Abstract

Objective

Use CFIR guidance to create comprehensive, evidence-based, feasible, and acceptable gender-affirming care PROM implementation strategies.

Design, setting, participants

A 3-Phase participatory process was followed to design feasible and acceptable strategies for integrating PROMs in gender-affirming care. In Phase 1, barriers and enablers to PROM implementation for gender-affirming care were identified from a previous systematic review and our prior qualitative study. We used the CFIR-ERIC tool to match previously identified barriers and enablers with expert-endorsed implementation strategies. In Phase 2, implementation strategy outputs from CFIR-ERIC were organised according to cumulative percentage value. In Phase 3, gender-affirming care PROM implementation strategies underwent iterative refinement based on rounds of stakeholder feedback with seven patient and public partners and a gender-affirming healthcare professional.

Results

The systematic review and qualitative study identified barriers and enablers to PROM implementation spanning all five CFIR domains, and 30 CFIR constructs. The top healthcare professional-relevant strategies to PROM implementation from the CFIR-ERIC output include: identifying and preparing implementation champions, collecting feedback on PROM implementation, and capturing and sharing local knowledge between clinics on implementation. Top patient-relevant strategies include: having educational material on PROMs, ensuring adaptability of PROMs, and collaborating with key local organisations who may be able to support patients.

Conclusions

This study developed evidence-based, feasible, and acceptable strategies for integrating PROMs in gender-affirming care, representing evidence from a systematic review of 286 international articles, a qualitative study of 24 gender-affirming care patients and healthcare professionals, and iteration from 7 patient and public partners and a gender-affirming healthcare professional. The finalised strategies include patient- and healthcare professional-relevant strategies for implementing PROMs in gender-affirming care. Clinicians and researchers can select and tailor implementation strategies best applying to their gender-affirming care setting.

Introduction

Gender-affirming care includes a range of psychosocial, hormonal, and surgical care offered to affirm and support a person’s experience of their gender when it is different from sex assigned at birth. Gender-affirming care is life-saving treatment, which can reduce a person’s gender dysphoria and decrease suicidality, depression, and anxiety [1]. In order to plan for and provide effective gender-affirming care that aligns with a patient’s goals, values, and priorities, the needs and experiences of the individual must be explored holistically and in a patient-centred manner [1]. Patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) may help with this [1, 2].

PROMs are self-report questionnaires that measure how patients feel and function [3]. A few examples of diverse PROMs used across various clinical areas include: the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) used to measure degree of depression [4]; the Oxford Hip Score to measure outcomes following total hip replacement [5]; and the World Health Organization Quality of Life instrument (WHOQOL) which measures quality of life [6]. The benefits of PROMs are well researched and include improvements in communication between patients and clinicians [7], satisfaction with care [8], health outcomes [9], the detection of issues that might otherwise go unaddressed [10], and mortality [11]. For gender-affirming care, PROMs could facilitate better patient-provider communication and shared decision-making, enable the challenging of bias and/or discriminatory practice, and assist evaluating care delivery to inform service improvement [12]. A few examples of key PROMs for gender-affirming care include the Gender Congruence and Life Satisfaction Scale (GCLS) [13] and the Utrecht Gender Dysphoria Scale (UGDS) [14]. These PROMs can be integrated in gender-affirming care as part of initial baseline assessments, to monitor patients’ progress during follow-up visits, to support shared decision-making during appointments, and to augment discussions between clinicians, and patients, in general.

Despite these benefits, PROM uptake is limited, with some clinical areas reporting that 1% of clinicians use PROMs [15–18]. Many PROM implementation initiatives fail due to a lack of evidence-based implementation strategies [19–21]. Indeed, several international bodies have called for evidence-based patient-reported outcome measure (PROM) implementation to improve gender-affirming care globally [1, 2, 22–24].

Implementation science offers established methods for categorising barriers and enablers to implementation of innovations, as well as identifying strategies for addressing the barriers and leveraging the enablers [25]. The Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) is an implementation science “meta-framework” that categorises barriers and enablers to implementation across five domains: outer setting, inner setting, innovation, individuals, and implementation process (Table 1) [26]. Domains are further subdivided into more specific constructs [26]. A previous systematic review [12] and qualitative study [27] conducted by our team categorized patient- and healthcare professional-reported barriers and enablers to implementing PROMs in gender-affirming care, in keeping with CFIR domains. The next step forward is to develop evidence-based implementation strategies that can address these barriers and enablers.

