Abstract

Impostor phenomenon (IP) is described as a pattern typified by doubting one's accomplishments and a persistent fear of being exposed as a fraud. These feelings of self-doubt are pervasive along the medical education continuum, beginning with medical students where IP has been associated with emotional stress, physical exhaustion, depression, and anxiety. We, therefore, conducted an interactive workshop with first-year medical students to educate them about the manifesting patterns and risk factors of IP and strategies to mitigate these feelings. The 60-min workshop began with participants voluntarily completing the Young Imposter Scale (YIS) followed by an interactive presentation that reviewed the literature related to IP and its prevalence in medicine. Participants were then assigned to small groups where they discussed three cases of IP in academia and the medical profession. Medical school faculty acted as facilitators and utilized pre-designed prompt questions to stimulate discussion. Students re-convened for a large group report out, where each group shared main discussion points. The session ended with facilitators discussing IP mitigation strategies that can be implemented at the individual, peer, and institutional levels. Participants were also invited to complete a post-workshop evaluation. Fifty first-year medical students participated in the session. A total of 49 (96 %) completed the YIS and post-workshop evaluation. Nineteen (40 %) participants obtained scores on the YIS to indicate a positive finding of IP. The percentage of female medical students meeting the threshold for IP was significantly higher (84 %, n = 41 vs 16 %, n = 7) than male medical students. The workshop was effective at identifying IP and associated risk factors and providing mitigation strategies, with 95.8 % of participants agreeing or strongly agreeing. In qualitative feedback, participants reported that the workshop was “very interactive”, “provided strategies to manage impostor syndrome” and “helped me become more vulnerable with my peers.” This workshop provided a novel interactive and effective method to increase medical students' awareness about IP which can be employed as a strategy to enhance student's wellness.

Keywords: Impostor phenomenon, Medical students, Psychosocial, Mitigation

Highlights

-

•

Workshops related to imposter phenomenon were well received by first-year medical students.

-

•

The prevalence of imposter phenomenon was found to be higher in female medical students than in males.

-

•

Higher levels of imposter phenomenon were found in those identifying as Asian or Black/African American.

-

•

Mitigation strategies for imposter phenomenon were valued by medical students.

1. Introduction

Impostor phenomenon (IP), also commonly referred to as impostor syndrome or impostorism, describes high-achieving individuals who, despite their successes, fail to internalize their accomplishments and have persistent feelings of self-doubt and fear of being exposed as a fraud or imposter [1]. It is a phenomenon or experience, not a recognized psychiatric disorder. IP is not featured in the American Psychiatric Association's Diagnostic and Statistics Manual nor is it listed as a diagnosis in the International Classification of Diseases [2,3].. Impostorism is about an inability to accurately self-assess regarding performance, having diminished self-confidence, fear of failure, and achieving perfectionistic expectations [4]. First identified by psychologists Clance and Imes in 1978, IP was initially studied among high-achieving professional women, mostly identifying as White, but more research has documented these feelings of inadequacy among different genders, in people of color, in sexual minorities, and in many professional settings [1,5,6]. Notably, IP is common within the medical profession, with its impact being established at all levels of medical training, beginning with medical students, during transition to residency and even in senior physicians and faculty [7]. As a practicing physician, professional experiences such as unfavorable patient outcomes, patient complaints, competitiveness of grants, patient reviews, etc. Can lead to these increased feeling of IP [8]. A 2021 study by Rosenthal, et at. of 257 American medical students identified IP in 29 % of male medical students and 35 % of female medical students [9]. Other studies have shown similar prevalence among residents of different specialties [[10], [11], [12]]. For example, amongst family medicine residents, 24 % of male residents and 41 % of female residents expressed symptoms consistent with IP [13]. In studies involving physicians, increased thoughts of impostorism related to lower ratings of job performance can occur at any point in a physician career [8].

Impostorism interferes with a person's ability to accept and enjoy their abilities and achievements and has a negative impact on their psychological well-being. Intersecting feelings of low self-confidence, internalization of failures, and over-focusing on mistakes can lead to anxiety, depression, and burnout in the long term [14]. Additionally, research has demonstrated that leaders and team members with IP tendencies can unintentionally disrupt their team's productivity [15]. Thus, it is essential to increase medical students' awareness about IP and provide them with tools and support to enhance their wellness and performance within interprofessional teams.

This study uses a novel approach to pair an assessment of the prevalence of IP in first-year medical students with application of mitigation strategies while they experienced the early phases of medical training. An interactive workshop was implemented with the dual goal of educating these students about the manifesting patterns and risk factors of IP while also providing them with strategies to mitigate these feelings. Relationships between instrument scores and demographic parameters were also determined to identify attributes contributing to IP.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. IRB approval and consent process

This study's protocol was reviewed and approved with exempt status by the [removed for review] University Institutional Review Board (Protocol # 2021–477). The consent process was explained to the participants prior to the session via a class announcement and short oral presentation. It was described to the participants that taking part in the study was voluntary and had no impact on their educational program. There were no known risks for their participation and the information collected may not benefit them directly. Anonymous surveys were used, and participants were instructed not to complete any items that made them feel uncomfortable. Informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to the session.

2.2. Participants

Forty-nine first-year medical students at the [institution removed for review] class of 2025 participated in this study.

