Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Familial hypercholesterolemia is a treatable genetic condition but remains underdiagnosed. We reviewed the frequency of pathogenic or likely pathogenic (P/LP) variants in the LDLR gene in female individuals receiving reproductive carrier screening.

METHODS:

This retrospective observational study included samples from female patients (aged 18–55 years) receiving a 274-gene carrier screening panel from January 2020 to September 2022. LDLR exons and their 10 base pair flanking regions were sequenced. Carrier frequency for P/LP variants was calculated for the entire population and by race/ethnicity. The most common variants and their likely functional effects were evaluated.

RESULTS:

A total of 91 637 tests were performed on women with race/ethnicity reported as Asian (8.8%), Black (6.1%), Hispanic (8.5%), White (29.0%), multiple or other (15.0%), and missing (33.0%). Median age was 32.8 years with 83 728 (91%) <40 years. P/LP LDLR variants were identified in 283 samples (1 in 324). No patients were identified with >1 P/LP variant. LDLR carrier frequency was higher in Asian (1 in 191 [95% CI, 1 in 142–258]) compared with White (1 in 417 [95% CI, 1 in 326–533]; P<0.001) or Black groups (1 in 508 [95% CI, 1 in 284–910]; P=0.004). The most common variants differed between populations. Of all variants, at least 25.0% were predicted as null variants.

CONCLUSIONS:

P/LP variants in LDLR are common. Expanding the use of reproductive carrier screening to include genes associated with FH presents another opportunity to identify people predisposed to cardiovascular disease.

Keywords: cardiovascular diseases; cholesterol, LDL; hypercholesterolemia, familial; receptors, LDL

Familial hypercholesterolemia (FH) is a condition associated with early-onset atherosclerotic coronary artery disease, secondary to elevated LDL-C (low-density lipoprotein cholesterol). Individuals who are homozygous (or compound heterozygous [He], biallelic) for pathogenic variants in FH (HoFH) genes can display a severe phenotype in which hypercholesterolemia may be present from birth and coronary artery disease may develop by the teenage years.1–4 Death from coronary disease has been reported as early as 4 years of age5 and coronary artery bypass may be indicated by 10 years.4 Untreated, people with HoFH are not expected to survive past 30 years.6 People with a pathogenic FH gene variant in only 1 allele have HeFH and are also at risk for early onset atherosclerosis.1,6 Early treatment of HeFH reduces both premature cardiovascular disease and death.7–11 However, most people with FH are undiagnosed8 or only diagnosed later in life when atherosclerotic disease is already established.12

Four genes have been implicated in FH; LDLR, APOB, PCSK9, and LDLRAP1.1,13 Of these, pathogenic variants in LDLR are thought to be the most common.13 There is currently no genetic-based national screening program for FH gene variants and only limited sequencing data for unselected populations in the United States.14,15

Reproductive carrier screening is offered to individuals to assess their chances of having a child affected by a genetic condition.16,17 Gene variants in LDLR are included in some carrier screening panels because of the ability to assess risks for HoFH. Identification of heterozygous FH through reproductive carrier screening is currently viewed as an incidental finding, secondary to the main purpose of identifying couples at high risk for having a child with HoFH. To establish the chance of having a child with HoFH, the male partner also has to undergo carrier screening.

Our objective was to use data from reproductive carrier screening to evaluate the prevalence and type of pathogenic or likely pathogenic (P/LP) LDLR variants present in an unselected female population.

METHODS

This retrospective observational study used data from samples submitted to a commercial genetic testing company (January 2020 to September 2022) for a 274-gene reproductive carrier screening panel which includes the LDLR gene. Detailed methods are available in the Supplemental Methods. Research using these deidentified data has been deemed exempt from institutional review board review under the terms and conditions of Salus institutional review board number: 19-042. The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

