Abstract

Background

Individuals with developmental disabilities (DD) experience increased rates of emotional and behavioral crises that necessitate assessment and intervention. Psychiatric disorders can contribute to crises; however, screening measures developed for the general population are inadequate for those with DD. Medical conditions can exacerbate crises and merit evaluation. Screening tools using checklist formats, even when designed for DD, are too limited in depth and scope for crisis assessments. The Sources of Distress survey implements a web-based branching logic format to screen for common psychiatric and medical conditions experienced by individuals with DD by querying caregiver knowledge and observations.

Objective

This paper aims to (1) describe the initial survey development, (2) report on focus group and expert review processes and findings, and (3) present results from the survey’s clinical implementation and evaluation of validity.

Methods

Sources of Distress was reviewed by focus groups and clinical experts; this feedback informed survey revisions. The survey was subsequently implemented in clinical settings to augment providers’ psychiatric and medical history taking. Informal and formal consults followed the completion of Sources of Distress for a subset of individuals. A records review was performed to identify working diagnoses established during these consults.

Results

Focus group members (n=17) expressed positive feedback overall about the survey’s content and provided specific recommendations to add categories and items. The survey was completed for 231 individuals with DD in the clinical setting (n=161, 69.7% men and boys; mean age 17.7, SD 10.3; range 2-65 years). Consults were performed for 149 individuals (n=102, 68.5% men and boys; mean age 18.9, SD 10.9 years), generating working diagnoses to compare survey screening results. Sources of Distress accuracy rates were 91% (95% CI 85%-95%) for posttraumatic stress disorder, 87% (95% CI 81%-92%) for anxiety, 87% (95% CI 81%-92%) for episodic expansive mood and bipolar disorder, 82% (95% CI 75%-87%) for psychotic disorder, 79% (95% CI 71%-85%) for unipolar depression, and 76% (95% CI 69%-82%) for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. While no specific survey items or screening algorithm existed for unspecified mood disorder and disruptive mood dysregulation disorder, these conditions were caregiver-reported and working diagnoses for 11.7% (27/231) and 16.8% (25/149) of individuals, respectively.

Conclusions

Caregivers described Sources of Distress as an acceptable tool for sharing their knowledge and insights about individuals with DD who present in crisis. As a screening tool, this survey demonstrates good accuracy. However, better differentiation among mood disorders is needed, including the addition of items and screening algorithm for unspecified mood disorder and disruptive mood dysregulation disorder. Additional validation efforts are necessary to include a more geographically diverse population and reevaluate mood disorder differentiation. Future study is merited to investigate the survey’s impact on the psychiatric and medical management of distress in individuals with DD.

Keywords: developmental disabilities, disruptive behavior, psychiatric comorbidity, web-based, psychiatric crisis, disability, mental health, behavioral crises, intervention, general population, screening, accuracy, mood disorder, sources of distress, autism, intellectual disability

Introduction

Background

Individuals with developmental disabilities (DD) such as autism and intellectual disability (ID) experience mental health crises more frequently than the general population [1,2]. A broad range of psychiatric and medical conditions can contribute to the agitation, aggression, and self-injury that often characterize these crises [3-10]. Rates of anxiety (20%-77%), depression (10%-20%), expansive mood and bipolar disorder (5%-11%), and psychosis (5%-10%) among individuals with autism exceed those in neurotypical individuals [11-19]. Elevated rates of psychiatric disorders have also been identified in individuals with ID, notably for unspecified psychosis (4.8%), schizophrenia (3.9%), and bipolar disorder (8%) [20-22]. A history of trauma or abuse should also be considered in individuals with DD presenting in crisis [23].

When psychiatric and medical conditions are recognized as factors contributing to a person’s mental health crisis, clear long-term treatment targets emerge. Nevertheless, for those with DD, co-occurring medical and psychiatric conditions are often unrecognized, leaving them vulnerable to experiencing diagnostic overshadowing. Diagnostic overshadowing occurs when disruptive behaviors in individuals with DD are attributed to their disability without consideration of other potential medical or psychiatric conditions that could contribute to their behavioral presentation [24].

Self-, parent-, and caregiver-report mental health questionnaires provide an efficient means of screening for common psychiatric conditions in the neurotypical population. However, for those with DD, self-report questionnaires may be impeded by communication deficits or a limited capacity to reflect on internal experiences. Parent- and caregiver-report questionnaires normed in typically developing children may also provide inadequate mental health screening for those with ID because they often include items that are inapplicable to children with minimal language ability, exclude severe conditions that disproportionately affect children with DD (eg, mania and psychosis), and overlook the individualized manner in which psychiatric symptoms manifest in this population [20,25-27].

The American Psychiatric Association and the National Association for the Dually Diagnosed published the Diagnostic Manual–Intellectual Disability in 2007, and subsequently, in 2016, the second edition (Diagnostic Manual–Intellectual Disability–Second Edition; DM-ID-2) [28,29]. These texts adapt the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders criteria to reflect their presentation in individuals with ID. The Psychopathology Instrument for Mentally Retarded Adults and the Psychiatric Assessment Schedule for Adults with Developmental Disabilities (PAS-ADD) operationalize adapted diagnostic criteria into structured interviews to provide a framework through which to identify psychiatric conditions in this population [30,31]. These interviews are quite lengthy and require training to administer. Even as an abbreviated semistructured interview, the Mini PAS-ADD Clinical Interview takes approximately 45 minutes to complete [32]. Existing parent- and caregiver-report psychiatric screening tools for individuals with ID create a more efficient and practical means of collecting information [33-36]; yet, the checklist format of parent- and caregiver-report questionnaires limits depth and scope, both of which are necessary when evaluating crises in a population with complex medical and mental health needs. In addition, there is a great need for the inclusion of items that query symptoms of common medical conditions (eg, epilepsy, gastrointestinal disorders, and poor dentition) that manifest with agitation and aggression and occur more frequently in individuals with DD [3,37,38].

Sources of Distress is a survey developed for parents and caregivers (hereinafter collectively referred to as caregivers) that uses a web-based branching logic format to screen for mental health and medical conditions among individuals with DD who present in crisis. This tool informs the care of individuals experiencing distress and is intended for use when the severity or persistence of disruptive behavior prompts the consideration of medication intervention. Screening information endorsed by caregivers is organized into relevant psychiatric and medical categories within a report. This report (Multimedia Appendix 1 [39]) is developed for the caregiver and can subsequently facilitate their shared decision-making process with health care providers as specific underlying conditions are evaluated. Sources of Distress aims to minimize diagnostic overshadowing and optimize the ability of the caregiver and the provider to recognize the presence of psychiatric and medical conditions that merit targeted intervention. The web-based branching logic format is adaptive in nature—optimizing caregiver and health care provider convenience and efficiency and minimizing caregiver burden for survey completion [40].

Objectives

This paper aims to (1) describe the initial development of Sources of Distress; (2) report on the findings from focus group evaluations and expert reviews and indicate how this feedback shaped the subsequent version of the survey; and (3) present the results from the evaluation of validity for Sources of Distress after its implementation in the clinical setting. The Methods and Results sections are divided into 3 subsections (apart from the Ethical Considerations section in Methods) corresponding to the development, initial evaluation, and clinical implementation phases of Sources of Distress.

