Abstract

The field of synthetic nucleic acids with novel backbone structures [xenobiotic nucleic acids (XNAs)] has flourished due to the increased importance of XNA antisense oligonucleotides and aptamers in medicine, as well as the development of XNA processing enzymes and new XNA genetic materials. Molecular modeling on XNA structures can accelerate rational design in the field of XNAs as it contributes in understanding and predicting how changes in the sugar–phosphate backbone impact on the complementation properties of the nucleic acids. To support the development of novel XNA polymers, we present a first-in-class open-source program (Ducque) to build duplexes of nucleic acid analogs with customizable chemistry. A detailed procedure is described to extend the Ducque library with new user-defined XNA fragments using quantum mechanics (QM) and to generate QM-based force field parameters for molecular dynamics simulations within standard packages such as AMBER. The tool was used within a molecular modeling workflow to accurately reproduce a selection of experimental structures for nucleic acid duplexes with ribose-based as well as non-ribose-based nucleosides. Additionally, it was challenged to build duplexes of morpholino nucleic acids bound to complementary RNA sequences.

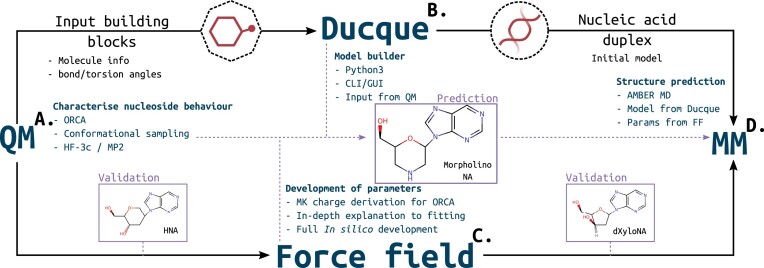

Graphical Abstract

Graphical Abstract.

Introduction

The potential of nucleic acid therapeutics was recognized >50 years ago, but nucleases that hydrolyze phosphodiester linkages in oligonucleotide (ON) strands represented one of the hurdles that significantly slowed down their rise in the therapeutic field (1). Analogs carrying modifications in the backbone and nucleobase [xenobiotic nucleic acids, XNAs (2)] accelerated development of nucleic acid therapeutics in the mid-1980s, as they allowed modulation of catalytic degradation of ONs and/or increased affinity for the selected target. Several XNA chemistries were used for various clinical applications, of which some have reached the market (3). While XNAs were initially designed to modulate RNA activity upon hybridization, some XNA alterations have also been developed for applications such as therapeutic aptamers and an alternative genetic system in synthetic biology. This has led to the engineering of enzymes able to process such ON strands, in order to promote XNA ON manipulation methodologies to a higher level of efficiency, for both the researcher and the cell (4,5).

Conformational pre-organization of sugar moieties in the XNA backbone is a key feature for their capacity to bind to native nucleotides. Chemical modifications such as pyranose units (6) and locked nucleic acids (LNAs) (7) freeze the sugar moiety in the nucleic acid backbone and thus offer the ultimate control of conformational pre-organization and fix their recognition potential for either DNA or RNA. The xylose-based chemistries, on the other hand, avoid hybridization with native nucleotides (8). Nucleobase alterations can provide hybridization stability, which benefits duplex formation, or extends binding potential, broadening the range of possible aptamer–target interactions. Recently, these XNAs have been successfully employed in CRISPR–Cas9 research, using the thG modification (9).

The morpholino nucleic acids (MNAs) are a prime example of highly modified nucleic acids in antisense oligonucleotide (ASO) research and therapies (10,11). Their presumed mechanism of action is to sterically block RNA splicing or translation, by binding to their RNA complement. Pre-clinical studies in zebrafish have popularized the use of such gene knockdown mechanisms with MNA ONs (12). MNAs are commonly used in the treatment for Duchenne’s muscular dystrophy, where binding to the specific exon 51 sequence leads to trimming of the dystrophin protein. In short, the binding of an ASO to its target sequence results in cancelling the propagation of that exon 51 RNA sequence into a peptide strand, thereby halting the translation into a full-fledged protein. This is in contrast to the endogenous RNA degradation exploited by other XNA chemistries for ASO and silencing RNA (siRNA) purposes (13–15) catalyzed by the RNase H enzyme or RISC complex, that break RNA strands upon hydridization with complementary DNA and RNA strands, respectively. In such a mechanism, the XNA::RNA duplex must be recognized by the processing machinery through similarity to the natural substrate (16). Experimental structures of a range of XNA chemistries in homoduplexes and bound to a complementary nucleic acid sequence proved useful in understanding their biophysical and biological properties (5).

Molecular modeling of XNA::RNA duplexes can predict possible XNA applications and guide the design of XNA and XNA processing enzymes (17). Model building of nucleic acids was facilitated in the mid-1990s thanks to the release of the Nucleic Acid Builder (NAB) software and its domain-specific language (18,19). This was followed by many implementations of the NAB language in a variety of wrappers and servers to allow model building for DNA and RNA. The proto-Nucleic Acid Builder has taken a small step towards XNA building by including a set of modifications known to build into mainly A-type structures (20). It employs parameters from experimentally derived structures, using the convention of 3DNA (21) of basis reference frames, which differ slightly from the definition of Curves+ (22). It also makes a good attempt at minimizing duplex models with force fields (FFs) that were developed for small molecule minimization and evaluation. The claimed predictions simply build along a set of given vectors from data gathered from wet lab experiments. Consequently, such building schemes are not applicable for many unsolved and under-researched chemical structures.

Because of the amount of new chemistries developed for many different applications (23,24), an urgent need arose to design a platform that can handle the influx of existing XNAs and modifications that have yet to be developed. With this in mind, we developed the Ducque software from scratch, independent from the approach of the traditional NAB. It comes with a user-customizable library for linker and sugar moieties to build XNA models with a virtually unlimited set of chemistries on the backbone, with a future outlook to customizing nucleobase modifications. This approach easily allows all models exemplified in Anosova et al. (25) to be built, regardless of complexity.

The Ducque model builder is part of an elaborate workflow to implement new chemistries for accurate molecular dynamics (MD) simulations (Figure 1). The model builder also boasts a neat graphic user interface (GUI) that makes the flow of importing new building blocks, randomizing and building structures smooth and concise, by allowing access to the various modules in a chained fashion. A potential energy surface (PES) describes the nucleoside’s behavior along its puckering profile. These data feed directly into Ducque and the creation of a suitable FF, respectively. Additionally, an AMBER-specific implementation of the parametrization scheme was developed for the ORCA package. While Ducque is used to build an initial model, the FF is essential for the final molecular mechanics (MM) stage that provides an accurate structure. Here, we demonstrate Ducque against natural nucleic acids using NAB as our benchmark and show its functionality across a range of well-characterized XNAs. The workflow was validated on hexitol nucleic acid (HNA) and deoxy-xylose nucleic acid (dXyNA), and challenged on the RNA::MNA duplex, a heteroduplex with clinical relevance for which no experimental structure is available to date.

Figure 1.

Proposed workflow. (A) QM approach to perform conformational sampling to describe the torsional behavior. (B) The Ducque model builder receives input from the computed PES to use curated conformers as building block to generate duplex models. (C) From the PES, one can derive a FF by virtue of the predicted behavior. A charge derivation scheme has been implemented for ORCA. Curated conformers are to be used to derive torsional parameters for the FF. (D) Combining the products of (B), an (X)NA molecular model, and (C), a representative FF, we can predict the molecular structure of an XNA model duplex through the use of an MM package, which can be used for antisense design, (X)NA enzyme engineering and more. This project workflow has been validated on HNA and dXyNA, and has been applied to predict the RNA::MNA heteroduplex.

Materials and methods

Characterization of the nucleosides through quantum mechanics

The conformational sampling method has been previously reported and applied on DNA, RNA, HNA and dXyNA in Mattelaer et al. (26). For MNA, the Cremer–Pople (CP) coordinates can be reverse-engineered to Strauss–Pickett (SP) improper dihedrals (github.com/Marcello-Sega/sugar-puckering), by generating equidistributed coordinate points on the surface of a sphere (27). The generated spherical coordinates (r, θ, ϕ) are converted to local elevation (zj) from a mean plane per respective atom (28), by assuming bond lengths and angles, which positions the atoms in the ring in Cartesian space. From the atomic coordinates, the improper dihedrals (α1, α2, α3) can be calculated for (29). Graphical representations of these formalisms have been added (Supplementary Figures S3 and S4). These improper dihedrals are used as restraints for the ORCA software (v. 5.0.2) (30). Several backbone torsion angles were restrained as follows: β (180.1°), γ (60.1°), ϵ (180.1°), χ (193.9°) (26). First, a lightweight semi-empirical HF-3c (Hartree–Fock) geometry optimization is performed to relax the respective conformations after imposing the restraints. Afterwards, a single point energy (SPE) evaluation, through Møller–Plesset second-order perturbation theory (MP2), is performed to evaluate the potential of the respective conformers. The specific accompagnying basis set for MP2 is 6-311++G(2df,2p) with the def2-qzvpp/C basis as an auxiliary basis set for the RI approximation and the def2/JK auxiliary basis set for the RI approximation of Coulomb and exchange integrals in the HF step (26). A total of 630 conformers were sampled for each morpholino nucleoside. The geography library, cartopy (≤ python3.6), is employed to make a two-dimensional projection of the IR3 surface of the conformational sphere of HNA and MNA from which we sampled (Supplementary Figure S5). The Mollweide projection is used, together with a PlateCarree transformation. The SciPy Radial basis function (Rbf) is used to interpolate the values to generate the PES. Quantum mechanics (QM) calculations were performed on a Ryzen ThreadRipper 3970, with a memory capacity of 32 Gb RAM. The standard MNA has been altered to a methyl-capped O6′ and N3′ variant before sampling the conformations, for reasons detailed in the Results and Discussion.