2.3. IP instrument

The Young Imposter Scale (YIS), developed by Dr. Valerie Young, was used to assess the presence or absence of impostor-like feelings [14,16]. This instrument has been used by multiple studies as a reliable tool for determining feeling of impostor phenomenon [[16], [17], [18], [19], [20], [21]]. The YIS is an abbreviated eight-item instrument that uses yes-or-no statements (e.g., Do you believe that other people are smarter and more capable than you?) (See Appendix A). Responding yes to five or more of these questions was considered a positive finding of IP. The YIS provided real-time individualized and private feedback to the participants by allowing them to tally their scores and determine their personal levels of IP. In addition, participants answered several demographic questions related to age, gender, and race/ethnicity.

2.4. Session design, context, and facilitation

The 60 min session was introduced into the Reflection, Integration, and Assessment (RIA) week at the end of the Fundamentals course, which takes place as the first basic science course in the Fall semester of year one of the curriculum. This course covers the foundational sciences, and is where students start to develop their studying habits, assessment-taking skills, sense of belonging, and professional identity. The placement of the session in the curriculum allowed the students to reflect on their experiences during this course where impostorism feelings may have developed and to provide mitigation strategies prior to their transition into the next course.

The session began with participants taking the YIS survey for up to 7 min duration. Following this, participants were invited to reflect on their own thoughts and experiences concerning IP by creating a word cloud as a group by answering “What is Impostor Syndrome.” The participants were asked to discuss their perspectives and reflections on both activities, the YIS and word cloud. This was followed by an interactive presentation that reviewed the literature related to IP, its prevalence in medicine, and evidence-based research on the effects of IP in medical students, residents, and attendings. The presentation also included a 4-min TED Talk video on IP [22]. Participants were then assigned to small groups where they discussed three cases of IP in academia and the medical profession (Appendix C). The curriculum at our medical school focuses on problem-based learning with clinical cases as one of the main drivers of learning. Therefore, cases were chosen and adapted to represent different stages of medical education that participants had experienced or could relate to in their future training [23,24]. The cases were adapted from Rivera et al., ‘s 2021 study which included cases describing scenarios of IP in a college junior, a medical student, and an attending physician [23,25]. Medical school faculty acted as facilitators and utilized pre-designed prompt questions to stimulate discussion. Prompt questions included “Has something like this ever happened to you and how did it make you feel?“; “What are some factors that contribute to this happening?“; “What could the institution, peers, or individuals do to improve this situation?” [17] Facilitators included a diverse group of faculty members ranging from junior and senior rank levels, male and female gender, and faculty of color. Following the small groups case discussions, students re-convened for a large group report out, where each group shared their main discussion points. The session ended with presenters discussing IP mitigation strategies that can be implemented at the individual, peer, and institutional levels.

2.5. Session evaluation

At the end of the session, participants were asked to complete the anonymous post-session evaluation form (Appendix B). This evaluation used items rated on a 5-point Likert scale.

(1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree) to evaluate the effectiveness of the session at meeting its stated objectives (Define impostor phenomenon and ways it can manifest; Identify risk factors associated with impostor phenomenon; and Describe strategies to overcome impostor phenomenon) and open-ended questions to elicit qualitative feedback. Participants were asked to write two action items they would commit to take to mitigate IP in the future.

2.6. Data analysis

Data analysis consisted of a mixed methods model. GraphPad Prism version 9.5.0 for Windows, GraphPad Software, Boston, Massachusetts was used for the statistical analysis. An unpaired students’ t-test was used to examine the differences in the scores of the YIS between genders and one-way ANOVA were used to assess the statistical significance of the data obtained, with a p-value less than 0.05 being considered as significant. Narrative responses were categorized by thematic analysis for common thematic topics as qualitative analysis.

3. Results

3.1. Participant demographics

A total of 48 students (98 % of the class) attended and consented to participate in the session including the YIS and post-session evaluation. There were similar numbers of male medical student versus female medical student participants (48 % and 52 %, respectively) (Table 1). The majority of the participants (71 %) were ≤24 years of age, and 29 % were between 25 and 29 years of age (Table 1). For ethnicity, participants identifying as white were 36.7 %, followed by Asian (28.6 %), Hispanic/Latinx (10.2 %), Other (10.2 %), Black/African American (8.2 %), and Multiracial (4.1 %) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of all participants (N = 48) who completed the YIS and post-session evaluation.

