Abstract

Objective

To assess how achievement of increasingly stringent clinical response criteria and disease activity states at week 52 translate into changes in core domains in patients with non-radiographic (nr-) and radiographic (r-) axial spondyloarthritis (axSpA).

Methods

Patients in BE MOBILE 1 and 2 achieving different levels of response or disease activity (Assessment of SpondyloArthritis International Society (ASAS) and Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Score (ASDAS) response criteria, Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index (BASDAI50)) at week 52 were pooled, regardless of treatment arm. Associations between achievement of these endpoints and change from baseline (CfB) in patient-reported outcomes (PROs) measuring core axSpA domains, including pain, fatigue, physical function, overall functioning and health, and work and employment, were assessed.

Results

Achievement of increasingly stringent clinical efficacy endpoints at week 52 was generally associated with sequentially greater improvements from baseline in all PROs. Patients with nr-axSpA achieving ASAS40 demonstrated greater improvements (CfB) than patients who did not achieve ASAS40 but did achieve ASAS20, in total spinal pain (−5.3 vs −2.8, respectively), Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness-Fatigue subscale (12.7 vs 6.7), Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Function Index (−3.9 vs −1.8), European Quality of Life 5-Dimension 3-Level Version (0.30 vs 0.16), Work Productivity and Activity Impairment-axSpA presenteeism (−35.4 vs −15.9), overall work impairment (−36.5 vs −12.9), activity impairment (−39.0 vs −21.0) and sleep (9.0 vs 3.9). Results were similar for ASDAS and BASDAI50. Similar amplitudes of improvement were observed between patients with nr-axSpA and r-axSpA.

Conclusions

Patients treated with bimekizumab across the full axSpA disease spectrum, who achieved increasingly stringent clinical response criteria and lower disease activity at week 52, reported larger improvements in core axSpA domains.

Keywords: Patient Reported Outcome Measures; Health-Related Quality Of Life; Spondylitis, Ankylosing; Therapeutics

WHAT IS ALREADY KNOWN ON THIS TOPIC

Axial spondyloarthritis (axSpA) is a chronic inflammatory disease affecting the axial skeleton, conferring a severe burden on patients’ lives.

Integration of the patient perspective into clinical practice is critical to maximising patients’ overall functioning and health.

A range of instruments exist to assess axSpA core domains, including patient-reported outcomes, to evaluate novel treatments in clinical trials.

It is essential to take a holistic view of the efficacy of treatments, not only on disease activity, but also in other spheres of patients’ lives.

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS

This analysis assessed the associations between achievement of different levels of response or disease activity at week 52 and change from baseline in patient-reported outcomes relating to the axSpA core domains of pain, fatigue, physical function, overall functioning and health, and work and employment.

Achievement of increasingly stringent clinical efficacy endpoints at week 52 was generally associated with sequentially greater improvements from baseline in all patient-reported outcomes.

Similar amplitudes of improvement were observed across the full disease spectrum of axSpA.

HOW THIS STUDY MIGHT AFFECT RESEARCH, PRACTICE OR POLICY.

The results of this analysis may aid in interpretation of clinical response criteria by demonstrating the level of improvement, which can be expected for different clinical response levels.

Understanding how the achievement of established treatment targets translates into changes in other core domains may help guide treatment decisions aimed at obtaining the best possible health-related quality of life, in line with Assessment of SpondyloArthritis International Society-European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology recommendations for axSpA.

Introduction

Axial spondyloarthritis (axSpA) is a chronic inflammatory disease affecting the sacroiliac joints (SIJ) and spine.1 The axSpA disease spectrum includes radiographic axSpA (r-axSpA, ie, ankylosing spondylitis),2 in which patients display definitive structural damage to the SIJ on pelvic radiographs, and non-radiographic axSpA (nr-axSpA), in which they do not.1 3

There are a wide range of clinical manifestations of axSpA, which impart a substantial burden on patients.4 Clinical trials of novel treatments for axSpA typically evaluate efficacy using composite clinical response or disease activity measures, such as Assessment of SpondyloArthritis International Society (ASAS) response criteria (including ASAS ≥40% improvement (ASAS40)) and Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Score (ASDAS). While the former is commonly used, ASDAS has been recommended by the ASAS and demonstrates improved sensitivity compared with ASAS40.5–16 However, while these composite endpoints capture a variety of disease features, they do not indicate how individual core domains are impacted by the disease or affected by treatment. Irrespective of radiographic classification, chronic back pain, stiffness and fatigue are major contributors to the high disease burden of axSpA.1 17 18 These symptoms limit physical function and can impair other aspects of patients’ lives, including work productivity and sleep, ultimately contributing to impaired health-related quality of life (HRQoL).17 19–21

The updated ASAS core outcome set includes the following seven mandatory core domains and corresponding recommended instruments: disease activity (ASDAS, patient global assessment of disease activity), pain including overall pain, peripheral pain and/or spinal pain (Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index (BASDAI) question 2), morning stiffness (mean of BASDAI questions 5 and 6), fatigue (BASDAI question 1), physical function (Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Function Index (BASFI)), overall functioning and health (ASAS Health Index (ASAS-HI)), and adverse events including death.15 18 Spinal mobility, sleep, and work and employment are categorised as important domains and are included in the ASAS core outcome set.18 Evaluating a range of domains allows for a comprehensive and holistic assessment of disease severity and treatment efficacy.22–28 Further, understanding how the achievement of established treatment targets, such as ASAS40 and ASDAS low disease activity (LDA), translates into changes in other core domains may help to guide treatment decisions and to assist in obtaining the best possible HRQoL, in line with ASAS-European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology (EULAR) recommendations for axSpA.5

Bimekizumab is a monoclonal IgG1 antibody that selectively inhibits interleukin (IL)-17F in addition to IL-17A, which are both independent pivotal drivers of inflammation in axSpA.29 30 Subcutaneous bimekizumab administered every 4 weeks demonstrated sustained efficacy, including improvements in disease activity, physical function and HRQoL to week 52 in patients with nr-axSpA and r-axSpA in the phase 3 BE MOBILE 1 and 2 studies, respectively.13

This post hoc analysis aimed to assess how achievement of increasingly stringent clinical response criteria and lower disease activity status levels at week 52 translate into changes in pain, fatigue, physical function, overall functioning and HRQoL, work productivity, and sleep in patients with axSpA receiving bimekizumab treatment in the BE MOBILE 1 and BE MOBILE 2 studies, irrespective of their initial treatment assignment.

Methods

Study design and patients

The study designs and inclusion and exclusion criteria for BE MOBILE 1 (NCT03928704) and 2 (NCT03928743) have been described previously.13 In BE MOBILE 1, patients with nr-axSpA, as determined by clinical diagnosis and fulfilment of ASAS classification criteria,31 were required to display either active sacroiliitis on MRI fulfilling ASAS criteria32 and/or elevated C reactive protein (CRP) ≥6.0 mg/L. In BE MOBILE 2, patients had r-axSpA fulfilling modified New York criteria.33 Patients also fulfilled ASAS classification criteria.31 Both studies comprised a 16-week placebo-controlled double-blind period, followed by a 36-week active-treatment maintenance period. In BE MOBILE 1, patients were randomised 1:1 to receive bimekizumab 160 mg or placebo every 4 weeks from week 16, then bimekizumab 160 mg every 4 weeks from week 16 to week 52. A similar protocol was used in BE MOBILE 2, however, for this study patients were randomised 2:1 in the placebo-controlled period (online supplemental figure 1).

rmdopen-2023-004040supp001.pdf (7.7MB, pdf)