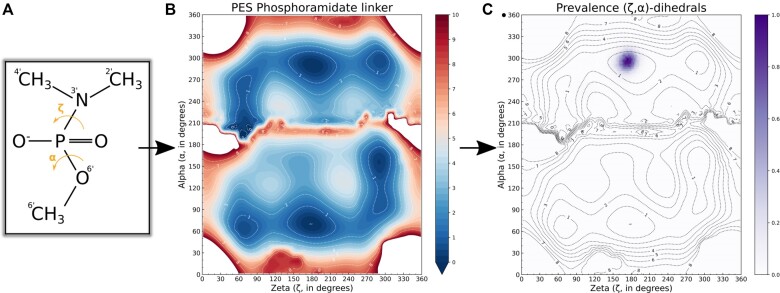

The linker moiety, N,N-dimethyl-O-methylaminophosphoroamidate, has been subjected to a conformational sampling following the same methodology, but instead of varying endocyclic torsion angles, the (ζ, α) dihedral dyad was varied from 0° to 360° in steps of 10° along both axes (Figure 3), for a total of 1369 conformers.

Figure 3.

Validation of the parametrized backbone N,N-dimethyl-O-methylaminophosphoroamidate linker; PES and torsional prevalence during the simulation. (A) The (ζ, α) dihedral dyad over which we extracted all conformers of the N,N-dimethyl-O-methylaminophosphoroamidate linker. (B) PES of the conformational landschape of the N,N-dimethyl-O-methylaminophosphoroamidate linker. (C) The prevalence of the (ζ, α) phosphoroamidate linker backbone, extracted from the last 50 ns of the 200 ns simulation. Data were extracted from the simulation and normalized according to the prevalence count of the dihedral dyad.

The Ducque model builder for (X)NA structures

Ducque is written in Python3 and uses only built-in modules as well as NumPy- (31) based modules (NumPy, SciPy). Ducque is functional both in the Commandline Interface (CLI) and with a GUI (Tkinter). It is a free and open-source software (github.com/jrihon/Ducque), under the MIT license.

Ducque uses a mechanical building method that functions solely on the given nucleoside conformers and backbone parameters of the respective nucleotides which it builds into a strand, meaning it only takes into account the input bond angles and dihedrals. Array rotation in IR3 is supported by quaternion mathematics.

Ducque’s core functionality is extrapolation of the backbone dihedral by requiring only torsion and angle values. To position an atom in IR3, there is only one location that satisfies both the given angle and dihedral. With this process, and an associated fitting of the following linker and nucleoside, the leading strand is built (Supplementary Figure S1). To build to complementary sequence, a fitting of the complementary strand’s nucleobase to the leading strand’s nucleobase is performed, by positioning the complementary nucleobase onto the plane of its base pair and shifting it into the desired hydrogen-bonding position (Supplementary Figure S2). An added fitting of the backbone with neighboring residues resolves most, if not all, clashes. Any remaining clashes are easily resolved through minimization in the next stage of MD, with the correct FF.

Extending the XNA library of Ducque

Ducque allows the user to implement a custom repository of new chemistries, which function as building blocks for the virtual duplexes. This module requires the additional information on the input angles and the pdb format nucleoside itself. Furthermore, one can generate randomized sequences through the randomization module, or manually customize sequences, giving the user the freedom of choice when designing a duplex, e.g. multiple chemistries. Lastly, the xyz format files, generated during conformational sampling by ORCA, can be converted to a pdb format by Ducque. This implies batch conversion through Ducque as well.

For the extension of the Ducque library with new inputs, a pdb input file of the new nucleoside must be provided by the user. It is converted to the json format (--transmute), which requires parameters such as residue name, backbone angles and dihedrals to generate a suitable json input file. The xyz format files, generated during conformational sampling to characterize nucleosides (ORCA output), can be converted to pdb format files by Ducque (--xyz_pdb) and subsequently used to supply to the user library. One can generate strands with randomized sequences for a specific XNA chemistry through the randomization module (--randomise), or manually customize sequences. The latter option allows the design of a nucleobase sequence as well as the nucleic acid backbone on a residue-specific level, giving freedom of choice for duplex design with multiple chemistries in the (customized) library. The randomization functionality was used to generate a multitude of different models for DNA::DNA, DNA::RNA, RNA::RNA, dXyNA::dXyNA, RNA::HNA and finally RNA::MNA. A sequence was specified manually to generate double-Drew Dickerson dodecamer (double-DDD) structures. Nucleic acid duplex models were built (--build) from the randomized/DDD sequences and were subjected to MD.

The respective nucleobases were flattened using the HF-3c level geometry optimization, with the atoms in and on the sugar restrained in Cartesian space and the χ dihedral restrained at its current position. The improper dihedral for purines (C1′, C8, N9, C4) and pyrimidines (C1′, C6, N1, C2) is also restrained to –179.5° to ensure a plane as flat as the standard nucleobases provided with NAB to satisfy the planarity assumptions in the rotations. For benchmarking the build quality of the structures, Python scripting (for NAB) and Ducque’s randomization module were used to generate 10 RNA and DNA homoduplexes of a randomized sequence of 12 bp, respectively. These were compared with duplexes generated by the NAB language (Supplementary Figure S9; Supplementary Table S1). The time shell command (logging the real output) was used to compare build times for chronometric benchmarking. NAB was logged for combined time of compiling from the Domain-Specific Language (DSL) to the binary and executing the binary, while Ducque can only be logged for Python’s runtime. The structures were evaluated based on root mean square deviation (RMSD) and difference in interbase pair parameters using Curves+ (22).

Force field parametrization for molecular mechanics

The AMBER FF (32,33) is compatible with restraint electrostatic potential (RESP) charges (34). This is a subset of molecular electrostatic potential (MEP) charges sampled with the Merz–Singh–Kollman (MK) population analysis scheme (35,36), followed by a two-stage restraint procedure to derive atomic charges (RESP fitting). The nucleosides were superposed on the X–Z Cartesian plane by the (C1′, C5′, N3′) atoms in the nucleosides through an in-house scripted reorientation (37). The MK population analysis scheme has been implemented, by the authors, for ORCA and detailed here below. This implementation is available in the software repository of the Ducque model builder. Geometry optimization of the molecules was done at the PBE0 level, which was followed by an SPE at the HF/6-31G* level/basisset, with ORCA, to generate the correct molecular density orbitals for RESP (38). The gridpoints are generated through the MSMS software (39) at a range of factors times (1.4, 1.6, 1.8 and 2.0) the van der Waals (vdW) radius, defined by the Connolly surface algorithm (40). The probe radius was set to 1.4 Å, and the density of the points on the surface was set to 3/Å2 (Supplementary Figure S6). MSMS employs a further triangulation of the vertices to distribute them more equally. ORCA’s orca_vpot program is used to map the orbitals and their densities to the respective gridpoints, in atomic units (a.u.). Afterwards, the ESP-loaded grid is provided to the RESP script for a two-stage restraintive procedure, deriving point charges for the atoms. Similar atoms are equivalenced and internal fragments are restrained to a set charge for the respective nucleosides, which ultimately returns the needed RESP charges for the FF (34,38,41). This uses the Chirliam–Francl least square fitting algorithm (42) (Supplementary Figure S7). This methodology was compared against results from GAMESS (43) (Supplementary Figure S6), to compare the grid generation, and against the R.E.D. server (Supplementary Figure S8), to compare charge derivation. With respect to the nucleosides, all atoms in the ring and all substituents were set for equivalencing, except for C1′ and H1′ which should be equivalenced with the nucleobases on the occasion of multiple conformers. Hydrogens belonging to amines of nucleobases are also equivalenced, as are the OP1 and OP2 oxygens in the phosphoramidate linker. For second stage RESP, all methyls and methylenes were equivalenced, due to degenerate hydrogens. The FF of MNA contains charges for 6′-head, 6′-fragments-3′, 3′-tail, neutral and methyl-capped MNA. Only the lowest energy  conformer was considered for charge derivation. To create terminal residues and in-strand fragments, 6′ and 3′ ends were appropriately restrained with the linker to have a net charge of zero.

conformer was considered for charge derivation. To create terminal residues and in-strand fragments, 6′ and 3′ ends were appropriately restrained with the linker to have a net charge of zero.

Finally, all bond, angle and torsion parameters for the morpholino chemistry were manually curated from the parm10.dat frcmod file, contained within the AMBER package, of terms that already described parts of the molecule well, before fitting to the conformers. Only torsion terms of the morpholino ring moiety were fitted. Paramfit (44,45) was used to equate QM to MM energies correctly, which also produces a valid frcmod file. All conformers in Table 1 were initially considered for fitting torsion angles. Finally, only  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  and

and  of the MNA cytosine were employed for fitting. A customized CF atom type was created, which was made equivalent to the standard CT atom type, common in AMBER FFs. This was done so as not to over-ride any parameters when loading in the MNA FF together with the standard FFs.

of the MNA cytosine were employed for fitting. A customized CF atom type was created, which was made equivalent to the standard CT atom type, common in AMBER FFs. This was done so as not to over-ride any parameters when loading in the MNA FF together with the standard FFs.

