3 protein has been shown to bind to PKAc, inhibiting its catalytic activity and nuclear translocation (6, 7). The poliovirus 3Cpro protease has been shown to cleave CREB (61). The roles of these interactions in the respective virus life cycles are not yet understood. Both AAV2 and the autonomous parvovirus minute virus of mice (MVMp) have CRE elements in the promoters controlling the major nonstructural proteins (13, 46). The function of the AAV2 p5 promoter CRE has not been extensively studied; however, cAMP-dependent stimulation of the CRE of minute virus of mice has a negative regulatory effect (46). This supports a model wherein Rep78 suppression of PRKX/PKA may be involved in an autoregulatory loop controlling Rep gene expression. Accordingly, we suggest that the function of the Rep-PRKX/PKA interaction may be to influence the balance between AAV and helper virus replication.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Ken Berns, J. Kleinschmidt, G. Rappold, and Massimo Tommasino for their generous gifts of plasmids and Stephen Lyons for excellent technical assistance.

This work was supported by the Cancer Research Campaign and the Association for International Cancer Research.

REFERENCES

- 1.Araujo J C, Doniger J, Stöppler H, Sadaie M R, Rosenthal L J. Cell lines containing and expressing the human herpesvirus 6A ts gene are protected from both H-ras and BPV-1 transformation. Oncogene. 1997;14:937–943. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1200899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ashktorab H, Srivastava A. Identification of nuclear proteins that specifically interact with adeno-associated virus type 2 inverted terminal repeat hairpin DNA. J Virol. 1989;63:3034–3039. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.7.3034-3039.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bantel-Schaal U, Stohr M. Influence of adeno-associated virus on adherence and growth properties of normal cells. J Virol. 1992;66:773–779. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.2.773-779.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bantel-Schaal U, zur Hausen H. Adeno-associated viruses inhibit SV40 DNA amplification and replication of herpes simplex virus in SV40-transformed hamster cells. Virology. 1988;164:64–74. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(88)90620-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berns K I. Parvoviridae: the viruses and their replication. In: Fields B N, Knipe D M, Howley P M, et al., editors. Field’s virology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Lippincott-Raven Publishers; 1996. pp. 2173–2198. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Borowski P, Heiland M, Oehlmann K, Becker B, Kornetzky L, Feucht H, Laufs R. Non-structural protein 3 of hepatitis C virus inhibits phosphorylation mediated by cAMP-dependent protein kinase. Eur J Biochem. 1996;237:611–618. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1996.0611p.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Borowski P, Oehlmann K, Heiland M, Laufs R. Nonstructural protein 3 of hepatitis C virus blocks the distribution of the free catalytic subunit of cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase. J Virol. 1997;71:2838–2843. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.4.2838-2843.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carter B J, Laughlin C A, de la Maza L M, Myers M. Adeno-associated virus autointerference. Virology. 1979;92:449–462. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(79)90149-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Casto B C, Atchison R W, Hammond W. Studies on the relationship between adeno-associated virus type 1 (AAV-1) and adenoviruses. I. Replication of AAV in certain cell cultures and its effects on helper adenovirus. Virology. 1967;32:52–59. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(67)90251-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Collaco R, Prasad K-M R, Trempe J P. Phosphorylation of the adeno-associated virus replication proteins. Virology. 1997;232:332–336. doi: 10.1006/viro.1997.8563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Costello E, Saudan P, Winocour E, Pizer L, Beard P. High mobility group chromosomal protein 1 binds to the adeno-associated virus replication protein (Rep) and promotes Rep-mediated site-specific cleavage of DNA, ATPase activity and transcriptional repression. EMBO J. 1997;16:5943–5954. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.19.5943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Flamand L, Menezes J. Cyclic AMP-responsive element-dependent activation of Epstein-Barr virus zebra promoter by human herpesvirus 6. J Virol. 1996;70:1784–1791. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.3.1784-1791.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Flotte T R, Solow R, Owens R A, Afione S, Zeitlin P L, Carter B J. Gene expression from adeno-associated virus vectors in airway epithelial cells. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1992;7:349–356. