Abstract

Background

Increasingly, counter‐radicalisation interventions are using case management approaches to structure the delivery of tailored services to those at risk of engaging in, or engaged in, violent extremism. This review sets out the evidence on case management tools and approaches and is made up of two parts with the following objectives.

Objectives

Part I: (1) Synthesise evidence on the effectiveness of case management tools and approaches in interventions seeking to counter radicalisation to violence. (2) Qualitatively synthesise research examining whether case management tools and approaches are implemented as intended, and the factors that explain how they are implemented. Part II: (3) Synthesise systematic reviews to understand whether case management tools and approaches are effective at countering non‐terrorism related interpersonal or collective forms of violence. (4) Qualitatively synthesise research analysing whether case management tools and approaches are implemented as intended, and what influences how they are implemented. (5) Assess the transferability of tools and approaches used in wider violence prevention work to counter‐radicalisation interventions.

Search Methods

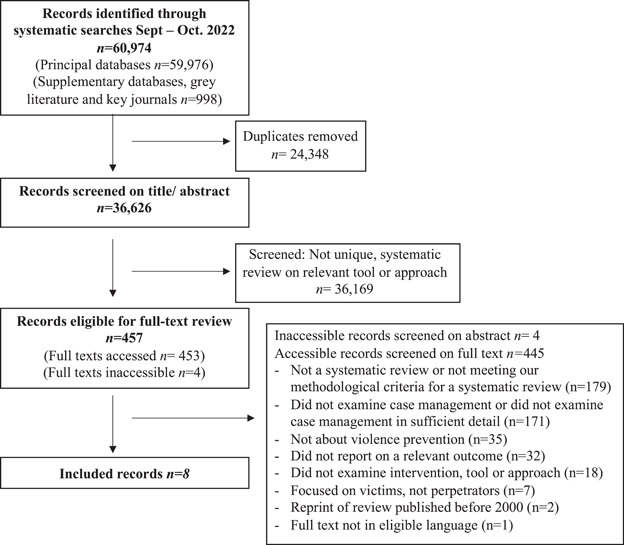

Search terms tailored for Part I and Part II were used to search research repositories, grey literature sources and academic journals for studies published between 2000 and 2022. Searches were conducted in August and September 2022. Forward and backward citation searches and consultations with experts took place between September 2022 and February 2023. Studies in English, French, German, Russian, Swedish, Norwegian and Danish were eligible.

Selection Criteria

Part I: Studies had to report on a case management intervention, tool or approach, or on specific stages of the case management process. Only experimental and stronger quasi‐experimental studies were eligible for inclusion in the analysis of effectiveness. The inclusion criteria for the analysis of implementation allowed for other quantitative designs and qualitative research. Part II: Systematic reviews examining a case management intervention, tool or approach, or stage(s) of the case management process focused on countering violence were eligible for inclusion.

Data Collection and Analysis

Part I: 47 studies were eligible for Part I. No studies met the inclusion criteria for Objective 1; all eligible studies related to Objective 2. Data from these studies was synthesised using a framework synthesis approach and presented narratively. Risk of bias was assessed using the CASP (for qualitative research) and EPHPP (for quantitative research) checklists. Part I: Eight reviews were eligible for Part II. Five reviews met the inclusion criteria for Objective 3, and seven for Objective 4. Data from the studies was synthesised using a framework synthesis approach and presented narratively. Risk of bias was assessed using the AMSTAR II tool.

Findings

Part I: No eligible studies examined effectiveness of tools and approaches. Seven studies examined the implementation of different approaches, or the assumptions underpinning interventions. Clearly defined theories of change were absent, however these interventions were assessed as being implemented in line with their own underlying logic. Forty‐three studies analysed the implementation of tools during individual stages of the case management process, and forty‐one examined the implementation of this process as‐a‐whole. Factors which influenced how individual stages and the case management process as a whole were implemented included strong multi‐agency working arrangements; the inclusion of relevant knowledge and expertise, and associated training; and the availability of resources. The absence of these facilitators inhibited implementation. Additional implementation barriers included overly risk‐oriented logics; public and political pressure; and broader legislation. Twenty‐eight studies identified moderators that shaped how interventions were delivered, including delivery context; local context; standalone interventions; and client challenges. Part II: The effectiveness of two interventions – mentoring and multi‐systemic therapy – in reducing violent outcomes were each assessed by one systematic review, whilst three reviews analysed the impact that the use of risk assessment tools (n = 2) and polygraphs (n = 1) had on outcomes. All these reviews reported mixed results. Comparable factors to those identified in Part I, such as staff training and expertise and delivery context, were found to shape implementation. On the basis of this modest sample, the research on interventions to counter non‐terrorism related violence was assessed to be transferable to counter‐radicalisation interventions.

Authors' Conclusions

The effectiveness of existing case management tools and approaches is poorly understood, and research examining the factors that influence how different approaches are implemented is limited. However, there is a growing body of research on the factors which facilitate or generate barriers to the implementation of case management interventions. Many of the factors and moderators relevant to countering radicalisation to violence also impact how case management tools and approaches used to counter other forms of violence are implemented. Research in this wider field seems to have transferable insights for efforts to counter radicalisation to violence. This review provides a platform for further research to test the impact of different tools, and the mechanisms by which they inform outcomes. This work will benefit from using the case management framework as a way of rationalising and analysing the range of tools, approaches and processes that make up case managed interventions to counter radicalisation to violence.

1. PLAIN LANGUAGE SUMMARY

1.1. Case management tools and approaches are widely used in countering radicalisation to violence programmes, but their effectiveness is unclear

Case management tools and approaches were found to support counter‐radicalisation work when implemented appropriately. No eligible evaluations of effectiveness were identified. Research on tools and approaches used to counter non‐terrorism related violence is more developed, however robust evaluations of effectiveness are largely absent.

1.2. What is this review about?

This review has two parts. Part I is a systematic review of case management tools and approaches used in counter‐radicalisation interventions and has three objectives: (1) assess the effectiveness of tools and approaches; (2a) examine whether they are implemented as intended; and (2b) identify factors that explain this implementation.

Part II is an overview of systematic reviews examining tools and approaches used to counter other forms of violence and has the following objectives: (3) examine the effectiveness of tools and approaches; (4a) assess their implementation; (4b) identify factors that explain their implementation; and (5) analyse whether these tools and approaches are transferable to counter‐radicalisation work.

1.3. What studies are included?

1.3.1. Part I – Countering radicalisation to violence

No eligible studies spoke to Objective 1.

Forty‐seven studies related to Objective 2. Research on Objective 2a (n = 7 studies) focused on approaches. Research on Objective 2b focused on implementation factors pertaining to stages of the case management process (n = 43); and implementation factors (n = 41) and moderators (n = 28) relevant to the full process.

1.3.2. Part II – Countering other forms of violence

Eight reviews were included. Five examined the effectiveness of case management approaches (n = 2) and tools (n = 3) (Objective 3); two examined how tools were implemented (Objective 4a); and seven considered implementation factors and moderators (Objective 4b).

1.4. What are the findings of this review?

1.4.1. Are case management tools and approaches effective in countering radicalisation to violence?

It is not possible to draw conclusions about effectiveness as no eligible studies were identified.

1.4.2. Are case management tools and approaches implemented as intended?

Four studies concluded that the assumptions underpinning three interventions were sound and aligned with academic research. Four studies reported mixed results as to whether three interventions were implemented in line with their internal logic. Two studies highlighted weaknesses in programme logic, including misalignment between activities and intended outcomes.