Table 1.

E rel (in kcal/mol) of the distinct conformers with energy values and their respective position on the CP-sphere’s surface, per given nucleoside; r is omitted as it is assumed to be constant

| Conformer | mA | mG | mC | mT | (θ, ϕ2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | (4.01, 119.75) |

|

7.41 | 7.48 | 8.03 | 7.64 | (53.29, 150.11) |

|

15.41 | 15.59 | 15.83 | 15.50 | (53.29, 179.91) |

|

10.64 | 10.77 | 11.25 | 11.28 | (93.97, 80.21) |

|

7.59 | 8.06 | 8.97 | 8.60 | (93.97, 264.13) |

|

18.76 | 19.39 | 18.46 | 18.40 | (126.62, 0.00) |

|

8.90 | 9.71 | 9.35 | 9.14 | (126.62, 330.02) |

|

17.04 | 17.65 | 19.55 | 19.15 | (175.90, 0.00) |

Molecular mechanics simulations

The MD simulations were run using the AMBER18 software package (32,33) joined with AMBERTools19, employing the Particle Mesh Ewald (PMEMD) simulation engine (46). The MNA FF was imported into LEaP, together with the DNA.OL15 and the RNA.OL3 FF (47,48). The TIP3P water model is used for the explicit solvation, in a truncated octahedron box, and the charges were neutralized. dXyNA parameters (8) use the DNA.OL15 FF; HNA parameters were derived from a similar methodology to that described herein (49). Torsion angles for the linker were taken from the GAFF2 parameters, in combination with phosphate parameters from parm10.dat. A cut-off distance of 12 Å was used for non-bonded interactions. The minimization ran for a total of 30 000 cycles, with the first 22 500 cycles employing the steepest descent method and the last 7500 the conjugate gradient method. The SHAKE algorithm (50) was employed to allow a time step of 2 fs. An initial heating was performed for 50 ps, from 0 K to 100 K with vlimit set to 15. The rest of the heating, from 100 K to 300 K, ran for an additional 50 ps. Density and equilibration ran for 100 ps each, with density set at 1 g/ml. The Langevin thermostat (51) and the Berendsen barostat (52) were used to keep the temperature and density at a constant value. The production simulations were run for 200 ns, unless stated otherwise. Trajectory analysis of the simulations was calculated through Cpptraj (53). MD simulations were run on NVIDIA GeForce RTX 2070 and 2060 through the cuda accelerated simulation engine (54,55). For all duplexes, distance-based nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) restraints were employed for the first 15 ns. For structural comparison, superpositioning of the structures was done with UCSF Chimera’s MatchMaker tool, and all structures were entirely fitted according to their secondary structure. The Curves+ software was used to extract interbase pair data (22).

Results

Charge derivation using ORCA

The ORCA QM package does not contain the MK population analysis scheme. To keep the workflow free, local and easy to use, we implemented the population analysis scheme for ORCA to generate ESP charges that are ready to use for the RESP fitting. Two programs were used to compare Connolly surface grid generation to decide which program is most suited for the task at hand. The AMBERTools-script molsurf.c, which calculates molecular surface areas, was modified to output the vertices of the surface points by which it computes surface areas. A second program, MSMS, was also tested [Scripps Research Institute, utilized by VMD (56) and UCSF Chimera (57)]. The latter computes a further triangulation of the solvent-excluded surfaces (SESs) to generate an even distribution of points across the surface of the molecule. Upon visual inspection and level of customizability of the grid (atomic and probe radii, point density), MSMS was hugely favored.

Further comparison of the method was done against GAMESS’ output, which defaults to a grid with a density of 1/Å2. Our implementation for ORCA uses a density of 3/Å2 (35,36). The point density of 1/Å2 was used for our method to compare against GAMESS. Our methodology shows an even distribution of the surface, compared with GAMESS, and we decided to proceed with this approach as it produced a near-identical range of ESP values to that of GAMESS’ (Supplementary Figures S6 and S7). A benchmarking against RESP-charge derivation by the R.E.D. server (58) was carried out on HNA nucleosides. We see near-identical atomic charges being fitted to the atoms in the respective nucleosides (Supplementary Figure S8). Data points from either methodology were compared by pairwise atom alignment (linear regression, SciPy) per nucleoside. This results in an r2 of 0.985 for hA, 0.985 for hC, 0.987 for hG and 0.979 for hT.

RNA and DNA model building by Ducque

A-type and B-type duplexes of DNA and RNA (Supplementary Figure S10A1) have been built by Ducque and its performance was compared with that of NAB to assess its model building capacity.

Conserving the planarity of the nucleobases is necessary because Ducque’s placement and fitting of the nucleosides in the strands assumes planarity of the nucleobases (Supplementary Figure S2). Because of their sp3 type hybridization, amines tend towards slight tetrahedral structures in nucleobases, and this gets more pronounced in ab initio calculations at MP2 levels with midsized basis sets for geometry optimizations. This compromises the flatness of the nucleobase by several tenths of degrees for the nitrogen involved in the glycosidic bond, to several degrees for the amine on the six-membered ring in purines (59). Optimizing at the current level compromises the planarity assumption, introducing distortions during duplex building, and causes peculiar rotations of nucleotides in the final model. Note that, using larger basis sets, i.e. reaching complete basis set, decreases the degree of pyramidalization (60). Using this basis would be too computationally intensive for our needs and would only fine-tune details that would be negated in the following simulations. Therefore, the planarity issue of nucleobases was resolved by the use of planarity restraints on nucleobases during HF-3c geometry optimizations, providing nucleosides for the Ducque library with planar nucleobases, as in NAB.

The quality of the model building is assessed by superpositioning generated models from NAB (18) versus Ducque (Supplementary Table S1; Supplementary Figure S9), which was done across all (12) residue pairs on heavy atoms, for 10 models of DNA and RNA each per software. For DNA, the mean RMSD value is 0.011 Å (± 0.005), with the lowest value being 0.004 Å. For RNA, the mean RMSD value is 0.169 Å (± 0.042), with the lowest value being 0.109 Å. The near-zero RMSD showcases Ducque’s qualitative output. For the interbase pair parameters, we see that the Ducque structures are in good agreement with those of NAB. Only the roll parameter, for RNAs, seems to slightly differ. This stems from the fitting protocol not rolling all nucleobases with the exact same value, as this feature is not hardcoded. The simulated structure for the DNA and RNA homoduplex experiments, generated by both NAB and Ducque, show equivalent RMSD trajectories, as is to be expected given the similarity of the starting structures. Since all structures minimized without a problem, both the comparison of structural parameters and the following simulations indicate the quality of the generated structures. With respect to wallclock building time, NAB averaged 0.272 s and 0.245 s for DNA and RNA, respectively. Ducque, averaging 0.328 s and 0.234 s for DNA and RNA, respectively, takes infinitesimally longer for DNA as it considers multiple conformers during the fitting (benchmarked with Python3.12).

MD simulations on Ducque’s models validated with (X)NA structures in the literature

To assess the quality of Ducque’s models for MD simulations, a series of duplexes were studied, starting with (deoxy)ribose-based nucleic acids, which employed the standard AMBER DNA.OL15 and RNA.OL3 FFs. The simulated structures for the DNA and RNA homoduplex experiments, generated by both NAB and Ducque, show equivalent RMSD trajectories (Supplementary Table S1; Supplementary Figure S9), as expected given the similarity of the starting structures. An MD simulation on a B-type DNA::RNA and A-type RNA::DNA duplex of identical sequence both built by Ducque converged into the same A-like structure, as experimentally determined in Davis et al. (61) (Supplementary Figure S11). A second experiment was performed with the dXyNA homoduplex. This started out from a typical ladder-like structure (8). During the MD simulation, the initial structure of the duplex undergoes a remarkable transition to a highly dynamic, left-handed helix (Supplementary Figures S13 and S20; Supplementary Table S4) that matches the type II duplex previously described for xylose-based nucleic acids (62–64), having significantly different backbone dihedral angles compared with those in the initial model. Thirdly, an RNA::HNA duplex was built, using the lowest energy  conformations of the PES (26) of the four nucleobases and were prepared and loaded into Ducque’s library. A subsequent MD simulation resulted in a stable duplex that matches crystallographic results on sugar puckering as well as overall helical structure (65) (Supplementary Figure S12). The methodology of deriving torsional parameters for HNA has been validated already (49), and it has also been applied to deriving the parameters for the MNA chemistry.

conformations of the PES (26) of the four nucleobases and were prepared and loaded into Ducque’s library. A subsequent MD simulation resulted in a stable duplex that matches crystallographic results on sugar puckering as well as overall helical structure (65) (Supplementary Figure S12). The methodology of deriving torsional parameters for HNA has been validated already (49), and it has also been applied to deriving the parameters for the MNA chemistry.

