Abstract

Background

Despite the encouraging outcome of chimeric antigen receptor T cell (CAR-T) targeting B cell maturation antigen (BCMA) in managing relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma (RRMM) patients, the therapeutic side effects and dysfunctions of CAR-T cells have limited the efficacy and clinical application of this promising approach.

Methods

In this study, we incorporated a short hairpin RNA cassette targeting PD-1 into a BCMA-CAR with an OX-40 costimulatory domain. The transduced PD-1KD BCMA CAR-T cells were evaluated for surface CAR expression, T-cell proliferation, cytotoxicity, cytokine production, and subsets when they were exposed to a single or repetitive antigen stimulation. Safety and efficacy were initially observed in a phase I clinical trial for RRMM patients.

Results

Compared with parental BCMA CAR-T cells, PD-1KD BCMA CAR-T cell therapy showed reduced T-cell exhaustion and increased percentage of memory T cells in vitro. Better antitumor activity in vivo was also observed in PD-1KD BCMA CAR-T group. In the phase I clinical trial of the CAR-T cell therapy for seven RRMM patients, safety and efficacy were initially observed in all seven patients, including four patients (4/7, 57.1%) with at least one extramedullary site and four patients (4/7, 57.1%) with high-risk cytogenetics. The overall response rate was 85.7% (6/7). Four patients had a stringent complete response (sCR), one patient had a CR, one patient had a partial response, and one patient had stable disease. Safety profile was also observed in these patients, with an incidence of manageable mild to moderate cytokine release syndrome and without the occurrence of neurological toxicity.

Conclusions

Our study demonstrates a design concept of CAR-T cells independent of antigen specificity and provides an alternative approach for improving the efficacy of CAR-T cell therapy.

Keywords: Immunotherapy; Receptors, Chimeric Antigen; Multiple Myeloma

WHAT IS ALREADY KNOWN ON THIS TOPIC.

B-cell maturation antigen (BCMA)-directed chimeric antigen receptor T-cell (CAR T) therapy is one of the most significant therapies in the treatment landscape of relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma (RRMM) over the last decade. Nevertheless, a considerable proportion of patients continue to relapse partially due to the dysfunction of CAR-T cells which is characterized by exhaustion or limited persistence and impaired function within the immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment such as extramedullary disease.

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS

It demonstrated that the new BCMA-targeted CAR-T cell which carries an OX-40 costimulatory domain and incorporates with an anti-PD-1 short hairpin RNA may improve therapeutic response by preserving a cell memory phenotype and reducing exhaustion. Moreover, we provided an initial demonstration of the safety and efficacy of these PD-1KD BCMA CAR-T cells in a phase I clinical trial for RRMM patients.

HOW THIS STUDY MIGHT AFFECT RESEARCH, PRACTICE OR POLICY

We suggested that the optimized PD-1KD BCMA CAR T cells could be a potential therapeutic option in the future for RRMM, especially patients with extramedullary diseases. A larger, multicenter clinical trial and longer follow-up are necessary to validate these findings in RRMM patients.

Introduction

Chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cells have emerged as a promising immunotherapy against tumors, especially in hematological malignancies. Impressive clinical responses have been achieved in the B cell maturation antigen (BCMA) targeting CAR-T cells.1–4 In our phase I/II clinical trials of Cilta-Cel (LCAR-B38M), encouraging, deep, and durable responses were reported in relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma (RRMM) patients.5–7 Despite the remarkable response rates achieved with the CAR-T cell therapies, a considerable proportion of patients continue to relapse partially due to the dysfunction of CAR-T cells,8 9 which is characterized by impaired function within the immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment, the development of exhaustion or limited persistence in vivo.10 11 Extramedullary disease (EMD) is also a poor prognostic factor for multiple myeloma patients even in the era of CAR-T cell therapy. Approaches to enhance the antitumor efficacy of CAR-T cells, especially to improve clinical outcome in patients with EMD, remain to be identified.12

Numerous translational and basic studies have emphasized the role of PD-1 as a major inhibitory checkpoint receptor. Binding of PD-1 to its ligand PD-L1 within the immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment inhibit the early stage of CAR-T cell activation and the effector function of CAR-T cell at the later stage.13–15 CAR-T cells under chronic antigen stimulation from tumors become progressively exhausted and functionally compromised.16 At an early stage of T-cell exhaustion, the activated PD-1/PD-L1 signaling pathway contributes to the initiation of T-cell exhaustion by inhibiting key metabolic regulators.17 In addition to their involvement in metabolic regulation, PD-1 and key exhaustion transcription factors might interact with each other to synergistically induce and reinforce T-cell exhaustion during long-term antigen exposure.15 18 Therefore, blockage of PD-1/PD-L1 signaling pathway is believed to reduce the inhibitory state of the tumor microenvironment, reinvigorate exhausted T cells and thereby reverse the antitumor efficacy of CAR-T cells. Indeed, combination therapy with CAR-T cells and an anti-PD-1/PD-L1 antibody is commonly used to rescue CAR-T cell effector functions in clinical trials.19–21 However, it is difficult to optimize the dose of CAR-T cells with an anti-PD-1 antibody, since these cells are variably expanded in vivo, which potentially results in inconsistent responses and unpredictable toxicity.

In this study, we designed BCMA-targeted CAR-T cells that carried an OX-40 costimulatory domain and incorporated with an anti-PD-1 short hairpin RNA (shRNA) to achieve stable long-lasting antitumor effects. We observed superior proliferation and cytokine production during the early phase of CAR-T cell activation. Additionally, immune memory was increased and exhaustion was delayed after repeated antigen stimulation of PD-1KD CAR-T cells. Moreover, we provided an initial demonstration of the safety and efficacy of these new CAR-T cells in a phase I clinical trial of RRMM patients. Our study helps to optimize the function of CAR-T cells through suppressing PD-1/PD-L1 signaling for the treatment of different tumors independent of the immunosuppressive microenvironment.

Results

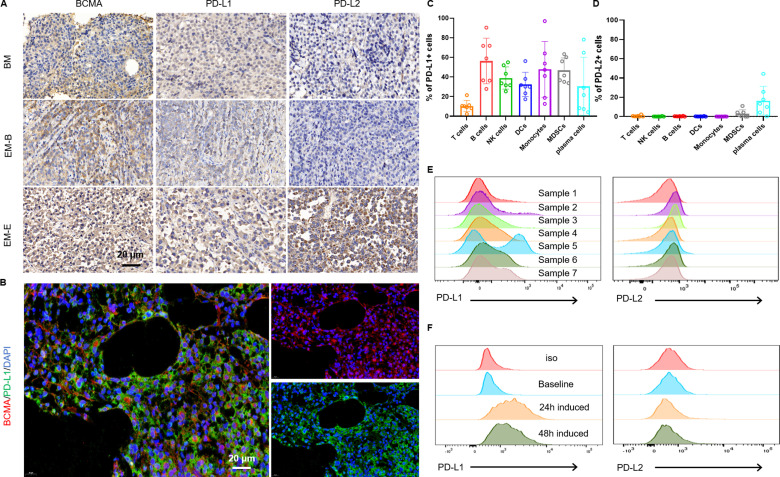

Expression patterns of BCMA/PD-L1/PD-L2 in the bone marrow and EMD sites of RRMM patients

We evaluated the protein levels of BCMA/PD-L1/PD-L2 in bone marrow (BM) tissue and EMD sites. We observed that BCMA was expressed specifically on plasma cells. Six of eight BM tissue samples and four of eight EMD tissue samples were considered positive for PD-L1 with variable intensities, but PD-L2 was observed in only one relapsed EMD tissue sample (figure 1A). In addition, BCMA and PD-L1/PD-L2 were colocalized on MM cells (figure 1B, online supplemental figure 1), suggesting a possible inhibitory role of PD-L1/L2 on BCMA CAR-T cells. PD-L1 was expressed on MM cells and almost all immune cells in the BM environment and PD-L1 was more abundant than PD-L2 was (figure 1C–E). Consistent with a previously report,22 coculture of CAR-T cells with MM cells also resulted in upregulation of PD-L1 expression in BMMCs (figure 1F). We next assessed whether PD-L1 overexpression could inhibit BCMA-targeted CAR-T cell function in an in vitro model of PD-L1-mediated BCMA-expressing K562 cells (online supplemental figure 2A). PD-L1 overexpression resulted in decreased cytotoxicity (online supplemental figure 2B) and cytokine secretion (online supplemental figure 2C).

Figure 1.

