Abstract

Although the ability of serum-neutralizing antibodies to protect against picornavirus infection is well established, the contribution of cell-mediated immunity to protection is uncertain. Using major histocompatibility complex class II-deficient (RHAβ−/−) mice, which are unable to mediate CD4+ T-lymphocyte-dependent humoral responses, we demonstrated antibody-independent protection against lethal encephalomyocarditis virus (EMCV) infection in the natural host. The majority of RHAβ−/− mice inoculated with 104 PFU of attenuated Mengo virus (vMC24) resolved infection and were resistant to lethal challenge with the highly virulent, serotypically identical cardiovirus, EMCV. Protection in these mice was in the absence of detectable serum-neutralizing antibodies. Depletion of CD8+ T lymphocytes prior to lethal EMCV challenge ablated protection in vMC24-immunized RHAβ−/− mice. The CD8+ T-lymphocyte-dependent protection observed in vivo may, in part, be the result of cytotoxic T-lymphocyte (CTL) activity, as CD8+ T splenocytes exhibited in vitro cytolysis of EMCV-infected targets. The existence of virus-specific CD8+ T-lymphocyte memory in these mice was demonstrated by increased expression of cell surface activation markers CD25, CD69, CD71, and CTLA-4 following antigen-specific reactivation in vitro. Although recall response in vMC24-immunized RHAβ−/− mice was intact and effectual shortly after immunization, protection abated over time, as only 3 of 10 vMC24-immunized RHAβ−/− mice survived when rechallenged 90 days later. The present study demonstrating CD8+ T-lymphocyte-dependent protection in the absence of serum-neutralizing antibodies, coupled with our previous results indicating that vMC24-specific CD4+ T lymphocytes confer protection against lethal EMCV in the absence of prophylactic antibodies, suggests the existence of nonhumoral protective mechanisms against picornavirus infections.

Picornaviruses are a family of positive-strand RNA viruses that are responsible for a variety of devastating human and animal diseases. The family is divided into six genera, enteroviruses, hepatoviruses, parechoviruses, rhinoviruses, aphthoviruses, and cardioviruses, that include such members as poliovirus, human rhinovirus, foot-and-mouth disease virus, and encephalomyocarditis virus (EMCV) (42). Mice are highly susceptible and considered the natural host for cardioviruses such as Mengo virus and EMCV, (7, 35), infections with which result in acute neurotropic disease producing rapid and lethal meningoencephalomyelitis (16, 47). The ability to protect mice against cardiovirus-induced disease by the elicitation or passive transfer of neutralizing antibodies is well documented (2, 13, 26, 41). Current dogma asserts that prophylaxis against picornavirus infection is afforded by serum-neutralizing antibodies (23, 25, 28). Existing picornavirus vaccines (23, 25), in addition to current strategies using recombinant-attenuated and protein-subunit vaccines (27, 32), are designed to elicit a protective neutralizing antibody response to capsid determinants. Indeed, serum-neutralizing titers are used to evaluate host immune status to a particular picornavirus pathogen.

Mengo virus and EMCV are members of a single cardiovirus serotype and are indistinguishable by immune sera (42). The dramatic attenuation of Mengo virus by a truncation in the 5′-noncoding-region poly(C) tract preserves complete integrity of all virally encoded proteins (10), allowing in vivo exposure of structural and nonstructural proteins that may elicit an immune response. Normal immunocompetent mice immunized with an attenuated strain of Mengo virus (vMC24) elicit high serum-neutralizing antibody titers and are protected from lethal EMCV challenge (9, 29). In addition to invoking a potent humoral response, vMC24 is also capable of eliciting a cell-mediated immune (CMI) response (29) as an immunodominant CD8+ cytotoxic T-lymphocyte (CTL) epitope has been recently identified in the VP2 capsid protein in vMC24-immunized C57BL/6 mice (11).

Earlier investigations of CMI responses to cardioviruses in T-cell deficiency models vacillated between elucidating the immunopathologic role that these cells may contribute in disease and discerning the beneficial aspects that T cells may mediate in protection. T-cell subset depletion of BALB/c mice with anti-CD4 or anti-CD8 antibodies prior to EMCV infection ameliorated clinical disease and reduced the frequency of demyelination (44), suggesting a participatory role for T cells in pathology. Conversely, mice rendered CD4 deficient prior to infection with Theiler’s murine encephalomyelitis virus (TMEV), another murine cardiovirus, failed to produce neutralizing antibodies; consequently, they were unable to clear virus from the central nervous system (CNS) and died from overwhelming encephalitis (49). Similarly, infection of major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I (β2-microglobulin)-deficient (β2m−/−) mice with TMEV indicates a requisite role for CD8+ T cells in viral clearance and suggests that CD8+ T cells are not major mediators in demyelination or disease (13, 39).

More recently, researchers have begun to unveil the beneficial role that CD8+ T cells may have in resolving infection and immune protection. An early and abundant TMEV-specific CD8+ T-cell response is critical in determining the balance between viral persistence or resolution of infection (6, 22, 30). Using vMC24-immunized C57BL/6 mice, Escriou et al identified an immunodominant CD8+ CTL epitope (11) that is cross-reactive to the same VP2 epitope of TMEV (5), although VP2 epitope-immunized C57BL/6 mice were not fully protected from subsequent lethal Mengo virus challenge.

The present study is a direct extension of our earlier observation (29) that vMC24-specific CD4+ T cells are capable of adoptively transferring immune protection against lethal EMCV challenge in the absence of prophylactic levels of serum-neutralizing antibodies. Using MHC class II-deficient mice that lack CD4+ T cells and are incapable of T-cell-dependent humoral responses (15), we obtained evidence demonstrating CD8+ T cell-dependent protection against lethal EMCV infection in the absence of serum-neutralizing antibodies.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice.

Healthy immunocompetent C57BL/6 and β2m−/− mice were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, Maine). MHC class II-deficient RHAβ−/− mice were kindly provided by W. P. Weidanz (University of Wisconsin, Madison). β2m−/− and RHAβ−/− mice were on a mixed 129 (H-2b) and B6 (H-2b) genetic background. All strains of mice were used between the ages of 6 and 12 weeks.

Virus stocks.

Cardioviruses EMCV strain Rueckert and vMC24 [attenuated Mengo virus strain partially truncated in the 5′-noncoding-region poly(C) tract; referred to as pM16 in earlier publications by others (9, 10)] were kindly provided by Ann C. Palmenberg (University of Wisconsin, Madison). Stocks were typically provided at 107 to 1010 PFU/ml of sucrose-purified viral preparations.

Viral inoculation.

Naive mice were inoculated intraperitoneally (i.p.) with a range (102 to 108 PFU) of EMCV or vMC24 in 1.0 ml of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). At ≥2 weeks postinoculation, some vMC24-inoculated mice were lethally challenged i.p. with 104 PFU of EMCV to demonstrate efficacy of immunization. Infected mice that displayed typical cardiovirus disease symptoms, such as ataxia, weight loss, gait abnormalities, and limb paresis or paralysis, and had progressed to a completely immobilized status were considered moribund and were destroyed.

Antibodies.

Hybridomas producing monoclonal antibodies directed against CD4 (TIB 207; rat immunoglobulin G2b and CD8 (TIB 210; rat immunoglobulin G2b) were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection. Pooled ascites fluids from pristane-primed nu/nu BALB/c mice were treated with lipid clearing solution (Clinetics, Tustin, Calif.) according to the manufacturer’s instructions, heat-inactivated, filter sterilized, and stored at −70°C.

