Abstract

CD4 T cells play a central role in viral immunity. They provide help for B cells and CD8 T cells and can act as effectors themselves. Despite their importance, relatively little is known about the magnitude and duration of virus-specific CD4 T-cell responses. In particular, it is not known whether both CD4 Th1 memory and CD4 Th2 memory can be induced by viral infections. To address these issues, we quantitated virus-specific CD4 Th1 (interleukin 2 [IL-2] and gamma-interferon) and Th2 (IL-4) responses in mice acutely infected with lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus (LCMV). Using two sensitive assays (enzyme-linked immunospot assay and intracellular stain) to measure cytokine production at the single-cell level, we found that both CD4 Th1 and Th2 responses were induced during primary LCMV infection. At the peak (day 8) of the response, the frequency of LCMV-specific CD4 Th1 cells was 1/35 to 1/160 CD4 T cells, and the frequency of Th2 cells was 1/400. After viral clearance, the numbers of virus-specific CD4 T cells dropped to 1/260 to 1/3,700 and then were maintained at this level indefinitely. Upon rechallenge with LCMV, both CD4 Th1 and Th2 memory cells made an anamnestic response in vivo. These results show that unlike some microbial infections in which only Th1 or Th2 responses are seen, an acute viral infection can induce a mixed CD4 T-cell response with long-term memory.

CD4 T cells play an important role in viral immunity. In viral infections such as vesicular stomatitis virus, influenza A virus, and Sendai virus, CD4 T cells help B cells secrete neutralizing antibody which facilitates viral clearance. Some antiviral CD8 T-cell responses are critically dependent upon CD4 T-cell help. These include responses against adenovirus, chronic lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus (LCMV) (24), herpes simplex virus (17), and gammaherpesvirus-68 or MHV-68 (10) infections. Even in acute LCMV infection, CD4-knockout mice (CD4−/−) mice produce two- to threefold-fewer cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs) compared to CD4+/+ mice during the primary response and show a gradual decline in number of antiviral memory CTLs over time (36). The importance of CD4 T cells is highlighted by the finding that mice deficient in functional CD4 T-cell responses (CD4-depleted or CD4−/− mice) are unable to generate large numbers of CTLs and cannot control strains of LCMV which replicate quickly (24). In humans, a decrease in T-helper-cell number associated with human immunodeficiency virus infection is associated with a loss of virus-specific CD8 CTLs and an increase in viral titer and susceptibility to other infectious agents. With the exception of influenza virus and Sendai virus infections of mice (14, 32), relatively little is known about the primary burst size of virus-specific CD4 T cells following systemic viral infection and the size of the CD4 memory pool.

Furthermore, little is known about the types of CD4 T cells which develop after viral infection. After antigenic stimulation, T-helper development proceeds along two paths: one leads to formation of T-helper type 1 (Th1) cells, and the other leads to Th2 cells (reviewed in references 1 and 26). Th1 cells and Th2 cells can be distinguished by differences in their cytokine profiles. Th1 cells secrete IL-2, tumor necrosis factor alpha, tumor necrosis factor β (lymphotoxin-α), and gamma-interferon (IFN-γ) and assist in activating CD8 T cells and macrophages and promote immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibody class switching to the IgG2a isotype, whereas Th2 cells make IL-4, IL-5, and IL-10 and facilitate B-cell activation and the development of IgG1 antibody. Each T-helper subset governs the other, because cytokines produced by one subset negatively regulate the production of cytokines by the other. Leishmania major infection in mice provides an example of the biological implication of these opposing T-helper cells: mice that are prone to making high levels of Th1 cytokines in response to this intracellular parasite resolve the infection, whereas mice that tend to make less IFN-γ are susceptible (15). As another example, the autoimmune disease experimental allergic encephalomyelitis (EAE) in mice is induced by autoreactive Th1 cells (20). Induction of Th2 cells and cytokines ameliorates the disease (11, 18). While still controversial, it has been reported that human immunodeficiency virus-infected individuals switch from a Th1 to a Th2 phenotype as they progress in disease (12), and it is not known why this change occurs. It is also unknown how many Th1 and Th2 cells are generated, what mechanisms govern development of one type over the other, and the biological implications of this in acute viral infection.

In this report, we document the activation and expansion of virus-specific CD4 T cells and the longevity of CD4 T-cell memory in mice infected with LCMV. We report that by 1 week postinfection, there was expansion of virus-specific IFN-γ-secreting CD4 T cells resulting in a frequency of 1/35 CD4 T cells, which then declined during the following 2 to 3 weeks to 1/260 CD4 T cells. This number was stably maintained for at least 250 days postinfection, and immune mice were able to mount accelerated secondary CD4 responses following rechallenge. Most LCMV-specific T cells were of the Th1 type, but large numbers of Th2 CD4 T cells were also generated and maintained. Given the central role of CD4 T cells in providing help for generating and maintaining memory CTL responses and B-cell responses, our data indicate that vaccine strategies which target CD4 helper cells may prove useful for increasing the numbers of these cells for protective anamnestic responses against viral infections.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice.

C57BL/6 (H-2b) mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, Maine. The C57BL/6 carrier mice used in these experiments were generated and bred at Emory University as previously described (4). These mice are congenitally infected and express viral protein in the context of major histocompatibility class I (MHC I) and MHC II molecules.

Virus.

The Armstrong CA 1371 strain of LCMV was used in these studies for infection of mice (5). Infectious virus in serum and liver was quantitated by plaque assay on Vero cells (5).

Flow cytometry.

Spleen cells were stained with antibodies which recognize CD8 (clone 53-6.7), CD4 (clone RM4-5), and CD44 (clone IM7) with a concentration of 1 μg of antibody/106 cells. These antibodies were purchased from Pharmingen (La Jolla, Calif.). Annexin V-fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC), used to measure apoptotic cells, was purchased from Pharmingen, and the manufacturer’s recommended protocol was followed.

CD4 T-cell enrichment.