1.4.3. What explains how tools and approaches are implemented?

Different stages of case management

Two studies examined the identification stage, highlighting how working arrangements with external partners can create challenges when engaging potential clients. Research on the client assessment stage (n = 26 studies) examined multi‐agency assessment (n = 14); risk and needs assessment (RNA) tools (n = 12); and screening tools (n = 3). Themes included inconsistency in tool use; subjectivity in interpreting risk; differing opinions on the utility of tools; and the importance of expertise and experience, and organisational and operational support for assessors. Effective multi‐agency collaboration was important.

Evidence on case planning was limited (n = 5), and it remains unclear whether case planning is informed by client identification and assessment or informs delivery. Research on the use of case planning tools and case conferences identified similar themes to that on client assessment.

Research on the delivery stage (n = 28) highlighted the benefits of tailoring support to client needs, and skilled and committed practitioners who were well matched to clients and able to build trust.

Monitoring and evaluation tools (n = 16) included client assessment tools (n = 9); case file and case note data (n = 7); case conferences (n = 5); and less structured qualitative data (n = 5). Assessment tools were considered able to monitor change, inform evaluations, and support delivery, but were used inconsistently. Case notes and files help capture relevant data, whilst case conferences enable plausibility checking. However, there is limited consensus over how to interpret client change.

Studies examining transition and exit (n = 10) highlighted the importance of inter‐agency coordination and continuity in client support. Potential challenges included reticence to close cases; ending relationships smoothly; and difficulties monitoring clients post‐exit.

Implementation factors and moderators affecting the case management process

Implementation factors and moderators relevant to the whole case management process included effective multi‐agency working (n = 34), potential challenges to which included information sharing and relationships between partners. Staff expertise was a facilitator (n = 23), whilst an over emphasis on risk‐oriented logics (n = 17); political and public pressure (n = 10); and resourcing challenges (n = 17) were identified as implementation barriers. Eight studies highlighted how broader counter‐terrorism legislation might undermine rehabilitative aims.

The benefits of mandated versus voluntary interventions remain unclear (n = 11). Practitioners appear to prefer voluntary approaches, but discussed challenges engaging clients unwilling to participate voluntarily.

Moderators included features of the local context (n = 10) and the delivery context (n = 11); the distinction between standalone counter‐radicalisation work and interventions or practitioners that deliver this alongside other work (n = 4); and the impact of broader challenges in a client's life (n = 4).

1.4.4. Are case management tools and approaches effective at countering interpersonal and collective forms of violence?

The effectiveness of case management in countering other forms of violence remains unclear. Two reviews examining the effectiveness of interventions did not find conclusive evidence that they effectively countered violence. Three reviews on risk assessment tools (n = 2) and polygraphs (n = 1) reported mixed results. However, use of these tools alone would not be expected to directly reduce violence as any positive impact would be indirect.

1.4.5. How are case management tools and approaches implemented in the context of countering collective and interpersonal forms of violence?

Evidence focused almost entirely on risk assessment tools (n = 5). Two reviews found that risk management is not always directly informed by structured risk assessment. The extent to which practitioners use risk assessment tools to inform case planning is informed by their willingness to take risk assessments into account when making decisions, and their ability to offer services that can effectively target needs or risks. Feedback on the perceived utility of these tools was therefore found to be mixed. Whilst feedback on the use of polygraphs was positive, this feedback was drawn from a limited evidence base (n = 1).

Facilitators of risk assessment include the ability to adapt tools to local needs; training and guidance; opportunities to pilot tools; professional ownership; positive relationships with clients; and multi‐disciplinary working. Barriers included uncertainty about the utility of tools; insufficient room for clinical judgement; the perceived complexity and resource intensity of assessment; lack of experience and perceived self‐efficacy; subjective interpretations of risk; and uncertainty around translating assessments into practical action. Expertise, training, and time spent with clients facilitated the implementation of mentoring programmes.

1.4.6. Are case management tools and approaches used to counter other forms of violence transferable to counter‐radicalisation work?

The research in Part II was considered transferable to counter‐radicalisation interventions. Risk assessment tools and mentoring approaches are already widely used within counter‐radicalisation interventions. The utility of using polygraphs has also been considered, however evidence for their effectiveness is insufficient to recommend their implementation. Evidence relating to the use of Multi‐Systemic Therapy (MST) for countering radicalisation to violence was not identified in the literature included in Part I, however its adherence to socio‐ecological models of violence prevention suggests it is potentially transferrable.

1.5. What do the findings of this review mean?

Limited evidence exists for the effectiveness of case management. A body of research (47 studies) has identified factors which can facilitate or generate barriers to the implementation of interventions. The quality of this evidence is uneven. The case management framework provides a useful means of organising research on the different tools. The field will now benefit from research to test the impact of these tools and underlying approaches, and the mechanisms by which they shape intervention outcomes. More detailed analysis of case management in other fields may also strengthen counter‐radicalisation research and practice.

1.6. How up‐to‐date is this review?

Literature searches were completed in January 2023, and include studies first published between 2000 and 2023.

2. BACKGROUND

2.1. The problem, condition or issue

The concept of radicalisation is contested and complex. Although it can be used in different ways by policymakers and academics, it is often described as having attitudinal and behavioural features that refer to the adoption of radical or extreme beliefs and the justification and use of violence (Neumann, 2013). This has led to a distinction being drawn between cognitive and behavioural radicalisation (Wolfowicz et al., 2021); the former typically describes a process through which an individual comes to adopt extremist beliefs, and the latter framing the end point of radicalisation as involvement in violent behaviour (Neumann, 2013).

A range of models of radicalisation have been developed (e.g., see Borum, 2012; Kruglanski et al., 2018; McCauley & Moskalenko, 2017), however it is widely accepted that there is no uniform radicalisation process, nor is there a common profile of those who become radicalised (Horgan, 2008). Research instead describes pathways into violent extremism as a function of complex, individualised interactions between push and pull factors operating at different levels of analysis (Lewis & Marsden, 2021). There remains some debate over the precise nature of this radicalisation process, with research highlighting how some push and pull factors may be present across multiple cases of radicalisation (Vergani et al., 2020; Wolfowicz et al., 2021), particularly when radicalised individuals emerge from similar, or the same, contexts (e.g., Neve et al., 2020). However, whilst similar factors may be implicated in multiple cases of radicalisation, it is now widely accepted that no single factor causes radicalisation (Lewis & Marsden, 2021). This means that even when similar factors are relevant across multiple cases, individual journeys into violent extremism are driven by interactions between these factors that are specific to each individual, and the specific context(s) in which they are situated.

Despite the contention surrounding the concept of radicalisation (Githens‐Mazer & Lambert, 2010; Kundnani, 2012), it remains a dominant feature of counter‐terrorism policy and practice. A range of interventions have been developed to engage with those considered ‘at risk’ of radicalisation, and those who have become involved in violent extremism and/or been convicted of a terrorist offence (Pistone et al., 2019). Interventions can take different forms, from one‐to‐one mentoring; education, training or vocational provision; ideological guidance; family‐based programmes; mental health support; or help with practical issues such as housing (Koehler, 2017). Research on the process and impact of these interventions is in its infancy, and there is only limited understanding of what works to reduce the risk of involvement or re‐engagement in violent extremism (Hassan et al., 2021a, 2021b; Zeuthen, 2021).

There is also a lack of clarity over what the appropriate aims of interventions to counter radicalisation to violence should be. A distinction is commonly made between deradicalisation and disengagement; the former is typically used to refer to the process of rejecting extreme, violent supportive ideas and attitudes, whilst the latter refers to behavioural changes that see an individual move away from an extremist group (Horgan, 2009). Historically, state efforts focused on enforcing or encouraging disengagement, often through arrest or incentives (Silke, 2011). Over time, attention shifted to the role of ideology, and the potential benefits of trying to change the attitudes and beliefs believed to support violence (Koehler, 2016). More recently, research and practice has come to recognise that, similarly to radicalisation processes, deradicalisation and disengagement are driven by complex, individualised push and pull factors, that demand multi‐dimensional approaches to supporting change (Ellis et al., 2022).