Association analyses

Patients achieving various composite clinical efficacy endpoints (mutually exclusive groups) at week 52 were pooled, regardless of treatment arm. Clinical composite efficacy endpoints are defined in online supplemental table S1 and include ASAS response levels: <ASAS20 (ASAS20 not reached), ASAS20–<ASAS40 (reached ASAS20 but ASAS40 not reached), ≥ASAS40 (ASAS40 reached); ASDAS response levels: ASDAS reduction less than 1.1 (ie, change from baseline (CfB) >−1.1; referred to as ASDAS non-responder), ASDAS reduction greater or equal to 1.1 and less than 2.0 (ie, −2.0> CfB ≤−1.1 or ASDAS clinically important improvement (CII), but not major improvement (MI); referred to as ASDAS-CII–<MI for the remainder of the manuscript) and ASDAS reduction greater or equal to 2.0 (ie, ASDAS CfB ≤−2.0; referred to as ASDAS-MI)34; 50% improvement in BASDAI (BASDAI50) response: no, yes; ASAS partial remission (ASAS PR): no, yes; ASDAS disease activity levels: very high disease activity/HDA (vHDA/HDA; ASDAS ≥2.1), LDA (ASDAS ≥1.3–<2.1), inactive disease (ID; ASDAS <1.3).35 36

Associations between achievement of these composite clinical efficacy endpoints and CfB in patient-reported outcomes (PROs) measuring core axSpA domains at week 52 were assessed, including pain: total spinal pain (score range: 0–10; higher score indicates more severe levels of pain); fatigue: Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness (FACIT)-Fatigue subscale (score range: 0–52; higher score indicates less severe fatigue) and BASDAI question 1 (score range: 0–10; higher score indicates more severe levels of fatigue)37; physical function: BASFI (score range: 0–10; higher score indicates more impairment of physical function)38; overall functioning and health: European Quality of Life 5-Dimension 3-Level Version (EQ-5D-3L) UK tariff (score range: −0.594–1; higher scores indicate better health status),39 40 Ankylosing Spondylitis Quality of Life (ASQoL; score range: 0–18; higher score indicates worse HRQoL)41; Short-Form 36 Physical Component Summary (SF-36 PCS; score is standardised with a mean (SD) of 50 (10) in the general US population; higher scores indicate better physical ability and well-being)42; work and employment: Work Productivity and Activity Impairment (WPAI-axSpA43; percentage impairment while working (ie, presenteeism), work time missed (ie, absenteeism), overall work impairment (a combination of presenteeism and absenteeism), activity impairment (not at paid work) due to axSpA; higher scores indicate more impairment and less productivity); employment and presenteeism was assessed in patients in paid work, activity impairment was assessed in patients both in and out of work; sleep: Revised MOS Sleep Scale (MOS-Sleep-R) Index II (score is standardised with a mean (SD) of 50 (10) in the general US population; higher scores indicate better sleep function).44 Further information on each PRO measure is detailed in online supplemental text S1.

Statistical analyses

All analyses were performed on the randomised set of patients, by study, pooled irrespective of initial treatment arm. Data are reported as observed case (there was no imputation of missing data) and describe mean CfB with 95% confidence intervals (CI), for subgroups of patients defined by the achievement of mutually exclusive clinical efficacy endpoints (as described above) at week 52. These post hoc data are descriptive and thus no formal statistical testing was performed.

Results

Patient disposition and baseline disease characteristics

Almost all randomised patients completed week 16 (nr-axSpA: 244/254 (96.1%); r-axSpA: 322/332 (97.0%)) and week 52 (nr-axSpA: 220/254 (86.6%); r-axSpA: 298/332 (89.8%)). Baseline demographics and disease characteristics were largely comparable between patients with nr-axSpA and r-axSpA (table 1). A summary of the proportions of patients achieving composite clinical efficacy endpoints is presented in online supplemental table S2.

Table 1.

Patient demographics and baseline disease characteristics

| Mean (SD), unless otherwise stated | BE MOBILE 1 (nr-axSpA) n=254 | BE MOBILE 2 (r-axSpA) n=332 |

| Patient demographics | ||

| Sex, male, n (%) | 138 (54.3) | 240 (72.3) |

| Age, years | 39.4 (11.5) | 40.4 (12.3) |

| HLA-B27 positive, n (%) | 197 (77.6) | 284 (85.5) |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 27.4 (5.8) | 26.9 (5.8) |

| Baseline disease characteristics | ||

| Time since first symptoms of axSpA, years | 9.0 (8.8) | 13.5 (10.3) |

| ASDAS | 3.7 (0.7) | 3.7 (0.8) |

| ASDAS disease status | ||

| ASDAS-vHDA, n (%) ASDAS-HDA, n (%) ASDAS-LDA, n (%) ASDAS-ID, n (%) Missing, n (%) |

148 (58.3) 102 (40.2) 4 (1.6) 0 (0.0) 0 (0.0) |

197 (59.5) 131 (39.6) 3 (0.9) 0 (0.0) 1 (0.3) |

| BASDAI | 6.8 (1.3) | 6.5 (1.3) |

| BASFI | 5.4 (2.3) | 5.2 (2.1) |

| hs-CRP, mg/L, geometric mean (geometric CV, %) | 4.8 (261.8) | 6.6 (246.3) |

| hs-CRP>ULN,* n (%) | 141 (55.5) | 204 (61.4) |

| Total spinal pain | 7.2 (1.5) | 7.2 (1.5) |

| FACIT-Fatigue | 30.1 (10.7) | 31.5 (10.7) |

| BASDAI Q1 (fatigue) | 6.6 (1.7) | 6.4 (1.5) |

| SF-36 PCS | 33.4 (8.5) | 34.4 (8.5)† |

| EQ-5D-3L utility | 0.53 (0.28) | 0.54 (0.29)† |

| ASQoL | 9.4 (4.5) | 8.9 (4.6) |

| MOS-Sleep-R Index II | 43.1 (9.0) | 44.2 (9.3)† |

| WPAI-axSpA | ||

| % presenteeism % absenteeism % overall work impairment % activity impairment |

48.2 (23.0)‡ 12.2 (25.8)¶ 50.6 (24.2)‡ 55.4 (22.3) |

44.8 (24.4)§ 11.3 (24.7)** 47.5 (25.3)§ 53.4 (23.7)† |

| Prior TNFi exposure, n (%) | 27 (10.6) | 54 (16.3) |

| Concomitant medication use, n (%) | ||

| NSAIDs Oral glucocorticoids csDMARDs |

189 (74.4) 21 (8.3) 61 (24.0) |

266 (80.1) 23 (6.9) 66 (19.9) |

Randomised set. Data pooled by study. WPAI-axSpA item scores are expressed as a percentage, with higher numbers indicating greater impairment and less productivity.

*ULN value for hs-CRP is 5 mg/L.

†n=331.

‡n=170.

§n=223.

¶n=188.

**n=242.

ASDAS, Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Score; ASDAS-HDA, ASDAS high disease activity; ASDAS-ID, ASDAS inactive disease; ASDAS-LDA, ASDAS low disease activity; ASDAS-vHDA, ASDAS very high disease activity; ASQoL, Ankylosing Spondylitis Quality of Life; axSpA, axial spondyloarthritis; BASDAI, Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index; BASFI, Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Functional Index; BMI, body mass index; csDMARD, conventional synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drug; CV, coefficient of variation; EQ-5D-3L, European Quality of Life 5 Dimensions 3 Level Version; FACIT-Fatigue, Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy – Fatigue; HLA-B27, human leukocyte antigen-B27; hs-CRP, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein; MOS-Sleep R, Medical Outcomes Study Sleep scale Revised; n, number; nr-axSpA, non-radiographic axSpA; NSAID, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug; Q, question; r-axSpA, radiographic axSpA; SF-36 PCS, Short Form-36 Physical Component Summary; TNFi, tumour necrosis factor inhibitor; ULN, upper limit of normal; WPAI-axSpA, Work Productivity and Activity in axSpA.

