Abstract

Previous work on the strict late (γ) UL38 promoter of herpes simplex virus type 1 identified three cis-acting elements required for wild-type levels of transcription: a TATA box at −31, a consensus mammalian initiator element at the transcription start site, and a downstream activation sequence (DAS) at +20 to +33. DAS is found in similar locations on several other late promoters, suggesting an important regulatory role in late gene expression. In this communication, we further characterize the interaction between DAS and a cellular protein which is found in both uninfected and infected nuclear extracts. This protein was purified from HeLa nuclear extracts and identified as the DNA binding component (Ku heterodimer) of DNA-dependent protein kinase (DNA-PK) by peptide mapping. Highly purified DNA-PK was able to stimulate UL38 transcription in vitro approximately 10-fold. DAS is similar in sequence to another element, nuclear regulatory element 1 (NRE1) of the glucocorticoid-responsive mouse mammary tumor virus long terminal repeat. NRE1 is known to specifically bind Ku in the absence of DNA ends. We demonstrated that NRE1 is able to substitute for DAS in the UL38 promoter to activate transcription as measured by in vitro transcription and in vivo during infection of tissue culture cells with recombinant virus. Also, we found that the binding of DNA-PK to DAS involves the bases demonstrated to be important in UL38 transcription and that the 70-kDa subunit of Ku binds to DAS.

As with the vast majority of nuclear replicating DNA viruses, herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) gene expression can be readily divided into two groups: early genes are expressed before the onset of viral genome replication, and late genes are expressed maximally after this event. Transcriptional regulation by viral immediate-early proteins plays a major role in differential viral gene expression. Although HSV promoters are structurally similar to cellular promoters, their regulated transcription is influenced by a complex regulatory hierarchy involving both viral and cellular proteins (reviewed in references 41 and 42).

The major HSV-1 regulatory protein, ICP4, plays an important role in activating gene expression of promoters from all kinetic classes, presumably by stabilizing the formation of preinitiation complexes through TFIID on transcriptionally active promoters (4). ICP0 is also clearly involved in late gene expression, although it is dispensable at high multiplicities of infection (3). A third immediate-early regulatory protein, ICP27, is also involved in the early/late switch. A major function appears to be at a posttranscriptional level through the interference of splicing of cellular transcripts and selective transport of unspliced mRNAs (15, 16, 37).

Active repression of late promoters by direct DNA-protein interactions prior to genome replication does not appear to have a major role in the switch from early to late gene expression. Rather, it appears that the interaction between specific proteins modulating transcription and their cognate recognition sites within HSV promoters defines promoter strength. The strongest evidence for this view is that while both strict late and leaky-late promoters are active at maximal rates within the context of the viral genome only upon replication, these promoters are essentially as active as early promoters when introduced into cells by transfection or when assayed by in vitro transcription. Further, those mutations which result in a loss of late promoter activity show equivalent deficiencies when transcript levels are measured in recombinant virus infections or during in vitro transcription using uninfected nuclear extracts (13, 18).

The onset of viral DNA replication is important in the shutoff of early gene expression and the commencement of late gene expression (41). Nuclear structures (nuclear domain 10 [ND10]) of unknown cellular function that contain the PML protein may function as transcription centers early in infection (25). Viral regulatory proteins are localized to these regions prior to their ICP0-mediated dispersal at approximately 4 h postinfection (24). Viral DNA synthesis and late transcription take place within the nucleus of the infected cell in compartments whose formation is also mediated by viral functions (29). Alteration in nuclear compartmentalization could prove to have an important role in the switch from early to late gene expression.

Our laboratory has focused on using modified promoters inserted into nonessential loci within the viral genome as a means for identifying common structural features of viral promoters with the goal of defining prototypes of the various kinetic classes (39). Our current picture of the changing transcriptional program of the virus as infection proceeds envisions all viral promoters being equivalently available in the general transcriptional environment. In this context, alterations in the availability of cellular transcription factors, the myriad of actions of viral regulatory proteins, alterations in nuclear structure, and an exponential increase in transcriptionally active template after viral DNA replication are all factors to be considered in understanding the basis for the differential temporal expression of different kinetic classes of viral promoters.

Previous work from our laboratory and other laboratories has defined important cis-acting elements in a group of structurally related strict late (γ) promoters (12–14, 20, 43). This type of late promoter, of which those controlling the expression of UL38, US11, gC, and UL49.5 are examples, requires three elements for wild-type levels of gene expression within the context of the viral genome. These are a TATA box at about −30, a consensus mammalian initiator (Inr) element at the transcription initiation site, and the downstream activation sequence (DAS) at +20 to +30. This promoter structure suggests a common mechanism of late transcriptional activation and is similar to the core features of cellular promoters such as those for hsp70 (35), c-mos (33), and the gene encoding glial fibrillary acid protein (31).

Critical mutations to DAS in the context of the UL38 promoter can reduce transcription to less than 10% of wild-type levels without affecting the kinetics of expression as measured through recombinant virus infections of tissue culture cells (13). As described previously, we identified the core bases of DAS and detected a specific DNA-protein interaction between DAS and a cellular protein (DAS binding factor [DBF]) by electrophoretic mobility shift assay (13). In this communication, we further explore the function of DAS in late gene expression and characterize the interaction between DAS and this protein, which we show to be the DNA binding component (Ku heterodimer) of DNA-dependent protein kinase (DNA-PK).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Viruses and cells.

The propagation and maintenance of cells and viruses were as previously described (10, 14). HeLa S3 spinner cultures were provided by the National Cell Culture Center (Minneapolis, Minn.).

The promoters UL38Δ+9/DAS and UL38Δ+9/das3 were previously described (their structures are shown in Fig. 4A) (13). The mutation of four bases in the center of DAS results in the UL38Δ+9/das3 plasmid, which has extensively reduced binding capacity for DBF. This mutation in reporter plasmid or recombinant virus exhibit a level of expression of less than 10% of wild-type levels.

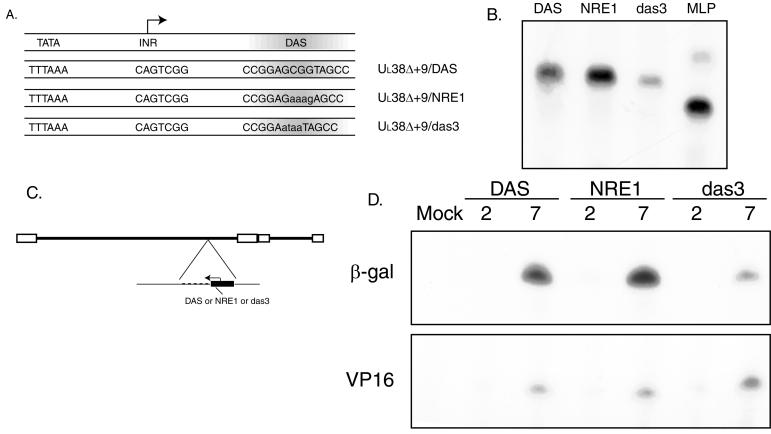

FIG. 4.