Methods

Ethical Considerations

The University of Utah Institutional Review Board approved focus group activities for Sources of Distress content validation (IRB_00111975). Focus group participants provided informed consent and received compensation for their time in the form of an Amazon gift card worth US $50. The University of Utah Institutional Review Board approved with a waiver of consent for the retrospective records review, data collection, and subsequent deidentified data analysis for individuals for whom Sources of Distress was completed as part of their clinical care (IRB_00170868).

Early Survey Development

Funding for the development of Sources of Distress was provided by the Autism Council of Utah based in Murray, Utah, United States [41]. The development team comprised a triple board physician (pediatrics, general psychiatry, and child and adolescent psychiatry), an educational psychologist, a medical student, and a business consultant grandparent of a child with autism and ID. In the initial development phase, Sources of Distress was built in Qualtrics (Qualtrics International Inc) using a branching logic format to approximate the history-taking component of a DD psychiatric evaluation. This evaluation queries psychiatric symptom clusters, physical complaints, and psychiatric medical history to support the development of a diagnostic impression for which treatment recommendations could be made.

Multiple expert opinion sources were reviewed to identify pertinent screening categories and corresponding items to include in Sources of Distress. The expert sources included published literature, the DM-ID-2, the Mini PAS-ADD Clinical Interview, and the screening interview for the Kiddie Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia–Present and Lifetime (a semistructured psychiatric diagnostic interview for children and adolescents) [28,32,42]. As Sources of Distress is intended for use in the context of distress, the presence of at least 1 manifestation of a behavioral or emotional crisis must be endorsed to initiate survey questions.

Initial Survey Evaluation

Focus Group Evaluation

In 2018 and early 2019, focus group participants were recruited from (1) a university-based outpatient program that provides medical and psychiatric care for individuals with DD across the lifespan and (2) the Autism Council of Utah (a community stakeholder organization for individuals and families affected by autism). Six focus groups were conducted that consisted collectively of parents (6/17, 35%), professional caregivers (6/17, 35%), and adults with both DD and the ability to provide verbal feedback (5/17, 29%). Participants completed Sources of Distress before attending the focus group and reported on specific items, missing items, item wording, and attribution of items to corresponding conditions. Interviews and discussions were transcribed and analyzed following the framework analysis of Ritchie and Spencer [43]. Inductive reasoning and the constant comparative method put forth by Strauss and Corbin [44] were used to compare statements by parents, professional caregivers, and individuals with disability within and across focus groups.

Expert Review Evaluation

Revisions were made to Sources of Distress based on focus group feedback. Experts reviewed the revised survey version, and additional changes were made. The experts included a pediatrician and 2 child psychiatrists, all with national recognition for their clinical and research work in DD.

Clinical Implementation

Overview

Sources of Distress was implemented in various clinical settings to augment the clinical history-taking process—outpatient (primary care, neurology, developmental pediatrics, and psychiatry), emergency department, psychiatric inpatient, and residential care. Caregivers were given a link to the survey when their health care provider identified the need for expert support in managing severe agitation and aggression. All caregivers (231/231, 100%) completed the survey outside of the clinical setting. An informal or formal consult followed survey completion for a subset of individuals. In August 2020, the survey was transitioned from the Qualtrics platform to the REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture; Vanderbilt University) platform to automate the Sources of Distress report generation using the custom template engine [45]. This external REDCap module was developed and has been maintained by the Integrated Research Informatics Services of British Columbia Children’s Hospital Research Institute [46].

Survey Data Collection

Sources of Distress responses were collected from its first use in a clinical setting from February 2019 through June 2022. The following information was obtained: respondent type, individual characteristics, caregiver-reported diagnoses, current medications, distress manifestations, psychiatric symptoms, and medical symptoms, conditions, or concerns. When multiple caregivers reported on the same individual, responses were used from the caregiver closest to where the individual lived (eg, parent for a child living at home and professional caregiver for an individual living in a residential setting). Psychotropic medications were organized within the following mutually exclusive categories: antipsychotics, antidepressants, non-antidepressant anxiolytics, anticonvulsants, lithium, alpha-2 agonists, stimulants, and atomoxetine.

Consults

A medical decision-making support consultation took place after survey completion as either an informal or a formal consult for a subset of individuals. This consult was conducted by a clinical team led by the triple board physician member of the survey’s development team. The consult team used DM-ID-2 criteria as the basis for establishing psychiatric diagnoses. At a minimum (as an informal consult), the consult involved a discussion between a DD clinical expert and the referring provider. This discussion resulted in a collective determination of working diagnoses and treatment plan. A formal consult included the additional components of medical records review, caregiver interview, and direct participant evaluation. Psychiatric diagnoses that were not reported in the survey but discussed by the provider or documented in the medical record were included among preexisting diagnoses.

Working diagnoses were abstracted from formal and informal consult documentation and served as the standard to define true case status.

Mood Disorder Classification

The presence of a mood disorder among preexisting and working diagnoses was classified into mutually exclusive categories such that there was no overlap among individuals across mood disorder categories to allow for direct comparisons across preexisting diagnoses, survey screening status results, and working diagnoses. The following mood disorder classification hierarchy was used from highest to lowest: (1) episodic expansive mood, hypomania, mania, and bipolar disorder, hereafter collectively referred to as bipolar disorder, (2) disruptive mood dysregulation disorder (DMDD) and unspecified mood disorder, and (3) unipolar depression. If an individual had a diagnosis of bipolar disorder, regardless of what other mood disorder diagnosis was reported or identified, their mood disorder classification would be bipolar disorder. An individual was only classified with unipolar depression if (1) they had a depression diagnosis and (2) they had no other mood disorder diagnosis.

Statistical Analyses and Evaluation of Validity

Descriptive statistics and chi-square tests were conducted in SPSS (version 28.0; IBM Corp) with an α of .05 selected to assess statistical significance. Differences between surveys with an accompanying consult and those without were measured. Positive predictive value (PPV), negative predictive value (NPV), and accuracy rates were calculated for (1) preexisting diagnoses and (2) survey screening results with working diagnoses used as the determinant of true case status. We calculated 95% CIs for the binomial distribution of accuracy rates.

Results

Early Survey Development

Table 1 lists the modules and corresponding items initially selected as the categories, characteristics, and symptoms to be queried by Sources of Distress. The initial version of the survey included scoring algorithms to determine positive screen status for the following conditions: anxiety, unipolar depression, bipolar disorder, psychosis, and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).

Table 1.

Description of Sources of Distress and additions in response to focus group feedback.

| Module | Original items | Added in response to feedback |

| Introduction and demographics |

|

|

| Behavior patterns and triggers |

|

|

| Sleep |

|

|

| Anxiety |

|

|

| Depression |

|

|

| Mania |

|

|

| Psychosis |

|

|

| ADHDa |

|

|

| General medical problems |

|

|

| Traumab |

|

|

| Gastrointestinal concernsb |

|

|

| Menstrual concernsb (for female patients only) |

|

|

| Dental concernsb |

|

|

aADHD: attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder.

bModule added in response to focus group feedback.

cN/A: not applicable.

dIUD: intrauterine device.

Initial Survey Evaluation

Focus Group Feedback

During the focus groups, 3 main themes emerged in this analysis.

