Abstract

Our study focused on human brain transcriptomes and the genetic risks of cigarettes per day (CPD) to investigate the neurogenetic mechanisms of individual variation in nicotine use severity. We constructed whole-brain and intramodular region-specific coexpression networks using BrainSpan’s transcriptomes, and the genomewide association studies identified risk variants of CPD, confirmed the associations between CPD and each gene set in the region-specific subnetworks using an independent dataset, and conducted bioinformatic analyses. Eight brain-region-specific coexpression subnetworks were identified in association with CPD: amygdala, hippocampus, medial prefrontal cortex (MPFC), orbitofrontal cortex (OPFC), dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, striatum, mediodorsal nucleus of the thalamus (MDTHAL), and primary motor cortex (M1C). Each gene set in the eight subnetworks was associated with CPD. We also identified three hub proteins encoded by GRIN2A in the amygdala, PMCA2 in the hippocampus, MPFC, OPFC, striatum, and MDTHAL, and SV2B in M1C. Intriguingly, the pancreatic secretion pathway appeared in all the significant protein interaction subnetworks, suggesting pleiotropic effects between cigarette smoking and pancreatic diseases. The three hub proteins and genes are implicated in stress response, drug memory, calcium homeostasis, and inhibitory control. These findings provide novel evidence of the neurogenetic underpinnings of smoking severity.

Keywords: Brain transcriptome, coexpression network, cigarettes per day, GRIN2A, PMCA2, SV2B

1. Introduction

Cigarette smoking is detrimental to health and, according to a 2021 World Health Organization report, leads to over eight million deaths worldwide each year (World Health Organization, 2021). While many genetic variants of smoking-related traits have been identified through genome-wide association studies (GWAS) (Liu et al., 2019), little is known about the neural pathways underlying the impact of genetic variants on smoking-related behaviors. Since nicotine addiction is a chronic brain disease (Leshner, 1997), we aim to answer the following questions: are these GWAS-identified variants, as expressed in neural circuits, implicated in the dysfunctional psychological processes of smoking, or why do some people smoke more?

The human brain is organized into functional networks, in which different brain regions respond in a coordinated way to cognitive challenges (Fox et al., 2005). Specific gene products can perturb the neural networks, reshaping brain activity and potentially disposing individuals to mental illness (Iyer et al., 2022). Risk genes may give rise to region-specific interacting proteins (Magger et al., 2012) in distinct neural networks as part of the etiology of neuropsychiatric illnesses (Goymer, 2008). Altered macromolecular interactions have been reported for human genetic disorders, with as many as two-thirds of missense mutations perturbing protein-protein interaction (PPI) networks (Sahni et al., 2015). Half of the missense mutations are “edgetic” alleles (Sahni et al., 2015) that disrupt specific PPIs. For instance, de novo missense variants that disrupt protein interactions are enriched in individuals with autism spectrum disorder, affecting hub proteins and their interactions (Chen et al., 2020). Genes identified of disrupted protein interactions are expressed early in development in excitatory and inhibitory neuronal lineages based on inferred gene coexpressions (Chen et al., 2020). Thus, in elucidating the functional profiles of cigarette smoking severity risk genes, it would be informative to investigate the coexpression patterns of the severity risk genes across brain networks and related gene products in PPIs. In the current study, we constructed coexpression networks using the BrainSpan transcriptome (Miller et al., 2014) and integrated the networks with the summary statistics of a GWAS on CPD to better understand the neurogenetic networks enriched by the effect strength of CPD-associated genes. The BrainSpan transcriptome broadly surveys gene expression in specific brain regions (Miller et al., 2014), allowing us to construct region-specific coexpression networks. Thus, by integrating each variant’s effect strength on CPD in the coexpression networks derived from brain transcriptomes, we could build region-specific subnetworks enriched for CPD. We obtained summary statistics on CPD from the U.K. Biobank (UKB) (GWAS analysis of the UK Biobank, 2018) and GWAS & Sequencing Consortium of Alcohol and Nicotine (GSCAN) (GSCAN, 2019). As the source of two of the largest GWAS on nicotine use, UKB (N=462,690) and GSCAN (N=337,334) have been employed to identify many novel loci of genome-wide significance for smoking behavior (Liu et al., 2019). We used CPD to quantify the severity of smoking. The BrainSpan transcriptome comprises mostly prenatal samples, thus mitigating the confounding effects of nicotine exposure on gene expression. This approach led us to identify genetically informed neurobiological mechanisms of nicotine use severity. In particular, addiction neuroscience has associated stress reactivity, impulse control dysfunction, and reward sensitivity with the etiological processes of substance misuse. Investigating which risk genes are implicated in these processes, whether they are expressed, and how their gene products are implicated in the brain networks that regulate behavioral phenotypes would help unravel the neurobiology of nicotine misuse.

2. Methods

2.1. Datasets

We used publicly available data for the current study. These data contain no personal identifiers or are aggregated. The research’s ethical review was approved for each individual study that ascertained the data.

2.1.1. U.K. Biobank’s GWAS summary statistics for CPD

Of the self-reported smoking measures in the UKB, CPD is accessible from data fields 3456 and 2887 for current and previous cigarette smokers, respectively. We obtained the summary statistics from a GWAS on CPD from the Neale Lab at the Broad Institute (GWAS analysis of the UK Biobank, 2018). The data were analyzed using linear regression of CPD on each genetic variant for individuals of European ancestry (N=128,434).

2.1.2. Confirmation of gene-set association for each subnetwork using GSCAN

We used an independent study from GSCAN to confirm the association of the resulting brain networks with CPD. GSCAN included 30 separate cohorts with smoking phenotypes for 1,232,091 participants, including the UKB samples. We chose the GWAS summary statistics for CPD, excluding the UKB samples (N=118,549) (GSCAN, 2019), to conduct gene-set association analyses (Liu et al., 2019). Henceforth, we use GSCAN to refer to GSCAN without the UKB’s samples. Detailed information about sample ascertainment and the analyses of GWAS on CPD has been reported previously (Liu et al., 2019).

2.1.3. BrainSpan’s transcriptome

We downloaded region-specific gene expression profiles from BrainSpan’s transcriptome data. The BrainSpan project used postmortem human brain specimens (Miller et al., 2014). We studied the transcriptomes of European descent (N=21) to correspond with the populations we considered from UKB and GSCAN. BrainSpan excluded postnatal specimens with excessive drug or alcohol exposure (BrainSpan).

We excluded the cerebellar cortex and other brain regions with ≤ five samples from the 26 brain regions and focused on 15 regions for analyses: the amygdala (AMY), hippocampus (HIP), striatum (STR), and mediodorsal nucleus of the thalamus (MDTHAL), as well as 11 neocortical regions: the primary auditory cortex (A1C), primary motor cortex (M1C), primary somatosensory cortex (S1C), primary visual cortex (V1C), dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC), medial prefrontal cortex (MPFC), orbitofrontal cortex (OPFC), ventrolateral prefrontal cortex (VLPFC), inferolateral temporal cortex (ITC), posterior superior temporal cortex (STC), and posteroinferior (ventral) parietal cortex (IPC). As the 15 regions covered nearly the entire brain, we termed this a “whole-brain” analysis henceforth.