A recent feature of interventions seeking to counter radicalisation to violence is the use of case management tools and approaches (Cherney & Belton, 2021a). Case management involves a tailored approach to working with individuals that structures the process and type of support they receive, from initial assessment through to case planning and exit (Cherney et al., 2020). These types of programmes have been used in a range of other contexts, including social work, corrections, and healthcare (Lukersmith et al., 2016). They have also seemingly been effective in programmes that seek to counter involvement in violence (e.g., Brantingham et al., 2021; Engel et al., 2013), including violence motivated by political or religious ideologies (Weine et al., 2021).

Case management interventions are considered potentially useful in the context of countering radicalisation to violence because the tailored approach they take can accommodate the individualised nature of radicalisation processes (Cherney et al., 2020). However, research on the nature and impact of case management in this context remains limited (Bellasio et al., 2018; Feddes & Gallucci, 2015; Pistone et al., 2019). A modest amount of attention has been directed at the implementation of case management interventions (e.g., Cherney & Belton, 2021a; Harris‐Hogan, 2020) and some research has been carried out on specific stages of the case management process, such as risk assessment (e.g., Scarcella et al., 2016). However, there has been no attempt to systematically assess the tools and approaches used in case management interventions seeking to counter radicalisation to violence.

There are a number of reasons for the limited empirical research on the process and impact of case management interventions in counter‐radicalisation work. Impact evaluations are hampered by methodological and analytical challenges such as identifying appropriate outcome indicators; establishing base rates against which intervention outcomes might be measured; ethical and security challenges associated with using control groups; and difficulties accessing data (Baruch et al., 2018; Lewis et al., 2020). Whereas process evaluations face challenges due to the complexity of interventions that often involve multiple stakeholders and processes operating at different stages of an individual's involvement with case management processes (Lewis et al., 2020).

A broader challenge is the exceptionalism with which interventions that counter radicalisation to violence are often treated, as this can mean insights from different types of intervention or policy context may be missed (Lewis et al., 2020). Together this means that the process by which case management interventions are delivered is rarely considered holistically, and insights from other areas of policy and practice are not adequately recognised.

In response, there have been calls to look to comparable policy areas such as gang‐related violence or larger‐scale militancy to derive insights relevant to countering radicalisation to violence (e.g., Baruch et al., 2018; Davies et al., 2017; Ris & Ernstorfer, 2017). This is because the processes by which people become involved in ideologically motivated and other forms of violence are considered similarly complex, and because efforts to address collective (e.g., Brantingham et al., 2021; Engel et al., 2013) and interpersonal (e.g., Gondolf, 2008) forms of violence use case management approaches.

Thus far, the insights from research on countering a broader range of violence for counter‐radicalisation interventions have not been fully exploited. Although some work has sought to derive lessons from other areas of practice (e.g., Davies et al., 2017), no research has yet systematically identified and applied the insights from research on case management interventions in the broader field of violence reduction to efforts to counter radicalisation.

This systematic review is therefore split into two parts that speak to two important gaps in the literature: first the need to systematically identify and assess the research on case management interventions seeking to counter radicalisation to violence; and second, to identify the insights from research on the broader field of violence prevention for counter‐radicalisation work.

Part I of the review examines the implementation and effectiveness of case management tools and approaches working to counter radicalisation to violence.

Part II of the review examines the implementation and effectiveness of case management tools and approaches working to counter other, non‐terrorism forms of violence.

Whilst focused on different phenomena, both parts of the review are underpinned by a specific conceptualisation of case management that is discussed in detail in Sections 2.2 and 2.3.

2.2. The intervention

Interventions to counter radicalisation to violence have developed across the world (Ucko, 2018). Often described as preventing or countering violent extremism (P/CVE) interventions, they are characterised by a diversity of methods that target different stages of the radicalisation process. These stages are often described in relation to the public health model of prevention which involves primary, secondary and tertiary intervention points (Bhui & Jones, 2017).

Primary interventions aim to address the root causes of extremism, seeking to develop societal and individual resilience to radicalisation through interventions targeted at the general population who are at the ‘pre‐risk stage’ (Elshimi, 2020, p. 229). Secondary interventions work with those considered ‘at risk’ of radicalisation aiming to reduce the risk of an individual becoming actively engaged in violent extremism and terrorism, whereas tertiary interventions work with those involved in terrorism and violent extremism, often once they have been convicted of an offence, and aim to support their disengagement from this activity (Elshimi, 2020).

Case management approaches are increasingly being used in secondary and tertiary interventions aiming to counter radicalisation to violence. For example, the UK's main government‐led secondary intervention, Channel, takes a case‐managed approach (HMG, 2020), whilst the Countering Violent Extremism Early Intervention Program (CVE‐EIP) (Cherney, 2022; Cherney & Belton, 2021a; Harris‐Hogan, 2020) and Proactive Integrated Support Model (PRISM) (Cherney & Belton, 2021b) in Australia use case management to coordinate efforts to support those considered at risk and those convicted of terrorism offences.

The case management approach is significant because it goes beyond specific kinds of intervention methods to structure the process through which services are delivered and monitored. Rather than focusing on, for example, mentoring, educational support, or ideological advice, looking across the case management process offers a wider perspective that pays attention to the different stages at which an individual is supported, from first being identified as in need of assistance through to their exit from the programme.

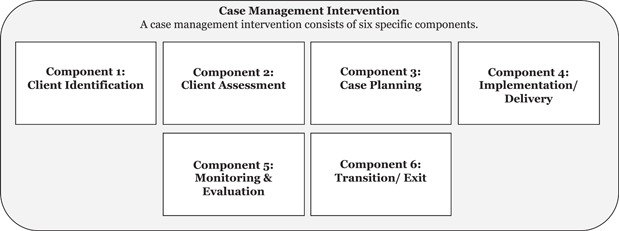

Case management interventions can take different forms, ranging from short‐term, less intensive ‘brokerage’ models where clients are connected to different kinds of support, through to more ‘assertive’ approaches which see case managers work with clients over the longer‐term (Lukersmith et al., 2016). Interventions targeting radicalisation to violence typically adopt more intensive models of case management which is typically understood to involve six stages (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The intensive case management process (based on NCMN, 2009).

Although the specific features of case managed interventions can vary, these six stages are commonly described in guidance provided by professional organisations such as the Case Management Society UK (CMSUK) and Canada's National Case Management Network (NCMN) (CMSUK, 2009; NCMN, 2009). These stages structure the process by which an individual is identified, their needs are assessed, and an intervention to address those needs is planned and implemented. Case management also involves monitoring the client's progress until the point the intervention is assessed to have met their needs or achieved particular outcomes, before the final stage of transition out of the programme (NCMN, 2009; Ross et al., 2011). A key characteristic of case management is that it is client‐centred, as the following definition suggests:

[Case management is] a collaborative process which assesses, plans, implements, coordinates, monitors and evaluates the options and services required to meet an individual's health, care, educational and employment needs, using communication and available resources to promote quality cost effective outcomes. (CMSUK, 2009, p. 8)

Case management interventions involve the use of different tools relevant to each stage of the process, and can be delivered in ways which reflect different approaches. Specifying these tools and approaches helps to organise the knowledge of different aspects of the case management process and understand what influences the process and outcome of interventions. This is particularly helpful as, although some interventions are explicitly organised around the different stages of the case management process set out in Figure 1, many others use aspects of the case management process without organising or labelling it as ‘case management’. Nevertheless, insights are possible by looking at research on the tools and approaches that are used at each stage, which this review defines as follows:

-

–

Case management tools: the processes or methods employed at each stage of the intervention. These include tools used to assess an individual's risk and needs, develop and deliver intervention plans, monitor their progress, and assess and support exit from the programme.

