ABSTRACT

Castleman disease is an unusual, benign disorder of unknown etiology, characterized by the proliferation of the lymphoid tissue. It can have a unicentric or multicentric presentation, depending on the number of lymph nodes involved. On clinical examination and imaging, it can imitate a malignancy and the diagnosis can only be confirmed on histopathological examination. Retroperitoneal location and presentation in the pediatric age group are extremely rare. We report a case of an adolescent girl with a unicentric lymph nodal mass in the portocaval space which was completely excised.

KEYWORDS: Castleman disease, children, excision, pediatric, portocaval, retroperitoneum, surgery

INTRODUCTION

Castleman disease (CD) is a unique and poorly understood, benign lymphoproliferative disorder.[1] It may be unicentric CD (UCD) or multicentric CD (MCD), depending on the number of lymph nodes involved.[2,3] Definitive diagnosis of CD is based on histopathological (HPE) findings and classified as hyaline vascular variant (HVCD), plasma cell variant (PCCD), and mixed hyaline vascular with plasma cell variant.[4,5] UCD of the portocaval region (i.e., located between the main portal vein [MPV] anteriorly and inferior vena cava [IVC] posteriorly) has not been previously reported in the literature. In this report, we aim to highlight the challenges faced in the diagnosis and surgical management of a rare case of UCD in an adolescent girl.

CASE REPORT

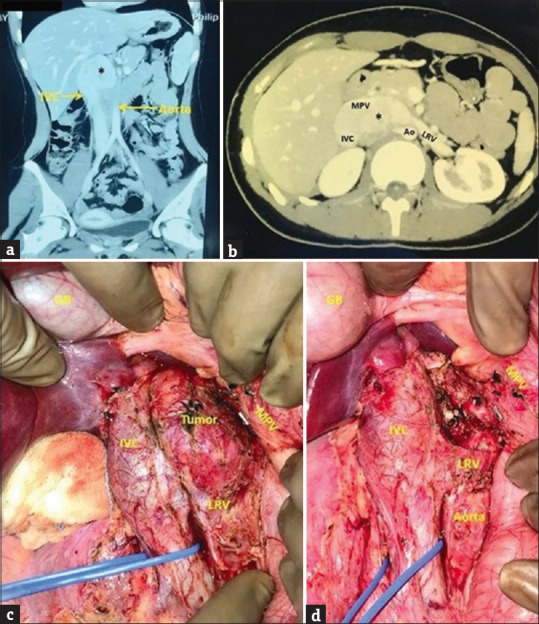

A 14-year-old girl presented with a 1-year history of intermittent dull aches in the right upper abdomen with increased severity in the past 3–4 months. The pain was not associated with nausea, vomiting, fever, abdominal distension, change in bowel habits, urinary symptoms, weight loss, headache, weakness, or sweating. Physical examination and laboratory investigations, including 24 h urinary catecholamine levels were normal. Ultrasonography and a triphasic CT abdomen revealed a well-defined, heterogeneously enhancing mass (6 cm × 4 cm × 3.5 cm), in the right paravertebral region (D12-L2) displacing MPV anteriorly, IVC laterally, and left renal vein (LRV) inferiorly [Figure 1a and b]. Fine-needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) done at another hospital revealed reactive lymph nodal hyperplasia. DOTANOC positron emission tomography computed tomography (PETCT) scan showed no tracer avidity in the retroperitoneal mass and no other somatostatin receptors (SSTR) expressing lesions. In view of the paravertebral location of the tumor and the adolescent age, the first differential considered was a paraganglioma. Another close differential diagnosis for a tumor in the paravertebral location is ganglioneuroma.

Figure 1.