Theme A: respondents gave overall positive feedback regarding existing content and specific feedback regarding areas where there was room to expand content. Table 1 describes the modules and items added in response to this feedback. Notably, a posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) module was added along with a PTSD scoring algorithm to determine positive screen status.

Theme B: most of the respondents (15/17, 88%) agreed that the symptoms queried matched their understanding of the psychiatric and medical conditions to which they are attributed.

Theme C: all participant groups reported positive acceptability of the branching logic format and time required to complete the measure.

Expert Review

Overall, the expert review supported the Sources of Distress categories and respective items attributed to each condition. One expert recommended adding items that query gender and replacing sex as the basis for pronoun selection within the tool and its report. This expert also suggested that the report include screening results for each psychiatric condition. The former recommendations were implemented when Sources of Distress was transitioned to the REDCap platform. The latter recommendation was deferred until after screening algorithms are validated in a clinical setting.

Clinical Implementation

Sample Characteristics

Surveys (N=264) were completed by parents or guardians (n=200, 75.8%), professional caregivers (n=43, 16.3%), and other caregivers (n=21, 8%) of 231 individuals (n=161, 69.7% men and boys; n=69, 29.9% women and girls; and n=1, 0.4% other; mean age 17.7, SD 10.3; range 2-65 years). Informal (n=62, 41.6%) and formal (n=87, 58.4%) consults were performed for 149 individuals collectively. Table 2 presents sample characteristics, the manifestations of distress, and a comparison between individuals with a consult and those without.

Table 2.

Sample characteristics and distress manifestations.

| Characteristics | With consulta (n=149), n (%) | Without consult (n=82), n (%) | Total (N=231), n (%) | Chi-square (df) | P value | |||

| Genderb | 2.3 (2) | .34 | ||||||

|

|

Man or boy | 102 (68.5) | 59 (72) | 161 (69.7) |

|

|

||

|

|

Woman or girl | 47 (31.5) | 22 (25.5) | 69 (29.9) |

|

|

||

|

|

Otherb | 0 (0) | 1 (1.2) | 1 (0.4) |

|

|

||

| Caregiverc | 7.8 (2) | .02 | ||||||

|

|

Parent or guardian | 108 (72.5) | 71 (86.6) | 179 (77.5) |

|

|

||

|

|

Professional caregiver | 32 (21.5) | 6 (7.3) | 38 (16.5) |

|

|

||

|

|

Other | 9 (6) | 5 (6.1) | 14 (6.1) |

|

|

||

| Age range (y) | 7.4 (2) | .03 | ||||||

|

|

<13 | 46 (30.9) | 38 (46.3) | 84 (36.4) |

|

|

||

|

|

13-22 | 57 (38.3) | 30 (36.6) | 87 (37.7) |

|

|

||

|

|

>22 | 46 (30.9) | 14 (17.1) | 60 (26) |

|

|

||

| Language ability | 0.0 (2) | .99 | ||||||

|

|

Full verbal ability | 76 (51) | 42 (51.2) | 118 (51.1) |

|

|

||

|

|

Limited use of words | 46 (30.9) | 25 (30.5) | 71 (30.7) |

|

|

||

|

|

Nonverbal | 27 (18.1) | 15 (18.3) | 42 (18.2) |

|

|

||

| Manifestation of distress | ||||||||

|

|

Agitation | 130 (87.2) | 70 (85.4) | 200 (86.6) | 0.2 (1) | .69 | ||

|

|

Aggression | 97 (65.1) | 50 (61) | 147 (63.6) | 0.4 (1) | .53 | ||

|

|

Change in sleep | 86 (57.7) | 38 (46.3) | 124 (53.7) | 2.8 (1) | .10 | ||

|

|

Moodiness | 122 (81.9) | 65 (79.3) | 187 (81) | 0.2 (1) | .63 | ||

|

|

Increased fixation | 115 (77.2) | 57 (69.5) | 172 (74.5) | 1.6 (1) | .20 | ||

|

|

Change in eating patterns | 52 (34.9) | 19 (23.2) | 71 (30.7) | 3.4 (1) | .07 | ||

|

|

Change in personality | 99 (66.4) | 59 (72.0) | 158 (68.4) | 0.7 (1) | .39 | ||

|

|

Change in behavior | 96 (64.4) | 45 (54.9) | 141 (61) | 2.0 (1) | .15 | ||

|

|

Self-injurious behavior | 73 (49) | 39 (47.6) | 112 (48.5) | 0.0 (1) | .84 | ||

| Type of disability | ||||||||

|

|

Autism without IDd | 52 (34.9) | 47 (57.3) | 99 (42.9) | 10.9 (1) | <.001 | ||

|

|

ID without autism | 15 (10.1) | 7 (8.5) | 22 (9.5) | 0.1 (1) | .71 | ||

|

|

ID and autism | 74 (49.7) | 18 (22.0) | 92 (39.8) | 17.0 (1) | <.001 | ||

|

|

Genetic syndromee | 17 (11) | 17 (20.7) | 34 (14.7) | 3.7 (1) | .06 | ||

aIncludes informal and formal consults.

bOne participant reported other as gender: no participants reported non-binary as gender.

cWhen multiple caregivers completed Sources of Distress, the report from the caregiver with whom the participant spends the most time was used in this table.

dID: intellectual disability.

eGenetic syndrome includes some individuals who also populate the autism or ID categories.

Preexisting Psychiatric Diagnoses

The presence of at least 1 preexisting psychiatric diagnosis was reported in 65.4% (151/231) of the individuals. Individuals who received a consult compared to those without a consult were more likely to have a caregiver-reported history of psychotic disorder (14/149, 9.4% vs 1/82, 1%; P=.02; Table 3).

Table 3.

Medical conditions, preexisting psychiatric diagnoses, and psychiatric screening results.

| Characteristics | With consulta (n=149), n (%) | Without consult (n=82), n (%) | Total (N=231), n (%) | Chi-square (df) | P value | ||||||||||||

| Medical conditionsb | |||||||||||||||||

|

|

Gastrointestinal concerns | 82 (55) | 37 (45.1) | 119 (51.5) | 2.0 (1) | .15 | |||||||||||

|

|

Dental concerns | 32 (21.5) | 25 (30.5) | 57 (24.7) | 2.3 (1) | .13 | |||||||||||

|

|

Menstrual concernsc | 16 (53.3) | 5 (27.8) | 21 (43.8) | 3.0 (1) | .13 | |||||||||||

|

|

General | ||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

Headache | 26 (17.4) | 8 (9.9) | 34 (14.7) | 2.5 (1) | .11 | ||||||||||

|

|

|

Ear, nose, and throat concerns | 17 (11.4) | 8 (9.9) | 25 (10.8) | 0.2 (1) | .70 | ||||||||||

|

|

|

Seasonal allergies | 34 (22.8) | 13 (15.9) | 47 (20.3) | 1.6 (1) | .21 | ||||||||||

|

|

|

Injury pain | 14 (9.4) | 9 (11) | 23 (10) | 0.2 (1) | .70 | ||||||||||

|

|

|

Thyroid abnormalities | 5 (3.4) | 6 (7.3) | 11 (4.8) | 1.8 (1) | .18 | ||||||||||