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb/7.3.349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Georg-Fries B, Biederlack S, Wolf J, zur Hausen H. Analysis of proteins, helper dependence, and seroepidemiology of a new human parvovirus. Virology. 1984;134:64–71. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(84)90272-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Giam C-Z, Xu Y-L. HTLV-1 Tax gene product activates transcription via pre-existing cellular factors and cAMP responsive element. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:15236–15241. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hermanns J, Shulze A, Jansen-Dürr P, Kleinschmidt J A, Schmidt R, zur Hausen H. Infection of primary cells by adeno-associated virus type 2 results in a modulation of cell cycle-regulating proteins. J Virol. 1997;71:6020–6027. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.8.6020-6027.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hermonat P L. The adeno-associated virus rep78 gene inhibits cellular transformation induced by bovine papillomavirus. Virology. 1989;172:253–261. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(89)90127-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hermonat P L. Down-regulation of the human c-fos and c-myc proto-oncogene promoters by adeno-associated virus Rep78. Cancer Lett. 1994;81:129–136. doi: 10.1016/0304-3835(94)90193-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hermonat P L. Adeno-associated virus inhibits human papillomavirus type 16: a viral interaction implicated in cervical cancer. Cancer Res. 1994;54:2278–2281. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hermonat P L, Batchu R B. The adeno-associated virus Rep78 major regulatory protein forms multimeric complexes and the domain for this activity is contained within the carboxyl-half of the molecule. FEBS Lett. 1997;401:180–184. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(96)01469-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hermonat P L, Santin A D, Batchu R B. The adeno-associated virus Rep78 major regulatory/transformation suppressor protein binds cellular Sp1 in vitro and evidence of a biological effect. Cancer Res. 1996;56:5299–5304. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hörer M, Weger S, Butz K, Hoppe-Seyler F, Geisen C, Kleinschmidt J A. Mutational analysis of adeno-associated virus Rep protein-mediated inhibition of heterologous and homologous promoters. J Virol. 1995;69:5485–5496. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.9.5485-5496.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Im D S, Muzyczka N. The AAV origin binding protein Rep68 is an ATP-dependent site-specific endonuclease with DNA helicase activity. Cell. 1990;61:447–457. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90526-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kalderon D, Rubin G M. Isolation and characterisation of Drosophila cAMP-dependent protein kinase genes. Genes Dev. 1988;2:1539–1556. doi: 10.1101/gad.2.12a.1539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Khleif S N, Myers T, Carter B J, Trempe J P. Inhibition of cellular transformation by the adeno-associated virus rep gene. Virology. 1991;181:738–741. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(91)90909-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Klink A, Schiebel K, Winkelmann M, Rao E, Horsthemke B, Ludecke H J, Claussen U, Scherer G, Rappold G. The human protein kinase gene PKX1 on Xp22.3 displays Xp/Yp homology and is a site of chromosomal instability. Hum Mol Genet. 1995;4:869–878. doi: 10.1093/hmg/4.5.869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kotin R M, Menninger J C, Ward D C, Berns K I. Mapping and direct visualization of a region-specific viral DNA integration site on chromosome 19q13-qter. Genomics. 1991;10:831–834. doi: 10.1016/0888-7543(91)90470-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kwok R P, Lawrence M E, Lundblad J R, Goldman P S, Shih H, Connor L M, Marriott S J, Goodman R H. Control of cAMP-regulated enhancers by the viral transactivator Tax through CREB and the co-activator CBP. Nature. 1996;380:642–646. doi: 10.1038/380642a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kyöstiö S R M, Owens R A, Weitzman M D, Antoni B A, Chejanovsky N, Carter B J. Analysis of adeno-associated virus (AAV) wild-type and mutant Rep proteins for their abilities to negatively regulate AAV p5 and p19 mRNA levels. J Virol. 1994;68:2947–2957. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.5.2947-2957.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kyöstiö S R M, Wonderling R S, Owens R A. Negative regulation of the adeno-associated virus (AAV) p5 promoter involves both the p5 Rep binding site and the consensus ATP-binding motif of the AAV Rep68 protein. J Virol. 1995;69:6787–6796. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.11.6787-6796.