The RNA sequencing data were consolidated into Gencode 10 gene-level Reads Per Kilobase of transcript per Million mapped reads (RPKM) values (Harrow et al., 2006). We only considered genes to be expressed if their normalized RPKM values were ≥0 in at least one brain region, at one time point, in 80% of samples. The expression values were log-transformed (log2[RPKM+1]) for the subsequent analyses. At last, 238 region-specific samples met the expression criteria and were used to construct the coexpression networks.

2.2. Analytical approaches

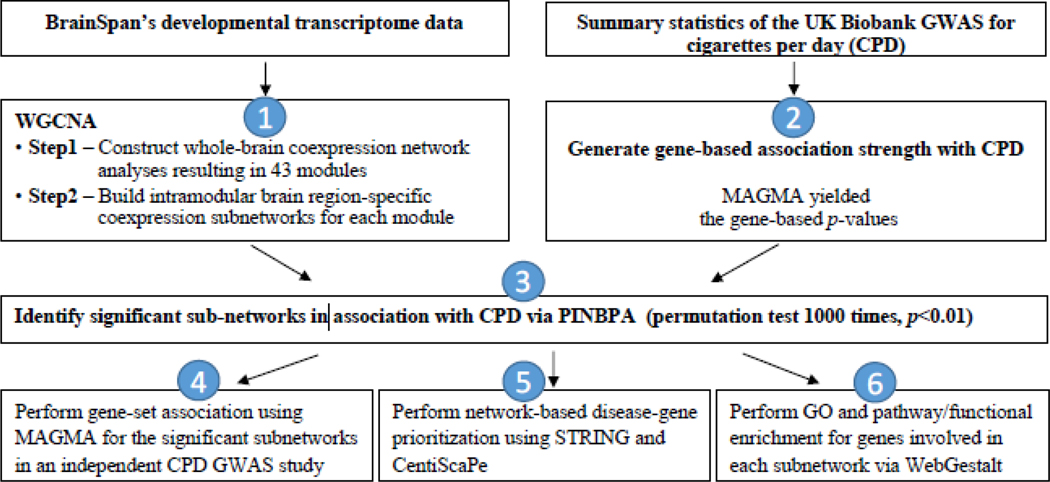

We conducted the following analyses, as summarized in Figure 1, to integrate the brain transcriptome and GWAS on CPD.

Figure 1. Workflow of the analytical approaches.

(1) BrainSpan’s transcriptome data from the 15 brain regions were used to construct the gene modules of the whole brain and build the intramodular-region-specific coexpression subnetworks in each of the 15 brain regions using WGCNA. (2) Summary statistics from the U.K. Biobank (UKB) GWAS for CPD were converted to gene-based results using MAGMA. (3) Significant subnetworks enriched for CPD-associated genes in each brain region were identified by integrating the gene-based association strength for CPD from the UKB’s GWAS with the brain-region-specific coexpression subnetworks using PINBPA. (4) Confirmation of gene-set association in each region-specific subnetwork as being collectively associated with CPD using the data from the GWAS of the GSCAN without the UKB samples. (5) Performing protein-protein interaction analyses using STRING and evaluating network properties using CentiScaPe. (6) Evaluation of functional enrichment, whether genes in each subnetwork shared specific functional features, using WebGestalt. Abbreviation: CPD, Cigarettes Per Day. GSCAN, the GWAS and Sequencing Consortium of Alcohol and Nicotine. GWAS, Genome-Wide Association Study. MAGMA, Multi-marker Analysis of GenoMic Annotation. PINBPA, Protein-Interaction-Network-Based Pathway Analysis. STRING, Search Tool for the Retrieval of INteracting Genes/Proteins. WebGestalt, WEB-based GEne SeT AnaLysis Toolkit. WGCNA, Weighted Gene Coexpression Network Analysis.

2.2.1. Construction of coexpression networks with BrainSpan’s gene expression profiles

We performed gene coexpression network analysis using the R package WGCNA (Langfelder and Horvath, 2008) to identify correlation patterns among the expressed genes. We first constructed coexpression networks for the whole brain, as communication within the brain is not confined by regional boundaries. This approach reflects the fact that addiction traits, such as CPD, are known to involve the coordinated functioning of multiple distinct brain regions within neural circuits (Koob and Volkow, 2010). These regions form an extensive and interconnected network. For example, the brain’s reward circuit comprises the ventral tegmental area (VTA), nucleus accumbens (NAc), and striatum. The executive and cognitive function primarily involves the frontal cortex, while reinforcement is governed through the hypothalamus, limbic areas involving the amygdala, and memory-associated regions like the hippocampus (Koob and Volkow, 2010). Therefore, we aim to capture the comprehensive network dynamics underlying the CPD trait’s complexity by examining the whole brain.

More details regarding the parameters are stated in Supplementary Information 1. We then built region-specific coexpression subnetworks for each gene module identified from the whole-brain coexpression network analyses. The absolute value of the correlation coefficient of expression levels for gene pairs ≥0.8 was defined as “connect,” with gene connectivity quantified by the edge weight (0 to 1), as determined by the topological overlap measure, indicating the strength of gene interaction. The nodes with high connectivity were considered hub genes. Specifically, the region-specific subnetwork analysis was conducted for the 15 brain regions within each module identified in the whole-brain coexpression network analysis.

2.2.2. Identification of significant intramodular subnetworks enriched for CPD-associated genes

To integrate the findings of GWAS with the brain transcriptome, we converted the SNP-based summary statistics of UKB’s GWAS on CPD to gene-based p-values using Multi-marker Analysis of GenoMic Annotation (MAGMA), version v1.10, with the flag “--gene-model snp-wise” (de Leeuw et al., 2015). Using the Protein-Interaction-Network-Based Pathway Analysis (PINBPA) program (Wang et al., 2014), we first assigned each gene in the intramodular region-specific coexpression networks (derived from BrainSpan) a corresponding gene-based p-value that indicated the strength of the association with CPD as a node attribute of the interaction networks (Baranzini et al., 2009). We then generated a subnetwork of only significant genes at p<0.05. A subnetwork grew from each node by adding one neighbor iteratively (Baranzini et al., 2009). Finally, we employed a greedy algorithm to search for the n optimal subnetworks. The resultant subnetworks were examined using a permutation test 1000 times; a significant subnetwork was detected when the number of edges was greater than that of 99% of random networks.

2.2.3. Confirmation of the CPD-associated gene subnetworks using an independent dataset

To confirm the link between CPD and the identified gene subnetworks, we conducted gene-set association analyses for CPD using an independent data set from GSCAN (Liu et al., 2019). A gene set includes the genes in each significant subnetwork. We utilized MAGMA using default parameters (de Leeuw et al., 2015) to perform a gene-set analysis with the Bonferroni correction.

2.2.4. Protein interaction networks for functional enrichment analysis: the phenotypic consequence of the subnetworks’ genes

Since proteins form the structural and functional building blocks of cellular life, we investigated the interaction of proteins encoded by the genes of each CPD-associated subnetwork. To test whether proteins encoded by genes in each subnetwork showed significant interactions, we performed permutation tests using the Search Tool for the Retrieval of Interacting Genes/Proteins (STRING), a curated web database of known and predicted protein interactions (Szklarczyk et al., 2019). STRING allowed us to compute the number of directed edges compared to the expected number of edges generated in a random network. A PPI enrichment p-value < 0.05 indicates that the observed nodes in the subnetwork and their connected edges do not occur by chance.