-

–

Case management approaches: theories of change or intervention logics that inform how interventions are delivered. These can be implicit or explicit (White et al., 2021).

2.3. How the intervention might work

Most straightforwardly, case management aims to support positive outcomes by structuring the process of identifying suitable individuals, assessing and delivering support to address their needs, and managing their exit from the programme (Cherney & Belton, 2021a, 2021b). In this way, case management interventions try to interrupt pathways into radicalisation or divert people who are already involved in violent extremism and terrorism by structuring the process of identifying those at greater risk or need and providing tailored support to meet those needs in ways which reduce the risk of engaging in violent extremism and terrorism (Cherney & Belton, 2021a, 2021b).

A central feature of case management interventions is that they are tailored to the individual (CMSUK, 2009). This is why they are considered well suited to take account of the complex, individualised nature of radicalisation and deradicalisation processes (Cherney et al., 2020), and are applicable to a range of kinds of clients, who are engaged in secondary (e.g., Harris‐Hogan, 2020; Pettinger, 2020a, 2020b; Thompson & Leroux, 2022) or tertiary interventions (e.g., AEF, 2018; Schuurman & Bakker, 2016; van der Heide & Schuurman, 2018), or some combination of the two (e.g., Cherney & Belton, 2021a, 2021b). Interventions can focus solely on Islamist radicalisation (AEF, 2018; Schuurman & Bakker, 2016; van der Heide & Schuurman, 2018), be more oriented towards other ideologies such as the far‐right (e.g., Christensen, 2015), or may have a broader or unspecified ideological focus (e.g., Harris‐Hogan, 2020; Thompson & Leroux, 2022).

The delivery agents and contexts for case management interventions vary according to which sectors lead or are engaged in the intervention, and whether they are delivered in community (e.g., Harris‐Hogan, 2020; Pettinger, 2020a, 2020b; Thompson & Leroux, 2022) or correctional contexts (e.g., Cherney, 2018; Schuurman & Bakker, 2016; van der Heide & Schuurman, 2018). Most interventions are standalone programmes specifically designed for countering radicalisation to violence, however some providers integrate CVE into existing, broader, prevention work or other forms of psychosocial support (e.g., Raets, 2022; Thompson & Leroux, 2022). Geographically, interventions can have a national (e.g., AEF, 2018; Harris‐Hogan, 2020; Schuurman & Bakker, 2016; van der Heide & Schuurman, 2018) or a regional focus (e.g., Thompson & Leroux, 2022).

In trying to interpret how case management interventions are supposed to work, this review focuses on the process by which the tools and approaches are implemented, rather than the outcome of the specific services that are delivered through the intervention – for example, training or educational support. The way the intervention might work can therefore be broken down across the different stages of the case management process, as each stage plays a role in identifying, managing and reducing risks, and developing strengths so the individual is less likely to see terrorism as a route to meeting their needs.

2.3.1. Identification

The case management process begins once potential clients in need of support have been identified. In secondary interventions, this identification process typically involves identifying particular patterns of risks and needs considered likely to indicate an elevated risk of involvement in terrorism. In tertiary interventions, an individual's involvement in terrorism or violent extremism has typically already been recognised, for example through a terrorism conviction.

A range of methods may be used to refer clients into interventions. Costa et al. (2021) set out a typology of three different mechanisms: (1) Active; (2) Passive; and (3) Mediated. The active approach involves clients being referred to interventions by front‐line professionals from different sectors (e.g., police, education, healthcare, etc.). This is seen in the UK's approach to secondary interventions (Pettinger, 2020a, 2020b; Weeks, 2018), although similar methods are used in secondary and tertiary interventions in Australia (e.g., Cherney & Belton, 2021a, 2021b; Harris‐Hogan, 2020) and the Netherlands (AEF, 2018; Eijkman & Roodnat, 2017). This type of active approach can include mechanisms through which family members, friends, or community members refer individuals they are concerned about into programmes, or raise concerns about potential radicalisation to relevant front‐line professionals or agencies (e.g., Thomas et al., 2020). Secondary and tertiary interventions may also use a more passive approach, whereby individuals self‐refer into interventions (e.g., Christensen, 2015). And finally, whilst less common, secondary interventions might also incorporate a mediated approach, where families can provide individuals with information about a relevant programme, or even physically take them to an intervention provider (e.g., Costa et al., 2021).

A significant proportion of individuals identified as being potentially in need of counter‐radicalisation support through the active or mediated approach never formally enter the case management process. For example, statistics from the UK's Channel programme indicate that 23% of the 6406 referrals made in the year ending 31st March 2022 were formally assessed by a multi‐agency ‘Channel panel’ (HM Government, 2023). As a result, research that focused on the methods by which members of the public and frontline professionals identify perceived indicators of risk, and decide when to refer into interventions was excluded from this review. Instead, we define the client identification stage as the period during which counter‐radicalisation practitioners make preliminary assessments relating to the potential eligibility of individual clients, and determine whether cases should progress to the client assessment stage. In secondary interventions these assessments may relate to screening out obviously inappropriate, misguided, or ‘spurious’ referrals that do not warrant further action (Lewis, 2021), as well as identifying referrals relating to individuals who are already the focus of a criminal investigation or other, harder forms of intervention (Cherney & Belton, 2021b).

2.3.2. Client assessment

The identification process is typically followed by a formal assessment process. In secondary interventions, the assessment aims to differentiate between those who pose a radicalisation risk, those who do not, and others who might have needs unconnected to terrorism and who could benefit from signposting to alternative forms of support, such as mental health provision. Those ineligible for secondary interventions may fall below the threshold for radicalisation risk (Pettinger, 2020a, 2020b), and may be referred to other agencies or forms of support to address other needs identified through the assessment, or be considered too high risk and in need of harder forms of intervention (Cherney & Belton, 2021b). In tertiary interventions, the assessment process is primarily used to identify client‐specific intervention goals and the relevant forms of support needed to support disengagement from violent extremism, and reduce risk (Cherney & Belton, 2021b). This aspect of case management is examined in detail below.

Eligibility screening can be conducted in different ways and involve different actors. This may include those who are involved in delivering the intervention – on the basis this has the potential to enable them to ‘build rapport and assess their clients’ (van der Heide & Schuurman, 2018, p. 205) – as well as those who will not go on to work with the individual (AEF, 2018; Christensen, 2015). Assessments can be conducted in person, by one or two individuals (AEF, 2018; Christensen, 2015), or a specific team to assess individual cases before their discussion at a multi‐agency case conference (Inspectorate of Justice & Security, 2017, p. 24; also Eijkman & Roodnat, 2017; Vandaele et al., 2022a). However, it is more common for eligibility to be determined by multi‐agency case conferences before intervention staff engage with the client.

Case conferences draw on information from different partners and assess this information to determine whether clients are eligible for counter‐radicalisation support; identify their specific needs; and tailor intervention plans. They are a common feature of interventions across the world, including in the UK (Pettinger, 2020a, 2020b; Weeks, 2018); the Netherlands (AEF, 2018; Hardyns et al., 2022); Canada (Thompson & Leroux, 2022); and Australia (Cherney, 2022). The way case conferences operate varies across different programmes (Vandaele et al., 2022a). For example, some interventions may discuss deidentified cases when assessing individuals (Thompson & Leroux, 2022), in contrast to many interventions, which do not appear to de‐identify potential clients. In some contexts, individuals may be aware they are being discussed at conferences, but in others, they may not (Vandaele et al., 2022a).