|

|

|

Joint pain | 9 (6) | 3 (3.7) | 12 (5.2) | 0.6 (1) | .44 | ||||||||||

|

|

|

Seizures | 29 (19.5) | 16 (19.5) | 45 (19.5) | 0.0 (1) | .99 | ||||||||||

| Seizure History | 40 (26.8) | 18 (22) | 58 (25.1) | 0.7 (1) | .41 | ||||||||||||

| Sleep disturbance | 124 (83.2) | 68 (82.9) | 192 (83.1) | 0.0 (1) | .95 | ||||||||||||

| Preexisting psychiatric diagnoses | |||||||||||||||||

|

|

Any psychiatric condition | 103 (69.1) | 48 (58.5) | 151 (65.4) | 2.6 (1) | .11 | |||||||||||

|

|

Depressiond | 20 (13.4) | 14 (17.1) | 34 (14.7) | 0.6 (1) | .46 | |||||||||||

|

|

Bipolar disorderd | 21 (14.1) | 9 (11) | 30 (13) | 0.5 (1) | .50 | |||||||||||

|

|

Unspecified mood disorder or DMDDd,e | 20 (13.4) | 7 (8.5) | 27 (11.7) | 1.2 (1) | .27 | |||||||||||

|

|

Anxietyf | 62 (41.6) | 31 (37.8) | 93 (40.3) | 0.3 (1) | .57 | |||||||||||

|

|

PTSDg | 11 (7.4) | 4 (4.9) | 15 (6.5) | 0.6 (1) | .46 | |||||||||||

|

|

Psychotic disorder | 14 (9.4) | 1 (1.2) | 15 (6.5) | 5.8 (1) | .02 | |||||||||||

|

|

ADHDh | 50 (33.6) | 26 (31.7) | 76 (32.9) | 0.1 (1) | .78 | |||||||||||

| Psychiatric screening status | |||||||||||||||||

|

|

Any psychiatric condition | 146 (98) | 80 (97.6) | 226 (97.8) | 0.1 (1) | .83 | |||||||||||

|

|

Unipolar depressiond | 61 (40.9) | 30 (36.6) | 91 (39.4) | 0.4 (1) | .52 | |||||||||||

|

|

Episodic expansive mood and bipolar disorderd | 60 (40.3) | 28 (34.1) | 88 (38.1) | 0.8 (1) | .36 | |||||||||||

|

|

Anxiety | 130 (87.2) | 71 (86.6) | 201 (87) | 0.0 (1) | .89 | |||||||||||

|

|

PTSD | 37 (24.8) | 15 (18.3) | 52 (22.5) | 1.3 (1) | .26 | |||||||||||

|

|

Psychosis | 52 (34.9) | 15 (18.3) | 67 (29) | 7.1 (1) | .008 | |||||||||||

|

|

ADHD | 102 (68.5) | 56 (68.3) | 158 (68.4) | 0.0 (1) | .98 | |||||||||||

aIncludes informal and formal consults.

bMedical conditions perceived by the caregiver as contributing to the current presentation of distress.

cAnalysis for menstrual concerns restricted to female patients aged >12.

dUnipolar depression, unspecified mood disorder and disruptive mood dysregulation disorder, and episodic expansive mood and bipolar disorder are mutually exclusive categories.

eDMDD: disruptive mood dysregulation disorder.

fPreexisting diagnosis of obsessive-compulsive disorder is included within the anxiety disorder category.

gPTSD: posttraumatic stress disorder.

hADHD: attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder.

Caregiver-Reported Medical Conditions

Table 3 describes medical conditions reported by caregivers. Caregivers of 73.2% (169/231) of the individuals identified at least 1 physical concern that they perceived as contributing to distress. The most common conditions were gastrointestinal concerns (119/231, 51.5%), menstrual concerns (21/48, 44% of female patients aged >12 y), seasonal allergies (47/231, 20.3%), and seizures (45/231, 19.5%).

Psychiatric Screening Results

Table 3 lists the frequency of positive psychiatric screening results. All but 2% (5/231) of the individuals screened positive for a psychiatric condition, with a mean of 2.8 (SD 1.1; range 0-5) conditions per individual. Of those who were classified as having bipolar disorder, 89% (78/88) screened positive for a recent depressive episode. Positive screen status for psychiatric conditions were similar between those with a consult and those without, except in the case of psychosis (52/149, 34.9% vs 15/82, 18%; P=.008).

Psychotropic Medication Use

Table 4 reports on the frequency of medication use. Most of the individuals (194/231, 84%) were taking psychotropic medication, and the majority were receiving antipsychotics (142/231, 61.5%) and antidepressants (129/231, 55.8%).

Table 4.

Medication use reported in Sources of Distress.

| Medication | With consult (n=149), n (%) | Without consult (n=82), n (%) | Total (N=231), n (%) | Chi-square (df) | P value | |

| Any medication | 146 (98) | 68 (82.9) | 214 (92.6) | 17.6 (1) | <.001 | |

| Any psychotropic medication | 136 (91.3) | 58 (70.7) | 194 (84) | 16.6 (1) | <.001 | |

|

|

Antipsychotic | 102 (68.5) | 40 (48.8) | 142 (61.5) | 8.7 (1) | .003 |

|

|

Antidepressanta | 87 (58.4) | 42 (51.2) | 129 (55.8) | 1.1 (1) | .29 |

|

|

Anxiolyticb | 66 (44.3) | 23 (28.0) | 89 (38.5) | 5.9 (1) | .02 |

|

|

Anticonvulsantc | 45 (30.2) | 12 (14.6) | 57 (24.7) | 6.9 (1) | .009 |

|

|

Lithium | 10 (6.7) | 7 (8.5) | 17 (7.4) | 0.3 (1) | .61 |

|

|

Alpha-2 agonist | 72 (48.3) | 27 (32.9) | 100 (43.3) | 5.1 (1) | .02 |

|

|

Stimulant and atomoxetine | 30 (20.1) | 14 (17.1) | 44 (19) | 0.3 (1) | .57 |

aSelective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, duloxetine, tricyclics, mirtazapine, and trazodone were included exclusively within the antidepressant category.

bBenzodiazapines, buspirone, hydroxyzine, beta-blockers, and prazosin were included exclusively within the anxiolytic category.

cAnticonvulsant medication use in the absence of a reported seizure history.

Working Psychiatric Diagnoses

Of the 149 individuals who received a consult, 148 (99.3%) were diagnosed with at least 1 psychiatric condition with a mean of 2.7 (SD 1.0; range 0-5) diagnoses per individual. The conditions identified were anxiety (129/149, 86.6%), ADHD (84/149, 56.4%), bipolar disorder (67/149, 45%), unipolar depression (33/149, 22.1%), PTSD (35/149, 23.5%), and psychosis (31/149, 20.8%). Furthermore, 25 (16.8%) of the 149 individuals were diagnosed with either unspecified mood disorder or DMDD. Nearly all individuals identified with psychosis (29/31, 94%) had a co-occurring mood disorder diagnosis: bipolar disorder (22/31, 71%), unipolar depression (5/31, 16%), and unspecified mood disorder or DMDD (2/31, 6%).