Characterization of BCMA/PD-L1/PD-L2 expressions in the bone marrow and extramedullary disease sites of MM patients. (A) IHC staining of BCMA/PD-L1/PD-L2 expressions in patient tumor tissues. Representative images of extramedullary bone-related disease arising from the hand and extramedullary extraosseous disease arising from intracranial plasmacytoma. (B) Representative immunofluorescence images showing the expression of BCMA and PD-L1 and their colocalization in BM samples from RRMM patients. Scale bar, 20 µm. Flow cytometry assays showing expressions of PD-L1(C) and PD-L2 (D) on various cell types in BMMCs from seven RRMM patients. (E) Representative histograms of PD-L1(left) and PD-L2 (right) expression in BMMC samples from seven RRMM patients. (F) Representative results showing induced PD-L1 expression in BMMCs after 24 hours coculture or 48 hours of coculture with BCMA CAR-T cells (n=3 independent healthy donors). BCMA, B cell maturation antigen; EM-B, extramedullary bone-related; EM-E, extramedullary extraosseous; IHC, immunohistochemical; MM, multiple myeloma; RRMM, relapsed/refractory MM.

jitc-2023-008429supp001.pdf (814.4KB, pdf)

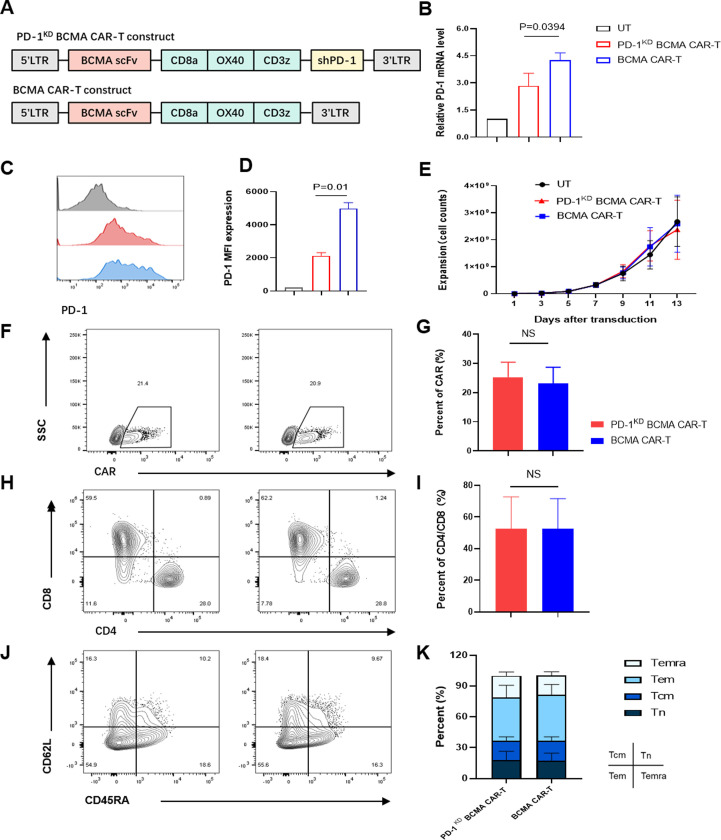

PD-1 inhibition enhances antitumor and proliferation capacity of BCMA CAR-T cells

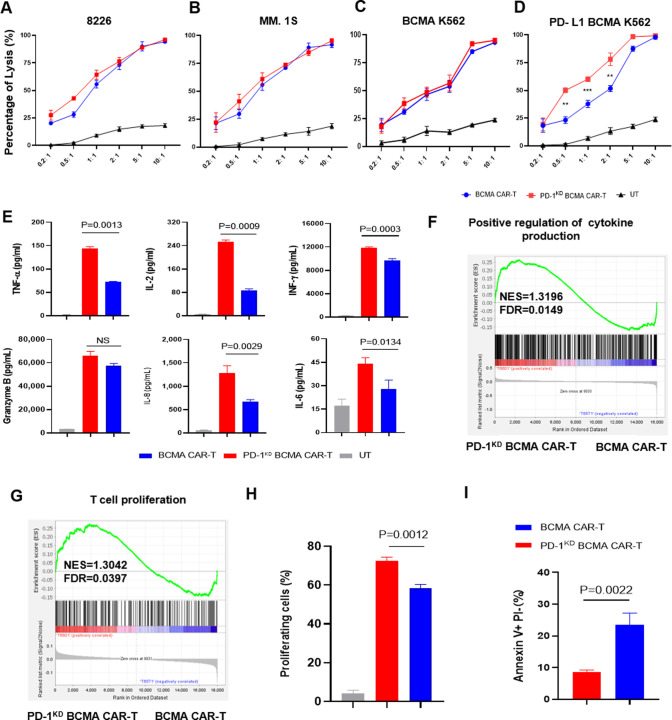

We constructed a BCMA-targeting CAR sequence containing an OX 40 costimulatory domain and an anti-PD-1 shRNA sequence driven by the U6 promoter (PD-1KD BCMA CAR) (figure 2A). In our previous study, OX40 costimulation resulted in greater proliferation and better immune memory than did CD28 and 4-1BB costimulation in the context of repeated stimulation.23 After the shRNA sequences were optimized, we first evaluated the efficiency of PD-1 inhibition by detecting the transcriptional activity of the known target gene PDCD1 in HEK293T cells (online supplemental figure 3). To examine whether the selected shRNA had a sufficient inhibitory effect on PD-1 expression in BCMA CAR-T cells, we packaged the shRNA2 construct into the BCMA CAR backbone and tested the expression of PD-1 after antigen stimulation. Indeed, the new BCMA CAR-T construct, named PD-1KD BCMA CAR-T cells, efficiently reduced the expression of PD-1 (figure 2B–D), without noticeably negatively affecting on CAR-T cell expansion (figure 2E), CAR expression (figure 2F,G) or CAR-T cell subsets (figure 2H–K). In vitro, compared with their control cells (BCMA CAR-T cells), PD-1KD BCMA CAR-T cells exhibited similar cytotoxicity on stimulation with irradiated myeloma cells (figure 3A,B) and BCMA+K562 cells (figure 3C). However, when confronted with PD-L1-overexpressing tumor cells, these new CAR-T cells exhibited superior cytotoxicity (figure 3D) and T-cell cytokine production (figure 3E). The effect of PD-1 inhibition was also verified in other antitumor CAR-T cells, including anti-CLL-1 and anti-CD19 CAR-T cells, for which the PD-1 KD groups showed superior antitumor efficacy (online supplemental figure 4).

Figure 2.

Characteristics of the PD-1KD BCMA CAR-T cells. (A) Diagrams of the anti-BCMA CAR with and without shPD-1. (B) Expression of PD-1 in the CAR+cell population (9 days after virus infection) after 24 hours of coculture with 8226 cells. During coculture, shPD-1 significantly decreased the expression of PD-1 (p=0.0394 < 0.05). (C) Representative expression of PD-1 in the CAR+cell population (9 days after virus infection) determined by flow cytometry after 24 hours of coculture with 8226 cells. (D) Median fluorescence intensity (MFI) of PD-1 expression in CAR+cells detected after 24 hours of coculture with 8226 cells. CD3+ (untransfected T cells, control) or CD3+CAR+ cells were analyzed. Compared with that in BCMA CAR-T cells, shPD-1 significantly decreased the expression of PD-1 (p=0.01< 0.05). (E) Expansion of CAR-T cells after transduction (n=3 independent healthy donors). (F) Representative CAR expression was determined by flow cytometry in PD-1KD BCMA CAR-T cells (left) and BCMA CAR-T cells (right). (G) The percentages of CAR+ cells were compared between PD-1KD BCMA CAR-T cells and BCMA CAR-T cells. (H) Representative CD4+ and CD8+ CAR+T cell proportions were determined by flow cytometry in PD-1KD BCMA CAR-T cells (left) and BCMA CAR-T cells (right). (I) The ratios of CD4/CD8 in CAR+T cells were compared between PD-1KD BCMA CAR-T cells and BCMA CAR-T cells. (J) The differentiation status of PD-1KD BCMA CAR-T cells (left) and BCMA CAR-T cells (right) were determined via flow cytometry using the surface markers CD45RA and CD62L. (K) Ratios of naive (Tnaive-like; CD45RA+CD62L+), central memory (Tcm; CD45RA−CD62L+), effector memory (Tem; CD45RA−CD62L−), and most differentiated T (Temra; CD45RA+CD62 L−) cells in PD-1KD BCMA CAR-T cells and BCMA CAR-T cells were compared. BCMA, B cell maturation antigen; NS, not significant; UT, untransfected T cells.

Figure 3.

PD-1 inhibition enhances antitumor efficiency and proliferation capacity of BCMA CAR-T cells. (A) In vitro cytotoxicity of BCMA CAR-T or PD-1KD BCMA CAR-T cells against 8226 cells, MM.1S cells (B), BCMA overexpressing K562 cells (C) and PD-L1/BCMA overexpressing K562 cells (D) was determined by a luciferase-based cytotoxicity assay. E/T ratio, effector/target ratio (n=3 independent healthy donors). (E) Cytokines in the supernatant after coculture with PD-L1/BCMA overexpressing K562 cells for 24 hours. GSEA of the genes associated with (F) the positive regulation of cytokines is listed in online supplemental table 1, and (G) the genes related to the proliferation of T cells are listed in online supplemental table 2. The genes from the left to the right of the rank-ordered list are enriched in PD-1KD BCMA CAR-T cells and BCMA CAR-T cells. (H) Cell proliferation was compared among non-CAR T cells, PD-1KD BCMA CAR-T cells and BCMA CAR-T cells on stimulation with one dose of antigen. (I) Analysis of apoptotic PD-1KD BCMA CAR-T cells and BCMA CAR-T cells on day 5 after one dose of antigen stimulation. BCMA, B cell maturation antigen; FDR, false discovery rate; GSEA, gene set enrichment analysis; NES, normalized enrichment score.

jitc-2023-008429supp002.pdf (78.4KB, pdf)

jitc-2023-008429supp003.pdf (72.7KB, pdf)

Next, we compared the gene expression profiles of BCMA CAR-T cells and PD-1KD BCMA CAR-T cells after one dose of stimulation with irradiated 8226 cells. We applied principal component analysis to infer the variance in the different axes and found a similar transcriptome between the two BCMA CAR-T cell lines, indicating that PD-1 inhibition had no negative effect on the total transcriptional profile (online supplemental figure 5). Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) revealed the upregulation of positive regulation of cytokine production-related and T-cell proliferation-related genes (figure 3F,G). A proliferation advantage was further confirmed usingcarboxyfluorescein diacetate succinimidyl ester (CFSE) assays (figure 3H). To assess whether the increase in T-cell proliferation was due to reduced T-cell apoptosis in PD-1KD BCMA CAR-T cells, we performed annexin V and propidium iodide (PI) double staining and observed a significant decrease in the early apoptotic cell population in PD-1KD BCMA CAR-T cells compared with that in parental BCMA CAR-T cells (figure 3I).