RESULTS

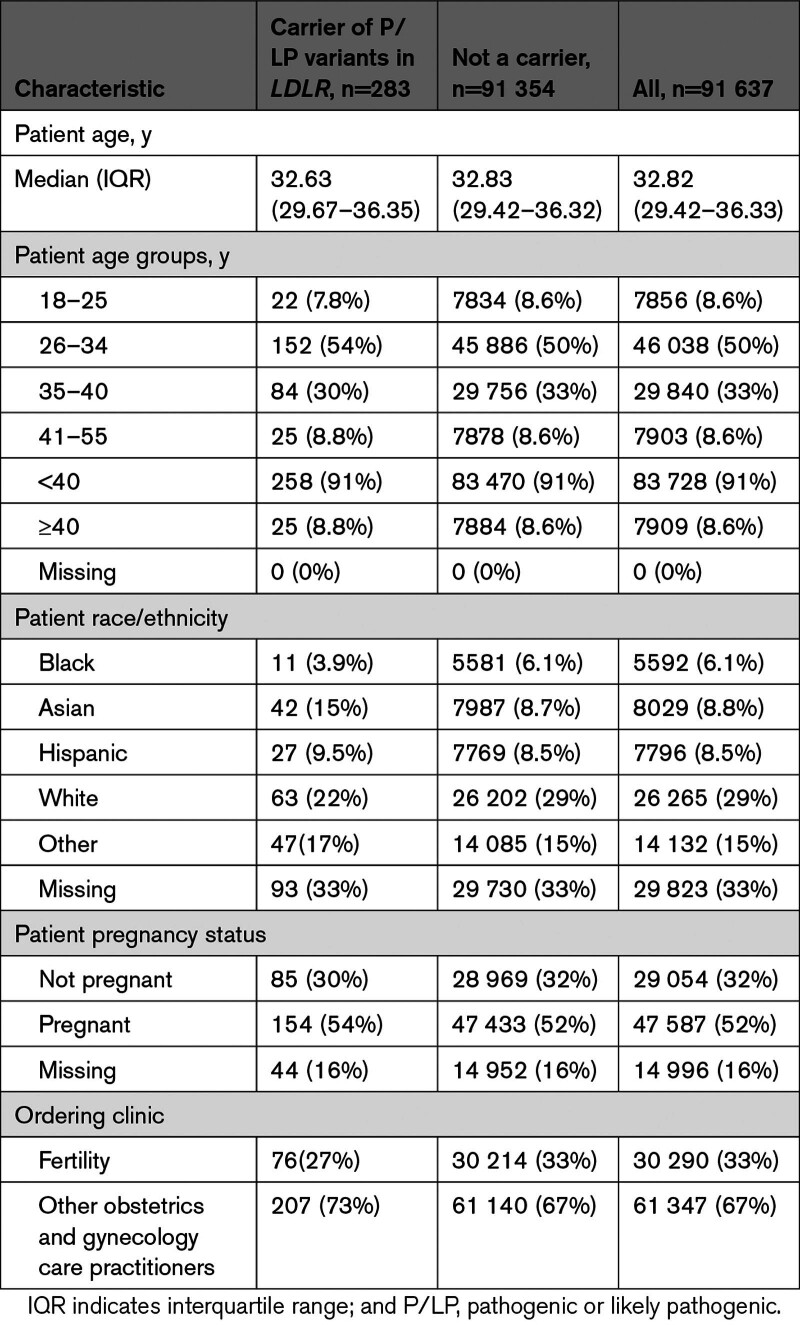

The analysis cohort included 91 637 carrier screening tests performed on women; 30 290 (33%) were requested through fertility clinics and 61 347 (67%) were requested by other obstetrics and gynecology care providers (Table 1). Fifty-two percent (47 587) of the carrier screening tests were performed during pregnancy, 32% (29 054) were outside of pregnancy, and for 16% (14 996), pregnancy status was not available. Race/ethnicity was recorded as Asian (8.8%), Black (6.1%), Hispanic (8.5%), White (29.0%), multiple or other race or ethnicity (15.0%), and missing (33.0%). Median age at the time of testing was 32.82 (IQR, 29.42–36.33) years and 83 728 (91.0%) were <40 years.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the Study Population