Evaluation of Validity

Sources of Distress accuracy rates ranged from 76% (95% CI 69%-82%) for ADHD to 91% (95% CI 85%-95%) for PTSD and exceeded those of preexisting diagnoses, except in the case of psychosis, for which the accuracy rates were equivocal (82%, 95% CI 75%-87%; Table 5). The survey demonstrated higher NPVs (81%-98%) than PPVs (51%-78%) for all conditions, with the exceptions of anxiety (53% and 92%, respectively) and episodic expansive mood bipolar disorder (85% and 90%, respectively). Low PPVs were notable for depression (51%) and psychosis (54%).

Table 5.

Association between consult diagnoses after completing Sources of Distress with preexisting psychiatric diagnoses and Sources of Distress screening status (n=149).

| Working diagnosis | Preexisting psychiatric diagnosisa | Sources of Distress screening status | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

Case negative, n | Case positive, n | PPVb (%) | NPVc (%) | Accuracy rated, % (95% CI) | Screen negative, n | Screen positive, n | PPV (%)b | NPV (%)c | Accuracy rated, % (95% CI) | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Unipolar depressione,f | 50 | 82 | 78 (71-84) |

|

|

51 | 98 | 79 (71-85) | ||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

Case negative | 106 | 10 |

|

|

|

86 | 30 |

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||

|

|

Case positive | 23 | 10 |

|

|

|

2 | 31 |

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||

| Episodic expansive mood and bipolar disordere,f | 76 | 60 | 62 (55-70) |

|

|

90 | 85 | 87 (81-92) | ||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

Case negative | 77 | 5 |

|

|

|

76 | 6 |

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||

|

|

Case positive | 51 | 16 |

|

|

|

13 | 54 |

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||

| DMDDg and unspecified mood disordere | 45 | 88 | 82 (75-88) |

|

|

N/Ah | N/A | N/A | ||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

Case negative | 113 | 11 |

|

|

|

N/A | N/A |

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||

|

|

Case positive | 16 | 9 |

|

|

|

N/A | N/A |

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||

| Anxiety disorderi | 97 | 20 | 52 (44-60) |

|

|

92 | 53 | 87 (81-92) | ||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

Case negative | 18 | 2 |

|

|

|

10 | 10 |

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||

|

|

Case positive | 69 | 60 |

|

|

|

9 | 120 |

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||

| Posttraumatic stress disorder | 100 | 83 | 84 (77-89) |

|

|

78 | 95 | 91 (85-95) | ||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

Case negative | 114 | 0 |

|

|

|

106 | 8 |

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||

|

|

Case positive | 24 | 11 |

|

|

|

6 | 29 |

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||

| Psychotic disorderj | 64 | 84 | 82 (75-87) |

|

|

54 | 97 | 82 (75-87) | ||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

Case negative | 113 | 5 |

|

|

|

94 | 24 |

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||

|

|

Case positive | 22 | 9 |

|

|

|

3 | 28 |

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||

| Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder | 84 | 58 | 66 (59-74) |

|

|

74 | 81 | 76 (69-82) | ||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

Case negative | 57 | 8 |

|

|

|

38 | 27 |

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||

|

|

Case positive | 42 | 42 |

|

|

|

9 | 75 |

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||

aPreexisting diagnoses included caregiver-reported diagnoses in Sources of Distress and diagnoses in the medical record before survey completion.

bPPV: positive predictive value =

cNPV: negative predictive value =

dAccuracy rate =

eDepression, episodic expansive mood and bipolar disorder, and disruptive mood dysregulation disorder and unspecified mood disorder are mutually exclusive categories. There is no Sources of Distress screening algorithm for disruptive mood dysregulation disorder or unspecified mood disorder.

fPreexisting and working diagnoses included schizoaffective disorder when hypomanic, manic, or mixed episode was specified.

gDMDD: disruptive mood dysregulation disorder.

hN/A: not applicable.

iPreexisting and working diagnoses of anxiety disorder and obsessive-compulsive disorder are combined to coincide with anxiety disorder screening status.

jPreexisting and working diagnoses were schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, unspecified psychotic disorder, and psychotic features associated with a mood disorder.

Exploration of Mood Disorder Categories

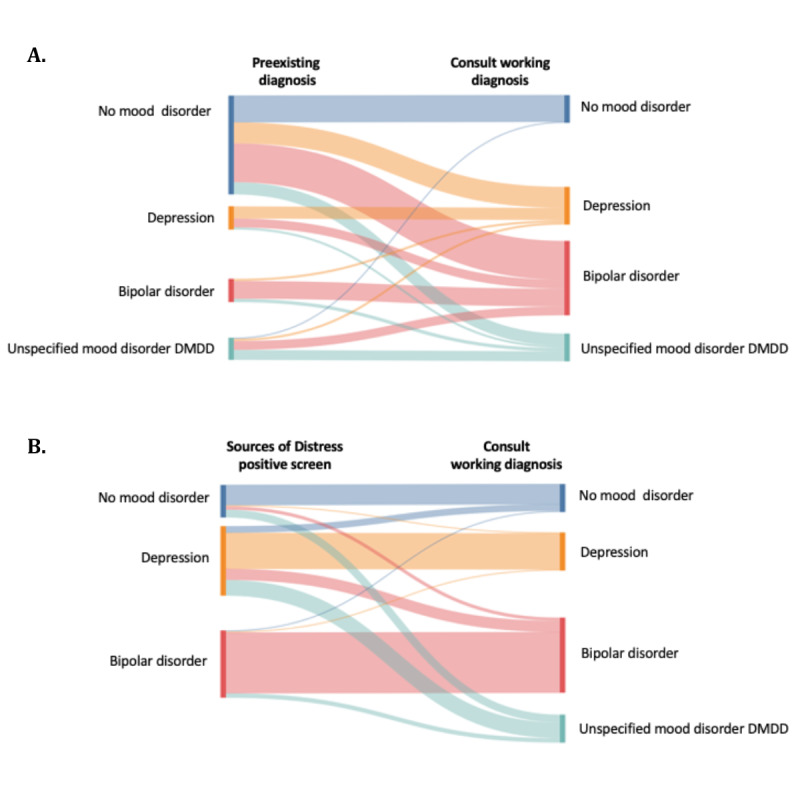

Figure 1 demonstrates the distribution of mood disorder diagnoses among individuals based on (1) preexisting mood disorder diagnosis and (2) Sources of Distress mood disorder screening status. The majority of the individuals (18/25, 72%) who received a working diagnosis of unspecified mood disorder and DMDD screened positive for either unipolar depression or bipolar disorder.

Figure 1.

Comparison of mood disorder categorization between working diagnosis established during consultation and (A) preexisting diagnosis and (B) Sources of Distress positive screen. DMDD: disruptive mood dysregulation disorder.

Discussion

Principal Findings

The focus group feedback indicates that Sources of Distress provides an acceptable means for caregivers to share their knowledge and insights about individuals with DD who present in crisis. As a screening tool, this survey demonstrates good accuracy, although additional work is needed to differentiate among mood disorders. The purpose of this survey is to screen individuals with DD for mental health and common medical concerns in health care settings when they present in crisis. By querying what symptom clusters and physical conditions coincide with their patient’s crisis, providers can direct their evaluation toward specific psychiatric and medical conditions that have established treatment protocols in the general population. This approach aims to reduce diagnostic overshadowing and improve medical decision-making surrounding the management of agitation and aggression in individuals with DD. Focus group participants validated the survey content and provided recommendations that prompted the inclusion of additional modules and items. Despite its length (ie, 15-20 min), participants reported positive acceptability of the survey’s format and duration. This feedback may reflect the convenience of completing a web-based survey at home versus in the medical setting and highlights caregivers’ motivation toward understanding potential factors contributing to the person’s distress. After incorporating caregiver recommendations, Sources of Distress content was also reviewed and supported by clinical and research experts.