Table 1. CFIR domains and definitions from Damschroder et al. 2022 [26].

| CFIR Domain | Definition |

|---|---|

| Innovation | The “thing” that is being implemented, e.g., PROMs |

| Inner Setting | Where the innovation is being implemented, e.g., gender clinics |

| Outer Setting | The context in which the Inner Setting exists, e.g., healthcare system, country |

| Individuals | Roles and characteristics of people involved with implementation, e.g., implementation team members, innovation deliverers (i.e., healthcare professionals), innovation recipients (i.e., patients) |

| Implementation Process | Sequential steps and strategies to implement the innovation |

The CFIR- Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change (ERIC) tool can be used to link identified barriers and enablers to create an implementation strategy [28]. The CFIR-ERIC tool is a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet where barriers and enablers to implementation, categorised according to CFIR constructs, can be inputted. The CFIR constructs are inputted as rows, and for each of the ERIC strategies, listed as columns, the Excel spreadsheet provides an output representing the cumulative percentage of implementation experts agreeing that this ERIC strategy would be effective at addressing the barrier related to the constructs entered. The ERIC strategies were developed through a modified Delphi process, compiling 73 implementation strategies from 169 implementation experts, and has been widely applied to implementation strategy design [28, 29]. The ERIC strategies were developed first, and then later were linked to CFIR constructs via the CFIR-ERIC tool. The CFIR-ERIC tool outputs provide key evidence-based strategies which can be linked to address specific implementation barriers and enablers [30, 31]. As the outputs from CFIR-ERIC are generic in nature, it is important to tailor the strategies to a specific context for acceptability and feasibility using input from key stakeholders.

The aim of this study is to use CFIR guidance to create comprehensive and evidence-based PROM implementation strategies for gender-affirming care, which may also have potential generalizability to other clinical areas.

Materials and methods

Designing feasible and acceptable strategies for integrating PROMs in gender-affirming care

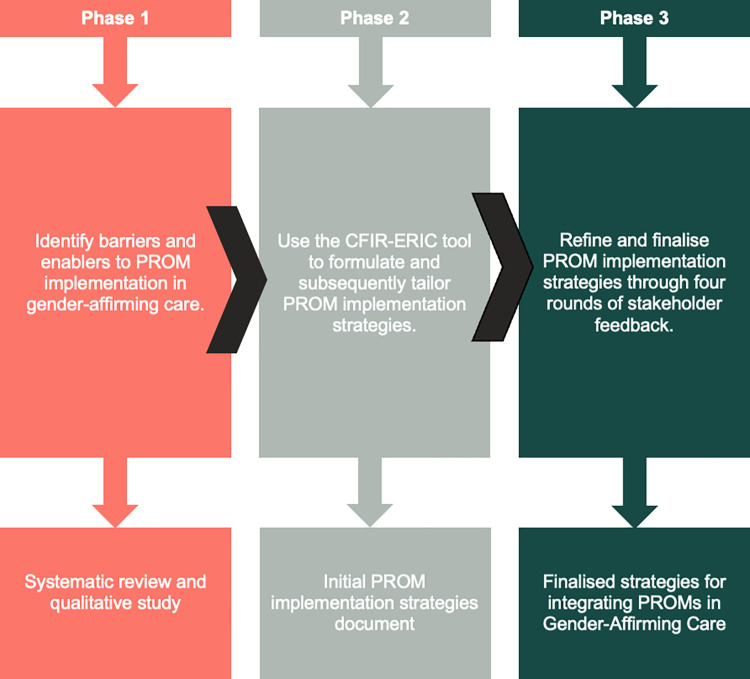

We followed a 3-Phase participatory process to designing feasible and acceptable strategies for integrating PROMs in Gender-Affirming Care using CFIR guidance (Fig 1).

Fig 1. Diagram of 3-phased participatory research process to create feasible and acceptable strategies for integrating PROMs in gender-affirming care.

