Abstract

Xylene is the commonest clearing agent even though it is hazardous and costly. This study evaluated the clearing properties of coconut oil as an alternative cost-effective clearing agent for histological processes. Ten (10) prostate samples fixed in formalin were taken and each one was cut into 4 before randomly separating them into four groups (A, B, C and D). Tissues were subjected to ascending grades of alcohol for dehydration. Group A was cleared in xylene and Groups B, C, and D were cleared at varying times of 1hr 30mins, 3hrs, and 4hrs in coconut oil respectively before embedding, sectioning, and staining were carried out. Gross and histological features were compared. Results indicated a significant shrinkage in coconut oil-treated specimen compared with the xylene-treated specimen and only the tissues cleared in coconut oil for 4hrs were as rigid as the tissues cleared in xylene (p > 0.05). No significant difference was found in either of the sections when checked for cellular details and staining quality (p > 0.999). Coconut oil is an efficient substitute for xylene in prostate tissues with a minimum clearing time of 4hrs, as it is environmentally friendly and less expensive, but causes significant shrinkage to prostate tissue:

Keywords: Bernoulli’s principle, clearing agent, coconut oil, H&E staining, histological preparation, histopathology, hot-air oven, prostate organ, xylene

Introduction

Histological tissue processing remains the gold standard against which all technologies and methods are compared. 1 It is a physical process that involves chemical solutions reacting with biological specimens 2 for the purpose of discovering and defining the origin and causation of an illness through thorough patient examination and review of the test results. 3 The aim of tissue processing is to embed the tissue in a solid medium, 4 firm enough to support the tissue and give it sufficient rigidity to enable thin sections 5 to be cut, and yet, soft enough not to damage the knife or tissue.6,7 For any tissue specimen to undergo diagnosis, it must follow procedures which include fixation and tissue processing.6,8

Fixation is carried out immediately tissues are removed to preserve the shape and structural integrity of the tissue in a chemical 9 and present the tissues in a physical state to withstand subsequent treatments with various reagents.10,11 The most commonly used fixative is 10% neutral-buffered formalin 12 with the aim of preserving tissues in a life-like condition to prevent autolysis and putrefaction.7,13 Dehydration removes water from the tissues 14 using increasing grades of alcohol such as 70%, 80%, 90%, and absolute alcohol. 15 Other dehydrants including acetone and methanol can be used in the process of dehydration.14,16

Clearing is the process whereby alcohol is removed from a tissue 17 and replaced with a wax-dissolving substance. 1 This is because the dehydrating agent is immiscible with the impregnating medium. 18 The change in the appearance of tissue indicates the effectiveness of the clearing process 19 before infiltration. Infiltration eliminates the clearing agent from the tissue 20 by diffusion to enhance impregnation with the most commonly used impregnating medium; molten paraffin wax. 2 The wax, which has diffused into the tissue after replacing the clearing agent, gets deposited in the tissues.21,22 The clearing agent also enhances the translucency of tissues during microscopy when applied after staining due to its high refractive index. 23 The most commonly used clearing agent is xylene in tissue processing and staining.

Xylene is an aromatic hydrocarbon that occurs naturally in petroleum, coal tar and smoke from most combustion sources. 24 Approximately 95% of xylene is produced primarily through the catalytic reformation of petroleum. 25 It is used as a solvent in the manufacturing of chemicals, an ingredient in aviation fuel and gasoline, 26 and a feedstock in manufacturing various polymers, phthalic anhydride, isophthalic acid, terephthalic acid, and dimethyl terephthalate. 27

Xylene is the most recommended clearant due to properties such as its melting range (−47.87C to 13.26C). 28 It clears tissue rapidly (15–30 minutes) and is miscible with absolute alcohol 29 as well as paraffin. For mounting procedures, it can be used for celloidin sections because it does not dissolve it. 30 Xylene was the safest alternative in the 1950s however, evidence in the 1970s showed that its acute neurotoxicity was greater than benzene and toluene 28 which has led to research for suitable and safer alternatives.

Coconut oil is commercially derived from copra, which is the dried kernel of the coconut fruit. 31 It predominantly contains triglycerides with 86.5% saturated fatty acids, 5.8% monounsaturated fatty acids, and 1.8% polyunsaturated fatty acids.32,33 The saturated fatty acid component of coconut oil is primarily made up of seven different fatty acids which includes 44.6% lauric acid, 16.8% myristic acid, and 8.2% palmitic acids. 34 The only monounsaturated and polyunsaturated fatty acids are oleic acid and linoleic acid, respectively. Its color ranges from colorless to pale brownish-yellow 35 with a longer shelf life of up to 2 years (when stored at temperatures lower than 24.5°C) due to its resilience to high temperatures.34,36

This research was conducted to replace xylene with coconut oil due to the recent complaints of its harmful effects such as neurotoxicity, cardiac and kidney injury, cancer, blood dyscrasias, skin diseases, gastrointestinal disturbances, musculoskeletal system disorders, and bone marrow toxicity. 37 On account of the Occu-pational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) regulations, various xylene substitutes, such as limonene reagents and vegetable/mineral oils, were tried in the past to avoid xylene in the laboratory. 38 However, some of these substitutes have proven to be less effective for certain tissues and more expensive. 39 In this study, the clearing properties of coconut oil and xylene in prostate tissues were compared.