2.2.5. Network-based disease gene prioritization analysis

Network topology provides critical information on the architecture of a network. We applied the CentiScaPe 2.0 software(Scardoni et al., 2009) to investigate the protein network’s topological properties and functional features. Because proteins with a high “betweenness” centrality tend to be drivers of gene expression(Yu et al., 2007), we focused on two core node centrality measures: the network’s betweenness centrality and degree centrality scores. The betweenness centrality score quantifies the number of times a node serves as a bridge along the shortest path between two other nodes, while the degree centrality represents the number of connections a node harbors (Borgatti, 2005).

2.2.6. Gene ontology and pathway enrichment analysis

To gain a deeper functional understanding of the subnetworks, we further annotated them in the knowledge-based databases as implemented in the web-based GEne SeT AnaLysis Toolkit (WebGestalt) (Wang et al., 2013) program for gene ontology (GO) and pathway enrichment analysis. As implemented in WebGestalt, a hypergeometric test computed the enrichment p-value for each GO term and pathway, followed by multiple testing corrections using Benjamini-Hochberg’s false discovery rate (FDR) at p<0.05.

3. Results

3.1. CPD-associated intramodular brain coexpression subnetworks in eight brain regions and their networks of protein interactions

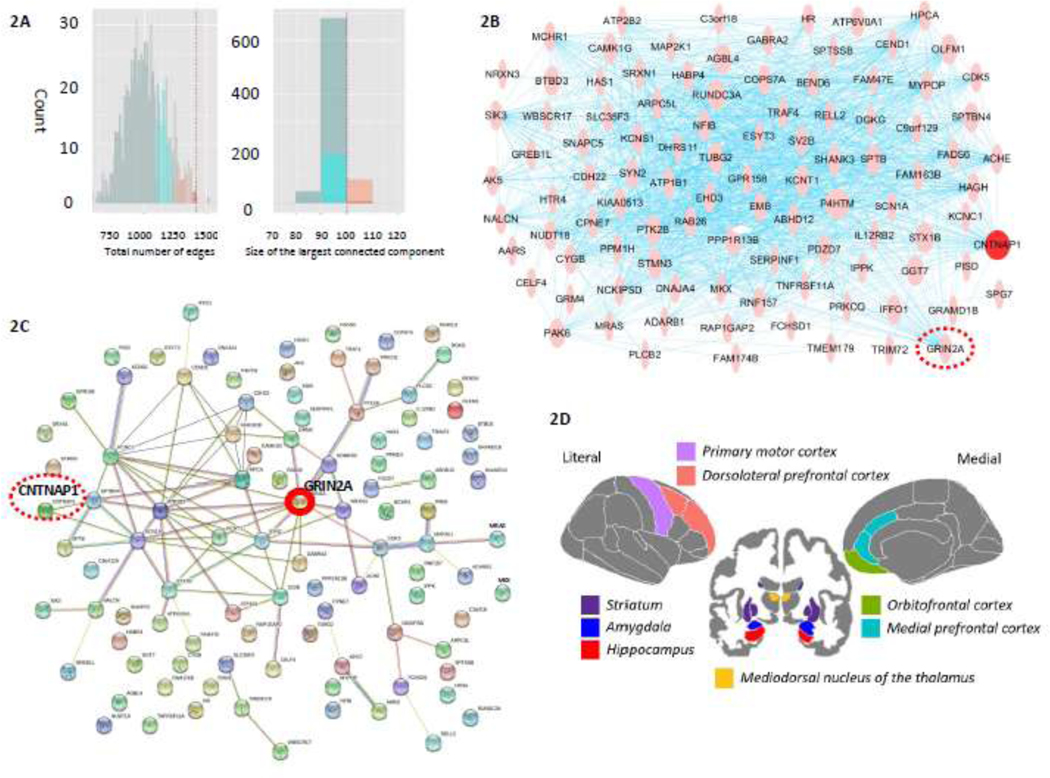

In the whole-brain coexpression network analyses, we obtained 43 gene modules (M1-M43, Supplementary Figure S1) and 645 intramodular coexpression subnetworks (43 modules ×15 brain regions). We tested the statistical significance of the 645 subnetworks associated with CPD using random permutations implemented in PINBPA. Here, each node represented a gene, and an edge was formed when the expression levels of a gene pair were correlated with an r≥0.8. In the M1 module, seven subnetworks enriched for CPD-associated genes were significant (all p-values<0.01), including AMY (100 nodes/1419 edges), HIP (70 nodes/1035 edges), MDTHAL (32 nodes/154 edges), M1C (90 nodes/1600 edges), MPFC (70 nodes/1201 edges), OPFC (50 nodes/647 edges), and STR (30 nodes/140 edges). In the M2 module, the subnetwork for DLPFC (50 nodes/294 edges) was significantly enriched for CPD-associated genes (p<0.01). Specifically, the permutation test by PINBPA identified AMY’s coexpression subnetwork associated with CPD (Figure 2A). The network view of the gene coexpressions in AMY is presented in Figure 2B, in which the hub is CNTNAP1, while the network view of protein interactions for the genes included in the AMY’s subnetwork is shown in Figure 2C with the hub GRIN2A. Figure 2D displays the brain map of the eight regions where the coexpression subnetworks were associated with CPD. Here, we present the results and network views of gene coexpression and protein interaction for the subnetwork in AMY in Figures 2A–2C; the complete network views for all eight regions are shown in Supplementary Figure S2–S4. Table S2 lists all the genes for each of the eight subnetworks.

Figure 2.

(A) Histograms of the random permutation for evaluating the intra-modular subnetwork analysis for the amygdala (p<0.01). The histograms are colored based on different percentiles: 70%, cyan; 90%, pink; and 99%, red. The red dashed line shows the observed subnetwork’s total number of edges and the size of the connected component. (B) Network view of the coexpression subnetwork for the amygdala. Genes (nodes) in the network are sized by their betweenness network centrality score. The blue line indicates the connection between genes. The red node is the hub CNTNAP1, while GRIN2A, the red dashed line circled, is the hub of the protein interaction subnetwork in the amygdala. (C) Network view of the protein interaction subnetwork for the amygdala. The network view delineates the network of predicted associations for the brain subnetwork group of proteins. The hub is GRIN2A, while CNTNAP1, the red dashed line circled, is the hub of the coexpression subnetwork in the amygdala. The network nodes and edges represent proteins and the predicted functional associations, respectively. These colored lines denote the seven types of evidence identified in predicting the associations. A red line implies the presence of fusion evidence. A green line implies neighborhood evidence. A blue line implies co-occurrence evidence. A purple line implies experimental evidence. A yellow line implies text-mining evidence. A light blue line implies database evidence. A black line implies coexpression evidence. (D) The eight brain regions were identified to be the subnetworks associated with cigarettes per day (CPD) (all p<0.01).

3.2. Confirmation of CPD-associated subnetworks in an independent dataset

Using GSCAN’s GWAS summary statistics, we evaluated the cumulative evidence for association with CPD using the gene-set association test implemented in MAGMA for all co-expressed genes in each of the eight subnetworks. The genes in each of these eight subnetwork collectively supported the association with CPD (Table 1).

Table 1. Confirmation of the subnetworks in association with cigarettes per day (CPD).