Using the proposed workflow to gain insight in RNA::MNA

Quantum mechanics to characterize the nucleosides and linker

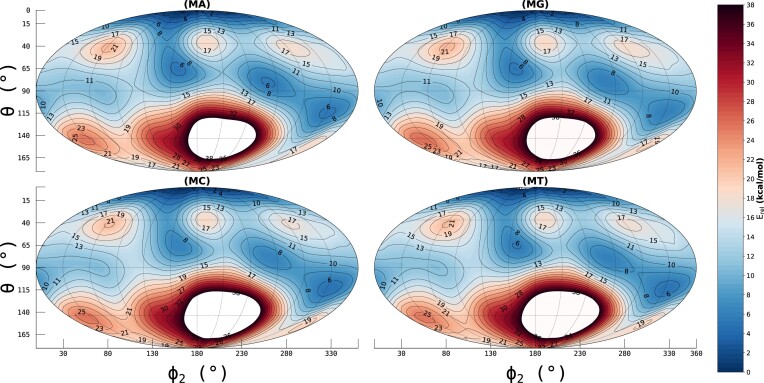

Following the procedure described by Mattelaer et al. (26), PESs were generated for the morpholino nucleosides with adenine, guanine, thymine and cytosine nucleobases. We observed intramolecular hydrogen bonds in the initial calculations, inflating equatorial conformations towards higher energy potentials (Supplementary Figure S14). Those observed hydrogen bonds, which would not exist in a polymeric molecule, introduce a forced steric strain on the nucleoside that would not yield representative FF parameters that are applicable for simulations on ONs. For the capped MNA variant (Figure 2; Table 1), we see a global minimum on the north pole of the CP-sphere, a  configuration for all four nucleosides. Local minima are observed mainly on the upper hemisphere, separated by large peaks corresponding to envelope configurations. Equatorial puckering modes tend to be more energetically favorable, with boats and skews alike. A final local minimum is observed on the southern hemisphere, in the east.

configuration for all four nucleosides. Local minima are observed mainly on the upper hemisphere, separated by large peaks corresponding to envelope configurations. Equatorial puckering modes tend to be more energetically favorable, with boats and skews alike. A final local minimum is observed on the southern hemisphere, in the east.

Figure 2.

Potential energy surface of the MNA. Methyl-caps substitued the HO6′ and NH3′ on the O6′ and N3′ atoms, respectively, to mimic estimated backbone angles and prevent internal hydrogens bonds from occurring during geometry optimizations.

The N,N-dimethylaminophosphoramidate represents the linkage between successive morpholino nucleosides, where the N,N-dimethylamino mimics the effect of the preceding mopholino ring. A sampling of the (ζ, α) dihedral dyad was carried out too. Minima were found at (t, g+), (t, g−), (g−, g−), (g+, g+) and (g−, ap+) (Figure 3). A hard ridge (α = 180 ± 30°) splits the PES in two. Its cause is attributed to steric clashes during the sampling itself, due to methyls on either end of the linker residing in close proximity to one another at α in the anti range.

Force field parametrization

The PESs of the four morpholino nucleosides succesfully provided valuable information on transitional pathways. By using the improper dihedrals (α1, α2, α3) as restraints on the pyranose ring, we gained information of possible transitions of conformations as well as puckers we should be expecting. Conformations highlighted in Table 1 are conformations that were initially considered for parametrization, specifically for fitting of the sugar torsion angles (see Supplementary Figure S5 for a reference to their respective physical location on the PES). Parameters for dihedral terms of only the morpholino ring were refined by fitting to QM conformational energy (44). In this procedure, the quality of the FF depends on the functionals and basis sets used for optimizations, as well as which conformations should be curated from the PES and included in the fitting process. The methylated ends were kept during optimization and the fitting, as the initial problem of internal hydrogen bonds observed during PES calculation reappeared when reverting back to hydroxyls. Iterative curation of the returned parameters resulted in a simplification of the dataset; only the morpholino cytosine was included with the following puckers:  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  and

and  .

.

For the linker fragment, the minima and transition (g−, g+) conformers of the lower half were used to derive partial charges. Since upper half conformers are mirror images of the lower half, they were not considered. The linker torsional parameters were obtained from GAFF2 (66) and are in good agreement with the PES (Figure 3C). The (ζ, α) dihedral dyad values were extracted from the simulation and categorized into discrete integer values, for then to be normalized and plotted. This shows a clear and single peak at the (t, g−) range, which is in contrast to the standard phosphate, that stabilizes in the (g−, g+) range in a DNA or RNA duplex (67). This validates usage of the GAFF2 parameters for the linker. Note that a single peak is attributed to the conformational constraints that the linker is submitted to in a polynucleotide chain, which clarifies why multiple minima are perceived in the PES, but only one can be inhabited.

Molecular model of RNA::MNA

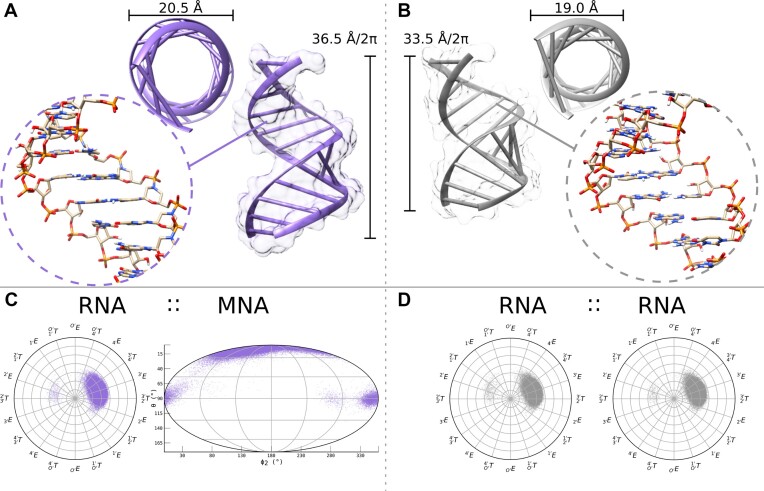

The RNA::MNA duplex was built in Ducque starting with a 24-mer RNA sequence corresponding to a double-DDD (5′-CGCGAAUUCGCGCGCGAAUUCGCG-3′, residues 1–24) with the geometry of an A-type duplex. All  MNA nucleosides were ported into Ducque and queried as the complementary strand (residues 25–48). The obtained initial structure was subjected to an MM simulation. An RNA::RNA duplex with identical sequence was generated and simulated for comparative purposes. Results of the simulation are summarized in Figure 4. In the last 50 ns of the MD trajectory, a pronounced prevalence for the

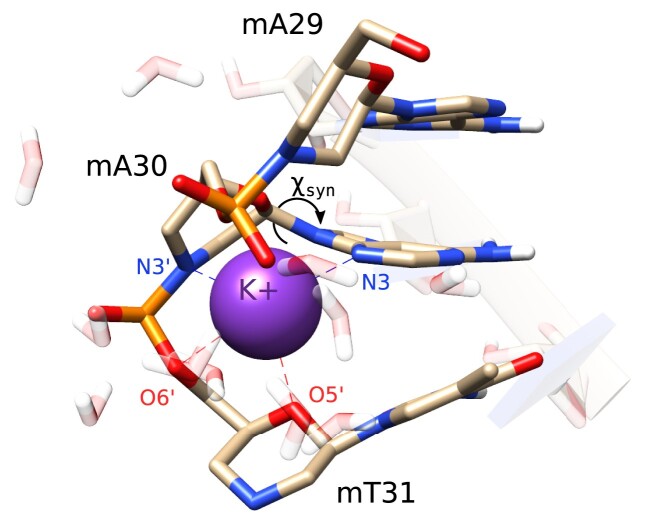

MNA nucleosides were ported into Ducque and queried as the complementary strand (residues 25–48). The obtained initial structure was subjected to an MM simulation. An RNA::RNA duplex with identical sequence was generated and simulated for comparative purposes. Results of the simulation are summarized in Figure 4. In the last 50 ns of the MD trajectory, a pronounced prevalence for the  conformation in the conformational wheel is observed for RNA nucleosides in both the dsRNA and heteroduplex model (Figure 4C, D; Supplementary Table S2). The puckering modes for the morpholino rings observed on the CP-sphere (Figure 4C), in the same time frame as stated earlier, largely correspond to the low energy regions of the PES (Figure 2) The scattered, equatorial conformers correspond to residues 30–31. Their appearance correlates with a K+ ion that had been enclosed by two MNA residues (30–31) during the second half of the simulation. Its binding induced local backbone angles to deviate substantially from the other nucleosides, off-setting average and standard deviation (SD) parameters by several degrees. Up to four (25–28) residues had frayed (forming C, E and B conformers alike), causing residue 28 with a guanine nucleobase (mG28) to have its β angle twisted into an unfavorable position. Structural changes due to K+ binding destabilized downstream stacking, which causes mA30 to lose pairing with its complement. This resulted in a nearby K+ ion altering the orientation of the χ angle of the freed nucleotide from anti to syn (68). The base pairing of mA30 with its complement was reinstated later, in Hoogsteen (HG), with the ion bound (Supplementary Figure S16). The K+ ion is coordinated by mT31:O6′, mT31:O5′ and mA30:N3′ in the MNA backbone and N3 of the nucleobase in mA30. Coordination of K+ by N3′ in the morpholino ring of mA30 forces it into metastable configurations (Figure 6), as can also be seen on the scatterplots, around the equator (Figure 4C). As this obvious abnormality is attributable to an odd occurrence of the simulation and not the FF itself, data of mA30 and m31 are excluded in Table 2 and Supplementary Table S2. This behavior was not observed in the preliminary RNA::MNA simulations (Supplementary Figure S15). Except for the χ dihedral angle with a deviation of 2.39–2.93°, no significant differences in average backbone angles in the RNA backbone could be observed in the RNA::MNA duplex versus the model obtained for dsRNA (Supplementary Table S2). However, helical parameters significantly deviate from the A-type duplex (Table 2) with a deeper major groove, and conversely a narrower minor groove, an increase in base pairs per turn and therefore helical size, along with a larger diameter.

