Abstract

The Internet is a key source of health information, yet little is known about resources for low-risk thyroid cancer treatment. We examined the timeliness, content, quality, readability, and reference to the 2015 American Thyroid Association (ATA) guidelines in websites about thyroid cancer treatment. We identified the top 60 websites using Google, Bing, and Yahoo for “thyroid cancer.” Timeliness and content analysis identified updates in the ATA guidelines (n = 6) and engaged a group of stakeholders to develop essential items (n = 29) for making treatment decisions. Website quality and readability analysis used 4 validated measures: DISCERN; Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) benchmark criteria; Health on the Net Foundation certification (HONcode); and the Suitability Assessment of Materials (SAM) method. Of the 60 websites, 22 were unique and investigated. Content analysis revealed zero websites contained all updates from the ATA guidelines and rarely (18.2%) referenced them. Only 31.8% discussed all 3 treatment options: total thyroidectomy, lobectomy, and active surveillance. Websites discussed 28.2% of the 29 essential items for making treatment decisions. Quality analysis with DISCERN showed “fair” scores overall. Only 29.9% of the JAMA benchmarks were satisfied, and 40.9% were HONcode certified. Readability analysis with the SAM method found adequate readability, yet 90.9% scored unsuitable in literacy demand. The overall timeliness, content, quality, and readability of websites about low-risk thyroid cancer treatment is fair and needs improvement. Most websites lack updates from the 2015 ATA guidelines and information about treatment options that are necessary to make informed decisions.

Keywords: Thyroid Cancer, Internet resources, Shared decision-making, American Thyroid Association, DISCERN, Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) benchmark criteria, Health on the Net Foundation certification (HONcode), Suitability Assessment of Materials (SAM)

Introduction

In the USA, thyroid cancer is one of the most common cancers of women ages 20–49 [1]. The overall 5-year survival rate for all patients is excellent at 98.2% [2]. Patients with low-risk thyroid cancer have an even better prognosis as well as multiple treatment options with varying tradeoffs patients must weigh [3, 4]. The treatment options for low-risk thyroid cancer changed in 2015 with updated American Thyroid Association (ATA) guidelines and can include total thyroidectomy, thyroid lobectomy (removing half of the thyroid), or active surveillance depending on tumor size and other clinical characteristics [5]. For patients who have multiple preference-sensitive treatment options like these, having adequate evidence-based information to support decision-making is critical [6].

The Internet is a common source of information for many patients, particularly younger patients [7–9]. Data show that over 70% of Americans who use the Internet search for health-related information and the proportion of Internet users continues to increase [10, 11]. Previous studies demonstrate that websites about thyroid cancer need improvement [12–14]. However, these studies have not evaluated whether online information about treatment options for low-risk cancer is (1) up to date with the recent guideline changes or (2) contains information important for treatment decision-making. To make well-informed decisions and participate in shared decision-making, patients need access to high quality, comprehensive, and up to date disease-related information [4, 6, 15].

Our preliminary work revealed that many patients with low-risk thyroid cancer are not aware of all of their treatment options even after searching the Internet. This observation suggests that current Internet resources about thyroid cancer treatment options may not provide up to date information or incorporate the 2015 ATA guidelines. Therefore, the aim of this study was to evaluate the timeliness and content of online information about low-risk thyroid cancer treatment. We also sought to evaluate the quality and readability of websites. Collection of these data will allow us to identify weaknesses in information sources on the Internet and improve the quality of treatment-related information available to patients with low-risk thyroid cancer. Filling this gap will help patients make more informed decisions about treatment and align their treatment choice with their preferences and values.