Results of the gene-set analysis implemented in the Multi-marker Analysis of GenoMic Annotation (MAGMA) for the brain regions of significant coexpression subnetworks associated with CPD using an independent data source, GWAS & Sequencing Consortium of Alcohol and Nicotine (GSCAN).

| Brain Region | BETA1 | SE1 | P | Padjust | Module | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| AMY | Amygdala | 0.209 | 0.08 | 4.50E-03 | 3.60E-02 | M1 |

| HIP | Hippocampus | 0.383 | 0.097 | 4.23E-05 | 3.39E-04 | M1 |

| MPFC | Medial prefrontal cortex | 0.444 | 0.10 | 4.64E-06 | 3.72E-05 | M1 |

| OPFC | Orbitofrontal cortex | 0.461 | 0.11 | 2.11E-05 | 1.70E-04 | M1 |

| DLPFC | Dorsolateral prefrontal | |||||

| cortex | 0.741 | 0.11 | 1.25E-11 | 1.01E-10 | M2 | |

| M1C | Primary motor cortex | 0.305 | 0.086 | 1.96E-04 | 1.58E-03 | M1 |

| STR | Striatum | 0.363 | 0.15 | 6.23E-03 | 4.99E-02 | M1 |

| MDTHAL | Mediodorsal nucleus of the thalamus | 0.407 | 0.14 | 1.84E-03 | 1.48E-02 | M1 |

. BETA, effect estimate; SE, standard error; Padjust, p-values adjusted for multiple testing using Bonferroni correction with significance at Padjust<0.05.

3.3. Gene prioritization based on protein interaction networks identified GRIN2A, PMCA2, and SV2B as the hubs within specific brain regions

We first evaluated whether the eight coexpression subnetworks differed significantly from random networks with regard to protein interactions. We detected 86, 40, 12, 60, 35, 24, and 9 directed edges, as compared with only 23, 12, 3, 20, 11, 6, and 2 expected by chance, in the seven subnetworks of AMY, HIP, MDTHAL, M1C, MPFC, OPFC, and STR, respectively (all p<0.001). For DLPFC, we found 11 directed edges, compared with seven expected by chance (p=0.137). These results indicated that protein interactions based on the CPD-enriched gene subnetworks in AMY, HIP, MDTHAL, M1C, MPFC, OPFC, and STR did not occur by chance. Table 2 shows the top ten CPD-associated genes’ products and their network properties in the network of molecular interactions. Here, in the PPI networks, the betweenness network centrality score represents the number of times a node bridges on the shortest path between other nodes. The hub has the highest betweenness centrality score within each brain region. We found that the gene product of GRIN2A was the hub in AMY (betweenness network centrality score=847.2), the product of SV2B was the hub in M1C (314.1), and the product of PMCA2 was the hub in the HIP, MDTHAL, MPFC, OPFC, and STR (108.0, 22.0, 105.4, 44.0 and 10.0, respectively). Supplementary Table S3 shows the complete list of gene products within each brain region and their network properties.

Table 2. Network properties of the protein interaction subnetworks associated with cigarettes per day (CPD).

The top ten genes’ products are displayed. The protein with the highest betweenness network centrality score within each brain region is the hub node. Degree is the number of connections each node has.

| Amygdala (AMY) | Hippocampus (HIP) | Medial prefrontal cortex (MPFC) | Orbitofrontal cortex (OPFC) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||||

| Gene/Protein | Betweenness | Degree | Gene/Protein | Betweenness | Degree | Gene/Protein | Betweenness | Degree | Gene/Protein | Betweenness | Degree |

| GRIN 2A |

847.3 | 12 | PMC A2 |

108.0 | 9 | PMC A2 |

105.4 | 8 | PMC A2 |

44.0 | 7 |

| CDK 5 |

640.5 | 5 | FAM 163B |

60.0 | 5 | HPC A |

91.2 | 7 | HPC A |

44.0 | 6 |

| SCN1 A |

413.9 | 10 | SCN1 A |

52.4 | 7 | SCN1 A |

74.4 | 6 | KCN C1 |

26.0 | 6 |

| PTK2 B |

330.0 | 4 | STX1 B |

43.0 | 5 | KCN C1 |

40.4 | 7 | DBH | 22.0 | 2 |

| KCN C1 |

302.0 | 12 | HPC A |

36.3 | 6 | DBH | 32.0 | 2 | SPTB N4 |

22.0 | 4 |

| SYN2 | 290.5 | 8 | SV2B | 34.5 | 4 | SV2B | 32.0 | 3 | FAM 163B |

22.0 | 5 |

| PMC A2 |

261.2 | 12 | GRM 4 |

32.0 | 2 | FAM 163B |

32.0 | 5 | MAP 2K1 |

2.0 | 2 |

| MAP 2K1 |

252.0 | 4 | KCN C1 |

30.7 | 7 | NAL CN |

32.0 | 2 | ACH E |

0 | 1 |

| NCKI PSD |

250.0 | 3 | SPTB N4 |

15.8 | 5 | SPTB N4 |

24.6 | 5 | ADA RB1 |

0 | 1 |

| STX1 B |

183.7 | 7 | MAP 2K1 |

2.0 | 2 | MAP 2K1 |

2.0 | 2 | ATP1 B1 |

0 | 2 |

| Primary motor cortex (M1C) | Striatum (STR) | Mediodorsal nucleus of the thalamus (MDTHAL) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| Gene/Protein | Betweenness | Degree | Gene/Protein | Between ness | Degree | Gene/Protein | Betweenness | Degree |

| SV2B | 314.2 | 5 | PMCA2 | 10.0 | 4 | PMCA2 | 22.0 | 5 |

| LAMB3 | 276.0 | 2 | SPTBN4 | 8.0 | 3 | KCNC1 | 14.0 | 4 |

| MET | 240.0 | 2 | MAP2K1 | 2.0 | 2 | SPTBN4 | 12.0 | 3 |

| PMCA2 | 231.9 | 10 | HPCA | 2.0 | 3 | ADARB1 | 0 | 1 |

| PLCB2 | 206.0 | 3 | ADARB1 | 0 | 1 | MAP2K1 | 0 | 1 |

| SYN2 | 176.7 | 6 | ATP1B1 | 0 | 1 | ATP1B1 | 0 | 2 |

| SCN1A | 140.2 | 7 | CEND1 | 0 | 2 | SV2B | 0 | 2 |

| HPCA | 133.5 | 8 | CNTNAP 1 | 0 | 1 | CEND1 | 0 | 2 |

| STX1B | 114.7 | 6 | MRAS | 0 | 1 | CNTNAP1 | 0 | 1 |

| KCNC1 | 111.9 | 9 | CPNE7 | 0 | 1 | |||

3.4. Gene ontology (GO) and pathway enrichment analysis

After adjustment with the Benjamini-Hochberg correction, several GO terms and pathways remained significant (padjust<0.05). The enriched GO terms commonly capture neuronal development, including axonogenesis and differentiation, ribonucleoside biosynthesis, neural transmission, cellular and neuromuscular signaling, and others for the identified brain-region-specific subnetworks (Supplementary Table S4). The pathway enrichments are related to calcium signaling, gonadotropin hormone-releasing hormone (GnRH) signaling, long-term potentiation, carbohydrate digestion and absorption, glycerophospholipid metabolism, salivary secretion, metabolic pathways, pancreatic secretion, long-term depression, pathogenesis of cancer, and others (Supplementary Table S4). Note that pancreatic secretion is found in all significant protein interaction subnetworks except the one for the DLPFC, where protein interactions did not differ significantly from random networks.