CD4 T-cell enrichment by negative selection was done with CD4 enrichment columns. Mouse CD4 subset column kits were purchased from R & D systems (Minneapolis, Minn.), and the manufacturer’s suggested protocol was used. CD4 T cells were >80% pure by this protocol, and the number of CD8 T cells was <0.5%, as indicated by flow cytometry. As an additional check on the level of CD8 T-cell contamination, NP396-404, an MHC I-restricted peptide, was added to CD4 cell-enriched cultures in some experiments, and the number of virus-specific CD8 T cells was quantitated by enzyme-linked immunospot assay (ELISPOT). By this test, there was little to no detectable CD8 T-cell contamination above background levels in the CD4 T-cell-enriched cultures. The number of CD4 T cells recovered after column enrichment was 25 to 50% of the initial number loaded onto the column. Analysis of CD44 expression before and after column enrichment indicated that there was a relative loss of subset CD44hi (activated) cells during the enrichment process (data not shown).

Quantitation of virus-specific IFN-γ-secreting CD8 and CD4 T cells.

Virus-specific CD8 and CD4 T-cell responses were measured by IFN-γ ELISPOT assay (13, 30) by using whole spleen cells or CD4 purified preparations from mice immunized with LCMV. The capture antibody for this assay, rat anti-mouse IFN-γ (clone R4-6A2; Pharmingen), was used at 2 μg/ml (100 μl/well) in ester-cellulose-bottom plates (Millipore, France). After dilutions of effector cells were added to the plate, feeder cells (1,200-rad-irradiated uninfected mouse spleen cells) were added at 5 × 105 cells per well to maintain cell-cell contact. Effector cells were incubated for 36 h at 37°C without (medium alone) or with stimulation. For stimulation, either carrier mouse spleen cells or purified LCMV peptides which bind to MHC I and can stimulate CD8 T-cell responses specifically (25, 35) or LCMV peptides which bind to MHC class II (NP309-328 and GP61-80 of Armstrong) and stimulate only I-Ab-restricted CD4 T-cell responses (27) were used. After the culture period, cells were removed by washing the plate in phosphate-buffered saline–Tween (0.05%), and then biotinylated antimouse IFN-γ (clone XMG1.2; Pharmingen) was added at 4 μg/ml (100 μl per well). After overnight incubation at 4°C, unbound antibody was removed, and horseradish peroxidase–avidin D (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.) was added. Spots were developed with the substrate 3-amino-9-ethyl-carbazole (Sigma) with 0.015% H2O2. Each spot represents an IFN-γ-secreting cell, and the frequency of these cells can be determined by dividing the number of spots counted in each well by the total number of cells plated at that dilution. Uninfected spleen cells contain IFN-γ-producing cells at a frequency of ≤2 per 106 cells with or without stimulation. MHC I-restricted peptides NP396-404, GP33-41, and GP276-286 were used at a final concentration of 0.1 μg/ml to stimulate CD8 T cells, and MHC II-restricted peptides NP309-328 and GP61-80 were used at a final concentration of 1.0 μg/ml to stimulate CD4 T cells.

Quantitation of virus-specific IL-2- and IL-4-secreting CD4 T cells.

ELISPOT assays for measuring IL-2- or IL-4-secreting CD4 T cells were done in the same fashion as the IFN-γ ELISPOT assay. Purified splenic CD4 T cells from infected mice were stimulated with or without carrier spleen cell stimulation. The capture antibody for the IL-2 ELISPOT assay, purified antimouse IL-2 (clone JES6-1A12; Pharmingen), was used at a concentration of 8 μg/ml, and the biotinylated antimouse IL-2 detection antibody (clone JES6-5H4; Pharmingen) was used at 4 μg/ml (100 μl/well). Purified antimouse IL-4 (clone BVD4-1D11; Pharmingen) was used at 4 μg/ml as the capture antibody for the IL-4 ELISPOT, and biotinylated antimouse IL-4 (clone BVD6-24G2; Pharmingen) was used at a concentration of 4 μg/ml. Uninfected spleen cells contain IL-2-secreting cells at a frequency of <2 per 106 cells and IL-4-secreting cells at a frequency of <2 per 106 cells.

Cytokine ELISAs.

Cytokine ELISAs were done with cytokine-specific ELISA kits purchased from Genzyme Diagnostics (Cambridge, Mass.) and were performed and analyzed as recommended by the manufacturer. The ELISAs were read with a Bio-Rad Microplate reader 3550 (Bio-Rad, Hercules, Calif.) with the appropriate filters.

Intracellular staining for IFN-γ.

Spleen cells (106 cells per well in 96-well flat-bottom plates) were stimulated in vitro with media or with NP309-328 and GP61-80 (1.0 μg/ml) for 5 h in vitro with brefeldin A (Golgestop; Pharmingen). They were then harvested, washed once in PBS containing 1% BSA and 0.2% sodium azide, and stained with phycoerythrin-conjugated monoclonal anti-CD4 antibody (clone RM4-5; Pharmingen). After washing of unbound antibody, the cells were permeabilized and stained for intracellular IFN-γ with a Cytofix/Cytoperm staining kit (Pharmingen) as per the manufacturer’s recommended protocol. For intracellular IFN-γ staining, we used FITC-conjugated monoclonal rat anti-mouse IFN-γ (clone XMG1.2) and its control isotype antibody (rat IgG1) (Pharmingen) (25).

Analysis of turnover rates of T cells.

Mice were fed bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU; Sigma Chemical Co.) for 1 week in drinking water (0.8 mg/ml) as described previously (33). BrdU, a nucleoside analog, is incorporated into the DNA of cells, which divide (turnover) during the labeling period. Cells which have incorporated BrdU can be identified by staining. Cells were first surface stained with anti-CD4 and anti-CD44 antibodies as described above and then were fixed with 67% ethanol for 30 min at 4°C. After permeabilization with 1% paraformaldehyde containing 0.01% Tween 20 for 30 min at room temperature, the cells were incubated with 50 Kunitz units of DNAse I (Sigma Chemical Co.) for 10 min at room temperature. They were then stained with FITC–anti-BrdU (Becton Dickinson, Mountain View, Calif.), followed by flow cytometric analysis.

RESULTS

Activation and expansion of CD4 T cells.