Phase 1

Barriers and enablers to PROM implementation for gender-affirming care were identified from our previous systematic review including 286 articles worldwide with no restrictions on date or language of publication, and our prior qualitative study that sought to understand the experiences of 14 gender-diverse patients seeking gender affirming care, and 10 interdisciplinary healthcare professionals [12, 27]. Results from the systematic review and qualitative study were organised according to CFIR construct and synthesised and prepared to be inputted into the CFIR-ERIC tool by two researchers (RK, LJ) (S1 Appendix).

Phase 2

The data from Phase 1 were categorised with the CFIR-ERIC tool, which was used to match barriers and enablers to potential components of the implementation strategy. This was done with Excel (version 16.67) by two researchers (RK, LJ). Specifically, two researchers (RK, LJ) worked in collaboration to enter data into the CFIR-ERIC tool, which matched barriers and enablers to implementation strategies (CFIR-ERIC output is available in S2 Appendix). Implementation strategy components were organised according to cumulative percentage value from the CFIR-ERIC tool, and refined for the context of PROM implementation in gender-affirming care by two researchers (RK, LJ) (S3 Appendix). Specifically, terminology used in gender-affirming care and with PROMs was used to tailor the general statements outputted from CFIR-ERIC to the context of PROM implementation in gender-affirming care by two researchers (RK, LJ).

Phase 3

The gender-affirming care PROM implementation strategies underwent iterative refinement based on rounds of stakeholder feedback. The gender-affirming care PROM implementation strategy developed through the CFIR-ERIC tool in Phase 2 was reviewed in sequence by seven patient and public partners representing members of the transgender and nonbinary community, and a gender-affirming care healthcare professional with expertise in PROM use for clinical practice (AL). These stakeholders were sent the gender-affirming care PROM implementation strategies and asked to provide written feedback on the acceptability and feasibility of the implementation strategies. S4 Appendix includes the feedback form used by stakeholders. The feedback from stakeholders was used to refine the implementation strategies. The implementation strategies underwent four rounds of iteration (two rounds with patient and public partners, and two rounds with a gender-affirming care healthcare professional) before all stakeholders were in consensus on the final strategies. The rounds of iteration were asynchronous: after each round of feedback, the implementation strategies were revised to respond to feedback raised. Afterwards, the revised implementation strategies were sent for another round of feedback from stakeholders. Patients and healthcare professionals were able to comment on all strategies. Consensus was reached when all key stakeholders agreed on the final implementation strategies and did not have any additional feedback to provide. Disagreements during the rounds of feedback were handled through discussion as a team. The finalised feasible and acceptable strategies for integrating PROMs in gender-affirming care represent evidence from a systematic review of 286 international articles, a qualitative study of 24 gender-affirming care patients and healthcare professionals, and input from 7 patient and public partners and a gender-affirming healthcare professional.

Patient and public involvement

We conducted this research in partnership with seven patient and public partners, representing members of the transgender and nonbinary community. Patient and public partners were recruited through community support groups and national transgender charity organisations in the UK. Patient and public partners confirmed relevance of the research aim to create feasible and acceptable strategies for integrating the use of PROMs in gender-affirming care, and were involved in research to ensure applicability and feasibility of the implementation strategies.

Ethics

This study was reviewed by the Clinical Trials and Research Governance Department, University of Oxford, classified as service improvement and exempt from university sponsorship or ethics committee review. This categorisation was independently ratified by the Cumbria, Northumberland, Tyne and Wear NHS Foundation Trust where the study was independently reviewed and registered: SER-22-027. Service users who had provided written consent to take part in service improvement projects with Cumbria, Northumberland, Tyne and Wear NHS Foundation Trust were contacted and invited to take part in this study. Data collection began 1 May 2023 and ended 1 August 2023.

Reporting

Reporting follows the Standards for Reporting Implementation Studies (StaRI) guideline [32].