Substitution of DAS with NRE1 in the context of UL38. (A) Schematic diagram of the promoters used. The three elements required for wild-type expression of UL38 are shown. Bases altered relative to DAS are indicated by lowercase letters. (B) In vitro transcription reactions using either UL38Δ+9/DAS (DAS), UL38Δ+9/NRE1 (NRE1), UL38Δ+9/das3 (das3), or Ad MLP/β-gal (MLP). Supercoiled plasmids were used at a concentration of 500 ng, and transcripts were analyzed by primer extension using a β-galactosidase-specific primer. (C) Structure of recombinant viruses. The UL38 promoter constructs (dark rectangle) controlling β-galactosidase (dashed line) were inserted into the gC locus of the UL in the viral genome as diagramed. (D) At the indicated times (2 or 7 h postinfection), RNA was harvested from the cells that had been infected with either UL38Δ+9/DAS, UL38Δ+9/NRE1, or UL38Δ+9/das3 or not infected (mock) and subjected to primer extension analysis using either a β-galactosidase (β-gal)-specific primer or a VP16-specific primer.

The UL38Δ+9/nuclear regulatory element 1 (NRE1) promoter was generated by cloning double-stranded oligonucleotides (5′-GATCTCCCGGCCGGAGAAAGAGCCTCCC-3′ and 5′-CCGGGGGAGGCTCTTTCTCCGGCCGGGA-3′) into the BglII/SmaI site of UL38Δ+9/DAS in pGEM3 (Promega). To generate the recombinant virus, the plasmid was digested with XbaI/Asp718, and the promoter fragment was cloned into a gC recombination cassette followed by transfection into cells with infectious DNA and screening procedures as described previously (10, 14). Purity of the virus was assessed by PCR, and the promoter sequence was confirmed by dideoxy sequencing (14).

Protein purification.

Nuclear extracts were generated from spinner cultures of HeLa S3 cells by a modification of the method of Dignam et al. (5). Chromatographic steps (summarized in Fig. 2A) included P11 phosphocellulose (Whatman), Q Sepharose (Pharmacia), and heparin-Sepharose (Pharmacia). Fractions were analyzed for activity by gel shift using conditions previously described (13), and protein concentration was measured by a commercial protein assay kit (Bio-Rad). A preparative gel shift was used as a final step, similar to the method described by Gander et al. (7). Material corresponding to DBF was excised from a gel, electroeluted, acetone precipitated, and resuspended in sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) sample buffer prior to electrophoresis on a 10% polyacrylamide gel containing SDS. Native eluted DBF was prepared as described above except preparative gel slices containing the DBF-DAS complex were incubated in D buffer (20 mM HEPES [pH 7.9], 0.2 mM EDTA, 20% glycerol, 0.1 M KCl, 0.5 mM dithiothreitol, 0.5 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride) containing 0.05% Nonidet P-40 with shaking overnight at 4°C and concentrated by heparin-Sepharose chromatography and ultrafiltration.

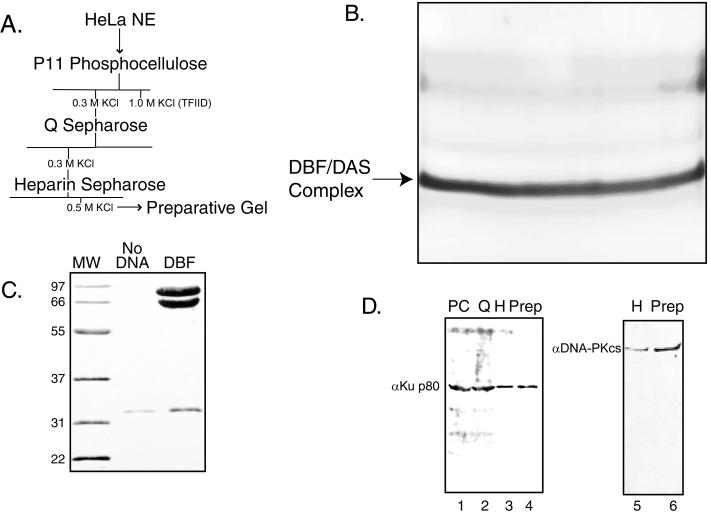

FIG. 2.

Purification and identification of DBF as the DNA binding component of DNA-PK. (A) Strategy for purification of DBF from uninfected HeLa nuclear extracts (NE). The elution of TFIID from P11 phosphocellulose (1.0 M KCl) is indicated. The presence of DBF was determined by a competitive gel shift assay as shown in Fig. 1. (B) Preparative gel shift. Fractions containing DBF after heparin-Sepharose chromatography (0.5 M KCl elution) were dialyzed against gel shift binding buffer (10 mM HEPES [pH 7.9], 10% glycerol, 25 mM KCl, 0.5 mM EDTA, 2.5 mM phosphate buffer [pH 7.9], 0.1% Nonidet P-40, 2.5 mM dithiothreitol, 0.5 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride) and used in a gel shift reaction that was scaled up approximately 250-fold. Only the DBF-DAS complex is shown, as unbound probe was run off the gel. (C) Twelve percent denaturing polyacrylamide protein gel of DAS-affinity purified DBF. The DBF-DAS complex shown in panel B as well as the corresponding region from a control gel shift reaction without DNA were isolated and run on a 12% polyacrylamide gel containing SDS followed by Coomassie blue staining. A nonspecific protein band (found in reactions without DNA and with DAS DNA) of about 33 kDa was obtained as well as two bands specific for DAS DNA of about 70 and 86 kDa. MW, molecular weight standards (positions are shown with numbers in thousands on the left). (D) Immunoblot analysis of DBF-containing protein fractions. Fractions determined to have DBF activity by gel shift assay were analyzed by Western blotting after electrophoresis on either a 10% (Ku) or 7% (DNA-PKcs) polyacrylamide gel containing SDS and transfer to nitrocellulose. Primary antibody concentrations used were anti-Ku p86 at 1:2,000 and anti-DNA-PKcs at 1:50,000. Horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies, donkey anti-goat (Ku) and goat anti-rabbit, were used at dilutions of 1:2,500. Protein extracts loaded: lane 1, P11 phosphocellulose (PC) 0.3 M elution; lane 2, Q Sepharose (Q) 0.3 M elution; lane 3, heparin-Sepharose (H) 0.5 M elution; lane 4, preparative gel-purified DBF (Prep); lane 5, heparin-Sepharose 0.5 M elution; lane 6, preparative gel-purified DBF.

Protein sequence analysis.

Following the preparative gel shift and elution of protein described above, DBF was run on a 10% polyacrylamide gel containing SDS and visualized by Coomassie blue R-250 staining. Regions of the gel containing purified DBF were excised (approximately 200 pmol) and sequenced by the Keck Foundation at Yale University. The individual polypeptides were digested in situ with trypsin, and peptides were purified by high-pressure liquid chromatography (HPLC). Individual peptides were analyzed by liquid chromatography-mass spectroscopy, and the subsequent masses were used to search the OWL database by using SeQuest (44).

RNA isolation and analysis.

