Abstract

Design:

Authors reviewed medical and public health literature through May 2020. Structured terms were used to search four databases identifying articles that related to criminal justice (CJ) stigma. Included articles were in English, examined CJ stigma, and had people with CJ involvement as subjects. Articles without health outcomes were excluded. Quantitative and qualitative studies were reviewed and assessed for bias. Results were synthesized into a systematic review.

Purpose:

To determine whether criminal justice stigma affects health outcomes and healthcare utilization.

Findings:

The search yielded 25 articles relating to CJ stigma and health. Three stigma domains were described in the literature: perceived or enacted, internalized, and anticipated stigma. Tenuous evidence linked CJ stigma to health directly (psychological symptoms) and indirectly (social isolation, healthcare utilization, high-risk behaviors and housing or employment). Multiple stigmatized identities may interact to affect health and healthcare utilization.

Research implications:

Few studies examined CJ stigma and health. Articles used various measures of CJ stigma, but psychometric properties for instruments were not presented. Prospective studies with standard validated measures are needed.

Practical implications:

Understanding whether and how CJ stigma affects health and healthcare utilization will be critical for developing health promoting interventions for people with CJ involvement. Practical interventions could target stigma-related psychological distress or reduce healthcare providers’ stigmatizing behaviors.

Originality:

This was the first systematic review of CJ stigma and health. By providing a summary of the current evidence and identifying consistent findings and gaps in the literature, this review provides direction for future research and highlights implications for policy and practice.

Introduction

The United States criminal justice system has broad reach and devastating impact. At any time, approximately 1 in 100 adults are incarcerated in prison or jail. (Warren, 2008) Annually, 700,000 people are released from prison and 11 million people cycle through local jails. (West et al., 2011; Wagner and Rabuy, 2015). In 2010, there were more than 13 million arrests. (Snyder, 2012) Between 70 and 100 million Americans have a criminal record. (Vallas and Dietrich, 2014) Approximately one out of every 52 adults is on probation, parole, or some form of community supervision. African-American men experience disproportionately high contact with the criminal justice system. More than a third of all young African-American men who have dropped out of high school are incarcerated. (Western and Pettit, 2010) In contrast, the general population’s average incarceration rate is less than one percent. (Western and Pettit, 2010) Although the US is the country with the largest incarcerated population, more than 10.35 million people are held in prisons and jails around the world. (Walmsley, 2015)

Criminal justice (CJ) involvement, whether arrest, serving time in jail or prison, or being under community supervision, carries stigma in the US and other societies. Stigma can be defined as “a socially conferred mark that distinguishes individuals who bear this mark from others and portrays them as deviating from normality and meriting devaluation.” (Major et al., 2018) Multi-disciplinary scholarship reveals that CJ stigma affects employment, housing, and civic engagement; however, it is unclear whether CJ stigma affects health and engagement with the healthcare system. (Stoll and Bushway, 2008; Leasure and Martin, 2017; Poff Salzmann, 2009) People with CJ involvement have a substantial burden of chronic illness, negative interactions with the healthcare system, and suboptimal outcomes for treatable chronic conditions, which all may be exacerbated by CJ stigma. (Binswanger et al., 2011; Fox et al., 2014)

Their high burden of chronic illness put people with criminal justice involvement at risk for negative consequences from stigma. The estimates of chronic medical illness prevalence range from 43 percent of individuals to as high as 80 percent of men and 90 percent of women. (Mallik-Kane and Visher, 2008; Wilper et al., 2009) Estimates of this population’s prevalence of major depression range from 4% to 14% and psychotic illness range from 2% to 11%. (Fazel and Seewald, 2012) The prison population is aging and older people are more likely to have chronic conditions. (Maruschak and Beck, 2001; Williams et al., 2012) Mortality is especially high in the first two weeks following release from prison or jail, but risk of death, specifically for drug overdose and cardiovascular disease, remains elevated indefinitely post-release. (Binswanger et al., 2007; Zlodre and Fazel, 2012; Merrall et al., 2010) If the experience of CJ stigma directly harms health or dissuades healthcare engagement, the impact of CJ stigma could be large.

The mechanisms by which stigma affects health are incompletely understood, but the mark of stigma may directly cause psychological distress or indirectly impact health through exclusions from social participation. Research on HIV-related stigma demonstrates that stigma negatively affects mental health, reduces social support, and is associated with greater HIV symptomatology. (Earnshaw and Chaudoir, 2009) The effects of HIV stigma on health outcomes raise the question of whether CJ stigma affects mental health or medical conditions along similar pathways. People in prison or jail also have the challenge of “reentering” the community after they are released. The reentry process involves meeting basic food and housing needs, establishing social ties, and participating in social institutions—ideally achieving economic stability and full participation in civic life. (Harding et al., 2016) CJ stigma has significant potential to compound the difficulties of reentry in terms of mental or physical health and accessing care. Understanding whether and how CJ stigma affects health and efforts to seek healthcare can inform health promoting interventions for people with CJ involvement.

To address the knowledge gap relating to CJ stigma and health, we conducted a systematic review of the medical and public health literature on CJ stigma.

Methodology

In April 2017, we searched four distinct databases Ebsco Host, PubMed, Scopus, and Google Scholar for articles in English relating to CJ stigma. Ebsco Host and Google Scholar allowed for accessing studies not yet peer reviewed. We updated the search with three additional search terms in May 2020. There was no restriction on publication date. Table 1 lists the search terms and combinations. All published studies were eligible for the review, including grey literature, quasi-experimental studies, and qualitative research.

Table 1:

Search Strategya

| Search Combinations | Inclusion Criteria |

|---|---|

|

| |

| 1.) “criminal* stigma*” + “health*” | • Articles in English |

| 2.) “criminal* stigma*” + “medical care*” | • Article has primary data collection |

| 3.) “incarcerat*” + “stigma*” | • Subjects were individuals with criminal justice involvement |

| 4.)“jail*” + “stigma*” | |

| 5.)“prison*” + “stigma*” | • Article assesses stigma related to criminal justice involvement or incarceration. |

| 6.)“probation*” + “stigma*” | |

| 7.)““parole*” + “stigma*” | |

| 8.)“arrest*” + “stigma*” | |

Note that the asterisk denotes the use of a stem word in the search. For example, “incarerat*” searched multiple conjugations, including “incarceration”, “incarcerated”, and “incarcerate.”

