Abstract

Background

Musculoskeletal conditions are a leading contributor to disability worldwide. The treatment of these conditions accounts for 7% of health care costs in Germany and is often provided by physiotherapists. Yet, an overview of the cost-effectiveness of treatments for musculoskeletal conditions offered by physiotherapists is missing. This review aims to provide an overview of full economic evaluations of interventions for musculoskeletal conditions offered by physiotherapists.

Methods

We systematically searched for publications in Medline, EconLit, and NHS-EED. Title and abstracts, followed by full texts were screened independently by two authors. We included trial-based full economic evaluations of physiotherapeutic interventions for patients with musculoskeletal conditions and allowed any control group. We extracted participants' information, the setting, the intervention, and details on the economic analyses. We evaluated the quality of the included articles with the Consensus on Health Economic Criteria checklist.

Results

We identified 5141 eligible publications and included 83 articles. The articles were based on 78 clinical trials. They addressed conditions of the spine (n = 39), the upper limb (n = 8), the lower limb (n = 30), and some other conditions (n = 6). The most investigated conditions were low back pain (n = 25) and knee and hip osteoarthritis (n = 16). The articles involved 69 comparisons between physiotherapeutic interventions (in which we defined primary interventions) and 81 comparisons in which only one intervention was offered by a physiotherapist. Physiotherapeutic interventions compared to those provided by other health professionals were cheaper and more effective in 43% (18/42) of the comparisons. Ten percent (4/42) of the interventions were dominated. The overall quality of the articles was high. However, the description of delivered interventions varied widely and often lacked details. This limited fair treatment comparisons.

Conclusions

High-quality evidence was found for physiotherapeutic interventions to be cost-effective, but the result depends on the patient group, intervention, and control arm. Treatments of knee and back conditions were primarily investigated, highlighting a need for physiotherapeutic cost-effectiveness analyses of less often investigated joints and conditions. The documentation of provided interventions needs improvement to enable clinicians and stakeholders to fairly compare interventions and ultimately adopt cost-effective treatments.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s40798-024-00713-9.

Keywords: Economic evaluation, Physiotherapy, Musculoskeletal condition, Orthopedic

Key Points

Several high-quality economic evaluations of physiotherapeutic treatments for the back and knee exist

Economic evaluations of other joints are rare

Physiotherapeutic interventions are often cost-effective over treatments provided by other health professionals

The description of provided interventions in cost-effectiveness analyses needs improvement, to allow fair treatment comparisons

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s40798-024-00713-9.

Background

Rationale

Globally about 1.71 billion people suffer from a musculoskeletal condition [1]. Most adults in rehabilitation within Germany present with this diagnosis [2]. These patients have an increased risk of developing additional chronic diseases and mental health problems, which further increase the patients’ burden [3, 4]. Rehabilitation programs, aiming at reducing these patients' burden and their duration of sick leave, are often planned, and implemented by physiotherapists. Their and other therapeutic services account for 7% of the health expenditures in Germany (2021) and thus cause a financial burden for society [5].

Physiotherapeutic treatments have been used before clinical studies were conducted, but in the last decades, several interventions for specific diseases have been evaluated regarding their clinical effectiveness—although some intervention-disease-combinations remain yet unexplored. In recent years, besides their clinical effectiveness, the costs involved with a treatment have become additionally important to the stakeholders. The combined information supports their decision on whether a treatment should be implemented or de-implemented [6]. Full economic evaluations furnish this information on the anticipated costs along with the expected clinical outcomes of an intervention, enabling comparisons between various disease interventions and by this providing insight into possible cost savings. The costs presented in such analyses consider either healthcare costs alone or both healthcare costs and societal costs [6].

Several studies have already demonstrated that physiotherapists offer treatments worth the money [7, 8]. One review provides an overview of economic evaluations for treatments of neurological conditions offered by physiotherapists [9] and another review evaluates the cost-effectiveness of physical exercise, which is one of the treatment modalities offered by physiotherapists, for various health conditions [10]. However, an overview of existing economic evaluations of different physiotherapeutic treatment modalities for patients with musculoskeletal conditions is missing. Such an overview allows physiotherapists to easily identify relevant publications. Furthermore, it enables policymakers to easily identify relevant studies and researchers to plan future investigations.

Objectives

In this review, we therefore aim to:

provide an overview of existing full economic evaluations of interventions for patients with musculoskeletal conditions offered by physiotherapists.

shed light on the cost-effectiveness of physiotherapeutic interventions for specific musculoskeletal health conditions.

highlight for which health conditions further research is needed.

Methods

Protocol and Registration

A protocol for this review was published and additionally registered at Prospero (CRD42021276050) [11]. We followed our protocol but decided to report the findings of the identified trial and model-based economic evaluations separately. This allows us to fully account for and address the heterogeneous aspects of the two study types. Here we present our findings from the trial-based publications. We report our results following the PRISMA statement.

Eligibility Criteria

We included full economic evaluations of physiotherapeutic interventions for patients with musculoskeletal conditions. To specify our inclusion and exclusion criteria, we used the PICOS acronym (population, intervention, control group, outcome, study type).

Our population of interest suffered from a musculoskeletal condition. If the majority had another primary disease or if the participants had intellectual disabilities, we excluded the publication.

We included publications where physiotherapists provided one of the intervention/control group treatments alone. We excluded publications if the treatment of interest was offered by an interdisciplinary team, non-healthcare professionals, or mostly by a different profession. If the physiotherapeutic treatment of interest was combined with another treatment, this needed to be provided in a comparator group as well. Thus, an isolated incremental effect evaluation of a physiotherapeutic intervention needed to be possible. Economic evaluations of E-intervention were excluded.

We allowed any type of control group including wait-and-see, usual care, placebo, and alternative treatments, and excluded publications where no control group was considered.

Our outcome needed to be the result of a full health economic evaluation, including cost-effectiveness ratios, and cost-utility ratios.

Economic evaluations based on models and clinical trials were included during the screening process. We excluded Delete 'study types like' conference abstracts, reviews, books, and articles with no access and studies without results, e.g. protocols. In this publication, we additionally excluded model-based studies during the full-text screening, to reduce heterogeneity of included studies and allow a fair comparison of the study quality.

Finally, the economic evaluation needed to be published in Danish, English, or German.

Information Sources

We searched for relevant publications in the databases Medline (through PubMed), EconLit, and NHS-EED (can only be searched up to March 2015). The initial search was performed at the end of January 2022 and the final update was performed on the 8th of December 2023.

Search Strategy

We used the three main search terms ‘economic evaluation’, ‘physiotherapy’, and ‘orthopedic’ to develop a search matrix. For each of the main search terms we collected synonyms and combined them with an ‘OR’ in a search. Afterwards, we merged the three synonym searches with two ‘AND’. Utilizing asterisks reduced the number of search terms but allowed identifying relevant articles. Our search string in PubMed consequently was: ((((economic analy*) OR (cost analy*) OR (cost benefit*) OR (cost utility) OR (cost effectiveness) OR (economic evaluation))) AND (((orthopaedic rehabilitation) OR (physical rehabilitation) OR (exercise therap*) OR (conservative therap*) OR (conservative management) OR (conservative treatment) OR (exercise training) OR (physiotherap*))) AND (((muskuloskeletal) OR (chirur*) OR (orthop*) OR (osteoarthritis) OR (back pain)))). "Details on the PubMed search" are also available in Additional file 1: Table S1.

Selection Process

After removing duplicates, we applied a two-step study selection process. In the first step, we screened the title and abstracts for our inclusion and exclusion criteria. In the second step, we evaluated the full texts. Both steps were conducted by two independent reviewers at any time (LB, WF, BK). After each step, the involved authors compared their results and resolved disagreements via discussions or consulting a third reviewer (HHK) if needed.

Data Collection Process

The spreadsheet for data extraction was independently tested on three included publications by two authors (LB, BK). The authors discussed uncertainties, adjusted the labeling in the spreadsheet, and repeated the process. The authors agreed in the second round and LB proceeded with the data extraction. WF became involved in the data extraction process after she compared the data extraction results of three publications with LB, and no disagreement occurred.

Data Items

In total, we extracted the following items per publication: authors, year of publication, sample size, mean age, the proportion of female sex, health condition, location, type of economic analysis, cost perspective, economic effect measure, time horizon, study design, setting, and frequency, intensity, duration as well as the type of intervention, further control intervention, cost-effectiveness results, and finally the author’s conclusion. If the modalities of an intervention were not presented in a publication, but a reference was mentioned, we extracted the information from the cited publication. Further, in articles with several physiotherapeutic intervention or control groups, we ordered the interventions of interest as primary, secondary and so on. We prioritized basic interventions as primary, meaning interventions which could be most easily provided by physiotherapists—without further training.

Critical Appraisal of the Included Publications

We utilized the Consensus on Health Economic Criteria checklist for evaluating the quality of the included articles [12]. This tool consists of 19 questions which can be answered with ‘yes’ or ‘no’ each. Each ‘yes’ indicates good quality, whereas a ‘no’ indicates limited quality.

Two authors (LB and HHK) independently assessed the quality of three articles. After discussing uncertainties LB proceeded with the evaluation. WF got involved in the assessment after she and LB agreed on the quality of three, independently evaluated, articles.

Synthesis of Results

We provide a descriptive overview of the available literature. We categorized the economic evaluations based on the affected body parts. Afterwards, we grouped all cost-effectiveness comparisons, which are partly between two physiotherapeutic interventions, and partly between a physiotherapeutic and another intervention, of the included articles according to the four quadrants of a cost-effectiveness plane (I. more costly, more effective; II. more costly, less effective (dominated); III. less costly, less effective; IV. less costly, more effective (dominant)). The IV. quadrant is always assumed to be cost-effective, and the II. quadrant is always dominated, hence not cost-effective in the performed comparison. However, whether the interventions are cost-effective in the other two quadrants (I. and III.), depends on the stakeholder’s willingness to pay for an extra benefit in a health outcome. As an example, if a health system is not willing to pay the additional costs for the gain in health outcomes in the comparison group, our (primary) interventions in the III. quadrant would be cost-effective. However, if the healthcare system is willing to pay the additional costs to achieve the additional benefit in the health outcome, our (primary) interventions grouped in the I. quadrant would be cost-effective. Thus, to determine if interventions of the I. and III. quadrants are cost-effective, we would need to know the amount of money the healthcare system or society is willing to pay for a one-unit gain in the respected health outcome. However, this is beyond the scope of this review. For comparisons between two physiotherapeutic interventions, we defined one intervention as the primary intervention of interest. These primary physiotherapeutic interventions were more likely offered solely by physiotherapists and required least additional training/courses for the physiotherapists.