Multi‐agency interventions often appoint a dedicated case manager, or in some interventions, multiple case managers (Cherney et al., 2022; van der Heide & Schuurman, 2018). Case managers are typically assigned overall responsibility for managing clients throughout the case management process. They help develop the intervention plan and identify relevant services and organisations able to meet the client's needs, as well as monitoring their progress (AEF, 2018). Some interventions will appoint a dedicated mentor (or mentors) who deliver support to clients alongside facilitating other aspects of the case management process, such as client assessment and case planning (e.g., Christensen, 2015; Fisher et al., 2020).

Risk and needs assessment tools can help inform the assessment process (Lloyd & Dean, 2015), although these tools are not always used in this way (Barracosa & March, 2022; Costa et al., 2021). These tools can be general or specialised for use in terrorism cases. Specialised tools include the Vulnerability Assessment Framework (VAF) (Pettinger, 2020a, 2020b); the Violent Extremism Risk Assessment, Version 2 Revised (VERA‐2R) (Raets, 2022; van der Heide & Schuurman, 2018); and the Terrorist Radicalization Assessment Protocol (TRAP‐18) (Corner & Pyszora, 2022; Raets, 2022). The majority of specialist tools use a Structured Professional Judgement (SPJ) approach, which ‘relies on the discretion of the assessor whilst providing a basic, empirically informed structure to help guide their decision‐making’ (Copeland & Marsden, 2020, p. 7). Specialised tools that use a more structured, actuarial approach are also in use internationally (e.g., Raets, 2022), as are general, non‐specialist tools, such as the Level of Service Inventory Revised (LSI‐R) (Cherney, 2021; Inspector of Custodial Services NSW, 2018). A range of bespoke specialist tools may also be used. This includes tools that are specific to individual interventions, or that are used only in specific regions such as the ‘Radix’ tool developed by one Belgian municipality (Costa et al., 2021; Raets, 2022), and tools that are used to assess specific cohorts, such as youth (Barracosa & March, 2022). All of these tools seek to accurately assess the risk an individual poses and inform decisions about whether and what kind of support they should receive.

2.3.3. Case planning

Case management interventions are operationalised through the delivery of a case plan. The development of the case plan is informed by the assessment process. Some interventions will use risk and needs assessment tools to inform intervention planning (Lloyd, 2019). The basic approach to developing client‐specific case plans typically involves multi‐agency partners discussing the support needs of each client and designing a tailored intervention plan that is designed to target each client's needs, and deliver specific intervention goals (Cherney & Belton, 2021b), through provision of a tailored set of services (Ellis et al., 2022).

Case managers or dedicated mentors often play an important role in developing tailored intervention plans (e.g., AEF, 2018; Inspectorate of Justice & Security, 2017) and monitoring the individual's progress to determine if the case plan is adequately meeting their needs (Harris‐Hogan, 2020). However, the specific approach used may vary across interventions. For example, in some settings, the client and coach/mentor will co‐design an action plan, which will then be presented to, and assessed by, a multi‐agency case conference (AEF, 2018).

In many cases, the case plan structures the process by which services are delivered, for example, sequencing activities in ways which take account of the individual's learning style or needs (Cherney & Belton, 2021a). Case plans developed at the outset of the case management process are unlikely to remain static and may be reviewed and updated regularly to account for an individual's changing circumstances and needs (Disley et al., 2016; Thompson & Leroux, 2022), and respond to any emerging challenges (Cherney, 2022; Vandaele et al., 2022a).

2.3.4. Delivery and implementation

Case management interventions involve the delivery of tailored intervention plans which deploy services considered likely to meet the individual's needs and reduce their risks (Cherney & Belton, 2021a). A diversity of services are typically available including education; employment; lifestyle; psychological help; family provision; and religious or ideological advice, as well as more specific types of support such as music programmes; childcare services; speech therapy; or referral to mental health services (Cherney & Belton, 2021a; Raets, 2022). In some settings, such as the Netherlands, the range of services is much broader, with up to 50 different types of intervention available to clients (AEF, 2018), which are under constant review and expansion (Eijkman & Roodnat, 2017).

The quality and delivery of interventions are supported in a variety of ways. Some intervention programmes – such as secondary and tertiary interventions in the UK – have developed mentor selection and accreditation processes for intervention providers (Pettinger, 2020a, 2020b; Thornton & Bouhana, 2019; Weeks, 2018). In other settings, competency is developed through an ongoing process. For example, in EXIT Sweden, former clients may become ‘client‐coaches’, who support clients whilst continuing to work on their own rehabilitation (Christensen, 2015). Whereas the Team TER reintegration intervention specifically set out to develop a group of specialists from the Dutch Probation Service who would apply their knowledge of working with other types of offenders to this programme, whilst gaining specialist expertise working with terrorist and violent extremist offenders (Schuurman & Bakker, 2016). A similar emphasis on ‘learning by doing’ is used in other interventions in the Netherlands (AEF, 2018; Eijkman & Roodnat, 2017). The aim of these methods is to develop a body of skilled professionals able to deliver and support the case management process.

2.3.5. Monitoring and evaluation

A range of approaches are available to monitor and evaluate an individual's progress through the case management process. These include the use of multi‐agency case conferences which meet to review ongoing cases (e.g., Thompson & Leroux, 2022) and formalised assessment tools. For example, several interventions in Australia use information drawn from the Radar tool and from other sources such as case reviews to assess and track client progress (Cherney, 2022; Cherney & Belton, 2021b; Harris‐Hogan, 2020). Assessments are typically made against their original intervention plan and can be undertaken independently of the client, or as is the case in the Netherlands, collaboratively, so the coach and client assess progress against their action plan, and identify areas that might need additional attention (e.g., AEF, 2018).

As part of a range of different kinds of qualitative data, case files and case notes are used to assess progress and can be used to record a mix of factual information, such as recording that a client attended a session, as well as more subjective client feedback and assessments (Cherney & Belton, 2021a, p. 15; 2021b, p. 630). This process can involve the collation of a range of data collected at different points during the case management process, from different sources, and using different methods, including:

[…] qualitative inputs relating to client background information, risk and needs assessments, client intervention goals, dated observations about intervention staff/service provider engagements with clients, service provider and family members correspondence relating to client appointments, activities and participation, psychologist/counsellor feedback, nature and reason for police contact, court documents and forms of open‐source data.

(Cherney & Belton, 2021a, p. 4)

2.3.6. Transition and exit

The decision of when an individual exits a case management intervention is largely determined by their circumstances and differs between secondary and tertiary interventions. There are few specific timeframes for secondary interventions (AEF, 2018; Costa et al., 2021), whereas when someone has been convicted, their involvement in an intervention is likely to be shaped by the length of their sentence or conditions of their parole. For example, Cherney (2020) notes that PRISM staff may begin the process of engaging clients 2 years before their earliest possible release date. When the individual's sentence has been served, they will typically exit the programme, although in some cases there are opportunities for individuals to continue to receive support after this point should they wish to, or the parole service can request assistance from the original intervention provider when managing a client in the community (Cherney, 2018; Marsden, 2017).

Where the intervention ends before a prisoner's sentence has been completed, or when someone is engaged in a secondary intervention, they are typically assessed to determine if their risk has reduced, and their needs have been met in a way which is consistent with their individualised intervention goals. For example, Khalil et al. (2019) note that exit from the Serendi rehabilitation centre in Somalia is dependent on the individual meeting ‘agreed and personalised rehabilitation objectives relating to family connections, education, vocational training, security issues in the locations of reintegration, and so on’ (p. 4). However, some criteria are more generic. For example, Vandaele et al. (2022a) note that cases in Germany, the Netherlands, and Belgium are closed ‘if no new events of concern occurred’ (p. 71).