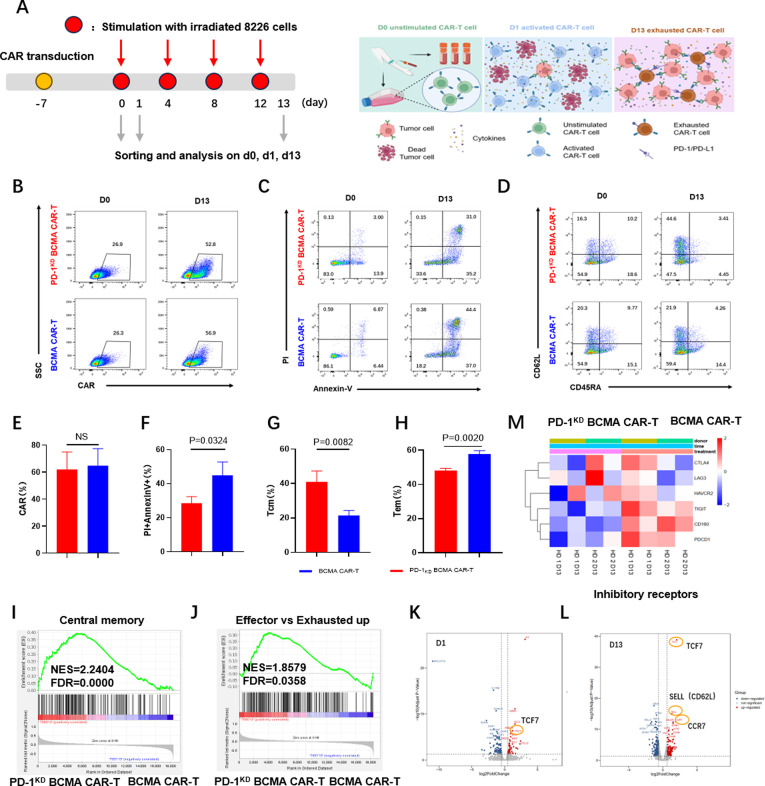

PD-1KD BCMA CAR-T cells maintain memory T cell phenotypes and exhibit deceased exhaustion after repetitive antigen stimulation

To test whether PD-1KD BCMA CAR-T cells have enhanced antitumor efficacy after long-term antigen exposure, we used a repetitive antigen stimulation method to simulate a long-lasting chronic tumor burden (figure 4A). We did indeed observe a visible increase in the positive rate of CAR expression in both BCMA CAR-T cells and PD-1KD BCMA CAR-T cells after repetitive antigen stimulation; however, no distinct difference was found (figure 4B,E). Consistent with the results obtained following a single stimulation, the PD-1KD BCMA CAR-T cells exhibited less apoptosis than the parental BCMA CAR-T cells after repeated antigen stimulation (figure 4C,F). We also compared the T-cell subsets between these two groups and found an increase in the proportion of central memory T cells (CD62L+CD45RA-) and a decrease in the percentage of effector memory T cells (CD62L−CD45RA−) in the PD-1KD BCMA CAR-T cells (figure 4D,G and H). Gene sets related to central memory, as well as effector versus exhaustion up genes were upregulated in the PD-1KD BCMA CAR-T cells (figure 4I,J). Volcano plots of the genes differentially expressed between the two groups revealed a significant increase in the expression of the gene TCF7 after one round of antigen stimulation (figure 4K). Along with the high expression of TCF7, expression of SELL and CCR7 after four rounds of antigen stimulation increased (figure 4L). A heatmap of the transcriptional profiling results revealed a significant decrease in the expression of several inhibitory checkpoint genes involved in the T-cell exhaustion, such as CTLA4, LAG3, HAVCR2 (TIM3), TIGIT, CD160, and PDCD1, in the PD-1KD BCMA CAR-T cell population (figure 4M).

Figure 4.

PD-1 inhibition promotes the memory phenotype and reduces the exhaustion of BCMA CAR-T cells. (A) Schematic diagram of the CAR-T cell cytotoxicity assay after long-term repetitive antigen stimulation. (B) CAR expression was determined by flow cytometry in PD-1KD BCMA CAR-T cells (upper) and BCMA CAR-T cells (lower) after fourth repetitive stimulation (d13). Representative (B) and summarized (E) data from three representative healthy donors are shown. (C) Annexin V and PI-staining of PD-1KD BCMA CAR+T and BCMA CAR+T cells after four repetitive stimulations (d13). Representative (C) and summarized (F) data from three representative healthy donors are shown. (D) Representative differentiation statuses of PD-1KD BCMA CAR-T cells (upper) and BCMA CAR-T cells (lower) cells were determined by flow cytometry using the surface markers CD45RA and CD62L after four repetitive stimulations (d13). (G, H) Ratios of central memory (Tcm; CD45RA−CD62L+) and effector memory (Tem; CD45RA−CD62L−) cells were compared for PD-1KD BCMA CAR-T and BCMA CAR-T cells. (I) GSEA of central memory genes. The central memory genes are shown in online supplemental table 3. The genes from the left to the right of the rank-ordered list are enriched in PD-1KD BCMA CAR-T cells and BCMA CAR-T cells. (J) GSEA of effector versus exhausted up genes. Effector versus exhausted upgenes are shown in online supplemental table 4. The genes from the left to the right of the rank-ordered list are enriched in PD-1KD BCMA CAR-T cells and BCMA CAR-T cells. (K, L) Volcano plots of genes differentially expressed between PD-1KD BCMA CAR+T cells and BCMA CAR+T cells sorted after one antigen stimulation (d1) or after four repetitive stimulations (d13). Significantly differentially expressed genes associated with the memory phenotype are highlighted with an orange circle. (M) Heatmap of normalized RNA-seq reads for exhaustion-related genes differentially expressed between PD-1KD BCMA CAR+ and BCMA CAR+T cells after four repetitive stimulations (d13). The results are from two representative healthy donors with two duplicates. BCMA, B cell maturation antigen; GSEA, gene set enrichment analysis; HD, heathy donor; NES, normalized enrichment score; FDR, false discovery rate.

jitc-2023-008429supp004.pdf (73.2KB, pdf)

jitc-2023-008429supp005.pdf (73.3KB, pdf)

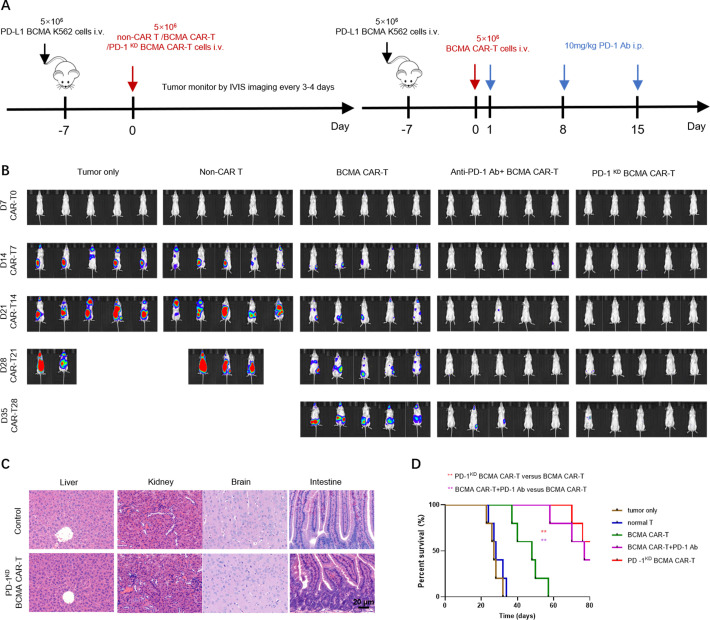

PD-1KD BCMA CAR-T cells show superior antitumor effects in vivo

To determine whether the superiority of the PD-1KD BCMA CAR-T cells that we observed in vitro correlates with antitumor efficacy in vivo, we established a PD-L1 BCMA K562 xenograft tumor model in NCG mice (figure 5A). Consistent with the enhanced proliferation and cytotoxicity observed in vitro, compared with BCMA-CAR T cells, PD-1KD BCMA CAR T cells exhibited significantly greater antitumor activity in PD-L1 tumor-bearing mice as dynamically determined by IVIS imaging. Additionally, the antitumor efficacy of PD-1KD BCMA CAR-T cells was comparable to that of BCMA CAR-T cells combined with repeated anti-PD-1 antibody administration (figure 5B), and this increased antitumor efficacy was also correlated with prolonged overall survival (OS) in this group (figure 5D). We also evaluated off-target toxicity in vivo. No signs of toxicity were observed in mice treated with the PD-1KD BCMA CAR-T cells (figure 5C). These results demonstrate that PD-1 inhibition in CAR-T cells has superior antitumor efficacy and a favorable safety profile in vivo.