Total cell RNA was isolated using Trizol (Gibco BRL) at 2 and 7 h postinfection. Primer extension reactions using 10 μg of RNA and 50 fmol of a 32P-labeled β-galactosidase primer (5′-GTGTTCGAGGGGAAAATAGGTTGCGCGAG-3′) or a 32P-labeled VP16 primer (5′-TTAGAGGACCGGACGGACCTTAT-3′) were analyzed on 8% polyacrylamide gels containing 8 M urea as previously described (13). Expected product sizes were 90 nucleotides for UL38 and 65 nucleotides for VP16.

In vitro transcription.

Supercoiled plasmid DNA was prepared according to protocols provided by the manufacturer (Qiagen). All plasmids utilized the vector pGEM3. The construct consisting of the adenovirus major late promoter (Ad MLP) with a β-galactosidase reporter gene (Ad MLP/β-gal), used as a control, was a gift of T. Osborne. DNA quantitation was performed by UV absorption and confirmed by agarose gel electrophoresis. In vitro transcription reactions were performed and analyzed by primer extension using a β-galactosidase-specific primer as previously described (13, 18). For heat treatment experiments, nuclear extracts were heated to 47°C for 15 min prior to their use as described in elsewhere (30, 34). Recombinant human TATA binding protein (rhTBP) was purchased from Upstate Biotechnology, and human DNA-PK was purchased from Promega. Template and protein concentrations used are indicated in figure legends. Expected product sizes were 90 nucleotides for UL38 promoter transcripts and 81 nucleotides for the Ad MLP/β-gal transcript. For transcript abundance quantitation, a PhosphorImager (Molecular Dynamics) was used, and the resulting images were analyzed with IPLab Gel software.

Immunoblot (Western blot) analysis.

Fractions containing approximately equivalent amounts of DBF as estimated by gel shift activity were loaded onto either an SDS-containing 7% polyacrylamide gel for immunoblotting with an antibody specific to the catalytic-subunit of DNA-PK (DNA-PKcs) or an SDS-containing 10% polyacrylamide gel for immunoblotting with a Ku-specific antibody. After SDS-PAGE and transfer to nitrocellulose, Western blotting was performed by the enhanced chemiluminescence method (Amersham). Antibodies used included anti-DNA-PKcs (Ab145; a gift from C. Anderson, Brookhaven National Laboratories) at a dilution of 1:50,000 and anti-Ku p86 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) at a dilution of 1:2,000. Secondary antibodies were horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit for DNA-PKcs and horseradish peroxidase donkey anti-goat for Ku, both used at dilutions of 1:2,500.

UV cross-linking.

UV cross-linking experiments were performed as described previously except that affinity-purified DBF was used (13). For competition experiments, both competitor DNA and probe were added concurrently.

Missing-contact footprinting.

Oligonucleotides corresponding to either the upper or lower strand of DAS (13) were end labeled with [γ-32P]ATP prior to annealing with the complementary strand. These single-end-labeled probes were subjected to limited modification at adenine and guanine residues with formic acid and at thymine and cytosine residues with hydrazine (26). This probe was subsequently used in a gel shift reaction with purified DBF. After electrophoresis on a 4% polyacrylamide gel, regions of the gel corresponding to the DBF-DAS complex and DAS alone were isolated, electroeluted, and subjected to piperidine cleavage. Cleavage products were resolved on a 12% polyacrylamide gel containing 8 M urea.

RESULTS

DBF is a cellular protein distinct from TFIID.

As described in the introduction, we have previously characterized three regulatory elements within the HSV-1 UL38 promoter: the TATA box, an Inr element, and DAS, the downstream regulatory sequence which is located between +20 and +33 relative to the transcription initiation site. Mutations of specific bases within DAS reduce transcription to less than 10% of wild-type levels as assayed by recombinant virus infection in vivo or by in vitro transcription reactions using uninfected HeLa cell nuclear extracts. We previously identified DBF, a cellular protein or complex of proteins found in both uninfected and infected cell nuclear extracts that specifically binds to DAS as measured by competitive gel shift assays (13).

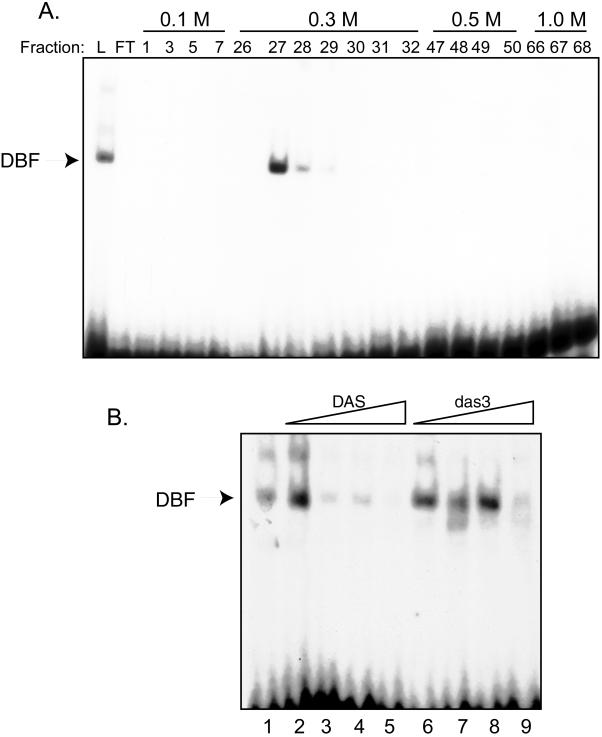

Several downstream elements which do not have sequence similarity to DAS have been shown to interact with components of TFIID through footprinting experiments (1, 2, 30, 35, 45). Accordingly, we initially suspected that TFIID might be interacting with DAS. We fractionated HeLa nuclear extracts by P11 phosphocellulose chromatography, which separates basal transcription factors into distinct fractions with TFIID eluting at 1.0 M KCl (5). Fractions generated during this purification step were assayed by gel shift analysis for the ability to bind to DAS. As shown in Fig. 1A, the 0.3 M KCl fraction contains protein which forms the characteristic DAS-DBF gel shift complex when incubated with labeled DAS probe.

FIG. 1.

Detection in the 0.3 M P11 phosphocellulose fraction of a specific DAS-DBF complex which is distinct from TFIID and other basal transcription factors. (A) Gel shift analysis of HeLa nuclear extracts fractionated by P11 phosphocellulose. HeLa nuclear extracts were fractionated on a P11 phosphocellulose column, and aliquots (1 to 2 μl) of the resulting fractions were subjected to gel shift analysis using 0.5 ng of 32P-labeled DAS probe and 250 ng of poly(dI-dC) per reaction. Reaction conditions were as described in reference 13. Only fractions containing protein were analyzed. Abbreviations: L, load; FT, flow through (material which did not bind to the column). (B) Competitive gel shift analysis with the 0.3 M KCl P11 phosphocellulose fraction. Both competitor (unlabeled DNA corresponding to either wild-type DAS or the das3 mutation) and probe were added concurrently. Amounts of competitor used: lane 1, none; lane 2, 10× DAS; lane 3, 50× DAS; lane 4, 100× DAS; lane 5, 200× DAS; lane 6, 10× das3; lane 7, 50× das3; lane 8, 100× das3; lane 9, 200× das3.