conformation in the conformational wheel is observed for RNA nucleosides in both the dsRNA and heteroduplex model (Figure 4C, D; Supplementary Table S2). The puckering modes for the morpholino rings observed on the CP-sphere (Figure 4C), in the same time frame as stated earlier, largely correspond to the low energy regions of the PES (Figure 2) The scattered, equatorial conformers correspond to residues 30–31. Their appearance correlates with a K+ ion that had been enclosed by two MNA residues (30–31) during the second half of the simulation. Its binding induced local backbone angles to deviate substantially from the other nucleosides, off-setting average and standard deviation (SD) parameters by several degrees. Up to four (25–28) residues had frayed (forming C, E and B conformers alike), causing residue 28 with a guanine nucleobase (mG28) to have its β angle twisted into an unfavorable position. Structural changes due to K+ binding destabilized downstream stacking, which causes mA30 to lose pairing with its complement. This resulted in a nearby K+ ion altering the orientation of the χ angle of the freed nucleotide from anti to syn (68). The base pairing of mA30 with its complement was reinstated later, in Hoogsteen (HG), with the ion bound (Supplementary Figure S16). The K+ ion is coordinated by mT31:O6′, mT31:O5′ and mA30:N3′ in the MNA backbone and N3 of the nucleobase in mA30. Coordination of K+ by N3′ in the morpholino ring of mA30 forces it into metastable configurations (Figure 6), as can also be seen on the scatterplots, around the equator (Figure 4C). As this obvious abnormality is attributable to an odd occurrence of the simulation and not the FF itself, data of mA30 and m31 are excluded in Table 2 and Supplementary Table S2. This behavior was not observed in the preliminary RNA::MNA simulations (Supplementary Figure S15). Except for the χ dihedral angle with a deviation of 2.39–2.93°, no significant differences in average backbone angles in the RNA backbone could be observed in the RNA::MNA duplex versus the model obtained for dsRNA (Supplementary Table S2). However, helical parameters significantly deviate from the A-type duplex (Table 2) with a deeper major groove, and conversely a narrower minor groove, an increase in base pairs per turn and therefore helical size, along with a larger diameter.

Figure 4.

Comparison of the RNA::MNA and RNA::MNA duplexes. Trajectory of the simulation in Supplementary Figure S15. Scatterplots are not to be confused with prevalence plots, as scatterplots do not represent normalized data, but represent all data extracted. (A) Visualization of the diameter and the helicity for the RNA::MNA duplex. (B) Visualization of the diameter and the helicity for the RNA::RNA duplex. (C) Scatterplot to represent puckering modes of both RNA (leading) and MNA (complementary) during the last 50 ns of the simulation. (D) Scatterplot to represent puckering modes of RNA (both leading and complementary) during the last 50 ns of the simulation.

Figure 6.

The K+ ion enclosed in the backbone. Notice the glycosidic bond angle of mA30 having shifted to a syn configuration. See Supplementary Figure S16 for a detailed look into the enclosed ion throughout the MD simulation.

Table 2.

Helical parameters of the RNA::MNA heteroduplex in comparison with the RNA::RNA homoduplex (top), and the χ-restrained RNA::RNA homoduplexes (bottom)

| Helical parameter | RNA::MNA | RNA::RNA |

|---|---|---|

Helicity

|

35.83 (± 4.74) | 32.50 (± 3.04) |

Base pairs per turn

|

12 | 11 |

| Major groove (Å) | 15.90 (± 3.30) | 9.86 (± 3.21) |

| Minor groove (Å) | 6.69 (± 0.62) | 9.76 (± 0.62) |

| Diameter (Å) | 20.18 (± 0.50) | 19.07 (± 0.55) |

| Tilt (°) | –1.34 (± 4.73) | –0.05 (± 4.61) |

| Twist (°) | 28.06 (± 3.99) | 29.64 (± 4.18) |

| Roll (°) | 5.51 (± 6.27) | 7.37 (± 6.42) |

| Helical parameter | RNA::RNAχ194 | RNA::RNAχ189 |

Helicity

|

35.54 (± 2.89) | 37.92 (± 3.23) |

Base pairs per turn

|

12 | 12–13 |

| Major groove (Å) | 9.98 (± 3.17) | 13.27 (± 2.91) |

| Minor groove (Å) | 9.64 (± 0.49) | 9.43 (± 0.44) |

| Diameter (Å) | 18.99 (± 0.55) | 18.91 (± 0.60) |

| Tilt (°) | 0.014 (± 3.73) | –0.08 (± 3.70) |

| Twist (°) | 29.58 (± 3.85) | 28.70 (± 3.85) |

| Roll (°) | 4.35 (± 5.46) | 2.75 (± 5.35) |

Data were extracted from the last 50 ns of the 200 ns simulation. Grooves and helicity are as determined in Saenger et al. (69). Tilt, twist and roll parameters were determined by the Curves+ software on a 1000 frames that were extracted over the whole length of the trajectory (22). See Supplementary Figure S15 for details on interbase pair parameters.

To investigate a possible correlation of the altered χ angle in the RNA strand to the overall shape for the nucleic acid duplex, we performed two supplementary RNA::RNA double-DDD simulations (Supplementary Figures S18 and S19). While in the original simulations, the χ torsion angle was unrestrained, in the additional simulations restraints are applied on χ torsion angles at 194° and 189°, respectively, to mimic the impact on the overall helix structure by increasing deviation from the 199° χ angle in standard A-type duplexes, at 5° increments. The helical parameters of the RNA::RNA duplex with χ torsion angles restraints at 194° are in line with those of the unrestrained RNA::MNA duplex (Table 2; Supplementary Table S3). The observed deviations from the A-type duplex are more pronounced in the RNA::RNA duplex with χ torsion angles restraints at 189°.

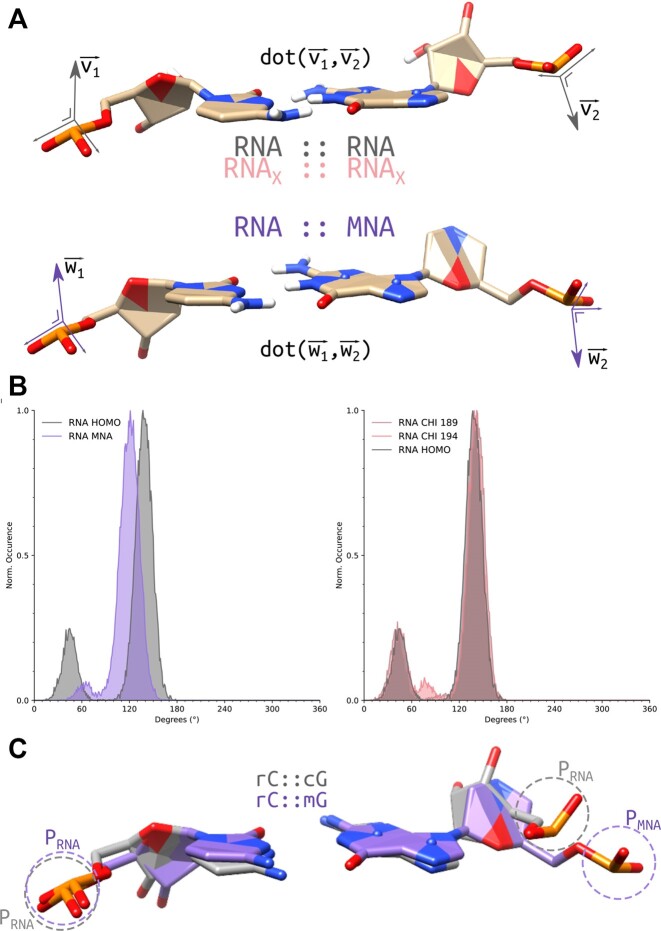

To compare the orientation of P atoms in the linker in complementary strands, the dot product of the cross product of the OP1–P–OP2 plane of the leading RNA nucleotide and complementary MNA nucleotide was calculated and compared with values obtained for corresponding base pairs in three simulations performed on dsRNA (Figure 5). Normalized distribution per duplex type shows a clear peak for the RNA::RNA duplexes around 137–139° while for RNA::MNA it peaks at 120–122°. An overlay of a set of the unrestrained RNA::RNA and RNA::MNA C–G base pairs shows that not only the oriention of P in the MNA strand is changed but also its position relative to the corresponding P in dsRNA.

Figure 5.

(A) Calculated angles, by the dot product of the cross product of the OP1–P–OP2 plane of the leading nucleotide and complementary nucleotide. Sampled on 1000 frames, extracted from the entire simulation, of the double-DDD of RNA::RNAunrestr., RNA::MNA, RNA::RNAχ189 and RNA::RNAχ194, respectively, for a total distribution of 23 000 angle values per duplex type. (B) Normalized distribution per duplex type shows a clear peak for the RNA::RNA duplexes around 137–139°, while for RNA::MNA it peaks at 120–122°. (C) Overlay of a set of RNA::RNA and RNA::MNA C–G base pairs, to visualize the displacement of P in MNA relative to the corresponding RNA in the homoduplex.