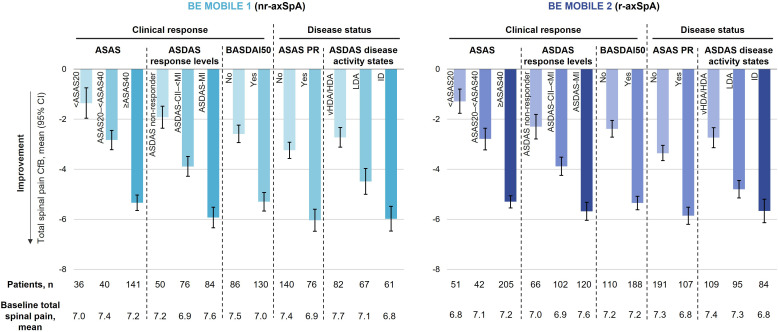

Pain

In patients with nr-axSpA, achievement of more stringent ASAS response levels (ie,<ASAS20, ASAS20–<ASAS40, ≥ASAS40), ASDAS response levels (ie, ASDAS non-responder, ASDAS-CII–<MI, ASDAS-MI) and ASDAS disease activity levels (ie, vHDA/HDA, LDA, ID) at week 52 was associated with sequentially larger mean reductions (ie, improvements) from baseline in total spinal pain: ASAS response (<ASAS20: –1.4, ASAS20–<ASAS40: –2.8, ≥ASAS40: –5.3); ASDAS response levels (ASDAS non-responder: –1.9, ASDAS-CII–<MI: –3.9, ASDAS-MI: –5.9); BASDAI50 (no: –2.6, yes: –5.3); ASAS PR (no: –3.2, yes: –6.0); ASDAS disease activity states (vHDA/HDA: –2.7, LDA: –4.5, ID: –6.0).

Changes from baseline in total spinal pain were of similar amplitude in patients with nr-axSpA and r-axSpA, across all composite clinical efficacy endpoints (figure 1). Associations at week 16 were comparable to those observed at week 52 (online supplemental figure 2).

Figure 1.

Associations between clinical composite efficacy endpoints and total spinal pain at week 52 (OC). Randomised set. Categories are mutually exclusive. Total spinal pain is a component of ASAS, BASDAI and ASDAS response criteria. ASDAS reduction less than 1.1 (ie, change from baseline (CfB) >−1.1) is referred to as ASDAS non-responder, ASDAS reduction greater or equal to 1.1 and less than 2.0 (ie, −2.0> CfB ≤−1.1 or ASDAS clinically important improvement (CII), but not major improvement (MI)) is referred to as ASDAS-CII–<MI and ASDAS reduction greater or equal to 2.0 (ie, ASDAS CfB ≤−2.0) is referred to as ASDAS-MI)). ASAS, Assessment of SpondyloArthritis International Society; ASAS20, ASAS ≥20% improvement; ASAS40, ASAS ≥40% improvement; ASAS PR, ASAS partial remission; ASDAS, Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index; axSpA, axial spondyloarthritis; BASDAI50, ≥50% improvement in Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index; HDA, high disease activity; ID, inactive disease; LDA, low disease activity; n, number; nr-axSpA, non-radiographic axSpA; OC, observed case; r-axSpA, radiographic axSpA; vHDA, very HDA.

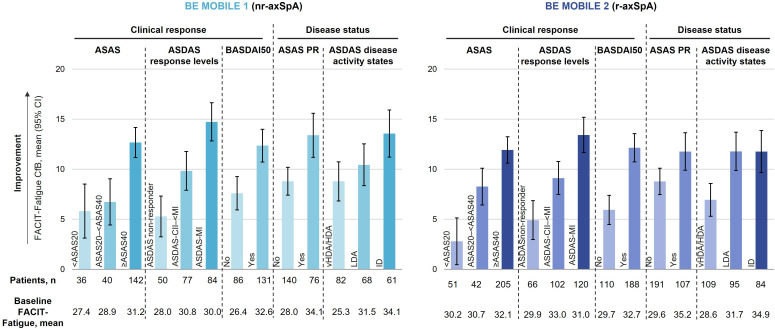

Fatigue

At week 52, achievement of increasingly stringent ASAS and ASDAS response levels was associated with sequentially larger mean increases (ie, improvements) from baseline in FACIT-Fatigue across patients with nr-axSpA (<ASAS20: 5.8, ASAS20–<ASAS40: 6.7, ≥ASAS40: 12.7; ASDAS non-responder: 5.3, ASDAS-CII–<MI: 9.8, ASDAS-MI: 14.7) and r-axSpA (<ASAS20: 2.8, ASAS20–<ASAS40: 8.3, ≥ASAS40: 11.9; ASDAS non-responder: 4.9, ASDAS-CII–<MI: 9.1, ASDAS-MI: 13.4; figure 2). Patients across the full disease spectrum of axSpA who achieved BASDAI50 and ASAS PR also demonstrated larger improvements in FACIT-Fatigue than patients who did not (figure 2). While patients with nr-axSpA who achieved lower ASDAS disease activity levels displayed a clear sequentially greater improvement in FACIT-Fatigue (vHDA/HDA: 8.8, LDA: 10.4, ID: 13.6), this was less apparent for patients with r-axSpA (vHDA/HDA: 6.9, LDA: 11.8, ID: 11.8), where FACIT-Fatigue improvements were comparable in ASDAS LDA and ID achievers, likely due to fewer patients with axSpA achieving ID.

Figure 2.

Associations between clinical composite efficacy endpoints and FACIT-Fatigue at week 52 (OC). Randomised set. Categories are mutually exclusive. ASDAS reduction less than 1.1 (ie, change from baseline (CfB) >−1.1) is referred to as ASDAS non-responder, ASDAS reduction greater or equal to 1.1 and less than 2.0 (ie, −2.0>CfB ≤−1.1 or ASDAS clinically important improvement (CII), but not major improvement (MI)) is referred to as ASDAS-CII–<MI and ASDAS reduction greater or equal to 2.0 (ie, ASDAS CfB ≤−2.0) is referred to as ASDAS-MI). ASAS, Assessment of SpondyloArthritis International Society; ASAS20, ASAS ≥20% improvement; ASAS40, ASAS ≥40% improvement; ASAS PR: ASAS partial remission; ASDAS, Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index; axSpA, axial spondyloarthritis; BASDAI50, ≥50% improvement in Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index; FACIT-Fatigue, Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Fatigue; HDA, high disease activity; ID, inactive disease; LDA, low disease activity; n, number; nr-axSpA, non-radiographic axSpA; OC, observed case; r-axSpA, radiographic axSpA; vHDA, very HDA.

Similarly, patients with nr-axSpA and r-axSpA who reached more stringent composite clinical efficacy endpoints at week 52 demonstrated sequentially larger improvements in BASDAI question 1 (online supplemental figure 3). Associations at week 16 were comparable to those observed at week 52 for both FACIT-Fatigue and BASDAI Q1 (online supplemental figures 4 and 5).

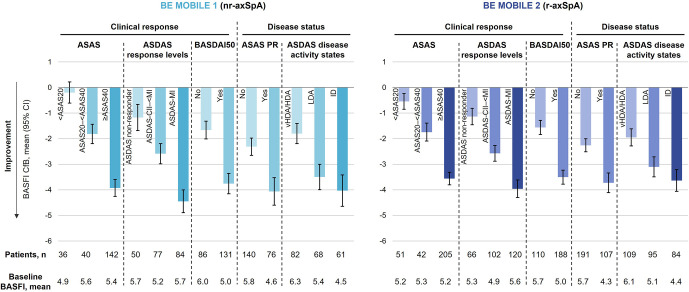

Physical function

Patients achieving increasingly stringent clinical response criteria reported larger reductions (ie, improvements) from baseline in BASFI at week 52. This was comparable between patients with nr-axSpA (<ASAS20: –0.2, ASAS20–<ASAS40: –1.8, ≥ASAS40: –3.9; ASDAS non-responder: –1.2, ASDAS-CII–<MI: –2.6, ASDAS-MI: –4.4; BASDAI50 no: –1.7, yes: –3.8) and r-axSpA (<ASAS20: –0.5, ASAS20–<ASAS40: –1.7, ≥ASAS40: –3.6; ASDAS non-responder: –1.1, ASDAS-CII–<MI: –2.6, ASDAS-MI: –4.0; BASDAI50 no: –1.6, yes: –3.5; figure 3).