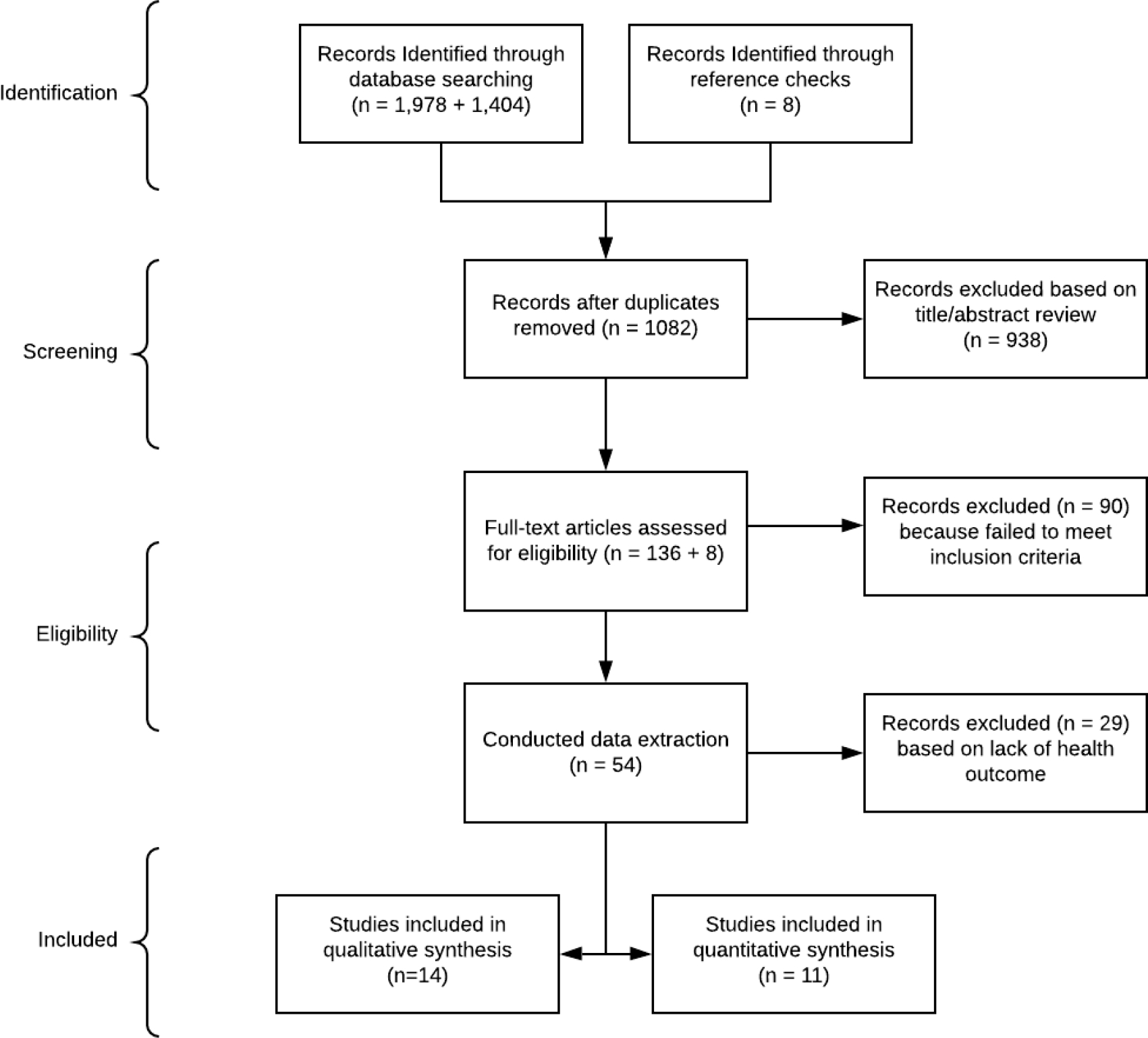

Google Scholar results for combinations three through five in Table 1 were omitted from analysis due to a prohibitively high volume (n > 10,000 in the previous two years). After removing duplicates, we identified 1082 articles for review, following PRISMA guidelines (see figure 1)

Figure 1:

PRISMA flow diagram for the systematic review describing database searches, the number of abstracts screened and the full-text articles retrieved

Unduplicated search results were reviewed independently by two team members. We first reviewed 1082 titles and abstracts excluding articles that did not pertain to the topic of CJ and health. Inclusion criteria were applied by two team members to screen article titles and abstracts. If at any point one team member felt that it was unclear whether an article met the inclusion criteria, the article was flagged for discussion and an inclusion decision was made collaboratively by the team. Following title/abstract review, 136 articles remained and the full article was subsequently reviewed by two team members for inclusion/exclusion. Inclusion criteria were applied as listed in Table 1. Forty-six articles met these inclusion criteria. Additionally, we reviewed references for the 136 articles that passed title/abstract review and eight additional articles that met inclusion criteria were added to the review. Data extraction for the 54 remaining articles was divided among three team members. Articles selected for data extraction were subject to the same original inclusion criteria with one additional exclusion criterion. Articles that did not directly examine the link between CJ stigma and health outcomes were then excluded. Specifically, articles selected for full review were passed to bias review only if at least one reviewer noted that the article specifically assessed the effects of CJ stigma on health. Close reading of the 54 articles with application of exclusion criteria resulted in 25 articles for the systematic review. If two reviewers disagreed about excluding an article, a third team member adjudicated the difference. Determinations of the type of stigma studied in the articles were made by at least two team members, relying on the definitions provided in Major et. al (2018) as applied during numerous team discussions.

Assessment for bias

Because studies include both quantitative and qualitative results, two separate bias instruments were selected to assess the quality of each study. In qualitative studies, we used the Critical Appraisal Skill Programme (CASP) Qualitative checklist. (Critical Appraisal Skill Programme, 2017) For quantitative studies we used the Quality Assessment Tool for Observational Cohort and Cross-Sectional Studies (QATOCCS) to account for a mix of cross-sectional and cohort studies. (National Health, Lung, and Blood Institute, 2018) Disagreements were addressed through a full team discussion.

Health outcomes

We characterized all study outcomes as either direct or indirect health outcomes. Direct health outcomes refer to measurable changes in physical or mental health (e.g., psychological symptoms) that were studied in relation to the experience of CJ stigma. Indirect health outcomes refer to changes in behavior (e.g., illicit substance use), relationships (e.g., social isolation), or environment (e.g., housing opportunities) that have the potential to measurably change physical or mental health but are not changes in health themselves. While substance use in some contexts could be considered a direct health outcome, we chose to categorize it with the indirect health outcomes because the included articles focused on behaviors and not health conditions themselves, such as substance use disorder. Several reviewed studies examined factors (e.g., race/ethnicity) that influenced the association between CJ stigma and health. We labeled these factors as moderators of the association. Because of heterogeneity in study design, stigma measures, and outcome measures, we did not attempt to synthesize measures of association. As our goal was to be comprehensive and not to evaluate specific outcomes, we included all outcomes and moderators whether or not authors used a theory-guided approach in selecting them.

Results

Among the included 25 articles, 14 are qualitative studies and 11 are quantitative studies. Table 2 summarizes the results of the systematic review, including results of the assessment for bias. All of the qualitative studies were descriptive in nature, while quantitative studies were most commonly cross-sectional. The final set of articles did not support conducting a meta-analysis, given the preponderance of qualitative studies and the significant variation in stigma measures and outcomes.

Table 2.