Figure 5.

BCMA CAR-T cells with PD-1 inhibition had enhanced antitumor efficacy in a PD-L1+CDX tumor model. (A) Experimental timeline of the CDX tumor model. (B) Bioluminescence imaging of tumor cell growth following different treatments on the indicated days after CAR-T cell infusion (n=5). (C) Kaplan-Meier curves for overall survival are shown. Statistical significance was determined by the MantelCox test and is presented by **p≤0.01. (D) H&E-stained tissues from mice treated with either tumor only (upper) or PD-1KD BCMA CAR-T cells (lower) 7 days after CAR-T cell infusion. Scale bar: 20 µm. BCMA, B cell maturation antigen.

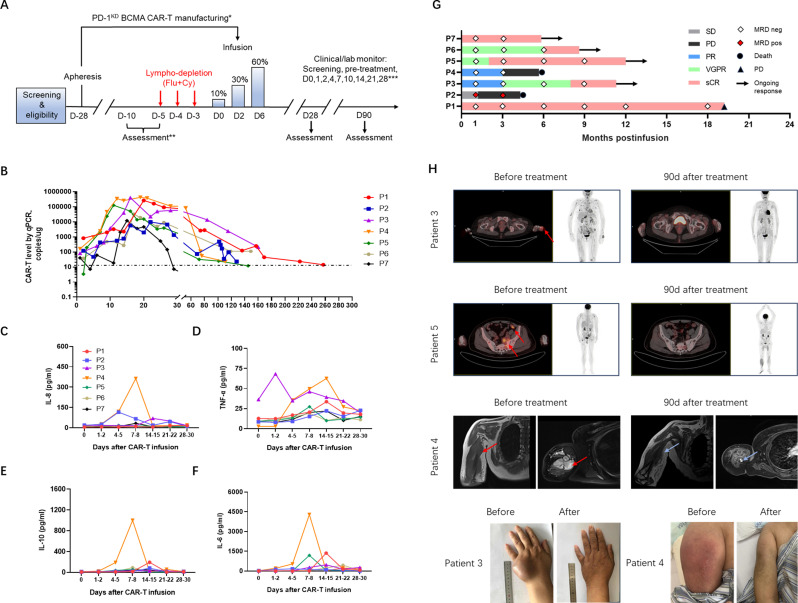

PD-1KD BCMA CAR-T cells exhibited comparable tolerability and efficacy in patients with RRMM

To explore the safety and efficacy of PD-1KD BCMA CAR-T cells as an antitumor treatment, we conducted a phase I clinical study in patients with RRMM (table 1). All included patients had undergone three or more prior therapies, including an immunomodulatory drug and a proteasome inhibitor. Specific therapies patients received before CAR-T cell are presented in online supplemental table 5. None of the patients had been previously exposed to BCMA or GPRC5D-directed therapies.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients and clinical response recieving PD-1KD BCMA CAR-T cell therapy

| Patient 1 | Patient 2 | Patient 3 | Patient 4 | Patient 5 | Patient 6 | Patient 7 | |

| Myeloma type | IgDλ | κ | IgG κ | Non-secretory | IgA κ | IgG κ | λ |

| ISS stage | II | II | II | II | III | III | I |

| R-ISS | II | II | NA | II | III | NA | II |

| Time since diagnosis (years) | 2.8 | 4 | 4 | 1 | 2.5 | 5.5 | 3.8 |

| High-risk cytogenetics (FISH) at diagnosis | N | del(17 p) | NA | t (11;14), del(17 p) | gain 1q21,t (4;14) | NA | del(17 p) |

| Prior lines of therapy | 4 | 6 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 3 | 6 |

| Alkylating therapy prior to CAR-T(month) | 4.3 | 1 | 4.5 | 1.8 | 2.2 | 8.4 | 3.7 |

| Extramedullary Diseases |

No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| Bone marrow plasma cell burden at infusion* (%) | 17.8 | 13.6 | 1.78 | 4.7 | 11.6 | 11.7 | 4 |

| BCMA expression† (%) | 100 | 100 | 96 | 98.9 | 99 | 85 | NA |

| Best response | sCR | SD | sCR | PR | CR | sCR | sCR |

| CRS grade | Grade 1 | – | Grade 2 | Grade 3 | Grade 2 | Grade 2 | – |

*Bone marrow plasma cell burden at infusion was determined by flow cytometry.

†BCMA expression indicated BCMA surface expression in plasma cells before CAR-T therapy which was determined by flow cytometry.

BCMA, B cell maturation antigen; CRS, cytokine release syndrome; ISS, International Staging System for Multiple Myeloma; NA, not available; PR, partial response; sCR, stringent complete response; SD, stable disease.

jitc-2023-008429supp006.pdf (79KB, pdf)

In the final infusion products, the CAR-positive rate ranged from 13.84% to 52.45% (median, 20.83%) (online supplemental figure 7A), and PD-1 expression on the CAR-T cell surface was significantly lower than that on the nonCAR-T cells (online supplemental figure 7C). The infusion products had a cell viability greater than 90% and could respond to and eradicate target tumor cells in vitro. Five days before CAR-T cell infusion, the patients received fludarabine (total dose of 25 mg/m2×3 days) and cyclophosphamide (total dose of 250 mg/m2×3 days) as a lymphodepleting preconditioning treatment. CAR-T cell infusion was split into three administrations of 0.1 (10%), 0.3 (30%), and 0.6×107 (60%) CARpositive cells per kg intravenously on days 0, 2, and 6, respectively (figure 6A). CAR-T cell persistence was monitored weekly by flow cytometry and qPCR analyses of peripheral blood samples. From 7 to 20 days after infusion, the proportion of CAR-T cells increased, indicating that these cells proliferated in vivo (figure 6B). Hematological toxic effects were found in all patients, including neutropenia, lymphopenia, anemia, and thrombocytopenia; these are expected toxic effects of lymphodepleting chemotherapy. Detail information about hematological toxicity can be found in online supplemental table 6. Cytokine release syndrome (CRS) was observed in five patients, four of whom had mild CRS (1–2 CRS) that was relieved by supportive care. Patient 4 with grade 3 CRS required tocilizumab and dexamethasone to control toxic reactions. CRS severity of CRS was significantly associated with increased cytokine levels (figure 6C–F). Immune effector cell-associated neurotoxicity syndrome did not occur (table 1). Disease burden generally declined early, within the first 2 months in six of the seven patients after infusion coincident with a rise in the number of circulating CAR-T cells (online supplemental figure 6A). Soluble BCMA (sBCMA) is also a marker of disease burden in multiple myeloma patients and sBCMA levels are correlated with treatment response.24 The sBCMA plasma levels decreased markedly in the responding patients within the first month (online supplemental figure 6B). In one patient with stable disease (SD), high levels of serum FLC and sBCMA were consistently detected after infusion. BM minimal residual disease (MRD) was assessed by flow cytometry with a sensitivity of 1 in 105. Six patients converted to MRD-negative status at the first postinfusion assessment on day 28. According to a previous study, early MRD positivity likely predicts impending clinical relapse.25

Figure 6.