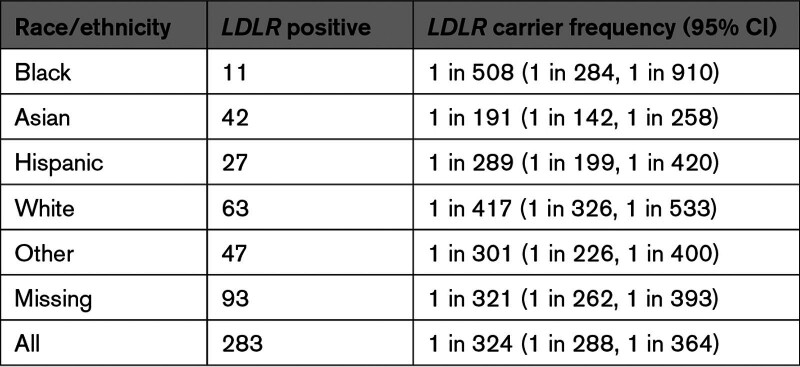

P/LP variants in LDLR were identified in 283 samples giving an overall carrier frequency of 1 in 324 (95% CI, 1 in 288, 1 in 364; Table 2). No individuals were identified as carriers for more than 1 P/LP variant in LDLR. Overall, there were significant differences in the rate of P/LP variants between the different racial/ethnic groups (P=0.002). LDLR carrier frequency was higher in the Asian group (1 in 191; 95% CI: 1 in 142, 1 in 258) compared with the White group (1 in 417; 95% CI, 1 in 326, 1 in 533; P<0.001) or the Black group (1 in 508; 95% CI, 1 in 284, 1 in 910; P=0.004; Table 2).

Table 2.

