Abstract

Equine infectious anemia virus (EIAV) contains the simplest genome among lentiviruses in that it encodes only three putative regulatory genes (S1, S2, S3) in addition to the canonical gag, pol, and env genes, presumably reflecting its limited tropism to cells of monocyte/macrophage lineage. Tat and Rev functions have been assigned to S1 and S3, respectively, but the specific function for the S2 gene has yet to be determined. Thus, the function of S2 in virus replication in vitro was investigated by using an infectious molecular viral clone, EIAVUK. Various EIAVUK mutants lacking S2 were constructed, and their replication kinetics were examined in several equine cell culture systems, including the natural in vivo target equine macrophage cells. The EIAV S2 mutants showed replication kinetics similar to those of the parental virus in all of the tested primary and transformed equine cell cultures, without any detectable reversion of mutant genomes. The EIAVUK mutants also showed replication kinetics similar to those of the parental virus in an equine blood monocyte differentiation-maturation system. These results demonstrate for the first time that the EIAV S2 gene is not essential and does not appear to affect virus infection and replication properties in target cells in vitro.

Equine infectious anemia virus (EIAV) is a member of the lentivirus subfamily of retroviruses and causes a persistent infection and chronic disease in horses worldwide. EIAV is a strictly monocyte/macrophage-tropic lentivirus that, while infecting monocytes, replicates predominately in tissue macrophages (17). The genetic organization of EIAV is relatively simple compared with that of other lentiviruses in that the EIAV genome contains only three accessory genes, initially termed S1, S2, and S3, in addition to the standard gag, pol, and env genes common to all retroviruses. The S1 open reading frame (ORF) encodes the viral Tat protein, a transcription trans activator that acts on the viral long-terminal-repeat (LTR) promoter element to stimulate expression of all viral genes. The S3 ORF encodes a Rev protein, a posttranscriptional trans activator that acts by interacting with its target RNA sequence, named the Rev-responsive element (RRE), to regulate viral structural gene expression (7, 15, 17, 18). The S2 ORF encodes a protein of unknown function that has no significant deduced amino acid sequence homology to any of the accessory proteins described to date for animal or human lentiviruses.

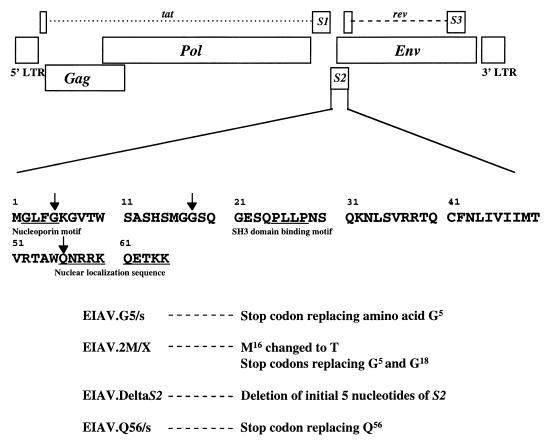

The S2 gene is located in the pol-env intergenic region immediately following the second exon of Tat and overlapping the amino terminus of the Env protein (Fig. 1). It encodes a 65-amino-acid protein, with a calculated molecular mass of a 7.2 kDa, which is in good agreement with the size of an in vitro translation product (22). S2 is evidently synthesized in the late phase of the viral replication cycle by ribosomal leaky scanning of a tricistronic mRNA encoding Tat, S2 protein, and Env, respectively (3, 17). The ORF coding for the S2 protein of EIAV is highly conserved in all published EIAV sequences and contains three potential functional motifs (Fig. 1): GLFG (putative nucleoporin motif) (8), PXXP (putative SH3 domain binding motif) (12), and RRKQETKK (putative nuclear localization sequence) (17). Antibodies to S2 protein can be found in sera from experimentally and naturally infected horses, indicating that S2 is expressed during EIAV replication in vivo (22). These observations suggest that S2 is likely to perform an important role in the virus life cycle.

FIG. 1.