Clinical efficacy of PD-1KD BCMA CAR-T cells in patients with RRMM. (A) Schematic diagram of the clinical PD-1KD BCMA CAR-T cell treatment regimen and clinical/laboratory monitoring. *Patients may receive therapy during manufacturing to maintain disease control. **After the first 28 days, follow-up was every 4 weeks up to 6 months and then every 3 months up to 2 years. ***Pre-tx, pretreatment, 3–7 days before CAR-T cell infusion. Flu indicates fludarabine. Cy indicates cyclophosphamide. (B) Measurements of CAR-T cells assessed by means of qPCR assay in peripheral blood of patients treated with cyclophosphamide/fludarabine combination conditioning and three-infusion CAR T delivery. (C–F) Cytokine concentrations in the serum of all patients who received infusions of PD-1KD BCMA CAR-T cells, as determined by ELISA. (G) Swimmer plot depicting each subjects’ response category over time and the results of MRD detection via flow cytometry on bone marrow aspirates. (H) Response of extramedullary lesion. Extramedullary infiltration lesions disappeared or were reduced after PD-1KD BCMA CAR-T cell infusion. Representative PET-CT images of patient 3 and patient 5 and MRIs of patient 4 before and after PD-1KD BCMA CAR-T cell treatment. Extramedullary diseases are indicated by red arrows. Light blue arrows indicate tumor reduction. BCMA, B cell maturation antigen; MRD, minimal residual disease; PR, partial response; RRMM, relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma; sCR, stringent complete response; SD, stable disease.

jitc-2023-008429supp007.pdf (84.3KB, pdf)

In our phase I clinical trials of CAR-T-cell treatment of the seven RRMM patients, the overall response rate (ORR) was 85.7% (6/7), and included four patients with an sCR, one patient with a CR, one patient with a PR and one patient with SD. Durable responses were found in four patients at the time of last follow-up, and disease relapse was detected in one patient at 19.2 months (figure 6G). Four of the seven (4/7, 57.1%) enrolled patients had at least one EMD. One patient was diagnosed with EMD and the remaining three patients relapsed with EMD. Prior to CAR-T therapy, typical osseous site was identified before the left side of the sacral bone wing (patient 5) while the extraosseous sites involved include lymph nodes (patient 2), muscle (patient 4), and soft tissue in the hepatic hilum area (patient 3). We observed significant shrinkage of EMDs (figure 6H). We also performed an immunophenotypic analysis for the characterization of different T cell populations (online supplemental figure 7D). We found an increase of Tem phenotype that mediate rapid effector functions in these highly responsive patients following infusion and declined thereafter. There was an obvious increase in the percentage of Tcm and Tn as well as a small increase in the percentage of Temra CAR-T cells (online supplemental figure 7E,F) from expansion peak to 28–35 days postinfusion. CAR-T cells from these patients showed a gradually predominantly Tcm and Tn compartments after infusion (online supplemental figure 7E,F).

Discussion

Despite the superior antitumor activity and prolonged survival of anti-BCMA CAR-T cells in patients with RRMM, there are still patients who do not response or relapse with CAR-T therapy partially due to the restricted T-cell duration and inhibitory immune microenvironment of MM, especially in patients with EMD.26 27 Moreover, the progression free survival (PFS) and OS of RRMM patients with EMD are poorer than those without EMD.28 29 To reduce T-cell dysfunction, reverse the inhibitory immune microenvironment, and thus enhance the ORR in RRMM patients with EMD, new CAR-T cell design is constantly needed.

In this study, we developed a BCMA CAR-T cell product that carried an anti-PD-1 shRNA cassette and incorporated an OX-40 costimulatory domain into the CAR construct. Our previously established computational method was adopted to optimize the sequences of shRNAs for accuracy and efficiency purposes.30 Based on the AI technology guiding,31 we selected and confirmed an optimal PD-1-specific shRNA sequence. OX-40 was incorporated into the CAR construct as a costimulatory signal to achieve greater proliferation and enhanced immune memory development in a repeated stimulation assay using BCMA-expressing target cells.23 30 32–36 Notably, we established a mouse model of MM using our previously constructed BCMA+luciferase+ K562 cells to evaluate the proliferation and antitumor capacity of BCMA CAR-T cells in vivo.23 This is because K562 cells lack the MHC-I expression and do not activate TCR-mediated signaling pathways in CD8+CAR-T cells, thus these cells can eliminate any confounding effects.37

Compared with the widely used second-generation CAR-T cells, our approach has several advantages since the blockade of PD-1/PD-L1 signaling enhanced CAR-T-cell proliferation and cytotoxicity in an inhibitory tumor microenvironment. The two-in-one construct avoids the need for multiple administrations of ICB antibodies and ensures safety in clinical trials. Additionally, the synergistic signals provided by PD-1 knockdown and OX40 costimulation maintained a memory phenotype and reduced exhaustion in CAR-T cells after repetitive antigen exposure.

Our analysis revealed that PD-1 inhibition endowed BCMA CAR-T cells with better effector function and a greater proliferative capacity after transient antigen stimulation. Furthermore, this CAR-T cell design induced more memory T-cell and made CAR-T cells less exhausted phenotypes during repetitive antigen challenges. Reduced apoptosis was also found in the PD-1KD BCMA CAR-T cell group, and this reduction appeared to be associated with an increased proportion of Tcm cells. Previous studies have shown that Tcm cells are critical for in vivo expansion, survival, and long-term persistence.38 39 For adoptive T cell therapy, CAR-T cells from naive and Tcm subsets exhibit superior antitumor activity compared with those from the effector subset in vivo.40–42

Further investigation into the mechanisms underlying this superiority revealed that PD-1KD BCMA CAR-T cells exhibited increased expression of TCF-7, which is an important regulator of self-renewal and memory differentiation. Moreover, memory-related genes, such as CD62L and CCR7, were upregulated after repetitive antigen stimulation. Zhang Jiqin et al recently reported that CAR-T cells with PD1 interference through nonviral, PD1 integration also resulted in a high percentage of memory T cells in infusion products.43 OX-40 can reduce T-cell apoptosis after activation.32 44 45 The addition of the PD-1 inhibition exerted relatively stronger antiapoptotic and central memory-inducing effects on these CAR-T cells. Overall, our preclinical study indicated that PD-1KD BCMA CAR-T cells have improved antitumor efficacy both in vivo and in vitro. We will further explore the unique features of this BCMA CAR-T cell product, including the relationship between PD-1 and TCF7 in memory differentiation, the synergistic effects between PD-1 and OX40 signaling in T-cell persistence, and key downstream effector molecules.

With the favorable biological properties exhibited by our BCMA CAR-T cells, we conducted a phase I clinical trial in patients with RRMM. Favorable safety was found in these patients. Grade 1–3 CRS was observed in some patients, and only one patient experienced grade 3 CRS. For this patient, high disease burden increased the risk of developing severe CRS9 46 47 with several large extramedullary bulks in the limbs measuring 14 cm at the greatest diameter. Early intervention with tocilizumab and the addition of corticosteroids successfully rescued grade 3 CRS symptoms in this patient. Clinicians could consider early intervention for patients at high risk of developing severe CRS, including patients with bulky disease or a high tumor burden.47 No neurological toxicity was observed in these patients. The ORR rate was comparable between patients with and without EMD, and there was no difference in the occurrence of adverse events. These results indicate the opportunity for the adoptive transfer of PD-1KD anti-BCMA CAR T cells for RRMM patients with EMD. CAR-T cell phenotype analysis suggested that CAR-T cells underwent a switch to the Tem phenotype during early the response phase. By 28–35 days after infusion, CAR-T cells had preserved a memory phenotype (Tcm and stem cell memory (Tscm) cells). Similar immunophenotypic characteristics have been described by Biasco et al 48 in patients with long-term CAR-T cell persistence.

Nevertheless, there are several limitations in our study. The precise relationship between PD-1 and TCF7 in the generation of central memory CAR-T cells has not been determined, and further studies are required to determine the molecular mechanisms involved. Limitations also include the small sample size and lack of a BCMA CAR-T-based CAR-T cell control group in the clinical trial. A larger, multicenter clinical trial and longer follow-up are necessary to validate these findings in patients.

In summary, we developed a CAR construct containing an anti-PD-1 shRNA sequence and an OX-40 costimulatory domain. This strategy provides CAR-T cells distinct functional properties and protects them from the inhibitory tumor microenvironment caused by the PD-1/PD-L axis. These characteristics have led to enhanced antitumor efficacy in preclinical mouse models of MM and in clinical trials. Thus, our study provides an alternative approach to improve the antitumor efficacy of CAR-T cells and enables their application in other tumors, including solid tumors, by counteracting the markedly immunosuppressive milieu.

Materials and methods

Clinical trial information and design

This study was a phase 1, open-label, single-arm clinical trial designed to evaluate the safety and efficacy of PD-1-knockdown anti-BCMA CAR-T cells in RRMM patients. The clinical trial was registered at chictr.org (ChiCTR1900028573). The inclusion criteria were as follows: age of 18–75 years old; hand an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance-status score of 0 or 1 (on a scale of 0–5, with higher scores indicating greater disability); had measurable disease, defined by a concentration of monoclonal protein (M protein) in the serum of at least 0.5 g per deciliter or in the urine of at least 200 mg per 24 hours, had serum free light chains (involved a free light chain concentration of ≥10 mg per deciliter with abnormal ratio), or more than 30% BM plasma cells; had at least three previous lines of therapy, including a proteasome inhibitor and an immunomodulatory agent, or disease refractory to both drug classes; and adequate organ function. Cyclophosphamide-based lymphodepleting chemotherapy was used as the conditioning regimen. Cyclophosphamide (250 mg/m2, intravenous, daily) and fludarabine (25 mg/m2, intravenous, daily) were administered for 3 days. CAR-T cell intravenous infusion took place 5 days after the start of the conditioning regimen. The starting day for CAR-T cells infusion was considered day 0. To preliminarily assess the safety and effectiveness of this new CAR-T cell therapy, seven patients who had not previously been treated with CAR-T cell therapy were enrolled in the cohort. According to our previous experience,5 three infusions of a total 1×107 CAR-T cells per kg were given on days 0, 2, and 6 (10% of the total dose on day 0, 30% on day 2 and 60% on day 6). The characteristics, clinical responses and prior therapies of the patients are shown in table 1.