Results

Selection of Publications

Our search findings and the study selection process are visualized in the flowchart Fig. 1. In total, we identified 5141 eligible publications of which 83 met our inclusion criteria. A list of the publications excluded during the full-text screening process including an indication of the reason for exclusion is provided in Additional file 2: Table S2.

Fig. 1.

Flow chart of the study selection process

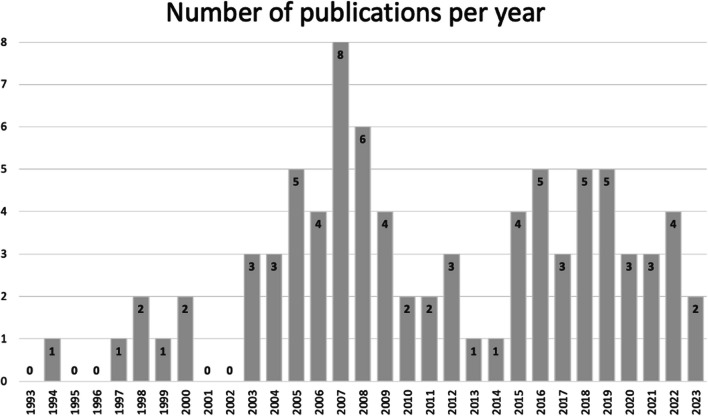

Characteristics of the Economic Evaluations

Table 1 summarizes our included 83 articles which were based on 78 clinical trials [13–95]. Niemistö et al., Barker et al., Skargren et al. as well as Hurley et al. published two articles each building on one trial [17, 18, 51, 52, 72, 81, 82, 96]. Abbott et al. and Pinto et al. utilized data from the MOA RCT [13, 74]. All articles were published between 1994 and 2023 (Fig. 2). The majority of the 78 clinical trials were RCTs (n = 71) and 71 of the articles originated from the Western world. The UK (n = 23) and the Netherlands (n = 22) contributed more than 50% of the articles (Fig. 3). The time horizon of the economic evaluations varied between 5 days and 36 months. In Table 1 the included articles are grouped by their addressed body parts: spine (n = 39), upper limb (n = 8), lower limb (n = 30), and other conditions (n = 6). The most frequently investigated conditions were low back pain (n = 25) and hip and knee osteoarthritis (n = 16). In most included samples the mean age was between 45 and 65 and the distribution of female and male participants was between 40 to 60%. If a sample deviated from this, the mean age and female percentage were added in Table 1.

Table 1.

Overview of the included trial-based economic evaluations

| Study ID | Patients' characteristics | Country | Study design, type of economic analysis | Cost perspective | Effect measure | Time horizon |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spine | ||||||

| Back | ||||||

|

A Barker et al. 2019 [17] B Barker et al. 2020 [18] |

n = 615 Mean age: 72 Female: 86% Osteoporotic vertebral fracture |

UK |

RCT (PROVE-trial) Cost-utility |

Healthcare perspective, Societal perspective |

QALY (EQ-5D) | 12 months |

| Müller et al. 2019 [71] |

n = 2324 patients Back pain |

DE |

Prospective cohort study Cost-effectiveness |

Healthcare perspective, sick leave | Pain intensity (Graded chronic back pain status) | 24 months |

| Søgaard et al. 2008 [84] |

n = 90 lumbar spinal fusion |

DK~ |

RCT Cost-effectiveness |

Societal perspective | Pain- and disability index scales of the low back pain rating scale | 24 months |

| Low back pain | ||||||

| Aboagye et al. 2015 [14] |

n = 159 female: (i1) 72% (i2) 62% (c) 80% LBP |

SE |

RCT Cost-effectiveness |

Societal perspective | QALY (EQ -5D) | 12 months |

| Ankjær-Jensen et al. 1994 [15] |

n = 172 Mean age: 44 LBP (herniated disc) |

DK |

Retrospective cohort study Cost-effectiveness |

Societal perspective | Low back pain rating scale |

(i) 12 months c) 22 months |

| Apeldoorn et al. 2012 [16] |

n = 156 Mean age: (i) 43 (c) 42 LBP (chronic) |

NL |

RCT cost-effectiveness |

Societal perspective | QALY (EQ-5D) | 12 months |

| Bello et al. 2015 [21] |

n = 62 Mean age: (i) 43 (c) 45 LBP (chronic) |

GH |

Feasibility intervention NA |

Healthcare perspective | SF-36, numeric rating scale | 3 months |

| Burton et al. 2004 [26] |

n = 1287 LBP (non-specific) |

UK |

RCT Cost-utility, cost-effectiveness |

Healthcare perspective | QALY (EQ -5D) | 12 months |

| Canaway et al. 2018 [27] |

n = 220 Mean age: 42 LBP |

IL |

Prospective cohort study Cost-effectiveness |

Healthcare perspective | QALY (SF-12) | 12 months |

| Carr et al. 2005 [28] |

n = 237 Mean age: (i) 42 (c) 43 LBP |

UK |

RCT Cost-effectiveness |

Healthcare perspective | RMDQ | 12 months |

| Cherkin et al. 1998 [29] |

n = 321, Mean age: 41 LBP (chronic) [12+ weeks] |

US |

RCT Cost-effectiveness |

Healthcare perspective | Bothersomeness of symptoms, RDS |

Short-term: 3 months Long-term: 12–24 months |

| Critchley et al. 2007 [32] |

n = 150 Mean age: 44 Female: (i1) 71% (i2) 62% (c) 69% LBP (acute) [symptoms < 90 days] |

UK |

RCT Cost-effectiveness |

Healthcare perspective | QALY (EQ-5D) | 18 months |

| Fritz et al. 2008 [38] |

n = 471 Mean age: 41 LBP (acute) [without clinical signs of nerve root, symptoms < 16 days] |

US |

Case–control Cost-effectiveness |

Healthcare perspective | OSW, pain rating | 24 months |

| Fritz et al. 2017 [39] |

n = 220 Mean age: (i) 38 (c) 37 LBP [symptoms for 6 weeks to 6 months] |

US |

RCT Cost-effectiveness |

Societal perspective | QALY (EQ-5D) | 12 months |

| Hahne et al. 2017 [43] |

n = 300 Mean age: (i) 43 (c) 46 LBP (chronic) [symptoms 6+ weeks] |

AU |

RCT Cost-utility |

Healthcare perspective | QALY (EQ-5D) | 12 months |

| Herman et al. 2008 [45] |

n = 75 LBP [symptoms for 4+ weeks] |

US |

RCT Cost-effectiveness |

Main: societal perspective; additional: employer, participant | QALY (SF-6D) | 6 months |

| Hlobil et al. 2007 [46] |

n = 134 [sick-listed worker] mean age: (i) 39 (c) 37 LBP (chronic) |

NL |

RCT Cost–benefit |

Societal perspective | Lost productivity days | 36 months |

| Hurley et al. 2015 [50] |

n = 246 LBP [symptoms 3+ months] |

IE |

RCT Cost-utility |

Healthcare perspective | QALY (EQ-5D) | 12 months |

| Johnson et al. 2007 [55] |

n = 234 LBP |

UK |

RCT Cost-utility |

Healthcare perspective | QALY (EQ-5D) | 12 months |

| Karjalainen et al. 2003 [57] |

n = 164 mean age: (i1) 44 (i2) 44 (c) 43 [25–61 y.] LBP |

FI |

RCT Cost–benefit |

Healthcare perspective | Bothersomeness and frequency of pain, daily symptoms, generic health-related quality of life, intensity of pain, ODI, sick leave, | 12 months |

| Kim et al. 2020 [59] |

n = 56 [BMI 17–30] Mean age: (i) 48 (c) 39 Female: (i) 25% (c) 29% LBP (chronic) |

KR |

RCT Cost-effectiveness |

Healthcare perspective | Functional rating index, Multidimensional Personality Questionnaire, VAS | 3 weeks |

|

A Niemistö et al. 2003 [72] B Niemistö et al. 2005 [73] |

n = 204 Mean age: (i) 37 (c) 37 [24–46] LBP (subacute and chronic) [symptoms 6+ weeks] |

FI |

RCT Cost-effectiveness |

Societal perspective |

A VAS B ODI, VAS |

A 12 months B 24 months |

| Rivero-Arias et al. 2006 [77] |

n = 286 mean age: (i) 42 (c) 40 LBP (chronic) [symptoms 3+ months] |

UK |

RCT Cost-utility |

Healthcare perspective, societal perspective | QALY (EQ-5D) | 12 months |

| Smeets et al. 2009 [83] |

n = 160 Mean age: (i1) 43 (i2) 42 (c) 43 LBP |

NL |

RCT Cost-effectiveness, cost-utility |

Societal perspective | RMDQ, QALY (EQ-5D) | 12 months |

| Suni et al. 2018 [87] |

n = 219 [health professionals] Female: 100% LBP (chronic) |

FI |

RCT Cost-effectiveness |

Healthcare perspective, sick leave | QALY (SF-6D) | 12 months |

| van der Roer et al. 2008 [93] |

n = 114 [have a health insurance with company AGIS] LBP [symptoms < 12 weeks] |

NL |

RCT Cost-effectiveness |

Societal perspective | General perceived effect (6-point-scale), pain-rating-scale, EQ-5D, RMDQ | 12 months |

| Whitehurst et al. 2007 [95] |

n = 299 LBP (chronic) |

UK |

RCT cost-effectiveness, cost-utility |

Healthcare perspective | RMDQ, QALY (EQ-5D) | 12 months |

| Neck | ||||||

| Bosmans et al. 2011 [24] |

n = 146 Neck pain (subacute) |

NL |

RCT Cost-effectiveness, cost-utility |

Societal perspective | Patient perceived recovery, QALY (SF-6D) | 12 months |

| Korthals-de Bos et al. 2003 [62] |

n = 183 Neck pain |

NL~ |

RCT Cost-effectiveness, cost-utility |

Societal perspective | EQ, functional disability, pain intensity, patient perceived recovery | 12 months |

| Leininger et al. 2016 [63] |

n = 241 Mean age: 73 Neck pain (chronic) [symptoms 3+ months] |

US |

RCT Cost-effectiveness |

Societal perspective | QALY (SF-6D) | 12 months |

| Lewis et al. 2007 [64] |

n = 350 Female: 63% (in total) Neck disorders (non-specific) |

UK |

RCT Cost-effectiveness, cost-utility |

Healthcare perspective, societal perspective | Northwick Park Questionnaire, QALY (EQ-5D) | 6 months |

| Manca et al. 2006 [68] |

n = 268 Female: (i) 62% (c) 66% Neck pain [musculoskeletal origin, symptoms 2+ weeks] |