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Labow M A, Graf L H, Jr, Berns K I. Adeno-associated virus gene expression inhibits cellular transformation by heterologous genes. Mol Cell Biol. 1987;7:1320–1325. doi: 10.1128/mcb.7.4.1320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Labow M A, Hermonat P L, Berns K I. Positive and negative autoregulation of the adeno-associated virus type 2 genome. J Virol. 1986;60:251–258. doi: 10.1128/jvi.60.1.251-258.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Leib D A, Nadeau K C, Rundle S A, Shaffer P A. The promoter of the latency-associated transcripts of herpes simplex virus type 1 contains a functional cAMP-response element: role of the latency-associated transcripts and cAMP in reactivation of viral latency. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:48–52. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.1.48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Leza M A, Hearing P. Independent cyclic AMP and E1A induction of adenovirus early region 4 expression. J Virol. 1989;63:3057–3064. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.7.3057-3064.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Linden R M, Winocour E, Berns K I. The recombination signals for adeno-associated virus site-specific integration. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:7966–7972. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.15.7966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mayor H D, Drake S, Stahmann J, Mumford D M. Antibodies to adeno-associated satellite virus and herpes simplex in sera from cancer patients and normal adults. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1976;126:100–104. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(76)90472-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McCarty D M, Pereira D J, Zolothkhin I, Zhou Z, Ryan J H, Muzyczka N. Identification of linear DNA sequences that specifically bind the adeno-associated virus Rep protein. J Virol. 1994;68:4988–4997. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.8.4988-4997.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McCarty D M, Ryan J H, Zolothkhin S, Zhou X, Muzyczka N. Interaction of the adeno-associated virus Rep protein with a sequence within the A palindrome of the viral terminal repeat. J Virol. 1994;68:4998–5006. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.8.4998-5006.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Melendez A, Li W, Kalderon D. Activity, expression and function of a second Drosophila protein kinase A catalytic subunit gene. Genetics. 1995;141:1507–1520. doi: 10.1093/genetics/141.4.1507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mishra L, Rose J A. Adeno-associated virus DNA replication is induced by genes that are essential for HSV-1 DNA synthesis. Virology. 1990;179:632–639. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(90)90130-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nokta M A, Pollard R B. Human immunodeficiency virus replication: modulation by cellular levels of cAMP. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 1992;8:1255–1261. doi: 10.1089/aid.1992.8.1255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Oelze I, Rittner K, Sczakiel G. Adeno-associated virus type 2 rep gene-mediated inhibition of basal gene expression of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 involves its negative regulatory functions. J Virol. 1994;68:1229–1233. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.2.1229-1233.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ostrove J M, Duckworth D H, Berns K I. Inhibition of adenovirus-transformed cell oncogenicity by adeno-associated virus. Virology. 1981;113:521–533. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(81)90180-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pei R, Berk A J. Multiple transcription factor binding sites mediate adenovirus E1a transactivation. J Virol. 1989;63:3499–3506. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.8.3499-3506.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pereira D J, Muzyczka N. The cellular transcription factor Sp1 and an unknown cellular protein are required to mediate Rep protein activation of the adeno-associated virus p19 promoter. J Virol. 1997;71:1747–1756. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.3.1747-1756.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Perros M, Deleu L, Vanacker J-M, Kherrouche Z, Spruyt N, Faisst S, Rommelaere J. Upstream CREs participate in the basal activity of minute virus of mice promoter P4 and its stimulation in ras-transformed cells. J Virol. 1995;69:5506–5515. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.9.5506-5515.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rabbi M F, Saifuddin M, Gu D S, Kagnoff M F, Roebuck K A. U5 region of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 long terminal repeat contains TRE-like cAMP responsive elements that bind both AP-1 and CREB/ATF proteins. Virology. 1997;233:235–245. doi: 10.1006/viro.1997.8602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rittner K, Heilbronn R, Kleinschmidt J A, Sczakiel G. Adeno-associated virus type 2-mediated inhibition of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) replication: involvement of the p78rep/p68rep and the HIV-1 long terminal repeat. J Gen Virol. 