Schematic representation of EIAV S2 gene and mutant clones derived from EIAVUK. The genomic structure of EIAV proviral DNA is shown at the top; the complete deduced amino acid sequence of the putative S2 protein is shown in single-letter amino acid code at the bottom. Stop codons (indicated by arrows) were introduced into various positions in the EIAV S2 gene to generate the specific mutant virus strains. To produce the indicated S2 mutations, two adjacent fragments were amplified by PCR spanning the whole S2 gene. One of the two resultant PCR products carried the specific substitution or deletion mutations incorporated into a reaction primer. The flanking PCR products were phosphorylated, ligated, and then used as a template for a second round of PCR with the outer primer pair. The final full-length PCR product was digested with NcoI and Bpu1102I, cloned into EIAVUK previously digested with NcoI and Bpu1102I. All plasmid clones were sequenced to verify introduced mutations or deletions and to ensure the integrity of the PCR-amplified sequence.

To elucidate the function of S2 in virus replication, we investigated the in vitro replication properties of selected EIAV S2 mutants in the background of a recently characterized infectious EIAV molecular clone, designated EIAVUK (6). The evaluation of S2 function in EIAV replication was investigated by introducing specific mutations into the S2 gene of this molecular clone, EIAVUK. A PCR-ligation-PCR technique was developed to introduce specific substitutions or deletions into the S2 gene in the context of EIAVUK (Fig. 1). Mutations were designed such that they did not disrupt the second exon of Tat 10 bp upstream of the S2 initiation sequence, the envelope initiator codon just 23 bp downstream of the S2 start codon sequence, or the putative Rev-responsive element (RRE) sequences that have been mapped to both the 5′ and 3′ ends of the env gene (1, 15). A panel of clones with substitutions that introduce one or more premature stop codons (clones EIAV.2M/X, EIAV.G5/s, and EIAV.Q56/s) or with a deletion of the first 5 nucleotides of S2 (clone EIAV.DeltaS2) to shift the S2 ORF were produced (Fig. 1).

Previous studies to determine the role of the EIAV DU gene in virus replication demonstrated the importance of comparing mutant viral growth properties in different types of equine cells (14). Therefore, viral replication was examined in vitro by using a panel of well-characterized equine primary cell cultures and transformed cell lines routinely used for in vitro replication of EIAV. These included the equine dermal (ED) cell line, primary fetal equine kidney (FEK) cells, equine blood monocyte-derived macrophage (MDM) cells (the natural target cell), and an equine blood monocyte differentiation-maturation culture system.