UK |

RCT Cost-effectiveness |

Healthcare perspective | QALY (EQ-5D) |

3 months, 12 months |

| Van Dongen et al. 2016 [94] |

n = 181 Female: (i) 62% (c) 62% neck pain (subacute and chronic) |

NL |

RCT cost-effectiveness, cost-utility |

Societal perspective | Neck Disability Index—Dutch Version, patient's perceived recovery | 12 months |

| Others/mixed | ||||||

| Denninger et al. 2018 [34] |

n = 447 Female: 72% Back pain or neck pain |

US |

Retrospective cohort Cost-effectiveness |

Healthcare perspective | EQ-5D, NPRS, Oswestry Disability Index/Neck Disability Index, Patient Health Questionnaire-4 | 24 months |

| Manca et al. 2007 [67] |

n = 315 Back pain or neck pain [non-systematic origin, symptoms 2+ weeks] |

UK |

RCT Cost-effectiveness |

Healthcare perspective | QALY (EQ-5D) | 12 months |

|

A Skargren et al. 1997 [82] B Skargren et al. 1998 [81] |

n = 323 Mean age: (i) 41 c) 41 back or neck pain |

SE |

RCT Cost–benefit |

Healthcare perspective | General Health (scale), ODS, VAS |

A 6 months B 12 months |

| Upper limb | ||||||

| Bergman et al. 2010 [23] |

n = 142 Shoulder complaints |

NL |

RCT Cost-effectiveness |

Societal perspective | Patient perceived recovery | 6 months |

| Commbes et al. 2016 [30] |

n = 154 Female: (i1) 36 (i2) 39 (c1) 38 (c2) 38 epicondylitis lateralis [> 6 weeks duration] |

AU |

RCT Cost-utility |

Societal perspective | QALY (EQ-5D) | 12 months |

| Fernandez-de-Las-penjas et al. 2019 [37] |

n = 120 Female: 100% Carpal tunnel syndrom |

ES |

RCT Cost-effectiveness |

Societal perspective | QALY (EQ-5D) | 12 months |

| Geraets et al. 2006 [41] |

n = 176 Shoulder complaints (chronic) |

NL |

RCT Cost–benefit |

Societal perspective | EQ-5D, main complaints, Shoulder Disability Questionnaire | 12 months |

| Hopewell et al. 2021 [48] |

n = 708 Rotator cuff disease |

UK |

RCT Cost-utility |

Healthcare perspective | QALY (EQ-5D) | 12 months |

| James et al. 2005 [53] |

n = 207 Shoulder pain [new episode] |

UK |

RCT Cost-consequences |

Healthcare perspective | Disability score, EQ-5D | 6 months |

| Korthals-de Bos et al. 2004 [61] |

n = 183 Epicondylitis lateralis |

NL |

RCT Cost-effectiveness, cost-utility |

Societal perspective |

Cost effectiveness: general improvement, pain during the day, PFFQ cost-utility: EQ |

12 months |

| Struijs et al. 2006 [86] |

n = 180 Epicondylitis lateralis [symptoms 6+ weeks] |

NL |

RCT Cost-effectiveness, cost-utility |

Societal perspective | EQ, pain-free function questionnaire, pain most serious complaint, severity of complaint, success rate | 12 months |

| Lower limb | ||||||

| Hip | ||||||

| Fusco et al. 2019 [40] |

n = 80 Female: 0% Hip replacement |

UK |

RCT Cost-effectiveness, cost-utility |

Healthcare perspective | QALY (EQ-5D) | 12 months |

| Griffin et al. 2022 [42] |

n = 358 Mean age: (i) 35 (c) 35 Female: (i) 42% (c) 36% femoroacetabular impingement syndrome |

UK |

RCT (UK FASHioN RCT) Cost-effectiveness |

Healthcare perspective, societal perspective | QALY (EQ-5D) | 12 months |

| Juhakoski et al. 2011 [56] |

n = 118 Mean age: (i) 67 (c) 66 Female: (i) 68% (c) 72% Hip osteoarthritis |

FI |

RCT Cost-effectiveness |

Healthcare perspective | SF-36, WOMAC | 24 months |

| Tan et al. 2016 [88] |

n = 203 Mean age: (i) 65 (c) 67 Female: (i) 62% (c) 55% Hip osteoarthritis |

NL |

RCT Cost-utility |

Healthcare perspective, societal perspective | QALY (EQ-5D) | 12 months |

| Knee | ||||||

| Barton et al. 2009 [20] |

n = 389 Female: 66% (in total) Knee pain [BMI > = 28; age = 45+] |

UK |

RCT Cost-effectiveness |

Healthcare perspective | QALY (EQ-5D) | 24 months |

| Bennell et al. 2016 [22] |

n = 222 [50+] Knee osteoarthritis |

AU |

RCT Cost-effectiveness |

Healthcare perspective | QALY (EQ-5D) | 12 months |

| Eggerding et al. 2021 [35] |

n = 167 Mean age: (i) 31 (c) 31 ACL tear [recent ACL tear, max. 2 month ago] |

NL+ |

RCT Cost-utility |

Healthcare perspective, Societal perspective |

QALY (EQ-5D) | 24 months |

| Ho-Henriksson et al. 2022 [47] |

n = 69 Female: (i) 60% (c) 68% Knee osteoarthritis |

SE |

RCT Cost-effectiveness |

Health care perspective, societal perspective | QALY (EQ-5D) | 12 months |

| Huang et al. 2012 [49] |

n = 243 Mean age: (i) 70 (c) 71 Female: (i) 70% (c) 74% Total knee replacement [unilateral TKA, due to OA] |

TW |

RCT Cost-effectiveness |

Healthcare perspective | Knee ROM, Length of stay, VAS | 5 days |

|

A Hurley et al. 2007 [52] B Hurley et al. 2012 [51] |

n = 418 Mean age: (i1) 66 (i2) 68 (c) 67 [50+] female: (i1) 25% (i2) 22% (c) 23% Knee pain (chronic) [symptoms 6+ months] |

UK |

A RCT (ESCAPE-Knee-Study) Cost-effectiveness, cost-utility B RCT (ESCAPE-Knee-Study) Cost-effectiveness |

Healthcare perspective, social care payer perspective |

A WOMAC, QALY (EQ-5D) B WOMAC |

A 6 months B 30 months |

| Jessep et al. 2009 [54] |

n = 64 Mean age: (i) 66 (c) 67 [> 50] Female: (i) 63% (c) 76% Knee pain (chronic) |

UK |

RCT Cost–benefit |

Healthcare perspective | QALY (EQ-5D) | 12 months |

| Kigozi et al. 2018 [58] |

n = 514 Knee osteoarthritis |

UK |

RCT (BEEP-trial) Cost-effectiveness, cost-utility |

Healthcare perspective | QALY (EQ-5D) | 18 months |

| Knoop et al. 2023 [60] |

n = 328 Mean age: (i) 66 (c) 64 [40–85] Female: (i) 63% (c) 64% Knee osteoarthritis |

NL |

RCT Cost-utility |

Societal perspective | QALY (EQ-5D) | 12 months |

| McCarthy et al. 2004 [69] |

n = 214 Knee osteoarthritis |

UK |

RCT (GRASP-RCT) cost-effectiveness |

Healthcare perspective | QALY (EQ-5D) | 12 months |

| Mitchell et al. 2005 [70] |

n = 114 Mean age: (i) 70 (c) 71 Total knee replacement |

UK |

RCT Cost-effectiveness |

Healthcare perspective | SF-36, WOMAC | 15 months |

| Pryymachenko et al. 2021 [75] |

n = 75 Female: (i1) 63% (i2) 67% (i3) 63% (c) 58% Knee osteoarthritis |

NZ |

RCT (MOA2-Trial) Cost-effectiveness |

Healthcare perspective, societal perspective | QALY (EQ-5D) | 24 months |

| Rhon et al. 2022 [76] |

n = 156 Female: (i) 37% (c) 38% Knee osteoarthritis |

US |

RCT Cost-effectiveness |

Healthcare perspective | QALY (EQ-5D) | 12 months |

| Sevick et al. 2000 (ex) [78] |

n = 439 Mean age: (i1) 69 (i2) 68 (c) 69 [60+] Female: (i1) 69% (i2) 73% (c) 69% Knee osteoarthritis |

US |

RCT Cost-effectiveness |

Healthcare perspective | Car task, lifting and carrying task, Self-reported disability score, stair climb, 6-min walking distance | 18 months |

| Sevick et al. 2009 [80] |

n = 316 Mean age: (i1) 68 (i2) 69 (i3) 69 (c) 69 Female: (i1) 72% (i2) 74% (i3) 74% (c) 68% Knee osteoarthritis |

US~ |

RCT (ADAPT-trial) Cost-effectiveness |

Payer perspective | Stair climb, weight, WOMAC function, WOMAC pain, WOMAC stiffness, 6-min walk | 18 months |

| Stan et al. 2015 [85] |

n = 90 Age mean: (i) 67 (c1) 64 (c2) 65 [60+] Female: 70% (in total) Knee osteoarthritis [varus deformity, Ahlback score 3, 4 or 5] |

RO |

Controlled trial Cost-effectiveness |

Payer perspective | QALY (EQ-5D) | Uncertain |

| Tan et al. 2010 [89] |

n = 131 Mean age: (i) 25 (c) 23 Female: (i) 65% (c) 64% Patellofemoral pain syndrome |