Summary of studies on criminal justice stigma, health and healthcare utilization (N = 25 studies)

| Citation | Country | Setting/Type of CJIa | Study Design | N | Stigma Typeb | Direct health outcome | Indirect health outcome | Quality | Main Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quantitative Studies c | |||||||||

| Young et al., 2005 | New York, USA | Formerly incarcerated (jail)e | Cross-sectional | 1008 | Perceived | Self-reported physical & mental health | Fair | Perceived stigma from CJI not associated with physical or mental health | |

| Winnick and Bodkin 2008 | Ohio, USA | Currently incarcerated (prison) | Cross-sectional | 450 | Internalized, Anticipated | Social isolation | Fair | Internalized stigma associated with social withdrawal as coping strategy | |

| LeBel, 2012a | New York, USA | Recently released (prison) | Cross-sectional | 204 | Perceived, Internalized | Psychological distress | Fair | Perceived stigma associated with low self-esteem | |

| Crawford et al., 2013 | USA | Formerly incarcerated (jail or prison)e | Cross-sectional | 647 | Perceived | Illicit drug use & high-risk sexual behaviors | Poor | Perceived stigma not associated with drug use or high-risk sexual behaviors | |

| Turney et al., 2013 | California, USA | Recently released (prison)f | Cross-sectional | 172 | Perceived | Psychological distress | Good | Perceived stigma associated with greater psychological distress | |

| Frank et al., 2014 | California, USA | Recently released (prison)f | Cross-sectional | 172 | Perceived | Health care utilization | Good | Perceived stigma associated with greater emergency department utilization | |

| Moore, 2015 | USA | Currently incarcerated and recently released (jail)g | Prospective cohort | 111, 79 | Perceived, Internalized, Anticipated | Psychological distress/depression | Social isolation | Fair | Anticipated stigma associated with social withdrawal and mental health symptoms; associations significant for White participants |

| West, 2015 | Canada | Currently incarcerated (forensic psychiatric facility) or engaged in mental health courte,h | Cross-sectional | 82 | Perceived, Internalized, Anticipated | Psychological distress/depression | Health care utilization | Fair | Anticipated stigma associated with greater depression and lesser treatment engagement; internalized stigma not significantly associated with outcomes |

| Moore, 2016 | USA | Recently released (jail)g | Prospective cohort – mediation model | 371 | Perceived, Anticipated | Self-reported mental health and substance use disorder symptoms | Fair | Perceived stigma does not predict mental health or substance use disorder symptoms through anticipated stigma | |

| Moore and Tangney, 2017 | USA | Recently released (jail) | Prospective cohort | 197 | Anticipated | Mental health symptoms, substance use disorder symptoms | Social withdrawal | Fair | Anticipated stigma predicts mental health symptoms but not substance use disorder symptoms or recidivism |

| Assari et al, 2018 | USA | Formerly incarcerated (jail, prison, detention center, reform school) | Cross-sectional | 1271 | Perceived | Psychological distress/depression | Fair | Perceived stigma mediates association between past incarceration and psychological distress or depressive symptoms | |

| Qualitative Studies d | |||||||||

| Dodge and Pogrebin, 2001) | Western state, USA | Recently released on parole (prison) | Descriptive study | 54 | Perceived, Internalized | Social isolation, employment | Fair | Perceived and internalized stigma due to CJI reported as a barrier to successful reentry post-release | |

| Van Olphen et al., 2009 | USA | Recently released (jail)e | Descriptive study | 17 | Perceived, Anticipated | Social isolation, high-risk behaviors, housing, employment | Fair | Stigma due to CJI and substance use overlap; stigma limits options for housing and employment (structural exclusions) | |

| Abad et al., 2013 | North Carolina, USA | Currently and formerly incarcerated (prison) | Descriptive study | 17 | Perceived, Anticipated | Social isolation, high-risk behaviors, housing | Good | Perceived CJ stigma can prevent behavior change because of structural exclusions post-release | |

| Brinkley-Rubinstein and Turner, 2013 | South-eastern state, USA | Recently released (jail or prison)i,j | Descriptive study | 12 | Perceived | Self-reported physical and mental health | Social isolation | Fair | Perceived stigma from HIV & CJI affect substance use and social networks; structural exclusions impede reentry post-release |

| Chui and Cheng, 2013 | Hong Kong, China | Recently released (prison) | Descriptive study | 16 | Perceived, Anticipated, Internalized | Social isolation | Fair | Perceived, anticipated and internalized stigma common – experienced as shame | |

| Haley et al., 2014 | North Carolina, USA | Recently released (prison)i | Descriptive study | 24 | Perceived, Internalized, Anticipated | High-risk behaviors (illicit drug use), Medication adherence | Good | Resuming substance use post-release limits engagement in HIV care; CJ stigma one reason for resuming substance use | |

| Lara-Millan, 2014 | USA | Emergency department patients (some in police custody) | Ethno-graphic Study | 1114 | N/A | Health care utilization | Good | Medical care in the emergency department influenced by patients’ CJI or staff perception of criminality | |

| Bhushan et al., 2015 | USA | Recently released (prison)i | Descriptive study | 30 | Anticipated | Health care utilization, housing, employment | Fair | Stigma due to HIV and CJI contributes to structural and psychological barriers to reentry post-release | |

| Brinkley-Rubinstein, 2015 | South-eastern state, USA | Recently released (jail or prison)i,j | Descriptive study | 12 | Perceived, Internalized, Anticipated | Self-reported physical and mental health | Social isolation | Fair | Stigma due to HIV and CJI compartmentalized; stigma internalized as self-stigma. |

| Dennis et al., 2015 | USA | Formerly incarcerated (prison)i | Descriptive study | 46 | Perceived, Anticipated | Social isolation, health care utilization, housing | Fair | Stigma from HIV and CJI affects adherence; competing demands during reentry impede health care utilization | |

| Abbott et al., 2016 | Sydney, Australia | Currently or recently incarcerated (prison) | Descriptive study | 69 | Perceived, Anticipated | Health care utilization | Good | Perception of differential care due to CJI affects health care utilization | |

| Maschi et al., 2016 | New York, USA | Formerly incarcerated (jail or prison)k | Descriptive study | 10 | Perceived, Internalized, Anticipated | Social isolation, housing | Fair | Perceived stigma due to multiple overlapping identities (LGBT, CJI, HIV status, mental health) affects prison experience (trauma, access to services) and conditions post-release (e.g., housing) | |

| Swan, 2016 | Mid-Atlantic state, USA | Recently released (jail or prison)i | Descriptive study | 30 | Perceived, Internalized, Anticipated | Health care utilization, employment | Good | Perceived stigma affects uptake of and engagement in medical care | |

| Abbott et al, 2017 | New South Wales, Australia | Pre- and post-release (prison) | Descriptive study | 40 | Perceived, Anticipated | Health care utilization | Good | CJ stigma leads to fear of being blocked from care | |

CJI = criminal justice involvement

Internalized Stigma = extent to which people with a history of incarceration endorse beliefs or feelings associated with incarceration about themselves; Perceived Stigma = extent to which people with a history of incarceration believe they have experienced discrimination or prejudice; Anticipated Stigma = how people with a history of incarceration expect they will experience discrimination or prejudice (Major et al., 2018)

bias assessed with Quality Assessment Tool for Observational Cohort and Cross-Sectional Studies (NHLBI, 2018)

bias assessed with the Critical Appraisal Skill Program Qualitative checklist (Critical Appraisal Skill Programme, 2017)

Sample of people who use drugs

Sample from Frank JW (2014) and Turney K (2013) is the same

Sample from Moore (2016) and Moore (2015) is the same

Sample of people with mental health conditions

Sample of people living with HIV

Sample from Brinkley-Rubinstein (2013) and Brinkley-Rubinstein (2015) is the same

Sample with multiple stigmatized identities

Types of Stigma and Associated Health Outcomes

Studies described three types of CJ stigma: enacted or perceived, internalized, and anticipated stigma or combinations of these domains. “Enacted” or “perceived” stigma refers to the extent to which people with a history of incarceration believe they have experienced discrimination or prejudice; “anticipated” stigma refers to how people with a history of incarceration expect they will experience discrimination or prejudice; and, “internalized” stigma refers to the extent to which people with a history of incarceration espouse “negative societal beliefs”—be it consciously or unconsciously. (Major et al., 2018)

Studies measured CJ stigma in different ways (see Table 3). The types of stigma are not mutually exclusive. Several quantitative studies proposed novel instruments to measure the different stigma domains; however, the psychometric properties and validity of different instruments were not well described or compared to each other. Qualitative studies generally used grounded theory and thematic analysis to describe the experience of CJ stigma. These studies then mapped common themes to constructs regarding stigma that had previously been published. Several of the excluded studies included novel instruments to measure criminal justice stigma, which are included in Table 3.

