Abstract

Background

Online patient education materials (OPEMs) are an increasingly popular resource for women seeking information about breast cancer. The AMA recommends written patient material to be at or below a 6th grade level to meet the general public's health literacy. Metrics such as quality, understandability, and actionability also heavily influence the usability of health information, and thus should be evaluated alongside readability.

Purpose

A systematic review and meta-analysis was conducted to determine: 1) Average readability scores and reporting methodologies of breast cancer readability studies; and 2) Inclusion frequency of additional health literacy-associated metrics.

Materials and methods

A registered systematic review and meta-analysis was conducted in Ovid MEDLINE, Web of Science, Embase.com, CENTRAL via Ovid, and ClinicalTrials.gov in June 2022 in adherence with the PRISMA 2020 statement. Eligible studies performed readability analyses on English-language breast cancer-related OPEMs. Study characteristics, readability data, and reporting of non-readability health literacy metrics were extracted. Meta-analysis estimates were derived from generalized linear mixed modeling.

Results

The meta-analysis included 30 studies yielding 4462 OPEMs. Overall, average readability was 11.81 (95% CI [11.14, 12.49]), with a significant difference (p < 0.001) when grouped by OPEM categories. Commercial organizations had the highest average readability at 12.2 [11.3,13.0]; non-profit organizations had one of the lowest at 11.3 [10.6,12.0]. Readability also varied by index, with New Fog, Lexile, and FORCAST having the lowest average scores (9.4 [8.6, 10.3], 10.4 [10.0, 10.8], and 10.7 [10.2, 11.1], respectively). Only 57% of studies calculated average readability with more than two indices. Only 60% of studies assessed other OPEM metrics associated with health literacy.

Conclusion

Average readability of breast cancer OPEMs is nearly double the AMA's recommended 6th grade level. Readability and other health literacy-associated metrics are inconsistently reported in the current literature. Standardization of future readability studies, with a focus on holistic evaluation of patient materials, may aid shared decision-making and be critical to increased screening rates and breast cancer awareness.

Keywords: Health literacy, Patient education, Quality, Mammography, Systematic review, Meta-analysis

Highlights

-

•

Average readability was 11.81, twice the recommended AMA 6th grade reading level.

-

•

Readability studies measure and report readability with variable methodologies.

-

•

Many readability studies (40%) do not measure additional health literacy metrics.

-

•

Standardizing readability studies may improve evaluation and usability of OPEMs.

1. Introduction

Patients are increasingly turning to the Internet for health-related information, with one national survey reporting 72% of Internet users having looked online for health information over the previous year [1]. Approximately 8 in 10 of these online queries begin at a search engine such as Google, Bing, or Yahoo [1], and lead to the accessing of online patient education materials (OPEMs). OPEMs are any Internet-based article with which patients interact to learn about a health-related topic, often published by a wide variety of organizations, ranging from academic medical centers to national non-profits. To be appropriate for the general public, the American Medical Association (AMA) recommends that OPEMs be written at or below a sixth-grade reading level [2].

Readability of OPEMs related to breast cancer has been a popular area of investigation, with studies examining materials pertaining to all parts of the patient experience, including risk assessment, screening, diagnosis, and treatment [[3], [4], [5], [6], [7]]. Additional interest had been driven by federal dense breast legislation and its implications for new materials communicating important information about a patient's screening risk [[8], [9], [10], [11]]. Across the board, reading grade levels of breast cancer OPEMs have been found to be much higher than the AMA recommended sixth-grade level, echoing findings in orthopedics and dermatology [12,13]. Furthermore, readability study methodology varies greatly, with studies using as few as one index [14] to measure readability to as many as 12 [15]. Since some indices use only one variable (such as the number of single-syllable words) to output a readability score while others use multiple, this practice can result in inconsistent reading grade levels for a single analyzed text (Table 1).

Table 1.

Readability indices: variables, text sample size, formula, and citation.

| Index | Variables | Sample Size | Formula | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Automated Readability Index (ARI) | # characters, # words, # sentences | N/A | [56] | |

| Coleman Liau Index (CLI) | # letters (L), # sentences (S) | 100 words | 0.0588L – 0.296S–15.8 | [67] |

| Dale-Chall | # difficult words (words not on list of 3000 familiar words), # words, # sentences | N/A | [68] | |

| Flesch Kincaid Grade Level (FKGL) | # syllables, # words, # sentences | N/A | [55] | |

| FORCAST | # single-syllable words (N) | 150 words | [57] | |

| Fry | # syllables (X), # sentences (Y) | 100 words | X and Y plotted on the Fry readability graph. | [69] |

| Gunning Fog (GF) | # words, # complex words (three or more syllables), # sentences | N/A | [70] | |

| Linsear Write | # words less than three syllables (nwsy<3), # words three or more syllables (nwsy>=3), # words (nw), # sentences (nst) | 100 words | [71] | |

| New Fog Count (NFC) | # words less than three syllables (nwsy<3), # words three or more syllables (nwsy>=3), # of sentences (nst) | N/A | [55] | |

| Raygor | # words with six or more letters (X), # sentences (Y) | 100 words | X and Y plotted on the Raygor readability graph. | [72] |

| Simple Measure of Gobbledygook (SMOG) | # words three or more syllables (nwsy>=3), # of sentences (nst) | N/A | [73] |

*The Lexile scale is not included in this table as it outputs a non-grade level value that can then be converted to a reading grade level.

Health literacy plays a crucial role in patient health, with poor literacy directly affecting health outcomes [16,17]. While readability is an important component of health literacy and a proxy for an OPEM's understandability (albeit a surface-level one) [18], it is only a piece of the puzzle – as defined by the U.S. government in its Healthy People 2030 initiative, health literacy should “emphasize people's ability to use health information rather than just understand it” (italics added) [19]. Additional metrics of OPEMs, such as actionability, suitability, and quality, heavily influence the usability of health information, and thus should be evaluated alongside readability.

We aimed: 1) To measure average readability scores and characterize the reporting methodologies of English language breast cancer OPEM readability studies in the literature and 2) To determine what OPEM metrics associated with health literacy are reported alongside readability and how frequently such metrics are measured.

2. Materials and Methods

Institutional review board approval was not required for this study, as no human subjects are included. The systematic review was pre-registered on PROSPERO (CRD42022336461).

2.1. Study search and selection

This review adhered to the 2020 PRISMA statement [20]. Electronic searches for published literature were conducted by a medical librarian (XX) using Ovid MEDLINE (1946 to present), Embase.com (1947 to present), Web of Science (1900 to present), Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) via Ovid (1991 to present) and ClinicalTrials.gov (1999 to present) in June 2022.