The addition of increasing amounts of unlabeled DAS DNA efficiently reduced the amount of labeled probe in the DNA binding species. In contrast, competition was characteristically inefficient with the addition of unlabeled das3 DNA (Fig. 1B; compare lane 3 to lane 6 and lane 4 to lane 7). The das3 sequence has the DAS core mutated from GAGCGGTAG to GAATAATAG. A major reduction of the DBF-DAS complex by competition with the das3 sequence was seen only at levels of competitor 200-fold greater than the amount of DAS probe (lane 9). This result was consistently observed and is consistent with the ability of das3 to partially substitute for wild-type sequences.

Even though a form of TFIID (B-TFIID) not responsive to transcriptional activators has been shown to elute with 0.3 M KCl, it is unable to bind to a basal promoter such as the Ad MLP directly (40). Also, we detected TBP by Western blot analysis only in our 1.0 M elution (data not shown). From this, we concluded that the protein that we detected in our gel shifts was not a component of holo-TFIID.

Purification and identification of DBF as DNA-PK.

We next proceeded to purify the protein(s) comprising DBF via the chromatographic steps shown in Fig. 2A. The presence of DBF in the appropriate fraction was confirmed at each step by using the same competitive DNA gel shift assays with DAS and das3 DNA sequences shown in Fig. 1B.

As a final purification step, we performed a preparative gel shift (Fig. 2B) followed by electroelution, precipitation, and SDS-PAGE on 12% gels. As shown in Fig. 2C, two prominent bands of about 70 and 86 kDa were obtained on the protein gel. A band of about 33 kDa also copurified with DBF, but this protein appeared to be nonspecific since it was also found in control preparative gels run without DAS DNA.

The 70- and 86-kDa proteins were individually excised from protein gels and digested in situ with trypsin. The peptides of each protein were individually purified by HPLC and analyzed by mass spectroscopy by workers at the Keck Foundation (data not shown). The resulting peptide masses were used to search a protein database. The 70-kDa protein was identified as the 70-kDa subunit and the 86-kDa protein was identified as the 86-kDa subunit of Ku, which comprise the DNA binding component of DNA-dependent protein kinase (DNA-PK).

DNA-PK is made up of three proteins, the 70- and 86-kDa subunits of Ku and the 350-kDa DNA-PKcs (6). To confirm the identification of DBF as DNA-PK, we performed Western blotting on various active fractions of the purification route, using antibodies against Ku and the 350-kDa catalytic subunit; some representative data are shown in Fig. 2D. The DAS-binding fraction from phosphocellulose, Q Sepharose, heparin-Sepharose, and preparative gel shift all reacted with both antibodies (only the heparin-Sepharose and preparative gel shift fractions are shown for the immunoblot analysis using the antibody against the DNA-PKcs). This result suggested that it is the entire DNA-PK protein complex that is functionally equivalent to DBF.

Addition of either gel-purified DBF or DNA-PK to HeLa nuclear extracts specifically increases transcription from UL38.

Since DAS functions in the context of the UL38 promoter when analyzed by in vitro transcription with uninfected cell nuclear extracts, we performed a series of in vitro transcription experiments to confirm the identification of DNA-PK as DBF and to begin a characterization of its mode of action. We took advantage of the observation of Nakajima et al. (30) that heat treatment of nuclear extracts causes the dissociation of TFIID through the denaturation of TBP to investigate the role of DBF and DAS in the initiation of transcription.

In vitro transcription reactions were performed with extracts that had been either untreated or heated to 47°C for 15 min (Fig. 3A). We confirmed that the addition of rhTBP to heat-treated HeLa cell extracts was able to fully restore transcription from the Ad MLP, which does not contain a downstream element similar to DAS.

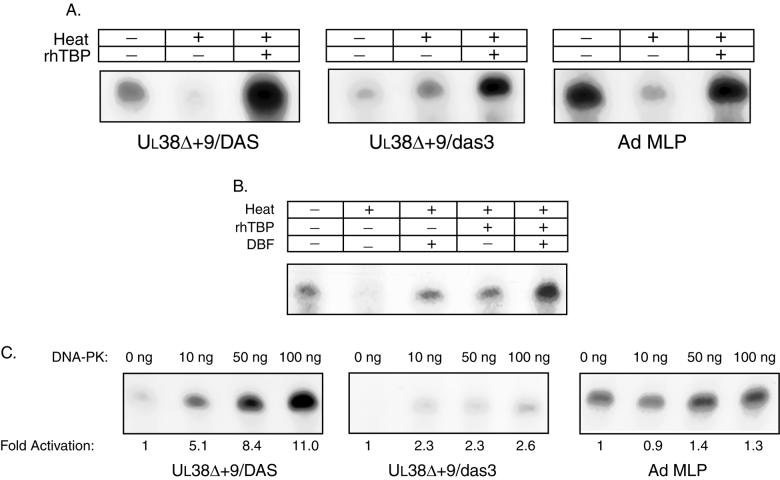

FIG. 3.

Transcriptional activation of UL38 by DNA-PK. (A) Addition of rhTBP to heat-treated nuclear extracts is able to restore transcription from UL38 promoters containing either a wild-type or mutated DAS. Supercoiled DNA templates (500 ng) containing either UL38Δ+9/DAS, UL38Δ+9/das3, or Ad MLP/β-gal were subjected to in vitro transcription using either untreated nuclear extracts, nuclear extracts that were heated to 47°C for 15 min prior to use, or heated extracts supplemented with 100 ng of TBP. The resulting transcripts were analyzed by primer extension using a β-galactosidase-specific primer. (B) Addition of rhTBP and affinity-purified DBF to heat-treated nuclear extracts is able to stimulate UL38Δ+9/DAS transcription. In vitro transcription reactions (100 ng of UL38Δ+9/DAS) were performed to compare untreated nuclear extracts to heat-treated nuclear extracts that were supplemented with either native eluted DBF alone, TBP alone, or DBF and TBP. The TBP-supplemented reactions used 25 ng of recombinant TBP. The DBF-supplemented reactions contained approximately 100 nmol of affinity-purified DBF which had been dialyzed against D buffer. (C) Addition of exogenous DNA-PK to nuclear extracts is able to specifically stimulate transcription from UL38. In vitro transcription reactions were performed with HeLa nuclear extracts and 100 ng of the indicated templates. Prior to the addition of nucleoside triphosphates, increasing amounts of purified DNA-PK were added. Fold activation was determined by measuring the amount of transcript by PhosphorImager analysis, and these values were normalized against those for the corresponding Ad MLP reaction containing the same amount of DNA-PK.

Transcription from UL38Δ+9/DAS was almost completely abolished by heat treatment, but the addition of 100 ng of rhTBP increased transcription in the heated extracts to above the levels seen with untreated extract. In other experiments not shown, lesser amounts of rhTBP stimulated the reaction to a lesser extent; addition of 25 ng stimulated the reaction to levels essentially equivalent to those seen in untreated extracts.