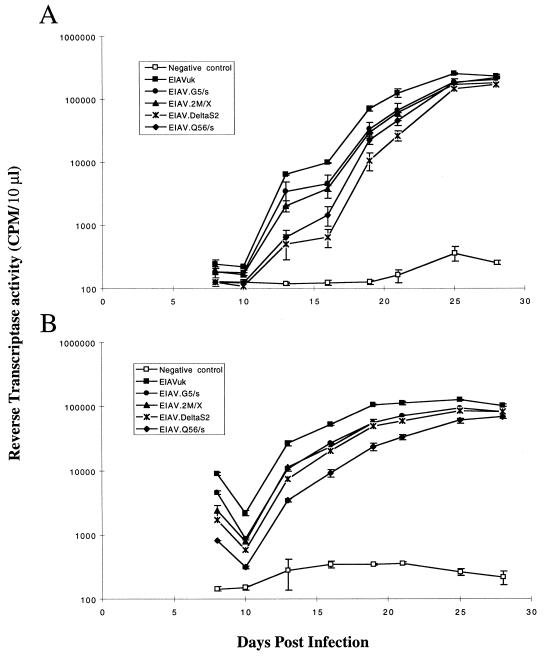

Transfections of FEK and ED cells were performed with 1 μg of parental EIAVUK or S2 mutant EIAV proviral clone DNA by using 10 μl of Lipofectamine reagent (Gibco BRL). Aliquots of the tissue culture supernatant were taken at periodic intervals and analyzed by using a standard reverse transcriptase (RT) assay as a measure of virus production (14). As summarized in the results shown in Fig. 2, transfections of FEK and ED cells by both the parental EIAVUK and EIAV S2 mutant clones resulted in productive infections, as indicated by production of RT activity in culture supernatant (Fig. 2). While the EIAV S2 mutant viruses were replication competent, their replication was consistently delayed compared to replication of parental EIAVUK (Fig. 2). For example, to reach an RT activity level of 10,000 cpm/10 μl, the various S2 mutants displayed a 1- to 3-day lag in FEK cells and a 1- to 5-day delay in ED cells relative to the parental EIAVUK in the respective cell types. S2 mutants EIAV.Q56/s and EIAV.DeltaS2 appeared to be the most severely delayed for virus replication following transfection. These relative replication kinetics were consistently demonstrated in three independent transfection experiments. Cell culture supernatants for each EIAV S2 mutant were used to examine virus for reversion by sequencing products obtained by RT-PCR of RNA templates derived from pelleted virions. Sequencing data confirmed that no reversion had occurred (data not shown). Thus, these data demonstrate that the EIAV S2 gene is dispensable for virus replication in dividing equine primary and transformed cells in vitro.

FIG. 2.

Replication kinetics of parental EIAVUK and mutant S2 viruses in transfected FEK (A) and ED (B) cell cultures. The FEK and ED cells cultured were individually transfected with 1 μg of EIAVUK, EIAV.G5/s, EIAV/2M/X, EIAV.DeltaS2, or EIAV.Q56/s proviral DNA, and each transfected cell type was then passaged for 1 month. Virus production was monitored by assaying supernatant RT activity at various times posttransfection, as described previously (14). The data shown represent an average of at least two experiments, with variation indicated by standard deviation bars.

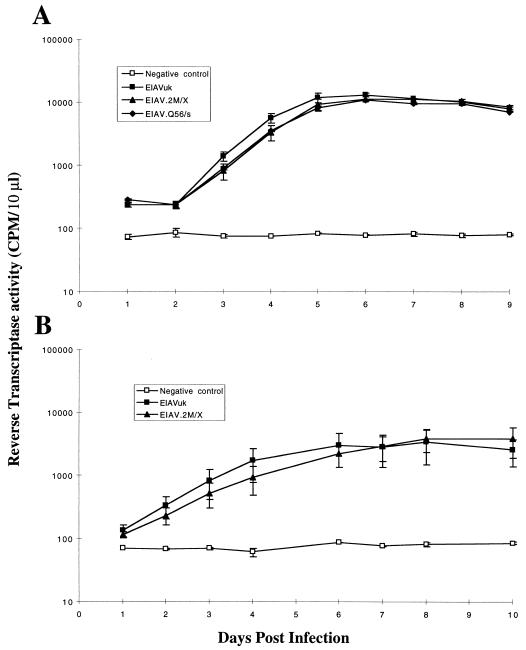

To determine the role of the viral S2 gene in replication in fully differentiated equine macrophages, the predominant in vivo target cell for EIAV, we next compared the replication kinetics of parental EIAVUK and S2 mutant virus stocks in cultures of primary equine macrophages. Virus stocks from wild-type and S2 mutant viruses were prepared with FEK cells by harvesting medium at 25 days posttransfection (as described in the legend to Fig. 2). The titers of the various virus stocks were determined for infectivity by using the standard infectious center assay for FEK cells (14), and MDM cells were infected in parallel with either the wild type or the S2 mutant at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 0.1 and assayed for virus replication as described above. The data in Fig. 3A demonstrate that the S2 mutant viruses replicated as efficiently as the parental EIAVUK in infected MDM cells. However, the initial replication of the S2 mutant viruses in MDM cells was slightly delayed compared to that of wild-type virus at the same MOI. Once again, PCR analyses of the RNA from progeny virus produced by the infected macrophages revealed no reversion of S2 mutations. The ability of the S2 mutants to replicate with kinetics similar to those of the parental EIAVUK demonstrated that the absence of S2 evidently does not substantially affect the ability of the virus to either infect or replicate in fully differentiated macrophages in vitro.

FIG. 3.