NL |

RCT Cost-utility |

Healthcare perspective, societal perspective | QALY (EQ-5D) | 12 months |

| van de Graaf et al. 2020 [90] |

n = 319 Meniscal tear [non-obstructive] |

NL |

RCT Cost-effectiveness |

Societal perspective | International Knee Documentation Committee, QALY (EQ-5D) | 24 months |

| van der Graaff et al. 2023 [92] |

n = 99 Mean age: (i) 36 (c) 34 [18–45] Female: (i) 26% (c) 23% meniscal tear (traumatic) |

NL |

RCT Cost-utility |

Healthcare perspective, societal perspective | QALY (EQ-5D) | 24 months |

| Others/mixed | ||||||

|

A Abbott et al. 2019 [13] B Pinto et al. 2013 [74] |

n = 206 Mean age: (i1) 67 (i2) 67 (i3) 66 (c) 66 Female: (i1) 32% (i2) 28% (i3) 29% (c) 25% Hip osteoarthritis, knee osteoarthritis |

NZ |

A RCT (MOA-RCT) Cost-effectiveness B RCT (MOA-RCT) Cost-effectiveness, cost-utility |

A Societal perspective B Healthcare perspective, societal perspective |

A QALY (SF-6D) B OMERACT-OARSI responder, QALY (SF-12v2), WOMAC |

A 24 months B 12 months |

| Bulthuis et al. 2008 [25] |

n = 85 Mean age: (i) 69 (c) 69 Female: (i) 42% (c) 28% Hip osteoarthritis, knee osteoarthritis |

NL |

RCT (DAPPER-study) Cost-utility, cost-effectiveness |

Societal perspective | Functional ability, MACTAR and EPMROM | 6 months |

| Coupé et al.‚ 2007 [31] |

n = 200 Female: (i) 75% (c) 79% Hip osteoarthritis, knee osteoarthritis |

NL |

RCT Cost-effectiveness |

Societal perspective | QALY (EQ-5D) | 15 months |

| Fernandes et al. 2017 [97] |

n = 165 Mean age: (i) 68 (c) 67 Total hip replacement, total knee replacement |

DK |

RCT Cost-utility |

Healthcare perspective | HOOS, KOOS, QALY (EQ-5D) | 12 months |

| Lin et al. 2008 [66] |

n = 94 Mean age: (i) 43 (c) 41 Female: (i) 26% (c) 17% Ankle fracture [treated with cast immobilization, with or without surgery before] |

AU |

RCT Cost-effectiveness |

Healthcare perspective, patient perspective | Assessment of Quality of Life, Lower Extremity Functional Scale | 5,5 months |

| Other conditions | ||||||

| Barnhoorn et al. 2018 [19] |

n = 56 Mean age: 44 [18–80] Complex regional pain syndrome type 1 |

NL |

RCT Cost-effectiveness |

Healthcare perspective, travel costs | QALY (EQ-5D) | 9 months |

| Daker-White et al. 1999 [33] |

n = 481 Musculoskeletal problems |

UK |

RCT Cost-effectiveness |

Healthcare perspective, patient perspective | Disease Repercussions Profile, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, Pain—Visual Analogue Scale, SF-36 | 5–6 months |

| Heij et al. 2022 [44] |

n = 292 Female: (i) 60 (c) 62 Mean age: (i) 82 (c) 81 Mobility problems |

NL |

RCT Cost-consequences, cost-utility |

Healthcare perspective | QALY (EQ-5D) | 6 months |

| Lilje et al. 2014 [65] |

n = 78 Mean age: (i) 38 (c) 45 Mixed (on a waiting list for surgery regarding neck, shoulder/arm, back, pelvis/hip, knee or leg/foot condition)+ |

SE |

RCT Cost-consequences |

Healthcare perspective | QALY (SF-6D) | 12 months |

| Sevick et al. 2000 (life) [79] |

n = 235(+) Sedentary adults |

US |

RCT (Project ACTIVE) Cost-effectiveness |

Practicing clinician | Blood pressure, heart rate, peak VO 2 (mL/kg/min), Physical Activity Recall), total treadmill time, weight |

6 months, 24 months |

| Van den Hout et al. 2005 [91] |

n = 300 Female: 79% Rheumatoid arthritis |

NL |

RCT (RAPIT-study) Cost-utility |

Societal perspective | HAQ, MACTAR, QALY (EQ-5D, SF-6D, VAS) | 24 months |

+information found in an additional paper, ~assumption of the authors, […] inclusion criteria, —not applicable, NA not available, (i) intervention, (c) control intervention, A, B publications based on the same conducted study

AU Australia, DE Germany, DK Denmark, ES Spain, FI Finland, GH Ghana, IE Ireland, IL Israel, KR South-Korea, NL Netherlands, NZ New-Zealand, RO Romania, SE Sweden, TW Taiwan, UK United Kingdom, US United States of America, LBP low back pain, EPMROM Escola Paulista de Medicina Range of Motion scale, EQ EuroQol, HAQ Health assessment Questionnaire, HOOS Hip Disability and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score, KOOS The Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score, MACTAR McMaster Toronto Arthritis Patient Preference Questionnaire, NPRS Numeric Pain Rating Scale, ODI Oswestry Disability Index, OMERACT-OARSI Outcome Measures in Rheumatology-Osteoarthritis Research Society International, OSW Osteoporosis Screening in Older Women, PFFQ Pain Free Function Questionnaire, QALY Quality-Adjusted Life Years, RDS Roland Disability score, RDQ Roland‐Morris Disability Questionnaire, ROM Range of motion, SF Short Form questionnaire, VAS Visual Analogue Scale, WOMAC The Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Arthritis Index

Fig. 2.

Years of publication of the included publications

Fig. 3.

Overview of the origin of included publications

The outcomes of the included studies needed to involve a clinical outcome as well as the economic outcome costs. The latter was evaluated from a health-payer perspective in 50 cases and in 36 cases from a societal perspective (Table 1). As the numbers indicate, some studies presented costs for both perspectives. The most frequently utilized clinical outcomes were quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs), which were assessed via the EQ-5D (n = 39) and the SF6 or SF12 (n = 9). Disease-specific disability scores were assessed second most often (n = 9), e.g. via the Roland-Morris Disability Questionnaire. Finally, pain intensity was used in five publications. The remaining publications used individual outcome measures such as bothersomeness of symptoms, a stair climbing task, and blood pressure (Table 1).

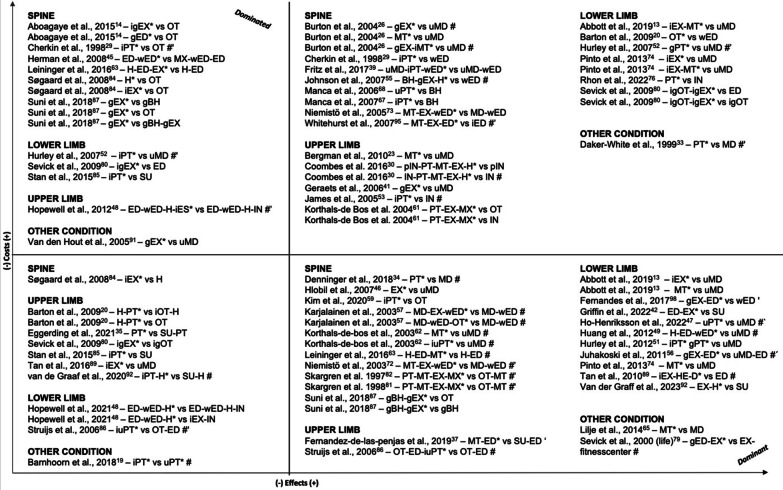

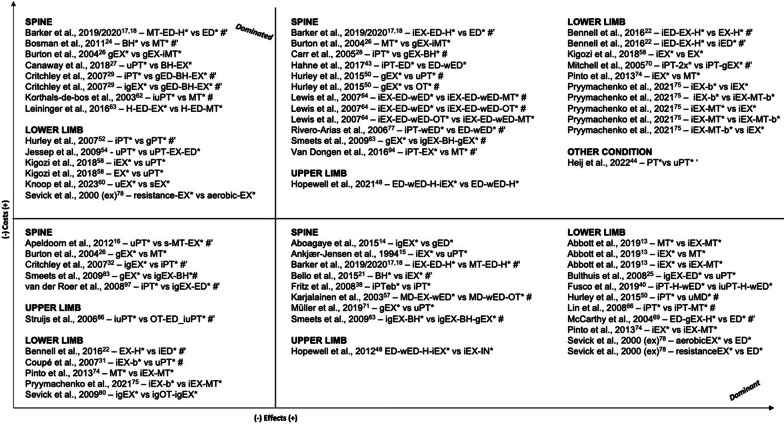

In Table 2, we present details on the interventions and highlight our defined primary intervention. The articles involved 150 comparisons between physiotherapeutic interventions and comparators. Figures 4 and 5 display the results in terms of differences in costs and effects grouped qualitatively according to the four quadrants of the cost-effectiveness plane. Eighty-one comparisons involved one treatment provided by a physiotherapist versus another non-physiotherapeutic intervention (Fig. 4), while 69 of the comparisons were between two physiotherapeutic treatments (Fig. 5).

Table 2.