Cell culture.

RHAβ−/− splenocytes (vMC24 immune or naive) were pooled and cultured with either live EMCV or vMC24 and human recombinant interleuk-2 IL-2 (Hu-rIL-2; Hoffmann-La Roche Inc., Nutley, N.J.). The culture protocol consisted of two phases, antigen-specific activation resulting in up-regulated IL-2 receptor expression followed by IL-2-dependent expansion of activated cells, as previously described (29). Single-cell suspensions of immune splenocytes were prepared by teasing the organ through a wire-mesh grid in chilled RMPI 1640 without serum, and contaminating erythrocytes were lysed by hypotonic shock. Viable cells were isolated by using Lymphoprep (Nycomed Pharma AS, Oslo, Norway), followed by three washes in PBS. Cells resuspended in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 2% heat-inactivated syngeneic normal mouse serum were cultured at 2.5 × 106 to 5.0 × 106 cells/ml in upright 75-cm2 flasks (Costar 3275; Costar Corp., Cambridge, Mass.) and stimulated with 2.5 × 107 to 5.0 × 107 PFU of live virus (at a multiplicity of infection of 10 PFU per cell). Cultures were incubated at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 for 3 days, followed by a further 4-day incubation with the addition of fetal calf serum (FCS) (10%, final concentration) and Hu-rIL-2 (25 U/ml, final concentration).

Flow cytometric analysis.

Cells were assessed by flow cytometry for expression of murine surface markers. All antibodies were primary fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) or phycoerythrin (PE) conjugates (PharMingen, San Diego, Calif.). The following reagents were used: rat anti-mouse CD4-PE, rat anti-mouse CD8-FITC, hamster anti-mouse T-cell receptor α/β chain-FITC, rat anti-mouse CD25 (IL-2 receptor α chain)-PE, hamster anti-mouse CD69 (very early activation antigen)-PE, rat anti-mouse CD71 (transferrin receptor)-PE, and hamster anti-mouse CTLA-4–PE. Washed cells were resuspended in PBS containing 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) and 0.2% sodium azide (staining buffer). Double-color immunofluorescence staining was performed by incubating 106 cells in individual wells of a 96-well, U-bottom microwell plates (Costar 3799; Costar) with relevant monoclonal antibodies for 45 min on ice. After incubation, cells were washed three times with chilled staining buffer and fixed with 1% paraformaldehyde. Flow cytometric analysis was performed with a FACScan and CELLQuest software (Becton Dickinson). The lymphoid cell population was first gated by physical properties of size (forward scatter) and complexity (side scatter); then 10,000 CD8+-staining cells were gated and analyzed for expression of surface markers.

Passive transfer and lethal EMCV challenge.

Neutralizing serum antibody titers were determined by microneutralization assay and expressed as the reciprocal of the highest dilution affording complete protection of a HeLa cell monolayer against vMC24 of EMCV, depending on the specific viral inoculation (9). Pooled sera from exsanguinated C57BL/6 mice immunized 2 weeks previously with 107 PFU of vMC24 had a titer of 2,048. Recipient mice were injected intravenously with 500 μl of immune sera 24 h prior to i.p. challenge with 104 PFU of EMCV. Neutralizing antibody levels in passive-transfer recipients were determined from serum obtained 4 h prior to EMCV challenge and ranged between 512 and 1,024.

In vitro T-lymphocyte depletion.

Splenocytes (5 × 107/ml) were treated with the appropriate monoclonal antibody (ascites fluid diluted 1:100 with RPMI 1640 containing 0.3% BSA) for 1 h on ice and then incubated in a 1:10 dilution of rabbit complement (Low-Tox-M; Cederlane Laboratories, Hornby, Ontario, Canada) for 1 h at 37°C. Cell viability postdepletion was determined by trypan blue exclusion. Flow cytometric analysis was performed on pre- and postdepletion cells to determine the efficacy of the procedure; one cycle of anti-CD8 plus complement was able to achieve >97% depletion of the CD8+ T-cell subpopulation.

In vivo T-lymphocyte depletion.

T-lymphocyte subsets were depleted in vivo by using antibody therapy (43). Briefly, 1 mg of anti-CD4 (clone GK1.5) or anti-CD8 (clone 2.43) ascites fluid or both was administered i.p. on days −2 and 0. Antibody therapy resulted in ≥98% depletion of specific T-lymphocyte subsets of representative animals from each test group on day 0, as determined by flow cytometric analysis (data not shown). Depleted mice were subsequently lethally challenged with 104 PFU of EMCV i.p. on day 0. Control mice receiving antibody therapy did not exhibit ill effects upon cursory examination.

Preparation of CTL target cells.

MC57 cells resuspended in fresh RPMI 1640–10% FCS were infected with EMCV (10 PFU per cell) 24 h before the CTL assay. Cells were labeled by the addition of 100 μCi of Na51 CrO4 (stock concentration, 1 mCi/ml) and incubated for 90 min at 37°C in 5% CO2. These 51Cr-labeled targets were washed three times with PBS, resuspended in 1.0 ml of medium, and counted. Control target cells were uninfected MC57 cells, labeled in the same manner as the infected targets.

CTL assays.

Following 7 days of culture, viable cells were harvested and used as CTL effectors. Twofold serial dilutions of effector cells were made in triplicate. 51Cr-labeled target cells (104 cells per 0.1 ml) were added to all the wells in 96-well U-bottom microwell plates, resulting in final effector-to-target (E:T) ratios of 200:1, 100:1, 50:1, 25:1, 12.5:1, and 6.25:1. Spontaneous release of radioactivity from labeled cells was obtained by culturing the target cells with medium alone. The maximum release of radioactivity was determined by lysing the target cells with 2% sodium dodecyl sulfate. The plates were spun at 200 × g for 2 min and incubated for 5 h at 37°C in 5% CO2. Following incubation, the plates were centrifuged at 800 × g for 4 min, and 100 μl of culture supernatant was assessed for 51Cr release in a gamma counter (LBK-Wallac 1272 CLINIGAMMA; LBK-Wallac, Turku, Finland). Mean values were calculated for the replicate wells, and the results were expressed as percent killing, calculated as [(experimental counts − spontaneous counts)/(maximum counts − spontaneous counts)] × 100. The mean spontaneous release for virally infected and uninfected controls ranged between 10 and 20% of the maximum radioactive release. In some experiments, effector populations were treated in vitro to deplete them of CD8+ or CD4+ T cells, or complement only, prior to use in CTL assay.

Statistical analysis.

A binomial test was used to compare treatment groups.

RESULTS

MHC class II-deficient mice demonstrate susceptibility to attenuated Mengo virus infection.