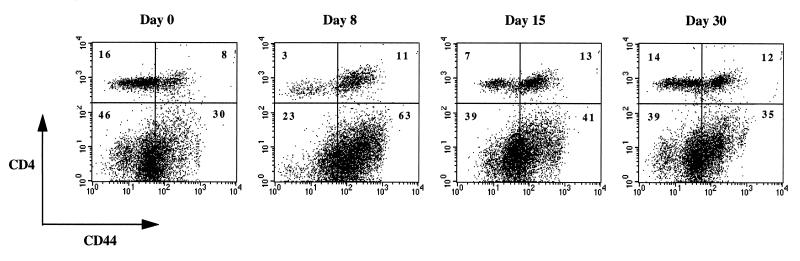

To investigate primary CD4 T-cell responses during viral infection, mice were infected with 2 × 105 PFU of the Armstrong strain of LCMV, and T-cell responses were analyzed by flow cytometry. Consistent with previous reports (2, 6, 21, 37), large numbers of CTLs were generated, and infection was controlled by day 8 postinfection, as indicated by plaque assay of serum and liver (data not shown). Figure 1 shows that there was a shift in the number of CD4 T cells which expressed the activation marker CD44 following infection. In naive mice, most cells were of the CD44lo subset (resting), but the ratio of CD44hi to CD44lo changed from 0.5 at day 0 to 3.7 by day 8. This ratio changed to 1.9 by day 15 as the immune response to LCMV was subsiding and approached homeostasis by day 30 at ∼0.9.

FIG. 1.

Activation of CD4 T cells. Spleen cells from mice at days 0, 8, 15, and 30 after infection were stained for CD4 and CD44. A representative flow cytometric analysis is shown. Note that CD4 T cells become activated as there is an increase in the proportion of CD4 T cells expressing CD44. Since most of the expansion found in the spleen at day 8 postinfection is due to CD8 T cells, the relative percentage of CD4 T cells appears to decrease. Interestingly, activation of these cells is associated with an increase in CD4 fluorescence intensity, because the density of CD4 is higher than in unactivated cells. Numbers indicate the percentage of cells in each quadrant.

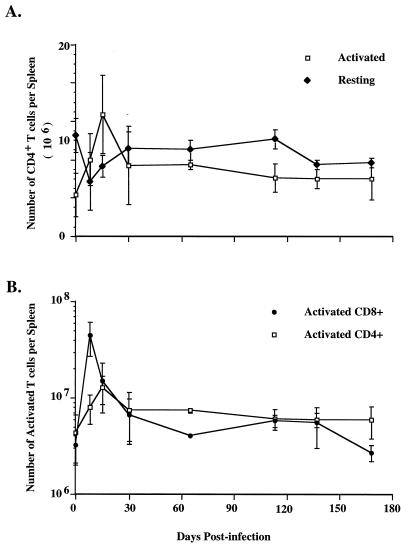

Activation was also associated with an increase in cell number. The number of activated CD44hi CD4 T cells increased from 4 × 106 per spleen at day 0 to 8 × 106 per spleen at day 8 and 13 × 106 by day 15 (Fig. 2A). In contrast, the number of CD44lo CD4 T cells changed little after infection. There was a slight decrease in number at day 8, but cell numbers returned to ∼9 × 106 by day 30. Figure 2B shows that CD8 T cells had a more pronounced increase in cell number in the same mice. The number of CD44hi CD8 T cells increased from 3 × 106 per naive spleen to 45 × 106 per spleen at day 8 postinfection, fivefold more than the number of activated CD4 T cells.

FIG. 2.

Expansion of T cells following LCMV infection. Spleen cells from mice at various time points postinfection were stained for CD4, CD8, and CD44, and the numbers of T cells which were activated (CD44hi) or resting (CD44lo) were determined by flow cytometry. The data were taken from more than four experiments and include 6 to 15 mice for each time point. The error bars show standard deviations.

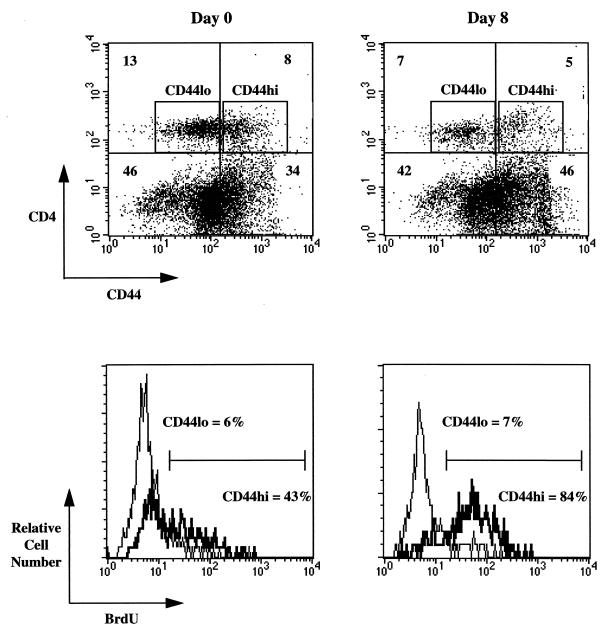

To investigate whether the increase in cell number was due to cell division, mice were fed BrdU in their drinking water during the first week of infection, and the number of CD4 T cells which incorporated BrdU was measured by flow cytometry. Figure 3 shows that in mice responding to infection, 84% of CD44hi CD4 T cells divided during the period from day 0 to day 8, whereas only 43% of CD44hi cells from naive mice divided. CD44lo cells did not proliferate in response to infection, and the number of these cells which were BrdU positive (7%) was comparable to that found in naive mice (6%). These data indicate that there was virus-induced cell division among the CD44hi cells, and the increase in the number of activated CD4 T cells in the spleen represents expansion of T cells rather than recruitment to this site.

FIG. 3.