Overview of interventions provided in the included trial-based economic evaluations

| Study ID | Condition, setting | Intervention(s) and comparator(s) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency | Intensity | Time | Type | ||

| Spine | |||||

| Back | |||||

|

A Barker et al. 2019 [17] B Barker et al. 2020 [18] |

Osteoporotic vertebral fracture Outpatient, rehabilitation |

(i1) Up to 7 sessions over 12 weeks (i2) up to 7 sessions over 12 weeks, home exercises daily (c) 1 session |

(i1) yes (i2) yes (c) – |

(i1) 1 h assessment, following sessions 30 min (manual therapy), 15 min (stretches) (i2) 1 h assessment, following sessions 30 min (exercise therapy), 45 min/day on 3 to 5 days (home exercises) (c) 1 h |

(i1)* manual therapy, home stretching and education (i2)* individual exercise therapy, home exercises and education (c)* education by PT |

| Müller et al. 2019 [71] |

Back pain Outpatient, therapy |

(i) 36 sessions over 6 months (week 1–12: 2x/week, week 13–24: 1x/week) (c) NA |

(i) yes (c) NA |

(i) 1 h (c) NA |

(i)* group exercise therapy (c)* usual physiotherapeutic care |

| Søgaard et al. 2008 [84] |

Lumbar spinal fusion Outpatient, rehabilitation |

(i1) 3 sessions over 8 weeks (i2) 2x/week over 8 weeks (c) 1 session |

(i1) NA (i2) NA (c) – |

(i1) 1,5 h (i2) NA (c) NA |

(i1) group meetings for interpatient exchange of experiences for the promotion of cooping (i2)* individual exercise therapy (c)* oral instruction for home exercises |

| Low back pain | |||||

| Aboagye et al. 2015 [14] |

LBP Outpatient, therapy |

(i1) 2x/week over 6 weeks, afterwards alone at least 2x/week (i2) over 6 weeks, afterwards biweekly group, and alone at least 2x/week (c) NA |

(i1) NA (i2) NA (c) – |

(i1) NA (i2) NA (c) NA |

(i1) group yoga (i2)* individual + group exercise therapy (c)* evidence-based self-care advice group by back specialist # |

| Ankjær-Jensen et al. 1994 [15] |

LBP (herniated disc) Outpatient, rehabilitation |

(i) NA (c) NA |

(i) partly (c) NA |

(i) NA (c) NA |

(i)* group exercise therapy~ (c)* usual physiotherapeutic care~ |

| Apeldoorn et al. 2012 [16] |

LBP (chronic) Outpatient, therapy |

(i) over 4 weeks minimum, afterwards treatment could change (c) NA |

(i) NA (c) NA |

(i) NA (c) NA |

(i)* stratified treatment (adjusted Delitto´s classified treatment approach): either direction specific exercises, spinal manipulation or stabilization exercises (c)* usual physiotherapeutic care |

| Bello et al. 2015 [21] |

LBP (chronic) Outpatient, therapy |

(i) 2x/week over 12 weeks (c) 2x/week over 12 weeks |

(i) yes (c) yes |

(i) 45 min (c) 45 min |

(i)* behavioral graded activity (c)* individual conventional exercise therapy program |

| Burton et al. 2004 [26] |

LBP (non-specific) outpatient, therapy |

(i1) up to 9 sessions over 12 weeks (i2) 8 sessions over 12 weeks (i3) i1 and i2 over six weeks (c) – |

(i1) NA (i2) NA (c) – |

(i1) NA (i2) NA (i3) NA (c) NA |

(i1)* group exercise therapy (i2)* spinal manipulation (i3)* group exercise therapy and individual spinal manipulation (c) usual care in GP |

| Canaway et al. 2018 [27] |

LBP Outpatient, therapy |

(i) min. 2 sessions in total+ (c) NA |

(i) yes (c) NA |

(i) initial session of 40 min, following sessions 20–30 min+ (c) NA |

(i)* individual behavior changes and exercise therapy (c)* usual physiotherapeutic care |

| Carr et al. 2005 [28] |

LBP Outpatient, therapy |

(i) 8 sessions over 4 weeks (c) at the discretion of the physiotherapist |

(i) partly (c) NA |

(i) 1 h (c) NA |

(i)* group exercise therapy incl. cognitive behavioral approach (c)* individual physiotherapy |

| Cherkin et al. 1998 [29] |

LBP Outpatient, therapy |

(i1) up to 8 additional sessions (at the discretion of therapist) (i2) up to 8 additional sessions (at the discretion of therapist) (c) – |

(i) NA (c) – |

(i1) NA (i2) NA (c) – |

(i1) chiropractic (i2)* individual physical therapy (McKenzie) (c) education by booklet |

| Critchley et al. 2007 [32] |

LBP (acute) Outpatient, therapy |

(i1) up to 8 sessions (i2) up to 8 sessions (c) up to 12 sessions |

(i1) partly (i2) partly (c) partly |

(i1) 1,5 h (i2) 1,5 h (c) 30 min |

(i1)* individual and group spinal stabilization (i2)* group education: cognitive-behavioral approach and light exercises (c)* individual physiotherapy |

| Fritz et al. 2008 [38] |

LBP (acute) Outpatient, therapy |

(i) mean: 4.6 sessions over 25.4 days (c) mean: 5.9 sessions over 29.7 days |

(i) NA (c) NA |

(i) NA (c) NA |

(i)* individual physiotherapy following evidence-based guidelines (c)* physiotherapy not following evidence-based guidelines |

| Fritz et al. 2017 [39] |

LBP Outpatient, therapy |

(i) 4 sessions over 4 weeks (c) – |

(i) NA (c) – |

(i) NA (c) NA |

(i)* usual primary care, booklet and early individual physiotherapy (c) usual primary care, booklet and waiting min. 4 weeks before considering additional treatments # |

| Hahne et al. 2017 [43] |

LBP (chronic) Inpatient, therapy |

(i) 10 sessions over 10 weeks (c) 2 sessions over 10 weeks |

(i) partly (c) – |

(i) 30 min (c) 30 min |

(i)* individual physiotherapy (pathoanatomical, psychosocial, neurophysiological) and education by PT (c)* guideline-based education by PT and booklet |

| Herman et al. 2008 [45] |

LBP Outpatient, therapy |

(i) 2x/week over 3 months (c) bi-weekly over 3 months |

(i) NA (c) – |

(i) 30 min (c) 30 min |

(i) individual neuropathic care (acupuncture, exercise and dietary advice, relaxation), education by PT and booklet (c)* standardized education by PT and booklet |

| Hlobil et al. 2007 [46] |

LBP (chronic) Outpatient, therapy |

(i) 2x/week over 3 months or until patient can fully return to previous duties (c) – |

(i) partly (c) – |

(i) 1 h (c) – |

(i)* Graded Activity intervention (c) usual care in GP |

| Hurley et al. 2015 [50] |

LBP Outpatient, therapy |

(i1) weekly phone contact over 8 weeks (i2) 1 session 1x/week over 8 weeks c) NA |

(i1) yes (i2) partly (c) NA |

(i1) NA (i2) 1 h (c) NA |

(i1)* walking program (i2)* group exercise therapy (c)* usual physiotherapeutic care |

| Johnson et al. 2007 [55] |

LBP Outpatient, therapy |

(i) 8 sessions over 6 weeks (c) – |

(i) partly (c) – |

(i) 2 h (group sessions) (c) – |

(i)* cognitive behavorial therapy, group exercise therapy and home exercises (c) education by booklet |

| Karjalainen et al. 2003 [57] |

LBP outpatient/inpatient, therapy |

(i1) 1 session (i2) 1 session (c) – |

(i1) partly (i2) NA (c) NA |

(i1) 1,5 h (i2) 75 min (c) – |

(i1)* GP visit, light mobilization, graded activity exercises, leaflet (i2) GP visit, leaflet, visit of the patient’s work site by PT to review how the patient deals with the information given (c) GP visit, leaflet |

| Kim et al. 2020 [59] |

LBP (chronic) outpatient, therapy |

(i) 6 sessions over 3 weeks (c) 6 sessions over 3 weeks |

(i) NA (c) NA |

(i) 20 min (c) 20 min |

(i)* individual physical therapy: ultrasound, electrotherapy, hot pack (c) massage chair # |

|

A Niemistö et al. 2003 [72] B Niemistö et al. 2005 [73] |

LBP (chronic) Outpatient, therapy |

(i) 4 sessions over 4 weeks (c) reinforced at 5 month follow up |

A (i) yes (c) – B (i) partly (c) – |

(i) 1 h (c) – |

(i)* individual evaluation, manipulative treatment, exercises and booklet (c) physician consultation, education by booklet about low back pain, including exercise and coping advice |

| Rivero-Arias et al. 2006 [77] |

LBP (chronic) Outpatient, therapy |

(i) up to 5 sessions (c) 1 session |

(i) NA (c) – |

(i) initial session 1 h, following sessions 30 min (c) 1 h |

(i)* individual physiotherapy and education by booklet (c)* education by PT and booklet |

| Smeets et al. 2009 [83] |

LBP Outpatient, therapy |

all: 10 weeks intervention (i1) GA: 1-3x/week, 20 sessions (3 group, 17 individual) PST: 10 sessions (i2) PST: 10 sessions GA: start at 3 weeks, 19 sessions APT: 3x/week, 30 min bicycle and 75 min strength/endurance training (c) APT: 3x/week, 30 min bicycle and 75 min strength/endurance training |

(i1) partly (i2) i1 and c combined (c) yes |

(i1) GA: 30 min PST: 1,5 h (i2) APT: 1,75 h PST: 1,5 h GA: 30 min (c) 1,75 h |

(i1)* group and individual graded activity (GA) with problem solving (PST) (i2)* c and i1 combined (c)* group active physical treatment (APT) # |

| Suni et al. 2018 [87] |

LBP (chronic) Outpatient, therapy |

(i1) i2 and i3 combined (i2) in total: 32 sessions; 2x/week over 8 weeks, followed by 1x/week instructed session and 1x/week home session over 16 weeks (i3) 4 sessions 1x/week over 4 weeks, followed by 6 sessions every third week for 24 weeks |

(i1) yes (i2) yes (i3) yes (c) – + |

(i1) 1,75 h (i2) 1 h (i3) 45 min |

(i1)* i2 and i3 combined (i2)* group exercise therapy (i3) group counseling based on cognitive behavioral learning (c) wait and see |

| van der Roer et al. 2008 [93] |

LBP Outpatient, therapy |

(i) in total: 46 sessions over 30 weeks including 3 phases, 1. phase—10 individual sessions and 20 group sessions over 3 weeks 2. phase—group sessions 2x/week over 8 weeks 3. phase—decreased frequency of sessions, more home exercises (c) number of treatment sessions at discretion of the PTs, on average 9 sessions over 6 weeks + |

(i) yes (c) yes |

(i) individual sessions: 30 min, group sessions: 1,5 h (c) NA |

(i)* group and individual exercise therapy and education by back school according to behavioral principles (c)* individual physiotherapy according to the Low Back Pain Guidelines of the Royal Dutch College for Physiotherapy # |

| Whitehurst et al. 2007 [95] |

LBP Outpatient, therapy |

(i) 1 initial session + up to 6 sessions following (c) 1 initial session + up to 6 sessions following |

(i) partly (c) – |

(i) initial session 40 min, following sessions 20 min (c) initial session 40 min, following sessions 20 min |