Table 3:

Stigma Instruments

| Author | Instrument | Novel | Included Study |

|---|---|---|---|

| Shields and de Moya, 1997 | Attitudes Towards Prisoners Scale (Melvin et al., 1985) | no | no |

| Schneider and McKim, 2003 | Two five-item questionnaires | yes | no |

| Young et al., 2005 | Single question stem with multiple response categories | yes | yes |

| Winnick and Bodkin, 2008 | Devaluation/Discrimination Belief Scale on Individuals Labeled “ex-con” (Link et al., 1989) | no | yes |

| Benson et al., 2011 | Five-item Likert scale, drawing on established criminology recommendations (Braithwaite and Braithwaite, 2001) | yes | no |

| Livingston et al., 2011 | Internalized Stigma of Mental Illness Scale (Ritsher et al., 2003) | no | no |

| Lebel, 2012a | Single question stem with multiple response categories | yes | yes |

| Lebel, 2012b | Multi-item questionnaire | yes | no |

| Crawford et al., 2013 | Single question stem with multiple response categories (Young et al., 2005) | no | yes |

| Moore et al., 2013 | Inmate Perceptions and Expectations of Stigma Measure (Mashek, 2002) | no | no |

| Moore et al., 2013 | Stigmatized Attitudes Toward Criminals scale | yes | no |

| Schnittker and Bacak, 2013 | The MacArthur Scale of Subjective Social Status, “The Ladder” (Adler et al., 2000) | no | no |

| Turney et al., 2013 | Adaptation of Klonoff Landrine scales used for racial/ethnic discrimination (Klonoff and Landrine, 1999) | yes | yes |

| Frank et al., 2014 | Adaptation of Klonoff Landrine scales used for racial/ethnic discrimination (Klonoff and Landrine, 1999) | yes | yes |

| Moore, 2015 | Adaptation of Discrimination Experiences subscale of Internalized Stigma of Mental Illness scale (Ritsher et al., 2003) | yes | yes |

| West, 2015 | Experience of Discrimination Scale (Thompson et al., 2004) | no | yes |

| West, 2015 | Beliefs About Criminals Scales, adapted from (Mashek et al., 2002) | no | yes |

| West, 2015 | Self-Stigma of Mental Illness Scale (Corrigan et al., 2006) | no | yes |

| West, 2015 | Importance to Identity Index, modified from the Importance to Identity subscale of Collective Self-Esteem Scale (Luhtanen and Crocker, 1992) | no | yes |

| West, 2015 | Twenty Statements Test (Kuhn and McPartland, 1954) | no | yes |

| Moore at al., 2016 | Inmate Perceptions and Expectations of Stigma Measure (Mashek et al., 2002) | no | yes |

| Moore and Tangney, 2016 | Internalized Stigma of Mental Illness Scale (Ritsher et al., 2003) | no | yes |

| Assari et al., 2018 | Everyday discrimination scale (Williams et al., 1997) | no | yes |

Direct Health Outcomes

The review identified tenuous evidence that CJ stigma directly affects health. Ten studies reported a direct health outcome. The most commonly assessed direct health outcomes were psychological symptoms —specifically, depressive symptoms and psychological distress.

Psychological symptoms

Eight studies reported positive associations between stigma and greater psychological distress or depressive symptoms. (Assari et al., 2018; Brinkley-Rubinstein; Brinkley-Rubinstein and Turner, 2013; 2015; Lebel, 2012a; Moore, 2015; Moore and Tangney, 2017; Turney et al., 2013; West, 2015) A cohort study with 197 men who were released from prison found that social withdrawal mediated an association between anticipated stigma prior to release and greater mental health symptoms post-release. (Moore and Tangney, 2017) One cross-sectional study demonstrated that among 172 men who were recently released from prison, higher self-rated perceived or enacted stigma was significantly associated with greater psychological distress after adjustments for confounding variables. (Turney et al., 2013) Another cross-sectional study of 204 formerly incarcerated individuals found that perceived stigma was associated with low self-esteem. (Lebel, 2012a) An ethnographic study of 12 African-American formerly incarcerated HIV-positive men, which was described in two included articles, found that stigma had negative effects on mental and physical health, along with loss of social support and delay in accessing HIV-related services. (Brinkley-Rubinstein, 2015; Brinkley-Rubinstein and Turner, 2013) A mixed-method study of people with a mental health diagnosis and CJ involvement found that anticipated stigma was associated with greater depressive symptoms. (West, 2015)

In contrast, two studies did not find a connection between CJ stigma and psychological symptoms. (Moore et al., 2016; Young et al., 2005) In a longitudinal study of 371 people who were recently released from prison, anticipated stigma did not significantly predict psychological symptoms and perceived stigma accounted for 0% of the variance in psychological symptoms. (Moore et al., 2016) Among 1,008 people who use drugs, having multiple stigmatized identities was associated with poorer mental health; however, participants did not report significant perceived stigma due to CJ involvement. (Young et al., 2005)

Indirect effects of stigma on health

Nineteen studies supported associations between CJ stigma and indirect health outcomes; however, the evidence was often tenuous. Indirect health outcomes included: social isolation, healthcare utilization, medical adherence, substance use, and high-risk sexual behavior. Some qualitative studies also proposed that insecure housing or a lack of employment opportunities could also negatively affect health via an indirect pathway.

Social Isolation

The most common indirect health outcome examined was social isolation. Two quantitative studies found that higher reported levels of internalized or anticipated stigma were associated with greater likelihood of social isolation following release from incarceration. (Moore, 2015; Winnick and Bodkin, 2008)

These findings were echoed in eight qualitative studies, which were conducted in different countries and settings. These studies explored how perceived, anticipated, and internalized CJ stigma could lead to social isolation, both from stigmatized individuals withdrawing socially and from social contacts distancing themselves from the stigmatized individual. Several of these studies described how people who anticipated stigma would narrow their social network, which subsequently limited opportunities for social support that could buffer health. (Abad et al., 2013; Brinkley-Rubinstein and Turner, 2013; Dennis et al., 2015) Additionally, several studies discussed how people with CJ involvement perceived that they were treated differently by acquaintances or service providers who learned of their criminal record, which impacted their access to social support and associated health benefits when they needed it. (Dennis et al., 2015; Dodge and Pogrebin, 2001; van Olphen et al., 2009)

Health Care Utilization and Medical Adherence

Two quantitative studies examined healthcare utilization and medical adherence as outcomes. In a study of 82 people with mental health diagnoses and histories of criminal justice involvement, the experience of internalized CJ stigma was associated with less engagement in psychosocial treatment. (West, 2015) In a cross-sectional study of 172 people who were recently released from prison, perceived CJ stigma was associated with increased emergency department utilization but not associated with primary care utilization. (Frank et al., 2014)