| Participants Demographics | ||

|---|---|---|

| N (%) | ||

| Gender | Male | 23 (48) |

| Female | 25 (52) | |

| Age | ≤24 | 34 (71) |

| 25–29 | 13 (27) | |

| 30–34 | 1 (2) | |

| Ethnicity | White | 18 (36.7) |

| Asian | 14 (28.6) | |

| Hispanic or Latinx | 5 (10.2) | |

| Black or African American | 4 (8.2) | |

| Multiracial | 2 (4.1) | |

| Other | 5 (10.2) | |

3.2. Prevalence of impostorism in year 1 medical students

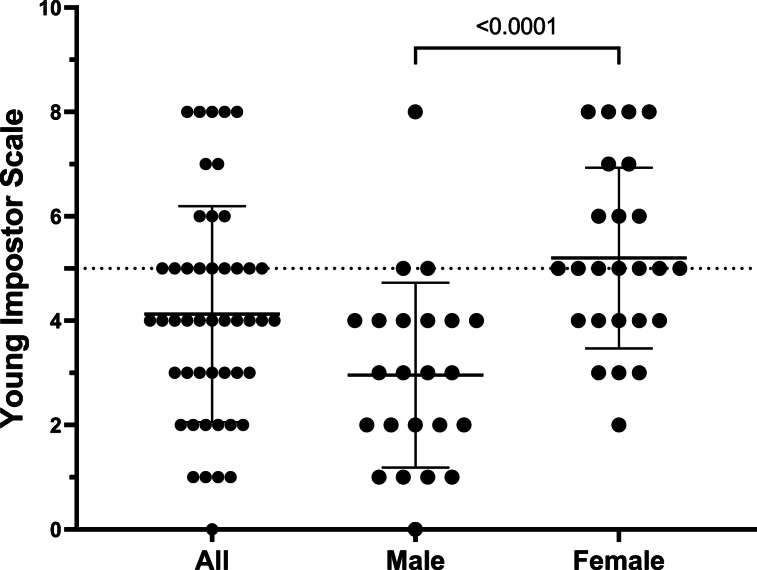

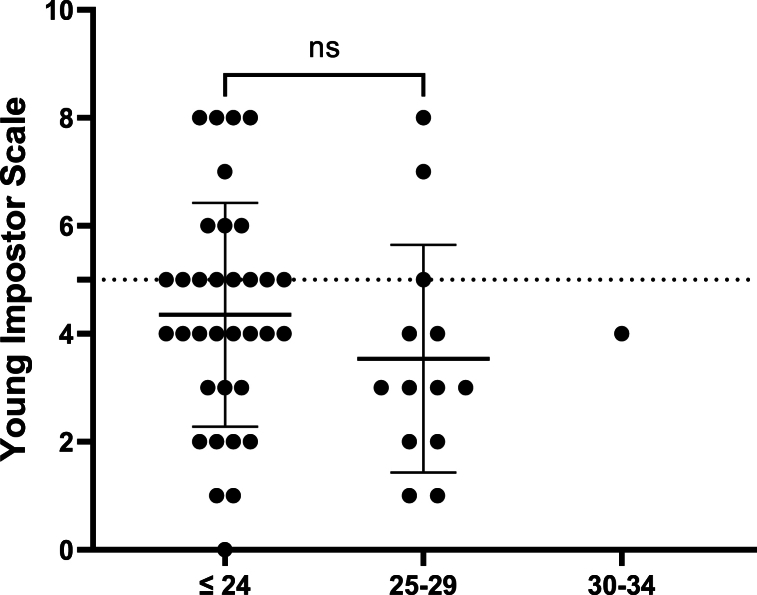

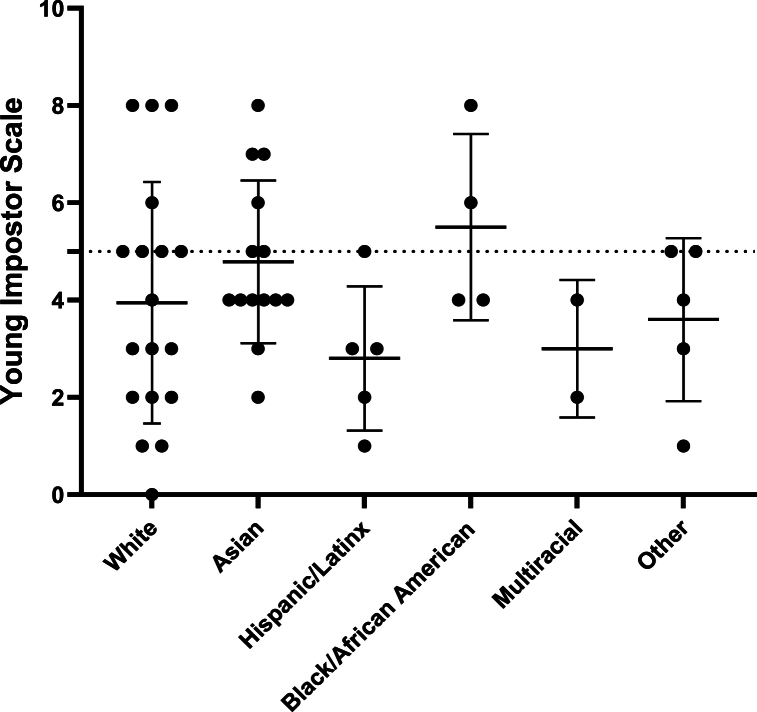

A score of 5 or higher was a positive finding for IP; lower scores indicated a lower potential for IP. The mean score for the YIS responses was 4.1 (2.1 SD) (Fig. 1). Impostorism was identified in 40 % of first-year medical students surveyed, with 16 % identifying as male and 84 % identifying as female (Fig. 1). The mean YIS score for male medical students [3.0 (1.8 SD)] was significantly lower than female medical students [ 5.2 (SD 1.7)], p < 0.001) (Fig. 1). Individuals in the age group of 24 or below had the highest scores with a mean YIS score of 4.4 (SD 2.1) with 33.3 % of all participants scoring at or above the threshold for IP at this age group (Fig. 2). For the 25–29 years of age group, the mean YIS score was 3.5 (SD 2.1), with a lower IP incidence of 6.25 %, which was not statistically significant (p = 0.4915) (Fig. 2). For participants identifying as white the mean YIS score was 3.9 (SD 2.5) with 16.7 % of participants scoring at or above threshold for this group, and for those identifying as Asian, the score increased to 4.8 (SD 1.7), with 12.5 % of the participants scoring at or above threshold (Fig. 3). The mean YIS score for the Hispanic/Latinx group was 2.8 (SD 1.5), for Black or African Americans was 5.5 (SD 1.9), for Multiracial was 3.0 (SD 1.4) and those identifying as Other was 3.6 (SD 1.7) (Fig. 3). Despite higher IP scores, there was a lower incidence of IP demonstrated in these groups as follows: Hispanic/Latinx (2.0 %), Black or African Americans (4.2 %) and Other (4.2 %). The p-value was calculated to be p = 0.2828, which was not statistically significant.