(i)* manual therapy, individual back-specific exercises, advice (c)* individual brief pain management based on the biopsychosocial model of care # |

| Neck | |||||

| Bosmans et al. 2011 [24] |

Neck pain (subacute) Outpatient, therapy |

(i) up to 18 sessions (c) up to 6 sessions over 6 weeks |

(i) partly (c) NA |

(i) 30 min (c) 30–45 min |

(i)* Behavioral Graded Activity (c)* manual therapy |

| Korthals-de Bos et al. 2003 [62] |

Neck pain Outpatient, therapy |

(i1) up to 6 sessions 1x/week over 6 weeks (i2) up to 12 sessions 2x/week (c) – |

(i1) partly (i2) NA (c) – |

(i1) 45 min (i2) 30 min (c) – |

(i1)* manual therapy (i2)* individual physiotherapy (exercises, optional massage or partly manual therapy) (c) usual care in GP |

| Leininger et al. 2016 [63] |

Neck pain (chronic) Outpatient, therapy |

(i1) 4 sessions of education and up to 20 sessions of SMT over 12 weeks (i2) 4 sessions of education and 20 sessions of SRE over 12 weeks (c) 4 sessions over 12 weeks |

(i) yes (c) NA |

(i1) 1 h (i2) 1 h (c) 1 h |

(i1)* home exercises and advice (HEA) and spinal manipulative therapy (SMT) (i2)* HEA and individual supervised rehabilitative exercises (SRE) (c) home exercise and advice (HEA) # |

| Lewis et al. 2007 [64] |

Neck disorders (non-specific) Outpatient, therapy |

(i1) mean: 5.79 sessions followed by up to 6 sessions over 6 weeks (i2) mean: 6.63 sessions followed by up to 6 sessions over 6 weeks (c) mean: 4.49 sessions followed by up to 6 sessions over 6 weeks |

(i1) partly (i2) partly (c) partly + |

(i1) initial session 40 min, following sessions 20 min (i2) initial session 40 min, following sessions 20 min (c) initial session 40 min, following sessions 20 min |

(i1)* c and manual therapy (i2)* c and pulsed shortwave diathermy c)* individual exercise therapy, advice by PT and booklet (Arthritis Research Campaign's “Pain in the Neck” booklet) |

| Manca et al. 2006 [68] |

Neck pain Outpatient, therapy |

(i) 1–3 sessions (c) according to individual judgment of PT |

(i) – (c) NA |

(i) NA (c) NA |

(i) cognitive-behavioral treatment c)* usual physiotherapeutic care (electrotherapy, manual therapy, advice, acupuncture, other treatments) |

| Van Dongen et al. 2016 [94] |

Neck pain (subacute and chronic) Outpatient, therapy |

(i) up to 6 sessions 1x/week or bi-weekly, determined by PT (c) up to 9 sessions up to 2x/week |

(i) NA (c) NA |

(i) 30 min—1 h (c) 30 min |

(i)* Manual Therapy according to the Utrecht school c)* individual physiotherapy, with at least 20 min of active exercises # |

| Others/mixed | |||||

| Denninger et al. 2018 [34] |

Back or neck pain Outpatient, therapy |

(i) mean: 7 sessions (c) mean: 8 sessions |

(i) NA (c) NA |

(i) NA (c) NA |

(i)* individual initial contact by direct access to a PT (back and neck program) and following physical therapy (c) initial contact by traditional medical referral # |

| Manca et al. 2007 [67] |

Back or neck pain Outpatient, therapy |

(i) mean: 3,1 sessions (SD:2,5), range: 0 to 7+ (c) mean: 4,15 sessions (SD:2,8), range: 0 to 7+ |

(i) NA (c) NA |

(i) NA (c) NA |

(i) individual Solution Finding Approach c)* individual McKenzie therapy # |

|

A Skargren et al. 1997 [82] B Skargren et al. 1998 [81] |

Back or neck pain Outpatient, therapy |

(i) mean: 6 sessions (c) mean: 5 sessions |

(i) NA (c) NA |

(i) NA (c) NA |

(i)* physiotherapy (manipulation, mobilization, traction, soft tissue treatment, McKenzie treatment, TENS, acupuncture, relaxation training, training program) (c) chiropractic (manipulation, mobilization, traction, soft tissue treatment) |

| Upper Limb | |||||

| Bergman et al. 2010 [23] |

Shoulder complaints Outpatient, therapy |

(i) up to 6 sessions over 12 weeks (c) – |

(i) yes (c) – |

(i) NA (c) – |

(i)* manual therapy (manipulative and mobilization of the cervicothoracic spine and adjacent ribs) (c) usual care in GP |

| Commbes et al. 2016 [30] |

Epicondylitis lateralis [> 6 weeks duration] Outpatient, therapy |

(i1) 8 sessions over 8 weeks (physiotherapy) (i2) 8 sessions over 8 weeks (physiotherapy) (c1) 1 session (c2) 1 session |

(i1) yes (i2) yes (c1) yes (c2) yes |

(i1) 30 min (i2) 30 min (c1) – (c2) – |

(i1)* saline injection (placebo) followed by physiotherapy (manual therapy, exercise, home exercises) (i2) corticosteroid injection followed by physiotherapy (manual therapy, exercise, home exercises) c1) saline injection (placebo) # c2) corticosteroid injection # |

| Fernandez-de-Las-penjas et al. 2019 [37] |

Carpal tunnel syndrome Outpatient, therapy |

(i) 3 sessions 1x/week (c) – |

(i) yes (c) – |

(i) 30 min (c) – |

(i)* manual therapy and education for exercises (c) open or endoscopic surgery and education for exercises |

| Geraets et al. 2006 [41] |

Shoulder complaints (chronic) Outpatient, therapy |

(i) up to 18 sessions over 12 weeks (c) – |

(i) yes (c) – |

(i) 1 h (c) – |

(i)* group graded exercise therapy (c) usual care in GP |

| Hopewell et al. 2021 [48] |

Rotator cuff disorder Outpatient, therapy |

(i1) injection and c (i2) up to 6 sessions over 16 weeks (i3) injection and i2 (c) 1 session |

(i1) – (i2) partly (i2) partly (c) – |

(i1) 1 h (i2) initial session 1 h, following sessions 20–30 min (i3) injection and i2 (c) 1 h |

(i1) c and corticosteroid injection (i2)* c and individual exercise therapy (i3) individual exercise therapy and corticosteroid injection (c)* best-practice advice by PT, education by booklet and home exercises # |

| James et al. 2005 [53] |

Shoulder pain Outpatient, therapy |

(i) up to 8 sessions over 6 weeks (c) 1 injection at beginning, if symptoms persisted patients could have 1 additional injection within 4 weeks |

(i) NA (c) – |

(i) 20 min (c) – |

(i)* individual ( ~) physiotherapy (c) corticosteroid injection into subacromial space # |

| Korthals-de Bos et al. 2004 [61] |

Epicondylitis lateralis Outpatient, therapy |

(i) max. 9 sessions 2x/week over 6 weeks (c1) 1 session (c2) 1 session |

(i) partly (c1) yes (c) – |

(i) 30 min (c1) NA (c2) NA |

(i)* physiotherapy (ultrasound, deep friction massage, exercise) (c1) corticosteroid injections # (c2) wait-and-see # |

| Struijs et al. 2006 [86] |

Epicondylitis lateralis Outpatient, therapy |

(i1) 9 sessions over 6 weeks (i2) i1 and c (c) over 6 weeks |

(i1) yes (i2) yes (c) – |

(i1) 30 min (7,5 min ultrasound, 5–10 min friction) (i2) i1 and c combined (c) wearing the brace continuously during the day |

(i1)* individual physiotherapy (ultrasound, friction massage, home exercises, if pain subsided) (i2)* i1 and c (c) brace, 1 initial PT visit for instruction |

| Lower limb | |||||

| Hip | |||||

| Fusco et al. 2019 [40] |

Hip replacement Inpatient, rehabilitation |

(i), (c) 2x/day until hospital discharge, 8 weeks home exercises, 2 weeks after discharge 1 session at home or outpatient |

(i) NA (c) NA |

(i) NA (c) NA |

(i)* individual physiotherapy without 'hip precautions' and home exercises via booklet (c)* individual physiotherapy with 'hip precautions' and home exercises via booklet |

| Griffin et al. 2022 [42] |

Femoroacetabular Impingement syndrome Outpatient, therapy |

(i) – (c) 6–10 sessions over 12–24 weeks |

(i) – (c) yes |

(i) – (c) mean: 30 min |

(i) hip arthroscopy c)* best conservative care (personalized hip therapy: education and exercise therapy, sometimes per telephone or e-mail) |

| Juhakoski et al. 2011 [56] |

Hip osteoarthritis Outpatient, therapy |

(i) 1 session (education), 12 sessions 1x/week, after that 3x/week home exercise over 2 years, 4 booster sessions 1 year later (exercise) (c) 1 session (education) |

(i) yes (c) – |

(i) 1 h (education), 45 min (exercise) (c) 1 h (education) |

(i)* group exercise therapy and education by physician (c) usual care in GP and education by physician |

| Tan et al. 2016 [88] |

Hip osteoarthritis Outpatient, therapy |

(i) max. 12 sessions over the first 3 months, followed by 3 booster sessions at month 5, 6 and 9 (c) – |

(i) NA (c) – |

(i) NA (c) – |

(i)* individual ( ~) exercise therapy (c) usual care in GP |

| Knee | |||||

| Barton et al. 2009 [20] |

Knee pain Outpatient, therapy |

(i1) dietary intervention: 15 sessions over 24 months (monthly until 6th month, then every other month) home exercises: daily, 6 sessions with a PT every 4 months over 24 months (i2) 15 sessions over 24 (i3) daily, 6 sessions with a PT over 24 months (c) – |

(i1) home exercises: partly (i2) – (i3) partly (c) – |

(i1) NA (i2) NA (i3) NA (c) – |

(i1) individual dietary intervention and quadriceps strengthening home exercises (i2) individual dietary intervention (i3)* quadriceps strengthening home exercises with PT visits (c) education by leaflet |

| Bennell et al. 2016 [22] |

Knee osteoarthritis Outpatient, therapy |

(i) 10 sessions over 12 weeks, home program: 4x/week over 12 weeks, followed by 3x/week over 9 months (c1) exercise therapy: 10 sessions home program: 4x/week over 12 weeks, followed by 3x/week over 9 months (c2) 10 sessions 1x/week |