Replication kinetics of parental and S2 mutant viruses in equine MDM cells (A) and in a monocyte/macrophage differentiation-maturation system (B). Equine MDM cells were prepared from heparinized blood as described previously (20). Primary MDM cells were infected with either parental EIAVUK or the indicated mutant virus stock at an MOI of 0.01. Virus production following infection of equine MDM cells was monitored daily by measuring RT activity in the culture supernatant. For the monocyte/macrophage differentiation system, freshly purified equine peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were incubated in Teflon wells (Savillex, Minnetonka, Minn.) to maintain nonadherent monocytes at a density of 3 × 106 cells/per ml in MEMα medium (Gibco BRL) without serum. Subsequently, PBMCs were infected at an MOI of 0.01 ICD per cell in triplicate wells with EIAVUK and EIAV.2M/X, separately, for 2 h at 37°C with 6% CO2. Then, the PBMCs were washed twice to remove any extracellular virus and plated back into Teflon wells again in MEMα medium with 10% horse serum overnight at 37°C with 6% CO2. On the following day, the PBMCs were seeded into 48-well tissue culture plates (Corning) and incubated under the conditions described above. One day later, the nonadherent and loosely adherent cells were removed by two washes with the medium and the adherent monocytes/macrophages were further incubated at 37°C with 6% CO2. Virus production was monitored daily by measuring RT activity in the culture supernatant.

Several studies have demonstrated that while EIAV can infect equine blood monocytes, differentiation of monocytes to macrophages is required to produce a productive infection (16, 20, 23). To determine if the EIAV S2 gene might be important for the initial infection of equine monocytes or for the subsequent transition to a productive infection in macrophages, we next examined the replication properties of the EIAV.2M/X mutant virus and the parental EIAVUK in an equine monocyte/macrophage differentiation cell culture system (16, 20). Briefly, cultures of purified equine blood monocytes in nonadherent Teflon wells were infected in parallel with the same MOI of either the parental EIAVUK or the EIAV.2M/X mutant virus. After 24 h in Teflon wells, the virus-infected monocytes were then transferred to plastic wells, where they became adherent differentiated macrophages. The levels of virus replication in each macrophage culture were monitored by measuring RT production as described above. As shown in Fig. 3B, the EIAV.2M/X mutant virus demonstrated replication kinetics similar to those of EIAVUK in the in vitro monocyte/macrophage differentiation system. These results indicate that the S2 gene of EIAV is not required for infection of equine blood monocytes and does not perform an essential role in the transition of latency in monocytes to a productive infection in differentiated macrophages in vitro.

A large number of accessory gene products have been identified in animal and human lentivirus genomes. These include Rev, Tat, Vif, Vpr, Vpu, Nef, Vpx, and ORF A (11, 29, 30). The product of the S2 ORF of EIAV is the only lentivirus accessory protein which has to date remained uncharacterized. In this study, we examined in vitro replication properties of EIAV mutant viruses lacking a functional S2 gene in the ED cell line, in primary FEK cells, in equine MDM cells, and in a monocyte/macrophage differentiation culture system. Although EIAV mutants lacking an S2 gene were in certain cell types slightly delayed in replication compared with wild-type EIAV, the final viral titers of S2 mutants eventually reached levels similar to those of wild-type EIAV. The dispensability of the S2 gene for virus replication is consistently observed in all of these cell types, indicating that the S2 gene is not required for virus replication in vitro.