Fig. 1.

Young Imposter Scale (YIS) scores in first-year medical students and gender differences. The mean YIS score in the scatter plot is indicated by the solid line. The YIS threshold of 5 is depicted by the dotted line. N = 48 for all participants; 23 for male medical student and 25 for female medical student groups. p < 0.0001 by unpaired t-test.

Fig. 2.

Young Imposter Scale (YIS) scores in first-year medical students by age groups. The mean YIS score in the scatter plot is indicated by the solid line. The YIS threshold of 5 is depicted by the dotted line. N = 48 for all participants; 34 for ≤24, 13 for 25–29 and 1 for 30–34 years of age, respectively. p < 0.4915 by one-way ANOVA.

Fig. 3.

Young Imposter Scale (YIS) scores in first-year medical students by ethnicity. The mean YIS score in the scatter plot is indicated by the solid line. The YIS threshold of 5 is depicted by the dotted line. N = 48 for all participants; 18 for White, 14 for Asian, 4 for Black or African American, 2 for multiracial and 5 for other ethnicities, respectively. p=0.2828 by one-way ANOVA.

3.3. Post-session evaluation

After completing the session, 95.8 % of participants strongly agree or agree the workshop met its objectives, and 95.9 % of participants strongly agree or agree the case discussions fostered their learning of impostor syndrome and the presentation was informative and included useful resources (Table 2). Furthermore, 91.6 % of participants strongly agree or agree they felt comfortable recognizing impostor syndrome in themselves, and 91.7 % will apply information learned to address impostor syndrome (Table 2).

Table 2.

Impostor phenomenon post-session likert-scale survey results (N = 48).

| Question | N (%) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strongly Agree | Agree | Neutral | Disagree | Strongly Disagree | |

| Workshop met objectives. | 36 (75.0) | 10 (20.8) | 2 (4.2) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Presentation was informative and included useful resources. | 33 (68.8) | 13 (27.1) | 2 (4.2) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Case discussions fostered my learning of Impostor Syndrome. | 33 (68.8) | 13 (27.1) | 1 (2.1) | 1 (2.1) | 0 (0) |

| This was an effective intervention to promote medical students' wellness. | 29 (60.4) | 14 (29.2) | 2 (4.2) | 3 (6.3) | 0 (0) |

| The facilitators were helpful in fostering discussions. | 33 (68.8) | 12 (25.0) | 2 (4.2) | 1 (1) | 0 (0) |

| I feel comfortable recognizing impostor syndrome in myself. | 28 (58.3) | 16 (33.3) | 3 (6.3) | 1 (2.1) | 0 (0) |

| I feel comfortable recognizing impostor syndrome in my colleagues. | 23 (47.9) | 16 (33.3) | 6 (12.5) | 3 (6.3) | 0 (0) |

| I feel comfortable discussing impostor syndrome with my colleagues. | 31 (64.6) | 14 (29.2) | 1 (2.1) | 2 (4.2) | 0 (0) |

| I know what to do next if myself or my colleague has impostor syndrome. | 23 (47.9) | 17 (35.4) | 4 (8.3) | 4 (8.3) | 0 (0) |

| I will apply information learned today to address impostor syndrome. | 26 (54.2) | 18 (37.5) | 3 (6.3) | 1 (2.1) | 0 (0) |

In response to the prompt asking participants what two things they would do as a result of the session, they noted they will share their feelings more often with peers and mentors when having IP feelings as mitigation strategy and they will foster discussions about IP, share resources and encourage others to feel that they belong (Table 3). Participants also noted they will also learn to better accept positive feedback and practice self-reflections (Table 3). Numerous participants appreciated the open discussion, case studies and interactive format of the session. Participants noted the session was well timed at the end of the challenging fundamentals block of the curriculum. When asked what they liked the most about the session, one participant started “I liked that the timing of this workshop was during a period where all of us could relate significantly.” Areas of improvement identified through free responses included allowing more time for discussions, and for faculty to share their experiences with IP. Also, participants suggested additional exploration of IP mitigation strategies.

Table 3.

Impostor phenomenon post-session evaluation free responses.

| question | free-response answers |

|---|---|

| Please name two things that you will do/change as a result of this workshop: | “Writing a list of all my accomplishments, talk to my peers and mentors when I am having these feelings.” “I want to become more vulnerable to other students about my feelings and be willing to learn from my peers by asking questions and sharing resources. Encouraging others to feel as if they belong.” “Have more confidence in my abilities. Talk with peers about doubts they are having so that they know they are not alone. I will foster discussions with classmates about impostor syndrome.” “Learn to recognize when I am being overly critical of myself. Learn to better accept positive feedback.” “I will be kinder to myself and be more open with my peers. I would like to be better at acknowledging my successes first before my failures.” “I will try to be more transparent about my own journey so that my peers know they are not alone. I will practice self-reflection and watch out for signs of impostor syndrome within myself.” |

| What did you like best about the workshop? | “Learning about impostor syndrome and being able to identify it in myself.” “I liked how interactive it was and I liked that the timing of this workshop was during a period where all of us could relate significantly.” “I enjoyed the case studies and discussions that I had with my group.” “Open nature of discussion.” “The case studies.” “Being given strategies to manage impostor syndrome.” |

| What can we improve about the workshop? | “Allow us to have more time for discussion.” “Giving an overview of the session beforehand to prime us to be vulnerable with our classmates.” “More sharing from faculty and doctors.” “Explore dealing with mitigation a bit more.” |