Six qualitative studies, explored themes related to healthcare utilization. (Abbott et al., 2017; Abbott et al., 2016; Bhushan et al., 2015; Dennis et al., 2015; Lara-Millan, 2014; Swan, 2016) A common theme described how the experience of perceived or anticipated CJ stigma led participants to avoid medical care, which was explored in different ways. For example, one study involving incarcerated and formerly incarcerated women in Australia found that women’s reluctance to disclose their CJ involvement affected continuity of health care. (Abbott et al., 2016) Another study described how anticipated stigma affected healthcare utilization post-incarceration, because participants avoided accessing care at an HIV clinic known to treat people involved with the criminal justice system. (Swan, 2016) An ethnographic study of the influence of CJ stigma in an urban emergency department found that the perception of criminality on the part of healthcare providers affected triage and treatment decisions. Patients in custody of the criminal justice system received rushed care, while patients deemed criminal by staff (e.g., seeking pain medicine) received delayed care. (Lara-Millan, 2014)

High-risk behaviors

Several studies examined the impact of CJ stigma on high-risk behaviors such as drug use and high-risk sexual behavior. Among 647 people who use drugs in New York City, experiencing perceived stigma within different categories, including CJ involvement, was assessed for associations with drug use and sexual behavior. (Crawford et al., 2013) The study found no association between perceived CJ stigma and participation in high-risk health behaviors.

In contrast, three qualitative studies suggested a relationship between CJ stigma and high-risk behaviors. In one study of 17 currently and formerly incarcerated women, anticipated and/or perceived CJ stigma was a reported barrier to reducing substance use and high-risk sexual behaviors. (Abad et al., 2013) Similarly, another study of 17 formerly incarcerated women also described how perceived and anticipated stigma could trigger resumption of illicit substance use. (van Olphen et al., 2009) A third study, which interviewed both men and women before and after release from prison, also described how experiencing perceived, anticipated, and internalized CJ stigma may influence substance use by limiting an individual’s social network to other people who use drugs or have a history of incarceration, thereby increasing substance use opportunities. (Brinkley-Rubinstein and Turner, 2013)

Housing and employment

Although not directly related to health, a common theme in many of the qualitative studies was that CJ stigma affected housing and employment opportunities, which in turn affected indirect health outcomes. Seven qualitative studies examined how housing and employment challenges could affect health. These studies reported that all forms of CJ stigma, but especially perceived stigma, was associated with decreased housing and employment opportunities, which in turn caused social isolation and impacted healthcare utilization. (Abad et al., 2013; Bhushan et al., 2015; Dennis et al., 2015; Dodge and Pogrebin, 2001; van Olphen et al., 2009; Swan, 2016)

Moderating factors on CJ stigma and health

The moderating factors described in the included studies were race/ethnicity, HIV status, substance use, the type of criminal justice involvement, and having multiple stigmatized identities.

Race/ethnicity

Three quantitative studies and two qualitative studies addressed how race/ethnicity moderated the effect of CJ stigma. A quantitative study found evidence of a causal path from internalized and anticipated stigma to social withdrawal, but when stratified by race, the association only remained for White and not Black participants. (Moore, 2015) A different study found that the association between CJ stigma (perceived and anticipated) and mental health or substance use disorder symptoms did not vary between Black and White participants. (Moore et al., 2016) One quantitative study found that non-White groups experience higher levels of anticipated CJ stigma than whites. (Winnick and Bodkin, 2008) Several qualitative studies proposed that race/ethnicity is an important factor in the experience of CJ stigma.

HIV/AIDS

We included six qualitative studies that addressed how living with HIV/AIDS, HIV stigma, and CJ stigma interact. These studies proposed that people may compartmentalize stigma from HIV status and incarceration, with the latter affecting the reentry process, through structural exclusions, meaning limitations on employment, housing, and social connectivity. (Bhushan et al., 2015; Brinkley-Rubinstein, 2015; Brinkley-Rubinstein and Turner, 2013; Swan, 2016) CJ stigma and HIV stigma may also interact to affect social connections and social withdrawal. (Brinkley-Rubinstein, 2015) Several studies described how the effect of anticipated, internalized, and perceived CJ stigma on healthcare access, medical adherence, and healthcare quality, are particularly salient for individuals with HIV due to their healthcare needs. (Haley et al., 2014; Swan, 2016)

Multiple stigmatized identities

Several qualitative studies highlighted how multiple stigmatized identities interact to affect health outcomes. Having more than one stigmatized identity (e.g. criminal history and HIV infection) can generate competing demands and plays a key role in the experience of stigma. (Brinkley-Rubinstein, 2015; Brinkley-Rubinstein and Turner, 2013; Crawford et al., 2013; Dennis et al., 2015; Swan, 2016; van Olphen et al., 2009) In addition, the experience of stigma from multiple identities may hinder positive self-identity and cause people to hide their identity furthering social isolation. (Haley et al., 2014; Lebel, 2012a)

Discussion

We identified 25 articles that examined CJ stigma and health. Overall, there were few studies and only tenuous evidence that CJ stigma affects health directly and indirectly. Types of CJ stigma included perceived, anticipated, and internalized; however, there were no standard validated measures. There was also variability in outcomes assessed with the most evidence linking CJ stigma to psychological symptoms as a direct health outcome and social isolation or suboptimal healthcare utilization as indirect health outcomes. Qualitative research also described important potential pathways from CJ stigma to health that require additional investigation. Key themes were that CJ stigma negatively affects mental health; stigma may affect health indirectly through social isolation, relapse to substance use, or limitations on housing or employment; and multiple stigmatized identities interact to affect health and healthcare utilization.

The lack of strong evidence is due to a number of factors. One, many studies were not specifically designed to examine CJ stigma and health; instead the articles focused on a related concern but nevertheless reported relevant findings. Two, the quantitative studies relied heavily on cross-sectional approaches, which prevents making the type of reliable causal claims over time that would be key to understanding health outcomes. Three, the qualitative studies tended to have small sample sizes of a narrowly defined population, often with multiple stigmatized identities, resulting in reduced generalizability (which often is not the goal of qualitative research). Fourth, in the subset of studies reporting an effect size, they were often not sizable even if they trended in the direction of supporting a connection between CJ stigma and health.

Overall, the most consistent finding was that incarceration prompts all three forms of stigma and results in psychological distress. At an individual-level, stigma may lead to affective and cognitive manifestations and maladaptive behavioral accommodations, such as social withdrawal, which also affect health outcomes. Prior research on perceived discrimination has identified pathways from discrimination to heightened physiologic stress responses to negative health outcomes. (Pascoe and Smart Richman, 2009) Qualitative studies in our review linked CJ stigma to increases in substance use, but quantitative studies did not find an association. Stigma may also reduce utilization of mental health services, wherein stigma exacerbates mental health problems but impedes potential solutions. (West, 2015) Better understanding of how individuals who experience CJ stigma cope with psychological distress could potentially lead to therapeutic interventions.

The mechanisms by which CJ stigma leads to social isolation and negative health consequences, also deserve additional attention. Criminal justice involvement may damage prior social networks, including kinship networks. (Braman, 2004; Lageson, 2016) CJ stigma at a social/community-level may damage social capital, or one’s ability to achieve goals via connections to other people. (Roberts, 2003) CJ stigma at a social/community-level may also lead to policies that enforce structural exclusions, (Ispa-Landa and Loeffler, 2016; Pager, 2003; Pogorzelski, 2005) including barriers to housing, employment, and public benefits thereby exacerbating social isolation and limiting opportunity. (Poff Salzmann, 2009; United States Department of Justice, 2016) Few studies included in our review fully examined how structural exclusions impact social relationships and health, but housing instability and unemployment are associated with poor health outcomes in general populations and are common among formerly incarcerated individuals. (Kessler et al., 1988; Kushel et al., 2001) Maintaining positive social relationships and reintegration is often a goal for recidivism prevention and would likely accrue positive health benefits.