Methods

We used the search engines Google ™, Bing ™, and Yahoo!™ to search the term “thyroid cancer” and identify websites that patients would most likely use to obtain information about thyroid cancer treatment. We selected these sites because they are the most commonly used search engines in the USA [10]. To identify the search term “thyroid cancer,” we surveyed patients with low and intermediate-risk thyroid cancer seen in an Endocrine Surgery clinic and asked what search term they did or would use to obtain more information about their diagnosis. Of the patients, 100% reported they would use Google ™ to search the term “thyroid cancer.” We then identified the top 60 websites generated on the first 2 pages of results from each search engine. We limited the results to the first 2 pages because data show that 91% of people do not click past in the first results page, which typically generates 10 websites per page [8]. We also added the term “treatment” to the search but did not identify additional unique sites. We excluded duplicate websites, sites whose information was not original or unique to that website, non-English language websites, and Wikipedia (Fig. 1). Each website was then evaluated independently by two medical professionals, and scores were compared. Any discrepancies were discussed by the study team and resolved by consensus. All searches were performed in October 2017. This study was deemed exempt by the University of Wisconsin Institutional Review Board because it analyzed publicly available data.

Fig. 1.

Algorithm for selection of websites evaluated

Websites were also categorized into four types in accordance with the published literature [12–14, 16–26]. Hospital-affiliated websites were those sites associated with specific hospitals, hospital systems, or groups of hospitals that developed a single website. Commercial websites were those sites that included private practices or other web-based institutions that included advertisements. Nonprofit websites were those of societies or associations that discussed various thyroid diseases. Lastly, government websites included the NIH and public libraries.

Assessment of Website Timeliness and Content

To assess the timeliness and content of the online information, we identified relevant changes in the 2015 ATA guidelines and engaged a group of stakeholders (n = 16) that consisted of patients with thyroid cancer, their family members, endocrinologists, thyroid surgeons, and a radiologist specializing in thyroid ultrasound. Using a process of consensus decision-making, we developed a list of 29 items that are essential for patients and their families to know and understand when deciding about treatment for low-risk thyroid cancer. The items, listed in Table 1, were then categorized into 5 domains: (1) total thyroidectomy, (2) thyroid lobectomy, (3) active surveillance, (4) thyroid hormone, and (5) other. Overall, 6 items that represented changes from the 2015 ATA guidelines are italicized and marked with an Asterisk (*) in Table 1.

Table 1.

Analysis of website content about treatment for low-risk thyroid cancer

| Topics considered by stakeholders to be necessary for treatment decision-making | N (%) |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Total thyroidectomy (TT) a treatment option | 22 (100.0) |

| Only appropriate for select ≤ 1-cm cancers* | 1 (4.5) |

| Complications include permanent voice problems | 7 (31.8) |

| Complications include permanent hypocalcemia | 6 (27.3) |

| Describes symptoms of hypocalcemia | 4 (18.2) |

| Follow-up US and labs are needed to monitor for recurrence | 3 (13.6) |

| All patients require lifelong thyroid hormone replacement | 14 (63.6) |

| Lobectomy is a treatment option | 18 (81.8) |

| Recommended treatment for low-risk cancer ≤ 1 cm* | 5 (22.7) |

| Appropriate for low-risk cancer up to 4 cm* | 2 (9.1) |

| Lower recurrent nerve injury rate than TT | 5 (22.7) |

| Lower complication rate than TT | 2 (9.1) |

| Follow-up US and labs are needed to monitor for recurrence | 9 (40.9) |

| Possible to need lifelong thyroid hormone replacement | 8 (36.4) |

| Possible to need a completion thyroidectomy | 1 (4.5) |

| Active surveillance is a management option* | 8 (36.4) |

| Appropriate for cancer ≤ 1 cm or very low risk* | 3 (13.6) |

| Requires serial surveillance US* | 1 (4.5) |

| Avoids the possible complications of surgery | 3 (13.6) |

| Surgery is possible later if the cancer increases in size or spreads | 3 (13.6) |

| Some patients do eventually undergo surgery | 0 (0) |

| No difference in survival at 10 years compared to surgery | 1 (4.5) |

| Thyroid hormone suppression may be needed | 13 (59.1) |

| Follow-up labs are needed to monitor thyroid hormone levels | 9 (40.9) |

| Discusses possible side effects of thyroid hormone replacement | 4 (18.2) |

| Provides instructions for taking thyroid hormone | 3 (13.6) |

| Other | |

| Discusses radioactive iodine as a potential treatment | 21 (95.5) |

| References any guidelines for thyroid cancer treatment | 4 (18.2) |

| States many people have undiagnosed small thyroid cancer without clinical significance | 0 (0) |

The 6 italicized statements represent changes in treatment recommendations from the 2009 to the 2015 American Thyroid Association (ATA) guidelines

TT total thyroidectomy, US ultrasound

Assessment of Website Quality

To assess the quality of the websites, we used three methods: the DISCERN questionnaire, The Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) benchmark criteria, and The Health on the Net Foundation Code of Conduct (HONcode) [9].