The S2 gene product of EIAV appears to have no obvious sequence homology to other functionally characterized proteins in general nor to accessory gene products in other lentiviruses in particular, which makes it extremely difficult to predict S2 protein function. However, it has been shown that lentivirus accessory proteins may share highly conserved functions in the absence of substantial amino acid sequence homology (4, 9, 19, 24). Comparisons of EIAV S2 to other lentivirus accessory genes can be used to evaluate potential functions for the S2 protein. A Vif gene has been identified in all lentiviruses except EIAV (11). While it has been hypothesized that the EIAV S2 gene product may be a Vif homolog (4), current studies do not reveal any role in virus assembly, as reported for other lentivirus Vif proteins (2, 25, 26). The similarities in genomic location of EIAV S2 and the Vpu gene of other lentiviruses and the relatively high serine-threonine content with the potential for phosphorylation in both proteins are compatible with the concept that the S2 protein may function in virion assembly and release, as has been described for the Vpu protein (17, 27, 28). Finally, the EIAV S2 gene product contains a putative nuclear localization signal at its C terminus, similar to the Vpr of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) and simian immunodeficiency virus. Several roles have been suggested for Vpr protein in HIV-1 regulation, including modest upregulation of viral gene expression, enhancement of the nuclear migration of the preintegration complex in nondividing cells, and arrest of the host cell cycle leading to differentiation (5, 10, 13, 21). However, the studies described here indicate that the absence of the EIAV S2 gene does not markedly affect the levels of virus infectivity in dividing and nondividing cells in vitro, nor does it detectably alter the transition of latently infected monocytes to productively infected macrophages in a cell culture system. These observations suggest that among lentivirus accessory genes the EIAV S2 gene may encode a unique protein function or that the function of the S2 protein may be redundant with the function of other EIAV structural or regulatory proteins, as reported for HIV-1 Vpr and Gag proteins in nuclear migration of the preintegration complex (10). Finally, it should be emphasized that while these studies establish that the S2 gene is not essential for virus replication in vitro, the functional role of the S2 protein in EIAV replication and pathogenesis in infected horses remains to be determined.

Acknowledgments

We thank Michelle Raabe for excellent assistance and advice in culturing equine monocytes/macrophages.

The work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant R01CA49296.