The search strategy incorporated controlled vocabulary and free-text synonyms for the concepts of breasts, online patient education and readability. The full database search strategies are documented in Supplemental Table 1. All identified studies were combined and de-duplicated in a single reference manager (EndNote 20, Clarivate, Philadelphia, PA, USA). The citations were then uploaded into Covidence systematic review software (Veritas Health Innovation, Melbourne, Australia). Titles and abstracts were then independently screened for relevance by authors XX and XX, with any conflicts resolved by consensus vote.

2.2. Study eligibility, data extraction, and limitations

All articles conducting a readability analysis of English language online patient education materials related to breast cancer underwent full-text review. Included studies were published after 2010 and reported numerical readability scores using at least one readability index. Readability indices were any formula using plain text input to output a numerical score corresponding to a reading difficulty level or reading grade level (e.g. Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level, Simple Measure of Gobbledygook, Flesch Reading Ease, etc.). Offline materials, materials not directly related to breast cancer, materials primarily of a non-text medium (e.g. video-based content), and abstracts or posters were excluded. Studies reporting readability of non-English language OPEMs were excluded, as readability scores calculated using non-English readability indices cannot be directly compared to those from English language indices.

Relevant data from the included studies was extracted by one author, and the accuracy of extracted data was independently confirmed by a second. Study characteristics, including date of data collection, OPEM category (e.g. academic medical center, non-profit organization, government agency, etc.), and number of OPEMs were extracted. Reported readability scores and readability indices used were also recorded. Finally, reporting of other health literacy metrics, including usability, actionability, quality, use of figures, suitability, cultural sensitivity, complexity, and accessibility, were extracted.

2.3. Readability indices and scores

Extracted readability scores were largely reported as reading grade levels, corresponding to the number of years of education needed to easily read a piece of text. Readability scores are calculated using readability indices or formulas (Table 1). While most formulas directly output a reading grade level, others, such as the Flesch Reading Ease Scale and the Lexile scale, output a value that can be converted to a grade level using a conversion table. Each readability formula uses a unique set of variables to calculate readability; these include, but are not limited to, the number of characters, number of words, number of sentences, and number of multi-syllabic words in a sample of text. Additionally, some formulas require the sample text to be a certain length (100 or 150 words), whereas others do not have such a requirement.

2.4. Non-readability metrics

Extracted non-readability metrics of health literacy included understandability, actionability, quality, cultural sensitivity, suitability, complexity, and use of figures. Non-readability metrics used OPEM characteristics other than syntax and word complexity to output an assessment value, often with a validated assessment tool such as the Patient Education Materials Assessment Tool (PEMAT) and the Cultural Sensitivity Assessment Tool (CSAT), as in the case of understandability and cultural sensitivity respectively [18,21].

Whereas readability relies solely on objective variables to output a readability score, tools such as the PEMAT require the user to subjectively determine whether or not the material “uses common, everyday language” or “presents information in a logical sequence.” Non-readability metrics also assessed non-text components of OPEMs; for instance, the Suitability Assessment of Materials (SAM) tool rates OPEMs in a variety of text and non-text areas, including content, literacy demand, graphics, layout and type, learning stimulation and motivation, and cultural appropriateness [22].

2.5. Statistical analysis

Grade-level readability was quantified as mean and 95% confidence interval using generalized linear mixed modeling with Gauss-Hermite quadrature approximation and empirical sandwich estimation, where observations were nested by study and weighted by study sample size, when applicable, assuming a normal distribution. This was done for the following reason: there are multiple metrics, and each metric is an algorithm with a set of assumptions as to how grade-level readability should be quantified. Although each algorithm attempts to quantify grade-level readability, there is no way of determining which metric is better than another metric. Therefore, a point estimate of grade-level readability using several metrics is likely a closer estimate to the true grade-level readability than a single metric [23]. While readability studies may still have risk of bias, this risk is low and typically takes the form of selection bias (i.e., which OPEMs are included for analysis by a readability study). As this bias would not have adversely affected the comparability of our results, a risk of bias assessment was not conducted. All modeling was accomplished using the GLIMMIX procedure with SAS Software 9.4 (SAS Inc, Cary, NC).

3. Results

3.1. Search results

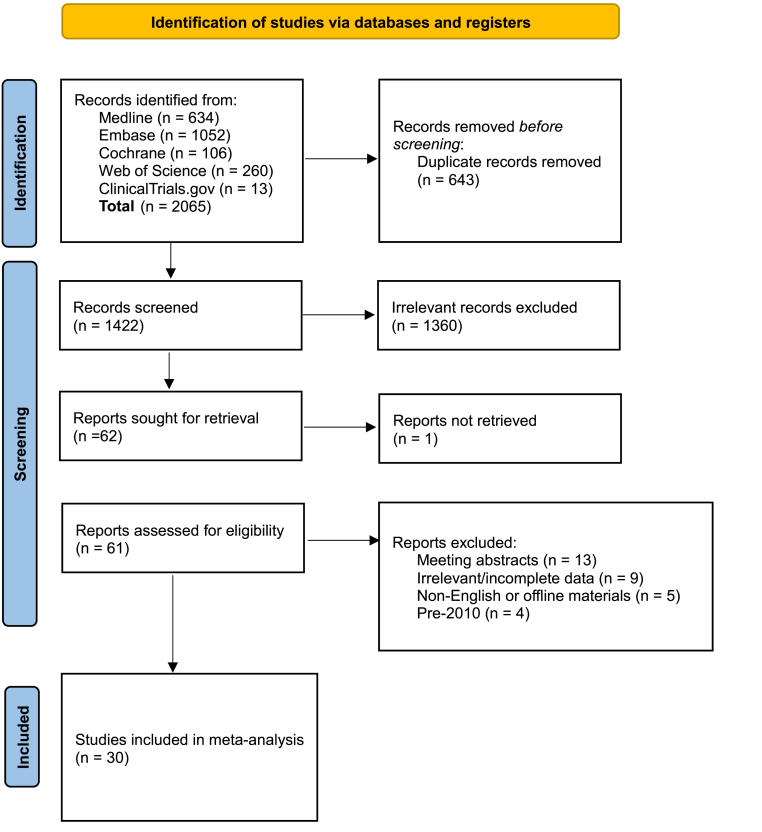

Of the 62 full-text articles assessed for eligibility, 32 were excluded (Fig. 1). Thirteen studies were abstracts or posters, seven were not readability studies or contained no useable readability data, four were published prior to 2010, three analyzed offline patient education materials, two were not relevant to breast cancer, two analyzed non-English language materials, and one did not have a retrievable full-text article. The remaining 30 studies underwent meta-analysis (Table 2) [[3], [4], [5], [6], [7],[9], [10], [11],14,15,[24], [25], [26], [27], [28], [29], [30], [31], [32], [33], [34], [35], [36], [37], [38], [39], [40], [41], [42], [43]].

Fig. 1.

Study flow diagram.

Table 2.