The DISCERN Instrument

This validated instrument assesses the quality of written material on treatment choices for consumer health information and was developed by a panel of 15 experts with diverse backgrounds including clinical specialists [27]. DISCERN contains 16 questions within three categories that evaluate the reliability of the website, quality of information provided on treatment choices, and overall ranking. For each website, we scored the questions 0–5 and calculated the mean score to provide an overall assessment of website quality. A score of 1–2 represented poor quality, 3 fair, and 4–5 good quality.

JAMA Benchmark Criteria

The JAMA benchmarks also represent a validated tool that uses 7 different criteria to assess authorship, attribution, currency of the data, and disclosures for each website [28]. For assessment of authorship, up to 3 points were awarded, 1 for each of the following 3 criteria: Does the website appropriately state the (1) authors and contributors, (2) authors’ affiliations, and (3) credentials of authors and contributors? For attribution, 1 point was awarded if the content was effectively referenced throughout the website. Up to 2 points were awarded for currency, 1 for each of the following questions: Do the website developers provide dates when content is (1) posted and (2) updated? Finally, for disclosure, 1 point was awarded if the website mentions presence or lack of conflict of interest. Each website could achieve a maximum score of 7; the number of criteria met was reported as a percentage.

Health on Net (HONcode) Certification

The HONcode was established by the Health on the Net Foundation, a nongovernmental organization that assesses ethical content of human health information on the Internet [29]. Certification indicates a website meets an ethical standard and contains quality health information available to the general public, health professionals, and web publishers. HONcode certification is based on eight principles: authority, complementarity, confidentiality, attribution, justifiability, transparency, financial disclosure, and advertising. Each website was identified as either being HONcode certified or not certified.

Assessment of Website Readability

To assess readability, we utilized the Suitability Assessment of Materials (SAM) instrument, a validated tool developed to score patient education materials [30]. SAM evaluates 22 different criteria within 6 categories: content, literacy demand, graphics, layout and topography, learning stimulation and motivation, and cultural appropriateness. The individual criteria within these categories are outlined in Table 2. Each category was given a score from 0 to 2: 0 representing not suitable, 1 adequate, and 2 superior. Within the category of literacy demand, the Flesch-Kincaid formula identified beginner reading level as 4th grade. A superior score (of 2) was given to websites written at a 5th grade reading level or below, an adequate score (of 1) for those at a 6th to 8th grade level, and not suitable score (of 0) for sites at a 9th grade level or above. For each website, we calculated the percentage of total possible points earned in each category. A website was considered superior if it achieved 70–100% of the total points, adequate for 40–69%, and not suitable as 0–39%.

Table 2.

Summary of the Suitability Assessment of Materials (SAM) scores of websites with respect to treatment of low-risk thyroid cancer

| Categories (criteria within categories) | Mean score ± SD |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Content | 58.5% ± 19.4 |

| (Purpose, Content topics, Scope, Summary, and Review) | |

| Literacy demand | 60.5% ± 16.5 |

| (Reading grade level, Writing style, Sentence construction, Vocabulary, Learning enhanced by advance organizers) | |

| Graphic illustrations, lists, tables, charts | 20.9% ± 29.3 |

| (Cover graphic, Types of illustrations, Relevance of illustrations, Graphics, Captions) | |

| Layout and typography | 83.3% ± 16.3 |

| (Typography, Layout, Subheadings, and “Chunking”) | |

| Learning stimulation and motivation | 50.0% ± 29.1 |

| (Interactions included in text/graphics, Desired behavior patterns modeled, Motivation) | |