Transcription from UL38Δ+9/das3, containing a mutation within DAS which reduces promoter activity to less than 10% of wild-type activity (13), was inactive in the complete system, and heat treatment had little effect on the transcript levels detected. Interestingly, addition of rhTBP increased transcription to 30 to 50% of the augmented levels seen with the DAS-containing promoter under the same conditions and as much as twofold higher than the levels seen with this promoter with untreated extracts. These results suggest that the high levels of TBP may partially obviate the requirement for DAS in the stabilization of a preinitiation transcription complex.

We then used the same heat-treated extracts to show that addition of DBF purified by preparative gel shift was able to stimulate transcription from UL38Δ+9/DAS (Fig. 3B). For these experiments, preparative gel-purified DBF was eluted under nondenaturing conditions and concentrated by chromatography and ultrafiltration. As shown in Fig. 3B, the addition of gel-purified DBF to heat-treated nuclear extracts was able to increase transcription to approximately the same level as heated extracts supplemented with limiting amounts of TBP (25 ng). The addition of both TBP and DBF stimulated transcription above the level of untreated extracts. This result is consistent with our interpretation of the experiment of Fig. 3A, which is that the function of DAS and its interacting protein may be to stabilize the binding of the preinitiation transcription complex.

We next performed a titration experiment in which increasing amounts of purified DNA-PK were added to in vitro transcription reaction mixtures. Figure 3C shows the results of a representative experiment in which UL38Δ+9/DAS and UL38Δ+9/das3 were tested with Ad MLP/β-gal as a control. Transcript abundance increased with increasing amounts of DNA-PK for UL38Δ+9/DAS. This stimulation was not observed with UL38Δ+9/das3, and only a slight increase in transcription was seen for the Ad MLP/β-gal.

A cis-acting element that specifically binds Ku is able to functionally substitute for DAS both in in vitro transcription and in recombinant virus infection of tissue culture cells.

The above results are fully consistent with our conclusion that DBF is identical to intact DNA-PK or the DNA binding portion of DNA-PK. This interpretation was complicated, however, by observations from other laboratories that the DNA-binding heterodimer of this protein can nonspecifically bind to the ends of DNA or at DNA nicks (11). Although our transcription assays were carried out using small, supercoiled DNA templates, it was still possible that the primary effect of added DNA-PK was through the binding to nicked DNA template followed by nonspecific stimulation of the formation of the preinitiation complex through phosphorylation of transcription factors. This effect could be more pronounced for promoters with the functional architecture of the HSV-1 UL38 and related promoters but could also explain the slight activation of transcription seen with the addition of DNA-PK to in vitro transcription reactions using the Ad MLP.

We investigated this possibility by generating a recombinant virus in which a DNA binding sequence known to interact with Ku was substituted for DAS in the UL38 promoter, and its effect on transcription during productive infection of cultured cells was assayed. We chose NRE1 of the glucocorticoid-responsive mouse mammary tumor virus long terminal repeat, which is able to repress glucocorticoid-induced transcription through the direct binding of Ku (27). While the location of NRE1 (−394 to −381) differs from that of DAS (+20 to +33), there is some sequence similarity (GAGCGGTAG for DAS; GAGAAAGAG for NRE1).

We constructed a chimeric UL38 promoter in which the NRE1 sequence was inserted in place of DAS between positions +20 and +33; the structure of this promoter, UL38Δ+9/NRE1, is shown in Fig. 4A along with those for UL38Δ+9/DAS and UL38Δ+9/das3 promoters. We carried out in vitro transcription reactions to compare this promoter with the other two UL38-based promoters, and typical data such as those shown in Fig. 4B demonstrate that this element is able to substitute for DAS in in vitro transcription.

We then generated a recombinant virus in which the UL38Δ+9/NRE1 promoter controlling expression of the bacterial β-galactosidase gene was inserted into the nonessential gC locus. As described in numerous publications, this is our standard location for the analysis of the effect of defined modifications of promoters of interest, and insertion of wild-type promoters into this region results in their being expressed with kinetics and levels identical to those of their wild-type counterparts (10, 14, 17). Structures of the current recombinant and control viruses are shown in Fig. 4C.

Replicate cultures of Vero cells were infected individually with the viruses of interest; total RNA was extracted at 2 or 7 h postinfection and subjected to primer extension analysis. A representative experiment is shown in Fig. 4D. It is evident that substitution of NRE1 for DAS does not change the kinetics of expression, although transcript levels are slightly above wild-type levels, an effect similar to that seen in in vitro transcription.

The core bases conserved between NRE1 and DAS are important in the in vitro binding of Ku to DAS.

The ability of NRE1 to functionally substitute for DAS while the das3 mutation cannot suggests that the bases conserved between DAS and NRE1 are important in the functional binding of DBF (DNA-PK) to the UL38 promoter. To determine if the bases identified as critical for the function of DAS in transcription are also important in the binding of Ku to DAS, we performed missing-contact footprinting with partially purified DNA-PK.

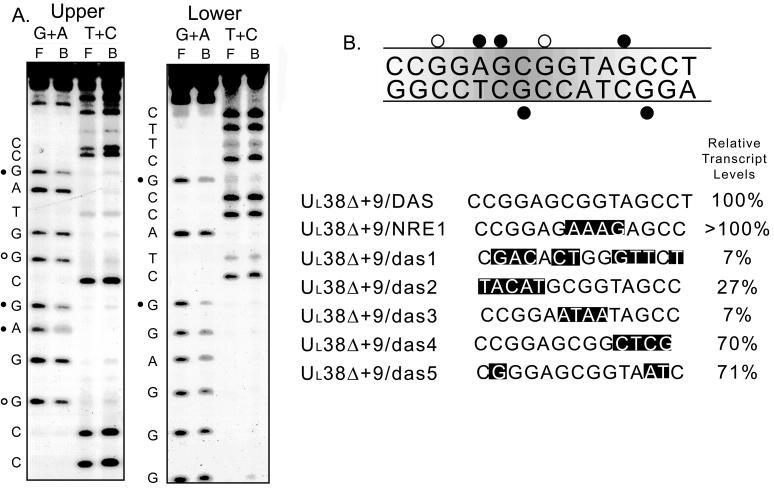

As shown in Fig. 5A, several bases found on both the upper and lower strands are important in the in vitro binding of DNA-PK within the DAS core. Figure 5B summarizes these results and also tabulates the base changes previously shown to have a role in transcription by site-directed mutagenesis (13). The bases important in the binding of DAS (most notably the guanine residue at +25) as measured by in vitro binding of DNA-PK are also important in the transcriptional activation mediated by DAS in recombinant virus infection of tissue culture cells.

FIG. 5.

Missing-contact footprinting of DAS with affinity-purified DBF (DNA-PK). (A) Single-end-labeled probes, Upper (sense) or Lower (antisense), were modified under limiting conditions with either formic acid (G+A reaction) or hydrazine (T+C reaction) and used in a gel shift reaction. Regions of the gel corresponding to DBF-bound (B) DAS or free (F) DAS probe were isolated, cleaved with piperidine, and analyzed on a 12% sequencing gel. Bases which when modified are unable to support the binding of DNA-PK (•) and bases which when modified show some reduction in DNA-PK binding (○) are indicated. (B) Summary of missing-contact data from panel A. Mutations within DAS which have been shown to influence UL38 transcription in recombinant virus infections of tissue culture cells are also shown.