Barriers for implementation of mitigation strategies from the session included those on the individual level such as ingrained thought processes (24 % of responses) and self-doubt (16 % of responses) (Table 4). On a peer level, lack of support from others (8 % of responses) and lack of openness with peers (16 % of responses) were noted barriers (Table 4). Finally, on the institutional level barriers included difficulty to change institutional culture (8 % of responses) and daily workload pressures (16 % of responses) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Barriers identified by session participants to mitigate impostor phenomenon.

| Barriers by Level | % of responses | representative quote |

|---|---|---|

| Individual level | ||

|

Ingrained thought process Self-doubt |

24 16 |

“Changing patterns of thought is difficult and takes a lot of consistent work.” “Doubting my abilities and myself.” |

| Peer Level | ||

|

Lack of support from others Lack of openness with peers |

8 16 |

“Cooperation from some of my peers.” “The willingness of my colleagues to express their own vulnerabilities.” |

| institutional level | ||

|

Difficulty to change institutional culture Time and workload pressure |

8 16 |

“Lack of other people (i.e., higher up faculty) not understanding my impostor syndrome.” “The high expectations set before us and the massive amounts of knowledge to learn in such a short time.” |

4. Discussion

This study evaluated the prevalence of IP among first-year medical students, finding that nearly 40 % of all students in our sample scored equal to or above a 5 on the Young Imposter Scale (YIS), indicating the presence of impostorism. We used the YIS to examine IP feelings among medical students at the completion of the first 12-week block of their pre-clerkship education because this was a challenging and demanding period for medical students considering this course represented their first exposure to a rigorous medical school curriculum and it allowed the opportunity to provide mitigation strategies prior to their first major transition to a new block in medical school where feelings of IP may be heightened.

The findings of our study are consistent with results from prior studies that also evaluated IP prevalence in medical students. Houseknecht et al. found that 54 % of matriculating medical students exhibited scores above the cutoff for impostorism, which significantly increased at the end of the third year and continued at the end of the fourth year [26]. Similarly, in another study, 87 % of the first-year medical students reported high or very high degrees of IP [9]. Among these students the IP scores at the end of the school year were significantly higher than at the beginning of the year [9]. Furthermore an increase in both incidence and degree of IP with progression through medical school has been found to be correlated with emotional distress [9]. These findings along with the data from our study highlight the opportunities for early interventions in the medical curricula to help learners identify and mitigate IP in order to minimize the negative impact on students' outcomes both academically and from the perspective of mental health wellness.

IP has historically had widespread impacts on other health care professionals in training. Early studies in the nineties found rates of IP for dental, nursing and pharmacy students were to be as high as 30 % [27]. Within each of these programs, significant associations were found between IP and psychological distress in health professional students [27]. More recent studies in first-year dental students found 86 % of students reported feelings of IP r and 51 % were classified as frequent or intense impostors on the Clance Impostor Phenomenon Scale [28]. In pharmacy and nursing students, moderate to high levels of IP feelings have been recently found [29,30].

As medical educators, recognizing the implications of a high prevalence of IP among students is important for maintaining an environment of psychological safety. IP has been demonstrated to be a predictor of mental health in that it has been positively correlated with burnout components, anxiety and lack of self-esteem, depression, psychological distress, and general dissatisfaction with life [6,27,[31], [32], [33]]. Our study data highlights the already existing prevalence of IP in medical school students and underscores the importance of developing targeted strategies to help them recognize and mitigate these feelings, in order to prevent negative impacts on their future careers as physicians.

In terms of gender effects, our study reports the percentage of female medical students (84 %) meeting the threshold for IP was considerably higher than male medical students (16 %) (Fig. 1). Similar trends are published in another study of medical students where 50 % of female medical students and 25 % of male medical students demonstrated significant impostorism.31A recent systematic review on IP has shown that sixteen studies reported statistically significant higher rates of IP feeling in females compared to males. In contrast, the same report also reveals seventeen studies where gender effects are not significant. This evidence suggests that while IP is more common in females, males are also affected by it [1]. Females may be more aware of societal stereotypes that can trigger feelings of impostorism [34]. For example, in the stereotype of leaders possessing predominantly masculine traits, females often are depicted as having a less natural fit for leadership positions or lacking leadership qualities, which causes them to feel insecure about pursuing such roles. Research also suggests that females cope differently with their impostor feelings resulting in different rates of IP [35,36].

Similarly, certain ethnic groups are stereotyped as being unintelligent, and underachieving, which suggests that the portrayal of those groups in society might play an important role in triggering IP feelings [37]. In fact, eleven studies have demonstrated that IP is common among African American, Asian, and Hispanic/Latinx college students and that impostor feelings are positively correlated with depression and anxiety [1]. Various factors may predispose minorities to IP besides negative stereotypes including lack of financial aid, being the first in their families to pursue advanced education, lack on mentorship and racial discrimination. Evidence suggests that students who reported being racially discriminated against were more likely to feel like impostors [38,39]. Our assessment reports the groups that make up the majority of the medical students surveyed – Asians and Whites – meet the threshold for IP (N = 14), compared to the other races combined (N = 5), indicating that all ethnic groups may be affected by IP.