Summary of readability of included meta-analysis studies.

| No. | Study | Year | OPEM Topic | # of OPEMs | Readability Index |

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FKGL | SMOG | GF | CLI | ARI | FORCAST | Fry | NFC | Raygor | Dale-Chall | Linsear Write | Lexile | Average | |||||

| 1 | AlKhalili et al. | 2015 | Mammography | 42 | 10.7 | 13.3 | 14.3 | 12.8 | |||||||||

| 2 | Arif et al. | 2018 | BC treatment options | 188 | 8.5 | 7.0 | 7.8 | ||||||||||

| 3 | Basch et al. | 2019 | BC | 100 | 9.8 | 11.8 | 11.4 | 11.1 | 11.0 | ||||||||

| 4 | Cheah et al. | 2020 | BIA-ALCL | 15 | 12.9 | 12.2 | 15.0 | 12.5 | 12.9 | 13.1 | |||||||

| 5 | Chen et al. | 2020 | Autologous breast reconstruction | 10 | 12.4 | 12.4 | |||||||||||

| Implant breast reconstruction | 10 | 12.1 | 12.1 | ||||||||||||||

| 6 | Choudhery et al. | 2020 | Mammography | 1451 | 11.5 | 10.9 | 14.1 | 14.1 | 12.7 | ||||||||

| 7 | Cortez et al. | 2015 | BC risk calculator | 42 | 12.1 | 12.1 | |||||||||||

| 8 | Del Valle et al. | 2021 | Preventive mastectomy | 10 | 14.69 | 14.7 | |||||||||||

| 9 | Fan et al. | 2020 | Breast free flap | 12 | 10.1 | 9.3 | 12.5 | 9.5 | 10.1 | 10.2 | 6.3 | 9.7 | 11.8 | 9.25 | 9.9 | ||

| 10 | Hoppe et al. | 2010 | BC prevention (NCI) | 1 | 10.52 | 12.37 | 11.5 | ||||||||||

| 11 | Kim et al. | 2019 | BC/carcinoma | 106 | 11.9 | 13.7 | 13.9 | 11.4 | 13.2 | 10.3 | 13.6 | 12.6 | |||||

| 12 | Kressin et al. | 2016 | Dense breast notifications | 19 | 10.6 | 8.4 | 9.5 | ||||||||||

| 13 | Kulkarni et al. | 2018 | Chemical or physical BC agent | 235 | 10.9 | 10.9 | |||||||||||

| 14 | Lamb et al. | 2022 | BC risk factors | 162 | Used to determine average | 12.1 | |||||||||||

| 15 | Li et al. | 2021 | BC | 100 | 10.6 | 10.0 | 10.3 | ||||||||||

| 16 | Lynch et al. | 2017 | Breast reconstruction post mastectomy | 71 | 8.6 | 8.6 | |||||||||||

| 17 | Miles et al. (1) | 2019 | 11 breast lesions (e.g. IDC) | 9 | Used to determine average | 11.7 | |||||||||||

| 18 | Miles et al. (2) | 2020 | Breast density | 41 | Used to determine average | 11.1 | |||||||||||

| 19 | Miles et al. (3) | 2021 | BIA-ALCL | 24 | Used to determine average | 12.4 | |||||||||||

| 20 | Parr et al. | 2018 | Breast screening with implants | 15 | 9.0 | 9.0 | |||||||||||

| 21 | Powell et al. | 2021 | Breast reconstruction (academic) | 97 | 13.0 | 13.6 | 13.4 | 13.4 | |||||||||

| Breast reconstruction (non-academic) | 14 | 11.8 | 10.9 | 11.9 | 11.6 | ||||||||||||

| 22 | Rosenberg et al. | 2016 | NCIDCC websites (summarize topic) | 58 | 11.7 | 13.5 | 12.8 | 12.8 | 11.5 | 14.2 | 9.2 | 14.1 | 12.5 | ||||

| 23 | Sadigh et al. | 2016 | Mammography | 1524 | 10.6 | 10.4 | 13.3 | 13.6 | 10.4 | 11.7 | |||||||

| 24 | Saraiya et al. | 2019 | Breast density | 34 | 9.9 | 12.8 | 13.4 | 11.4 | 10.7 | 11.7 | |||||||

| 25 | Seth et al. | 2016 | Lymphedema | 12 | 12.3 | 14.1 | 13.8 | 12.9 | 11.3 | 13.0 | 10.4 | 13 | 12.2 | 12.6 | |||

| 26 | Tran et al. (1) | 2017 | Lymphedema | 10 | 14.0 | 14.0 | |||||||||||

| 27 | Tran et al. (2) | 2017 | Mastectomy, lumpectomy | 20 | 14.6 | 14.6 | |||||||||||

| 28 | Vargas et al. (1) | 2014 | BC surgery | 10 | 12.3 | 14.3 | 14.4 | 12.6 | 11.2 | 14.0 | 11.0 | 14.0 | 12.4 | 12.9 | |||

| 29 | Vargas et al. (2) | 2015 | Breast reconstruction | 10 | 13.4 | 13.4 | |||||||||||

| 30 | Vargas et al. (3) | 2014 | Breast reconstruction | 10 | 10.9 | 13.0 | 12.7 | 11.8 | 10.7 | 12.0 | 9.7 | 12.0 | 10.6 | 11.5 | |||

| Study | Year | # of OPEMs | FKGL | SMOG | GF | CLI | ARI | FORCAST | Fry | NFC | Raygor | Dale-Chall | Linsear Write | Lexile | Average | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Meta-analysis | 2010–2021 | 4462 | 11.0 | 12.2 | 13.0 | 14.5 | 11.4 | 10.7 | 12.6 | 9.4 | 11.8 | 10.8 | 13.0 | 10.4 | 11.8 |