Figure 3.

Associations between clinical composite efficacy endpoints and BASFI at week 52 (OC). Randomised set. Categories are mutually exclusive. BASFI is a component of ASAS response criteria. ASDAS reduction less than 1.1 (ie, change from baseline (CfB) >−1.1) is referred to as ASDAS non-responder, ASDAS reduction greater or equal to 1.1 and less than 2.0 (ie, −2.0>CfB ≤−1.1 or ASDAS clinically important improvement (CII), but not major improvement (MI)) is referred to as ASDAS-CII–<MI and ASDAS reduction greater or equal to 2.0 (ie, ASDAS CfB ≤−2.0) is referred to as ASDAS-MI). ASAS, Assessment of SpondyloArthritis International Society; ASAS20, ASAS ≥20% improvement; ASAS40, ASAS ≥40% improvement; ASAS PR, ASAS partial remission; ASDAS, Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index; axSpA, axial spondyloarthritis; BASDAI50, ≥50% improvement in Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index; BASFI, Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Functional Index; HDA, high disease activity; ID, inactive disease; LDA, low disease activity; n, number; nr-axSpA, non-radiographic axSpA; OC, observed case; r-axSpA, radiographic axSpA; vHDA, very HDA.

Achievement of lower disease activity levels was also associated with larger improvements in BASFI in patients with nr-axSpA (ASAS-PR no: –2.3, yes: –4.1; ASDAS vHDA/HDA: –1.8, LDA: –3.5, ID: –4.0) and r-axSpA (ASAS-PR no: –2.3, yes: –3.7; ASDAS vHDA/HDA: –1.9, LDA: –3.1, ID: –3.6). However, CIs for ASDAS LDA and ASDAS ID overlapped, and therefore, the differences between these two disease status levels were less pronounced. Similar associations were observed for BASFI at week 16 (online supplemental figure 6).

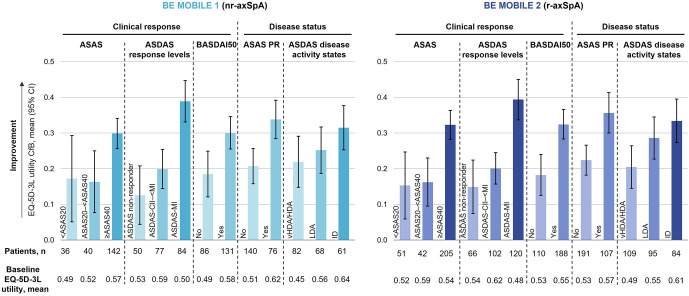

Overall functioning and health

At week 52, achievement of the most stringent ASAS and ASDAS response levels (≥ASAS40 and ASDAS-MI, respectively) were associated with larger mean increases from baseline (ie, improvements) in EQ-5D-3L utility in patients with nr-axSpA (≥ASAS40: 0.30; ASDAS-MI: 0.39). However, there was no clear differentiation between the two lower levels of ASAS and ASDAS response (<ASAS20: 0.17, ASAS20–<ASAS40: 0.16; ASDAS non-responder: 0.13, ASDAS-CII–<MI: 0.20). Patients who achieved the following outcomes also demonstrated larger improvements in EQ-5D-3L utility: BASDAI50 (no: 0.19, yes: 0.30), ASAS PR (no: 0.21, yes: 0.34) and lower levels of ASDAS disease activity (vHDA/HDA: 0.22, LDA: 0.25, ID: 0.32). Similar results were seen for patients with r-axSpA, who also demonstrated mean changes from baseline in EQ-5D-3L utility of a comparable amplitude to patients with nr-axSpA across response criteria for all composite clinical efficacy endpoints (figure 4).

Figure 4.

Associations between clinical composite efficacy endpoints and EQ-5D-3L utility at week 52 (OC). Randomised set. Categories are mutually exclusive. ASDAS reduction less than 1.1 (ie, change from baseline (CfB) >−1.1) is referred to as ASDAS non-responder, ASDAS reduction greater or equal to 1.1 and less than 2.0 (ie, −2.0>CfB ≤−1.1 or ASDAS clinically important improvement (CII), but not major improvement (MI)) is referred to as ASDAS-CII–<MI and ASDAS reduction greater or equal to 2.0 (ie, ASDAS CfB ≤−2.0) is referred to as ASDAS-MI). ASAS, Assessment of SpondyloArthritis International Society; ASAS20, ASAS ≥20% improvement; ASAS40, ASAS ≥40% improvement; ASAS PR, ASAS partial remission; ASDAS, Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index; BASDAI50, ≥50% improvement in Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index; BASFI, Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Functional Index; EQ-5D-3L, European Quality of Life 5 Dimensions 3 Level Version; HDA, high disease activity; ID, inactive disease; LDA, low disease activity; n, number; nr-axSpA, non-radiographic axSpA; OC, observed case; r-axSpA, radiographic axSpA; vHDA, very HDA.

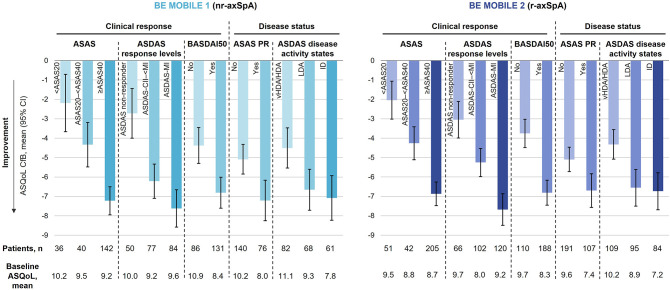

Patients across the axSpA spectrum who achieved increasingly stringent clinical response criteria and lower disease activity levels at week 52 also reported sequentially greater improvements in ASQoL (figure 5). However, no differentiation was seen for ASDAS LDA and ID for both patients with nr-axSpA (ASDAS LDA: –6.7; ASDAS ID: –7.1) and r-axSpA (ASDAS LDA: –6.6; ASDAS ID: –6.7).

Figure 5.

Associations between clinical composite efficacy endpoints and ASQoL at week 52 (OC). Randomised set. Categories are mutually exclusive. ASDAS reduction less than 1.1 (ie, change from baseline (CfB) >−1.1) is referred to as ASDAS non-responder, ASDAS reduction greater or equal to 1.1 and less than 2.0 (ie, −2.0>CfB ≤−1.1 or ASDAS clinically important improvement (CII), but not major improvement (MI)) is referred to as ASDAS-CII–<MI and ASDAS reduction greater or equal to 2.0 (ie, ASDAS CfB ≤−2.0) is referred to as ASDAS-MI). ASAS, Assessment of SpondyloArthritis International Society; ASAS20, ASAS ≥20% improvement; ASAS40, ASAS ≥40% improvement; ASAS PR, ASAS partial remission; ASQoL, Ankylosing Spondylitis Quality of Life; ASDAS, Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index; axSpA, axial spondyloarthritis; BASDAI50, ≥50% improvement in Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index; BASFI, Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Functional Index; HDA, high disease activity; ID, inactive disease; LDA, low disease activity; n, number; nr-axSpA, non-radiographic axSpA; OC, observed case; r-axSpA, radiographic axSpA; vHDA, very HDA.

Associations at week 16 were comparable to those observed at week 52 for EQ-5D-3L utility and ASQoL (online supplemental figures 7 and 8). Achievement of lower disease activity levels was associated with larger improvements in SF-36 PCS at week 52 and week 16 (online supplemental figures 9 and 10).