5. Conclusions

IP is often studied as an individualistic approach, where researchers have gathered information from the individuals with IP to understand the root causes. Many proposed solutions and strategies for addressing impostor feelings focus on providing approaches to the specific person with impostorism. Such strategies often involve clinical therapy, coaching on confidence training, and conquering impostor feelings [40,41]. Although the phenomenon manifests at the level of the individual, social context is of great importance in shaping how an individual feels about themselves. Therefore, to fully mitigate IP it is important to complement previous strategies and consider the role of society and culture, organizations and institutions, and interpersonal relationships. We propose a call to action to reframe impostorism as an experience that should not be a barrier to flourishing in the learning environment. This requires a significant emphasis on positive coping mechanisms to address IP feelings not only at the individual level, but also at the institutional level through diversity and inclusion initiatives that promote a sense of belonging for diverse learners. Our future studies include development of a toolkit for mitigation of IP and for institutional support related to impostorism.

Strengths and limitations

The strengths of this study include the ability to easily apply a similar session with medical students at other medical schools in the United States. According to the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) 2023 FACTS: Applicants and Matriculants Data for U.S. MD-Granting Medical School, 44.2 % of matriculants were men and 55.4 % were women [42]. Our study population exhibited similar gender distributions, suggesting that the this study could be replicated at other medical schools in the United States. Additionally, the response rate for the instruments implemented in the study was high, with 98 % of the medical students in the class completing the YIS and the post-session evaluation.

Limitations of this study include that the participants surveyed were medical students at one United States medical school with a small sample size. However, the demographics of the participants are representative to other programs in the United States. Moreover, the self-administered YIS, and survey-based evaluations introduced social desirability biases. We did try to minimize this bias with the anonymous nature of the survey. In addition, prevalence estimates reported in our study are similar to those presented by other authors in this area of study [1]. Finally, the study was not able to account for personality, stress, and depression factors that have previously been associated with IP. These measurements would have added significant time to survey completion and limiting the implementation of the workshop.

Ethics declaration

This study was reviewed and approved by the University Institutional Review Board, with the approval number: Protocol # 2021–477.

All participants/patients (or their proxies/legal guardians) provided informed consent to participate in the study.

Data availability statement

Data is included in the article, supplementary materials, and/or is referenced in the article.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Algevis Wrench: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Conceptualization. Maria Padilla: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Conceptualization. Chasity O'Malley: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Conceptualization. Arkene Levy: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Methodology, Formal analysis, Conceptualization.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Appendix A.

The Young Imposter Scale (YIS).

-

1.

Do you secretly worry that others will find out you're not as bright and capable as they think you are?

-

2.

Do you sometimes shy away from challenges because of a nagging self-doubt?

-

3.

Do you tend to chalk your accomplishments up to being a “fluke,” “no big deal” or the fact that people just “like” you?

-

4.

Do you hate making a mistake, being less than fully prepared, or not doing things perfectly?

-

5.

Do you tend to feel crushed even by constructive criticism, seeing it as evidence of your “ineptness?”

-

6.

When you do succeed, do you think “Phew, I fooled them this time, but I may not be so lucky next time?”

-

7.

Do you believe that other people (students, colleagues, competitors) are smarter and more capable than you?

-

8.

Do you live in fear of being found out, discovered, or unmasked?

Appendix B.

Post-session evaluation.

Please rate the following statements.

| Statement | Strongly disagree | Disagree | Neutral | Agree | Strongly agree |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Workshop met objectives. | |||||

| Presentation was informative and include useful resources. | |||||

| Case discussions fostered my learning of Imposter Syndrome | |||||

| This was an effective intervention to promote medical students' wellness. | |||||

| The facilitators were helpful in fostering discussions. | |||||

| I feel comfortable recognizing imposter syndrome in myself. | |||||

| I feel comfortable recognizing imposter syndrome in my colleagues. | |||||

| I feel comfortable discussing imposter syndrome with my colleagues. | |||||

| I know what to do next if myself or my colleague has imposter syndrome. | |||||

| I will apply information learned today to address imposter syndrome. |

Please name two things that you will do/change as a result of this workshop.

1.

2.

What do you see as potential barriers to applying what you have learned?

What did you like best about the workshop?

What can we improve about the workshop?

Appendix C.

Imposter Phenomenon Case Studies.

Case 1: Medical Student.

A 24-year-old male with a medical history significant for chronic indecision presents with three weeks of progressive stress. The patient, a medical student who recently began his third year of medical school, has developed confusing worry during his rotations. During this time, he has had close contact with other medical students. He reports that he feels well-prepared for his role as a medical student. However, he concedes feelings of stress whenever he forgets an aspect of the physical exam or history of present illness. The patient rationalizes that this is normal for medical students on their first rotation but wonders how he will develop the knowledge and skills to be an effective physician. He remarks that “there is so much to know.”

He admits to weaknesses, such as difficulty utilizing knowledge garnered from the first two years of medical school in a clinically significant way, despite mastery of that knowledge. When questioned about his ability to cope during his rotation, he reports specific tense patient encounters but easily shrugs them off as “outside the scope” of what is expected of him. He understands that all medical students “deal with these things” and reports being able to “step away” from the situation if necessary.

Upon examination, the patient does not appear to be in any significant distress. He displays an adequate fund of knowledge. He is oriented to person, place, and time. He can effectively follow commands. He achieves a three out of three on recall in the clinic when prompted by the attending physician.

Based on history of present illness, the patient was diagnosed with Imposter Syndrome following diagnostic feedback administered by the attending physician. This was met with resistance. The patient denied “imposter” feelings and left against medical advice.

Outcome: The patient later returned seeking formal treatment following a confirmatory second opinion by an outside provider. Cognitive behavior therapy was initiated promptly.

Questions for discussion.

-

1.

Has something like this ever happened to you and how did it make you feel?

-

2.

What are some factors that contribute to this happening?

-

3.