4. Discussion

We are the first to interlink BrainSpan’s transcriptomes with GWAS risk variants to detect the neurogenetic mechanism of why some people smoke more. By constructing brain-region-specific coexpression networks enriched by CPD-associated genes, we identified eight coexpression subnetworks in AMY, HIP, MDTHAL, M1C, MPFC, OPFC, STR, and DLPFC and confirmed each subnetwork’s gene-set association in an independent data. Post-genomic analyses to extend the genetic effects to networks of protein interactions suggested that all eight brain regions but DLPFC diverged from a random network. Protein prioritization identified three hub proteins encoded by GRIN2A, PMCA2, and SV2B, with PMCA2 shared by five subnetworks in the HIP, MDTHAL, MPFC, OPFC, and STR. The hubs in these protein interaction subnetworks have been implicated in the pathophysiology of substance misuse, as described below. The seven CPD-associated brain regions share features implicating the neural circuits of stress reactivity (Chaplin et al., 2018), drug memory, decision-making, reward processing, and inhibitory control, all critical to the etiological process of substance misuse. Thus, the brain tissue-specific coexpression network and the gene products’ network analyses appear to capture new, potentially prognostic markers of nicotine use severity and elucidate the complex mechanisms of why some people smoke more.

4.1. GRIN2A in the amygdala and CPD

Here, we report GRIN2A’s gene product as a hub in the amygdala’s protein interaction network associated with CPD. Intramodular hub genes and their gene products in disease-related modules are often clinically significant (Langfelder et al., 2013). GRIN2A encodes ionotropic N-methyl D-aspartate (NMDA) glutamate receptor subunit 2A or GluN2A. GluN2A is a postsynaptic protein subunit of the NMDA receptor, a glutamate-gated ion channel involved in synaptic plasticity, learning, and memory (Franchini et al., 2020). GRIN2A is highly and mostly expressed in the brain (Supplementary Figure S5). Cumulative evidence has suggested the glutamatergic system as a therapeutic target for nicotine addiction (Cross et al., 2018). Variants of GRIN2A have been implicated in heroin, cocaine, and alcohol misuse (Domart et al., 2012; Levran et al., 2016). Functional polymorphisms in GRIN2A affect the amygdala volume of healthy individuals (Inoue et al., 2010). In animals, stress reactivity was absent in GRIN2A-null mutants (Mozhui et al., 2010). GRIN2A-null mutants, including those reared under stress-free conditions, exhibited significant loss of dendritic spines on the amygdala’s principal neurons (Mozhui et al., 2010). Intriguingly, methionine rescued susceptibility to stress by regulating the expression of NMDAR-subunit genes, including the GRIN2A-D and GRIN1 genes (Bilen et al., 2020). These findings suggest that GRIN2A is essential in amygdala reactivity, which might link stress to CPD.

4.2. PMCA2, calcium homeostasis, and nicotinic acetylcholine receptor

As found in the Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) project (GTEx Consortium, 2020), PMCA2 is highly and mostly expressed in the human brain (Supplementary Figure S5). In synaptic membranes, the PMCA2 (also known as ATP2B2) gene encodes plasma membrane calcium ATPase 2 (which pumps calcium out of the cell) and regulates Ca2+ homeostasis and neuronal network synchrony (Martín-de-Saavedra et al., 2022). But the role of PMCA2 in cigarette smoking remains unclear. Gomez-Varela et al. found that PMCA2 regulates postsynaptic neuronal excitability by modulating the density of α7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subunits (α7-nAChR) (Gómez-Varela et al., 2012). Inhibition of PMCA2 impedes the clearance of intracellular Ca2+ and thus triggers a rapid calcium-dependent loss of α7-nAChR clusters on neurons (Gómez-Varela et al., 2012). Moreover, in rats, nicotine has been found to raise intracellular Ca2+ levels in smooth muscle cells of the airway by activating α7-nAChR (Jiang et al., 2014). We found PMCA2’s gene product to be the hub of CPD-associated protein networks in five brain regions, HIP, MDTHAL, MPFC, OPFC, and STR, all of which have been implicated in learning, memory consolidation, decision-making, and reward processing (Hüpen et al., 2022; Klein-Flügge et al., 2022; Mair et al., 2022), the core features of addiction.

4.3. SV2B, primary motor cortex, inhibitory control dysfunction, and level of smoking heaviness

SV2B (synaptic vesicle glycoprotein 2B) encodes one synaptic vesicle glycoprotein 2 family member. SV2B is also primarily expressed in the human brain (Supplementary Figure S5). In animal models, SV2B is present in all motor nerve terminals (Chakkalakal et al., 2010). We found that SV2B’s product is the hub of the protein interactions for the CPD-enriched coexpression subnetwork in the M1C. Although best known for its role in movement planning and execution (Bhattacharjee et al., 2021), M1C is part of the pallidal-thalamic-motor circuit central to reward-modulated inhibitory control (Jones et al., 2020). Individual impulsivity – e.g., choosing an immediate, small reward over a delayed, larger reward – was negatively associated with activation of the M1C and pallidum (Jones et al., 2020). Modulation of M1C activity depends on GABAergic inhibitory networks (Cirillo et al., 2018). Inhibitory control dysfunction is at the core of compulsive drug use and has been associated with the severity of nicotine dependence (Charles-Walsh et al., 2014). The severity of nicotine dependence was associated with higher cue reactivity in brain regions involved in motor preparation and imagery, including the M1C (Smolka et al., 2006). The heaviness of smoking was correlated with less cortical activity, including M1C activity, during successful response inhibition (Galván et al., 2011). Collectively, the smoking level might be mediated by inhibitory control dysfunction with a focal modulating effect of the SV2B protein in the M1C.

4.4. Neural circuits of stress and CPD

The eight brain regions (AMY, HIP, MDTHAL, M1C, MPFC, OPFC, STR, and DLPFC) that we identified with coexpression networks map directly onto the neural circuits of stress, inhibitory control, learning and memory, decision-making, and reward processing (Feil et al., 2010; Klein-Flügge et al., 2022; Pollmann and Schneider, 2022). As part of the stress circuit, the AMY, HIP, and prefrontal cortex (PFC) regulate physiological and behavioral responses to stress (McEwen and Gianaros, 2010). Many studies have associated the severity of tobacco use and cigarette craving with psychosocial stress (Slopen et al., 2013). Chronic stress causes structural changes in the AMY, HIP, and PFC (McEwen et al., 2016). HIP may provide the gateway for emotional distress to affect the structural and functional plasticity of the interconnected brain regions (McEwen et al., 2016). These findings suggest an essential role of the AMY, HIP, MPFC, OPFC, and DLPFC in interlinking stress reactivity and level of smoking.