| Cultural appropriateness | 77.3% ± 10.7 |

| (Cultural Match – Logic/Language/Experience, Cultural image, and examples) | |

| Average total percentage | 65.0% ± 12.5 |

Results

Of the 60 websites identified with our search strategy, 22 were unique and analyzed (Fig. 1; Appendix A). In total, 8 (36.4%) were hospital affiliated, 7 (31.8%) were commercial, 5 (22.7%) were non-profit, and 2 (9.1%) were governmental websites. Analysis of website timeliness and content related to treatment options for low-risk thyroid cancer revealed that no website contained information about all six updates from the 2015 ATA guidelines (Table 1). Overall, 5 (22.7%) websites reported the guideline change that lobectomy is the recommended treatment if surgery is chosen for low-risk tumors ≤ 1 cm, while only 2 (9.1%) websites discussed that lobectomy is appropriate for low-risk cancer up to 4 cm. Only 1 (4.5%) website discussed that total thyroidectomy is only appropriate for cancers ≤ 1 cm when the risk of recurrence is high. In addition, of the 8 websites that discussed active surveillance (36.4%), only 3 (13.6%) specified that surveillance is only an option for ≤ 1-cm low-risk tumors, and only 1 (4.5%) website described that active surveillance involves monitoring with serial ultrasound exams. Overall, only 4 (18.2%) websites referenced any treatment guidelines, specifically the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) or the 2015 ATA guidelines.

Additional analysis of website content that is important for treatment decision-making revealed that only 7 (31.8%) websites discussed all 3 primary treatment options for patients with low-risk thyroid cancer—total thyroidectomy, lobectomy, and active surveillance—while all 22 websites (100%) discussed total thyroidectomy, 18 (81.8%) discussed thyroid lobectomy, and only 8 (36.4%) discussed active surveillance. Overall, few sites discussed complications, compared outcomes between treatment options, or provided details about thyroid hormone. Examination of the content stakeholders determined is essential for patients to make an informed treatment decision revealed that websites contained an average of only 28.2% of the essential items (Table 1).