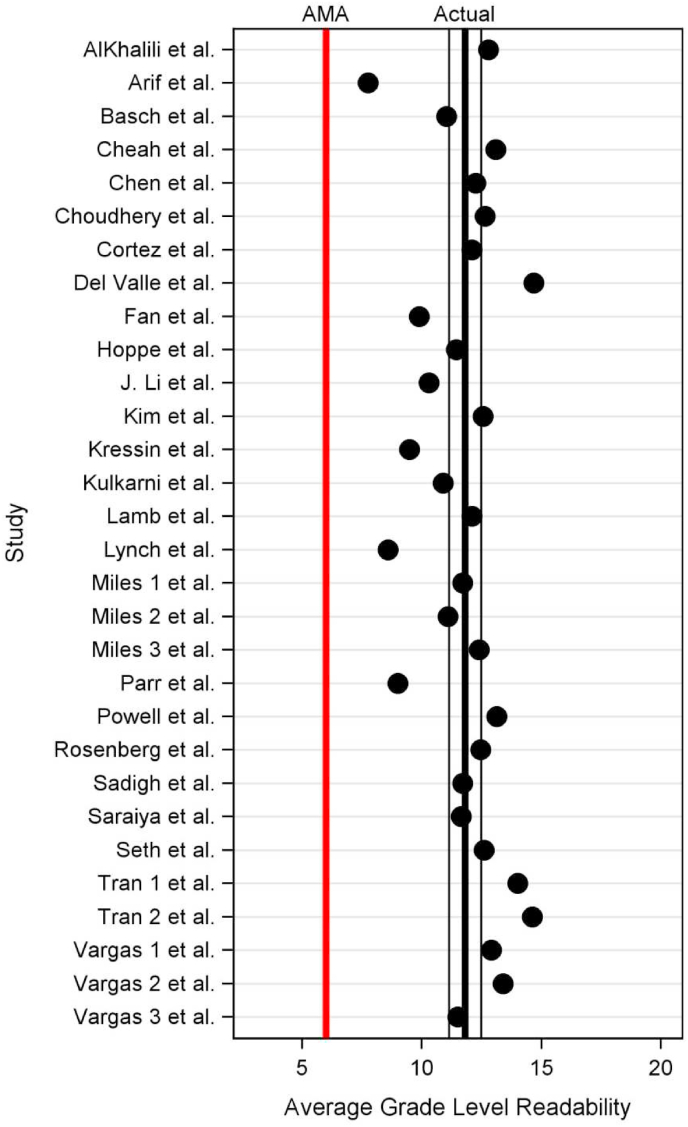

3.2. Meta-analysis

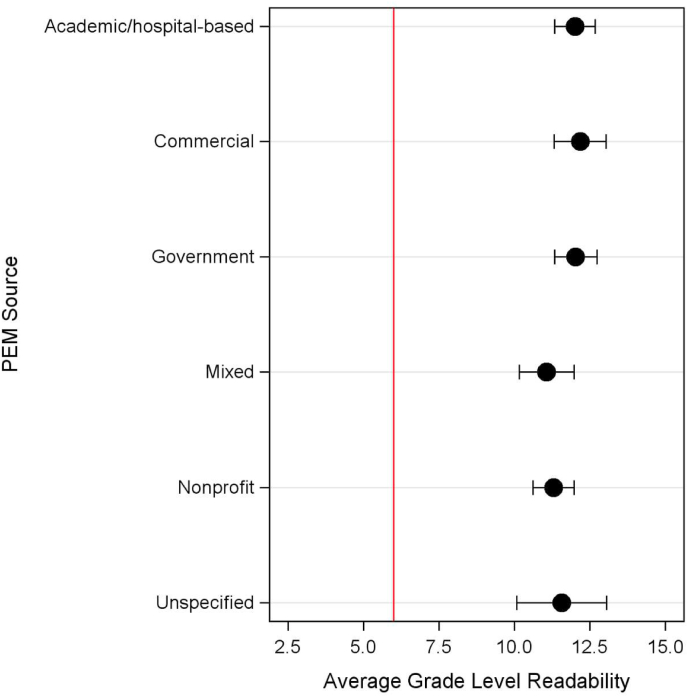

Overall, average readability across all included studies was 11.81 (95% CI [11.14, 12.49], Fig. 2). There was a significant difference (p < 0.001) between average readability scores by OPEM categories (Fig. 3): OPEMs from commercial organizations had the highest average readability (12.2 [11.3, 13.0]), followed by government organizations (12.0, [11.3, 12.7]), academic/hospital-based institutions (12.0, [11.3, 12.7]), unspecified sources (11.6, [10.1, 13.1]), non-profit organizations (11.3, [10.6, 12.0]), and finally mixed categories (11.07 [10.2, 12.0]).

Fig. 2.

Average grade level readability by study with 95% CI vs. AMA's recommended 6th grade reading level.

Fig. 3.

Average grade level readability by OPEM category vs. AMA's recommended 6th grade reading level.

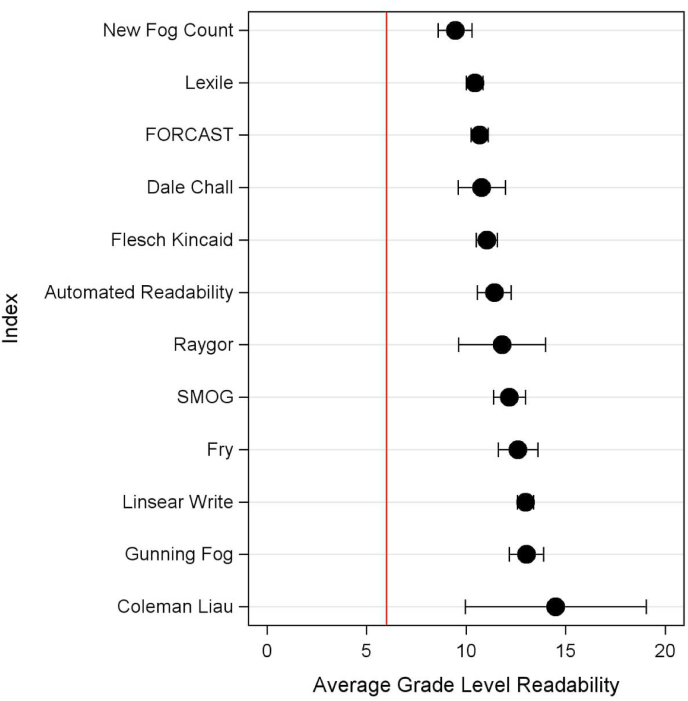

Variability existed between readability indices (Fig. 4), with New Fog, Lexile, and FORCAST having the lowest average scores (9.4 [8.6, 10.3], 10.4 [10.0, 10.7], and 10.7 [10.2, 11.1], respectively). Only 57% of studies (17/30) calculated average readability with more than two indices. Forty percent (12/30) of studies measured readability with the Flesch Reading Ease Score (FRES) in addition to using other grade level-based indices. The average FRES of these studies was 46.9 [45.2, 48.6], approximately corresponding to a college reading level and suggesting difficult to read content [44].

Fig. 4.

Average grade level readability by readability index vs. AMA's recommended 6th grade reading level.

Sixty percent (18/30) of studies assessed other OPEM metrics associated with health literacy, in addition to readability (Table 3): 10% (3/30) evaluated use of figures, 10% (3/30) evaluated suitability, 10% (3/30) evaluated cultural sensitivity, 10% (3/30) evaluated complexity, 13% (4/30) evaluated understandability, 17% (5/30) evaluated actionability, and 20% (6/30) evaluated OPEM quality, either qualitatively (e.g. HON-code) or quantitatively (e.g., JAMA benchmark, DISCERN score, Michigan score, etc.).

Table 3.