In vivo proliferation of CD4 T cells after viral infection. BrdU incorporation by dividing T cells was measured in naive mice and mice responding to LCMV infection during the primary phase (days 0 to 8). Activated and resting CD4 T cells (top) were analyzed for BrdU incorporation (below). As indicated, 84% of activated CD4 T cells incorporated BrdU in infected mice, whereas only 43% of activated CD4 T cells were BrdU positive in naive mice. This demonstrates that CD4 T cells which became CD44hi divided after infection. In contrast, resting (CD44lo) CD4 T cells showed no change in BrdU incorporation in response to infection. The ratio of activated to unactivated CD4 T cells was lower in mice fed BrdU than in infected control mice. There is a slight loss in the number of activated cells, most likely due to low-level toxicity of this compound in cells which have incorporated it into their DNA.

Development of long-term CD4 Th1 memory.

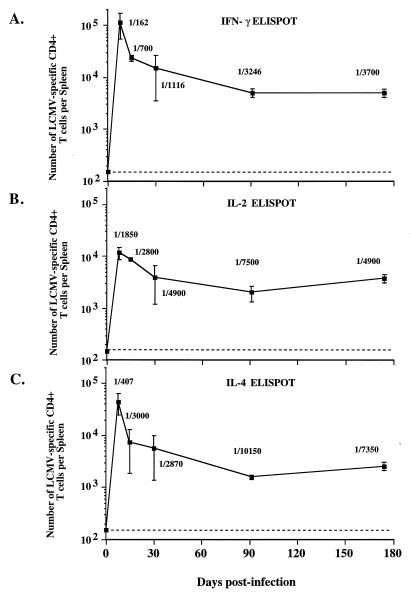

To quantitate the number of virus-specific CD4 Th1 cells following infection, splenic CD4 T cells were purified by column enrichment and analyzed with IFN-γ and IL-2 ELISPOT assays following virus restimulation. The frequency of IFN-γ-secreting LCMV-specific CD4 T cells increased to 1/162 CD4 T cells by day 8 (Fig. 4A). This frequency corresponded to 1.1 × 105 virus-specific CD4 cells per spleen.

FIG. 4.

Generation and maintenance of memory CD4 T cells. Mice were sacrificed at various times postinfection with LCMV, and CD4 T cells were column purified and analyzed by cytokine ELISPOT as indicated. As can be seen, there are three clear phases of the CD4 T-cell response: activation (days 0 to 8), where virus-specific T cells expand to 4 × 105 to 6 × 105 per spleen; death (days 8 to 30), where 90% of the T cells die; and memory (days >30), where elevated numbers of virus-specific CD4 T cells remain. These features can be seen for IFN-γ-secreting CD4 T cells (A), IL-2-secreting cells (B), and IL-4-secreting cells (C). The numbers shown are frequencies of cytokine-secreting CD4 T cells per total CD4 T cells. Note that there was no decay in the number of memory CD4 T cells over time. The error bars represent standard deviations, and the limit of detection is indicated by the dashed line.

Following the peak of the CD4 response, there was a period in which 87 to 95% of the virus-specific CD4 T cells died. Annexin V staining of CD4 T cells during this period indicated that ∼40% of CD4 T cells were apoptotic, and 10 to 15% of CD4 T cells from naive mice were apoptotic in the same assay (data not shown). By 1 to 2 months postinfection, the frequency of IFN-γ-secreting memory CD4 T cells ranged from 1/1,100 to 1/3,246 CD4 T cells, corresponding to 4 × 103 to 3 × 104 per spleen (Fig. 4A). Even at 6 months, elevated numbers of IFN-γ-secreting memory Th1 CD4 cells (5 × 103 per spleen) could be found.

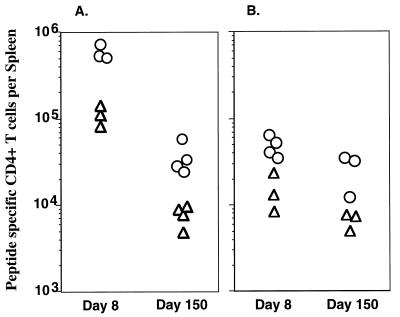

The Th1 response was also quantitated at the epitope level by IFN-γ ELISPOT. Figure 5A shows that at the peak of the response (day 8), 5 × 105 CD4 T cells per spleen (1/38 CD4) recognized LCMV GP61-80 and 1.3 × 105 CD4 T cells per spleen (1/139) recognized LCMV NP309-328. In immune mice (day 150), fewer cells could be found which recognized these epitopes; however, there remained 3.1 × 104 CD4 T cells per spleen (1/336) which recognized GP61-80 and 9.0 × 103 CD4 T cells per spleen (1/1,126) which recognized NP309-328, which shows that long-term Th1 memory exists for both epitopes. Interestingly, three- to fourfold more cells recognized GP61-80 than NP309-328 during the peak of the response and during the memory phase. This suggests that during the death phase, there was no selective loss of one population of cells, because there was an ∼15-fold drop in number of CD4 T cells specific for both epitopes.

FIG. 5.

Epitope-specific analysis of CD4 T-cell responses. The number of CD4 T cells responding to LCMV GP61-80 (○) or NP309-328 (▵) was quantitated by IFN-γ ELISPOT at days 8 and 150 after infection (A). There was an increase in the number of cells responding to both epitopes at day 8. The frequency of GP61-80-specific CD4 T cells was 1/38, and the frequency of NP309-328-specific CD4 T cells was 1/139. Immune mice retained elevated numbers of virus-specific CD4 cells of both specificities, with 1/336 specific to GP61-80 and 1/1,126 specific for NP309-328. The number of epitope-specific CD4 T cells was also quantitated by IL-4 ELISPOT (B). At day 8, the frequency of GP61-80-specific cells was 1/200 and the frequency of NP309-328-specific cells was 1/600. At day 150, the frequencies were 1/400 for GP61-80 and 1/1,620 for NP309-328, indicating that IL-4-secreting memory cells specific to both epitopes were maintained.