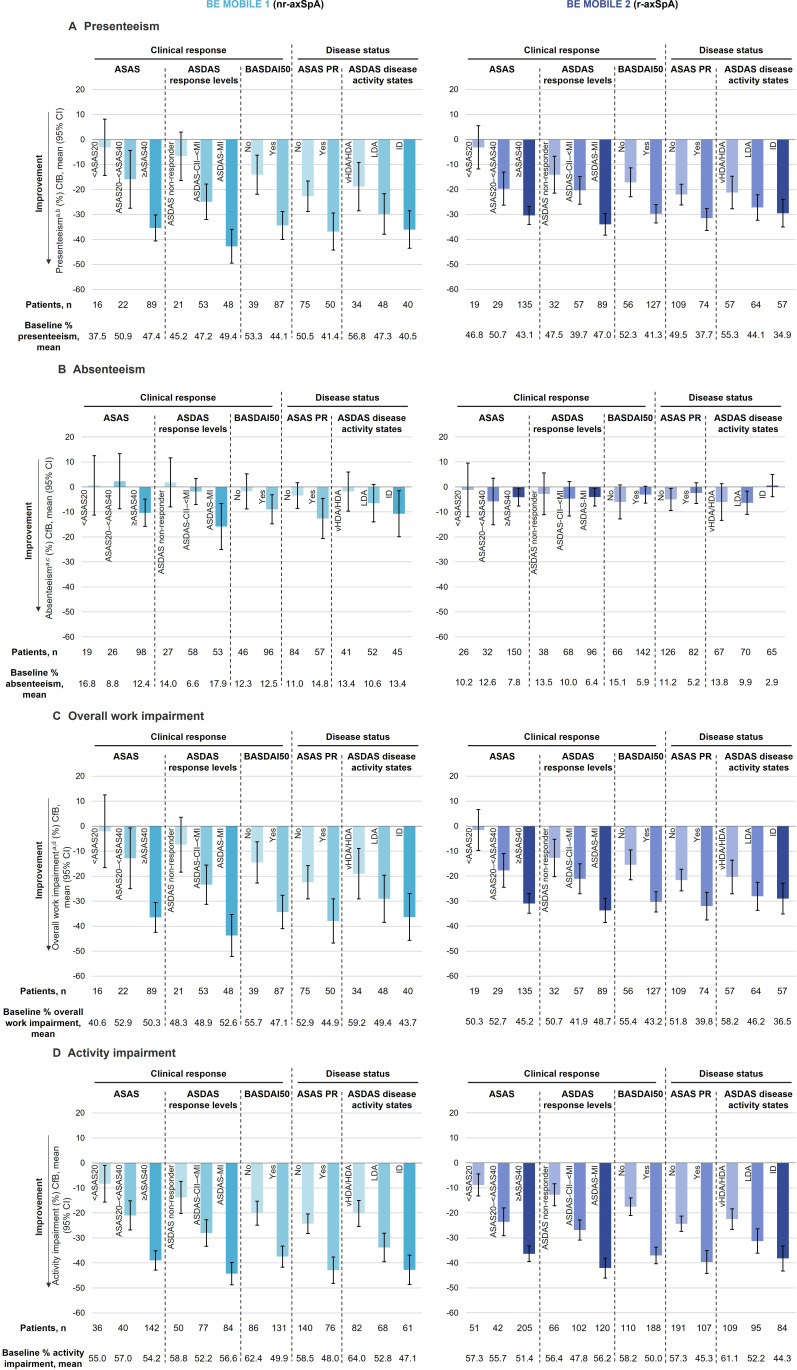

Work and employment

At baseline, 188 patients in BE MOBILE 1 and 243 patients in BE MOBILE 2 were employed. Achievement of increasingly stringent clinical response criteria at week 52 was associated with sequentially larger reductions (ie, improvements) from baseline in WPAI-axSpA presenteeism. This was similar between patients with nr-axSpA (<ASAS20: –3.1, ASAS20–<ASAS40: –15.9, ≥ASAS40: –35.4; ASDAS non-responder: –6.7, ASDAS-CII–<MI: –24.9, ASDAS-MI: –42.7; BASDAI50 no: –14.1, yes: –34.4) and r-axSpA (<ASAS20: –3.2, ASAS20–<ASAS40: –19.7, ≥ASAS40: –30.4; ASDAS non-responder: –14.1, ASDAS-CII–<MI: –20.4, ASDAS-MI: –33.9; BASDAI50 no: –17.1, yes: –29.7; figure 6A). Achievement of lower disease activity levels was, in general, also associated with sequentially larger improvements in presenteeism, across patients with nr-axSpA and r-axSpA. Although, this association was not seen for ASDAS disease activity levels in patients with nr-axSpA (vHDA/HDA: –18.8, LDA: –29.8, ID: –36.0).

Figure 6.

Associations between clinical composite efficacy endpoints and WPAI-axSpA domains at week 52 (OC). Randomised set. Categories are mutually exclusive. ASDAS reduction less than 1.1 (ie, change from baseline (CfB) >−1.1) is referred to as ASDAS non-responder, ASDAS reduction greater or equal to 1.1 and less than 2.0 (ie, −2.0>CfB ≤−1.1 or ASDAS clinically important improvement (CII), but not major improvement (MI)) is referred to as ASDAS-CII–<MI and ASDAS reduction greater or equal to 2.0 (ie, ASDAS CfB ≤−2.0) is referred to as ASDAS-MI). (A) Presenteeism, absenteeism and overall work impairment were assessed only in patients who were employed at baseline; (B) Impairment while at paid work due to axSpA; (C) Work time missed due to axSpA; (D) Overall work impairment is a composite of absenteeism and presenteeism. ASAS, Assessment of SpondyloArthritis International Society; ASAS20, ASAS≥20% improvement; ASAS40, ASAS≥40% improvement; ASAS PR, ASAS partial remission; ASDAS, Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index; axSpA, axial spondyloarthritis; BASDAI50, ≥50% improvement in Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index; HDA, high disease activity; ID, inactive disease; LDA, low disease activity; n, number; nr-axSpA, non-radiographic axSpA; OC, observed case; r-axSpA, radiographic axSpA; vHDA, very HDA; WPAI-axSpA, Work Productivity and Activity in axSpA.

Similarly, patients across the full disease spectrum of axSpA who achieved more stringent composite clinical efficacy endpoints at week 52 demonstrated sequentially larger improvements from baseline in overall work impairment and activity impairment (figure 6C,D).

With the exception of those who achieved lower ASAS response criteria (<ASAS20, ASAS20–<ASAS40), patients with nr-axSpA reaching more stringent clinical response criteria and lower disease activity levels also reported larger reductions (ie, improvements) in absenteeism (<ASAS20: 0.6, ASAS20–<ASAS40: 2.3, ≥ASAS40: –10.3; ASDAS non-responder: 1.8, ASDAS-CII–<MI: –1.8, ASDAS-MI: –15.8; BASDAI50 no: –1.8, yes: –9.0; ASAS PR no: –3.5, yes: –12.6; ASDAS vHDA/HDA: –1.9, LDA: –6.5, ID: –10.7; figure 6B), though changes from baseline were lower in amplitude vs other WPAI-axSpA domains.

In patients with r-axSpA, no clear associations were seen between achievement of increasingly stringent composite clinical efficacy endpoints and CfB in absenteeism (<ASAS20: –1.2, ASAS20–<ASAS40: –5.8, ≥ASAS40: –4.1; ASDAS non-responder: –2.8, ASDAS-CII–<MI: –4.7, ASDAS-MI: –4.1; BASDAI50 no: –6.0, yes: –3.1; ASAS PR no: –5.0, yes: –2.5; ASDAS vHDA/HDA: –6.1, LDA: –6.4, ID: –0.5).

Observations at week 16 were consistent with those at week 52 across the different WPAI-axSpA domains (online supplemental figure 11).