Results

Phase 1

The systematic review and qualitative study conducted previously by our team [12, 17] identified barriers and enablers to PROM implementation spanning all five CFIR domains, and 30 CFIR constructs. The systematic review and qualitative study had overlap in identifying barriers and enablers. However, the qualitative study offered additional information and explanation on the barriers and enablers to PROM implementation from the patient perspective, which was lacking in the systematic review. In summary, the key enablers identified from the systematic review and qualitative study were: adapting PROMs to be completed online and in-person, ensuring PROMs are not overly complex (too lengthy, difficult to score), ensuring PROMs are accessible to patients (i.e., those with sight issues, neurodivergence, intellectual disabilities), having a process in place to handle critical PROM responses, providing patients and healthcare providers information on what PROMs are and why they are important, and identifying implementation team members at the clinic who can facilitate implementation. S1 Appendix provides the complete list of barriers and enablers to PROM implementation for gender-affirming care identified from our previous systematic review and qualitative study.

Phase 2

The implementation strategies outputted by the CFIR-ERIC organized by cumulative percent are available in S2 Appendix. S3 Appendix displays the implementation strategies tailored for the context of gender-affirming care. The top healthcare professional-relevant enablers include: identify and preparing implementation champions, collect feedback on PROM implementation, and capture and share local knowledge between clinics on PROM implementation. The top patient-relevant enablers include: having educational material on PROMs, ensuring adaptability of PROMs, and collaborating with key local organisations who may be able to support patients to complete PROMs.

Phase 3

The finalised strategies for integrating PROMs in gender-affirming care are available in below (Tables 2 and 3). These tables detail patient- and healthcare professional-relevant strategies for implementing PROMs in gender-affirming care, organised into two tables (one table outlines patient-relevant strategies, and the other outlines healthcare professional-relevant strategies). Each row for both tables details a PROM implementation strategy which was created using evidence from a systematic review, qualitative study, and iterative refinement with patients and gender-affirming healthcare professionals.

Table 2. Patient-Relevant strategies for integrating PROMs in gender-affirming care.

| Patient-Relevant Strategies |

|---|

| Have educational material (mixture of videos, animations, written information) accessible which explains: what PROMs are, why they are being implemented, how they may benefit patient care, how they work, how data will be handled, and that care access will not be jeopardised with PROM completion. Care should be taken to ensure material is not too onerous. Coproduce educational material with service users to help with accessibility and increase engagement. |

| Ensure the PROM selected for implementation can adapt to patient needs (i.e., large-print, high contrast versions, different languages). |

| Have contact information provided of organisations or key individuals who may be able to support patients to complete PROMs (i.e., Citizens Advice, Support Worker, Assistant Psychologist). |

| Confirm when patients would prefer to complete PROMs (i.e., before a clinic appointment, after a clinic appointment, in between appointments), and where they would prefer to complete PROMs (i.e., at home, in clinic) prior to having a PROM sent to them. Also confirm how patients would like to receive communication about completing PROMs (such as reminders) (i.e., through email, text message, post). |

| Ask patients for feedback on a regular basis (e.g., annually) for how PROM implementation is going and suggestions for improvement. Seek permission from patients prior to asking for feedback on PROM implementation. Where possible, gather input from patients at service evaluations in conjunction with PROM implementation feedback. Ensure patient feedback is from diverse populations. |

| Confirm who patients would like PROM data to be shared with. Allow patients to choose levels of data usage and sharing as part of the consent process (i.e., I do not consent for you to use my data for research use, but you can use it for service level feedback and for my clinician to see if I am in distress). |

| Have a dedicated and private space to complete the PROM in clinic as an option. |

| Have multi-factor authentication set up for electronic PROMs so that patients can securely and remotely access their PROM and so that it cannot be accessed by unintended recipients. |

| Conduct an information session specifically about PROM completion and data use so patients can speak/air their views with clinicians/assistants/peer support about any questions or misgivings. |

| Implement a parallel system for monitoring waiting list patients and outcomes resulting from waiting lists where possible. |

| Have peer support staff available to contact if PROM completion is difficult. Also consider whether and how patients can access a peer support worker who is similar to the patient (i.e., age, neurodivergent, ethnicity). This may mean some of the support is provided remotely or more ad- hoc and the acceptability of this should be ascertained by and led by patients. If the PROM distress falls beyond the scope of peer support services, work in collaboration with third sector organisations like LGBT switchboard or crisis mental health services. |

Table 3. Healthcare professional-relevant strategies for integrating PROMs in gender-affirming care.