Carrier Frequency Stratified by Self-Reported Race/Ethnicity

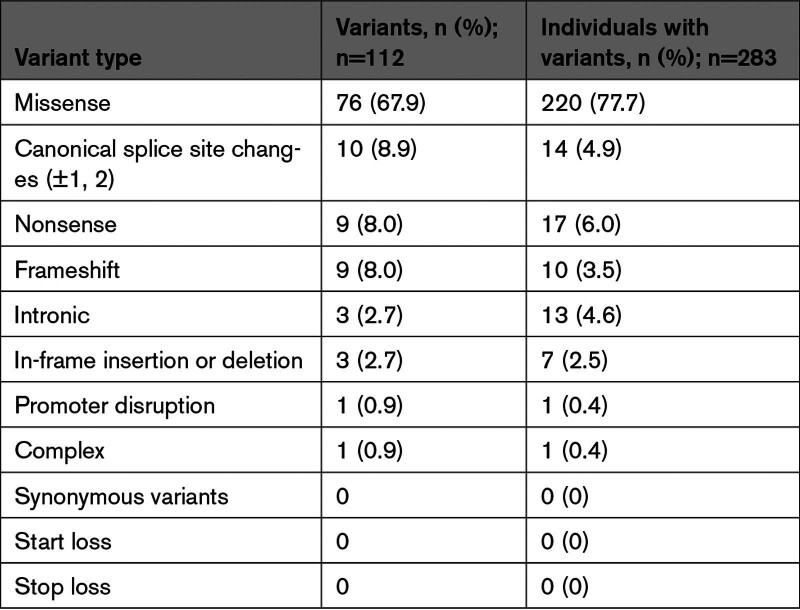

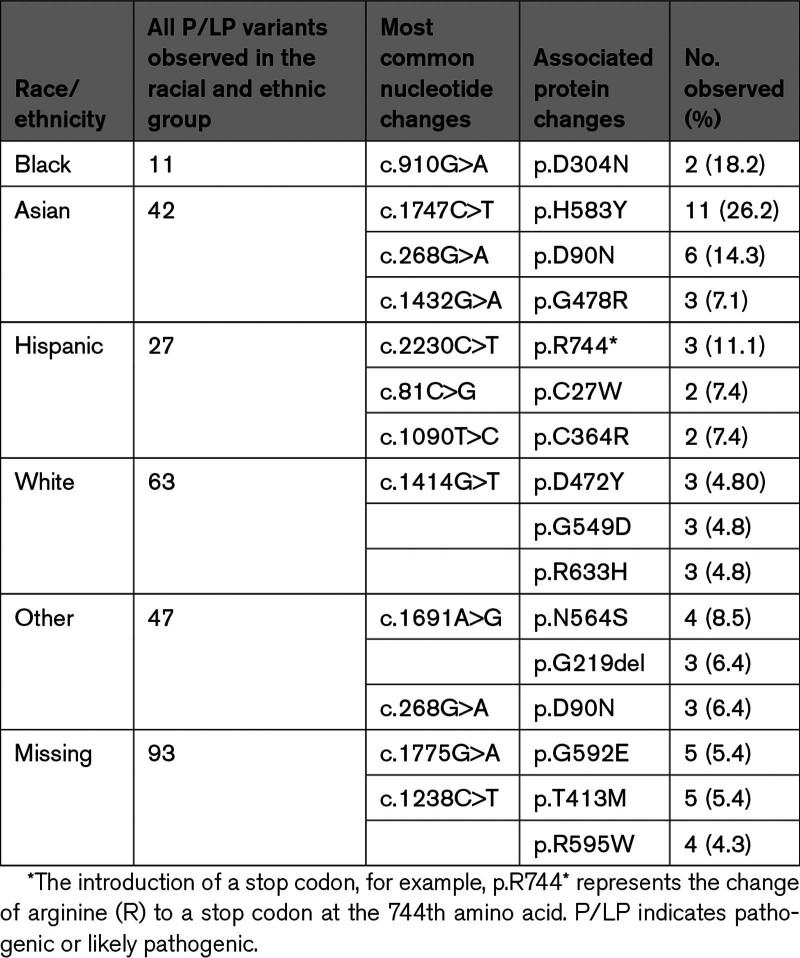

Of the 112 individual P/LP LDLR variants identified, 76 (67.9%) were missense, 10 (8.9%) were in canonical splice sites, 9 (8.0%) were nonsense, 9 (8.0%) were frameshift, 3 (2.7%) were in-frame, 3 (2.7%) were intronic, 1 (0.9%) was in a promoter sequence, and 1 (0.9%) was a complex variant (Table 3). Nonsense, canonical splice site, and frameshift variants (which are predicted to prevent the formation of a full-length transcript resulting in RNA degradation and no LDLR protein) accounted for 25.0% (n=28) of all unique variants and 14.5% (n=41) of all individuals identified with a P/LP variant (Table 3). We found no P/LP synonymous variants. Of the identified VUS synonymous variants, there were no alternate nucleotide sequence changes that would be considered a P/LP synonymous variant at the same codon. The 5 most common P/LP variants overall were p.H583Y (n=16; 5.6%), p.D90N (n=12; 4.2%), p.N564S (n=11; 3.9%), p.595W (n=9; 3.2%) and p.G592E (n=8; 2.8%) (Table S1). The most common P/LP variants differed among racial and ethnic groups (Table 4).

Table 3.

Type of Pathogenic or Likely Pathogenic Variant Identified

Table 4.

The Most Common P/LP Variants and the No. of Times They Were Observed, Stratified by Reported Race and Ethnicity

DISCUSSION

In our study, we found 1 in 324 samples submitted for reproductive carrier screening was associated with a P/LP variant in the LDLR gene. LDLR carrier frequency was significantly higher in the Asian group (1 in 191) compared with the White group (1 in 417) or the Black group (1 in 508) with differences in the specific variants present in these population subgroups. Importantly, our findings are based on LDLR sequencing in a racially and ethnically diverse cohort of over 90 000 female individuals.

There are only a few studies that have determined the prevalence of FH-associated genes in unselected populations, and there have been substantial differences in the estimates, probably reflecting differences between subpopulations.18 Benn et al,19 estimated a frequency of FH causal variants of 1 in 217 in a Danish population but only a small proportion were attributed to variants in LDLR. Bjornsson et al,20 reported whole genome sequencing results for an Icelandic population and found only 1 in 836 with variants in LDLR, APOB, or PCSK9. Abul-Husn et al,21 reported exome screening for 3 FH genes (LDLR, APOB, and PCSK9) for 12 298 patients with cardiovascular disease (CVD) plus 35 138 controls without disease ascertained through a US Health system. They identified P/LP variants in any of the 3 genes in 1 in 131 for those with CVD. In the control population, without CVD, they observed variants in 1 in 300 individuals. For LDLR alone, the variant frequency was 1 in 901 control individuals. In their study, 98% of participants were described as White and there was a substantial Amish component.21 O’Brien et al,22 offered community-based screening in Oregon for a panel of genes, including LDLR, at no cost to participants, 84% of whom self-identified as White people. Successful next-generation sequencing was performed on 13 760 samples. P/LP variants in LDLR were identified in 0.3% of participants which is similar to the carrier frequency found in our study population.22

For the P/LP variants identified by us, 25.0% were predicted to be null variants. Null variants (ie, nonsense, frameshift, canonical splice site) result in premature stop codons with nonsense-mediated decay, resulting in no functional protein being produced. These variants can be expected to result in severe phenotypes. For many other variants, the prediction of protein activity is challenging. It is difficult to draw conclusions about the severity of the phenotype for each of these variants because they may have a complex functional effect. For example, a missense variant could result in decreased trafficking to the cell membrane and a partial reduction in function, or it could also result in complete disruption in cell membrane trafficking with no protein function. However, not all laboratories agree on the curation of some of the LDLR variants, which may present as discrepancies between data sets.23 For example, both p.P699L and p.R574C have been reported as VUS and LP/P by the laboratories submitting to ClinVar. Six variants that have recently been classified as VUS by ClinGen were excluded from our study, reflecting evolving criteria for classification.11 Moreover, the phenotype associated with some P/LP variants in LDLR may depend not only on the specific variants present but also other genes that are associated with lipid levels.6 For variants that are suspected to partially reduce receptor activity, given that LDL-C measurement, clinical evaluation, dietary control, and safe, low-cost medications are available, we believe it is important to report these variants.