Discussion

XNAs are a class of synthetic molecules that differ from naturally occurring nucleic acids in the use of an altered backbone that can impact the three-dimensional structure, stability and processing by naturally occurring biological processes. Results on numerous XNAs have been synthesized and characterized in the last decades, revealing that the ability to form stable homoduplexes and heteroduplexes with natural nucleic acids determines potential applications (25). Molecular modeling simulations can provide understanding and predict how changes in the sugar–phosphate backbone impact on the complementation properties of the nucleic acids. However, the missing link in this field is a software tool that builds initial XNA models beyond ribose-based nucleic acids and robust FF parametrization to perform MM simulations within standard packages such as AMBER. To fill this gap, we introduced a streamlined molecular modeling approach starting from quantum mechanics on XNA fragments. The versatile nucleic acid builder (Ducque) presented here builds XNA structures with unlimited backbone chemistry. It relies on a library of nucleosides and linkers that is user-extendable. We demonstrated that the tool can build initial models starting from preferably low energy conformations of nucleosides and linkers, extracted from conformational sampling experiments. The latter also delivered data for FF parametrization required to perform MM simulations on the initial model. Ducque produced models of RNA and DNA duplexes as fast as the NAB tool. The latter is part of the AMBER toolkit and requires other AMBER programs (such as tLEaP) to run, whereas Ducque functions as a standalone software. Syntactically, Ducque reads in simple text files to directly generate a model, as opposed to NAB’s DSL which writes like C code and requires compilation of and executing the produced binary. Produced initial models are highly similar for both model builders and provided the same results in a subsequent MD simulation in standard FFs of AMBER. In contrast to NAB, Ducque is not limited to ribose-based nucleic acids. Low energy conformations for non-ribose-based nucleosides with hexitol and xylose sugars were included in the Ducque library, among others, and served to build nucleic acid duplexes for which MD simulations could be performed using a parametrized FF within AMBER (8,49). As sugar puckering is crucial for the backbone geometry and flexibility, we used Paramfit to optimize dihedral FF parameters on non-ribose nucleosides by fitting QM to MM energies of selected conformations of nucleosides after RESP charges had been calculated through the ORCA implementation. Linker parameters from GAFF2 were validated through QM approaches.

The initial RNA::HNA duplex was built and remained stable during the MD round. Ducque’s model of the dXyNA homoduplex with backbone dihedrals for a ladder-like structure converged towards the left-handed helical structure in the MD simulation, confirming what was predicted for the dXyNA duplex (62–64) (Supplementary Figure S13). This result, and that of the DNA::RNA heteroduplex, ensured that dihedral angles used for model building in Ducque did not determine the outcome of the MD simulation.

Following the protocol to obtain the RNA::HNA duplex, we generated an RNA::MNA duplex. The charges for the MNA chemistry were derived using the new ORCA implementation, that was evaluated on HNA. The methodology described to derive charges for naturally occurring RNA modifications (41) starts off differently from that described in this work, but has the same goal. According to the proposed workflow, low energy conformations of nucleosides and the linker are described by QM calculations and ported to the Ducque library. In line with the available crystal structure (70), the  chair having the nucleobase in an equatorial position turned out to be the lowest energy conformation of morpholino nucleosides according to QM. An initial model was produced by Ducque and subjected to an MM simulation using an FF that was parametrized as described in the Materials and Methods. The RNA::MNA heteroduplex simulations yielded a right-handed helical structure that does not belong to the A- or B-type family (71). The morpholino rings remain predominantly in their chair conformation with an equatorial orientation of the nucleobase. In homoduplexes of (4′→6′)-(β-d-glucopyranosyl)oligonucleotides (or β-homo-DNA) (3) and (4′→ 6′)- and (3′→6′)-pentopyranose systems (72), this conformation is adopted by the six-membered pyranoses in the backbone but none of these XNA chemistries is able to communicate by base pairing with either RNA or DNA. Changing the C1′ configuraton (e.g. α-homo-DNA) or having the nucleobase on a C2′ axial position instead of the regular C1′ anomeric (equatorial) site of the six-membered ring in the ‘glycon’ moiety (HNA) generated XNA systems that cross-pair with natural nucleic acids (6). Except for a Watson–Crick–Franklin (WCF) to Hoogsteen (HG) transition in an mA:U base pair (Figure 6), that was facilitated by K+ binding and fraying at the helix end, stable WCF base pairing was observed during the MM simulation. Transitions between WCF and HG base pairing could be important in DNA recognition and replication, but are difficult to investigate experimentally because they are rare and short-lived. A transition from WCF to HG base pairing had been observed before for DNA in relaxation dispersion NMR experiments (73). The same outside route transition from WCF to HG base pairing was observed in DNA simulations, as the nucleotide temporarily unpairs and interacts with the solute, before repairing (74). The occurrence of a WCF to HG transition in the final MNA::RNA simulation demonstrates that our optimized dihedral FF parameters allow puckering in the morpholino ring that is also expected in real life.

chair having the nucleobase in an equatorial position turned out to be the lowest energy conformation of morpholino nucleosides according to QM. An initial model was produced by Ducque and subjected to an MM simulation using an FF that was parametrized as described in the Materials and Methods. The RNA::MNA heteroduplex simulations yielded a right-handed helical structure that does not belong to the A- or B-type family (71). The morpholino rings remain predominantly in their chair conformation with an equatorial orientation of the nucleobase. In homoduplexes of (4′→6′)-(β-d-glucopyranosyl)oligonucleotides (or β-homo-DNA) (3) and (4′→ 6′)- and (3′→6′)-pentopyranose systems (72), this conformation is adopted by the six-membered pyranoses in the backbone but none of these XNA chemistries is able to communicate by base pairing with either RNA or DNA. Changing the C1′ configuraton (e.g. α-homo-DNA) or having the nucleobase on a C2′ axial position instead of the regular C1′ anomeric (equatorial) site of the six-membered ring in the ‘glycon’ moiety (HNA) generated XNA systems that cross-pair with natural nucleic acids (6). Except for a Watson–Crick–Franklin (WCF) to Hoogsteen (HG) transition in an mA:U base pair (Figure 6), that was facilitated by K+ binding and fraying at the helix end, stable WCF base pairing was observed during the MM simulation. Transitions between WCF and HG base pairing could be important in DNA recognition and replication, but are difficult to investigate experimentally because they are rare and short-lived. A transition from WCF to HG base pairing had been observed before for DNA in relaxation dispersion NMR experiments (73). The same outside route transition from WCF to HG base pairing was observed in DNA simulations, as the nucleotide temporarily unpairs and interacts with the solute, before repairing (74). The occurrence of a WCF to HG transition in the final MNA::RNA simulation demonstrates that our optimized dihedral FF parameters allow puckering in the morpholino ring that is also expected in real life.

Only subtle changes in dihedral angles of the RNA strand, compared with values measured in dsRNA A-type helices, are imposed by the complementary MNA. To complement MNA, RNA adapts to the conformational constraints of the rigid binding partner with a more anti-characterized χ torsion angle, while other dihedral angles remain close to what is observed in dsRNA (Supplementary Table S2; Supplementary Figure S19). This minor difference significantly changes helical parameters for helicity, groove widths and roll and twist of the duplex, as was demonstrated by restrained MD on dsRNA resulting in the same effect that is more pronounced if restraints on χ torsion angles deviate further from the 199° observed in A-type duplexes (Table 2). The increased diameter can be attributed to the six-membered morpholino ring in the backbone, in line with other XNAs with six-membered sugar moieties (65,75). The unique chemistry of the MNA backbone changed the orientation of the phosphoramidate in MNA and displaced the P atom to a position where it does not align with phosphates in the backbone of standard RNA (Figure 5). A combination of the significantly different helical parameters, such as increased radius of the double helix and altered positioning of the phosphoramidate due to the morpholino ring, can all contribute to the lack of RNA degradation when bound to complementary MNA sequences (15).

Conclusion

The current work describes Ducque, a free and open-source program to construct initial models for (synthetic) nucleic acid duplexes of virtually any XNA chemistry. The DNA and RNA chemistries were already well documented in the literature with both crystallographic and NMR structures. This allowed parameters to be fitted on nucleosides whose behavior has already been described in detail. For a given XNA that has not benefitted yet from years of characterization, it is shown that the computed PESs are exceptionally accurate in predicting its behavior.

This study proves that not only can Ducque easily build any type of structure for a given chemistry, but that with the correct FF an accurate prediction can be modeled. We demonstrated that one can extend the nucleic acid library with new sugars and nucleoside linkers. Ducque requires only built-in and NumPy modules, and Tkinter for the GUI. The user can supply Ducque with chemistries and their respective conformations, which can be confidently generated with the conformational sampling scheme. Additionally, a suitable FF can be derived.