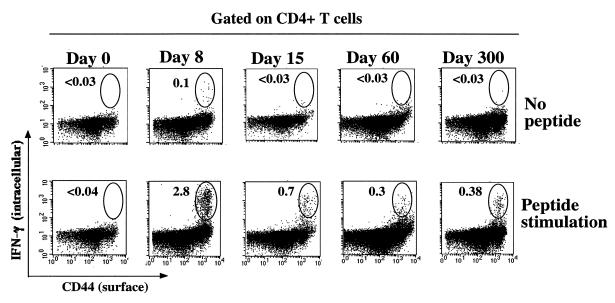

The LCMV-specific CD4 Th1 response was also characterized by intracellular staining for IFN-γ following restimulation with NP309-328 and GP61-80. Figure 6 depicts CD4 T cells surface stained for CD44 and stained for intracellular IFN-γ. Less than 0.04% (1/2,500) of naive CD4 T cells (day 0) produced IFN-γ following stimulation (<4,400/spleen), but by day 8, 2.8% of CD4 T cells (1/36) made IFN-γ upon restimulation, for a total of 7.8 × 105 per spleen. Since all of these cells were in the CD44hi subset, this corresponded to a frequency of 1/18 activated CD4 T cells. There was a decrease in the percentage of CD4 T cells which made IFN-γ at day 15 to 0.7% (1/143), and there was a drop in number to 5.9 × 104 virus-specific cells per spleen. Afterwards, CD4 memory was stable, because the percentage of virus-specific CD4 T cells changed very little from day 60 (0.3%) to day 300 (0.4%). The frequency of memory cells per activated CD4 cell was 1/47 at day 300, which corresponded to 4.1 × 104 per spleen.

FIG. 6.

Longevity of LCMV-specific CD4 T cells. Results represent intracellular IFN-γ in CD4 T cells responding to NP309-328 and GP61-80 at days 0, 8, 15, 60, and 300 postinfection. Spleen cells were stimulated for 5 h with peptide and then surface stained for CD4 and CD44 and stained for intracellular IFN-γ. Flow cytometry dot plots gated on CD4 T cells show expression of IFN-γ (y axis) versus that of CD44 (x axis). The numbers shown are the percentage of CD4 cells which are IFN-γ positive. Following the expansion of LCMV-specific CD4 T cells at day 8 (IFN-γ positive), there was a decrease, which can be seen at day 15. The frequency of memory cells established by day 60 remained unchanged even at day 300. At day 8, some CD4 T cells made IFN-γ even without stimulation. These probably represent activated cells which were IFN-γ positive in vivo and retained the cytokine throughout the staining process. Note that all CD4 T cells making IFN-γ in response to these peptides were CD44hi.

The numbers of IL-2-secreting Th1 cells followed a similar pattern, as did the IFN-γ-secreting cells (Fig. 4B). There were 1.2 × 104 LCMV-specific IL-2-secreting CD4 T cells per spleen at the peak of the expansion phase at day 8. By days 15 to 30, there was a drop in number, but large numbers of LCMV-specific memory cells (4 × 103 per spleen) remained during the memory phase 6 months after infection.

Development of long-term CD4 Th2 memory.

To quantitate the number of virus-specific Th2 cells after acute infection, splenic CD4 T cells were purified and analyzed by IL-4 ELISPOT. Similar to the Th1 response, the Th2 response peaked at day 8. The frequency of LCMV-specific CD4 T cells at this time was 1/407 CD4 T cells, which corresponded to 5 × 104 virus-specific Th2 cells per spleen (Fig. 4C).

Following the peak, there was a period (days 8 to 30) in which the number of IL-4-secreting cells decreased. After this time, substantial numbers of memory IL-4-secreting cells (2 × 103 to 6 × 103 per spleen) were stably maintained for at least 6 months postinfection (Fig. 4C).

Figure 5B shows the number of IL-4-secreting cells specific to GP61-81 and NP309-328. At day 8, 4 × 104 to 7 × 104 CD4 T cells per spleen (1/200 CD4 cells) recognized LCMV GP61-80, and 1 × 104 to 2 × 104 CD4 T cells per spleen (1/600) recognized LCMV NP309-328. At day 150, there remained 1 × 104 to 3 × 104 CD4 T cells per spleen (1/400) which recognized GP61-80 and 5 × 103 to 7 × 103 CD4 T cells per spleen (1/1,620) which recognized NP309-328. Similar to what was found for the number of IFN-γ-secreting cells (Fig. 5A), there was long-term Th2 memory for both epitopes, with more of the response directed at GP61-80 than at NP309-328.

ELISA analysis of purified CD4 T cells demonstrated that IL-10-producing cells were also generated following infection. In naive mice, <15 ρg/ml was found in virus-stimulated supernatants, whereas at day 8, 105 ρg/ml was made. Furthermore, spleen cells taken from mice immunized 150 days earlier produced high levels of IL-10 (180 ρg/ml) upon virus stimulation, demonstrating that long-term CD4 Th2 memory was generated after LCMV infection.

Anamnestic responses of CD4 memory T cells upon rechallenge.

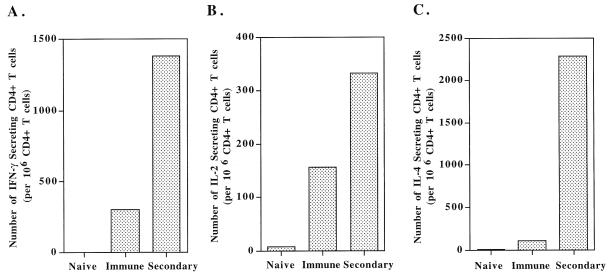

To further demonstrate the existence of large numbers of memory T-helper cells, immune mice and naive mice were challenged with LCMV strain Armstrong, and at day 3, T-cell responses were analyzed by fluorescence-activated cell sorter and ELISPOT. There were more activation and expansion of CD4 and CD8 T cells in rechallenged immune mice than in immune controls, and naive mice showed no activation at this early time point (data not shown). Figure 7 shows that while naive mice did not mount a specific response by day 3 and immune mice had elevated numbers of virus-specific CD4 T cells, rechallenged immune mice showed a 4.5-fold increase in IFN-γ-secreting CD4 T cells and an increase in IL-2-secreting memory CD4 T cells (Fig. 7A and B). The frequency of IL-4-secreting cells also increased after rechallenge (Fig. 7C). This shows that the Th1 and Th2 cells which were present in immune mice could expand in number quickly in response to reinfection.