| Healthcare Professional-Relevant Strategies |

|---|

| Identify and prepare implementation champions who can help to oversee and be a point of support for PROM implementation in gender clinics. This may include Identifying and involving staff members (i.e., administrative staff, assistant psychologists) who can help to oversee PROM implementation. |

| Collect feedback on PROM implementation healthcare professionals. Have feedback collection be part of an overall feedback system. |

| Develop and provide educational material to healthcare professionals on what PROMs are, why they are being implemented, how they may benefit service provision, how scoring works, and how data will be handled. Use a variety of formats such as videos, animations, written materials, and information sessions. Co-produce educational material with healthcare professionals to increase acceptability and engagement. Address staff responsibility for both healthcare improvement and integrity with data processing and collection. Aim to have material communicated in a ‘common language’ and part of a therapeutic strategy. |

| Capture and share local knowledge between clinics on how PROM implementation is going. |

| Assess/confirm patient accessibility needs to adapt PROMs as needed (i.e., large-print, high contrast versions, providing overlays, different languages). |

| Inform higher-level leaders (i.e., senior managers of the trust) of the PROM implementation strategy for trust-level buy in. |

| Involve local organisations as points of support to aid PROM implementation (e.g., Citizens Advice as a point of support to patients who may need help filling in a form, ethnically diverse local organisations). Survey local organisations to see if they would be willing to be involved and if they have the knowledge required to support a gender-affirming care PROM implementation effort. |

| Involve local patient advisory groups as points of contact to provide support on PROM implementation. This could include tailoring PROM implementation strategies to your clinic in partnership with service users. |

| Organize staff meetings aimed at identifying a PROM to implement which is not burdensome (i.e., not too lengthy or complex to score, has a computerised adaptive test option) and formalising the PROM implementation plan. Also, organise a meeting with service users to identify measures which would be acceptable to them. |

| Develop a formal implementation blueprint for the clinic on PROM implementation. |

| Provide ongoing engagement with patients to facilitate dialogue about how PROM responses are used to improve care. |

| Develop academic partnerships to help facilitate PROM implementation and interpretation when using PROMs for research. |

| Have PROM responses linked to the electronic medical record so they are accessible online. Ensure patient control over data access and where patients consent. |

| Develop a process to handle critical PROM responses and feedback. Have details of this process available for patients. |

Discussion

This study has developed feasible and acceptable strategies for integrating the use of PROMs in gender-affirming care (Tables 2 and 3) which can be used by clinicians interested in implementing PROMs for their gender-affirming care setting globally. Global clinical guidelines and international studies suggest that PROMs are essential for measuring patient outcomes of gender-affirming care [1, 12]. In the UK in particular, there is an urgent need for improving patient outcomes and relationships/trust with clinicians. We followed organised methods and specific models and processes for developing the PROM implementation strategies as described by CFIR. The strategies developed from this study can be distributed to and used by clinicians and researchers to select and tailor implementation strategies best applying to their setting. Increased clinician training to raise awareness of these strategies may also help to increase skill development to maximize use and uptake of strategies. The strategies outlined can be used as a checklist to ensure a gender-affirming care clinic is maximising potential for PROM implementation. The strategies can also be used to guide a staff meeting on implementing PROMs for a specific gender-affirming care setting.

Past research on PROM implementation has focused on other clinical areas, such as an integrated pain network [33], outpatient medical oncology [34], general outpatient clinics [35], and primary care [36]. In past research, CFIR was successfully used to plan and assess PROM implementation and linking barriers and enablers to identified implementation strategies [37]. The constructs of acceptability and feasibility were evaluated by key stakeholders when developing past PROM implementation strategies in other clinical areas [38, 39]. Recommendations have also been made in a review of PROM implementation for PROM implementation strategies to be co-developed with clinicians and patients [37]. Our study provides the first set of feasible and acceptable implementation strategies for PROM implementation for the clinical area of gender-affirming care. The PROM implementation strategies developed from our study follows recommendations from past research and uses evidence-based and implementation science theory-, model- and framework-informed methods [26, 40–42].