(a and b) Contrast-enhanced computed tomography abdomen (a) coronal section, (b) axial section showing a well-defined, heterogeneously enhancing mass (asterisk) in the right paravertebral region (D12-L2), closely abutting and displacing the main portal vein (MPV) anteriorly, inferior vena cava (IVC) laterally, left renal vein (LRV) inferiorly and aorta (Ao) posteriorly (c) intraoperative photograph showing tumor enveloped by IVC anterolaterally, MPV anteromedially, Ao posteriorly and LRV inferiorly (d) tumor bed after complete excision showing multiple small arterial and venous branches to the tumor from IVC, Ao, MPV which have been ligated with silk sutures and divided; GB: Gall bladder. MPV: Main portal vein, IVC: Inferior vena cava, LRV: Left renal vein, Ao: Aorta

At laparotomy, a 6 cm × 5 cm × 4 cm firm, retroperitoneal, paravertebral tumor was found, enveloped by IVC anterolaterally, MPV anteromedially, aorta posteriorly, and LRV inferiorly [Figure 1c]. Vascular control of IVC was taken. IVC, MPV, and LRV were dissected away from the tumor. Multiple small arterial branches from the aorta and small venous tributaries to IVC and MPV were carefully dissected, ligated, and divided [Figure 1d]. The tumor was completely resected (R0) with no tumor rupture or spill and no evidence of liver or peritoneal deposits, ascites, or lymphadenopathy. The tumor bed was marked with metallic clips. The postoperative period was uneventful. The patient was discharged on the 3rd postoperative day.

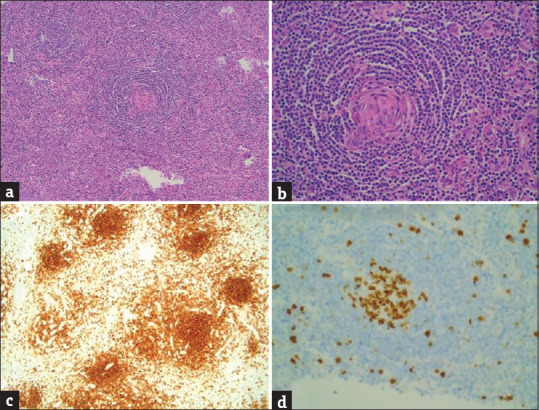

On histopathology, the sections from the portocaval mass showed a lymph node with a thickened capsule and obliterated sinuses. The germinal centers were at different stages of regression, encircled by a hyperplastic mantle zone containing concentrically arranged small lymphocytes forming an onion ring-like arrangement [Figure 2a] with radial penetration of sclerosed vessel (“lollipop” appearance) [Figure 2b] and extensive interfollicular vascular proliferation.

Figure 2.

Histomorphology showing (a) mantle zone lymphocytes surrounding atretic follicles concentrically arranged with a broad zone of small, mature lymphocytes having condensed chromatin and minimal cytoplasm, imparting an “onion-skin” like structure (H and E, ×400). (b) Radial penetration of atretic follicles by hyalinized blood vessels and concentric mantle zones imparting a “lollipop” appearance (H and E, ×400). (c) Cells were positive for CD20 in the follicles (IHC, ×400). (d) Ki-67 proliferation index was ~ 50% in the germinal centers while interfollicular areas showed a Ki-67 index of 20%–0% (IHC, ×400)

On immunohistochemistry, the cells were positive for CD20 in the follicles [Figure 2c] and CD3 in the interfollicular cells. CD138 stain showed focal positivity. CD10 and CD23 were negative. Ki-67 index was 50% in the germinal centers and 20%–30% in interfollicular areas [Figure 2d]. The final HPE diagnosis was HVCD. At 6 months’ follow-up, the patient is asymptomatic with normal blood investigations and imaging.

DISCUSSION

The CD is a rare, benign, heterogeneous group of lymphoproliferative disorders of unknown etiology that share common morphological features on lymph node biopsy. It was originally described by Castleman and Towne in 1956 as a large, benign, and asymptomatic mass involving the mediastinal nodes.[1]

It can affect any group of lymph nodes, imitating both benign and malignant lesions.[2] Microscopically, it is classified as HVCD – 90%, PCCD – 10%, and mixed hyaline vascular with plasma cell variant.[2] Clinically, it can be UCD or MCD, depending on the number of nodes involved.[2] Recently, human herpesvirus 8 (HHV-8), also known as Kaposi’s sarcoma herpes virus, has been demonstrated in 50% of unicentric PC type CD and most of MCD.[2]