The RNA::MNA heteroduplex simulations yielded a right-handed helical structure that does not belong to the A- or B-type family. Only subtle changes in dihedral angles of the RNA strand, compared with values measured in dsRNA A-type helices, are imposed by the complementary MNA. The significantly different helical parameters, such as increased radius of the double helix and altered positioning of the phosphoramidate due to the morpholino ring, can all contribute to the lack of RNA degradation when bound to complementary MNA sequences. Except for a WCF to a HG transition in an mA:U base pair, that was facilitated by K+ binding and fraying at the helix end, stable WCF base pairing was observed during the MM simulation. This agrees well with the available data showing that the heteroduplex differs from either A- and B-type duplexes and it is strongly suspected that it acts as a steric block, in the ASO pathways, as it has also been demonstrated that the heteroduplex is not fit for degradation by the RNase H enzyme (15,71).

Supplementary Material

Contributor Information

Jérôme Rihon, Laboratory of Medicinal Chemistry, Rega Institute for Medical Research, Herestraat 49, Box 1030, B-3000 Leuven, Belgium.

Charles-Alexandre Mattelaer, Laboratory of Medicinal Chemistry, Rega Institute for Medical Research, Herestraat 49, Box 1030, B-3000 Leuven, Belgium; Quantum Chemistry and Physical Chemistry, Celestijnenlaan 200f, Box 2404, B-3001, Leuven, Belgium.

Rinaldo Wander Montalvão, Laboratory of Medicinal Chemistry, Rega Institute for Medical Research, Herestraat 49, Box 1030, B-3000 Leuven, Belgium; Gain Therapeutics sucursal en España, Barcelona Science Park, Baldiri Reixac 4-10, 08028 Barcelona, Spain.

Mathy Froeyen, Laboratory of Medicinal Chemistry, Rega Institute for Medical Research, Herestraat 49, Box 1030, B-3000 Leuven, Belgium.

Vitor Bernardes Pinheiro, Laboratory of Medicinal Chemistry, Rega Institute for Medical Research, Herestraat 49, Box 1030, B-3000 Leuven, Belgium.

Eveline Lescrinier, Laboratory of Medicinal Chemistry, Rega Institute for Medical Research, Herestraat 49, Box 1030, B-3000 Leuven, Belgium.

Data availability

The data underlying this article are available in ModelArchive, at https://www.modelarchive.org/doi/10.5452/ma-qaldv. The source code of the Ducque model software is available in Figshare at DOI: 10.6084/m9.figshare.24184158.

Supplementary data

Supplementary Data are available at NAR Online.

Funding

The Research Foundation-Flanders (FWO) [G085321N to J.R. and 1S23217N to C.A.M.] and KU Leuven Research fund [C14/19/102]. Funding for open access charge: FWO [G085321N].

Conflict on interest statement

None declared.

References

- 1. Gait M.J., Agrawal S.. Introduction and history of the chemistry of nucleic acids therapeutics. Methods Mol. Biol. 2022; 2434:3–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Chaput J.C., Herdewijn P.. What is XNA. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2019; 58:11570–11572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Egli M., Manoharan M.. Chemistry, structure and function of approved oligonucleotide therapeutics. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023; 51:2529–2573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Pinheiro V.B., Taylor A.I., Cozens C., Abramov M., Renders M., Zhang S., Chaput J.C., Wengel J., Peak-Chew S.-Y., McLaughlin S.H.et al.. Synthetic genetic polymers capable of heredity and evolution. Science. 2012; 336:341–344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Groaz E., Herdewijn P.. Sugimoto N. Hexitol nucleic acid (HNA): from chemical design to functional genetic polymer. Handbook of Chemical Biology of Nucleic Acids. 2023; Singapore: Springer Nature; 1–34. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lescrinier E., Froeyen M., Herdewijn P.. Difference in conformational diversity between nucleic acids with a six-membered ‘sugar’ unit and natural ‘furanose’ nucleic acids. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003; 31:2975–2989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Koshkin A.A., Singh S.K., Nielsen P., Rajwanshi V.K., Kumar R., Meldgaard M., Olsen C.E., Wengel J.. LNA (locked nucleic acids): synthesis of the adenine, cytosine, guanine, 5-methylcytosine, thymine and uracil bicyclonucleoside monomers, oligomerisation, and unprecedented nucleic acid recognition. Tetrahedron. 1998; 54:3607–3630. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Mattelaer C.-A., Maiti M., Smets L., Maiti M., Schepers G., Mattelaer H.-P., Rosemeyer H., Herdewijn P., Lescrinier E.. Stable hairpin structures formed by xylose-based nucleic acids. ChemBioChem. 2021; 22:1638–1645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Yang H., Eremeeva E., Abramov M., Jacquemyn M., Groaz E., Daelemans D., Herdewijn P.. CRISPR-Cas9 recognition of enzymatically synthesized base-modified nucleic acids. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023; 51:1501–1511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Roshmi R., Yokota T.. Viltolarsen for the treatment of Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Drugs Today. 2019; 55:627–639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Chen S., Le B.T., Rahimizadeh K., Shaikh K., Mohal N., Veedu R.N.. Synthesis of a morpholino nucleic acid (MNA)-uridine phosphoramidite, and exon skipping using MNA/2’-O-methyl mixmer antisense oligonucleotide. Molecules. 2016; 21:1582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Moulton J.D. Using morpholinos to control gene expression. Curr. Protoc. Nucleic Acid Chem. 2017; 68:4–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Corey D.R., Abrams J.M.. Morpholino antisense oligonucleotides: tools for investigating vertebrate development. Genome Biol. 2001; 2:REVIEWS1015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Roberts T.C., Langer R., Wood M.J.. Advances in oligonucleotide drug delivery. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2020; 19:673–694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Nan Y., Zhang Y.-J.. Antisense phosphorodiamidate morpholino oligomers as novel antiviral compounds. Front. Microbiol. 2018; 9:750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lebleu B., Moulton H.M., Abes R., Ivanova G.D., Abes S., Stein D.A., Iversen P.L., Arzumanov A.A., Gait M.J.. Cell penetrating peptide conjugates of steric block oligonucleotides. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2008; 60:517–529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Vanmeert M., Razzokov J., Mirza M.U., Weeks S.D., Schepers G., Bogaerts A., Rozenski J., Froeyen M., Herdewijn P., Pinheiro V.B.et al.. Rational design of an XNA ligase through docking of unbound nucleic acids to toroidal proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019; 47:7130–7142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Macke T.J. NAB: a language for molecular manipulation. 1996; The Scripps Research Institute; PhD thesis. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Macke T.J., Case D.A.. Leontis N.B., SantaLucia J., Jr.. Modeling unusual nucleic acid structures. Molecular Modeling of Nucleic Acids. 1998; Washington, DC: ACS Publications; 379–393. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Alenaizan A., Barnett J.L., Hud N.V., Sherrill C.D., Petrov A.S.. The proto-Nucleic Acid Builder: a software tool for constructing nucleic acid analogs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020; 49:79–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lu X.-J., Olson W.K.. 3DNA: a versatile, integrated software system for the analysis, rebuilding and visualization of three-dimensional nucleic-acid structures. Nat. Protoc. 2008; 3:1213–1227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lavery R., Moakher M., Maddocks J.H., Petkeviciute D., Zakrzewska K.. Conformational analysis of nucleic acids revisited: Curves+. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009; 37:5917–5929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Duffy K., Arangundy-Franklin S., Holliger P.. Modified nucleic acids: replication, evolution, and next-generation therapeutics. BMC Biol. 2020; 18:112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Eremeeva E., Herdewijn P.. Non canonical genetic material. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2019; 57:25–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Anosova I., Kowal E.A., Dunn M.R., Chaput J.C., Van Horn W.D., Egli M.. The structural diversity of artificial genetic polymers. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015; 44:1007–1021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Mattelaer C.-A., Mattelaer H.-P., Rihon J., Froeyen M., Lescrinier E.. Efficient and accurate potential energy surfaces of puckering in sugar-modified nucleosides. J. Chem. Theor. Comput. 2021; 17:3814–3823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Deserno M. How to generate equidistributed points on the surface of a sphere. If Polymerforshung (Ed.). 2004; 99: [Google Scholar]