Sleep

Patients with r-axSpA reported sequentially larger improvements (ie, increases) in MOS-Sleep-R Index II with the achievement of increasingly stringent clinical response criteria (<ASAS20: 0.7, ASAS20–<ASAS40: 4.9, ≥ASAS40: 8.2; ASDAS non-responder: 3.0, ASDAS-CII–<MI: 6.5, ASDAS-MI: 8.4; BASDAI50 no: 3.5, yes: 8.2) and disease activity status levels (ASAS PR no: 5.4, yes: 8.4; ASDAS vHDA/HDA: 4.7, LDA: 6.9, ID: 8.4) at week 52. These associations were also seen in patients with nr-axSpA, with the exception of ASAS responses and ASDAS disease activity states, where MOS-Sleep-R Index II improvements were similar in patients achieving<ASAS20 and ASAS20–<ASAS40 (<ASAS20: 3.6, ASAS20–<ASAS40: 3.9, ≥ASAS40: 9.0) and ASDAS vHDA/HDA and LDA (vHDA/HDA: 6.2, LDA: 6.3, ID: 10.0; figure 7).

Figure 7.

Associations between clinical composite efficacy endpoints and MOS-Sleep-R Index II at week 52 (OC). Randomised set. Categories are mutually exclusive. ASDAS reduction less than 1.1 (ie, change from baseline (CfB) >−1.1) is referred to as ASDAS non-responder, ASDAS reduction greater or equal to 1.1 and less than 2.0 (ie, −2.0>CfB ≤−1.1 or ASDAS clinically important improvement (CII), but not major improvement (MI)) is referred to as ASDAS-CII–<MI and ASDAS reduction greater or equal to 2.0 (ie, ASDAS CfB ≤−2.0) is referred to as ASDAS-MI). ASAS, Assessment of SpondyloArthritis International Society; ASAS20, ASAS ≥20% improvement; ASAS40, ASAS ≥40% improvement; ASAS PR, ASAS partial remission; ASDAS, Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index; axSpA, axial spondyloarthritis; BASDAI50, ≥50% improvement in Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index; EQ-5D-3L, European Quality of Life 5 Dimensions 3 Level Version; HDA, high disease activity; ID, inactive disease; LDA, low disease activity; MOS-Sleep-R, Medical Outcomes Study Sleep scale Revised; n, number; nr-axSpA, non-radiographic axSpA; OC, observed case; r-axSpA, radiographic axSpA; vHDA, very HDA.

Associations at week 16 were comparable to those observed at week 52 for MOS-Sleep-R Index II (online supplemental figure 12).

Discussion

Given the severe burden of axSpA on patients’ lives, integration of the patient perspective into clinical practice is critical to achieving the treatment goal of maximising patients’ overall functioning and health, as specified in the ASAS-EULAR recommendations for the management of axSpA.5 21 PRO instruments assessing core axSpA domains are, therefore, valuable for evaluating novel treatments in clinical trials. When used together with traditional efficacy endpoints, these measures provide a holistic view of the efficacy of treatments, not only in overall disease activity, but in core domains of patients’ lives.27

In the phase 3 BE MOBILE 1 and 2 studies, dual inhibition of both IL-17A and IL-17F with bimekizumab resulted in sustained improvements in ASAS core domains of pain, fatigue, physical function and overall functioning and health, work and employment, and sleep through 52 weeks in patients with nr-axSpA and r-axSpA, respectively.18 45 This descriptive post hoc analysis of the BE MOBILE studies expands on these findings by revealing associations between a wide range of clinical composite efficacy endpoints and PRO measures reflecting core axSpA domains. The results of this analysis indicate that, in general, achievement of increasingly stringent clinical response criteria and lower disease activity levels is consistently associated with sequentially greater improvements in PRO measures of core axSpA domains, as well as important domains of work and employment (except absenteeism) and sleep, across the full disease spectrum of axSpA.15 Notably, amplitudes of improvement were similar between patients with nr-axSpA and r-axSpA across almost all measured outcomes.

These findings demonstrate that achieving more stringent clinical composite efficacy outcomes, such as ASAS40, ASAS-PR, ASDAS-MI, BASDAI50, ASDAS LDA and ASDAS ID, generally translates into, and could be a clinical indicator of, larger improvements in disease outcomes that are relevant to patients with axSpA, such as pain, fatigue, physical function and overall functioning and HRQoL. In particular, the core domains of pain, fatigue and physical function have been highlighted by patients as being critically important.46 These data may, therefore, aid in interpreting clinical response criteria by showing the level of improvement, which can be expected for different clinical response levels. Results of the present analysis align with those of recent studies of ixekizumab and adalimumab, which have shown similar associations.22 47

In this analysis, associations were seen for all PROs assessing core axSpA domains except for WPAI-axSpA absenteeism. This is consistent with a previous study which found that patients with nr-axSpA who achieved ASAS40, ASDAS-CII–<MI (defined as a decrease in ASDAS score ≥1.1) and ASDAS-MI (defined as a decrease in ASDAS score ≥2.0) demonstrated substantially larger improvements in all WPAI-axSpA domains except for absenteeism, compared with non-responders.47 48 In BE MOBILE 1 and 2, the lack of association may have been due to the baseline scores being very low for this outcome (ie, a low number of patients were on sick leave or work-disabled at baseline), which limited the ability of the measure to capture improvements. Moreover, the work productivity data obtained from the WPAI-axSpA questionnaire may have been impacted by change in working patterns during the COVID-19 pandemic, which occurred during the BE MOBILE studies.

It should be noted that, as total spinal pain is a component of the ASAS, BASDAI and ASDAS instruments and BASFI is a component of ASAS response criteria, associations between achievement of more stringent clinical responses and improvements in total spinal pain and BASFI were expected and may reflect some circularity. Despite the expected associations, there is still utility in describing the level of improvement observed for the different domains across clinical measures as this understanding can assist in interpretation of complex clinical endpoints such as ASAS40 response. Nevertheless, similar associations were seen between ASDAS and other clinical endpoints where such circularity is not present, such as BASFI responses.

A key strength of this study is the use of multiple composite clinical efficacy endpoints, as well as a variety of PRO instruments measuring several core axSpA domains that contribute to the axSpA patient experience, facilitating a comprehensive analysis of associations between the two. The consistency of results across all analysed core domains supports the robustness of the observed associations and suggests that these data may aid translation of composite efficacy outcomes measured in clinical trials to the impact on core domains experienced by patients with axSpA in clinical practice. Furthermore, these results were comparable across two independent trials in patients across the full disease spectrum of axSpA.

Evaluation of associations at both short-term and long-term time points (week 16 and week 52) is also a strength of this study, compared with the previous associations studies in adalimumab, which only reported data over a short time period,47 and certolizumab, which only examined aspects of work productivity,48 and provides further evidence to suggest the results observed are robust.

As the data used in this study were generated in a clinical trial, they may not be representative of the full axSpA population. Real-world evidence, in addition to association analyses over a longer time, would provide further support to the findings presented here and strengthen their applicability to clinical practice. Similar patterns were observed between patients with r-axSpA and nr-axSpA, although it was not explored here whether similar results were observed in patients with nr-axSpA stratified by MRI and elevated CRP. It should also be noted that the PROs recommended for measurement of the core domains of pain and overall functioning and health, stipulated in the ASAS core outcome set (BASDAI Q2 and ASAS-HI, respectively)15 were not included in this analysis; instead total spinal pain and ASQoL were used.

Conclusions

Patients across the full disease spectrum of axSpA treated with bimekizumab, who achieved increasingly stringent clinical response criteria and lower disease activity levels at week 52, reported sequentially larger improvements in core domains of axSpA including pain, fatigue, physical function and overall functioning and health, as well as in work productivity, and sleep disturbance. Similar amplitudes of improvement for each response level, across all core domains of disease, were observed between patients with nr-axSpA and r-axSpA in each of these key domains.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the patients, the investigators and their teams who took part in these studies. The authors also acknowledge Celia Menckeberg, PhD, UCB Pharma, Breda, The Netherlands for publication coordination and Ellie Fung, BSc, Megan Thomas, BSc, Isabel Raynaud, MBBS and Joseph Smith, PhD, from Costello Medical, UK, for medical writing and editorial assistance based on the authors’ input and direction. These studies were funded by UCB Pharma.