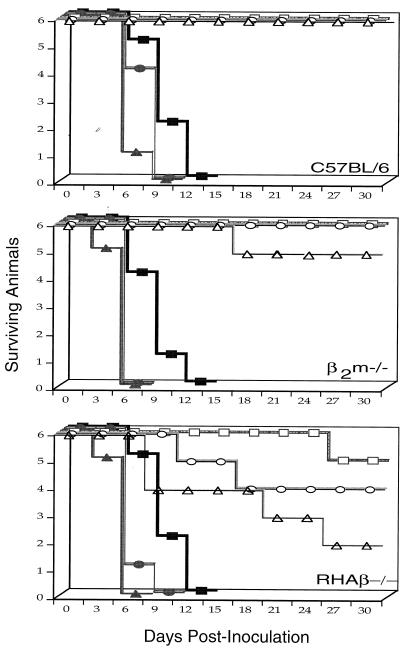

To determine whether vMC24 maintains an attenuated phenotype in the MHC class II-deficient RHAβ−/− mouse strain, naive mice were observed for the development of cardiovirus disease following i.p. injections of various doses of vMC24. As expected, control C57BL/6 mice displayed no adverse effects after infection with vMC24, even at the highest dose (108 PFU) tested (Fig. 1). CD8+ T-cell-deficient β2m−/− mice appeared almost completely refractory to vMC24 infection, with only 2 of 18 mice becoming moribund at the 108-PFU dose (data not shown). Surprisingly, vMC24 induced lethal disease in some RHAβ−/− mice at all doses tested. Four of six mice died at the 108-PFU dose, whereas only one of six became moribund at the 102-PFU dose, a finding which strongly correlates increased vMC24 inoculum to frequency of diseased animals. In some instances, vMC24-infected RHAβ−/− mice displayed typical cardiovirus disease symptoms, such as gait abnormalities and hind limb paralysis, yet recovered and exhibited no further overt symptoms. Therefore, RHAβ−/− mice appear to be susceptible to lethal cardiovirus infection when infected with the attenuated vMC24 Mengo virus. As a positive control, all strains of naive mice infected with EMCV succumbed to lethal cardiovirus disease.

FIG. 1.

Susceptibility of RHAβ−/− mice to vMC24-induced lethal disease. Naive mice (strains C57BL/6, β2m−/−, and RHAβ−/−) were inoculated i.p. with 102 (■), 104 (•), or 108 (▴) PFU of live EMCV or 102 (□), 104 (○), or 108 (▵) PFU of live vMC24 on day 0. Mice were monitored for development of lethal cardiovirus disease during the following 28 days. The data are representative of three experiments.

vMC24-induced viremia.

Although the precise mechanism of attenuation for vMC24 is still undetermined, normal mice clear the virus from the CNS by 2 weeks postinoculation and fail to exhibit cardiovirus disease symptoms (9). Since RHAβ−/− mice consistently demonstrated lethal vMC24-induced cardiovirus disease (Fig. 1), we determined viral titers in the sera and brains of moribund mice. Naive mice received 104 PFU of either vMC24 or EMCV i.p. and were monitored for development of cardiovirus disease symptoms. As a positive control, all strains of mice infected with EMCV developed disease symptoms and progressed to a moribund state by days 5 to 6, coinciding with measurable viral titers in the serum ranging from 4 × 102 to 40 × 102 PFU/ml (Table 1). Naive mice similarly infected with wild-type Mengo virus died on days 5 to 7 (data not shown). Mice of all strains infected with vMC24 that remained clinically healthy apparently resolved the immunizing viremia, as reflected by the absence of detectable virus in their sera. The absence of virus titers in the brains of healthy-appearing vMC24-infected RHAβ−/− mice further substantiated their ability to clear the infection. As expected, vMC24-induced cardiovirus disease in RHAβ−/− mice correlated with serum (range, 0.1 × 102 to 40 × 102 PFU/ml) and brain (range, 6 × 105 to 100 × 105 PFU/g of brain homogenate) virus titers.

TABLE 1.

Virus titers

| Mouse strain | Virusa | Statusb | Titerc

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Serumd | Braine | |||

| C57BL/6 | vMC24 | Healthy | Undetected | Undetected |

| C57BL/6 | EMCV | Moribund | (4–20) × 102 | ND |

| β2m−/− | vMC24 | Healthy | Undetected | ND |

| β2m−/− | EMCV | Moribund | (10−40) × 102 | ND |

| RHAβ−/− | vMC24 | Healthy | Undetected | Undetected |

| RHAβ−/− | vMC24 | Moribund | (1−40) × 102 | (6 − 100) × 105 |

| RHAβ−/− | EMCV | Moribund | (8−40) × 102 | >107 |

Naive mice were inoculated i.p. with 104 PFU of either vMC24 or EMCV.

Animals exhibiting classical cardiovirus disease symptoms and had progressed to a completely immobilized status were termed moribund.

Assay detection limits were 101 to 107 PFU per ml (serum) or g (brain). ND, not determined. n = 6 for each test group.

Mice were bled via the retro-orbital plexus, and virus was titrated by standard plaque assay. Healthy-appearing mice were bled on day 10 postinoculation, whereas diseased mice were bled on reaching moribund status.

Healthy-appearing mice were sacrificed on day 21 postinoculation, whereas diseased mice were sacrificed upon becoming moribund. Brains were homogenized as 10% (wt/vol) suspensions in PBS–0.1% BSA and titered by standard plaque assay.

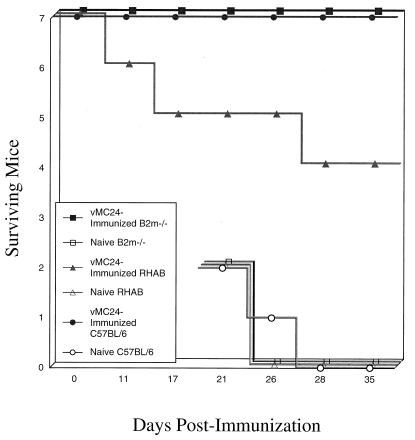

Resistance to lethal EMCV challenge.

Healthy immunocompetent mice immunized with vMC24 have high levels of neutralizing antibody titers and are resistant to lethal EMCV challenge (9, 29). Since RHAβ−/− mice lack CD4+ T-cell-dependent humoral responses (15) yet can resolve vMC24 infection, we examined whether vMC24-immunized RHAβ−/− mice are protected against lethal EMCV challenge. Although some animals succumbed to vMC24-induced cardiovirus disease, the majority of RHAβ−/− mice inoculated with 104 PFU of vMC24 survived (Fig. 1) and appeared to have cleared the virus (Table 1), suggesting that an effective immune response may have been elicited in these mice. Mice were lethally challenged with 104 PFU of EMCV i.p. 21 days postimmunization. All control C57BL/6 and β2m−/− mice survived the vMC24 immunization and were protected from lethal EMCV challenge (Fig. 2), whereas all nonimmunized naive mice died from EMCV-induced cardiovirus disease on days 5 to 7. Again, a few (two of seven) RHAβ−/− mice died as a result of the vMC24 immunization; more interestingly, four of five vMC24-immunized RHAβ−/− mice survived the lethal EMCV challenge. Overall (data not shown), >85% of surviving vMC24-immunized RHAβ−/− mice were protected from lethal challenge, indicating the existence of a protective immune response. Similarly, RHAβ−/− mice inoculated with 104 PFU of vMC24 were protected against lethal wild-type Mengo virus challenge (data not shown).

FIG. 2.

Lethal EMCV challenge of vMC24-immunized RHAβ−/− mice. Naive mice (strains C57BL/6, β2m−/−, and RHAβ−/−) were immunized i.p. with 104 PFU of live vMC24. On day 21 postimmunization, surviving mice were lethally challenged with 104 PFU of EMCV i.p. and monitored for development of lethal cardiovirus disease. Nonimmune controls were similarly challenged on day 21. Data are representative of four experiments.

Serum-neutralizing antibody titers in vMC24-immunized mice.