Materials and Methods

Study Design and Area

This experimental comparative study was conducted at the Pathology Laboratory of the HopeXchange Medical Center, situated in Kumasi, the regional capital of Ashanti Region.

Study Population

A total of 10 prostate organs were harvested from 10 rats and cut into four equal parts for this study hence a sample size of 40 tissues.

Procedure in Detail

Coconut oil with a peroxidative value of 0.23–0.57 was obtained from the Kejetia market and transported to the pathology laboratory of HopeXchange Medical Center prior to the study. Xylene was also obtained from the pathology laboratory of HopeXchange Medical Center whilst the albino rats were purchased from the Animal House at the Pharmacy Department of KNUST. The rats were sacrificed and the soft tissues (prostate) were harvested.

Treatment of Tissue Specimen

The organs were surgically removed and fixed immediately in the laboratory. A total of 10 prostate organs were obtained and cut into 4 equal parts before grouping them into Groups A, B, C, and D. Gross tissue examination like rigidity, translucency, change after impregnation, and ease of sectioning of tissue blocks were evaluated by two independent histopathologists based on the scoring criteria given in the literature.40–42 All the specimens were taken through all the needed procedures.

Fixation for All Samples

Each of the 10 prostate organs removed during surgical procedure were fixed in 10% neutral-buffered formalin for 8hrs. Each specimen with an average volume of 0.819cm3 was cleared in 10ml of formalin at room temperature. Subsequently, tissues were cut into four equal parts and arranged in experimental groups namely Group A, Group B, Group C, and Group D.

Dehydration for Groups A, B, C and D

After fixation, the tissues in Group A were dehydrated in ascending grades ethanol in proportions of 70% for 45mins, 80% for 45mins, 90% for 45mins, 2×100% for 1hr each using the automated tissue processor. The samples in Groups B, C, and D were manually dehydrated.

Clearing of Tissue Specimen for Group A

The dehydrated tissues were cleared automatically using two changes of xylene for 1hr 30mins each. Rigidity of tissue specimen was assessed by palpating the tissue with two fingers after clearing. It was done to check if all solutions have been cleared from the tissue and has become hard enough to be cut into thin slice.

Impregnation of Tissue Specimen for Group A

The cleared tissue specimens were impregnated in molten paraffin wax (2× Paraffin wax for 45mins each and 2× Paraffin wax for 1hr each).

Embedding of Tissue Specimen for Group A

Embedding was carried out in molten paraffin wax using plastic disposable cassettes and allowed to solidify before microtomy. Tissue blocks were sectioned at a thickness of 5µm with a rotary microtome and sections floated in warm water bath and picked on fresh microscopic glass slides.

Before staining, the slides were dewaxed in xylene (4×3min in xylene), then passed through descending grades of ethanol (2×100% for 3min each, 95% for 3min, 80% for 3min, and 70% for 3min) and was rinsed in deionized water for 3min. Hydrated sections were stained in hematoxylin for 3min and washed under tap water for 5min. The slides were dipped ones in acid alcohol, washed under tap water and blotted. The sections were dehydrated in 70% ethanol for 3min, then counterstain in 1% eosin stain for 1min and dehydrated in 90% ethanol and 4×100% ethanol for 5min each. Clearing of the slides using four changes of xylene for 2min each, air dried and mounted with DPX mountant.

Clearing of Tissue Specimen for Groups B, C, and D

Dehydrated tissues were cleared in two changes of coconut oil for 1hr 30mins each, 3hrs each and 4hrs each, respectively.

Impregnation, Embedding, Sectioning, and Staining of Groups B, C and D Samples

Impregnation, embedding, sectioning and staining followed the same procedure as the samples in Group A except for dewaxing with heated (60C) coconut oil in an incubator for 5 min instead of xylene to fulfill Bernoulli’s principle. According to Bernoulli’s principle of fluid dynamics, the viscosity of fluid is indirectly proportional to temperature, which means, as the temperature of the fluid increases, the viscosity of the fluid decreases and as a result penetration of fluid increases. 43 In this study, coconut oil was more viscous when compared with that of xylene. Hence, to decrease the viscosity of the oil for increased penetration into tissues to clear them at a faster rate, clearing of tissues after dehydration in both processing and staining procedures was carried out after heating the coconut oil at a temperature of 60C. Rigidity of tissue specimen was assessed by two independent histopathologists by palpating the tissue with two fingers after clearing. It was done to check if all solutions have been cleared from the tissue and has become hard enough to be cut into thin slice. Clearing of the slides also involved the use of four changes of preheated coconut oil at 60C for 2min each before air drying and mounting in DPX.