Footnotes

@RheumKay

Contributors: Substantial contributions to study conception and design: VN-C, SR, AD, PJM, MR, CdlL, CF, VT, MFM, UM, JK and MM; substantial contributions to analysis and interpretation of the data: VN-C, SR, AD, PJM, MR, CdlL, CF, VT, MFM, UM, JK and MM; drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content: VN-C, SR, AD, PJM, MR, CdlL, CF, VT, MFM, UM, JK and MM; final approval of the version of the article to be published: VN-C, SR, AD, PJM, MR, CdlL, CF, VT, MFM, UM, JK and MM. VT is the guarantor for this paper.

Funding: This study was funded by UCB Pharma.

Competing interests: VN-C: Speakers’ bureau for AbbVie, Eli Lilly, Fresenius Kabi, Janssen, MSD, Novartis, Pfizer and UCB Pharma; consultant for AbbVie, Eli Lilly, Galapagos, MoonLake, MSD, Novartis, Pfizer and UCB Pharma; grant/research support from AbbVie and Novartis; SR: Grants from AbbVie, Galapagos, MSD, Novartis, Pfizer and UCB Pharma; consultancy from AbbVie, Eli Lilly, Janssen, Novartis, Pfizer, Sanofi and UCB Pharma; AD: Speakers’ bureau for Janssen, Novartis and Pfizer; consultant for AbbVie, BMS, Eli Lilly, Janssen, MoonLake, Novartis, Pfizer, and UCB Pharma; grant/research support from AbbVie, BMS, Celgene, Eli Lilly, MoonLake, Novartis, Pfizer, and UCB Pharma; PJM: Research grants from AbbVie, Acelyrin, Amgen, BMS, Eli Lilly, Gilead, Janssen, Novartis, Pfizer, Sun Pharma, and UCB Pharma; consultancy fees from AbbVie, Acelyrin, Aclaris, Amgen, BMS, Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly, Galapagos, Gilead, GSK, Janssen, Moonlake Pharma, Novartis, Pfizer, Sun Pharma, Takeda, UCB Pharma, and Ventyx; speakers’ bureau for AbbVie, Amgen, Eli Lilly, Janssen, Novartis, Pfizer and UCB Pharma; MR: Speakers’ bureau for AbbVie, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chugai, Eli Lilly, Janssen, Novartis, Pfizer and UCB Pharma; consultant of AbbVie, Eli Lilly, Novartis and UCB Pharma; CdlL: Consultant to UCB Pharma; CF, VT: Employees and shareholders of UCB Pharma; MFM, UM: Employees of UCB Pharma; JK: Consulting fees from Alvotech Swiss AG, Boehringer Ingelheim GmbH, Organon, Ridgeline Discovery, Scipher Medicine, Samsung Bioepis, Sandoz and UCB Pharma; grant/research support paid to institution from Gilead and Novartis; MM: Consultancy fees from AbbVie, BMS, Eli Lilly, Novartis, Pfizer and UCB Pharma; research grants from AbbVie, BMS and UCB Pharma.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as online supplemental information.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

The BE MOBILE 1 and BE MOBILE 2 studies were conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and the International Conference on Harmonisation Guidance for Good Clinical Practice. Ethical approvals were obtained from the relevant institutional review boards at participating sites. All patients provided written informed consent in accordance with local requirements. Participants gave informed consent to participate in the study before taking part.