FIG. 7.

Immune mice make accelerated CD4 T-cell responses following rechallenge. Mice immunized >3 months earlier with 2 × 105 PFU of LCMV Armstrong were rechallenged with 106 PFU of LCMV (intraperitoneal). Purified splenic CD4 T cells were analyzed at day 3 postrechallenge by IFN-γ ELISPOT (A), IL-2 ELISPOT (B), and IL-4 ELISPOT (C). Immune mice generated an accelerated immune response by day 3 (Secondary). In contrast, naive mice that received the challenge dose did not mount a response at this time. Immune mice that were not rechallenged are shown for comparison.

DISCUSSION

This report shows that the CD4 T-cell response, like the CD8 T-cell response, has three phases following viral infection: the activation and expansion phase occurs during the first week of infection, a death phase follows the second week of infection, and a memory phase commences after 1 month and lasts for at least 300 days postinfection.

The increase in number of virus-specific CD4 T cells seen during the first week after infection was most likely due to expansion of clones of cells rather than recruitment of cells to the spleen from other sites. All of the virus-specific CD4 T cells that could make IFN-γ were CD44hi (Fig. 6), and only CD44hi cells divided during this period (Fig. 3). At day 8 after infection, high frequencies of Th1 cells were formed, as indicated by three independent assays (IL-2 ELISPOT, IFN-γ ELISPOT, and intracellular IFN-γ staining). IFN-γ ELISPOT (Fig. 5) and intracellular IFN-γ staining (Fig. 6) both indicated that the frequency of LCMV NP309-328- or GP61-80-specific cells was 1/35 to 1/40 CD4 T cells or ∼1/20 activated CD4 T cells. Epitope analysis indicated that 5 × 105 cells per spleen were specific for GP61-80 and 1 × 105 were specific for NP309-328 at day 8 (Fig. 5). The total number of virus-specific IFN-γ-secreting CD4 T cells could be higher than that reported here, since only two I-Ab-restricted epitopes were used. The specificity of the CD4 response may include other epitopes which have not yet been identified.

There was a slight discrepancy in the IFN-γ ELISPOT estimate of virus-specific CD4 T cells as assessed by peptide stimulation of unenriched cells (1/30) versus virus stimulation of CD4-enriched cultures (1/162). This may represent differences in the level of antigen presentation during the in vitro culture period. Addition of peptide to the culture may have saturated the number of MHC II molecules presenting that particular peptide so that T cells were more efficiently stimulated. An alternative explanation is that some activated CD4 T cells were lost during the column enrichment, because the percentage of CD44hi cells decreased after enrichment compared with the percentage of CD4 T cells that were CD44hi before enrichment (data not shown). Given that most of the peptide-specific cells are in this CD44hi population, the use of column-purified CD4 T cells may give an underestimate of the actual frequency.

The death phase occurred during weeks 2 to 4 postinfection. Annexin V staining indicated that there were threefold more apoptotic CD4+ T cells during this period than in naive mice. The number of virus-specific IFN-γ- and IL-4-secreting CD4 cells dropped 87 to 95% during this period, mirroring what happens to the CD8 T-cell response (3, 6, 21, 25). Epitope analysis indicated that there was a similar drop in the number of NP309-328-specific CD4 T cells as there was for GP61-80-specific CD4 T cells, and both groups dropped ∼15-fold between days 8 and 150. Three- to fourfold more cells were specific for GP61-80 than for NP309-328 at day 8, and this ratio remained the same in immune mice.

The CD4 T-cell memory established after 1 month was stable for 6 to 10 months postinfection. This was seen by using single-cell cytokine ELISPOT assays, ELISA analysis, and intracellular IFN-γ staining, followed by flow cytometry quantitation. All of the virus-specific CD4 T cells that persisted in immune mice were CD44hi (Fig. 6) and CD69lo (data not shown), indicating that they were memory cells and not recently activated effector cells (CD69hi). Mice were also able to mount rapid secondary CD4 T-cell responses upon reinfection with LCMV. The longevity of CD4 T-cell memory was comparable to that of CD8 T cells, but was ∼10-fold lower in magnitude. The number of memory CD4 T cells may have been established by the size of the expansion phase, and since there was less expansion of CD4 cells than CD8 cells, the size of the memory pool was set lower. Studies in our laboratory (25) and in others (9) have shown that most (50 to 70%) of the activated CD8 T cells expanding after infection are specific for LCMV. The data shown in this report indicate that the expansion of LCMV-specific CD8 T cells is 35-fold greater than that of LCMV-specific CD4 T cells. As can be seen in Fig. 2B, even if all of the activated CD4 T cells expanding after infection were specific for LCMV, there would still be an approximately fivefold smaller burst size for the T-helper compartment.

Th2 responses showed a pattern of expansion, death, and memory that was similar to that of the Th1 response. After infection, there was an increase in IL-4-secreting cells, which reached a peak at day 8 with 4.5 × 104 IL-4-secreting CD4 T cells per spleen (Fig. 4C). ELISA analysis indicated that IL-10-producing CD4 T cells were also generated. There was a drop in the number of IL-4-secreting cells between days 8 and 30, which was followed by a period of memory in which elevated numbers of virus-specific cells were maintained. However, there were fewer IL-4-secreting CD4 cells than IFN-γ-secreting CD4 cells at all times. As can be seen in Fig. 4, the frequency of Th1 cells was at all times ≥2.0-fold higher than that of Th2 cells. That most of the T-helper response was composed of Th1 cells is not surprising given the antibody isotype distribution. Seventy percent of the T-helper-dependent antiviral IgG antibody made is of the IgG2a isotype (37). Th2 responses lead to IgG1 isotype switching, and following LCMV infection, a smaller component (10%) of the IgG response is of this class.