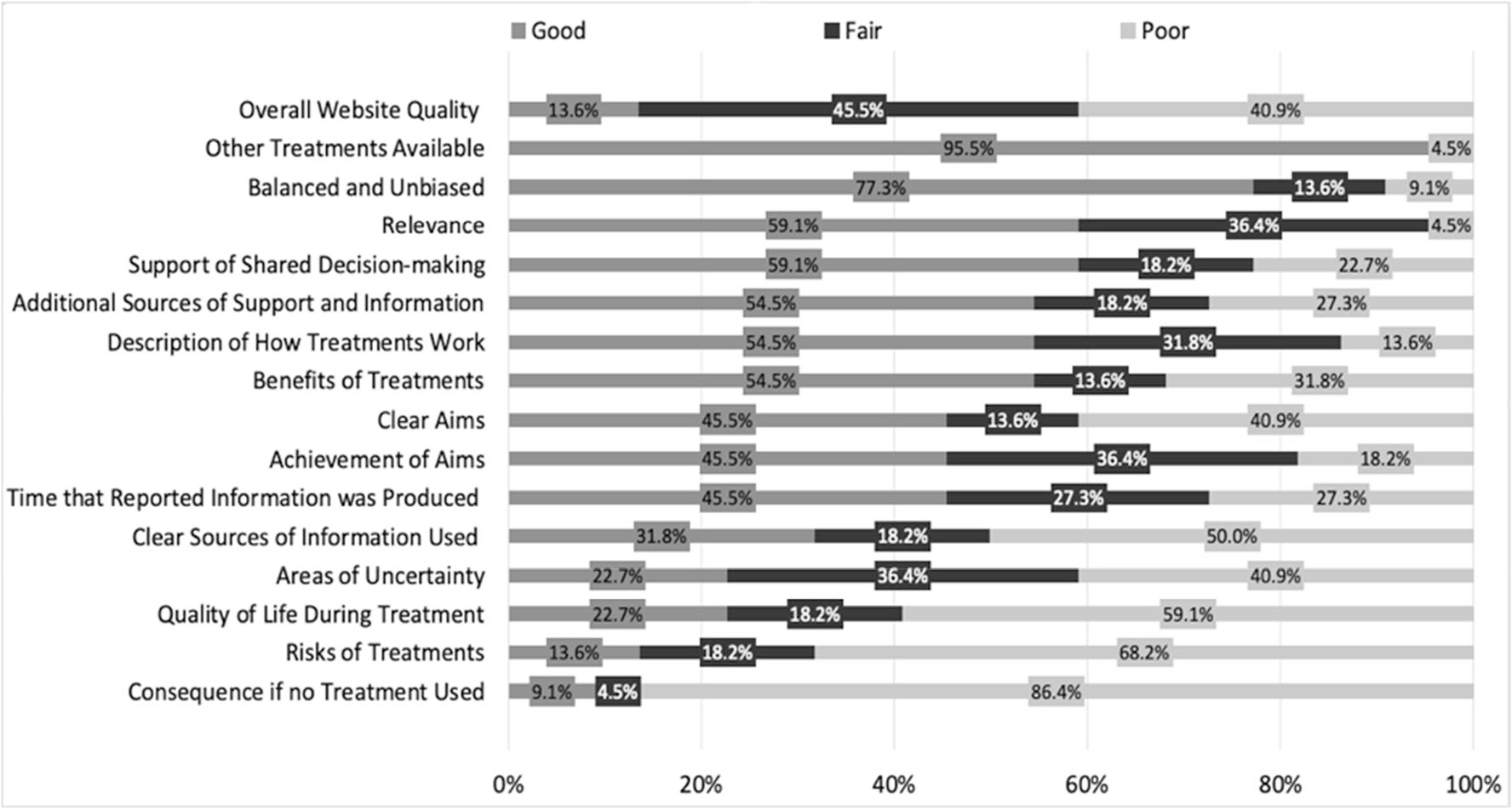

Analysis of website quality overall showed that sites were fair to adequate depending on the measure. The DISCERN instrument revealed that the overall quality of the written information for the websites was fair (mean ± sd score of 3.2 ± 0.6). Three websites (13.6%) met the criteria for good quality, while 10 (45.5%) scored fair, and 9 (40.9%) scored poor. All of the websites that achieved a good score were nonprofit. Figure 2 demonstrates the distribution of DISCERN scores for each of the 16 questions. The majority of websites were good at providing balanced and unbiased material, having relevance, identifying additional sources of support and information, and describing both the treatment itself and the benefits of treatment. However, most sites were poor at discussing the consequences of no treatment, the risks of treatment, quality of life, areas of uncertainty, and the sources of information.

Fig. 2.

Distribution of DISCERN for each of the 16 questions

Further analysis of website quality using the JAMA benchmark criteria demonstrated that the average number of criteria met was 2.1 out of 7 (29.9%) with a range from 0 to 5 (0–71.4%). No single site met all of the 7 JAMA benchmarks. Websites met 25.7% of authorship benchmarks, 9.1% of attribution benchmarks, 52.3% of currency benchmarks, and 18.2% included disclosures (Fig. 3). HONCode certification was identified in less than half (40.9%) of websites (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

JAMA benchmark criteria met and HON Code certification identified

Lastly, assessment of website readability using the SAM instrument demonstrated the mean score of all websites was 28.6 ± 6.5 out of 44 total possible points (65.0%), corresponding to an adequate readability. Most websites (n = 17) were considered to be adequate (40–69% of total points), while 3 were superior (70–100% of total points), and 2 were not suitable (0–39% of total points). The percentage of criteria met in each of the 6 SAM categories ranged from lowest in graphics (20.9%) to highest (83.3%) in layout and typography. Within the literacy demand category, no website achieved a superior score (< 5th grade reading level), while only 2 websites (9.1%) scored adequate (6–8th grade reading level), and the remaining 20 websites (90.9%) scored not suitable (> 9th grade reading level). Table 2 summarizes the SAM results.

Discussion

This study demonstrates that there is an overwhelming need for improvement in the timeliness, content, quality, and readability of health-related information about treatment options for low-risk thyroid cancer. Specifically, many sites do not include all possible treatment options or information that is key for decision-making. Websites are also often out of date or written at a level that is difficult for patients to comprehend. These findings are consistent with the literature examining health information on the Internet which often reveals that there is significant room for improvement [12–14, 16–26, 31].