The level of aftercare differs across contexts (Costa et al., 2021). Some interventions, such as Forsa in the Netherlands, Serendi in Somalia, and PRISM in Australia, provide ongoing support (AEF, 2018; Cherney, 2020; Khalil et al., 2019). Others including Team TER (van der Heide & Schuurman, 2018), and EXIT Sweden (Christensen, 2015) do not, although intervention staff may choose to stay in contact with former clients when no formal aftercare is offered. The approach to aftercare also varies, some contact former clients periodically or when information on them needs to be updated; others refer clients to other organisations/partners; and some have a structured follow‐up strategy (Costa et al., 2021). These processes aim to provide ongoing support for the individual's reintegration, and to monitor their progress outside the formal case management process.

2.4. Why it is important to do the review

The complexity of radicalisation and deradicalisation processes has led researchers, and policymakers and practitioners, to seek ever more comprehensive routes to countering radicalisation to violence. Increasingly, this has drawn on the principles of case management to structure the process of supporting individuals at risk, or already involved in violent extremism (Cherney & Belton, 2021a). At the same time, scrutiny of counter‐radicalisation interventions has increased, in particular in the wake of apparent failures of case management systems, when individuals enroled in these programmes have gone on to carry out terrorist attacks (Cherney et al., 2022; Clubb et al., 2021).

Inquiries following high‐profile attacks, such as by Usman Khan in London, have raised questions regarding the appropriateness of the tools and approaches used to manage terrorism offenders (Cherney et al., 2022; Lucraft, 2021). However, although the research in this area is growing, it has not yet been systematically synthesised. This is partly because the field is relatively new and the evidence base is still developing (Hassan et al., 2021a, 2021b). It is also because research is dispersed across multiple disciplines; typically focuses on specific aspects of the case management process (e.g., risk assessment or case planning); and with some exceptions (e.g., Cherney & Belton, 2021a, 2021b), rarely explicitly uses the term ‘case management’. In addition, the assumptions that underpin counter‐radicalisation interventions, which are typically understood in relation to logic models or theories of change, are rarely made explicit and/or assessed empirically (Lewis et al., 2020). This hampers evidence synthesis and makes it harder to develop an overall picture of what informs the process and outcome of interventions.

It is also important to learn what influences the implementation of case management interventions. Thus far, there have been no efforts to systematically synthesise research on how case management tools and approaches are used in practice. Without a better understanding of what influences whether, for example, risk assessment tools feed into case planning processes, or if monitoring of individual cases is informed by intervention plans, it is hard to determine what facilitates or creates barriers to implementation, or what contextual conditions, or moderators, shape how interventions are delivered.

Because of the limitations of the research on case management interventions in this field, which has yet to develop a robust evaluation culture (Baruch et al., 2018) or agree a set of progress and outcome measures (Pistone et al., 2019), there have been calls to look to fields with a better developed evidence base (Lewis et al., 2020). Research in the wider field of non‐terrorism related violence prevention has important insights for counter‐radicalisation policy and practice. Both because it has a longer history of evaluation (Davies et al., 2017), and because it has drawn on intensive case management models to structure interventions (Brantingham et al., 2021). However, the implications of broader violence reduction or prevention interventions for counter‐radicalisation work have yet to be fully systematised or exploited.

Given the high cost of failure, there is an unmet need to understand whether the tools and approaches used in case management interventions help counter radicalisation to violence; understand what informs how interventions are implemented in practice; and identify relevant learning from comparable fields. These issues are relevant not only for researchers, but also for policymakers and practitioners who will benefit from a synthesis of what is a rapidly expanding and increasingly dispersed evidence base. By understanding the current state of the research on whether case management interventions help counter radicalisation to violence, what informs how they are implemented, and what learning is possible from other fields, the review will support decision making and provide a foundation to inform the design and delivery of case management interventions. It will do this by first assessing the research to determine the strength of the evidence relating to the effectiveness of case management interventions; second, qualitatively synthesising the research on what facilitates or generates barriers to programme implementation, and how different contexts, or moderators shape these processes; third, synthesising the findings of existing systematic reviews of research on related fields of violence prevention; and finally, examining the transferability of evidence from comparable fields to interventions seeking to counter radicalisation to violence.

3. OBJECTIVES

3.1. Part I: Countering radicalisation to violence

The first part of the review aims to examine the research on case management tools and approaches to determine if they are effective in countering radicalisation to violence, either by supporting primary outcomes indicating diversion or disengagement from violent extremism, desistance or deradicalisation, or enabling secondary outcomes such as measures of client engagement or motivation (Objective 1: effectiveness). The review further aims to assess whether case management tools and approaches are implemented as intended (Objective 2a: implementation), and understand what explains how different case management tools and approaches are implemented, by examining what facilitates, or creates barriers to implementation, and learning whether contextual conditions, or moderators, influence how case management interventions are implemented in practice (Objective 2b: implementation).

3.2. Part II: Countering other forms of violence

The second part of the review aims to examine existing systematic reviews of research on case management tools and approaches seeking to counter other forms of violence to assess whether they are effective at countering interpersonal or collective forms of violence, either by supporting primary outcomes including desistance from violence or reducing the risk of violence or violent recidivism, or secondary outcomes, such as attitudinal or behavioural changes which support desistance (Objective 3). The review will also examine reviews seeking to understand whether case management tools and approaches are implemented as intended (Objective 4a), and what influences how they are implemented, including facilitators, barriers, and moderators (Objective 4b); and assess the transferability of tools and approaches used in wider violence prevention work to counter‐radicalisation interventions (Objective 5).

4. REVIEW PART I – COUNTERING RADICALISATION TO VIOLENCE

4.1. Methods

4.1.1. Criteria for considering studies for Part I

Types of studies

The two objectives for Part I of the review focus on the same question of the role of case management interventions in responding to the problem of radicalisation to violence. However, the inclusion criteria for Objective 1 and Objective 2 rely on different criteria relating to research design and outcome measures. These are considered separately below.

Types of study designs for review of effectiveness (Objective 1)

Only quantitative studies were eligible for inclusion in the review of effectiveness of case management tools and approaches (Objective 1). These studies had to employ a randomised experimental (i.e., Randomised Control Trials) or stronger quasi‐experimental research design. Across both types of research design, comparator or control group conditions could include treatment‐as‐usual; no treatment; and alternative treatment. Robust quasi‐experimental designs had to be in line with the criteria set out by the UK government's Magenta Book (HM Treasury, 2020) and previous Campbell reviews (e.g., Mazerolle et al., 2020), and included the following designs:

-

‐

Cross‐over designs.

-

‐

Regression discontinuity designs.

-

‐

Designs using multivariate controls (e.g., multiple regression).

-

‐

Matched control group designs.

-

‐

Unmatched control group designs where the control group has face validity.

-

‐

Unmatched control group designs allowing for difference‐in‐difference analysis.

-

‐

Time‐series designs.

Types of study designs for review of implementation (Objective 2)

Both quantitative and qualitative studies were eligible for inclusion in the assessment of implementation (Objective 2). Eligible quantitative studies included research designs using randomised experimental and strong quasi‐experimental designs in line with the criteria for Objective 1 (set out above). Studies employing other quasi‐experimental or non‐experimental designs were also eligible for inclusion. These were analysed alongside the qualitative and mixed methods research that was incorporated in this aspect of the review.

To be included, qualitative and mixed methods research had to report on empirical findings on tools or approaches used in case management interventions which were informed by primary data, such as interviews or focus groups, or the secondary analysis of primary data. Opinion pieces, purely theoretical studies, and literature reviews were excluded.