Although the American Heart Association recommends all adults aged 20 years and older have cholesterol (and other risk factors) evaluated every 4 to 6 years, testing is underutilized.24 Moreover, there is a range of LDL-C levels associated with FH and not all adults with FH have an LDL-C level above the diagnostic cutoff of 190 mg/dL.25 Identification of FH, through LDL-C levels may be more difficult in older adults because there is an age-related increase and therefore greater overlap in levels for people with and without FH. Accordingly, the diagnosis of FH is typically made based on a combination of family history, clinical examination findings, and LDL-C levels with, or without, genetic testing.26 However, the presence of a pathogenic FH gene variant alone has also been considered sufficient to make the diagnosis of FH, irrespective of the patient’s clinical features.26 These current testing strategies only identify ≈15% of individuals with FH and often times the diagnosis is only made once there is overt CVD, highlighting the need for a more proactive approach.27 It has been pointed out that while there is a need for an effective approach to screening for FH, the optimal approach has remained elusive.6

The US Preventive Services Task Force recommends statins for prevention of CHD in adults aged 40 to 75 years who have ≥1 CVD risk factors.28,29 These guidelines do not specially address individuals ascertained as high-risk primarily through genetic testing. However, the American Heart Association notes that FH is underdiagnosed, and treatment should involve the use of statins and other cholesterol-lowering drugs may also be indicated.30 People with FH have an excellent prognosis if the condition is identified early and treated appropriately.31 US national guidelines for cholesterol screening and for treatment of FH are directed at the nonpregnant population and specific considerations are needed for people who are identified with FH in pregnancy.

The inclusion of genes associated with FH in reproductive carrier screening offers another pathway toward early identification of some individuals with FH. In our study, the average age of the population was 33 years. A practical reality is that, in the United States, most reproductive carrier screening is provided to women during pregnancy with sequential testing of partners only when there is a positive test result.32 We have previously advocated greater use of early, preconception carrier screening with testing of both reproductive partners.33,34 Identification of FH in women who are pregnant or considering pregnancy would allow early treatment for their FH (after discontinuation of breastfeeding), and assessment of the risk for HoFH in the fetus by testing of her reproductive partner. Given the higher incidence and earlier onset of cardiovascular disease in men, the provision of early genetic-based screening for males can be expected to be useful in assessing their personal predisposition to cardiovascular disease as well as assessing risk for their children. Broader application of a genetic screening panel that includes FH-associated genes should also precipitate cascade testing in the family and thereby recognition of additional at-risk individuals. Importantly, only 1 of the 3 genes most commonly associated with FH were included in the carrier screening panel. Therefore, testing for other genes associated with FH (such as APOB and PCSK9) should be considered for patients with a phenotype suggestive of FH who do not have a P/LP in LDLR.

Strengths of our study include the large sample size and the use of sequencing instead of genotyping for specific variants. The population is likely to have been substantially unselected although we cannot exclude the possibility that some referrals may have come from people with known FH or with a family history. However, generally, for patients receiving broad-based reproductive carrier screening such as this 274-gene panel, it is not feasible to provide detailed information about all of the individual conditions as part of pretest counseling. Moreover, the detection of disorders that may manifest in the tested individual, although relatively common, has not been extensively presented to patients.35

A limitation of this study is that we did not include sequencing of other FH genes (eg, APOB and PCSK9). Additionally, not all P/LP changes will be detected; sequencing is limited to exons and 10 bases in adjacent introns. Deletions and duplications were not routinely evaluated, but in a recent study by Abul-Husn et al,21 only 1 copy number variant was reported among 99 LDLR variants. The phenotype associated with P/LP variants in LDLR will depend not only on the specific variants present but also other genes that are associated with lipid levels.6 Our study did not include follow-up of the screen-positive patients. We, therefore, do not know cholesterol levels, clinical findings, or the extent to which there may have been testing in partners or additional family members.