Microscopy and Scoring of Hematoxylin and Eosin-Stained Slides of Tissue Specimens A-D

All the slides were viewed by two independent histopathologists for evaluation and scoring based on nuclear staining, cytoplasmic staining, and clarity of staining. These histopathologists did not know the difference in clearing agents used since numbers were used to label the slides to enhance blinding and unbiased remarks. The method for scoring the stained slides was adopted from previous works40–42 for the rigidity, translucency, change of impregnation, and ease in sectioning and staining. It can be interpreted as

Inferior to xylene—————0

Equivalent to xylene———–1

Better than xylene————–2

Results

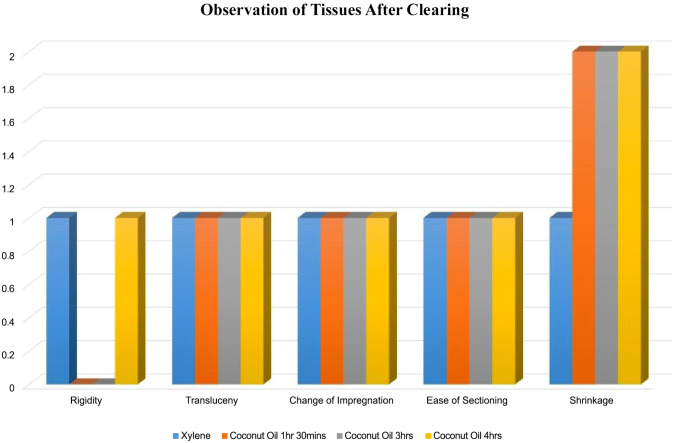

Rigidity of Specimen

The rigidity of the specimen was compared among the groups having Group A as the control. Groups B, C, and D were evaluated to determine whether they are inferior, same or superior to the control Specimen A. Among six specimens, which were cleared in coconut oil for 1hr 30mins, 3hrs, and 4hrs representing Groups B, C, and D respectively, Group B and C specimens showed inferior characteristics to xylene, but Group D specimens showed same characteristics to xylene (p = 0.856) (Tables 1 to 3 and Fig. 6).

Table 1.

Comparison of Gross Features of Specimen Cleared in Coconut Oil for 3hrs (Group C) to Specimen Cleared in Xylene for 3hrs (Group A).

| Xylene | Coconut oil | Mean score | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Observation | 0.736 | |||

| Rigidity | Rigid | Less rigid | 0.0±0 | |

| Translucency | Translucent | Translucent | 1.0±0 | |

| Change after impregnation | No significant change | No significant change | 1.0±0 | |

| Ease in section cutting | Easy | Easy | 1.2±0 | |

| Shrinkage | Shrinkage | Shrinkage | 2.0±0 |

Score 0: Inferior to xylene, score 1: equivalent to xylene, score 2: better than xylene, p value computed by Chi-square test.

Table 3.

Comparison of Gross Features of Specimen Cleared in Coconut Oil for 4hrs (Group D) to Specimen Cleared in Xylene for 3hrs (Group A).

| Xylene | Coconut oil | Mean score/SD | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Observation | 0.925 | |||

| Rigidity | Rigid | Rigid | 0.9±0 | |

| Translucency | Translucent | Translucent | 1.0±0 | |

| Change after impregnation | No significant change | No significant change | 1.0±0 | |

| Ease in section cutting | Easy | Easy | 1.4±0 | |

| Shrinkage | Shrinkage | Shrinkage | 2.0±0 |

Score 0: Inferior to xylene, score 1: equivalent to xylene, score 2: better than xylene, p value computed by Chi-square test.

Figure 6.

Shows observation of tissues after clearing.

Table 2.

Comparison of Gross Features of Specimens Cleared in Coconut Oil for 1hr 30mins (Group B) to Specimen Cleared in Xylene for 3hrs (Group A).

| Xylene | Coconut oil | Mean score/SD | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Observation | 0.856 | |||

| Rigidity | Rigid | Rigid | 0.0±0 | |

| Translucency | Translucent | Translucent | 0.95±0 | |

| Change after impregnation | No significant change | No significant change | 1.0±0 | |

| Ease in section cutting | Easy | Easy | 1.0±0 | |

| Shrinkage | Shrinkage | Shrinkage | 2.0±0 |

Score 0: Inferior to xylene, score 1: equivalent to xylene, score 2: better than xylene, p value computed by Chi-square test.

Translucency of Specimen

The translucency of the samples from groups B, C and D was compared with group A. All the samples showed same characteristics to xylene (p = 0.856) (Tables 1 to 3 and Fig. 6).

Change After Impregnation

The change after impregnation was compared between the groups with Group A as the control. All the samples cleared in coconut oil for 1hr 30mins, 3hrs, and 4hrs representing Groups B, C, and D respectively showed the same characteristics to Group A (p = 0.856). This can be seen in (Tables 1 to 3 and Fig. 6).