One major area where the online content about treatment for low-risk thyroid cancer can be improved is the incorporation of updated practice guidelines. Not a single website in our analysis discussed all 6 of the updates we examined from the 2015 ATA guidelines. Patients obtain information from several sources including their physicians, family, friends, brochures or other printed information, and the Internet. In order to make an informed decision, patients must have access to the most up to date recommendations. We performed this analysis nearly 2 years after the ATA guidelines were published, yet few websites contained updated information or referenced their updates. In addition, most did not reference any guidelines. An updated review of the same websites performed in October 2019 showed there have been no new updates added and no further references to the guidelines. To the best of our knowledge, there are no data available describing the length of time it takes for guidelines to reach online patient education materials, but data do show that dissemination and implementation of guidelines into providers’ practice can take several years [32–34]. A quicker, more efficient process is needed to ensure timely dissemination of guideline changes to patient resources.

In addition to lacking critical content related to guidelines, the quality of websites on treatment for low-risk thyroid cancer needs improvement. This finding is not surprising given that the quality of health-related information on the Internet is lacking for many disease processes [14, 16–20, 24, 25, 35, 36]. These studies report similar findings of predominately fair or poor DISCERN scores [16, 17, 24, 36], incorporation of few JAMA benchmark criteria [16, 17, 24], and low representation of the HONCode certificate [16, 17, 19, 24]. With respect to literature on thyroid cancer website quality, studies published a decade ago reported that websites were outdated and lacked quality [12, 13]. At that time, about half of the websites were private industry or physician sponsored and indicated authorship [13]. Our more recent analysis shows quality has not improved and may have even declined. Nearly a third of websites in the current analysis were commercial sites, and just over a third identified authors of any kind who were not necessarily medical professionals. In terms of currency, just over half of websites in our study included when the content was updated or posted. These findings are similar to other recent studies about online health information [14, 16, 19, 24, 35, 36]. The lack of transparency in sources, authorship, and currency is problematic because patients may be relying on information that is out of date and/or unreliable.

Another area where websites fell short of benchmarks was with respect to readability. Many adults have poor health literacy; thus, it is vital that resources containing healthcare information be written at an appropriate reading level [23, 37, 38]. The American Medical Association, among other authors, recommends that patient-directed education materials be written at or below a 6th grade reading level [30, 39]. Several studies have reported that the readability of websites for various other medical conditions is poor [17, 18, 20, 23, 25, 26], including websites about benign thyroid conditions [22, 31], which is consistent with our findings. Almost all websites in our analysis presented material at a reading level that was higher than the recommended 6th grade level. Therefore, websites need to evaluate and adjust their literacy burden to be more accessible and comprehensible to the general population.

There are some limitations to this study. The information that the average patient may feel is important to extract from a website about treatment for low-risk thyroid cancer may not be the same as a provider or a patient who experienced thyroid cancer treatment already. Additionally, the survey instruments used in this study may be more rigorous than a given patient’s personal evaluation. Furthermore, patients’ evaluations may vary based on their educational level and geographic area. Thus, patients may not interpret the overall quality of websites the same as the reviewers. Finally, our search strategy may have missed important websites used by patients. However, this intentional strategy was designed to mimic a typical patient’s search behavior. Over 90% of people do not click past the first page of search results [8].

Conclusion

In summary, websites about low-risk thyroid cancer treatment fall far short of standards with respect to all areas we assessed—timeliness, content, quality, and readability. Most sites lack critical information necessary for patients to make treatment decisions including listing all available treatment options, complications of treatment, anticipated follow-up, and postoperative management with thyroid hormone replacement. Most sites are not up to date with respect to changes in treatment guidelines made by the ATA in 2015. Moving forward, we must advocate for improvement in online resources about thyroid cancer treatment to ensure that information available to patients is accurate, up to date, comprehensive, and of value. Low-risk thyroid cancer is common, increasing in incidence, and many reasonable treatment options exist which increases decision complexity and the need for shared decision-making [4, 6, 40]. Improving the quality of information readily available to patients outside of encounters with medical professionals will increase knowledge about treatment options and outcomes while facilitating shared decisions that align patients’ treatment choices with their goals and values.