Our findings have implications for healthcare providers, researchers, and policymakers. Even though the findings offer some support for CJ stigma affecting health, the findings are not yet sufficiently robust and well-validated enough to warrant definitive changes in clinical practice. Nevertheless, the qualitative studies consistently find psychological distress related to CJ stigma, suggesting that healthcare providers should be aware of the impact of stigma and help their patients find positive ways of coping with distress. Additionally, because of the reported stigma experienced in healthcare settings, providers should be aware of their own potentially stigmatizing behaviors. Training for healthcare providers in the needs of formerly incarcerated individuals is available. (Transitions Clinic Network) For researchers, these studies highlight the profound importance of the lived experience of people with CJ system involvement and its centrality to fully understanding health outcomes in this population. The qualitative research presented here includes the perspectives of people with CJ involvement and highlight many potential harms from CJ stigma. These potential harms have not garnered sufficient attention from academic researchers. This study indicates that policymakers concerned with mitigating the undue harms of incarceration may need to also consider the specific role of CJ stigma in health. Limitations on housing and employment were frequently mentioned by qualitative studies as affecting health and healthcare utilization. Structural exclusions imposed on people with CJ involvement likely compound social isolation and deepen marginalization.

Considerations for Future Research

Altogether, a few considerations for future research stand out. Our systematic review identified few studies that assessed CJ stigma and direct health outcomes, but rich qualitative data suggests potential mechanisms linking CJ stigma to health. Potentially important outcomes include psychological symptoms, substance use, and incident cardiovascular disease. Additional research should focus on CJ stigma, structural exclusions, and health. Several instruments used to measure CJ stigma have been proposed, but additional work on psychometric testing, especially in populations with multiple stigmatized identities is needed. Additionally, most of the studies operationalized CJ stigma in terms of incarceration (in either prison or jail). Given the significant potential to affect health and healthcare access, future research should determine whether other forms of contact with the criminal justice system, such as arrest, also affect the experience of CJ stigma with consequences for health. Finally, future research should explore the nuance of differences in perceived or internalized stigma by type of offense. For instance, those who are political prisoners or those convicted of sex offenses may experience very different levels and types of stigma than others with CJ involvement.

Limitations

This study provides the first systematic analysis of empirical work on connections between CJ stigma and health. A key strength of this study is that, by focusing on this previously largely neglected nexus, it expands understanding and provides a foundation for future work with high relevance to healthcare providers. One limitation of this study is that it excludes the broader, expansive, social science literature on how CJ stigma operates in other domains such as employment or housing. As a result, it does not include potentially useful knowledge about the mechanics of CJ stigma. Additionally, we only included studies published in English and available through four search engines.

Conclusion

In our systematic review, we identified tenuous evidence linking criminal justice stigma and health. However, a number of key themes emerge from qualitative research that point to the need for refined measurement of the effect of CJ stigma on health outcomes. In particular, greater conceptual clarity about the underlying mechanisms and replication using validated measures would significantly advance the field. This review provides a basis for further explorations of the nexus between criminal justice and health. Additional knowledge on any of these fronts may provide insight into improving health outcomes for the millions of individuals subject to CJ stigma around the world, thereby addressing a critically important aspect of public health.

Acknowledgements:

We thank the authors of the reviewed studies for their important scholarship. Dr. Fox was supported by K23DA034541 and R01DA04878 to conduct this research. We have no financial conflicts of interest to report.

Contributor Information

Karin D. Martin, Daniel J. Evans School of Public Policy, University of Washington, WA, USA.

Andrew Taylor, Daniel J. Evans School of Public Policy, University of Washington, WA, USA.

Benjamin Howell, Yale University, National Clinician Scholars Program, CT, USA.

Aaron D. Fox, Department of Medicine, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Bronx, NY, USA; Department of Medicine, Montefiore Medical Center, Bronx, NY, USA.

References

- Abad N, Carry M, Herbst JH and Fogel CI (2013), “Motivation to Reduce Risky Behaviors While in Prison: Qualitative Analysis of Interviews with Current and Formerly Incarcerated Women”, Journal of Qualitative Criminal Justice & Criminology, Vol. 1 No. 2, pp. 347–363. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abbott P, Davison J, Magin JP and Hu W (2016), “‘If they’re your doctor, they should care about you’: Women on release from prison and general practitioners”, Australian Family Physician, Vol. 45 No. 10, pp. 728–732. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abbott P, Magin P, Davison J and Hu W (2017), “Medical homelessness and candidacy: women transiting between prison and community health care”, International Journal for Equity in Health, Vol. 16 No. 130, pp. 1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adler NE, Epel ES, Castellazzo G and Ickovics JR (2000), “Relationship of subjective and objective social status with psychological and physiological functioning: preliminary data in healthy, white women”, Health Psychology, Vol. 19 No. 6, pp. 586–592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Assari S, Mille RJ, Taylor RJ, Mouzon D, Keith V and Chatters LM (2018), “Discrimination fully mediates the effects of incarceration history on depressive symptoms and psychological distress among African American men”, Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities, Vol. 5, pp. 243–252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benson ML, Alarid FL, Burton SV, and Cullen TF (2011), “Reintegration or stigmatization? Offender’s expectations of community re-entry”, Journal of Criminal Justice, Vol. 39 No. 5, pp. 385–393. [Google Scholar]

- Bhushan A, Brown SE, Marcus R and Altice FL (2015), “Explaining poor health-seeking among HIV-infected released prisoners”, International Journal of Prisoner Health, Vol. 11 No. 4, pp. 209–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binswanger IA, Stern MF, Deyo RA, Heagerty PJ, Cheadle A, Elmore JG and Koepsell TD (2007), “Release from prison—a high risk of death for former inmates”, New England Journal of Medicine, Vol. 356 No. 2, pp. 157–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binswanger IA, Nowels C, Corsi KF, Long J, Booth RE, Kutner J and Steiner JF (2011), “‘From the prison door right to the sidewalk, everything went downhill,’ a qualitative study of the health experiences of recently released inmates”, International Journal of Law and Psychiatry, Vol. 34 No. 4, pp. 249–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braithwaite J and Braithwaite V (2001), “Shame, shame management, and regulation”, Ahmed E., Harris N., Braithwaite J. and Braithwaite V. (Eds), Shame management through reintegration, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK, pp. 3–69. [Google Scholar]

- Braman D (2004), “Families and the moral economy of incarceration’, Journal of Religion & Spirituality in Social Work: Social Thought, Vol. 23 No. 1–2, pp. 27–50. [Google Scholar]

- Brinkley-Rubinstein L (2015), “Understanding the Effects of Multiple Stigmas Among Formerly Incarcerated HIV-Positive African American Men”, AIDS Education and Prevention, Vol. 27 No. 2, pp.167–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brinkley-Rubinstein L and Turner WL (2013), “Health impact of incarceration on HIV-positive African American males: a qualitative exploration.” AIDS Patient Care and STDs, Vol. 27 No. 8, pp. 450–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chui HW and Cheng KK (2013), “The mark of an ex-prisoner: perceived discrimination and self-stigma of young men after prison in Hong Kong”, Deviant Behavior, Vol. 34 No. 8, pp. 671–684. [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan PW, Watson AC and Barr L (2006), “The self-stigma of mental illness: implications for self-esteem and self-efficacy”, Journal of Social & Clinical Psychology, Vol. 25 No. 8, pp. 875–884. [Google Scholar]

- Crawford ND, Ford C, Galea S, Latkin C, Jones KC and Fuller CM. (2012), “The relationship between perceived discrimination and high-risk social ties among illicit drug users in New York City, 2006–2009”, AIDS and Behavior, Vol. 17 No. 1, pp. 419–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Critical Appraisal Skill Programme. (2017), “CASP Qualitative Checklist”, available at: http://www.casp-uk.net/casp-tools-checklists/ (accessed 25 April 2019).