The 70-kDa subunit of Ku binds to DAS.

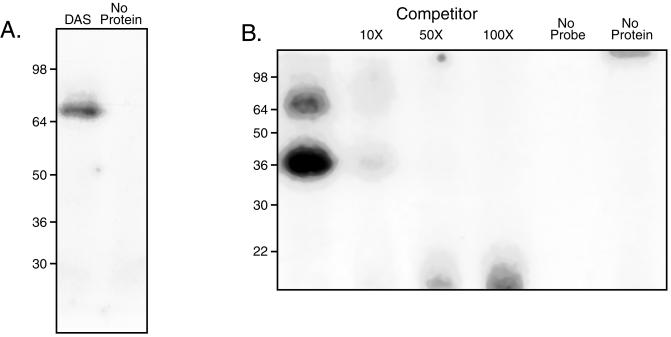

While the size of the holo-DNA-PKcs precluded its inclusion on the SDS-containing polyacrylamide gels used to characterize DBF, both subunits of the DNA-binding Ku heterodimer were routinely purified in approximately equal concentrations (Fig. 2C). UV cross-linking experiments were performed with DAS-affinity purified DBF (DNA-PK) to elucidate which subunit is involved in the binding to DAS. As shown in Fig. 6A, a band corresponding to the 70-kDa subunit is apparent which represents the 70-kDa subunit of Ku. This binding appears to be dynamic since competition with even small amounts of unlabeled DAS DNA (Fig. 6B) is able to efficiently reduce the amount of cross-linked protein.

FIG. 6.

The 70-kDa subunit of Ku binds to DAS and binds in a reversible manner. (A) UV cross-linking of affinity-purified DBF to DAS. The sizes of molecular mass markers are indicated in kilodaltons. (B) The binding of Ku p70 to DAS is reversible. DAS affinity-purified DNA-PK was subjected to UV cross-linking in the presence of increasing amounts of unlabeled DAS DNA. Competitor was added concurrently with labeled DAS probe (1 ng). As described in the text, the lower band (approximately 35 kDa) is a breakdown product of the 70-kDa subunit of Ku.

While our demonstration that DBF is DNA-PK reported in this communication is consistent with most of the results of our earlier studies on the UL38 promoter, DAS, and DBF, there is one inconsistency. We previously reported UV cross-linking studies with unfractionated extracts which suggested that the DNA binding component of DBF was a 35-kDa cellular protein, in contrast to our present conclusion that the 70-kDa subunit of Ku fills this role (13). In an attempt to reconcile these observations, we investigated the role of the age of the extract on the size of product bound in the cross-linking studies. We consistently found that repeated freeze-thawing of preparative gel-purified DNA-PK resulted in this 35-kDa band being present (Fig. 6B). The relative amount of this band increased markedly when nuclear extracts that had been stored at −70°C for relatively long periods of time were used. We interpret these observations as reflecting the initial breakdown product of the 70-kDa subunit of Ku; it should be noted that the binding of this product is also specific for DAS since increasing amounts of unlabeled DAS oligonucleotide efficiently reduces the amount of radioactivity in the cross-linked product.

DISCUSSION

The strict late UL38 promoter is tripartite: a TATA box at −31, a consensus Inr element, and DAS at +20 to +33 are all required for wild-type transcription levels. Because of its unique position and its apparent conservation in several other strict late HSV-1 promoters, DAS appears to be an important feature in a class of late promoters. Here, we sought to further characterize the interaction between DAS and cellular proteins that we previously reported and collectively termed DBF. Again, we have previously shown that the sequence-specific binding of DBF to DAS targets the same nucleotides that were shown to be critical in transcriptional activation by specific mutagenesis (13).

Identification of DBF as DNA-PK, not a component of TFIID.

We initially speculated that DAS might interact directly with TFIID through the binding of one or another of the TBP-associated factors (TAFs). This idea was based on the position of DAS vis-à-vis the transcript start site since the TFIID complex has been shown to footprint to about +30 on several promoters (35, 45). The possibility of a direct interaction was also suggested by the existence of several Drosophila TATA-less promoters that contain a conserved downstream promoter element (DPE) situated similarly to DAS (1, 2). DPE is known to interact with several Drosophila TAFs, including dTAFII60; however, its sequence bears little resemblance to that of UL38 DAS (DPE core sequence, [G/A]G[A/T]CGTG; DAS core sequence, GAGCGGTAG).

Despite these examples, which provide ample precedence for transcriptional activation through TFIID interacting with sequences downstream of the transcription start site, data reported here show that DBF is not a component of TFIID or a basal transcription factor; rather, it is DNA-PK. Initially, we fractionated HeLa nuclear extracts by P11 phosphocellulose chromatography (Fig. 1), which is the standard approach for separation of the basal transcription factors into distinct fractions (5). DBF activity consistently fractionated at 0.3 M KCl (5).

Once it was established that DBF was a protein distinct from basal transcription factors, we proceeded to purify it by using conventional chromatography and DAS DNA affinity techniques. Our final conclusion that DBF was DNA-PK is based both on the tryptic peptide mapping of purified DBF, which identified the DNA binding component of DNA-PK, also known as Ku, and the demonstration that antibodies to DNA-PK specifically reacted with DBF.

For the purification of DBF, which is outlined in Fig. 2, we used a competitive gel shift assay (Fig. 1). For our choice of competitor in such assays, we utilized the observations that the UL38 promoter containing the das3 mutation converting (−18)CCGGAGCGGTAGCC(−31) to (−18)CCGGAATAATAGCC(−31) is approximately 10-fold less active in transcription than the wild type. Also, DNA containing the das3 mutation is unable to efficiently compete for protein bound to DAS in gel shift experiments.

DNA-PK is able to stimulate UL38 transcription in vitro and in vivo.

Ku has frequently been misidentified as a sequence-specific DNA binding protein (8, 28, 36) due to its high affinity for DNA ends and its ability to translocate DNA to internal pause sites (21). As shown in Fig. 1 and 6, the binding of Ku to UL38Δ+9/DAS is dynamic in that the addition of increasing amounts of unlabeled identical sequence reduces the detectable DNA-protein complex even in the presence of a large (5,000-fold) excess of nonspecific DNA. Also, the results of the missing-contact footprinting experiment shown in Fig. 5 demonstrate base-specific contacts by Ku which correlate with our previously reported transcription data (13).

The data reported here clearly show that DNA-PK specifically activates transcription from the UL38 promoter through effects mediated by DAS. Our experiments using supercoiled DNA templates in in vitro transcription reactions demonstrate that the addition of DNA-PK to both heat-treated and untreated nuclear extracts leads to an increase in the amount of UL38 transcript produced. As expected of a transcriptional activator (shown in Fig. 3), the addition of increasing amounts of DNA-PK leads to an increase in the amount of transcript produced. This activation is dependent on the presence of DAS, as the promoter containing the das3 mutation and another promoter which lacks DAS (the Ad MLP) do not show similar responses to the addition of DNA-PK (Fig. 3C).