Although qualitative research cannot support causal claims about effectiveness or implementation, it holds important insights into what facilitates and creates barriers to implementing case management interventions. Empirical research that uses interviews, focus groups, or observational research methods provide crucial insights into the factors that shape implementation processes and the inclusion of such research provides the opportunity to capture ‘the broadest range of evidence that assesses the reasons for [an intervention's] implementation success or failure’ (Higginson et al., 2015, p. 22). For these reasons, qualitative research was eligible for inclusion to address Objective 2.

Types of participants

There were no geographical exclusion criteria for either the review of effectiveness (Objective 1) or the review of implementation (Objective 2). There were also no demographic exclusion criteria. Studies drawing on data from participants of any age, gender, ethnicity, religion, or ideological perspective (e.g., right‐wing; Islamist, left‐wing, etc.) were eligible for inclusion. Empirical research which used data drawn from practitioners, stakeholders in any of the multiple agencies that are involved in implementing case management interventions, and clients of those interventions were included in the review.

Types of interventions

Studies for both Objective 1 (effectiveness) and Objective 2 (implementation) had to report on tools or approaches used in case management interventions aiming to counter radicalisation to violence by working directly with those at risk of engaging in, or who have been engaged in violent extremism as described in Section 2.2. Although there is no single model of case management, these interventions are typically understood as being made up of a series of stages. Each stage makes use of a range of tools to support client identification, assessment, case planning, implementation, monitoring and evaluation, and transition and exit. These interventions are also informed by different approaches, or theories of change, which inform how interventions are delivered.

To be eligible for inclusion, studies had to report on tools that were used at one or more stages of the intervention process or examine the approaches or intervention logics (see Section 2.2 for the definition of approaches used in the review) that underpinned the intervention. To capture the range of tools and approaches that are used in interventions seeking to counter radicalisation to violence, the review did not limit itself to studies that explicitly used the case management framework. To be included, studies had to analyse a tool or approach which:

-

(1)

Focused on individuals rather than communities or collectives.

-

(2)

Aimed to counter radicalisation to violence amongst those who had been identified as at risk of involvement in violent extremism and/or those who had been involved with or convicted for engagement in violent extremism (i.e., secondary or tertiary interventions).

-

(3)

Was employed during one or more stages of the case management process described in Section 2.2.

-

(4)

Involved a tailored approach which informed or enabled an individualised intervention seeking to support the move away from violent extremism.

Types of outcome measures

Outcomes relevant to effectiveness of interventions (Objective 1)

Two types of outcome measure were used for the review of effectiveness (Objective 1): primary outcomes that reflected measures of risk reduction, disengagement, or deradicalisation; and secondary outcomes which demonstrated the impact of specific tools or approaches on progress towards primary outcomes.

Primary outcomes relate to the overarching aims of counter‐radicalisation interventions and provide insights into whether the goal of preventing engagement (secondary interventions), or supporting the disengagement and deradicalisation of an individual from violent extremism (tertiary interventions) has been met. Although definitions are contested, deradicalisation is typically understood as attitudinal change that reflects a rejection of extremist ideas and the legitimacy of violence (Horgan, 2009). Disengagement on the other hand, is generally understood as behavioural change that sees someone cease involvement in violent extremism whilst not necessarily rejecting the ideas that support it (Horgan, 2009).

The metrics by which these outcomes can be measured are a source of debate (Lewis, Copeland & Marsden, 2020) and there are no agreed metrics of success for counter‐radicalisation interventions (Baruch et al., 2018). For this review of effectiveness (Objective 1), the first type of outcome measure focused on higher order outcomes that indicate that an individual's risk of engagement has reduced (secondary interventions), or that an individual has either deradicalised or disengaged according to assessments of recidivism or re‐engagement (tertiary interventions). The data underpinning these assessments could be derived from, for example, arrest, prosecution, sentencing and other relevant criminal justice data; interviews or official reporting derived from those involved in the case management process; risk assessments; and/or case notes.

Secondary outcomes are a broader category of measure and reflect lower‐order objectives which can help interpret progress towards the ultimate aim of preventing engagement, or promoting deradicalisation and disengagement. These outcomes relate to the impact of specific tools and approaches that are used across the case management process and their role in enabling or undermining progress towards these goals. Importantly, these assessments are not focused on the impact of specific interventions, such as theological mentoring or the provision of educational support, as these are covered in existing reviews (e.g., Hassan et al., 2021a, 2021b). The focus for this review is on the impact of the tools and approaches that support the delivery of the case management intervention.

To assess whether case management interventions help people move towards these goals, studies which reported the outcome of risk assessments which interpret – and sometimes track – whether risk and/or protective factors have changed in line with intervention goals were eligible for inclusion. A range of risk assessment measures have been developed which seek to assess change across risk and protective factors and are often used to inform intervention planning (Lloyd, 2019). Some of these include:

-

‐

Extremism Risk Guidance (ERG22+): Assesses risk through 22 indicators that are linked to three domains: engagement with a group, cause or ideology; intent to cause harm; and capability to cause harm (Lloyd & Dean, 2015).

-

‐

Violent Extremism Risk Assessment Version 2 Revised (VERA‐2R): Measures risks against a series of indicators which cover attitudes and ideology; history and capacity; commitment and motivation; protective factors; and individual criminal, personal and psychiatric history (Pressman, 2009).

-

‐

Terrorist Radicalisation Assessment Protocol (TRAP‐18): Assesses proximate and distal factors that indicate risk and threat with a focus on lone‐actor terrorism (Meloy, 2018).

To understand the impact of case management tools and approaches, studies were eligible if they reported quantitative evidence which evaluated the effect of one or more tools or approaches. Although none were identified, this would have included studies which assessed both the effectiveness of overall approaches including risk and strengths‐based approaches, and the impact of specific tools on different stages of the case management process.

Eligible studies reporting on specific tools could record the outcome of identification and referral processes, for example by assessing how many individuals were accurately identified and referred; risk assessment tools, by determining the impact of effective risk assessment processes; case planning, by assessing whether certain tools used to support case planning were more or less effective than others; the outcome of case planning processes and whether, for example, they identified the most appropriate interventions in individual cases; delivery processes, assessed by the extent to which they helped to support engagement and participation with interventions, or reduced levels of drop out; the relative impact of different monitoring and evaluation regimes; and tools to support transition and exit, for example, by assessing the relative impact of different ways of assessing needs and referring on to additional forms of support at the end of the case management process.

Outcomes relevant to implementation of interventions (Objective 2)

In line with Mazerolle et al. (2021), no specific outcome measures were necessary for studies to be eligible for inclusion in the assessment of implementation (Objective 2). Instead, all qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods empirical research which addressed implementation factors were eligible. Implementation factors were defined as ‘actions or actors necessary to successfully install and maintain an intervention’ (Cherney et al., 2020, p. 16) and were understood in relation to facilitators, which supported the implementation of case management intervention tools and approaches, and barriers which had the potential to undermine implementation.

A wide range of factors have the potential to act as facilitators and barriers to implementation. To give some examples in relation to tools, these might include factors which influence the identification and referral process such as the capacity of the organisations tasked with identifying relevant individuals (e.g., Becker et al., 2014). Factors relevant to implementing assessment processes could include the suitability of the criteria used to inform risk assessment tools (e.g., Fisher et al., 2020). In regard to case planning, implementation might be impacted by the ways in which case conferences are managed (Vandaele et al., 2022b), whilst practitioner characteristics might shape how interventions are delivered (e.g., Orban, 2019), and the quality of data capture and management processes may influence the implementation of monitoring and evaluation processes (e.g., Cherney & Belton, 2021a). Finally, transition and exit might be facilitated by good inter‐agency working (Cherney, 2020), or undermined due to difficulties monitoring individuals on release (Stern et al., 2023).