Given the surprising observation that vMC24-immunized RHAβ−/− mice survived lethal EMCV challenge (Fig. 2), we assayed for the unlikely presence of serum-neutralizing antibodies in vMC24-immunized RHAβ−/− mice. Fourteen days after vMC24 immunization, serum was obtained from each mouse used in the experiments for Fig. 2 and evaluated for neutralizing antibody titers by microneutralization assay. As anticipated, both C57BL/6 and β2m−/− mice possessed protective titers of neutralizing antibodies as a result of the vMC24 immunization (Table 2). Titers ranged from 128 to 512, levels previously shown to be sufficient for protection against lethal EMCV challenge (29). These same mice were lethally challenged with 5 × 104 PFU of EMCV on day 21 postimmunization and reevaluated for serum titers 13 days later. As similarly reported (29), augmented serum-neutralizing titers were observed following EMCV challenge, with an elevation in range from 256 to 1,024.

TABLE 2.

Serum-neutralizing antibody titers

| Mouse strain | Days post- immunizationa | Neutralizing antibody titerb |

|---|---|---|

| C57BL/6 | 14 | (2) 256, (4) 512, (1) 1,024 |

| β2m−/− | 14 | (1) 128, (5) 256, (1) 512 |

| RHAβ−/− | 14 | (7) none detected |

| C57BL/6 | 34c | (1) 256, (3) 512, (3) 1,024 |

| β2m−/− | 34 | (4) 256, (2) 512, (1) 1,024 |

| RHAβ−/− | 34 | (4d) none detected |

104 PFU of vMC24 inoculated i.p. on day 0.

Expressed as reciprocal of the highest dilution affording complete protection of HeLa cell monolayers; assay detection limits, 8 to 1,024. Numbers in parentheses indicate numbers of animals (n = 7 for each test group).

Mice surviving the immunization protocol were lethally challenged with 5 × 104 PFU of EMCV i.p. on day 21 postimmunization.

Two of seven mice died following vMC24 immunization, and one of five immunized mice succumbed to EMCV challenge.

Following vMC24 immunization, surviving RHAβ−/− mice displayed no detectable serum-neutralizing antibody titers, consistent with an earlier report that MHC class II-deficient mice lack an appreciable humoral response against TMEV (31), another cardiovirus. The fact that vMC24-immunized RHAβ−/− mice survived lethal EMCV challenge in the absence of detectable neutralizing antibodies (Table 2) suggests a nonhumoral compensatory protective immune response in these mice.

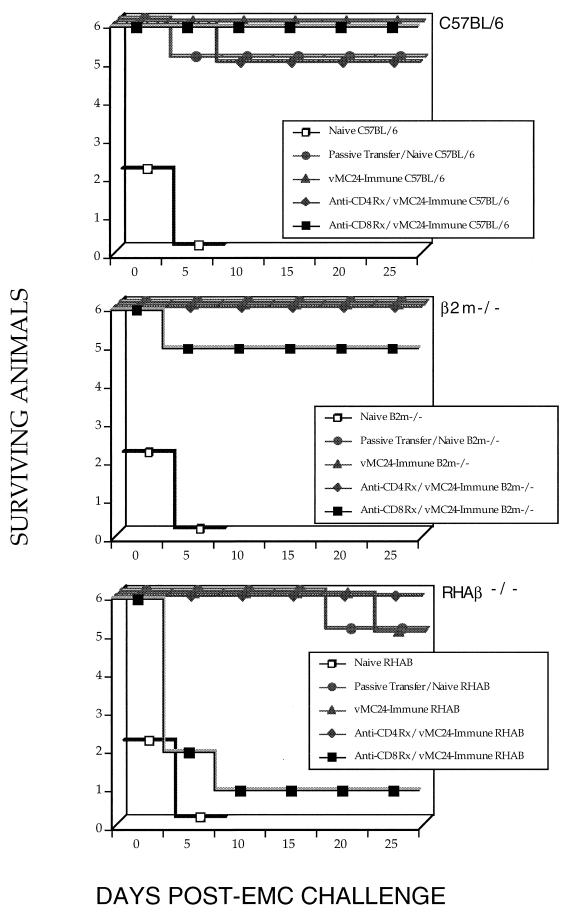

In vivo depletion of CD8+ lymphocytes.

The recent characterization of CD8+ lymphocyte-dependent effector mechanisms present in MHC class II-deficient mice (10, 18, 31, 45, 46), coupled with our finding that vMC24-immunized RHAβ−/− mice were protected in the absence of neutralizing antibodies (Table 2), prompted us to examine the possibility that CMI is involved. All three strains of naive mice that received passive transfer of 500 μl of immune sera were protected from lethal EMCV challenge (Fig. 3). Protection, likely mediated by neutralizing antibodies still present in these mice, remained intact in vMC24-immunized C57BL/6 and β2m−/− mice following in vivo CD4+ or CD8+ T-lymphocyte depletion. vMC24-immunized RHAβ−/− mice were unaffected by anti-CD4+ T-lymphocyte treatment, as these mice possess few or no CD4+ T lymphocytes. Interestingly, depletion of CD8+ T lymphocytes in vMC24-immunized RHAβ−/− mice abrogated protection in five of six mice, clearly demonstrating that CD8+ T lymphocytes were essential in immune protection. All strains of naive mice depleted of either CD4+ or CD8+ T lymphocytes died following EMCV challenge (data not shown).

FIG. 3.

In vivo T-lymphocyte subset depletion. Naive mice (strains C57BL/6, β2m−/−, and RHAβ−/−) were immunized i.p. with 104 PFU of vMC24 and lethally challenged with 104 PFU of EMCV i.p. on day 21 postimmunization. In some instances, immune mice were depleted of CD4+ or CD8+ T lymphocytes by using antibody therapy prior to lethal challenge as described in Materials and Methods. Depletions resulted in >98% reduction of specific T-lymphocyte subpopulations in vivo. Some nonimmune controls received 500 μl of immune serum (titer of >2,048) intravenously 24 h prior to challenge. Data are representative of three experiments.

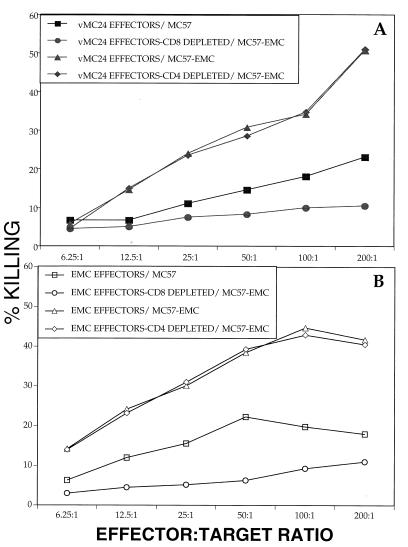

Cytolytic activity of vMC24-immunized RHAβ−/− splenocytes.

We (29) and others (5, 11) have previously demonstrated in vitro CTL activity mediated by CD4+ and CD8+ T-lymphocyte effectors, respectively, using vMC24-immunized splenocytes from immunocompetent mice. Furthermore, a recent report (31) described in vitro CD8+ T-lymphocyte CTL activity in RHAβ−/− mice against a closely associated cardiovirus, TMEV. We therefore determined the cytolytic potential of vMC24-immunized RHAβ−/− splenocytes. RHAβ−/− immune splenocytes were harvested and bulk cultured with live vMC24 or EMCV for 7 days (see Materials and Methods) before use in the CTL assay. Splenic effectors generated from live vMC24 demonstrated 35% specific lysis of EMCV-infected MC57 targets and only 17% killing of noninfected targets at the 100:1 ratio (Fig. 4A). Similarly, EMCV-generated effectors displayed 45 and 19% lysis of infected and noninfected targets, respectively (Fig. 4B). Depletion of CD8+ T lymphocytes prior to the CTL assay markedly reduced the cytolytic activity toward virally infected targets in both the vMC24- and EMCV-generated effector populations, convincingly demonstrating a CD8+ T-lymphocyte-dependent lytic mechanism. As RHAβ−/− mice have no CD4+ T cells, the cytolytic activity by vMC24- and EMCV-generated effectors was minimally affected by treatment for CD4+ T-cell depletion. Similarly, treatment of complement alone did not affect cytolytic activity of either effector group (data not shown).