What could the institution, peers, or individuals do to improve this situation?

Case 2: College Junior.

You are a 19-year-old female, college junior at a large state school sitting in a waiting room for an appointment with a campus career counselor to discuss applying to medical school. You have transferred from a community college and have been involved in multiple service projects for the largely underserved neighborhood where you are from. You meet a female student who has been working in a research lab and also considering applying to medical school. You start to wonder if you should even apply to medical school.

Questions for discussion.

-

1.

Has something like this ever happened to you and how did it make you feel?

-

2.

What are some factors that contribute to this happening?

-

3.

What could the institution, peers, or individuals do to improve this situation?

Case 3: Attending.

You are a new attending who recently started their first job. You recently graduated from your fellowship a few short months before in a field where you are an underrepresented minority. You were hired for a particular niche procedure with which you had developed exceptional skill. During a recent day, you were able to accomplish a technically difficult procedure, which was praised by the other physicians. However, you felt that you “just got lucky” and do not have the skills to perform your job well and confess this to another attending at a different institution.

Questions for discussion.

-

1.

Has something similar to this ever happened to you in a work/school environment and how did it make you feel?

-

2.

What are some factors that contribute to this happening?

-

3.

What could the institution, peers, or individuals do to improve this situation?

References

- 1.Bravata D.M., Watts S.A., Keefer A.L., et al. Prevalence, predictors, and treatment of impostor syndrome: a systematic review. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2020;35(4):1252–1275. doi: 10.1007/S11606-019-05364-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.American Psychiatric Association . 2013. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Published online May 22. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.International Classification of Diseases (ICD). Accessed October 3, 2023. https://www.who.int/standards/classifications/classification-of-diseases.

- 4.de Vries M.F.R. The dangers of feeling like a fake. Harv Bus Rev. Published online. 2005:108–159. https://hbr.org/2005/09/the-dangers-of-feeling-like-a-fake [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clance P.R., Imes S.A. The imposter phenomenon in high achieving women: dynamics and therapeutic intervention. Psychother. Theory Res. Pract. 1978;15(3):241–247. doi: 10.1037/H0086006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clance P.R., O'Toole M.A. The imposter phenomenon: an internal barrier to empowerment and achievement. Women Ther. 1987;6(3):51–64. doi: 10.1300/J015V06N03_05. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gottlieb M., Chung A., Battaglioli N., Sebok-Syer S.S., Kalantari A. Impostor syndrome among physicians and physicians in training: a scoping review. Med. Educ. 2020;54(2):116–124. doi: 10.1111/MEDU.13956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ladonna K.A., Ginsburg S., Watling C. “Rising to the level of your incompetence”: what physicians' self-assessment of their performance reveals about the imposter syndrome in medicine. Acad. Med. 2018;93(5):763–768. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000002046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rosenthal S., Schlussel Y., Yaden M.B., et al. Persistent impostor phenomenon is associated with distress in medical students. Fam. Med. 2021;53(2):118–122. doi: 10.22454/FAMMED.2021.799997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bhama A.R., Ritz E.M., Anand R.J., et al. Imposter syndrome in surgical trainees: clance imposter phenomenon scale assessment in general surgery residents. J. Am. Coll. Surg. 2021;233(5):633–638. doi: 10.1016/J.JAMCOLLSURG.2021.07.681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Legassie J., Zibrowski E.M., Goldszmidt M.A. Measuring resident well-being: impostorism and burnout syndrome in residency. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2008;23(7):1090–1094. doi: 10.1007/S11606-008-0536-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Regan P.A., Shumaker K., Kirby J.S. Impostor syndrome in United States dermatology residents. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2020;83(2):631–633. doi: 10.1016/J.JAAD.2019.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Oriel K., Mary Plane B., Mundt M. Family medicine residents and the impostor phenomenon. Fam. Med. 2004;36(4):248–252. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Villwock J.A., Sobin L.B., Koester L.A., Harris T.M. Impostor syndrome and burnout among American medical students: a pilot study. Int. J. Med. Educ. 2016;7:364. doi: 10.5116/IJME.5801.EAC4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Haney T.S., Birkholz L., Rutledge C. A workshop for addressing the impact of the imposter syndrome on clinical nurse specialists. Clin. Nurse Spec. 2018;32(4):189–194. doi: 10.1097/NUR.0000000000000386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ogunyemi D., Lee T., Ma M., Osuma A., Eghbali M., Bouri N. Improving wellness: defeating Impostor syndrome in medical education using an interactive reflective workshop. PLoS One. 2022;17(8) doi: 10.1371/JOURNAL.PONE.0272496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schmulian D., Lucia Campus S., Schmulian D.L., Redgen W., Fleming J. Impostor syndrome and compassion fatigue among graduate allied health students: a pilot study impostor syndrome and compassion fatigue focus on health professional education: a. Multi-Professional J. 2020;21(3):2020. doi: 10.3316/INFORMIT.947933797950458. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kaur T., Jain N. Relationship between impostor phenomenon and personality traits: a study on undergraduate students. Journal of Positive School Psychology. 2022;6(11):734–746. https://www.journalppw.com/index.php/jpsp/article/view/14030 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alrayyes S., Dar U.F., Alrayes M., Alghutayghit A., Alrayyes N. Burnout and imposter syndrome among Saudi young adults: the strings in the puppet show of psychological morbidity. Saudi Med. J. 2020;41(2):189. doi: 10.15537/SMJ.2020.2.24841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Khan M.N.A., Miah M.S.U., Shahjalal M., Sarwar T Bin, Rokon M.S. Predicting young imposter syndrome using ensemble learning. Complexity. 2022:2022. doi: 10.1155/2022/8306473. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Appleby R., Evola M., Royal K. Impostor phenomenon in veterinary medicine. Education in the Health Professions. 2020;3(3):105. doi: 10.4103/EHP.EHP_17_20. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Elizabeth Cox: What is imposter syndrome and how can you combat it? | TED Talk. Accessed October 3, 2023. https://www.ted.com/talks/elizabeth_cox_what_is_imposter_syndrome_and_how_can_you_combat_it.