Summary of non-readability OPEM metrics of included meta-analysis studies.

| No. | Study | Year | Any Non-Readability Metrics Assessed? |

Did the study assess … |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Understandability | Actionability | Quality | Cultural Sensitivity | Suitability | Complexity | Use of Figures | ||||

| 1 | AlKhalili et al. | 2015 | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| 2 | Arif et al. | 2018 | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| 3 | Basch et al. | 2019 | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| 4 | Cheah et al. | 2020 | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| 5 | Chen et al. | 2020 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | No |

| 6 | Choudhery et al. | 2020 | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| 7 | Cortez et al. | 2015 | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| 8 | Del Valle et al. | 2021 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | No |

| 9 | Fan et al. | 2020 | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| 10 | Hoppe et al. | 2010 | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| 11 | Kim et al. | 2019 | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| 12 | Kressin et al. | 2016 | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No |

| 13 | Kulkarni et al. | 2018 | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | No | No | No |

| 14 | Lamb et al. | 2022 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No |

| 15 | Li et al. | 2021 | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | Yes |

| 16 | Lynch et al. | 2017 | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| 17 | Miles et al. (1) | 2019 | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | Yes |

| 18 | Miles et al. (2) | 2020 | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| 19 | Miles et al. (3) | 2021 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No |

| 20 | Parr et al. | 2018 | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| 21 | Powell et al. | 2021 | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| 22 | Rosenberg et al. | 2016 | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| 23 | Sadigh et al. | 2016 | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| 24 | Saraiya et al. | 2019 | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | Yes |

| 25 | Seth et al. | 2016 | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| 26 | Tran et al. (1) | 2017 | Yes | No | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | No |

| 27 | Tran et al. (2) | 2017 | Yes | No | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | No |

| 28 | Vargas et al. (1) | 2014 | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| 29 | Vargas et al. (2) | 2015 | Yes | No | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | No |

| 30 | Vargas et al. (3) | 2014 | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Study | Year | Non-Readability Metrics (% studies) | Understandability | Actionability | Quality | Cultural Sensitivity | Suitability | Complexity | Use of Figures | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Meta-analysis | 2010–2021 | 60% (18/30) | 13.3% | 16.7% | 20% | 10% | 10% | 10% | 10% |

Studies assessing understandability and actionability did so via the Patient Education Materials Assessment Tool (PEMAT), with average scores of 62.8 [60.5, 65.2] and 32.2 [25.7, 38.6], respectively. Studies assessing cultural sensitivity did so via the Cultural Sensitivity Assessment Tool (CSAT), with an average score of 3.5 [2.4, 4.5], suggesting culturally sensitive materials (CSAT >2.5). Studies assessing visual complexity of OPEMs did so via the PMOSE/IKIRSCH formula, with an average score of 6.3 [5.6, 7.0], corresponding with low complexity and an appropriateness for those with a range of schooling between 8th grade and a high school degree. Studies assessing suitability did so via the Suitability Assessment of Materials (SAM) scale, with an average score of 43.1 [38.3, 47.8], suggesting material of adequate suitability. While three studies evaluated use of figures, only two reported this metric as a percentage of OPEMs that include figures (55.6% and 50%). Finally, of the six studies that evaluated quality of OPEMs, five examined HON-code certification and five examined a quantitative quality assessment (JAMA, DISCERN, Michigan, or Abbott scores). Only one of the six studies reported quality findings with more than two scores.

4. Discussion

In this systematic review and meta-analysis on breast cancer readability scores and other health literacy metrics, 30 published studies since 2010, encompassing a total of 4462 OPEMs, were identified for inclusion. Average readability of included studies was nearly twice the recommended AMA 6th grade reading level, with no individual study at or below the recommended level. Of the included studies, only 57% (17/30) calculated average readability with more than two readability indices, and only 60% (18/30) assessed other OPEM metrics related to health literacy, in addition to readability.

While reading grade levels are high across the included breast cancer OPEMs, our sub-group analysis suggested readability is significantly different depending on the OPEM category. Commercial, government, and academic institutions were among the categories with highest reading grade levels (at 12.2, 12.0, and 12.0 respectively), while non-profit organizations were among the lowest at 11.3. Per a 2003 study, the most trusted sources of online health information, other than the personal doctor, are medical universities and the federal government [45]; notably, academic institutions and government organizations are OPEM sources identified in the present study as having materials with the highest readability scores, corresponding to difficult to read material. While the 0.7–0.9 difference between non-profit OPEMs and the other OPEM categories is statistically significant, there is no evidence in the literature to suggest the difference is meaningful from a reading comprehension standpoint.

Readability scores differ by readability index, in addition to by OPEM source, with New Fog, Lexile, and FORCAST having the lowest average reading grade levels; this could be due to the formulas themselves, which studies these indices were applied to, or both. Specifically, each index calculates its grade level readability score with a different formula (see Table 1). This difference in readability index methodology can lead to the calculation of varying reading grade levels for the same set of OPEMs; AlKhalili et al.’s study on OPEMs related to mammography reported reading grade levels ranging from 10.7 (Flesch Kincaid) to 14.3 (Gunning Fog) [3]. Flesch Kincaid counts the number of syllables, words, and sentences, whereas Gunning Fog differentiates between number of total words, complex words (three or more syllables), and sentences (Table 1). Additionally, variability in calculated reading grade level can arise from whether calculations are made with readability software (e.g. https://readable.com, Sussex, England) or done so manually, largely due to differences in sample text preparation [46].

In addition to readability, other important metrics such as quality, understandability, and actionability are necessary to holistically evaluate OPEMs. Notably, these other metrics look beyond purely syntactical elements, instead assessing a variety of OPEM features, ranging from non-text components (e.g. graphics and videos) to more subjective aspects, such as whether or not material is directed for the intended audience or information is logically presented. For instance, quality of OPEMs is measured with a variety of tools – the JAMA benchmarks assess quality by looking at authorship, attribution, disclosure, and currency of materials, whereas the DISCERN instrument consists of 15 questions assessing content accuracy and informativeness [47,48]. Understandability and actionability are most often measured with the PEMAT, a questionnaire with a total of 26 items that outputs two scores, one for a material's understandability and another for actionability [18]. Of the non-readability OPEM metrics assessed by the included meta-analysis studies, quality, understandability, and actionability were reported at the highest frequencies, at 20%, 13.3%, and 16.7% respectively. While other metrics, such as cultural sensitivity, suitability, complexity, and use of figures, were reported less frequently (all at 10%), these metrics may still be important to report depending on the specific health subject matter. For instance, the Cultural Sensitivity Assessment Tool (CSAT) was originally developed to assess cancer materials' appropriateness for the African American population [21]. As disparities in breast cancer care continue to exist today across various ethnic and cultural groups [[49], [50], [51]], assessment of breast cancer-related OPEMs should include appropriateness evaluation using validated tools such as CSAT whenever possible. Once OPEM readability has been established, additional metrics of health literacy, including but not limited to quality, understanding, actionability, and cultural sensitivity, should also be assessed to provide a multi-dimensional evaluation of a material's overall usability.