The implementation strategies developed from this study has implications for policy, clinical practice, and research globally. Commissioners and policy-makers can use the strategies to inform PROM implementation policy for gender-affirming care. In clinical practice, our strategies can be used to help ensure gender-affirming care aligns with patient needs that leads to urgently needed improvements in care. Some of our findings may also be of interest to researchers aiming to minimise missing data for PROMs and improve PROM response rate for studies [43].

Strengths of this study include developing a theory-, model-, and framework-informed approach to developing implementation strategies to improve PROM uptake, in line with evidence-based recommendations for implementation studies in this area [37]. Our study followed established approaches in implementation science, along with established strategy development and reporting guidelines [28, 32]. The implementation strategies from this study considered diverse and international perspectives, informed by a systematic review representing 286 studies and 85, 395 patients worldwide, and an in-depth qualitative study representing 14 patients and 10 interdisciplinary healthcare providers. Further, each phase of this research was conducted in partnership with seven patient and public partners representing the gender-affirming care community.

Limitations of this study is a lack of racial and ethnic diversity in the patient qualitative sample [27]. Future research should aim to assess the appropriateness and feasibility of the implementation strategies with ethnically diverse patient groups. Secondly, the implementation strategies developed from this study must be specified and operationalized to enable implementation for each setting. Proctor’s guidance [44] can be used to enable this for future implementation work around PROMs for different gender-affirming care settings.

Conclusion

This study presents evidence-based, feasible, and acceptable strategies for integrating the use of PROMs in gender-affirming care. The developed strategies can be used by clinicians, policy-makers, and researchers to lead PROM implementation efforts for gender-affirming care with potential generalisability to other clinical areas. The strategies can be used to enhance patient-centeredness of gender-affirming care, as emphasised from international standard of care, and ensure PROM benefits are realised while minimising research waste associated with lack of PROM uptake.

Supporting information

(DOCX)

(XLSX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the manuscript and its Supporting Information files.

Funding Statement

Rakhshan Kamran is funded by an NIHR Doctoral Research Fellowship (NIHR301792). The funding source had no involvement in the study.