4.5. Coexpression network versus protein network for the eight brain regions

The biological machinery of gene expression involves complex mechanisms of transcription, translation, and the throughput of mRNAs and proteins (Buccitelli and Selbach, 2020). A rich body of studies has shown varying correlations between mRNA and protein levels, with mRNA transcript levels accounting for an estimated one- to two-thirds of steady-state protein levels (Liu et al., 2016; Vogel and Marcotte, 2012). This may explain the less-than-consistent match between coexpression and consequent protein networks for the eight brain subnetworks (Supplementary Figures S3 and S4). Nevertheless, integrating transcriptomics and proteomics data provides new information and helps discovery (Buccitelli and Selbach, 2020). We found evidence corroborating the link between gene expression and protein networks. For example, in the AMY subnetwork, the hub is CNTNAP1 and GRIN2A in the coexpression and protein network, respectively. The well-known biology of contactin and neurexin might explain the connection between these two hubs. These corroborating scenarios highlight the complexity of the gene and protein networks. Although fascinating, it is beyond the scope of the current study to delineate molecular processes.

4.6. Nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (nAChR) genes and the coexpression networks associated with CPD

Numerous GWAS have previously identified several susceptibility genetic variants in the nAChR genes linked to CPD and other smoking-related behaviors. However, nAChR genes were absent in the significant co-expression networks associated with CPD. Specifically, we retained only four nAChR genes from the transcriptome data following the quality control: CHRNA3, CHRNA4, CHRNA5, and CHRNB2, which all reached genomewide significance in the UKB GWAS on CPD (Supplementary Table S5). The expression levels of these genes were relatively low, consistent with GTEx database observations. For example, CHRNA3 and CHRNA5 had mean expression levels below 1 RPKM, while CHRNA4 and CHRNB2 showed slightly higher expression (mean of 2.7 and 3.6 RPKM, respectively). Moreover, these genes did not meet the threshold to form an edge in our network analysis (r≥0.8) for gene expression levels. This suggests that while nAChR genes are significant in some contexts, they may not be primary contributors to the co-expression networks relevant to CPD. This aligns with our broader discussion on the genetic architecture of CPD, where multiple pathways, including PMCA2 and calcium homeostasis (c.f., the third paragraph in the current Discussion: PMCA2, calcium homeostasis, and nicotinic acetylcholine receptor), might be involved, rather than focusing solely on nAChR genes.

4.7. Strengths, limitations, other considerations, and conclusions of the study

There are several advantages to our study strategy. First, we investigated the brain transcriptome. Transcriptional machinery in the brain directs genes to maintain the structural and functional integrity of neurons, form neural circuits, and, ultimately, support behavior (Keil et al., 2018). Thus, the brain transcriptome provides critical insight into the molecular mechanisms of smoking quantity, our trait of interest. Second, we adapted network analyses to capture the molecular underpinnings of a complex neural system and augmented the network findings with PPI-based data, adding another layer of biological evidence for the region-specific subnetworks. Third, we confirmed the association of subnetworks with CPD in all eight brain regions through gene-set analysis in an independent dataset. Finally, through functional enrichment and PPI analysis of genes in each subnetwork, we identified three hubs, GRIN2A, PMCA2, and SV2B, which are novel risk genes for CPD. Linking the risk genes and pathways with brain subnetworks elucidates the etiology of smoking heaviness.

By first conducting the whole brain network analysis, we effectively accommodate the fact that brain communication linked to CPD involves a complex interaction among various brain regions. However, this approach might inadvertently lose some regional connections. Additionally, although the BrainSpan cohort comprises 71.4% of the data collected prenatally or during early childhood (up to 5 years old), and these subjects can be assumed to have no active smoking, the fetuses’ maternal nicotine exposure was unknown (Supplementary Table S1). The rest of the transcriptomic cohort included two adolescents (12–19 years) and four adults (≥20 years). Although BrainSpan’s recruitment criteria excluded heavy drinkers and smokers, the impact of unknown maternal exposure to smoking or smoking among a few young adult subjects on our results remains unclear. This uncertainty arises from existing evidence indicating that prenatal smoking exposure can alter the brain transcriptome (Semick et al., 2020). Here, we chose not to analyze GTEx brain tissues due to unknown smoking information for GTEx donors who were at least 20 years old. We observed that pancreatic secretion emerged in the GO terms and pathway analysis in all seven significant protein subnetworks. Cigarette smoking is a major risk factor for pancreatic diseases, including pancreatic cancer (Klein, 2021). We speculate that some pleiotropic effects might be involved between pancreatic diseases and cigarette smoking. Also, our current work targeted only the node-level association with CPD; the edge-level, i.e., gene-gene interaction in association with CPD, was excluded because interaction analysis usually suffers from a lack of sufficient information and has unsatisfactory results due to the high dimensionality of genetic measurements (Peng et al., 2021). We focused on the European populations; however, robust GWAS summary statistics for CPD for other non-European ancestry remain lacking. Likewise, smoking’s sex-specific behaviors also require robust GWAS summary statistics to implement our analytical approaches, but these kinds of data are not available.

In conclusion, by integrating GWAS findings and coexpression network analyses, we identified eight significant gene subnetworks and three hub proteins encoded by GRIN2A, PMCA2, and SV2B in the AMY, HIP, MDTHAL, M1C, MPFC, OPFC, and STR, brain areas central to stress response, inhibitory control, learning and memory, decision making, and reward processing. These findings provide new information about the neurogenetic mechanisms of smoking heaviness. Identifying the risk genes and these subnetworks may facilitate researching new pharmacological regimens for smoking cessation.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

We identified eight brain-region-specific coexpression subnetworks associated with cigarettes per day, all of which were critical to the neural process of substance misuse, implicating the neurogenetic mechanisms of individual variation in nicotine use severity.

The three brain region-specific hub proteins, GRIN2A, PMCA2, and SV2B, are encoded by genes implicated in stress response, drug memory, calcium homeostasis, and inhibitory control.

All significant protein interaction subnetworks showed involvement in the pancreatic secretion pathway, indicating a pleiotropic connection between cigarette smoking and pancreatic diseases.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Bo Xiang, co-first author, thanks Professor Joel Gelernter at Yale for giving him a visiting student position in his lab when he was a doctoral student at the West China Clinical Medical College of Sichuan University. Most of the study design was conceived with Dr. Bao-Zhu Yang at the lab during Dr. Xiang’s scholarly visit.

Funding statement.

This study was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health National Institute on Drug Abuse R03DA047562, and partially supported by VA-NCPTSD and R21 CA252916 from the National Institutes of Health/NCI (Yang), R21DA045189 and R01DA051922 (Li), National Natural Science Foundation of China (82001414, Xiang), Ministry of Education Chunhui Plan 2020 (703, Xiang), China Postdoctoral Science Foundation Government (2021M692699, Xiang), Sichuan Provincial Department of Science and Technology (2022YFS0181, Xiang), and Luzhou Science and Technology Bureau-Southwest Medical University (2021LZXNYD-D04, Xiang). The funding agencies played no role in the design and conduct of the study, nor in the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Footnotes

Ethical standards. The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008.

Competing Interests. None.

Author Statement

We used publicly available data for the current study. These data contain no personal identifiers or are aggregated. The research’s ethical review was approved for each individual study that ascertained the data.

Declaration of interest None

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Data availability

The data we utilized to support our discovery are publicly available and can be downloaded from the following links.