Ease in Section Cutting

The ease of sectioning of specimen was compared between the groups having group A as the control. The samples cleared in coconut oil for 1hr 30mins, 3hrs, and 4hrs representing Groups B, C, and D respectively showed same characteristics to the samples in Group A (p = 0.856). This can be seen in (Tables 1 to 3 and Fig. 6).

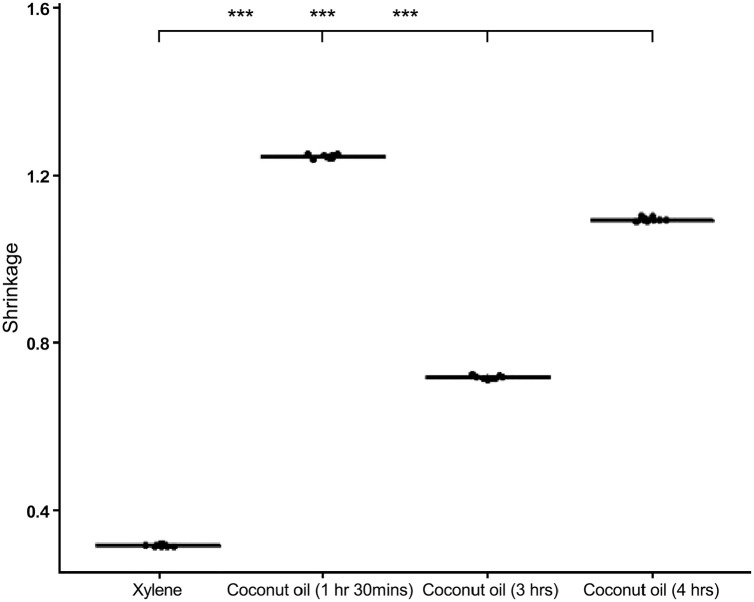

Shrinkage

The difference in size before and after clearing was taken for each of the tissue samples cleared in coconut oil at varying times and xylene. There was a significant reduction in the size of the prostate tissues cleared in coconut oil than in xylene with p value < 0.001 as shown in Fig. 5.

Figure 5.

A box plot showing shrinkage in coconut oil compared to xylene.