FIG. 4.

Cytolytic activity of vMC24-immune RHAβ−/− splenocytes. vMC24-immune splenocytes were cultured with live vMC24 (A) or EMCV (B) and used as effector cells at various ratios in CTL assays with 51Cr-labeled EMCV-infected MC57 target cells. In some instances, the population of effector cells was depleted of CD8+ cells prior to CTL assay. Depletions were >97% effective, as determined by flow cytometry. The data are representative of three experiments.

Activation marker expression by CD8+ T lymphocytes.

A recent study (37) reported that primed CD8+ T lymphocytes are hyperreactive to antigen in vitro and, compared with naive cells, differentially express various cell surface activation markers. Therefore, as a corollary of CD8+ T-lymphocyte involvement in protection of vMC24-immunized RHAβ−/− mice, we phenotypically characterized activation marker expression on RHAβ−/− CD8+ T splenocytes during bulk culture with live vMC24.

We used phytohemagglutinin-stimulated CD8+ T cells from naive RHAβ−/− mice as positive controls since mitogenic stimulation of T lymphocytes induces an up-regulated expression of several cell surface activation molecules (3, 19). A comparison of the mean fluorescence intensities (MFI) for CD25 expression indicated that CD8+ T cells from vMC24-immune RHAβ−/− mice (MFI = 100) expressed elevated levels of this cell surface activation marker following stimulation with the cognate immunogen (Table 3) compared to cells from naive RHAβ−/− mice (MFI = 58). Furthermore, 16% of vMC24-immune RHAβ−/− CD8+ T cells expressed high levels of CD25, compared to only 7% of CD8+ T cells from naive RHAβ−/− mice, following in vitro stimulation with virus. Evaluation of CD69, CD71, and CTLA-4 expression revealed similar patterns of MFI and percentage of cells expressing high levels of activation markers between vMC24-immune and naive RHAβ−/− CD8+ T cells. Such observations likely reflect an increased frequency of virus-specific CD8+ T lymphocytes in RHAβ−/− mice following vMC24 immunization, as well as an antigen-dependent hyperreactive response of primed CD8+ T lymphocytes in vitro, resulting in elevated expression of surface activation molecules.

TABLE 3.

Surface expression of activation markers on CD8+ RHAβ−/− splenocytesa

| Test group | MFI of CD8+ cells stained with:

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD69 | CD25 | CD71 | CTLA-4 | |

| PHA stimulatedb | 190 (28c) | 72 (16) | 260 (9) | 55 (14) |

| RHAβ−/− naive | ||||

| +No virus | 76 (5) | 30 (5) | 142 (4) | 40 (6) |

| +vMC24 | 108 (9) | 58 (7) | 168 (5) | 46 (7) |

| RHAβ−/− immune + vMC24 | 124 (15) | 100 (16) | 295 (13) | 61 (16) |

Naive or vMC24-immune RHAβ−/− splenocytes were cultured with live vMC24. Culture samples were taken at day 6 and two-color stained for expression of both CD8-FITC and PE-conjugated activation markers (CD69, CD25, CD71, or CTLA-4). Cells were gated for CD8+-staining cells at the acquisition level, and 10,000 events were collected. The data are representative of one of three experiments.

Naive RHAβ−/− splenocytes were cultured in the presence of phytohemagglutinin (PHA; 5 μg/ml) for 48 h prior to analysis.

Percentage of CD8+ cells expressing the activation marker beyond a specified upper-limit fluorescence intensity gate.

Long-term protection in RHAβ−/− mice.

Shortly after vMC24 immunization, recall response to antigen appears intact and effectual in RHAβ−/− mice. This was demonstrated by survival of lethally challenged vMC24-immune RHAβ−/− mice (Fig. 2), CD8+ T-cell-mediated cytolytic activity against EMCV-infected targets (Fig. 4), and hyperreactive expression of cell surface activation markers by primed CD8+ T cells (Table 3). Studies by others indicated that the ability of RHAβ−/− mice to maintain long-term CD8+ T-cell memory is questionable and appears influenced by the particular viral system being investigated (10, 15, 18, 45, 46). We determined long-term protection of vMC24-immune RHAβ−/− mice by challenging the mice with EMCV 90 days following immunization. vMC24-immune C57BL/6 and MHC class I-deficient β2m−/− mice indicated no diminution in protection when challenged 90 days following immunization (Table 4), whereas 4 of 10 vMC24-immune RHAβ−/− mice died following similar treatment (P > 0.05). Protection in C57BL/6 and β2m−/− mice was likely a reflection of the continued high-titer serum-neutralizing antibodies carried by these vMC24-immune mouse strains (data not shown). The loss of long-term protection by vMC24-immune RHAβ−/− mice was more pronounced in mice that were challenged 14 days after immunization and rechallenged 90 days later. Only 3 of 10 rechallenged vMC24-immune RHAβ−/− mice survived (P > 0.001), while vMC24-immune C57BL/6 and β2m−/− mice similarly rechallenged exhibited no loss of protective memory.

TABLE 4.

Long-term protection

| Mouse strain | Day immunizeda | Survivalb |

|---|---|---|

| C57BL/6 | 14 | 10 |

| 90 | 10 | |

| C57BL/6, rechallengec | 90 | 10 |

| β2m−/− | 14 | 10 |

| 90 | 9 | |

| β2m−/−, rechallenge | 90 | 9 |

| RHAβ−/− | 14 | 9 |

| 90 | 6d | |

| RHAβ−/−, rechallenge | 90 | 3d |

104 PFU of vMC24 inoculated i.p. either 14 or 90 days prior to lethal challenge with 5 × 104 PFU of EMCV i.p.

Number of surviving mice 14 days postchallenge from a group of 10 test animals.

Rechallenge mice were immunized with 104 PFU of vMC24 on day 0 and subsequently lethally challenged with 5 × 104 PFU of EMCV i.p. 14 days postimmunization; 90 days following initial lethal EMCV challenge, mice were challenged again with 5 × 104 PFU of EMCV i.p.

vMC24-immune RHAβ−/− mice succumbed to cardiovirus disease 8 to 14 days postchallenge, whereas all strains of naive mice died by 5 days.

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this study is the first to demonstrate acquired immune protection against a lethal picornavirus infection that is achieved in the absence of serum-neutralizing antibodies. Previously, we described CD4+ T-cell-dependent protection against lethal EMCV challenge in the absence of prophylactic levels of serum-neutralizing antibodies (29). The present study now expands on that earlier study by characterizing CD8+ T-cell-dependent protection without neutralizing antibodies, using an MHC class II knockout mouse model which is deficient in T-cell-dependent humoral responses. Although vMC24 is not entirely attenuated in MHC class II knockout RHAβ−/− mice, vMC24-immunized RHAβ−/− mice are protected against lethal EMCV-induced encephalomyelitis independent of neutralizing antibodies. This acquired resistance is CD8+ T-cell dependent, as in vivo depletion of CD8+ T cells in vMC24-immunized RHAβ−/− mice prior to challenge ablates protection against lethal challenge. vMC24-immune RHAβ−/− splenocytes exhibited CD8+ T-cell-dependent cytolytic activity by lysing EMCV-infected target cells in vitro, which suggests that in vivo protection may be provided, in part, by CD8+ CTL effector functions. Furthermore, correlative evidence of in vivo CD8+ T-cell involvement is demonstrated by the in vitro hyperreactive expression of various cell surface activation markers by vMC24-primed CD8+ T cells to immunogen.