(i) partly (c1) partly (c2) – |

(i) 70 min (c1) 25 min (exercise therapy) (c2) 45 min |

(i)* individual education (pain coping) and exercise therapy and home program (c1)* exercise therapy and home program only (c2)* individual education (pain coping) by PT # |

| Eggerding et al. 2021 [35] |

ACL tear Outpatient, rehabilitation |

(i) until good functional control was achieved + (c) according to the recommendations of the Dutch ACL guideline, min. 3 months |

(i) NA (c) NA |

(i) NA (c) NA |

(i) early ACL reconstruction, within six weeks after randomization, after that referred for individual physical therapy + (c)* supervised individual physical therapy program, then optional reconstruction+# |

| Ho-Henriksson et al. 2022 [47] |

Knee osteoarthritis Outpatient, therapy |

(i) mean: 4 individual and two group sessions; 0,3 physician visits (c) mean: 4 individual and 1,5 group sessions; 1,5 physician visits |

(i) NA (c) NA |

(i) NA (c) NA |

(i)* primary access to individual PT (education, exercise therapy, pain treatment, walking aids) and group treatment (BOA-program: education, exercise therapy) (c) primary access to physician (education, medical prescription, referrals) |

| Huang et al. 2012 [49] |

Total knee replacement Outpatient, prehabilitation |

(i) daily, over 4 weeks before surgery (c) NA |

(i) NA (c) NA |

(i) 40 min/day (c) NA |

(i)* home exercises and education before replacement by PT and booklet (c) conventional pre-TKA care |

|

A Hurley et al. 2007 [52] B Hurley et al. 2012 [51] |

Knee pain (chronic) Outpatient, therapy |

(i1) 12 sessions 2x/week over 6 weeks (i2) 12 sessions 2x/week over 6 weeks (c) – |

(i1) partly (i2) partly (c) – |

(i1) 15–20 min (i2) 15–20 min (c) – |

(i1)* ESCAPE program (exercise and self-management education) (i2)* group rehabilitation program (c) usual primary care |

| Jessep et al. 2009 [54] |

Knee pain (chronic) Outpatient, therapy |

(i) 10 sessions 2x/week over 5 weeks plus booster at 4 month plus home exercises (c) mean: 4 sessions |

(i) partly (c) NA |

(i) approx. 60 min (c) NA |

(i)* adapted ESCAPE program (exercise and self-management education) (c)* usual care by PT (exercise, advice, electrotherapy, MT) |

| Kigozi et al. 2018 [58] |

Knee osteoarthritis Outpatient, therapy |

(i1) 6–8 sessions over 12 weeks (i2) 4 sessions until week 12, 4–6 follow-ups until sixth month (c) up to 4 sessions over 12 weeks |

(i1) partly (i2) partly (c) NA |

(i1) NA (i2) NA (c) NA |

(i1)* individual exercise program (i2)* targeted exercise adherence (c)* usual physiotherapeutic care (individual exercise therapy and education by booklet) |

| Knoop et al. 2023 [60] |

Knee osteoarthritis Outpatient, therapy |

(i) 3–18 sessions individual over 12 weeks plus 1–3 booster sessions (c) mean: 10 sessions over 12 weeks |

(i) NA (c) NA |

(i) NA (c) NA |

(i)* stratified exercise therapy (c)* usual exercise therapy by PT |

| McCarthy et al. 2004 [69] |

Knee osteoarthritis Outpatient, therapy |

(i) 1 initial session (education), 2x/week over 8 weeks (exercise) (c) 1 initial session (education) |

(i) yes (exercise) (c) – |

(i) 45 min (exercise) (c) NA |

(i)* c, group exercise therapy and home exercises (c)* education by PT based on the Research Campaign's information booklet 'Osteoarthritis of the knee' and home exercises # |

| Mitchell et al. 2005 [70] |

Total knee replacement Outpatient/home, prehabilitation/rehabilitation |

(i) min. 3 pre-TKR sessions and up to 6 post-discharge sessions (c) 1-2x/week (group exercise) and at PT's discretion (individual) |

(i) NA (c) NA |

(i) NA (c) NA |

(i)* individual physiotherapy at home pre- and post-TKA (c)* individual physiotherapy and group exercise therapy post-TKA only |

| Pryymachenko et al. 2021 [75] |

Knee osteoarthritis Outpatient, therapy |

(i1) 12 sessions over 1 year (i2) 12 sessions over 9 weeks (i3) 12 sessions over 1 year (c) over 9 weeks |

(i1) partly (i2) partly (i3) partly (c) partly |

(i1) NA (i2) NA (i3) NA (c) NA |

(i1)* individual exercise therapy and booster session (i2)* individual exercise therapy and manual therapy (i3)* individual exercise therapy, manual therapy and booster session (c)* individual exercise therapy # |

| Rhon et al. 2022 [76] |

Knee osteoarthritis Outpatient, therapy + |

(i) 8 sessions over 4–6 weeks, additional 3 sessions between 4 and 9th month (c) 1 session |

(i) yes (c) – |

(i) 1 h (c) – |

(i)* physical therapy (exercises, joint mobilization) (c) glucocorticoid injection |

| Sevick et al. 2000 (ex) [78] |

Knee osteoarthritis Outpatient, therapy |

(i1), (i2) month 1–3: 3x/week of 1 h month 4–6: home exercises of 1 h, bi-weekly contact to PT (4 home visits, 6 telephone calls) month 7–9: home exercises of 1 h, every 3 weeks contact to PT (telephone calls) month 10–18: 1x/month contact to PT (telephone calls) (c) month 1–3: 3 sessions of 1,5 h month 4–6: biweekly nurse contact month 7–18: 1x/month nurse contact |

(i1) yes (i2) yes (c) – |

(i1) and (i2) month 1–3: 1 h month 4–6: home exercises of 1 h month 7–9: home exercises of 1 h month 10–18: NA month 1–3: 1,5 h month 4–6: NA month 7–18: NA |

(i1)* aerobic exercise training (3 months in a group, 15 months homebased individual) (i2)* resistance exercise (3 months in a group, 15 months homebased individual) (c)* health education |

| Sevick et al. 2009 [80] |

Knee osteoarthritis Outpatient, therapy |

(i1) 1 initial visit at home, months 1–4: monthly 3 group sessions, 1 individual session months 5–6: biweekly 3 group sessions, 1 individual months 7+: biweekly telephone call or meeting and newsletter (i2) 3x/week over 4 months, after 4 month decision: continue at facility, at home or combined (i3) i1 and i2 combined (c) months 1–3: monthly meeting months 4–5: monthly phone contact months 5+: bimonthly contact |

(i1) – (i2) yes (i3) i1 and i2 combined (c) – |

(i1) 1 initial visit at home, months 1–4: NA months 5–6: NA months 7+: NA (i2) 60 min over 4 months (i3) i1 and i2 combined (c) months 1–3: 1 h months 4–5: NA months 5+: NA |

(i1) diet: group and individual (i2)* group and individual exercise therapy (i3)* i1 and i2 combined (c) healthy lifestyle control |

| Stan et al. 2015 [85] |

Knee osteoarthritis Inpatient, therapy/operation |

(i) exercises and following PT session, 2x/day over 5 days before discharging c1) – c2) – |

(i) NA c1) – c2) – |

(i) 30 min (exercises) c1) – c2) – |

(i)* individual rehabilitation program c1) total knee arthroplasty c2) total knee arthroplasty following high tibial osteotomy # |

| Tan et al. 2010 [89] |

Patellofemoral pain syndrome Outpatient, therapy |

(i) 9 sessions over 6 weeks (c) NA |

(i) NA (c) NA |

(i) NA (c) NA |

(i)* individual exercise therapy and home exercises and c-intervention (c) education by a physician |

| Van de Graaf et al. 2020 [90] |

Meniscal tear Outpatient, therapy |

(i) 16 sessions over 8 weeks, 2x/week home exercises (c) – |

(i) yes (c) – |

(i) 30 min (individual PT) (c) – |

(i)* individual physiotherapy and home exercises (c) arthroscopic partial meniscectomy and same home exercises as i # |

| Van der Graaff et al. 2023 [92] |

Meniscal tear (traumatic) Outpatient, rehabilitation |

(i) NA (c) NA |

(i) partly |

(i) NA (c) – |

(i)* exercise programme, home exercises (c) arthroscopic partial meniscectomy |

| Others/mixed | |||||

|

A Abbott et al. 2019 [13] B Pinto et al. 2013 [74] |

Hip osteoarthritis, knee osteoarthritis Outpatient, therapy |

(i1), (i2) and (i3) 7 sessions over 9 weeks, 2 booster sessions at week 16 and 54 (c) – |

A (i1) NA (i2) NA (i3) NA (c) – B (i1) partly (i2) partly (i3) partly (c) – |

(i1) approx. 50 min (i2) approx. 50 min (i3) approx. 50 min (c) – |

(i1)* individual exercise therapy (i2)* manual therapy (i3)* individual exercise and manual therapy (c) usual care in GP |

| Bulthuis et al. 2008 [25] |

Hip osteoarthritis, knee osteoarthritis Inpatient, rehabilitation |

(i) 2x/day over 3 weeks (exercise therapy), 2x/week over 3 weeks (education) (c) NA |

(i) partly (c) NA |

(i) 75 min (exercise therapy) (c) NA |

(i)* individual and group exercise therapy and education by PT (c)* usual PT-care |

| Coupé et al.‚ 2007 [31] |

Hip osteoarthritis, knee osteoarthritis Outpatient, therapy |

(i) max. 18 session over 12 weeks and max. 7 booster sessions (c) max. 18 sessions within 12 weeks |

(i) partly (c) NA |

(i) NA (c) NA |

(i)* individual exercise therapy and booster session (c)* usual physiotherapeutic care |

| Fernandes et al. 2017 [97] |

Total hip replacement, total knee replacement Outpatient, prehabilitation |

(i) 2x/week over 8 weeks (c) – |

(i) partly (c) – |

(i) 1 h (c) – |

(i)* group neuromuscular exercise program and education by PT before surgery (c) standard preoperative information by leaflet |

| Lin et al. 2008 [66] |

Ankle fracture Outpatient, therapy |

(i) mean no. of treatment: 10 sessions, 2x/week over 4 weeks (c) first week: 2 sessions, after that 1x/week, mean number of sessions: 6 |