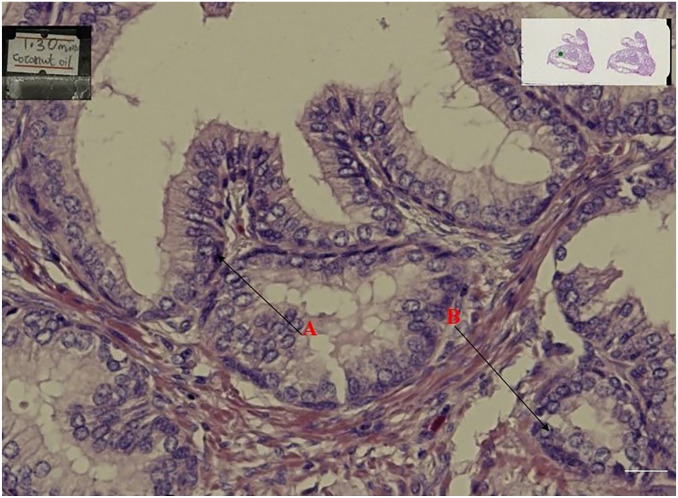

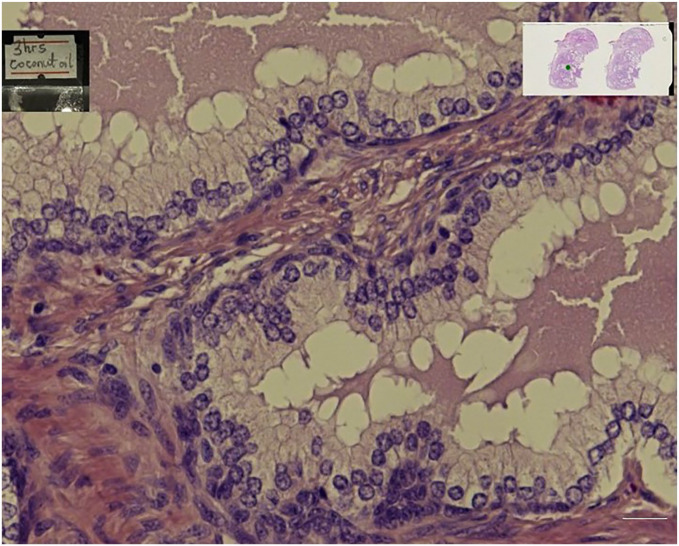

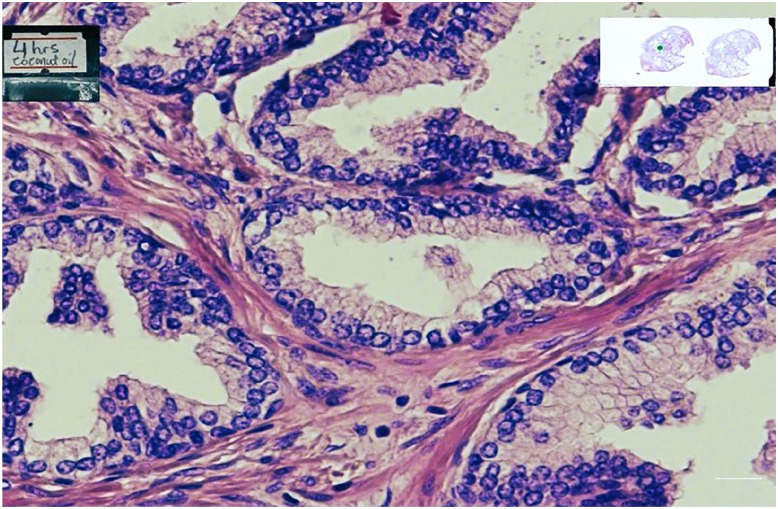

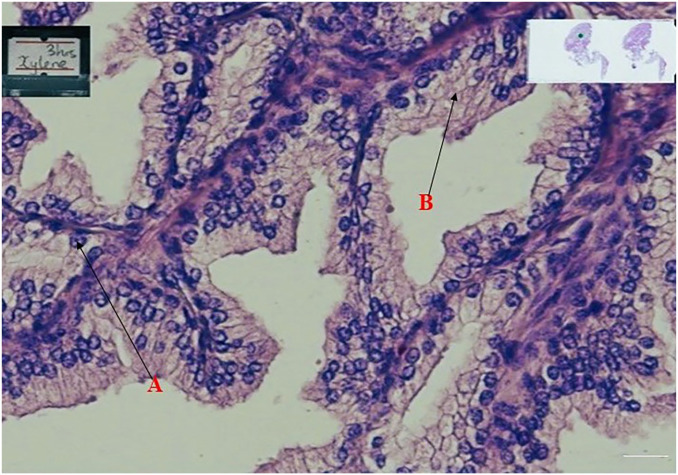

Nuclear and Cytoplasmic Staining

When all the stained slides were assessed for nuclear staining and cytoplasmic staining, the specimen cleared in coconut oil (Figs 1, 3, and 4) were as better as the control specimens which is the xylene (Fig. 2). Fig. 6 shows a graphical representation of both the nuclear and cytoplasmic staining scores for all the samples cleared in coconut oil and xylene.

Figure 1.

Shows prostate tissue cleared in coconut oil for 1hr 30min.

Figure 3.

Shows prostate tissue cleared with coconut oil for 3hrs and stained with Haematoxylin and Eosin.

Figure 4.

Shows a prostate tissue cleared in coconut oil for 4hr.

Figure 2.

Shows prostate tissue cleared in xylene for 3hrs and stained with Haematoxylin (A) and Eosin (B).

Overall Staining Intensity

All stained slides were assessed for clarity of staining. Observation showed that coconut oil-cleared specimens were as good as the xylene cleared specimen (p > 0.999) (Table 4, Fig. 4).

Table 4.

Comparison of Staining Quality of Specimen Cleared in Coconut Oil and Xylene.

| Xylene | Coconut oil | Score | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cellular architecture and staining | >0.999 | |||

| Nucleus | Good | Good | 1 | |

| Cytoplasm | Good | Good | 1 | |

| Quality | Good | Good | 1 |

Score 0: Inferior to xylene, Score 1: equivalent to xylene, Score 2: better than xylene, p value computed by Chi-square test.

Discussion

The results of this study showed that coconut oil treated specimen, after clearing, was apparently as translucent as xylene-treated specimen. Although less rigid in contrast to xylene, it did not adversely affect impregnation and sectioning cutting. To determine the effectiveness of coconut oil as a clearing agent, gross tissue examination of rigidity, translucency, change after impregnation, and ease in section cutting was observed. Varying the time of coconut oil did not have any effects on the tissue. It was observed that coconut oil was effective since it showed similar characteristics to xylene in terms of rigidity, translucency, change after impregnation, and ease in sectioning.

The samples cleared in coconut oil for 1hr 30mins and 3hrs were recorded to be less rigid compared with xylene specimen which was rigid but specimen cleared in coconut oil for 4hrs was recorded to be rigid and had a score equal to xylene specimen in terms of rigidity. Even though Groups B and C specimen were less rigid, the sectioning was not difficult since the minimum required rigidity was acquired. This also showed that time (minimum 4hrs) is an extremely important factor in clearing when using coconut oil and must always be considered.

Translucency of tissue specimen was assessed by observing the tissue section for reflected light. Tissue sections have to be rendered translucent to make microscopic observation possible. Translucency was observed in all the three-coconut oil cleared specimen and was similar to xylene cleared specimen. This also shows that time is not an important factor in translucency when using coconut oil for clearing.