Although the unprecedented loss of attenuated phenotype by vMC24 in RHAβ−/− (Fig. 1) appears viral dose dependent, a similar observation in MHC class II-deficient mice has been reported for the DA strain of TMEV (12). H-2b haplotype mouse strains are normally resistant to TMEV (1, 39), yet 3 of 12 RHAβ−/− (also H-2b) mice exhibited hind limb paresis at the 104-PFU TMEV dose and 10 of 21 died at the 106-PFU dose. We concur with these authors’ conclusion that the lack of CD4+ T-helper functions in RHAβ−/− mice ablates antibody responses and possibly hinders CD8+ CTL functions, both of which may be required for effective TMEV clearance (14, 40). Additionally, a reduced CTL precursor (CTLp) frequency may exist in RHAβ−/− mice, rendering them more susceptible to infection. TMEV-susceptible DBA/2 mice become resistant to persistent TMEV infection following in vivo IL-2 administration that correlates with a three- to fourfold increase in virus-specific CTLp and, too, is viral dose dependent (22). A recent comparison of TMEV-susceptible SJL/J and TMEV-resistant C57BL/6 mice demonstrated kinetically similar serum antibody responses between these strains and attributed susceptibility in the SJL/J strain to reduced CTLp (6). Although our study did not evaluate cardiovirus-specific CTLp in RHAβ−/− mice, it is possible that reduced EMCV-specific CTLp exist, given that MHC class II-deficient mice have a diminished level of influenza virus-specific CD8+ CTLp (46).

Studies by others have demonstrated the existence of CTL activity in Mengo virus-infected mice (17) and identified an immunodominant CD8+ CTL epitope from vMC24-immunized C57BL/6 mice (11) that is cross-reactive to the same VP2 epitope of TMEV (5). In the latter report, the authors stated that VP2 epitope-immunized C57BL/6 mice were not fully protected from subsequent lethal Mengo virus challenge, although a robust VP2 epitope-specific CD8+ CTL response aided clearance of TMEV. The data supporting these conclusions remain unpublished, thus precluding reconciliation with the results of the present study demonstrating CD8+ T cell-dependent immune protection. However, we surmise that the frequency of protective VP2 epitope-specific CD8+ CTLs generated during immunization may be inadequate for protection against the magnitude of that particular lethal challenge. Although Dethlefs et al. (5) have identified the VP2 epitope as immunodominant, lethally challenging mice immunized to a single CTL epitope places a great immunological burden on such epitope-specific CD8+ T cells. In our system, by contrast, vMC24-immune RHAβ−/− mice likely possess a heterogenous population of vMC24-specific CD8+ T-cell effectors capable of thwarting a lethal challenge.

The virus-specific lysis exhibited by RHAβ−/− splenocytes (Fig. 4) is low compared to CTL responses by effectors from immunologically intact mice. We (29) and others (5) have previously demonstrated CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell-dependent lysis, respectively, of virally infected targets in assays using vMC24-primed T-cell effectors from healthy mice. In those instances, >50% specific lysis was achieved at E:T ratios of only ∼20:1. In the present study, vMC24-immune RHAβ−/− splenocytes demonstrated only 30 to 45% specific lysis at the higher E:T ratio of 100:1, clearly indicating a less than optimal in vitro cytolytic capacity of this CD4+ T-cell-deficient animal model. Others have reported impaired CD8+ T-cell functions in CD4+ T-cell-deficient mice. Healthy C57BL/6 mice immunized with lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus (LCMV) exhibited ∼60% specific lysis against LCMV-infected targets, whereas CD4 knockout mice similarly treated displayed only ∼27% specific lysis at the same E:T ratio (48). Thompsen et al. (45) demonstrated >70% specific lysis by LCMV-immunized C57BL/6 splenocytes at an E:T ratio of 80:1, while splenocytes from LCMV-immunized MHC class II-deficient mice displayed only 12% specific lysis at the same high ratio. Furthermore, CNS-infiltrating lymphocytes from TMEV-infected MHC class II-deficient mice showed only a ∼23% specific lysis at an E:T ratio of 100:1 (31). The diminished cytolytic function observed in CD4+ T-cell-deficient mice may result from an absence of CD4+ T cells, as depletion of CD4+ T cells in healthy C57BL/6 mice results in a similar reduction of cytolytic capacity (45, 48).

Protection against lethal EMCV challenge in vMC24-immune RHAβ−/− mice is CD8+ T-cell dependent (Fig. 3) and likely mediated, in part, by vMC24-specific CD8+ CTL effectors (Fig. 4 and Table 3). The necessity of MHC class II-restricted CD4+ T-cell involvement in generating effector CTLs has long been the subject of debate, fueled in part by observations that both CD4+ T-cell-dependent and -independent induction of virus-specific CD8+ CTL responses occur, depending on the particular viral infection studied. Indeed, CD8+ CTL responses to several viral infections have been reported for MHC class II-deficient mice (4, 18, 31, 45, 46), clearly demonstrating generation of CD8+ CTL effectors independent of CD4+ T-cell helper function. The ability to potentiate a CD8+ CTL effector response in MHC class II-deficient mice appears to be antigen concentration dependent (38), such that high concentrations of antigen, possibly analogous to those observed during acute viral infection or vMC24 immunization, proceed in a CD4+ T-cell-independent manner.

Mitogen- or antigen-activated lymphocytes express high levels of cell surface activation molecules, such as CD69, CD25, and CD71, which are minimally expressed, or even absent, on resting lymphocytes (3, 19, 33). Memory CD8+ T cells are hyperreactive in that they differentially express activation markers compared to naive CD8+ T cells following reactivation in vitro by antigen (37) and serve as a standard for assessing potential in vivo CD8+ T-cell involvement. A comparison between primed and naive RHAβ−/− CD8+ T cells of CD69, CD25, CD71, and CTLA-4 expression (Table 3) clearly indicated the presence of virus-specific CD8+ T memory cells in vMC24-immune RHAβ−/− mice. Primed RHAβ−/− CD8+ T cells displayed elevated expression of activation markers, as demonstrated by increased MFI, when cultured with vMC24. Additionally, a similar comparison of the percentage of RHAβ−/− CD8+ T cells expressing high levels of activation markers showed that nearly twice as many primed RHAβ−/− CD8+ T cells were high-level expressors as were naive RHAβ−/− CD8+ T cells (percent primed/percent naive, 15/9 for CD69, 16/7 for CD25, 13/5 for CD71, and 16/7 for CTLA-4). Stimulation by cognate immunogen, compared with EMCV (data not shown), consistently resulted in a greater percentage of vMC24-primed CD8+ splenocytes expressing surface activation markers. This disparity may be attributed to a <100% cross-reactivity of CD8+ T-cell epitopes between these viruses, given that they exhibit only ∼91% amino acid identity (36), or possibly a more rapid reduction of potential reactivating antigen-presenting cells by the highly virulent and cytopathic EMCV.