Response assessment

Treatment response was assessed according to the International Myeloma Working Group consensus criteria for response and MRD assessment.49 Patients were closely followed up with BM cytological or biopsy examination for plasma cells, MRD detection by FACS analysis of the BM, pathological evaluation of an extramedullary plasmacytoma, serum protein electrophoresis, Ig and LC immunofixation of serum and urine, serum FLC, bone radiography or MR, or systemic PET-CT scanning.

Assessment and grading of the CRS

The levels of serum cytokines, including IL-6, IL-8, IL-10 and TNFα, were detected via ELISA according to the manufacturer′s instructions (R&D Systems, Bio-Techne) within 1 month of infusion. CRS was assessed and graded according to the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (NCI-CTCAE) V.5.0 in combination with other methods.

Assessment and grading of neurological toxicity

Neurological toxicity was assessed and graded according to the NCI-CTCAE V.5.0. Once CRS symptoms such as fever, hypotension, capillary leakage or other types of AEs were observed, the patient was closely monitored for signs of neurological toxicity, such as seizure, tremor, encephalopathy or dysphasia.

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemical (IHC) analysis was performed on formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue sections. In brief, after the sections were deparaffinized in xylene and rehydrated in a graded alcohol series, endogenous peroxidase was blocked with 3% hydrogen peroxide. Antigen retrieval was performed using EDTA buffer (pH 9.0). After rinsing the sections in PBS, antibodies against human BCMA (Abcam, ab5972), PD-L1 (Agilent, sk00621) and PD-L2 (Abcam, ab244332) were used for IHC staining. Staining was carried out on an automated immunostainer (Leica Bond-III, Dako Autostainer Link 48) using a Bond Polymer Refine Detection system.

Multiplex immunofluorescence staining

For fluorescent multiplex IHC (mIHC), a three-color fluorescence kit based on tyramide signal amplification (TSA) was used following the manufacturer′s protocol. In brief, tissue sections were incubated with primary antibodies as described in the above IHC protocol for two or three sequential cycles before the application of the corresponding secondary antibodies and a TSA solution. After the last TSA cycle, DAPI was used for counterstaining at a dilution of 1:1000 for 10 min. Fluorescence microscopy images (300 ms exposure time) were obtained with an AxioImager.Z2 microscope (Carl Zeiss).

Measurement of soluble BCMA levels

The Human BCMA/TNFRSF17 ELISA Kit (R&D Systems, DY193E) is a solid-phase sandwich ELISA designed to detect and quantify the level of human BCMA in cell culture supernatants, plasma, and serum. ELISA was performed according to the manufacturer′s instructions using the BCMA protein standard. sBCMA levels are reported as the mean of triplicate samples for each specimen.

Cell lines

HEK293T and K562 cells were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection. RPMI-8226 and MM.1S cells were purchased from the Cell Bank of the Chinese Academy of Sciences. All cell lines were authenticated by short tandem repeat profiling. RPMI-8226 and MM.1S cells stably expressing firefly luciferase (ffLuc) were established by lentiviral infection. K562 cells stably expressing BCMA and firefly luciferase (ffLuc) were generated by lentiviral infection. K562 cells stably expressing BCMA, PD-L1 and ffLuc were generated using a lentiviral vector containing a coexpression cassette for PD-L1 and ffLuc. All the stable cell lines were selected with puromycin. All cell lines were regularly tested to ensure that they were free of mycoplasma contamination.

Isolation and expansion of human primary T cells

Fresh peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were isolated from healthy donors at Ruijin Hospital. Recruitment of healthy human blood donors was approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of Ruijin Hospital. All the donors signed an informed consent form. Fresh PBMCs were collected by apheresis from patients. PBMCs were isolated by density gradient centrifugation using Ficoll (Sigma-Aldrich, GE17-1440). T cells were enriched through magnetic separation using anti-CD4 and anti-CD8 microbeads (Miltenyi Biotec, 130-045-101, 130-045-201) and activated with T Cell TransAct (Miltenyi Biotec, 130-111-160). T cells were cultured in AIM-V medium (Gibco) supplemented with 10% autologous human serum and 100 IU/mL human IL-2 (PeproTech, 200-02). The cells were collected once the cell number reached the requirement for administration; then, the cells were washed, formulated and cryopreserved.

Development of AI technology a PD-1-specific shRNA sequence

We present an interpretable classification model for shRNA target prediction using the Light Gradient Boosting Machine algorithm called ILGBMSH. Rather than using only the shRNA sequence feature, we extracted 554 biological and deep learning features. We evaluated the performance of our model compared with that of other state-of-the-art shRNA target prediction models. In addition, we investigated the features explained by the model′s parameters and interpretable method called Shapley additive explanations, which provided us with biological insights from the model. We used independent shRNA experimental data from other resources to determine the predictive ability and robustness of our model.

Construction of the CAR cassette and generation of CAR-T cells

CARs targeting human BCMA were used in this study. Briefly, the CAR comprised an scFv fragment, C11D5.3,50–52 specific for human BMCA antigen preceded by a CD8 signal peptide (UniProt: P01732-1, aa 138-206), a CD8a hinge-transmembrane region (UniProt: P01732-1, aa 138-206), a human CD3z intracellular domain (UniProt: P20963-1, aa 52-164), the cytoplasmic region of OX40 (UniProt: P10747-1, aa 180-220) costimulatory domain, and a shRNA sequences targeting the 3′ untranslated region of the human PD-1 gene (shRNA sequence: GCTTCGTGCTAAACTGGTA). Transcription of the CAR was driven by the EF-1a promoter and terminated by the CD8α signal sequence. The CAR sequence was cloned and inserted into the fourth lentiviral vector backbone. A lentivirus was produced by transfecting 293 T cells with the CAR plasmid, pRSV-Rev, pMDLg/pRRE and pMD 2.G. Virus-containing supernatants were collected after 3 days to infect primary human T cells stimulated for 2–3 days.

Antigen stimulation and proliferation of CAR-T cells

CAR-T cells were labeled with CFSE (Thermo Fisher, C34554) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. As antigens for stimulation, target cells (RPMI-8226 cells, MM.1S cells and BCMA- or PD-L1/BCMA-expressing K562 cells) were pretreated with radiation. CAR-T cells were cocultured with target cells at an effector/target ratio of 1:1 for 5 days per stimulation. Then, the cells were collected and run on an LSRFortessa (BD Biosciences).

Luciferase-based cytotoxicity assays

To test the lysis of target cells, purified CAR-T cells were cocultured with target cells (RPMI-8226 cells, MM.1S cells and BCMA- or PD-L1/BCMA-expressing K562 cells) at different E:T ratios in 96-well plates. After 24 hours of coculture, 100 µL D-luciferin solution (300 µg/mL) was added to each well, and the signals were measured by a Varioskan LUX (Thermo Fisher). Lysis was evaluated with the following formula: % specific lysis=100−((value of sample)−(value of negative control))∕((value of positive control)−(value of negative control))×100.

Multiplex cytokine analyses

The levels of IL-2, IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, IFN-γ, TNF-ɑ and granzyme B in 24-hour coculture supernatants were measured with a customized human cytokine detection kit (R&D, LX-Luminex) via Luminex technology.

Repetitive stimulation assay

CAR-T cells were cultured in AIM-V medium (Gibco) supplemented with 10% autologous human serum and 100 IU/mL human IL-2 (PeproTech). Irradiated (100-gray) RPMI-8226 cells were used to stimulate CAR-T cells at a ratio of 1:1 (CAR+T cells:RPMI-8226 cells) for the first time on day 9 after viral transduction. The cells were monitored daily and fed according to the cell count every 3 days. After four rounds of stimulation, the CAR-T cells were subjected to apoptosis and T-cell subset analyses, and CAR+T cell sorting was performed using a BD FACSAria III SORP cell sorter for RNA-seq analysis.

Flow cytometry

CAR and membrane protein expression were determined by flow cytometry. Cells were prewashed and incubated with antibodies for 45 min on ice. After washing twice, the cells were resuspended in 1×PBS at a concentration of 1×106 cells/mL for further analysis. An apoptosis assay (Multi Sciences) was used to detect apoptosis in CAR+T cells cocultured with tumor cells. Cells were washed twice with cold PBS and resuspended in 1×binding buffer at a concentration of 1×106 cells/mL. Then, 100 µL of cell suspension (1×105 cells) was transferred to a 5 mL culture tube, and 5 µL of APC Annexin V and 10 µL of PI were added. The cells were gently vortexed and incubated for 15 minutes at room temperature (25°C) in the dark. Finally, 400 µL of 1×binding buffer was added to each tube. For evaluation of clinical samples, peripheral blood cells were stained with antibodies, followed by the addition of lysis buffer (BD Biosciences) before being run. The percentage of CAR+cells was analyzed in gated CD45+CD3+ cells.