Impregnation of tissue specimen is done to give the tissue specimen inner support so that sectioning can be made easily. Impregnation was done by infiltrating the tissue specimen with a molten paraffin wax at a temperature of 45C. After impregnation, we observed no changes among all the coconut oil cleared specimen and was recorded to be similar to xylene.

Sectioning of tissue specimen was made at a thickness of 5µm. An ease in sectioning was encountered with coconut oil-cleared specimen without any difficulties as recorded by Sermadi et al. 44 who en-countered difficulties in sectioning specimen cleared in coconut oil.

The drastic degree of shrinkage observed in the prostate tissues cleared in coconut oil contradicts the evidence provided by previous works.21,44 This could be due to the difference in the composition of the tissues used in the study as well as the difference in rat and human tissues. Even though the degree of shrinkage was significant in the coconut oil cleared tissue samples, the microscopy did not reveal changes in the morphology, intensity, and clarity in both the nucleus and cytoplasm.

Stainability is the ability of the cells in the tissue to pick up stains. Stainability was assessed among all the three-coconut oil cleared specimen and compared with the control specimen (xylene). Specimen cleared in coconut oil for 3hrs was recorded as most effective in terms of stainability and was better than the control specimen (xylene). Specimen cleared in coconut oil for 1hr 30mins and 3hrs was recorded to be similar to the control specimen (xylene).

Stainability of tissue specimen was assessed after coconut oil cleared specimen was stained with routine Hematoxylin and Eosin and compared with hematoxylin and eosin-stained xylene cleared specimen. We observed that the stain could penetrate into the coconut oil cleared specimen to give a better view which was similar to xylene. This was made possible due to the refractive index of coconut oil which is similar to xylene. It rendered the tissue translucent so that the cells of the tissues could pick up the stains. Varying the time of coconut oil did not have effects on the stainability of tissue specimen and all the three groups of coconut oil specimen gave better view. This result was in conformity with Sermadi et al. 44 who worked on comparing the efficacy of coconut oil and palm oil as a clearing agent. Staining intensity was assessed after observation of nuclear and cytoplasmic staining in coconut oil cleared specimen which was similar to xylene cleared specimen.

Conclusion

The result for this study infers that coconut oil is an efficient substitute for xylene, as it is environmentally friendly, less expensive, and causes less shrinkage to the tissue. It can be used as both de-alcoholization agent and dewaxing agent without losing the quality of the histological details. Coconut oil is able to render tissues translucent to enable microscopic observation. Coconut oil does not affect the cellular architecture. Nucleus and cytoplasm were able to pick up the H&E stain after processing with coconut oil and also gave a better staining intensity.

Limitations

This research was limited to only routinely used hematoxylin and eosin stain. This research was limited to only soft tissues and the sample size was also small.

Recommendations

Further research in this area is expected, where coconut oil–treated specimens can be subjected to various stains other than H&E and modern histological procedures such as immunohistochemistry, before it can be considered as a better and safer alternative to xylene. Awareness to reduce health hazards in the histopathology lab should be made to create a much safer working environment by the lab manager and assistants. Education programs concerning SOP, safety precautions, and emergency management should be encouraged.

Acknowledgments

Laboratory support was provided by the HopeXchange Medical Centre and their Research Unit.

Footnotes

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Author Contributions: OAB, DNS and MAA; Conceived and designed the experiment, wrote the paper: OAB, OOD, QP and AAM; Contributed reagents, materials and wrote the paper: OAB, AKM, OSA and ES; Provided technical support, analysed and interpret-ed data, wrote the paper.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was self funded and received no ex-ternal financial support.

ORCID iDs: Darko Nkansah Samuel  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0750-4311

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0750-4311

Osei Sarpong Albert  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1166-0533

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1166-0533

Ebenezer Senu  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2973-8952

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2973-8952

Contributor Information

Owusu Afriyie Bright, Department of Medical Laboratory Technology, Garden City University College, Kumasi, Ghana; Department of Medical Laboratory Science, University of Energy and Natural Resources, Sunyani, Ghana; Department of Molecular Medicine, School of Medicine and Dentistry, Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, Kumasi, Ghana.

Darko Nkansah Samuel, Department of Molecular Medicine, School of Medicine and Dentistry, Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, Kumasi, Ghana.

Musah Ayeley Adisa, Department of Biological Sciences, University of Energy and Natural Resources, Sunyani, Ghana.

Owusu Ohui Dorcas, Department of Biological Sciences, Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, Kumasi, Ghana.

Quartey Perez, Department of Medical Laboratory Technology, Garden City University College, Kumasi, Ghana.

Antwi Ama Melody, Department of Medical Laboratory Technology, Garden City University College, Kumasi, Ghana; Department of Molecular Medicine, School of Medicine and Dentistry, Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, Kumasi, Ghana.

Addai Kusi Michael, Department of Medical Laboratory Technology, Garden City University College, Kumasi, Ghana; Department of Medical Laboratory, Pathology Unit, HopeXchange Medical Centre, Kumasi, Ghana.

Osei Sarpong Albert, Department of Medical Laboratory Technology, Garden City University College, Kumasi, Ghana.