REFERENCES

- 1.Belshan M, Harris M E, Shoemaker A E, Hope T J, Carpenter S. Biological characterization of Rev variation in equine infectious anemia virus. J Virol. 1998;72:4421–4426. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.5.4421-4426.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Borman A M, Quillent C, Charneau P, Dauguet C, Clavel F. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Vif− mutant particles from restrictive cells: role of Vif in correct particle assembly and infectivity. J Virol. 1995;69:2058–2067. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.4.2058-2067.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carroll R, Derse D. Translation of equine infectious anemia virus bicistronic tat-rev mRNA requires leaky ribosome scanning of the tat CTG initiation codon. J Virol. 1993;67:1433–1440. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.3.1433-1440.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clements J, Zink M C. Molecular biology and pathogenesis of animal lentivirus infections. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1996;9:100–117. doi: 10.1128/cmr.9.1.100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cohen E A, Terwilliger E F, Jalinoos Y, Proulx J, Sodroski J G, Haseltine W A. Identification of HIV-1 Vpr product and function. J Acquired Immune Defic Syndr. 1990;3:11–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cook R F, Leroux C, Cook S J, Berger S L, Lichtenstein D L, Ghabrial N N, Montelaro R C, Issel C J. Development and characterization of an in vivo pathogenic molecular clone of equine infectious anemia virus. J Virol. 1998;72:1383–1393. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.2.1383-1393.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dorn P, DaSilva L, Martarano L, Derse D. Equine infectious anemia virus tat: insights into the structure, function, and evolution of lentivirus trans-activator proteins. J Virol. 1990;64:1616–1624. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.4.1616-1624.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fritz C C, Zapp M L, Green M R. A human nucleoporin-like protein that specifically interacts with HIV Rev. Nature. 1995;376:530–533. doi: 10.1038/376530a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harmache A, Bouyac M, Audoly G, Hieblot C, Peveri P, Vigne R, Suzan M. The vif gene is essential for efficient replication of caprine arthritis encephalitis virus in goat synovial membrane cells and affects the late steps of the virus replication cycle. J Virol. 1995;69:3247–3257. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.6.3247-3257.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Heinzinger N K, Bukrinsky M I, Haggerty S A, Ragland A M, Kewalramani V, Lee M A, Gendelman H E, Ratner L, Stevenson M, Emerman M. The Vpr protein of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 influences nuclear localization of viral nucleic acids in non-dividing host cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:7311–7315. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.15.7311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Joag S V, Stephens E B, Narayan O. Lentiviruses. In: Fields B N, Strauss S E, Knipe D N, Howley P M, editors. Virology. 3rd ed. Vol. 1. Philadelphia, Pa: Lippincott-Raven; 1996. pp. 1977–1996. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee C H, Saksela K, Mirza U A, Chait B T, Kuriyan J. Crystal structure of the conserved core of HIV-1 Nef complexed with a Src family SH3 domain. Cell. 1996;85:931–942. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81276-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Levy D N, Fernandes L S, Williams W V, Weiner D B. Induction of cell differentiation by human immunodeficiency virus 1 vpr. Cell. 1993;72:541–550. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90073-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lichtenstein D L, Rushlow K E, Cook R F, Raabe M L, Swardson C J, Kociba G J, Issel C J, Montelaro R C. Replication in vitro and in vivo of an equine infectious anemia virus mutant deficient in dUTPase activity. J Virol. 1995;69:2881–2888. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.5.2881-2888.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Martarano L, Stephens R, Rice N, Derse D. Equine infectious anemia virus trans-regulatory protein Rev controls viral mRNA stability, accumulation, and alternative splicing. J Virol. 1994;68:3102–3111. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.5.3102-3111.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Maury W. Monocyte maturation controls expression of equine infectious anemia virus. J Virol. 1994;68:6270–6279. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.10.6270-6279.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Montelaro R C, Ball J M, Rushlow K E. Equine retroviruses. In: Levy J A, editor. The Retroviridae. Vol. 2. New York, N.Y: Plenum Press; 1993. pp. 257–360. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Noiman A, Gazit A, Tori O, Sherman L, Miki T, Tronick S R, Yaniv A. Identification of sequences encoding the equine infectious anemia virus tat gene. Virology. 1990;176:280–288. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(90)90254-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Oberste M S, Gonda M A. Conservation of amino acid motifs in lentivirus Vif proteins. Virus Genes. 1992;6:95–102. doi: 10.1007/BF01703760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Raabe, M. R., C. J. Issel, and R. C. Montelaro. Equine monocyte derived macrophage cultures and their applications for infectivity and neutralization studies of equine infectious anemia virus. J. Virol. Methods, in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Rogel M E, Wu L I, Emerman M. The human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Vpr gene prevents cell proliferation during chronic infection. J Virol. 1995;69:882–888. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.2.882-888.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schiltz R L, Shih D S, Rasty S, Montelaro R C, Rushlow K E. Equine infectious anemia virus gene expression: characterization of the RNA splicing pattern and the protein products encoded by open reading frames S1 and S2. J Virol. 1992;66:3455–3465. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.6.3455-3465.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sellon D C, Walker K M, Russell K E, Perry S T, Covington P, Fuller F J. Equine infectious anemia virus replication is upregulated during differentiation of blood monocytes from acutely infected horses. J Virol. 1996;70:590–594. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.1.590-594.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shacklett B L, Luciw P A. Analysis of the vif gene of feline immunodeficiency virus. Virology. 1994;204:860–867. doi: 10.1006/viro.1994.1609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Simon J H, Malim M H. The human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Vif protein modulates the postpenetration stability of viral nucleoprotein complexes. J Virol. 1996;70:5297–5305. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.8.5297-5305.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Simon J H M, Southerling T E, Peterson J C, Meyer B E, Malim M H. Complementation of vif-defective human immunodeficiency virus type 1 by primate, but not nonprimate, lentivirus vif genes. J Virol. 1995;69:4166–4172. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.7.4166-4172.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Strebel K, Klimkait T, Maldarelli F, Martin M A. Molecular and biochemical analyses of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Vpu protein. J Virol. 1989;63:3784–3791. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.9.3784-3791.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Terwilliger E F, Cohen E A, Lu Y C, Sodroski J G, Haseltine W A. Functional role of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 vpu. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:5163–5167. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.13.5163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Trono D. HIV accessory proteins: leading roles for the supporting cast. Cell. 1995;82:189–192. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90306-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Waters A K, Parseval A P D, Lerner D L, Neil J C, Thompson F J, Elder J H. Influence of ORF2 on host cell tropism of feline immunodeficiency virus. Virology. 1996;215:10–16. doi: 10.1006/viro.1996.0002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]