Additional studies are needed to correlate specific FH gene variants with LDL-C levels and disease severity. It is also possible that the identification of specific FH gene variants will provide information that helps determine the most effective drug.36 Null variants may require different therapeutic approaches compared with variants associated with some residual LDLR protein activity.

In summary, we point out that some broad-based reproductive carrier screening panels include dyslipidemia genes and, specifically, that P/LP variants in the LDLR are identified. Expansion of the use of reproductive carrier screening presents a new approach to the early identification of individuals predisposed to cardiovascular disease in addition to the chance of having a child with FH. Communication of this carrier status to patients and their care providers provides the opportunity for early cholesterol testing, the option of lifestyle modifications, and where appropriate, medication.

ARTICLE INFORMATION

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Urmi Sengupta, PhD, from Natera, Inc, for assistance with the development of the article.

Sources of Funding

This study was funded by Natera, Inc.

Disclosures

Drs Souter, Gall, Wang and B. Prigmore, E. Becraft, and S. Brummitt are employees of Natera, Inc with stocks or options to own stocks in the company. P. Benn is a consultant for Natera, Inc with options to own stocks in the company. Natera, Inc also covers travel expenses to educational meetings.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental Methods

Table S1

Reference 37

Supplementary Material

Nonstandard Abbreviations and Acronyms

- CVD

- cardiovascular disease

- FH

- familial hypercholesterolemia

- HeFH

- heterozygous familial hypercholesterolemia

- HoFH

- homozygous familial hypercholesterolemia

- LDL-C

- low-density lipoprotein cholesterol

- LDLR

- low-density lipoprotein receptor

- P/LP

- pathogenic or likely pathogenic

For Sources of Funding and Disclosures, see page 150.

Supplemental Material is available at https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/suppl/10.1161/CIRCGEN.123.004457.

Contributor Information

Emily Becraft, Email: ebecraft@natera.com.

Samantha Brummitt, Email: sbrummitt@natera.com.

Brittany Prigmore, Email: bprigmore@natera.com.

Yang Wang, Email: ywang@natera.com.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ison HE, Knowles JW. Familial hypercholesterolemia. In: GeneReviews®. 2014. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK174884/ [Google Scholar]