Many microbial infections lead to either Th1 or Th2 CD4 T-cell responses. Listeria monocytogenes, L. major, and Toxoplasma gondii infections tend to induce a Th1 response; helminth infections tend to elicit Th2 responses (28). In contrast, a mixture of both Th1 and Th2 cells developed following acute LCMV infection, and both Th1 and Th2 memory existed long after infection (Fig. 4 and 7). A mixed response in cytokine production following LCMV infection has also been reported by others (29). IL-12 and IFN-γ have been shown to be important molecules for initiating and propagating Th1 development. Since LCMV is macrophage tropic, the initial antiviral Th1 response may be driven by activated macrophages, which produce IL-12 (7, 34), and NK cells, which produce IFN-γ. However, this Th1 response does not preclude Th2 development, because large numbers of IL-4-secreting cells could also be found. Also, some CD4 Th0 cells which produce both IFN-γ and IL-4 during the early stage of infection could exist. There are several potential models of how Th2 responses could develop in acutely infected mice. The Th2 response might be driven by low levels of IL-4 that were produced by antigen-specific T cells after their initial activation. According to one model, if levels of IL-4 reach a threshold, Th2 differentiation is initiated, resulting in increased IL-4 production that leads to additional Th2-cell formation (1). It is possible that after LCMV infection, this threshold was reached and resulted in a pronounced Th2 response in addition to the Th1 response.

In another model of T-helper-cell development, antigen load and level of costimulation influence the Th1 or Th2 differentiation. Th0 cells which are exposed to high antigen levels and receive high costimulation develop into Th2 cells, whereas those exposed to lower antigen levels (or low-dose infections) and with lower levels of costimulation develop into Th1 cells (8, 16, 23, 31). Since acute viral infection is a dynamic process with high antigen loads at days 2 to 4 and then lower levels of antigen afterwards (21), conditions favoring the development of each T-helper subset may vary with time after infection. T-helper-cell differentiation might also be influenced by the type of costimulation. It has been reported that B7.1 and B7.2 differentially drive Th1 or Th2 development in an EAE model of T-helper-cell development (19) and in a NOD model of autoimmunity (22). A similar mechanism might occur during LCMV infection as levels of B7.1 and B7.2 increase in the spleen (unpublished observation). Blocking studies with anti-B7.1 or anti-B7.2 antibody treatment in mice infected with LCMV should reveal whether this mechanism is important for antiviral T-helper-cell development.

Memory CD4 cells contribute to viral clearance by facilitating neutralizing antibody generation and by helping CD8 CTLs proliferate. They may also play a direct role by secreting IFN-γ to inhibit viral replication and by activating macrophages so that they are refractory to viral infection and replication. This is one of the first studies quantitating the initial burst size of the CD4 T-cell response which demonstrates long-term Th1 and Th2 memory in an acute viral infection. Future investigations will address the activation requirements and rules that govern the maintenance of memory CD4 T cells. This information may lead to improved vaccination strategies for preventing viral infections.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

J.K.W. and M.S.A. contributed equally to this work.

We thank Rita J. Concepcion, Morry Hsu, Mary Kathryn Large, and Kaja Madhavi-Krishna for excellent technical assistance.