References

- 1.Coleman E, Radix AE, Bouman WP, et al. Standards of Care for the Health of Transgender and Gender Diverse People, Version 8. International Journal of Transgender Health. 2022;23(sup1):S1–S259. doi: 10.1080/26895269.2022.2100644 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Agochukwu-Mmonu N, Radix A, Zhao L, et al. Patient reported outcomes in genital gender-affirming surgery: the time is now. Journal of Patient-Reported Outcomes. 2022;6(1):39. doi: 10.1186/s41687-022-00446-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Black N. Patient reported outcome measures could help transform healthcare. BMJ. 2013;346:f167. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(9):606–613. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Murray DW, Fitzpatrick R, Rogers K, et al. The use of the Oxford hip and knee scores. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2007;89(8):1010–1014. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.89B8.19424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.The World Health Organization Quality of Life assessment (WHOQOL): position paper from the World Health Organization. Soc Sci Med. 1995;41(10):1403–1409. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(95)00112-k [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Greenhalgh J, Gooding K, Gibbons E, et al. How do patient reported outcome measures (PROMs) support clinician-patient communication and patient care? A realist synthesis. Journal of Patient-Reported Outcomes. 2018;2(1):42. doi: 10.1186/s41687-018-0061-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Graupner C, Kimman ML, Mul S, et al. Patient outcomes, patient experiences and process indicators associated with the routine use of patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) in cancer care: a systematic review. Support Care Cancer. 2021;29(2):573–593. doi: 10.1007/s00520-020-05695-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Makhni EC, Swantek AJ, Ziedas AC, et al. The Benefits of Capturing PROMs in the EMR. NEJM Catalyst. 2021;2(8). doi: 10.1056/CAT.21.0134 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Field J, Holmes MM, Newell D. PROMs data: can it be used to make decisions for individual patients? A narrative review. Patient Related Outcome Measures. 2019;10:233–241. doi: 10.2147/PROM.S156291 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Basch E, Deal AM, Dueck AC, et al. Overall Survival Results of a Trial Assessing Patient-Reported Outcomes for Symptom Monitoring During Routine Cancer Treatment. JAMA. 2017;318(2):197–198. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.7156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kamran R, Jackman L, Chan C, et al. Implementation of Patient-Reported Outcome Measures for Gender-Affirming Care Worldwide: A Systematic Review. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6(4):e236425. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.6425 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jones BA, Bouman WP, Haycraft E, Arcelus J. The Gender Congruence and Life Satisfaction Scale (GCLS): Development and validation of a scale to measure outcomes from transgender health services. Int J Transgend. 2018;20(1):63–80. Published 2018 Apr 26. doi: 10.1080/15532739.2018.1453425 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cohen-Kettenis PT, van Goozen SH. Sex reassignment of adolescent transsexuals: a follow-up study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1997;36(2):263–271. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199702000-00017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ziegenfuss JY, Grossman ES, Solberg LI, et al. Is the Promise of PROMs Being Realized? Implementation Experience in a Large Orthopedic Practice. American Journal of Medical Quality. 2022;37(6):489. doi: 10.1097/JMQ.0000000000000079 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bele S, Rabi S, Zhang M, et al. Uptake of pediatric patient-reported outcome and experience measures and challenges associated with their implementation in Alberta: a mixed-methods study. BMC Pediatr. 2023;23(1):369. Published 2023 Jul 18. doi: 10.1186/s12887-023-04169-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Horta-Baas G. Patient-Reported Outcomes in Rheumatoid Arthritis: A Key Consideration for Evaluating Biosimilar Uptake?. Patient Relat Outcome Meas. 2022;13:79–95. Published 2022 Mar 30. doi: 10.2147/PROM.S256715 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Spencer KL, Absolom KL, Allsop MJ, et al. Fixing the Leaky Pipe: How to Improve the Uptake of Patient-Reported Outcomes-Based Prognostic and Predictive Models in Cancer Clinical Practice. JCO Clin Cancer Inform. 2023;7:e2300070. doi: 10.1200/CCI.23.00070 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Foster A, Croot L, Brazier J, Harris J, O’Cathain A. The facilitators and barriers to implementing patient reported outcome measures in organisations delivering health related services: a systematic review of reviews. J Patient Rep Outcomes. 2018. Dec;2:46. doi: 10.1186/s41687-018-0072-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Van Egdom LSE, Oemrawsingh A, Verweij LM, Lingsma HF, Koppert LB, Verhoef C, et al. Implementing Patient-Reported Outcome Measures in Clinical Breast Cancer Care: A Systematic Review. Value in Health. 2019. Oct 1;22(10):1197–226. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2019.04.1927 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gelkopf M, Mazor Y, Roe D. A systematic review of patient-reported outcome measurement (PROM) and provider assessment in mental health: goals, implementation, setting, measurement characteristics and barriers. Int J Qual Health Care. 2020. Mar 11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.England NHS. Treatment and support of transgender and non-binary people across the health and care sector: Symposium report. 2015. https://www.england.nhs.uk/commissioning/wp-content/uploads/sites/12/2015/09/symposium-report.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 23.Royal College of General Practitioners. The role of the GP in caring for gender-questioning and transgender patients: RCGP Position Statement. 2019. https://allcatsrgrey.org.uk/wp/download/management/human_resources/diversity/RCGP-transgender-care-position-statement-june-2019.