- Dennis CA, Barrington C, Hino S, Gould M, Wohl D and Golin CE (2015), “‘You’re in a world of chaos’: Experiences accessing HIV care and adhering to medications after incarceration”, Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care. Vol. 26 No. 5, pp. 542–555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodge M and Pogrebin MR (2001), “Collateral costs of imprisonment for women: complications of reintegration”, The Prison Journal, Vol. 81 No. 1, pp. 42–54. [Google Scholar]

- Earnshaw VA and Chaudoir SR (2009), “From conceptualizing to measuring HIV stigma: a review of HIV stigma mechanism measures”, AIDS and Behavior, Vol. 13 No. 6, pp.1160–1177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fazel S and Seewald K (2012), “Severe mental illness in 33,588 prisoners worldwide: systematic review and meta-regression analysis”, British Journal of Psychiatry, Vol. 200 No. 5, pp. 364–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox AD, Anderson MR, Bartlett G, Valverde J, Starrels JL and Cunningham CO (2014), “Health outcomes and retention in care following release from prison for patients of an urban post-incarceration transitions clinic”, Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved, Vol. 25 No. 3, pp.1139–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank JW, Wang EA, Nunez-Smith M, Lee H and Comfort M (2014), “Discrimination based on criminal record and healthcare utilization among men recently released from prison: a descriptive study”, Health Justice, Vol 2 No. 6, pp. 1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haley DF, Golin CE, Farel CE, Wohl DA, Scheyett AM, Garrett JJ, Rosen DL and Parker SD (2014), “Multilevel challenges to engagement in HIV care after prison release: a theory-informed qualitative study comparing prisoners’ perspectives before and after community reentry”, BMC Public Health, Vol. 14 No. 1253, pp. 1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harding DJ, Morenoff JD, Dobson CC, Lane EB, Opatovsky K, Williams EG and Wyse J (2016), “Families, Prisoner Reentry, and Reintegration”, Burton LM., Burton D., McHale SM., King V. and Van Hook J (Eds), Boys and Men in African American Families, Springer International Publishing, Switzerland, pp.105–160. [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Turner JB and House JS (1988), “Effects of unemployment on health in a community survey: main, modifying, and mediating effects”, Journal of social issues, Vol. 44 No. 4, pp. 69–85. [Google Scholar]

- Klonoff EA and Landrine H (1999), “Cross-validation of the schedule of racist events”, Journal of Black Psychology, Vol. 25 No. 2, pp. 231–254. [Google Scholar]

- Kuhn M and McPartland TS (1954), “An empirical investigation of self-attitudes”, American Sociological Review, Vol. 19 No. 1, pp. 68–76. [Google Scholar]

- Kushel MB, Vittinghoff E and Haas JS (2001), “Factors associated with the health care utilization of homeless persons”, JAMA, Vol. 285 No. 2, pp. 200–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lageson SE (2016), “Found out and opting out: the consequences of online criminal records for families”, The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, Vol. 665 No. 1, pp.127–141. [Google Scholar]

- Lara-Millán A (2014), “Public emergency room overcrowding in the era of mass imprisonment”, American Sociological Review, Vol. 79 No. 5, pp. 866–887 [Google Scholar]

- Leasure P and Martin T (2017), “Criminal records and housing: an experimental study”, Journal of Experimental Criminology, Vol. 13 No. 4, pp. 527–535. [Google Scholar]

- Lebel TP (2012a), “If one doesn’t get you another one will”, The Prison Journal, Vol. 92 No. 1, pp. 63–87. [Google Scholar]

- Lebel TP (2012b), “Invisible stripes? Formerly incarcerated persons’ perceptions of stigma”, Deviant Behavior, Vol. 33 No. 2, pp. 89–107. [Google Scholar]

- Link BG, Cullen FT, Struening E, Shrout PE and Dohrenwend BP (1989), “A modified labeling theory approach to mental disorders: an empirical assessment”, American Sociological Review, Vol. 54 No. 3, pp. 400–423. [Google Scholar]

- Livingston DJ, Rossiter RK and Verdu-Jones NS (2011), “‘Forensic’ labeling: an empirical assessment of its effects on self-stigma for people with severe mental illness”, Psychiatry Research, Vol. 188 No. 1, pp. 115–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luhtanen R and Crocker J (1992), “A collective self-esteem scale: self-evaluation of one’s social identity”, Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, Vol. 18 No. 3, pp. 302–318. [Google Scholar]

- Major B, Dovidio JF, Link BG and Calabrese SL (2018), “Stigma and Its Implications for Health: Introduction and Overview”, Major B., Dovidio JF. and Link BG. (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Stigma, Discrimination, and Health, Oxford University Press, New York, NY, pp. 3–28. [Google Scholar]

- Mallik-Kane K and Visher C (2008). “Health and prisoner reentry: how physical, mental, and substance abuse conditions shape the process of reintegration”, Washington DC: The Urban Institute Justice Policy Center, available at: https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/31491/411617-Health-and-Prisoner-Reentry.PDF/ (accessed 25 April 2019). [Google Scholar]

- Ispa-Landa S and Loeffler CE (2016), “Indefinite punishment and the criminal record: stigma reports among expungement-seekers in Illinois”, Criminology, Vol. 54 No. 3, pp. 387–412. [Google Scholar]

- Melvin KB, Gramling LK and Gardner WM (1985), “A scale to measure attitudes toward prisoners”, Criminal Justice and Behavior, Vol. 12 No. 2, pp. 241–253. [Google Scholar]

- Merrall ELC, Kariminia A, Binswanger IA, Hobbs MS, Farrell M, Marsden J, Hutchinson SJ and Bird SM (2010), “Meta-analysis of drug-related deaths soon after release from prison”, Addiction, Vol. 105 No. 9, pp.1545–1554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maruschak LM and Beck AJ (2001), “Medical problems of inmates, 1997”, Washington, DC: US Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistic, NCJ 181644, available at: https://static.prisonpolicy.org/scans/bjs/mpi97.pdf/ (accessed 25 April 2019). [Google Scholar]

- Mashek D, Meyer P, McGrath J, Stuewig J and Tangney JP (2002), “Inmate Perceptions and Expectations of Stigma (IPES)”, George Mason University, Fairfax, VA. [Google Scholar]

- Maschi T, Rees J and Klein E (2016), “‘Coming Out’ of prison: An exploratory study of LGBT elders in the criminal justice system”, Journal of Homosexuality, Vol. 63 No. 9, pp. 1277–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore K (2015), “A longitudinal model of internalized stigma, coping, and post-release adjustment in criminal offenders”, dissertation, George Mason University, Fairfax, Virginia, pp. 1–130. [Google Scholar]

- Moore K, Stuewig J and Tangney J (2013), “Jail inmates’ perceived and anticipated stigma: implications for post-release functioning”, Self and identity, Vol.12 No. 5, pp. 527–547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore KE, Stuewig JB and Tangney JP (2016), “The effect of stigma on criminal offenders’ functioning: A longitudinal mediational model”, Deviant Behavior, Vol. 37 No. 2, pp. 196–218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore KE and Tangney JP (2017), “Managing the concealable stigma of criminal justice system involvement: a longitudinal examination of anticipated stigma, social withdrawal, and post–release adjustment”, Social Issues, Vol. 73 No. 2, pp. 322–340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. (2018), “Quality Assessment Tool for Observational Cohort and Cross-Sectional Studies”, available at: https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/study-quality-assessment-tools/ (accessed 25 April 2019).