The specificity of transcriptional activation by DNA-PK was confirmed by studies of modified UL38 promoters in vivo. The glucocorticoid-responsive mouse mammary tumor virus long terminal repeat contains an upstream cis-acting element, NRE1, that has significant sequence similarity to DAS and is able to repress transcription under glucocorticoid induction (27). Experiments using closed circular DNA containing NRE1 demonstrated that Ku directly binds to this element (9). As shown in Fig. 4, NRE1 efficiently substitutes for DAS in the UL38 promoter in the context of the viral genome.

Models for DNA-PK-mediated transcriptional activation of UL38.

DNA-PK has a myriad of defined cellular functions including roles in DNA repair, cell cycle regulation, recombination, and transcription (21). Its role in the regulation of transcription occurs at several levels. Upon activation, which requires the binding of Ku to DNA, DNA-PK is autophosphorylated, leading to the dissociation of DNA-PKcs from Ku. The catalytic subunit is subsequently able to phosphorylate target proteins, including a wide range of transcription factors such as Sp1 and p53, to modulate their activity (19, 38). After this activation event, Ku remains bound to DNA to either interact with other DNA-PKcs molecules or serve other functions. For example, it is known to be associated with an RNA polymerase II complex and may be involved in recruiting the polymerase to initiate transcription (23). In addition to DNA binding, the 70-kDa subunit of Ku has a helicase activity, and the localized unwinding of DNA in an ATP-dependent manner could assist in the initiation of transcription (32).

Based on the experimental evidence that we have presented, several nonexclusive models for the role of DNA-PK in activation of DAS-containing HSV promoters can be proposed: (i) direct recognition of DAS by Ku could lead to the localized unwinding of DNA, which facilitates the initiation of transcription through the activity of the 70-kDa subunit of Ku; (ii) direct recognition of DAS by Ku could stabilize the binding of basal transcription factors such as TFIID through protein-protein interactions; and (iii) the phosphorylation of cellular transcription machinery and transcription factor(s) by DNA-PK could activate UL38 transcription. Although our results most strongly support the first two models, we cannot exclude the possibility that one transcriptional effect of DNA-PK is through a phosphorylation event. We do not favor this model because of experimental observations of others that phosphorylation by DNA-PK inhibits the effects of transcription factors (21).

Whatever the exact role of DNA-PK in late HSV transcription, it is significant that this cellular protein is modified during HSV infection of tissue culture cells. The kinase activity and abundance of DNA-PKcs are both greatly reduced during productive infection through effects mediated by ICP0 prior to viral DNA replication, while the levels of Ku remain constant (22). This role could be related to the localization of ICP0 to discrete nuclear structures (ND10) early, the dispersal of which occurs at about the same time as the downregulation of DNA-PK activity. Such an early localization could potentially influence the timing of this immediate-early protein in its function of augmenting late transcription. Further study to clarify the importance of these observations in the HSV-1 replication cycle are clearly needed.

While it is tempting to speculate that the loss of DNA-PKcs activity is important in the switch from early to late gene expression, our in vitro transcription experiments using uninfected nuclear extracts and our experiments adding exogenous DNA-PK to nuclear extracts suggest that the presence of the entire protein complex activates transcription. This observation may be related to the fact that ICP0 in the HSV life cycle is not absolutely required, but can be obviated by a high multiplicity infection and under certain conditions of cellular growth (3). We are currently exploring whether the Ku portion of the DNA-PK heterodimer alone is able to support the transcriptional activation of UL38.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Carl Anderson for anti-DNA-PKcs antisera, Tim Osborne for the Ad MLP, the National Cell Culture Center for HeLa S3 spinner cultures, and the Keck Foundation at Yale University for protein analysis. We are also grateful for the technical assistance provided by Marcia Rice and Matt Solley and for the assistance of Mary Bennett in protein purification. We also thank John Guzowski for discussions and Tim Osborne, John Rosenfeld, and Martin Hoyt for the critical reading of the manuscript.

This research was supported by NIH grant CA11861 to E.K.W. Further support was provided by NIH predoctoral training grant 5 T32 AI 07319 to M.D.P.