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 24.Royal College of Psychiatrists. Supporting transgender and gender-diverse people: Position Statement. 2018. https://www.rcpsych.ac.uk/pdf/PS02_18.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bauer MS, Kirchner J. Implementation science: What is it and why should I care? Psychiatry Research. 2020;283:112376. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2019.04.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Damschroder LJ, Reardon CM, Widerquist MAO, Lowery J. The updated Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research based on user feedback. Implementation Science. 2022;17(1):75. doi: 10.1186/s13012-022-01245-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kamran R, Jackman L, Laws A, et al., Patient and Healthcare Professional Perspectives on Implementing Patient-Reported Outcome Measures in Gender-Affirming Care: A Qualitative Study. 2023. b;12(4). doi: 10.1136/bmjoq-2023-002507 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Waltz TJ, Powell BJ, Fernández ME, Abadie B, Damschroder LJ. Choosing implementation strategies to address contextual barriers: diversity in recommendations and future directions. Implement Sci. 2019;14(1):42. doi: 10.1186/s13012-019-0892-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Powell BJ, Waltz TJ, Chinman MJ, et al. A refined compilation of implementation strategies: results from the Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change (ERIC) project. Implement Sci. 2015;10:21. doi: 10.1186/s13012-015-0209-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Howell D, Powis M, Kirkby R, et al. Improving the quality of self-management support in ambulatory cancer care: a mixed-method study of organisational and clinician readiness, barriers and enablers for tailoring of implementation strategies to multisites. BMJ Qual Saf. 2022;31(1):12–22. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2020-012051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Weir A, Presseau J, Kitto S, Colman I, Hatcher S. Strategies for facilitating the delivery of cluster randomized trials in hospitals: A study informed by the CFIR-ERIC matching tool. Clin Trials. 2021;18(4):398–407. doi: 10.1177/17407745211001504 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pinnock H, Barwick M, Carpenter CR, et al. Standards for Reporting Implementation Studies (StaRI) Statement. BMJ. 2017;356:i6795. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i6795 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ahmed S, Zidarov D, Eilayyan O, Visca R. Prospective application of implementation science theories and frameworks to inform use of PROMs in routine clinical care within an integrated pain network. Qual Life Res. 2021;30(11):3035–3047. doi: 10.1007/s11136-020-02600-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Roberts NA, Janda M, Stover AM, et al. The utility of the implementation science framework “Integrated Promoting Action on Research Implementation in Health Services” (i-PARIHS) and the facilitator role for introducing patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) in a medical oncology outpatient department. Qual Life Res. 2021;30(11):3063–3071. doi: 10.1007/s11136-020-02669-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.van Oers HA, Teela L, Schepers SA, Grootenhuis MA, Haverman L, ISOQOL PROMs and PREMs in Clinical Practice Implementation Science Group. A retrospective assessment of the KLIK PROM portal implementation using the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR). Qual Life Res. 2021;30(11):3049–3061. doi: 10.1007/s11136-020-02586-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Manalili K, Santana MJ, ISOQOL PROMs/PREMs in clinical practice implementation science work group. Using implementation science to inform the integration of electronic patient-reported experience measures (ePREMs) into healthcare quality improvement: description of a theory-based application in primary care. Qual Life Res. 2021;30(11):3073–3084. doi: 10.1007/s11136-020-02588-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stover AM, Haverman L, van Oers HA, et al. Using an implementation science approach to implement and evaluate patient-reported outcome measures (PROM) initiatives in routine care settings. Qual Life Res. 2021;30(11):3015–3033. doi: 10.1007/s11136-020-02564-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Proctor E, Silmere H, Raghavan R, et al. Outcomes for Implementation Research: Conceptual Distinctions, Measurement Challenges, and Research Agenda. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2011;38(2):65–76. doi: 10.1007/s10488-010-0319-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stover AM, Urick BY, Deal AM, et al. Performance Measures Based on How Adults With Cancer Feel and Function: Stakeholder Recommendations and Feasibility Testing in Six Cancer Centers. JCO Oncol Pract. 2020;16(3):e234–e250. doi: 10.1200/JOP.19.00784 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nilsen P. Making sense of implementation theories, models and frameworks. Implement Sci. 2015;10:53. doi: 10.1186/s13012-015-0242-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.May C, Finch T. Implementing, Embedding, and Integrating Practices: An Outline of Normalization Process Theory. Sociology. 2009;43(3):535–554. doi: 10.1177/0038038509103208 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Field B, Booth A, Ilott I, Gerrish K. Using the Knowledge to Action Framework in practice: a citation analysis and systematic review. Implement Sci. 2014;9:172. doi: 10.1186/s13012-014-0172-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Snyder CF, Aaronson NK, Choucair AK, et al. Implementing patient-reported outcomes assessment in clinical practice: a review of the options and considerations. Qual Life Res. 2012;21(8):1305–1314. doi: 10.1007/s11136-011-0054-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Proctor EK, Powell BJ, McMillen JC. Implementation strategies: recommendations for specifying and reporting. Implement Sci. 2013;8:139. Published 2013 Dec 1. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-8-139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX)

(XLSX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are within the manuscript and its Supporting Information files.