U.K. Biobank’s GWAS summary statistics for CPD: http://www.nealelab.is/uk-biobank

GSCAN: https://genome.psych.umn.edu/index.php/GSCAN

BrainSpan’s transcriptome data: https://www.brainspan.org/static/download.html

References

- Baranzini SE, Galwey NW, Wang J, Khankhanian P, Lindberg R, Pelletier D, Wu W, Uitdehaag BM, Kappos L, Polman CH, Matthews PM, Hauser SL, Gibson RA, Oksenberg JR, Barnes MR, 2009. Pathway and network-based analysis of genome-wide association studies in multiple sclerosis. Hum Mol Genet 18 (11), 2078–2090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharjee S, Kashyap R, Abualait T, Annabel Chen SH, Yoo WK, Bashir S, 2021. The Role of Primary Motor Cortex: More Than Movement Execution. J Mot Behav 53 (2), 258–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bilen M, Ibrahim P, Barmo N, Abou Haidar E, Karnib N, El Hayek L, Khalifeh M, Jabre V, Houbeika R, Stephan JS, Sleiman SF, 2020. Methionine mediates resilience to chronic social defeat stress by epigenetic regulation of NMDA receptor subunit expression. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 237 (10), 3007–3020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borgatti SP, 2005. Centrality and Network Flow. Social Networks 27, 55–71. BrainSpan, Donor and Sample Metadata. Available from: http://help.brain-map.org/download/attachments/3506181/Human_Brain_Seq_Stages.pdf?version=1&modificationDate=1433436980032&api=v2.

- Buccitelli C, Selbach M, 2020. mRNAs, proteins and the emerging principles of gene expression control. Nat Rev Genet 21 (10), 630–644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakkalakal JV, Nishimune H, Ruas JL, Spiegelman BM, Sanes JR, 2010. Retrograde influence of muscle fibers on their innervation revealed by a novel marker for slow motoneurons. Development 137 (20), 3489–3499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaplin TM, Niehaus C, Gonçalves SF, 2018. Stress reactivity and the developmental psychopathology of adolescent substance use. Neurobiol Stress 9, 133–139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charles-Walsh K, Furlong L, Munro DG, Hester R, 2014. Inhibitory control dysfunction in nicotine dependence and the influence of short-term abstinence. Drug Alcohol Depend 143, 81–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S, Wang J, Cicek E, Roeder K, Yu H, Devlin B, 2020. De novo missense variants disrupting protein-protein interactions affect risk for autism through gene co-expression and protein networks in neuronal cell types. Mol Autism 11 (1), 76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cirillo J, Cowie MJ, MacDonald HJ, Byblow WD, 2018. Response inhibition activates distinct motor cortical inhibitory processes. J Neurophysiol 119 (3), 877–886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cross AJ, Anthenelli R, Li X, 2018. Metabotropic Glutamate Receptors 2 and 3 as Targets for Treating Nicotine Addiction. Biol Psychiatry 83 (11), 947–954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Leeuw CA, Mooij JM, Heskes T, Posthuma D, 2015. MAGMA: generalized gene-set analysis of GWAS data. PLoS Comput Biol 11 (4), e1004219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domart MC, Benyamina A, Lemoine A, Bourgain C, Blecha L, Debuire B, Reynaud M, Saffroy R, 2012. Association between a polymorphism in the promoter of a glutamate receptor subunit gene (GRIN2A) and alcoholism. Addiction biology 17 (4), 783–785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feil J, Sheppard D, Fitzgerald PB, Yücel M, Lubman DI, Bradshaw JL, 2010. Addiction, compulsive drug seeking, and the role of frontostriatal mechanisms in regulating inhibitory control. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 35 (2), 248–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox MD, Snyder AZ, Vincent JL, Corbetta M, Van Essen DC, Raichle ME, 2005. The human brain is intrinsically organized into dynamic, anticorrelated functional networks. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 102 (27), 9673–9678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franchini L, Carrano N, Di Luca M, Gardoni F, 2020. Synaptic GluN2A-Containing NMDA Receptors: From Physiology to Pathological Synaptic Plasticity. Int J Mol Sci 21 (4). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galván A, Poldrack RA, Baker CM, McGlennen KM, London ED, 2011. Neural correlates of response inhibition and cigarette smoking in late adolescence. Neuropsychopharmacology 36 (5), 970–978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gómez-Varela D, Schmidt M, Schoellerman J, Peters EC, Berg DK, 2012. PMCA2 via PSD-95 controls calcium signaling by α7-containing nicotinic acetylcholine receptors on aspiny interneurons. J Neurosci 32 (20), 6894–6905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goymer P, 2008. Network biology: why do we need hubs? Nat Rev Genet 9 (9), 650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GSCAN, 2019. Summary statistics for association studies of up to 1.2 million individuals yield new insights into the genetic etiology of tobacco and alcohol use. Available from: https://genome.psych.umn.edu/index.php/GSCAN. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- GTEx Consortium, 2020. The GTEx Consortium atlas of genetic regulatory effects across human tissues. Science 369 (6509), 1318–1330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GWAS analysis of the UK Biobank, 2018. Available from: http://www.nealelab.is/uk-biobank.