Footnotes

References

- 1.Ward E et al. (2019) Annual Report to the Nation on the Status of Cancer, 1999–2015, Featuring Cancer in men and women ages 20–49. J Natl Cancer Inst [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cancer Stat Facts: Thyroid Cancer (2019) SEER: National Cancer Institute. [cited 2019 July]; Available from: https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/thyro.html [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fitch K, Bazell C, Dehipawala S (2018) Preference-sensitive surgical procedures for preference-sensitive conditions: Is there opportunity to reduce variation in utilization? September, 2018 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pitt SC, Lubitz CC (2017) Editorial: complex decision making in thyroid cancer: costs and consequences-is less more? Surgery 161(1):134–136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Haugen BR, Alexander EK, Bible KC, Doherty GM, Mandel SJ, Nikiforov YE, Pacini F, Randolph GW, Sawka AM, Schlumberger M, Schuff KG, Sherman SI, Sosa JA, Steward DL, Tuttle RM, Wartofsky L (2016) 2015 American Thyroid Association management guidelines for adult Patients with thyroid nodules and differentiated thyroid cancer: the American Thyroid Association guidelines task force on thyroid nodules and differentiated thyroid cancer. Thyroid 26(1):1–133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Woolf SH, Chan EC, Harris R, Sheridan SL, Braddock CH 3rd, Kaplan RM, Krist A, O’Connor AM, Tunis S (2005) Promoting informed choice: transforming health care to dispense knowledge for decision making. Ann Intern Med 143(4):293–300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rowlands IJ, Loxton D, Dobson A, Mishra GD (2015) Seeking health information online: association with young Australian women’s physical, mental, and reproductive health. J Med Internet Res 17(5):e120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.van Deursen AJAM, van Dijk JAGM (2009) Using the internet: skill related problems in users’ online behavior. Interact Comput 21(5–6):393–402 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fahy E, Hardikar R, Fox A, Mackay S (2014) Quality of patient health information on the internet: reviewing a complex and evolving landscape. Australas Med J 7(1):24–28 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fox S DM (2013) Health Online 2013. [cited 2017 November]; Internet and Technology:[The Pew Internet & American Life Project; ]. Available from: https://www.pewinternet.org/2013/01/15/health-online-2013/ [Google Scholar]