A secondary objective of the present study was to inform future assessment of OPEMs so that ultimately patients can access readable, useable, and high-quality health materials. The results suggest that reporting of both readability and other health literacy-related metrics vary tremendously across the literature. Additionally, on literature review, we found no published guidelines on the reporting of OPEM readability. To ensure greater patient and provider trust in and usability of OPEMs, we propose a checklist of reporting criteria for future studies evaluating OPEMs (Table 4). Some readability indices have been shown to correlate poorly between each other and produce grading inconsistencies, suggesting that a single index may produce a misleading characterization of a text's readability [[52], [53], [54]]. When various readability formulas were applied to the Blog Authorship Corpus (a corpus of text containing 140 million words), correlation among indices was weak – for instance, CLI had a correlation of only 0.13, 0.11, and 0.09 with Dale-Chall, ARI, and Linsear Write, respectively. Conversely, other indices have been shown to correlate well with one another, such as ARI, New Fog, and FKGL [55]. At a minimum, future studies should report OPEM readability with multiple indices and examine one or more non-readability metrics related to health literacy (such as quality, understandability, actionability, or cultural appropriateness), with validated tools when possible. When selecting readability indices, authors should consider both the syntactic elements measured and whether or not an index is suitable for OPEMs specifically, as several indices were developed and validated using non-narrative text, such as technical military manuals (Table 1) [[55], [56], [57]].

Table 4.

Proposed checklist for reporting OPEM readability.

| Reporting Variables | No | Recommendation |

| Study Characteristics | 1 | State the date (month and year) of the online search and the country it was performed |

| 2 | State the search engine(s) used (e.g., Google, Yahoo, Bing, etc.) | |

| 3 | State all search terms used, including both abbreviations and spelled-out terms (i.e., “DCIS” and “ductal carcinoma in situ”) | |

| OPEM Characteristics | 4 | State the number of unique OPEMs identified and how this was defined (i.e., each unique URL vs. all pages from one site as one OPEM) |

| Readability and Additional Health Literacy OPEM Metrics | 5 | Use validated scales to report data for both readability and non-readability OPEM metrics |

| 6 | Report quality (i.e., reliability and/or accuracy of OPEMs as a source of patient decision-making information) with a minimum of one quantitative quality assessment tool (e.g., JAMA, DISCERN, etc.) | |

| 7 | Report understandability and/or actionability with a validated tool (e.g., PEMAT) | |

| 8 | Consider inclusion of additional non-readability metrics, such as cultural sensitivity, use of figures, suitability, accessibility, etc. |

Recent advances in the field, especially using natural language processing (NLP) and machine learning techniques, have demonstrated more accurate prediction of human judgments of text readability, when compared to the traditional formulas [58,59]. NLP and machine learning techniques are able to elucidate deeper text features (e.g., conceptual density, text sequence probability, etc.) in order to model fundamental aspects of language (e.g., morphology, semantics, pragmatics, etc.); however, further testing in a variety of text domains and reader populations is needed to support the adoption and efficacy of these techniques over traditional readability formulas.

The present study has several limitations. First, to ensure maximum inter-study comparability, only papers assessing English-language readability were eligible for inclusion, so results may not be generalizable to OPEMs written in non-English languages. U.S. Census Bureau data from 2018 indicates that 21.7% of people in the United States speak a language other than English at home and 13.3% of the population speak Spanish at home – these numbers are only rising [60,61]. One recent study comparing Spanish-language OPEMs on breast cancer with corresponding English OPEMs found Spanish-language materials to be more likely to meet AMA reading level recommendations [62]; however, the value of direct comparisons between grade level readability calculated from English and Spanish texts is unclear, due to inherent lingual and cultural differences (syntax, number of syllables, vocabulary, etc.) and scarcity of indices that output comparable grade level readability for both languages - only Fry has been validated to do so and only at the primary school level [63]. Despite these challenges, further examination of non-English OPEMs remains important, as non-English speaking patients have been found to be less likely to engage in breast cancer screening [64,65].

Second, limitations inherent to readability studies also apply here. For instance, readability of OPEMs may be artificially inflated due to the necessary inclusion of complex medical terminology (e.g., mammography, invasive ductal carcinoma) [66]. Readability formulas cannot evaluate graphs, videos, or other visual aids, which are all widely implemented on patient-facing websites. Third, articles needed to conduct a readability analysis to be eligible for inclusion in the present study. As a result, studies that examined other health literacy-related metrics (quality, actionability, cultural appropriateness, etc.) but did not examine readability were not included in the meta-analysis. Finally, the present study was limited in scope to breast cancer-related topics; however, we believe our findings, including the overall high reading grade level, limited use of multiple readability indices, and lack of reporting of non-readability health literacy-related OPEM metrics, are generalizable to other health topics as well.

5. Conclusion

Average readability of breast cancer OPEMs is inconsistently reported in the literature and nearly double the AMA's recommended 6th grade reading level. Reading grade level alone fails to assess many other aspects of OPEMs that also heavily contribute to a patient's ability to understand and use the presented health information. Readability should be assessed in a standardized manner and in conjunction with other health literacy metrics so that OPEMs can be thoroughly and holistically characterized, to the benefit of patients and providers alike. Additionally, readability studies examining non-English language OPEMs are few – further investigation is needed to better address the unique health literacy needs of this patient population.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Joey Z. Gu: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Validation, Project administration, Methodology, Investigation, Data curation, Conceptualization. Grayson L. Baird: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Supervision, Software, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Antonio Escamilla Guevara: Project administration, Methodology, Investigation, Data curation, Conceptualization. Melis Lydston: Project administration, Methodology, Investigation, Data curation, Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Resources, Methodology, Investigation, Data curation, Conceptualization. Christopher Doyle: Writing – original draft, Supervision, Investigation, Conceptualization. Sarah E.A. Tevis: Writing – original draft, Supervision, Investigation, Conceptualization. Randy C. Miles: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Supervision, Project administration, Methodology, Investigation, Conceptualization.

Declaration of competing interest

No funding was received for this work. The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.breast.2024.103722.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article.