The following antibodies were used: BV510-conjugated anti-human CD3, BV786-conjugated anti-human CD8, BV605-conjugated anti-human CD4, PE-conjugated anti-human CD62L, PE-Cy7-conjugated anti-human CD45RA, BV421-conjugated anti-human CD25, APC-R700-conjugated anti-human CD127 (CCR7), BV605-conjugated anti-human CD45RO, Alexa Fluor 647-conjugated anti-human PD1, APC-Cy7-conjugated anti-human CD45, PE-Cy5-conjugated anti-human CD19, BV650-conjugated anti-human CD3, PE-conjugated anti-human CD16, BV421-conjugated anti-human CD56, PE-Cy7-conjugated anti-human CD11B, BV480-conjugated anti-human CD14, BB 515-conjugated anti-human HLA-DR, BV605-conjugated anti-human CD15, BV786-conjugated anti-human CD33, APC-conjugated anti-human CD38, BV711-conjugated anti-human CD138, PE-CF 594-conjugated anti-human PD-L1, and APC Alexa-700-conjugated anti-human PD-L2. Alexa Fluor 700-conjugated anti-human CD45, APC-Cy7-conjugated anti-human CD3, Pacific Blue-conjugated anti-human CD8, Super Bright 600-conjugated anti-human CD4, PE-conjugated anti-human CD127 (CCR7), PerCP-Cy5.5-conjugated anti-human CD45RA, PE-conjugated anti-human TIM 3, PerCP-Cy5.5-conjugated anti-human PD-1, FITC-conjugated anti-human LAG3 and BV421-conjugated anti-human CTLA4 (all from BD Biosciences) For detection of CAR expression, APC-labeled human BCMA (BCA-HA2H5, ACRO Biosystems) or FITC-labeled human BCMA (BCA-HF254, ACRO Biosystems) was used.

All samples were run on an LSRFortessa (BD Biosciences) and analyzed with FlowJo software.

CAR copy number analysis by qPCR

Blood samples were collected before and after CAR-T-cell infusion. Lysis buffer (BD Biosciences) was added, and genomic DNA was extracted using a Genomic DNA Purification Kit (Thermo Fisher). A seven-point standard curve was generated by using 5×102–5×106 copies/μL of lentiviral vector DNA containing the CAR sequence. TaqMan qPCR assays were performed to measure CAR copy number in peripheral blood cells. qPCR was run on a QuantStudio 3 Real-Time PCR System (Thermo Fisher). Each sample was analyzed in triplicate. The following primers were used to specifically target the CAR sequence:

Forward, 5′-tgcactgtgtttgctgacgcaa-3′.

Reverse, 5′-atgagttccgccgtggcaata-3′.

Probe, 5′-cattgccaccacctgtcagctcctttcc-3′.

RNA-sequencing and data analysis

All the experiments were performed with two biological replicates. RNA was extracted from 1×106 CAR+T cells using an RNeasy Mini Kit (QIAGEN, 74106). mRNA library was constructed using a VAHTS Total RNA-seq library preparation Kit for Illumina (Vazyme, NR601) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Libraries were sequenced on an Illumina NovaSeq 6000 sequencer for PE150 cycles. Sequencing reads were aligned to the human reference genome (GRCh38) using Kallisto (V.0.46.0). The DESeq2 R package (V.1.34.0) was used for normalizing the RNA read counts (transcripts per million, TPM) and analyzing differential gene expression. GSEA was performed using GSEA V.4.3.2 software (https://www.gsea-msigdb.org/gsea/index.jsp), and plots were generated with the ggplot2 package (V.3.3.6) in R.

Animals and in vivo procedures

Mice were maintained under pathogen-free conditions, and food and water were provided ad libitum. All mice used were females aged 5–6 weeks. To evaluate the antitumor activity of PD-1KD BCMA-targeted CAR-T cells in vivo, female mice were inoculated with 5×106 PD-L1/BCMA+K562 cells intravenously. Approximately 7 days later, 1×107 CAR-T cells or a PBS control were infused intravenously, and animal survival was monitored over time. The mice were anesthetized and injected with 200 µL of luciferin i.p. (15 mg/mL, YEASEN, 40 901ES). Bioluminescence images were acquired 10 min after luciferin injection and analyzed using the IVIS Imaging System and software (PerkinElmer).

Statistical analysis and reproducibility

All in vitro experiments were performed with at least three biological replicates. Experimental data are presented as the mean±SD or the mean±SE as described in the figure legends. Two-group comparisons were performed by a two-tailed Student’s t-test or two-tailed Mann-Whitney test, and more than two groups were compared by one-way analysis of variance with Tukey’s post hoc test using GraphPad software. A p<0.05 was considered statistically significant. Asterisks are used to indicate significance: ****p<0.0001, ***p<0.001, **p<0.01, and *p<0.05. NS, not significant. All the error bars, group numbers and explanations of the significant values are presented within the figure legends.

Acknowledgments

We thank all the laboratory staff at Shanghai Institute of Hematology, State Key Laboratory of Medical Genomics, National Research Center for Translational Medicine at Shanghai, Ruijin Hospital,Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine, Shanghai, China. We thank the patients who volunteered to participate in the study, their families and caregivers, the physicians and nurses who cared for the patients and supported this clinical trial.

Footnotes

WO, S-WJ, NX and W-YL contributed equally.

Contributors: WO, FL, LY, ZL and J-QM designed the study. WO, NX, HZ, LZ and LK conducted experiments and performed the analysis. S-WJ, W-YL, YT, YL, YW and JW performed clinical data collection and interpretation. FL, LY, ZL and J-QM performed conceptualization and supervised the project. WO, S-WJ, NX and W-YL wrote the manuscript with input from all coauthors. All authors have read, reviewed, and edited the manuscript and approved the final version for submission. Guarantor: J-QM.

Funding: This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82070227 and 82073800) and was additionally supported by the Shanghai Municipal Hospital Development Center (SHDC2020CR2066B).

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

The trial was approved by the institutional review board, and all patients provided written informed consent in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki before enrolment. The clinical protocol was reviewed and approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of the Ruijin Hospital (ID: 2019-164). All mouse experiments were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee in accordance with institutional and National Institutes of Health protocols and guidelines, and all studies were performed according to the animal care standards (DLA-MP-IACUC.06) from the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of Shanghai Jiao-Tong University School of Medicine (Shanghai, China). NOD CRISPR Prkdc IL2r (NCG) mice were purchased from GemPharmatech.