As well as studies which analysed facilitators and barriers, the review also included research which reported data relevant to moderators, or the ‘contextual conditions’ or ‘features of the people or places that are the target for intervention’ (Cherney et al., 2020, p. 15), and research that analysed whether interventions were being implemented as intended. Moderators can include the features of the delivery context, for example, whether an intervention is run in prisons or in the community; the characteristics of individual clients, informed by their demographics, or social and cultural context; the nature of the delivery agents, for instance whether they are civil society organisations or correctional staff; different organisational mandates; and the philosophy of different intervention providers and funders.

Although qualitative research does not treat outcomes in the same way as quantitative research, and may not refer to outcomes in its analysis, it remains valid for interpreting what shapes implementation processes (Mazerolle et al., 2021). Rather than focusing on outcomes, qualitative research typically discusses thematic features of data drawn from a range of sources able to inform broader insights into the process of implementing interventions. To capture these insights, this review included empirical research that analysed factors which facilitated or generated barriers to the implementation of tools and approaches, and the contextual conditions that shaped how interventions were implemented across all stages of the case management process.

Duration of follow‐up

No restrictions were placed on the length of follow up for either the review of effectiveness (Objective 1) or the review of implementation (Objective 2).

Types of settings

No geographic or setting‐based restrictions were used to exclude studies. Research conducted in any country, and reported on in the languages covered by the review (English, French, German, Swedish, Danish, Norwegian, and Russian) was eligible for inclusion.

4.1.2. Search methods for identification of studies

The search process for English language material involved six stages that sought to identify relevant academic and grey literature research.

-

1.

Identification and piloting of search terms.

-

2.

Targeted search term searches of academic databases.

-

3.

Hand searches of key journals, research outputs of relevant research institutions/professional agencies, and clinical trial repositories.

-

4.

A review of studies cited in key evidence synthesis papers.

-

5.

Consulting members of the research team and advisory board to identify studies.

-

6.

Forward and backward citation searching of studies identified at Stages 1–5.

Identification and piloting of search terms

Search terms were developed by the research team and piloted in May 2021 using PsycNet as a test database to determine the scale of the literature and the sensitivity of the search terms. Search terms were differentiated according to two search domains:

-

‐

Problem (Any Field: extremis* OR Any Field: terror* OR Any Field: radical*) AND

-

‐

Intervention (Any Field: prevent* OR Any Field: treat* OR Any Field: interven*)

This process led to the team refining the search strategy searches to reduce the number of irrelevant and/or non‐empirical studies. Informed by feedback from the Campbell Crime and Justice Editorial Group, a further piloting process in May 2022 led to a search strategy informed by three domains:

-

‐

Problem: Search terms relevant to violent extremism and its synonyms (radicali*, extremis*, terroris*); or specific ideologies (e.g., ‘far‐right’; ‘white supremacis*’).

AND

-

‐

Intervention: Search terms describing synonyms for interventions (e.g., ‘interven*’; ‘program*’, etc.) and tools (e.g., ‘tool*’; ‘instrument*’); and the different stages of the case management process (e.g., ‘refer*’; ‘assess*’);

AND

-

‐

Outcomes: Search terms relating to primary outcomes of prevention (e.g., ‘prevent*’); and desistance (e.g., ‘disengage*’).

The full list of search terms is available in Supporting Information: Appendix I.

Electronic searches

A search of electronic databases was carried out by The Campbell Collaboration Crime and Justice Coordinating Editor and Information Specialist (Elizabeth Eggins) in August 2022. The databases are detailed in Table 1. The databases were categorised as either principal of supplementary sources according to the functionality and replicability of their search functions. This approach was informed by the findings of Gusenbauer and Haddaway's (2020) analysis of 28 academic search systems for systematic reviews. Principal resources are characterised by a more comprehensive search capability which supports the use of different combinations of search terms across multiple search fields. Supplementary resources have more limited search functionality and typically do not allow for fully comprehensive search term searching, or the easy replication of searches. The search syntax, tailored for each database, is available in Supporting Information: Appendix I. The timeframe for the searches began in January 2000, as this marks the point at which radicalisation, and subsequently, deradicalisation, began to emerge as a feature of policy discourse (Neumann, 2013).

Table 1.

Platforms/providers included in review.

| Platform/provider | Specific databases searched (if applicable) | Search fieldsa | Resource type |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ovid | PsycInfo | ab,hw,id,mh,ot,ti. | Principal |

| Elsevier | Scopus | TITLE‐ABS‐KEY | Principal |

| Web of Science | Book Citation Index (Social Sciences & Humanities); Social Sciences Citation Index; Arts & Humanities Citation Index; Emerging Sources Citation Index; Conference Proceedings Citation Index (Social Sciences & Humanities); Medline | Topic | Principal |

| EBSCOhost | Criminal Justice Abstracts |

Title Abstract Keywords Subject |

Principal |

| ProQuest | International Bibliography of the Social Sciences | ti, ab, mainsubject | Principal |

| ProQuest | Sociological Abstracts | ti, ab, if | Principal |

| Informit | CINCH: Australian Criminology Database | All Fields | Supplementary |

| ProQuest | Dissertations and Theses Global | ti, ab, mainsubject, diskw | Principal |

| EThOS (Dissertations) | N/A | All fields | Supplementary |

| Directory of Open Access Journals (DOAJ) | N/A | All fields | Supplementary |

Although preferable to search across all search fields in every database, the number of results returned from larger databases becomes too large to sift. These search fields are therefore tailored to the size of each database.

Searching other resources

In addition to searching electronic academic databases, we carried out searches of relevant websites and research repositories to identify grey literature. The search process for these sources was tailored to the functionality of the website. For example, for websites that were specific to the field of countering radicalisation to violence (e.g., Hedayah), we searched all publications listed on the website. For others with a broader focus (e.g., RAND), we searched all publications listed under relevant sections/themes (e.g., countering violent extremism).

The list of websites used to identify grey literature sources is in Table 2.

Table 2.

Grey literature sources.

| Source | Description |

|---|---|

|

Institute for Strategic Dialogue (ISD) |

Research centre |

|

RAND |

Research centre |

|

Royal United Services Institute (RUSI): |

Research centre |

|

Hedayah |

Research centre |

|

International Centre for Counter‐Terrorism (ICCT) |

Research centre |

|

Resolve Network |

Research centre |

|

Global Center on Cooperative Security |

Research centre |

|

International Centre for the Study of Radicalisation (ICSR): |

Research centre |

|

Centre for Research and Evidence on Security Threats (CREST) |

Research centre |

|

National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism (START) |

Research centre |

|

IMPACT Europe |

Research repository |

|

CT‐MORSE |

Research repository |

|

National Criminal Justice Reference Service (NCJRS) |

Research repository |

|

Radicalisation Research |

Research repository |

|

VOX‐Pol |

Research repository |

|

Crime Solutions |

Research repository |

|

College of Policing Crime Reduction Toolkit https://www.college.police.uk/research/crime-reduction-toolkit |

Research repository |

|

Global Policing Database |

Research repository |

|

Europol |

Government agency |

|

Public Safety Canada |

Government agency |

|

Department for International Development: Research for Development |

Government agency |

|

Radicalisation Awareness Network https://ec.europa.eu/home-affairs/networks/radicalisation-awareness-network-ran_en |

Government agency |

Hand searches of key journals were undertaken to identify recently published material that may not have been catalogued in the academic databases, and to ensure no relevant studies had been missed in the main search. This process involved searching all volumes and issues of each journal published since 2000, and, where relevant, any online first articles that had yet to be included in a published issue. The journals covered by these searches are listed in Table 3.

Table 3.

Key journals.

| Journal name |

|---|

| Terrorism and Political Violence |

| Studies in Conflict & Terrorism |

| Behavioral Sciences of Terrorism and Political Aggression |

| Critical Studies on Terrorism |

| Journal for Deradicalization |