References

- 1. Navarro-Compán V, Sepriano A, El-Zorkany B, et al. Axial Spondyloarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2021;80:1511–21. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2021-221035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Boel A, Molto A, van der Heijde D, et al. Do patients with axial Spondyloarthritis with radiographic Sacroiliitis fulfil both the modified New York criteria and the ASAS axial Spondyloarthritis criteria? results from eight cohorts. Ann Rheum Dis 2019;78:1545–9. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2019-215707 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Rudwaleit M, Haibel H, Baraliakos X, et al. The early disease stage in axial Spondylarthritis: results from the German Spondyloarthritis inception cohort. Arthritis Rheum 2009;60:717–27. 10.1002/art.24483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Yi E, Ahuja A, Rajput T, et al. Clinical, economic, and humanistic burden associated with delayed diagnosis of axial Spondyloarthritis: A systematic review. Rheumatol Ther 2020;7:65–87. 10.1007/s40744-020-00194-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ramiro S, Nikiphorou E, Sepriano A, et al. ASAS-EULAR recommendations for the management of axial Spondyloarthritis: 2022 update. Ann Rheum Dis 2023;82:19–34. 10.1136/ard-2022-223296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Baeten D, Sieper J, Braun J, et al. Secukinumab, an Interleukin-17A inhibitor, in Ankylosing Spondylitis. N Engl J Med 2015;373:2534–48. 10.1056/NEJMoa1505066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Deodhar A, Poddubnyy D, Pacheco‐Tena C, et al. Efficacy and safety of Ixekizumab in the treatment of radiographic axial Spondyloarthritis: sixteen-week results from a phase III randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial in patients with prior inadequate response to or intolerance of tumor necrosis factor inhibitors . Arthritis & Rheumatology 2019;71:599–611. 10.1002/art.40753 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Deodhar A, Sliwinska-Stanczyk P, Xu H, et al. Tofacitinib for the treatment of Ankylosing Spondylitis: a phase III, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Ann Rheum Dis 2021;80:1004–13. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2020-219601 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Deodhar A, Van den Bosch F, Poddubnyy D, et al. Upadacitinib for the treatment of active non-radiographic axial Spondyloarthritis (SELECT-AXIS 2): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. The Lancet 2022;400:369–79. 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)01212-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Deodhar A, van der Heijde D, Gensler LS, et al. Ixekizumab for patients with non-radiographic axial Spondyloarthritis (COAST-X): a randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2020;395:53–64. 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32971-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Dougados M, Wei JC-C, Landewé R, et al. Efficacy and safety of Ixekizumab through 52 weeks in two phase 3, randomised, controlled clinical trials in patients with active radiographic axial Spondyloarthritis (COAST-V and COAST-W). Ann Rheum Dis 2020;79:176–85. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2019-216118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. van der D, Cheng-Chung Wei J, Dougados M, et al. Ixekizumab, an Interleukin-17A antagonist in the treatment of Ankylosing Spondylitis or radiographic axial Spondyloarthritis in patients previously untreated with biological disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (COAST-V): 16 week results of a phase 3 randomised, double-blind, active-controlled and placebo-controlled trial. The Lancet 2018;392:2441–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. van der Heijde D, Deodhar A, Baraliakos X, et al. Efficacy and safety of Bimekizumab in axial Spondyloarthritis: results of two parallel phase 3 randomised controlled trials. Ann Rheum Dis 2023;82:515–26. 10.1136/ard-2022-223595 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. van der Heijde D, Song I-H, Pangan AL, et al. Efficacy and safety of Upadacitinib in patients with active Ankylosing Spondylitis (SELECT-AXIS 1): a Multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 2/3 trial. The Lancet 2019;394:2108–17. 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32534-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Navarro-Compán V, Boel A, Boonen A, et al. Instrument selection for the ASAS core outcome set for axial Spondyloarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2023;82:763–72. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2022-222747 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ortolan A, Navarro-Compán V, Sepriano A, et al. Which disease activity outcome measure discriminates best in axial Spondyloarthritis? A systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Rheumatology 2020;59:3990–2. 10.1093/rheumatology/keaa527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Strand V, Singh JA. Patient burden of axial Spondyloarthritis. J Clin Rheumatol 2017;23:383–91. 10.1097/RHU.0000000000000589 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Navarro-Compán V, Boel A, Boonen A, et al. The ASAS-OMERACT core domain set for axial Spondyloarthritis. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2021;51:1342–9. 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2021.07.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hirano F, van der Heijde D, van Gaalen FA, et al. Determinants of the patient global assessment of well-being in early axial Spondyloarthritis: 5-year longitudinal data from the DESIR cohort. Rheumatology 2021;60:316–21. 10.1093/rheumatology/keaa353 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Macfarlane GJ, Rotariu O, Jones GT, et al. Determining factors related to poor quality of life in patients with axial Spondyloarthritis: results from the British society for rheumatology Biologics register (BSRBR-AS). Ann Rheum Dis 2020;79:202–8. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2019-216143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Garrido-Cumbrera M, Poddubnyy D, Gossec L, et al. The European map of axial Spondyloarthritis: capturing the patient perspective—an analysis of 2846 patients across 13 countries. Curr Rheumatol Rep 2019;21:19. 10.1007/s11926-019-0819-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Deodhar A, Mease P, Rahman P, et al. Ixekizumab improves patient-reported outcomes in non-radiographic axial Spondyloarthritis: results from the coast-X trial. Rheumatol Ther 2021;8:135–50. 10.1007/s40744-020-00254-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Deodhar AA, Dougados M, Baeten DL, et al. Effect of Secukinumab on patient-reported outcomes in patients with active Ankylosing Spondylitis: A phase III randomized trial (MEASURE 1). Arthritis Rheumatol 2016;68:2901–10. 10.1002/art.39805 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Deodhar AA, Mease PJ, Rahman P, et al. Ixekizumab improves spinal pain, function, fatigue, stiffness, and sleep in radiographic axial Spondyloarthritis: COAST-V/W 52-week results. BMC Rheumatol 2021;5:35. 10.1186/s41927-021-00205-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Navarro-Compán V, Baraliakos X, Magrey M, et al. Effect of Upadacitinib on disease activity, pain, fatigue, function, health-related quality of life and work productivity for biologic refractory Ankylosing Spondylitis. Rheumatol Ther 2023;10:679–91. 10.1007/s40744-023-00536-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Navarro-Compán V, Wei JC-C, Van den Bosch F, et al. Effect of tofacitinib on pain, fatigue, health-related quality of life and work productivity in patients with active Ankylosing Spondylitis: results from a phase III, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. RMD Open 2022;8:e002253. 10.1136/rmdopen-2022-002253 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Revicki DA, Rentz AM, Luo MP, et al. Psychometric characteristics of the short form 36 health survey and functional assessment of chronic illness therapy-fatigue Subscale for patients with Ankylosing Spondylitis. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2011;9:36. 10.1186/1477-7525-9-36 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Smolen JS, Landewé R, Bijlsma J, et al. EULAR recommendations for the management of rheumatoid arthritis with synthetic and biological disease-modifying Antirheumatic drugs: 2016 update. Ann Rheum Dis 2017;76:960–77. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-210715 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Braun J, Kiltz U, Baraliakos X. Emerging therapies for the treatment of Spondyloarthritides with focus on axial Spondyloarthritis. Expert Opinion on Biological Therapy 2023;23:195–206. 10.1080/14712598.2022.2156283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Shah M, Maroof A, Gikas P, et al. Dual Neutralisation of IL-17F and IL-17A with Bimekizumab blocks inflammation-driven Osteogenic differentiation of human Periosteal cells. RMD Open 2020;6:e001306. 10.1136/rmdopen-2020-001306 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Rudwaleit M, van der Heijde D, Landewé R, et al. The development of assessment of Spondyloarthritis International society classification criteria for axial Spondyloarthritis (part II): validation and final selection. Ann Rheum Dis 2009;68:777–83. 10.1136/ard.2009.108233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Lambert RGW, Bakker PAC, van der Heijde D, et al. Defining active Sacroiliitis on MRI for classification of axial Spondyloarthritis: update by the ASAS MRI working group. Ann Rheum Dis 2016;75:1958–63. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2015-208642 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. van der Linden S, Valkenburg HA, Cats A. Evaluation of diagnostic criteria for Ankylosing Spondylitis. A proposal for modification of the New York criteria. Arthritis Rheum 1984;27:361–8. 10.1002/art.1780270401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. van der Heijde D, Lie E, Kvien TK, et al. ASDAS, a highly discriminatory ASAS-endorsed disease activity score in patients with Ankylosing Spondylitis. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases 2009;68:1811–8. 10.1136/ard.2008.100826 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Machado P, Landewe R, Lie E, et al. Ankylosing Spondylitis disease activity score (ASDAS): defining cut-off values for disease activity States and improvement scores. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases 2011;70:47–53. 10.1136/ard.2010.138594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Machado PM, Landewé R, van der Heijde D. Ankylosing Spondylitis disease activity score (ASDAS): 2018 update of the nomenclature for disease activity States. Ann Rheum Dis 2018;77:1539–40:10. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2018-213184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Garrett S, Jenkinson T, Kennedy LG, et al. A new approach to defining disease status in Ankylosing Spondylitis: the bath Ankylosing Spondylitis disease activity index. J Rheumatol 1994;21:2286–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. van Tubergen A, Black PM, Coteur G. Are patient-reported outcome instruments for Ankylosing Spondylitis fit for purpose for the axial Spondyloarthritis patient? A qualitative and Psychometric analysis. Rheumatology 2015;54:1842–51. 10.1093/rheumatology/kev125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Mulhern B, Feng Y, Shah K, et al. Comparing the UK EQ-5D-3L and English EQ-5D-5L value SETS. Pharmacoeconomics 2018;36:699–713. 10.1007/s40273-018-0628-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Dolan P. Modeling valuations for Euroqol health States. Med Care 1997;35:1095–108:11. 10.1097/00005650-199711000-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Doward LC, Spoorenberg A, Cook SA, et al. Development of the Asqol: a quality of life instrument specific to Ankylosing Spondylitis. Ann Rheum Dis 2003;62:20–6. 10.1136/ard.62.1.20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Maruish ME. User’s manual for the SF-36V2 health survey: quality metric incorporated. 2011.

- 43. Reilly MC, Zbrozek AS, Dukes EM. The validity and reproducibility of a work productivity and activity impairment instrument. Pharmacoeconomics 1993;4:353–65. 10.2165/00019053-199304050-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Yarlas A, White MK, St Pierre DG, et al. The development and validation of a revised version of the medical outcomes study sleep scale (MOS sleep-R). J Patient Rep Outcomes 2021;5:40. 10.1186/s41687-021-00311-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Baraliakos X, Deodhar A, van der Heijde D, et al. Bimekizumab treatment in patients with active axial Spondyloarthritis: 52-week efficacy and safety from the randomised parallel phase 3. Ann Rheum Dis 2024;83:199–213. 10.1136/ard-2023-224803 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Boel A, Navarro-Compán V, Boonen A, et al. Domains to be considered for the core outcome set of axial Spondyloarthritis: results from a 3-round Delphi survey. J Rheumatol 2021;48:1810–4. 10.3899/jrheum.210206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. van der Heijde D, Joshi A, Pangan AL, et al. Asas40 and ASDAS clinical responses in the ABILITY-1 clinical trial translate to meaningful improvements in physical function, health-related quality of life and work productivity in patients with non-radiographic axial Spondyloarthritis. Rheumatology 2016;55:80–8. 10.1093/rheumatology/kev267 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Rudwaleit M, Machado PM, Taieb V, et al. Achievement of higher thresholds of clinical responses and lower levels of disease activity is associated with improvements in workplace and household productivity in patients with axial Spondyloarthritis. Ther Adv Musculoskelet Dis 2023;15:1759720X231189079. 10.1177/1759720X231189079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

rmdopen-2023-004040supp001.pdf (7.7MB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as online supplemental information.