UCD presents as a painless, benign, and solitary mass at a single anatomic site. It is asymptomatic at first but becomes symptomatic when the surrounding structures are compressed due to progressive enlargement.[2] In contrast, MCD involves multiple sites with systemic inflammatory symptoms such as fever, night sweats, and weight loss due to the release of proinflammatory cytokines.[2] Laboratory abnormalities include anemia, thrombocytopenia or thrombocytosis, hypoalbuminemia, renal dysfunction, polyclonal hypergammaglobulinemia, and elevated interleukin (IL)-6. Severe cases of MCD may progress to multi-organ failure and even mortality.[2]

Diagnosis of CD is always challenging as it does not have specific features that could distinguish it from other diseases causing lymphadenopathy. CT or magnetic resonance imaging reveals a homogeneous mass with immediate enhancement and slow washout with central areas of fibrosis.[3] On fluorodeoxyglucose-PETCT, CD exhibits only moderate radiotracer uptake with reported SUVmax between 4.7 and 5.8. Most lymphomas express much higher average SUVs.[3]

Definitive diagnosis of CD is based on postoperative HPE findings such as atretic follicles with hyalinization, a proliferation of vasculature, and nonapparent sinuses.[2,4] Hyperplastic mantle zones, composed of concentric rings of small lymphoid cells surround atrophic germinal centers (onion skin pattern). Hyalinized blood vessels penetrate the depleted germinal centers (lollipop lesions).[2,4] Immunohistochemistry acts as a useful tool to differentiate CD from other differentials such as reactive follicular hyperplasia, mantle cell lymphoma, follicular lymphoma, and nodal marginal zone lymphoma.[2,4]

Chisholm and Fleming compared the morphologic, laboratory, and clinical features of asymptomatic and symptomatic CD in 39 pediatric patients.[4] Of these, 37 had HVCD, 8 of which were clinically symptomatic. These eight patients demonstrated abnormal laboratory findings; HPE showed more hyperplastic germinal centers, reduced “onion skinning” of mantle zones, and fewer “lollipop” formations. Thus, lymph nodes from asymptomatic patients generally demonstrated the classic HVCD histology.[4]

Complete surgical excision of UCD is the treatment of choice.[5] The majority can be managed with complete resection, resulting in an overall 5-year survival of >90%.[5] Surgical excision of UCD may be technically challenging as was in our case, especially in the mediastinal and retroperitoneal region. Treatment options for MCD include surgery, chemotherapy, corticosteroids, radiotherapy, and autologous stem cell transplantation. These target the CD20 or IL-6 pathways or HHV-8 replication and have varying outcomes.[3,5]

To conclude, CD can imitate a benign or malignant tumor and though rare, it should be considered one of the differential diagnoses for a retroperitoneal tumor in an adolescent. Preoperative diagnosis of CD is difficult, and confirmation is based on postoperative HPE findings. The ideal therapeutic approach for UCD is complete surgical excision. Surgeons should be aware of this pathology to allow intraoperative recognition.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form, the patient(s) has/have given his/her/their consent for his/her/their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published, and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Castleman B, Iverson L, Menendez VP. Localized mediastinal lymphnode hyperplasia resembling thymoma. Cancer. 1956;9:822–30. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(195607/08)9:4<822::aid-cncr2820090430>3.0.co;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carbone A, Borok M, Damania B, Gloghini A, Polizzotto MN, Jayanthan RK, et al. Castleman disease. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2021;7:84. doi: 10.1038/s41572-021-00317-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bonekamp D, Horton KM, Hruban RH, Fishman EK. Castleman disease: The great mimic. Radiographics. 2011;31:1793–807. doi: 10.1148/rg.316115502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chisholm KM, Fleming MD. Histologic and laboratory characteristics of symptomatic and asymptomatic Castleman disease in the pediatric population. Am J Clin Pathol. 2020;153:821–32. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/aqaa011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van Rhee F, Oksenhendler E, Srkalovic G, Voorhees P, Lim M, Dispenzieri A, et al. International evidence-based consensus diagnostic and treatment guidelines for unicentric Castleman disease. Blood Adv. 2020;4:6039–50. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2020003334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]