- Pager D (2003), “The mark of a criminal record’, American Journal of Sociology, Vol. 108 No. 5, pp. 937–75. [Google Scholar]

- Pascoe EA and Smart Richman L (2009), “Perceived discrimination and health: a meta-analytic review”, Psychological Bulletin, Vol.135 No. 4, pp. 531–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poff Salzmann K (2009), “Internal exile: collateral consequences of conviction in federal laws and regulations”, Chicago, IL: American Bar Association, available at: https://www.americanbar.org/content/dam/aba/migrated/cecs/internalexile.authcheckdam.pdf/ (accessed 25 April 25, 2019). [Google Scholar]

- Pogorzelski W, Wolff N, Pan KY, and Blitz CL (2005), “Behavioral Health Problems, Ex-Offender Reentry Policies, and the ‘Second Chance Act’”, American Journal of Public Health, Vol. 95 No.10, pp.1718–1724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritsher JB, Otilingam PG and Grajales M (2003), “Internalized stigma of mental illness: psychometric properties of a new measure”, Psychiatry Research, Vol. 121 No. 1, pp. 31–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts DE (2003), “The social and moral cost of mass incarceration in African American communities”, Stanford Law Review, Vol. 56 No. 5, pp. 1271–1305. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider A and McKim W (2003), “Stigmatization among probationers”, Journal of Offender Rehabilitation, Vol. 38 No. 1, pp. 19–31. [Google Scholar]

- Schnittker J and Bacak V (2013), “‘A mark of disgrace or a badge of honor?: subjective status among former inmates”, Social Problems, Vol. 60 No. 2, 234–254. [Google Scholar]

- Shields KE and de Moya D (1997), “Correctional Health Care Nurses’ Attitudes Toward Inmates. Journal of Correctional Health Care. 1997; 4(1): 37–59. [Google Scholar]

- Snyder H (2012), “Arrest in the United States, 1990–2010”, Washington, DC: US Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics, NCJ 239423, available at: https://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/aus9010.pdf/ (accessed 25 April 2019). [Google Scholar]

- Stoll MA and Bushway SD (2008), “The effect of criminal background checks on hiring ex-offenders”, Criminology & Public Policy, Vol. 7 No. 2, pp. 371–404. [Google Scholar]

- Swan H (2016), “A qualitative examination of stigma among formerly incarcerated adults living with HIV”, SAGE open, Vol. 6 No. 1, pp. 1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson VL, Noel JG and Campbell J (2004), “Stigmatization, discrimination, and mental health: the impact of multiple identity status”, American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, Vol. 74 No. 4, pp. 529–544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Transitions Clinic Network. “Training & Technical Assistance”, San Francisco, CA: The Transitions Clinic Network, available at: https://transitionsclinic.org/program-implementation/. (accessed May 24, 2020). [Google Scholar]

- Turney L, Lee H and Comfort M (2013), “Discrimination and psychological distress among recently released male prisoners”, American Journal of Men’s Health, Vol. 7 No. 6, pp. 482–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United States Department of Justice. (2016), “Roadmap to Reentry: Reducing recidivism through reforms at the federal bureau of prisons”, Washington, DC: United States Department of Justice, available at: www.justice.gov/archives/reentry/file/844356/download (accessed 14 June 2020). [Google Scholar]

- Vallas R and Dietrich S (2014), “One strike and you’re out: how we can eliminate barriers to economic security and mobility for people with criminal records”, Washington, DC: Center for American Progress, available at: https://cdn.americanprogress.org/wpcontent/uploads/2014/12/VallasCriminalRecordsReport.pdf/. (accessed 25 April 2019). [Google Scholar]

- van Olphen J, Eliason MJ, Freudenberg N and Barnes M (2009), “Nowhere to go: how stigma limits the options of female drug users after release from jail”, Substance Abuse Treatment, Prevention, and Policy, Vol 4 No.10, pp. 1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner P and Rabuy B (2015), “Mass Incarceration: The Whole Pie 2015”, Northampton, MA: Prison Policy Initiative, available at: https://www.prisonpolicy.org/reports/pie2015.html/ (accessed April 25, 2019). [Google Scholar]

- Walmsley R (2015), “World Prison Population List, eleventh edition”, International Centre for Prison Studies, available at: https://www.prisonstudies.org/sites/default/files/resources/downloads/world_prison_population_list_11th_edition_0.pdf (accessed 14 June 2020)

- Warren J (2008). “One in 100: Behind Bars in America”, Washington, DC: Pew Charitable Trusts, available at: https://www.pewtrusts.org/~/media/legacy/uploadedfiles/pcs_assets/2008/one20in20100pdf.pdf/ (accessed 25 April 2019). [Google Scholar]

- West HC, Sabol WJ and Greenman SJ (2011), “Prisoners in 2009”, Washington, DC: US Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics, NCJ 231675, available at: https://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/p09.pdf/ (accessed 25 April 2019). [Google Scholar]

- West ML (2015), “Triple stigma in forensic psychiatric patients: mental illness, race, and criminality”, dissertation, City University of New York, New York, New York, pp. 1–134. [Google Scholar]

- Western B and Pettit B (2010), “Incarceration & social inequality”, Daedalus, Vol. 139 No. 3, pp.8–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams BA, Stern MF, Mellow J, Safer M and Greifinger RB (2012), “Aging in correctional custody: setting a policy agenda for older prisoner health care”, American Journal of Public Health, Vol. 102 No. 8), pp. 1475–1481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams DR, Yu Y, Jackson JS and Anderson NB (1997), “Racial differences in physical and mental health: socioeconomic status, stress and discrimination”, Journal of Health Psychology, Vol. 2, pp. 335–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilper AP, Woolhandler S, Boyd WJ, Lasser KE, McCormick D, Bor DH and Himmelstein DU (2009), “The health and health care of US prisoners: results of a nationwide survey”, American Journal of Public Health, Vol. 99 No. 4, pp. 666–672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winnick TA and Bodkin M (2008), “Anticipated stigma and stigma management among those to be labeled ‘ex-con’”, Deviant Behavior, Vol. 29 No. 4, pp. 295–333. [Google Scholar]

- Young M, Stuber J, Ahern J and Galea S (2005), “Interpersonal discrimination and the health of illicit drug users”, American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, Vol. 31 No. 3, pp. 371–391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zlodre J and Fazel S (2012), “All-cause and external mortality in released prisoners: systematic review and meta-analysis”, American Journal of Public Health, Vol. 102 No. 12, pp. e67–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]