1992;73:2977–2981. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-73-11-2977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Smith R H, Spano A J, Kotin R M. The Rep78 gene product of adeno-associated virus (AAV) self-associates to form a hexameric complex in the presence of AAV ori sequences. J Virol. 1997;71:4461–4471. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.6.4461-4471.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49a.Srivastava A, Lusby E W, Berns K I. Nucleotide sequence and organization of the adeno-associated virus 2 genome. J Virol. 1983;45:555–564. doi: 10.1128/jvi.45.2.555-564.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tan T H, Jia R, Roeder R G. Utilization of signal transduction pathway by the human T-cell leukemia virus type I transcriptional activator tax. J Virol. 1989;63:3761–3768. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.9.3761-3768.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Walz C, Schlehofer J R. Modification of some biological properties of HeLa cells containing adeno-associated virus DNA integrated into chromosome 17. J Virol. 1992;66:2990–3002. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.5.2990-3002.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Walz C, Schlehofer J R, Flentje M, Rudat V, zur Hausen H. Adeno-associated virus sensitizes HeLa cell tumors to gamma rays. J Virol. 1992;66:5651–5657. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.9.5651-5657.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Walz C, Deprez A, Dupressior T, Durst M, Rabreau M, Schlehofer J R. Interaction of human papillomavirus type 16 and adeno-associated virus type 2 co-infecting human cervical epithelium. J Gen Virol. 1997;78:1441–1452. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-78-6-1441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ward P, Urcelay E, Kotin R, Safer B, Berns K I. Adeno-associated virus DNA replication in vitro: activation by a maltose binding protein/Rep68 fusion protein. J Virol. 1994;68:6029–6037. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.9.6029-6037.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Webster C L, Zhang K, Chance B, Ayene J, Culp J S, Huang W J, Wu F Y-H, Ricciardi R P. Conversion of the E1A Cys4 zinc finger to a nonfunctional His2 Cys2 zinc finger by a single point mutation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:9989–9993. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.22.9989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Weindler F W, Heilbronn R. A subset of herpes simplex virus replication genes provides helper functions for productive adeno-associated virus replication. J Virol. 1991;65:2476–2483. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.5.2476-2483.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Weitzman M D, Kyöstiö S R M, Kotin R M, Owens R A. Adeno-associated virus (AAV) Rep proteins mediate complex formation between AAV DNA and its integration site in human DNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:5808–5812. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.13.5808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wonderling R S, Kyöstiö S R M, Owens R A. A maltose-binding protein/adeno-associated virus Rep68 fusion protein has DNA-RNA helicase and ATPase activities. J Virol. 1995;69:3542–3548. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.6.3542-3548.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Xia K, Knipe D M, DeLuca N A. Role of protein kinase A and the serine-rich region of herpes simplex virus type 1 ICP4 in viral replication. J Virol. 1996;70:1050–1060. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.2.1050-1060.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Xiao X, Li J, Samulski R J. Production of high-titer recombinant adeno-associated virus vectors in the absence of helper adenovirus. J Virol. 1998;72:2224–2232. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.3.2224-2232.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yalamanchili P, Datta U, Dasgupta A. Inhibition of host cell transcription by poliovirus: cleavage of transcription factor CREB by poliovirus-encoded protease 3Cpro. J Virol. 1997;71:1220–1226. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.2.1220-1226.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yang Q, Chen F, Trempe J P. Characterization of cell lines that inducibly express the adeno-associated virus Rep proteins. J Virol. 1994;68:4847–4856. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.8.4847-4856.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Yin M J, Gaynor R B. Complex formation between CREB and Tax enhances the binding affinity of CREB for the human T-cell leukemia virus type 1 21-base-pair repeats. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:3156–3168. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.6.3156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]