References

- 1.Center P.R. Pew Research Center; Washington, D.C: 2013. Health online 2013.https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/wp-content/uploads/sites/9/media/Files/Reports/PIP_HealthOnline.pdf [updated Jan 15, 2013. Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weiss B.D. second ed. American Medical Assocation Foundation; Chicago, IL: 2007. Health literacy and patient safety: help patients understand. [Google Scholar]

- 3.AlKhalili R., Shukla P.A., Patel R.H., Sanghvi S., Hubbi B. Readability assessment of internet-based patient education materials related to mammography for breast cancer screening. Acad Radiol. 2015;22(3):290–295. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2014.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cortez S., Milbrandt M., Kaphingst K., James A., Colditz G. The readability of online breast cancer risk assessment tools. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2015;154(1):191–199. doi: 10.1007/s10549-015-3601-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Miles R.C., Baird G.L., Choi P., Falomo E., Dibble E.H., Garg M. Readability of online patient educational materials related to breast Lesions requiring Surgery. Radiology. 2019;291(1):112–118. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2019182082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Seth A.K., Vargas C.R., Chuang D.J., Lee B.T. Readability assessment of patient information about lymphedema and its treatment. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2016;137(2) doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000475747.95096.ab. 287e-95e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vargas C.R., Chuang D.J., Ganor O., Lee B.T. Readability of online patient resources for the operative treatment of breast cancer. Surgery. 2014;156(2):311–318. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2014.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Keating N.L., Pace L.E. New federal requirements to inform patients about breast density: will they help patients? JAMA. 2019;321(23):2275–2276. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.5919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kressin N.R., Gunn C.M., Battaglia T.A. Dense breast notifications: varying content, readability, and understandability by state. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31(2):S175–S176. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.1712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Miles R.C., Choi P., Baird G.L., Dibble E.H., Lamb L., Garg M., et al. Will the effect of new federal breast density legislation Be diminished by currently available online patient educational materials? Acad Radiol. 2020;27(10):1400–1405. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2019.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Saraiya A., Baird G.L., Lourenco A.P. Breast density notification letters and websites: are they too "dense". J Am Coll Radiol. 2019;16(5):717–723. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2018.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stelzer J.W., Wellington I.J., Trudeau M.T., Mancini M.R., LeVasseur M.R., Messina J.C., et al. Readability assessment of patient educational materials for shoulder arthroplasty from top academic orthopedic institutions. JSES Int. 2022;6(1):44–48. doi: 10.1016/j.jseint.2021.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tulbert B.H., Snyder C.W., Brodell R.T. Readability of patient-oriented online dermatology resources. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2011;4(3):27–33. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen D.H., Johnson A.R., Ayyala H., Lee E.S., Lee B.T., Tran B.N.N. A multimetric health literacy analysis of autologous versus implant-based breast reconstruction. Ann Plast Surg. 2020;85(S1 Suppl 1):S102–S108. doi: 10.1097/SAP.0000000000002348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fan K.L., Black C.K., DeFazio M.V., Luvisa K., Camden R., Song D.H. Bridging the knowledge gap: an examination of the ideal postoperative autologous breast reconstruction educational material with A/B testing. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2020;145(1):258–266. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000006373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cho Y.I., Lee S.Y., Arozullah A.M., Crittenden K.S. Effects of health literacy on health status and health service utilization amongst the elderly. Soc Sci Med. 2008;66(8):1809–1816. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Williams M.V., Davis T., Parker R.M., Weiss B.D. The role of health literacy in patient-physician communication. Fam Med. 2002;34(5):383–389. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shoemaker S.J., Wolf M.S., Brach C. Development of the Patient Education Materials Assessment Tool (PEMAT): a new measure of understandability and actionability for print and audiovisual patient information. Patient Educ Couns. 2014;96(3):395–403. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2014.05.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Promotion OoDPaH . U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2020. Health literacy in Healthy people 2030. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Page M.J., McKenzie J.E., Bossuyt P.M., Boutron I., Hoffmann T.C., Mulrow C.D., et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372 doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guidry J.J., Walker V.D. Assessing cultural sensitivity in printed cancer materials. Cancer Pract. 1999;7(6):291–296. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-5394.1999.76005.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Doak Ccd L.G., Root J.H. second ed. Lippincott; Philadelphia, PA: 1996. Teaching patients with low literacy skills. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Galton F. Vox populi. Nature. 1907;75:450–451. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Arif N., Ghezzi P. Quality of online information on breast cancer treatment options. Breast. 2018;37:6–12. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2017.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Basch C.H., MacLean S.A., Garcia P., Basch C.E. Readability of online breast cancer information. Breast J. 2019;25(3):562–563. doi: 10.1111/tbj.13276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cheah M.A., Sarmiento S., Bernatowicz E., Rosson G.D., Cooney C.M. Online patient resources for breast implant-associated anaplastic large cell lymphoma: a readability analysis. Ann Plast Surg. 2020;84(4):346–350. doi: 10.1097/SAP.0000000000002218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Choudhery S., Xi Y., Chen H., Aboul-Fettouh N., Goldenmerry Y., Ho C., et al. Readability and quality of online patient education material on websites of breast imaging centers. J Am Coll Radiol. 2020;17(10):1245–1251. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2020.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Del Valle D.D., Pardo J.A., Maselli A.M., Valero M.G., Fan B., Seyidova N., et al. Evaluation of online Spanish and English health materials for preventive mastectomy. are we providing adequate information? Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2021;187(1):1–9. doi: 10.1007/s10549-021-06171-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hoppe I.C. Readability of patient information regarding breast cancer prevention from the Web site of the National Cancer Institute. J Cancer Educ. 2010;25(4):490–492. doi: 10.1007/s13187-010-0101-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kim C., Prabhu A.V., Hansberry D.R., Agarwal N., Heron D.E., Beriwal S. Digital Era of mobile communications and smartphones: a novel analysis of patient comprehension of cancer-related information available through mobile applications. Cancer Invest. 2019;37(3):127–133. doi: 10.1080/07357907.2019.1572760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kulkarni S., Lewis K., Adams S.A., Brandt H.M., Lead J.R., Ureda J.R., et al. A comprehensive analysis of how environmental risks of breast cancer are portrayed on the internet. Am J Health Educ. 2018;49(4):222–233. doi: 10.1080/19325037.2018.1473182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lamb L.R., Baird G.L., Roy I.T., Choi P.H.S., Lehman C.D., Miles R.C. Are English-language online patient education materials related to breast cancer risk assessment understandable, readable, and actionable? Breast. 2022;61:29–34. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2021.11.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li J.Z.H., Kong T., Killow V., Wang L., Kobes K., Tekian A., et al. Quality assessment of online resources for the most common cancers. J Cancer Educ. 2021;38(1):34–41. doi: 10.1007/s13187-021-02075-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lynch N.P., Lang B., Angelov S., McGarrigle S.A., Boyle T.J., Al-Azawi D., et al. Breast reconstruction post mastectomy- Let's Google it. Accessibility, readability and quality of online information. Breast. 2017;32:126–129. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2017.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Miles R.C., Lourenco A.P., Baird G.L., Roy I.T., Choi P.H.S., Lehman C., et al. A multimetric evaluation of online patient educational materials for breast implant–associated anaplastic large cell lymphoma. Journal of Breast Imaging. 2021;3(5):564–571. doi: 10.1093/jbi/wbab053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Parr O., Dunmall K. An evaluation of online information available for women with breast implants aged 47-73 who have been invited to attend the NHS Breast Screening Programme. Radiography. 2018;24(4):315–327. doi: 10.1016/j.radi.2018.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Powell L.E., Andersen E.S., Pozez A.L. Assessing readability of patient education materials on breast reconstruction by major US academic hospitals as compared with nonacademic sites. Ann Plast Surg. 2021;86(6):610–614. doi: 10.1097/SAP.0000000000002575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rosenberg S.A., Francis D., Hullett C.R., Morris Z.S., Fisher M.M., Brower J.V., et al. Readability of online patient educational resources found on NCI-designated cancer center web sites. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2016;14(6):735–740. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2016.0075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sadigh G., Singh K., Gilbert K., Khan R., Duszak A.M., Duszak R., Jr. Mammography patient information at hospital websites: most neither comprehensible nor guideline supported. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2016;207(5):947–951. doi: 10.2214/AJR.16.16436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tran B.N.N., Singh M., Lee B.T., Rudd R., Singhal D. Readability, complexity, and suitability analysis of online lymphedema resources. J Surg Res. 2017;213:251–260. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2017.02.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tran B.N.N., Singh M., Singhal D., Rudd R., Lee B.T. Readability, complexity, and suitability of online resources for mastectomy and lumpectomy. J Surg Res. 2017;212:214–221. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2017.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vargas C.R., Kantak N.A., Chuang D.J., Koolen P.G., Lee B.T. Assessment of online patient materials for breast reconstruction. J Surg Res. 2015;199(1):280–286. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2015.04.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vargas C.R., Koolen P.G.L., Chuang D.J., Ganor O., Lee B.T. Online patient resources for breast reconstruction: an analysis of readability. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2014;134(3):406–413. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000000472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Flesch R. Harper & Row; 1979. Let's start with the formula. How to write plain English. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dutta-Bergman M. Trusted online sources of health information: differences in demographics, health beliefs, and health-information orientation. J Med Internet Res. 2003;5(3) doi: 10.2196/jmir.5.3.e21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mac O., Ayre J., Bell K., McCaffery K., Muscat D.M. Comparison of readability scores for written health information across formulas using automated vs manual measures. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(12) doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.46051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Charnock D., Shepperd S., Needham G., Gann R. DISCERN: an instrument for judging the quality of written consumer health information on treatment choices. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1999;53(2):105–111. doi: 10.1136/jech.53.2.105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Silberg W.M., Lundberg G.D., Musacchio R.A. Assessing, controlling, and assuring the quality of medical information on the Internet: caveant lector et viewor--Let the reader and viewer beware. JAMA. 1997;277(15):1244–1245. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gerend M.A., Pai M. Social determinants of Black-White disparities in breast cancer mortality: a review. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2008;17(11):2913–2923. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-0633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gomez S.L., Quach T., Horn-Ross P.L., Pham J.T., Cockburn M., Chang E.T., et al. Hidden breast cancer disparities in Asian women: disaggregating incidence rates by ethnicity and migrant status. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(Suppl 1):S125–S131. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.163931. Suppl 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yedjou C.G., Sims J.N., Miele L., Noubissi F., Lowe L., Fonseca D.D., et al. Health and racial disparity in breast cancer. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2019;1152:31–49. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-20301-6_3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lines N.A. The past, problems, and potential of readability analysis. Chance. 2022;35(2):16–24. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhou S., Jeong H., Green P.A. How consistent are the best-known readability equations in estimating the readability of design standards? IEEE Transactions on Professional Communication. 2017;60(1):97–111. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wang L.W., Miller M.J., Schmitt M.R., Wen F.K. Assessing readability formula differences with written health information materials: application, results, and recommendations. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2013;9(5):503–516. doi: 10.1016/j.sapharm.2012.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kincaid J.P., Fishburne R.P.J., Rogers R.L., Chissom B.S. Research branch report 8-75, millington, TN: naval technical training, US naval air station, memphis. TN; 1975. Derivation of new readability formulas (automated readability index, Fog count and flesch reading Ease formula) for navy enlisted personnel. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Smith E.A., Kincaid J.P. Derivation and validation of the automated readability index for use with technical materials. Hum Factors. 1970;12(5) [Google Scholar]