MHC class II-deficient mice appear to have intact CD8+ T-cell responses during the initial acute phase of viral infections. Yet, when assessed months later, these mice exhibited immunological memory impairment, such as reduced CTLp frequencies, diminished in vitro CTL activity, viral recrudescence, and/or loss of in vivo protection (4, 45, 46). In our study vMC24-immune RHAβ−/− mice demonstrated CD8+ T-cell-dependent protection against lethal EMCV infection when challenged shortly after resolution of primary (immunizing) acute infection. When rechallenged with EMCV 3 months later, the vast majority (7 of 10) of these same vMC24-immune RHAβ mice died from lethal cardiovirus disease, indicating a loss of immunological protection. This abatement in protection over time may have a CD4+ T-cell-dependent component, as B-cell-deficient mice, possessing CD8+ and CD4+ T cells, similarly treated exhibited no loss of vMC24-induced long-term protection (unpublished data). Likewise, others showed that CD4+ T-cell-deficient mice exhibited a similar time-dependent reduction in CTL memory that correlated with a loss in resistance to subsequent LCMV challenge (48). Alternatively, some (45) have suggested that LCMV-specific CTL exhaustion, rather than a lack of CD4+ T cells, is responsible for loss in CTL activity and viremic recrudescence in RHAβ−/− mice.

Noncytopathic viruses require CTL-mediated resolution of infection, whereas cytopathic viruses are eliminated with antiviral cytokines and antibodies (20, 50). Therefore, the role of CD8+ T memory cells in the elimination of cytopathic viruses, such as EMCV and Mengo virus, is unclear and precludes using CTLp frequency as the primary parameter to determine CD8+ T-cell memory as suggested by others (8, 18). Therefore, in the absence of serum-neutralizing antibodies, the task of initiating and affecting a protective CD8+ CTL memory response against cytopathic EMCV challenge would seem insurmountable. Although we demonstrated RHAβ−/− CD8+ T-cell-dependent cytolysis, it is possible that in addition to CD8+ CTL effectors, vMC24-immune RHAβ−/− CD8+ T cells contribute to protection by inducing an antiviral state through liberation of cytokines. Gamma interferon (IFN-γ) is a potent agent against EMCV and has demonstrated in vivo protective effects against infection in mice (21, 34). MHC class II-deficient mice are capable of making IFN-γ in response to viral infection (18, 46), and since CD8+ T cells often secrete Th1-like and Th2-like cytokines (24), protection in vMC24-immune RHAβ−/− mice may be due in part to IFN-γ generation. The involvement of IFN-γ or other antiviral cytokines in contribution to protection in vMC24-immune RHAβ−/− mice remains to be investigated.

In summary, we present evidence of antibody-independent protection against lethal picornavirus infection. MHC class II-deficient RHAβ−/− mice immunized with an attenuated strain of Mengo virus, vMC24, demonstrate CD8+ T-cell-dependent protection against lethal EMCV infection in the absence of serum-neutralizing antibodies. Furthermore, vMC24-immune RHAβ−/− CD8+ T cells exhibited in vitro cytolytic activity toward virally infected target and hyperreactive expression of cell surface activation markers. Although protection appears to wane with time, this T-cell-dependent protection clearly suggests amendment of the long-standing picornavirus paradigm of antibody-mediated protection to include additional mechanisms of immune protection. Such antibody-independent protection warrants further investigation of uncharacterized immune mechanisms invoked during a picornavirus infection.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank A. C. Palmenberg for the generous gift of vMC24, Marchel Goldsby-Hill for invaluable technical support and helpful suggestions during the project, and D. Mathis for allowing us the use of MHC class II-deficient RHAβ−/− mice.

This work was supported by the College of Agricultural and Life Sciences, USDA National Need Fellowship Program 90-38420-5254, and DOD DAAH 04-96-1-0126.

Footnotes

Dedicated to the memory of H. Hotchkiss, E. Zehm, and R. Neal.