- 2.Raal FJ, Santos RD. Homozygous familial hypercholesterolemia: current perspectives on diagnosis and treatment. Atherosclerosis. 2012;223:262–268. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2012.02.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sturm AC, Knowles JW, Gidding SS, Ahmad ZS, Ahmed CD, Ballantyne CM, Baum SJ, Bourbon M, Carrie A, Cuchel M, et al. Clinical genetic testing for familial hypercholesterolemia: JACC Scientific Expert Panel. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;72:662–680. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.05.044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nemati MH, Astaneh B, Joubeh A. Triple coronary artery bypass graft in a 10-year-old child with familial hypercholesterolemia. Gen Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2009;57:94–97. doi: 10.1007/s11748-008-0335-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Widhalm K, Binder CB, Kreissl A, Aldover-Macasaet E, Fritsch M, Kroisboeck S, Geiger H. Sudden death in a 4-year-old boy: a near-complete occlusion of the coronary artery caused by an aggressive low-density lipoprotein receptor mutation (W556R) in homozygous familial hypercholesterolemia. J Pediatr. 2011;158:167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gidding SS, Champagne MA, de Ferranti SD, Defesche J, Ito MK, Knowles JW, McCrindle B, Raal F, Rader D, Santos RD, et al. ; American Heart Association Atherosclerosis, Hypertension, and Obesity in Young Committee of Council on Cardiovascular Disease in Young, Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing, Council on Functional Genomics and Translational Biology, and Council on Lifestyle and Cardiometabolic Health. The agenda for familial hypercholesterolemia: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2015;132:2167–2192. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Luirink IK, Wiegman A, Kusters DM, Hof MH, Groothoff JW, de Groot E, Kastelein JJP, Hutten BA. 20-Year follow-up of statins in children with familial hypercholesterolemia. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:1547–1556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nordestgaard BG, Chapman MJ, Humphries SE, Ginsberg HN, Masana L, Descamps OS, Wiklund O, Hegele RA, Raal FJ, Defesche JC, et al. ; European Atherosclerosis Society Consensus Panel. Familial hypercholesterolaemia is underdiagnosed and undertreated in the general population: guidance for clinicians to prevent coronary heart disease: consensus statement of the European Atherosclerosis Society. Eur Heart J. 2013;34:3478–3490a. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/eht273 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Versmissen J, Oosterveer DM, Yazdanpanah M, Defesche JC, Basart DC, Liem AH, Heeringa J, Witteman JC, Lansberg PJ, Kastelein JJ, et al. Efficacy of statins in familial hypercholesterolaemia: a long term cohort study. BMJ. 2008;337:a2423. doi: 10.1136/bmj.a2423 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grundy SM, Stone NJ, Bailey AL, Beam C, Birtcher KK, Blumenthal RS, Braun LT, de Ferranti S, Faiella-Tommasino J, Forman DE, et al. 2018 AHA/ACC/AACVPR/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/ADA/AGS/APhA/ASPC/NLA/PCNA Guideline on the management of blood cholesterol: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2019;139:e1082–e1143. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000625 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chora JR, Iacocca MA, Tichy L, Wand H, Kurtz CL, Zimmermann H, Leon A, Williams M, Humphries SE, Hooper AJ, et al. ; ClinGen Familial Hypercholesterolemia Expert Panel. The Clinical Genome Resource (ClinGen) Familial Hypercholesterolemia Variant Curation Expert Panel consensus guidelines for LDLR variant classification. Genet Med. 2022;24:293–306. doi: 10.1016/j.gim.2021.09.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.EAS Familial Hypercholesterolaemia Studies Collaboration (FHSC). Global perspective of familial hypercholesterolaemia: a cross-sectional study from the EAS Familial Hypercholesterolaemia Studies Collaboration (FHSC). Lancet. 2021;398:1713–1725. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01122-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sarraju A, Knowles JW. Genetic testing and risk scores: impact on familial hypercholesterolemia. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2019;6:5. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2019.00005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Beheshti SO, Madsen CM, Varbo A, Nordestgaard BG. Worldwide prevalence of familial hypercholesterolemia: meta-analyses of 11 million subjects. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;315:e20–e21. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2020.10.075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bellows BK, Khera AV, Zhang Y, Ruiz-Negron N, Stoddard HM, Wong JB, Kazi DS, de Ferranti SD, Moran AE. Estimated yield of screening for heterozygous familial hypercholesterolemia with and without genetic testing in US adults. J Am Heart Assoc. 2022;11:e025192. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.121.025192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gregg AR, Aarabi M, Klugman S, Leach NT, Bashford MT, Goldwaser T, Chen E, Sparks TN, Reddi HV, Rajkovic A, et al. ; ACMG Professional Practice and Guidelines Committee. Screening for autosomal recessive and X-linked conditions during pregnancy and preconception: a practice resource of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG). Genet Med. 2021;23:1793–1806. doi: 10.1038/s41436-021-01203-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sagaser KG, Malinowski J, Westerfield L, Proffitt J, Hicks MA, Toler TL, Blakemore KJ, Stevens BK, Oakes LM. Expanded carrier screening for reproductive risk assessment: an evidence-based practice guideline from the National Society of Genetic Counselors. J Genet Couns. 2023;32:540–557. doi: 10.1002/jgc4.1676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brunham LR, Hegele RA. What is the prevalence of familial hypercholesterolemia? Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2021;41:2629–2631. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.121.316862 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Benn M, Watts GF, Tybjaerg-Hansen A, Nordestgaard BG. Mutations causative of familial hypercholesterolaemia: screening of 98 098 individuals from the Copenhagen General Population Study estimated a prevalence of 1 in 217. Eur Heart J. 2016;37:1384–1394. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehw028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bjornsson E, Thorgeirsson G, Helgadottir A, Thorleifsson G, Sveinbjornsson G, Kristmundsdottir S, Jonsson H, Jonasdottir A, Jonasdottir A, Sigurethsson A, et al. Large-scale screening for monogenic and clinically defined familial hypercholesterolemia in Iceland. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2021;41:2616–2628. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.120.315904 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Abul-Husn NS, Manickam K, Jones LK, Wright EA, Hartzel DN, Gonzaga-Jauregui C, O’Dushlaine C, Leader JB, Lester Kirchner H, Lindbuchler DM, et al. Genetic identification of familial hypercholesterolemia within a single U.S. health care system. Science. 2016;354:aaf7000. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf7000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.O’Brien TD, Potter AB, Driscoll CC, Goh G, Letaw JH, McCabe S, Thanner J, Kulkarni A, Wong R, Medica S, et al. Population screening shows risk of inherited cancer and familial hypercholesterolemia in Oregon. Am J Hum Genet. 2023;110:1249–1265. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2023.06.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Safarova MS, Klee EW, Baudhuin LM, Winkler EM, Kluge ML, Bielinski SJ, Olson JE, Kullo IJ. Variability in assigning pathogenicity to incidental findings: insights from LDLR sequence linked to the electronic health record in 1013 individuals. Eur J Hum Genet. 2017;25:410–415. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2016.193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gao Y, Shah LM, Ding J, Martin SS. US trends in cholesterol screening, lipid levels, and lipid-lowering medication use in US adults, 1999 to 2018. J Am Heart Assoc. 2023;12:e028205. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.122.028205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Khera AV, Won HH, Peloso GM, Lawson KS, Bartz TM, Deng X, van Leeuwen EM, Natarajan P, Emdin CA, Bick AG, et al. Diagnostic yield and clinical utility of sequencing familial hypercholesterolemia genes in patients with severe hypercholesterolemia. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;67:2578–2589. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.03.520 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Umans-Eckenhausen MA, Defesche JC, Sijbrands EJ, Scheerder RL, Kastelein JJ. Review of first 5 years of screening for familial hypercholesterolaemia in the Netherlands. Lancet. 2001;357:165–168. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)03587-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dikilitas O, Sherafati A, Saadatagah S, Satterfield BA, Kochan DC, Anderson KC, Chung WK, Hebbring SJ, Salvati ZM, Sharp RR, et al. Familial hypercholesterolemia in the electronic medical records and genomics network: prevalence, penetrance, cardiovascular risk, and outcomes after return of results. Circ Genom Precis Med. 2023;16:e003816. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGEN.122.003816 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mangione CM, Barry MJ, Nicholson WK, Cabana M, Chelmow D, Coker TR, Davis EM, Donahue KE, Jaen CR, Kubik M, et al. ; US Preventive Services Task Force. Statin use for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease in adults: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA. 2022;328:746–753. doi: 10.1001/jama.2022.13044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Virani SS, Alonso A, Aparicio HJ, Benjamin EJ, Bittencourt MS, Callaway CW, Carson AP, Chamberlain AM, Cheng S, Delling FN, et al. ; American Heart Association Council on Epidemiology and Prevention Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Heart disease and stroke statistics-2021 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2021;143:e254–e743. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000950 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wilson PWF, Polonsky TS, Miedema MD, Khera A, Kosinski AS, Kuvin JT. Systematic review for the 2018 AHA/ACC/AACVPR/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/ADA/AGS/APhA/ASPC/NLA/PCNA Guideline on the Management of Blood Cholesterol: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;73:3210–3227. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.11.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Association AH. Familial Hypercholesterolemia (FH). 2020. https://www.heart.org/en/health-topics/cholesterol/causes-of-high-cholesterol/familial-hypercholesterolemia-fh