- 57.Caylor J.S., Sticht T.G. American Educational Research Association; 1973. Development of a Simple readability index for job reading material. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Balyan R.M., K S, McNamara D.S. Applying natural language processing and hierarchical machine learning approaches to text difficulty classification. Int J Artif Intell Educ. 2020;30:338–370. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Crossley S.A., Skalicky S., Dascalu M., McNamara D.S., Kyle K. Predicting text comprehension, processing, and familiarity in adult readers: new approaches to readability formulas. Discourse Process. 2017;54(5–6):340–359. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bureau USC Language spoken at home. 2018. https://www.census.gov/acs/www/about/why-we-ask-each-question/language/ [Available from:

- 61.Bureau U.S.C. Top languages other than English spoken in 1980 and changes in relative rank. 1990-2010 2021. https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/sis/resources/visualizations/spoken-languages.html [Available from:

- 62.Villa Camacho J.C., Pena M.A., Flores E.J., Little B.P., Parikh Y., Narayan A.K., et al. Addressing linguistic barriers to care: evaluation of breast cancer online patient educational materials for Spanish-speaking patients. J Am Coll Radiol. 2021;18(7):919–926. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2021.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Gilliam B., Pe xf, a S.C., Mountain L. The Fry graph applied to Spanish readability. Read Teach. 1980;33(4):426–430. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hiatt R.A., Pasick R.J., Stewart S., Bloom J., Davis P., Gardiner P., et al. Community-based cancer screening for underserved women: design and baseline findings from the Breast and Cervical Cancer Intervention Study. Prev Med. 2001;33(3):190–203. doi: 10.1006/pmed.2001.0871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Jacobs E.A., Karavolos K., Rathouz P.J., Ferris T.G., Powell L.H. Limited English proficiency and breast and cervical cancer screening in a multiethnic population. Am J Public Health. 2005;95(8):1410–1416. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.041418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Meade C.D., Smith C.F. Readability formulas: cautions and criteria. Patient Educ Counsel. 1991;17:153–158. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Liau T.L., Bassin C.B., Martin C.J., Coleman E.B. Modification of the coleman readability formulas. J Read Behav. 1976;8(4):381–386. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Dale E., Chall J.S. A formula for predicting readability: instructions. Educ Res Bull. 1948;27(2):37–54. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Fry E. A readability formula that saves time. J Read. 1968;11(7):75–78. 513-6. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Gunning R. McGraw-Hill; 1952. The technique of clear writing; p. 289. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Klare G.R. Assessing readability. Read Res Q. 1974;10(1):74. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Raygor A.L. 26th yearbook of the national reading conference) 1977. The raygor readability estimate: a quick and easy way to determine difficulty. Reading: theory, research, and practice. [Google Scholar]

- 73.McLaughlin G.H. SMOG grading - a new readability formula. J Read. 1969;12(8):639–646. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.