Ebenezer Senu, Department of Molecular Medicine, School of Medicine and Dentistry, Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, Kumasi, Ghana.

Literature Cited

- 1. Metgud R, Astekar MS, Soni A, Naik S, Vanishree M. Conventional xylene and xylene-free methods for routine histopathological preparation of tissue sections. Biotech Histochem. 2013;88(5):235–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Aziz N, Zhao Q, Bry L, Driscoll DK, Funke B, Gibson JS, Grody WW, Hegde MR, Hoeltge GA, Leonard DG, Merker JD, Nagarajan R, Palicki LA, Robetorye RS, Schrijver I, Weck KE, Voelkerding KV. College of American pathologists’ laboratory standards for next-generation sequencing clinical tests. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2015;139(4):481–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Rai R, Bhardwaj A, Verma S. Tissue fixatives: a review. Int J Pharm Drug Anal. 2016;4(4):183–7. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hryn VH, Kostylenko YP, Bilash VP, Tarasenko YA. Features of angioarchitecture of the albino rats stomach and small intestine. Wiad Lek. 2019;72(3):311–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Dineshshankar J, Saranya M, Tamilthangam P, Swathiraman J, Shanmathee K, Preethi R. Kerosene as an alternative to xylene in histopathological tissue processing and staining: an experimental study. J Pharm Bioallied Sci. 2019;11(Suppl 2):S376–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Arko-Boham B, Ahenkorah J, Hottor BA, Dennis E, Addai FK. Improved method of producing satisfactory sections of whole eyeball by routine histology. Microsc Res Tech. 2014;77(2):138–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Eltoum I, Fredenburgh J, Myers RB, Grizzle WE. Introduction to the theory and practice of fixation of tissues. J Histotechnol. 2001;24:173–90. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Shah AA, Kulkarni D, Ingale Y, Koshy AV, Bhagalia S, Bomble N. Kerosene: contributing agent to xylene as a clearing agent in tissue processing. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol. 2017;21(3):367–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Stillerman KP, Mattison DR, Giudice LC, Woodruff TJ, Caserta D, Pegoraro S, Mallozzi M, Di Benedetto L, Colicino E, Lionetto L, Simmaco M, Beulen YH, Super S, de Vries JHM, Koelen MA, Feskens EJM, Wagemakers A. Formalin tissue fixation biases myelin-sensitive MRI. Environ Int. 2020;10(1):1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lunetta M, Grivois M, Hansen C, Seery P, Felty C, Rizzo E, Jackson C. Comparative study of two reprocessing methods for formalin fixed paraffin embedded tissue. J Histotechnol. 2022;45(3):120–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bancroft J, Gamble M. Theory and practice of histological techniques. Churchill Livingstone; 2008. p. 126–7. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Frasquilho SG, Sanchez I, Yoo C, Antunes L, Bellora C, Mathieson W. Do tissues fixed in a non-crosslinking fixative require a dedicated formalin-free processor? J Histochem Cytochem. 2021;69(6):389–405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sánchez-Porras D, Bermejo-Casares F, Carmona R, Weiss T, Campos F, Carriel V. Tissue fixation and processing for the histological identification of lipids. Methods Mol Biol. 2023;2566:175–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bernal V, Aburto P, Pérez B, Gómez M, Gutierrez JC. A technical note of improvement of the elnady technique for tissue preservation in veterinary anatomy. Animals. 2022;12(9):1111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bemenderfer TB, Harris JS, Condon KW, Li J, Kacena M. Processing and sectioning undecalcified murine bone specimens. Methods Mol Biol. 2021;2230:231–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kiernan JA. Histological and histochemical methods: theory and practice. Scion Publishing; 2008. p. 210. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Zhanmu O, Yang X, Gong H, Li X. Paraffin-embedding for large volume bio-tissue. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):12639. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-68876-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Pandey P, Dixit A, Tanwar A, Sharma A, Mittal S. A comparative study to evaluate liquid dish washing soap as an alternative to xylene and alcohol in deparaffinization and hematoxylin and eosin staining. J Lab Physicians. 2014;6(2):84–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Song J, Zeng N, Guo W, Guo J, Ma H. Stokes polarization imaging applied for monitoring dynamic tissue optical clearing. Biomed Opt Express. 2021;12(8):4821–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Van der Lem T, de Bakker M, Keuck G, Richardson MK, Wilhelm His Sr. and the development of paraffin embedding. Pathologe. 2021;42(Suppl 1):55–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bordoloi B, Jaiswal R, Tandon A, Jayaswal A, Srivastava A, Gogoi N. Evaluation and comparison of the efficacy of coconut oil as a clearing agent with xylene. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol. 2022;26(1):72–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bancroft J. Theory and practice of histological techniques. Churchill Livingstone; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Neckel PH, Mattheus U, Hirt B, Just L, Mack AF. Large-scale tissue clearing (PACT): technical evaluation and new perspectives in immunofluorescence, histology, and ultrastructure. Sci Rep. 2016;6:34331. doi: 10.1038/srep34331 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Fabri J, Graeser U, Simo T. eds. Xylenes. In: Ullmann’s encyclopedia of industrial chemistry. Wiley-VCH; 2002. p. 28–433. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kumar A, Daw P, Milstein D. Homogeneous catalysis for sustainable energy: hydrogen and methanol economies, fuels from biomass, and related topics. Chem Rev. 2022;122(1):385–441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ortiz SC, Zuidema E, Rigutto M, Dubbeldam D, Vlugt TJH. Competitive adsorption of xylenes at chemical equilibrium in zeolites. J Phys Chem C. 2021;125(7):4155–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lestido-Cardama A, Vázquez-Loureiro P, Sendón R, Bustos J, Santillana MI, Losada PP, de Quirós ARB. Characterization of polyester coatings intended for food contact by different analytical techniques and migration testing by LC-MSn. Polymers. 2022;14(3):487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Aransiola EF, Daramola MO, Ojumu TV. Xylenes: production technologies and uses. Nova Science Publishers; 2013. p. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Iskandar M, Mohammadi JM, Sephavad A, Farhadi A, Obaid RF, Taherian M, Alali N, Chowdhury S, Farhadi M. Associated health risk assessment due to exposure to BTEX compounds in fuel station workers [published online ahead of print March 14, 2023]. Rev Environ Health. doi: 10.1515/reveh-2023-0012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Niland EE, McGuire A, Cox MH, Sandusky GE. High quality DNA obtained with an automated DNA extraction method with 70+ year old formalin-fixed celloidin-embedded (FFCE) blocks from the Indiana medical history museum. Am J Transl Res. 2012;4(2):198–205. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Guarte R, Muhlbauer W, Kellert M. Drying characteristics of copra and quality of copra and coconut oil. Postharvest Biol Technol. 1996;9:361–72. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Chatterjee P, Fernando M, Fernando B, Dias CB, Shah T, Silva R, Williams S, Pedrini S, Hillebrandt H, Goozee K, Barin E, Sohrabi HR, Garg M, Cunnane S, Martins RN. Potential of coconut oil and medium chain triglycerides in the prevention and treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. Mech Ageing Dev. 2020;186:111209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lawson H. Standard of fats and oils. AVI Publishing Company; 1985. p. 24–37. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Deen A, Visvanathan R, Wickramarachchi D, Marikkar N, Nammi S, Jayawardana BC, Liyanage R. Chemical composition and health benefits of coconut oil: an overview. J Sci Food Agric. 2021;101(6):2182–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Rabail R, Shabbir MA, Sahar A, Miecznikowski A, Kieliszek M, Aadil RM. An intricate review on nutritional and analytical profiling of coconut, flaxseed, olive, and sunflower oil blends. Molecules. 2021;26(23):7187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Osawa C, Goncalves L, Ragazzi S. Correlation between free fatty acids of vegetable oils evaluated by rapid tests and by the official method. J Food Compost Anal. 2007;20:523–8. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Swamy SR, Nandan SR, Kulkarni PG, Rao TM, Palakurthy P. Bio-friendly alternatives for xylene—carrot oil, olive oil, pine oil, rose oil. J Clin Diagn Res. 2015;9(11):ZC16–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Haghbin N, Oveisi B, Banitaba AP. Automated variable power cold microwave tissue processing: a novel universal tissue processing protocol without using formaldehyde and xylene. Acta Histochem. 2022;124(4):151880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Udonkang M, Eluwa M, Ekanem A, Sharma T, Asuquo O, Akpantah A. Bleached palm oil as substitute for xylene in histology. J Pharm Clin Res. 2014;8:8–17. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Arko-Boham B, Owusu BA, Aryee NA, Blay RM, Owusu EDA, Tagoe EA, Adams AR, Gyasi RK, Adu-Aryee NA, Mahmood S. Prospecting for breast cancer blood biomarkers: death-associated protein kinase 1 (DAPK1) as a potential candidate. Dis Markers. 2020;2020:6848703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Le Maitre CL, Dahia CL, Giers M, Illien-Junger S, Cicione C, Samartzis D, Vadala G, Fields A, Lotz J. Development of a standardized histopathology scoring system for human intervertebral disc degeneration: an Orthopaedic Research Society Spine Section Initiative. JOR Spine. 2021;4(2):e1167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Gibson-Corley KN, Olivier AK, Meyerholz DK. Principles for histopathologic scoring. Vet Pathol. 2008;23(1):1–7. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3795863/pdf/nihms473596.pdf [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Prematha B, Patil S, Rao RS, Indu M. Mineral oil—biofriendly substit xylene deparafinization. J Contemp Dent Pract. 2013;14:281–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Sermadi W, Prabhu S, Acharya S, Javali S. Comparing the efficacy of coconut oil and xylene as a clearing agent in the histopathology laboratory. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol. 2014;18(Suppl 1):S49–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]