This work was supported by NIH grants AI 30048 and NS 21496 to R.A. M. S. Asano was supported by an Associate Investigator Award from the Department of Veteran Affairs and a postdoctoral fellowship from the National Multiple Sclerosis Society. M. Suresh was supported by a postdoctoral fellowship from the National Multiple Sclerosis Society.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abbas A K, Murphy K M, Sher A. Functional diversity of helper T lymphocytes. Nature. 1996;383:787–793. doi: 10.1038/383787a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ahmed R, Butler L D, Bhatti L. T4+ T helper cell function in vivo: differential requirement for induction of antiviral cytotoxic T-cell and antibody responses. J Virol. 1988;62:2102–2106. doi: 10.1128/jvi.62.6.2102-2106.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ahmed R, Gray D. Immunological memory and protective immunity: understanding their relation. Science. 1996;272:54–60. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5258.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ahmed R, Jamieson B D, Porter D D. Immune therapy of a persistent and disseminated viral infection. J Virol. 1987;61:3920–3929. doi: 10.1128/jvi.61.12.3920-3929.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ahmed R, Salmi A, Butler L D, Chiller J M, Oldstone M B A. Selection of genetic variants of lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus in spleens of persistently infected mice: role in suppression of cytotoxic T lymphocyte response and viral persistence. J Exp Med. 1984;160:521–540. doi: 10.1084/jem.160.2.521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Asano M S, Ahmed R. CD8 T cell memory in B cell-deficient mice. J Exp Med. 1996;183:2165–2174. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.5.2165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Biron C A, Gazzinelli R T. Effects of IL-12 on immune responses to microbial infections: a key mediator in regulating disease outcome. Curr Opin Immunol. 1995;7:485–496. doi: 10.1016/0952-7915(95)80093-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bretscher P A, Wei G, Menon J N, Bielefeldt-Ohmann H. Establishment of stable, cell-mediated immunity that makes “susceptible” mice resistant to Leishmania major. Science. 1992;257:539–542. doi: 10.1126/science.1636090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Butz E A, Bevan M J. Massive expansion of antigen-specific CD8+ T cells during an acute virus infection. Immunity. 1998;8:167–175. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80469-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cardin R D, Brooks J W, Sarawar S R, Doherty P C. Progressive loss of CD8+ T cell-mediated control of a γ-herpesvirus in the absence of CD4+ T cells. J Exp Med. 1996;184:863–871. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.3.863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen Y, Kuchroo V, Inobe J-I, Hafler D A, Weiner H L. Regulatory T cell clones induced by oral tolerance and suppression of autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Science. 1994;265:1237–1240. doi: 10.1126/science.7520605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cohen J. T cell shift: key to AIDS therapy? Science. 1993;262:175–176. doi: 10.1126/science.8211135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Czerkinsky C C, Nilsson L A, Nygren H, Ouchterlony O, Tarkowski A. A solid-phase enzyme-linked immunospot (ELISPOT) assay for enumeration of specific antibody-secreting cells. J Immunol Methods. 1983;65:109–121. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(83)90308-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ewing C, Topham D J, Doherty P C. Prevalence and activation phenotype of Sendai virus-specific CD4+ T cells. Virology. 1995;210:179–185. doi: 10.1006/viro.1995.1329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heinzel F P, Sadick M D, Holaday B J, Coffman R L, Locksley R M. Reciprocal expression of interferon γ or interleukin 4 during the resolution of progression of murine leishmaniasis: evidence for expansion of distinct helper T cell subsets. J Exp Med. 1989;169:59–72. doi: 10.1084/jem.169.1.59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hosken N A, Shibuya K, Heath A W, Murphy K W, O’Garra A. The effect of antigen dose on CD4+ T helper phenotype development in a T cell receptor-alpha beta-transgenic model. J Exp Med. 1995;182:1579–1584. doi: 10.1084/jem.182.5.1579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jennings S R, Bonneau R H, Smith P M, Wolcott R M, Chervenak R. CD4+ T lymphocytes are required for the generation of the primary but not the secondary CD8+ cytolytic T lymphocyte response to herpes simplex virus in C57BL/6 mice. Cell Immunol. 1991;133:234–252. doi: 10.1016/0008-8749(91)90194-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Khoury S J, Hancock W W, Weiner H L. Oral tolerance to myelin basic protein and natural recovery from experimental allergic encephalomyelitis are associated with down regulation of inflammatory cytokines and differential upregulation of transforming growth factor-B, interleukin 4, and prostaglandin E expression in the brain. J Exp Med. 1992;176:1355–1364. doi: 10.1084/jem.176.5.1355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kuchroo V K, Das M P, Brown J A, Ranger A M, Zamvil S S, Sobel R A, Weiner H L, Nabavi N, Glimcher L H. B7-1 and B7-2 costimulatory molecules activate differentially the Th1/Th2 developmental pathways: application to autoimmune disease therapy. Cell. 1995;80:707–718. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90349-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kuchroo V K, Martin C A, Greer J M, Ju S-T, Sobel R A, Dorf M E. Cytokines and adhesion molecules contribute to the ability of myelin proteolipid protein-specific T cell clones to mediate experimental allergic encephalomyelitis. J Immunol. 1993;151:4371–4382. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lau L L, Jamieson B D, Somasundaram T, Ahmed R. Cytotoxic T-cell memory without antigen. Nature. 1994;369:648–652. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lenschow D J, Ho S C, Sattar H, Rhee L, Gray G, Nabavi N, Herold K C, Bluestone J A. Differential effects of anti-B7-1 and anti-B7-2 monoclonal treatment on the development of diabetes in the nonobese diabetic mouse. J Exp Med. 1995;181:1145–1155. doi: 10.1084/jem.181.3.1145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lenschow D J, Walunas T L, Bluestone J A. CD28/B7 system of T cell costimulation. Annu Rev Immunol. 1996;14:233–258. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.14.1.233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Matloubian M, Concepcion R J, Ahmed R. CD4+ T cells are required to sustain CD8+ cytotoxic T-cell responses during chronic viral infection. J Virol. 1994;68:8056–8063. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.12.8056-8063.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Murali-Krishna K, Altman J D, Suresh M, Sourdive D, Zajac A, Miller J, Slansky J, Ahmed R. Counting antigen specific CD8 T cells: a re-evaluation of bystander activation during viral infection. Immunity. 1998;8:177–187. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80470-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.O’Garra A. Cytokines induce the development of functionally heterogeneous T helper cell subsets. Immunity. 1998;8:275–283. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80533-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Oxenius A, Bachmann M F, Ashton-Rickardt P G, Tonegawa S, Zinkernagel R M, Hengartner H. Presentation of endogenous viral proteins in association with major histocompatability complex class II: on the role of intracellular compartmentalization, invariant chain and the TAP transporter system. Eur J Immunol. 1995;25:3402–3411. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830251230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sher A, Coffman R L. Regulation of immunity to parasites by T cells and T cell-derived cytokines. Annu Rev Immunol. 1992;10:385–409. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.10.040192.002125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Su H C, Cousens L P, Fast L D, Slifka M K, Bungiro R D, Ahmed R, Biron C A. CD4+ and CD8+ T cell interactions in IFN-γ and IL-4 responses to viral infections: requirements for IL-2. J Immunol. 1998;160:5007–5017. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Taguchi T, McGhee J R, Coffman R L, Beagley K W, Eldridge J H, Takatsu K, Kiyono H. Detection of individual mouse spleen T cells producing IFN-γ and IL-5 using the enzyme-linked immunospot (ELISPOT) assay. J Immunol Methods. 1990;128:65–73. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(90)90464-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thompson C B. Distinct roles for costimulatory ligands B7-1 and B7-2 in T helper cell differentiation. Cell. 1995;81:979–982. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(05)80001-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Topham D J, Tripp R A, Hamilton-Easton A M, Sarawar S R, Doherty P C. Quantitative analysis of the influenza virus-specific CD4+ T cell memory in the absence of B cells and Ig. J Immunol. 1996;157:2947–2952. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tough D F, Sprent J. Turnover of naive- and memory-phenotype T cells. J Exp Med. 1994;179:1127–1135. doi: 10.1084/jem.179.4.1127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Trinchieri G. Interleukin-12: a proinflammatory cytokine with immunoregulatory functions that bridge innate resistance and antigen-specific adaptive immunity. Annu Rev Immunol. 1995;13:251–276. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.13.040195.001343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.van der Most R G, Murali-Krishna K, Whitton J L, Oseroff C, Alexander J, Southwood S, Sidney J, Chesnut R W, Sette A, Ahmed R. Identification of Db- and Kb-restricted subdominant cytotoxic T-cell responses in lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus-infected mice. Virology. 1998;240:158–167. doi: 10.1006/viro.1997.8934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Von Herrath M G, Yokoyama M, Dockter J, Oldstone M B A, Whitton J L. CD4-deficient mice have reduced levels of memory cytotoxic T lymphocytes after immunization and show diminished resistance to subsequent virus challenge. J Virol. 1996;70:1072–1079. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.2.1072-1079.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Whitmire J K, Slifka M K, Grewal I S, Flavell R A, Ahmed R. CD40 ligand-deficient mice generate a normal primary cytotoxic T-lymphocyte response but a defective humoral response to a viral infection. J Virol. 1996;70:8375–8381. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.12.8375-8381.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]