REFERENCES

- 1.Azoulay A, Brahic M, Bureau J F. FVB mice transgenic for the H-2Db gene become resistant to persistent infection by Theiler’s virus. J Virol. 1994;68:4049–4052. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.6.4049-4052.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bogaerts W J, van der Oord D. Immunization of mice against encephalomyocarditis virus. II. Intraperitoneal and respiratory immunization with ultraviolet-inactivated vaccine: effect of Bordetella pertussis extract on the immune response. Infect Immun. 1972;6:513–517. doi: 10.1128/iai.6.4.513-517.1972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Caruso A, Licenziati S, Corulli M, Canaris A D, De Francesco M A, Fiorentini S, Peroni L, Fallacara F, Dima F, Balsari A, Turano A. Flow cytometric analysis of activation markers on stimulated T cells and their correlation with cell proliferation. Cytometry. 1997;27:71–76. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0320(19970101)27:1<71::aid-cyto9>3.0.co;2-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Christensen J P, Marker O, Thomsen A R. The role of CD4+ T cells in cell-mediated immunity to LCMV: studies in MHC class I and class II deficient mice. Scand J Immunol. 1994;40:373–382. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.1994.tb03477.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dethlefs S, Escriou N, Brahic M, van der Werf S, Larsson-Sciard E. Theiler’s virus and Mengo virus induce cross-reactive cytotoxic T lymphocytes restricted to the same immunodominant VP2 epitope in C57BL/6 mice. J Virol. 1997;71:5361–5365. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.7.5361-5365.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dethlefs S, Brahic M, Larsson-Sciard E. An early, abundant cytotoxic T-lymphocyte response against Theiler’s virus is critical for preventing viral persistence. J Virol. 1997;71:8875–8878. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.11.8875-8878.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dick G W A. Mengoencephalomyelitis virus: pathogenicity for animals and physical properties. Br J Exp Pathol. 1948;29:559–577. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Doherty P C, Hou S, Tripp R A. CD8+ T-cell memory to viruses. Curr Opin Immunol. 1994;6:545–552. doi: 10.1016/0952-7915(94)90139-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Duke G M, Osorio J E, Palmenberg A C. Attenuation of Mengo virus through genetic engineering of 5′ noncoding poly(C) tract. Nature. 1990;343:474–476. doi: 10.1038/343474a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Duke G M, Palmenberg A C. Cloning and synthesis of infectious cardiovirus RNAs containing short, discrete poly(C) tracts. J Virol. 1989;63:1822–1826. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.4.1822-1826.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Escriou N, Leclerc C, Gerbaud S, Girard M, van der Werf S. Cytotoxic T cell response to Mengo virus in mice: effector cell phenotype and target proteins. J Gen Virol. 1995;76:1999–2007. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-76-8-1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fiette L, Brahic M, Pena-Rossi C. Infection of class II-deficient mice by the DA strain of Theiler’s virus. J Virol. 1996;70:4811–4815. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.7.4811-4815.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fiette L, Aubert C, Brahic M, Pena-Rossi C. Theiler’s virus infection of β2-microglobulin-deficient mice. J Virol. 1993;67:589–592. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.1.589-592.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fujinami R S, Rosenthal A, Lampert P W, Zurbriggen A, Yamada M. Survival of athymic (nu/nu) mice after Theiler’s murine encephalomyelitis virus infection by passive administration of neutralizing monoclonal antibody. J Virol. 1989;63:2081–2087. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.5.2081-2087.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grusby M J, Glimcher L H. Immune responses in MHC class II-deficient mice. Annu Rev Immunol. 1995;13:417–435. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.13.040195.002221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guthke R, Veckenstedt A, Guttner J, Stracke R, Bergter F. Dynamic model of the pathogenesis of Mengo virus infection in mice. Acta Virol (Praha) 1987;31:307–320. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hassin D, Fixler R, Bank H, Klein A S, Hasin Y. Cytotoxic T lymphocytes and natural killer cell activity in the course of mengo virus infection of mice. Immunology. 1985;56:701–705. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hou S, Hyland L, Doherty P C. Host responses to Sendai virus in mice lacking class II major histocompatibility complex glycoproteins. J Virol. 1995;69:1429–1434. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.3.1429-1434.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Johannisson A, Thuvander A, Gadhasson I L. Activation markers and cell proliferation as indicators of toxicity: a flow cytometric approach. Cell Biol Toxicol. 1995;11:355–366. doi: 10.1007/BF01305907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kagi D, Hengartner H. Different roles for cytotoxic T cells in the control of infections with cytopathic versus noncytopathic viruses. Curr Opin Immunol. 1996;8:472–477. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(96)80033-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kimura T, Nakayama K, Penninger J, Kitagawa M, Harada H, Matsuyama T, Tanaka N, Kamijo R, Vilcek J, Mak T W. Involvement of the IRF-1 transcription factor in antiviral responses to interferons. Science. 1994;264:1921–1924. doi: 10.1126/science.8009222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Larsson-Sciard E, Dethlefs S, Brahic M. In vivo administration on interleukin-2 protects susceptible mice from Theiler’s virus persistence. J Virol. 1997;71:797–799. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.1.797-799.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Minor P D. Structure of picornavirus coat proteins and their antigenicity. In: Rowlands D J, Mayo M A, Mahy B W J, editors. The molecular biology of the positive strand RNA viruses. Orlando, Fla: Academic Press Inc.; 1987. pp. 259–280. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mosmann T R, Sad S. The expanding universe of T-cell subsets: Th1, Th2 and more. Immunol Today. 1996;17:138–146. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(96)80606-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mosser A G, Leippe D M, Rueckert R R. Neutralization of picornaviruses: support for the pentamer bridging hypothesis. In: Semler B L, Ehrenfeld E, editors. Molecular aspects of picornavirus infection and detection. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1989. pp. 155–168. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Muir S, Weintraub J P, Hogle J, Bittle J L. Neutralizing antibody to Mengo virus, induced by synthetic peptides. J Gen Virol. 1991;72:1087–1092. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-72-5-1087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Murdin A D, Murry M G, Wimmer E. Novel approaches to picornavirus vaccines. In: Mizrahi A, editor. Viral vaccines. New York, N.Y: Wiley-Liss, Inc.; 1990. pp. 301–323. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Murphy B R, Chanock R M. Immunization against viruses. In: Fields B N, Knipe D M, Howley P M, Chanock R M, Melnick J L, Monath T P, Roizman B, Straus S E, editors. Fields virology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Lippincott-Raven Press; 1996. pp. 467–498. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Neal Z C, Splitter G A. Picornavirus-specific CD4+ T lymphocytes possessing cytolytic activity confer protection in the absence of prophylactic antibodies. J Virol. 1995;69:4914–4923. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.8.4914-4923.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nicholson S M, Del Canto M C, Miller S D, Melvold R W. Adoptively transferred CD8+ T lymphocytes provide protection against TMEV-induced demyelinating disease in BALB/c mice. J Immunol. 1996;156:1276–1283. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Njenga M K, Pavelko K D, Baisch J, Lin X, David C, Leibowitz J, Rodriguez M. Theiler’s virus persistence and demyelination in major histocompatibility complex II-deficient mice. J Virol. 1996;70:1729–1737. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.3.1729-1737.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nomoto A, Iizuka N, Kohara M, Arita M. Strategy for construction of live picornavirus vaccines. Vaccine. 1988;6:134–137. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(88)80015-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.O’Gorman M R, Corrochano V, Poon R Y. Beyond tritiated thymidine: flow cytometric assays for the evaluation of lymphocyte activation/proliferation. Clin Immunol News. 1996;16:164–172. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ozmen L, Aguet M, Trinchiieri G, Garotta G. The in vivo antiviral activity of interleukin-12 is mediated by gamma interferon. J Virol. 1995;69:8147–8150. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.12.8147-8150.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Palmenberg A C. Sequence alignments of picornaviral capsid proteins. In: Semler B L, Ehrenfeld E, editors. Molecular aspects of picornavirus infection and detection. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1989. pp. 211–242. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Palmenberg, A. C. Personal communication.

- 37.Pihlgren M, Dubois P M, Tomkowiak M, Sjogren T, Marvel J. Resting memory CD8+ T cells are hyperreactive to antigenic challenge in vitro. J Exp Med. 1996;184:2141–2151. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.6.2141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rock K L, Clark K. Analysis of the role of MHC class II presentation in the stimulation of cytotoxic T lymphocytes by antigens targeted into the exogenous antigen-MHC class I pathway. J Immunol. 1996;156:3721–3726. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rodriguez M, David C S. Demyelination induced by Theiler’s virus: influence of the H-2 haplotype. J Immunol. 1985;135:2145–2148. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rodriguez M, Dunkel A J, Thiemann R L, Leibowitz J, Zijlstra M, Jaenisch R. Abrogation or resistance to Theiler’s virus-induced demyelination in H-2b mice deficient in β2-microglobulin. J Immunol. 1993;151:266–276. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rossi C P, Cash E, Aubert C, Coutinho A. Role of the humoral immune response in resistance to Theiler’s virus infection. J Virol. 1991;65:3895–3899. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.7.3895-3899.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rueckert R R. Picornaviridae: the viruses and their replication. In: Fields B N, Knipe D M, Howley P M, Chanock R M, Melnick J L, Monath T P, Roizman B, Straus S E, editors. Fields virology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Lippincott-Raven Press; 1996. pp. 609–654. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Smith D M, Stuart F P, Wemhoff G A, Quintans J, Fitch F W. Cellular pathways for rejection of class-I-MHC-disparate skin and tumor allografts. Transplantation. 1987;45:168–175. doi: 10.1097/00007890-198801000-00036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sriram S, Topham D J, Huang S K, Rodriguez M. Treatment of encephalomyocarditis virus-induced central nervous system demyelination with monoclonal anti-T-cell antibodies. J Virol. 1989;63:4242–4248. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.10.4242-4248.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Thomsen A R, Johansen J, Marker O, Christensen J P. Exhaustion of CTL memory and recrudescence of viremia in lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus-infected MHC class II-deficient mice and B cell-deficient mice. J Immunol. 1996;157:3074–3080. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tripp R A, Sarawar S R, Doherty P C. Characteristics of influenza virus-specific CD8+ T cell response in mice homozygous for disruption of the H-2IAb gene. J Immunol. 1995;155:2955–2959. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Veckenstedt A. Pathogenicity of Mengo virus to mice. I. Virological studies. Acta Virol (Praha) 1974;18:501–507. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.von Herrath M G, Yokoyama M, Dockter J, Oldstone M B A, Whitton J L. CD4-deficient mice have reduced levels of memory cytotoxic T lymphocytes after immunization and show diminished resistance to subsequent virus challenge. J Virol. 1996;70:1072–1079. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.2.1072-1079.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Welsh C J, Tonks P, Nash A A, Blakemore W F. The effect of L3T4 T cell depletion on the pathogenesis of Theiler’s murine encephalomyelitis virus infection in CBA mice. J Gen Virol. 1987;68:1659–1667. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-68-6-1659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zinkernagel R M. Immunology taught by viruses. Science. 1996;271:173–178. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5246.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]