(i) yes (c) partly |

(i) NA (c) NA |

(i)* individual physiotherapy and manual therapy (c)* individual physiotherapy |

| Other conditions | |||||

| Barnhoorn et al. 2018 [19] |

Complex regional pain syndrome type 1 Outpatient, therapy |

(i) max. 5 sessions (c) – |

(i) NA (c) – |

(i) 40 min (c) – |

(i)* individual pain exposure physical therapy (c)* usual physiotherapeutic care+ |

| Daker-White et al. 1999 [33] |

Musculoskeletal problems Outpatient, therapy |

(i) – (c) – |

(i) – (c) – |

(i) NA (c) NA |

(i)* treatment by PT (orthopedic specialist) (c) treatment by orthopedic surgeons # |

| Heij et al. 2022 [44] |

Mobility problems Outpatient, therapy |

(i) mean: 15 sessions (c) mean: 22 sessions |

(i) partly+ | (i) 30 min+ |

(i)* physical therapy (Coach2move) (c)* usual physiotherapeutic care |

| Lilje et al. 2014 [65] |

Mixed (on a waiting list for surgery regarding neck, shoulder/arm, back, pelvis/hip, knee or leg/foot condition)+ Outpatient, therapy |

(i) up to 5 sessions over 5 weeks (c) as many appointments as required |

(i) NA (c) – |

(i) 30–45 min (c) NA |

(i)* manual therapy (c) standard care of orthopedic surgeons |

| Sevick et al. 2000 (life) [79] |

Sedentary adults Outpatient, therapy |

(i) 1x/week (1–16 week), biweekly (17–24 week), 1x/month group meeting (7–12 months), every other month group meeting (13–18 months), quarterly group meeting (19–24 months) (c) exercise (1–6 months), receiving a calendar—monthly, invitation to activities, newsletter: quarterly (7–18 months) |

(i) partly (c) yes |

(i) NA (c) 20 min—1 h (exercise) |

(i)* group education and lifestyle exercise therapy (for 6 months), individual/group—education, life exercise therapy (7–18 months) (c) 1–6 months: individual exercises at a fitness facility 7–18 months: patients had the choice if they want to continue exercising at a fitness facility, calendar of activities, invitation to activities and newsletter # |

| Van den Hout et al. 2005 [91] |

Rheumatoid arthritis Outpatient, therapy |

(i) 2x/week over 2 years, in total: 60 sessions (c) mean sessions of individual PT: 8.4 over 2 years |

(i) partly (c) – |

(i) 75 min (c) NA |

(i)* group exercise therapy ('Rheumatoid Arthritis Patients in Training'-program: weight bearing) (c) usual care in GP (individual physiotherapy if necessary) |

# control group defined by authors, +information found in an additional paper, ~assumption of the authors, […] inclusion criteria, —not applicable, *physiotherapeutic treatment, NA not available, (i) intervention, (c) control intervention, A, B publications based on the same conducted study, bold printed description of one (control-) intervention the authors’ treatment of interest

ACL anterior cruciate ligament, GP general practice, LBP low back pain, PT physiotherapist(s), prehabilitation physiotherapeutic treatment before a scheduled surgery, rehabilitation physiotherapeutic treatment after a surgery or traumatic injury, therapy physiotherapeutic treatment of a degenerative disease or an inflammatory disease

Fig. 4.

Cost-effectiveness plane of any physiotherapeutic intervention versus another non-physiotherapeutic intervention. BH, behavior; ED, education; EX, exercises; H, home; IN, injection; MD, medical doctor; MT, manual therapy; MX, mixed; OT, others; PT, physiotherapy; SU, surgery; b, booster session; eb, evidence-based; g, group; i, individual; p, placebo; s, stratified care; u, usual; w, written; 2×, twice, *physiotherapeutic intervention, #no significant differences in the health outcome, ‘no significant differences in the costs

Fig. 5.

Cost-effectiveness plane of a primary physiotherapeutic intervention vs another physiotherapeutic intervention. BH, behavior; ED, education; EX, exercises; H, home; IN, injection; MD, medical doctor; MT, manual therapy; MX, mixed; OT, others; PT, physiotherapy; SU, surgery; b, booster session; eb, evidence-based; g, group; i, individual; p, placebo; s, stratified care; u, usual; w, written; 2×, twice; *physiotherapeutic intervention, #no significant differences in the health outcome, ‘no significant differences in the costs

Critical Appraisal of the Included Articles

More than two-thirds of the included 83 trials-based economic evaluations were of high quality with sum-yes-scores of 17 (n = 13), 18 (n = 16), or 19 (n = 31) on the Consensus on Health Economic Criteria checklist (Additional file 3: Table S3). The lowest score was 11 which was observed in two articles. Scores of 12, 13, and 14 were observed in two articles each. The scores 15, and 16 were reached by five and ten articles, respectively. The three items “Is a well-defined research question posed in answerable form?”, “Is the actual perspective chosen appropriate?”, and “Are all outcomes measured appropriately?” were evaluated with a ‘Yes’ for all the articles. The lowest sum of positive evaluation was observed for the item “Does the article indicate that there was no potential conflict of interest of study researchers and funders?” (n = 58). Limitations were also observed in 23 articles when it comes to the performance of incremental analyses of the costs and outcomes of alternatives. Fifty-nine publications met the criteria regarding sensitivity analyses to account for uncertain variable values. Nonetheless, the overall article quality was high.

Results of Syntheses Grouped by Body Parts

Spine

Of our 39 articles dealing with spine-related conditions four address the back in general [17, 18, 71, 84], 25 deal with the low back [14–16, 21, 26–29, 32, 38, 39, 43, 45, 46, 50, 55, 57, 59, 72, 73, 77, 83, 87, 93, 95], six with the neck [24, 62–64, 68, 94] and four include mixed patients [34, 67, 81, 82] (Tables 1, 2).

The four articles on general back conditions [17, 18, 71, 84] built on three clinical trials. The sessions varied between 1 and 36 over a time horizon of 1 to 24 weeks. Most interventions were conducted 1–2 times per week. The duration if indicated varied between 60 and 90 min. The intervention and control groups contained individual and group-based exercise therapy, manual therapy, and education as well as usual care (Table 2). Group exercise therapy was deemed cost-effective over usual care [71] and interpatient exchange group meetings were cost-effective over increasing the frequency of traditional therapy according to the authors [84]. The articles from Barker et al. considered three interventions provided by physiotherapists [17, 18]. The findings of all cost-effectiveness comparisons can be found in Figs. 4 and 5.

The 25 articles on low back pain were built on 24 clinical trials [14–16, 21, 26–29, 32, 38, 39, 43, 45, 46, 50, 55, 57, 59, 72, 73, 77, 83, 87, 93, 95]. Niemistö et al. published two articles based on the same clinical trial [72, 73]. Patients received between 1 and 46 sessions lasting between 20 and 120 min, spread out over a maximum of 30 weeks. Sessions were most often offered 1 to 3 times a week. The treatments in the intervention and control groups included mostly group and individual exercise therapy, individual physiotherapeutic treatments, and education. Additional manual therapy, McKenzie-based treatments, behavioral graded activity, behavior change techniques, a walking program, visits at the workplace, yoga, usual care, chiropractic treatment, and a massage chair were provided (Table 2). Fritz et al. compared individual physical therapy following evidence-based guidelines to physical therapy not following those guidelines and found that following evidence-based guidelines is cost-effective [38]. The articles on low back pain included a total of 67 comparisons of interventions of which 34 were between a physiotherapeutic intervention and another treatment (Figs. 4, 5).

Of the 6 articles on neck conditions all addressed neck pain [24, 62–64, 68, 94]. One to 24 sessions were offered. They lasted between 20 and 60 min and were spread over up to 12 weeks. Most treatments were offered 1–2 times per week. The intervention contained exercises, cognitive behavioral treatment, behavior-graded activity, manual therapy, individual therapy, and advice. The control group received exercises, usual care involving physiotherapeutic treatments, and written information (Table 2). The articles involve 12 treatment comparisons. Five highlighted better outcomes at higher costs for the physiotherapeutic intervention, and three were dominant. In the four dominated investigations three of the comparison interventions were offered by physiotherapists (Figs. 4, 5).

Two of the four articles with a mixed spine population originated from the same study. These studies did not differentiate between neck and back pain [34, 67, 81, 82]. Participants received up to 8 sessions. One article focused on physiotherapeutic care in comparison to traditional medical referral care, another compared the McKenzie treatment concept to the individual solution-finding approach, and the remaining two, from the same study, compared physiotherapeutic to chiropractic care (Table 2). Considering only the effectiveness, all articles favored the intervention offered by physiotherapists, although not significantly in the articles by Skargren et al. [81,82]. In the article of Manca et al. the psychotherapeutic treatments involved higher costs [67]; dominance of the physiotherapeutic treatment was found in the remaining articles [34, 81, 82] (Figs. 4, 5).

Upper Limb

The seven papers addressing the upper limb dealt with carpal tunnel syndrome [37], epicondylitis lateralis [61, 86], and shoulder complaints [23, 41, 53] involving a rotator cuff disorder [48]. The number of intervention and control group sessions varied between 3 and 18. Patients were treated 1–2 times a week for 20 to 60 min. All but three articles involved one intervention and one control group. The exceptions involved three different intervention groups. The provided interventions contained manual therapy, education, exercises, and physiotherapeutic treatments such as friction, ultrasound, and massage. The control groups received surgery, injections, braces, and usual care. One study also included a wait-and-see approach (Table 2). The articles involve 14 treatment comparisons. The physiotherapeutic treatment for carpal tunnel syndrome was dominant [37]. The remaining comparison of physiotherapeutic interventions, but one, may as well be cost-effective, depending on the willingness to pay (Figs. 4, 5).

Lower Limb

The included 30 articles built on 28 clinical trials dealing with the lower limb. Of these trials, four addressed the hip [40, 42, 56, 88], nineteen the knee [20, 22, 35, 47, 49, 51, 52, 54, 58, 60, 69, 70, 75, 78, 80, 85, 88, 92], and five a mixed population [13, 25, 31, 36, 66, 74]. Nineteen of the clinical trials dealt with osteoarthritis including the last therapy option of a joint replacement [13, 22, 25, 31, 36, 40, 47, 49, 56, 58, 60, 69, 70, 75, 76, 78, 80, 85, 88].