Caregivers of most of the individuals (200/231, 86.6%) identified agitation as a presenting concern. The Food and Drug Administration has approved short-term antipsychotic medication for treating irritability in individuals with autism [47]; 61.5% (142/231) of the individuals were taking antipsychotics at the time of presenting in crisis. This frequency exceeds previously reported estimates of antipsychotic use in the population with DD (ie, 10%-48%) and reflects the high acuity and potentially treatment-resistant nature of individuals for whom the survey was completed [48,49]. This study group’s acuity is further supported by the high frequency in which severe mental health conditions were diagnosed in those receiving a consultation (eg, bipolar disorder and psychosis).

Anxiety was the most common condition to screen positive (201/231, 87%) and be established as a working diagnosis (129/149, 86.6%). These rates exceeded measured anxiety prevalence rates in the population with DD (ie, 20%-77%), indicating a higher propensity toward experiencing anxiety among those presenting in crisis [12,15,16]. As a precipitant of distress, prior studies have identified aggression, disruptive behavior, sleep disturbance, and self-injurious behavior as symptoms of anxiety among individuals with DD [4,8,50]. To reduce overclassification among individuals whose autism core features overlap with some anxiety symptoms [51], the Sources of Distress anxiety scoring algorithm was set at a higher threshold than the generalized anxiety disorder criteria described in DM-ID-2. The survey’s low NPV (53%) and high PPV (92%) for anxiety likely reflect this adaption.

Sources of Distress captured well the presence of a mood disturbance; however, the type of mood disorder was not. Study results report a diagnosis frequency of 16.8% (25/149) for unspecified mood disorder and DMDD and indicate the need to add items and a screening algorithm for this condition. The low PPV (51%) for depression primarily resulted from individuals screening positive for depression who were subsequently diagnosed with unspecified mood disorder and DMDD. The DM-ID-2, survey data, and records review will inform new items and algorithm development as well as revisions for the depression screening algorithm. In the interim, the Sources of Distress report will replace the “depression” category label with “depression and unspecified mood disorder” to broaden the range of conditions which it currently captures.

Caregivers of the majority of the individuals (169/231, 73.2%) identified at least 1 physical concern that they perceived as contributing to distress. As agitation may be one of the few visible indicators of pain in an individual with limited expressive language ability and DD, sources of pain should be considered when unexplained agitation is present [3,9,52]. Limited access to medical care by the population with DD further reduces the likelihood that pain and other underlying physical causes of agitation are recognized [53]. Through Sources of Distress, caregivers demonstrated their ability to provide meaningful insight into the potential presence of physical discomfort. This attention was directed most frequently to gastrointestinal, menstrual, dental, and seizure concerns.

Limitations

The generalizability of study results is limited to the geographic, racial, and ethnic diversity of Utah. While survey access requires internet or smartphone access, it has been completed by parents without this access through the assistance of state-sponsored support coordinators and medical assistants. Sources of Distress has a Spanish translation available (Causas de Aflicción); however, these data were not included because its content has not yet been validated by Spanish-speaking caregivers and individuals who are affected. The expert leading the consult team was a member of the survey’s development team, which introduces the inherent bias of evaluating for the presence of mental health conditions through the lens of DM-ID-2 criteria on which survey components were also based. While the DM-ID-2 is well recognized and accepted in the ID provider community, few autism specialty providers are familiar with its use.

Future Directions

Edits and additions to mood disorder items and scoring algorithms are being made to improve differentiation across mood disorders. Branching logic that incorporates the individual’s language ability has recently been added to the psychosis module to improve question clarity and scoring algorithm accuracy. The most updated version of the Sources of Distress can be accessed through the Utah Department of Health and Human Services Autism Systems Development Program webpage [39]. Reevaluation of the survey’s PPVs, NPVs, and accuracy will follow the completion of these changes. Additional studies of this survey are needed to measure its acceptability and validity in clinical settings outside of Utah and by other DD specialty providers. REDCap has also demonstrated capacity to integrate digital mental health screening results into electronic medical records, significantly improving provider adoption of the screening tools [54]. The integration of Sources of Distress into electronic medical records could further enhance its impact on provider efficiency. This survey has already been used during medical evaluations to facilitate the consideration of potential discordance between medications prescribed and conditions present [55]. Prospective studies are merited to determine the survey’s impact on treatment approaches, hospital and emergency department use, and outcomes for individuals with DD who experience crisis.

Conclusions

Individuals with DD presenting in crisis experience high rates of psychiatric disorders and medical concerns that may contribute to, or manifest as, distress. Sources of Distress is a valuable screening tool for psychiatric and medical conditions that commonly accompany treatment-resistant agitation in individuals with DD. When systematically queried, caregivers’ knowledge provides essential information to minimize diagnostic overshadowing and support an evaluation focused on the individual rather than their disability when persistent agitation is assessed in the population with DD.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the individuals with developmental disabilities and their parents and caregivers whose support and participation shaped the development, validation, and piloting of the Sources of Distress. In particular, the authors appreciate the insight and assistance provided by Jaye Olafson. The Autism Council of Utah funded the development of this survey, and access to REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture) is supported through UM1TR004409 NCATS/NIH.