- 32.Committee opinion no. 691: carrier screening for genetic conditions. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;129:e41–e55. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001952 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Benn P. Correspondence on “Maternal carrier screening with single-gene NIPS provides accurate fetal risk assessments for recessive conditions” by Hoskovec et al. Genet Med. 2023;25:100902. doi: 10.1016/j.gim.2023.100902 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Souter V, Prigmore B, Becraft E, Repass E, Smart T, Sanapareddy N, Schweitzer M, Ortiz JB, Wang Y, Benn P. Reproductive carrier screening results with maternal health implications during pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2023;142:1208–1216. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000005318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Clevenger SK, Brandt JS, Khan SP, Shingala P, Carrick J, Aluwalia R, Heiman GA, Ashkinadze E. Rate of manifesting carriers and other unexpected findings on carrier screening. Prenat Diagn. 2023;43:117–125. doi: 10.1002/pd.6289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Santos RD, Stein EA, Hovingh GK, Blom DJ, Soran H, Watts GF, Lopez JAG, Bray S, Kurtz CE, Hamer AW, et al. Long-term Evolocumab in patients with familial hypercholesterolemia. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;75:565–574. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2019.12.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Richards S, Aziz N, Bale S, Bick D, Das S, Gastier-Foster J, Grody WW, Hegde M, Lyon E, Spector E, et al. ; ACMG Laboratory Quality Assurance Committee. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet Med. 2015;17:405–424. doi: 10.1038/gim.2015.30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.