References

- 1. Berdeja JG, Madduri D, Usmani SZ, et al. Ciltacabtagene autoleucel, a B-cell maturation antigen-directed chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy in patients with relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma (CARTITUDE-1): a phase 1b/2 open-label study. Lancet 2021;398:314–24. 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00933-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Raje N, Berdeja J, Lin Y, et al. Anti-BCMA CAR T-cell therapy bb2121 in relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med 2019;380:1726–37. 10.1056/NEJMoa1817226 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Maude SL, Laetsch TW, Buechner J, et al. Tisagenlecleucel in children and young adults with B-cell lymphoblastic leukemia. N Engl J Med 2018;378:439–48. 10.1056/NEJMoa1709866 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Park JH, Rivière I, Gonen M, et al. Long-term follow-up of CD19 CAR therapy in acute lymphoblastic leukemia. N Engl J Med 2018;378:449–59. 10.1056/NEJMoa1709919 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Xu J, Chen L-J, Yang S-S, et al. Exploratory trial of a biepitopic CAR T-targeting B cell maturation antigen in relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2019;116:9543–51. 10.1073/pnas.1819745116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Zhao W-H, Wang B-Y, Chen L-J, et al. Four-year follow-up of LCAR-B38M in relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma: a phase 1, single-arm, open-label, multicenter study in China (LEGEND-2). J Hematol Oncol 2022;15:86. 10.1186/s13045-022-01301-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Mi J-Q, Zhao W, Jing H, et al. Phase II, open-label study of ciltacabtagene autoleucel, an anti-B-cell maturation antigen chimeric antigen receptor-T-cell therapy, in Chinese patients with relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma (CARTIFAN-1). J Clin Oncol 2023;41:1275–84. 10.1200/JCO.22.00690 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. van de Donk N, Themeli M, Usmani SZ. Determinants of response and mechanisms of resistance of CAR T-cell therapy in multiple myeloma. Blood Cancer Discov 2021;2:302–18. 10.1158/2643-3230.BCD-20-0227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. D’Agostino M, Raje N. Anti-BCMA CAR T-cell therapy in multiple myeloma: can we do better? Leukemia 2020;34:21–34. 10.1038/s41375-019-0669-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Rafiq S, Hackett CS, Brentjens RJ. Engineering strategies to overcome the current roadblocks in CAR T cell therapy. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2020;17:147–67. 10.1038/s41571-019-0297-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Shah NN, Fry TJ. Mechanisms of resistance to CAR T cell therapy. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2019;16:372–85. 10.1038/s41571-019-0184-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Milone MC, Xu J, Chen S-J, et al. Engineering enhanced CAR T-cells for improved cancer therapy. Nat Cancer 2021;2:780–93. 10.1038/s43018-021-00241-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Keir ME, Butte MJ, Freeman GJ, et al. PD-1 and its ligands in tolerance and immunity. Annu Rev Immunol 2008;26:677–704. 10.1146/annurev.immunol.26.021607.090331 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Shimizu K, Sugiura D, Okazaki I-M, et al. PD-1 imposes qualitative control of cellular transcriptomes in response to T cell activation. Mol Cell 2020;77:937–50. 10.1016/j.molcel.2019.12.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. He X, Xu C. PD-1: a driver or passenger of T cell exhaustion? Mol Cell 2020;77:930–1. 10.1016/j.molcel.2020.02.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Wherry EJ, Kurachi M. Molecular and cellular insights into T cell exhaustion. Nat Rev Immunol 2015;15:486–99. 10.1038/nri3862 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bengsch B, Johnson AL, Kurachi M, et al. Bioenergetic insufficiencies due to metabolic alterations regulated by the inhibitory receptor PD-1 are an early driver of CD8+ T cell exhaustion. Immunity 2016;45:358–73. 10.1016/j.immuni.2016.07.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Staron MM, Gray SM, Marshall HD, et al. The transcription factor FoxO1 sustains expression of the inhibitory receptor PD-1 and survival of antiviral CD8+ T cells during chronic infection. Immunity 2014;41:802–14. 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.10.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Adusumilli PS, Zauderer MG, Rivière I, et al. A phase I trial of regional mesothelin-targeted CAR T-cell therapy in patients with malignant pleural disease, in combination with the anti-PD-1 agent pembrolizumab. Cancer Discov 2021;11:2748–63. 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-21-0407 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Chong EA, Melenhorst JJ, Lacey SF, et al. PD-1 blockade modulates chimeric antigen receptor (CAR)–modified T cells: refueling the CAR. Blood 2017;129:1039–41. 10.1182/blood-2016-09-738245 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hill BT, Roberts ZJ, Xue A, et al. Rapid tumor regression from PD-1 inhibition after anti-CD19 chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy in refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Bone Marrow Transplant 2020;55:1184–7. 10.1038/s41409-019-0657-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Cherkassky L, Morello A, Villena-Vargas J, et al. Human CAR T cells with cell-intrinsic PD-1 checkpoint blockade resist tumor-mediated inhibition. J Clin Invest 2016;126:3130–44. 10.1172/JCI83092 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Tan J, Jia Y, Zhou M, et al. Chimeric antigen receptors containing the OX40 signalling domain enhance the persistence of T cells even under repeated stimulation with multiple myeloma target cells. J Hematol Oncol 2022;15:39. 10.1186/s13045-022-01244-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Munshi NC, Anderson LD, Shah N, et al. Idecabtagene vicleucel in relapsed and refractory multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med 2021;384:705–16. 10.1056/NEJMoa2024850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Bansal R, Baksh M, Larsen JT, et al. Prognostic value of early bone marrow MRD status in CAR-T therapy for myeloma. Blood Cancer J 2023;13:47. 10.1038/s41408-023-00820-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Wang B, Liu J, Zhao W-H, et al. Chimeric antigen receptor T cell therapy in the relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma with extramedullary disease--a single institution observation in China. Blood 2020;136:6. 10.1182/blood-2020-140243 32614958 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Li W, Liu M, Yuan T, et al. Efficacy and follow‐up of humanized anti‐BCMA CAR‐T cell therapy in relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma patients with extramedullary‐extraosseous, extramedullary‐bone related, and without extramedullary disease. Hematol Oncol 2022;40:223–32. 10.1002/hon.2958 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Zhang M, Zhou L, Zhao H, et al. Risk factors associated with durable progression-free survival in patients with relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma treated with anti-BCMA CAR T-cell therapy. Clin Cancer Res 2021;27:6384–92. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-21-2031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Deng H, Liu M, Yuan T, et al. Efficacy of humanized anti-BCMA CAR T cell therapy in relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma patients with and without extramedullary disease. Front Immunol 2021;12:720571. 10.3389/fimmu.2021.720571 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Willoughby J, Griffiths J, Tews I, et al. OX40: structure and function - what questions remain? Mol Immunol 2017;83:13–22. 10.1016/j.molimm.2017.01.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Zhao C, Xu N, Tan J, et al. ILGBMSH: an interpretable classification model for the shRNA target prediction with ensemble learning algorithm. Brief Bioinform 2022;23:bbac429. 10.1093/bib/bbac429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Rogers PR, Song J, Gramaglia I, et al. OX40 promotes Bcl-xL and Bcl-2 expression and is essential for long-term survival of CD4 T cells. Immunity 2001;15:445–55. 10.1016/s1074-7613(01)00191-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Song J, So T, Cheng M, et al. Sustained survivin expression from OX40 costimulatory signals drives T cell clonal expansion. Immunity 2005;22:621–31. 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.03.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Salek-Ardakani S, Song J, Halteman BS, et al. OX40 (CD134) controls memory T helper 2 cells that drive lung inflammation. J Exp Med 2003;198:315–24. 10.1084/jem.20021937 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. So T, Song J, Sugie K, et al. Signals from OX40 regulate nuclear factor of activated T cells c1 and T cell helper 2 lineage commitment. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2006;103:3740–5. 10.1073/pnas.0600205103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Song J, Salek-Ardakani S, So T, et al. The kinases aurora B and mTOR regulate the G1-S cell cycle progression of T lymphocytes. Nat Immunol 2007;8:64–73. 10.1038/ni1413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Altvater B, Landmeier S, Pscherer S, et al. 2B4 (CD244) signaling by recombinant antigen-specific chimeric receptors costimulates natural killer cell activation to leukemia and neuroblastoma cells. Clin Cancer Res 2009;15:4857–66. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-2810 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Berger C, Jensen MC, Lansdorp PM, et al. Adoptive transfer of effector CD8+ T cells derived from central memory cells establishes persistent T cell memory in primates. J Clin Invest 2008;118:294–305. 10.1172/JCI32103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Gattinoni L, Lugli E, Ji Y, et al. A human memory T cell subset with stem cell-like properties. Nat Med 2011;17:1290–7. 10.1038/nm.2446 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Sommermeyer D, Hudecek M, Kosasih PL, et al. Chimeric antigen receptor-modified T cells derived from defined CD8+ and CD4+ subsets confer superior antitumor reactivity in vivo. Leukemia 2016;30:492–500. 10.1038/leu.2015.247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Depil S, Duchateau P, Grupp SA, et al. 'Off-the-shelf' allogeneic CAR T cells: development and challenges. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2020;19:185–99. 10.1038/s41573-019-0051-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Fraietta JA, Lacey SF, Orlando EJ, et al. Determinants of response and resistance to CD19 chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cell therapy of chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Nat Med 2018;24:563–71. 10.1038/s41591-018-0010-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Zhang J, Hu Y, Yang J, et al. Non-viral, specifically targeted CAR-T cells achieve high safety and efficacy in B-NHL. Nature 2022;609:369–74. 10.1038/s41586-022-05140-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Arch RH, Thompson CB. 4-1BB and Ox40 are members of a tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-nerve growth factor receptor subfamily that bind TNF receptor-associated factors and activate nuclear factor kappaB. Mol Cell Biol 1998;18:558–65. 10.1128/MCB.18.1.558 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Kawamata S, Hori T, Imura A, et al. Activation of OX40 signal transduction pathways leads to tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated factor (TRAF) 2- and TRAF5-mediated NF-kappaB activation. J Biol Chem 1998;273:5808–14. 10.1074/jbc.273.10.5808 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Hay KA, Hanafi L-A, Li D, et al. Kinetics and biomarkers of severe cytokine release syndrome after CD19 chimeric antigen receptor-modified T-cell therapy. Blood 2017;130:2295–306. 10.1182/blood-2017-06-793141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Jain MD, Smith M, Shah NN. How I treat refractory CRS and ICANS after CAR T-cell therapy. Blood 2023;141:2430–42. 10.1182/blood.2022017414 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Biasco L, Izotova N, Rivat C, et al. Clonal expansion of T memory stem cells determines early anti-leukemic responses and long-term CAR T cell persistence in patients. Nat Cancer 2021;2:629–42. 10.1038/s43018-021-00207-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Kumar S, Paiva B, Anderson KC, et al. International myeloma working group consensus criteria for response and minimal residual disease assessment in multiple myeloma. Lancet Oncol 2016;17:e328–46. 10.1016/S1470-2045(16)30206-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Zah E, Nam E, Bhuvan V, et al. Systematically optimized BCMA/CS1 bispecific CAR-T cells robustly control heterogeneous multiple myeloma. Nat Commun 2020;11:2283. 10.1038/s41467-020-16160-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Yan Z, Cao J, Cheng H, et al. A combination of humanised anti-CD19 and anti-BCMA CAR T cells in patients with relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma: a single-arm, phase 2 trial. Lancet Haematol 2019;6:e521–9. 10.1016/S2352-3026(19)30115-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Carpenter RO, Evbuomwan MO, Pittaluga S, et al. B-cell maturation antigen is a promising target for adoptive T-cell therapy of multiple myeloma. Clin Cancer Res 2013;19:2048–60. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-2422 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

jitc-2023-008429supp001.pdf (814.4KB, pdf)

jitc-2023-008429supp002.pdf (78.4KB, pdf)

jitc-2023-008429supp003.pdf (72.7KB, pdf)

jitc-2023-008429supp004.pdf (73.2KB, pdf)

jitc-2023-008429supp005.pdf (73.3KB, pdf)

jitc-2023-008429supp006.pdf (79KB, pdf)

jitc-2023-008429supp007.pdf (84.3KB, pdf)