Abbreviations

- ADHD

attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder

- DD

developmental disabilities

- DMDD

disruptive mood dysregulation disorder

- DM-ID-2

Diagnostic Manual–Intellectual Disability–Second Edition

- ID

intellectual disability

- NPV

negative predictive value

- PAS-ADD

Psychiatric Assessment Schedule for Adults with Developmental Disabilities

- PPV

positive predictive value

- PTSD

posttraumatic stress disorder

- REDCap

Research Electronic Data Capture

A sample of the Sources of Distress report.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: The Sources of Distress survey is copyrighted by the University of Utah; DAB, JD, and WW are listed as inventors. DAB consults for BioMarin Pharmaceutical Inc, Encoded Therapeutics, Taysha Gene Therapies, and Synlogic Therapeutics and attended an advisory board meeting for Sanofi. All other authors declare no other conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Durbin A, Balogh R, Lin E, Wilton AS, Selick A, Dobranowski KM, Lunsky Y. Repeat emergency department visits for individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities and psychiatric disorders. Am J Intellect Dev Disabil. 2019 May;124(3):206–19. doi: 10.1352/1944-7558-124.3.206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lunsky Y, Lin E, Balogh R, Klein-Geltink J, Wilton AS, Kurdyak P. Emergency department visits and use of outpatient physician services by adults with developmental disability and psychiatric disorder. Can J Psychiatry. 2012 Oct 01;57(10):601–7. doi: 10.1177/070674371205701004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Antonacci DJ, Manuel C, Davis E. Diagnosis and treatment of aggression in individuals with developmental disabilities. Psychiatr Q. 2008 Sep 23;79(3):225–47. doi: 10.1007/s11126-008-9080-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kim JA, Szatmari P, Bryson SE, Streiner DL, Wilson FJ. The prevalence of anxiety and mood problems among children with Autism and Asperger syndrome. Autism. 2016 Jun 30;4(2):117–32. doi: 10.1177/1362361300004002002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kishore MT, Nizamie SH, Nizamie A. The behavioural profile of psychiatric disorders in persons with intellectual disability. J Intellect Disabil Res. 2005 Nov 06;49(Pt 11):852–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2788.2005.00763.x.JIR763 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lowe K, Allen D, Jones E, Brophy S, Moore K, James W. Challenging behaviours: prevalence and topographies. J Intellect Disabil Res. 2007 Aug 09;51(Pt 8):625–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2788.2006.00948.x.JIR948 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McGuire K, Fung LK, Hagopian L, Vasa RA, Mahajan R, Bernal P, Silberman AE, Wolfe A, Coury DL, Hardan AY, Veenstra-VanderWeele K, Whitaker AH. Irritability and problem behavior in autism spectrum disorder: a practice pathway for pediatric primary care. Pediatrics. 2016 Feb;137 Suppl 2:S136–48. doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-2851L.peds.2015-2851L [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Oliver C, Licence L, Richards C. Self-injurious behaviour in people with intellectual disability and autism spectrum disorder. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2017 Mar;30(2):97–101. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0000000000000313. https://core.ac.uk/reader/185498779?utm_source=linkout . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Regnard C, Reynolds J, Watson B, Matthews D, Gibson L, Clarke C. Understanding distress in people with severe communication difficulties: developing and assessing the Disability Distress Assessment Tool (DisDAT) J Intellect Disabil Res. 2007 Apr 29;51(Pt 4):277–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2788.2006.00875.x.JIR875 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rojahn J, Matson JL, Naglieri JA, Mayville E. Relationships between psychiatric conditions and behavior problems among adults with mental retardation. Am J Ment Retard. 2004 Jan;109(1):21–33. doi: 10.1352/0895-8017(2004)109<21:RBPCAB>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brookman-Frazee L, Stadnick N, Chlebowski C, Baker-Ericzén M, Ganger W. Characterizing psychiatric comorbidity in children with autism spectrum disorder receiving publicly funded mental health services. Autism. 2018 Nov 15;22(8):938–52. doi: 10.1177/1362361317712650. https://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/28914082 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Buck TR, Viskochil J, Farley M, Coon H, McMahon WM, Morgan J, Bilder DA. Psychiatric comorbidity and medication use in adults with autism spectrum disorder. J Autism Dev Disord. 2014 Dec 24;44(12):3063–71. doi: 10.1007/s10803-014-2170-2. https://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/24958436 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eaves LC, Ho HH. Young adult outcome of autism spectrum disorders. J Autism Dev Disord. 2008 Apr 1;38(4):739–47. doi: 10.1007/s10803-007-0441-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Leyfer OT, Folstein SE, Bacalman S, Davis NO, Dinh E, Morgan J, Tager-Flusberg H, Lainhart JE. Comorbid psychiatric disorders in children with autism: interview development and rates of disorders. J Autism Dev Disord. 2006 Oct 15;36(7):849–61. doi: 10.1007/s10803-006-0123-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lai MC, Kassee C, Besney R, Bonato S, Hull L, Mandy W, Szatmari P, Ameis SH. Prevalence of co-occurring mental health diagnoses in the autism population: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Psychiatry. 2019 Oct;6(10):819–29. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(19)30289-5.S2215-0366(19)30289-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lecavalier L, McCracken CE, Aman MG, McDougle CJ, McCracken JT, Tierney E, Smith T, Johnson C, King B, Handen B, Swiezy NB, Eugene Arnold L, Bearss K, Vitiello B, Scahill L. An exploration of concomitant psychiatric disorders in children with autism spectrum disorder. Compr Psychiatry. 2019 Jan;88:57–64. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2018.10.012. http://hdl.handle.net/2318/1690780 .S0010-440X(18)30175-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Morgan CN, Roy M, Chance P. Psychiatric comorbidity and medication use in autism: a community survey. Psychiatr Bull. 2018 Jan 02;27(10):378–81. doi: 10.1192/pb.27.10.378. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Simonoff E, Pickles A, Charman T, Chandler S, Loucas T, Baird G. Psychiatric disorders in children with autism spectrum disorders: prevalence, comorbidity, and associated factors in a population-derived sample. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2008 Aug;47(8):921–9. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e318179964f.S0890-8567(08)60059-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Varcin KJ, Herniman SE, Lin A, Chen Y, Perry Y, Pugh C, Chisholm K, Whitehouse AJ, Wood SJ. Occurrence of psychosis and bipolar disorder in adults with autism: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2022 Mar;134:104543. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2022.104543.S0149-7634(22)00029-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mazza MG, Rossetti A, Crespi G, Clerici M. Prevalence of co-occurring psychiatric disorders in adults and adolescents with intellectual disability: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Appl Res Intellect Disabil. 2020 Mar;33(2):126–38. doi: 10.1111/jar.12654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Platt JM, Keyes KM, McLaughlin KA, Kaufman AS. Intellectual disability and mental disorders in a US population representative sample of adolescents. Psychol Med. 2019 Apr;49(6):952–61. doi: 10.1017/S0033291718001605. https://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/29996960 .S0033291718001605 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Munir KM. The co-occurrence of mental disorders in children and adolescents with intellectual disability/intellectual developmental disorder. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2016 Mar;29(2):95–102. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0000000000000236. https://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/26779862 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Smit MJ, Scheffers M, Emck C, van Busschbach JT, Beek PJ. Clinical characteristics of individuals with intellectual disability who have experienced sexual abuse. An overview of the literature. Res Dev Disabil. 2019 Dec;95:103513. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2019.103513.S0891-4222(19)30180-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jamieson D, Mason J. Investigating the existence of the diagnostic overshadowing bias in Australia. J Ment Health Res Intellect Disabil. 2019 Apr 22;12(1-2):58–70. doi: 10.1080/19315864.2019.1595231. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Joshi G, Biederman J, Petty C, Goldin RL, Furtak SL, Wozniak J. Examining the comorbidity of bipolar disorder and autism spectrum disorders: a large controlled analysis of phenotypic and familial correlates in a referred population of youth with bipolar I disorder with and without autism spectrum disorders. J Clin Psychiatry. 2013 Jun;74(6):578–86. doi: 10.4088/JCP.12m07392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rapoport J, Chavez A, Greenstein D, Addington A, Gogtay N. Autism spectrum disorders and childhood-onset schizophrenia: clinical and biological contributions to a relation revisited. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2009 Jan;48(1):10–8. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e31818b1c63. https://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/19218893 .S0890-8567(08)60165-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bertelli M, Scuticchio D, Ferrandi A, Lassi S, Mango F, Ciavatta C, Porcelli C, Bianco A, Monchieri S. Reliability and validity of the SPAID-G checklist for detecting psychiatric disorders in adults with intellectual disability. Res Dev Disabil. 2012;33(2):382–90. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2011.08.020.S0891-4222(11)00323-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fletcher RJ, Barnhill J, Cooper SA. Diagnostic Manual—Intellectual Disability 2 (DM-ID): A Textbook of Diagnosis of Mental Disorders in Persons with Intellectual Disability. Washington, DC: NADD Press; 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fletcher R, Loschen E, Stavrakiki C, Kingston MF. Diagnostic Manual - Intellectual Disability: A Textbook of Diagnosis of Mental Disorders in Persons With Intellectual Disability. New York, NY: NADD Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Moss S, Patel P, Prosser H, Goldberg D, Simpson N, Rowe S, Lucchino R. Psychiatric morbidity in older people with moderate and severe learning disability. I: development and reliability of the patient interview (PAS-ADD) Br J Psychiatry. 1993 Oct;163:471–80. doi: 10.1192/bjp.163.4.471.S0007125000033869 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Matson JL, Kazdin AE, Senatore V. Psychometric properties of the psychopathology instrument for mentally retarded adults. Appl Res Ment Retard. 1984;5(1):81–9. doi: 10.1016/s0270-3092(84)80021-1.S0270-3092(84)80021-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Devine M, Taggart L, McLornian P. Screening for mental health problems in adults with learning disabilities using the Mini PAS‐ADD Interview. Br J Learn Disabil. 2010 Nov 04;38(4):252–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3156.2009.00597.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Moss S, Prosser H, Costello H, Simpson N, Patel P, Rowe S, Turner S, Hatton C. Reliability and validity of the PAS-ADD Checklist for detecting psychiatric disorders in adults with intellectual disability. J Intellect Disabil Res. 1998 Apr;42 ( Pt 2):173–83. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2788.1998.00116.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sevin JA, Matson JL, Williams D, Kirkpatrick-Sanchez S. Reliability of emotional problems with the diagnostic assessment for the Severely Handicapped (DASH) Br J Clin Psychol. 1995 Feb;34(1):93–4. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8260.1995.tb01442.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Myrbakk E, von Tetzchner S. Screening individuals with intellectual disability for psychiatric disorders: comparison of four measures. Am J Ment Retard. 2008 Jan;113(1):54–70. doi: 10.1352/0895-8017(2008)113[54:SIWIDF]2.0.CO;2.0895-8017-113-1-54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Taylor JL, Hatton C, Dixon L, Douglas C. Screening for psychiatric symptoms: PAS-ADD Checklist norms for adults with intellectual disabilities. J Intellect Disabil Res. 2004 Jan;48(1):37–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2788.2004.00585.x.585 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Marcangelo MJ, Ovsiew F. Psychiatric aspects of epilepsy. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2007 Dec;30(4):781–802. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2007.07.005.S0193-953X(07)00075-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Périsse D, Amiet C, Consoli A, Thorel MV, Gourfinkel-An I, Bodeau N, Guinchat V, Barthélémy C, Cohen D. Risk factors of acute behavioral regression in psychiatrically hospitalized adolescents with autism. J Can Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2010 May;19(2):100–8. https://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/20467546 . [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bilder DA. Sources of distress - Autism Systems Development. Utah Department of Health and Human Services. [2024-03-11]. https://familyhealth.utah.gov/cshcn/asd/# .