REFERENCES

- 1.Burke T W, Kadonaga J T. Drosophila TFIID binds to a conserved downstream basal promoter element that is present in many TATA-box-deficient promoters. Genes Dev. 1997;10:711–724. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.6.711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Burke T W, Kadonaga J T. The downstream core promoter element, DPE, is conserved from Drosophila to humans, and is recognized by TAFII60 of Drosophila. Genes Dev. 1997;11:3020–3031. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.22.3020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cai W, Schaffer P A. Herpes simplex virus type 1 ICP0 regulates expression of immediate-early, early, and late genes in productively infected cells. J Virol. 1992;66:2904–2915. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.5.2904-2915.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.DeLuca N A, Carrozza M J. Interaction of the viral activator protein ICP4 with TFIID and through TAF250. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:3085–3093. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.6.3085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dignam J D, Martin P L, Shastry B S, Roeder R G. Eukaryotic gene transcription with purified components. Methods Enzymol. 1983;101:582–598. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(83)01039-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dvir A, Stein L Y, Calore B L, Dynan W S. Purification and characterization of a template-associated protein kinase that phosphorylates RNA polymerase II. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:10440–10447. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gander I, Foeckler R, Rogge L, Meisterernst M, Schneider R, Mertz R, Lottspeich F, Winnacker E L. Purification methods for the sequence-specific DNA-binding protein nuclear factor I (NFI)—generation of protein sequence information. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1988;951:411–418. doi: 10.1016/0167-4781(88)90114-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Genersch E, Eckerskorn C, Lottspeich F, Herzog C, Kuhn K, Poschl E. Purification of the sequence-specific transcription factor CTCBF, involved in the control of human collagen IV genes: subunits with homology to Ku antigen. EMBO J. 1995;14:791–800. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb07057.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Giffin W, Torrance H, Rodda D J, Prefontaine G G, Pope L, Hache R J. Sequence-specific DNA binding by Ku autoantigen and its effects on transcription. Nature. 1996;380:265–268. doi: 10.1038/380265a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goodart S A, Guzowski J F, Rice M K, Wagner E K. Effect of genomic location on expression of β-galactosidase mRNA controlled by the herpes simplex virus type 1 UL38 promoter. J Virol. 1992;66:2973–2981. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.5.2973-2981.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gottlieb T M, Jackson S P. The DNA-dependent protein kinase: requirement for DNA ends and association with Ku antigen. Cell. 1993;72:131–142. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90057-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grazia Romanelli M, Mavromara-Nazos P, Spector D, Roizman B. Mutational analysis of the ICP4 binding sites in the 5′ transcribed noncoding domains of the herpes simplex virus 1 UL49.5 gamma 2 gene. J Virol. 1992;66:4855–4863. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.8.4855-4863.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guzowski J F, Singh J, Wagner E K. Transcriptional activation of the herpes simplex virus type 1 UL38 promoter conferred by the cis-acting downstream activation sequence is mediated by a cellular transcription factor. J Virol. 1994;68:7774–7789. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.12.7774-7789.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guzowski J F, Wagner E K. Mutational analysis of the herpes simplex virus type 1 strict late UL38 promoter/leader reveals two regions critical in transcriptional regulation. J Virol. 1993;67:5098–5108. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.9.5098-5108.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hardwicke M A, Sandri-Goldin R M. The herpes simplex virus regulatory protein ICP27 contributes to the decrease in cellular mRNA levels during infection. J Virol. 1994;68:4797–4810. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.8.4797-4810.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hardy W R, Sandri-Goldin R M. Herpes simplex virus inhibits host cell splicing, and regulatory protein ICP27 is required for this effect. J Virol. 1994;68:7790–7799. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.12.7790-7799.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huang C-J, Goodart S A, Rice M K, Guzowski J F, Wagner E K. Mutational analysis of sequences downstream of the TATA box of the herpes simplex virus type 1 major capsid protein (VP5/UL19) promoter. J Virol. 1993;67:5109–5116. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.9.5109-5116.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huang C J, Petroski M D, Pande N T, Rice M K, Wagner E K. The herpes simplex virus type 1 VP5 promoter contains a cis-acting element near the cap site which interacts with a cellular protein. J Virol. 1996;70:1898–1904. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.3.1898-1904.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jackson S P, MacDonald J J, Lees-Miller S, Tjian R. GC box binding induces phosphorylation of Sp1 by a DNA-dependent protein kinase. Cell. 1990;63:155–165. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90296-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kibler P K, Duncan J, Keith B D, Hupel T, Smiley J R. Regulation of herpes simplex virus true late gene expression: sequences downstream from the US11 TATA box inhibit expression from an unreplicated template. J Virol. 1991;65:6749–6760. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.12.6749-6760.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lees-Miller S P. The DNA-dependent protein kinase, DNA-PK: 10 years and no ends in sight. Biochem Cell Biol. 1996;74:503–512. doi: 10.1139/o96-054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lees-Miller S P, Long M C, Kilvert M A, Lam V, Rice S A, Spencer C A. Attenuation of DNA-dependent protein kinase activity and its catalytic subunit by the herpes simplex virus type 1 transactivator ICP0. J Virol. 1996;70:7471–7477. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.11.7471-7477.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maldonado E, Shiekhattar R, Sheldon M, Cho H, Drapkin R, Rickert P, Lees E, Anderson C W, Linn S, Reinberg D. A human RNA polymerase II complex associated with SRB and DNA-repair proteins. Nature. 1996;381:86–89. doi: 10.1038/381086a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maul G G, Guldner H H, Spivack J G. Modification of discrete nuclear domains induced by herpes simplex virus type 1 immediate early gene 1 product (ICP0) J Gen Virol. 1993;74:2679–2690. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-74-12-2679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maul G G, Ishov A M, Everett R D. Nuclear domain 10 as preexisting potential replication start sites of herpes simplex virus type-1. Virology. 1996;217:67–75. doi: 10.1006/viro.1996.0094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Maxam A M, Gilbert W. Sequencing end-labeled DNA with base-specific chemical cleavages. Methods Enzymol. 1980;65:499–560. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(80)65059-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mink S, Ponta H, Cato A C. The long terminal repeat region of the mouse mammary tumour virus contains multiple regulatory elements. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;18:2017–2024. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.8.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mitsis P G, Wensink P C. Identification of yolk protein factor 1, a sequence-specific DNA-binding protein from Drosophila melanogaster. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:5188–5194. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mullen M-A, Gerstberger S, Ciufo D M, Mosca J D, Hayward G S. Evaluation of colocalization interactions between the IE110, IE175, and IE63 transactivator proteins of herpes simplex virus within subcellular punctate structures. J Virol. 1995;69:476–491. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.1.476-491.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nakajima N, Horikoshi M, Roeder R G. Factors involved in specific transcription by mammalian RNA polymerase II: purification, genetic specificity, and TATA box-promoter interactions of TFIID. Mol Cell Biol. 1988;8:4028–4040. doi: 10.1128/mcb.8.10.4028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nakatani Y, Brenner M, Freese E. An RNA polymerase II promoter containing sequences upstream and downstream from the RNA startpoint that direct initiation of transcription from the same site. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:4289–4293. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.11.4289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ochem A E, Skopac D, Costa M, Rabilloud T, Vuillard L, Simoncsits A, Giacca M, Falaschi A. Functional properties of the separate subunits of human DNA helicase II/Ku autoantigen. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:29919–29926. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.47.29919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pal S K, Zinkel S S, Kiessling A A, Cooper G M. c-mos expression in mouse oocytes is controlled by initiator-related sequences immediately downstream of the transcription initiation site. Mol Cell Biol. 1991;11:5190–5196. doi: 10.1128/mcb.11.10.5190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pugh B F, Tjian R. Transcription from a TATA-less promoter requires a multisubunit TFIID complex. Genes Dev. 1991;5:1935–1945. doi: 10.1101/gad.5.11.1935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Purnell B A, Gilmour D S. Contribution of sequences downstream of the TATA element to a protein-DNA complex containing the TATA-binding protein. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:2593–2603. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.4.2593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Roberts M R, Han Y, Fienberg A, Hunihan L, Ruddle F H. A DNA-binding activity, TRAC, specific for the TRA element of the transferrin receptor gene copurifies with the Ku autoantigen. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:6354–6358. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.14.6354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sandri-Goldin R M, Mendoza G E. A herpesvirus regulatory protein appears to act post-transcriptionally by affecting mRNA processing. Genes Dev. 1992;6:848–863. doi: 10.1101/gad.6.5.848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shieh S Y, Ikeda M, Taya Y, Prives C. DNA damage-induced phosphorylation of p53 alleviates inhibition by MDM2. Cell. 1997;91:325–334. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80416-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Singh J, Wagner E K. Herpes simplex virus recombination vectors designed to allow insertion of modified promoters into transcriptionally “neutral” segments of the viral genome. Virus Genes. 1995;10:127–136. doi: 10.1007/BF01702593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Timmers H T, Sharp P A. The mammalian TFIID protein is present in two functionally distinct complexes. Genes Dev. 1991;5:1946–1956. doi: 10.1101/gad.5.11.1946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wagner E K, Guzowski J F, Singh J. Transcription of the herpes simplex virus genome during productive and latent infection. Prog Nucleic Acid Res Mol Biol. 1995;51:123–168. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6603(08)60878-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wagner, E. K., M. D. Petroski, N. T. Pande, P. Leiu, and M. K. Rice. Analysis of factors influencing the kinetics of herpes simplex virus transcript expression utilizing recombinant virus. Methods Companion Methods Enzymol., in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 43.Weir J P, Narayanan P R. Expression of the herpes simplex virus type 1 glycoprotein C gene requires sequences in the 5′ noncoding region of the gene. J Virol. 1990;64:445–449. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.1.445-449.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Williams K R, Stone K L. Enzymatic cleavage and HPLC peptide mapping of proteins. Mol Biotechnol. 1997;8:155–167. doi: 10.1007/BF02752260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhou Q, Lieberman P M, Boyer T G, Berk A J. Holo-TFIID supports transcriptional stimulation by diverse activators and from a TATA-less promoter. Genes Dev. 1992;6:1964–1974. doi: 10.1101/gad.6.10.1964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]