- Harrow J, Denoeud F, Frankish A, Reymond A, Chen CK, Chrast J, Lagarde J, Gilbert JG, Storey R, Swarbreck D, Rossier C, Ucla C, Hubbard T, Antonarakis SE, Guigo R, 2006. GENCODE: producing a reference annotation for ENCODE. Genome Biol 7 Suppl 1 (Suppl 1), S4 1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hüpen P, Habel U, Votinov M, Kable JW, Wagels L, 2022. A Systematic Review on Common and Distinct Neural Correlates of Risk-taking in Substance-related and Non-substance Related Addictions. Neuropsychol Rev 33, 492–513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue H, Yamasue H, Tochigi M, Suga M, Iwayama Y, Abe O, Yamada H, Rogers MA, Aoki S, Kato T, Sasaki T, Yoshikawa T, Kasai K, 2010. Functional (GT)n polymorphisms in promoter region of N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor 2A subunit (GRIN2A) gene affect hippocampal and amygdala volumes. Genes Brain Behav 9 (3), 269–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iyer KK, Hwang K, Hearne LJ, Muller E, D’Esposito M, Shine JM, Cocchi L, 2022. Focal neural perturbations reshape low-dimensional trajectories of brain activity supporting cognitive performance. Nat Commun 13 (1), 4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Y, Dai A, Zhou Y, Peng G, Hu G, Li B, Sham JS, Ran P, 2014. Nicotine elevated intracellular Ca2+ in rat airway smooth muscle cells via activating and up-regulating α7-nicotinic acetylcholine receptor. Cell Physiol Biochem 33 (2), 389–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones NP, Versace A, Lindstrom R, Wilson TK, Gnagy EM, Pelham WE Jr., Molina BSG, Ladouceur CD, 2020. Reduced Activation in the Pallidal-Thalamic-Motor Pathway Is Associated With Deficits in Reward-Modulated Inhibitory Control in Adults With a History of Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder. Biol Psychiatry Cogn Neurosci Neuroimaging 5 (12), 1123–1133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keil JM, Qalieh A, Kwan KY, 2018. Brain Transcriptome Databases: A User’s Guide. J Neurosci 38 (10), 2399–2412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein-Flügge MC, Bongioanni A, Rushworth MFS, 2022. Medial and orbital frontal cortex in decision-making and flexible behavior. Neuron 110 (17), 2743–2770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein AP, 2021. Pancreatic cancer epidemiology: understanding the role of lifestyle and inherited risk factors. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 18 (7), 493–502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koob GF, Volkow ND, 2010. Neurocircuitry of addiction. Neuropsychopharmacology 35 (1), 217–238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langfelder P, Horvath S, 2008. WGCNA: an R package for weighted correlation network analysis. BMC Bioinformatics 9, 559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langfelder P, Mischel PS, Horvath S, 2013. When is hub gene selection better than standard meta-analysis? PLoS One 8 (4), e61505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leshner AI, 1997. Addiction is a brain disease, and it matters. Science 278 (5335), 45–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levran O, Peles E, Randesi M, da Rosa JC, Ott J, Rotrosen J, Adelson M, Kreek MJ, 2016. Glutamatergic and GABAergic susceptibility loci for heroin and cocaine addiction in subjects of African and European ancestry. Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry 64, 118–123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu M, Jiang Y, Wedow R, Li Y, Brazel DM, Chen F, Datta G, Davila-Velderrain J, McGuire D, Tian C, 2019. Association studies of up to 1.2 million individuals yield new insights into the genetic etiology of tobacco and alcohol use. Nat Genet 51 (2), 237–244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Beyer A, Aebersold R, 2016. On the Dependency of Cellular Protein Levels on mRNA Abundance. Cell 165 (3), 535–550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magger O, Waldman YY, Ruppin E, Sharan R, 2012. Enhancing the prioritization of disease-causing genes through tissue specific protein interaction networks. PLoS Comput Biol 8 (9), e1002690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mair RG, Francoeur MJ, Krell EM, Gibson BM, 2022. Where Actions Meet Outcomes: Medial Prefrontal Cortex, Central Thalamus, and the Basal Ganglia. Front Behav Neurosci 16, 928610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martín-de-Saavedra MD, Dos Santos M, Culotta L, Varea O, Spielman BP, Parnell E, Forrest MP, Gao R, Yoon S, McCoig E, 2022. Shed CNTNAP2 ectodomain is detectable in CSF and regulates Ca2+ homeostasis and network synchrony via PMCA2/ATP2B2. Neuron 110 (4), 627–643. e629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEwen BS, Gianaros PJ, 2010. Central role of the brain in stress and adaptation: links to socioeconomic status, health, and disease. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1186, 190–222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEwen BS, Nasca C, Gray JD, 2016. Stress effects on neuronal structure: hippocampus, amygdala, and prefrontal cortex. Neuropsychopharmacology 41 (1), 3–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller JA, Ding S-L, Sunkin SM, Smith KA, Ng L, Szafer A, Ebbert A, Riley ZL, Royall JJ, Aiona K, 2014. Transcriptional landscape of the prenatal human brain. Nature 508 (7495), 199–206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mozhui K, Karlsson RM, Kash TL, Ihne J, Norcross M, Patel S, Farrell MR, Hill EE, Graybeal C, Martin KP, Camp M, Fitzgerald PJ, Ciobanu DC, Sprengel R, Mishina M, Wellman CL, Winder DG, Williams RW, Holmes A, 2010. Strain differences in stress responsivity are associated with divergent amygdala gene expression and glutamate-mediated neuronal excitability. J Neurosci 30 (15), 5357–5367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng W, Tan Q, Yu M, Wang P, Wang T, Yuan J, Liu D, Chen D, Huang C, Tan Y, 2021. Transcriptome Sequencing Reveals the Potential Mechanisms of Modified Electroconvulsive Therapy in Schizophrenia. Psychiatry Investigation 18 (5), 385–391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollmann S, Schneider WX, 2022. Working memory and active sampling of the environment: Medial temporal contributions. Handb Clin Neurol 187, 339–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahni N, Yi S, Taipale M, Fuxman Bass JI, Coulombe-Huntington J, Yang F, Peng J, Weile J, Karras GI, Wang Y, Kovács IA, Kamburov A, Krykbaeva I, Lam MH, Tucker G, Khurana V, Sharma A, Liu YY, Yachie N, Zhong Q, Shen Y, Palagi A, San-Miguel A, Fan C, Balcha D, Dricot A, Jordan DM, Walsh JM, Shah AA, Yang X, Stoyanova AK, Leighton A, Calderwood MA, Jacob Y, Cusick ME, Salehi-Ashtiani K, Whitesell LJ, Sunyaev S, Berger B, Barabási AL, Charloteaux B, Hill DE, Hao T, Roth FP, Xia Y, Walhout AJM, Lindquist S, Vidal M, 2015. Widespread macromolecular interaction perturbations in human genetic disorders. Cell 161 (3), 647–660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scardoni G, Petterlini M, Laudanna C, 2009. Analyzing biological network parameters with CentiScaPe. Bioinformatics 25 (21), 2857–2859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Semick SA, Collado-Torres L, Markunas CA, Shin JH, Deep-Soboslay A, Tao R, Huestis MA, Bierut LJ, Maher BS, Johnson EO, Hyde TM, Weinberger DR, Hancock DB, Kleinman JE, Jaffe AE, 2020. Developmental effects of maternal smoking during pregnancy on the human frontal cortex transcriptome. Mol Psychiatry 25 (12), 3267–3277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slopen N, Kontos EZ, Ryff CD, Ayanian JZ, Albert MA, Williams DR, 2013. Psychosocial stress and cigarette smoking persistence, cessation, and relapse over 9–10 years: a prospective study of middle-aged adults in the United States. Cancer Causes Control 24 (10), 1849–1863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smolka MN, Bühler M, Klein S, Zimmermann U, Mann K, Heinz A, Braus DF, 2006. Severity of nicotine dependence modulates cue-induced brain activity in regions involved in motor preparation and imagery. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 184 (3–4), 577–588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szklarczyk D, Gable AL, Lyon D, Junge A, Wyder S, Huerta-Cepas J, Simonovic M, Doncheva NT, Morris JH, Bork P, 2019. STRING v11: protein–protein association networks with increased coverage, supporting functional discovery in genome-wide experimental datasets. Nucleic Acids Res 47 (D1), D607–D613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogel C, Marcotte EM, 2012. Insights into the regulation of protein abundance from proteomic and transcriptomic analyses. Nat Rev Genet 13 (4), 227–232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Duncan D, Shi Z, Zhang B, 2013. WEB-based GEne SeT AnaLysis Toolkit (WebGestalt): update 2013. Nucleic Acids Res 41 (Web Server issue), W77–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L, Matsushita T, Madireddy L, Mousavi P, Baranzini SE, 2014. PINBPA: cytoscape app for network analysis of GWAS data. Bioinformatics 31 (2), 262–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization, 2021. Tobacco Key Facts. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/tobacco.

- Yu H, Kim PM, Sprecher E, Trifonov V, Gerstein M, 2007. The importance of bottlenecks in protein networks: correlation with gene essentiality and expression dynamics. PLoS Comput Biol 3 (4), e59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data we utilized to support our discovery are publicly available and can be downloaded from the following links.

U.K. Biobank’s GWAS summary statistics for CPD: http://www.nealelab.is/uk-biobank

GSCAN: https://genome.psych.umn.edu/index.php/GSCAN

BrainSpan’s transcriptome data: https://www.brainspan.org/static/download.html