- 23.Rivera N., Feldman E.A., Augustin D.A., Caceres W., Gans H.A., Blankenburg R. Do I belong here? Confronting imposter syndrome at an individual, peer, and institutional level in health professionals. MedEdPORTAL. 2021;17 doi: 10.15766/MEP_2374-8265.11166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Imposter Syndrome in a Medical Student: A Case Report. Accessed November 8, 2023. https://opmed.doximity.com/articles/imposter-syndrome-in-a-medical-student-a-case-report?_csrf_attempted=yes.

- 25.Imposter Syndrome in a Medical Student: A Case Report. Accessed October 3, 2023. https://opmed.doximity.com/articles/imposter-syndrome-in-a-medical-student-a-case-report?_csrf_attempted=yes.

- 26.Houseknecht V.E., Roman B., Stolfi A., Borges N.J. A longitudinal assessment of professional identity, wellness, imposter phenomenon, and calling to medicine among medical students. Med Sci Educ. 2019;29(2) doi: 10.1007/S40670-019-00718-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Henning K., Ey S., Shaw D. Perfectionism, the imposter phenomenon and psychological adjustment in medical, dental, nursing and pharmacy students. Med. Educ. 1998;32(5):456–464. doi: 10.1046/J.1365-2923.1998.00234.X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pastan C.D.B., Mc Donough A.L., Finkelman M., Daniels J.C. Evaluation of mindfulness practice in mitigating impostor feelings in dental students. J. Dent. Educ. 2022;86(11):1513–1520. doi: 10.1002/JDD.12965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Boyle J., Malcom D.R., Barker A., Gill R., Lloyd M., Bonenfant S. Assessment of impostor phenomenon in student pharmacists and faculty at two doctor of pharmacy programs. Am. J. Pharmaceut. Educ. 2022;86(1):21–27. doi: 10.5688/AJPE8474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Peng Y., Xiao S.W., Tu H., et al. The impostor phenomenon among nursing students and nurses: a scoping review. Front. Psychol. 2022;13 doi: 10.3389/FPSYG.2022.809031/BIBTEX. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Villwock J.A., Sobin L.B., Koester L.A., Harris T.M. Impostor syndrome and burnout among American medical students: a pilot study. Int. J. Med. Educ. 2016;7:364. doi: 10.5116/IJME.5801.EAC4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sonnak C., Towell T. The impostor phenomenon in British university students: relationships between self-esteem, mental health, parental rearing style and socioeconomic status. Pers. Indiv. Differ. 2001;31(6):863–874. doi: 10.1016/S0191-8869(00)00184-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McGregor L.N., Gee D.E., Posey K.E. I feel like a fraud and it depresses me: the relation between the imposter phenomenon and depression. Soc. Behav. Pers. 2008;36(1):43–48. doi: 10.2224/SBP.2008.36.1.43. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cokley K., Awad G., Smith L., et al. The roles of gender stigma consciousness, impostor phenomenon and academic self-concept in the academic outcomes of women and men. Sex. Roles. 2015;73(9–10):414–426. doi: 10.1007/S11199-015-0516-7/FIGURES/5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Powell G.N., Butterfield D.A., Parent J.D. Gender and managerial stereotypes: have the times changed? Southern Management Association. 2002;28(2):177–193. doi: 10.1177/014920630202800203. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hutchins H.M., Rainbolt H. What triggers imposter phenomenon among academic faculty? A critical incident study exploring antecedents, coping, and development opportunities. Hum. Resour. Dev. Int. 2017;20(3):194–214. doi: 10.1080/13678868.2016.1248205. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Reyna C. Lazy, dumb, or industrious: when stereotypes convey attribution information in the classroom. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 2000;12(1):85–110. doi: 10.1023/A:1009037101170/METRICS. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cokley K., Smith L., Bernard D., et al. Impostor feelings as a moderator and mediator of the relationship between perceived discrimination and mental health among racial/ethnic minority college students. J. Counsel. Psychol. 2017;64(2):141–154. doi: 10.1037/COU0000198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bernard D.L., Hoggard L.S., Neblett E.W. Racial discrimination, racial identity, and impostor phenomenon: a profile approach. Cult. Divers Ethnic Minor. Psychol. 2018;24(1):51–61. doi: 10.1037/CDP0000161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dickerson D. How I overcame impostor syndrome after leaving academia. Nature. 2019;574(7779):588. doi: 10.1038/D41586-019-03036-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zanchetta M., Junker S., Wolf A.M., Traut-Mattausch E. “Overcoming the fear that haunts your success” – the effectiveness of interventions for reducing the impostor phenomenon. Front. Psychol. 2020;11 doi: 10.3389/FPSYG.2020.00405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Association of American Medical Colleges Table A-7.2: Applicants, first-time Applicants, acceptees, and matriculants to U.S. MD-granting medical schools by gender, 2014-2015 through 2023-2024. 2023 https://www.aamc.org/media/9576/download?attachment Published online. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data is included in the article, supplementary materials, and/or is referenced in the article.