- 40.Martin-Key NA, Spadaro B, Funnell E, Barker EJ, Schei TS, Tomasik J, Bahn S. The current state and validity of digital assessment tools for psychiatry: systematic review. JMIR Ment Health. 2022 Mar 30;9(3):e32824. doi: 10.2196/32824. https://mental.jmir.org/2022/3/e32824/ v9i3e32824 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Home page. Autism Council of Utah. [2024-02-11]. https://www.autismcouncilofutah.org/

- 42.Kaufman J, Birmaher B, Brent D, Rao U, Flynn C, Moreci P, Williamson D, Ryan N. Schedule for affective disorders and schizophrenia for school-age children-present and lifetime version (K-SADS-PL): initial reliability and validity data. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1997 Jul;36(7):980–8. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199707000-00021. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0890-8567(09)62555-7 .S0890-8567(09)62555-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ritchie J, Spencer L. Qualitative data analysis for applied policy research. In: Bryman A, Burgess B, editors. Analyzing Qualitative Data. London, UK: Routledge; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Strauss A, Corbin J. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory. 2nd edition. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Harris PA, Taylor R, Minor BL, Elliott V, Fernandez M, O'Neal L, McLeod L, Delacqua G, Delacqua F, Kirby J, Duda SN, REDCap Consortium The REDCap consortium: building an international community of software platform partners. J Biomed Inform. 2019 Jul;95:103208. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2019.103208. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1532-0464(19)30126-1 .S1532-0464(19)30126-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Custom template engine. GitHub. [2024-02-18]. https://github.com/BCCHR-IT/custom-template-engine,

- 47.LeClerc S, Easley D. Pharmacological therapies for autism spectrum disorder: a review. P T. 2015 Jun;40(6):389–97. https://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/26045648 . [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Downs J, Hotopf M, Ford T, Simonoff E, Jackson RG, Shetty H, Stewart R, Hayes RD. Clinical predictors of antipsychotic use in children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorders: a historical open cohort study using electronic health records. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2016 Jun 15;25(6):649–58. doi: 10.1007/s00787-015-0780-7. https://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/26472118 .10.1007/s00787-015-0780-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Esbensen AJ, Greenberg JS, Seltzer MM, Aman MG. A longitudinal investigation of psychotropic and non-psychotropic medication use among adolescents and adults with autism spectrum disorders. J Autism Dev Disord. 2009 Sep 12;39(9):1339–49. doi: 10.1007/s10803-009-0750-3. https://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/19434487 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Shui AM, Katz T, Malow BA, Mazurek MO. Predicting sleep problems in children with autism spectrum disorders. Res Dev Disabil. 2018 Dec;83:270–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2018.10.002.S0891-4222(18)30216-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wood JJ, Gadow KD. Exploring the nature and function of anxiety in youth with autism spectrum disorders. Clin Psychol Sci Pract. 2010 Dec;17(4):281–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2850.2010.01220.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gössler A, Schalamon J, Huber-Zeyringer A, Höllwarth ME. Gastroesophageal reflux and behavior in neurologically impaired children. J Pediatr Surg. 2007 Sep;42(9):1486–90. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2007.04.009.S0022-3468(07)00243-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Matson JL, Rivet TT. Characteristics of challenging behaviours in adults with autistic disorder, PDD-NOS, and intellectual disability. J Intellect Dev Disabil. 2008 Dec;33(4):323–9. doi: 10.1080/13668250802492600. doi: 10.1080/13668250802492600.905608784 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hawley S, Yu J, Bogetic N, Potapova N, Wakefield C, Thompson M, Kloiber S, Hill S, Jankowicz D, Rotenberg D. Digitization of measurement-based care pathways in mental health through REDCap and electronic health record integration: development and usability study. J Med Internet Res. 2021 May 20;23(5):e25656. doi: 10.2196/25656. https://www.jmir.org/2021/5/e25656/ v23i5e25656 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bartel RL, Knight JR, Worsham W, Bilder D. Discordance between psychiatric diagnoses and medication use in children and adults with autism presenting in crisis. Focus (forthcoming) 2024;22 doi: 10.1176/appi.focus.20230027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

A sample of the Sources of Distress report.