- 11.McDow AD, Pitt S (2019) Extent of surgery for Low-risk differentiated thyroid Cancer. Surg Clin North Am 99(4):599–610 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Air M, Roman SA, Yeo H, Maser C, Trapasso T, Kinder B, Sosa JA (2007) Outdated and incomplete: a review of thyroid cancer on the world wide web. Thyroid 17(3):259–265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yeo H et al. (2007) Filling a void: thyroid cancer surgery information on the internet. World J Surg 31(6):1185–1191 discussion 1192–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chang KL, Grubbs EG, Ingledew PA (2019) An analysis of the quality of thyroid cancer websites. Endocr Pract [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tan SS, Goonawardene N (2017) Internet health information seeking and the patient-physician relationship: a systematic review. J Med Internet Res 19(1):e9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bruce-Brand RA, Baker JF, Byrne DP, Hogan NA, McCarthy T (2013) Assessment of the quality and content of information on anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction on the internet. Arthroscopy 29(6):1095–1100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Clancy AA, Hickling D, Didomizio L, Sanaee M, Shehata F, Zee R, Khalil H (2018) Patient-targeted websites on overactive bladder: what are our patients reading? Neurourol Urodyn 37(2):832–841 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.De Groot L et al. (2019) Quality of online resources for pancreatic Cancer Patients. J Cancer Educ 34(2):223–228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fast AM et al. (2012) Partial nephrectomy online: a preliminary evaluation of the quality of health information on the Internet. BJU Int 110(11 Pt B):E765–E769 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kobes K, Harris IB, Regehr G, Tekian A, Ingledew PA (2018) Malignant websites? Analyzing the quality of prostate cancer education web resources. Can Urol Assoc J 12(10):344–350 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kuenzel U, Monga Sindeu T, Schroth S, Huebner J, Herth N (2018) Evaluation of the quality of online information for patients with rare cancers: thyroid Cancer. J Cancer Educ 33(5):960–966 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Purdy AC, Idriss A, Ahern S, Lin E, Elfenbein DM (2017) Dr Google: the readability and accuracy of patient education websites for Graves’ disease treatment. Surgery 162(5):1148–1154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rhee RL, von Feldt J, Schumacher HR, Merkel PA (2013) Readability and suitability assessment of patient education materials in rheumatic diseases. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 65(10):1702–1706 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Roughead T, Sewell D, Ryerson CJ, Fisher JH, Flexman AM (2016) Internet-based resources frequently provide inaccurate and out-of-date recommendations on preoperative fasting: a systematic review. Anesth Analg 123(6):1463–1468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Storino A, Castillo-Angeles M, Watkins AA, Vargas C, Mancias JD, Bullock A, Demirjian A, Moser AJ, Kent TS (2016) Assessing the accuracy and readability of online health information for patients with pancreatic cancer. JAMA Surg 151(9):831–837 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tian C, Champlin S, Mackert M, Lazard A, Agrawal D (2014) Readability, suitability, and health content assessment of web-based patient education materials on colorectal cancer screening. Gastrointest Endosc 80(2):284–290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Charnock D, Shepperd S, Needham G, Gann R (1999) DISCERN: an instrument for judging the quality of written consumer health information on treatment choices. J Epidemiol Commun Health 53:105–111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Silberg WM, Lundberg GD, Musacchio RA (1997) Assessing, controlling, and assuring the quality of medical information on the internet: Caveant lector et viewor–let the reader and viewer beware. Jama 277(15):1244–1245 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Foundation H.o.t.N. (2017) HON code of conduct (HONcode) for medical and health. May 2, [cited 2017 November]; Available from: https://www.hon.ch/HONcode/Conduct.html

- 30.Doak CC, Doak LG, Root JH (1996) Teaching Patients with Low Literacy Skills, 2nd edn. J. B. Lippincott Company, Philadelphia [Google Scholar]

- 31.Barnes JA, Davies L (2015) Reading grade level and completeness of freely available materials on thyroid nodules: there is work to be done. Thyroid 25(2):147–156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Berdowski J, Schmohl A, Tijssen JG, Koster RW (2009) Time needed for a regional emergency medical system to implement resuscitation guidelines 2005–the Netherlands experience. Resuscitation 80(12):1336–1341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nielsen AM, Isbye DL, Lippert FK (2008) Have the 2005 Guidelines for resuscitation been implemented? Ugeskr Laeger 170(47):3843–3847 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fischer F et al. (2016) Barriers and strategies in guideline implementation-a Scoping review. Healthcare (Basel) 4(3) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Starman JS, Gettys FK, Capo JA, Fleischli JE, Norton HJ, Karunakar MA (2010) Quality and content of internet-based information for ten common orthopaedic sports medicine diagnoses. J Bone Joint Surg Am 92(7):1612–1618 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bruce JG, Tucholka JL, Steffens NM, Neuman HB (2015) Quality of online information to support patient decision-making in breast cancer surgery. J Surg Oncol 112(6):575–580 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Baker DW, Gazmararian JA, Williams MV, Scott T, Parker RM, Green D, Ren J, Peel J (2002) Functional health literacy and the risk of hospital admission among Medicare managed care enrollees. Am J Public Health 92(8):1278–1283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kutner M, Greenberg E, Jin Y, Paulsen C (2006) The health literacy of America’s adults: results from the 2003 National Assessment of Adult Literacy [Google Scholar]

- 39.Weiss B (2009) Health literacy and patient safety: help patients understand. A.M. Association, Editor. Chicago, IL [Google Scholar]

- 40.Braddock CH 3rd et al. (1999) Informed decision making in outpatient practice: time to get back to basics. JAMA 282(24):2313–2320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]