- 28. Cremer D., Pople J.. General definition of ring puckering coordinates. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1975; 97:1354–1358. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Strauss H.L., Pickett H.M.. Conformational structure, energy, and inversion rates of cyclohexane and some related oxanes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1970; 92:7281–7290. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Neese F., Wennmohs F., Becker U., Riplinger C.. The ORCA quantum chemistry program package. J. Chem. Phys. 2020; 152:224108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Harris C.R., Millman K.J., van der Walt S.J., Gommers R., Virtanen P., Cournapeau D., Wieser E., Taylor J., Berg S., Smith N.J.et al.. Array programming with NumPy. Nature. 2020; 585:357–362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Case D.A., Cheatham T.E., III, Darden T., Gohlke H., Luo R., Merz K.M. Jr, Onufriev A., Simmerling C., Wang B., Woods R.J.. The Amber biomolecular simulation programs. J. Comput. Chem. 2005; 26:1668–1688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Salomon-Ferrer R., Case D.A., Walker R.C.. An overview of the Amber biomolecular simulation package. WIREs Comput. Mol. Sci. 2013; 3:198–210. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Bayly C.I., Cieplak P., Cornell W., Kollman P.A.. A well-behaved electrostatic potential based method using charge restraints for deriving atomic charges: the RESP model. J. Phys. Chem. 1993; 97:10269–10280. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Singh U.C., Kollman P.A.. An approach to computing electrostatic charges for molecules. J. Comput. Chem. 1984; 5:129–145. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Besler B.H., Merz K.M. Jr, Kollman P.A.. Atomic charges derived from semiempirical methods. J. Comput. Chem. 1990; 11:431–439. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Dupradeau F.-Y., Pigache A., Zaffran T., Savineau C., Lelong R., Grivel N., Lelong D., Rosanski W., Cieplak P.. The R.E.D. tools: advances in RESP and ESP charge derivation and force field library building. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2010; 12:7821–7839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Cieplak P., Cornell W.D., Bayly C., Kollman P.A.. Application of the multimolecule and multiconformational RESP methodology to biopolymers: charge derivation for DNA, RNA, and proteins. J. Comput. Chem. 1995; 16:1357–1377. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Sanner M.F., Olson A.J., Spehner J.-C.. Reduced surface: an efficient way to compute molecular surfaces. Biopolymers. 1996; 38:305–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Connolly M.L. Analytical molecular surface calculation. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 1983; 16:548–558. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Aduri R., Psciuk B.T., Saro P., Taniga H., Schlegel H.B., SantaLucia J.. AMBER force field parameters for the naturally occurring modified nucleosides in RNA. J. Chem. Theor. Comput. 2007; 3:1464–1475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Chirlian L.E., Francl M.M.. Atomic charges derived from electrostatic potentials: a detailed study. J. Comput. Chem. 1987; 8:894–905. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Barca G.M.J., Bertoni C., Carrington L., Datta D., De Silva N., Deustua J.E., Fedorov D.G., Gour J.R., Gunina A.O., Guidez E.et al.. Recent developments in the general atomic and molecular electronic structure system. J. Chem. Phys. 2020; 152:154102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Betz R.M., Walker R.C.. Paramfit: automated optimization of force field parameters for molecular dynamics simulations. J. Comput. Chem. 2015; 36:79–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Weiner S.J., Kollman P.A., Case D.A., Singh U.C., Ghio C., Alagona G., Profeta S., Weiner P.. A new force field for molecular mechanical simulation of nucleic acids and proteins. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1984; 106:765–784. [Google Scholar]

- 46. Darden T., York D., Pedersen L.. Particle mesh Ewald: an N log (N) method for Ewald sums in large systems. J. Chem. Phys. 1993; 98:10089–10092. [Google Scholar]

- 47. Zgarbová M., Otyepka M., Sponer J., Mládek A., Banás P., Cheatham T.E. III, Jurecka P.. Refinement of the Cornell et al nucleic acids force field based on reference quantum chemical calculations of glycosidic torsion profiles. J. Chem. Theor. Comput. 2011; 7:2886–2902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Zgarbová M., Sponer J., Otyepka M., Cheatham T.E. III, Galindo-Murillo R., Jurecka P.. Refinement of the sugar–phosphate backbone torsion beta for AMBER force fields improves the description of Z- and B-DNA. J. Chem. Theor. Comput. 2015; 11:5723–5736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Schofield P., Taylor A.I., Rihon J., Martinez C.D.P., Zinn S., Mattelaer C.-A., Jackson J., Dhaliwal G., Schepers G., Herdewijn P.et al.. Characterization of an HNA aptamer suggests a non-canonical G-quadruplex motif. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023; 51:7736–7748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Kräutler V., Van Gunsteren W.F., Hünenberger P.H.. A fast SHAKE algorithm to solve distance constraint equations for small molecules in molecular dynamics simulations. J. Comput. Chem. 2001; 22:501–508. [Google Scholar]

- 51. Davidchack R.L., Handel R., Tretyakov M.. Langevin thermostat for rigid body dynamics. J. Chem. Phys. 2009; 130:234101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Berendsen H.J., Postma J.V., van Gunsteren W.F., DiNola A., Haak J.R.. Molecular dynamics with coupling to an external bath. J. Chem. Phys. 1984; 81:3684–3690. [Google Scholar]

- 53. Roe D.R., Cheatham T.E. III. PTRAJ and CPPTRAJ: software for processing and analysis of molecular dynamics trajectory data. J. Chem. Theor. Comput. 2013; 9:3084–3095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Salomon-Ferrer R., Gotz A.W., Poole D., Le Grand S., Walker R.C.. Routine microsecond molecular dynamics simulations with AMBER on GPUs. 2. Explicit solvent particle mesh Ewald. J. Chem. Theor. Comput. 2013; 9:3878–3888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Le Grand S., Goetz A.W., Walker R.C.. SPFP: speed without compromise—a mixed precision model for GPU accelerated molecular dynamics simulations. Comput. Phys. Commun. 2013; 184:374–380. [Google Scholar]

- 56. Humphrey W., Dalke A., Schulten K.. VMD: visual molecular dynamics. J. Mol. Graph. 1996; 14:33–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Pettersen E.F., Goddard T.D., Huang C.C., Couch G.S., Greenblatt D.M., Meng E.C., Ferrin T.E.. UCSF Chimera—a visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J. Comput. Chem. 2004; 25:1605–1612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Vanquelef E., Simon S., Marquant G., Garcia E., Klimerak G., Delepine J.C., Cieplak P., Dupradeau F.-Y.. R.E.D. Server: a web service for deriving RESP and ESP charges and building force field libraries for new molecules and molecular fragments. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011; 39:W511–W517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Sychrovsky V., Foldynova-Trantirkova S., Spackova N., Robeyns K., Van Meervelt L., Blankenfeldt W., Vokacova Z., Sponer J., Trantirek L.. Revisiting the planarity of nucleic acid bases: pyramidilization at glycosidic nitrogen in purine bases is modulated by orientation of glycosidic torsion. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009; 37:7321–7331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Zierkiewicz W., Komorowski L., Michalska D., Cerny J., Hobza P.. The amino group in adenine: MP2 and CCSD(T) complete basis set limit calculations of the planarization barrier and DFT/B3LYP study of the anharmonic frequencies of adenine. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2008; 112:16734–16740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Davis R.R., Shaban N.M., Perrino F.W., Hollis T.. Crystal structure of RNA–DNA duplex provides insight into conformational changes induced by RNase H binding. Cell Cycle. 2015; 14:668–673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Maiti M., Siegmund V., Abramov M., Lescrinier E., Rosemeyer H., Froeyen M., Ramaswamy A., Ceulemans A., Marx A., Herdewijn P.. Solution structure and conformational dynamics of deoxyxylonucleic acids (dXNA): an orthogonal nucleic acid candidate. Chem. Eur. J. 2011; 18:869–879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Ramaswamy A., Froeyen M., Herdewijn P., Ceulemans A.. Helical structure of xylose–DNA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009; 132:587–595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Ramaswamy A., Smyrnova D., Froeyen M., Maiti M., Herdewijn P., Ceulemans A.. Molecular dynamics of double stranded xylo-nucleic acid. J. Chem. Theor. Comput. 2017; 13:5028–5038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Lescrinier E., Esnouf R., Schraml J., Busson R., Heus H., Hilbers C., Herdewijn P.. Solution structure of a HNA–RNA hybrid. Chem. Biol. 2000; 7:719–731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Wang J., Wolf R.M., Caldwell J.W., Kollman P.A., Case D.A.. Development and testing of a general amber force field. J. Comput. Chem. 2004; 25:1157–1174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Zhang C., Lu C., Wang Q., Ponder J.W., Ren P.. Polarizable multipole-based force field for dimethyl and trimethyl phosphate. J. Chem. Theor. Comput. 2015; 11:5326–5339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. IUPAC–IUB Joint Commission on Biochemical Nomenclature (JCBN) Abbreviations and symbols for the description of conformations of polynucleotide chains. Eur. J. Biochem. 1983; 131:9–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Saenger W. Structures and conformational properties of bases, furanose sugars, and phosphate groups. Principles of Nucleic Acid Structure. Springer Advanced Texts in Chemistry. 1984; NY:Springer; 51–104. [Google Scholar]

- 70. Zhang W., Pal A., Ricardo A., Szostak J.W.. Template-directed nonenzymatic primer extension using 2-methylimidazole-activated morpholino derivatives of guanosine and cytidine. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019; 141:12159–12166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Langner H.K., Jastrzebska K., Caruthers M.H.. Synthesis and characterization of thiophosphoramidate morpholino oligonucleotides and chimeras. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020; 142:16240–16253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Eschenmoser A. Luisi P.L., Chiarabelli C.. Searching for nucleic acid alternatives. Chemical Synthetic Biology. 2011; Wiley Inc; 5–45. [Google Scholar]

- 73. Nikolova E.N., Kim E., Wise A.A., O’Brien P.J., Andricioaei I., Al-Hashimi H.M.. Transient Hoogsteen base pairs in canonical duplex DNA. Nature. 2011; 470:498–502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Vreede J., de Alba Ortíz A.P., Bolhuis P.G., Swenson D.W.H.. Atomistic insight into the kinetic pathways for Watson–Crick to Hoogsteen transitions in DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019; 47:11069–11076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Egli M., Pallan P.S., Pattanayek R., Wilds C.J., Lubini P., Minasov G., Dobler M., Leumann C.J., Eschenmoser A.. Crystal structure of homo-DNA and nature's choice of pentose over hexose in the genetic system. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006; 128:10847–10856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this article are available in ModelArchive, at https://www.modelarchive.org/doi/10.5452/ma-qaldv. The source code of the Ducque model software is available in Figshare at DOI: 10.6084/m9.figshare.24184158.